- 1Department of Computer and Geospatial Sciences, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

- 2Department of Architecture and Environmental Design, Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

- 3Department of Architecture and Planning, Dawood University of Engineering and Technology Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

Bazaars have always been a center of social, economic, and cultural exchange. Bazaars as public spaces were responsible for creating an ideal public setting to enhance social interactions for everyone. However, over a period of time, the concept of Bazaars has changed. Modern shopping centers seem to be an appropriate alternative to bazaars in terms of accessibility, quality of space, maintenance, sense of safety and security, and leisure activities. Karachi, being the commercial hub of Pakistan, hosts a load of business centers and marketplaces around the city. However, parts of the old bazaars in Karachi have been slowly destroyed to make room for wider streets and roads in Karachi, and new forms of shopping centers have been emerging across the city. This research will investigate the preference of people for traditional bazaars vs. shopping centers and the attribute of shopping centers that aided in their preference. This aim will be achieved by 1) understanding the evolving concepts of public spaces in Karachi and 2) investigating people’s preference for shopping centers vs. Bazaars and the impact of services offered by shopping centers on user satisfaction. A comparative case study technique is used. Data is collected through an online survey in relation to a traditional bazaar and a newly built shopping center in Karachi, Pakistan. The finding results show that the success of shopping centers is generally influenced by indicators like atmosphere, safety, accessibility, and leisure activities while people visit traditional open street bazaars in Karachi for the economical prices and accessibility to public transportation. On the other hand, the avoiding behavior of users towards traditional bazaars is reported due to narrow pathways, unmaintained environment, no parking and toilet facilities, and a large influx of people. Although these results are not the first ones in the literature, they are new in relying on findings from a cosmopolitan city in Pakistan. Finally, this study provides some recommendations that can serve urban planners and other practitioners to integrate these indicators at the earliest conceptual design phases when planning and managing open street bazaars in developing countries.

1 Introduction

“Shopping has become one of the most significant modern leisure activities, as well as a dominant way of public life” (Goss, 1993). The beginning of the twenty-first century was a game-changer for several countries worldwide (Chismon, n.d.). Rapid lifestyle change was brought on by economic restructuring and rising per capita incomes in various nations. Shopping centers are now preferred by those who used to spend a significant portion of their time in traditional street bazaars for social activities and retail therapy. People’s preferences for shopping are driven by changes in not only lifestyle (Al, 2016) and motorized transportation patterns but also leisure activities, space quality, and the experiences these multi-user retail spaces provide.

The concept of city’s public spaces is associated and affected by the way people feel in them (Iqbal, 2021). The idea of shopping malls/centers came from the transformation of street markets into a larger form that houses everything under one roof to provide urban residents with rich and varied social experiences. This is an attempt to build public places that could act as communicative arenas. Shopping centers have produced new public areas for leisure and lifestyle that support the logical commercialization of consumer behavior (Ghosh and McLafferty, 1987; Garreau, 1992; Banerjee, 2001; Erkip, 2003). Customers go to the air-conditioned environs to shop in comfort. With multiplexes, food courts, and gaming areas (Terblanche, 1999), they gradually transformed into a place for entertainment, ensuring that a mall/center had something to offer everyone (Miller, 1998). Creating an intriguing space with appealing architecture and interior design that leaves a memorable and distinctive impression on visitors is the other purpose of the shopping center (Rajagopal, 2010). Shopping centers fulfill two purposes: one is as a building for goods and the other is as gathering place for people. The latter has taken up a significant role in the urban environment and has developed into sites of localization of new lifestyles and intense social relationships among visitors as city dwellers explore and welcome these new forms of public space. On the other hand, Traditional street bazaars that were once the center of social and commercial activities has lost their value and place around the world specially in developing countries such as Pakistan.

In Pakistan, bazaars have evolved from traditional open street to vertical multi-story urban malls that are free from the hustle and bustle of street life and harsh weather realities and provides other leisure activities in a safe place for the consumers. Citizens’ acceptance for one another, especially those ignored by contemporary, educated groups, seems to grow in these spaces that establish a new type of public space (Erkip, 2003). Although users’ preferences about visiting shopping mall/centers is growing, a gap remains in the literature about shopping mall vs. traditional street bazaar. The fact that these questions have been primarily raised by Iranian researchers highlights a great gap in other developing countries. To address this gap, and to pursue new knowledge on understanding the differences between user’s preferences for both shopping typologies (mall and bazaar), the goal of this study is to understand and analyses the shopping mall as an emerging concept of public space in the context of the changes to urban life in Karachi from the user’s preference perspective. What influences where individuals go shopping in Karachi? Why would individuals choose to be at a particular shopping center over the city’s specific open street bazaar? Answers to these questions are important and will be attained by 1) understanding the evolving concepts of public spaces in Karachi 2) investigating customer’s preferences for shopping centers vs. Bazaars and the impact of services offered by shopping malls on user’s satisfaction. For instance, how people perceive shopping centers or traditional bazaars from four indicators: atmosphere by analyzing quality of space and maintenance (Anselmsson, 2006; Rajagopal, 2010), sense of safety and security (Velashani et al., 2015; Ceccato and Tcacencu 2018), convenience or accessibility (Anselmsson, 2006; Rajagopal, 2010), and leisure activities (Banerjee, 2001; Frasquet et al., 2001; Erkip, 2003). A case study of a recently built shopping center close to a middle-class and upper-class suburban area (Lucky One Mall), and a case study of Karachi’s traditional and oldest bazaar (Jodia Bazaar, 2021) were used to investigate and analyze the qualities of the mall and bazaar that draw people to them and the preference of people towards shopping center vs. bazaar. The selection of these two cases is based on the most famous shopping facilities in Karachi. Jodia Bazaar is one of the biggest and oldest bazaars in Karachi, while Lucky One is one of the most modern and biggest shopping center.

2 Theoretical background

Through the ages, cities have grown rapidly with the increase in population. By 2025, it is predicted that half of the world’s population will be living in cities UNICEF (1996). People who live in urban regions appreciate public spaces as an essential component of the urban environment in their everyday lives. According to Walzer (1986), public space is where we interact with strangers and individuals outside our family members, friends, or co-workers. A public place is an arena for politics, religion, trade, and sports, as well as peaceful sharing and impersonal meetings. This means that public spaces promote people to connect and interact with one another freely (Duyvendak and Wekker, 2015). By influencing our psychological, social, political, cultural, symbolic, environmental, etc., public spaces represent and shape our public life, civic culture, and daily dialogue (Walzer, 1986). Furthermore, public spaces provide “a shelter, a place to sleep, to rest, and a place of fellowship and togetherness for homeless people” (Mitchell, 2003). Public spaces have been an essential part of cities, from the agora of the acropolis and marketplaces of mediaeval cities to current modern shopping centers, commercial arenas, and open sites for festivals. However, the characteristics of public spaces differ widely throughout history, showing how people change, how they live and shape their spaces. According to Lee (2022), new sorts of public spaces emerge as more public areas are co-produced by many stakeholders. These spaces are either private public spaces or semi-public spaces. Private public spaces have gained popularity for several reasons like proper security and good management, provision of all facilities, good and controlled gentry, no overcrowding, etc. Weaver (2014) mentioned that people feel comfortable in private public spaces since they are regularly maintained and clean. However, one of the main drawbacks of private spaces is that they often exclude specific groups and allow selective activities (Loukaitou-Sideris, 1993). Additionally, the private sector contributes to the maintenance of these private public spaces rather than the local government (and taxpayers), which burdens the users by charging a heavy amount. On the other hand, public spaces created by the private sector are also criticized for emphasizing profit-making and targeting commercial events (Whyte, 1988). They are criticized for serving themselves as a commodity rather than the common good of society (Minton, 2022).

Therefore, Lofland (1989), defined another type of place, that is semi-public space, which is neither entirely confined nor a “world of strangers.” Every neighborhood has several semi-public places, including community centers, libraries, cafes, corner shops, schoolyards, playgrounds, and shopping malls. These places, also referred to as “micro publics” by Amin (2002), as places where people from different cultures can interact. They are significant because they provide chances for interdependence and habitual participation. These places encourage people to interact and connect despite their differences to achieve a shared objective (Amin, 2002). Environments themselves have a significant impact on how individuals interact. According to Van Eijk and Engbersen (2011), four essential factors—multifunctionality, connection, comfort, and sociability—are related to how individuals interact in semi-public spaces.

Since bazaars and shopping malls are two examples of public spaces that significantly influence peoples’ way of life. Bazars come under the umbrella of open public spaces that have no restrictions for their users. According to Rajabi (2009) the emergence of bazaars can be traced to the early settlement of tribes, which resulted in the establishment of a variety of bazars. The term “bazaar” emerged from an Old Persian term that refers to a “place of prices.” “Bazaarro” is a comparable term in Italian (Bazaar market Britannica, 2020). However, the definition of “bazaar” varies from nation to nation (Newworldencyclopedia.org, 2019). Middle Eastern or Asian nations describe an open market that sells various products, including food, spices, home goods, etc. (Pirnia and Memarian, 2005). In western nations, like the United States, the term is used to describe a flea market that offers a wide variety of items for sale. In the United Kingdom, the term has a different connotation and is used to describe stores that sell a variety of donated or used products for charity, typically associated to churches (Difference between bazaar and flea market, 2013). However, bazaars quickly became essential for more than just exchanging items; they were frequently towns’ social, cultural, religious, and financial hubs (Mir Salim, 1996). The bazaar still evokes memories of the majesty of Muslim metropolis, despite changes in society and urban planning (Rouz, 2014). According to Raeesolmohadesin and Alipoor (2012), a traditional bazaar is intended to stimulate all of the senses like the hustle and bustle of large crowds and a wide variety of goods in unique architectural spaces covered by highly ornamental and colorful awnings or sheds; the shouting of porters to the crowd to move out of the way as they transport the goods; the haggling of customers with sellers over the price of goods; the smell of various spices, odors, and perfumes; and the touching of different textured fabrics and textiles draped over the buildings. Additionally, bazaars were first only in the open air, but as time passed, they began to be covered as well, making them useful in all types of weather.

However, as modernity, economic growth, security concerns, no maintenance and proper facilities, overcrowding, and traffic congestion emerge, traditional bazaars that were not only served as places for purchasing the goods but also the hubs of all social or cultural events and activities that make them vibrant public places are deteriorating and dying (Mehdipour and Rashidi 2013). They no longer serve any social role in the lives of the locals as they once did. In addition, in many countries, portions of the ancient bazaars have been gradually dismantled to make way for broader streets, roads and high-rise structures. Additionally, as cities expand, there is more need for production and consumption-based land use in urban areas. Therefore, most cities in these circumstances have not only changed the land-use of public places for other purposes but also neglected to maintain public places for social interaction, especially existing open spaces and traditional bazars, so urban residents have opted to use other areas as substitute public spaces and buy goods. As a consequence of the prevailing situation, like unmaintained public spaces that leads to security issues and criminal activities, vehicular congestion and multistory structures in the city center on the land of traditional bazars, which have changed the urban fabric, and the emergence of new shopping trends, paved the way to the shopping mall concept. Shopping malls have not only displaced traditional bazaars as the preferred destination for shopping and social gatherings, but they have also met the need for public spaces in many cities around the world.

Shopping centers (also known as shopping malls or plazas) are the twentieth-century equivalent of traditional bazaars, resulting from modern construction. Shopping centers/malls are made up of collections of shopping outlets under one roof (Asadi, 2001). Additionally, these malls offer dining, parking, entertainment, and hair salons (Terblanche, 1999).

Furthermore, shopping malls have a comfortable and appealing setting (Underhill, 2005), and they resolve several problems with the shopping environment that are evident in traditional bazaars. For instance, they are built in a convenient location for everyone, including locals, tourists, pedestrians, and people who use other modes of transportation. Furthermore, they offer sufficient parking and a lovely and safe shopping area. Additionally, they provide spaces for social events and activities that turn them into livable public spaces.

Van Raaij (1993) supported the relevance of shopping center as vibrant public spaces by highlighting the main characteristics of shopping malls that resemble the public places. He identified various components that are supportive for shopping malls to become public places: Of those components, one of the most important is safety and security. Caymaz (2019) has provided a safety checklist by studying the five shopping malls of Istanbul, and this checklist can be used for designing any public space. On the other hand, Jalalkamali and Anjomshoa (2019) studied that the security and safety components are responded to differently by both genders, males and females. According to a case study of Grand Bazaar Kerman, Iran, as a public space, there is generally a noticeable difference in how male and female users of public spaces perceive the environment. According to the study, women’s fear of crime has a major impact on how they move around in public spaces. As a result, they avoid and restrict their movements in public spaces during particular hours of the day (Jalalkamali and Anjomshoa 2019). Gender-based activities and spaces are defined at a certain level in many shopping malls to make females feel comfortable and secure, but this does not apply to traditional bazaars. Therefore, a large number of women preferred shopping malls instead of traditional bazars. City planners put a lot of emphasis on public places in cities. However, due to urbanization, land-use patterns in urban settings have changed, and the left-over public spaces are now traditional bazars. Traditional bazars that were once served as public spaces are now replaced by shopping malls due to various factors that satisfy and attract customers. Therefore, user’s preferences are important to understand. Why would users in Karachi choose to be at shopping centers over the city’s traditional street bazaars are not studied in detail and need to be studied and focused on in this research. Following the evidence from previous research, the following hypotheses are tested in this study:

• Users’ individual characteristics influence their preference to go to the shopping center or traditional bazaar. For instance, those who can spend more money are more likely to go to shopping centers than traditional bazaars.

• Atmosphere of the shopping center is a preferable factor to visit and spend time in a shopping facility.

• Users’ perceived safety at a shopping facility is affected by their environmental attributes. For instance, visitors avoid traditional street bazaars due to levels of fear and an unmaintained environment.

• Visitors spend more time in shopping centers than in traditional bazaars due to leisure activities.

• Proximity to a shopping facility from users’ residence influences visitors’ decision to visit that facility.

3 Framing the case study area

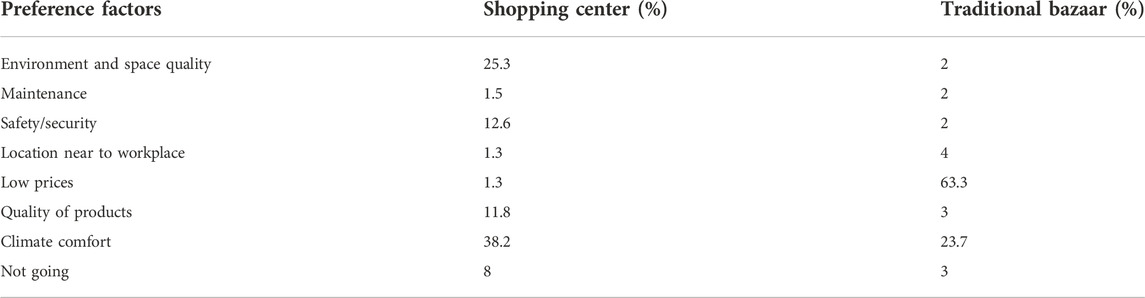

With a total area of 3,527 km2, Karachi is Sindh’s provincial capital and the largest city in Pakistan. It is located on the Arabian Sea shore and serves as the country’s central economic and industrial hub and its largest seaport (Figure 1). The fact that Karachi, the largest city in Pakistan, is one of the worst-ranked cities in the 2019 Global Livability Index (Gapihan and Malkawi 2021). This is because of a population density of more than 20,000 people per square kilometer. Gapihan and Malkawi (2021) also noted that Karachi’s green open space has decreased to less than 4 per cent and commercial development is threatening to swallow up the city’s few shared urban public spaces. Therefore, public spaces are even more necessary in this densely populated city.

FIGURE 1. Map of Karachi showing location of case study shopping center and open street bazaar (Source: Nomi887—CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia commons).

Karachi is commonly recognized on a global scale due to its strategic location and trade. One of the industries in Karachi’s local marketplaces has grown since the partition (1947). At the time of partition, the city was clearly separated into European and local cities. The Saddar bazaar, civil lines, and the cantonment made up the European city. Posh retail markets, shops, and restaurants could be found there; it was primarily populated by people from Europe and other places. The local city, which included a historic British town and surrounding suburbs, was located near the harbor. The working classes and merchants from Muslim and Hindu communities ruled it.

“Meethadar” was an entry point to trade goods and services for caravans traveling from Baluchistan and interior Sindh. Lea Market was built in 1927 in a location designated as a trading hub during the late 19th century, between 1900 and 1920. Measham Lea served as the inspiration for the name. In front of Lea Marketplace, a small space was designated for shops and go-downs. The British established Saddar Bazaar in 1939, right after taking control of Karachi. It was initially constructed to compete with the marketplaces in the old city. The city’s culturally distinctive center and monument, Saddar Bazaar, has grown throughout time. Jodia bazaar was established shortly after 1947 and has been essential to economic growth. The Urdu Bazaar in Saddar Town, which dates back to the Mughal Empire and is one of the oldest book markets on the entire subcontinent, was established in the 1950s. Following that, both small-scale and large-scale market expansion expanded.

The older Pakistani bazaars, particularly in Karachi, the country’s economic center and most significant metropolis, are no longer the preferred destination for shoppers in the late 1980s and early 1990s after the emergence of shopping malls. People from different neighborhoods in the city quit shopping at the traditional open-air bazaars in Karachi because of the heavy traffic on the small streets and preferred to shop in nearby malls. As the inner city grew more crowded, citizens relocated to the suburbs, and shoppers now chose to visit the less crowded area for their purchases. This has caused the historic architecture of the bazaars to be destroyed for other purposes and forced traditional traders to find different work opportunities. As a result, most of Karachi’s bazaars have witnessed significant changes in trade, business, and lifestyle. Shopping malls and other retail spaces are now considered to be among the primary urban public spaces because they are one of the most important aspects of a modern lifestyle. These shopping malls can generate a suitable atmosphere for interpersonal interactions and serve as significant urban centers. Therefore, these characteristics can be observed in our contemporary shopping malls. The new bazaar looks completely different from traditional bazaars, which include merchandise displayed in glass-enclosed stores with stiff-lipped salespeople. However, many cities, including Dubai, are developing new retail malls while emphasizing the often-overlooked issues of energy consumption and tradition preservation. In Karachi, the history of the marketplace that later paved the way to shopping centers dates back to 1889 with the inauguration of Empress Market. It was designed as a market for the British administrators and soldiers, people from Goa and Parsis who lived in Saddar. After Partition of sub-continent, the market, along with Saddar, had to accommodate a larger population, different classes, and ethnicities. With the passage of time, different bazars and markets had developed for instance Zaibunnisa Street, Zainab market, Jodia Bazaar, Gol Market etc. However, in the late 20th century, a shift from traditional markets to shopping malls was observed, and Karachi’s first shopping mall was built in 1999, named Park Towers. It was the nation’s first high-end shopping centre with distinct architectural characteristics and fulfilled the needs of that generation. Customers prefer to visit this place to not only buy but also because of the leisure activities available for kids. By shopping in this mall, parents could enjoy shopping while their children play with their friends in the play area. With the changing lifestyle and growing population, many shopping centers have now been built in the city for instance, Lucky one, Emerald Tower. Dolmen mall and Atrium mall etc.

3.1 Case study 1: Jodia Bazaar

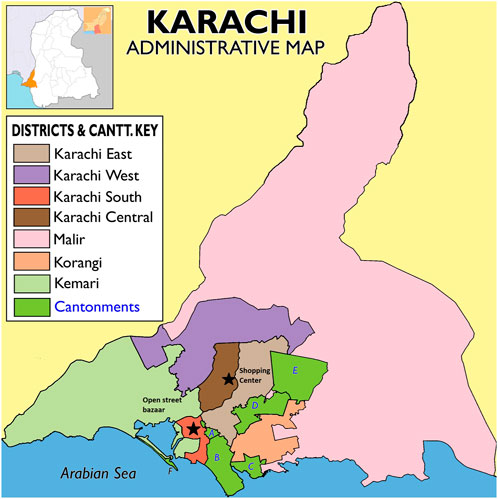

One of the city’s most well-known and prominent markets, Jodia Bazaar is regarded as the center of Pakistani trade. Since Pakistan’s independence, this market has served as a wholesaler and retailer, significantly contributing to the country’s economic growth since the partition. Jodia Bazaar is located in Karachi South district on M.A. Jinnah Road, next to Boulton Market. The most significant religious, commercial, and administrative activities of the city are located in the surrounding areas. Access to the bazaar have easy pedestrians’ accesses and is surrounded by other activities along with important landmarks and nodes. The bazaar is connected to the main road with its covered and semi-covered streets. However, the majority of the access routes are congested with cars and people walking around. Jodia Bazaar is one of the biggest markets that sells a wide variety of items at meager costs, including metals, paper, garments for the home, plastics, spices, hardware, shoes, dry fruits, and fresh fruits. This bazaar is divided into sections based on the trading activity, with similar functions clustering (Figure 2A). Primary wholesale market with manufacturing, supplying, storage, and packing functions. Being a mixed-use neighborhood, it consists of residential floors on the first floor with commercial activity on the ground floor. The traders like to live close to their places of employment and have converted the upper levels into a storage or production facility. Shop owners and dealers use Donkey carts to load and unload their merchandise. The spatial arrangement of Jodia Bazaar serves more than just commercial interests. In addition to being a site for business and trade Jodia bazaar also offers a variety of services, including mosques, schools, parks, playgrounds and entertainment facilities. Furthermore, it also has heritage buildings that attract several tourists and researchers. Being outdoor, alleys and stores are covered with fabrics that act as canopies, while small pathways restrict sunlight penetration (Figure 2B). Jodia Bazaar also serves as a olgathering spot for different ethnic groups to congregate and engage in socioeconomic activities. The vibrant sense of community further enhances the social aspect. Unfortunately, besides the positive aspects, this bazaar is now threatened by muggers and mobile snatchers, forcing families to shift from this place to other neighborhoods of the city (See Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2. (A) Bazaar is divided into various sections based on the trading activity (Source: Authors, 2022). (B) Street of Jodia Bazaar with covered walkways (Source: Authors, 2022). (C) Be aware poster installed from the trader’s association on one of the streets (Source: Authors, 2022).

3.2 Case study 2-Lucky One Mall

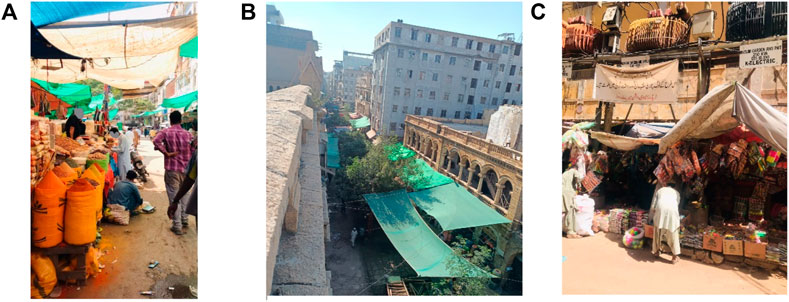

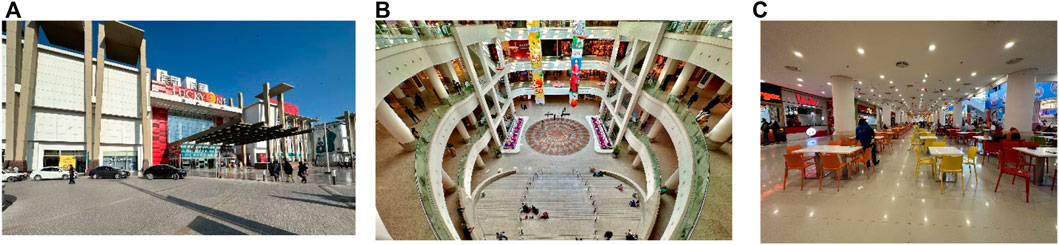

This paper selected Lucky One shopping mall as a case study, the largest mall in Pakistan and the second largest in south Asia. This shopping center is situated in the center of Karachi on Main Rashid Minhas Road in Gulshan-E-Iqbal. Its location in the city facilitates the people with the public buses with large numbers of commuters throughout the day, thus creating a unique, stimulating experience for the users. The city’s architectural styles influenced the structure of this mall, creating a modern rendition of the traditional bazaar (Figure 3A) that sells almost everything, from high-end items to food and handicrafts. The structure is constructed around an atrium with a skylight that serves as a courtyard with open steps providing a place to sit and congregate (Figure 3B). With an area of about 3.4 million square feet, Lucky One mall consists of over 200 stores and different services with large 2 floors, indoor parking space for 1,500 cars and in total 3,000 car parking spaces. This shopping center also comprises outlets for all Pakistani and some international brands. In addition, Lucky One mall also has entertainment areas like theatres, food courts, and gaming (Figure 3C). Furthermore, this shopping center offers a nursing room, separate male and female mosques, wheelchair access, and a safe and secure environment to facilitate customers further.

FIGURE 3. (A) A view of Lucky One Mall (Source: Authors, 2022). (B) Atrium of the mall with open steps (Source: Authors, 2022). (C) Entertainment area (Source: Authors, 2022).

4 Methodology

This study uses a comparative case study method to investigate people’s preference for shopping malls vs. Bazaars and the impact of services offered on user satisfaction. Data is gathered through a structured questionnaire survey of users who frequently visited shopping malls and traditional bazaars. A recently built shopping center (Lucky One Mall) and a case study of Karachi’s traditional and oldest bazaar (Jodia Bazaar) are used to investigate and analyze the qualities of the mall and bazaar. First, through field notes and photographs, systematic observation of selected shopping malls and traditional bazaars was conducted on two weekdays in September 2022 (10 am-7 pm). Later, the survey was administered online via a Google survey form. An online link was distributed to social media platforms in Karachi. A total of 76 surveys were thus obtained. The survey contained 30 closed-ended questions and one open-ended question. The questionnaire for this study was categorized into three main sections. The first section explained the demographics, and the second section included questions about shopping centers and traditional bazaars and users’ behavioral information in relation to shopping centers and traditional bazaars, for instance, the frequency of their visits. Section 3 and Section 4 subsequently comprises specific questions regarding shopping mall (Lucky One Mall) and traditional bazaar (Jodia Bazaar). The questions required to measure perceptions around four indicators: 1) atmosphere by asking questions about the quality of space and the levels of maintenance, 2) the concern about safety and security, 3) accessibility (convenience in terms of location), and 4) leisure activities. The survey took 10–15 min to complete. A short project introduction was provided on the first page of the questionnaire. The anonymity of the survey participants and voluntary participation was also explained.

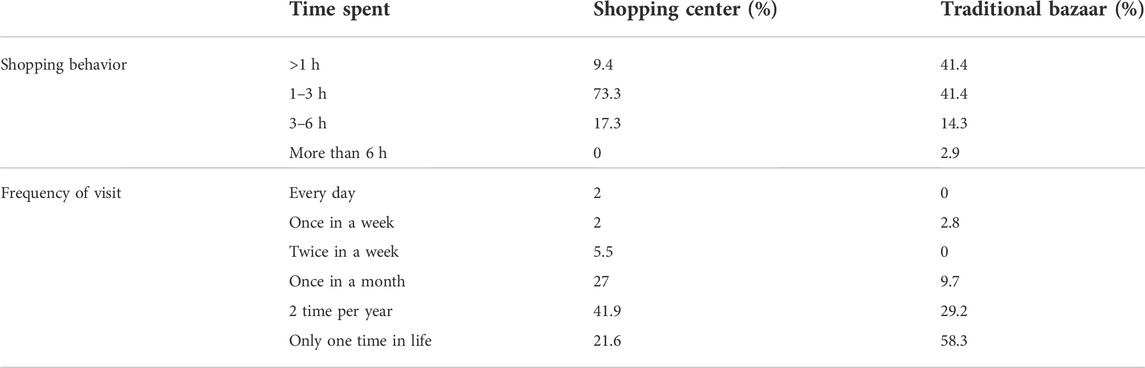

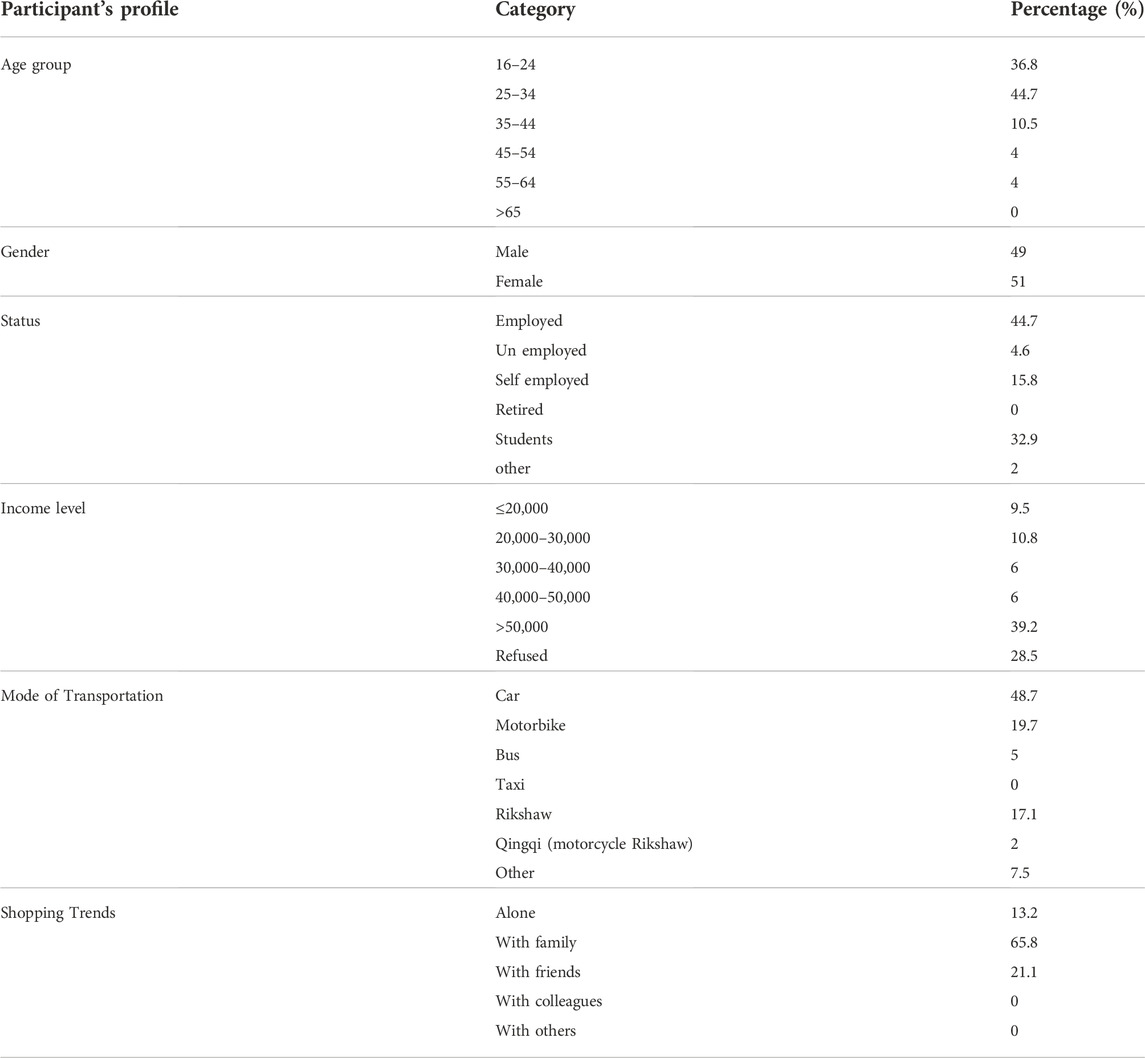

All answers collected through Google Forms were compiled automatically. The results of the questions were illustrated, among other things, through bar and pie charts. The basic demographic profile of the participants is available in Table 1. However, all questions were checked manually to ascertain the partial absence. The open-ended questions were coded using a coding template. The coding process was started by assigning a code to each response (Saldaña, 2009). Later, to analyze participants’ demographic characteristics, the collected data were analyzed. A Chi-square test using a statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) was employed to understand the relationship between time spent in a mall vs. traditional bazaar (Table 2) and shopping preferences for different attributes for using shopping centers or traditional bazaar (Table 3). The analysis was gathered around four indicators in relation to the use of shopping centers and traditional bazaars.

TABLE 1. Descriptive analysis for users’ profile and perceptions about shopping center vs. traditional bazaar.

5 Results and discussion

The result showed that overall, more female respondents answered the survey (51per cent) than male respondents, who made up 49 per cent of the sample. According to the respondents’ ages, most participants (44.7 per cent) are generally between the ages of 25 and 34, with a minority being above 35 (age group 35–44, 10 per cent; age group 45–54, 4.25 per cent). This demonstrates that the sample represented all age categories, with younger Pakistanis making up 44.7 per cent of the target population in which nearly 33per cent are students. With an average household income of just under Rs. 20,000 per month, there are more residents over all (39.2 per cent) with monthly incomes over Rs. 50,000. This shows that most survey participants had enough money to spend in shopping facilities and on other fun activities, corroborating Hypothesis 1. In addition, 49 per cent of respondents use personal vehicles for commuting, and less than 5 per cent of our sample respondents indicated a lower reliance on public transportation. There are indicators that the majority of people (65.8 per cent) like to go shopping with their families, while only 21 per cent prefer shopping with friends and 13.2 per cent shop alone. This suggests that people’s choice to go shopping with their families is a significant trend in society and shopping is not just an activity but also a means for families to have fun. These results corroborate the findings highlighted by Talpade and Haynes (1997) that shoppers who visit as a family look more for entertainment than shopping.

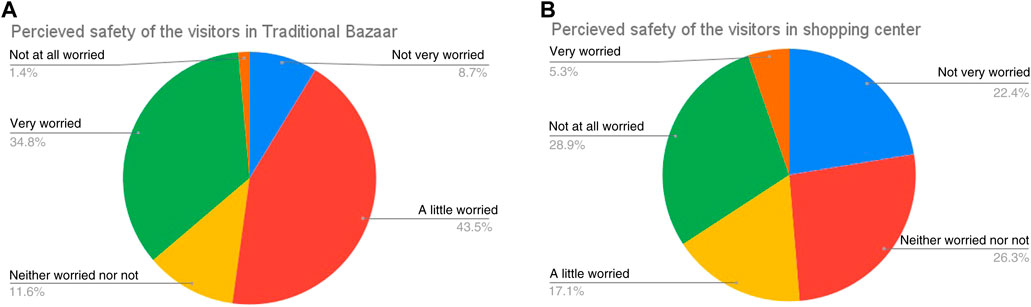

The results from the chi-square test showed that people’s preference to visit and spend time in the shopping mall or traditional bazaar is closely associated with the space quality and the maintenance of both places (χ2 = 49.849, df = 1, p < 0.05). Thus, the null hypothesis “Space quality and maintenance are not a preferable factor to visit and spend time in the shopping center over street bazaar” was rejected based on the Chi-square test. That seems in line with the findings from Rajagopal (2010) in Mexico City, which shows the existence of shopping centers and open street markets for different reasons. This means it is not necessary that users should visit only one of these facilities (shopping center or bazaar) and avoid the other as both of these shopping facilities have individual characteristics to attract users. Moreover, as expected in Hypothesis 3, there is a significant relationship between the concern about safety and security and the preference for visiting a shopping center or traditional bazaar (χ2 = 76.659, df = 1, p < 0.05). These results corroborate the previous research by Ceccato and Tcacencu (2018) that if visitors perceive the shopping center as unsafe, they may avoid going there. Findings from this study also suggest that the design of a shopping facility and its maintenance can affect shoppers’ perceived safety—for instance, poorly lit narrow walkways, hidden places, and unmaintained filthy environments. Regarding personal safety 34.8 per cent declared feeling very worried about crimes in Jodia Bazaar while 17.1 per cent reported a little worried in the shopping center as well (Figures 4A,B). When it comes to evening hours 71.1 per cent of our survey participants declared feeling safe in the shopping center, while only 13.2 per cent feel safe in the traditional bazaar. This has been highlighted by Jalalkamali and Anjomshoa (2019) by focusing on gender-based activities. It is important to note that females feel more comfortable and secure in shopping malls because the spaces are defined at a certain level; however, this is not the same for traditional bazaars. Therefore, a large number of women preferred shopping malls instead of traditional bazaars. There can be several reasons to feel insecure in the traditional street bazaar such as narrow streets, low lighting levels and an unmaintained environment (see Figure 2A). These results align with the results presented by Iqbal and Midhat (2022) that nearly half of the respondents declared high levels of fear of crime when out at night in a commercial street in Saddar district in Karachi (For details, see Iqbal and Midhat 2022).

FIGURE 4. (A) Perceived safety of the visitors in Traditional Bazaar (N = 76). Source: Authors, 2022. (B) Perceived safety of the visitors in shopping center (N = 76). Source: Authors, 2022.

Ibrahim and Ng (2001) highlighted that shopping centers had been portrayed with an image of entertainment and excitement in recent years. Our results show a direct relationship to leisure and social activities when looking at the preferences of our participants, corroborating Hypothesis 4. People spend more time in the shopping center than in traditional bazaar (χ2 = 58.1925, df = 1, p < 0.05). In terms of accessibility (χ2 = 35.0822, df = 1, p < 0.05) indicated a link between comfort and preference of shopping centers over the traditional street bazaar. These results align with the results Rajagopal (2010) presented that a combination of comfort and accessibility with general entertainment inspires shoppers to visit such places frequently. Furthermore, according to the survey’s findings, more than half of respondents (57.3 per cent) say they hang around more in a shopping center than in a traditional bazaar on streets (42.7 per cent). The transition between modern and traditional spaces significantly impacts urban public spaces. These findings corroborate the results highlighted by many other researchers that ambiance and architecture in relation to excitement encourage customers to spend more time and often visit the shopping center (Craig and Turley 2004; Rajagopal, 2010). Shopping centers provide a climate-controlled enclosure where individuals can more easily engage in leisure and social activities (Frasquet et al., 2001) compared to outdoor public places (Erkip and Ozuduru 2015). As a result, drawing more and more people to the new culture of the shopping centers.

Moreover, as expected in Hypothesis 5, this study reveals that 57.9 per cent of participants think that the proximity of the shopping center to their lodging place influences their decision to shop there. The remaining respondents said that their decision is influenced by their availability of time, their preferences for the type of content and brands, and the shopping center’s accessibility via public transportation, among other factors. On the other hand, when asked about their choice of a street bazaar like Jodia Bazaar in the city, 40 per cent of respondents said that they placed more importance on the accessibility to public transportation than the proximity to a shopping center. These results are in line with the results notified by Brunner and Mason (1968) and Rajagopal (2010) that there is a noteworthy effect of travel time on people’s behavior when visiting shopping centers. Furthermore, more than 30 per cent of participants say they avoided the traditional open street bazaars because of the narrow pathways, crowded streets, unmaintained environment, no parking and toilet facilities and presence of a large number of people (both buyers and non-buyers). Interestingly, the hustle and bustle of large crowds was once the most common and distinctive feature of a traditional bazaar (Raeesolmohadesin and Alipoor 2012). However, the historic bazaars are deteriorating and dying due to economic growth, safety and security concerns, and a fast-paced modern lifestyle (Mehdipour and Rashidi 2013). Another critical factor in the decline of the traditional bazaar is the maintenance of these places. Some of the roads in Jodia Bazaar are incredibly narrow and not easily accessible to fire brigades, making many fire incidents routine here (News 360, 19 November 2021).

Consequently, our respondents consider shopping center in Karachi to be more trustable public spaces than traditional street bazaars. Various factors have influenced the transition of consumers from the traditional marketplace to shopping malls in Pakistan, such as crowded environment, scorching weather and humidity, economic development, cultural diversity, and lifestyle changes (Ghosh and McLafferty 1987; Garreau, 1992; Banerjee, 2001; Erkip, 2003; Anselmsson, 2006). Considering Karachi, Pakistan, parents encourage their kids to stay in these observant places in an enclosed environment. Women feel more protected to visit such places away from the hustle and bustle of open street bazaars (Salcedo, 2003). For those who belong to Karachi’s “middle class,” these shopping centers serve as an urban “third place” to unwind between work and home and a buffer between professional and private life. In the Pakistani scenario, these new shopping arenas seem to create more citizens’ tolerance for one another when comparing different genders, age groups, social classes, and religious and secular groups in public places (Erkip, 2003). Shopping centers are increasingly viewed as sanitized replicas of urban street bazaars that nonetheless have all the richness of urban life. However, we cannot ignore that this new type of privately owned public space often excludes specific groups of people (Loukaitou-Sideris, 1993) such as the poor and homeless.

Respondents of this study have been invited to recommend improvements to the city’s current shopping malls and street bazaars by an open-end question in the survey. The findings indicate that the facilities provided in the shopping centers satisfy the participants. However, more than half of the participants recommended providing sufficient sidewalks alongside the shops in traditional open street bazaars and shopping centers. These findings also align with the results of Ceccato and Tcacencu (2018): 236. Additionally, it was found that the participants were more concerned with the problems with traditional street bazaars, with 30 per cent of them wanting enough parking and 17.6 per cent of participants advising adding restrooms in street bazaars. Moreover 13.2 per cent asked to add streetlights in traditional bazaars. These ideas can be included in future designs for shopping malls and street bazaars, in addition to helping to improve existing ones.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

Shopping facilities as public spaces are expected to play a vital role in improving the quality of life and the comfort of its users by offering activities that help them to feel better and enjoy themselves. Although shopping centers and open street bazaars both provide shopping activities, users’ satisfaction levels may differ in both facilities. According to this study survey results, users prefer to visit shopping centers in Karachi because of their unique qualities. For example, the location of shopping center, services and facilities they offered, entertainment and socializing opportunities, and feeling of safety and security. A shopping center’s facilities and services included control over the internal environment, free from heat and rain, and parking facilities. Our findings disclose that shopping center’s proximity to their lodging place influences most of the respondents’ decision to shop there. The remaining respondents’ decision is influenced by their availability of time, their preferences for the type of content and brands, and the shopping centers’ accessibility via public transportation, among other factors. On the other hand, regarding the choice of a traditional open street bazaar in Karachi city, respondents placed more importance on the affordable price and accessibility to public transportation than the proximity to a shopping center. The results showed that the shoppers’ behaviors towards open street bazaar needed to be more satisfactory. Narrow pathways, crowded streets, bad lighting, unmaintained filthy environment, no parking and toilet facilities, a large influx of people and safety and security issues were highlighted as some of the primary reasons by our respondents to avoid the traditional open street bazaars in Karachi. Therefore, the study suggests that traditional bazaars should be improved by adding adequate street lighting, parking places, and completely equipped and hygienic restrooms. Due to the harsh weather and heat, walkways should also be well covered. It is also essential to improve the surrounding landscape to maintain the microclimate (creepers, shady trees). Walkways should be added to the streets. Spaces for displaying goods ought to be restricted to prevent congestion. Bazaars require an addition of socially connected open areas. For instance, sequences of related functions tend to group together. Using the value, cost, and appeal of the commodities as criteria, may help to create better zoning. Improving formal and informal surveillance, creating soft and hard target hardening measures at different locations in the bazaar may also ensure the safety and security of its users. It is also very important to consider the improvement of overall structures while retaining the historical and local identities of the cities.

It is important to note that the results of this study have been conducted within a short period of time. Therefore, it was limited to four attributes identified from the literature review (see introduction). Secondly, only one shopping mall and one traditional open street bazaar was used as the case study; therefore, this study has a limited generalizability (small sample size in terms of both the number of respondents and case studies) This study could serve as the basis for future research on shopping centers and open street bazaars in other cities in Pakistan and in other South Asian countries. The study could be expanded by increasing the number of indicators and adding more case study shopping centers and traditional open street bazaars. Furthermore, concerning the research methodology, conclusions may be affected by the presence of confounding variables. In future, research control variables should use to attain internal validity. Additionally, other methods will be used to validate the survey outcomes. Future research will focus on comparing the degree of user’s satisfaction in terms of pricing advantages and other factors.

Moreover, it is essential to understand that shopping is becoming a fundamental element of contemporary lifestyle. What influences where individuals go shopping in Karachi? Why would individuals shop at a particular shopping center over the city’s specific open street bazaar? Developers, planners, and public institutes in Karachi can benefit from answers to these questions. This study has contributed to highlighting user’s preferences and perceptions of a selected shopping center and an open street bazaar in Karachi city that reinforces the conceptual and theoretical significance of the research. This study also emphasized planning and management issues of traditional open street bazaars in Karachi by considering users’ needs and strengthening participatory planning and development strategies among all public spaces’ stakeholders. By identifying the most salient attributes that attract people to shopping malls in Pakistan, the study acts as a wake-up call for planners and developers to incorporate these attributes in the development of new shopping malls and the improvement of existing traditional street bazaars.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, AI and HN; project administration, AI and HN; methodology, AI and HN; data collection, HN; formal analysis, AI, HN, and RM; writing—original draft preparation, AI and HN; writing, review and editing, AI and HN; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful to Muhammad Ali Ansari and Ayesha Shakeel Khan for their support in capturing the photographs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with the authors HN, RM.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amin, A. (2002). Ethnicity and the multicultural city: Living with diversity. Environ. Plan. A 34 (6), 959–980. doi:10.1068/a3537

Anselmsson, J. (2006). Sources of customer satisfaction with shopping malls: A comparative study of different customer segments. Int. Rev. Retail Distribution Consumer Res. 16 (1), 115–138. doi:10.1080/09593960500453641

Al, S. (2016). Mall city: Hong Kong's dreamworlds of consumption. Editor A. I. Stefan (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press).

Banerjee, T. (2001). The future of public space: Beyond invented streets and reinvented places. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 67 (1), 9–24. doi:10.1080/01944360108976352

Bazaar market Britannica (2020). Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/bazaar.

Brunner, J. A., and Mason, J. L. (1968). The influence of driving time upon shopping center preference. J. Mark. 32 (2), 57–61. doi:10.1177/002224296803200209

Caymaz, G. F. Y. (2019). The effects of built environment landscaping on site security: Reviews on selected shopping centers in i?stanbul. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 3 (1), 191–201. doi:10.25034/IJCUA.2018.4730

Ceccato, V., and Tcacencu, S. (2018). “Perceived safety in a shopping centre: A Swedish case study,” in Retail crime (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 215–242. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73065-3_9

Chismon, M. The 21st century - a ‘game changer' era for world mission. Available at: https://simplymobilizing.com/the-21st-century-a-game-changer-era-for-world-mission/. (Accessed August 17, 2022).

Craig, A. M., and Turley, L. W. (2004). Malls and consumption motivation: An exploratory examination of older generation Y consumers. Int. J. Retail Distribution Manag. 32 (10), 464–475. doi:10.1108/09590550410558608

Difference between bazaar and flea market, (2013). Available at: http://www.differencebetween.info/difference-between-bazaar-and-flea-market (Accessed August 17, 2022).

Duyvendak, J. W., and Wekker, F. (2015). “Thuis in de openbareruimte? Over vreemden, vriendenen het belang van amicaliteit,” in De stad kennen, de stad maken. Netherlands: Platform31, Available at: www.platform31.nl/uploads/media_item/media_item/37/45/Essay_Thuis_in_de_openbare_ruimte-1424180382.pdf.

Erkip, F., and Ozuduru, B. H. (2015). Retail development in Turkey: An account after two decades of shopping malls in the urban scene. Prog. Plan. 102, 1–33. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2014.07.001

Erkip, F. (2003). The shopping mall as an emergent public space in Turkey. Environ. Plan. A 35 (6), 1073–1093. doi:10.1068/a35167

Frasquet, M., Molla, A., and Gil, I. (2001). Shopping-centre selection modelling: A segmentation approach. Int. Rev. Retail, Distribution Consumer Res. 11 (1), 23–38. doi:10.1080/09593960122279

Gapihan, A., and Malkawi, F. (2021). Transforming Karachi into a more livable city begins with public spaces. Washington, DC., USA: World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/transforming-karachi-more-livable-city-begins-public-spaces.

Garreau, J. (1992). Edge city: Life on the new frontier. New York: Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc.

Ghosh, A., and McLafferty, S. L. (1987). Location strategies for retail firms and service firms. Lexington: DC: Heath Company.

Goss, J. (1993). The “magic of the mall”: An analysis of form, function, and meaning in the contemporary retail-built environment. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 83 (1), 18–47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1993.tb01921.x

Ibrahim, M. F., and Ng, C. W. (2001). Determinants of entertaining shopping experiences and their link to consumer behavior: Case studies of shopping centers in Singapore. J. Leis. Prop. 2 (4), 338–357. doi:10.1057/PALGRAVE.RLP.5090155

Iqbal, A. (2021). “Inclusive, safe and resilient public spaces: Gateway to sustainable cities?,” in Urban transition - perspectives on urban systems and environments [working title]. Editors P. M. Wallhagen, and M. Cehlin (London, UK: IntechOpen). doi:10.5772/intechopen.97353

Iqbal, A., and Midhat, M. (2022). Morphological characteristics and fear of crime: A case of public spaces in the global north and south. built Environ. 48 (2), 206–221. doi:10.2148/benv.48.2.206

Jalalkamali, A., and Anjomshoa, E. (2019). Evaluating gender based behavior in historical urban public place case study: Grand Bazaar, Kerman, Iran. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 3 (1), 143–153. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2018.4691

Lee, D. (2022). Whose space is privately owned public space? Exclusion, underuse and the lack of knowledge and awareness. Urban Res. Pract. 15 (3), 366–380. doi:10.1080/17535069.2020.1815828

Lofland, L. H. (1989). Social life in the public realm: A review. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 17 (4), 453–482. doi:10.1177/089124189017004004

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (1993). Privatisation of public open space: The los angeles experience. Town Plan. Rev. 64 (2), 139–167. doi:10.3828/tpr.64.2.6h26535771454436

Mehdipour, A., and Rashidi, H. (2013). Persian Bazaar and its impact on evolution of historic urban cores-The case of Isfahan. Macrotheme Rev. 2 (5), 12–17.

Minton, A. (2022). Coda: Reflections on public and private space in a post-covid world. Urban Geogr. 43 (1), 1–7. doi:10.1080/02723638.2022.2053428

Mitchell, D. (2003). The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. New York, NY, USA: Guilford press.

News 360 (2021). Another terrible incident in Jodia bazaar. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8iThvGyzjI (Accessed October 01, 2022).

Newworldencyclopedia.org (2019). Bazaar - New World Encyclopedia, Available at: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Bazaar (Accessed August 17, 2022).

Pirnia, M. K., and Memarian, G. H. (2005). Introduction to islamic architecture of Iran. Tehran: Soroosh Danesh.

Raeesolmohadesin, S., and Alipoor, B. (2012). Investigating sustainability factors according to the image of Iranian bazaar. Int. J. Archit. Urban Dev. 2 (6), 25–30.

Rajabi, A., and Sefahan, A. (2009). Iranian markets, embodies the ideas of sustainable development. Geography 11, 113–127. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.11.001

Rajagopal, P. (2010). Coexistence and conflicts between shopping malls and street markets in growing cities: Analysis of shoppers’ behaviour. J. Retail Leis. Prop. 9, 277–301. doi:10.1057/rlp.2010.17

Rouz, R. K. (2014). From bazaars to shopping centers. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5 (23), 1875. doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n23p1875 Available at: https://www.richtmann.org/journal/index.php/mjss/article/view/4731.

Salcedo, R. (2003). When the global meets the local at the mall. Am. Behav. Sci. 46 (8), 1084–1103. doi:10.1177/0002764202250500

Talpade, S., and Haynes, J. (1997). Consumer shopping behavior in malls with large scale entertainment centers. Mid-Atlantic J. Bus. 33 (2), 153.

Terblanche, N. (1999). The perceived benefits derived from visits to a super regional shopping centre: An exploratory study. South Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 30 (4), 141–146. doi:10.4102/sajbm.v30i4.764 Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-686271243.

Underhill, P. (2005). Call of the mall: The geography of shopping by the author of why we buy. New York, United States: Simon & Schuster.

Van Eijk, G., and Engbersen, R. (2011). Facilitating 'light'social interactions in public space: A collaborative study in a Dutch urban renewal neighbourhood. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 5 (1), 35–50.

Van Raaij, W. F. (1993). Postmodern consumption. J. Econ. Psychol. 14 (3), 541–563. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(93)90032-G

Velashani, S. T., Madani, I., Azeri, A. R. K., and Hosseini, S. B. (2015). Effect of physical factors on the sense of security of the people in Isfahan's traditional bazaar. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 201, 165–174. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.165

Weaver, T. (2014). “The privatization of public space: The new enclosures,” in APSA 2014 annual meeting paper (Rochester, NY, USA: SSRN). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2454138.

Keywords: users’ satisfection, atmosphere, Safety, accessibility, leisure activities

Citation: Iqbal A, Nazir H and Memon RM (2022) Shopping centers versus traditional open street bazaars: A comparative study of user’s preference in the city of Karachi, Pakistan. Front. Built Environ. 8:1066093. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2022.1066093

Received: 10 October 2022; Accepted: 07 November 2022;

Published: 22 November 2022.

Edited by:

Waqas Ahmed Mahar, Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and Management Sciences, PakistanReviewed by:

Djamel Boussaa, Qatar University, QatarHourakhsh Ahmad Nia, Alanya Hamdullah Emin Pasa University, Turkey

Copyright © 2022 Iqbal, Nazir and Memon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asifa Iqbal, YXNpZmEuaXFiYWxAaGlnLnNl

Asifa Iqbal

Asifa Iqbal Humaira Nazir2

Humaira Nazir2