95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Built Environ. , 09 May 2023

Sec. Urban Science

Volume 9 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2023.1154437

This article is part of the Research Topic New Approaches for Sustainable & Resilient Processes and Products of Social Housing Development in the Arabian Gulf Countries View all 13 articles

The Social Housing Program initiated by the United Arab Emirates Government in 1971 aimed to upgrade the living conditions of the local Emiratis. The early housing projects were later known as Shabiyat. Individuals living in harsh conditions in the mountains of Ras Al Khaimah were willingly and within a short period relocated to new houses an approximate distance from their original homes, and they had to adapt to the new lifestyle and place. Due to changes in these individuals’ everyday practices, they questioned the resilience of their new houses. This study aimed to investigate the degree of resilience of the early Shabiyat housing and examine the notion of home mobility and how it is related to resilience through physical and nonphysical spatial transformation and everyday practice. The study is structured into two sections: first, understanding the resilience of the traditional settlements in the mountains; and second, examining the main characteristics of early Shabiyat, its main concept, and how it has addressed the Emirati society’s needs. This will assist in tracing these structures’ patterns of resilience and offer some practical guidance for professionals and the public in developing policies toward maximizing the sustainability of proposed future social housing projects.

Spatial transformation is one of the main themes of the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) modern history. “Now and then,” “tradition and global,” and “nostalgia and progress” were joined to form a new hybrid concept that became the main feature of the cityscape. Since the 1970s, local communities have strived for more satisfying spatial modalities reflecting the modern lifestyles rooted in their traditions and cultural values. This has resulted in hybrid spaces where modernity and tradition are in a continuous negotiation producing places that do not belong to either, where modernity, tradition, and resilience are in continuous debate.

This transformation in the UAE was initially caused by the increase in sales of petroleum and the emergence of the nation-state in 1971, resulting in vast changes in mobility patterns (Ahmed, 2011). One of the major projects during this period was the public housing program introduced to the UAE people as a gift from Zayed1, their respected and beloved first sheik. This program aimed to offer good housing for all, wherever they were located. As a result, individuals experienced significant transformations that affected every aspect of their lives. The housing program changed the way they lived, worked, and the places in which they stayed. For example, walkable informal neighborhoods were replaced with planned modern ones based on an orthogonal network to accommodate automobiles. The rise of the state created new work opportunities for the Emiratis, and the modern infrastructure allowed for more exposure to new ideas and forms to be integrated into the formation of their environment.

Since its initiation, the housing program has attempted to respond to the changing needs and lifestyle of the local community and their aspiration to join the global modern world. Many of these housing clusters have provided infrastructure and adequate services, including electricity and telecommunication services. Additionally, a mosque was built in each neighborhood, and open public spaces with shops for everyday requirements were included in the planning.

These public housing units have been repeatedly assessed to address and consider the community’s needs in proposed housing units, and several limitations have been found2. The early houses were small in size and built for emergency cases to house as many individuals as possible. Additionally, concrete was used to build these houses, which has a relatively shorter life span than stone. Furthermore, no regular maintenance was conducted on these housing units.

Within this context, this study assessed the resilience of the early Shabiyat housing units and compared their resilience with traditional houses in the mountains. The assessment was conducted both in-person and virtually at different social, architectural, and urban levels.

To deepen the understanding of the resilience of Shabiyat housing units, it is necessary to understand the process of spatial transformation of home mobility in its physical and nonphysical terms and its effects on new spatial lifestyles that have different degrees of confronting modernism. In his book “The Present Past,” Huyssen (2003) identifies that it might be impossible to distinguish between the mythic past (the imagined one) and the real past (the existing one). This idea was also relevant to Sheshtawy (2019), who considered Sha’abi3 houses a perfect medium through which to explore and unpack issues related to identity, encounters with modernism, and the practice of self-resilience in what he called a struggle between the past and present. It is an attempt to reconcile modernism and its legacy occurring in the politicization of memory. This debate opens the discussion regarding community resilience, including individuals’ abilities to learn from experience, prepare, and cope with disturbances. However, Al Nakib (2016) posits that the rapid transformation of the urban landscape gave rise to a radically different lifestyle affecting everyday lives and resulting in a fragmented space (Limbert, 2010). Neher and Miola (2016) and Alawadi (2018) describes how individuals readapted and appropriated these spaces over time to meet their daily needs and routines. Cultural resilience is considered the capability of a cultural system (consisting of cultural processes in relevant communities) to absorb adversity, deal with change, and continue to develop (Folke, 2006; Thieli, 2016; Holtorf, 2018; Touqan, 2020).

Community resilience is an integral part of the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda, as well as the Council of Europe’s mission4. It started from the concept of Heritage Community (Bokova, 2021) and was elaborated in the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society.

The process of transformation and its effect on the resilience of Sha’abi houses can also be discussed through the transformation of mobile homes, where this transformation is caused by temporal and spatial changes, resulting in what is called home displacement. Constructing homes in displacement requires the critical reevaluation of the relationship between home and displacement from a spatial, material, and architectural perspective. Recent studies in the social sciences have examined how displacement created and reproduced homes under new conditions, thereby uncovering the contradictory positions of making a home and overcoming its loss, whether they are physical or nonphysical (Norris, 2020; Beeckmans et al., 2022). Cooke (2014) has used the term “tribal modern,” reflecting his doubt regarding this transformation, which he called a clash between modernism and archaic ideas in the Gulf. He uses the term tribal modern to question whether tribal and modern can be intertwined or if they clash. The notion of displacement is also related to the nostalgia discourse, which affirms an authentic Emirati cultural identity, local rootedness, and separation from the foreign majority. Kanna (2011) has identified nostalgia for “the vanished village” as a key component of the “neo-orthodox” side of Emirati nationalism.

In the 1990s, mobility research started to translate the concept of lifestyles into “mobility styles” (Lanzendorf, 2002; Scheiner and Birgit, 2003; Götz and Ohnmacht, 2011); however, it is normally limited to modal choice. Scheiner and Birgit (2003) have focused on the interrelation between social structures (lifestyles, milieus), space–time structures, housing and choice of housing location, and daily mobility. They argue that spatial mobility was mainly based on spatial and individual restrictions. Neither the increasing degrees of freedom nor the subjective rationales behind mobility decisions were adequately considered (see Table 1).

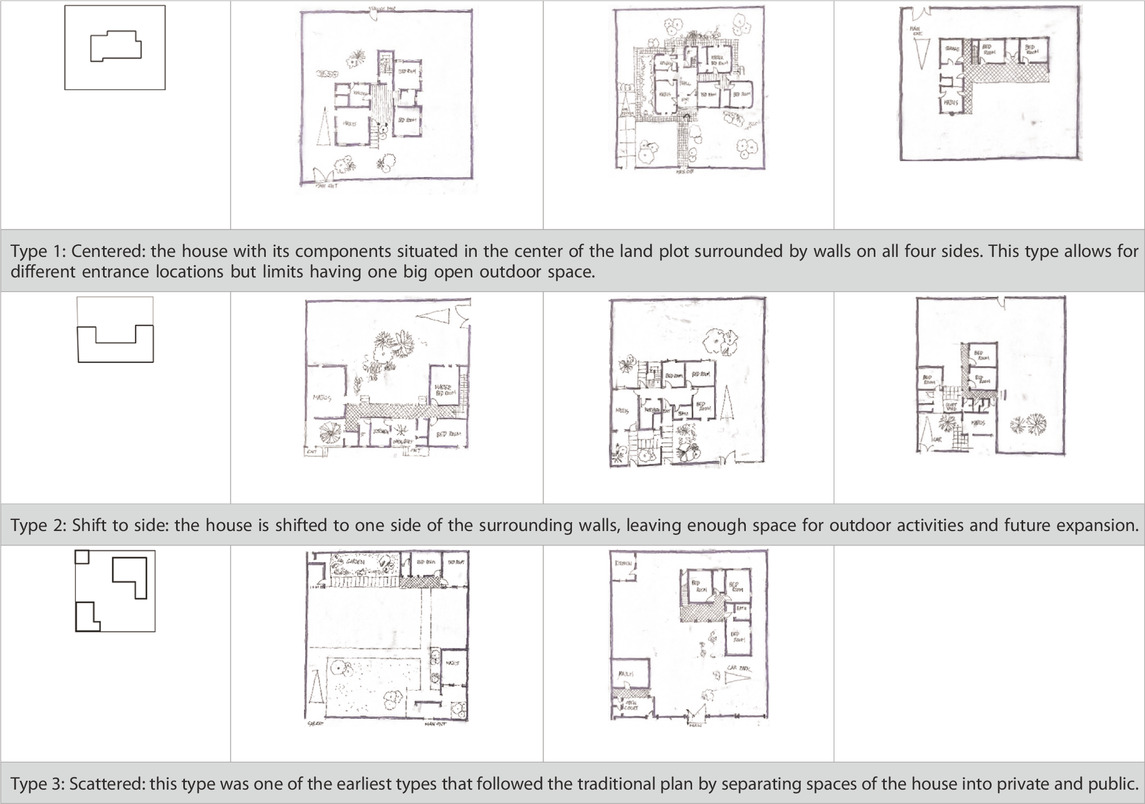

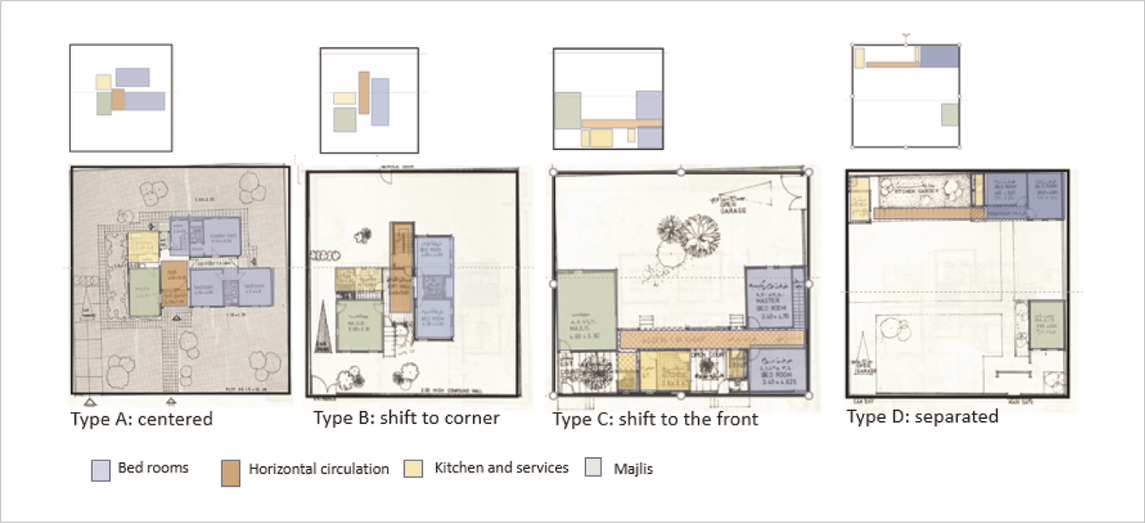

TABLE 1. Different typologies of Sha’abi houses that were implemented in the UAE in 1970–1990, source: Ministry of Public Housing, UAE.

This study contributes to previous literature reports by focusing on other dimensions of the physical and nonphysical transformation of Shabiyat housing and how this transformation, as a process and output, affects its resilience compared to the traditional settlements in the mountains.

Resilience is the main topic of discussion in this study. The study is structured into three sections: first, understanding the indigenous settlement in the mountains of Ras Al Khaimah; second, understanding Shabiyat housing; and third, assessing the change in the resilience of the early social public housing provided to communities who were living in the mountains of Ras Al Khaimah. This study combined qualitative and ethnographic approaches, building on theories of spatial transformation and displacement to understand why and how individuals’ new spatial lifestyle impacted the resilience of their houses. Using archive data from the National Archive Centre of Abu Dhabi, surveys and data on case studies and interviews with individuals were obtained to understand the context of Shabiyat housing and the living experience of its residents. In-depth interviews of residents with different backgrounds, including both men and women who used to live in the four selected areas, were also included.

Four case studies were selected to analyze the indigenous settlement in the mountains. Data were collected through several site visits, personal observation, and long interviews with people who used to live there. The study aimed to respond to the following questions:

Section 1: Understanding the indigenous houses in the mountains.

a. What is the typology of the houses regarding their plans, boundaries, shape, and materials?

b. What is the relationship of each house to the rest of the group?

c. What are the main sources of income?

Section 2: As per the selected model of 18 Sha’abi houses, the following questions were asked.

a. What is the main typology of the house regarding its

i) location to the rest of the block,

ii) relationship of different spaces within the house, and

iii) architectural characteristic if it was inspired by tradition and materials?

Section 3: Focusing on the assessment of change in Sha’abi houses according to the following traits:

a. Physical transformation: Regarding spatial transformation in the Sha’abi house, what additions were made to the house, and what were the reasons for such changes?

b. Non-physical transformation: How did the transformations relate to the everyday practices and lifestyles of residents?

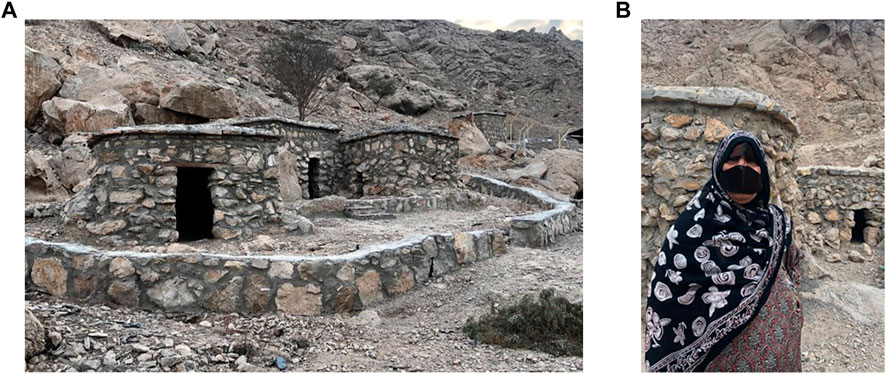

The top of the range of mountains in the Musandam Peninsula in Eastern Arabia constitutes a distinct geological, geographical, and ecological unit and has correspondingly more distinctive flora than has generally been recognized (Feulner, 2011). It is 1,500–2000 m of carbonate peaks and plateaus of the Musandam Peninsula. The mountains were inhabited by two tribes: Al Hubus and Alshehhi. Both tribes had lived in these mountains for a long time and had established a very resilient livelihood, enabling them to survive in harsh conditions with limited resources. The main concept for their resilience lay in their flexibility in adapting to the changing environment and their independence from outside resources as everything made was locally produced. They built stone houses from local materials attached to the mountain’s edge to protect themselves and their animals from the cold winter weather. They minimized the exposure to the wind by building their houses without windows and half a meter under the ground level. The houses were covered with Areesh over palm fronds, and they left these houses in the summer to look for food for their animals. The people lived and moved in groups and supported each other through various jobs and duties. They formed very strong social groups based on their tribal structure. The houses were grouped together, sitting on the edge of a hill in a natural organic composition, and no clear boundary separated the village from its surroundings. Each house had an outside terrace with low stone walls defining the family’s private space. Additionally, no particular walls surrounded the houses; however, each specific function had its own separate space (Figure 1).

These villagers’ main income came from their goats, which provided milk and food throughout the year. Both men and women shared the work responsibilities of earning a living (Rashed, 2013). Women worked with pottery, gathered honey, and herded and milked the sheep twice a day, in the morning and the afternoon. Additionally, they baked bread and prepared food for the family.

Um Ali is a woman in her 70s and a mother of eight who had lived in the mountains before her family was offered a public housing unit in 1976. She said:

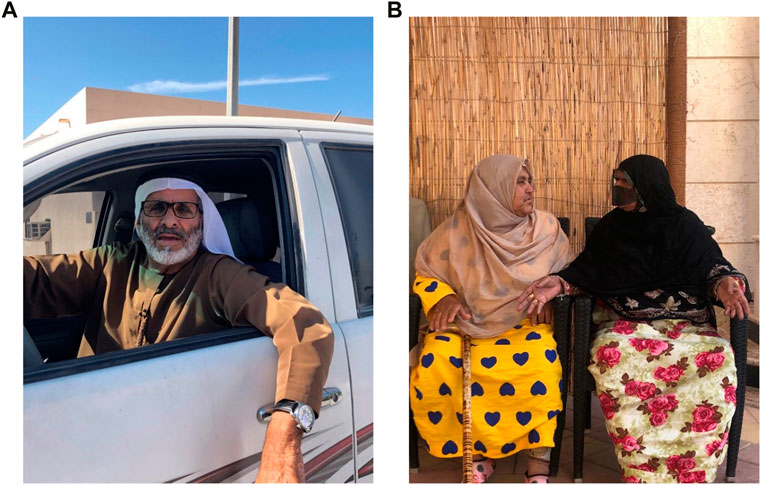

Every day I used to wake up early in the morning to take care of the goats, make bread, bring water from wells in the mountains, and then work in pottery. I used to produce plates and cups and sell them for 2 AHD dirhams. It was a hard job, but I liked it. To make pottery, I had to collect clay and filter it and take the smooth particles and add water to produce a paste that I could work with (Figures 2A, B).

FIGURE 2. (A) Indigenous house groups in the Bana area (B) Um Ali, who used to live in the indigenous houses of the Bana area, talking about her memories.

In Abdel Alrahman (2013), Abu Rashed described the old days in the mountains and the making of pottery. He said:

Making pottery is really hard, and it is a locally excellent product: the material, the making, and the selling. It takes all day to produce it by collecting the materials, preparing them, molding them, and burning them in rocky furnaces. There used to be 40 furnaces scattered in the mountains, and their ruins are still there (Abdel Alrahman, 2013).

Furthermore, in Abdel Alrahman (2013), Thulab Ajab Almansori described animal farming in the mountains:

Sheep was the most important wealth for the Emiratis. It is very useful. It provided them with food (milk and meat). Every person used to own tens of them and spent a lot of time protecting them from the wolves and wild animals in the mountains and moving from one place to another in search of water and food (Abdel Alrahman, 2013).

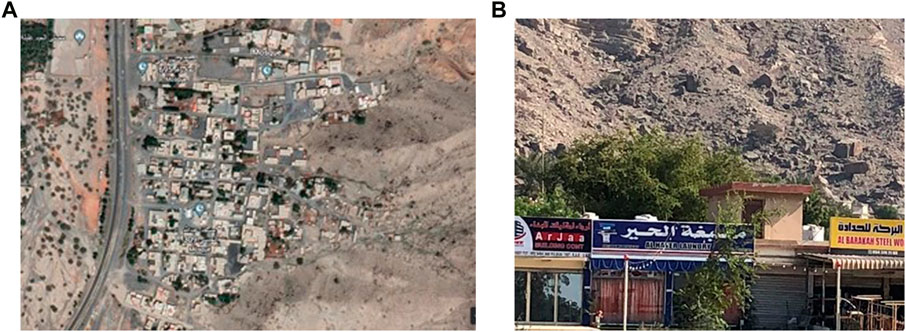

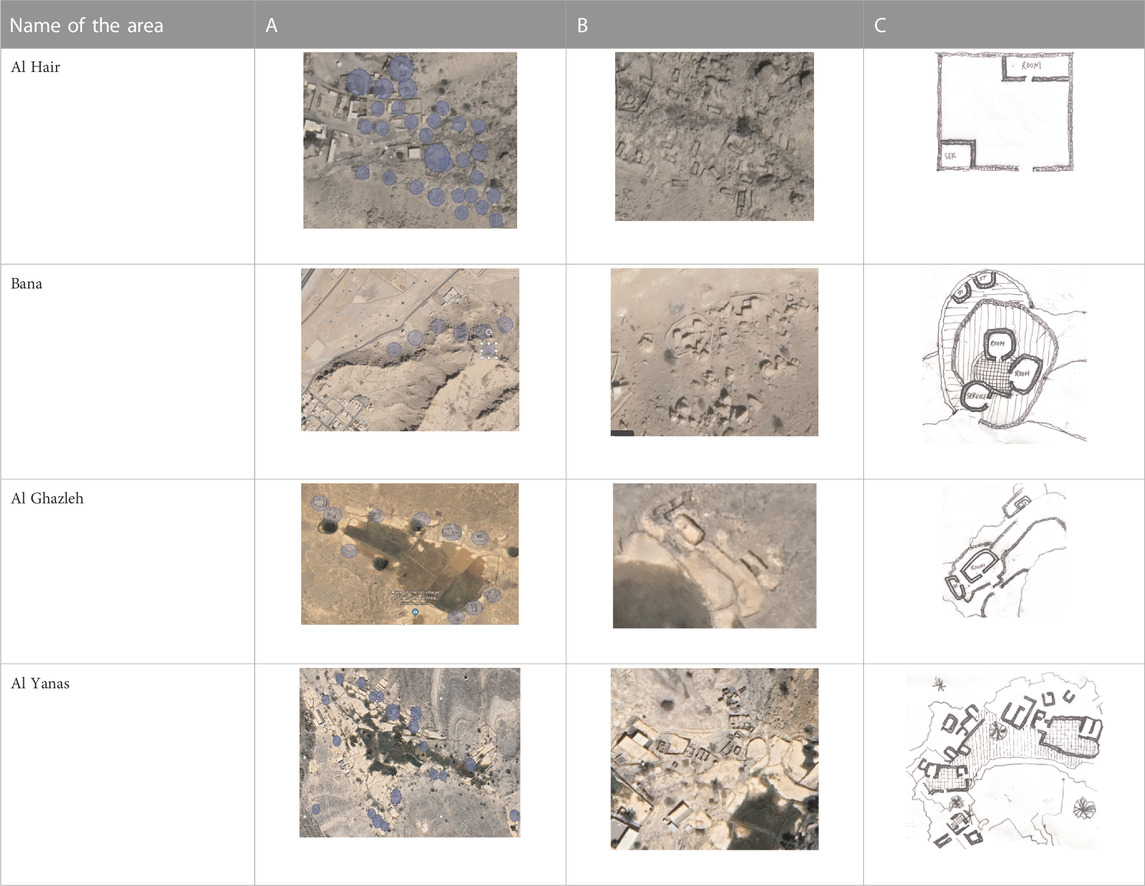

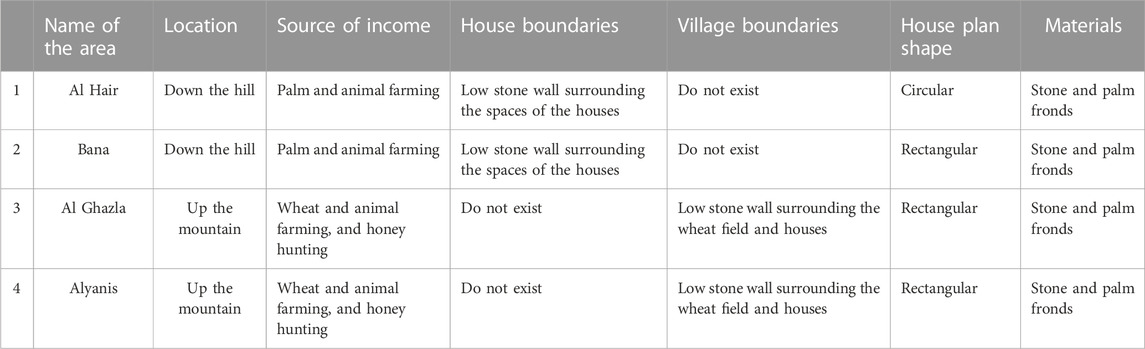

The analysis was conducted on four areas of indigenous settlements in the mountains. Alghazle and Alyanas are located at the top of the mountains, and Alhair and Bana are located down the valley. Alhair is located on the off-road to Oman. It is the site where most of the houses were demolished and deserted. The new Sha’abi was developed next to it. Some plots were newly surrounded with walls to define the property boundaries. Bana is a group of round, terraced houses down the mountain. The spaces of the house are separated and have different functions; sleeping rooms are located on the upper terrace, and the service and storage sections are located on the lower level. Al Ghazleh is a village located at the top of the mountains looking over the wheat fields. Horizontal plains were created to take advantage of the rainwater passing from higher areas. The terraced stone houses are grouped around a wheat field. Alyanas is a village at the top of the mountain where the wheat fields are located. It is relatively larger than other villages and comprises separated wheat farms, following the topography of the land. Every field is surrounded by a group of houses, and the residents thereof are responsible for wheat farming. Most of the houses are rectangular in shape.

In the 1970s, the founder of the UAE, Sheikh Zayed Al Nahyan, initiated a housing program5 aimed at offering decent housing for low-income families living in either temporary accommodations or harsh environmental conditions, such as individuals living in the mountains (Maclean, 2016). The program, funded by the federal government, is still running and provides different options to all UAE citizens. In Ras Al Khaimah, a new planned area of medium size and equal plots was designed to have the same types of housing plans scattered in the different regions according to the relative proximity of their locations. The individuals living in the mountains were given units in the valley, while the individuals living in the desert were given units inland or near the sea.

The early Shabiyat in Ras al-Khaimah was implemented in 1973. According to the “Alithad” newspaper, 520 houses were built in the inland villages and mountains. Of these, 120 houses were for the Alhubus families who lived in the mountains of Ras Al-Khaimah, another 40 housing units were provided in the Shamel area near the sea, and 20 housing units were provided in Albrairat down the mountains. Each house was approximately 90 square meters in area and comprised two bedrooms, a majlis6 (a sitting room), a kitchen, and services. The aim was to provide a healthy environment for all Emiratis, wherever they were, as a gift from Sheik Zayed (Tables 1, 2).

TABLE 2. Different relationships of spaces in a Sha’abi house according to the typology explained in Table 1.

According to statistics compiled by the Ministry of Public Works, the program started with small-sized housing units of approximately 108 square meters, including two bedrooms and a majlis on a plot size of 900 square meters. In the 1990s, these units were enlarged to a two-floor housing plan of 367 square meters on a plot size of 1,620 square meters, with four bedrooms, a living room, and a majlis (Ahmed, 2011).

The housing units proposed by the government were divided into three broad categories: free ready-made housing units for groups of low-income citizens, houses built by the owner through financial grants with plots of land suitable for building private accommodation (such grants were also available for nationals who wished to expand their existing living area), and long-term (up to 25 years), nearly interest-free, loans offered to citizens with the financial capability to repay them.

Different models of housing units were implemented in different areas. The main idea remained the same: a design solution that addressed the cultural values of the community and integrated their needs into the plans and layout. Some of these considerations were to have a large outdoor area in each plot to allow for future extension and possible additions. The spaces of each house were organized according to their function and level of privacy. The majlis was located near the main entrance, the kitchen and service areas were separated from the bedrooms, and a shaded area linked all spaces together similarly to a traditional liwan7 (entry hall). Additionally, a staircase led to the roof, which provided seating during the hot summers. Some architectural elements were used for aesthetics, such as a hollow-block screen separating the outside from the inside and allowing more privacy. These houses were designed to accommodate changes and become an expression of their residents’ culture and new lifestyle.

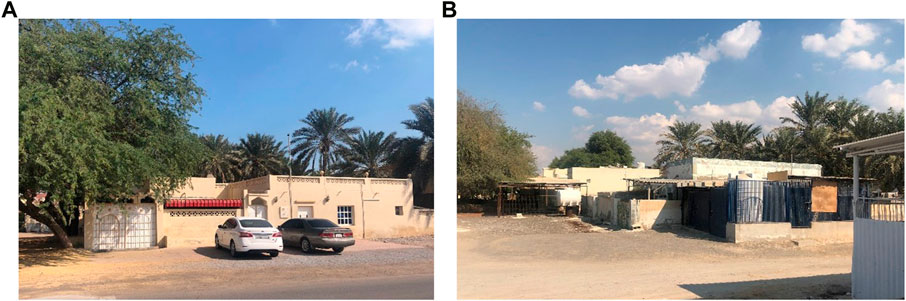

According to an interview with Mr. Ahmed Alabdoli, the vice president of the Ministry of Housing, the early housing model was an attempt to meet local needs by integrating traditional settings into the new proposed plans. Privacy was considered in many ways: two entrances were allocated for each house, one for the family and the other for the guests; an open area was provided for outdoor activities and to allow for future expansion; a shaded area was provided at the back of the house to reduce the heat of the sun on the exterior wall of the houses; and a staircase led to the roof to offer a space for sitting during summer8 (Figures 3A, B).

FIGURE 3. (A) Areal image of the Alhair area where Sha’abi houses were built next to indigenous houses (B) A few shops are located on one side of the Alhair Sha’abi house close to the main road.

The layout of the stone houses was naturally clustered in groups of houses in various distributions. Some stone mountain houses were clustered on a hill far away from rainwater, and others surrounded the wheat fields. The boundaries of each house were very simple and comprised half-meter-high stone walls.

The houses the villagers used to live in were also an example of resilience, allowing them to overcome the harsh climate, cold winters, and hot summers. The houses had separate spaces located on different terraces, one for the residents and a different terrace for their animals. These simple houses were built in rectangular and circular layouts, with one or two stepping terraces with different levels of privacy. Their own space was embedded in the mountains, covered with palm trunks and areesh (a wooden structure made from palm fronds). One traditional type of house, used only in the mountains, is called an “alkifl” or a “cave.” This type of house was sunk 1 m below the ground level of the front terrace, looking over the steep hills. The height of the roof of these houses was as low as 2 m to keep its inhabitants warm. Additionally, these houses had no windows and could only be entered from one small door (see Tables 3, 4).

TABLE 3. Different selected areas of indigenous mountain villages. Column A: Taken from Google Earth, the images show the location of indigenous houses in relation to the Sha’abi houses and how they are grouped. Column B: Images show the current condition of the houses, as shown from Google Earth. Column C: The most common plan found in the indigenous settlement.

TABLE 4. Analysis of the indigenous mountain villages in terms of location, source of income, boundaries of the house and villages, shape of the house, and construction materials.

Although a thoughtful attempt to consider cultural issues was implemented in the design of the early Shabiyat, they were not fully accepted by the residents as the new houses were built with concrete, bricks, and unfamiliar materials.

In this respect, when the residents were asked about their new houses, their feedback mainly focused on the construction system, based on block walls, a system considered unsuitable for today’s standards. The residents preferred beams and columns. They were also in favor of the high rooms or high exterior walls as they did not provide complete privacy. The residents’ feedback was considered in future housing plans regarding space, organization, and structural systems9.

However, the absence of regular maintenance of the Shabiyat negatively impacted its resilience. This was why almost 90% of the old Sha’abi houses, built in the 1970s, needed replacement, according to Mr. Fahed Abdel Aziz10the replacement of the house will be replaced if it is no longer good enough for living, there is no fixed time. Individuals either left their Sha’abi houses and built new rooms attached to them, or they conducted some minor maintenance to minimize the danger of the deteriorating materials11. This issue of a lack of maintenance has been covered several times in recent media12. Alrams’ digital forum mentioned that Sha’abi houses either needed serious maintenance or should be replaced by new ones13.

In May 2017, the Ministry of Public Housing issued an Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with consultants entitling every resident of Sha’abi houses built before 1990 a grant to either demolish their housing unit and rebuild it or to do maintenance if the structural system was stable and safe enough14.

Several changes were recently made to the early Shabiyat. Some houses were deserted as the residents left them for larger accommodations and more contemporary ones with two floors. Others were extended with many additions to the point where the original features were no longer recognizable. Some of the outdoor areas were replaced by other rooms to accommodate additional family members. The space in front of some housing units was covered by temporary materials and used as vehicle parking spaces. Several houses were inhabited by laborers, dividing them into small units using inadequate materials (Figures 4A, B).

FIGURE 4. (A,B) Transformation of a Sha’abi house in Ras Al Khaimah shows its physical deterioration and many additions to the original layout of the house.

Although the places to which they were relocated were not far from their original residences, the residents’ feelings changed tremendously as they felt that “something was missing.” With modern conveniences of electricity, water, and paved streets to commute more widely and easily, the boundaries of their territories became small and undefined in contrast to their previous ones. These conditions have changed the meaning that residents attach to their houses and how they interact with each other and nature15.

Often their attachment to their houses in the mountain made them return to them as a retreat or summer house. The Emiratis realized that to live and integrate into this modern world, they had to compromise with their past.

Um Ali, a woman in her 80s who used to live in the mountains, said:

I like it there up in the mountains. I have nice memories. I spent my entire life there doing pottery, feeding the sheep, and making bread for the family. Now, I am tired, I cannot go there even if I want to. Life is difficult there. Here, life is very easy.

The old stone houses were kept alive in the hearts and memories of the Emiratis. This past is part of their cultural identity, and it gave them strength and steadiness; furthermore, it is on this land where honey became money.16 Therefore, the residents decided to keep it alive through different modes and patterns; instead of perceiving the mountain as their source of income, it became their source of pleasure and joy. The Emiratis returned to the mountains and built their summer houses over or near their old houses. They even used the same old stones used to build their traditional houses. They integrated new construction techniques by using concrete in roofing and as a joining material between the stone courses. Furthermore, they respected the topography of the site and kept using terraces, similar to before, to define their different levels of privacy and territory. Now, they can face the future (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. One of the new houses constructed on the top of the mountain replacing the indigenous settlement.

There are two old Emirati sayings:

“Afsil behi aw ansil behi” and” Qallel wa Ammer.”

The first meaning is “in your youth, you have to grow trees or have kids.” The second meaning is “save to live more.”

These two sayings are familiar to the people who have lived in the mountains. The sayings indicate how resilient their communities were and how they managed to survive in the extreme conditions through their everyday practices. For many years before modernity invaded the Gulf, local communities in the mountains were thriving even though their lives were hard. Their indigenous culture taught them how to build their own houses, earn a living, and interact with each other and other communities.

Change is a crucial factor in assessing resilience. The UAE public housing, based on the relocation of the Emirati families, caused many changes due to their spatial proximity. Although local communities who used to live in the mountains were continuously moving during the year, their mobility was part of their traditional cultural system, ensuring their survival. In winter, they climbed up to their stone houses to look after their wheat farms in the stepped terraces called “Alwoob,” a traditional setting to plant wheat in the mountains, taking advantage of the fertile soil carried by rain. In summer, they returned to the mountains to harvest their fields and store the produce and sell the surplus. When the housing program was initiated in the 1970s, these individuals were relocated into the valley in clusters of 20–50 housing units17.

Physical and non-physical changes in the new environment were identified in this study. The physical changes included the architecture of the houses, their design, materials used, construction techniques, and layout. The nonphysical changes were identified through place attachment and the residents refusing or accepting the new houses.

The rapid transformation of the UAE’s urban landscape gave rise to a new meaning of place attachment and its nonphysical resilience. New concrete masses consisting of single-family houses intruded into the natural landscape in most of the UAE region. It was difficult for the local community to leave their original settlements as they were strongly attached and had strong memories of their lives there18; furthermore, they considered their original settlements as part of their identity that transmitted their memories to the next generation. Moreover, they had no attachment to their new Shabiyat houses. After they moved into Shabiyat houses, they were informed that these houses were temporary and that they would later leave them for better ones. For this reason, the residents did not have an issue with leaving the new houses or even demolishing them to be replaced with new ones (Figures 6A, B).

FIGURE 6. (A) Abu Salem, resident of an Alhair Sha’abi house. (B) Um Ali and her neighbor sitting in the new Sha’abi house.

The examples of mountain stone houses in Ras al-Khaimah are evidence of how the local people survived in the harsh mountain environment and were able to produce very authentic, resilient places in which they could transform nature from being their main challenge into an income resource. At the top of the mountains, local Emiratis planted and grew wheat on the stepped terraces, taking advantage of the winter rainwater to irrigate the field. Rainwater was also collected in man-made pools for their needs in summer. Wheat as a product became one of the sources of income where the efficient social system contributed to making it successful. Every individual had their duties, either irrigating the field, grinding the wheat, storing it in rocky silos, or selling the surplus to others. Other sources of income were honey gathering, pottery making, salt fish producing, and animal farming. This is a profound example of human adjustment to nature.

Early Shabiyat residential structures showed tendencies to be less resilient than traditional authentic settlements, where both physical and social resilience had profound influences in sustaining the structures. Shabiyat are considered transitional model houses, lacking the physical stability and social maturity to reach a resilient state.

An Emirati noted, “You must understand that our history is a history of gain and pain.” His point was that “traditional” or “authentic” Emirati identity was important in light of the country’s rapid development and the accompanying worldwide immigration of expatriates. Shabiyat housing units can be seen as a subjective field of memory and loss, where homes are a primary site of social resilience. The nostalgia discourse affirms an authentic Emirati cultural identity, local rootedness, and nostalgia for the mountain villages as a key component of the built environment’s resilience.

This study concludes that the resilience of old houses in the mountains is based more on their physical than nonphysical qualities. Social resilience is another dimension that indicates how structures can face any changes if strong attachments are formed. The challenges of home relocation and mobility cause a critical reevaluation of the relationship between home and displacement from a spatial, material, and architectural perspective. It is a spatial practice that intrinsically relates to the production of the built environment.

Further studies are recommended to find tools that can increase the resilience of Sha’abi houses. Research should further focus on the diversity of discipline by integrating human behavior with the collective memory of a place. There are some limitations to this study; the inconsistency and continuous changing of the Sha’abi program hindered our ability to trace the direction of resilience and whether it is going in the right direction.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

The author confirms being the sole contributor to this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1Al-Ittiḥād (1973), “Zayed’s gift to the People,” July 17, https://www.nla.ae

2Al-Ittiḥ;ād (1973), “How is the construction of public housing proceeding?” July 16. https://www.nla.ae

3Sha’abi is the singular of shabiyat, which is used as a collective.

4Convention on the value of cultural heritage for society, 2005, Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention

5Ministry of Public Works and Housing, UAE (1988) Dawr wizaret alashgal wa eskan fi altanmya (1988).

6Majlis is a guest room for men that usually has its own entrance. Most of the time, it is separated from the rest of the house for privacy.

7Al-Ittiḥ;ād (1973), “Houses for the People,” July 15; and Al-Ittiḥ;ād (1973), “Zayed’s Gift to the People,” July 17.

8Itihad newspaper, page 3 July 1973.

9Albayan newspaper, October 2022. https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/other/2017-05-18-1.996565

10Albayan newspaper, October 2022. https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/other/2017-05-18-1.996565

11Al Khaleeg newspaper, column by Hassa Saif, 21 March 2021. https://www.alkhaleej.ae/2021-03-28/

12Needs pavement, especially the secondary roads, of Shabiyat houses, Alrams, 21 July 2016. https://www.alrams.net/35595

13Emartat newspaper, 18 May 2017. https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/other/2017-05-18-1.996565

14An old woman who used to work in honey hunting said, “We use honey as money.”

15Al-Ittiḥ;ād (1973), “All the services … are for the Bedouins,” Jan. 30; Al-Ittiḥ;ād (1973), “How is the construction of public housing proceeding?” July 16.

16Ittihad newspaper, page 3, 6 September 1981.

17Alrams, 21 July 2016. https://www.alrams.net/35595

18Liwan is a semi open space located in front of the rooms looking over the open court house

Abdel Alrahman, A. (2013). Alimarat fi thakiret abnaiha. Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Authority for Tourism and Culture publication.

Ahmed, M. (2011). Globalization and architectural behavior in the united Arab Emirates: Towards reformation of humanitarian architecture. [PHD thesis]. England: University of Wolverhampton.

Al Nakib, F. (2016). Kuwait transformed: A history of oil and urban life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Alawadi, K. H. (2018). “Life scape beyond bigness,” in UAE national pavilion at the venice architecture biennale (Abu Dhabi: Artifice Press).

Beeckmans, L., Gola, A., Singh, A., and Heynen, H. (2022). Making home(s) in displacement: Critical reflections on a spatial practice. Belgium, Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Bokova, I. (2021). “UNESCO’s response to the rise of violent extremism,” in A decade of building international momentum in the struggle to protect cultural heritage. Editor J. Paul Getty (Los Angeles: Cultural Heritage Policy). Avaliable At: https://www.getty.edu/publications/occasional-papers-5/3/.

Cooke, M. (2014). Tribal modern: Branding the new nation in the Arab Gulf. California: University of California Press.

Feulner, G. (2011). The flora of the Ru'us al-jibal -the mountains of the Musandam peninsula: An annotated checklist and selected observations, tribulus. J. Emir. Nat. Group (83). Jerusalem: Insitute for Palestinian Studies. Avaliable At: http://enhg.org/bulletin/b25/25_13.htm.

Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 16, 253–267. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

Götz, K., and Ohnmacht, T. (2011). “Research on mobility and lifestyle—What are the result?”,” in Mobilities: New perspectives in transport. Editors M. Grieco, and J. Curry (London: Routledge). doi:10.4324/9781315595733

Holtorf, C. (2018). Embracing change: How cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeol. 50 (4), 639–650. doi:10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340

Huyssen, A. (2003). Present Past: Urban palimpsest and the politics of memory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University press.

Kanna, A. (2011). “The city-corporation: Young professionals and the limits of the neoliberal response,” in Dubai, the city as corporation (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press). doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816656301.003.0005

Lanzendorf, M. (2002). Mobility styles and travel behavior: Application of a lifestyle approach to leisure travel. Transp. Res. Rec. 1807, 163–173. doi:10.3141/1807-20

Limbert, M. (2010). In the time of oil: Piety, memory, and social life in an Omani town. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Maclean, M. (2016). Suburbanization, national space and place, and the geography of heritage in the UAE. J. Arab. Stud. 7, 157–178. doi:10.1080/21534764.2017.1464717

Neher, F., and Miola, A. (2016). JRC technical report on culture and resilience. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Norris, J. (2020). Mobile home: The relationship of Palestinian merchant homes in the late ottoman period. Jerus. Q. 83, 3–31.

Scheiner, J., and Birgit, K. (2003). Lifestyles, choice of housing location and daily mobility: The lifestyle approach in the context of spatial mobility and planning. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 55, 173–363.

Sheshtawy, Y. (2019). The Emirati Sha’bi House: On transformation, adaptation and modernist imaginaries. Int. J. Archaeol. Soc. Sci. Arab. Penins. 11, 11. doi:10.4000/cy.4185

Keywords: social housing, resilience, spatial transformation, lifestyle, adaptation, mobile home

Citation: Assi E (2023) Gain and pain: resilience of home mobility in early Shabiyat housing of Ras Al-Khaimah. Front. Built Environ. 9:1154437. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1154437

Received: 30 January 2023; Accepted: 17 April 2023;

Published: 09 May 2023.

Edited by:

Khaled Galal Ahmed, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Mahua Mukherjee, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Assi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eman Assi, ZW1hbi5hc3NpQGF1cmFrLmFjLmFl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.