- 1College of Food and Biology Engineering, Jimei University, Xiamen, China

- 2Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

With the advancement of science, technology, and productivity, the rapid development of industrial production, transportation, and the exploitation of fossil fuels has gradually led to the accumulation of greenhouse gases and deterioration of global warming. Carbon neutrality is a balance between absorption and emissions achieved by minimizing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from human social productive activity through a series of initiatives, including energy substitution and energy efficiency improvement. Then CO2 was offset through forest carbon sequestration and captured at last. Therefore, efficiently reducing CO2 emissions and enhancing CO2 capture are a matter of great urgency. Because many species have the natural CO2 capture properties, more and more scientists focus their attention on developing the biological carbon sequestration technique and further combine with synthetic biotechnology and electricity. In this article, the advances of the synthetic biotechnology method for the most promising organisms were reviewed, such as cyanobacteria, Escherichia coli, and yeast, in which the metabolic pathways were reconstructed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 capture and product synthesis. Furthermore, the electrically driven microbial and enzyme engineering processes are also summarized, in which the critical role and principle of electricity in the process of CO2 capture are canvassed. This review provides detailed summary and analysis of CO2 capture through synthetic biotechnology, which also pave the way for implementing electrically driven combined strategies.

Introduction

With the advancement of science, technology, and productivity, the rapid development of industrial production, transportation, and the exploitation of fossil fuels has gradually led to the accumulation of greenhouse gases and deterioration of global warming (Fang et al., 2021). Global CO2 emissions have increased by 30.7% after humankind entered the 21st century. Supported by investigation report, if the carbon is still growing at such a high rate, the global concentration of CO2 will reach up to 5*10^−4 μl/L by 2050, leading to the extinction of 24% of animals and plants on the Earth (Pacala and Socolow, 2018; Johnson et al., 2021). It also has attracted the attention of countries worldwide that put goals of energy conservation, emission reduction, and carbon neutrality on the agenda (Zou et al., 2021). Carbon neutrality is a balance between absorptions and emissions achieved by minimizing CO2 emissions from human social productive activity through a series of initiatives, including energy substitution and energy efficiency improvement. Then CO2 was offset through forest carbon sequestration and captured at last (He et al., 2021). At present, the routes of chemistry (Kourosh et al., 2020), electrochemistry (Li FH et al., 2020), photoelectric catalysis (Wang and Song, 2020), enzyme (Yang et al., 2020), and microbial carbon fixation (Hu et al., 2019) are widely studied. Compared with the chemical route, the biological route, which does not require high temperature and pressure, is a more environmentally friendly process.

CO2 has played a vital role in the origin of life (Zhang et al., 2020), in which many species could fix as a carbon resource and flow into the metabolic pathways (Cheah et al., 2016). The central CO2-involved pathways are the Calvin cycle, reducing citric acid cycle, Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, 3-hydroxypropionic acid cycle, 3-hydroxypropionic acid/4-hydroxybutyric acid cycle, and the dicarboxylic acid/4-hydroxybutyric acid cycle (Aresta et al., 2016). These cycles have maintained the global carbon balance between absorptions and emissions in the past billions of years. However, with the economic development and environmental changes, the CO2 emission rate has far outstripped the traditional carbon fixation, and the balance was broken, which also declares the urgency to explore effective means to reduce CO2. Enzymes play an essential role in the microbial carbon fixation process, which also exert considerable influence on the CO2 fixation pathways; for example, the irreplaceable role of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) (Bhat et al., 2017) and formate dehydrogenase (Kumar et al., 2017) in the Calvin cycle (Figure 1) and the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, respectively. Thus, the key enzymes and metabolic pathways involved in the existing CO2 metabolic pathways provide essential references for developing and enhancing enzymatic conversion and microbial fixation of CO2 (Jiang et al., 2021; Nisar et al., 2021; Tan and Ng, 2021).

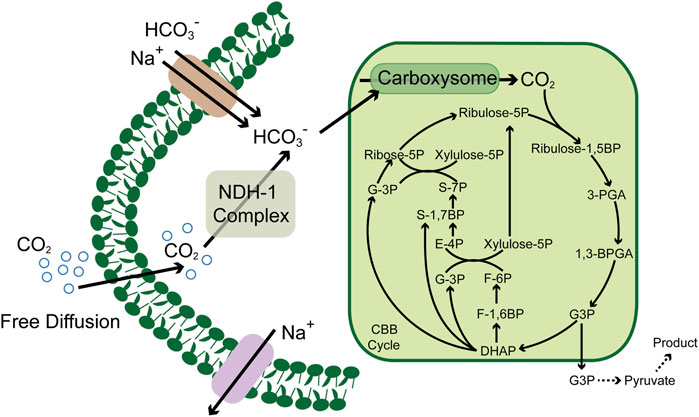

FIGURE 1. Schematic of the carbon concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. CBB cycle, Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle; ribulose-1, 5BP, ribulose-1, 5 diphosphate; ribulose-5P, ribulose-5 phosphate; ribose-5P, ribose-5 phosphate; 3PGA, glycerate 3-phosphate; 1, 3BPGA, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F-1, 6BP, fructose-1, 6 diphosphate; F-6P, fructose-6 phosphate; xylulose-5P, xylulose-5 phosphate; S-7P, sedoheptulose-7 phosphate; S-1,7BP, sedoheptulose-7 diphosphate; and E-4P, erythrose-4 phosphate.

In recent years, initial success has been achieved in the key enzymes’ structural design and modification, cofactor engineering, and metabolic engineering to improve efficiency (Chida et al., 2007; Fast and Papoutsakis, 2018). Moreover, advances and innovations of synthetic biotechnology and electrically driven microbial processes have given a new impetus for carbon neutrality.

In this study, we have introduced the natural and artificially modified microbial CO2 fixation progresses through synthetic biotechnology, in which CO2 was used as the carbon source for growth and product synthesis. And then, we also discussed the electrically driven enzymatic and non-autotrophic microbial CO2 fixation process, including mechanism, method, and important progress. Finally, based on full insights into the advantages and disadvantages of synthetic biotechnology and electrochemistry, we prospected the tendency development in the scope of the combination of synthetic biotechnology and electrochemistry, which is expected to provide a new solution for the efficient utilization of CO2 to generate high value–added chemicals.

Synthetic Biotechnology for Carbon Neutrality

Carbon Dioxide Fixation Through Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are a kind of immemorial autotrophic prokaryotic organism with records from over 1 billion year ago, which makes a system to convert the CO2 to glucose, produce O2 from H2O, and create a favorable atmospheric environment for the formation of the wide range of living organisms. Cyanobacteria can synthesize various kinds of natural compounds from CO2 and energy absorbed from sunlight, for example, amino acids, pigment, and fatty acids (Lau et al., 2015). Compared with plants, the fast-growing and efficient CO2 conversion bacteria, cyanobacteria, have taken the duty of CO2 capture on its shoulder since ancient times. They also hold promise of being a gifted chassis for a cell factory of chemicals modified through synthetic biotechnology toolboxes. However, compared with model organisms of E. coli and yeast, the limitation of genetic manipulation of cyanobacteria cannot be ignored. Various significant efforts have developed an utterly robust set of synthetic biotechnology toolboxes and modularly recombined parts. These tools include available promoters (Behle et al., 2020; Sengupta et al., 2020), ribosome-binding sites, vector systems, and the CRISPR-Cas system, which are also reviewed comprehensively by Sun et al. (2018); Santos-Merino et al. (2019); Pattharaprachayakul et al. (2020); Santos-Merino et al. (2021). Beyond that, recombinant protein stability was also another crucial factor that decided the outcome of the heterologous expression. The recombinant proteins derived from eukaryotic plants and animals are unstable when freely expressed in the cyanobacterial cytosol but stable when fused with a highly expressed cyanobacterial native or heterologous protein, which was demonstrated by expressing the recombinant proteins of the plant origin isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway, human interferon protein, and tetanus toxin fragment C (Zhang X et al., 2021). These fundamental research studies pave the way to construct a robust engineered cyanobacterial cell factory for the large-scale commercial production from CO2.

Based on these pioneering works, many researchers focus on shaping a versatile producer from cyanobacteria. Compared to various heterotrophic model organisms, the relatively lower growth and metabolic rate were the barriers that hindered the development of cyanobacteria from the source, which derived from a lower CO2 fixation rate. However, compared to many other autotrophic organisms, cyanobacteria have a highly efficient CO2 enrichment system, which enables them to survive the water environment with low concentrations of CO2. In this system, the NDH-1/NDH-1MSs complex converts the CO2 diffused freely into a cell to HCO3-, which is further converted to CO2 by carbonic anhydrase in carboxysome and provided to RuBisCO as substrate (Angermayr et al., 2015, Figure 1). This unique mechanism guaranteed the CO2 concentration gradient between the intracellular and extracellular environments. Thus, recent efforts have focused on expanding the wavelength range of the absorbable solar spectrum and increasing electron transport chain activity to increase photosynthetic efficiency. Researchers introduced the chlorophyll f (Chlf)–encoding genes into Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 absorbs far-red light of wavelengths over 700 nm (Ho et al., 2016). After integrating Chlf into PSI complexes, the active radiation for the new PSI complex was expanded up to 750 nm, which extended the wavelength ranges and provided light compensation under non-saturating light conditions (Tros et al., 2020).

Meanwhile, overexpression enzymes related to the Calvin cycle can improve photosynthesis and product formation, which have been shown in several research reports (De Porcellinis et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2018). It was also demonstrated in Synechocystis PCC 6803, where extra bicarbonate transporter expression led to a 2-fold enhancement of the growth rate and a higher amount of biomass accumulation (Kamennaya et al., 2015). Likewise, the overexpression of the carbon transporters BicA and SbtA involved in central carbon metabolism enhances biomass production by 50–100% (Gupta et al., 2020). Beyond that, Włodarczyk and his colleague (Włodarczyk et al., 2020) have discovered and characterized a new cyanobacterial strain, Synechococcus sp. PCC 11901, which possesses a shorter doubling time (2 h) and higher biomass production. By engineering this strain, they demonstrated that this promising cyanobacterium was easy to modify and produced free fatty acids with a concentration over 6 mM (1.5 g/L). Ungerer et al. (Ungerer et al., 2018) further identified three specific genes, atpA, ppnK, and rpaA, with SNPs from the fastest growing cyanobacterium, in which atpA and ppnK express an ATP synthase and NAD+ kinase with higher performance, resulting in the decrease in the doubling time from 6.8 to 2.3 h. After point mutation in the α subunit of FoF1 ATP synthase (AtpA), they enhanced the environmental stress tolerance of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, leading to an increase in AtpA protein levels, intracellular ATP synthase activity, and ATP concentrations (Lou et al., 2018).

Many scholars devote themselves to exploring cyanobacteria as a multifunctional platform for a biotechnological process by far. By the introduction of the exogenous glycerol biosynthetic pathway, researchers build a bridge from the CO2 fixation to glycerol production, which serves as the substrate for the C3 platform chemicals (Wang et al., 2015). Using it as a base, scientists synthesized a variety of chemicals from CO2, including 3-hydroxypropionic acid (Wang et al., 2016), isobutanol (Miao et al., 2017), limonene (Lin et al., 2017), and 2,3-butanediol (Nozzi et al., 2017). Beyond that, by introducing a more complicated pathway, costly compounds of polysaccharide terpene (Bhunia et al., 2018) and fatty acid ethyl esters were also produced from these engineered cell factories. By expressing the genes coding for sucrose-phosphate synthase, sucrose-phosphate phosphatase, and sucrose-degrading invertase, sucrose was synthesized and accumulated successfully (Kirsch et al., 2018; Vayenos et al., 2020.). By overexpressing ribDGEABHT (riboflavin-encoding genes) and introducing an internal promoter to the upstream of the heterologous ribAB gene, the production of riboflavin increased by 211-fold (73.9 ± 7.2 μM) compared to the wild-type strain (Kachel and Mack, 2020).

However, the growth and production processes based on photoautotrophic are limited to the time of sunlight available because growth and synthesis were slowed down and ceased in an unlighted environment. In addition, economic feasibility in the application of cyanobacterium as a versatile producer also relies partially on their photosynthetic capacity and solar energy conversion efficiency. The imbalances between absorbed light energy (source) and the metabolic capacity (sink) can potentially increase the carbon flux output from the Calvin cycle, which may be beneficial for increasing the photosynthesis efficiency (Santos-Merino et al., 2021). Many genetic manipulation tools and strategies (Sun et al., 2018) have been developed to translate to significant gains for cyanobacteria as a cell factory to synthesize commercial products from CO2. At the same time, it is still a heavy responsibility and a long way from the goal for carbon neutrality with higher efficiency.

Carbon Dioxide Fixation Through Escherichia coli

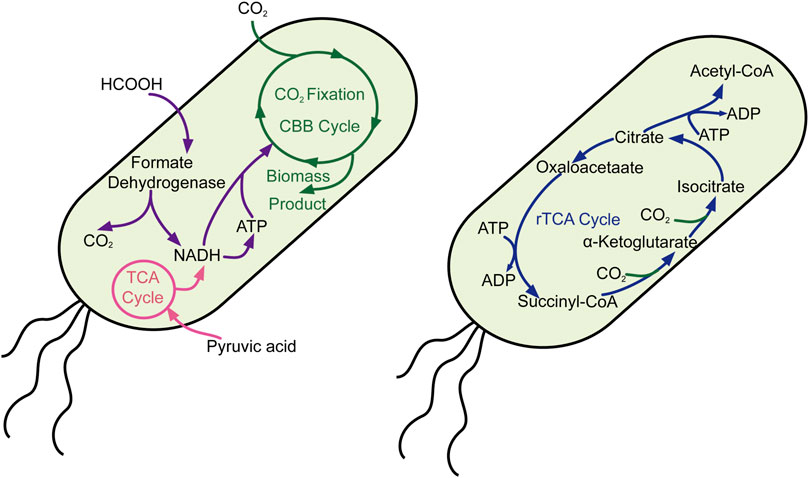

Unlike cyanobacteria, Escherichia coli is a normal chassis cell for most scientists who possess complete and efficient genetic manipulation tools. Thus, many scientists have devoted themselves to introducing the CO2-fixed pathway into E. coli, including the Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle and the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle. Milo’s group reported significant work that E. coli synthesized sugar from CO2 by introducing the non-native Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle pathway (Figure 2), rewiring the metabolic pathway and directed laboratory evolution, while oxidization of pyruvate provided the reducing power and energy (Antonovsky et al., 2016). Moreover, they also constructed another engineered E. coli that use CO2 as their sole carbon source through metabolic rewiring and directed evolution, in which formate is oxidized to provide reducing power and energy (Gleizer et al., 2019). Lee and his colleague also heterogeneously expressed the whole gene clusters (cbbI and cbbII operons) belonging to the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) pathway in E. coli, which was combined with the yeast fermentation process to mitigate exogenous CO2. These milestone works provide feasible solutions in changing model heterotrophic organisms to autotrophy one and offer potential possibilities for resource sustainability.

FIGURE 2. Carbon fixation in E. coli through the CBB and rTCA cycles. CBB cycle, Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle; rTCA cycle, reverse citric acid cycle.

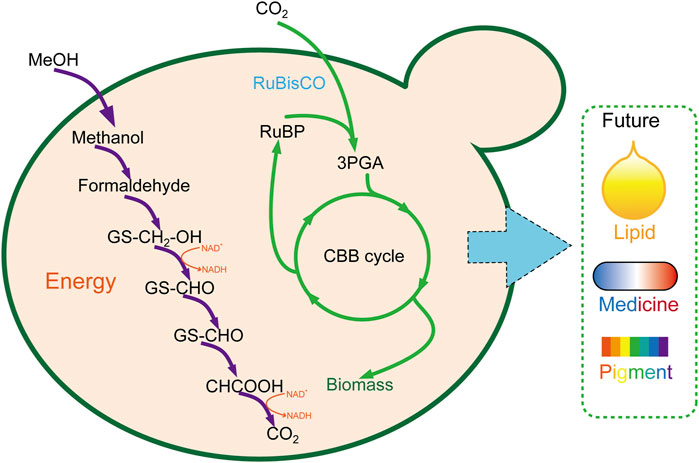

Except for the CBB pathway, the scientist also reconstructed another C1 assimilation pathway to convert the nutritional types of E. coli for integrated utilization of CO2 and C1 chemical compounds. By employing the technique of rational design, metabolic pathway reconstruction, and metabolic flux rebalance, scientists achieve success in converting the E. coli to an engineered methylotrophic bacterium, which utilize methanol as a sole carbon source for growth with a doubling time of 8 h (Chen CH et al., 2020). By reconstructing the tetrahydrofolate cycle and the reverse glycine cleavage pathway and introducing formate dehydrogenase, the formate and CO2 could serve as carbon sources for engineered E. coli–sustaining growth (Bang and Lee, 2018). The combined reconstructed reductive glycine pathway and short-term evolution, Kim and his colleague also constructed an engineered E. coli by taking formate and CO2 as carbon sources, whose doubling time was less than 8 h. By introducing methanol dehydrogenase to the evolved strain, they also converted the engineered E. coli to a methylotrophic bacterium that could grow on methanol and CO2 (Kim et al., 2020).

Until now, it is hard to achieve the purpose of efficiency CO2 fixation from the liquid culture medium environment to produce chemical with high productivity, so reutilized CO2 from the endogenic pathway was particularly significant to reduce carbon emission in large-scale industrial production. By introducing the gene of kor (express α-ketoglutarate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase), acl (express ATP-dependent citrate lyase), frd (express fumarate reductase), and energy pump, the engineered E. coli successfully recycled CO2, in which the C-2/C-1 ratio increased to 1.79 ± 0.02 (Chen FYH et al., 2020). Beyond that, the scientists also introduced 20 genes related to the CO2-concentrating mechanism into E. coli to enhance the capture rate of CO2, which achieved success in fixing CO2 from ambient air into biomass (Flamholz et al., 2020). This work would let us not only understand the CO2-concentrating mechanism but also lay the groundwork for CO2 fixation in diverse organisms.

The research on E. coli that uses CO2 to produce high value–added products has achieved preliminary success. However, in contrast to cyanobacteria, E. coli is still growing slowly in autotrophic culture conditions. Therefore, to realize industrial-scale production, a large amount of work was still required to enhance CO2 fixation and utilization efficiency of engineered E. coli, which could also pave the way for the high value–added product.

Carbon Dioxide Fixation Through Yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a versatile chassis cell which is widely used as a cell factory of natural compounds, especially for the industrial production of bioethanol. However, the anaerobic fermentation process constrains ethanol concentration and trigger the accumulation of by-product (glycerol), which is caused by the redox-cofactor unbalancing, Guadalupe-Medina select CO2 as an electron acceptor, which not only balances excess reduced cofactor (NADH) but also captures the CO2 and reduces greenhouse gas emissions (Guadalupe-Medina et al., 2013). They reconstruct a new pathway to introduce phosphoribulokinase (PRK) and form-II ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (Rubisco), leading to a result with lower (90% reduction) by-product and higher (10% increase) ethanol production. On this basis, Xia et al. studied the heterologous expression of the xylose reductase (XR)/xylitol dehydrogenase (XDH) and xylose isomerase, which converts xylose to xylulose (Xia et al., 2016). By introducing PRK and Rubisco and upregulating the native pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), they successfully achieved bioethanol production from cellulosic hydrolysates with CO2 recycling. Joeline Xiberras et al. introduce the “SA module” (malate dehydrogenase, fumarase, and fumarase) to S. cerevisiae for succinic acid production from glycerol and CO2 (Xiberras et al., 2020). These studies provide a feasible idea to fix CO2 and form other chemical compounds.

Unlike capturing CO2 to form chemical compounds through the reconstructed intracellular pathway, a biologically catalyzed CO2 mineralization process was another simple approach. Roberto Barbero et al. displayed bovine carbonic anhydrase II on the yeast’s surface, which has higher thermal stability and mineralized CO2 with coal fly ash to form CaCO3. Coupled with model prediction, they demonstrated that this biological mineralization process is ∼10% more cost-effective when captured per ton of CO2 (Barbero et al., 2013). Shen et al. treated the discarded yeast with potassium hydroxide and form microporous carbon materials with a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area of 1,348 m2g−1 and a pore volume of 0.67 cm3g-1, which resulted in a superior performance for CO2 capture (Shen et al., 2012).

As eukaryotic chassis cells, yeast is more complicated and suitable for natural product synthesis than E. coli. Abundant genetic manipulation makes it more feasible to utilize CO2 to the product of high value–added long-chain compounds (Figure 3). However, as same as E. coli, a large amount of work was still required to enhance the CO2 fixation and utilization efficiency before being applied for large-scale industrial manufacture.

FIGURE 3. Carbon fixation in P. pastoris through the CBB cycle. 3PGA, glycerate 3-phosphate; CBB cycle, Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle.

Electrically Driven Carbon Neutrality

Electron Transfer Mechanisms

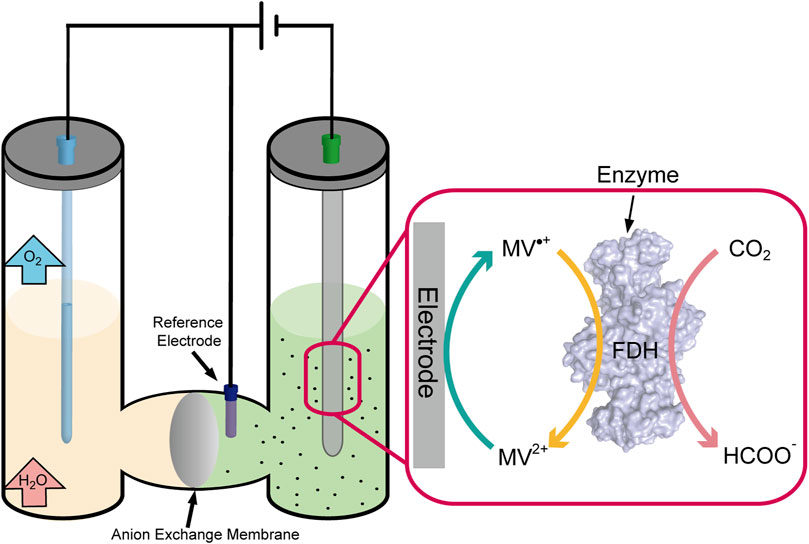

Enzyme catalytic CO2 fixation involves a redox reaction, in which electron transfers were performed by the cofactor of NAD(P)/NAD(P)H. However, the electrical process could realize the regeneration of electron acceptors and donors (cofactor) happened in electrodes to maintain the continuity of the reaction (Chen H et al., 2020). The electron across enzyme (e.g., cytochrome c and ferredoxin) can transfer directly from the electrode to the substrate when the enzyme’s active site is well exposed (Silveira and Almedia, 2013). Although many successes have been achieved in adsorption enzymes on the surface of the electrode, this process was unstable and not feasible in most situations that limit the movement process of the enzyme. However, the electron transfers mediately utilizing carriers (e.g., viologens, quinones, and dyes) shuttle out from the active site to the electrode surface, in which the active site resides deep inside the enzyme (Yuan et al., 2019). That seems more reasonable and practical in non-contact communications between enzymes and electrons, and the drawback is the toxicity from redox mediators (Figure 4).

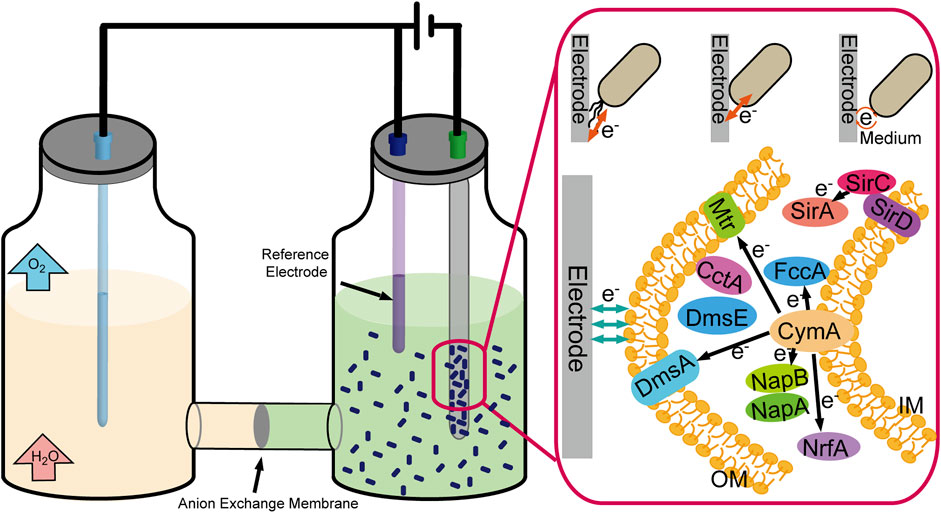

Some microbial cells can also replace enzymes to realize electron transfer with the electrode, such as Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens. There have been three significant mechanisms for electron transfer between the electrode and microbial cells (Figure 5). First, perform electron transfer by contacting the electrode immediately through c-type cytochromes located in the cell’s outer membrane; second, perform electron transfer through redox mediators to communicate with the electrode; and third, perform long-range electron transfer through pili (Pankratova et al., 2019). Compared with enzymes, the microbial cells possess the characteristics of high stability and self-duplicating and do not require purification belonging to the enzyme preparation process. Meanwhile, the weakness of lack of specificity and the slower electron transfer rate must not be neglected.

FIGURE 5. Schematic representation of the CO2 fixation process by electrically driven microorganism.

CO2 Fixation by Electrically Driven Enzyme

CO2 Reduction to C1–C2 Chemical

CO2 fixation through enzymes was also lucubrated, which was generally performed through hydrogenation reduction and required an expensive cofactor of NADH/NADPH. Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) has been widely used in coenzyme regeneration, which catalyzes nearly irreversible formate oxidation to CO2 and provides NADH for the other coupling reaction. Metal-dependent FDH mainly catalyzed CO2 fixation to produce formate, using NAD+ as a cofactor. However, Jayathilake et al. developed a novel approach for CO2 reduction catalyzed by metal-independent FDH with methyl viologen radical cation (MV•+) as the cofactor, which efficiently regenerated at a carbon electrode through electrochemical reduction without any additional reducing agent (Figure 4). Formate yields as high as 97 ± 1% at 20 mV negative to the reversible electrode potential, much lower than that of metal catalysts (−800 mV to −1,000 mV) (Jayathilake et al., 2019). By embedding the enzymes into the metal–organic framework ZIF-8, Rh complex–grafted electrode was used to regenerate NADH and significantly enhanced the catalytic enzyme rate by 12-fold from CO2 to methanol compared to the free enzyme statue (Zhang Z et al., 2021). The enzyme catalytic CO2 fixation combined with electrochemical regeneration of natural/artificial cofactor provides a new idea for efficient CO2 fixation to small-molecule compounds.

CO2 Reduction to Higher Value–Added Products

Beyond that, the electrically driven enzyme also catalyzed CO2 to produce higher value–added products. Two cooperating enzymes in nanopores performed carboxylation by introducing CO2 to pyruvate (C3) and producing malate (C4), in which indispensable NADH was regenerated and driven by electricity (Morello et al., 2019). A bio-electrocatalytic system was also developed to drive carboxylation by incorporating CO2 into crotonyl-CoA, ferredoxin NADP+ reductase (FNR), and NADPH-dependent crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase were co-immobilized in a viologen-based redox hydrogel. The faradaic efficiency was 92 ± 6% at a rate of 1.6 ± 0.4 μmol cm−2 h−1 (Castañeda-Losada et al., 2021). Thus, combined with the electrical method, the enzyme could be used for higher value–added products synthesis with high efficiency.

CO2 Fixation by the Electrically Driven Microorganism

On the one hand, enzyme catalytic CO2 fixation result in high activity and selectivity, and on the other hand, the expensive protein purified process was also non-negligible. So, some scientists have devoted themselves to developing an electrically driven whole-cell catalytic process. Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 perform CO2 fixation to synthesize formate driven by the electrical method with product concentrations up to 60 mM. Compared to the electrically driven enzyme catalytic process, the whole-cell electro-biocatalytic process is undismayed by being exposed to oxygen gas without providing extra cofactors (Hwang et al., 2015). Employing neutral red as a redox mediator coated outside the carbon felt (CF) electrode, Seelajaroen et al. performed a long-term (17 weeks) electrical reduction of CO2 to formate based on M. extorquens (Seelajaroen et al., 2019). Beyond that, the bioelectrochemical system also harvests success in producing acetate, methane, butyrate, and polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB). Thus, CO2 fixation by electrically driven microorganisms is a process that converts renewable electrical energy to chemicals, which is a novel and attractive strategy for energy transformation and storage.

CO2 Fixation Efficiency Between Electrically Driven CO2 Fixation and Bio-Carbon Fixation

It is hard to compare the CO2 fixation efficiency and rate between electrochemistry and bio-carbon fixation processes at “fair” levels because electric energy is converted from solar, wind, and chemical energy. However, we could also get some information and answers from interesting data. After the pioneer’s work, the heterotrophic microorganism (E. coli) was engineered to grow on methanol/formic acid and CO2, and the doubling time was decreased from ∼70 to ∼8 h. By contrast, the doubling time of Synechococcus sp. PCC 11901 (photosynthetic autotrophs), E. coli (chemoheterotrophy), and Vibrio natriegens (chemoheterotrophy) is 6–2 h (Włodarczyk et al., 2020), 27.23 min (Weinstock et al., 2016), and 15.61 min (Weinstock et al., 2016). Thus, there is a significant untapped opportunity for engineered microorganisms to synthesize products from CO2 with acceptable efficiency. In chemical synthesis, the electro-biocatalytic process produces 60 mM formate from CO2 in 60 h (1 mM/h) (Hwang et al., 2015) and 14.8 mM malate from pyruvate and CO2 in 24 h (0.62 mM/h) (Morello et al., 2019). Furthermore, CO2 was converted to starch at last with a rate ∼8.5-fold higher than starch synthesis in maize, in which electrically driven CO2 fixation was combined with the cell-free enzymatic catalytic process. Although electrically driven techniques have gained a temporary lead in efficiency, obstacles from large-scale industrialized production still stared them in the face.

Combined Synthetic Biotechnology With Electrochemistry for Carbon Neutrality

By rewiring the metabolic pathway and introducing an exogenous gene module, the electroactive microbial cells can expand their product scope and electro-biocatalysis efficiency. However, there are a finite number of electroactivity microorganisms, and their gene modification platform was limited compared with the model organism. Moreover, the application of these electro-biocatalysts still faces much obstacles, for example, 1) the effect of the electrical environment on the formation of biofilms, 2) limited toolbox for genetic manipulation, and 3) low extracellular electron transfer rate. So, we take S. oneidensis as a representative, which has been studied maturely and in-depth relatively.

Facilitate Biofilm Formation

Electroactive microbial form biofilm on the electrode surface was the foundation in bioelectrochemical systems’ normal running process. In the pioneer’s work, many genes were identified, which are crucial for the biofilm formation, such as dgcS, cheY3, exeM, and bolA gene. DgcS, a major diguanylate cyclase (DGC), catalyzed GTP to form cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP), which acts as a second messenger to regulate biofilm formation (Matsumoto et al., 2021). At the same time, phosphorylated CheY3 was also observed to interact with DGCs and co-regulate the biofilm formation (Boyeldieu et al., 2020). ExeM, an extracellular nuclease, was also identified as a crucial enzyme for the normal biofilm formation, activated by the metal cofactors (Ca2+ and Mg2+/Mn2+) (Binnenkade et al., 2018). The scientist also found that overexpression of the bolA gene, a transcriptional regulator, facilitates biofilm formation by regulating many related gene express processes (Silva et al., 2020). Beyond that, low concentrations of extracellular riboflavin resulted in an upregulation transcription of the ornithine decarboxylase–encoding gene speC, which facilitates the biofilm formation of S. oneidensis (Silva et al., 2020). So, except electrode surface modification, genetic manipulation can also regulate biofilm formation in a sample and stable method.

Construct Genetic Manipulation Platform

Genetic manipulation platform development, especially non-model organism, not only removes gene editing restrictions but also broaden the product type. Fortunately, the developed synthetic biotechnology of the CRISPR-related toolset provides new possibilities for reprogramming the gene module in electroactive microorganisms. By fusing Cas9 nickase (Cas9n (D10A)) with cytidine deaminase (rAPOBEC1), Cheng et al. successfully developed the pCBEso system in S. oneidensis, whose double-locus simultaneous editing efficiency reached up to 87.5%. Compared with others, this system did not require double-strand break or repair templates and was successfully used for broadening carbon source utilization spectra for S. oneidensis (Cheng L et al., 2020). The developed CRISPR-ddAsCpf1 system achieved 100% gene repression reported by green fluorescent protein (GFP). By repressing the gene related to extracellular electron transfer, they realized the enhancement of l-lactate metabolism–related genes expression and riboflavin production, resulting in rediverting electron flux (Li et al., 2020). Ng’s group also applied CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) targeted to the genes and redirection carbon flux of S. oneidensis, combined with integrating gene cluster coding the glucokinase, GroELS chaperone, and ALA synthase under dual T7 promoters, targeted product (5-aminolevulinic acid) improved by 145-fold (Yi and Ng, 2021). Yang’s group successfully explored a way to produce n-butanol (160 mg/L) through engineered S. oneidensis MR-1. The gene modules encoding alcohol dehydrogenase, CoA transferases, and acetyl-CoA synthetase were integrated into the plasmid and worked in the bacteria (Jeon et al., 2018). These genetic manipulation platforms constructed would accelerate the robust construction of engineered strain with superior performance electrically driven carbon neutrality.

Accelerate Electron Transfer Rate

Synthetic biotechnology can also be employed to modify and reconstitute the related pathways and regulation strategies to enhance extracellular electron transfer (EET) efficiency. The scientist developed a population-state decision system based on quorum sensing to allocate cellular resources, which change the predominant metabolic flux from growth to EET in the latter, resulting in EET enhancement up to 4.8-fold (Li et al., 2020). Dundas et al. designed a series transcriptional logic gate to regulate and control the EET flux in S. oneidensis, in which the EET pathway–related parts of CymA/MtrCAB were systematically modified (Dundas et al., 2018). These works provide novel and powerful methods to control and regulate the EET, which lay the foundation for developing an intelligently and effectively synthetic biotechnology tool.

The cytochrome c network is a crucial module that bridges the electron transfer between intracellular and extracellular environments, including c-Cyts CymA, bc1 complex, TorC, and SirD (Figure 5). Sun et al. constructed engineered S. oneidensis whose NapB, FccA, and TsdB were depleted, and CctA was overproduced, resulting in higher power density in MFCs (436.5 mW/m2, 3.62-fold than that of wild type) (Sun et al., 2021). At the same time, soluble c-type cytochromes (c-Cyts) also enhance the extracellular electron shuttling under electron acceptor–limited conditions (Liu et al., 2020). The scientists also attempted to enhance the electron transfer by focusing on another crucial factor-cAMP, for cAMP-cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate receptor protein (CRP) regulates the multiple EET-related pathways (Vellingiri et al., 2019). Scientists constructed a cyaC-OE mutant that expresses higher intracellular cAMP concentration, five times higher than that in the wild-type strain, resulting in a two-fold higher current than the wild-type strain (Kasai et al., 2019). Cheng et al. expressed exogenous adenylate cyclase encoding gene from the Beggiatoa sp. in S. oneidensis MR-1, enhancing EET capacities (Cheng ZH et al., 2020).

Conclusion and Perspective

On the one hand, CO2 emitted from fossil fuels and the productive human activity was the main factor for extreme climate change and global warming. On the other hand, CO2 is also a carbon source, catalyzing more valuable products. Cyanobacteria are a natural microorganism that can spontaneously convert CO2 to many chemicals. At the same time, synthetic biotechnology was also employed to construct engineered bacteria by introducing the heterogeneous CO2 fixation–related gene for carbon neutrality. Computational analysis was also another powerful tool to identify and design pathways with a more favorable thermodynamic driving force for CO2 fixation (Satanowski et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2021). Beyond that, electrically driven microbial and enzyme engineering was also suitable for CO2 fixation with high efficiency. Thus, combined synthetic biotechnology with electrochemistry possesses the full advantage of both for carbon neutrality, which can not only broaden the product scope but also harvest high energy conversion efficiency.

Whether inartificial CO2 autotrophic organism or a heterotrophic model organism, synthetic biotechnology tools play a crucial role in editing genes, rediverting metabolic pathways, endowing them with new functions, optimal enforcement efficiency, and most abundant resources. Based on this, scientists carried out milestone work that converts the heterotrophic organism of E. coli (Figure 2) (Antonovsky et al., 2016; Gleizer et al., 2019; Bang et al., 2020) and P. pastoris to autotroph and growth on CO2 (Figure 3) (Gassler et al., 2020). These great works will pave the way for the CO2 fixation through microorganisms and the great dream of carbon neutrality. However, the CO2 fixation rate was slow and insufficient to satisfy the conversion of CO2 to the chemical product with high efficiency. Thus, electrochemical combined with synthetic biotechnology spawned a new revolution for CO2 fixation efficiency. By developing a chemoenzymatic system, CO2 was first fixed through electrochemical to form methanol, coupling with multi-step enzymatic reaction, CO2 was converted to starch at last with a rate ∼8.5-fold higher than starch synthesis in maize (Cai et al., 2021). This is a typical case in fuse electrochemical synthetic biotechnology involvement, which gives attention to both efficiency and product quality. Beyond that, the success of the cell-free model is also pinning its hopes on enzymes (such as formate dehydrogenase and carboxylase), whose design and engineering can also accelerate the rate of CO2 fixation. Thus, some novel analytical (Zhuang et al., 2021) methods and research tools (Zhuang et al., 2020) can also show extraordinary talents in illuminating the enzyme’s catalytic mechanism.

Besides, it is also an important and promising field that equips microorganisms with highly efficient light-harvesting inorganic semiconductors to realize light-driven carbon fixation (Brown and king, 2020). By employing cadmium sulfide nanoparticles, scientists not only enable the photosynthesis of acetic acid from carbon dioxide through Moorella thermoacetica (Sakimoto et al., 2016) but also enhance the CO2 fixation pathway in E. coli (Hu et al., 2021). Furthermore, this technique also enhances the yields of l-malate and butyrate from glucose with theoretical yields (1.48 and 0.79 mol/mol) in E. coli (Hu et al., 2021). So, interdisciplinary light and/or electrically driven synthetic biotechnology will shine their light on CO2 neutrality with more high value–added products and higher efficiency in the future.

Author Contributions

XZ, YZ, and A-FX contributed in article planning, writing, and revision. AZ and BF contributed to article revision and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21978245) and the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX20200197) funded this work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Angermayr, S. A., Gorchs Rovira, A., and Hellingwerf, K. J. (2015). Metabolic Engineering of Cyanobacteria for the Synthesis of Commodity Products. Trends Biotechnol. 33 (6), 352–361. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.03.009

Antonovsky, N., Gleizer, S., Noor, E., Zohar, Y., Herz, E., Barenholz, U., et al. (2016). Sugar Synthesis from CO2 in Escherichia coli. Cell 166 (1), 115–125. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.064

Aresta, M., Dibenedetto, A., and Quaranta, E. (2016). Reaction Mechanisms in Carbon Dioxide Conversion. Berlin, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Bang, J., and Lee, S. Y. (2018). Assimilation of Formic Acid and CO2 by Engineered Escherichia Coliequipped with Reconstructed One-Carbon Assimilation Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115 (40), E9271–E9279. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810386115

Bang, J., Hwang, C. H., Ahn, J. H., Lee, J. A., and Lee, S. Y. (2020). Escherichia coli is Engineered to Grow on CO2 and Formic Acid. Nat. Microbiol. 5 (12), 1459–1463. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-00793-9

Barbero, R., Carnelli, L., Simon, A., Kao, A., Monforte, A. d. A., Riccò, M., et al. (2013). Engineered Yeast for Enhanced CO2 Mineralization. Energy Environ. Sci. 6 (2), 660–674. doi:10.1039/C2EE24060B

Behle, A., Saake, P., Germann, A. T., Dienst, D., and Axmann, I. M. (2020). Comparative Dose-Response Analysis of Inducible Promoters in Cyanobacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 (4), 843–855. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00505

Bhat, J. Y., Thieulin-Pardo, G., Hartl, F. U., and Hayer-Hartl, M. (2017). Rubisco Activases: AAA+ Chaperones Adapted to Enzyme Repair. Front. Mol. Biosci. 4, 20. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2017.00020

Bhunia, B., Prasad Uday, U. S., Oinam, G., Mondal, A., Bandyopadhyay, T. K., and Tiwari, O. N. (2018). Characterization, Genetic Regulation and Production of Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides and its Applicability for Heavy Metal Removal. Carbohydr. Polym. 179, 228–243. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.091

Binnenkade, L., Kreienbaum, M., and Thormann, K. M. (2018). Characterization of exeM, an Extracellular Nuclease of Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1761. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01761

Boyeldieu, A., Ali Chaouche, A., Ba, M., Honoré, F. A., Méjean, V., and Jourlin-Castelli, C. (2020). The Phosphorylated Regulator of Chemotaxis Is Crucial throughout Biofilm Biogenesis in Shewanella Oneidensis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 6 (1), 54. doi:10.1038/s41522-020-00165-5

Brown, K. A., and King, P. W. (2020). Coupling Biology to Synthetic Nanomaterials for Semi-artificial Photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 143 (2), 193–203. doi:10.1007/s11120-019-00670-5

Cai, T., Sun, H., Qiao, J., Zhu, L., Zhang, F., Zhang, J., et al. (2021). Cell-free Chemoenzymatic Starch Synthesis from Carbon Dioxide. Science 373 (6562), 1523–1527. doi:10.1126/science.abh4049

Castañeda-Losada, L., Adam, D., Paczia, N., Buesen, D., Steffler, F., Sieber, V., et al. (2021). Bioelectrocatalytic Cofactor Regeneration Coupled to CO 2 Fixation in a Redox‐Active Hydrogel for Stereoselective C−C Bond Formation. Angew. Chem. Intl. Edit. 60, 21056–21061. doi:10.1002/anie.202103634

Cheah, W. Y., Ling, T. C., Juan, J. C., Lee, D.-J., Chang, J.-S., and Show, P. L. (2016). Biorefineries of Carbon Dioxide: from Carbon Capture and Storage (Ccs) to Bioenergies Production. Bioresour. Tech. 215, 346–356. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.04.019

Chen CH, C.-H., Tseng, I.-T., Lo, S.-C., Yu, Z.-R., Pang, J.-J., Chen, Y.-H., et al. (2020). Manipulating ATP Supply Improves In Situ CO2 Recycling by Reductive TCA Cycle in Engineered Escherichia coli. 3 Biotech. 10 (3), 1–8. doi:10.1007/s13205-020-2116-7

Chen FYH, F. Y. H., Jung, H.-W., Tsuei, C.-Y., and Liao, J. C. (2020). Converting Escherichia coli to a Synthetic Methylotroph Growing Solely on Methanol. Cell 182 (4), 933–946. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.010

Chen H, H., Simoska, O., Lim, K., Grattieri, M., Yuan, M., Dong, F., et al. (2020). Fundamentals, Applications, and Future Directions of Bioelectrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 120 (23), 12903–12993. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00472

Cheng L, L., Min, D., He, R. L., Cheng, Z. H., Liu, D. F., and Yu, H. Q. (2020). Developing a Base‐editing System to Expand the Carbon Source Utilization Spectra of Shewanella Oneidensis MR‐1 for Enhanced Pollutant Degradation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 117, 2389–2400. doi:10.1002/bit.27368

Cheng ZH, Z. H., Xiong, J. R., Min, D., Cheng, L., Liu, D. F., Li, W. W., et al. (2020). Promoting Bidirectional Extracellular Electron Transfer of Shewanella Oneidensis MR‐1 for Hexavalent Chromium Reduction via Elevating Intracellular cAMP Level. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 117 (5), 1294–1303. doi:10.1002/bit.27305

Chida, H., Nakazawa, A., Akazaki, H., Hirano, T., Suruga, K., Ogawa, M., et al. (2007). Expression of the Algal Cytochrome C6 Gene in Arabidopsis Enhances Photosynthesis and Growth. Plant Cel Physiol. 48 (7), 948–957. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm064

Chou, A., Lee, S. H., Zhu, F., Clomburg, J. M., and Gonzalez, R. (2021). An Orthogonal Metabolic Framework for One-Carbon Utilization. Nat. Metab. 3 (10), 1385–1399. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00453-0

De Porcellinis, A. J., Nørgaard, H., Brey, L. M. F., Erstad, S. M., Jones, P. R., Heazlewood, J. L., et al. (2018). Overexpression of Bifunctional Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase/sedoheptulose-1,7-Bisphosphatase Leads to Enhanced Photosynthesis and Global Reprogramming of Carbon Metabolism in Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002. Metab. Eng. 47, 170–183. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.001

Dundas, C. M., Walker, D. J. F., and Keitz, B. K. (2020). Tuning Extracellular Electron Transfer by Shewanella Oneidensis Using Transcriptional Logic gates. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 (9), 2301–2315. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00517

Fang, H., Wang, Y.-W., Xiao, J.-W., Cui, S., and Qin, Z. (2021). A New Mining Framework with Piecewise Symbolic Spatial Clustering. Appl. Energ. 298 (6), 117226. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117226

Fast, A. G., and Papoutsakis, E. T. (2018). Functional Expression of the Clostridium Ljungdahlii Acetyl-Coenzyme A Synthase in Clostridium Acetobutylicum as Demonstrated by a Novel In Vivo CO Exchange Activity En Route to Heterologous Installation of a Functional Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84 (7), e02307. doi:10.1128/AEM.02307-17

Flamholz, A. I., Dugan, E., Blikstad, C., Gleizer, S., Ben-Nissan, R., Amram, S., et al. (2020). Functional Reconstitution of a Bacterial CO2 Concentrating Mechanism in Escherichia coli. eLife 9, e59882. doi:10.7554/eLife.59882

Gassler, T., Sauer, M., Gasser, B., Egermeier, M., Troyer, C., Causon, T., et al. (2020). The Industrial Yeast Pichia pastoris Is Converted from a Heterotroph into an Autotroph Capable of Growth on CO2. Nat. Biotechnol. 38 (2), 210–216. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0363-0

Gleizer, S., Ben-Nissan, R., Bar-On, Y. M., Antonovsky, N., Noor, E., Zohar, Y., et al. (2019). Conversion of Escherichia coli to Generate All Biomass Carbon from CO2. Cell 179 (6), 1255–1263. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.009

Guadalupe-Medina, V., Wisselink, H. W., Luttik, M. A., de Hulster, E., Daran, J.-M., Pronk, J. T., et al. (2013). Carbon Dioxide Fixation by calvin-cycle Enzymes Improves Ethanol Yield in Yeast. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 6 (1), 125. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-6-125

Gupta, J. K., Rai, P., Jain, K. K., and Srivastava, S. (2020). Overexpression of Bicarbonate Transporters in the marine Cyanobacterium Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002 Increases Growth Rate and Glycogen Accumulation. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 13 (1), 17. doi:10.1186/s13068-020-1656-8

He, Y., Li, X., Cai, W., Lu, H., Ding, J., Li, H., et al. (2021). One-Pot Multiple-step Integration Strategy for Efficient Fixation of CO2 into Chain Carbonates by Azolide Anions Poly(ionic Liquid)s. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 9 (20), 7074–7085. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c01187

Ho, M.-Y., Shen, G., Canniffe, D. P., Zhao, C., and Bryant, D. A. (2016). Light-dependent Chlorophyll F Synthase Is a Highly Divergent Paralog of Psba of Photosystem Ii. Science 353 (6302), 886. doi:10.1126/science.aaf9178

Hu, G., Li, Y., Ye, C., Liu, L., and Chen, X. (2019). Engineering Microorganisms for Enhanced CO2 Sequestration. Trends Biotechnol. 37 (5), 532–547. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.10.008

Hu, G., Li, Z., Ma, D., Ye, C., Zhang, L., Gao, C., et al. (2021). Light-driven CO2 Sequestration in Escherichia coli to Achieve Theoretical Yield of Chemicals. Nat. Catal. 4 (5), 395–406. doi:10.1038/s41929-021-00606-0

Hwang, H., Yeon, Y. J., Lee, S., Choe, H., Jang, M. G., Cho, D. H., et al. (2015). Electro-biocatalytic Production of Formate from Carbon Dioxide Using an Oxygen-Stable Whole Cell Biocatalyst. Bioresour. Tech. 185, 35–39. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.02.086

Jayathilake, B. S., Bhattacharya, S., Vaidehi, N., and Narayanan, S. R. (2019). Efficient and Selective Electrochemically Driven Enzyme-Catalyzed Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Formate Using Formate Dehydrogenase and an Artificial Cofactor. Acc. Chem. Res. 52 (3), 676–685. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00551

Jeon, J.-M., Song, H.-S., Lee, D.-G., Hong, J. W., Hong, Y. G., Moon, Y.-M., et al. (2018). Butyrate-based N-Butanol Production from an Engineered Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng 41 (8), 1195–1204. doi:10.1007/s00449-018-1948-6

Jiang, W., Hernández Villamor, D., Peng, H., Chen, J., Liu, L., Haritos, V., et al. (2021). Metabolic Engineering Strategies to Enable Microbial Utilization of C1 Feedstocks. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17 (8), 845–855. doi:10.1038/s41589-021-00836-0

Johnson, N., Gross, R., and Staffell, I. (2021). Stabilisation Wedges: Measuring Progress towards Transforming the Global Energy and Land Use Systems. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 (6), 064011. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abec06

Kachel, B., and Mack, M. (2020). Engineering of Synechococcus Sp. Strain PCC 7002 for the Photoautotrophic Production of Light-Sensitive Riboflavin (Vitamin B2). Metab. Eng. 62, 275–286. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2020.09.010

Kamennaya, N. A., Ahn, S., Park, H., Bartal, R., Sasaki, K. A., and Holman, H. Y. (2015). Installing Extra Bicarbonate Transporters in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC6803 Enhances Biomass Production. Metab. Eng. 29, 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.002

Kasai, T., Tomioka, Y., Kouzuma, A., and Watanabe, K. (2019). Overexpression of the Adenylate Cyclase Gene cyaC Facilitates Current Generation by Shewanella Oneidensis in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Bioelectrochemistry 129, 100–105. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2019.05.010

Kim, S., Lindner, S. N., Aslan, S., Yishai, O., Wenk, S., Schann, K., et al. (2020). Growth of E. coli on Formate and Methanol via the Reductive glycine Pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16 (5), 538–545. doi:10.1038/s41589-020-0473-5

Kirsch, F., Luo, Q., Lu, X., and Hagemann, M., (2018). Inactivation of Invertase Enhances Sucrose Production in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis Sp. PCC 6803. Microbiol-SGM 164 (10), 1220–1228. doi:10.1099/mic.0.000708

Kian, K., Liguori, S., Pilorgé, H., Crawford, J. M., Carreon, M. A., Martin, J. L., et al. (2021). Prospects of CO2 Capture via 13X for Low-Carbon Hydrogen Production Using a Pd-Based Metallic Membrane Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 407, 127224. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.127224

Kumar, M., Sundaram, S., Gnansounou, E., Larroche, C., and Thakur, I. S. (2018). Carbon Dioxide Capture, Storage and Production of Biofuel and Biomaterials by Bacteria: a Review. Bioresour. Tech. 247, 1059–1068. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.050

Lau, N.-S., Matsui, M., and Abdullah, A. A.-A. (2015). Cyanobacteria: Photoautotrophic Microbial Factories for the Sustainable Synthesis of Industrial Products. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 1–9. doi:10.1155/2015/754934

Li FH, F.-H., Tang, Q., Fan, Y.-Y., Li, Y., Li, J., Wu, J.-H., et al. (2020). Developing a Population-State Decision System for Intelligently Reprogramming Extracellular Electron Transfer in Shewanella Oneidensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117 (37), 23001–23010. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006534117

Li, J., Tang, Q., Li, Y., Fan, Y.-Y., Li, F.-H., Wu, J.-H., et al. (2020a). Rediverting Electron Flux with an Engineered CRISPR-ddAsCpf1 System to Enhance the Pollutant Degradation Capacity of Shewanella Oneidensis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3599–3608. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b06378

Li, J., Kuang, Y., Meng, Y., Tian, X., Hung, W.-H., Zhang, X., et al. (2020b). Electroreduction of CO2 to Formate on a Copper-Based Electrocatalyst at High Pressures with High Energy Conversion Efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (16), 7276–7282. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c00122

Liang, F., Lindberg, P., and Lindblad, P. (2018). Engineering Photoautotrophic Carbon Fixation for Enhanced Growth and Productivity. Sust. Energ. Fuels 2 (12), 2583–2600. doi:10.1039/C8SE00281A

Lin, P.-C., Saha, R., Zhang, F., and Pakrasi, H. B. (2017). Metabolic Engineering of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway for Enhanced Limonene Production in the Cyanobacterium Synechocysti S Sp. PCC 6803. Sci. Rep. 7, 17503. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17831-y

Liu, T., Luo, X., Wu, Y., Reinfelder, J. R., Yuan, X., Li, X., et al. (2020). Extracellular Electron Shuttling Mediated by Soluble C-type Cytochromes Produced by Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10577–10587. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b06868

Lou, W., Tan, X., Song, K., Zhang, S., Luan, G., Li, C., et al. (2018). A Specific Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in the Atp Synthase Gene Significantly Improves Environmental Stress Tolerance of Synechococcus Elongatus PCC 7942. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84 (18), e01222. doi:10.1128/AEM.01222-18

Matsumoto, A., Koga, R., Kanaly, R. A., Kouzuma, A., and Watanabe, K. (2021). Identification of a Diguanylate Cyclase that Facilitates Biofilm Formation on Electrodes by Shewanella Oneidensis Mr-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87 (9), e00201. doi:10.1128/AEM.00201-21

Miao, R., Liu, X., Englund, E., Lindberg, P., and Lindblad, P. (2017). Isobutanol Production in Synechocystis PCC 6803 Using Heterologous and Endogenous Alcohol Dehydrogenases. Metab. Eng. Commun. 5, 45–53. doi:10.1016/j.meteno.2017.07.003

Morello, G., Siritanaratkul, B., Megarity, C. F., and Armstrong, F. A. (2019). Efficient Electrocatalytic CO2 Fixation by Nanoconfined Enzymes via a C3-To-C4 Reaction that Is Favored over H2 Production. ACS Catal. 9 (12), 11255–11262. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b03532

Nisar, A., Khan, S., Hameed, M., Nisar, A., Ahmad, H., and Mehmood, S. A. (2021). Bio-conversion of CO2 into Biofuels and Other Value-Added Chemicals via Metabolic Engineering. Microbiol. Res. 251, 126813. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2021.126813

Nozzi, N. E., Case, A. E., Carroll, A. L., and Atsumi, S. (2017). Systematic Approaches to Efficiently Produce 2,3-butanediol in a marine Cyanobacterium. ACS Synth. Biol. 6 (11), 2136–2144. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00157

Pacala, S., and Socolow, R. (2004). Stabilization Wedges: Solving the Climate Problem for the Next 50 Years with Current Technologies. Science 305 (5686), 968–972. doi:10.1126/science.1100103

Pankratova, G., Hederstedt, L., and Gorton, L. (2019). Extracellular Electron Transfer Features of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Analytica Chim. Acta 1076, 32–47. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2019.05.007

Pattharaprachayakul, N., Lee, M., Incharoensakdi, A., and Woo, H. M. (2020). Current Understanding of the Cyanobacterial CRISPR-Cas Systems and Development of the Synthetic CRISPR-Cas Systems for Cyanobacteria. Enzyme Microb. Tech. 140, 109619. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2020.10961910

Sakimoto, K. K., Wong, A. B., and Yang, P. (2016). Self-photosensitization of Nonphotosynthetic Bacteria for Solar-To-Chemical Production. Science 351 (351), 74–77. doi:10.1126/science.aad3317

Santos-Merino, M., Singh, A. K., and Ducat, D. C. (2019). New Applications of Synthetic Biology Tools for Cyanobacterial Metabolic Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 33. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2019.00033

Santos-Merino, M., Torrado, A., Davis, G. A., Röttig, A., Bibby, T. S., Kramer, D. M., et al. (2021). Improved Photosynthetic Capacity and Photosystem I Oxidation via Heterologous Metabolism Engineering in Cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 (11), e2021523118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021523118

Satanowski, A., Dronsella, B., Noor, E., Vögeli, B., He, H., Wichmann, P., et al. (2020). Awakening a Latent Carbon Fixation Cycle in Escherichia coli. Nat. Communnat. Commun. 11 (1), 5812. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19564-5

Seelajaroen, H., Haberbauer, M., Hemmelmair, C., Aljabour, A., Dumitru, L. M., Hassel, A. W., et al. (2019). Enhanced Bio‐Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide by Using Neutral Red as a Redox Mediator. ChemBioChem 20, 1196–1205. doi:10.1002/cbic.201800784

Sengupta, A., Madhu, S., and Wangikar, P. P. (2020). A Library of Tunable, Portable, and Inducer-free Promoters Derived from Cyanobacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 (7), 1790–1801. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00152

Shen, W., He, Y., Zhang, S., Li, J., and Fan, W. (2012). Yeast‐Based Microporous Carbon Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture. ChemSusChem 5 (7), 1274–1279. doi:10.1002/cssc.201100735

Silva, A. V., Edel, M., Gescher, J., and Paquete, C. M. (2020). Exploring the Effects of bolA in Biofilm Formation and Current Generation by Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Front. Microbiol. 11, 815. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00815

Silveira, C. M., and Almeida, M. G. (2013). Small Electron-Transfer Proteins as Mediators in Enzymatic Electrochemical Biosensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 3619–3635. doi:10.1007/s00216-013-6786-4

Sun, T., Li, S., Song, X., Diao, J., Chen, L., and Zhang, W. (2018). Toolboxes for Cyanobacteria: Recent Advances and Future Direction. Biotechnol. Adv. 36 (4), 1293–1307. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.04.007

Sun, W., Lin, Z., Yu, Q., Cheng, S., and Gao, H. (2021). Promoting Extracellular Electron Transfer of Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1 by Optimizing the Periplasmic Cytochrome C Network. Front. Microbiol. 12, 727709. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.727709

Tan, S.-I., and Ng, I.-S. (2021). Stepwise Optimization of Genetic RuBisCO-Equipped Escherichia coli for Low Carbon-Footprint Protein and Chemical Production. Green. Chem. 23, 4800–4813. doi:10.1039/d1gc00456e

Tros, M., Bersanini, L., Shen, G., Ho, M.-Y., van Stokkum, I. H. M., Bryant, D. A., et al. (2020). Harvesting Far-Red Light: Functional Integration of Chlorophyll F into Photosystem I Complexes of Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1861 (8), 148206. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148206

Ungerer, J., Wendt, K. E., Hendry, J. I., Maranas, C. D., and Pakrasi, H. B. (2018). Comparative Genomics Reveals the Molecular Determinants of Rapid Growth of the cyanobacteriumSynechococcus elongatusUTEX 2973. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115 (50), E11761–E11770. doi:10.1073/pnas.1814912115

Vayenos, D., Romanos, G. E., Papageorgiou, G. C., and Stamatakis, K. (2020). Synechococcus Elongatus PCC7942: a Cyanobacterium Cell Factory for Producing Useful Chemicals and Fuels under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Photosynth. Res. 146, 235–245. doi:10.1007/s11120-020-00747-6

Vellingiri, A., Song, Y. E., Munussami, G., Kim, C., Park, C., Jeon, B.-H., et al. (2019). Overexpression of C-type Cytochrome, CymA inShewanella oneidensisMR-1 for Enhanced Bioelectricity Generation and Cell Growth in a Microbial Fuel Cell. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 94 (7), 2115–2122. doi:10.1002/jctb.5813

Wang, X., and Song, C. (2020). Carbon Capture from Flue Gas and the Atmosphere: A Perspective. Front. Energ. Res. 8, 560849. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2020.560849

Wang, Y., Tao, F., Ni, J., Li, C., and Xu, P. (2015). Production of C3 Platform Chemicals from CO2 by Genetically Engineered Cyanobacteria. Green. Chem. 17 (5), 3100–3110. doi:10.1039/C5GC00129C

Wang, Y., Sun, T., Gao, X., Shi, M., Wu, L., Chen, L., et al. (2016). Biosynthesis of Platform Chemical 3-hydroxypropionic Acid (3-HP) Directly from CO2 in Cyanobacterium Synechocystis Sp. PCC 6803. Metab. Eng. 34, 60–70. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2015.10.008

Weinstock, M. T., Hesek, E. D., Wilson, C. M., and Gibson, D. G. (2016). Vibrio Natriegens as a Fast-Growing Host for Molecular Biology. Nat. Methods 13 (10), 849–851. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3970

Włodarczyk, A., Selão, T. T., Norling, B., and Nixon, P. J. (2020). Newly Discovered Synechococcus Sp. PCC 11901 Is a Robust Cyanobacterial Strain for High Biomass Production. Commun. Biol. 3, 215. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-0910-8

Xia, P.-F., Zhang, G.-C., Walker, B., Seo, S.-O., Kwak, S., Liu, J.-J., et al. (2016). Recycling Carbon Dioxide during Xylose Fermentation by Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth. Biol. 6 (2), 276–283. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00167

Xiberras, J., Klein, M., de Hulster, E., Mans, R., and Nevoigt, E. (2020). Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Succinic Acid Production from Glycerol and Carbon Dioxide. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 566. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00566

Yang, J. Y., Kerr, T. A., Wang, X. S., and Barlow, J. M. (2020). Reducing CO2 to HCO2- at Mild Potentials: Lessons from Formate Dehydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (46), 19438–19445. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c07965

Yi, Y.-C., and Ng, I.-S. (2021). Redirection of Metabolic Flux in Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1 by CRISPRi and Modular Design for 5-aminolevulinic Acid Production. Bioresour. Bioproc. 8, 13. doi:10.1186/s40643-021-00366-6

Yuan, M., Kummer, M. J., Milton, R. D., Quah, T., and Minteer, S. D. (2019). Efficient NADH Regeneration by a Redox Polymer-Immobilized Enzymatic System. ACS Catal. 9, 5486–5495. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b00513

Zhang, X., Li, L.-F., Du, Z.-F., Hao, X.-L., Cao, L., Luan, Z.-D., et al. (2020). Discovery of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide in a Hydrothermal System. Sci. Bull. 65 (11), 958–964. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2020.03.023

Zhang X, X., Betterle, N., Hidalgo Martinez, D., and Melis, A. (2021). Recombinant Protein Stability in Cyanobacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 10 (4), 810–825. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00610

Zhang Z, Z., Li, J., Ji, M., Liu, Y., Wang, N., Zhang, X., et al. (2021). Encapsulation of Multiple Enzymes in a Metal-Organic Framework with Enhanced Electro-Enzymatic Reduction of CO2 to Methanol. Green. Chem. 23, 2362–2371. doi:10.1039/D1GC00241D

Zhuang, X., Zhang, A., Qiu, S., Tang, C., Zhao, S., Li, H., et al. (2020). Coenzyme Coupling Boosts Charge Transport through Single Bioactive Enzyme Junctions. IScience 23 (4), 101001. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101001

Zhuang, X., Wu, Q., Zhang, A., Liao, L., and Fang, B. (2021). Single-molecule Biotechnology for Protein Researches. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 30, 212–224. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2020.10.031

Keywords: carbon neutrality, enzyme engineering, electrically driven microbial, carbon metabolic pathway, synthetic biotechnology

Citation: Zhuang X, Zhang Y, Xiao A-F, Zhang A and Fang B (2022) Applications of Synthetic Biotechnology on Carbon Neutrality Research: A Review on Electrically Driven Microbial and Enzyme Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10:826008. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.826008

Received: 30 November 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022;

Published: 25 January 2022.

Edited by:

Zhiguang Zhu, Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Tao Sun, Tianjin University, ChinaYongguang Jiang, China University of Geosciences Wuhan, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhuang, Zhang, Xiao, Zhang and Fang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aihui Zhang, emhhbmdhaWh1aUB4bXUuZWR1LmNu; Baishan Fang, ZmJzQHhtdS5lZHUuY24=

Xiaoyan Zhuang1

Xiaoyan Zhuang1 Aihui Zhang

Aihui Zhang Baishan Fang

Baishan Fang