- 1The Institute for Applied Microeconomics, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

- 2Department of Corporate Development, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Past experimental studies have documented a positive effect of observability on prosocial behavior. However, little is known about spillover effects on subsequent, unobserved prosocial actions. This paper studies the dynamic effect of observability on prosocial behavior. We hypothesize a twofold positive effect. First, in accordance with previous literature, people should act more prosocially when being observed. Second, this increased level of prosociality should motivate an ongoing elevated altruistic attitude, in accordance with the concept of altruistic capital formation. We test our predictions by running two experiments in which subjects make a first donation decision either observably or anonymously. Subsequently, all subjects face a second anonymous donation decision. In general, we observe high rates of altruistic behavior. However, we find only weak positive effects of observability on first-stage prosocial behavior and no effects on second-stage prosocial behavior.

1. Introduction

Prosocial behavior is a pervasive facet of human interactions. Humans volunteer, give money to charities, donate blood, and help friends as well as strangers. All of these activities evoke personal costs but people are nonetheless willing to make sacrifices to increase social welfare (Charness and Rabin, 2002). Such behavior is often understood to reflect social preferences.1 Ample evidence suggests that social preferences positively affect economic success (Carpenter and Seki, 2011; Becker et al., 2012; Kosse and Tincani, 2020; Algan et al., 2022) and wellbeing (Dunn et al., 2008; Park et al., 2017) in several contexts. Policy makers and corporations may hence wish to foster the prevalence of social preferences to obtain its benefits. However, the current state of knowledge on the malleability and the development of social preferences provides only limited guidance.

We experimentally investigate how prosocial behavior, one expression of social preferences, can be fostered over time. One particular variable that can affect prosocial behavior is observability. It has repeatedly been shown that people behave differently when others witness their actions (e.g., Soetevent, 2005, 2011). In particular, being observed usually increases prosocial behavior because people want to be liked and respected by others (Ariely et al., 2009; Birke, 2020) or want to avoid resentment (DellaVigna et al., 2012; Andreoni et al., 2017; Butera et al., 2022). These studies report, however, only the change of behavior during the observation itself. Beyond that, little is known about the sustainability of these positive observability effects and it is unclear how being observed affects the dynamics of prosocial behavior. We contribute to the existing research by investigating spillover effects of being observed during the decision over a prosocial act on subsequent prosocial behavior. We hypothesize that observability not only increases immediate prosocial behavior but has positive spillover effects on later behavior as well.

This hypothesis is motivated by an approach to conceptualize the formation of altruistic attitudes that goes back to Aristotle. According to Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, virtues are formed through the practice of virtuous actions. In modern terminology, engaging in prosocial behavior becomes a habit and eventually changes people's self-image, meaning the way they think about themselves. They henceforth keep up the prosocial behavior in order to avoid cognitive dissonance (Akerlof and Dickens, 1982). This idea is captured by the concept of altruistic capital that states that past altruistic behavior accumulates altruistic capital that enables individuals to internalize how actions affect others and finally increases future altruistic behavior (Ashraf and Bandiera, 2017). Being observed while doing something good should therefore increase later prosocial behavior: Due to image concerns, being observed increases immediate prosocial behavior compared to a situation in which one is not observed. This builds up altruistic capital, and has therefore positive spillover effects on subsequent behavior. Moreover, performing good deeds in front of others makes a given action more salient, might intensify the experience and therefore potentially have stronger effects on a person's self-image adjustment. These image changes lead to a stronger increase of altruistic capital. We capture these mechanisms in a theoretical framework.

We conduct two laboratory experiments to test if observability of earlier prosocial actions influences later levels of prosocial behavior. The experiments differ in the currency of giving in the later period (either money or effort) and in the mode of observability (either one single observer or a multi-people audience). In Experiment A, we find that prosocial behavior weakly increases when subjects are observed. We do not find such a difference in Experiment B. Moreover, we find only an insignificant effect of early observability on subsequent prosocial behavior in both experiments.

We proceed as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, Section 3 describes the two experimental designs, Section 4 presents a theoretical model and derives hypotheses, Section 5 presents the results, and Section 6 discusses and concludes.

2. Literature

In economics, social preferences are traditionally understood to be persistent traits of individuals—complementing other dimensions of their personality (Becker et al., 2012). For example, they have been found to be partially transmitted from generation to generation (Nunn and Wantchekon, 2011; Dohmen et al., 2012). However, there likewise exists evidence that social preferences can be altered, for instance when interacting and receiving attention from a socially-minded mentor during childhood (Kosse et al., 2020). Moreover, altruistic behavior is highly context-dependent (Dana et al., 2007; Grossman, 2014; Exley, 2016; Grossman and van der Weele, 2017). Certain features may trigger people to behave less prosocially—for instance, when contexts provide individuals with cues that can serve as excuses for not behaving prosocially or when the responsibility for certain outcomes is diffused. At the same time, other contexts promote prosocial behavior (e.g., Shang and Croson, 2009; Powell et al., 2012; Kessler and Milkman, 2018).

People have been shown to have image concerns, meaning they behave differently when others are present and can observe their actions. This can be due to an opportunity to display a convenient and normatively desired behavior, which is or is not in line with own preferences. Regarding prosocial behavior, this implies that individuals tend to behave more prosocially when they are observed, allowing them to obtain social recognition for their actions (Alpizar et al., 2008; Andreoni and Bernheim, 2009; Ariely et al., 2009; Powell et al., 2012; Bašić et al., 2020). We seek to contribute to these findings by testing whether positive context effects of image concerns on prosocial behavior spill over to subsequent behavior, that is, spur circles of prosociality. In a broader context, we want to find out how prosocial behavior can be increased sustainably by gradually changing social preferences.

Our project builds on the theoretical and empirical literature on dynamics of prosocial and moral behavior. When deriving our theoretical model of altruistic capital, we follow Ashraf and Bandiera (2017) who argue that past altruistic behavior accumulates altruistic capital which increases future altruistic behavior. Bénabou and Tirole (2011) offer an underlying mechanism which could explain such an accumulation process. In their model, agents gain utility from high self-esteem and make inferences about their true unknown moral type by observing their own past moral or immoral actions. Moral behavior is interpreted as an investment in one's self-image. The model yields the conclusion that, under certain conditions, good actions can build up moral capital and lead to further good actions, whereas bad actions destroy moral capital and lock in further wrongdoing.

Empirical evidence on the development of altruistic behavior stems from psychological and recent economic research. There is evidence on people compensating early moral or immoral behavior; it is observed that early prosocial actions lead to decreased prosociality later on, whereas early selfish actions lead to an increase in prosocial behavior (moral licensing and cleansing, respectively; see Merritt et al., 2010; Blanken et al., 2015, for summaries). Schmitz (2019) reports results from an experiment on repeated social behavior in which subjects play a donation dictator game at two points in time. The second donation is smaller and this decrease is even stronger if both decisions happen within a day instead of having an extended period of one week between the two decisions. Grieder et al. (2021) also document donation behavior in line with moral licensing in two subsequent decisions. However, from an aggregate perspective, additional asks still increase total donations. Finally, Alt and Gallier (2022) document that negative spillovers of donation decisions depend on the incentive in the first donation decision. If the perceived (negative) pressure is high, moral licensing behavior is stronger.

However, there also exists evidence on the foot-in-the-door-effect, which refers to the phenomenon that the acceptance of a small initial request leads to a more probable acceptance of a larger request, which is made afterwards (Freedman and Fraser, 1966; DeJong, 1979; Beaman et al., 1983). It is argued that this effect shows due to a change in self-perception of individuals who accept the first small request, which therefore is in line with our argument. Relatedly, there is recent evidence for positive spillovers in the literature on environmental consumption. Alacevich et al. (2021) find a positive relationship between the introduction of household waste separation and waste avoidance by the household. However, the effect vanishes after 8 months. Jessoe et al. (2021) report a sizable effect of home water reports on both water reduction and electricity usage. Finally, Sherif (2023) documents increased donations for several environmental measures after incentivizing students in India to recycle single-use plastic.

Gneezy et al. (2012) experimentally investigate another dimension that is important for subsequent altruistic behavior. They claim that the development of a prosocial self-perception is only possible if prosocial acts involve personal costs. They find that people increase prosocial behavior only when the initial prosocial behavior was costly. Costless actions, in contrast, have no effect on subsequent prosocial decisions or can even decrease them. Our design incorporates this finding since subjects always have to invest time and effort or money in order to behave altruistically.

Building on these previous works on moral dynamics, social recognition, and the malleability of social preferences, we test not only the immediate effects of observability on prosocial behavior but in particular how later prosocial behavior is affected. We conjecture that social attention directed at one's good deeds leads to an adjustment of social image and stronger adjustments of self-image. We therefore expect subjects to increase their later prosocial behavior if they have been observed beforehand.

3. Experimental design

We investigate the causal effect of observability on present and future prosocial behavior by conducting two laboratory experiments. In both experiments, subjects face two sequential prosocial decisions within one session. We vary the observability of the subjects' first decision between treatments: in condition PUBLIC-PRIVATE, the first prosocial decision is observed by one observer or a group of observers, while the second prosocial decision is always made in private. In contrast, both decisions are made anonymously in condition PRIVATE-PRIVATE. We are primarily interested in second-stage prosocial behavior to evaluate the spillover effects of being observed on subsequent non-observed prosocial behavior. We run two variants of this experimental setting, which differ in the way donations are made and how observability is implemented.

Both experiments were conducted at the BonnEconLab using oTree (Chen et al., 2016) and hroot (Bock et al., 2014). Experiment A was conducted in August and September 2017 and a total of 240 subjects participated (including 37 subjects who served as observers). Experiment B was conducted in December 2017 and 77 subjects participated. Appendix 1 includes verbal and written instructions for both experiments.

3.1. Experiment A

In Experiment A, subjects participate in one of two roles. A minority of the subjects functions as observers in PUBLIC-PRIVATE, who do not make any decisions themselves but monitor the behavior of other subjects. The remaining subjects, irrespective of the treatment, take the same two consecutive donation decisions.

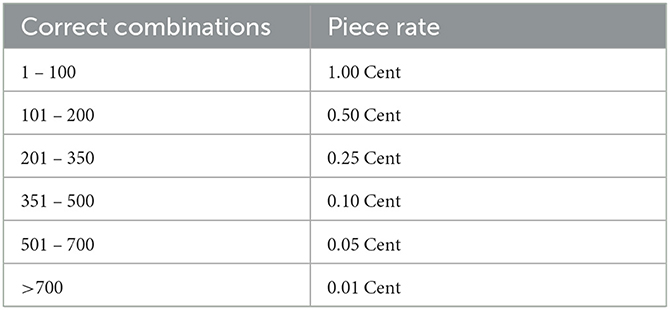

In Stage 1, subjects can work on a real-effort task called Counting Zeros (first implemented by Abeler et al., 2011) to generate a donation to a project of the charity SOS-Kinderdörfer. In this task, subjects face 15 × 10 - tables, with all 150 cells each containing either the digits 0 or 1. On each screen (see Figure A1 for a screenshot) subjects have to state the total number of zeros a table contains. Per correctly counted table,2 the generated donation increases by a specific piece rate, which decreases in the number of attempted tables (see Table 1). To prevent subjects from simply guessing the correct number, we subtract €0.05 from the total donation for incorrect answers.3 Subjects can freely choose to stop working at any time and can leave earlier when doing so. This allows for higher opportunity costs of exercising and hence more costly prosocial acts.4 There is a maximum time of 20 minutes and a maximum number of 25 tables, resulting in a maximum donation of €2.90.

Stage 2 consists of a double-blind dictator game. In this stage, subjects open an envelope which they already receive at the beginning of the experiment. This envelope contains the subjects' compensation of €5 for participating in the experiment.5 The envelope also contains written instructions and a smaller envelope. The instructions state that participants may leave any amount of the €5 in the small envelope to donate to a different project of the same charity as in Stage 1.6

We use a between-session treatment variation to prevent subjects from PRIVATE-PRIVATE to be aware of any social component of the experiment. Sessions are conducted in turns, each one lasting at most 30 minutes. In the following, the exact procedure of the two treatments is outlined.

PRIVATE-PRIVATE

For each PRIVATE-PRIVATE session, three participants are invited to the BonnEconLab. At the beginning, they receive the aforementioned envelope and the instruction to open it at the end of the experiment. Afterwards, they are sent to three separate rooms. They are told to choose their respective rooms themselves to ensure a double-blind procedure and complete anonymity. Instructions for Stage 1 are already displayed on the computer screens when subjects enter the room and they immediately start with the experiment. In Stage 1, subjects work on the Counting Zeros task described above to generate a donation between €0 and €2.90. After subjects decide to stop working, they have solved the maximum number of tables, or time is up, they are informed about their generated donation and open the envelope that leads to Stage 2, which was not announced beforehand. After deciding how much money to donate in the dictator game, subjects leave without talking to or seeing the experimenter or any of the other subjects again.

PUBLIC-PRIVATE

For each PUBLIC-PRIVATE session, we invite one additional subject, resulting in a total of four subjects per session. At the beginning of each session, all four subjects are seated at the same table and are asked to introduce themselves to each other by stating their first name and field of study.7 Subsequently, one subject is randomly selected to act as an observer whose only role is to monitor the performances of the remaining three subjects during Stage 1. After the observer is determined, he or she is separated from the other subjects and seated at a computer. On this computer, the other subjects' screens are displayed such that the observer can monitor their performances. Meanwhile, the other three subjects receive the same envelopes and the same information as subjects in PRIVATE-PRIVATE. Additionally, they are told that the observer will monitor their behavior and that each subject will have to report his or her outcomes to the observer in person. The observer is not aware of the envelopes to ensure the other subjects not feeling observed in Stage 2. From here on, the procedure of Stage 1 is identical to PRIVATE-PRIVATE. Only at the end of this stage, they are also asked to go to the observer and report their generated donation. Upon returning from the observer, they open the envelope which leads to Stage 2. The second stage proceeds in exactly the same way as in PRIVATE-PRIVATE, including complete anonymity. After deciding how much money to donate in the dictator game, subjects leave without talking to or seeing the experimenter, the observer or any of the other subjects again.

3.2. Experiment B

In Experiment B, for a tighter control of the dynamics of prosocial behavior, we change the nature of the donation decisions. Instead of using different types of decisions in Stages 1 and 2, we now use the same real-effort task in both stages. This allows detecting differences in prosocial behavior not only across treatments but also within-subjects between Stage 1 and Stage 2. Moreover, we change the observational mechanism. Subjects have to report their donation in front of all other subjects of the same session rather than reporting to a single observer to further increase the salience of observability.

We closely follow the design of Ariely et al. (2009) using their real-effort task Click for Charity in both stages. The task consists of alternately pressing the keys “X” and “Y” on the computer keyboard8 for five minutes. For each correct combination, a piece rate is donated to a project of the charity SOS-Kinderdörfer. Once again, the piece rate is concave and declines in the number of correct combinations (see Table 2). Figure A2 shows a screenshot of the task screen. Again, the projects differ between the two stages.

The experiment is conducted as follows: Subjects arrive at the laboratory and are randomly assigned within-session to one of the two treatments. When reading the instructions, subjects in PUBLIC-PRIVATE additionally learn that they will have to announce their first name and their generated donation from Stage 1 at the end of the experiment in front of all other participants of the session. Subjects in PRIVATE-PRIVATE do not receive this information and are not aware of the other condition until the very end of the experiment. After practicing the task, they work on it for five minutes to generate their Stage 1 donation. Note that none of the subjects is aware of Stage 2 during this phase. Only after finishing Stage 1, subjects receive written instructions for Stage 2, which follows the same procedure as Stage 1. However, now all subjects are specifically informed that this stage's donation is completely anonymous.

We also ask subjects for their level of happiness at the beginning and at the end (before the public announcement of donations) of the experiment. Participants receive a flat compensation of €6. Each session lasts at most 40 minutes and on average consists of 19 participants.

4. Theory and hypotheses

In this section, we derive a simple theoretical model and present the resulting hypotheses. According to Aristotle, people become virtuous by committing virtuous acts and thereby getting accustomed to it. We model this habitual formation with the assumption that people accumulate altruistic capital whenever doing something altruistic, following the approach of Ashraf and Bandiera (2017).

In period t = 1, 2, agent i chooses an altruistic action ai, t≥0 and a selfish action si, t≥0 where . The altruistic action generates social welfare W(ai, t) and the selfish action generates consumption utility U(si, t), but both actions create a cost c(si, t, ai, t, Ai, t) at the same time. W(.) and U(.) are increasing and concave in ai, t and si, t, respectively, and c(.) increases convexly in ai, t and si, t. The altruistic action ai, t does not only generate social welfare and create costs but also accumulates altruistic capital in the next period, denoted by Ai, t+1. Share u of the altruistic action increases social welfare in the same period, whereas share 1−u increases altruistic capital of the following period (this borrows from Lucas, 1988). Apart from this, altruistic capital builds up faster, the higher the parameter κt, which reflects a particular form of self-awareness. It reflects our understanding that higher image concerns make altruistic acts more salient and therefore enhance the internal habit formation process. Image effects are common to all agents but are situation-specific, as they depend, for instance, on the presence of an audience. In our experiment, we vary the effect of image in the first period between treatments, assuming that κt is increasing in public observability, that is . In particular, altruistic capital in period t is Ai, t = (1−u)κt−1ai, t−1+(1−δ)Ai, t−1, where δ∈(0, 1) captures the depreciation rate of altruistic capital.

We argue that greater altruistic capital reduces the cost of acting altruistically as one accommodates to altruistic behavior. Having a prosocial identity (due to self- and/or social image adjustments) makes behaving prosocially less costly since it reduces cognitive dissonance and because the decision process becomes less difficult. We therefore assume that altruistic capital decreases the marginal cost of acting prosocially, that is, ∂c(·)/(∂ai, t∂Ai, t) < 0.9

Finally, agent i's utility in period t is equal to U(si, t) + (σi+θt)W(uai, t)−c(si, t, ai, t, Ai, t). The utility increases proportionally in W for two reasons: First, the agent attaches a positive weight σi on W that represents her individual social preferences, such as pure altruism or warm glow. The second component, θt, expresses a further image effect, where an agent simply wants to make a better impression while being observed (social image). We exogenously vary the parameter in our experiment, and we assume . This image effect can be interpreted as the agent deriving utility from others thinking well of her. The agent seeks to maximize her utility by choosing ai, t.

Stage 1

As subjects are randomly assigned to treatments, we assume that previously accumulated altruistic capital and altruistic preferences, Ai, 1 and σi, are equally distributed for both treatment groups. Hence, the only difference between treatments consists of the social observability. In PUBLIC-PRIVATE, we increase the social image parameter θ1 and therefore the benefit of the generated social welfare.10 Consequently, the agent has a higher return of her altruistic act and chooses a larger action ai, 1.

Hypothesis 2. Subjects generate a greater donation in Stage 1 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE than in PUBLIC-PRIVATE.

Stage 2

In PUBLIC-PRIVATE, observability occurs only in Stage 1 while subjects make their first decision. The subsequent donation decision in Stage 2 is completely private for all subjects and κ2 and θ2 should therefore be similar for both treatment groups. Altruistic capital Ai, 2, however, is no longer equal as participants in PUBLIC-PRIVATE choose a larger action ai, 1 due to θ1 and experience an additional increase due to a higher κ1. This increases their altruistic capital stock with a higher rate, which in turn decreases the cost c(si, 2, ai, 2, Ai, 2) in period t = 2. A reduced cost makes it comparatively more attractive to engage in prosocial activities, which leads to our second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2. Subjects generate a greater donation in Stage 2 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE than in PUBLIC-PRIVATE.

5. Results

5.1. Experiment A

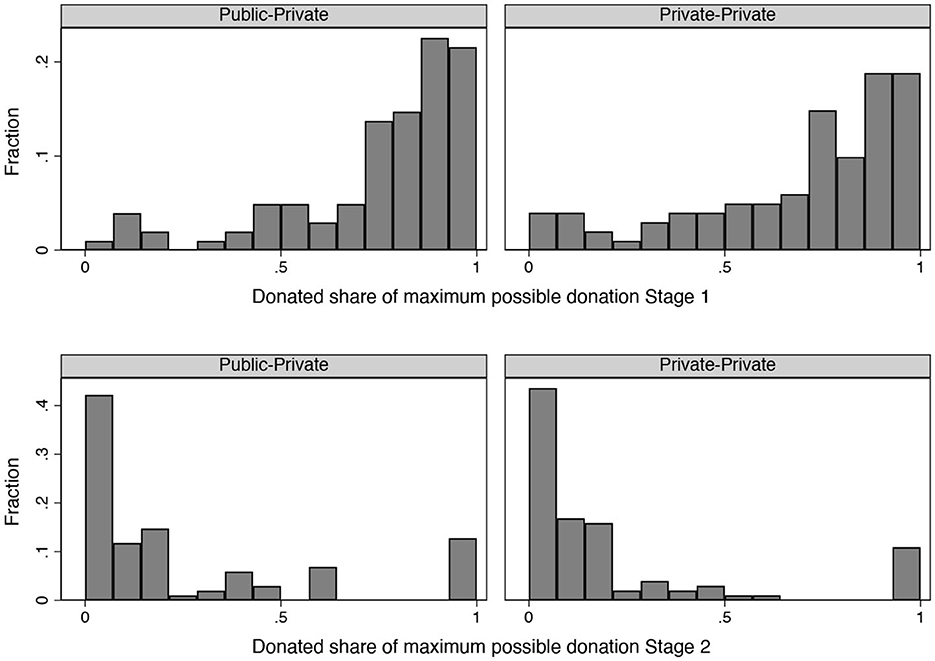

In Experiment A, a total of 203 subjects participate as decision makers, 102 subjects in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and 101 subjects in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. In Stage 1, in which subjects can generate a donation by correctly counting zeros in tables, about 75% of all subjects solve at least five tables correctly and subjects quit, on average, after 14.9 attempts. This results in an average donation of €2.18 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and €2.00 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE (out of a maximum of €2.90 if all 25 tables are solved correctly). In Stage 2, where subjects are no longer asked to spend time and effort but money, only 62% of subjects donate a positive amount at all, albeit 12% give their complete show-up fee of €5. The average donation is €1.30 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and €1.03 in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. Figure 1 displays donated shares of the maximum possible amount separately for the two treatment groups and for Stage 1 and Stage 2.

Figure 1. This figure displays histograms of the donated share of the maximum possible donations in Experiment A. The upper half denotes values for Stage 1, the lower half for Stage 2, both by treatment.

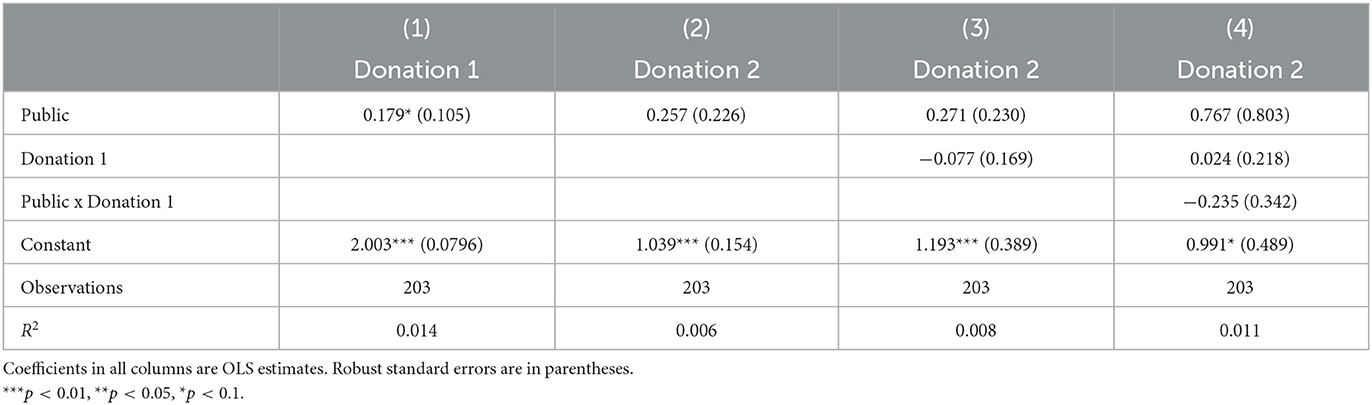

Table 3 reports OLS estimates. In Column (1), the Stage 1 donation is regressed on a treatment dummy, which is 1 if subjects are in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and 0 if they are in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. The coefficient is positive (subjects donate on average €0.18 more in PUBLIC-PRIVATE) and weakly significant. This is in line with Hypothesis 1. In Column (2), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the same treatment dummy. As stated in Hypothesis 2, the coefficient is positive (subjects donate on average €0.26 more in PUBLIC-PRIVATE) but not significant. In Column (3), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the treatment dummy, now additionally controlling for the Stage 1 donation. The coefficient of the dummy variable stays almost the same. The coefficient of the Stage 1 donation is close to zero, which suggests that a higher giving of Stage 1 does not per se induce higher giving in Stage 2 but observability itself induces higher giving. However, neither of the coefficients is significant. In Column (4), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the treatment dummy, the Stage 1 donation, and the product of the Stage 1 donation and the treatment dummy. The interaction term is negative, which could be a hint that for subjects in PUBLIC-PRIVATE the Stage 1 donation has a negative effect on the Stage 2 donation, speaking against a general altruistic capital effect. However, again, none of the coefficients is significant.

5.2. Experiment B

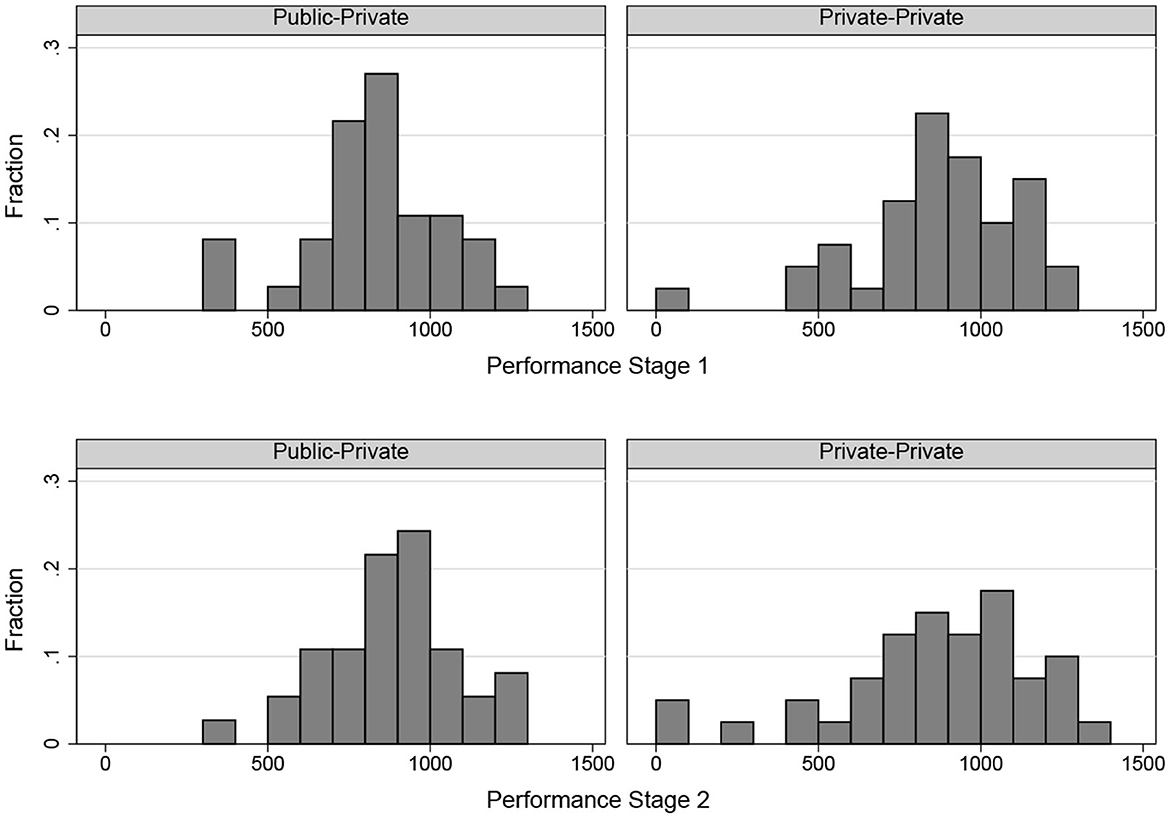

In Experiment B, a total of 77 subjects participate. 37 subjects are in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and 40 subjects in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. In this experiment, subjects generate two donations by working on the real-effort task Click for Charity twice. Figure 2 displays the distributions of number of clicks per subject separately for each treatment group and each stage. We show graphics for performance levels instead of donations, since the concave piece rate leads to a low variation in actual donations. Therefore, performance levels give a more accurate picture of differences in behavior.

Figure 2. This figure displays histograms of the performances in Experiment B. The upper half denotes values for Stage 1, the lower half for Stage 2, both by treatment.

As in the previous experiment, almost all subjects engage in the task and generate a donation larger than zero. The average donation (pressed pairs) in Stage 1 is €2.12 (837.14) in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and €2.10 (876.45) in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. We do not observe any decline in Stage 2 where the average donation (pressed pairs) is €2.13 (879.54) in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and €2.03 (858.1) in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. Note that in Stage 1 average donations are higher in PUBLIC-PRIVATE, whereas average key combinations are lower. This is possible due to the concave piece rate which increases donations strongly in the beginning and only weakly in the end. In PUBLIC-PRIVATE, subjects press a lower total number of key combinations than in PUBLIC-PRIVATE, but the minimum number of pressed pairs is higher. This results in slightly higher average donations.

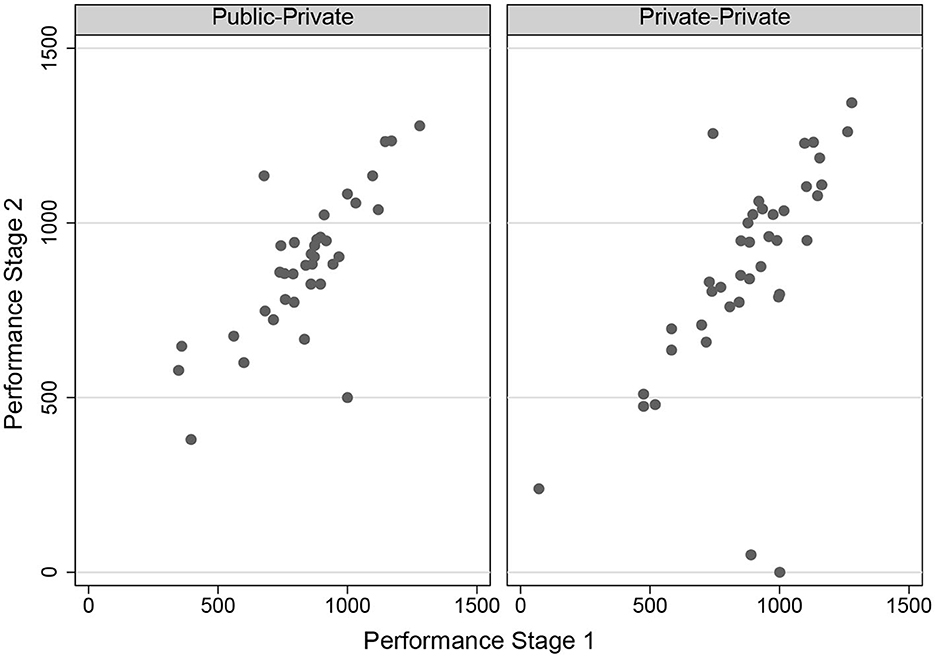

As Figure 3 illustrates, we find a strong positive correlation (ρ = 0.667) of performances between stages. Also, the difference of performances between Stage 1 and Stage 2 is not significantly different from zero (using a t-test, p = 0.637), which shows that subjects do not decrease their prosocial behavior over time.

Figure 3. This figure displays scatter plots of Stage 1 and Stage 2 performances for PUBLIC-PRIVATE on the left and PRIVATE-PRIVATE on the right.

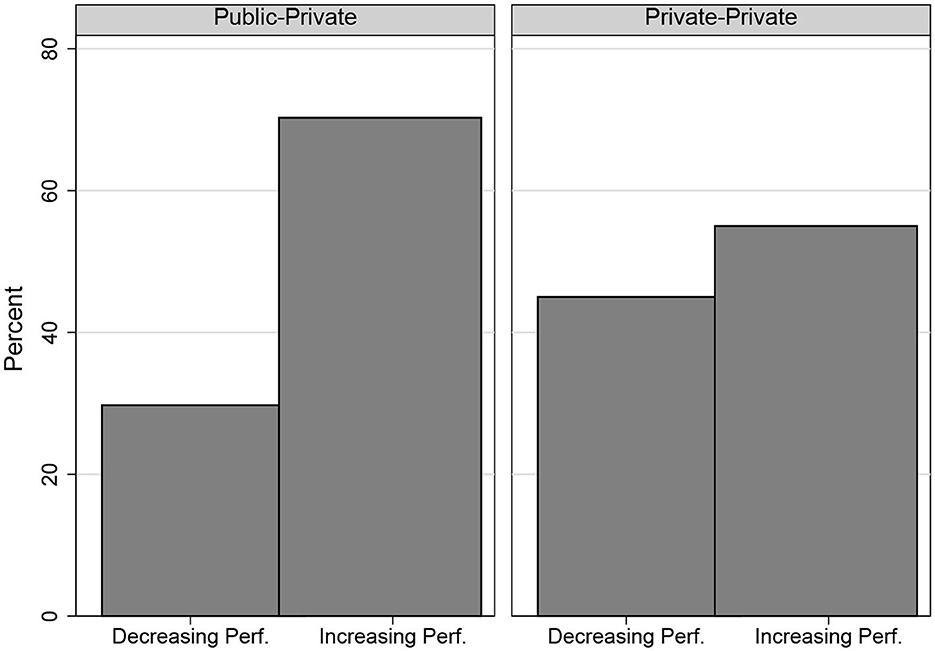

Analyzing individual changes in performances between Stage 1 and Stage 2, we find that in PUBLIC-PRIVATE around 70.3% of subjects increase their performance between Stage 1 and Stage 2, whereas only 55% of subjects do so in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. This finding is visualized in Figure 4. The difference of 15 percentage points between treatments goes in the expected direction but is not significant (Wilcoxon Rank sum Test, p = 0.17).

Figure 4. This figure displays the fraction of subjects who decrease or increase, respectively, their performance from Stage 1 to Stage 2 in Experiment B, separated by treatment.

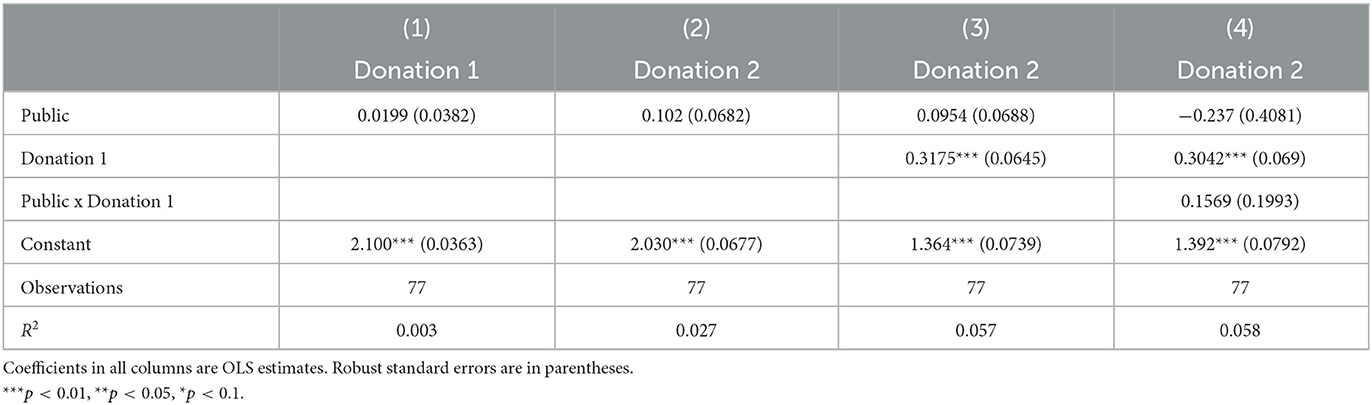

Table 4 replicates Table 3 for Experiment B. In Column (1), the Stage 1 donation is regressed on a treatment dummy, which is 1 if subjects are in PUBLIC-PRIVATE and 0 if they are in PUBLIC-PRIVATE. In Experiment B, the coefficient is also positive, but not significant. In Column (2), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the same treatment dummy. As stated in Hypothesis 2, the coefficient is positive (subjects donate on average €0.10 more in PUBLIC-PRIVATE), but not significant. In Column (3), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the treatment dummy, additionally controlling for the Stage 1 donation. The coefficient of the dummy variable stays almost the same compared to Column (2). However, the coefficient is still not significant. The coefficient of the Stage 1 donation is positive and highly significant which illustrates again that Stage 1 and Stage 2 donations are strongly correlated. In Column (4), the Stage 2 donation is regressed on the treatment dummy, the Stage 1 donation, and the product of the Stage 1 donation and the treatment dummy. Again, the coefficients of the treatment dummy and the interaction term are not significant.

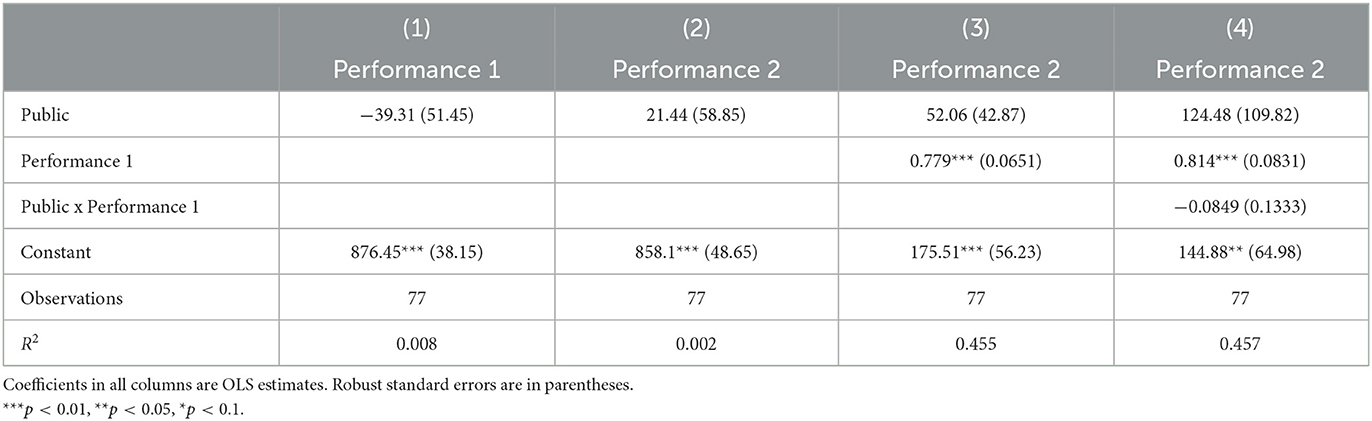

Table 5 reports similar regressions in the domain of performance. Again, there are no significant treatment effects and none of the hypotheses can be supported. Finally, we do not find a treatment difference in happiness.

6. Discussion

The aim of this paper is to investigate spillover effects of observability on later unobserved prosocial behavior, thereby studying the concept and prevalence of altruistic capital formation. We hypothesize that being observed during a good deed has a positive effect on subsequent prosocial behavior because people build up altruistic capital. People feel obliged to maintain their positive social and self-image, even in situations in which their actions are not observed by others, and keep on behaving prosocially. We do not find such behavior, independent of the concrete nature of the prosocial act, either requiring a donation of money or the investment of effort.

This result is not driven by a lack of prosocial behavior of subjects in the two PUBLIC-PRIVATE conditions but if anything by a substantial prosocial attitude of the control groups that do not face any social exposure in the first place. People are willing to (repeatedly) sacrifice own resources for social welfare, regardless of observability. This suggests other potential drivers of repeated prosocial activity: It is possible that people already have a high altruistic capital stock and a prosocial self-perception and thus do not react to further motivation.

This might also be the reason why social image as a trigger of stronger prosocial behavior cannot be established in our experiments. We do find only a weakly significant positive effect in Experiment A and an insignificant effect in Experiment B. This absence of a social image effect is unexpected, as we follow past studies in their approach. This is especially true for Experiment B where we closely follow the design of Ariely et al. (2009) but are unable to find similar effects. In contrast to their study, subjects in Stage 1 of our PUBLIC-PRIVATE treatment actually achieve a higher performance. Both treatment groups accomplish numbers that are similar to those in the public condition of Ariely et al.. Furthermore, we have enough statistical power: a treatment difference in performance similar to the one of Ariely et al. (on average 822 clicks in the public condition and 548 clicks in the private condition) would be significant at a significance level of 1% with our sample size. We use the same mechanism to implement social observability, as well as the same piece rates, even though the cutoffs are different as we decrease the piece rate in steps of 100 instead of 200. The increased concavity could potentially decrease the treatment difference in donations and therefore explain why we do not find the same results. However, we observe subjects to continue the task even if one click is worth only 0.01 Cent.11

Finally, we examine giving in Stages 1 and 2 in the PUBLIC-PRIVATE condition of Experiment B for potential relationships between these two stages, independent of any additional image effects. In contrast to Experiment A, participants have to exert the same task twice, which makes behavior between stages comparable. We observe a significantly positive relationship between performances in the two stages (see again Figure 3). This is in line with a preference for consistent moral behavior.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy - EXC 2126/1- 390838866. Funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through CRC TR 224 (Project A01) is gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Dohmen, Lorenz Goette, Lukas Kiessling, Sebastian Kube, Thomas Neuber, Sebastian Schaube, and Frederik Schwerter for numerous helpful comments and feedback. The paper is part of both authors' dissertations (Hofmeier, 2019; Strang, 2019). An earlier version of this paper has appeared in the ECONtribute Discussion Paper series.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2023.1220007/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Important manifestations of social preferences are, for instance, altruism (Becker, 1974, 1976), inequity aversion (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000), reciprocity (Rabin, 1993; Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger, 2004; Falk and Fischbacher, 2006), and warm glow (Andreoni, 1989).

2. ^We allow for a error margin of +/- 1.

3. ^The total amount cannot become negative.

4. ^As mentioned before, Gneezy et al. (2012) emphasize the importance of positive costs and Goerg et al. (2019) show that implicit costs are higher if subjects are allowed to quit the task and leave early.

5. ^Observers in PUBLIC-PRIVATE receive a flat payment of €5 as well.

6. ^The €5 are provided in coins, such that all donations between €0 and €5 in steps of 10 Cent are possible.

7. ^These personal interactions are used to create familiarity between subjects and have been used before. See, for instance, Gächter and Fehr (1999), Ewers and Zimmermann (2015).

8. ^Computer keyboards all have a German layout.

9. ^Ashraf and Bandiera (2017) assume that altruistic capital increases the marginal product of the altruistic action. Both assumptions are equivalent. We use cost reduction for the intuitive reason that habits reduce the cost of the decision process as well as of the action itself.

10. ^As the existence of Stage 2 is unknown when making the decision for ai, 1, subjects are treating the optimization problem of Stage 1 in isolation from Stage 2.

11. ^We do not believe that subjects are not capable of pressing more pairs in 5 min, as Ariely et al. (2009) themselves have a control condition in which subjects work for high monetary incentives and press, on average, 1,290 combinations, which is the maximum level we observe.

References

Abeler, J., Falk, A., Goette, L., and Huffman, D. (2011). Reference points and effort provision. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 470–492. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.2.470

Akerlof, G. A., and Dickens, W. T. (1982). The economic consequences of cognitive dissonance. Am. Econ. Rev. 72, 307–319.

Alacevich, C., Bonev, P., and Söderberg, M. (2021). Pro-environmental interventions and behavioral spillovers: Evidence from organic waste sorting in Sweden. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 108, 102470. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102470

Algan, Y., Beasley, E., Côté, S., Park, J., Tremblay, R. E., and Vitaro, F. (2022). The impact of childhood social skills and self-control training on economic and noneconomic outcomes: evidence from a randomized experiment using administrative data. Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 2553–2579. doi: 10.1257/aer.20200224

Alpizar, F., Carlsson, F., and Johansson-Stenman, O. (2008). Anonymity, reciprocity, and conformity: Evidence from voluntary contributions to a national park in Costa Rica. J. Public Econ. 92, 1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.11.004

Alt, M., and Gallier, C. (2022). Incentives and intertemporal behavioral spillovers: A two-period experiment on charitable giving. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 200, 959–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2022.05.028

Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving With Impure Altruism: Applications to Charity and Ricardian Equivalence. J. Political Econ. 97(6):1447–1458. doi: 10.1086/261662

Andreoni, J., and Bernheim, B. D. (2009). Social image and the 50-50 norm: a theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica. 77, 1607–1636. doi: 10.3982/ECTA7384

Andreoni, J., Rao, J. M., and Trachtman, H. (2017). Avoiding the ask: a field experiment on altruism, empathy, and charitable giving. J. Political Econ. 125, 625–653. doi: 10.1086/691703

Ariely, D., Bracha, A., and Meier, S. (2009). Doing good or doing well? Image motivation and monetary incentives in behaving prosocially. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 544–555. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.1.544

Ashraf, N., and Bandiera, O. (2017). Altruistic capital. Am. Econ. Rev.: Papers & Proceedings 107, 70–75. doi: 10.1257/aer.p20171097

Bašić, Z., Falk, A., and Quercia, S. (2020). Self-Image, Social Image and Prosocial Behavior. New York: Mimeo.

Beaman, A. L., Cole, C. M., Preston, M., Klentz, B., and Steblay, N. M. (1983). Fifteen years of foot-in-the door research: a meta-analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 9, 181–196. doi: 10.1177/0146167283092002

Becker, A., Deckers, T., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., and Kosse, F. (2012). The relationship between economic preferences and psychological personality measures. Annu. Rev. Econom. 4, 453–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110922

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interactions. J. Political Econ. 82, 1063–1093. doi: 10.3386/w0042

Becker, G. S. (1976). Altruism, egoism, and genetic fitness: economics and sociobiology. J. Econ. Lit. 14, 817–826.

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2011). Identity, morals, and taboos: beliefs as assets. Q. J. Econ. 126, 805–855. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr002

Birke, D. J. (2020). Anti-Bunching: A New Test for Signaling Motives in Prosocial Behavior. doi: 10.1257/rct.4809-1.1

Blanken, I., van de Ven, N., and Zeelenberg, M. (2015). A meta-analytic review of moral licensing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 540–558. doi: 10.1177/0146167215572134

Bock, O., Baetge, I., and Nicklisch, A. (2014). hroot: hamburg registration and organization online tool. Eur. Econ. Rev. 71, 117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.07.003

Bolton, G. E., and Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 166–193. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.1.166

Butera, L., Metcalfe, R., Morrison, W., and Taubinsky, D. (2022). Measuring the welfare effects of shame and pride. Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 122–168. doi: 10.1257/aer.20190433

Carpenter, J., and Seki, E. (2011). Do social preferences increase productivity? Field experimental evidence from fishermen in Toyama Bay. Econ. Inquiry. 49, 612–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2009.00268.x

Charness, G., and Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding Social Preferences with Simple Tests. Q. J. Econ. 117(3):817–869. doi: 10.1162/003355302760193904

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., and Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 9, 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2015.12.001

Dana, J., Weber, R. A., and Kuang, J. X. (2007). Exploiting moral wiggle room: experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory. 33, 67–80. doi: 10.1007/s00199-006-0153-z

DeJong, W. (1979). An examination of self-perception mediation of the foot-in-the-door effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2221–2239. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.12.2221

DellaVigna, S., List, J. A., and Malmendier, U. (2012). Testing for altruism and social pressure in charitable giving. Q. J. Econ. 127, 1–56. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr050

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., and Sunde, U. (2012). The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. Rev. Econ. Stud. 79, 645–677. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdr027

Dufwenberg, M., and Kirchsteiger, G. (2004). A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games Econ. Behav. 47, 268–298. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2003.06.003

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., and Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science. 319, 1678–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1150952

Ewers, M., and Zimmermann, F. (2015). Image and misreporting. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 13, 363–380. doi: 10.1111/jeea.12128

Exley, C. L. (2016). Excusing selfishness in charitable giving: the role of risk. Rev. Econ. Stud. 83, 587–628. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdv051

Falk, A., and Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games Econ. Behav. 54, 293–315. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2005.03.001

Fehr, E., and Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 114, 817–868. doi: 10.1162/003355399556151

Freedman, J. L., and Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: the foot-in-the-door technique. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 4, 195–202. doi: 10.1037/h0023552

Gächter, S., and Fehr, E. (1999). Collective action as a social exchange. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 39, 341–369. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00045-1

Gneezy, A., Imas, A., Brown, A., Nelson, L. D., and Norton, M. I. (2012). Paying to be nice: consistency and costly prosocial behavior. Manage. Sci. 58, 179–187. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1110.1437

Goerg, S. J., Kube, S., and Radbruch, J. (2019). The effectiveness of incentive schemes in the presence of implicit effort costs. Manage. Sci. 65, 4063–4078. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2018.3160

Grieder, M., Schmitz, J., and Schubert, R. (2021). Asking to give: moral licensing and pro-social behavior in the aggregate. SSRN Electron J. 1–37. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3920355

Grossman, Z. (2014). Strategic ignorance and the robustness of social preferences. Manage. Sci. 60, 2659–2665. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1989

Grossman, Z., and van der Weele, J. J. (2017). Self-image and willful ignorance in social decisions. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 15, 173–217. doi: 10.1093/jeea/jvw001

Hofmeier, J. (2019). Four economic experiments on social preferences. PhD thesis, Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn.

Jessoe, K., Lade, G. E., Loge, F., and Spang, E. (2021). Spillovers from behavioral interventions: experimental evidence from water and energy use. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 8, 315–346. doi: 10.1086/711025

Kessler, J. B., and Milkman, K. L. (2018). Identity in charitable giving. Manage. Sci. 64, 845–859. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2016.2582

Kosse, F., Deckers, T., Pinger, P., Schildberg-Hörisch, H., and Falk, A. (2020). The formation of prosociality: causal evidence on the role of social environment. J. Political Econ. 128, 434–467. doi: 10.1086/704386

Kosse, F., and Tincani, M. M. (2020). Prosociality predicts labor market success around the world. Nat. Commun. 11, 5298. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19007-1

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 22, 3–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., and Monin, B. (2010). Moral self-licensing: when being good frees us to be bad. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4, 344–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00263.x

Nunn, N., and Wantchekon, L. (2011). The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. Am. Econ. Rev. 101:3221–3252. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.7.3221

Park, S. Q., Kahnt, T., Dogan, A., Strang, S., Fehr, E., and Tobler, P. N. (2017). A neural link between generosity and happiness. Nat. Commun. 8:15964. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15964

Powell, K. L., Roberts, G., and Nettle, D. (2012). Eye images increase charitable donations: evidence from an opportunistic field experiment in a supermarket. Ethology. 118, 1096–1101. doi: 10.1111/eth.12011

Rabin, m. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 83, 1281–1302.

Schmitz, J. (2019). Temporal dynamics of pro-social behavior: an experimental analysis. Experim. Econ. 22, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10683-018-9583-2

Shang, J., and Croson, R. (2009). A field experiment in charitable contribution: the impact of social information on the voluntary provision of public goods. Economic J. 119, 1422–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02267.x

Sherif, R. (2023). Are Pro-environment Behaviours Substitutes or Complements? Evidence from the Field. Working Paper. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3799970

Soetevent, A. R. (2005). Anonymity in giving in a natural context—a field experiment in 30 churches. J. Public Econ. 89, 2301–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.002

Soetevent, A. R. (2011). Payment Choice, Image Motivation and Contributions to Charity: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Am. Econ. J. 3, 180–205. doi: 10.1257/pol.3.1.180

Keywords: prosocial behavior, donation, moral licensing, altruistic capital, social preferences, lab experiment

Citation: Hofmeier J and Strang L (2023) Image concerns and the dynamics of prosocial behavior. Front. Behav. Econ. 2:1220007. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2023.1220007

Received: 09 May 2023; Accepted: 14 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Ximeng Fang, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Harald Mayr, University of Zurich, SwitzerlandJan Schmitz, Radboud University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2023 Hofmeier and Strang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louis Strang, c3RyYW5nQHdpc28udW5pLWtvZWxuLmRl

Jana Hofmeier1

Jana Hofmeier1 Louis Strang

Louis Strang