94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Built Environ., 04 May 2023

Sec. Sustainable Design and Construction

Volume 9 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2023.1161856

Introduction: Urban studies have examined the potential of urban interventions to upgrade spaces. This is the focus of relational approaches that emphasize interactions between interventions and users. One approach, actor–network theory, views these interactions as temporary stabilized relational effects. Despite its usefulness in uncovering diverse interactions in urban spaces, the utilization of actor–network theory in unpacking these relations has been limited.

Methods: This study utilized an actor–network theory-inspired ethnography in a temporary urban intervention in Abdali Boulevard, in Jordan, to bridge this gap. It relied on desk research, interviews, and site observations to explore the different intervention–user interactions.

Results: The findings revealed various interactions and relational patterns occurring between interventions and their users through their presence and absence in space and time, where users attended to, engaged with, overlooked, bypassed, disturbed the intervention, or floated between different modes of interaction.

Discussion: Unpacking these diverse interactions and relations provides a nuanced perspective on the effects of urban interventions on spaces. This would be useful for designers in developing new ways of designing through offering interventions that engage the public.

Conventional approaches in urban design tend to impose control over public spaces to manage their use (Carmona, 2010; 2014; Madanipour, 2010). Conversely, more flexible approaches allow freedom of choice to accommodate different uses (Whyte, 2001; Gehl, 2013; Mehta, 2014). This flexibility extends to the co-production of spaces and users and their interaction (Lefebvre, 2012). Based on the latter approaches, recent studies have explored the potential of urban interventions to transform spaces into spontaneous, open arenas with new use possibilities and different ways of engaging users (Cohen et al., 2014; Hunter et al., 2015). Some studies have focused on interventions that are temporary in nature (Lehtovuori, 2011; Almousa, 2015; Wagner, 2016; Madanipour, 2017; Rossini, 2019; Paukaeva et al., 2021; Skytt-Larsen et al., 2022), modify spaces continuously, and allow different emerging uses.

These aspects have caught the attention of relational researchers (Pinder, 2008; Tornaghi, 2015; Manfredini et al., 2017; Wohl, 2017), with some adopting actor–network theory (ANT) (Law, 2009; Latour, 2012; 2018; Law et al., 2012; Kim, 2017; Sharif, 2020a; 2020b; Yaneva, 2022). These relational approaches, including ANT, view space as a collaborative achievement between existing urban elements, new elements, and users (Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019). A consideration of the temporality of new elements facilitates an improved understanding of unfinished, ambiguous, and continuously upgraded spaces in relation to produced uses and engagements. However, although these studies explore urban interventions and their potential to produce spaces that are continuously altered to generate new uses, they rarely address the variety and continuity of the interactions between interventions and their users.

This research utilizes actor–network theory (ANT) and deploys its potential to view the socio-technical world through networks and produced relational effects to investigate the reality of interactions between space interventions and their users. ANT allows for a specific focus on the variety and continuity of interactions by understanding these relations and unpacking their diverse and dynamic nature, which has rarely been utilized in previous ANT-related research. The research applies ANT to provide a nuanced perspective on the potential emergent interactions between introduced urban interventions and their users. It explores how these short-lived alterations in public spaces induce different uses. In particular, this study examines how temporary arrangements, introduced by designers, result in different and continuous relational patterns (rearrangements of relations that are built/strengthened, cut/weakened, or fluctuate between interventions and users). Through considering their temporality, the research aims at accounting for the spatiotemporal interactions occurring between interventions and their users through their presence and absence in space and time (i.e., before the interventions were installed, during their existence, and after their removal), which stimulate diverse and continuous arrangements and changes in relations. In this study, ANT is used to empirically investigate a temporary intervention in Abdali Boulevard in Amman, Jordan, to understand the different interactions revealed in terms of stabilized relational patterns. This investigation is likely to be useful for designers in developing new ways of designing spaces through offering interventions that engage the public and understanding the nature of such engagement when (i) taking into account the multiple, complex, and even unpredictable intervention-user interactions and (ii) considering the different capabilities of co-functioning of spaces when new interventions are introduced and new uses are induced.

Relational approaches in urban studies view the socio-technical world based on the dynamic relations between space and its use (Tornaghi, 2015; Tornaghi & Knierbein, 2015; Wohl, 2017). Accordingly, spaces are viewed not as final products with pre-arranged configurations but as processes of arrangement between spatial elements and users (Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019). These approaches explore new ways to challenge and transform spaces into dynamic, unpredictable arenas that offer diverse possibilities of use and engagement. In particular, relational approaches are interested in disruptive encounters in the form of interventions to upgrade, modify, and activate spaces to create different uses (Altrock & Huning, 2015). These interventions disrupt the order of the urban space, infuse new qualities that enrich user experience, and produce a creative space that becomes livable rather than lived (Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019). Consequently, such interventions become points of creativity, change, and resistance, producing different spaces and expanding the emerging experiences of their users.

Some studies have paid particular attention to temporary interventions (Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019), where time is a dynamic and crucial variable that provides a temporal frame for the produced interactions (Purpura, 2016; Madanipour, 2017). Through these interventions that interrupt the space for a short period of time, the space transcends the expression of fixed, predictable content to reveal transformative, unforeseen elements that can respond to different issues and upcoming events (Purpura, 2016), stimulating different uses and activating new, previously unlived experiences. In this way, temporary interventions signify a type of spatiotemporal production and present an essential component of urban development processes (Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019). Although such interventions are ephemeral, the emergent interactions leave a lasting effect that connects space with its users in different and unexpected ways.

Studies on temporary interventions address the aspect of ephemerality through introducing temporary events or changing the space to host short-term use (Wohl, 2017). However, the present study addresses these aspects by focusing on the establishment of flexible (changeable or removable) structures that introduce different events and produce changes in use. Previous similar studies have explored adaptable temporary structures that are assembled and disassembled (Tardiveau & Mallo, 2014; Hotakainen & Oikarinen, 2019) or continuously transformed (Almousa, 2015), potentially upgrading spaces and generating different responses from their users.

Among these studies, and based on similar relational approaches, ANT provides a way to understand the socio-technical world through networks that produce relational effects between humans and non-humans (Latour, 2012; 2018; Akrich, 2023). ANT particularly involves exploring new ways of transforming spaces into dynamic and uncertain entities to extend their possibilities of use and engagement. Urban studies utilizing ANT (Kim, 2017; Sharif, 2020a) use concepts such as inscription/prescription (Akrich, 2023) to refer to the initial creation of spatial relations by designers, and translation (Law, 2009; Latour, 2012) to show how these relations are variously and constantly amended by users. Time and space are folded into and affect these relations (Latour, 2012). Consequently, interactions in urban spaces are distributed through entanglements and rearrangements of relations that are built/strengthened, cut/weakened, or fluctuate (Yaneva, 2022) between human and non-human entities through similar or different time–space frames (Murdoch, 1998)). Through these interactions, relations oscillate between different forms of presence and absence of actors in time and/or space. In some cases, actors might be physically present in time and space or present in one dimension and absent in the other, while still producing specific relational effects (Murdoch, 1998; Latour, 1999). ANT differs from other relational approaches in that it does not consider any reality outside the relational effect (Harman, 2009), which makes it valuable for empirical investigations, as it specifically follows the relations and emerging translations wherever they may lead (Yaneva, 2022). However, as these relations continuously change to create alternative arrangements, they result in variable and continuous translations (Law, 2009; Latour, 2012; Law et al., 2012). Accordingly, translations can only be traced through their stabilized moments, when they appear through enduring and recurring forms or repeated relations with continual/regular production of interactions (Law, 2009; Law et al., 2012).

Although relational approaches have been used to explore these urban interventions, the adoption of ANT to study them is rare (Boonstra & Specht, 2012; Harboe, 2012; Costa, 2018), despite its potential in urban studies to investigate the interactions between space and users by following relations and continuous translations (Murdoch, 2006; Kim, 2017; Sharif, 2020a; 2020b). Among the few researchers utilizing ANT for these explorations, Boonstra and Specht (2012) utilized the example of Heemraadpark in Singeldingen, the Netherlands, in 2008, where a poorly developed and almost abandoned park was turned into a dynamic attraction through deploying a temporary kiosk made out of a spring-roll cart. This stimulated a string of activities in the park lasting 6 weeks. Costa (2018) described a temporary community garden structure at an abandoned space in Maria de Feira, Portugal. This flexible structure, comprising ceramic pots and wooden piles, assisted in place activation and public engagement by encouraging planting and maintenance activities and associated events. Harboe (2012) explored a temporary structure installed for 2 weeks in a deserted area of northeast London. Made of freely constructed steel bars and scaffolded roofing, this structure comprised easily modified activity spaces and components that enlivened an otherwise abandoned space. Harboe (2012) also explored an intervention constructed at a dumping site at the edge of Parc de la Villette in Paris. This flexible, scaffolded structure could be unfolded, extended, or altered in response to daily changes, to promote residents’ interaction during events hosted for 5 weeks. In each of these cases, the introduced interventions, while present, helped users produce different networks in space through building relations with the intervention, the surrounding space, and other users. The interventions also had long-lasting effects, even after their removal (Boonstra & Specht, 2012). These examples provide valuable insights into how urban interventions may upgrade the possibilities of space and generate user responses vital for encouraging interactions. However, few empirical investigations of the reality of these interactions, especially in terms of their variability and continuity, exist.

The research aims at applying ANT to unpack the potential emergent interactions between introduced urban interventions and their users by accounting for the different and continuous relational patterns occurring between interventions and their users through their presence and absence in space and time. Specifically, an ANT-inspired ethnography was used to empirically investigate a temporary intervention in Abdali Boulevard in Amman, Jordan, to understand the different interactions and relations traceable through stabilized moments of endurance and occurrence. This investigation examined the possibilities of co-functioning that depend on both the scrutinized elements in space and the responding users as well as the diverse possibilities of associations between spaces and users.

The case study used in this research comprised a temporary intervention developed in the Abdali project, a mega-urban generation project and mixed-use development located at the center of Amman developed as its new downtown, between 2015 and 2020 (Abdali website, 1 January 2021). Within the project, Abdali Boulevard is an east–west pedestrian spine considered the main public space in the project’s first phase (Figure 1). It follows the site’s contours, combining terraces allocated at three levels. It also reflects a certain design quality through its outdoor spaces, landscape features, and furnishings surrounded by buildings that include ground-floor restaurants and retail spaces and upper-floor residential and office spaces (Zalloom, 2015).

FIGURE 1. The map of the Abdali project with a map and photo of Abdali Boulevard. (Source: http://www.ammancitygis.gov.jo/).

According to direct communication with the Abdali project management, temporary interventions have been introduced in various forms and changeable modes to enhance the quality of the urban space, suit different events and situations (four monthly signature events and 30 daily or weekly events annually), and expand user experiences. One commonly used temporary intervention has been an arch-like structure decorated with hanging flowers, typically used in spring, which was installed and uninstalled in various forms and several times between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 2). As the intervention introduces a different type of spectacle to the boulevard, it encourages users to experience it while passing by or standing beside it, observing and taking photos. The significance of this case is that it represents a highly repetitive intervention that allows direct and intimate interactions, unlike other, less approachable interventions (such as those that are distant or fenced off). Studying the former type opens specific possibilities, although studying the latter type in future research would allow for different horizons to be investigated.

FIGURE 2. A generic view of Abdali Boulevard (left) and a view of the boulevard with the intervention (right). (Source: Abdali, Uptown Urban Development, PowerPoint Presentation (webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com).

This study utilized an ANT-inspired ethnography, which differs from traditional ethnography, as it allows for in-depth investigation through developing sensitivity and receptivity toward the emergence and change of socio-technical relations between actors involved in complex and dynamic processes and folded into similar or different time–space frames (Murdoch, 1998; Latour, 2012; Kärrholm, 2016; Sharif, 2016; 2019; Yaneva, 2022). This allows the researcher to actively scrutinize and refine understandings of and from the research process to enable effective and pertinent reflexive translations of the research project (Sheehan, 2011).

Data were collected through a number of methods to allow effective engagement with the intervention and its users and the different interaction modes between them. The fieldwork was preceded by a desk-based study of documents and websites for sourcing relevant data on the Abdali project and its boulevard design and use from 2015 to 2020. This was followed by semi-structured interviews with five management members (30 min each), conducted between January 2019 and March 2019. The interview schedule was flexible, targeting the main design intentions in terms of involving users and simulating their interactions. Furthermore, the research involved semi-structured interviews with 35 boulevard users (10–15 min each). The users were directly approached during site visits. They included 21 visitors and 14 employees, which distributed the sample into less and more frequent users. The sample also comprised 19 females and 16 males, with ages ranging between 15 and 75 years. They were asked about their experience and engagement with the structure, regardless of whether it was in situ. The interviews were aimed at exploring and understanding how interventions, introduced by designers intended to engage users, and how the actual engagement of the users presented different and continuous interactions and relational patterns occurring between interventions and their users through their presence and absence in space and time, which might not be initially anticipated by the designers. The research also involved fifteen participant observations of the temporary intervention (2–3 h each, two times a week, on different days each week to ensure a representative distribution between and within weekdays and weekends) conducted between March 2019 and October 2020 to capture the reality of interactions between the structure and users during its existence and before/after its installation/removal. While the observations allowed the author to observe and follow the actions and interactions of users, the interviews helped in understanding these interactions and how users explained and justified them. Both interviews with users and observations were carried out on weekdays and weekends in the afternoon when people were often anticipated to be outside (after finishing work, school, or chores on weekdays, on their free time on weekends, and when the weather was pleasant for being outside).

The management members were identified and accessed through colleagues in companies in the area and they were recruited by email. The users were recruited during the site visits, which was mainly affected by users’ availability in the site. The number of interviews and site observations was defined based on reaching saturation–the state when the emerging data confirms, or mostly repeats, the previously collected data while accounting for the many possible variations (Glaser & Strauss, 2010). The researcher provided a statement of the study purpose, duration, and procedures to all participants and obtained informed consent from them. Furthermore, the researcher maintained participants’ confidentiality and ensured their anonymity through employing pseudonyms for users and with general referral to management in relation to data from managers, in addition to the use of blurred photographs.

The interviews were documented through either notes or tape recordings and observations were recorded through notes, sketches, and photography. The collected data were analyzed thematically using the qualitative data analysis software Nvivo 10. Data analysis was aimed at (i) identifying codes that relate to the different interactions and emerging relations between the intervention and its users, (ii) grouping the emerging codes to identify potential themes concerning the types of emerging intervention-user relations during the presence and absence of the intervention, (iii) defining and finalizing themes, and (iv) presenting the results in a coherent and logical sequence. The interviews and site observations presented various, continuous, and sometimes unpredictable interactions and relational patterns occurring between interventions and their users through their presence and absence in space and time, where users attended to, engaged with, overlooked, bypassed, disturbed the intervention, or floated between different modes of interaction.

The process initially included exploring different interactions featured through stabilized relational patterns (rearrangements of relations that are built/strengthened, cut/weakened, or fluctuate between interventions and users), while the intervention was either present or absent (i.e., before the intervention was installed, during its existence, and after its removal). This included the following three analytical forms:

a) The co-presence of actors and their mutual existence in time and space;

b) Actors that could be physically present in space but absent in time, when the structure was there, but not necessarily the people; and

c) Actors that could be physically absent in space but present in time, which was mainly either before the structure’s installation or after its removal.

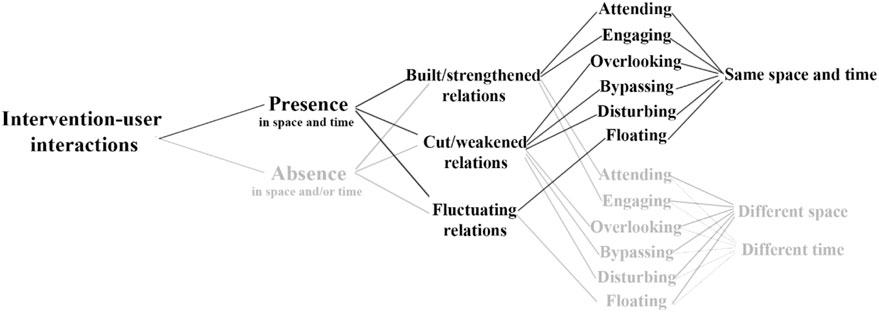

The first part of this section presents the different intervention–user interactions while the intervention was present, and the effects resulting from their association, wherein the structure was foregrounded and backgrounded and users presented different responses to these changes (attending to, engaging, overlooking, bypassing, disturbing, and floating). Three types of relational patterns were identified as stabilized (Law, 2009; Law et al., 2012): built/strengthened relations occurred when users attended to or engaged with the intervention; cut/weakened relations occurred when users overlooked, bypassed, or disturbed the intervention; and fluctuating relations occurred when users floated between building and cutting as well as strengthening and weakening within the same or different interaction modes. A relational understanding of the interactions between the intervention and users showed them to be varied and continuous (see also Latour, 2012; Yaneva, 2022).

These relations were stabilized in two cases: attending to occurred when users built or strengthened relations with the intervention and sometimes with other users, whereas engaging occurred when users built or strengthened relations with the intervention and helped or drove other users to engage with it. The boulevard management mentioned that the flowered arch’s potential included its multiple functional abilities for its users. Its colorful, detailed design attracted people’s attention to view, touch, and engage with it in different ways.

The observations showed that users might attend to the intervention because it captured their interest. The intervention was keenly noticed and foregrounded [as a relational effect; see Latour (1986); Yaneva (2022)] due to its colors, details, and nearby users within its surrounding physical space that were less noticed and sometimes slipped into the background. This happened with users who sat, stood, or walked through or around the intervention while stopping occasionally to observe the structure, most of its elements, or sometimes the interactions happening inside and around it. This confirmed that attending-to users foregrounded the structure because they could closely observe and perhaps touch certain details while standing inside or next to it. Attending-to users also included people who viewed it from surrounding areas or who observed it from building windows and upper levels and those walking or engaging in other activities at a distance but who approached the structure because of its appeal. These scenarios imply that attending-to users could still foreground the structure because of its noticeable colors and details, even from a distance. The aesthetic appeal of the intervention and the enjoyable events occurring within and around it (as it sometimes blended with the background and surroundings) made users acknowledge the structure and build relations with it, and sometimes with other users. Accordingly, they scanned the environment more carefully and slowed down to experience the structure’s overhanging or extended components.

The observations also demonstrated that users might engage with the structure because it stimulated their interest to take part in it. The intervention, physical space, and even nearby users became highly noticeable and foregrounded and rarely fell into the background. This type of experience occurred among users who sat, stood, wandered, and stopped within or around the intervention to become part of the interaction, which sometimes stimulated further interactions. People engaged other people and objects by talking about the structure, demonstrating noticeable actions, sketching, and taking photos (Figure 3). Husam, a new visitor of the boulevard, noted that people were engaged through discussions and activities and being asked by others to take their photos. Maya, another new visitor, mentioned that people called their companions and sometimes brought flowers, souvenir notebooks, and artwork to take photos of themselves or particular parts of the intervention. These actions attracted people from inside, around, or further beyond the structure. Through this deep interest in the environment, users not only acknowledged the structure and built relations with it but also helped engage and relate other people and things to it in the process. As Michael (2006, p. 116) suggested: “space, here, emerges from such mutual performativities (or warpings) enacted by persons-and-their artefacts interacting with persons-and-their-artefacts.”

FIGURE 3. Instances of building/strengthening relations with the intervention demonstrated through engaging users: two girls discussing a photo they took for the structure (left), a girl taking a photo of the structure with a sketch of it in her hand (right). (Source: Author).

These relations were stabilized in three cases: overlooking and bypassing, wherein users cut relations with the structure and other users while trying to maintain relations with the space, and disturbing, wherein users contributed to cutting relations between the structure and other users.

The observations also demonstrated that users overlooked the intervention because it was a relatively regular alteration to which they had become accustomed. The intervention and nearby users blended into the background of the space, causing the immediate environment to become annulled and unnoticed, with its details blurred or even hidden. This happened specifically with workers and regular visitors already familiar with the boulevard. Diana, a frequent boulevard visitor, commented that this alteration was no different from other interventions. Hameed, another regular visitor, expressed the view that other alterations were more intriguing to experience. These users witnessed similar alterations in this space in a way that their presence was of no consequence. Unless a different kind of intervention caught their eye, they would only notice the entirety of the space. Other users tended to only survey or navigate the space to reach their destinations (Figure 4, left). Halima, another regular visitor, was no longer aware of the structure’s presence and Khaled barely noticed it was there. These users rarely paid attention to any alteration in the space because it did not capture their interest. Increased familiarity with an environment and the need to focus on a specific task allowed little room for users to acknowledge these interventions or build any relations with them at any level. They were instead involved in a “scanning modality or selective form of attention” (Degen et al., 2010, p. 68).

FIGURE 4. Instances of cutting/weakening relations with the intervention demonstrated through overlooking: a man navigating the space to reach his destination (left) and disrupting: playing around the structure (right). (Source: Author).

The observations showed that users could bypass the intervention and the place surrounding it because they considered it a disturbance interrupting the place where it was installed. The intervention and other users here were deliberately backgrounded by users to foreground the space through which they moved and in which they conducted activities. For example, Khaled walked away from the structure after spotting it from a distance and noticing the crowds surrounding it. Muna preferred to walk on a higher level of the boulevard to avoid being disturbed by the structure, as it stood in her way. Huda commented that she did not favor periods with many structures in the boulevard because it became busy. The need to navigate the environment without interruptions caused people to be annoyed by the intervention and resulted in their cutting relations with it and with its users.

Some users had a disturbing influence on the intervention, as they saw it as a place to play and engage in disorderly activities within and around it. The intervention was foregrounded, and potentially the space around it as well, but other users around the space were backgrounded. This happened with children who moved around randomly as they saw the intervention as more of a playground or a track to run through, without considering passers-by (Figure 4, right). Sameeha complained that when unsupervised children played around the intervention, it became unruly and people stayed away. Even when supervised, children might force their companions to move away with them. Adults created similar disorderly gatherings or blocked the way while conversing, walking, and taking photos, which could distract and annoy others and prevent their engagement with the structure. Sometimes, the disturbing users were children who saw the intervention as a stand, off which to pick flowers. These playful and disruptive activities occurring within the environment made disturbing users acknowledge the intervention and engage with it while being scarcely aware of anyone within or around it, which led them to contribute to cutting relations between the structure and other users. Boulevard management mentioned that the interventions faced many disruptions. However, they aimed to change this culture over time through the continuous introduction of new interventions; hence, it was expected that people would gain greater awareness and reduce their disruptive behavior.

These relations were stabilized when users floated between building and cutting as well as strengthening and weakening relations within the same or different modes of intervention–user interaction. Latour (2006, p. 68) stated:

‘Different regimes of action are relayed to one another, leading me from one competence to the next. I am neither in control nor without control: I am formatted. I am afforded possibilities for my existence, based on teeming devices scattered throughout the city. I go from one offer to the next.’

Different forms of embodied experience fluctuated with multiple intensities of interactions and strengths and weaknesses of relations with the material environment. Some users fluctuated between engagement and disengagement with the intervention because, for them, maintaining focus on a specific aspect inside, besides, or beyond it was difficult. The intervention became noticed and foregrounded in some situations or went unnoticed and slipped into the background in others. People could be initially interested in the intervention but might be drawn to another structure, parts of the surroundings, or other users who attracted or distracted attention. Users were driven by following or avoiding each other within the space while sometimes losing the sense of its function. Although a general conversation could distract attention, it might be brought back through noticing or encountering an element of interest (Figure 5). As the conversation was interrupted and then continued, so was the awareness of the different elements of the intervention. Parents or guardians following or walking with children could fall into a similar pattern of interruption and fluctuate continuously between the children and the intervention. In other cases, people might be moving around, passing by, or heading to a destination, and become attracted by a specific element of the intervention before resuming their original movement.

FIGURE 5. Instances of fluctuating relations with the intervention demonstrated through fluctuating users: a man and woman talking in one instance with distracted attention from the intervention (left) then their attention is brought back to it, starting to aking photos (right). (Source: Author).

These scenarios show how different interruptions caused momentary changes in crystallized interactions, disintegrating them to be reformed again. Thus, users might keep oscillating between strong and weak relations. In other cases, these disruptions might cause discontinuities such that users became trapped in a new setting that diverted them from their initial setting. Such users might move from one relation type to another without returning to the original mode; that is, they slip between different practices and their associated perceptual fields often occur within short or long timespans. In both cases, instances of concentration and distraction and of looking and not looking could be accompanied by interest in or frustration with the new overtaking event, with actions becoming confused between walking, following, avoiding, and conversing, on the one hand, and involvement with the structure, on the other. These users acknowledged the intervention but only engaged with it when it made them occasionally focus or look once a particular element attracted their attention, only to be distracted again by other users, friends, or companions.

These three stabilized moments of interaction between the structure and its users showed that the intervention, in drawing passing users to interact with it, was likely to succeed in involving attending to and engaging users, although cases of overlooking, bypassing, and disrupting, while rare, still occurred. This is probably why the structure was created as a passage that could include users and allow them to pass rather than being fenced in and excluding others. That said, interventions made to blend in with the surroundings were more likely to interest users. Therefore, the intervention was made visually noticeable to stand out and non-obstructing to harmonize with its surroundings. The relational effects illustrated that there is no absolute success of an intervention in a space, but there can be degrees of success achieved through building more relations between the actors (see also Akrich, et al., 2002; Yaneva, 2022), and the converse holds true for varying degrees of failure. Table 1 shows a summary of different types of intervention-users interactions illustrated through the types of relations during the presence of actors and their mutual existence in time and space.

The second part of this section unpacks the different intervention–user interactions when one of them was absent and explores various possibilities of their association. While this part analyzes the same stabilized relational patterns (built/strengthened, cut/weakened, and fluctuating), the argument is that the relational understanding of the interactions between the intervention and users extends their variety and continuity (see also Latour, 2012; Yaneva, 2017).

Built/strengthened or cut/weakened relations between the intervention and users might still be stabilized even when they are distant in space (Murdoch, 1998), as technical artifacts allow humans to act at a distance and mingle absence with presence (Latour, 1999). This situation mainly occurs when the intervention is present but with people not necessarily there. For example, users might think or talk about the possible current intervention in the boulevard, hear about it from other people, or see it in other people’s photos, where they might engage or disengage with it. Users might also intentionally or unintentionally view websites or Facebook pages where the structure features in certain events, which might attract their thoughts. Here, the intervention could be foregrounded by people who might attend to a conversation or engage other people in a discussion about it (building/strengthening relations) or backgrounded by users who might overlook or bypass any thoughts or talks about it because they were not interested, or they did not like to take part in related events (cutting/weakening relations).

Built/strengthened or cut/weakened relations between the intervention and users might also be stabilized when they are distant in time (Murdoch, 1998), making the absent actors incorporeally present (Latour, 1999). This mainly occurs in situations before the structure is installed or following its removal. For example, considering the temporality of the intervention, people might anticipate a structure planned to be constructed for certain events by asking others and browsing websites or Facebook pages for interventions utilized in similar events. They might be encouraged to engage or disengage with it based on their own and other people’s experiences. Additionally, people might still think and talk about an intervention and share memories through experiences and photos even after its removal. They might criticize or praise the intervention compared with a newly installed structure or miss it when it is removed, as they develop certain attachments to the space itself, or might be relieved that they can reconnect with the space from which the intervention had detached them earlier. Alternatively, users might not see, interact with, or even learn about the structure before its installation, during its presence, or after its removal. Users might not visit, or avoid visiting, the boulevard for a certain period and therefore miss the opportunity to view or interact with the intervention exhibited during that time period. Users might decide to engage with the structure at a later point because of the current crowds but find it already taken down. Others might see it on the Internet and decide to visit on a particular day, by which time the intervention may have been removed. They might also see the intervention from past events and wish they were there. Different effects can be traced that arise when the structure is foregrounded by people who might attend to it by trying to think about or anticipate or engage with it by asking others about expectations concerning the future structure (building/strengthening relations). The intervention in other cases could be backgrounded by people who overlook it by not paying attention to other people’s anticipation or conversation about it. It could also be bypassed by people who do not want to learn about it so that they avoid going or taking their children there (cutting/weakening relations).

Fluctuating relations might also be stabilized when users float between different types of effects (in terms of the structure and users), between building and cutting as well as strengthening and weakening within the same or different modes of intervention–user interaction while being distant in time and/or space. Space–time, as it is folded in relations, reveals an ongoing process of change comprising uncertain, fragile, controversial, and ever-shifting ties and interactions (Latour, 2012). In this way, multiple spatial and temporal relations at play in any given space–time setting are likely.

These stabilization modes show that an intervention that can relate to users through encouraging them to think or talk about it, anticipate it, or remember it is likely to involve attending to and engaging users, although cases of overlooking, bypassing, and disrupting are still likely. Accordingly, the structure needs to be distinctive, different, and memorable within the space to encourage users to participate, look forward to future structures, and retain memories of previous ones. Table 2 shows a summary of different types of intervention-users interactions illustrated through the types of relations during the absence of actors in time or space.

Intervention–user interactions can stabilize different relations. Figure 6 provides a diagram that summarizes the results showing the different types of intervention-user interactions in cases of presence and absence in space and/or time, illustrated through different relations.

FIGURE 6. Summary of the results (different types of intervention-user interactions in cases of presence and absence in space and/or time, illustrated through different relations).

While related studies by Boonstra and Specht (2012), Costa (2018), and Harboe (2012) considered how relations are built in space due to introduced interventions, this study focused on different types of relations (Murdoch, 2006; Kim, 2017; Sharif, 2020a; 2020b), which were described in terms of building/cutting, strengthening/weakening, and fluctuating during the presence and absence of the intervention. It is challenging, although of critical importance, to understand more fully the nature of these relations, the types of actors they connect or disconnect, the degrees of strengths and weaknesses, and the timespan through which they stabilize.

Considering Abdali Boulevard’s intervention, building/strengthening relations between the intervention and users can happen through people who may attend to the structure because it catches their attention or others who may want to engage in the interactions happening around or inside it. Both interactions entail building or strengthening relations but differ in terms of the actors involved, the degree of such building/strengthening, and the time during which the stabilizations last. Attending to, for example, entails building or strengthening relations with the structure and possibly with users. Engaging involves more actors and entails stronger and more durable relations. The engaging user not only builds strong relations with the structure, space, and users but also helps other users build relations with the structure. Other cases of building/strengthening could connect people distant in time and space because people are interested in thinking about, talking about, or checking intervention-related sources while the intervention is there before its installation or after its removal.

Similarly, cutting/weakening relations, in the case of Abdali Boulevard’s intervention, can occur through interactions by users accustomed to these changes or those focused on specific tasks (overlooking), those who prefer to navigate an interruption-free environment (bypassing), or those who play or act in a disorderly manner (disrupting). However, it is challenging to identify the types of actors and the extent and duration of such cutting/weakening relations. Overlooking, for example, constitutes weakening relations with the structure because users steer their focus in a different direction, whereas bypassing is a more extreme case of weakening/cutting relations, wherein users are annoyed by interactions occurring around the structure. Disrupting is the most extreme, as users contribute to cutting other people’s relations with the intervention. Other cases of cutting/weakening could disconnect people while distant in time and/or space.

Finally, fluctuating relations can occur in the mentioned cases through shifts and oscillations in relations between the intervention and other structures, surroundings, events, and other users through the same or different times and spaces. The challenge in understanding the nature of relations is greater in this case because varying timespans are also concerned in which relations are formulated/reformulated and stabilized/destabilized, which range from a few minutes to much longer durations. Understanding the various types of relations as well as their nature entails diversifying and extending possible intervention–user interactions and expanding the involved networks in endless and hard-to-capture ways (see also Latour, 2012; Yaneva, 2022).

This study used ANT to provide a nuanced perspective on the potential emergent interactions and relational patterns between introduced urban interventions and their users during the intervention’s presence and absence. This was achieved by following the relations as they were built/strengthened, cut/weakened, or fluctuated with these interactions through the cases before the interventions were installed, during their existence, and after their removal. The study showed how the emerging relational patterns were indeed various and ongoing. The nature of these relations, the types of actors they connect or disconnect, the degrees of strengthening and weakening, and the timespan through which they stabilize all worked to further extend this diversity and continuity.

The findings illustrate how the interactions and changes in the relations between the intervention and users can contribute to changing, upgrading, and elevating spaces (Boonstra & Specht, 2012; Costa, 2018). Through these interactions, and as the installations are foregrounded, backgrounded, or slip in between, and as users engage with them in different ways, spaces are manipulated accordingly. Interactions that entail shifts and oscillations in intervention–user relations affect spaces. Furthermore, space is transformed with these interactions and changes in relations when the intervention is present. It transforms again when it is not yet installed or after its removal, as users approach the space differently. Spaces are involved in continuous and long-lasting effects despite, or because of, the temporality of the structures and their corresponding usage.

This understanding can be useful for designers in developing new ways of designing spaces through offering interventions that engage the public. Designers should consider the following:

a) Spaces comprising multiple, complex, and even unpredictable interactions should not be underestimated or pluralized, where each designer-initiated change in relations could present different translations. As relations change and fluctuate, they could transform such translations differently.

b) Spaces comprising these interactions are made up of fragile relations that tend to change and transform in nature to present continuous translations between temporary structures and users.

This understanding shows how spaces can be reproduced to counter stabilities and create change, emergence, and processuality. Spaces can also counter certainty by introducing ambiguity, spontaneity, and improvisation (Sennett, 2009). Spaces can cater to different capabilities of co-functioning and give rise to an infinite number of associations between current and new elements and users.

This study’s exploration of a temporary intervention in Abdali Boulevard contributes toward an enhanced understanding of micro-level interactions occurring within multiple space–time frames that make up spaces and allow for different and ongoing ways of engagement. This investigation followed the relations concerned and provided insights into their differing nature in a specific setting. However, one limitation of this study was that, given relations are various and fragile, it was difficult to fully identify and elaborate on them using only one practical example. Furthermore, these relations are specific to the example and could differ in other cases or even between different interventions within the same case. This limitation creates an opportunity because it shows the particularity of each presented case and prompts consideration of different cases in future research, which is likely to extend the discussion on interactions, relations, and their effects on spaces and ways of engaging their users.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

AS conducted the research fieldwork, the accumulation of observations, the drafting, and revision of the manuscript.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akrich, M. (2023). Actor network theory, bruno Latour, and the CSI. Soc. Stud. Sci. 53 (2), 169–173. doi:10.1177/03063127231158102

Akrich, M., Callon, M., Latour, B., and Monaghan, A. (2002). The key to success in innovation part I: The art of interessement. Int. J. Innov. Mngt. 6 (2), 187–206. doi:10.1142/s1363919602000550

Almousa, S. (2015). Temporary architecture: An architectural mirage tracing mind/body journey in installation art. PhD dissertation. Sheffield: University of Sheffield.

Altrock, U., and Huning, S. (2015). “Cultural interventions in urban public spaces and performative planning: Insights from shrinking cities in Eastern Germany,” in Public space and relational perspectives: New challenges for architecture and planning. Editors C. Tornaghi, and S. Knierbein 1st ed. (London: Routledge), 148–166.

Boonstra, B., and Specht, M. (2012). The appropriated city,” paper presented at the Spatial Planning in Transition Conference. The Hague, The Netherlands: Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment.

Carmona, M. (2010). Contemporary public space: Critique and classification, part one: Critique. J. Urb. Des. 15 (1), 123–148. doi:10.1080/13574800903435651

Carmona, M. (2014). The place-shaping continuum: A theory of urban design process. J. Urb. Des. 19 (1), 2–36. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.854695

Cohen, D., Marsh, T., Williamson, S., Han, B., Derose, K., Golinelli, D., et al. (2014). The potential for pocket parks to increase physical activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 28 (3), S19–S26. S19–S26. doi:10.4278/ajhp.130430-quan-213

Costa, A. (2018). Ways of engaging. Re-assessing effects of the relationship between landscape architecture and art in community involvement and design practice. PhD dissertation. Lisbon: Universidad de Lisboa.

Degen, M., Rose, G., and Basdas, B. (2010). Bodies and everyday practices in designed urban environments. Sc. Techn. Stud. 23 (2), 60–76. doi:10.23987/sts.55253

Glaser, B., and Strauss, A. (2010). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: AldineTransaction.

Harboe, L. (2012). Social concerns in contemporary architecture: Three European practices and their works. Oslo: Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Unpublished PhD dissertation.

Hotakainen, T., and Oikarinen, E. (2019). Balloons to talk about: Exploring conversational potential of an art intervention. plaNext – Next Gen. Plan. 9, 45–64. doi:10.24306/plnxt/59

Hunter, R., Christian, H., Veitch, J., Astell-Burt, T., Hipp, A., and Schipperijn, J. (2015). The impact of interventions to promote physical activity in urban green space: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 124, 246–256. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.051

Kärrholm, M. (2016). Retailising space: Architecture, retail and the territorialisation of public space. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

Kim, J. (2017). Multiple enactments of public space: An affordance analysis on stabilisation and multiplicity of user activity, PhD dissertation. London: University College London.

Latour, B. (2018). An inquiry into modes of existence: An anthropology of the moderns. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (1999). Factures/fractures: From the concept of network to the concept of attachment. RES Anthrop. Aesthet. 36, 20–31. doi:10.1086/resv36n1ms20167474

Latour, B. (2006). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. (1986). “The powers of association,” in Power, action and belief. A new sociology of knowledge? Sociological review monograph 32. Editor J. Law 1st ed. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul), 264–280.

Law, J. (2009). “Actor network theory and material semiotics,” in The new blackwell companion to social theory. Editor B. Turner (West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell), 141–158.

Law, J., Bijker, W., Hughes, T., and Pinch, T. (2012). “Technology and heterogeneous engineering: The case of Portuguese expansion,” in The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of Technology. Editors W. Bijker, T. Hughes, and T. Pinch (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 105–127.

Lefebvre, H. (2012). “From the production of space,” in Theatre and performance design. Editors J. Collins, and A. Nisbet (London: Routledge), 81–84.

Lehtovuori, P. (2011). Towards experiential urbanism. Crit. Soc. 38 (1), 71–87. doi:10.1177/0896920511407222

Madanipour, A. (2017). Cities in time: Temporary urbanism and the future of the city. London: Bloomsbury.

Madanipour, A. (2010). “Introduction,” in Whose public space? International case studies in urban design and development. 1st ed. (London: Routledge), 1–15.

Manfredini, M., Tian, X., Jenner, R., and Besgen, A. (2017). Transductive urbanism: A method for the analysis of the relational infrastructure of malled metropolitan centres in auckland, New Zealand. Athens J. Arch. 3 (4), 411–440. doi:10.30958/aja.3-4-5

Mehta, V. (2014). Evaluating public space. J. Urb. Des. 19 (1), 53–88. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.854698

Michael, M. (2006). Technoscience and everyday life: The complex simplicities of the mundane. Michigan: Open University Press.

Murdoch, J. (1998). The spaces of actor–network theory. Geoforum 29, 357–374. doi:10.1016/s0016-7185(98)00011-6

Paukaeva, A., Setoguchi, T., Luchkova, V., Watanabe, N., and Sato, H. (2021). Impacts of the temporary urban design on the people’s behavior: The case study on the winter city Khabarovsk, Russia. Cities 117, 103303. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103303

Pinder, D. (2008). Urban interventions: Art, politics and pedagogy. Int. J. Urb. Reg, Res. 32 (3), 730–736. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00810.x

Rossini, F. (2019). Temporary urban intervention in the vertical city: A place-making project to re-activate the public spaces in Hong Kong. J. Urb. Des. 24 (2), 305–323. doi:10.1080/13574809.2018.1507674

Sennett, R. (2009). Urban disorder today. Br. J. Soc. 60 (1), 57–58. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.01215.x

Sharif, A. (2016). Sustainable architecture, interactions and mutual relations: A case study of residential building facades. J. Sus. Build. Tech. Urb. Dev. 7 (3), 146–152. doi:10.1080/2093761x.2016.1237395

Sharif, A. (2019). Transfer ethnography: The recording of a heritage building. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Arch. Res. 14 (2), 289–302. doi:10.1108/arch-02-2019-0039

Sharif, A. (2020a). User activities and the heterogeneity of urban space: The case of Dahiyat Al Hussein park. Front. Arch. Res. 9 (4), 837–857. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2020.06.004

Sharif, A. (2020b). Users as co-designers: Visual-spatial experiences at Whitworth art gallery. Front. Arch. Res. 9 (1), 106–118. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2019.04.003

Sheehan, R. (2011). Actor-network theory as a reflexive tool: (Inter)personal relations and relationships in the research process. Area 43 (3), 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01000.x

Skytt-Larsen, C., Busck, A., Lamm, B., and Wagner, A. (2022). Temporary urban projects: Proposing a multi-positional framework for critical discussion. Front. Sustain. Cities 4, 722665. doi:10.3389/frsc.2022.722665

Tardiveau, A., and Mallo, D. (2014). Unpacking and challenging habitus: An approach to temporary urbanism as a socially engaged practice. J. Urb. Des. 19 (4), 456–472. doi:10.1080/13574809.2014.923743

Tornaghi, C., and Knierbein, S. (2015). “Conceptual challenges: Re-Addressing public space in a relational perspective,” in Public space and relational perspectives: New challenges for architecture and planning. 1st ed. (London: Routledge), 13–16.

Tornaghi, C. (2015). “The relational ontology of public space and action-oriented pedagogy in action,” in Public space and relational perspectives: New challenges for architecture and planning. Editors C. Tornaghi, and S. Knierbein 1st ed. (London: Routledge), 17–41.

Wagner, A. (2016). Permitted exceptions: Authorized temporary urban spaces between vision and everyday. PhD dissertation. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

Wohl, S. (2017). Tactical urbanism as a means of testing relational processes in space: A complex systems perspective. Plan. Theory 17 (4), 472–493. doi:10.1177/1473095217722809

Yaneva, A. (2017). Five ways to make architecture political: An introduction to the politics of design practice. London: Bloomsbury.

Keywords: actor-network theory, urban intervention, user activities, relational patterns, spatial temporality

Citation: Sharif AA (2023) Exploring temporary urban interventions through user activities: a case study of Abdali Boulevard, Amman, Jordan. Front. Built Environ. 9:1161856. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1161856

Received: 08 February 2023; Accepted: 19 April 2023;

Published: 04 May 2023.

Edited by:

Krushna Mahapatra, Linnaeus University, SwedenReviewed by:

Yreilyn Cartagena, University of Huddersfield, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Sharif. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahlam Ammar Sharif, YWhsYW1fc2hAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.