- 1Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 2Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Institute for Translational Nanomedicine, Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 3School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 4The Institute for Biomedical Engineering and Nano Science, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

The foreign body response (FBR) caused by biomaterials can essentially be understood as the interaction between the immune microenvironment and biomaterials, which has severely impeded the application of biomaterials in tissue repair. This concrete interaction occurs via cells and bioactive substances, such as proteins and nucleic acids. These cellular and molecular interactions provide important cues for determining which element to incorporate into immunomodulatory biomaterials (IMBs), and IMBs can thus be endowed with the ability to modulate the FBR and repair damaged tissue. In terms of cellular, IMBs are modified to modulate functions of immune cells, such as macrophages and mast cells. In terms of bioactive substances, proteins and nucleic acids are delivered to influence the immune microenvironment. Meanwhile, IMBs are designed with high affinity for spatial targets and the ability to self-adapt over time, which allows for more efficient and intelligent tissue repair. Hence, IMB may achieve the perfect functional integration in the host, representing a breakthrough in tissue repair and regeneration medicine.

1 Introduction

With the development of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, biomaterials have been explored to design implants targeting promoting wound healing (Kim et al., 2017; Castaño et al., 2018; Nourian Dehkordi et al., 2019; Oliva and Almquist, 2020; Sharifi et al., 2020), repairing injured tissue (Han et al., 2019; Gaharwar et al., 2020; Primavera et al., 2020), constructing bionic organs (Eke et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Brennan et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), and so on (Chung et al., 2017; Pugliese and Gelain, 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Sultankulov et al., 2019). Some of these biomaterials such as wound healing adhesives and bone cement, have been applied in clinical situations and have benefited patients worldwide (Schmalz and Galler, 2017; Perez et al., 2018; Turnbull et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Kargozar et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2020a; Armiento et al., 2020; Khare et al., 2020). Regenerative medicine approaches that repair damaged and malfunctioned tissues using biomaterials have a promising future (Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2020; D'Este et al., 2018; Kowalski et al., 2018; Defraeye and Martynenko, 2018).

However, when biomaterials are integrated into the host, the foreign body response (FBR) inevitably arises (Doloff et al., 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2017; Chandorkar et al., 2018; Sharifi et al., 2019; Veiseh and Vegas, 2019), in which the immune microenvironment interacts with biomaterials via humoral and cellular factors, and this process determines the success of the integration and the biological performance of the biomaterials (Anderson et al., 2008; Sadtler et al., 2016a; Chu et al., 2019). When the FBR is excessively happened, inflammation, fibrosis, infection, and thrombosis can occur (Bitar, 2015; Adu-Berchie and Mooney, 2020), resulting in material degradation, fiber proliferation, and so on, which impedes the morphological and functional maintenance of biomaterials in vivo (Martin and Leibovich, 2005; Bitar, 2015).

Immunomodulatory biomaterials (IMBs) are defined as biomaterials with the design to control the FBR processes in order to biomaterial−tissue integration and tissue repair, which are a feasible principle of biomaterial development (Sadtler et al., 2016b; Chu et al., 2017a; Andorko and Jewell, 2017; Chu et al., 2017b; Dziki and Badylak, 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2019; Adu-Berchie and Mooney, 2020; Hu et al., 2021). In the design of the IMBs, the immune-related substances or cells can be attached to the biomaterials, to produce an immunomodulatory effect on the microenvironment and to control the FBR. Since the FBR essentially arises from the interaction between the immune microenvironment and the biomaterials, many researchers have designed IMBs based on modulating these interactions, and the design element used were coming from the analysis of specific interactions, such as those between cells and bioactive substances which including proteins, and nucleic acids, and so on (Dellacherie et al., 2019; Eslami-Kaliji et al., 2020; Lasola et al., 2020).

In this review, we summarized the development of IMBs incorporating the cells and substances involved in the interaction between IMBs and the immune microenvironment. The principle and aim of IMB modification should be the modulation of the FBR by regulating interactions, resulting in IMBs that can function in tissue regeneration and repair.

2 The Mechanism of the Foreign Body Response: The Interactions Between Immunomodulatory Biomaterial and Immune Microenvironment

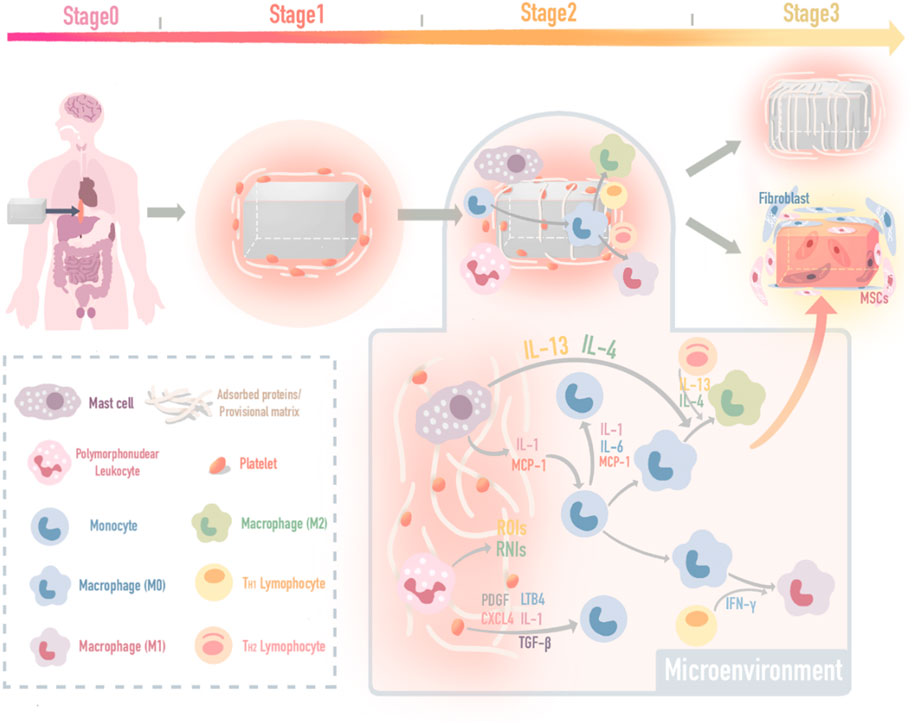

As several excellent reviews have elaborated on the mechanism and biological process of the FBR, we have briefly summarized these processes and divided them into the following three stages (Mariani et al., 2019; Gaharwar et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021) (Figure 1)

1) Protein adsorption. The first FBR stage occurs within seconds, in which components of the blood, including fibrous protein immediately adsorbed onto the surface of the biomaterial and platelets adherent (forming a provisional matrix) (Barker and Engler, 2017; Wight, 2017; Mendes et al., 2018). The complement system in the host is activated at the same time (Barrington et al., 2001; Donat et al., 2019; Haapasalo and Meri, 2019), directly attacks the cells in the biomaterial implants and recruits neutrophil infiltration, resulting in vascular endothelial damage, fibrin deposition, and massive platelet aggregation around the implant (Park et al., 2018a; Rahman et al., 2018; Braune et al., 2019; Tanneberger et al., 2021).

2) Acute inflammation. The second stage occurs within a few hours to a few days. The provisional matrix contains many growth factors and chemokines, which recruit mast cells and multinucleated lymphocytes (Zhou and Groth, 2018; Lock et al., 2019; Teixeira et al., 2020). Mast cells release TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1, which recruit monocytes and activate Toll-like receptors on the monocyte surface to stimulate maturity (Beghdadi et al., 2011; Maximiano et al., 2017; Komi et al., 2020; Ozpinar et al., 2021a). On this basis, TH1 lymphocytes (Th1) release IFN-γ to promote macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype (M1) (Mariani et al., 2019; Vassey et al., 2020), M1 macrophages release IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and TNF-α to mediate inflammation, and the protein mentioned above can further stimulate the polarization of macrophages (Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Zhou et al., 2020a; Engler et al., 2020).

3) Host integration. The third stage occurs a few days after the second stage, and its direction depends on the immunomodulatory results of the previous two stages. In the microenvironment with inflammation-related genes (IL-1β-related genes, etc.) upregulation (He et al., 2020; Nakkala et al., 2021a), FBR outcomes such as chronic inflammation, excessive granulation, collagen fiber deposition and fibrous tissue formation (Castaño et al., 2018; Adu-Berchie and Mooney, 2020; Gaharwar et al., 2020). In regard to FBR controlled, fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are recruited to regenerate and continue a good repair process (Hannan et al., 2017; Soundararajan and Kannan, 2018; Wang et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1. The mechanism map of three FBR stages. The mechanism and biological process of the foreign body response (FBR) induced by implants include three stages: protein adsorption, inflammation, and in vivo integration.

3 Interaction Links: Cues for the Development of Immunomodulatory Biomaterials With Integrated Substances

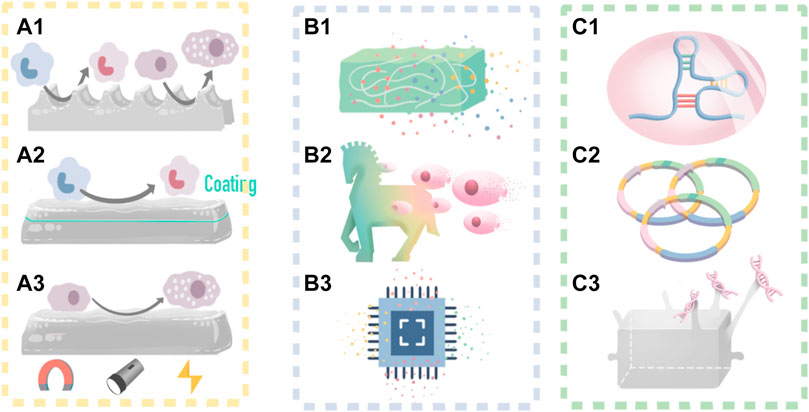

The FBR process remodels and integrates the implants into the immune microenvironment of the host by interacting with cells and bioactive substances. Therefore, the IMB should be designed with an “immune-informed” ability (Reid et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2018; Mariani et al., 2019; Adu-Berchie and Mooney, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), precisely, the ability to regulate microenvironment bioactive substances to form feedback. In this way, the interaction between the FBR activity and IMB feedback can control the FBR by regulating bioactive substances. In this review, the interactions among regulating cells and bioactive substances which including proteins and nucleic acids are summarized, which provide cues for determining IMB incorporation strategies to achieve better tissue repair. (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. IMB decoration methods and a self-adaptive example. (A) IMB decoration with cues from cell; (A1) decorate surface morphology and mechanical properties to control macrophages and mast cells; (A2) add biochemical coating to control macrophage M2 polarization; (A3) control macrophage polarization by time-dependent change of external stimulus. (B) IMB decoration strategy with cues from protein delivery; (B1) decorate scaffold to be a delivery syetem; (B2) decorate MSCs to be a delivery syetem for high-targetting; (B3) integrated sustained-release chips. (C) IMB decoration with cues from nucleic acid; (C1) RNA interference; (C2) plasmid vectors; (C3) DNA grafting.

4 Cell Interaction: Modifying Immunomodulatory Biomaterials to Modulate Immune Cell Functions

4.1 Macrophage Polarization

Macrophages play an important role in the second stage of the FBR (Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Petrosyan et al., 2017; Boada-Romero et al., 2020) and mainly exist as the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. The M1 phenotype secretes numerous matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and different cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, which further stimulates the inflammatory response (Delavary et al., 2011; Vishwakarma et al., 2016; Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Olingy et al., 2019; Davenport Huyer et al., 2020). Meanwhile, different macrophage phenotypes can arise in response to immune information (Sica and Bronte, 2007; Liu and Yang, 2013; Vassey et al., 2020; Muñoz-Rojas et al., 2021). Therefore, many researchers aim to design IMBs capable of transforming naive macrophages or M1 macrophages in the microenvironment into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and improve the anti-inflammatory ability and tissue repair function of the IMB (Sridharan et al., 2015; Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Ghasemi et al., 2019; Yin et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020a; Engler et al., 2020). IMB modification methods can be focused on biophysical cues and biochemical cues.

4.1.1 Biophysical Modifications

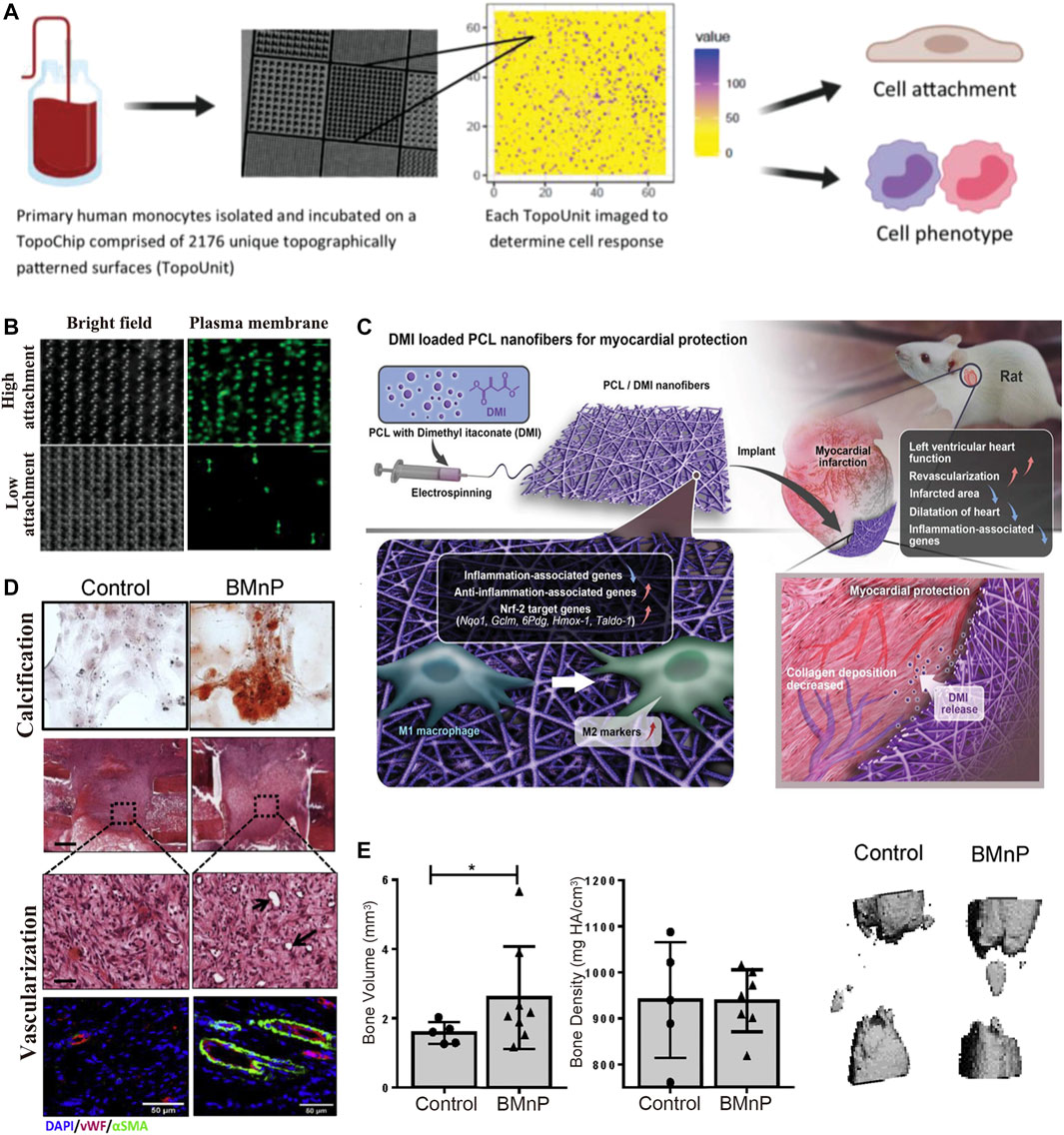

Macrophage polarization can be controlled by biophysical cues, such as surface morphology (Sridharan et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2020a; Davenport Huyer et al., 2020; Muñoz-Rojas et al., 2021) (Figure 2A1, Figures 3A,B).

FIGURE 3. IMB Decoration with cues from macrophage polarization. (A,B) Reprinted with Creative Commons CC BY license(Vassey et al., 2020). (A) A high throughput screening approach is utilized to investigate the relationship between 2,176 micropatterns surface morphology and macrophage attachment and phenotype. (B) Micropillars 5–10 μm in diameter play a dominant role in driving macrophage attachment and M2 phenotype. (C) Dimethyl itaconate (DMI)-loaded PCL nanofibers and their roles on modulating the polarization of M1 into alternatively activated M2 macrophages, and protecting from myocardial infarction in vivo by improving left ventricular heart functions and down regulating inflammation-associated genes. Reprinted with permission from© 2022 WILEY (Nakkala et al., 2021b). (D,E) Nano-particle treated macrophages enhances osteogenic differentiation and vascularization. Reprinted with permission from© 2022 WILEY (Arizmendi et al., 2021).

In terms of mechanical properties, macrophages perceive the material’s rigidity through Rac-1 mechanosensory pathways, which then influence M1/M2 polarization (Acevedo and González-Billault, 2018; Guimarães et al., 2020; Healy et al., 2020). Many studies have demonstrated that M2 is the main direction of macrophage polarization on soft materials (Li et al., 2018; Guimarães et al., 2020; Atcha et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2021). For example, Blakney et al. (2012) have shown that when the internal rigidity of 3D polyethylene glycol-RGD is kept at 130 kPa (low stiffness), the proportion of M2 macrophages increases, upregulating the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and inhibiting the FBR. Yanlun Zhu et al. (Zhu et al., 2021) used rigid regulation cues and added bioactive glass to sodium alginate hydrogel to soften its mechanical properties, which effectively promoted M2 polarization and optimized the repair effect in damaged skin tissue.

Macrophages are sensitive to surface morphology changes larger than 5 μm, as a result of Rac-1 mechanosensory pathway and F-actin changes (Acevedo and González-Billault, 2018; Guimarães et al., 2020; Healy et al., 2020). Matthew et al. (Vassey et al., 2020) used a high-throughput method to screen the relationship between 2,176 types of surface morphology and macrophage attachment and phenotype. The results showed that modifying the IMB surface with microcolumns, retaining a diameter between five and 10 μm, yields excellent effects on macrophage attachment and M2 polarization.

Pore size is also an important driver of macrophage polarization. Fa-Ming Chen et al.(Yin et al., 2020b) proved that collagen-scaffolds with 360 μm sized pore promoted macrophages undergoing a higher degree of M1-to-M2 transition. Groll et al. (Tylek et al., 2020) pronounced that fibrous scaffolds with inter-fiber pore from 100 to 40 μm facilitated macrophage elongation accompanied by M2 polarization. Also, M2 polarization was reported in response to polyurethane scaffolds with 100 μm sized pore (Liang et al., 2018). In general, macrophages could undergo M2 polarization in macro pores with sizes ranging from tens of microns to hundreds of microns. The specific optimal pore size varies greatly among different materials due to the properties of scaffold materials, such as rigidity and elasticity.

4.1.2 Biochemical Decorations

Chemical coatings and nanomaterial coatings are also feasible mainstream research directions (Davenport Huyer et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020). For example, Nakkala et al. (2021b) showed that a dimethyl itaconate (DMI) coating on IMBs promoted the adhesion of M2 macrophage, and protected against myocardial infarction in vivo by improving left ventricular heart function. McBane and others studies have shown that coating IMBs hydrophobic ionic polyurethane (DPHI) has produces effective anti-inflammatory activities. Mahon et al. (2020) performed an immunomodulatory modification of bone defect healing biomaterials by adding nanohydroxyapatite particles (BMnP), which promoted M2 polarization, tissue angiogenesis, and increased bone mass (Figure 3).

4.2 Cues From Mast Cell Maturity

Mast cells also play an essential role in the second stage of the FBR (Beghdadi et al., 2011), in which mast cells are activated to a mature state by several receptors, such as FcɛRI, Toll-like receptor, and RIG-like receptor (Beghdadi et al., 2011; Komi et al., 2020). Mature mast cells release histamine, tryptase and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) activate fibroblasts, who in turn release stem cell factor (SCF) to continue regulating MCs through CD117, which promote beneficial tissue repair process, like neovascularization and so on (Maximiano et al., 2017; Ozpinar et al., 2021a). Therefore, the controller strategy can be applied on mast cells to accelerate mast cell maturity, and thereby more cytokines will be secreted. Additionally, modification methods can be focused on biophysical cues and biochemical cues.

4.2.1 Biophysical Modifications

The maturation of mast cells can also be promoted by changing the material surface morphology (Atiakshin et al., 2018; De Zuani et al., 2018; Frossi et al., 2018; Chu et al., 2019; Sammarco et al., 2019; Galli et al., 2020; Ragipoglu et al., 2020; Yabut et al., 2020; Arizmendi et al., 2021). Maximiano et al. (2017) have indicated that, similar to macrophages, the maturity and functional activity of mast cells can also be controlled by the IMB surface morphology. For example, mast cells tend to adhere to and mature on IMBs constructed with large pore size microholes (Ozpinar et al., 2021b) (Figure 2A1).

4.2.2 Biochemical Modifications

Maturation-associated receptors provide cues for accelerating the release of functional proteins from mast cells (Kempuraj et al., 2018; Olivera et al., 2018; Thangam et al., 2018; Widiapradja et al., 2019; Wilcock et al., 2019). Milmy et al. (Ortiz et al., 2020) demonstrated that PCL scaffolds modified to generate IMB scaffolds by the incorporation of dinitrophenyl IgE can activate FcɛRI to promote mast cell maturity and then further regulate the FBR and facilitate tissue repair by TNF-α and IL-13, which are released by mature mast cells. Modifications using that activate Toll-like receptors and c-type receptors are also a feasible method for “controlling” mast cell maturation and regulating the immune microenvironment (Ozpinar et al., 2021a).

4.3 More Promising Cues From Immune Cells

Macrophage polarization and mast cell maturation have been successfully promoted by IMBs, proving that modifying IMBs to “control” cell function is feasible. The highlight of this strategy is that immune information attached in a simple modification recognized by the cells in the microenvironment promotes the cells to differentiate as required for tissue repair. This strategy shifts the dominance of the interaction from the microenvironment to the material. The result of other studies have also indicated that other immune cells, such as T cells (Th1, Th2) (Choo et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2019), dendritic cells (Eslami-Kaliji et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Čolić et al., 2020), multinucleated lymphocytes, and even fibroblasts and MSCs (Soundara Rajan et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021) in the microenvironment could be controllable by modified IMBs to further regulate the FBR.

5 Cues From Protein Interaction: Modifying Immunomodulatory Biomaterials to Optimize Protein Delivery

5.1 Modified Immunomodulatory Biomaterial as Protein Delivery Systems

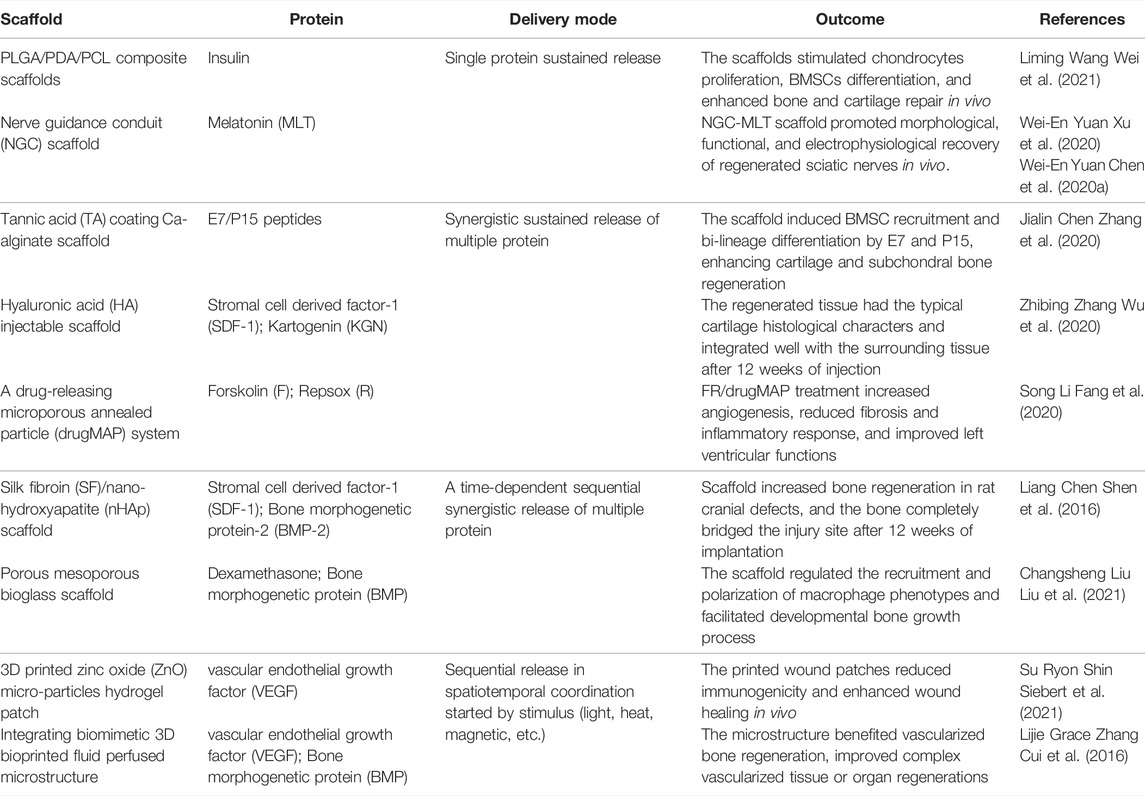

Proteins, including interleukins, growth factors, and complement proteins, are bioactive constituents of the immune microenvironment, that interact with cells and nucleic acids to form a microenvironmental regulatory network. Therefore, protein delivery is a viable strategy to regulate the FBR. (Sharma et al., 2016). Determining which effector proteins should be selected and how to deliver these proteins is a leading research direction (Chung et al., 2017; Leach et al., 2019). (Table 1).

In terms of protein selection (Fisher et al., 2017; Frejd and Kim, 2017; Grim et al., 2018; Simeon and Chen, 2018; Mohammadinejad et al., 2019), Sharma and others have demonstrated that the interleukin family (IL) has effects several target cells (Akdis et al., 2016; Ghilardi et al., 2020). For example, IL-1 enhances immune function, IL-4 and IL-13 regulate the inflammatory response (Arend et al., 2008). Therefore, implants modified with these proteins can inhibit the FBR and are better integrated into the surrounding tissue. Meanwhile, growth factor (GF) is a polypeptide substance that regulates cell growth and its expression can be upregulated in an inflammatory microenvironment, which can promote vascular regeneration (Akdis et al., 2016; Zbinden et al., 2020). Vascular regeneration inhibits the FBR, and the implant can integrate in the host to facilitate tissue repair. Additionally, the complement protein family (Donat et al., 2019), including some oligopeptides (Zhang et al., 2020), has been considered for IMB modification, because it is a component of the innate immune system and plays a vital role in the first stage of the FBR (Barrington et al., 2001; Haapasalo and Meri, 2019), this stage of the FBR can destroy biomaterials directly and also recruit neutrophils to facilitate uncontrolled progression to later FBR stage (Panichi et al., 2000). These proteins are representative bioactive substances that have been widely investigated as IMB modifications.

In terms of the delivery system (Shadish et al., 2019; Takeuchi et al., 2017; Kuo et al., 2018; Rehmann et al., 2017; Leijten et al., 2017), (Figure 2B), most biomaterials, such as alginate, PEGate-gelatin scaffolds, and collagen/hyaluronic acid scaffolds, possess their own slowly releasing proteins for internal charge adhesion and porosity, indicating that it is feasible to attach a protein delivery system to IMBs. One promising example is the use of a polyelectrolyte multilayer coating (PLG-scaffold) (Deng et al., 2020) to enhance the sustained-release function of IMBs, as the thickness of the coating can be easily modified to achieve different hydrophilic protein levels and release rates. For example, David et al. (Li et al., 2020) used a PLG coating modification for the sustained-release of steroid drugs to reduce aseptic inflammation in nerve prosthesis transplantation. Additionally, IMBs can be modified to carry multiple proteins through direct protein mixing and the use of integrated chips (Sharma et al., 2021). On this basis, a strategy for the sequential release of proteins in spatiotemporal coordination initiated by an external stimulus [light, heat (Gnaim and Shabat, 2019), magnetic (Orapiriyakul et al., 2020), acoustic wave (Moncion et al., 2017), etc.] has been proposed to align the IMB function with the tissue repair process in the body (Jimi et al., 2020; Oliva and Almquist, 2020) (Figure 2B3).

5.2 Optimal Immunomodulatory Biomaterial Modification: Highly Targeted Delivery Systems

To improve targeted delivery, many researchers have modified stem cells (Zhou et al., 2020b; Su et al., 2020), T cells (Choo et al., 2017; Cevaal et al., 2021), biological vesicles (Anika Nagelkerke, 2020; Brennan et al., 2020), and other vehicles into delivery systems due to their excellent biocompatibility and targeting ability to eliminate the problem of proteins diffusing locally around the implants (Jin et al., 2018).

For example, the Martinez team creatively proposed combining MSCs with nanocarriers to construct a multifunctional multicomponent “M&M delivery platform”. This IMB platform takes advantage of the inflammation-targeted function of MSCs, and the drug is accurately targeted and delivered to the activated immune microenvironment. IMBs constructed with a combination of a targeted carrier and a bioactive substance are vividly defined as “Trojan horses” (Martinez et al., 2021) (Figure 2B2). Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2017) demonstrated the feasibility of these IMBs by coating bioactive substances with platelet extension vesicles (PEVs) to regulate bleeding and protein deposition in the FBR.

The protein delivery strategy is the most widely used modification strategy at present (Ooi et al., 2017; Rosales et al., 2017; Brown, 2018; Hedegaard et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2018); the biomaterial itself is a suitable carrier for many regulatory proteins, and extensive knowledge of cytokines (interleukin family, growth factors, chemokines, etc.) in immunology provides a foundation for its application. The highlight of this approach is that in the material-microenvironment interaction process, the proteins are not only involved in cell and nucleic acid interactions but are also the main component of the FBR.

Therefore, the protein delivery strategy is simple and effective, and IMBs carrying proteins can directly prevent the progression of the FBR. Moreover, the targeted optimization of the “Trojan Horse” approach allows the delivered protein to act more specifically in the immune microenvironment, improves the efficacy of tissue repair and reduces the potential for a systemic response.

6 Cues From Nucleic Acid Interactions: Modifying Immunomodulatory Biomaterials Using Genome-Editing Techniques

6.1 Modifying Immunomodulatory Biomaterials to Determine Cell Fate and to Form a Regenerative Microenvironment

Recently, with the development of molecular biology and genome-editing techniques, a deep molecular understanding of the FBR has been obtained, which has provided cues for applying genome-editing techniques for the modification of IMBs (Mali and Cheng, 2012; Nelson and Gersbach, 2016; Kamburova et al., 2017; Glass et al., 2018; Metje-Sprink et al., 2019; Mushtaq et al., 2019; Vats et al., 2019; Ali et al., 2020). This approach can be used to generate IMBs that can regulate the immune cells, stem cells and fibroblasts recruited in the third stage of the FBR (Hiew et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2018; Ng et al., 2021). After using genome-editing techniques to integrate nucleic acid information into repair-related cells, such as MSCs, repair-related proteins such as growth factors are secreted, which promote a microenvironment more conducive to tissue repair. Additionally, the nucleic acids transcribed by MSCs can directly regulate stem cell fate, determine the direction of differentiation of specific cell types, and complete the repair of specific structures.

It is novel to use nucleic acids as an upstream regulation strategy. The progression of the FBR and the characteristics of the microenvironment are influenced by IMBs modified in this manner. This modification method targets earlier in the repair process than cellular- and protein-level modifications and is widely applicable for tissue repair and other directions. Of course, more research is still needed to determine the safety, ethical requirements, and stability of this approach.

6.2 Examples of Genome-Editing Techniques Applied for Immunomodulatory Biomaterial Modification

6.2.1 The RNA Interference (RNAi) Technique

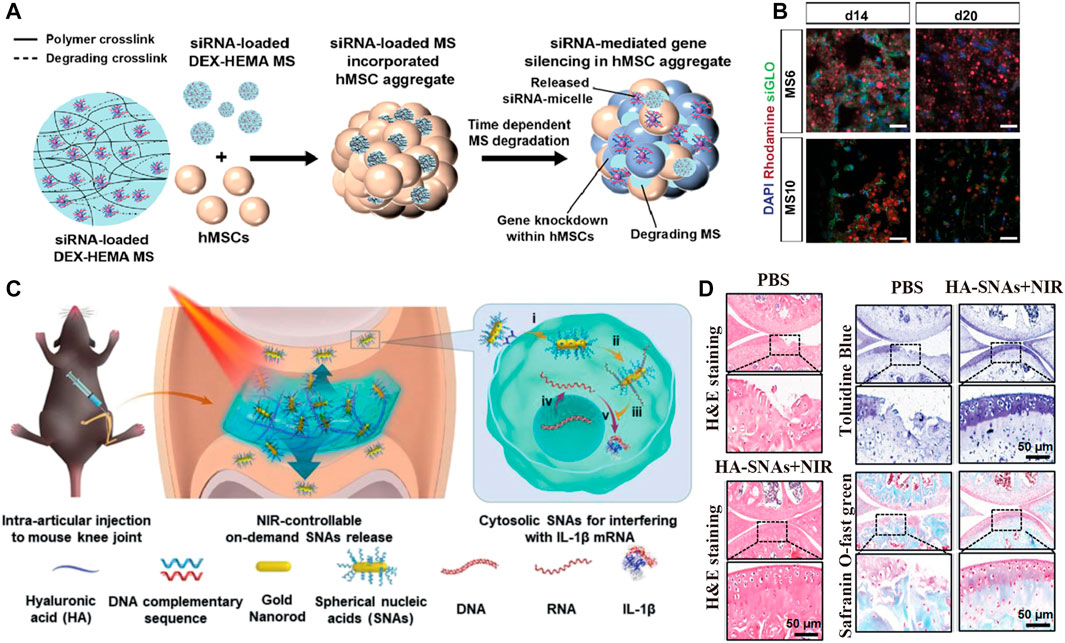

Alexandra McMillan et al. (2021) encapsulated RNA nanocomplexes in IMBs to construct IMBs with RNA interference (RNAi) technology to influence the cell fate decision at the messenger RNA (mRNA) level. The properties of IMB ensure the long-term retention and effectiveness of RNA nanocomplexes in vivo. The results proved that RNA nanocomplexes were still locally functional after 28 days and controlled the fate of stem cells, which differentiated into osteoblasts and chondrocytes, providing a new strategy for bone repair (Figure 2 C1, Figures 4A,B).

FIGURE 4. IMB Decoration with cues from nucleic acid-associated technologies. (A,B) Reprinted with permission from Copyright© 2022, Elsevier (Alexandra McMillan et al., 2021). (A) Schematic show the fabrication of DEX based MS encapsulating siRNA-micelles, and depicte the incorporation of siRNA-MS into a MSCs aggregate for localized and sustained siRNA presentation and subsequent sustained gene silencing within a stem cell aggregate. (B) Distribution of incorporated MS in MSCs aggregates for sustained siRNA presentation. Fluorescence confocal photomicrographs of rhodamine-labeled (red) siGLO-MS incorporated into MSCs aggregates to visualize siGLO uptake (green) and DAPI stained MSCs nuclei (blue) in 3D aggregates after different culture periods (C,D) Reprinted with Creative Commons CC BY license (Chen et al., 2020b). (C) NIR light-controllable SNAs release based on DNA-grafted HA for OA treatment. HA-SNAs system is injected into the knee joint and irradiated by NIR light to gradually release the SNAs, which enter into cells to interfere with mRNA molecules to silence IL-1 expression. (D) Histological staining shows the treatment of mouse after injection of PBS and HA-SNAs + NIR at 12 weeks after surgery.

6.2.2 The Plasmid Transfection Technique

In the study of Moreira (Moreira et al., 2021), plasmid vectors were attached to IMBs for the continuous production of repair- and regeneration-related proteins (e.g., VEGF and FGF) to promote tissue regeneration and repair. In this study, based on the original porous sponge material, chitosan (Ch) and polyethyleneimine (PEI) were used as nonviral vectors to transfer the plasmid encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (p-VEGF) and the plasmid encoding fibroblast growth factor-2 (p-FGF-2). The results showed that plasmid DNA rapidly produced these growth factors in the microenvironment, which induced the formation of capillary-like structures and promoted the assembly of endothelial cells into several capillary segments (Figure 2C2).

6.2.3 The DNA Grafting Technique

Chen et al. (2020b) modified hydrogel scaffolds by spherical nucleic acid and DNA grafting to regulate the immune microenvironment. Chen grafted complementary strand DNA onto hyaluronic acid to obtain DNAHA and then combined spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) by base pairing to form an SNA-DNAHA system. The DNA was unhybridized by photothermal induction, and the SNAs were released to downregulate the expression of inflammation-related genes, such as the IL-1β gene and the protease MMP gene, and upregulate the expression of matrix synthesis genes, such as the collagen II gene, thus controlling the inflammation caused by the FBR (Figure 2C3, Figures 4C,D).

7 Cues From the Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity of the FBR: Optimal Immunomodulatory Biomaterial Modifications for Responsiveness

7.1 Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity of the FBR: Requirement for Responsive Immunomodulatory Biomaterials

As described above, the FBR involves the integration of biomaterials into the immune microenvironment of the host through interaction with bioactive substances, such as cells, proteins, and nucleic acids. These interactions provide cues for biomaterial modification strategies, which allow IMBs to modulate the FBR and induce the evolution of the FBR toward tissue regeneration and repair (Campi et al., 2017; Lalitha Sridhar et al., 2017; Rose and De Laporte, 2018; Ashammakhi et al., 2019; Gonzalez-Fernandez et al., 2019; Riley et al., 2019; Daly et al., 2021).

However, the FBR and tissue repair occur in stages and have spatial-temporal heterogeneity; that is, the various bioactive substances form divergent interactions at different temporal points. The concept of responsive IMBs was proposed for modulating multiple interactions, in which the IMBs can respond to environmental or external stimuli and provide diverse immune information feedback at different stages of the FBR. In other words, responsive IMBs exert a combination of the effects of the three IMB modification strategies mentioned previously, and can produce the effect of cascade amplification in tissue repair.

Responses to both external and environmental stimuli have individual advantages, and both are promising targets for the development of responsive IMBs. External stimuli are artificially imposed and can be better controlled. Additionally, the design of biomarkers responsive to external biomaterials is achievable. Environmental stimuli arise from changes in the immune microenvironment, and the temporal point of the response is more reasonable, but it is uncontrollable in vivo, thus requires more rigorous design.

7.2 Utilizing External Stimuli to Form a Multiple-Stage Regulation

If the original three-dimensional material structure is endowed with the ability to respond to external stimuli, such as heat, light, magnetic, and so on, the modified IMBs can exert different functions over time, which allows for diverse regulation.

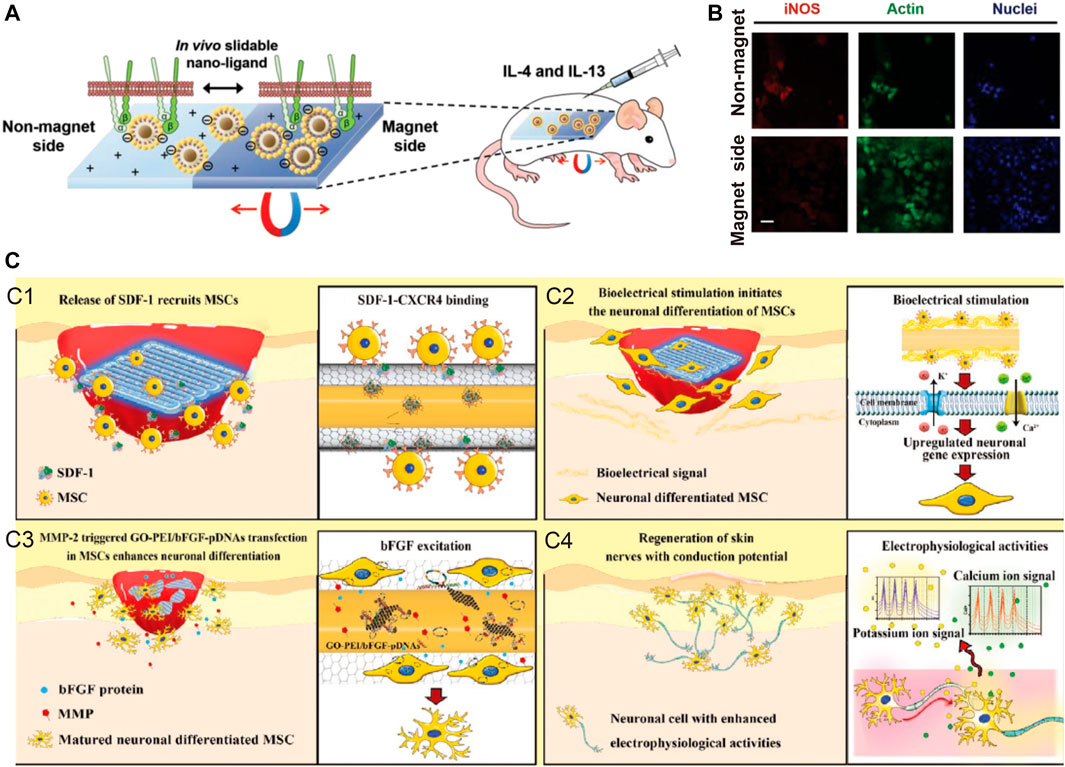

For example, magnetic nanomaterials are feasible carriers for the implementation of this strategy, and Choi and others have indicated that magnetic control of nanoligands can promote tissue regeneration (Choi et al., 2020). In their study, time-dependent magnetic stimulation was used to promote nanoligands carrying integrin-binding ligands (such as RGD) to aggregate in one area. Thus, the ligand density can be increased at a certain time point. When dense ligands aggregate the macrophage adhesion structure and promote the elongated assembly of actin, M1 phenotype polarization is inhibited, and M2 polarization is promoted. There are other examples of the use of external stimuli, such as ultraviolet (UV) light, which is used to trigger UV-mediated photolysis molecules and form different surface morphologies at different times, and this method has also been shown to be feasible for modulating various immune cell functions. (Figures 5A,B).

FIGURE 5. Examples of external stimuli and environmental stimuli. (A,B) Time-dependent magnetic attraction of the slidable nano-ligand facilitates macrophages adhesion, and stimulate regenerative M2 phenotype. Reprinted with permission from© 2022 WILEY (Choi et al., 2020). (C) Self-adaptive chip complete the damage skin repair with neuronal function by stimulating the nerve fiber formation and excitation function recovery with four major steps. Reprinted with permission from© 2022 WILEY (Li et al., 2020).

7.3 Utilizing Environmental Stimuli to Form a Self-Adaptive Regulation

Self-adaptive regulation of IMBs can provide diverse immune information feedback after initiation by changes in the immune environment, such as photothermal changes, pH changes, changes in the metabolites in the microenvironment, and so on, to inhibit multistage FBR and promote tissue repair.

Cui et al. (Cheng et al., 2020b) exploited the double responsiveness of NIPAAm molecules to explore this approach. When the FBR causes inflammation, the accumulated metabolites change the pH of the microenvironment and exceed the response threshold of NIPAAms, and NIPAAms respond to pH changes by releasing proteins through “gel transformation”, thus using the immune microenvironment as a method to activate the IMBs.

Gao et al. (Peng et al., 2020) designed a self-adaptive skin repair IMB, further demonstrating the feasibility of this approach. Self-adaptive IMBs can first increase the recruitment of MSCs into the microenvironment with a protein release strategy, then respond to the accumulation of stem cell matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and release pFGF/DNA, promoting the neuronal differentiation of MSCs through pFGF/DNA, and ultimately, lead to the repair and functional recovery of damaged skin. Zhang et al. also used MMP to degrade the outer scaffold and to realize the sequential release of VEGF and BMP in temporal coordination and produce better bone repair, as VEGF-induced vascularization provides a foundation for vascularized bone regeneration.

8 Discussion: Intelligent Immunomodulatory Biomaterials

Self-adaptive responses can initiate multiple superimposed interactions at the level of cells, proteins and nucleic acids, provide various stimuli required for regulating the FBR and repair processes, and produce cascading amplification effects. Meanwhile, IMBs with high targeting capacity are required for specificity, and the previously mentioned “Trojan Horse” approach has been developed to achieve this. Therefore, developing IMBs that provide self-adaptative feedback over time and have high targeting capacity within specific areas is a future direction of IMB modification research (Veiseh et al., 2015; Tzu-Chieh et al., 2021).

Nowadays, IMBs have promising application prospects, but there is still a gap between clinical uses. In the future, while the design of IMB is being optimized, biocompatibility and biosafety evaluation should also be necessary to demonstrate the safety of the final product. Meanwhile, cadaveric and clinical studies should be performed to validate that the product’s safety and efficacy could meet preset clinical needs.

In addition, for modifications involving cells and bioactive substances which including proteins and nucleic acids, high throughput screening can be used as a reference to determine targets (Park et al., 2018b; Seo et al., 2018) and for more advanced mathematical modeling and big data analysis methods (Yang et al., 2021), which may result in better outcomes for screening surface morphology, modeling interactions between cytokines, and so on. Additionally, this approach will improve the stability and effect of single interactions and provide a foundation for intelligent self-adaptive tissue repair.

Author Contributions

YiC, WS, HT, YuC, and CC contributed to the conception and design of the study. YiC, YL, LW, JC, SL, WL, and ZF collected and analyzed the data. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81770091).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acevedo, A., and González-Billault, C. (2018). Crosstalk between Rac1-Mediated Actin Regulation and ROS Production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 116, 101–113. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.008

Adu-Berchie, K., and Mooney, D. J. (2020). Biomaterials as Local Niches for Immunomodulation. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1749–1760. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00341

Akdis, M., Aab, A., Altunbulakli, C., Azkur, K., Costa, R. A., Crameri, R., et al. (2016). Interleukins (From IL-1 to IL-38), Interferons, Transforming Growth Factor β, and TNF-α: Receptors, Functions, and Roles in Diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 984–1010. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.033

Alexandra McMillan, M. K. N. C., SamanthaSarett, M. P. G. M. C., and Kien Nguyen, D. G. C. L. (2021). Hydrogel Microspheres for Spatiotemporally Controlled Delivery of RNA and Silencing Gene Expression within Scaffold-free Tissue Engineered Constructs. Acta Biomater. 124, 315–326. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2021.01.013

Ali, Z., Mahfouz, M. M., and MansoorCRISPR-Tsko, S. (2020). CRISPR-TSKO: A Tool for Tissue-specific Genome Editing in Plants. Trends Plant Science 25, 123–126. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2019.12.002

Anderson, J. M., Rodriguez, A., and Chang, D. T. (2008). Foreign Body Reaction to Biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 20, 86–100. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004

Andorko, J. I., and Jewell, C. M. (2017). Designing Biomaterials with Immunomodulatory Properties for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioeng. Translational Med. 2, 139–155. doi:10.1002/btm2.10063

Anika Nagelkerke, M. O. L. V. (2020). Extracellular Vesicles for Tissue Repair and Regeneration: Evidence, Challenges and Opportunities. Groningen: Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews.

Arend, W. P., Palmer, G., and Gabay, C. (2008). IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 Families of Cytokines. Immunological Rev. 223, 20–38. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065x.2008.00624.x

Arizmendi, N., Qian, H., Li, Y., and Kulka, M. (2021). Sesquiterpene-Loaded Co-polymer Hybrid Nanoparticle Effects on Human Mast Cell Surface Receptor Expression, Granule Contents, and Degranulation. Nanomaterials 11, 953. doi:10.3390/nano11040953

Armiento, A. R., Hatt, L. P., Sanchez Rosenberg, G., Thompson, K., and Stoddart, M. J. (2020). Functional Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration: A Lesson in Complex Biology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909874. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909874

Ashammakhi, N., Ahadian, S., Xu, C., Montazerian, H., Ko, H., Nasiri, R., et al. (2019). Bioinks and Bioprinting Technologies to Make Heterogeneous and Biomimetic Tissue Constructs. Mater. Today Bio 1, 100008. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2019.100008

Atcha, H., Jairaman, A., Holt, J. R., Meli, V. S., Nagalla, R. R., Veerasubramanian, P. K., et al. (2021). Mechanically Activated Ion Channel Piezo1 Modulates Macrophage Polarization and Stiffness Sensing. Nat. Commun. 12, 3256–3314. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23482-5

Atiakshin, D., Buchwalow, I., Samoilova, V., and Tiemann, M. (2018). Tryptase as a Polyfunctional Component of Mast Cells. Histochem. Cel Biol 149, 461–477. doi:10.1007/s00418-018-1659-8

Barker, T. H., and Engler, A. J. (2017). The Provisional Matrix: Setting the Stage for Tissue Repair Outcomes. Matrix Biol. 60-61, 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2017.04.003

Barrington, R., Zhang, M., Fischer, M., and Carroll, M. C. (2001). The Role of Complement in Inflammation and Adaptive Immunity. Immunological Rev. 180, 5–15. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800101.x

Beghdadi, W., Madjene, L. C., Benhamou, M., Charles, N., Gautier, G., Launay, P., et al. (2011). Mast Cells as Cellular Sensors in Inflammation and Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2, 37. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2011.00037

Blakney, A. K., Swartzlander, M. D., and Bryant, S. J. (2012). Student Award winner in the Undergraduate Category for the Society of Biomaterials 9th World Biomaterials Congress, Chengdu, China, June 1-5, 2012. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 100A, 1375–1386. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34104

Boada-Romero, E., Martinez, J., Heckmann, B. L., and Green, D. R. (2020). The Clearance of Dead Cells by Efferocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol 21, 398–414. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-0232-1

Braune, S., Latour, R. A., Reinthaler, M., Landmesser, U., Lendlein, A., and Jung, F. (2019). In Vitro Thrombogenicity Testing of Biomaterials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1900527. doi:10.1002/adhm.201900527

Brennan, M. Á., Layrolle, P., and Mooney, D. J. (2020). Biomaterials Functionalized with MSC Secreted Extracellular Vesicles and Soluble Factors for Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909125. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909125

Campi, G., Cristofaro, F., Pani, G., Fratini, M., Pascucci, B., Corsetto, P. A., et al. (2017). Heterogeneous and Self-Organizing Mineralization of Bone Matrix Promoted by Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 9, 17274–17283. doi:10.1039/c7nr05013e

Castaño, O., Pérez-Amodio, S., Navarro-Requena, C., Mateos-Timoneda, M. Á., and Engel, E. (2018). Instructive Microenvironments in Skin Wound Healing: Biomaterials as Signal Releasing Platforms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 129, 95–117. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.03.012

Cevaal, P. M., Ali, A., Czuba-Wojnilowicz, E., Symons, J., Lewin, S. R., Cortez-Jugo, C., et al. (2021). In Vivo T Cell-Targeting Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems: Considerations for Rational Design. ACS Nano 15, 3736–3753. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c09514

Chandorkar, Y., K, R., and Basu, B. (2018). The Foreign Body Response Demystified. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 19–44. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00252

Chang, C., Yan, J., Yao, Z., Zhang, C., Li, X., and Mao, H. Q. (2021). Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Paracrine Signals and Their Delivery Strategies. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001689. doi:10.1002/adhm.202001689

Chen, X., Ge, X., Qian, Y., Tang, H., Song, J., Qu, X., et al. (2020). Electrospinning Multilayered Scaffolds Loaded with Melatonin and Fe 3 O 4 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004537. doi:10.1002/adfm.202004537

Chen, Z., Zhang, F., Zhang, H., and Chen, L. (2020). DNA-grafted Hyaluronic Acid System with Enhanced Injectability and Biostability for Photo-Controlled Osteoarthritis Gene Therapy. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004793. doi:10.1002/advs.202004793

Cheng, L., Cai, Z., Ye, T., Yu, X., Chen, Z., Yan, Y., et al. (2020). Injectable Polypeptide-Protein Hydrogels for Promoting Infected Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001196. doi:10.1002/adfm.202001196

Cheng, L., Sun, X., Chen, L., Zhang, L., Wang, F., Zhang, Y., et al. (2020). Nano-in-micro Electronspun Membrane: Merging Nanocarriers and Microfibrous Scaffold for Long-Term Scar Inhibition. Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125405. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125405

Choi, H., Bae, G., Khatua, C., Min, S., Jung, H. J., Li, N., et al. (2020). Remote Manipulation of Slidable Nano-Ligand Switch Regulates the Adhesion and Regenerative Polarization of Macrophages. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001446. doi:10.1002/adfm.202001446

Choo, E. H., Lee, J.-H., Park, E.-H., Park, H. E., Jung, N.-C., Kim, T.-H., et al. (2017). Infarcted Myocardium-Primed Dendritic Cells Improve Remodeling and Cardiac Function after Myocardial Infarction by Modulating the Regulatory T Cell and Macrophage Polarization. Circulation 135, 1444–1457. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.116.023106

Chu, C., Deng, J., Hou, Y., Xiang, L., Wu, Y., Qu, Y., et al. (2017). Application of PEG and EGCG Modified Collagen-Base Membrane to Promote Osteoblasts Proliferation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 76, 31–36. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.157

Chu, C., Deng, J., Sun, X., Qu, Y., and Man, Y. (2017). Collagen Membrane and Immune Response in Guided Bone Regeneration: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Tissue Eng. B: Rev. 23, 421–435. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2016.0463

Chu, C., Liu, L., Rung, S., Wang, Y., Ma, Y., Hu, C., et al. (2019). Modulation of Foreign Body Reaction and Macrophage Phenotypes Concerning Microenvironment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 108, 127–135. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.36798

Chung, L., Maestas, D. R., Housseau, F., and Elisseeff, J. H. (2017). Key Players in the Immune Response to Biomaterial Scaffolds for Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 114, 184–192. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.006

Čolić, M., Tomić, S., and Bekić, M. (2020). Immunological Aspects of Nanocellulose. Immunol. Lett. 222, 80–89. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2020.04.004

Cui, H., Zhu, W., Holmes, B., and Zhang, L. G. (2016). Biologically Inspired Smart Release System Based on 3D Bioprinted Perfused Scaffold for Vascularized Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Sci. 3, 1600058. doi:10.1002/advs.201600058

D'Este, M., Eglin, D., and Alini, M. (2018). Lessons to Be Learned and Future Directions for Intervertebral Disc Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 78, 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2018.08.004

Daly, A. C., Davidson, M. D., and Burdick, J. A. (2021). 3D Bioprinting of High Cell-Density Heterogeneous Tissue Models through Spheroid Fusion within Self-Healing Hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 12, 753–813. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21029-2

Davenport Huyer, L., Pascual-Gil, S., Wang, Y., Mandla, S., Yee, B., and Radisic, M. (2020). Advanced Strategies for Modulation of the Material-Macrophage Interface. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909331. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909331

De Zuani, M., Paolicelli, G., Zelante, T., Renga, G., Romani, L., Arzese, A., et al. (2018). Mast Cells Respond to Candida Albicans Infections and Modulate Macrophages Phagocytosis of the Fungus. Front. Immunol. 9, 2829. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02829

Defraeye, T., and Martynenko, A. (2018). Future Perspectives for Electrohydrodynamic Drying of Biomaterials. Drying Technology 36, 1–10. doi:10.1080/07373937.2017.1326130

Delavary, B. M., van der Veer, W. M., van Egmond, M., Niessen, F. B., and Beelen, R. H. J. (2011). Macrophages in Skin Injury and Repair. Immunobiology 216, 753–762. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2011.01.001

Dellacherie, M. O., Seo, B. R., and Mooney, D. J. (2019). Macroscale Biomaterials Strategies for Local Immunomodulation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 379–397. doi:10.1038/s41578-019-0106-3

Deng, M., Tan, J., Hu, C., Hou, T., Peng, W., Liu, J., et al. (2020). Modification of PLGA Scaffold by MSC-Derived Extracellular Matrix Combats Macrophage Inflammation to Initiate Bone Regeneration via TGF- β -Induced Protein. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2000353. doi:10.1002/adhm.202000353

Doloff, J. C., Veiseh, O., Vegas, A. J., Tam, H. H., Farah, S., Ma, M., et al. (2017). Colony Stimulating Factor-1 Receptor Is a central Component of the Foreign Body Response to Biomaterial Implants in Rodents and Non-human Primates. Nat. Mater 16, 671–680. doi:10.1038/nmat4866

Donat, C., Thanei, S., and Trendelenburg, M. (2019). Binding of von Willebrand Factor to Complement C1q Decreases the Phagocytosis of Cholesterol Crystals and Subsequent IL-1 Secretion in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 10, 2712. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02712

Dziki, J. L., and Badylak, S. F. (2018). Immunomodulatory Biomaterials. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 6, 51–57. doi:10.1016/j.cobme.2018.02.005

Eke, G., Mangir, N., Hasirci, N., MacNeil, S., and Hasirci, V. (2017). Development of a UV Crosslinked Biodegradable Hydrogel Containing Adipose Derived Stem Cells to Promote Vascularization for Skin Wounds and Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 129, 188–198. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.021

Engler, A. E., Ysasi, A. B., Pihl, R. M. F., Villacorta-Martin, C., Heston, H. M., Richardson, H. M. K., et al. (2020). Airway-Associated Macrophages in Homeostasis and Repair. Cel Rep. 33, 108553. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108553

Eslami-Kaliji, F., Sarafbidabad, M., Rajadas, J., and Mohammadi, M. R. (2020). Dendritic Cells as Targets for Biomaterial-Based Immunomodulation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6, 2726–2739. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01987

Fang, J., Koh, J., Fang, Q., Qiu, H., Archang, M. M., Hasani-Sadrabadi, M. M., et al. (2020). Injectable Drug-Releasing Microporous Annealed Particle Scaffolds for Treating Myocardial Infarction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004307. doi:10.1002/adfm.202004307

Fisher, S. A., Baker, A. E. G., and Shoichet, M. S. (2017). Designing Peptide and Protein Modified Hydrogels: Selecting the Optimal Conjugation Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7416–7427. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b00513

Frejd, F. Y., and Kim, K.-T. (2017). Affibody Molecules as Engineered Protein Drugs. Exp. Mol. Med. 49, e306. doi:10.1038/emm.2017.35

Frossi, B., Mion, F., Sibilano, R., Danelli, L., and Pucillo, C. E. M. (2018). Is it Time for a New Classification of Mast Cells? what Do We Know about Mast Cell Heterogeneity? Immunol. Rev. 282, 35–46. doi:10.1111/imr.12636

Gaharwar, A. K., Singh, I., and Khademhosseini, A. (2020). Engineered Biomaterials for In Situ Tissue Regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 686–705. doi:10.1038/s41578-020-0209-x

Galli, S. J., Gaudenzio, N., and Tsai, M. (2020). Mast Cells in Inflammation and Disease: Recent Progress and Ongoing Concerns. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 38, 49–77. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-071719-094903

Gao, C., Cheng, Q., Wei, J., Sun, C., Lu, S., Kwong, C. H. T., et al. (2020). Bioorthogonal Supramolecular Cell-Conjugation for Targeted Hitchhiking Drug Delivery. Mater. Today 40, 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2020.05.023

Ghasemi, F., Bagheri, H., Barreto, G. E., Read, M. I., and Sahebkar, A. (2019). Effects of Curcumin on Microglial Cells. Neurotox Res. 36, 12–26. doi:10.1007/s12640-019-00030-0

Ghilardi, N., Pappu, R., Arron, J. R., and Chan, A. C. (2020). 30 Years of Biotherapeutics Development-What Have We Learned? Annu. Rev. Immunol. 38, 249–287. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-101619-031510

Glass, Z., Lee, M., Li, Y., and Xu, Q. (2018). Engineering the Delivery System for CRISPR-Based Genome Editing. Trends Biotechnology 36, 173–185. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.11.006

Gnaim, S., and Shabat, D. (2019). Activity-Based Optical Sensing Enabled by Self-Immolative Scaffolds: Monitoring of Release Events by Fluorescence or Chemiluminescence Output. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 2806–2817. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00338

Gonzalez-Fernandez, T., Rathan, S., Hobbs, C., Pitacco, P., Freeman, F. E., Cunniffe, G. M., et al. (2019). Pore-forming Bioinks to Enable Spatio-Temporally Defined Gene Delivery in Bioprinted Tissues. J. Controlled Release 301, 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.03.006

Grim, J. C., Brown, T. E., Aguado, B. A., Chapnick, D. A., Viert, A. L., Liu, X., et al. (2018). A Reversible and Repeatable Thiol-Ene Bioconjugation for Dynamic Patterning of Signaling Proteins in Hydrogels. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 909–916. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.8b00325

Guimarães, C. F., Gasperini, L., Marques, A. P., and Reis, R. L. (2020). The Stiffness of Living Tissues and its Implications for Tissue Engineering. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 351–370. doi:10.1038/s41578-019-0169-1

Haapasalo, K., and Meri, S. (2019). Regulation of the Complement System by Pentraxins. Front. Immunol. 10, 1750. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01750

Han, N., Jiang, B.-G., Zhang, P.-X., Kou, Y.-H., Zhu, Q.-T., Liu, X.-L., et al. (2019). Tissue Engineering for the Repair of Peripheral Nerve Injury. Neural Regen. Res. 14, 51. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.243701

Hannan, R. T., Peirce, S. M., and Barker, T. H. (2017). Fibroblasts: Diverse Cells Critical to Biomaterials Integration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 1223–1232. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00244

He, J., Chen, G., Liu, M., Xu, Z., Chen, H., Yang, L., et al. (2020). Scaffold Strategies for Modulating Immune Microenvironment during Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 108, 110411. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.110411

Healy, A., Berus, J. M., Christensen, J. L., Lee, C., Mantsounga, C., Dong, W., et al. (2020). Statins Disrupt Macrophage Rac1 Regulation Leading to Increased Atherosclerotic Plaque Calcification. Atvb 40, 714–732. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.119.313832

Hedegaard, C. L., Collin, E. C., Redondo-Gómez, C., Nguyen, L. T. H., Ng, K. W., Castrejón-Pita, A. A., et al. (2018). Hydrodynamically Guided Hierarchical Self-Assembly of Peptide-Protein Bioinks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1703716. doi:10.1002/adfm.201703716

Hiew, V. V., Simat, S. F. B., and Teoh, P. L. (2018). The Advancement of Biomaterials in Regulating Stem Cell Fate. Stem Cel Rev Rep 14, 43–57. doi:10.1007/s12015-017-9764-y

Hu, C., Chu, C., Liu, L., Wang, C., Jin, S., Yang, R., et al. (2021). Dissecting the Microenvironment Around Biosynthetic Scaffolds in Murine Skin Wound Healing. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf0787. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf0787

Ibrahim, M., Bond, J., Medina, M. A., Chen, L., Quiles, C., Kokosis, G., et al. (2017). Characterization of the Foreign Body Response to Common Surgical Biomaterials in a Murine Model. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 40, 383–392. doi:10.1007/s00238-017-1308-9

Jain, P., Hung, H.-C., Li, B., Ma, J., Dong, D., Lin, X., et al. (2018). Zwitterionic Hydrogels Based on a Degradable Disulfide Carboxybetaine Cross-Linker. Langmuir 35, 1864–1871. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02100

Jimi, S., Jaguparov, A., Nurkesh, A., Sultankulov, B., and Saparov, A. (2020). Sequential Delivery of Cryogel Released Growth Factors and Cytokines Accelerates Wound Healing and Improves Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 345. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00345

Jin, K., Luo, Z., Zhang, B., and Pang, Z. (2018). Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Inflammation Targeting. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 8, 23–33. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.002

Kamburova, V. S., Nikitana, E. V., Shermatov, S., and Buriev, Z. T. (2017). Genome Editing in Plants: an Overview of Tools and Applications. Int. J. Agron. 2017, 1. doi:10.1155/2017/7315351

Kargozar, S., Mozafari, M., Hamzehlou, S., Brouki Milan, P., Kim, H.-W., and Baino, F. (2019). Bone Tissue Engineering Using Human Cells: a Comprehensive Review on Recent Trends, Current Prospects, and Recommendations. Appl. Sci. 9, 174. doi:10.3390/app9010174

Kempuraj, D., Selvakumar, G. P., Thangavel, R., Ahmed, M. E., Zaheer, S., Kumar, K. K., et al. (2018). Glia Maturation Factor and Mast Cell-dependent Expression of Inflammatory Mediators and Proteinase Activated Receptor-2 in Neuroinflammation. Jad 66, 1117–1129. doi:10.3233/jad-180786

Khare, D., Basu, B., and Dubey, A. K. (2020). Electrical Stimulation and Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 258, 120280. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120280

Kim, J., Bae, W.-G., Kim, Y. J., Seonwoo, H., Choung, H.-W., Jang, K.-J., et al. (2017). Directional Matrix Nanotopography with Varied Sizes for Engineering Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 6, 1700297. doi:10.1002/adhm.201700297

Komi, D. E. A., Khomtchouk, K., and Santa Maria, P. L. (2020). A Review of the Contribution of Mast Cells in Wound Healing: Involved Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Clinic Rev. Allerg Immunol. 58, 298–312. doi:10.1007/s12016-019-08729-w

Kowalski, P. S., Bhattacharya, C., Afewerki, S., and Langer, R. (2018). Smart Biomaterials: Recent Advances and Future Directions. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 3809–3817. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00889

Kumar, S., Nehra, M., Kedia, D., Dilbaghi, N., Tankeshwar, K., and Kim, K.-H. (2020). Nanotechnology-based Biomaterials for Orthopaedic Applications: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 106, 110154. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.110154

Kuo, C.-C., Chiang, A. W., Shamie, I., Samoudi, M., Gutierrez, J. M., and Lewis, N. E. (2018). The Emerging Role of Systems Biology for Engineering Protein Production in CHO Cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 51, 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2017.11.015

Lalitha Sridhar, S., Schneider, M. C., Chu, S., de Roucy, G., Bryant, S. J., and Vernerey, F. J. (2017). Heterogeneity Is Key to Hydrogel-Based Cartilage Tissue Regeneration. Soft Matter 13, 4841–4855. doi:10.1039/c7sm00423k

Lasola, J. J. M., Kamdem, H., McDaniel, M. W., and Pearson, R. M. (2020). Biomaterial-driven Immunomodulation: Cell Biology-Based Strategies to Mitigate Severe Inflammation and Sepsis. Front. Immunol. 11, 1726. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01726

Leach, D. G., Young, S., and Hartgerink, J. D. (2019). Advances in Immunotherapy Delivery from Implantable and Injectable Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 88, 15–31. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.02.016

Lee, H., Han, W., Kim, H., Ha, D.-H., Jang, J., Kim, B. S., et al. (2017). Development of Liver Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioink for Three-Dimensional Cell Printing-Based Liver Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 18, 1229–1237. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01908

Lee, J., Byun, H., Madhurakkat Perikamana, S. K., Lee, S., and Shin, H. (2019). Current Advances in Immunomodulatory Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, e1801106. doi:10.1002/adhm.201801106

Lee, J.-H., Parthiban, P., Jin, G.-Z., Knowles, J. C., and Kim, H.-W. (2021). Materials Roles for Promoting Angiogenesis in Tissue Regeneration. Prog. Mater. Sci. 117, 100732. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100732

Leijten, J., Seo, J., Yue, K., Trujillo-de Santiago, G., Tamayol, A., Ruiz-Esparza, G. U., et al. (2017). Spatially and Temporally Controlled Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 119, 1–35. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2017.07.001

Li, R., Serrano, J. C., Xing, H., Lee, T. A., Azizgolshani, H., Zaman, M., et al. (2018). Interstitial Flow Promotes Macrophage Polarization toward an M2 Phenotype. MBoC 29, 1927–1940. doi:10.1091/mbc.e18-03-0164

Li, X., Zhang, C., Haggerty, A. E., Yan, J., Lan, M., Seu, M., et al. (2020). The Effect of a Nanofiber-Hydrogel Composite on Neural Tissue Repair and Regeneration in the Contused Spinal Cord. Biomaterials 245, 119978. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119978

Liang, R., Fang, D., Lin, W., Wang, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, Y., et al. (2018). Macrophage Polarization in Response to Varying Pore Sizes of 3D Polyurethane Scaffolds. J Biomed. Nanotechnol 14, 1744–1760. doi:10.1166/jbn.2018.2629

Liu, G., and Yang, H. (2013). Modulation of Macrophage Activation and Programming in Immunity. J. Cel. Physiol. 228, 502–512. doi:10.1002/jcp.24157

Liu, Y., Yang, Z., Wang, L., Sun, L., Kim, B. Y. S., Jiang, W., et al. (2021). Spatiotemporal Immunomodulation Using Biomimetic Scaffold Promotes Endochondral Ossification-Mediated Bone Healing. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100143. doi:10.1002/advs.202100143

Liu, Z., Tang, M., Zhao, J., Chai, R., and Kang, J. (2018). Looking into the Future: Toward Advanced 3D Biomaterials for Stem-Cell-Based Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705388. doi:10.1002/adma.201705388

Lock, A., Cornish, J., and Musson, D. S. (2019). The Role of In Vitro Immune Response Assessment for Biomaterials. Jfb 10, 31. doi:10.3390/jfb10030031

Ma, Y., Lin, M., Huang, G., Li, Y., Wang, S., Bai, G., et al. (2018). 3D Spatiotemporal Mechanical Microenvironment: A Hydrogel-Based Platform for Guiding Stem Cell Fate. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705911. doi:10.1002/adma.201705911

Mahon, O. R., Browe, D. C., Gonzalez-Fernandez, T., Pitacco, P., Whelan, I. T., Von Euw, S., et al. (2020). Nano-particle Mediated M2 Macrophage Polarization Enhances Bone Formation and MSC Osteogenesis in an IL-10 Dependent Manner. Biomaterials 239, 119833. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119833

Mali, P., and Cheng, L. (2012). Concise Review: Human Cell Engineering: Cellular Reprogramming and Genome Editing. Stem cells 30, 75–81. doi:10.1002/stem.735

Mariani, E., Lisignoli, G., Borzì, R. M., and Pulsatelli, L. (2019). Biomaterials: Foreign Bodies or Tuners for the Immune Response? Ijms 20, 636. doi:10.3390/ijms20030636

Martin, P., and Leibovich, S. J. (2005). Inflammatory Cells during Wound Repair: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Trends Cel Biol. 15, 599–607. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002

Martinez, J. O., Evangelopoulos, M., Brozovich, A. A., Bauza, G., Molinaro, R., Corbo, C., et al. (2021). Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Mediated Treatment of Local and Systemic Inflammation through the Triggering of an Anti-inflammatory Response. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2002997. doi:10.1002/adfm.202002997

Maximiano, W. M. A., da Silva, E. Z. M., Santana, A. C., de Oliveira, P. T., Jamur, M. C., and Oliver, C. (2017). Mast Cell Mediators Inhibit Osteoblastic Differentiation and Extracellular Matrix Mineralization. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 65, 723–741. doi:10.1369/0022155417734174

Mendes, B. B., Gómez-Florit, M., Babo, P. S., Domingues, R. M., Reis, R. L., and Gomes, M. E. (2018). Blood Derivatives Awaken in Regenerative Medicine Strategies to Modulate Wound Healing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 129, 376–393. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.12.018

Metje-Sprink, J., Menz, J., Modrzejewski, D., and Sprink, T. (2019). DNA-free Genome Editing: Past, Present and Future. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1957. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01957

Mohammadinejad, R., Shavandi, A., Raie, D. S., Sangeetha, J., Soleimani, M., Shokrian Hajibehzad, S., et al. (2019). Plant Molecular Farming: Production of Metallic Nanoparticles and Therapeutic Proteins Using green Factories. Green. Chem. 21, 1845–1865. doi:10.1039/c9gc00335e

Moncion, A., Lin, M., O'Neill, E. G., Franceschi, R. T., Kripfgans, O. D., Putnam, A. J., et al. (2017). Controlled Release of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor for Angiogenesis Using Acoustically-Responsive Scaffolds. Biomaterials 140, 26–36. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.012

Moreira, H. R., Raftery, R. M., da Silva, L. P., Cerqueira, M. T., Reis, R. L., Marques, A. P., et al. (2021). In Vitro vascularization of Tissue Engineered Constructs by Non-viral Delivery of Pro-angiogenic Genes. Biomater. Sci. 9, 2067–2081. doi:10.1039/d0bm01560a

Mukherjee, S., Darzi, S., Paul, K., Cousins, F. L., Werkmeister, J. A., and Gargett, C. E. (2020). Electrospun Nanofiber Meshes with Endometrial MSCs Modulate Foreign Body Response by Increased Angiogenesis, Matrix Synthesis, and Anti-inflammatory Gene Expression in Mice: Implication in Pelvic Floor. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 353. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00353

Muñoz-Rojas, A. R., Kelsey, I., Pappalardo, J. L., Chen, M., and Miller-Jensen, K. (2021). Co-stimulation with Opposing Macrophage Polarization Cues Leads to Orthogonal Secretion Programs in Individual Cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 301. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20540-2

Mushtaq, M., Sakina, A., Wani, S. H., Shikari, A. B., Tripathi, P., Zaid, A., et al. (2019). Harnessing Genome Editing Techniques to Engineer Disease Resistance in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 550. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00550

Nakkala, J. R., Li, Z., Ahmad, W., Wang, K., and Gao, C. (2021). Immunomodulatory Biomaterials and Their Application in Therapies for Chronic Inflammation-Related Diseases. Acta Biomater. 123, 1–30. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2021.01.025

Nakkala, J. R., Yao, Y., Zhai, Z., Duan, Y., Zhang, D., Mao, Z., et al. (2021). Dimethyl Itaconate-Loaded Nanofibers Rewrite Macrophage Polarization, Reduce Inflammation, and Enhance Repair of Myocardic Infarction. Small 17, 2006992. doi:10.1002/smll.202006992

Nelson, C. E., and Gersbach, C. A. (2016). Engineering Delivery Vehicles for Genome Editing. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 7, 637–662. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-080615-034711

Ng, A. H. M., Khoshakhlagh, P., Rojo Arias, J. E., Pasquini, G., Wang, K., Swiersy, A., et al. (2021). A Comprehensive Library of Human Transcription Factors for Cell Fate Engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 510–519. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0742-6

Nguyen, T. L., Cha, B. G., Choi, Y., Im, J., and Kim, J. (2020). Injectable Dual-Scale Mesoporous Silica Cancer Vaccine Enabling Efficient Delivery of Antigen/adjuvant-Loaded Nanoparticles to Dendritic Cells Recruited in Local Macroporous Scaffold. Biomaterials 239, 119859. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119859

Nourian Dehkordi, A., Mirahmadi Babaheydari, F., Chehelgerdi, M., and Raeisi Dehkordi, S. (2019). Skin Tissue Engineering: Wound Healing Based on Stem-Cell-Based Therapeutic Strategies. Stem Cel Res Ther 10, 111–120. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1212-2

Olingy, C. E., Dinh, H. Q., and Hedrick, C. C. (2019). Monocyte Heterogeneity and Functions in Cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 106, 309–322. doi:10.1002/jlb.4ri0818-311r

Oliva, N., and Almquist, B. D. (2020). Spatiotemporal Delivery of Bioactive Molecules for Wound Healing Using Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 161-162, 22–41. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.021

Olivera, A., Beaven, M. A., and Metcalfe, D. D. (2018). Mast Cells Signal Their Importance in Health and Disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 381–393. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.034

Ooi, H. W., Hafeez, S., Van Blitterswijk, C. A., Moroni, L., and Baker, M. B. (2017). Hydrogels that Listen to Cells: a Review of Cell-Responsive Strategies in Biomaterial Design for Tissue Regeneration. Mater. Horiz. 4, 1020–1040. doi:10.1039/c7mh00373k

Orapiriyakul, W., Tsimbouri, M. P., Childs, P., Campsie, P., Wells, J., Fernandez-Yague, M. A., et al. (2020). Nanovibrational Stimulation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Induces Therapeutic Reactive Oxygen Species and Inflammation for Three-Dimensional Bone Tissue Engineering. ACS Nano 14, 10027–10044. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c03130

Ortiz, M., de Sa Coutinho, D., Ciambarella, B. T., de Souza, E. T., D’Almeida, A. P. L., Durli, T. L., et al. (2020). Intranasal Administration of Budesonide-Loaded Nanocapsule Microagglomerates as an Innovative Strategy for Asthma Treatment. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 10, 1700–1715. doi:10.1007/s13346-020-00813-5

Ozpinar, E. W., Frey, A. L., Cruse, G., and Freytes, D. O. (2021). Mast Cell-Biomaterial Interactions and Tissue Repair. Tissue Eng. Part B: Rev. 27, 590–603. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2020.0275

Ozpinar, E. W., Frey, A. L., Cruse, G., and Freytes, D. O. (2021). Mast Cell–Biomaterial Interactions and Tissue Repair. Reviews: Tissue Engineering Part B.

Panichi, V., Migliori, M., De Pietro, S., Taccola, D., Andreini, B., Metelli, M. R., et al. (2000). The Link of Biocompatibility to Cytokine Production. Kidney Int. 58, S96–S103. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07612.x

Park, J., Han, S., and Hanawa, T. (2018). Effects of Surface Nanotopography and Calcium Chemistry of Titanium Bone Implants on Early Blood Platelet and Macrophage Cell Function. Biomed. Research International 2018, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2018/1362958

Park, K., Lee, Y., and Seo, J. (2018). Recent Advances in High-Throughput Platforms with Engineered Biomaterial Microarrays for Screening of Cell and Tissue Behavior. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24, 5458–5470. doi:10.2174/1381612825666190207093438

Peng, L. H., Xu, X. H., Huang, Y. F., Zhao, X. L., Zhao, B., Cai, S. Y., et al. (2020). Self-Adaptive All-In-One Delivery Chip for Rapid Skin Nerves Regeneration by Endogenous Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001751. doi:10.1002/adfm.202001751

Perez, J. R., Kouroupis, D., Li, D. J., Best, T. M., Kaplan, L., and Correa, D. (2018). Tissue Engineering and Cell-Based Therapies for Fractures and Bone Defects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6, 105. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2018.00105

Petrosyan, A., Da Sacco, S., Tripuraneni, N., Kreuser, U., Lavarreda-Pearce, M., Tamburrini, R., et al. (2017). A Step towards Clinical Application of Acellular Matrix: A Clue from Macrophage Polarization. Matrix Biol. 57-58, 334–346. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2016.08.009

Primavera, R., Kevadiya, B. D., Swaminathan, G., Wilson, R. J., De Pascale, A., Decuzzi, P., et al. (2020). Emerging Nano- and Micro-technologies Used in the Treatment of Type-1 Diabetes. Nanomaterials 10, 789. doi:10.3390/nano10040789

Pugliese, R., and Gelain, F. (2017). Peptidic Biomaterials: from Self-Assembling to Regenerative Medicine. Trends Biotechnology 35, 145–158. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.09.004

Ragipoglu, D., Dudeck, A., Haffner-Luntzer, M., Voss, M., Kroner, J., Ignatius, A., et al. (2020). The Role of Mast Cells in Bone Metabolism and Bone Disorders. Front. Immunol. 11, 163. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00163

Rahman, S. M., Eichinger, C. D., and Hlady, V. (2018). Effects of Upstream Shear Forces on Priming of Platelets for Downstream Adhesion and Activation. Acta Biomater. 73, 228–235. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.002

Rehmann, M. S., Skeens, K. M., Kharkar, P. M., Ford, E. M., Maverakis, E., Lee, K. H., et al. (2017). Tuning and Predicting Mesh Size and Protein Release from Step Growth Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 18, 3131–3142. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00781

Reid, M. S., Le, X. C., and Zhang, H. (2018). Exponential Isothermal Amplification of Nucleic Acids and Assays for Proteins, Cells, Small Molecules, and Enzyme Activities: an EXPAR Example. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11856–11866. doi:10.1002/anie.201712217

Riley, L., Schirmer, L., and Segura, T. (2019). Granular Hydrogels: Emergent Properties of Jammed Hydrogel Microparticles and Their Applications in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 60, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2018.11.001

Rosales, A. M., Vega, S. L., DelRio, F. W., Burdick, J. A., and Anseth, K. S. (2017). Hydrogels with Reversible Mechanics to Probe Dynamic Cell Microenvironments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12132–12136. doi:10.1002/anie.201705684

Rose, J. C., and De Laporte, L. (2018). Hierarchical Design of Tissue Regenerative Constructs. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, 1701067. doi:10.1002/adhm.201701067

Sadtler, K., Estrellas, K., Allen, B. W., Wolf, M. T., Fan, H., Tam, A. J., et al. (2016). Developing a Pro-regenerative Biomaterial Scaffold Microenvironment Requires T Helper 2 Cells. Science 352, 366–370. doi:10.1126/science.aad9272

Sadtler, K., Singh, A., Wolf, M. T., and Wang, X. (2016). Design, Clinical Translation and Immunological Response of Biomaterials in Regenerative Medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16040. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2016.40

Sammarco, G., Varricchi, G., Ferraro, V., Ammendola, M., De Fazio, M., Altomare, D. F., et al. (2019). Mast Cells, Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis in Human Gastric Cancer. Ijms 20, 2106. doi:10.3390/ijms20092106

Schmalz, G., and Galler, K. M. (2017). Biocompatibility of Biomaterials - Lessons Learned and Considerations for the Design of Novel Materials. Dental Mater. 33, 382–393. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2017.01.011

Seo, J., Shin, J.-Y., Leijten, J., Jeon, O., Camci-Unal, G., Dikina, A. D., et al. (2018). High-throughput Approaches for Screening and Analysis of Cell Behaviors. Biomaterials 153, 85–101. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.022

Shadish, J. A., Benuska, G. M., and DeForest, C. A. (2019). Bioactive Site-Specifically Modified Proteins for 4D Patterning of Gel Biomaterials. Nat. Mater. 18, 1005–1014. doi:10.1038/s41563-019-0367-7

Sharifi, F., Htwe, S. S., Righi, M., Liu, H., Pietralunga, A., Yesil-Celiktas, O., et al. (2019). A Foreign Body Response-On-A-Chip Platform. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1801425. doi:10.1002/adhm.201801425

Sharifi, S., Hajipour, M. J., Gould, L., and Mahmoudi, M. (2020). Nanomedicine in Healing Chronic Wounds: Opportunities and Challenges. Michigan: Molecular Pharmaceutics.

Sharma, A. K., Arya, A., Sahoo, P. K., and Majumdar, D. K. (2016). Overview of Biopolymers as Carriers of Antiphlogistic Agents for Treatment of Diverse Ocular Inflammations. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 67, 779–791. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.060

Sharma, P., Kumar, A., Dey, A. D., Behl, T., and Chadha, S. (2021). Stem Cells and Growth Factors-Based Delivery Approaches for Chronic Wound Repair and Regeneration: A Promise to Heal from within. Life Sci. 268, 118932. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118932

Shen, X., Zhang, Y., Gu, Y., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., Li, B., et al. (2016). Sequential and Sustained Release of SDF-1 and BMP-2 from Silk Fibroin-Nanohydroxyapatite Scaffold for the Enhancement of Bone Regeneration. Biomaterials 106, 205–216. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.023

Sica, A., and Bronte, V. (2007). Altered Macrophage Differentiation and Immune Dysfunction in Tumor Development. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1155–1166. doi:10.1172/jci31422

Siebert, L., Luna-Cerón, E., García-Rivera, L. E., Oh, J., Jang, J., Rosas-Gómez, D. A., et al. (2021). Light-Controlled Growth Factors Release on Tetrapodal ZnO-Incorporated 3D-Printed Hydrogels for Developing Smart Wound Scaffold. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007555. doi:10.1002/adfm.202007555

Simeon, R., and Chen, Z. (2018). In Vitro-engineered Non-antibody Protein Therapeutics. Protein Cell 9, 3–14. doi:10.1007/s13238-017-0386-6

Soundara Rajan, T., Gugliandolo, A., Bramanti, P., and Mazzon, E. (2020). Tunneling Nanotubes-Mediated Protection of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: An Update from Preclinical Studies. Ijms 21, 3481. doi:10.3390/ijms21103481

Soundararajan, M., and Kannan, S. (2018). Fibroblasts and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Two Sides of the Same coin? J. Cel Physiol 233, 9099–9109. doi:10.1002/jcp.26860

Sridharan, R., Cameron, A. R., Kelly, D. J., Kearney, C. J., and O’Brien, F. J. (2015). Biomaterial Based Modulation of Macrophage Polarization: a Review and Suggested Design Principles. Mater. Today 18, 313–325. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2015.01.019

Su, G., Ma, X., and Wei, H. (2020). Multiple Biological Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in Lung Injury and Inflammation Microenvironment. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 1–6. doi:10.1155/2020/5608382

Sultankulov, B., Berillo, D., Sultankulova, K., Tokay, T., and Saparov, A. (2019). Progress in the Development of Chitosan-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Biomolecules 9, 470. doi:10.3390/biom9090470

Takeuchi, T., Kitayama, Y., Sasao, R., Yamada, T., Toh, K., Matsumoto, Y., et al. (2017). Molecularly Imprinted Nanogels Acquire Stealth In Situ by Cloaking Themselves with Native Dysopsonic Proteins. Angew. Chem. 129, 7194–7198. doi:10.1002/ange.201700647

Tang, C., Hobbs, B., and Amer, A. M. (2018). Development of an Immune-Pathology Informed Radiomics Model for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Scientific Rep. 8, 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20471-5

Tanneberger, A. M., Al-Maawi, S., Herrera-Vizcaíno, C., Orlowska, A., Kubesch, A., Sader, R., et al. (2021). Multinucleated Giant Cells within the In Vivo Implantation Bed of a Collagen-Based Biomaterial Determine its Degradation Pattern. Clin. Oral Invest. 25, 859–873. doi:10.1007/s00784-020-03373-7

Teixeira, S. P. B., Domingues, R. M. A., Shevchuk, M., Gomes, M. E., Peppas, N. A., and Reis, R. L. (2020). Biomaterials for Sequestration of Growth Factors and Modulation of Cell Behavior. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909011. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909011

Thangam, E. B., Jemima, E. A., Singh, H., Baig, M. S., Khan, M., Mathias, C. B., et al. (2018). The Role of Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Mast Cell-Mediated Allergy and Inflammation: the hunt for New Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 9, 1873. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01873

Turnbull, G., Clarke, J., Picard, F., Riches, P., Jia, L., Han, F., et al. (2018). 3D Bioactive Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioactive Mater. 3, 278–314. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.10.001

Tylek, T., Blum, C., Hrynevich, A., Schlegelmilch, K., Schilling, T., Dalton, P. D., et al. (2020). Precisely Defined Fiber Scaffolds with 40 μm Porosity Induce Elongation Driven M2-like Polarization of Human Macrophages. Biofabrication 12, 025007. doi:10.1088/1758-5090/ab5f4e

Tzu-Chieh, T., Bolin, A., Yuanyuan, H., and Sangita, V. (2021). Materials Design by Synthetic Biology. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 332–350. doi:10.1038/s41578-020-00265-w

Vassey, M. J., Figueredo, G. P., Scurr, D. J., Vasilevich, A. S., Vermeulen, S., Carlier, A., et al. (2020). Immune Modulation by Design: Using Topography to Control Human Monocyte Attachment and Macrophage Differentiation. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903392. doi:10.1002/advs.201903392

Vats, S., Kumawat, S., Kumar, V., Patil, G. B., Joshi, T., Sonah, H., et al. (2019). Genome Editing in Plants: Exploration of Technological Advancements and Challenges. Cells 8, 1386. doi:10.3390/cells8111386

Veiseh, O., Doloff, J. C., Ma, M., Vegas, A. J., Tam, H. H., Bader, A. R., et al. (2015). Size- and Shape-dependent Foreign Body Immune Response to Materials Implanted in Rodents and Non-human Primates. Nat. Mater 14, 643–651. doi:10.1038/nmat4290

Veiseh, O., and Vegas, A. J. (2019). Domesticating the Foreign Body Response: Recent Advances and Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 144, 148–161. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2019.08.010

Vishwakarma, A., Bhise, N. S., Evangelista, M. B., Rouwkema, J., Dokmeci, M. R., Ghaemmaghami, A. M., et al. (2016). Engineering Immunomodulatory Biomaterials to Tune the Inflammatory Response. Trends Biotechnology 34, 470–482. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.03.009

Wang, C., Ye, Y., Hu, Q., Bellotti, A., and Gu, Z. (2017). Tailoring Biomaterials for Cancer Immunotherapy: Emerging Trends and Future Outlook. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606036. doi:10.1002/adma.201606036

Wang, L., Chen, Z., Yan, Y., He, C., and Li, X. (2021). Fabrication of Injectable Hydrogels from Silk Fibroin and Angiogenic Peptides for Vascular Growth and Tissue Regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 418, 129308. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129308

Wang, R., Liu, W., Du, M., Yang, C., Li, X., and Yang, P. (2018). The Differential Effect of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor and Stromal Cell-derived F-actor-1 P-retreatment on B-one morrow M-esenchymal S-tem C-ells O-steogenic D-ifferentiation P-otency. Mol. Med. Rep. 17, 3715–3721. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.8316

Wei, P., Xu, Y., Zhang, H., and Wang, L. (2021). Continued Sustained Insulin-Releasing PLGA Nanoparticles Modified 3D-Printed PCL Composite Scaffolds for Osteochondral Repair. Chem. Eng. J. 422, 130051. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.130051