- Institute of Orthopedic Research and Biomechanics, Center of Trauma Research Ulm, Ulm University Medical Center, Ulm, Germany

The aim of this biomechanical in vitro study was to answer the question whether the meniscus acts as a shock absorber in the knee joint or not. The soft tissue of fourteen porcine knee joints was removed, leaving the capsuloligamentous structures intact. The joints were mounted in 45° neutral knee flexion in a previously validated droptower setup. Six joints were exposed to an impact load of 3.54 J, and the resultant loss factor (η) was calculated. Then, the setup was modified to allow sinusoidal loading under dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) conditions. The remaining eight knee joints were exposed to 10 frequencies ranging from 0.1 to 5 Hz at a static load of 1210 N and a superimposed sinusoidal load of 910 N (2.12 times body weight). Forces (F) and deformation (l) were continuously recorded, and the loss factor (tan δ) was calculated. For both experiments, four meniscus states (intact, medial posterior root avulsion, medial meniscectomy, and total lateral and medial meniscectomy) were investigated. During the droptower experiments, the intact state indicated a loss factor of η = 0.1. Except for the root avulsion state (−15%, p = 0.12), the loss factor decreased (p < 0.046) up to 68% for the total meniscectomy state (p = 0.028) when compared to the intact state. Sinusoidal DMA testing revealed that knees with an intact meniscus had the highest loss factors, ranging from 0.10 to 0.15. Any surgical manipulation lowered the damping ability: Medial meniscectomy resulted in a reduction of 24%, while the resection of both menisci lowered tan δ by 18% compared to the intact state. This biomechanical in vitro study indicates that the shock-absorbing ability of a knee joint is lower when meniscal tissue is resected. In other words, the meniscus contributes to the shock absorption of the knee joint not only during impact loads, but also during sinusoidal loads. The findings may have an impact on the rehabilitation of young, meniscectomized patients who want to return to sports. Consequently, such patients are exposed to critical loads on the articular cartilage, especially when performing sports with recurring impact loads transmitted through the knee joint surfaces.

1 Introduction

Patients suffering from anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries (Gillquist and Messner, 1999; Lohmander et al., 2007; Bodkin et al., 2020), meniscus tears (Roos et al., 1998; Roos et al., 1999; Lohmander et al., 2007), or articular fractures of the knee (Weigel and Marsh, 2002; Buckwalter and Brown, 2004; Buckwalter et al., 2004) are up to 20 times more likely to develop post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) (Muthuri et al., 2011; Carbone and Rodeo, 2017; Thomas et al., 2017) compared to the healthy population. Traumatic meniscal tears are a frequent cause of disability and loss of work time (Mccann et al., 2009; Mcdermott, 2011; Badlani et al., 2013; Carbone and Rodeo, 2017), mostly affecting patients under 40 years of age (Ridley et al., 2017) and professional athletes (Majewski et al., 2006; Yeh et al., 2012; Snoeker et al., 2013). One of the superior goals of this active patient group is to return to work or sports as soon as possible. While arthroscopic suture repair provides a good prognosis for tears in the blood-supplied outer, so-called “red” and central “red-white” zone of the menisci, the healing potential for tears in the inner “white zone” is rather poor and remains a big clinical challenge (Bansal et al., 2021). Although being aware about the poor clinical long-term results (Andersson-Molina et al., 2002; Wachsmuth et al., 2003; Englund and Lohmander, 2004; Mcdermott and Amis, 2006; Intema et al., 2010; Salata et al., 2010), mechanically instable tears at the white zone are still mostly treated by partial meniscectomy, in order to obtain pain relief, avoid tear progression, and allow a faster return to different activities.

Besides biological alterations (Rai et al., 2019), biomechanical changes (Barton et al., 2017; Fischenich et al., 2017b) that are mainly related to the increased tibiofemoral contact pressure (Seitz et al., 2012; Sukopp et al., 2021) have been identified to be responsible for the amplification of PTOA progression after such meniscectomy procedures. Other than the main biomechanical function of tibiofemoral load transmission (Mcdermott et al., 2008), the frequently assigned shock-absorbing function of the menisci might also affect the knee joint homeostasis after meniscectomy. “The shocking truth about meniscus” by Andrews et al. (2011) revealed major flaws of the three most cited publications (Krause et al., 1976; Kurosawa et al., 1980; Voloshin and Wosk, 1983) that affiliate the meniscus with this shock-absorbing ability. Moreover, a recent commentary (Gecelter et al., 2021) came to the conclusion that based both on the mechanical properties and the evolutionary origin, the menisci are not shock absorbers. In contrast, there is evidence assigning a shock-absorbing function directly to the meniscus material itself (Pereira et al., 2014; Gaugler et al., 2015; Coluccino et al., 2017) and to the knee joint during activities of daily living (Winter, 1983; Ratcliffe and Holt, 1997). Therefore, the question remains whether the menisci play an active role as shock absorbers in the healthy, injured, and meniscectomized knee joints or not. Hence, the aim of this biomechanical in vitro study was to investigate the shock-absorbing function of the meniscus as an essential integrant of the knee joint during impact and repetitive loads.

Normal menisci have a highly anisotropic structure that is mainly composed of water (75%), collagen (23%), water-binding glycosaminoglycans (1%), and other matrix components leading to a time-dependent viscoelastic behavior (Herwig et al., 1984; Pereira et al., 2014; Seitz et al., 2021). While under static equilibrium conditions (Tibesku et al., 2004; Martin Seitz et al., 2013; Schwer et al., 2020) and repetitive loading (Kessler et al., 2006), the menisci exhibit considerable axial deformation, high impact, or shock loads, as seen, e.g., during jump landings, leading to an increase in their stiffness, and thus, to a decrease in the ability to reduce the transmitted stresses. Therefore, we hypothesize that the menisci contribute significantly to knee joint shock absorption during repetitive loads, while under impact loads, this shock absorption potential is absent.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The shock-absorbing potential of six porcine knee joints was investigated using a custom developed droptower setup, which provided one degree of freedom. After successful validation of the setup using defined damping materials, the joints were impacted with a total energy of 3.54 J. During the tests, only the meniscus states were successively varied to be able to relate the shock absorption potential directly to the menisci. These were intact, medial meniscus posterior root avulsion, medial meniscectomy, total lateral, and medial meniscectomy. The shock absorption was interpreted by the loss factor, which was calculated via the propagation time between two integrated load cells.

After modification of the test setup, a dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was conducted on eight porcine knees to investigate their shock-absorbing potential under repetitive, sinusoidal loads. For this purpose, a frequency scan including 10 different frequencies, ranging between 0.1–5 Hz at a constant load amplitude was performed while considering the four different meniscus states. The resultant shock absorption potential is calculated via the phase shift between force and displacement (strain) in order to draw conclusions about the influence of the meniscus on the damping in the knee joint.

2.2 Specimen Preparation

Fourteen fresh porcine hind limbs (liveweight ≈ 100 kg) were obtained for the experiments from a local butcher. The soft tissues were removed, leaving the capsuloligamentous knee joint structures intact. Before the tibial bone was shortened to a length of 4 cm in distance to the knee joint gap, the head of the fibula was secured using a setscrew. A precision miter screw allowed for plane parallel resection of the femoral bone in 5 cm distance to the joint gap and 45° neutral knee joint flexion (Proffen et al., 2012). During the preparation process, the tissues were kept moist using physiologic saline solution. After the preparation process, the specimens were wrapped in saline saturated gauze and stored at −20°C until the day of testing.

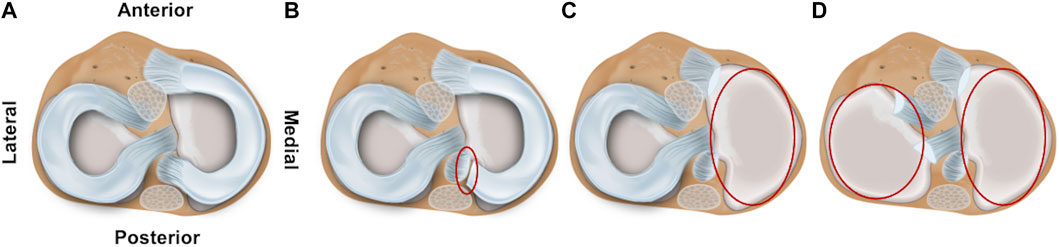

Both for the impact and for the repetitive (DMA) loading experiments, four meniscus states (intact, medial posterior root avulsion, medial meniscectomy, and total lateral and medial meniscectomy) were investigated to identify the shock-absorbing function of the meniscus (Figure 1). The meniscus preparation steps were conducted as minimally invasive as possible by an orthopedic surgeon. During these preparation steps, the knee joints were kept in the respective testing setup to avoid a misplacement bias by disassembling and reassembling.

FIGURE 1. Schematic drawing of the axial view on a tibial plateau of a left knee joint. The femur is removed to allow better visualization of the four investigated meniscal states: (A) intact, (B) avulsion of the posterior medial meniscus horn, (C) medial meniscectomy, and (D) total lateral and medial meniscectomy.

2.3 Test Setup and Validation

2.3.1 Droptower Setup

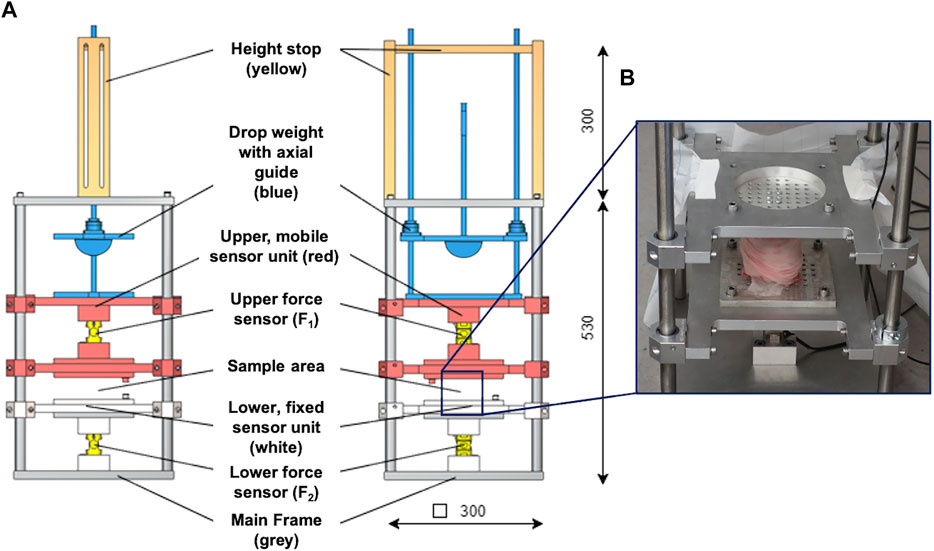

The droptower test setup configuration consisted of a weight-adjustable (up to 200 N), axially guided drop weight with a height stop and a hemispherical, stainless-steel impactor, which allows for pinpoint impact transmission (Figure 2). The drop weight hit the impact pad that was mounted to the mobile upper sensor unit containing a screwed-in 10 kN force sensor (KM30z, ME GmbH, Germany) to which the upper sample holder was connected with four knurled screws. Accurate and low-friction axial guidance of the upper sensor unit was ensured using eight linear ball bearings. The test sample was fixed between the two sample holders, while the lower sample holder was axially guided by four linear ball bearings. The lower sensor contained another screwed-in 10 kN force sensor (KM30z, ME GmbH, Germany) that was rigidly connected to the main frame. The test setup provided only one degree of freedom in the axial direction. This was guided by a total of twelve low-friction linear ball bearings, which were in contact with the stainless-steel main frame.

FIGURE 2. (A) Technical drawing of the droptower setup in the side (left) and frontal (middle) view. The setup consisted of a height stop (ochre), which was directly connected to the axial guidance system of the drop weight. A hemisphere impactor (blue) was used to allow for pinpoint impact transmission. The upper, mobile sensor unit (red) is axially guided by eight axial ball bearings and incorporates the upper force sensor. It is further connected to an impact pad at its top end and to a sample holder at the lower end. The lower, fixed sensor unit (white) is also axially guided by four axial ball bearings and incorporates the lower force sensor. The lower end of this sensor unit is directly connected to the main frame. (B) Example of an installed porcine knee joint at the sample area at the droptower setup.

The two series-connected force sensors were used to determine the shock wave propagation by measuring the impact loads at the upper (F1) and lower sensor (F2) with the corresponding propagation time (Δt). The measurements were used to calculate the loss factor (

while for viscoelastic materials (e.g., articular cartilage or menisci), it can be assumed that

where D is the damping factor and calculated by

with

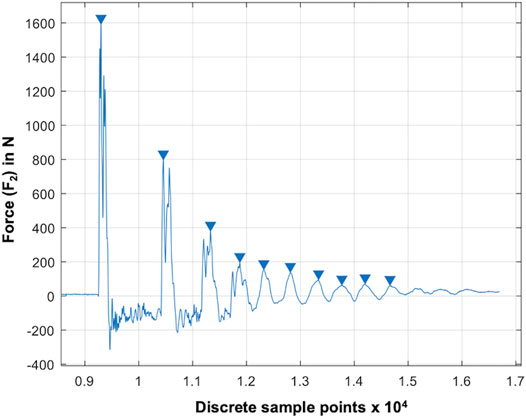

We used the maxima at the lower force sensor (F2), as they equal to the reaction force, and thus, vary in accordance with the shock absorption ability of the test samples (Figure 3). Based on pretests identifying the potential impact frequencies and following the Nyquist theorem, the sampling rate was set to 30 kHz. Validation of the test setup was conducted using seven special damping materials made of polyurethane foam, indicating specific damping properties and a known loss factor (

FIGURE 3. Result graph of a droptower validation test using a known damping material (RF220). The blue arrows indicate automatically determined local maxima (xn: blue arrows) at the lower force sensor (F2). The force is given over the discrete sample points at a sampling rate of 20 kHz.

2.3.2 Dynamic Mechanical Analysis Setup

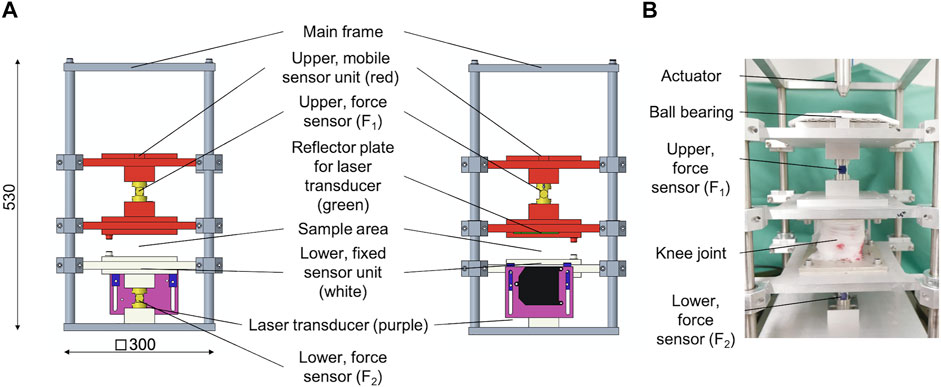

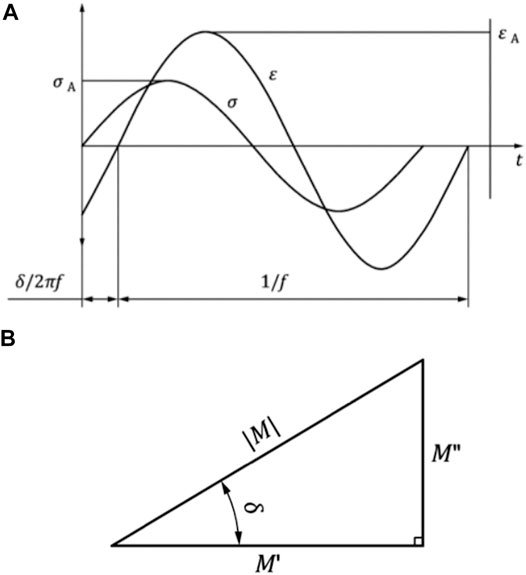

The modular design of the test setup allows for a fast removal of the height stop and drop weight assembly. This is necessary to allow for an integration of the test setup in the work space of a standard hydraulic dynamic materials testing machine (Instron 8871, Norwood MS, United States) with a total capacity of 10 kN. A multiaxial ball bearing was placed between the upper sensor unit and the actuator of the dynamic materials testing machine (Figure 4) to protect the load cell. The setup was centered and rigidly clamped to the base plate of the materials testing machine. An external high-precision laser length transducer (accuracy: ± 0.6 μm; optoNCDT 2201, Micro-Epsilon Eltrotec GmbH, Göppingen, Germany), which was installed at the lower sensor unit, was used together with its reflection plate counterpart that was firmly connected to the upper sensor unit to measure the sample deflection (l). During the DMA tests, the phase angle (δ), the applied oscillation input (force) amplitude (F2,A), and the resultant oscillation output (deflection) amplitude (lA) were continuously recorded (Figure 5). Based on these three parameters, the storage modulus (M′) was determined (Ehrenstein et al., 2004) by

while the loss modulus (M″) is calculated by

FIGURE 4. (A) Technical drawing of the modified dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) setup in side (left) and frontal (middle) view. The upper, mobile sensor unit (red) is axially guided by eight axial ball bearings and incorporates the upper force sensor. On its top, there is a multiaxial ball bearing to protect the load cell of the dynamic testing machine, while at the lower end, there is a reflector plate (green) for a laser transducer installed. The lower, fixed sensor unit (white) is axially guided by four axial ball bearings and incorporates the lower force sensor as well as an external, high-precision laser length transducer. The lower end of this sensor unit is directly connected to the main frame. (B) Example of an installed porcine knee joint at the sample area at the DMA setup.

FIGURE 5. (A) Representative force-induced sinusoidal oscillation (F) and the respective deflection response (l) of a viscoelastic material. The time-dependent, characteristic shift (δ/2πf) of the force (FA) versus the deflection (lA) amplitudes are plotted over the time (t). (B) Relation between the storage modulus M′, the loss modulus M″, the phase angle δ, and the magnitude (M) of the complex modulus M*. Images are in accordance with DIN EN ISO 6721-1:2018-03.

Based on both moduli, the loss factor (tan δ) can be calculated by

In addition, the complex modulus E* results from the storage modulus (M′) and the imaginary part (1) of the loss modulus (M″). It is also called dynamic modulus and indicates the behavior of stress to strain under oscillating loads:

Validation of the DMA test setup was conducted using the same seven damping materials (PUR RF, REGUPOL BSW GmbH, Bad Berleburg, Germany) as those for the droptower setup validation with a known loss factor (

Synchronized data acquisition for both the droptower (F1, F2, Δt) and DMA (F1, F2, l, and force/displacement output of the materials testing machine) setup measurements was achieved using a USB data acquisition card (USB-6218, NI Corp., Austin TX, United States) and a customized LabVIEW software (LabVIEW 2019; NI Corp., Austin TX, United States). Subsequent data postprocessing was performed using customized MATLAB scripts (MATLAB 2019b; The MathWorks Inc., Natick MA, United States).

2.4 Droptower Experiments

Based on the results of a study investigating the impact-absorbing properties of a healthy and meniscectomized knee joint (Hoshino and Wallace, 1987), an a priori sample size calculation [G∗Power 3.1.9.2 (Faul et al., 2007): α = 0.05, Power (1 – β) = 0.95, effect size (dz) = 2.79, n = 4] was performed to ensure sufficient statistical power [Actual power = 0.98] of the study. In order to be able to identify differences after simulating a meniscus tear, the sample size was increased to n = 6.

At the day of testing, the joints were thawed at room temperature and subsequently centrally mounted between the two sample holders using 4–6 proximal and eight distal screws in 45° neutral knee joint flexion (Proffen et al., 2012). To account for the viscoelastic behavior of the knee soft tissues, the joints were loaded 12 min prior to testing with 120 N, following an established protocol (Maher et al., 2017). During preconditioning, the drop height was adjusted to 172 mm and the drop weight was adjusted to 2.1 kg, resulting in an impact energy of 3.54 J, which is double of that used by Hoshino et al. (1.77 J) (Hoshino and Wallace, 1987). After application of the impact and successful crosscheck of the data recording, the joint was unloaded and allowed to undergo relaxation for 12 min. The tests were repeated three times, resulting in a total test time of 90 min for each meniscus state. The mean values of these three measurements were used for further analyses. Then, the next meniscus preparation step was performed and the experiments were repeated. After each preparation step the joint capsule incision was fixed by surgical sutures. The sampling rate during the droptower experiments was set to 30 kHz. During the tests, the joints were kept moist by constantly misting physiological saline solution.

2.5 Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

Based on the results of a similar study performing a DMA on human menisci (Pereira et al., 2014), an a priori sample size calculation [G∗Power 3.1.9.2 (Faul et al., 2007): α = 0.05, Power (1−β) = 0.80, effect size (dz) = 1.15, n = 7] was performed to ensure sufficient statistical power [Actual power = 0.85] of the study. Comparators to determine the effect size dz were tan δ values (mean ± SD) of the anterior medial menisci and mid body medial menisci values. In order to be able to identify differences after simulating meniscus pathologies, the sample size was increased to n = 8.

At the day of testing, the porcine knee joints were thawed and centrally applied in the modified DMA test setup in 45° neutral knee joint flexion (Proffen et al., 2012). A total of 8–12 screws were used to secure the specimen against translation. Taylor et al. (2006) identified an axial knee joint loading of 2.12 times body weight (BW) during the stance phase and 0.3 times BW during the swing phase of normal gait in sheep knees. Since sheep and pigs are similar in their neutral knee position and gait (Proffen et al., 2012), these values were transferred to the forces in the porcine knee, resulting in a static load of 1,210 N and a superimposed sinusoidal load of 910N, which was applied to the porcine knee joints. As a result, peak loads of 2120 N and minimum loads of 300 N were identified for the sinusoidal DMA tests. Additionally, the joints were loaded 12 min prior to testing with 300 N to account for the viscoelastic behavior of the knee soft tissues (Maher et al., 2017). A total of ten frequencies (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 Hz) were arranged randomly for each knee and scanned directly one after the other, in accordance with this randomized sequence. The frequency range was adapted from Pereira et al. (2014) and cropped to the frequencies that match best to those observed during gait, running, and other daily activities (Danion et al., 2003; Simoni et al., 2021). The sampling rate was adapted to the respective frequency in a way that 1,000 values were recorded per single sinusoidal oscillation, resulting in a total of 10,000 measurement points per DMA run. After the intact meniscus state investigation, the joints were allowed to undergo relaxation for 12 min. Then, the next meniscus preparation step was performed and the experiments were repeated. After each preparation step, the joint capsule incision was fixed by surgical sutures. During the tests, the joints were continuously kept moist by constantly misting physiological saline solution.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Gaussian distribution of the results data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, resulting in non-normally distributed data for the droptower and normally distributed data for the DMA experiments. Thus, non-parametric (droptower) and parametric (DMA) statistical analyses were performed using a statistical software package (SPSS v24, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

In detail, for the droptower experiments, F2 and

3 Results

3.1 Droptower Experiments

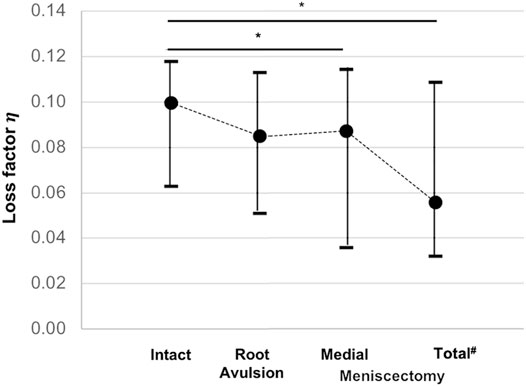

Friedman testing revealed significant differences in both the force maxima at the lower force sensor (F2; p = 0.02) and the loss factor (

FIGURE 6. Minimum, median, and maximum loss factor (

3.2 Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

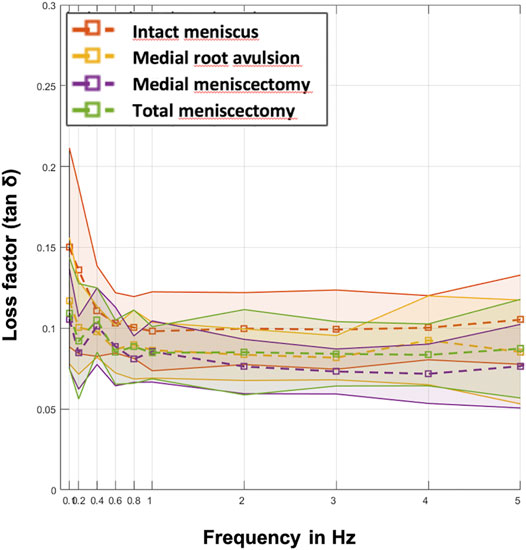

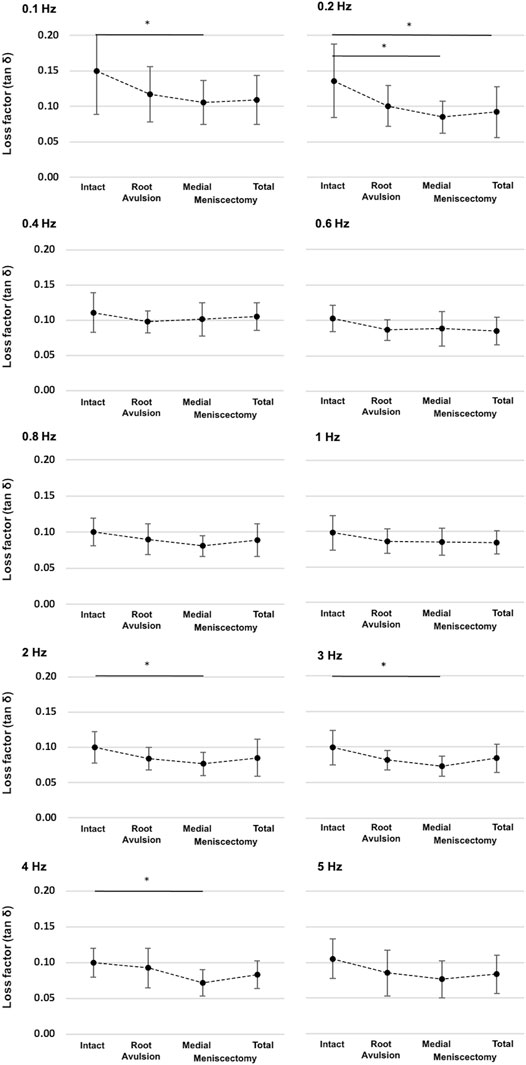

Parametric statistical analyses revealed that knees with an intact meniscus had the highest loss factors, ranging from tan δ = 0.10 to tan δ = 0.15 throughout all investigated frequencies (Figure 7). Each consecutive simulated meniscus deterioration lowered the loss factor. Thus, after posterior medial root avulsion, the mean value of the loss factor (tan δ) was reduced by 15%, while medial meniscectomy resulted in a reduction of 24%. The resection of both the lateral and medial menisci resulted in a reduction of 18% compared to the intact meniscus state. When comparing the meniscal states at specific frequencies in detail (Figure 8), one-way ANOVA with Duncan post-hoc testing indicated significant differences for the comparisons of the intact state and the medial meniscectomy at 0.1, 0.2, 2, 3, and 4 Hz (p < 0.04) and for the comparisons of the intact meniscus state and the total meniscectomy at 0.2 Hz (p = 0.02).

FIGURE 7. Mean values (dashed lines) of the loss factor (tan δ) ± SD (represented by the envelope in the same color) plotted over the ten investigated frequencies (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 Hz) at the four meniscal states (red: intact menisci; yellow: avulsion of the posterior medial meniscus horn; purple: medial meniscectomy; green: total lateral and medial meniscectomy). n = 8.

FIGURE 8. Detailed representation of the loss factor (tan δ) ± SD at the ten investigated frequencies (0.1–5 Hz) and under the four investigated meniscus states: intact, root avulsion at the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, medial meniscectomy, and total lateral and medial meniscectomy. The dotted line indicates the progression of the consecutively investigated meniscus states. *One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Duncan test: *p < 0.05; n = 8.

4 Discussion

In this biomechanical in vitro study, we investigated the shock-absorbing potential of the menisci inside porcine knee joints during impact loading and repetitive sinusoidal loads by applying a DMA. The test setup was successfully validated for both applications. Both during the impact loads and during the DMA analysis, the loss factor (

Hoshino and Wallace (1987) investigated the shock absorption potential of human menisci in 20 knee joints and found a comparable reaction force increase of 21% for the comparison between the intact and the total meniscectomized knee joint. Also, for the root avulsion and medial meniscectomy conditions, our relative values were in a very similar range (108–109%). Regarding the force at the lower sensor (F2), Hoshino et al. determined forces of up to 1600 N, thus being 400 N higher compared to the F2 forces of the present study. This might be due to the more pronounced curvature of the porcine tibial, potentially resulting in higher shear forces, which might be transmitted to other joint structures in the porcine knee. Chu et al. (1986) investigated the shock wave propagation during dynamic loading in six human lower limbs using accelerometers and force transducers. They measured an average increase in impulse force of 11% at the tibia and 23% at the femur, after total meniscectomy and removal of the articular cartilage. In the present study, F2 increased by 24% only after total meniscectomy. In contrast, Chu et al. also removed cartilage structures. Articular cartilage has been shown to possess a 40-times higher complex modulus (E*) (Temple et al., 2016) compared to the menisci (Pereira et al., 2014; Fischenich et al., 2017a). This might be interpreted in a way that the menisci seem to be more responsible for the increased tibial forces in the Chu study (Chu et al., 1986). Therefore, the results of Chu et al. differ by only 1% to the results of the present study. In their work, Kurosawa et al. (1980) examined a total of 14 human knee joints under quasi-static loads of 500, 1,000, and 1,500 N at a loading rate of 5 mm/min. They observed higher energy dissipation in meniscectomized knee joints than intact knee joints at all loading levels. These findings are in contrast to the ones obtained in the present study and to those from Hoshino and Wallace (1987) and Chu et al. (1986). However, compared to the other studies, the transmitted energy during the loading reached only 0.023 J at a load of 1500 N. Thus, the results from Kurosawa are difficult to compare with the present study and are more likely to reflect the energy absorption potential during creep loading of all viscoelastic knee joint structures.

Pereira et al. (2014) investigated in their study the viscoelastic response of isolated human meniscus tissue at a frequency range of 0.1–10 Hz under displacement-controlled conditions. They subdivided the menisci into their anatomical regions (anterior horn, pars intermedia, posterior horn) and determined variations of the loss factor (tan δ) at 1 Hz from 0.12 at the posterior lateral meniscus to 0.18 in the anterior medial meniscus. In accordance to the findings of the present study, Pereira also showed a frequency dependent response: while at low frequencies (0.1–0.6 Hz) high loss factor values (∼0.2) and a loss factor minimum at 1 Hz were observed, high frequencies (>3 Hz) again led to high loss factor values. Gaugler et al. (2015) investigated in their study on isolated meniscus tissue both sinusoidal loads at a frequency of 0.1 Hz and impact loads and found loss factors of 0.3 for sinusoidal and 0.17 for impact loads. The findings of our study are within the same range as those from Gaugler et al. and indicate the same ratio when comparing sinusoidal and impact loads. Additionally, Coluccino et al. (2017) investigated the viscoelastic response of bovine meniscus explants and found both similar ranges of the loss factor (tan δ) of, e.g., 0.17 at 0.1 Hz and a similar frequency dependency of the damping response of the meniscus within the range from 0.1 to 5 Hz.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of the present in vitro study. First, due to the very good availability and standardized phenotype, we used a porcine knee joint model in our study investigation. Although the porcine knee showed only acceptable appearance congruence for the ACL and lateral menisci (Proffen et al., 2012) and differences in the viscoelastic properties (Sandmann et al., 2013) when compared to the human knee joint, the relative comparisons were in a similar range than those observed in a human cadaver study, both for the impact (Hoshino and Wallace, 1987) and the DMA conditions investigating isolated menisci [tan δ ∼ 0.2; (Pereira et al., 2014)]. Furthermore, the test setup provided only one translational degree of freedom in the axial direction. However, during pretests, we experienced significant evasive rotational movement of the porcine knee joint under compressive loads, especially after the two meniscectomy states. In consequence, the obtained shock absorption results were significantly biased by these evasive movements and the resultant influence of the viscoelastic response of the surrounding soft tissues, while providing more physiological degrees of freedom.

5 Conclusion and Outlook

The results of this biomechanical in vitro study indicate that the meniscus significantly contributes to the shock absorption of the porcine knee joint both under impact loads and under more moderate, sinusoidal loads at different frequencies. The findings may have an impact on the rehabilitation of young, meniscectomized patients that want to return to sports as soon as possible. Such patients are exposed to critical loads carried by the articular cartilage, when performing shock intensive sports like skiing, volleyball, etc. In summary, a partial meniscectomy leads not only to a reduced tibiofemoral contact area, but also to an inhibited shock-absorbing potential of the meniscus and, thus, to an increased contact pressure. Consequently, during the meniscectomy procedure, care should be taken to save as much meniscal tissue as possible, underlining the clinical findings to save the meniscus (Lubowitz and Poehling, 2011; Seil and Becker, 2016; Lee et al., 2019; Pujol and Beaufils, 2019)—also from a shock absorption point of view. A meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) procedure is able to biomechanically restore the injured or (partially) meniscectomized knee joint to the original, healthy state (Koh et al., 2019; Seitz and Durselen, 2019; Zaffagnini et al., 2019). However, not only from a biomechanical point of view, but also from a clinical point of view, especially when patients present persisting post-meniscectomy syndromes, does MAT represent a viable option to decrease pain, improve knee joint function, and, thus, delay the onset of PTOA after meniscus injury (Zaffagnini et al., 2016; De Bruycker et al., 2017).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the animal study because the porcine knee joints were received from a local butcher.

Author Contributions

AS and JS performed the specimen preparation, data analysis, and statistics. AS drafted the manuscript. DW and LdR conducted the mechanical testing. AI and LD participated in the design and coordination of the study. LD conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Kreienbaum and L. Wächter from the Technische Hochschule Ulm for their technical support and Patrizia Horny from the Institute of Orthopedic Research and Biomechanics Ulm for her art design support.

References

Andersson-Molina, H., Karlsson, H., and Rockborn, P. (2002). Arthroscopic Partial and Total Meniscectomy. Arthrosc. J. Arthroscopic Relat. Surg. 18, 183–189. doi:10.1053/jars.2002.30435

Andrews, S., Shrive, N., and Ronsky, J. (2011). The Shocking Truth about Meniscus. J. Biomech. 44, 2737–2740. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.08.026

Badlani, J. T., Borrero, C., Golla, S., Harner, C. D., and Irrgang, J. J. (2013). The Effects of Meniscus Injury on the Development of Knee Osteoarthritis. Am. J. Sports Med. 41, 1238–1244. doi:10.1177/0363546513490276

Bansal, S., Floyd, E. R. M., Kowalski, M., Elrod, P., Burkey, K., Chahla, J., et al. (2021). Meniscal Repair: The Current State and Recent Advances in Augmentation. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 1368–1382. doi:10.1002/jor.25021

Barton, K. I., Shekarforoush, M., Heard, B. J., Sevick, J. L., Vakil, P., Atarod, M., et al. (2017). Use of Pre-clinical Surgically Induced Models to Understand Biomechanical and Biological Consequences of PTOA Development. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 454–465. doi:10.1002/jor.23322

Bodkin, S. G., Werner, B. C., Slater, L. V., and Hart, J. M. (2020). Post-traumatic Osteoarthritis Diagnosed within 5 Years Following ACL Reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 790–796. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05461-y

Buckwalter, J. A., and Brown, T. D. (2004). Joint Injury, Repair, and Remodeling. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 423, 7–16. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000131638.81519.de

Buckwalter, J. A., Saltzman, C., and Brown, T. (2004). The Impact of Osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 427, S6–S15. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000143938.30681.9d

Carbone, A., and Rodeo, S. (2017). Review of Current Understanding of post-traumatic Osteoarthritis Resulting from Sports Injuries. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 397–405. doi:10.1002/jor.23341

Chu, M. L., Yazdani-Ardakani, S., Gradisar, I. A., and Askew, M. J. (1986). An In Vitro Simulation Study of Impulsive Force Transmission along the Lower Skeletal Extremity. J. Biomech. 19, 979–987. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(86)90115-6

Coluccino, L., Peres, C., Gottardi, R., Bianchini, P., Diaspro, A., and Ceseracciu, L. (2017). Anisotropy in the Viscoelastic Response of Knee Meniscus Cartilage. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 15, e77–e83. doi:10.5301/jabfm.5000319

Danion, F., Varraine, E., Bonnard, M., and Pailhous, J. (2003). Stride Variability in Human Gait: the Effect of Stride Frequency and Stride Length. Gait & Posture 18, 69–77. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(03)00030-4

De Bruycker, M., Verdonk, P. C. M., and Verdonk, R. C. (2017). Meniscal Allograft Transplantation: a Meta-Analysis. SICOT-J 3, 33. doi:10.1051/sicotj/2017016

Ehrenstein, G. W., Riedel, G., and Trawiel, P. (2004). Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA). Carl Hanser Verlag Gmbh Co. KG 1, 236–299. doi:10.3139/9783446434141.006

Englund, M., and Lohmander, L. S. (2004). Risk Factors for Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis Fifteen to Twenty-Two Years after Meniscectomy. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 2811–2819. doi:10.1002/art.20489

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi:10.3758/bf03193146

Fischenich, K. M., Boncella, K., Lewis, J. T., Bailey, T. S., and Haut Donahue, T. L. (2017a). Dynamic Compression of Human and Ovine Meniscal Tissue Compared with a Potential Thermoplastic Elastomer Hydrogel Replacement. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 105, 2722–2728. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.36129

Fischenich, K. M., Button, K. D., Decamp, C., Haut, R. C., and Donahue, T. L. H. (2017b). Comparison of Two Models of post-traumatic Osteoarthritis; Temporal Degradation of Articular Cartilage and Menisci. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 486–495. doi:10.1002/jor.23275

Gaugler, M., Wirz, D., Ronken, S., Hafner, M., Göpfert, B., Friederich, N. F., et al. (2015). Fibrous Cartilage of Human Menisci Is Less Shock-Absorbing and Energy-Dissipating Than Hyaline Cartilage. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 23, 1141–1146. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2926-4

Gecelter, R. C., Ilyaguyeva, Y., and Thompson, N. E. (2021). The Menisci Are Not Shock Absorbers: A Biomechanical and Comparative Perspective. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 1, 1. doi:10.1002/ar.24752

Gillquist, J., and Messner, K. (1999). Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and the Long Term Incidence of Gonarthrosis. Sports Med. 27, 143–156. doi:10.2165/00007256-199927030-00001

Herwig, J., Egner, E., and Buddecke, E. (1984). Chemical Changes of Human Knee Joint Menisci in Various Stages of Degeneration. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 43, 635–640. doi:10.1136/ard.43.4.635

Hoshino, A., and Wallace, W. (1987). Impact-absorbing Properties of the Human Knee. The J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. volume 69-B, 807–811. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.69b5.3680348

Intema, F., Hazewinkel, H. A. W., Gouwens, D., Bijlsma, J. W. J., Weinans, H., Lafeber, F. P. J. G., et al. (2010). In Early OA, Thinning of the Subchondral Plate Is Directly Related to Cartilage Damage: Results from a Canine ACLT-Meniscectomy Model. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 18, 691–698. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.004

Jäger, H., Mastel, R., and Knaebel, M. (2016). Technische Schwingungslehre. Wiesbaden: Springer Vieweg.

Kessler, M. A., Glaser, C., Tittel, S., Reiser, M., and Imhoff, A. B. (2006). Volume Changes in the Menisci and Articular Cartilage of Runners. Am. J. Sports Med. 34, 832–836. doi:10.1177/0363546505282622

Koh, Y.-G., Lee, J.-A., Kim, Y.-S., and Kang, K.-T. (2019). Biomechanical Influence of Lateral Meniscal Allograft Transplantation on Knee Joint Mechanics during the Gait Cycle. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 14, 300. doi:10.1186/s13018-019-1347-y

Krause, W., Pope, M., Johnson, R., and Wilder, D. (1976). Mechanical Changes in the Knee after Meniscectomy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 58, 599–604. doi:10.2106/00004623-197658050-00003

Kurosawa, H., Fukubayashi, T., and Nakajima, H. (1980). Load-Bearing Mode of the Knee Joint. Clin. Orthopaedics Relat. Res. 149, 283–290. doi:10.1097/00003086-198006000-00039

Lee, W. Q., Gan, J. Z., and Lie, D. T. T. (2019). Save the Meniscus - Clinical Outcomes of Meniscectomy versus Meniscal Repair. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong) 27, 2309499019849813. doi:10.1177/2309499019849813

Lohmander, L. S., Englund, P. M., Dahl, L. L., and Roos, E. M. (2007). The Long-Term Consequence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Meniscus Injuries. Am. J. Sports Med. 35, 1756–1769. doi:10.1177/0363546507307396

Lubowitz, J. H., and Poehling, G. G. (2011). Save the Meniscus. Arthrosc. J. Arthroscopic Relat. Surg. 27, 301–302. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.12.006

Maher, S. A., Wang, H., Koff, M. F., Belkin, N., Potter, H. G., and Rodeo, S. A. (2017). Clinical Platform for Understanding the Relationship between Joint Contact Mechanics and Articular Cartilage Changes after Meniscal Surgery. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 600–611. doi:10.1002/jor.23365

Majewski, M., Susanne, H., and Klaus, S. (2006). Epidemiology of Athletic Knee Injuries: A 10-year Study. The Knee 13, 184–188. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005

Mccann, L., Ingham, E., Jin, Z., and Fisher, J. (2009). Influence of the Meniscus on Friction and Degradation of Cartilage in the Natural Knee Joint. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 17, 995–1000. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2009.02.012

Mcdermott, I. D., and Amis, A. A. (2006). The Consequences of Meniscectomy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. volume 88-B, 1549–1556. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.88b12.18140

Mcdermott, I. D., Masouros, S. D., and Amis, A. A. (2008). Biomechanics of the Menisci of the Knee. Curr. Orthopaedics 22, 193–201. doi:10.1016/j.cuor.2008.04.005

Mcdermott, I. (2011). Meniscal Tears, Repairs and Replacement: Their Relevance to Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Br. J. Sports Med. 45, 292–297. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.081257

Muthuri, S. G., Mcwilliams, D. F., Doherty, M., and Zhang, W. (2011). History of Knee Injuries and Knee Osteoarthritis: a Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 19, 1286–1293. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.07.015

Pereira, H., Caridade, S. G., Frias, A. M., Silva-Correia, J., Pereira, D. R., Cengiz, I. F., et al. (2014). Biomechanical and Cellular Segmental Characterization of Human Meniscus: Building the Basis for Tissue Engineering Therapies. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 22, 1271–1281. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.001

Proffen, B. L., Mcelfresh, M., Fleming, B. C., and Murray, M. M. (2012). A Comparative Anatomical Study of the Human Knee and Six Animal Species. The Knee 19, 493–499. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.005

Pujol, N., and Beaufils, P. (2019). Save the Meniscus Again!. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 27, 341–342. doi:10.1007/s00167-018-5325-4

Rai, M. F., Brophy, R. H., and Sandell, L. J. (2019). Osteoarthritis Following Meniscus and Ligament Injury: Insights from Translational Studies and Animal Models. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 31, 70–79. doi:10.1097/bor.0000000000000566

Ratcliffe, R. J., and Holt, K. G. (1997). Low Frequency Shock Absorption in Human Walking. Gait & Posture 5, 93–100. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(96)01077-6

Ridley, T. J., Mccarthy, M. A., Bollier, M. J., Wolf, B. R., and Amendola, A. (2017). Age Differences in the Prevalence of Isolated Medial and Lateral Meniscal Tears in Surgically Treated Patients. Iowa Orthop. J. 37, 91–94.

Roos, E. M., Roos, H. P., and Lohmander, L. S. (1999). WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index-additional Dimensions for Use in Subjects with post-traumatic Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 7, 216–221. doi:10.1053/joca.1998.0153

Roos, H., Lauren, M. r., Adalberth, T., Roos, E. M., Jonsson, K., and Lohmander, L. S. (1998). Knee Osteoarthritis after Meniscectomy: Prevalence of Radiographic Changes after Twenty-One Years, Compared with Matched Controls. Arthritis Rheum. 41, 687–693. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<687::aid-art16>3.0.co;2-2

Salata, M. J., Gibbs, A. E., and Sekiya, J. K. (2010). A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Meniscectomy. Am. J. Sports Med. 38, 1907–1916. doi:10.1177/0363546510370196

Sandmann, G. H., Adamczyk, C., Garcia, E. G., Doebele, S., Buettner, A., Milz, S., et al. (2013). Biomechanical Comparison of Menisci from Different Species and Artificial Constructs. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 14, 324. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-324

Schwer, J., Rahman, M. M., Stumpf, K., Rasche, V., Ignatius, A., Dürselen, L., et al. (2020). Degeneration Affects Three-Dimensional Strains in Human Menisci: In Situ MRI Acquisition Combined with Image Registration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 582055. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.582055

Seil, R., and Becker, R. (2016). Time for a Paradigm Change in Meniscal Repair: Save the Meniscus!. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 24, 1421–1423. doi:10.1007/s00167-016-4127-9

Seitz, A. M., and Dürselen, L. (2019). Biomechanical Considerations Are Crucial for the success of Tendon and Meniscus Allograft Integration-A Systematic Review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 27, 1708–1716. doi:10.1007/s00167-018-5185-y

Seitz, A. M., Galbusera, F., Krais, C., Ignatius, A., and Dürselen, L. (2013). Stress-relaxation Response of Human Menisci under Confined Compression Conditions. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 26, 68–80. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.05.027

Seitz, A. M., Lubomierski, A., Friemert, B., Ignatius, A., and Dürselen, L. (2012). Effect of Partial Meniscectomy at the Medial Posterior Horn on Tibiofemoral Contact Mechanics and Meniscal Hoop Strains in Human Knees. J. Orthop. Res. 30, 934–942. doi:10.1002/jor.22010

Seitz, A. M., Osthaus, F., Schwer, J., Warnecke, D., Faschingbauer, M., Sgroi, M., et al. (2021). Osteoarthritis-Related Degeneration Alters the Biomechanical Properties of Human Menisci before the Articular Cartilage. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 659989. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.659989

Simoni, L., Scarton, A., Macchi, C., Gori, F., Pasquini, G., and Pogliaghi, S. (2021). Quantitative and Qualitative Running Gait Analysis through an Innovative Video-Based Approach. Sensors 21, 1. doi:10.3390/s21092977

Snoeker, B. A. M., Bakker, E. W. P., Kegel, C. A. T., and Lucas, C. (2013). Risk Factors for Meniscal Tears: a Systematic Review Including Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 43, 352–367. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4295

Sukopp, M., Schall, F., Hacker, S. P., Ignatius, A., Dürselen, L., and Seitz, A. M. (2021). Influence of Menisci on Tibiofemoral Contact Mechanics in Human Knees: A Systematic Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 1. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.765596

Taylor, W. R., Ehrig, R. M., Heller, M. O., Schell, H., Seebeck, P., and Duda, G. N. (2006). Tibio-femoral Joint Contact Forces in Sheep. J. Biomech. 39, 791–798. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.006

Temple, D. K., Cederlund, A. A., Lawless, B. M., Aspden, R. M., and Espino, D. M. (2016). Viscoelastic Properties of Human and Bovine Articular Cartilage: a Comparison of Frequency-dependent Trends. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 17, 419. doi:10.1186/s12891-016-1279-1

Thomas, A. C., Hubbard-Turner, T., Wikstrom, E. A., and Palmieri-Smith, R. M. (2017). Epidemiology of Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis. J. Athl Train. 52, 491–496. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.5.08

Tibesku, C. O., Mastrokalos, D. S., Jagodzinski, M., and Pässler, H. H. (2004). [MRI Evaluation of Meniscal Movement and Deformation In Vivo under Load Bearing Condition]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 18, 68–75. doi:10.1055/s-2004-813001

Voloshin, A. S., and Wosk, J. (1983). Shock Absorption of Meniscectomized and Painful Knees: a Comparative In Vivo Study. J. Biomed. Eng. 5, 157–161. doi:10.1016/0141-5425(83)90036-5

Wachsmuth, L., Keiffer, R., Juretschke, H.-P., Raiss, R. X., Kimmig, N., and Lindhorst, E. (2003). In Vivo contrast-enhanced Micro MR-Imaging of Experimental Osteoarthritis in the Rabbit Knee Joint at 7.1T11This Work Is Supported by BMBF, Leitprojekt Osteoarthrose. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 11, 891–902. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2003.08.008

Weigel, D. P., and Marsh, J. L. (2002). High-energy Fractures of the Tibial Plateau. The J. Bone Jt. Surgery-American Volume 84, 1541–1551. doi:10.2106/00004623-200209000-00006

Winter, D. A. (1983). Energy Generation and Absorption at the Ankle and Knee during Fast, Natural, and Slow Cadences. Clin. Orthopaedics Relat. Res. 175, 147–154. doi:10.1097/00003086-198305000-00021

Yeh, P. C., Starkey, C., Lombardo, S., Vitti, G., and Kharrazi, F. D. (2012). Epidemiology of Isolated Meniscal Injury and its Effect on Performance in Athletes from the National Basketball Association. Am. J. Sports Med. 40, 589–594. doi:10.1177/0363546511428601

Zaffagnini, S., Di Paolo, S., Stefanelli, F., Dal Fabbro, G., Macchiarola, L., Lucidi, G. A., et al. (2019). The Biomechanical Role of Meniscal Allograft Transplantation and Preliminary In-Vivo Kinematic Evaluation. J. Exp. Ortop 6, 27. doi:10.1186/s40634-019-0196-2

Zaffagnini, S., Grassi, A., Marcheggiani Muccioli, G. M., Benzi, A., Serra, M., Rotini, M., et al. (2016). Survivorship and Clinical Outcomes of 147 Consecutive Isolated or Combined Arthroscopic Bone Plug Free Meniscal Allograft Transplantation. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 24, 1432–1439. doi:10.1007/s00167-016-4035-z

Keywords: knee, joint, meniscus, shock absorber, shock, impact, dynamic mechanic analysis (DMA), in vitro

Citation: Seitz AM, Schwer J, de Roy L, Warnecke D, Ignatius A and Dürselen L (2022) Knee Joint Menisci Are Shock Absorbers: A Biomechanical In-Vitro Study on Porcine Stifle Joints. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10:837554. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.837554

Received: 16 December 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 17 March 2022.

Edited by:

Tarun Goswami, Wright State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rene Verdonk, Ghent University, BelgiumMatteo Berni, Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute (IRCCS), Italy

Copyright © 2022 Seitz, Schwer, de Roy, Warnecke, Ignatius and Dürselen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreas M. Seitz, YW5kcmVhcy5zZWl0ekB1bmktdWxtLmRl

Andreas M. Seitz

Andreas M. Seitz Jonas Schwer

Jonas Schwer Luisa de Roy

Luisa de Roy Daniela Warnecke

Daniela Warnecke Anita Ignatius

Anita Ignatius Lutz Dürselen

Lutz Dürselen