- 1Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2Forbruksforskningsinstituttet SIFO, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Introduction: Societies place a responsibility on individuals to pay what they owe on time, establishing a coercive apparatus for debt collection and enforcement when they do not, coupled with consumer protection and debt resolution measures to protect the vulnerable.

Methods: An analysis of in-depth interviews with 28 people with both payment difficulties and vulnerabilities from ill-health, using Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory to explore the experiences of vulnerable defaulters as they try to exercise the personal responsibility placed on them by society.

Results: It finds that they encounter barriers in exercising the personal responsibility which primarily arise in encounters with inflexible and bureaucratic routines – of creditors, debt enforcement agents and even money advisers whose role is to help vulnerable people. These systematically undermine defaulters' self-efficacy, and leaving them facing prolonged periods of payment difficulties.

Discussion: The findings are discussed in the light of Bandura's Theory and lessons drawn for the policies and practices of creditors, debt enforcement bodies, and money advisers.

Introduction

In modern societies, managing a household budget can be challenging, especially when incomes are inadequate for the commitments households must cover. This is attenuated when there are other vulnerabilities, such as poor mental health. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that a large body of research consistently shows a strong link between the incidence of payment difficulties and both low income and poor health.

In all jurisdictions, individuals are expected to adhere to the payment norm, and if payment problems arise, they are expected to negotiate with their creditors and find solutions within an institutionalized framework of individual and collective responsibilities. States typically assume collective responsibility by establishing a coercive apparatus for debt collection and debt enforcement by creditors, where much of the responsibility is placed on the individual. At its simplest, this means accepting moral responsibility to pay what is owed and balancing the books to do so. This becomes far more complicated when the books cannot be balanced, whether through lack of income or lack of mental capacity. Typically, individuals start to “rob Peter to pay Paul” to fulfill the responsibility placed on them, which can rapidly lead to multiple arrears. At this point, behaving responsibly is a very complex process involving mapping how much is owed to whom, contacting each creditor to explain the situation and negotiating a way forward that is acceptable to all of them. This requires not only having the resources to make repayment offers to creditors but also the agency and, as importantly, the self-efficacy to compile the information needed and negotiate with creditors, who often hold the upper hand.

Consequently, the need for consumer protection is also generally recognized and includes market regulation, a social safety net of money advice, and opportunities for debt settlement. Creditors, enforcement agencies, such as bailiffs, and money advisers ought reasonably to be expected to facilitate a resolution to the payment difficulties faced by vulnerable people. Yet analysis of registry data of defaulters in Norway shows that those with mental health problems were more likely to face debt enforcement than other defaulters and less likely to obtain debt settlement (Bakkeli and Drange, 2024). And regulators have become aware of the need for greater protection for vulnerable defaulters (Graham, 2023).

The focus of this article is to provide an understanding of why people with vulnerabilities experience prolonged periods of payment problems and are unable to exercise the personal responsibility society places on them. To do this we apply Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory and focus on the role that self-efficacy plays.

Conceptual framework

An initial reading and indexing of the 28 interview transcripts showed clearly that vulnerable defaulters struggled to exercise the responsibility that society places on them to find solutions to their payment problems, negotiating with creditors and handling the procedures of debt enforcement and debt resolution. At the heart of their difficulties was a sense that the odds were stacked against them and that they felt unable to do what was needed to exercise the responsibility placed on them. There are two psychological concepts that potentially come close to what they were expressing: Locus of Control (Rotter, 1954) and Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977).

Locus of control refers to the degree to which an individual feels a sense of agency or control over events in their life. At one extreme someone with an internal locus of control will believe that the things that happen to them are greatly influenced by their own abilities, actions, or mistakes. A person with an external locus of control will tend to feel that other forces—such as chance, environmental factors, or the actions of others—control events in their lives. In contrast self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their ability (or inability) to perform an action and achieve their desired outcome. This affects whether a behavior is initiated, the amount of effort expended on it and how long the effort is sustained in the face of obstacles. Someone with low self-efficacy is inclined to see obstacles as threats, has a low level of belief in their ability to succeed, internalizes failure, may engage in erratic and unpredictable behavior and is inclined to give up. In contrast, a person with high self-efficacy tends to see obstacles as challenges to overcome, attributes failure to external factors and ultimately recovers from failure.

Although research has shown that these are two quite distinct concepts, in practice they are closely related (Skinner, 1996). So, someone with an internal locus of control will often exhibit a high level of self-efficacy when attempting to perform a task. And, to a degree, that was reflected in the narratives of our respondents. Overall, though, self-efficacy appeared to be the stronger and more pervasive of the two influences and consequently, it became the focus of the analysis.

In the decades since his initial publication, Bandura has honed the concept in a long series of publications, and it has inspired a large body of research across disciplines. In a review of this research in 2023, Bandura and Locke (2003, p. 87) conclude that the evidence “is consistent in showing that efficacy beliefs contribute significantly to the level of motivation and performance”. Moreover, an individual's level of self-efficacy is not fixed and “Efficacy beliefs predict not only the behavioral functioning but also changes in functioning in individuals at different levels of efficacy over time and even variation within the same individual in the tasks performed and those shunned or attempted but failed” (Bandura and Locke, 2003, p. 87). This too accorded with the accounts of our respondents.

Bandura (1986) incorporated self-efficacy as a key element in his Social Cognitive Theory. Initially developed in the context of learning, this theory has been used widely across the social sciences and especially in understanding health behaviors. Social Cognitive Theory proposes that three elements—personal factors, environmental factors and behavior —interact as a dynamic and reciprocal triad, with the relative influence of each factor varying with circumstances, individuals and activities. Belief in one's personal efficacy, or “self-efficacy” is seen as central to the personal factors—and to human agency.

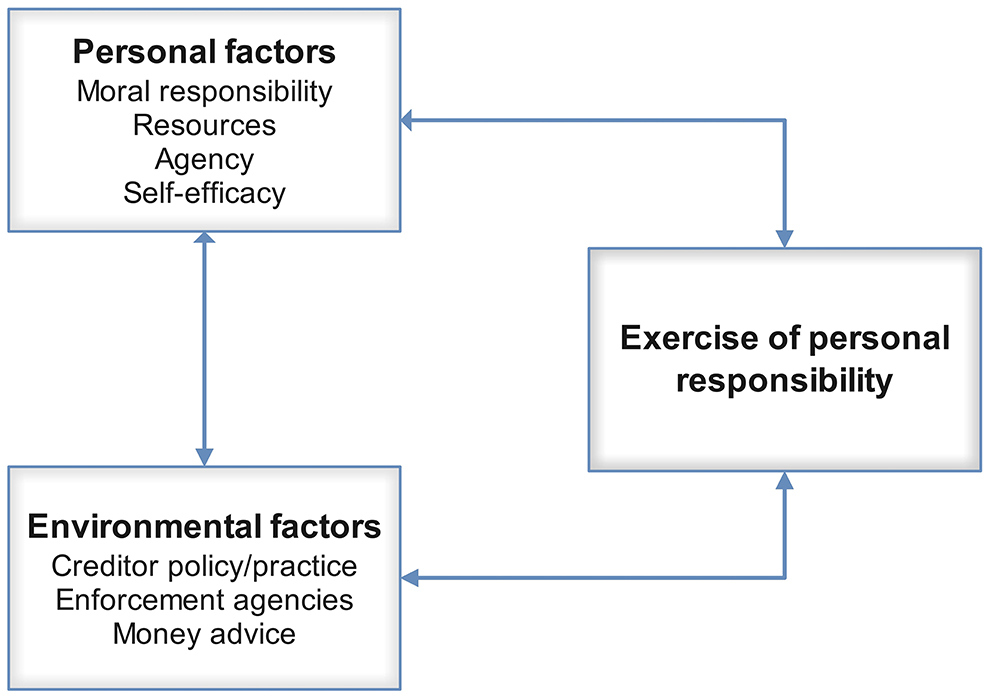

Figure 1 applies Social Cognitive Theory theory to the exercise of personal responsibility. Here, the three elements are the exercise of personal responsibility, environmental factors (policy and practice of creditors, enforcement agencies, and money advisers, who are the agents of collective responsibility), and personal factors (acceptance of moral responsibility, resources, agency, and self-efficacy). Of these, self-efficacy is seen as playing a pivotal role in determining the efforts defaulters make to reach a payment agreement with creditors and their persistence with these efforts when they are either unsuccessful in reaching an agreement they can sustain or fail to get help when they seek it. We hypothesize that, as suggested above, the relative influence of these elements on one another may not be equal and will vary both between individuals and over time. This broad perspective is particularly important when individuals are seeking to exercise individual responsibility to pay their creditors, but debt collection and enforcement processes are largely under the control of creditors and enforcement agencies.

Figure 1. Bandura's theory of social cognition applied to the exercise of personal responsibility to pay one's creditors.

In this article, we use this framework to explore the experiences of vulnerable defaulters as they attempt to exercise the personal responsibility placed on them by society, the barriers they encounter and the extent to which they are protected by the instruments of consumer protection. In doing so, we focus particularly on the role played by self-efficacy—how it operates at the individual level, how it changes over time, what influences those changes and how it affects both behaviors and outcomes as individuals try to exercise personal responsibility.

Our research question is:

What role does self-efficacy play when defaulters with vulnerabilities seek to exercise the personal responsibility that society places on them to adhere to the payment norm?

Previous research

It is well-established in the research literature that low-income, labor market marginalization, poor health and mental health challenges are inextricably linked to create multiple vulnerabilities (see Richardson et al., 2017) and are, in turn, strongly correlated with payment difficulties (see Davydoff et al., 2008; Fitch et al., 2011; Meltzer et al., 2013; Holkar, 2017; Richardson et al., 2017; Hiilamo, 2018; Guan et al., 2022). Meltzer et al. (2013) also found that the incidence of mental health problems was positively linked to the severity of payment difficulties—from 32.3 per cent for those with payment problems on one commitment to 54.3 per cent for those with three or more. Moreover, the links between payment difficulties and poor health have been shown to be bi-directional, suggesting a “vicious cycle” whereby poor health causes and exacerbates financial difficulties, and these financial difficulties, in turn, affect both physical and mental health (Lyons and Yilmazer, 2005; Balmer et al., 2006; Ahlström and Edström, 2014; Richardson et al., 2017; Hiilamo, 2018). And preliminary research in Norway using regression analysis has shown that defaulters who have mental health problems or are marginalized in the labor market are more likely than other defaulters (all other things being equal) to experience debt enforcement and less likely to get debt resolution (Bakkeli and Drange, 2024).

Personal factors: self-efficacy, mental health, and incomes

Low self-efficacy is commonplace among people with specific mental health problems and those who live on low incomes. It is associated with conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Newark et al., 2016), Bipolar Disorder (Smith et al., 2020), and personality disorders in general (Heiland and Veilleux, 2021) as well as with feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Heffernan, 1988; Burgogne, 1990; Krause and Baker, 1992; Mates and Allison, 1992; Ennis et al., 2000).

A review of psychological literature also found that low self-efficacy is related to poverty. Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) proposed that poverty induces a “scarcity mindset,” which leads poor people into sub-optimal decisions and behaviors and is quite possibly mediated through low self-efficacy. Links between shame and low self-efficacy have been demonstrated in the context of poverty—especially where poverty is stigmatized (Fall and Hewstone, 2015).

Qualitative studies report that feelings of shame and self-blame were also widespread among people with payment problems, indicating a high level of acceptance of moral responsibility to pay what they owed (see e.g., Poppe, 2008; Collard et al., 2012; Collard, 2013; Waldron and Redmond, 2016; Sweet et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2020). This was reinforced both by the tone and content of creditors' communications (Collard, 2013; Waldron and Redmond, 2016) and by popular television reality shows where “experts” examine in detail the finances and mistakes of individual consumers in financial difficulty (Türken et al., 2015). Significantly, when stigmatizing narratives—such as those promulgated by reality TV shows—become internalized as shame, they corrode self-efficacy (Corrigan, 1998; Livingston and Boyd, 2010; Corrigan and Rao, 2012; Heartward Strategic, 2022).

A number of quantitative studies have also shown clear links between payment problems and the related concepts of self-efficacy and locus of control.1 Mewse et al. (2010) found that both self-efficacy and locus of control greatly improved the predictability of logistic regression models of serious payment difficulties. Later research demonstrated that having a high financial locus of control had both a small direct effect on keeping up with payments on current commitments, all other things being equal, and a larger indirect effect through behaviors such as controlled spending, saving and constrained borrowing that were also important determinants of financial wellbeing (Kempson and Poppe, 2018). Dare et al. (2023) similarly found that financial self-efficacy was strongly positively related to financial wellbeing both directly and via positive financial behavior. Significantly, locus of control has been shown to change and become less internal, following a negative financial shock (Jetter and Kristoffersen, 2018).

Previous research also provides insights into the mechanisms at work. People are more likely to remain passive and fail to follow up on their intentions if they experience low control (Sheeran, 2002; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2011) and are more likely to procrastinate tasks when they have low self-efficacy about solving them (Steel, 2007). So, it is no surprise that both self-efficacy and locus of control have been shown to influence the actions people take when they experience payment difficulties. Low self-efficacy inhibited people from engaging with creditors to “advocate for their best interests” (Heartward Strategic, 2022). Notably, Gladstone et al. (2021) identified a vicious circle where shame and associated low self-efficacy induced financial withdrawal, which, in turn, increased the likelihood of counterproductive financial decisions, which deepened payment problems.

Conversely, individuals with high self-efficacy were more likely to take precautions that mitigated financial shocks from job loss or illness and were less likely to default on their bills and credit payments (Kuhnen and Melzer, 2018). Higher financial self-efficacy and greater financial internal locus of control were also found to have a positive effect on both engagement with creditors (Mewse et al., 2010) and seeking advice when enforcement action was taken by creditors (Mewse et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014). On the other hand, Rendell et al. (2021) showed, however, that individuals who had a high internal locus of control were more likely to undertake high-risk strategies, such as borrowing further, when unable to meet all their commitments.

Environmental factors: creditors

Creditors can differ widely in their arrears management and debt recovery practices and, consequently, the extent to which they place responsibility on the individual. A Norwegian study found wide variations between types of creditors in their willingness to negotiate payment plans with defaulters (Poppe and Kempson, 2023). Qualitative research in the UK similarly found that some creditors were far more responsive to defaulters' needs than others (Collard and Davies, 2018) and that while some looked for “short-term fixes,” others sought to put sustainable solutions in place (Davies et al., 2016). Investigating this in more detail, Dominy and Kempson (2003) identified three broad approaches among UK creditors:

• One-size-fits-all approach: that adopts standard arrears management and debt recovery practices regardless of the circumstances of consumers and places all the responsibility on the consumer to manage their arrears.

• Hard business approach: that attempts to differentiate between the circumstances of different groups of consumers and adjust their arrears management and debt recovery processes to maximize the likelihood of debt recovery at the lowest possible cost.

• Holistic approach: that seeks to adapt arrears management and debt recovery practices to consumers' individual circumstances. It, therefore, accepts some of the responsibility to rehabilitate consumers in default—including referring them to other sources of help where appropriate.

Reflecting these differences in approach, research by the Norwegian financial services regulator identified some firms who made very large numbers of calls to individual customers in default that “will contribute to increased pressure on the debtor both daily and over time” and that limited forbearance was used (Finanstilsynet, 2022).

Research has also shown that defaulters had realistic repayment offers rejected by their creditors and that they either suggested or accepted unrealistic and unsustainable repayment arrangements to demonstrate that they were behaving responsibly (Collard et al., 2012; Collard, 2013; Ofgem, 2021). Indeed, only 36 per cent of defaulters in Norway who contacted a creditor were able to agree to either a payment deferral or a new payment plan that they could afford (Poppe and Kempson, 2023).

Failed attempts to negotiate with creditors commonly led to a loss of self-efficacy, resulting in defaulters engaging in creditor avoidance—neither contacting their creditors nor responding to their communications (Collard et al., 2012; Custers, 2015, 2017; Waldron and Redmond, 2016; Custers and Stephen, 2019; Heartward Strategic, 2022).

However, a more empathetic approach by creditors can positively combat creditor avoidance and facilitate a resolution of payment difficulties. Working with a municipality department responsible for recovering welfare over-payments, Dewies et al. (2022) investigated the impact of a recovery letter redrafted in line with the principles of scarcity theory and nudge to make it seem less threatening and emphasize the need to make contact. Compared with the existing standard letter, the revised one led to modest increases in contact by defaulters and in the number of payment arrangements made.

Similarly, research with customers of a bank that was committed to overcoming customer resistance to making contact when they faced payment difficulties found that 80 per cent of customers who were proactively contacted went on to work with the bank to reach an arrangement to deal with their arrears. Accompanying qualitative research showed that many felt a sense of relief that the bank had taken the initiative, and this had helped to overcome their low self-efficacy (Collard, 2011).

In recent years, the UK debt collection industry has taken steps to improve its policies and practices in relation to vulnerable consumers in response to requirements from the financial services regulator (Evans et al., 2018). Even so the regulator has found that firms did not engage effectively with customers and consequently had insufficient understanding of their needs; did not consider a range of forbearance measures to support customers with different needs and circumstances and did not apply fees and charges fairly (Financial Conduct Authority, 2022).

Environmental factors: money advice and debt resolution

Many money advice services seek to promote self-efficacy and empower people to deal with their payment difficulties themselves. Research in the UK traced the experiences of defaulters who, having failed in the past in their negotiations with creditors, tried again after receiving practical guidance from a money adviser on the best way to go about this. They achieved various degrees of success. Some needed more assistance than the guidance they had been given, while others were too daunted to try and wanted the money adviser to negotiate on their behalf and/or help them to get debt resolution (Collard and Davies, 2018).

Previous research has also shown that safety nets for defaulters can fail to protect some defaulters. Research in Norway has shown that, in 2019, money advisers closed two-thirds (64 per cent) of cases without finding a permanent solution to the payment problems that their clients faced (Poppe, 2020). In addition, between 40 and 50 per cent of the applications for a debt settlement are rejected each year in Norway (Heuer, 2014; Poppe, 2022).

In conclusion, there is a great deal of research showing that payment difficulties are strongly associated with vulnerabilities, such as poor mental health and low incomes. Moreover, preliminary research has found that (all other things being equal) defaulters who are vulnerable through poor health and labor market marginalization are more likely to experience debt enforcement than other defaulters and less likely to obtain debt resolution. There is some research to explain why this is the case, showing the key role that self-efficacy can play in determining how defaulters exercise the personal responsibility placed on them to negotiate with creditors and find a way to resolve their payment difficulties. There is, however, very little research on how the actions of the agents of collective responsibility (creditors, enforcement agencies and money advisers) affect the ability of defaulters to find resolution either directly or through their impact on the defaulter's ability to exercise personal responsibility—the key element of Bandura's model of Social Cognitive Theory. This is a knowledge gap that needs to be filled, not least for the future prospects of vulnerable defaulters.

Methods and data

This article is one of the outputs from a 4-year study, the overall objective of which is to fill knowledge gaps on the interrelationships between payment problems and vulnerability: poor health and labor market marginalization. Funded by the Norwegian Research Council, it uses a combination of qualitative research and analysis of Registry data to meet the research objectives.

Although our data was not collected to explore the impact of self-efficacy, it was clear that when people encounter inflexible bureaucracies and hit a brick wall, it is likely to have serious consequences consistent with Bandura's theory. They lose faith in their ability to negotiate a way through their problems successful accompanied by feelings of shame, hopelessness and powerlessness. In other words, their self-efficacy is undermined. This was expressed in the interviews in many ways.

This analysis draws on in-depth interviews with 28 people who had (or had had) unmanageable payment difficulties across a wide range of commitments, along with health problems and, in most instances, labor market marginalization. The types of people who, according to the UK financial services regulator, are likely to be vulnerable and “due to their personal circumstances, [are] especially susceptible to harm - particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of care” (Financial Conduct Authority, 2021, p. 3). They are also the types of people whose circumstances mean that creditors should be exercising forbearance and who should be helped by money advice and the wider welfare state to find a resolution to their problems. Yet they are more likely than other defaulters to experience debt enforcement and less likely to get debt resolution (Bakkeli and Drange, 2024).

Respondents were all living in Norway and were recruited from three sources: money advice clients at local social security offices (NAV), an Internet self-help group and the Debt Victim Alliance (a self-help and lobby organization)—with no notable difference between the people recruited from these sources. It is, therefore, a purposive and not a representative sample and designed to provide in-depth insights into the ways that people navigate their way through payment difficulties and the factors that help or hinder them along the way. Interviews were undertaken using video conferencing, as respondents were geographically dispersed across Norway.

The interviews lasted up to 3 h, were conducted by one of the authors and followed a comprehensive topic guide designed to create a timeline of events and actions from the onset of the payment problems. This timeline covered changes in health, income, family and personal circumstances, borrowing and payment difficulties. It covered in detail people's interactions with creditors, enforcement authorities, money advisers and others over the duration of their payment problems. All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed, and the transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis, a method for analyzing qualitative data that is widely used across the social sciences, to develop patterns of meaning (“themes”) across a dataset (see Ritchie and Lewis, 2003; Braun and Clarke, 2006). Although we did not set out to explore either personal responsibility or self-efficacy as topics in the interview; they emerged strongly from the interview transcripts through a rigorous process of data familiarization, data coding, and theme development and revision. These themes were then used to systematize the transcript content for each respondent, using spreadsheets.

The subsequent analysis began by allocating informants to broad groups based three factors: their acceptance of personal (moral) responsibility, their financial ability to repay what was owed, and their level of self-efficacy and mental capacity to exercise personal responsibility to resolve their payment difficulties. This identified three broad groups, each with shared characteristics that distinguished them from others:

Group A (six people) were characterized by persistently low and unstable incomes and physical health problems that were accompanied by depression and anxiety. Low income and labor market marginalization were the primary causes of their payment problems and, together with their mental health problems, undermined their ability to exercise personal responsibility. Aged between 35 and 69, they had been facing payment problems for between eight and over 20 years, with an average of just over 14 years. None of them had found a lasting solution to their payment problems and were still facing enforcement action by their creditors.

Group B (11 people) had mental health challenges (such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD, Bipolar Disorder and personality disorders) that disrupted their money management along with other aspects of their lives, and this was the primary reason for their payment difficulties. These challenges seriously impaired their agency and ability to engage with and exercise personal responsibility. They, too, had low and unstable incomes and were aged between 29 and 57. They had been experiencing payment problems for an average of 16 years—ranging from eight to 32 years. Only one had found a solution to her payment problems—through a Debt Settlement Arrangement which she had struggled to comply with.

Group C (11 people) differed from both previous groups in that their mental health problems were both acute and a consequence of their payment problems, which had been caused by unsustainable borrowing. They also differed from the other two groups in that at the time their payment problems began their incomes were higher. Between 37 and 68 years of age, they had been experiencing payment arrears for an average of 5.5 years—ranging from 2 to 14 years. Most, however, had been juggling and refinancing for a longer period of time. Most had led a comfortable life, albeit financed by heavy borrowing, prior to the onset of their payment difficulties when the pack of cards collapsed. Consequently, the shock of experiencing wage deductions for the first time took a toll on their mental health, unlike either of the other groups who had experienced both payment and health problems for most of their adult lives. Even so, most had found a solution to their payment problems or were on track to do so, usually with the help of a relative or health worker.

We should stress that, although we have given the numbers in each of the groups, these should not be taken as indicative of their relative prevalence among all defaulters. That is not the purpose of qualitative research which, instead, seeks to provide an understanding of processes and how they work. It is also important to note that the analysis is based on the narratives of these defaulters. We did not interview creditors (although we plan to do so). We did, however, seek to validate their accounts and our interpretation of them by interviewing a bailiff with many years of experience and an overview of the actions of the various actors involved in debt enforcement and debt resolution.

Results

When reading the interview transcripts, it became apparent that there was a mismatch between the level of responsibility placed on our informants as they defaulted on their commitments and their ability to exercise the degree of responsibility required. The actions of creditors clearly played a significant role in the self-efficacy and agency people had. It was equally clear that the instruments of collective responsibility can fail to protect vulnerable people in the way that they should. Money advice was not always provided when needed and often did not provide the type of assistance required. Vulnerable people also failed to get debt settlements when they could have resolved their payment problems. Both failures were partly for bureaucratic reasons but, importantly, because of an over-estimation of people's agency and self-efficacy. There were, however, some important differences in the experiences of the three broad groups we identified.

Self-efficacy

The self-efficacy of the three groups in our sample differed. People in groups A and B had low levels of self-efficacy that pre-dated their payment difficulties and were partially a consequence of their poor mental health but had also been undermined by poverty and a series of knocks throughout their lives. For example, Paula (Group A), who was in her forties, had been bullied at school, had anorexia as a teenager and had a bad relationship with her father. She left home and school at a very early age and had been fired from several jobs while still young because of her poor physical health and hospitalisations. At times she pieced together an income from several low-paid jobs. Later she lost a child in infancy and had failed a relationship with a man with alcohol and drug addictions. Her mental health had deteriorated, and she suffered from anxiety and depression and had very low self-efficacy that was further undermined by every knock she experienced.: “I give up when I face adversity … and can't see an end to it.” This could well be associated with the “scarcity mindset” which Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) argue leads poor people into sub-optimal decisions and behaviors, but the small number of people in this group restricts our ability to explore this potential link.

John (Group B) was in his early thirties, and he had been diagnosed with ADHD at 20, at the same time as his father was diagnosed. But he had declined the medication prescribed, and consequently, his adult life (like his childhood) had been chaotic, with a history of low-paid, insecure work, failed self-employment, and broken relationships. He described how the ADHD had affected his self-efficacy, “things… kind of reach a point like that and then I lose interest and then I just think, no what's the point.” Like others in this group—and in line with previous research—his low self-efficacy was a manifestation of his mental health condition.

In contrast, those in Group C had very high levels of self-efficacy at the outset. Peter was in his late thirties and had led a life that was basically beyond his income, letting his wife believe that he earned more than he did. Consistent with previous research (Rendell et al., 2021) he had a strong belief in his ability to manage things and, for 12 years, had refinanced repeatedly and maxed out on credit cards to avoid creditors taking enforcement action. He hid the financial problems from his wife in the belief that he could sort things out until, eventually, he ran out of options and received a mortgage possession order.

Individual responsibility

In the early stages of arrears, creditors in Norway have an unqualified right to recover the money owed to them. The prime responsibility is placed on the consumer, who, if they are in default, is expected to contact their creditors and negotiate a way to pay the money they owe. If they fail for any reason, creditors have a right to apply to enforcement agencies for wage deductions. Norwegian regulators, in contrast to those in some other countries such as the UK, do not place a clear responsibility on individual creditors to identify vulnerable consumers and take account of their vulnerability. Nor are bailiffs required to do so when they impose wage deductions. As we show below, defaulters in these circumstances struggled to exercise the responsibility placed on them.

Acceptance of individual responsibility

It was clear from their narratives that informants had internalized the payment norm and the self-blame that goes with not meeting it. This was especially apparent among those in Group A, who felt the moral responsibility to pay their creditors most keenly, expressing feelings of “shame,” “humiliation” and low-self-efficacy, “there's a lot of shame in these things, and that makes you feel hopeless.” Moreover, they almost all mentioned the impact on them of the Norwegian TV reality show Luksusfellen (The Luxury Trap) and had internalized the stereotype that it promulgates of the feckless consumer who over-borrows for a lifestyle beyond their means. This is ironic as it was far from the reality of their lives. Persistent low income coupled with ill health had been the cause of their financial difficulties, not irresponsible borrowing. Yet internalizing the stereotype underscored their low self-efficacy, as noted in previous research above.

Group C also accepted the responsibility both to pay what they owed and for having created their financial difficulties through over-borrowing. That said, this was sometimes tempered by a belief that creditors were complicit in their payment problems by lending irresponsibly, reflecting their higher level of self-efficacy than others in the sample. Ian's response was typical, “You have to take the blame for yourself, you can't blame anyone else… But [It was] damn easy to get loans for all that nonsense. If you could write your name, it was very simple.” This, too, is consistent with previous research.

In contrast, serious mental health problems made it very difficult for many of the informants in Group B even to engage with the moral and personal responsibility to repay their creditors. Indeed, it was seldom mentioned in the interviews. For some, low-self-efficacy was a symptom of their mental health condition (ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, and personality disorders). Paul, who had untreated ADHD, reflected, “For me, it's chaos in my head all the time. You have a million thoughts every 5 min and there's always something new and … when I have had debt problems, I just sit and think and think and think and think… It's chaos from the moment I get up until I go to bed.” For others, it was a consequence of trauma or extreme stress, resulting in depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Heavy medication compounded their problems. Maria had left Poland and settled in Norway to get away from her husband, who abused both her and her daughters. He followed her to Norway, and after social workers had insisted that he should have access to his children, the abuse started again, resulting in him being convicted. The trauma of this had a huge effect on Maria's mental health, and during this time, she had no control over her life at all, “I was really sick for 5 years. It took 5 years for me to get well. But 3 years of it, I don't remember anything. I've been on heavy antidepressants, so I don't even know how I raised my children in those 3 years.”

Negotiating with creditors

In line with other research in Norway (Poppe and Kempson, 2023), the interviews showed that, while it proved possible to reach an agreement with some creditors, all our informants had encountered others who used standard procedures and placed all the responsibility on the consumer to resolve the payment difficulties regardless of their circumstances. Communications from these creditors included standard letters, text messages, emails and phone calls. And whilst we do not know the exact content or tone of those communications, the message that people received was that the responsibility rested with them to pay the money owed in full and immediately, with no encouragement to make contact to discuss their circumstances.

Where this occurred, it had different effects on the behavior of the three groups. In our low-income Group A, failed attempts to negotiate with even some of their creditors reduced their self-efficacy, which had already been low. Consequently, they felt powerless to try and negotiate with any of their creditors. Laura was a lone mother with chronic ill health and depression who was living on social security payments. She told us, “I'm not one of those people who can really negotiate with people like that. I probably don't have that authority… and yes, they seem so powerful in a way compared to me.” She described how, when the bills came in, they overwhelmed her and she put them aside intending to pay in a week or so… but then time went by and she forgot, “It gets so overwhelming that I don't know which end I should start.”

Accepting full responsibility but lacking the money to repay what they owed, they reached a point where they chose to ignore all communications and, instead, focus on their responsibility to meet the day-to-day needs of their families as best they could. They paid only the creditors who took enforcement action and got income deductions.

Group B, the people with mental health difficulties, also largely ignored creditors' communications. But often for rather different reasons. Some were simply too ill, such as Paul above, with untreated ADHD, which caused chaos in his mind from “the moment I get up until I go to bed,” and Delia with bipolar disorder who explained “I've had such phone anxiety that I hardly dare make a phone call today.” Others were too heavily medicated to function, like Maria, who was suffering from depression and PTSD following abuse of herself and her two daughters by her husband. Where they did try to explain their health circumstances to their creditors, this often seemed to have fallen on deaf ears. They either ended up with no deal at all or with payment plans that they could not afford, which subsequently failed and caused arrears on other commitments to increase. They, too, clearly had low self-efficacy and felt unable to negotiate with their creditors, as Delia, with Bipolar Disorder, explained, “they follow the law and it is clear that the person who has the most power and the most right is the one who is the creditor. Those who owe money have the least power and are weak.” This further undermined their already low self-efficacy, just as it did in Group A.

Compared with Groups A and B, those in Group C should have been in a better position to negotiate with their creditors. Indeed, most had behaved as market actors and contacted their creditors on several occasions. But they also encountered one or more creditors with whom they could not negotiate a repayment plan that they could afford. Like Rob, who had borrowed heavily to provide his (ex)wife with the lavish lifestyle she wanted, “The people we owed money they weren't interested in contributing to any positive solution to put it this way, if you get the money in 3 years rather than 2 years, then why not, but it was a total stop, there was no interest at all.” Having higher levels of self-efficacy than Groups A and B, they typically resorted to the only strategy they felt was open to them—re-financing and further borrowing to pay their creditors—which was described as “…paralyzingly easy.” At best, this was a temporary solution, and eventually, the situation escalated until they could borrow no more.

Given their low self-efficacy creditors, most of our 28 informants should have been referred by their creditors to a money adviser for help, but only one of them had. Again, this is supported by quantitative research, which found that only 14 per cent of defaulters' contacts with their creditors resulted in a recommendation to seek money advice (Poppe and Kempson, 2023).

Environmental factors: debt enforcement agencies

If Norwegian creditors cannot reach a payment arrangement with a defaulter, they have the unqualified right to apply for enforcement—usually income deductions, sometimes accompanied by a charge on the defaulter's property or other assets. This enforcement power is given to several institutions, including the bailiff, the Tax Authorities and NAVI, the body which collects arrears on maintenance and child support payments and over-payments of social security. Income deductions operate on a “first come, first served” basis and defaulters must be left with a minimum income at subsistence level. Deductions should only be granted to one creditor at a time, leaving defaulters to pay their other creditors as best they can, but often from a substantially reduced income.

All our informants said that they had experienced income deductions and it appeared from their accounts, and that of the bailiff interviewed, that some creditors used them as the primary tool for arrears management. Creditors chose to wait their turn for an income deduction rather than make concessions to set up affordable payment plans. In the words of Richard, who had a serious personality disorder and had had income deductions for over 20 years, creditors would “… rather wait for queues in turn and renew their demands just in time so they can get the full amounts.” And it was clear that when a creditor obtained an income deduction, they were much less likely to cooperate when people tried to negotiate with all their creditors to achieve a holistic solution to their payment difficulties.

No responsibility is placed on Norwegian enforcement agencies to identify vulnerable people or circumstances where a more holistic solution is needed before imposing income deductions. And this was reflected in our interviews. Consequently, bailiffs had imposed income deductions on people with obvious vulnerabilities when a referral to a money adviser and a comprehensive solution across all creditors would have been more appropriate. As a result, people in Groups A and B had lived with income deductions for many years, and they had become a fact of life, and they lost any belief in their ability to turn things round. As Richard explained, “They pull and pull and pull… and you don't see any end to it.”

For people in Group C, however, the imposition of income deductions for the first time was usually the point where they recognized that their borrowing had got out of hand and that they had run out of options for dealing with their situation themselves. Income deductions typically led to much larger reductions in income than those experienced by people in Groups A and B, and they closed off all possibilities of further borrowing. Consequently, they began to feel powerless, and their previously high level of self-efficacy took a serious knock. For some, it was a wake-up call to try to find a way to resolve the payment problems, but for around half of Group C, the imposition of income deductions had a serious impact on both their self-efficacy and their mental health. Depression was a common thread, with two people having mental breakdowns and two contemplating suicides. Claire had been left with extensive payment problems run up by her ex-husband and described the low point she reached.

“At first, it was so unconscious that I started preparing myself, the way I look back on it. And then comes the conscious thoughts that people around me are really better off without me. Because I'm not contributing, and I can't control my own life and my own situation. And it's just chaos, I'm causing a lot of chaos, I'm in a bad place, and I was very much depressed and stuff like that in that period.”

Fortunately, her suicidal thoughts were picked up by a worker on a voluntary self-helpline, and she was talked through. Rob, whose ex-wife had expensive tastes that he had borrowed heavily to meet, was not so fortunate. When he received his first income deduction, it left him with just 47 Norwegian Kronor (approximately 5 Euros) a month and an inability to pay other creditors. He had started out with high self-efficacy and determined to find a way of paying what he owed. But repeated failure left him feeling that the only way he could control events was by ending his life.

“I had been in a meeting with the bank and had laid out a plan… it was no, no, no, all the way. And then I thought that could take charge of the whole thing. … I found myself at ease, it's awful to say it, I settled on the fact that now you're rid of the problems (Rob), now you're done with them. And then I got in the car and found a suitable freight train and I slammed in the front of it. Took off my seat belt. But I didn't go fast enough.”

Jim had started gambling to try and pay his creditors, and this had made a bad situation infinitely worse. Julie, on the other hand, had resorted to theft. She was a social worker, and the shame of being unable to pay her creditors led to her taking money from a cash fund at work with the intention of repaying it. She had been unable to do so before the missing cash was noted, and this led to a criminal prosecution, the loss of her job and her certificate to practice. This precipitated a downward spiral in her personal and economic circumstances.

As Rob's situation shows, income deductions are, however, a blunt instrument when applied to people owing money to a large number of creditors, especially if they deal with only one creditor at a time. In Norway, the level of income deductions is determined by national scales that leave defaulters with a predetermined income level depending on their circumstances. Bailiffs normally try to ascertain the exact financial circumstances of consumers, but where they get no reply, they can apply standard rates. Defaulters have a responsibility to cooperate with income deductions but do have a right to challenge the level of them, especially if they had not been based on their actual circumstances or their circumstances have changed. Across all three groups, however, informants were either unaware of this right or said that they felt powerless in the face of bureaucracy. They typically lacked an awareness of how much of their income they were entitled to retain, why the bailiff had suddenly imposed an income deduction when previously it had been refused, or even in some cases which creditors received the deducted amount. There were, therefore, instances where too much was being deducted either because informants had not provided the details requested or when allowable expenses were subsequently incurred and had not been reported to the bailiff.

Only two of our informants, both in Group C, had any success with negotiating reductions in income deductions. Others simply accepted the level of deductions imposed on them and frequently ended up with too little to live on, let alone pay their other creditors. Jenny, who had been left with serious payment problems by her ex-husband, summed this up: “You get a salary deduction, and everyone else doesn't get paid because you don't have anything to pay with and stuff. So, the debt goes up when you end up on that track.” This typically led to further payment problems and even greater feelings of hopelessness.

Environmental factors: money advice

Norway has an extensive social welfare system that should ensure that everyone has an adequate income to live on and is provided with the social and health services they need. Indeed, this is the bedrock of collective responsibility in the Norwegian context and is underpinned by money advice services and a debt settlement process to help people facing payment problems. But, as will be illustrated, these safety nets had failed the vulnerable people in our study, largely because their self-efficacy was overestimated and too much responsibility was placed on them to find solutions, but also for bureaucratic reasons. Where this happened, it continued the downward spiral in their level of self-efficacy.

The key body in this respect is the Norwegian Labor and Welfare organization, known as NAV, a government agency that provides money guidance and advice services, as well as administering social insurance and social security, housing, and job training and social work support. NAV case workers have a responsibility to identify and provide guidance and help with budgeting to people with payment problems, including referring them to a specialist money adviser in the office when needed. There are very few other free money advice services available in Norway.

The most extensive and long-term contact with NAV was found among the low-income informants with chronic ill health in Group A and in Group B, where payment problems stemmed from mental health difficulties. And their experiences were rather similar. In addition to claiming income maintenance payments, they had sought (and, in most cases, been given) financial help with bills or other payments they could not afford to pay. Some had asked caseworkers for help with budgeting as well as telling them about the effect that their money worries were having on their health. Indeed, one woman had repeatedly asked for help with budgeting. Despite this, only around half of them were referred to a money adviser even though their money problems should have been apparent to their caseworker. “NAV was not joined up, and they should have been.”

Contact with a money adviser did not, however, guarantee that people got the help they needed. Money advisers frequently overestimated their self-efficacy and ability to deal with their problems without help. There is a prevailing philosophy in NAV of empowering consumers by promoting self-help and individual responsibility. So, informants had generally been advised to compile the information needed to make a submission for debt settlement to the bailiff. They were given a spreadsheet to enter the details of their family circumstances, income, and assets, how much they owed and to whom, all needing to be corroborated by documentary evidence. This was beyond the capacity of the people in these two groups, either because of mental health challenges or because previous attempts to deal with creditors had seriously undermined their self-efficacy. What they needed was someone to help them to compile this information and failure to get it was a heavy blow. A good example of this is Paula, who had repeatedly asked both caseworkers and money advisers for guidance on how to manage her money.

“I'm just told, every single time, that you have to get control… But it is to get help to gain control that I am in contact with the debt adviser at NAV. NAV is supposed to do that.”

Only two people (both in Group B) had been helped by a money adviser to compile the information needed for a debt settlement application, and in both cases, this was only after many years during which their payment problems accumulated. As one of them commented, “… had it come in at an earlier stage … then I think much misery could have been avoided.”

Others had been told by a money adviser that they did not qualify for a debt settlement—for a range of reasons that they failed to comprehend, including that they had not (yet) fallen behind with payments, that their debts were too low or that their income was too low or too unstable. But they had not been helped to set up a voluntary payment plan with their creditors either, even though that was what they all needed and some of them had been seeking. It did little for their self-efficacy to have been turned away without help.

A number had encountered bureaucratic problems that led to a lack of continuity of help as one money adviser was replaced by another and, in some cases, led to the help they had been receiving stopping altogether. Coming on top of years of failed negotiations with creditors, this, like the other set-backs just described, pushed their self-efficacy to rock bottom. It is important to note in this context that some people in Group B had contentious relationships with NAV because of their mental health disorders, and this led to discontinuity of help. Even from their own accounts, they clearly would have been difficult people to help. Setting this in context, previous research has shown that one in five defaulters turning to NAV for help have their cases closed for failing to cooperate and demonstrate responsible behavior (Poppe, 2020). Where they have mental health challenges, this is a real matter of concern.

The experiences of NAV among the people in Group C were rather different, and to some extent, this reflected their higher levels of self-efficacy. Some had had no contact with NAV at all, primarily because they did not see themselves as NAV clients and preferred to sort things out without their help. Only two of the eleven had been helped by a money adviser to resolve their financial problems, and both had made direct contact and had not been referred by a caseworker. Both were textbook examples of how things should work. Jim, for example, had contacted NAV when his payment problems escalated after he had begun gambling heavily. He had a sympathetic money adviser who had provided a lot of help, including negotiating deals with some creditors and assisting with an application for debt settlement.

In contrast, two others in Group C had contacted a money adviser for help to set up a debt settlement at a time when they were experiencing a mental health crisis. In both cases, their capacity to sort things out without help was overestimated. They, like their counterparts in Groups A and B, were given a spreadsheet and expected to compile a list of their creditors and what they owed them. But the qualifying rules for a debt settlement were not explained. Consequently, they did not know quite where to start. Others had been told (it appeared erroneously) that they did not qualify for debt settlement—in Julie's case, four times for a variety of reasons and over a period of 7 years as her personal and economic situation deteriorated following her conviction for theft.

“All the systems that are designed to safeguard, secure, prevent and everything…, they are fundamentally mis-designed… No one is listening. No one's trying to understand it, trying to, where are you now, what's happening now.”

In this context, however, it is important to remember that the people in Group C had the highest incidence of sorting out their payment difficulties, generally doing this without professional help once their mental health and personal circumstances had improved. This is discussed further below.

Environmental factors: debt settlement

Ultimately, anyone in Norway who is permanently unable to pay the money they owe has a right to a debt settlement, providing it does not “offend moral sensibilities” and they comply with a range of requirements regarding recent borrowing and realization of any assets held, including the family home. But responsibility rests with the defaulter to both activate and execute the process, including responding to any queries. Bailiffs do, however, have the responsibility to help consumers contact their creditors if they appear to qualify for debt settlement and to put forward a “voluntary debt settlement” proposal to their creditors. If that fails, bailiffs have a responsibility to transfer the case to the court to impose a “compulsory debt settlement” on creditors. Even so, it takes a reasonably high level of self-efficacy to handle the system.

There are clear deficiencies in how the debt settlement system operates for people with complex needs. Our informants (including very vulnerable ones in groups A and B) were left to initiate the debt settlement process, compile a list of their creditors, and negotiate the debt settlement alone. Those with very low self-efficacy found this too daunting and did not apply at all. Others tried and failed because they did not understand the process or the requirements they must meet. Consequently, their self-efficacy was undermined, and they did not respond to requests for information either when the debt settlement was being set up (resulting in the application not being made) or afterwards, when the debt settlement was in place (leading to it being terminated).

In Group A, all but one of the six had tried to get a debt settlement but had failed. Their lack of understanding of the requirements placed on them led to a breakdown in communications. Only two had contacted a NAV money adviser for help with the application, and both were told they would need to contact their creditors to sort out the arrangements themselves, which they felt unable to do. “I had to contact the creditors myself … [but] NAV knows the system. They know what to ask and how to present things, right, then the creditors may be more helpful and cooperative.” After an average of 14 years with payment difficulties and many failed attempts to get help or find a solution to their difficulties, the people in Group A had given up hope, and their self-efficacy was totally undermined. Frank's financial problems were compounded when, 12 years previously, he was forced by child support workers to separate from his wife owing to her post-natal mental health problems. He then faced repeated attempts to take his children into care. As a lone father, he had to move into part-time work, and for 12 years, he had been dealing with creditors chasing him for payment. He knew he would probably qualify for debt settlement but couldn't face applying., his self-efficacy having been eroded over the years.

“You feel powerless against the system…. you don't know what to do, and no matter what you say, nothing comes out of it in a way.”

Similarly, all 11 informants in Group B had tried to get a debt settlement. Only one person had one currently, and she had been helped by a NAV money adviser, albeit 8 years later than she needed. But she struggled to make the payments, and had a psychologist not helped her, the debt settlement would have failed. Another was being helped to collect the information to apply. Most, though, had applied directly to the bailiff and failed, either because they did not meet the criteria, or they had not provided all the required information and had not responded to the bailiff's request for the missing information. Again, this was a manifestation of their mental health conditions and low self-efficacy. Like those in Group A, they had been let down by the welfare state that ought to be meeting their needs and had given up hope, accepting payment difficulties and income deductions as a way of life. Richard (who had a personality disorder) felt that he had been let down by both NAV and health workers and, after two failed attempts to get a debt settlement by applying directly to the bailiff, said, “… you feel like you deserve nothing.”

Despite the toll payment problems had taken on their mental health, people in Group C were much more likely to have higher levels of self-efficacy. Consequently, nine of the eleven had found a solution to their payment problems or seemed to be on track to do so. And for the most part, they had done this themselves. Some were in the process of setting up a payment plan with their creditors, others were compiling (or had compiled) the information to apply for a debt settlement directly to the bailiff. Often, they had had help from a family member to pay off one or more of their creditors—a source of help not available to those in Group A or most in Group B. As noted above, only two Group C informants had received help from a NAV money adviser, and both were in the process of applying for a debt settlement. Most had past experiences of applications for debt settlement that had failed for a variety of reasons: they were too young; their income was, variously, too high, too unstable, or too low; their arrears levels not high enough or they had borrowed money too recently.

However, there were two people in Group C who had no solution in sight. They had both given up after years of enforcement by their creditors (including, in one case, an eviction), reaching out to NAV and not getting the help they needed and making unsuccessful applications for debt settlement. They were feeling as hopeless as the ones in Groups A and B and with similarly low levels of self-efficacy. In Julie's words:

“It is the power you encounter in those systems, in those offices, behind those PCs, and the caseworkers you encounter in these systems that, that silences it, that self-esteem there… I don't remember what it's like to feel in financial control or feel like I'm mastering that part of my life. I don't remember how it feels.”

While Chris put it this way:

“You'd rather not go to work. You'd rather just sit in your chair and watch Netflix. You lose so much motivation for everything really, … I've got a lot of things I should have done out there and I just can't face it. Just sit and sleep and … try to make the days go by. You can't take hold of things like that.”

Discussion and concluding remarks

A key question is “how generalizable are these results?” Following the coronavirus pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis regulators have begun to question whether consumers with vulnerabilities are adequately protected and are treated fairly by their creditors. Even in the United Kingdom where the regulator had issued detailed guidance to firms, an investigation showed that there were many shortcomings and vulnerable people were not being treated fairly (Financial Conduct Authority, 2022). These findings were mirrored in Norway and elsewhere (Finanstilsynet, 2022). While a qualitative study such as this one cannot tell us how prevalent this is, it can show the mechanisms at work.

When payment difficulties occur, society places a responsibility on individuals to sort things out and repay the owed amount. This is complicated when they are unable to “balance the books,” whether through lack of income or lack of mental capacity and can rapidly lead to multiple arrears. Exercising individual responsibility then becomes a very complex process involving documenting your income and outgoings, working out who you owe money to and how much you owe, contacting each of their creditors, realizing assets if you have them, and entering a negotiated payment plan for the benefit of the creditors. If they fail in this, defaulters in Norway and many other countries have a right to money advice and, with certain conditions, to apply for a debt settlement to end the problems once and for all. But the responsibility for initiating these solutions also rests with the defaulter.

Underlying these expectations and rights lies an assumption that people act rationally. From psychological, sociological and economic theory, we know this assumption does not hold true for everyone. It requires not only the resources to make repayment offers to creditors but also the agency and, as importantly, the self-efficacy to compile the information needed and negotiate with creditors who hold the upper hand. Even those with some resources and high self-efficacy can find it very challenging to contact and negotiate with creditors—especially if there are a considerable number of them. It can be an even more complex, and sometimes impossible, task for a vulnerable defaulter, that is “someone who, due to their personal circumstances, is especially susceptible to harm - particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of care” (Financial Conduct Authority, 2021, p. 3).

All our informants, except some of those in Group B who were too ill because of mental health conditions, accepted that they had a moral responsibility to solve their payment problems. Very few were successful, and hardly any within a reasonable period of time. Taking Bandura's theoretical approach as a starting point, our analysis reveals how rejection and failure in contact with creditors and public bureaucracies reduce defaulters' self-efficacy and ability to handle payment problems. These experiences typically led to anxiety and depression, along with worsening finances. Where self-efficacy was already low, as in the two groups (A and B), whose payment problems were caused by persistent low incomes and health challenges, it worsened their existing health problems. For some of those with higher self-efficacy whose problems had arisen through over-borrowing (Group C), the mental health effects were new and created vulnerabilities where none had existed before.

Following Bandura, we have also seen that the time factor is essential. It is primarily over time that rejection and negative feedback take a toll on people. People in Groups A and B had been grappling with payment difficulties for an average of 14 and 16 years, respectively, and only one of them (in Group B) had found a resolution to their difficulties. During that time, they had received many knockbacks, and it is possible to trace the gradual decline in their self-efficacy from an already low level. The effect differs among those who entered payment problems with high self-efficacy (Group C). For them, there was a sudden drop in self-efficacy at the point where they lost control, with a concomitant effect on their mental health. Over time, and with some financial help from family members, some regained enough of their self-efficacy to begin to resolve their payment difficulties. But a minority did not and joined the trajectory of those in Groups A and B.

That vulnerable people continuously meet a brick wall in this way seems incomprehensible. So, where does it go wrong? In line with Bandura, the analysis shows that difficulties primarily arise in encounters with the bureaucratic routines of creditors, enforcement agencies and even the money advisers whose role it is to help vulnerable people. So, any attempt to raise the level of self-efficacy of the individuals is likely to be ineffective if the environmental factors undermining their self-efficacy are not addressed. Consequently, policies should focus on tackling these.

Regarding the relationship with creditors, most of our informants found it overwhelming to make contact, explain their financial situation, and negotiate a solution. And with some exceptions, their creditors seemed uninterested in either the cause or the extent of their payment problems. In Group C, the first reaction was to attempt to borrow their way out of their problems. For those in Groups A and B, it led to creditor avoidance and intensified the shame and hopelessness they felt, reducing their self-efficacy. Both reactions were counter-productive from a creditor's point of view. Nevertheless, in Bandura's model, the impact of the creditors on the individual was strong. But there was little effect in the opposite direction, with creditors adapting their actions to the circumstances of vulnerable people.

The most invasive creditor routine is enforcement through income deductions. It reduces disposable income and the ability to pay any but the creditor with income deductions. It also strongly affects self-efficacy and triggers adverse reactions depending on the person's situation. Vulnerable defaulters in Groups A and B experienced powerlessness along with anxiety and depression. In Group C, it was the first time that they had been out of control of the situation and their self-efficacy plummeted, leading to anxiety and depression and even, in some cases, to mental breakdown, suicidal thoughts and even an attempted suicide. Common to all of them, again supported by Bandura, was that they became paralyzed, tacitly accepting how they were treated and consequently deprived of agency to act upon their personal responsibility for long periods. No wonder, since the institutionalization of income deductions is based on the premise that they should continue until every creditor is repaid—which meant for the foreseeable future for many of our informants. This essentially bureaucratic system does give defaulters some limited rights over the level of deductions and, therefore, the disposable income they have. But knowledge of these was scant, and previous failed attempts to negotiate with creditors undermined the ability to negotiate with them. This ought to be the point where an overview of the extent of a defaulter's payment problems triggers a referral to a more holistic solution. But it fails to happen, and creditors wait their turn for enforced repayment. Again, the impact is one way—from the enforcement agency to the defaulter with little or no impact in the opposite direction.

It is important to tackle these problems at the earliest stage possible. This requires individual creditors to undertake a systemic review of their policies and practices to identify areas where they may undermine the self-efficacy of their customers and ways in which they could act to promote it. Drawing on an independent review of UK firms in 2022 (Financial Conduct Authority, 2022), creditors should:

• Encourage and facilitate customer engagement when payment issues start to arise—tailoring both content and communication channel to the needs of vulnerable consumers.

• Sufficiently resource their operations and ensure staff are well trained and experienced to identify and deal with customer needs proactively, especially where they are vulnerable.

• Provide appropriately tailored forbearance solutions to customers, which take account of their individual circumstances and avoid escalation to enforcement where customers are vulnerable.

• Ensure effective management oversight and quality assurance of forbearance processes and the customer outcomes achieved.

• Ensure that fees and charges for those in arrears or payment shortfall are applied fairly and only reflect reasonable costs incurred.

Moreover, where money advice service services exist creditors should work closely with them, referring vulnerable customers for advice and assistance at an early stage in the arrears management process. Where such services do not exist the need for creditors to exercise a duty of care to vulnerable customers is paramount.

Norway does, in fact, have a well-developed money guidance and advice service, both financed and run by the State. Seeking help, therefore, means turning to another large bureaucracy: the NAV money advice service. Here, defaulters must explain their personal and financial circumstances, be receptive to advice and guidance, and, in return, get help to find a solution with their creditors. The aim is to arrive at a holistic solution where both the payment difficulties and the underlying social causes are resolved. Most of our informants (especially those in Groups A and B) had long-term relationships with NAV due to their complex life situations. Despite this, they had not been helped to resolve their problems, even though all would have qualified. There were several reasons for this: their requests for help from social workers had not triggered a referral to a money adviser, bureaucratic failures led to the loss of continuity of help and even, on occasion, incorrect advice or guidance.

However, the principal failure was more systemic and arose from the philosophy of empowerment and self-help, which is the core of NAV's bureaucratic routines and many advice services in other countries. This means that, ideally, caseworkers and advisers should not take over the client's case and resolve it for them but instead involve the defaulter in the resolution process, thus empowering the client to handle their finances independently. The client is, therefore, assigned tasks and challenges. However, success assumes that the client's self-efficacy and capacity is correctly assessed. Where vulnerable clients with mental health problems are involved, NAV is dealing with people characterized by traits such as reduced short-term memory, impulsivity, social anxiety, depression, reduced ability to solve problems and make plans, high stress levels, low self-efficacy—and, most likely, a combination of many of these. Our analysis indicates that NAV often lacks sufficient in-house expertise to cope with this complexity, while previous research has found that money advisers closed two-thirds (64 per cent) of cases without finding a permanent solution to the payment problems their clients faced (Poppe, 2020). When the empowerment strategy breaks down, all responsibility and blame is shifted onto the defaulter for failing to follow through. This was devastating for our informants; each time they failed, their self-efficacy and ability to find solutions were undermined, leaving them in a state of hopelessness. Again, the feedback mechanism from the individual to the NAV money advice service (implied in Bandura's model) seemed weak, in contrast to the impact of money advisers on defaulters, which was strong.

Like creditors, money guidance and advice services should undertake a systemic review of their policies and practices to identify areas where they may undermine the self-efficacy of their customers, ways in which they could help to overcome low self-efficacy. This includes:

• Encouraging vulnerable consumers to seek money advice before their payment difficulties escalate advice, including building good working relationships with creditors and health professionals that facilitate early referrals from them.

• Ensuring staff are trained to provide practical support that is tailored to the individual needs of vulnerable consumers, including assisting them to negotiate with creditors and debt enforcement agencies and to apply for debt resolution before payment problems escalate.

• Putting in place quality assurance processes, which focus on customer outcomes.

The third bureaucracy in the landscape is debt enforcement, which in Norway is carried out by the bailiff service, part of the police. The agency has a dual role, both implementing income deductions and processing applications for debt settlement. It makes the bailiff appear as an authoritarian double agent with coercive authority to enforce payment and yet the power to cancel debts and solve problems. When defaulters turn to the bailiff to apply for a debt settlement, they usually have prior experience with the agency in its debt enforcement role. Communication is, therefore, often characterized by archived information, asymmetric power and a formal language that vulnerable debtors often find challenging to understand. Although a small minority of our informants (mostly in Group C) eventually received debt settlement, our analyses show that just about everyone had attempted at some time to get a debt settlement and had failed. Misunderstandings had arisen in communication with the bailiff, and defaulters were neither fully aware of nor able to insist on their statutory rights. Moreover, unlike NAV, the bailiff does not have social work expertise and is only required to deal with financial issues. This makes it particularly difficult for vulnerable defaulters, and previous research has shown that between 40 and 50 per cent of the applications for a debt settlement are rejected each year in Norway (Heuer, 2014; Poppe, 2022). Just as with the creditors and NAV, misunderstandings, demands for defaulters to participate in the resolution process, and ultimately rejections typically lead to impaired self-efficacy and prolongation of payment difficulties, with no feedback mechanism from the impact on the individual to the procedures of the bailiff. So bailiff's too should review and tailor their services to take account of the low self-efficacy of vulnerable defaulters.

In conclusion, we return to our research question in the light of Bandura's model:

What role does self-efficacy play when defaulters with vulnerabilities seek to exercise the personal responsibility that society places on them to adhere to the payment norm?

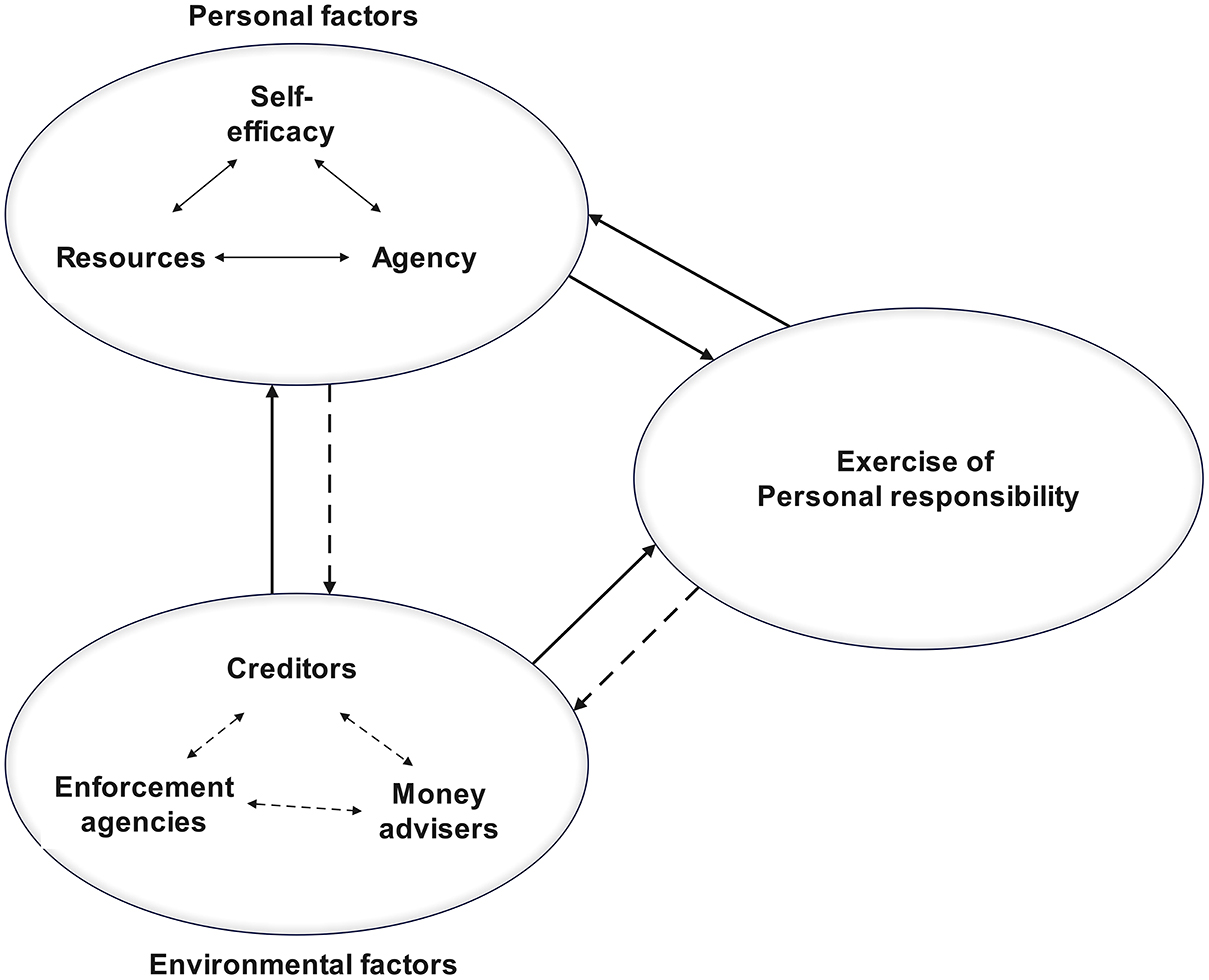

It is clear that self-efficacy interacts with other personal factors to plays a key role in determining how easily vulnerable defaulters can exercise individual responsibility to repay their creditors. Moreover, there is a feedback mechanism from their attempts to exercise personal responsibility onto their self-efficacy. This can be negative or positive, depending on their experiences (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The role played by self-efficacy in the exercise of personal responsibility: Bandura's Model of Social Cognition revisited.

Of particular importance, though, are the strong effects in Figure 2 of environmental factors (the actions of creditors, enforcement agencies and money advisers) on both the self-efficacy of the individual and their exercise of personal responsibility. Again, these can be positive (promoting self-efficacy and the exercise of personal responsibility) or negative (and undermine them). The experiences of the vulnerable people interviewed show that these were a largely negative, with very weak reverse effects leading these key players to adapt their policies and practice in the light of experience (indicated by the dotted lines). In other words, self-efficacy and the exercise of personal responsibility are eroded where creditors, enforcement agencies and money advisers take insufficient account of the vulnerabilities that defaulters may face and tailor their responses accordingly. This is compounded when these agencies operate in silos, with little or no interaction between them over individual cases—again indicated by the dotted lines between them in the diagram.