- 1Department of Leadership and Organization, BI Norwegian Business School, Oslo, Norway

- 2Department of Strategy and Management, Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway

Introduction: To improve our understanding of how people engage in altruistic behavior, it is important to investigate the motives provided by help recipients and how these motives influence givers' helping behaviors.

Method: In the present study we conduct three experiments (total N = 606), exploring how the financial motivation of help recipients can affect givers' helping behaviors.

Results and discussion: We find that people like to help others but resent helping those motivated by immediate financial gains. Study 1 shows that the recipient of help influenced the responses of the helpers depending on whether the recipient was making a sales profit from this help or not. An influencing factor was whether the recipient could provide an excuse for making such a profit. Study 2 replicated these findings also in conditions in which other kinds of profits were applied. Study 3 confirmed the results in conditions in which helpers were informed about recipients' financial motives before deciding whether to help.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the field of behavioral finance has taken an interest in the topic of social motivations in economic decision-making (Frey, 1997; Tirole, 1999; Akerlof and Kranton, 2000, 2005; Dohmen and Falk, 2011). While the standard economic model posits that decision-makers are solely motivated by maximizing utility, a considerable body of evidence indicates that a substantial number of people are motivated by concerns for fairness, intentions, and the maintenance of social relationships (Kahneman et al., 1986; Camerer and Thaler, 1995; Fehr and Gächter, 2000; Falk et al., 2008). Prosocial motives even extend into investment decisions. Riedl and Smeets (2017) demonstrate that socially responsible investments are less motivated by financial motives and more by social preference and signaling motives. As the presence of fair-minded people is likely to have important economic effects, the inclusion of social motivations in models of economic behavior has resulted in new theories capable of predicting human behavior across a wide variety of scenarios (Rabin, 1993; Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000; Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger, 2000; Charness and Rabin, 2002; Falk and Fischbacher, 2006). As fairness and prosociality have been posited to exert a powerful motivational force in humans, several scholars have argued that organizations can harness these effects in motivating employees and customers (Colquitt and Chertkoff, 2002; Payne et al., 2008). Nevertheless, it is unclear whether the motivation to help others follows the same dynamics when the recipient of help is making a financial profit from the help. In the studies reported here, we thus examine the role of social and financial intentions in governing helping behaviors.

These intentions also have the capability of influencing social relationships. This is because the use of incentives comprises an important means of affirming the nature of a social relationship. By conforming to mutual expectations about what a relationship is, the relationship can be strengthened and solidified, thus comprising a form of social communication that is reassuring and important because people care greatly about their relationships (Gallus and Frey, 2016; Frey and Gallus, 2017; Gallus, 2017; Gallus et al., 2022).

Concurrently, the use of incentives may also be at odds with a given relationship, thereby violating the expectations of the incentivized. This kind of relational incongruence may spur detrimental responses, and even be perceived as an invitation to alter the relationship altogether (Gallus and Frey, 2016; Frey and Gallus, 2017; Gallus, 2017; Gallus et al., 2022). Several strains of research support this basic assumption, primarily by demonstrating various negative consequences of using incentives that are incongruent with the behavior in question (Gallus et al., 2022).

An example of congruent behavior is when someone says that they will start working as soon as a new house has been bought. This person buys the new house with the help of their partner but does not start working. The behavior is incongruent because the statement does not match the actions.

Inspired by Fiske's (1992) relational theory, Heyman and Ariely (2004) demonstrated the existence of two different markets that are crucial for understanding the relationship between individual effort and monetary rewards (see also Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Bloom, 1999; Prendergast and Stole, 2001). The overarching idea is that people reason differently as far as prosocial motivation is concerned, depending on whether rewards are involved and on the nature of the reward (monetary or non-monetary). They found that monetary payments caused people to use marketplace frames and norms suggesting that a monetary market was at hand (see also Zelitzer, 1994; Sliwka, 2007; Lazear, 2018; Kagan et al., 2020). On the contrary, when money was not involved (i.e., when there was no monetary reward or there was a gift reward), a social market was perceived to be established. In addition, they found that mixed markets to a higher extent resembled monetary markets than social markets, implying that the mere mentioning of monetary rewards seemed to trigger a monetary market logic. These findings corroborate several other accounts provided in the experimental research literature (Festinger, 1957; Bem, 1965; Lepper et al., 1973; Deci et al., 1999; Gneezy and Rustichini, 2000).

For example, a monetary salary defined by a standard hourly rate has been observed to be relationally congruent if the recipient is a professional who has been hired for a specific job. If, however, the recipient is a friend who expected little or nothing in return, the incentives are at odds with the model both in form and means (Gallus and Frey, 2016; Frey and Gallus, 2017; Gallus, 2017; Gallus et al., 2022). Specifically, even though hourly pay is a common and well-known incentive scheme, it is not what one normally expects in return for a friendly favor; in contrast, it is likely to violate fundamental social norms and expectations, likely leading to detrimental effects on the relationship or even a redefinition of the relational premises (Gallus and Frey, 2016; Frey and Gallus, 2017; Gallus, 2017; Gallus et al., 2022).

The establishment of this two-market logic has many interesting implications for people in everyday life (Fiske, 1992). For instance, people are often in need of help in order to manage their domestic lives. Such help might pertain to moving to a new apartment, refurbishing a newly acquired apartment, babysitting, or involvement in personal accounting issues. Many of us are friends with people who can provide such help. A crucial question is therefore whether we should ask for professional help or simply reach out to a friend. In the latter case, it makes a whole lot of difference if payment is provided or not. People are sometimes willing to expend more effort in exchange for no payment (a social market) than they expend when they receive low payment (a monetary market).

In essence, social market relationships are driven by altruism such that individuals work as hard as they can without taking notice of payment (Trivers, 1971; Batson et al., 1997; Cialdini, 1997). Expressed differently, the issue of financial compensation becomes irrelevant in this type of market. By contrast, monetary market relationships are characterized by to what extent reciprocity governs efforts made and that the degree of payment has a direct impact on the level of effort (Clark and Mills, 1993; Rabin, 1993; Fehr and Falk, 2003).

The results provided by Heyman and Ariely (2004) propose that monetary rewards have a bearing on individual effort in only the monetary market and that the social market, which is ruled by non-payment, fosters altruistic behavior. However, all the scenarios used in their experiments are built on individual gain maximization driven by either extrinsic or intrinsic motivation.

We hence notice that there is a gap in the existing research literature such that the two market mechanisms have not been experimentally tested in situations in which there is a social contract at stake governed by a norm system. It would therefore be most interesting to learn if the mechanism operates in the same way in situations where there is a social relationship between the giver of help and the recipient. In a series of experiments, we thus investigate to what extent the mechanism is functioning in social relationships subject to the breach of trust (Elangovan and Shapiro, 1998; Robinson and Morrison, 2000; Koehler and Gershoff, 2003; Schweitzer and Hershey, 2006) and intentionality (Shaver, 1985; Shultz and Wells, 1985; Dennett, 1987; Fiske, 1989; Swap, 1991; Weiner, 1995; Malle and Knobe, 1997).

A drawback with the study of Heyman and Ariely (2004) is that they encountered difficulties in explaining to what degree the motivation observed in their social market condition actually is related to prosocial motivation (e.g., helping load a sofa into a van without payment). The reason for this is that there is no prosocial information included in their social market condition, other than an absence of monetary or other rewards. Because the recipients of help are unknown to participants, the motivation to help in their social market condition could, in fact, be founded on many different reasons. Hence, participants in Heyman and Ariely's social market conditions could have been motivated by the fact that they simply liked the task as an interesting means of physical exercise (Deci et al., 1999).

According to the literature, there are three possible non-pecuniary motives: (1) the desire to reciprocate, (2) the desire to gain social approval, and (3) the intrinsic enjoyment arising from working with interesting tasks (Fehr and Falk, 2003; Gneezy et al., 2011). We, therefore, argue that there is a call for a design of social market conditions that provides a more relevant arena for testing out the social market perspective. The mission of such a design will be to establish a clearer link between unpaid help and prosocial motivation. The term intrinsic motivation has not traditionally been tied to utility (Deci et al., 1999), and our view is that social market capital has close connections to such a utility. For several reasons, we think that intrinsic enjoyment is disqualified as a non-pecuniary motive in the social market. This is because the sheer pleasure of enjoyment seldom is tied to social utility. However, the desire to reciprocate does not fare better as a promising motive because reciprocity is a factor in both markets. In other words, reciprocity applies to both markets but not similarly if it is underlying a social contract, which substitutes the monetary contract. Hence, we are left with the desire to gain social approval as our prime candidate for a motive for gaining social utility (Bénabou and Tirole, 2003). This makes sense in many ways.

When people expect social market returns and do not receive them as expected, they are bound to react very negatively. It is our perspective that the desire to gain social approval by engaging in altruistic activities will create expectations of receiving such social market capital. When other parties try to convert this expected social capital into monetary capital, a feeling of betrayal is likely to appear (Camerer, 1997; Kahneman et al., 1997; Bénabou and Tirole, 2003). This will, in turn, most probably lead to unhappiness because happiness is related to how human beings value goods, services, and social conditions that include considerations of non-material values such as social relations (Frey and Stutzer, 2002, 2010; Frey, 2010). Although not explicitly acknowledged by Heyman and Ariely, an important feature of the social market is that it also includes social contracts. A social contract is an individual's beliefs about a reciprocal exchange agreement between that person and another party. It focuses on individuals' beliefs in a promissory contract. Unlike formal contracts in the money market, the social contract is purely perceptual. Both parties may therefore not be able to share an understanding of it (Robinson, 1996).

1.1 Willingness to help when learning about the outcomes of a recipient's behavior

Our main proposition is that when people perceive the recipient of help as pursuing immediate financial gain, they become more transactional in thinking about the relationship and less prosocial. Specifically, we expect that helping a friend who immediately makes money from our help will cause more negative and less positive emotions than ordinary helping. In line with Fiske's (1992) theory, we also expect that people will feel that asking a friend for help when pursuing immediate financial gains constitutes a violation of social norms. For instance, it has been observed that people in general are affected by a friend's betrayal such that their trust in that person is reduced considerably (Elangovan and Shapiro, 1998). When a giver of help experiences that a purposeful breach of trust has been achieved by a friend, they will experience strong feelings of a violation (Robinson and Morrison, 2000; Koehler and Gershoff, 2003; Schweitzer and Hershey, 2006). Consequently, we assume that people who help a financially motivated friend will feel less inclined to help that same friend again—free of charge—in the future. We suggest that the observed altruistic behavior is related to some form of social market utility, for instance, social contribution, social approval, or the desire to reciprocate (Simon, 1993; Rose-Ackerman, 1996; Fehr and Schmidt, 2006; Wilson, 2015).

Taking the preceding reasoning into account, it seems likely that the recipient of help will influence the emotional, socio-cognitive, and behavioral consequences of the helpers depending on whether the recipient is observed to make a sales profit from this help and whether they can provide an excuse for making such a profit. Past research has indicated that apologies are only effective if the offense was not clearly intentionally committed (Fischbacher and Utikal, 2013). We, therefore, expect said excuse to only be effective in as much as it indicates that profit-seeking was not the original intention when the person asked for help.

1.2 Willingness to help when learning about the intentions of a recipient

The concept of “intentionality” has played an important role in social psychology and has been subject to the interest of several attribution theorists (Shaver, 1985; Shultz and Wells, 1985; Dennett, 1987; Fiske, 1989; Swap, 1991; Weiner, 1995). Malle and Knobe (1997) have found that people generally receive more praise and more blame for actions that are considered intentional rather than unintentional. Similarly, intentional acts of helping are more prone to be reciprocated than unintentional ones (see also McCabe et al., 2003; Keren, 2007).

We hence expect that actions that are considered intentional will receive more blame than unintentional ones (Shaver, 1985). Put differently, we believe that learning about a recipient's negative intention to make a monetary profit should have an effect on the giver's attitude. For this reason, it is plausible to assume that the recipient of help will influence the helpers depending on if the recipient initially clearly states that they intend to make an immediate profit from this help. Based on Pfattheicher et al. (2022), we argue that the social market is driven by altruistic behavior from an intentionalist perspective. This implies motivation with the ultimate goal of increasing another's welfare. It also implies voluntary behavior intended to benefit another, which is not performed with the expectation of receiving external rewards.

However, using the intentional perspective without any regard for consequences will undoubtedly lead to a financial, as well as a non-financial, gain as eligible for treatment as welfare. In other words, intentional altruism—seen in isolation—will be indifferent to the resulting outcome (social or financial). Thus, the implication is that the application of intended altruism alone will result in blindness to form or consequences. For this reason, both intentions and consequences (social or financial) matter for altruism in the social market (Pfattheicher et al., 2022). In cases where a person makes a profit from the helping behavior of a friend, but where it is clear that profit-seeking was not the original intention of the person asking for help, we expect that the norms governing the interaction will revert to the social realm.

1.3 Overview of present research

We tested these hypotheses in three separate experiments. Following the tradition in the helping behavior literature, the studies involved different tasks over several rounds. All experiments were concerned with helping behavior in social relationships, wherein one party bought an apartment. Financial motivation is always a part of real estate transactions but not necessarily the primary motivation. When private individuals buy and sell real estate the most common reason for doing so is that they are relocating from one apartment to another. Hence, the primary motivation for the transaction is relocation and change in residence. However, some private individuals buy, rent out, and/or sell apartments primarily as an investment. In such cases, the financial motivation for the transaction is much more salient. Therefore, by varying descriptions about what an individual does with an apartment (i.e., lives in it, rents it out, or resells it), we can introduce differences in how much financial motivation is attributed to the person asking for help, while avoiding the introduction of confounding variables. In conclusion, we believe that most people buy property in order to increase their wellbeing and standard of living. However, the enormous increases in prizes that have occurred during the last 20 years due to the economic policies of the central banks (low interest rates) have made it extremely profitable for some people also to buy, renovate, and sell in order to achieve a fast monetary profit (e.g., Bernanke et al., 1999). It is this latter feature of the market that we are taking into account in our experiments.

In the first study, we investigated if and how the immediacy and salience of financial motivation of the recipient of help (sales profit), could affect the prosocial motivation of the giver of help. In the second study, we replicated the findings using an alternative form of financial motivation that was not based on a windfall but on intertemporal profits in terms of periodically received rents for the apartment. In the third study, we applied an intentional description in which the giver of help was informed about the recipient's intentions prior to helping.

2 Experiment 1

In our first study, we investigated if and how the immediacy and salience of financial motivation of the recipient of help (sales profit) could affect the prosocial motivation of the giver of help. We investigated this with a vignette-based experiment, describing a common scenario: helping a friend paint the walls of his apartment. A sample of working adults was recruited to perform the experiment online (N = 180, 106 female, mean age 41 years). Having no prior knowledge of the expected effect size, we opted for at least 60 participants per cell heuristically, based on our best understanding of current research practice. We recruited participants by asking a large convenience sample of managers and human resources HR representatives in different organizations to distribute a link and invitation to our experiment via workplace emails. We invited multiple organizations in both the private and public sectors, including healthcare, education, industry, banking, petroleum services, construction, and transportation.

All participants read the same introductory text:

Imagine a friend calls and tells you he has bought an apartment. He explains that the apartment is in good condition, but that some of the rooms could use a small upgrade. He asks you to help him with this in the coming weekend. You show up and spend an entire Saturday and Sunday fixing and painting the living room walls. The results are very pleasing. Your friend buys beer and pizza on Sunday afternoon, as a way to show his appreciation. Other than this, you were given no compensation for the work you performed.

Having read this, the participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. The participants in the first condition read that the friend in question subsequently moved into the apartment, lived in it for 7 years, and then sold it with a solid profit. This condition will be referred to as the “stayed” condition, even though the friend sold the apartment several years after the help had been given. The participants in the second condition read that the friend never moved into the apartment. After the work was finished, he immediately put the apartment back on the market. It was sold 7 days later, at a solid profit. This condition will be referred to as the “flipped” condition, derived from the term house flipping, which denotes the process of buying, rehabilitating, and selling properties for profit. The participants in the third condition read the same description as the second condition, only adding that the friend called and explained that his father had suddenly turned ill, which is why he was immediately selling the apartment and moving back to his hometown. This will be referred to as the “flipped with excuse” condition.

After reading their respective vignettes, all participants were asked to provide their judgments about the scenario in an online questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to measure participants' predicted emotional, socio-cognitive, and behavioral responses to the scenario. See the Appendix for the full measurement model.

2.1 Results and discussion

The outcome measures included two manipulation checks, testing whether the participants had taken note of the independent variables. Ten participants failed to pass those manipulation checks and were thus excluded from the data set. A further manipulation check was used to determine the effectiveness of the manipulation in changing impressions about the motivation of the recipient of help. To confirm that the three experimental groups were similar in terms of demographic characteristics, we compared the respondents' gender and age across the groups, using a chi-square test for independence and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), respectively. The three groups did not differ in terms of gender, χ2(2, N = 169) = 0.996, p = 0.61, phi = 0.08, or age, F(2,165) = 0.06, p = 0.94. An ANOVA with Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc tests confirmed that the recipient of help had come across as more financially motivated when he flipped that apartment without excuse than with excuse (p < 0.001), and more financially motivated when he flipped the apartment with excuse compared to when he stayed in the apartment (p < 0.001).

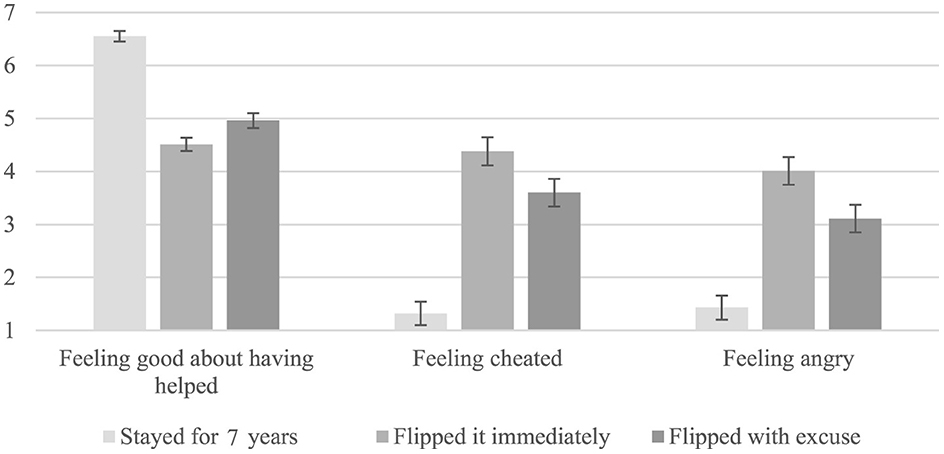

We first analyzed the expected emotional responses of the participants, using the same type of ANOVA and post-hoc test as with the manipulation check measures.1 As expected, the participants expected to feel much more negative feelings and much less positive feelings from having helped a friend flip an apartment rather than just rehabilitating it for their own use. The participants felt more cheated, angrier, and less positive about having helped when they learned that the friend had flipped the apartment (p < 0.001 for all). The participants in the third condition, who learned that the friend had flipped the apartment due to unforeseen illness, also expected to feel more negative and less positive feelings, but not as bad as the condition where the apartment was flipped without any excuse. Figure 1 displays the between groups differences in emotional reactions.

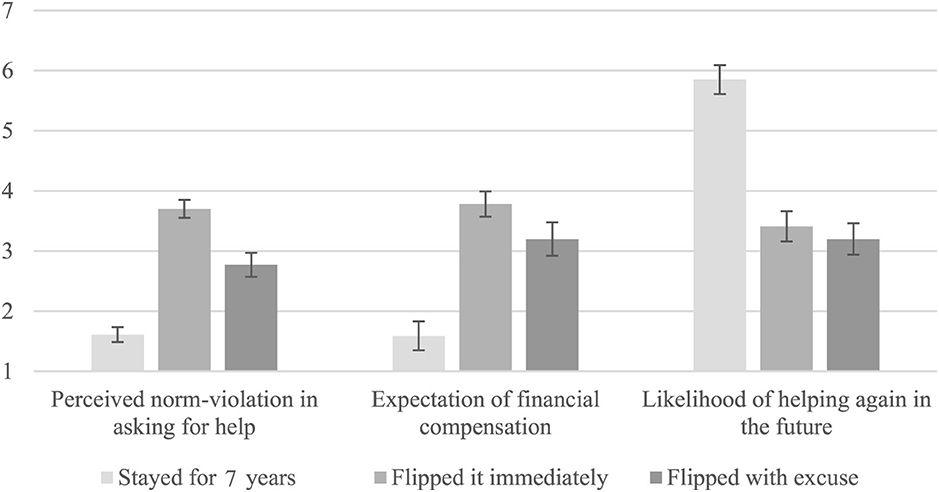

We further analyzed the between-group differences in perceptions of norm violation. The analysis revealed that asking for help to flip an apartment was seen as a norm violation while asking for the same help and subsequently staying in the apartment was not (p < 0.001). The participants in the “flipped with excuse” condition felt the friend had committed more of a norm violation than the participants in the “stayed” condition but less than the “flipped without excuse” condition (p < 0.001 and p < 0.004, respectively). There were similar between-group differences in an expectation of financial compensation and the likelihood of helping again in the future. When the friend stayed in the apartment, participants expected no financial compensation for their work and predicted that they would help again in the future. When the friend flipped the apartment without any excuse, participants were more inclined to expect financial compensation and thought it unlikely that they would help that same friend ever again (p < 0.001 for all differences). The participants in the flipped with excuse condition reported values in the middle ground between the two other conditions, feeling somewhat deserving of financial compensation, and neutral about the prospect of helping again in the future. Figure 2 displays the between-group differences in socio-cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

To conclude, these findings demonstrate that the financial motivation of the recipient of help influenced the emotional, socio-cognitive, and behavioral consequences of the helpers. The fact that the excuse offsets the negative effects of the financial gain further indicates that the initial intentions of the recipient of help matter when attributing different motivations. Whether the excuse would have been accepted or not is difficult to ascertain in a hypothetical scenario, as this would be contingent on a whole host of factors pertaining to the person offering the excuse and the nature of their relationship. However, the results seem to indicate that the mere presence of an excuse offsets the perception that the recipient of help had a direct intention to convert the help into immediate financial profit.

3 Experiment 2

In order to test the universality of the effects reported in Study 1, we performed a very similar experiment on how the financial motivation of the recipient of help can affect the prosocial motivation of helpers. The design of this study was largely identical to the first study. However, in this study, we manipulated the description of the recipient of help as having either (a) moved into the apartment and stayed there for years, (b) immediately rented out the apartment, or (c) immediately rented out the apartment due to an unforeseen job opportunity in a different city. There are several differences between renting out and flipping an apartment. Renting the apartment does not entail a change of ownership, which can be psychologically relevant. Rental contracts are also less definitive than sales in that the agreements can be canceled or terminated at the will of either party.

We recruited 192 working adult participants for a vignette-based experiment (102 female participants, mean age 35 years). The recruitment process was identical to the one used in Study 1, only we asked new organizations to invite their employees to participate.

3.1 Results and discussion

Three participants failed the reading check question and were excluded from the data set. In order to explore between-group differences, we performed ANOVAs with Tukey's HSD post-hoc tests. The manipulation check confirmed that the friend who had stayed in the apartment came across as very low in financial motivation (M = 1.71, SD = 1.14], while the friend who had rented the apartment was seen as higher in financial motivation (M = 4.51, SD = 1.22). The friend who rented the apartment due to an unforeseen job offer left the participants with a lower sense of financial motivation (M = 2.86, SD = 1.56). To confirm that the three experimental groups were similar in terms of demographic characteristics, we compared the respondents' gender and age across the groups, using a chi-square test for independence and a one-way ANOVA, respectively. The three groups did not differ in terms of gender, χ2(2, N = 183) = 0.104, p = 0.949, phi = 0.02, or age, F(2,181) = 0.91, p = 0.404.

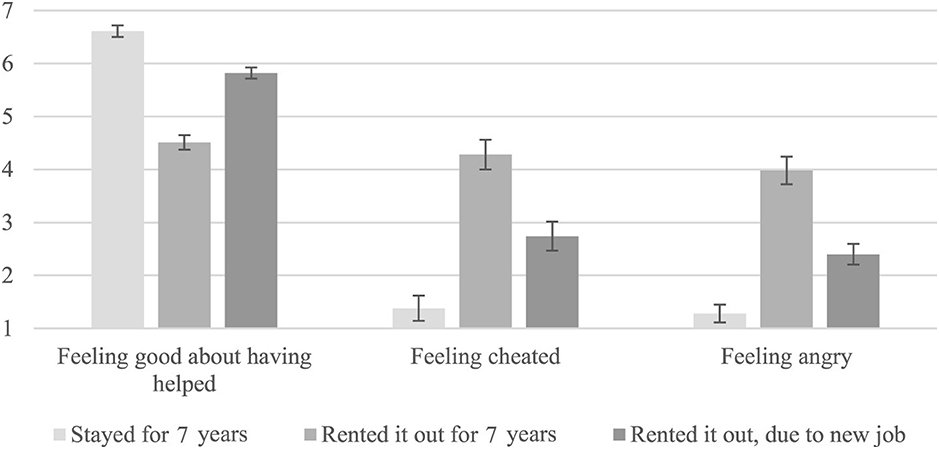

The results from Study 2 were completely in line with those from the first study. As in the first experiment, people felt much less positive and much more negative feelings from helping a financially motivated friend. The participants felt angry and deceived when the friend had rented the apartment, less so when he had an excuse for renting it, and not at all when he stayed in the apartment (p < 0.001 for all differences). Conversely, the participants expected to experience very few positive feelings from helping the friend who rented out the apartment, somewhat more when he did so with an excuse, and much more when he stayed (p < 0.05 for all differences). Figure 3 displays the between groups differences in emotional reactions.

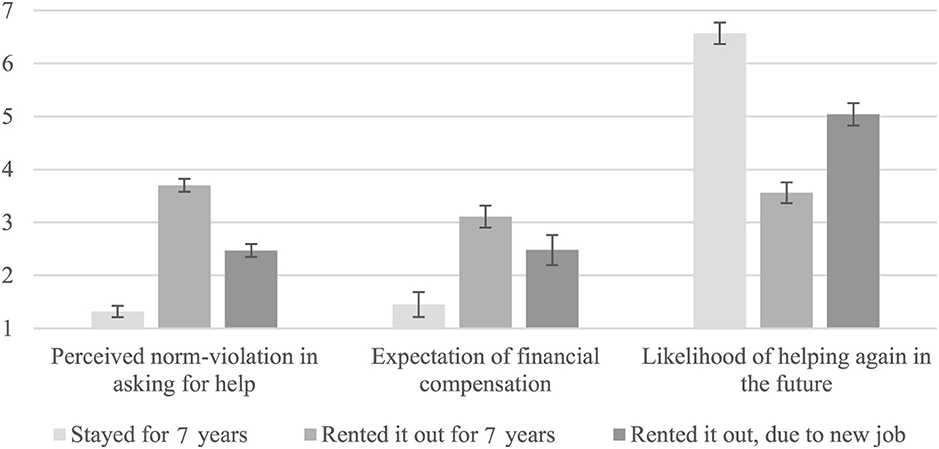

The groups also differed significantly in their judgments about norm violations in asking for help. The friend who rented out the apartment was seen as violating a social norm in asking for help. The norm violation was seen as less clear when he had an excuse for renting it out. Finally, the friend who stayed in the apartment was seen as not violating a norm at all (p < 0.001 for all differences). The groups also differed in behavioral predictions in the expected direction. When the friend stayed in the apartment, participants felt strongly that they would help again in the future. This feeling was weaker for the participants whose friend had rented the apartment with an excuse and even weaker when the friend rented the apartment without an excuse (p < 0.001 for all differences). Finally, participants expected no financial compensation from the friend who stayed in the apartment, some compensation from the friend who rented with an excuse, and the highest level of compensation from the friend who rented without an excuse (p < 0.05 for all differences). Figure 4 displays the between groups differences in socio-cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

Taken together, these findings confirm that the financial motivation of the recipient of help influenced the emotional, socio-cognitive, and behavioral consequences of the helpers, even in cases in which the transactions at hand are less definitive.

In both these studies, participants were asked to imagine that the knowledge about what the friend ended up doing with the apartment only arrived after the help was given. As the friend is seen as violating a norm in asking for help when financially motivated, this limits the generalizability of our findings. We addressed this issue in the third and final experiment.

4 Experiment 3

In the third and final experiment, participants were asked to imagine that a friend called on them for help in painting the walls of an apartment. However, in this experiment, the friend was completely explicit about his intentions with the apartment, and the participants were asked to predict their emotional, socio-cognitive, and behavioral responses to the call for help. Participants in the first condition read that the friend intended to fix up the newly bought apartment, move in, and stay there. Participants in the second condition read that the friend intended to flip the apartment. Participants in the third condition read that the friend intended to move into the new apartment but needed help fixing his old apartment before putting it on the market. We included the last condition to be able to control for the effect of imagining that one would be able to spend time in the apartment as a guest and thus feel selfishly motivated to fix it up. We expected that the responses from participants in this condition would not differ from those in the first condition. Although the friend is motivated by immediate financial gain when fixing his old apartment before putting it on the market, he does not come across as a professional real estate investor. The primary reason for the transaction and need for help is relocating, not profit.

We recruited 234 working adults to participate in the experiment (126 female participants, mean age 40 years), using the same recruitment procedure as in the other studies.

4.1 Results and discussion

Seven participants had failed to notice the friend's intention with the apartment and were thus excluded from further analysis. In order to explore between-group differences, we performed ANOVAs with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests. The manipulation check confirmed that the friend came across as financially motivated when he was asking for help to flip the apartment but not in the other two conditions (p < 0.001 for both). The level of financial motivation attributed to the friend who was asking for help in fixing the old apartment was not significantly different from that attributed to the friend who wanted help fixing the new apartment (p = 0.469). To confirm that the three experimental groups were similar in terms of demographic characteristics, we compared the respondents' gender and age across the groups, using a chi-square test for independence and a one-way ANOVA, respectively. The three groups did not differ in terms of gender, χ2(2, N = 210) = 0.014, p = 0.993, phi = 0.01, or age, F(2,206) = 0.25, p = 0.776.

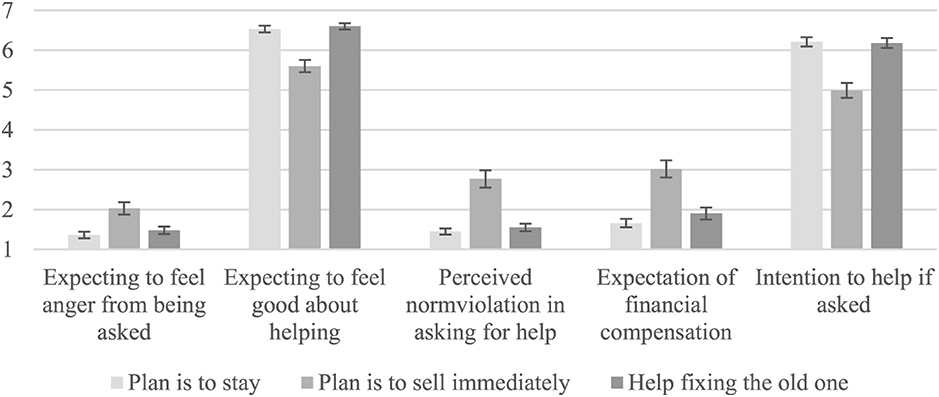

Being asked to help flip an apartment produced more negative and less positive emotions than being asked to help fix a new or old apartment in an ordinary relocation. Participants asked to help when the friend was relocating did not feel angry, regardless of whether they were asked to help fix the new or old apartment. The participants who were asked to help flip an apartment felt significantly higher levels of anger from being asked (p < 0.001 for both). In this experiment, participants expected to feel positive feelings from having helped in all conditions, but the expected levels were lower when helping with a flip than with a normal relocation (p < 0.001). The level of expected positive feelings from helping did not differ from helping fix the new or old apartment. A similar pattern of between-group differences was found in expected socio-cognitive and behavioral reactions. The participants felt no norm violation with being asked to help when the friend was merely relocating but some norm violation when asked to help with a flip (p < 0.001). They had no expectation of financial reward for helping when the friend was relocating but felt that payment was in order when helping with a flip (p < 0.001). Finally, the participants felt strongly that they would help when the friend was relocating but much less so when the friend asked for help with flipping an apartment (p < 0.001). Figure 5 displays all between-group differences in Study 3.

5 General discussion

Three experiments were conducted using case-based scenarios. Our major aim was to show that the two-markets explanation provided by Heyman and Ariely (2004) was also valid for situations in which the giver of help and the recipient were engaged in a relationship characterized by social trust.

5.1 Main findings

When the financial incentives of the recipient of help were not mentioned, the effort provided by the giver seemed to stem from altruistic motives. On the contrary, when recipients' financial motives were salient, the effort provided by the givers seemed to be driven by reciprocation motives (see also Fiske, 1992), and the absence of financial reciprocation was seen as unfair. In line with Heyman and Ariely (2004), we also found that in mixed-market conditions, the mere mentioning of recipients' financial incentives made givers switch from perceiving the relationship as based on social-market principles to being governed by money-market reasoning (Festinger, 1957; Bem, 1965; Lepper et al., 1973; Deci et al., 1999; Gneezy and Rustichini, 2000).

A crucial difference between our experiments and those of Heyman and Ariely (2004) is that we studied how providers of help reacted to recipients' incentives, whereas they focused on people's propensity to expend effort in exchange for payment or no payment. A conclusion that can be drawn from the comparison between the two studies is that the two-market perspective is not only sensitive to the nature of rewards tied to the provision of help but also to how one interprets the incentives of recipients. This implies that observing another person's behavior has the potential to falsify initial market categorization. For instance, if a giver is under the impression that he or she is acting in a social market and is observing that the recipient of help is not acting in line with these expectations, the impression is shifted toward a money-market view. Our results thus demonstrate that when the recipient of help is seen as primarily motivated by financial gains, the willingness to help is markedly reduced, even if first impressions indicate otherwise.

5.2 Limitations

In our study, helpers' positive expectations about recipients' behaviors were in some conditions violated, resulting in reduced willingness to help in the future. Introducing an excuse provided by the recipients was generally observed to have a positive effect on the helpers' prosocial behavior. To some extent, this is intriguing because the excuse can be seen as a signal of guilt, which would decrease helpers' trust. By comparison, making an excuse also involves elements of regret that communicate recipients' intentions to avoid similar violations in the future. This most likely increased the observed trust among helpers. Our results thus indicate that the benefits of apologizing due to potential redemption to some extent outweighed the costs tied to the confirmation of guilt (Bottom et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2004). However, the effect was not as strong as to falsify the two-market hypothesis; that is, the force of the excuse as a measure of trust repair did not result in a shift of market view. Put differently, the excuse provided by recipients did not make helpers shift from a money market view to a social market perspective.

5.3 Conclusion

Transactions among friends can be governed by a market logic or a social logic. These two sets of social regulations provide different stipulations about which behaviors are normatively acceptable and what the parties can expect from one another. Past research has demonstrated that by offering the provider of help a small monetary salary, the prosocial motivation to help was reduced. We demonstrate that this effect is also relevant when the recipient of help gets a salient financial benefit from being helped. The presence of financial gains at either end of the giver–recipient dyad seems to crowd out prosocial motivation and introduce the norms of market logic to the transaction.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by BI Norwegian Business School, Department of Leadership and Organization. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MG: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MS: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2024.1297601/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^All p-values reported across all three experiments refer to the results of ANOVA analyses with HSD post-hoc tests.

References

Akerlof, G. A., and Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Q. J. Econ. 115, 715–753. doi: 10.1162/003355300554881

Akerlof, G. A., and Kranton, R. E. (2005). Identity and the economics of organizations. J. Econ. Perspect. 19, 9–32. doi: 10.1257/0895330053147930

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14, 20–39. doi: 10.2307/258189

Batson, C. D., Sager, K., Garst, E., and Kang, M. (1997). Is empathy-induced helping due to self-other merging? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 495–509. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.3.495

Bem, D. J. (1965). An experimental analysis of self-persuasion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1, 199–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(65)90026-0

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2003). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 70, 489–520. doi: 10.1111/1467-937X.00253

Bernanke, B. S., Gertler, M., and Gilchrist, S. (1999). “The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework,” in Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 1, Part C, eds. J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 1341–1393.

Bloom, M. (1999). The performance effects of pay dispersion on individuals and organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 42, 25–40. doi: 10.2307/256872

Bolton, G. E., and Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 166–193. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.1.166

Bottom, W. P., Gibson, K., Daniels, S., and Murnigham, J. K. (2002). When talk is not cheap: Substansive penance and expressions of intent in rebuilding cooperation. Organizat. Sci. 13, 497–513. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.5.497.7816

Camerer, C., and Thaler, R. H. (1995). Anomalies: ultimatums, dictators, and manners. J. Econ. Persp. 9, 209–219. doi: 10.1257/jep.9.2.209

Camerer, C. F. (1997). Progress in behavioral game theory. J. Econ. Persp. 11, 167–188. doi: 10.1257/jep.11.4.167

Charness, G., and Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Q. J. Econ. 117, 817–869. doi: 10.1162/003355302760193904

Cialdini, R. B. (1997). Reintterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 481–494. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.3.481

Clark, M. S., and Mills, J. (1993). The difference between communal and exchange relationships: what it is and is not. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 19, 684–691. doi: 10.1177/0146167293196003

Colquitt, J. A., and Chertkoff, J. M. (2002). Explaining injustice: The interactive effect of explanation and outcome on fairness perceptions and task motivation. J. Manage. 28, 591–610. doi: 10.1177/014920630202800502

Deci, E. I., Koestner, R., and Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 125, 627–668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Dohmen, T., and Falk, A. (2011). Performance pay and multidimensional sorting: productivity, preferences, and gender. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 556–590. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.2.556

Dufwenberg, M., and Kirchsteiger, G. (2000). Reciprocity and wage undercutting. Eur. Econ. Rev. 44, 1069–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(99)00047-1

Elangovan, A. R., and Shapiro, D. L. (1998). Betrayal of trust in organizations. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 547–566. doi: 10.2307/259294

Falk, A., Fehr, E., and Fischbacher, U. (2008). Testing theories of fairness – intentions matter. Games Econ. Behav. 62, 287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2007.06.001

Falk, A., and Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games Econ. Behav. 34, 293–315. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2005.03.001

Fehr, E., and Falk, A. (2003). Psychological foundations of incentives. Eur. Econ. Rev. 46, 687–724. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00208-2

Fehr, E., and Gächter, J. (2000). Fairness and retaliation: the economics of reciprocity. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 159–181. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.3.159

Fehr, E., and Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 114, 817–868. doi: 10.1162/003355399556151

Fehr, E., and Schmidt, K. M. (2006). “The economics of fairness reciprocity, and altruism – experimental evidence and new theories,” in Handbook of Economics of Giving, Altruism, and Reciprocity, eds. S. C. Kolm and J. M. Ythier (Amsterdam: North-Holland).

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Evanston, IL: Peterson. doi: 10.1515/9781503620766

Fischbacher, U., and Utikal, V. (2013). On the acceptance of apologies. Games Econ. Behav. 82, 592–608. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2013.09.003

Fiske, A. P. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol. Rev. 99, 689–723. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.689

Fiske, S. T. (1989). “Examining the role of intent: Toward understanding its role in stereotyping and prejudice,” in Unintended Thought: Limits of Awareness, Intention, and Control, eds. J. S. Uleman and J. A. Bargh (New York: Guilford), 253–283.

Frey, B. S. (1997). Not Just for the Money: An Economic Theory of Personal Motivation. Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar Publishing.

Frey, B. S., and Gallus, J. (2017). Towards an economics of awards. J. Econ. Surv. 31, 190–200. doi: 10.1111/joes.12127

Frey, B. S., and Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? J. Econ. Lit. 40, 402–435. doi: 10.1257/jel.40.2.402

Frey, B. S., and Stutzer, A. (2010). Happiness and Economics: How the Economy and Institutions affect Human Well-being. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gallus, J. (2017). Fostering public good contributions with symbolic awards: a large-scale natural field experiment at Wikipedia. Manage. Sci. 63, 3999–4015. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2016.2540

Gallus, J., and Frey, B. S. (2016). Awards: A strategic management perspective. Strat. Manage. J. 37, 1699–1714. doi: 10.1002/smj.2415

Gallus, J., Reiff, J., Kamenica, E., and Fiske, A. P. (2022). Relational incentives theory. Psychol. Rev. 129, 586–602. doi: 10.1037/rev0000336

Gneezy, U., Meier, S., and Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don't) work to modify behavior. J. Econ. Persp. 25, 191–210. doi: 10.1257/jep.25.4.191

Gneezy, U., and Rustichini, A. (2000). Pay enough or don't pay at all. Q. J. Econ. 115, 791–810. doi: 10.1162/003355300554917

Heyman, J., and Ariely, D. (2004). Effort for payment: a tale of two markets. Psychol. Sci. 15, 787–793. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00757.x

Kagan, E., Leider, S., and Lovejoy, W. S. (2020). Equity contracts and interactive design in start-up teams. Manage. Sci. 66, 4879–4898. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2019.3439

Kahneman, D., Knetch, J. J. L., and Thaler, R. H. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. Am. Econ. Rev. 76, 728–741.

Kahneman, D., Wakker, P., and Sarin, R. (1997). Back to bentham: explorations of experimental utility. Q. J. Econ. 112, 375–405. doi: 10.1162/003355397555235

Keren, G. (2007). Framing, intentions, and trust-choice incompatibility. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 103, 238–255. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.02.002

Kim, P. H., Ferrin, D. L., Cooper, C. D., and Dirks, K. T. (2004). Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for reairing competence- versus integrity-based trust violations. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 104–118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.104

Koehler, J. J., and Gershoff, A. D. (2003). Betrayal aversion: when agents of protection become agents of harm. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 90, 241–266. doi: 10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00518-6

Lazear, E. P. (2018). Compensation and incentives in the workplace. J. Econ. Persp. 21, 91–114. doi: 10.1257/jep.21.4.91

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., and Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining children's intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: at of the “overjustification” hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 28, 129–137. doi: 10.1037/h0035519

Malle, B. F., and Knobe, J. (1997). The folk concept of intentionality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 101–121. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1996.1314

McCabe, K. A., Rigdon, M. L., and Smith, V. L. (2003). Positive reciprocity and intentions in trust games. J. Econ. Behav. Organiz. 52, 267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(03)00003-9

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 36, 83–96. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0070-0

Pfattheicher, S., Nielsen, Y. A., and Thielmann, I. (2022). Prosocial behavior and altruism: a review of concepts and definitions. Curr. Opini. Psychol. 44, 124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

Prendergast, C., and Stole, L. (2001). The non-monetary nature of gifts. Eur. Econ. Rev. 45, 1793–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(00)00102-1

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 83, 1281–1302.

Riedl, A., and Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible mutual funds? J. Finance 72, 2505–2550. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12547

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 41, 574–599. doi: 10.2307/2393868

Robinson, S. L., and Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: a longitudinal study. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 21, 525–546. doi: 10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<525::AID-JOB40>3.0.CO;2-T

Schweitzer, M. E., and Hershey, J. C. (2006). Promises and lies: restoring violated trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 101, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.05.005

Shultz, T. R., and Wells, D. (1985). Judging the intentionality of action-outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 21, 83–89. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.1.83

Sliwka, D. (2007). Trust as a signal of a social norm and the hidden costs of incentive schemes. Am. Econ. Rev. 97, 999–1012. doi: 10.1257/aer.97.3.999

Swap, W. C. (1991). When prosocial behavior becomes altruistic: an attributional analysis. Curr. Psychol.: Res. Rev. 10, 49–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02686780

Tirole, J. (1999). Incomplete contracts. Where do we stand? Econometrica 67, 741–781. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00052

Trivers, R. I. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–57. doi: 10.1086/406755

Wilson, D. S. (2015). Does Altruism Exist? Culture, Genes, and the Welfare of Others. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Keywords: helping behavior, prosociability, effort cost, social relationship, labor cost, altruism, social motivation, financial motivation

Citation: Arnestad MN, Glambek M and Selart M (2024) With a little profitable help from my friends: the relational incongruence of benefiting financially from prosocially motivated favors. Front. Behav. Econ. 3:1297601. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2024.1297601

Received: 20 September 2023; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 12 March 2024.

Edited by:

Thomas Post, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Martijn Stroom, Maastricht University, NetherlandsBin Dong, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 Arnestad, Glambek and Selart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mads Nordmo Arnestad, bWFkcy5uLmFybmVzdGFkQGJpLm5v

Mads Nordmo Arnestad

Mads Nordmo Arnestad Mats Glambek

Mats Glambek Marcus Selart

Marcus Selart