94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 28 February 2025

Sec. Synthetic Biology

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2025.1547226

Marian M. Awaga-Cromwell1

Marian M. Awaga-Cromwell1 Santosh Kumar1

Santosh Kumar1 Hieu M. Truong1

Hieu M. Truong1 Eric Agyeman-Duah1

Eric Agyeman-Duah1 Christopher C. Okonkwo2

Christopher C. Okonkwo2 Victor C. Ujor1*

Victor C. Ujor1*Introduction: Although solventogenic Clostridium species (SCS) produce butanol, achieving high enough titers to warrant commercialization of biobutanol remains elusive. Thus, deepening our understanding of the intricate cellular wiring of SCS is crucial to unearthing new targets and strategies for engineering novel strains capable of producing and tolerating greater concentrations of butanol.

Methods: This study investigated the potential role of cyclic-di-adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP) in regulating solvent biosynthesis in C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Genes for c-di-AMP-producing and degrading enzymes [DNA integrity scanning protein A (disA) and phosphodiesterase (pde), respectively] were cloned in this organism and the recombinant strains were characterized relative to the control strain.

Results: Plasmid-borne expression of disA in C. beijerinckii led to a 1.83-fold increase in c-di-AMP levels and near complete (∼100%) inhibition of butanol and acetone biosynthesis. Conversely, c-di-AMP concentrations in the pde-expressing strain reduced 7.54-fold relative to the control with 4.20- and 2.3-fold reductions in butanol and acetone concentrations, respectively, when compared to the control strain. Relative to the control and the pde-expressing strains, the disA-expressing strain produced 1.50- and 1.90-fold more ethanol, respectively. Enzyme activity assays show that core solvent biosynthesis enzymes are mostly inhibited in vitro by exogenously supplemented c-di-AMP (50 nM). Both recombinant strains of C. beijerinckii are impaired for sporulation, particularly the disA-expressing strain.

Discussion: Collectively, the results show that dysregulated production and hydrolysis of c-di-AMP severely impair butanol and acetone biosynthesis in C. beijerinckii, suggesting broader roles of this second messenger in the regulation of solventogenesis and likely, sporulation in this organism.

Bio-butanol has enormous potential as a biofuel and as an industrial bulk chemical with broad applications (Agyeman-Duah et al., 2022; Qureshi and Ezeji, 2008). However, biosynthesis of butanol by solventogenic Clostridium species is tightly regulated, largely due to the chaotropic nature of butanol, which causes severe membrane damage with increasing concentration in the culture broth (Cray et al., 2015). Notably, butanol biosynthesis and sporulation are intricately “hardwired” in solventogenic clostridia (Long et al., 1984; Diallo et al., 2021). Consequently, the inception of butanol biosynthesis synchronizes with activation of the sporulation machinery, which acts as a cellular “shield” to protect cells against butanol toxicity by transitioning vegetative butanol-producing cells into inactive butanol-tolerant spores, with increasing butanol titer. Previously, we reported that ribonuclease P (RNase P)-mediated knockdown of the mRNA levels of the gene encoding cyclic-di-adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP)-producing DNA integrity scanning protein A (disA) in Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 (hereafter, Cbei) increased butanol production and delayed sporulation (Ujor et al., 2021). This suggests likely implication of c-di-AMP in coordinating the interplay between sporulation and solventogenesis, at least in Cbei. Notably, Spo0A, the master regulator of sporulation in solventogenic clostridia has been shown to also exert a strong positive effect on butanol biosynthesis (Long et al., 1984; Diallo et al., 2021). In light of the effect of disA knockdown on butanol production and sporulation, the role of Spo0A in solventogenesis and sporulation, and the established role of c-di-AMP in regulating sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al., 2011), it is plausible that c-di-AMP might directly or indirectly influence the interplay between sporulation and solventogenesis in SCS.

DisA is a diadenylate cyclase that produces the bacterial second messenger, c-di-AMP (Bejerano-Sagie et al., 2017; Teh et al., 2019). C-di-AMP exerts far-reaching effects on the overall biology of producer organisms; playing significant roles in sporulation, DNA repair, cell wall synthesis/cross linking, response to osmotic stress and maintenance of cell envelope integrity; virulence, regulation of gene expression, and control of cellular fitness (Bejerano-Sagie et al., 2017; Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al., 2011; Commichau et al., 2015; Rørvik et al., 2021). Among these roles of c-di-AMP, its involvement in sporulation and maintenance of cell envelope integrity might interface with the regulation of butanol biosynthesis and tolerance. Given the chaotropic nature of butanol, hence, its membrane damaging effect (Cray et al., 2015) and the ability of c-di-AMP to regulate response to osmotic stress/damage, it is possible that c-di-AMP might serve as a nimble cellular “switch” that links response to butanol biosynthesis, butanol toxicity, and sporulation in Cbei.

In this study, we sought to further investigate the exact roles that c-di-AMP might play in butanol production and tolerance, and sporulation in Cbei. Cloning and overexpressing the native disA and a c-di-AMP-specific (hydrolyzing) phosphodiesterase gene (pde; encoding a protein homologous to DHH/DHHA1 phosphodiesterase in B. subtilis) in Cbei showed that dysregulated biosynthesis and hydrolysis of c-di-AMP severely impairs or completely inhibits butanol production in this organism. In vitro, c-di-AMP exhibits dose dependent inhibition of the activities of some butanol and acetone biosynthesis enzymes. Herein, we present different lines of evidence that further link intracellular c-di-AMP levels to the regulation of solvent production and sporulation in Cbei.

Escherichia coli DH5α was procured from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, United States). Escherichia coli DH5α was propagated in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Cbei was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, United States) and maintained in the laboratory as a spore suspension in sterile distilled water, according to a previously reported protocol (Agyeman-Duah et al., 2022).

The primers used to clone Cbei_disA (::disA) and Cbei_pde (::pde) are presented in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Material). The genes disA (Cbei_0127) and pde (Cbei_5082) were amplified from the genomic DNA of Cbei extracted according to the method described by Agyeman-Duah et al. (2022). Two-step amplification was used for each gene wherein, the first sets of primers (Cbei_0127_Fv1 + Cbei_0127_Rv1 and Cbei_5082_Fv1 + Cbei_5082_Rv1; Supplementary Table S1) were used solely for gene amplification and the second sets (Cbei_0127_Fv2 + Cbei_0127_Rv2 and Cbei_5082_Fv2 + Cbei_5082_Rv2) were used to incorporate ApaI and XhoI restriction sites into the amplicons. Amplification was conducted with Phusion Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States) according to the following reaction conditions: 98°C for 2 min; 15 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 50°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 2 min followed by 21 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 63°C for 15 s and 72°C for 9 min and a final hold at 4°C. Both disA and pde were cloned into the Clostridium-E. coli shuttle vector pWUR459 (Siemerink et al., 2011) following digestion with ApaI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States). The plasmid constructs were chemically transformed into E. coli Dh5α (Agyeman-Duah et al., 2024) and colonies were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). Positive transformants were confirmed by colony PCR and sequencing of PCR amplicon and plasmid constructs using gene-specific and M13 forward and reverse primers (Eurofins Genomics, Louisville, KY, United States). Subsequently, the plasmid constructs were electro-transformed into Cbei following a previous protocol (Agyeman-Duah et al., 2024). The transformants were grown on tryptone-glucose-yeast extract (TGY) agar (0.5%, w/v). Positive colonies were selected, grown in TGY medium and then stored as glycerol stocks [30% glycerol (v/v)] at −80°C for future experiments. Additionally, the recombinant strains were grown to sporulation in P2 fermentation medium (100 mL) containing glucose (60 g/L), yeast extract (1 g/L), and 1 mL each of pre-filter-sterilized mineral, buffer and vitamin stocks in loosely capped 250-mL Pyrex culture bottles. The buffer stock comprised of (in g/L): K2HPO4 (50), KH2PO4 (50) and ammonium acetate (220). The mineral stock contained (in g/L): MgSO4.7H2O (20) MnSO4·H2O (1), FeSO4.7H2O (1), and NaCl (1), while the vitamin stock contained (in g/L): p-amino-benzoic acid (0.1), thiamine (0.1), and biotin (0.001). The spores were harvested after 2 weeks, washed five times in sterile distilled water and stored in sterile distilled water at 4°C.

Fermentation of glucose and arabinose by Cbei_p459 (empty plasmid control), Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde was conducted in P2 medium described above. Spores (200 μL) of Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were inoculated into 50 mL of TGY broth and grown overnight as precultures. Afterwards, the precultures (6% v/v) were transferred into P2 medium containing 60 g/L glucose or arabinose. Arabinose was used as substrate because we previously observed improved butanol production in Cbei following RNase P-mediated knockdown of disA (Ujor et al., 2021). The cultures were supplemented with 25 µg of erythromycin and samples were taken every 12 h and analyzed for acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE), acetic and butyric acids concentrations; optical density, and pH. Except where stated otherwise, all cultures were grown and analyzed in triplicate. All cultures were grown at 35°C ± 1°C in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products Inc., Grass Lake, MI, United States) with a modified atmosphere of 82% N2, 15% CO2, and 3% H2.

The concentrations of ABE, acetic and butyric acids were quantified using a Shimadzu GC-2010 Plus gas chromatography (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, United States) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a Shimadzu SH-PolarWax crossbond carbowax polyethylene glycol column [30 m (length), 0.25 mm (internal diameter), and 0.25 μm (film thickness)] according to a previous method (Agyeman-Duah et al., 2022). Culture pH was monitored using an Orion Star A214 pH meter (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and cell growth was measured as optical density (OD600 nm) with an Evolution 260 Bio UV/Visible spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States).

To isolate RNA, Cbei_disA Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were grown in P2 medium as described above. RNA was isolated from cell samples collected at 24 h and 36 h. RNA isolation was carried out using TRIzol™ Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) according to an earlier described method (Kumar et al., 2024). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized and used as a template for qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers as described by Kumar et al. (2024). The expression profiles of 20 genes were studied by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Table S1). Relative gene expression was quantified by normalizing the target genes to rpoD and 16SRNA housekeeping genes of Cbei using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Results are represented as the means ± standard deviation of three technical replicates.

Intracellular levels of c-di-AMP were quantified according to the method described by Huynh et al. (2015). Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were grown in P2 medium as described earlier (under fermentation). After 24 h, 2 mL samples were drawn and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min (Sorvall Legend Micro 21R, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The cell pellets were re-suspended in 50 µL of heavy isotope (C and N) labeled c-di-AMP and 500 µL of methanol. Cells were lysed on ice in the sonicator at 80% amplitude for 10 pulses (1 s on/1 s off for 20 s). After lysis, the mixture was centrifuged as described above and the supernatant was transferred into a new centrifuge tube. Subsequently, 500 µL of methanol was added to the pellet portion, vortexed, and centrifuged as described above. The resulting supernatant was added to the initial supernatant. The pooled supernatants were concentrated in an Eppendorf Vacufuge Plus 5305 (Eppendorf, Enfield, CT, United States) for 2 h with the operation and application mode set to vacuum alcohol. Afterwards, the pellets were rehydrated in 50 µL of sterile double distilled water. The extracted c-di-AMP was quantified by LC/MS (Sciex 5500 QTRAP triple quadrupole/ion trap mass spectrometer connected to an Agilent 1100 Nano flow HPLC system). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Synergi 4u Hydro-RP 80A column (50 × 2 mm, 4 μM particle size; Phenomenex) with a mobile phase consisting of 10 mM formic acid in water (Solvent A) and 10 mM formic acid in methanol (Solvent B) as previously described by Huynh et al. (2015). Intracellular amounts of c-di-AMP levels are represented as average values of three biological replicates in µg/g cell dry weight.

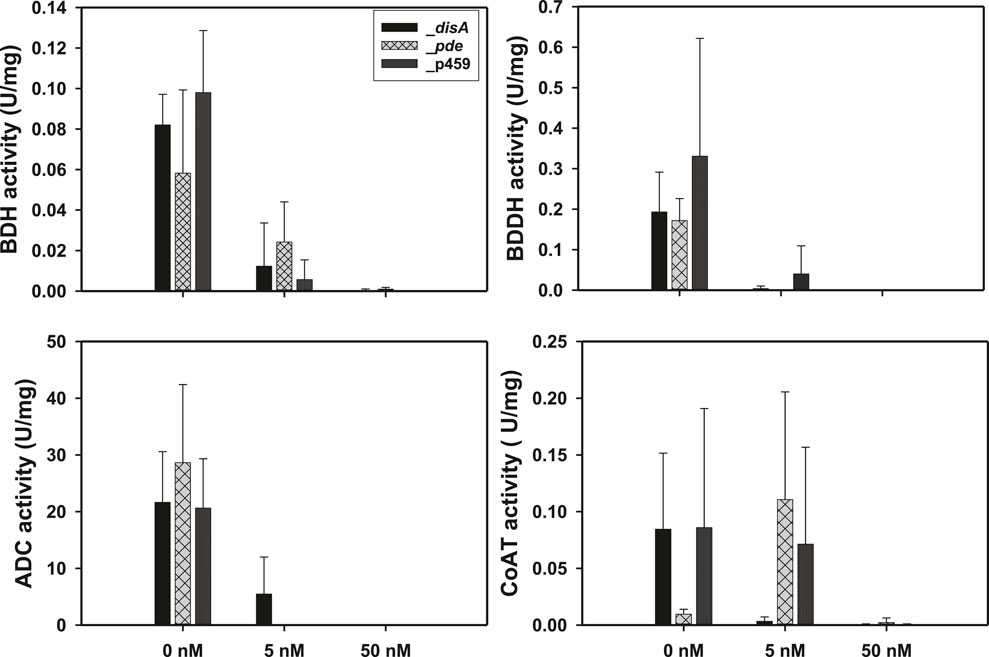

Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were grown on glucose (P2 medium) as earlier described and butanol dehydrogenase (BDH), butyraldehyde dehydrogenase (BDDH), acetoacetate decarboxylase (ADC) and coenzyme A transferase (CoAT) activity assays were performed on crude cell extracts according to the methods of Agyeman-Duah et al. (2022), with slight modifications. Cells were harvested after 24 h, washed, pelleted by centrifugation as described under c-di-AMP quantification, and then lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (10 mg/mL lysozyme, 10 mM phosphate buffer and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 1 h at 37 °C. BDH activity was quantified with butyraldehyde as substrate by measuring the decrease in absorbance (due to NADPH consumption) at 340 nm (0.1 mM NADPH was used). BDDH activity was measured with butyryl coenzyme A by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (due to NADH consumption). ADC activity was quantified by measuring the decrease in the absorbance of acetoacetate at 270 nm in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 5.9), 300 mM lithium acetoacetate, and 50 µL of the crude cell extract (Fridovich, 1972). To assess possible effect of c-di-AMP on enzyme activities, the assay reaction mixtures for BDH, BDDH, ADC, and CoAT were supplemented with 5 nM or 50 nM sodium salt of c-di-AMP (Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA, United States). Assay mixtures without the respective substrates, cell lysate, and c-di-AMP were used as the negative controls. The molar extinction coefficients used to calculate enzyme activities include 6220 M-1cm-1 for NADH and NADPH at 340 nm, 55 M-1cm-1 for acetoacetate at 270 nm, and 7800 M-1cm-1 for acetoacetyl-CoA at 310 nm. Protein concentrations of the lysates were measured and enzyme activities were expressed in units of activity per mg protein.

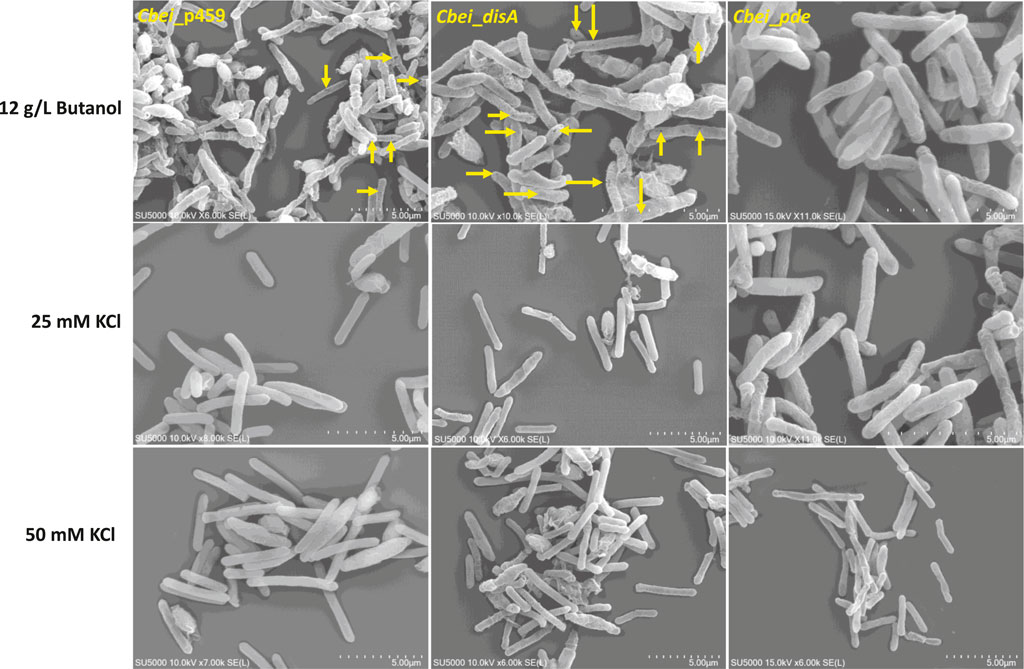

To assess the butanol tolerance of each strain, cultures were grown as described earlier (under fermentation). After 24 h, 12 g/L of butanol was added to each culture. Sterile distilled water was added to the control culture. Eight hours after butanol addition, triplicate samples were drawn and vegetative cell mass was measured as a function of optical density using Evolution 260 Bio UV/Visible spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Samples were taken from the top quarter part of the culture bottles to avoid taking up spores, which settle at the bottom of the culture. To determine if classic butanol-mediated membrane damage mimics KCl-induced osmotic shock, the cultures were challenged with 12 g/L butanol and 25 mM and 50 mM KCl. The cultures were challenged at 24 h. Four hours after the challenge, 10 mL samples were taken and processed for scanning electron microscope as described below.

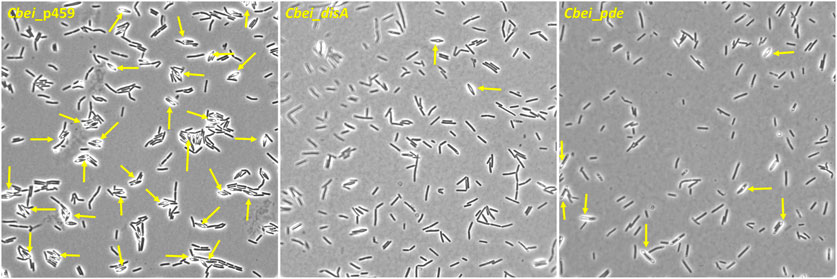

Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were grown in triplicate on glucose as described under fermentation and 1 mL samples were taken after 24 h for phase contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse Ti series microscope, Nikon, Melville, NY, United States). Phase contrast microscopy was carried out according to our previously reported method (Kumar et al., 2024). All samples were viewed and captured at ×100 magnification. The number of endospore-bearing cells relative to total vegetative cells were enumerated in triplicate to determine percentage spore formation for each strain of Cbei.

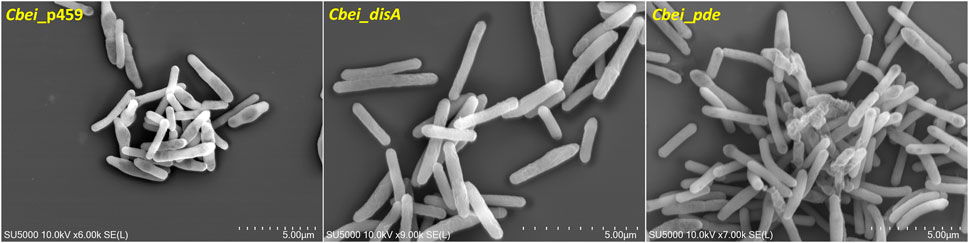

Cultures of Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 were grown as described above. After 24 h, 2 mL samples were taken and prepared for SEM according to the method described by Pilavtepe-Çelik et al. (2008) with slight modifications. Cell pellets were collected by centrifuging the samples at 600 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Cell pellets were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (pH = 7.4) and centrifuged as above. Subsequently, cells were washed in 1 mL of 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH = 7.4) and centrifuged twice as above. The cells were re-suspended in 1 mL of fixative (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate Buffer, pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature, and then stored overnight at 4 °C. The fixed samples were washed twice with 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer and centrifuged as above for 10 min. The fixed cells were then dehydrated in an ethanol series (25%, 50%, 70%, 95% and 100%) in a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. Each dehydration step lasted for 15 min, and ethanol was removed by centrifuging for 10 min at 2,500 rpm. The last dehydration step in 100% ethanol was performed three times with fresh ethanol. Afterwards, the samples were treated three times with 100% hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) for 15 min/cycle. After the third HMDS treatment, 5 μL of each sample was pipetted onto a silicon chip and air-dried for 30 min in a humid chamber. After drying, the silicon chips were secured onto SEM stubs using 25 mm double-sided carbon adhesive tabs. The prepared SEM stubs were placed into the sputter coater (Quorum, Model: Q150T S plus) and the chamber was evacuated to create a vacuum. Consequently, the samples were sputter coated with 3 mm of platinum while monitoring the coating process to ensure a uniform coating. The samples were carefully transferred into the SEM chamber (Hitachi, Model: SU5000) and the SEM parameters were optimized for imaging. The accelerating voltage was set to 5–15 kV and the working distance was set to 5–10 mm. Samples were imaged and the high-resolution version of the images was captured while adjusting the focus, magnification, and contrast as needed to obtain clear and detailed images.

To identify putative c-di-AMP-binding proteins in Cbei, the conserved c-di-AMP binding motifs SXSX20-FTAXY and the RCK_C domain (Moscoso et al., 2015; Blötz et al., 2017) were blasted against the Cbei proteome using the National Center for Biotechnology Information Protein BLAST tool.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted to compare the results of the treatment and control groups using RStudio (version 2024.09.0 + 375; Posit, PBC, MA, United States). The c-di-AMP concentrations, butanol tolerance, and enzyme activities of the three strains of Cbei studied were analyzed at 95% confidence interval and treatments with a p ≤ 0.05 were considered to show evidential difference. Also, Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was employed to identify the treatments with evidently different means. All treatments were analyzed in triplicates (n = 3).

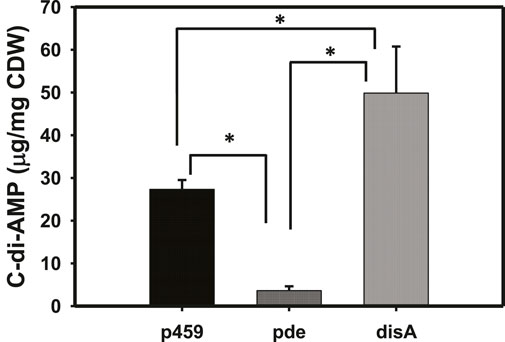

As expected, overexpressing disA and pde in Cbei resulted in significantly higher and lower intracellular concentrations of c-di-AMP, respectively (Figure 1). The levels of c-di-AMP were 1.83- and 4.20-fold higher and lower in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, respectively, relative to Cbei_p459 (p < 0.05). Compared to Cbei_pde, Cbei_disA contained 13.80-fold more c-di-AMP (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. C-di-AMP profiles in Cbei_p459, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_disA. P-values were calculated using c-di-AMP concentrations from three biological replicate cultures. p459 = Cbei_p459; pde = Cbei_pde; disA = Cbei_disA. Asterisks (*) denote statistical significance (p < 0.05) relative to the compared strain.

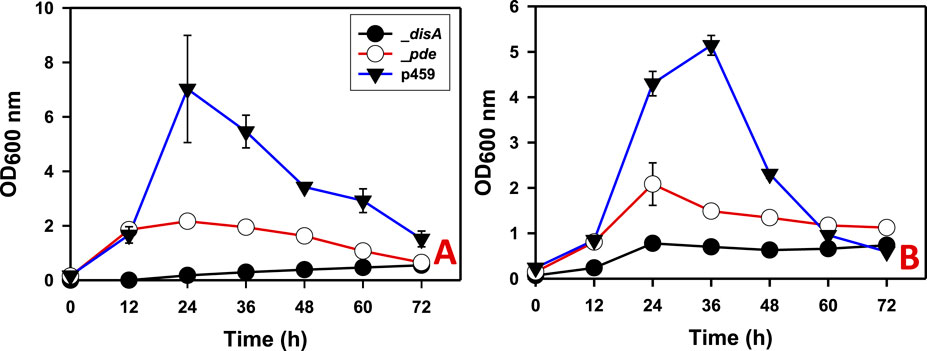

On both glucose and arabinose, overexpressing disA and pde significantly impaired growth in Cbei. Growth impairment was more pronounced in cultures of Cbei_disA which exhibited 6.60- and 12.80-fold reduced maximum optical densities on arabinose and glucose (p < 0.05), respectively, relative to Cbei_p459 (Figure 2). On the other hand, the maximum optical densities reached by Cbei_pde were 2.50- and 3.30-fold less than those recorded for Cbei_p459 on arabinose and glucose respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. The growth profiles of Cbei_disA, _pde, and _p459 on glucose and arabinose. (A) Glucose. (B) Arabinose. Dysregulated expression of disA and pde impaired growth in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde relative to Cbei_p459. Data is presented as the mean of three biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation. _disA = Cbei_disA; _pde = Cbei_pde; p459 = Cbei_p459.

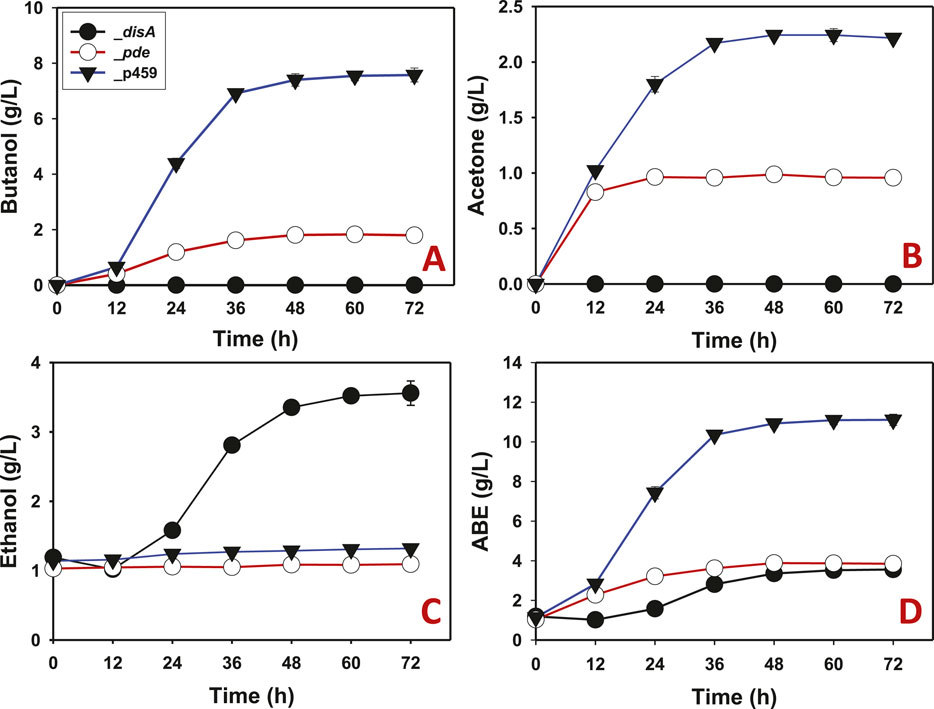

Butanol and acetone biosyntheses were completely inhibited in Cbei_disA grown on glucose (Figures 3A, B). Comparatively, Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde produced maximum butanol and acetone concentrations of 7.58 and 2.43 g/L and 1.83 and 1.00 g/L, respectively. Remarkably, Cbei_disA produced up to 2.73-fold more ethanol than Cbei_p459 and 3.30-fold more than Cbei_pde (p < 0.05; Figure 3C). Overall, Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde produced similar maximum concentrations of ABE (total solvents = acetone + butanol + ethanol; 3.60 and 3.9 g/L, respectively). These were at least 2.90-fold less than the maximum concentration detected in cultures of Cbei_p459 (p < 0.05; Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Solvent profiles of Cbei_p459, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_disA grown on glucose. (A) Butanol. (B) Acetone. (C) Ethanol. (D) ABE. Dysregulated expression of disA inhibited butanol and acetone biosynthesis. Dysregulated expression of pde impaired butanol and acetone production. Data is presented as the mean of three biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation.

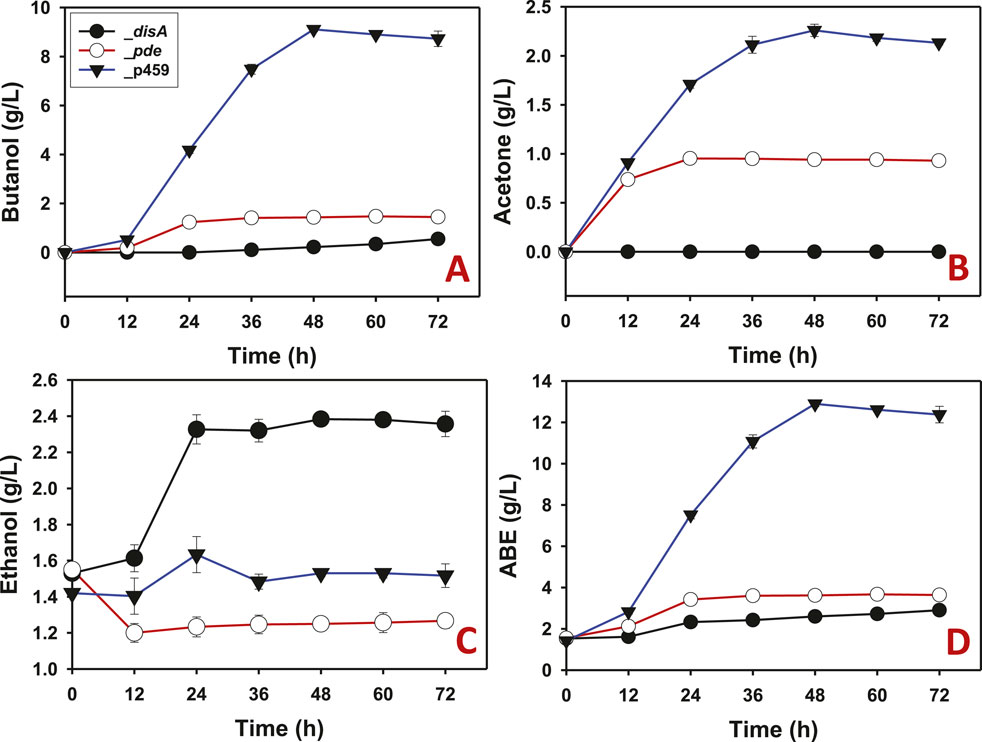

When arabinose was used as substrate, similar solvent profiles were observed for Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459 compared to glucose. As with glucose, butanol production was largely inhibited in arabinose-grown Cbei_disA, although a delayed marginal butanol production was observed with this strain. Whereas butanol was detected at 12 h in cultures of Cbei_pde and Cbei_p459, butanol was not detected in cultures of Cbei_disA until 36 h. A total of 0.55 g/L butanol was produced by Cbei_disA, which was 2.62- and 16.60-fold less than the maximum butanol titers produced by Cbei_pde and Cbei_p459, respectively (p < 0.05; Figure 4A). As observed with glucose, acetone biosynthesis was completely inhibited in Cbei_disA grown on arabinose whereas Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde produced 2.26 and 0.95 g/L acetone, respectively (Figure 4B). With arabinose as substrate, Cbei_disA produced 1.50-fold more ethanol than Cbei_p459 and 1.90-fold more than Cbei_pde (p < 0.05; Figure 4C). Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde produced similar ABE titers (2.90 and 3.67 g/L, respectively), which were at least 3.51-fold less than that produced by Cbei_p459 (p < 0.05; Figure 4D). Apparently, inhibition of butanol production in Cbei_disA elicited greater ethanol production, which accounts for the similarities in maximum ABE concentrations between Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde (Figures 3D, 4D).

Figure 4. The solvent profiles of Cbei_p459, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_disA grown on arabinose. (A) Butanol. (B) Acetone. (C) Ethanol. (D) ABE. Dysregulated expression of disA inhibited butanol and acetone biosynthesis. Dysregulated expression of pde impaired butanol and acetone production. Data is presented as the mean of three biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Exogenous supplementation of the enzyme assay mixtures with c-di-AMP resulted in a concentration dependent inhibition of BDH, BDDH, and ADC activities (Figure 5). With 5 nM c-di-AMP, at least 2.50-, 50.80-, and 4.00-fold reductions in activity were observed for BDH, BDDH, and ADC, respectively (p < 0.05). When the concentration of c-di-AMP was increased to 50 nM, ∼100% inhibition of activity was observed for BDH, BDDH, and ADC (p < 0.05). No significant inhibition in activity was observed for CoAT with 5 nM c-di-AMP (Figure 5). However, when c-di-AMP concentration was increased to 50 nM, CoAT activity was almost completely diminished.

Figure 5. Exogenous supplementation of 50 nM c-di-AMP inhibited the activities of butanol dehydrogenase (BDH), butyraldehyde dehydrogenase (BDDH), acetoacetate decarboxylase (ADC), and coenzyme A transferase (CoAT). Activities are expressed in units per mg protein (U/mg). Data is presented as the mean of three biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Compared to Cbei_p459, coenzyme A transferase genes (ctfAB) that encode enzymes involved in the reabsorption of acetic and butyric acids were significantly upregulated in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 h (Supplementary Figure S1; Table 1; p < 0.05). At 36 h, whereas these genes remained upregulated in Cbei_disA relative to Cbei_p459, they were significantly downregulated in Cbei_pde (p < 0.05; Supplementary Figure S1; Table 1). Cbei has five butanol dehydrogenase genes (adhE1, adhE2, bdhA, bdhB1 and bdhB2) that code for enzymes annotated to catalyze the final step in butanol biosynthesis (Zhao et al., 2020). These genes exhibited varying mRNA abundances in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde relative to Cbei_p459. Specifically, at 24 h adhE1, adhE2, bdhA, bdhB1, and bdhB2 were either unchanged or downregulated in Cbei_disA compared to Cbei_p459 (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S2; p < 0.05). However, at 36 h, with the exception of bdhB2, which was downregulated, all the butanol dehydrogenase genes studied were significantly upregulated in Cbei_disA relative to Cbei_p459 (p < 0.05). Interestingly, all the butanol dehydrogenase genes studied were either unchanged or downregulated in Cbei_pde relative to Cbei_p459 (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S2; p < 0.05). Acetoacetate decarboxylase gene (adc), of which the protein product catalyzes the final step in acetone biosynthesis was upregulated at both time points in both recombinant strains of Cbei except at 24 h in Cbei_pde (p < 0.05). Similarly, pyruvate carboxylase gene (pyc; Cbei_4960) was upregulated at both time points in Cbei_disA. On the other hand, pyc was upregulated at 24 h and downregulated at 36 h in Cbei_pde when compared to Cbei_p459.

With the exception of Cbei_3078 (which codes for PAS/PAC sensor hybrid histidine kinase) that was mostly downregulated, the genes involved in sporulation, transcription, and signal transduction that were studied (spo0A, sigE, σ70, and Cbei_0017 - histidine kinase) were mostly upregulated in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde when compared to Cbei_p459 at 24 and 36 h (Table 1; p < 0.05). As expected, disA exhibited higher mRNA abundances in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 and 36 h (p < 0.05). Interestingly, cdaA, which codes for a protein with c-di-AMP synthetase/DisA_N domain was downregulated in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 h, whereas the mRNA increased in abundance at 36 h (particularly in Cbei_pde), when compared to Cbei_p459. Similarly, the abundance of pde mRNA was significantly greater in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 and 36 h, relative to the empty plasmid control strain. Conversely, gdpP (c-di-AMP-specific phosphodiesterase) was downregulated in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 and 36 h (p < 0.05).

Butanol biosynthesis and sporulation occur simultaneously in solventogenic Clostridium species, with the rate of sporulation increasing with increasing butanol concentration in the culture (Long et al., 1984; Diallo et al., 2021). Previously, using a spore germination count approach we showed that knockdown of disA elicited up to 7.4-fold reduction in the rate of percentage spore formation relative to wildtype Cbei. In this study, we used microscopy to qualitatively confirm delayed sporulation in Cbei because of high and/or low c-di-AMP production. Phase contrast microscopy revealed extensive formation of endospores (58% spore formation) in Cbei_p459 at 24 h (Figure 6). Conversely, endospores were sparsely detected in cultures of Cbei_disA (1.5% spore formation) and Cbei_pde (6.33% spore formation). Notably, low incidence of endospores was more pronounced in Cbei_disA than in Cbei_pde. Scanning electron microscopy further highlighted the abundance of bulging endospores in Cbei_p459 than in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde at 24 h (Figure 7). As observed with phase contrast microscope, endospore formation was more prevalent in Cbei_pde than in Cbei_disA. Further, cell rupturing was observed in Cbei_pde but not in Cbei_disA and Cbei_p459 (Figure 7). Additionally, whereas the cells of Cbei_p459 appeared shorter, those of Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde were slender and longer, particularly Cbei_disA.

Figure 6. Sporulation is delayed in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde relative Cbei_p459. Arrows show endospores. Samples were viewed with ×100 magnification.

Figure 7. Delayed sporulation in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde relative Cbei_p459 and rupturing in Cbei_pde.

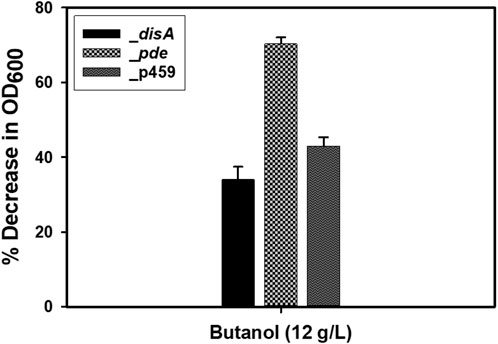

Given the role of c-di-AMP in sensing cell membrane damage and the role of butanol in membrane damage (Commichau et al., 2015; Cray et al., 2015; Gardner and Grosser, 2024), we assessed the effect of butanol and membrane-damaging KCl concentrations on Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde compared to Cbei_p459. Shock addition of 12 g/L butanol to the culture medium at 24 h exerted considerable stress on all three strains of Cbei studied (Figure 8). Electron microscopy revealed extensive rupturing in Cbei_p459 with pronounced appearance of cell debris around endospores. Whereas severe butanol-mediated damage was observed for Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, endospores were considerably less abundant in both strains, which retained their characteristic longer and slender morphologies. The cells of Cbei_p459 and Cbei_disA bore tiny holes whereas those of Cbei_pde were characterized by pronounced striations/markings—likely due to shrinking—that are absent in cells grown without butanol supplementation (Figure 7). The appearance of holes on the cells of Cbei_p459 and Cbei_disA was more pronounced in the latter. The morphologies of KCl-challenged cells indicate that butanol and KCl both negatively exert damaging effects on the Cbei cell membrane. However, micrographs suggest that they cause these effects via different mechanisms. When challenged with 25 mM KCl, the presence of striations was pronounced on cells of Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde. On the other hand, striations were less prominent on cells of Cbei_disA, which appeared smaller and flaccid with more pronounced rupturing than Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde (Figure 8). When 50 mM KCl was added to the cultures, cell rupture was observed in the cultures of all three strains of Cbei studied, with Cbei_p459 exhibiting a greater preponderance of striations (Figure 8). Apparently, cell rupture was more pronounced in Cbei_disA. Interestingly, both Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde had smaller cells than Cbei_p459 with 50 mM KCl. Flat and flaccid cells were more abundant in cultures of Cbei_pde challenged with 50 mM KCl than those of the same strain challenged with 25 mM KCl and 12 g/L butanol (Figure 8), and the unchallenged cells (Figure 7). Additionally, 8 hours after butanol (12 g/L) challenge, the optical densities of Cbei_disA, Cbei_p459, and Cbei_pde reduced 34%, 43%, 70%, respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 8. The effects of butanol (12 g/L) and KCl (25 and 50 mM) on Cbei_disA, Cbei_pde, and Cbei_p459. Arrows denote the presence of holes on cells. Striations were predominant in Cbei_pde treated with butanol and 25 mM KCl and Cbei_p459 treated with 25 and 50 mM KCl.

Figure 9. Percentage decreases in optical densities following butanol (12 g/L) challenge. Cloning and expression of disA in Cbei appeared to enhance tolerance to butanol. Data is presented as the mean of three biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Inhibition of solvent biosynthesis enzymes by exogenously supplemented c-di-AMP in vitro warranted a search of the Cbei proteome for c-di-AMP binding proteins. The results revealed 120 candidate proteins that harbor conserved c-di-AMP binding motifs (Supplementary Table S2). Among these, 35 proteins (29.2%) are involved in central metabolism and solventogenesis. Notably, three alcohol dehydrogenases including BdhA (Cbei_2421) with established involvement in butanol biosynthesis, hydrogenase (HypE), and [FeFe] hydrogenase, group A (Cbei_3796), which are known to take part in the ABE pathway (Tracy et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2020) were found to contain c-di-AMP binding motifs (Tables 2; Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, 15—i.e., 42.9%—of the proteins with c-di-AMP binding motifs involved in central metabolism are either associated with glycolysis or are directly involved in the ABE pathway (Tables 2; Supplementary Table S2). As expected, 34 (28.33%) of the proteins bearing c-di-AMP binding motifs are involved in transport while 14 (11.7%), 12 (10%), 9 (7.5%), 8 (6.7%), 5 (4.2%), and 3 (2.5%) are involved in cell wall synthesis/cell membrane biogenesis, cell motility and signal transduction, sporulation and stress response, replication andtranslation, and c-di-AMP synthesis and degradation, respectively.

Having previously shown that knockdown of disA increased butanol production and delayed sporulation in Cbei (Ujor et al., 2021), our aim in this study was to determine if and to what extent c-di-AMP—the product of DisA—directly affects butanol production in this organism. Plasmid-borne expression of c-di-AMP-producing DisA and c-di-AMP-hydrolyzing Pde was used to assess the effect of intracellular c-di-AMP levels on butanol production in Cbei. Further, we assayed for the activities of enzymes central to solvent biosynthesis with and without c-di-AMP supplementation. Additionally, we measured the expression levels of genes relevant to butanol biosynthesis, sporulation, signal transduction, and central metabolism. Our results show that both high and low physiological levels of c-di-AMP severely impair butanol and acetone biosynthesis in Cbei.

This effect was particularly pronounced in the c-di-AMP-replete background (Cbei_disA), where biosynthesis of both acetone and butanol were almost completely inhibited. Accordingly, high and low levels of c-di-AMP impaired sporulation, with high c-di-AMP levels exerting a far more severe inhibitory effect on sporulation. The results are discussed under different subheadings for clarity.

Spo0A, the master regulator of sporulation in solventogenic clostridia exerts a strong positive effect on butanol biosynthesis (Long et al., 1984; Diallo et al., 2021). Both Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde exhibited poor sporulation relative to Cbei_p459. Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al. (2011) showed that reduced intracellular c-di-AMP levels in B. subtilis delays sporulation. While this is in agreement with the delayed sporulation observed for Cbei_pde, the more severe delayed sporulation observed for Cbei_disA suggests that dysregulated production of c-di-AMP—and not just reduction in c-di-AMP levels—blunts the rate of sporulation in Cbei. Hence, we infer that sub-optimal intracellular levels of c-di-AMP negatively affect sporulation, which may stall solventogenesis, particularly, butanol and acetone production in Cbei. The mRNA levels of spo0A in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, coupled with the reduced rate of spore formation in both strains suggests that overproduction of c-di-AMP does not impair spo0A transcriptionally (Table 1). Therefore, it is plausible that c-di-AMP likely affects Spo0A and indeed, sporulation posttranslationally.

Whereas Spo0A was not found to contain a known c-di-AMP binding motif, a Spo0A-related protein (WP_011967480.1; Tables 2; Supplementary Table S2) contains a c-di-AMP binding motif. It is plausible that c-di-AMP might affect other proteins involved in sporulation downstream of Spo0A. In fact, asides the Spo0A-related protein that contains a c-di-AMP binding motif, seven other proteins involved in sporulation (Supplementary Table S2) also contain c-di-AMP binding motifs. Thus, cloning and purifying Spo0A (Cbei_1712) and the Spo0A-related protein (WP_011967480.1) and assaying for c-di-AMP binding, in combination with a global protein pulldown study will shed more light on how c-di-AMP limits sporulation in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde. More importantly, this promises to help delineate any interplays that exist at the nexus between c-di-AMP and Spo0A-mediated regulation of sporulation and solventogenesis in Cbei.

Careful examination of the butanol and acetone profiles show that Cbei_pde exhibited normal increases in butanol and acetone concentrations in the first 12 h of fermentation (Figures 3, 4). In fact, butanol and acetone concentrations in the cultures of Cbei_pde mirrored those of Cbei_p459 within the same period. Since both disA and pde were expressed under the adc promoter, which is auto-induced around 12 h when the culture pH drops following acid accumulation (i.e., acidogenesis; Tracy et al., 2012), it is logical therefore, to ascribe the drop-off in butanol and acetone production in Cbei_pde to the expression of pde. Notably, the vast majority of genes involved in solvent biosynthesis were significantly downregulated in Cbei_pde at both time points studied (24 and 36 h), albeit more at 36 h (Table 1; Supplementary Figures S1, S2).

In addition to the sharp drop in solvent production in Cbei_pde, the growth rate of this strain stopped mirroring that of Cbei_p459 after 12 h (Figure 2). Concomitantly, the mRNA abundance of pyruvate carboxylase gene (pyc; Cbei_4960), which codes for a key central metabolic enzyme, reduced drastically in Cbei_pde at 36 h (Table 1). Pyruvate carboxylase plays a crucial role in amino acid biosynthesis and lipid metabolism (Jitrapakdee and Wallace, 1999; Schär et al., 2010) and has been shown to be regulated by c-di-AMP in B. subtilis, Listeria monocytogenes and Lactococus lactis (Whiteley et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2017; Krüger et al., 2022). Taken together, these results are indicative of a gradual shift in gene expression profile, which leads to reduced growth and butanol and acetone biosynthesis in Cbei_pde. Given the membrane-damaging property of butanol and the cell rupture observed for Cbei_pde (Figure 7), we speculate that butanol biosynthesis and indeed, solventogenesis are aggressively scaled back in this strain, possibly to minimize the membrane damaging effect of butanol. Low intracellular levels of c-di-AMP lead to biosynthesis of inferior cell wall architecture, which leaves the cell membrane vulnerable to membrane damaging stressors (Wang et al., 2017) such as butanol.

Cell rupture observed for Cbei_pde, which produced at least 4.20-fold less butanol than Cbei_p459 supports this premise. More importantly, this might account for the arrest of solvent, particularly, butanol production in Cbei_pde. Given its chaotropic and ultimately, membrane damaging property (Figure 8), c-di-AMP being a sensor of membrane damaging stress may be recruited in Cbei to coordinate butanol biosynthesis. As such, impaired c-di-AMP accumulation in Cbei_pde and ultimately, the attendant inferior cell wall crosslinking (Wang et al., 2017) might elicit a regulatory sequence of cellular events that restrict butanol production.

Severe cell rupturing in Cbei_p459 relative to Cbei_disA following butanol challenge (Figure 8), lends weight to the notion that high intracellular levels of c-di-AMP in the latter may confer relatively higher tolerance to butanol. Whereas Cbei_pde did not exhibit as much cell rupturing as Cbei_p459 in butanol-supplemented cultures, electron microscopy suggests that this strain likely underwent severe shrinking (Figure 8). In fact, a significantly higher drop in cell density after butanol challenge of Cbei_pde (Figure 9) is indicative of a sharp drop in vegetative cell count. Comparatively, KCl caused greater cell shrinkage, whilst butanol brought about severe cell rupturing. Shrinking appears to be more severe in Cbei_disA than in Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde treated with KCl. C-di-AMP binds to, and inhibits osmolyte uptake proteins (Cereija et al., 2021; Gardner and Grosser, 2024). This mechanism is adroitly deployed to control osmolyte uptake in response to the concentrations of osmotic stressors in the culture medium.

At the prevailing high intracellular c-di-AMP level in Cbei_disA, c-di-AMP would prevent potassium uptake in KCl-replete culture, which may account for greater shrinking of cells in 50 mM KCl-treated cultures of Cbei_disA. Similarly, with a likely weaker cell wall architecture, Cbei_pde appeared to undergo greater KCl-induced cellular damage than Cbei_p459 treated with 50 mM KCl (Figure 8). Despite a similar morphology between Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, Cbei_disA exhibited more severe delayed sporulation than Cbei_pde and did not undergo rupturing in standard medium without an exogenous stressor. Resistance to cell membrane-damaging daptomycin has been linked to increased intracellular c-di-AMP concentration due to enhanced crosslinking of the cell wall (Wang et al., 2017; Zarrella and Bai, 2020). This phenomenon may account for the greater sturdiness observed for Cbei_disA when compared to Cbei_pde.

Compared to the control strain, the significantly reduced growth observed for Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, irrespective of the sugar studied, is in concordance with previous reports that described c-di-AMP as “an essential poison” (Gundlach et al., 2015; Huynh and Woodward, 2016). Relative to other second messengers, c-di-AMP is distinctive in that, it is essential for growth in the bacteria that produce it, whilst being toxic at unusually high concentrations (Gundlach et al., 2015; Huynh and Woodward, 2016; Herzberg et al., 2023). This informed the choice to express disA and pde under the control of the auto-inducible adc promoter, which becomes active about 12 h of growth. This was intended to allow considerable cell mass to accumulate before the expression of both genes. Therefore, the considerably higher and lower c-di-AMP levels in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, respectively, most plausibly account for the reduced growth in both strains. While the lower solvent profiles observed for both strains may be ascribed to poor growth due to the negative effects of lower and higher physiological levels of c-di-AMP in Cbei_disA and Cbei_pde, this phenomenon does not sufficiently explain the drop in solvent production in Cbei_pde after 12 h, and the near inhibition of butanol and acetone biosynthesis in Cbei_disA.

Even with the diminished cell mass in cultures of Cbei_disA, this strain produced the same concentrations of ABE on glucose and arabinose as Cbei_pde. This is because, whilst butanol and acetone biosyntheses were severely diminished in Cbei_disA, ethanol production increased significantly, indicating selective improvement in ethanol biosynthesis at the expense of butanol and acetone biosyntheses. Butanol is the major NADPH disposal outlet in Cbei and other solventogenic clostridia for the purpose of redox balance (Tracy et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2020; Agyeman-Duah et al., 2022). Thus, in the absence of butanol biosynthesis in Cbei_disA, the equally NADPH-dependent ethanol biosynthesis appears to be upregulated to address the ensuing potential redox imbalance. Lack of butanol (and acetone) biosynthesis in Cbei_disA hints at specific inhibition of both processes. Given the essentiality of c-di-AMP to bacteria that produce it (Gundlach et al., 2015; Huynh and Woodward, 2016; Herzberg et al., 2023), in addition to a likely response to cell rupturing in Cbei_pde (discussed earlier), marked and rapid reduction in physiological levels of c-di-AMP following pde expression might disrupt the progression of solventogenesis in this strain.

The negative effect of c-di-AMP on the activities of ADC, BDH, BDDH, and to some extent CoAT, suggests that excess intracellular levels of c-di-AMP may counteract acetone and butanol biosynthesis at the protein level in Cbei. This result points to possible direct interaction between c-di-AMP and ADC, BDH, and BDDH. Intracellular concentrations of c-di-AMP in bacteria, which are estimated between 1 and 5 μM (Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al., 2011) are tightly controlled via adroit regulation of c-di-AMP-synthesizing diadenylate cyclases (such as DisA) and c-di-AMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases (such as Pde). Remarkably, 5 nM c-di-AMP led to at least 55%, 45%, and 70% loss of ADC, BDH, and BDDH activities (Figure 5), respectively, whilst 50 nM c-di-AMP almost completely abolished the activity of each enzyme (ADC, BDH, and BDDH). Perhaps the physiological levels of c-di-AMP in Cbei are more tightly controlled with a significantly lower maximum threshold. More importantly, given the direct roles of ADC, BDH, and BDDH in acetone and butanol production, these results point to a possible role of c-di-AMP in regulating butanol and acetone biosynthesis in Cbei. This notion is supported by increased ethanol production in cultures of Cbei_disA (Figures 3, 4), given that ethanol is not as membrane damaging as butanol. Further, with the exception of coenzyme A transferase genes (which were upregulated), the genes for butanol biosynthesis enzymes were mostly downregulated in Cbei_disA at 24 h but were strongly upregulated in this strain at 36 h (Table 1). Further, spo0A and adc (involved in acetone production) were both significantly upregulated in Cbei_disA at 24 and 36 h. Nonetheless, these patterns (i.e., upregulated genes) did not amount to butanol or acetone production in this strain, thus, pointing to a possible underlying posttranscriptional c-di-AMP-mediated effect as the underpinning for this trend (i.e., lack of butanol and acetone production despite relevant gene upregulation). Increased ethanol production in Cbei_disA relative to Cbei_p459 and Cbei_pde suggests that an unidentified alcohol dehydrogenase that may not be affected by c-di-AMP, and with greater affinity for acetaldehyde as substrate than butyraldehyde is likely upregulated in Cbei_disA to dispose of excess NAD(P)H in the absence of butanol production.

Given the established ability of c-di-AMP to bind and inhibit a wide range of proteins (Cereija et al., 2021; Gardner and Grosser, 2024), coupled with the observed inhibition of ADC, BDH, and BDDH in vitro, c-di-AMP may directly affect solventogenic enzymes in Cbei at abnormally high intracellular concentrations. A search of the Cbei proteome revealed that BdhA, which participates in the terminal step of butanol biosynthesis (Tracy et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2020; Agyeman-Duah et al., 2022) contains a c-di-AMP binding motif (Table 1; Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, among the genes studied, bdhA was the most upregulated butanol dehydrogenase gene in Cbei_disA at 36 h (Table 1), when a strong upregulation was observed for most of the solventogenic genes studied. Although this is no confirmation that BdhA is the predominantly active butanol dehydrogenase at 36 h in Cbei_disA, the expression level and the presence of c-di-AMP binding motif in BdhA support the likelihood that excess intracellular c-di-AMP may disrupt some proteins involved in solventogenesis. Notably, seven other proteins involved or putatively involved in the ABE pathway were found to contain c-di-AMP binding motifs, thus, indicating that c-di-AMP may likely participate in the regulation of solventogenesis in Cbei.

It is important to note that the activities of some solventogenic enzymes (e.g., ADC and CoAT) in which c-di-AMP binding motifs were not found were also inhibited in vitro by c-di-AMP. It is either that c-di-AMP binds to motifs in these proteins that are not yet defined, or, that the activities of these enzymes are disrupted by c-di-AMP via a different mechanism. For example, the c-di-AMP-binding RCK_N domain of B. subtilis KtrA has been shown to also bind to ATP, ADP, NAD+, and NADH (Corrigan et al., 2013). Among the solventogenic enzymes studied, BDH and BDDH are NAD(P)H-dependent, which might be the basis for c-di-AMP-mediated inhibition of enzyme activities in the respective assays. However, this does not explain the basis for c-di-AMP mediated inhibition of ADC and to a lesser degree, CoAT. Cloning and purifying these enzymes and repeating these assays with c-di-AMP supplementation will provide additional insights as to how c-di-AMP inhibits the respective activities. More importantly, crystallographic analysis and substrate binding assays with purified enzymes in the presence of c-di-AMP will establish c-di-AMP binding as well as identify the potential binding pockets and motifs. Eight proteins central to the glycolytic pathway in Cbei were found to contain c-di-AMP binding motifs (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Potential inhibition of some of these proteins will likely impair growth (and ultimately, solventogenesis), which may explain the particularly poor growth observed for Cbei_disA. We are currently deploying a global protein pull-down approach to identify the broader spectrum of c-di-AMP binding proteins in Cbei. This will reveal to what extent c-di-AMP might contribute to the regulation of solventogenesis in this organism.

In conclusion, due to its capacity to detect membrane-damaging stress and the membrane damaging property of butanol, c-di-AMP may take part in the regulation of solventogenesis in Cbei. The results also suggest that c-di-AMP may coordinate the interplay between sporulation and butanol biosynthesis in Cbei. Demonstrating direct interaction between purified BDH, BDDH, and ADC and c-di-AMP will shed more light on how this second messenger inhibits butanol and acetone production in Cbei_disA. Furthermore, establishing direct interaction between c-di-AMP and Spo0A or other sporulation-related proteins, will prove instructive towards understanding the role of c-di-AMP in regulating sporulation and how this affects solvent biosynthesis in Cbei. Protein pull-down assay to identify and characterize c-di-AMP-binding proteins in Cbei will improve our understanding of the link between c-di-AMP-mediated regulation of solventogenesis and sporulation in Cbei.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MA-C: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SK: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. HT: Investigation, Writing–review and editing. EA-D: Investigation, Writing–review and editing. CO: Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. VU: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by grant from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Hatch Program (WIS05007).

We would like to thank Dr. David Hershey and his students and research staff (Bacteriology, UW-Madison, United States) for their assistance with phase contrast microscopy and Dr. Dhanashree Lokesh (Molecular and Cellular Imaging Center, The OSU, Wooster, OH, United States) for her kind assistance with scanning electron microscopy. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Tu-Anh Huynh (Food Science, UW-Madison) and her students and Dr. Greg Barrett-Wilt of the Biotechnology Center, UW-Madison for their immense assistance and support with LC-MS/MS analysis for c-di-AMP quantification.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2025.1547226/full#supplementary-material

Agyeman-Duah, E., Kumar, S., Gangwar, B., and Ujor, V. C. (2022). Glycerol utilization as a sole carbon source disrupts the membrane architecture and solventogenesis in Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Fermentation 8 (7), 339. doi:10.3390/fermentation8070339

Agyeman-Duah, E., Kumar, S., and Ujor, V. C. (2024). Screening recombinant and wildtype solventogenic Clostridium species for in vivo transformation of methylglyoxal and acetol to 1,2-propanediol. Process Biochem. 144, 278–286. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2024.06.016

Bejerano-Sagie, M., Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y., Berlatzky I Rouvinski, A., Meyerovich, M., and Ben-Yehuda, S. A. (2017). A checkpoint protein that scans the chromosome for damage at the start of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 125, 679–690. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.039

Blötz, C., Treffon, K., Kaever, V., Schwede, F., Hammer, E., and Stülke, J. (2017). Identification of the components involved in cyclic di-AMP signaling in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1328. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01328

Cereija, T. B., Guerra, J. P. L., Jorge, J. M. P., and Morais-Cabral, J. H. (2021). c-di-AMP, a likely master regulator of bacterial K+ homeostasis machinery, activates a K+ exporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2020653118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2020653118

Choi, P. H., Vu, T. M. N., Pham, H. T., Woodward, J. J., Turner, M. S., and Tong, L. (2017). Structural and functional studies of pyruvate carboxylase regulation by cyclic di-AMP in lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114 (35), E7226–E7235. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704756114

Commichau, F. M., Dickmanns, A., Gundlach, J., Ficner, R., and Stülke, J. (2015). A jack of all trades: the multiple roles of the unique essential second messenger cyclic di-AMP. Mol. Microbiol. 97 (2), 189–204. doi:10.1111/mmi.13026

Corrigan, R. M., Campeotto, I., Jeganathan, T., Roelofs, K. G., Lee, V. T., and Gründling, A. (2013). Systematic identification of conserved bacterial c-di-AMP receptor proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (22), 9084–9089. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300595110

Cray, J. A., Stevenson, A., Ball, P., Bankar, S. B., Eleutherio, E. C., Ezeji, T. C., et al. (2015). Chaotropicity: a key factor in product tolerance of biofuel-producing microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 33, 228–259. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.010

Diallo, M., Kengen, S. W. M., and López-Contreras, A. M. (2021). Sporulation in solventogenic and acetogenic clostridia. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105 (9), 3533–3557. doi:10.1007/s00253-021-11289-9

Fridovich, I. (1972). Acetoacetate decarboxylase. In: Ed.: P. D. Boyer The enzymes. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. 6, 255–270.

Gardner, T. M., and Grosser, M. R. (2024). A MRSA mystery: how PBP4 and cyclic-di-AMP join forces against β-lactam antibiotics. mBio 15, e0121024. doi:10.1128/mbio.01210-24

Gundlach, J., Mehne, F. M., Herzberg, C., Kampf, J., Valerius, O., Kaever, V., et al. (2015). An essential poison: synthesis and degradation of cyclic di-AMP in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 197, 3265–3274. doi:10.1128/jb.00564-15

Herzberg, C., Meißner, J., Warneke, R., and Stülke, J. (2023). The many roles of cyclic di-AMP to control the physiology of Bacillus subtilis. Microlife 4, uqad043. doi:10.1093/femsml/uqad043

Huynh, T. N., Luo, S., Pensinger, D., Sauer, J. D., Tong, L., and Woodward, J. J. (2015). An HD-domain phosphodiesterase mediates cooperative hydrolysis of c-di-AMP to affect bacterial growth and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (7), E747–E756. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416485112

Huynh, T. N., and Woodward, J. J. (2016). Too much of a good thing: regulated depletion of c-di-AMP in the bacterial cytoplasm. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2015.12.007

Jitrapakdee, S., and Wallace, J. C. (1999). Structure, function and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 340, 1–16. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3400001

Krüger, L., Herzberg, C., Wicke, D., Scholz, P., Schmitt, K., Turdiev, A., et al. (2022). Sustained control of pyruvate carboxylase by the essential second messenger cyclic di-AMP in Bacillus subtilis. mBio 13, e0360221–21. doi:10.1128/mbio.03602-21

Kumar, S., Agyeman-Duah, E., Awaga-Cromwell, M. M., and Ujor, V. C. (2024). Transcriptomic characterization of recombinant Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 expressing methylglyoxal synthase and glyoxal reductase from Clostridium pasteurianum ATCC 6013. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 11, e0101224. doi:10.1128/aem.01012-24

Long, S., Jones, D. T., and Woods, D. R. (1984). The relationship between sporulation and solvent production in Clostridium acetobutylicum P262. Biotechnol. Lett. 6, 529–534. doi:10.1007/bf00139997

Moscoso, J. A., Schramke, H., Zhang, Y., Tosi, T., Dehbi, A., Jung, K., et al. (2015). Binding of cyclic di-AMP to the Staphylococcus aureus sensor kinase KdpD occurs via the universal stress protein domain and downregulates the expression of the Kdp potassium transporter. J. Bacteriol. 198 (1), 98–110. doi:10.1128/jb.00480-15

Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y., Wexselblatt, E., Katzhendler, J., Yavin, E., and Ben-Yehuda, S. (2011). c-di-AMP reports DNA integrity during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep. 12, 594–601. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.77

Pilavtepe-Çelik, M., Balaban, M. O., Alpas, H., and Yousef, A. (2008). Image analysis based quantification of bacterial volume change with high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Sci. 73 (9), 423–429. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00947.x

Qureshi, N., and Ezeji, T. C. (2008). Butanol, ‘a superior biofuel’production from agricultural residues (renewable biomass): recent progress in technology. Biofuels, Bioprod. Bioref. 2, 319–330. doi:10.1002/bbb.85

Rørvik, G. H., Naemi, A. O., Edvardsen, P. K. T., and Simm, R. (2021). The c-di-AMP signaling system influences stress tolerance and biofilm formation of Streptococcus mitis. Microbiol. open 10, e1203. doi:10.1002/mbo3.1203

Schär, J., Stoll, R., Schauer, K., Loeffler, D. I. M., Eylert, E., Joseph, B., et al. (2010). Pyruvate carboxylase plays a crucial role in carbon metabolism of extra- and intracellularly replicating Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 192 (7), 1774–1784. doi:10.1128/jb.01132-09

Siemerink, M. A., Kuit, W., López Contreras, A. M., Eggink, G., van der Oost, J., and Kengen, S. W. M. (2011). D-2,3-butanediol production due to heterologous expression of an acetoin reductase in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2582–2588. doi:10.1128/aem.01616-10

Teh, W. K., Dramsi, S., Tolker-Nielsen, T., Yang, L., and Givskov, M. (2019). Increased intracellular cyclic di-AMP levels sensitize Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus to osmotic stress and reduce biofilm formation and adherence on intestinal cells. J. Bacteriol. 201 (6), e00597–18. doi:10.1128/jb.00597-18

Tracy, B. P., Jones, S. W., Fast, A. G., Indurthi, D. C., and Papoutsakis, E. T. (2012). Clostridia: the importance of their exceptional substrate and metabolite diversity for biofuel and biorefinery applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 364–381. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2011.10.008

Ujor, V. C., Lai, L. B., Okonkwo, C. C., Gopalan, V., and Ezeji, T. C. (2021). Ribozyme-mediated downregulation uncovers DNA integrity scanning protein A (DisA) as a solventogenesis determinant in Clostridium beijerinckii. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 669462. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.669462

Wang, X., Davlieva, M., Reyes, J., Panesso, D., Arias, C. A., and Shamoo, Y. (2017). A novel phosphodiesterase of the GdpP family modulates cyclic di-AMP levels in response to cell membrane stress in daptomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 (3), 014222–16. doi:10.1128/aac.01422-16

Whiteley, A. T., Garelis, N. E., Peterson, B. N., Choi, P. H., Tong, L., Woodward, J. J., et al. (2017). c-di-AMP modulates Listeria monocytogenes central metabolism to regulate growth, antibiotic resistance and osmoregulation. Mol. Microbiol. 104 (2), 212–233. doi:10.1111/mmi.13622

Zarrella, T. M., and Bai, G. (2020). The many roles of the bacterial second messenger cyclic di-AMP in adapting to stress cues. J. Bacteriol. 203. doi:10.1128/jb.00348-20

Keywords: cyclic-di-adenosine monophosphate, butanol, sporulation, solventogenic clostridia, DNA integrity scanning protein A, phosphodiesterase

Citation: Awaga-Cromwell MM, Kumar S, Truong HM, Agyeman-Duah E, Okonkwo CC and Ujor VC (2025) Dysregulated biosynthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic-di-adenosine monophosphate impedes sporulation and butanol and acetone production in Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 13:1547226. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2025.1547226

Received: 17 December 2024; Accepted: 10 February 2025;

Published: 28 February 2025.

Edited by:

Sanjay Kumar Singh Patel, Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University, IndiaReviewed by:

Venkata Giridhar Poosarla, Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management (GITAM), IndiaCopyright © 2025 Awaga-Cromwell, Kumar, Truong, Agyeman-Duah, Okonkwo and Ujor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victor C. Ujor, dWpvckB3aXNjLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.