94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Artif. Intell., 14 April 2021

Sec. Medicine and Public Health

Volume 4 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2021.638410

This article is part of the Research TopicAI Driven Bioinformatics Applications: Highlights from the Arkansas Bioinformatics Consortium 2020View all 7 articles

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a common reason for the withdrawal of a drug from the market. Early assessment of DILI risk is an essential part of drug development, but it is rendered challenging prior to clinical trials by the complex factors that give rise to liver damage. Artificial intelligence (AI) approaches, particularly those building on machine learning, range from random forests to more recent techniques such as deep learning, and provide tools that can analyze chemical compounds and accurately predict some of their properties based purely on their structure. This article reviews existing AI approaches to predicting DILI and elaborates on the challenges that arise from the as yet limited availability of data. Future directions are discussed focusing on rich data modalities, such as 3D spheroids, and the slow but steady increase in drugs annotated with DILI risk labels.

DILI is a common cause of acute liver failure and one of the main reasons for failed clinical trials and for the withdrawal of drugs (Kaplowitz, 2004; Senior, 2007). Hepatotoxicity can be anticipated in some cases. For example, acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol) is known to damage the liver when used beyond the recommended dose (Lancaster et al., 2015). However, other DILI events are considered idiosyncratic; that is, they are rare and difficult to predict (Hoofnagle and Björnsson, 2019). Research directions such as the investigation of reliable biomarkers (Wang et al., 2009) and the development of AI methods (Przybylak and Cronin, 2012; Chen et al., 2014) aim to improve the understanding of DILI mechanisms and to anticipate hepatotoxicity early in the drug development process.

We elaborate on the latter by providing a review of the state of the art in AI for DILI prediction, focusing particularly on approaches based on machine learning (ML). From an ML perspective, DILI prediction is generally cast as a supervised learning problem (Murphy, 2012, Section 1.1.1). Let us consider a chemical compound c, the hepatotoxicity risk of which can be represented by a scalar

The remainder of this review article is divided into four sections. Section 2 presents the main datasets that list compounds and their hepatotoxicity risk (

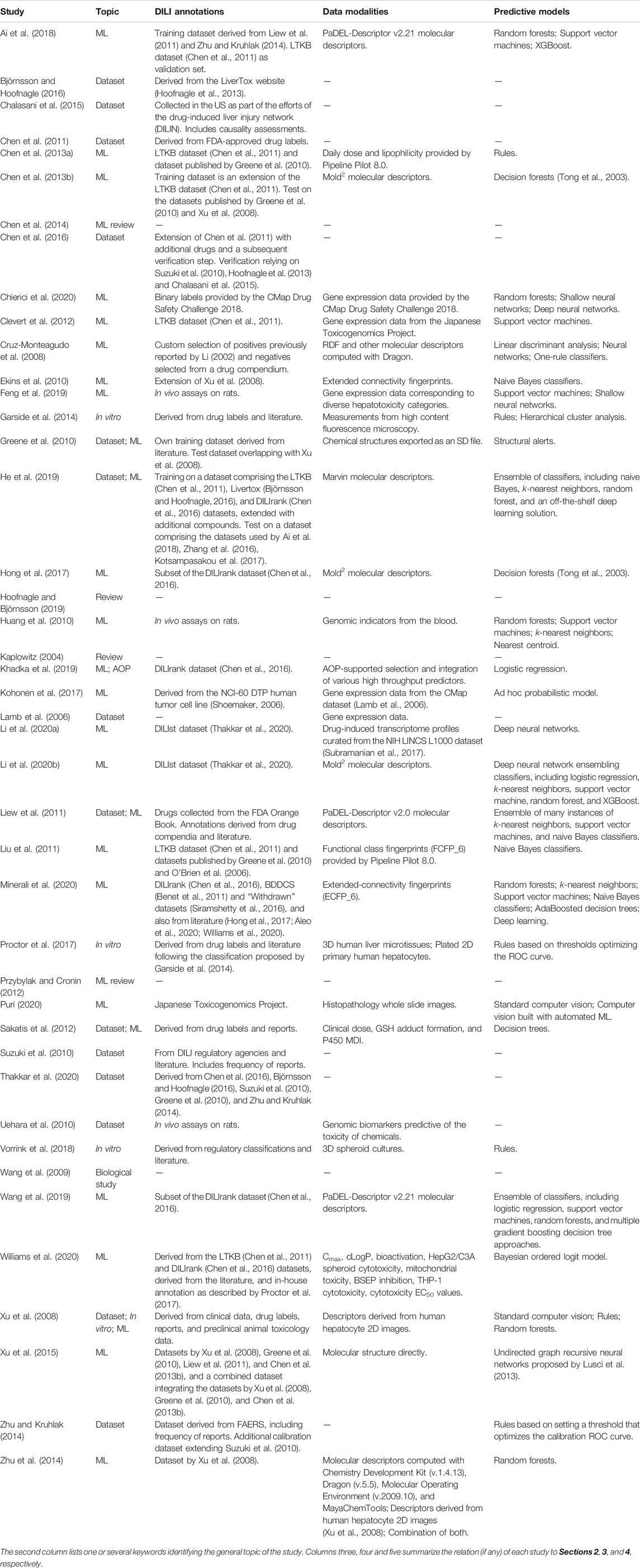

TABLE 1. Scientific studies considered in this review ordered alphabetically by author name (disregarding the year of publication).

We describe the main DILI annotation datasets that are publicly available, more specifically, categorizations of drugs based on their DILI risk in humans under medication (Chen et al., 2016). DILI annotations are necessary not only to train supervised machine learning models, but also to evaluate the performance of any predictive model (even of simple models such as structural alerts).

Xu et al. (2008) assembled a dataset of DILI annotations to validate a proposed cellular-imaging-based testing strategy. The dataset contained 344 drugs and chemicals with annotations derived from verified clinical hepatotoxicity data, drug labels, reports, and preclinical animal toxicology data. The annotation scheme distinguished between DILI “positive” and DILI “negative.” Ekins et al. (2010) used the dataset by Xu et al. (2008) to train naive Bayes classifiers. These were then tested on an additional dataset of 237 compounds which had already been curated by Xu et al. together with the initial dataset, but had not been available for in vitro testing at that time. Greene et al. (2010) extended the dataset by Xu et al. (2008) to a total of 626 compounds in total. Furthermore, they modified the annotation scheme, splitting the negative cases into “no evidence” and “weak evidence” of hepatotoxicity.1 The dataset was used to evaluate the performance of a structural-alert-based DILI prediction model.

Suzuki et al. (2010) collected a dataset of 319 drugs associated with hepatotoxicity. The sources of information were DILI registries from Spain, Sweden, and the US, studies of acute liver failure in these countries, and other published literature. The collection was supplemented with the frequency of liver adverse events reported in the World Health Organization VigiBase database (Lindquist, 2008). Zhu and Kruhlak (2014) took a subset of 177 drugs from this dataset and extended it with 105 drugs presumed to be DILI negatives based on the absence of warnings on PubMed2 and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MedWatch (Kessler et al., 1993) after more than five years on the market. This dataset was used as a calibration set to develop a simple DILI prediction model. Zhu and Kruhlak also constructed another dataset of DILI annotations by querying the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database.3

The LiverTox dataset provides information on drug, dietary supplement and herbal-induced liver injury (Hoofnagle et al., 2013). The main body of the dataset is a collection of drug hepatotoxicity records, but additional resources are provided to support the critical study of DILI. Importantly, causality assessment instruments, such as the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) (Danan and Teschke, 2019) and the Drug Induced-Liver Injury Network Causality Process (Fontana et al., 2009), are presented and discussed.

Björnsson and Hoofnagle (2016) conducted a critical analysis of 671 distinct drugs reported in the LiverTox dataset, and categorized them according to the number of published reports of idiosyncratic liver injury. Case reports in specific categories were reanalyzed using RUCAM. Chen et al. (2016) built on this categorization to improve the accuracy of drug-label-based annotations by incorporating evidence of causality. Thakkar et al. (2020) also used it but to increase the size of their dataset.

Chen et al. (2011) compiled the so-called “LTKB” dataset, which was based exclusively on drug labels retrieved from DailyMed.4 The rationale behind this approach was that drug labels implicitly integrate information on causality, incidence, and severity from trials, existing literature, and reports. Furthermore, drug labels must be reviewed regularly, and thus the annotations can be kept up to date. A classification by concern level was developed using three labels: “most-DILI,” “less-DILI,” and “no-DILI” concern.

The LTKB dataset, which consisted of 287 drugs, was later extended by refining the classification scheme and including additional drugs (Chen et al., 2016). The new classification scheme included whether drugs had been verified as the cause of DILI in humans, and assigned four risk levels: three corresponded to those of the LTKB dataset, but with verification, while the fourth one covered drugs for which the DILI annotation was ambiguous. The verification relied on published studies which had focused on causality assessment (Suzuki et al., 2010; Hoofnagle et al., 2013; Chalasani et al., 2015). More drugs were included in the dataset by considering drugs approved by the FDA over a longer time frame. This new version of the dataset, dubbed “DILIrank,” included 1,036 marketed drugs, 254 of which were annotated as being ambiguous.

Thakkar et al. (2020) further extended the DILIrank dataset by carefully incorporating drug annotations from previously published datasets (Greene et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2010; Zhu and Kruhlak, 2014; Björnsson and Hoofnagle, 2016). The authors took the DILIrank dataset as a basis, and drugs from the other datasets were incorporated when sufficient agreement between annotations was found. The extended dataset, named “DILIst,” contains 1,279 drugs classified according to a binary scheme.

Other DILI annotation datasets exist, but have not been used as routinely in subsequent studies. Cruz-Monteagudo et al. (2008) curated a dataset of 74 drugs by combining DILI positives from a previously published collection (Li, 2002) with drugs manually selected as not having an association with hepatotoxicity according to a drug compendium. Liew et al. (2011) assembled a list of 1,274 drugs from the FDA Orange Book5 with DILI annotations derived from the Micromedex Health Care Series and with additional compounds from literature reports. Other studies compiled custom datasets with a few hundred datapoints and annotations based on the existence or absence of hepatotoxicity reports, on previous literature, and on expert opinion (Sakatis et al., 2012; Garside et al., 2014; Proctor et al., 2017; Vorrink et al., 2018).

Chemical compounds can be described using various data modalities, such as chemical structure, gene expression profiles, and cell and tissue images. ML methods are generally not limited to a specific modality when producing a DILI prediction model. For this reason, we provide an overview of the most common data modalities used in DILI prediction, regardless of the specific ML method considered.

Analysis of the chemical structure of compounds is frequently used and has the notable advantage of naturally always being available. This approach, generally referred to as quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, is widely applied in chemoinformatics, also beyond the prediction of DILI risk. A well-established pipeline first computes feature vectors, typically called “molecular descriptors,” which encode structural properties of the compounds. These descriptors are then passed to a ML model of choice. Various kinds of descriptors have been proposed, ranging from simple characteristics, such as molecular weight and number of carbon atoms, to more sophisticated encodings, which are typically called “molecular fingerprints” (Morgan, 1965; Quist, 2006; Rogers and Hahn, 2010).

A number of software implementations exist to compute standard molecular descriptors. In many cases, authors specify their set of descriptors by referring to the software implementation employed. Cruz-Monteagudo et al. (2008) computed radial-distribution-function descriptors with the DRAGON software (Mauri et al., 2006). Liu et al. (2011) employed functional class fingerprints (FCFP_6) provided by the Pipeline Pilot 8.0 software. Chen et al. (2013a) also employed Pipeline Pilot 8.0, but in this case to estimate drug lipophilicity. Liew et al. (2011), Ai et al. (2018) and Wang et al. (2019) used descriptors provided by the PaDel-Descriptor software (Yap, 2011). Chen et al. (2013b) and Hong et al. (2017) used Mold2 descriptors (Hong et al., 2008). He et al. (2019) computed descriptors with the Marvin software.6

Some ML methods can directly process the chemical structure of compounds. Xu et al. (2015) followed the approach proposed by Lusci et al. (2013), where molecular graphs are passed directly to a recursive neural network. For general (not DILI-specific) target prediction tasks, Mayr et al. (2018) used two such ML methods: one processed SMILES strings (Weininger, 1988) by using long short-term memory recurrent neural networks (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997), and the other processed molecular graphs with graph convolutional neural networks (Duvenaud et al., 2015).

To complement and improve chemical-structure-based models, additional information in the form of gene expression data can be useful (Martin et al., 2002; Klambauer et al., 2015). In this context, there has been notable work investigating the advantage of considering genomic biomarkers for DILI prediction. Huang et al. (2010) successfully used genomic indicators to predict acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Clevert et al. (2012) proposed a pipeline with suitable pre-processing steps for DILI prediction using data from the Japanese Toxicogenomics Project (TGP) (Uehara et al., 2010). Feng et al. (2019) also used data from the TGP and proposed a DILI prediction model based on a feed-forward neural network. Kohonen et al. (2017) predicted DILI using a model which leveraged both the CMap dataset and the NCI60 cell line screen (Shoemaker, 2006). Chierici et al. (2020) utilized a subset of the CMap dataset of two specific cell lines, as provided in the CMap Drug Safety Challenge 2018,7 although the authors found that these data were insufficient for DILI prediction. Li et al. (2020a) proposed a DILI prediction model based on a deep neural network, which takes as input transcriptomic profiles of human cell lines derived from the LINCS L1000 dataset (Subramanian et al., 2017).

Xu et al. (2008) developed an in vitro testing strategy for DILI prediction based on features measured by high-content cellular imaging in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Of a total of eight features extracted using standard computer vision algorithms, the features “mitochondrial damage,” “oxidative stress,” and “intracellular glutathione” were found to be the most important for DILI prediction. Zhu et al. (2014) further investigated the predictive power of this imaging data and compared it to using molecular descriptors alone, or a combination of imaging data and molecular descriptors.

Garside et al. (2014) investigated a number of previously proposed hepatotoxicity prediction assays, which utilized either HepG2 cells, HepG2 cells in the presence of rat S9 fraction, or isolated human hepatocytes. Images were acquired by means of high-content fluorescence microscopy.

Puri (2020) used histopathology whole-slide images to train a computer vision system with automated ML. The system was able to predict whether images corresponded to 1 of 10 drugs, and this was interpreted as an ability to discriminate between DILI injury patterns. However, the usefulness of this system is limited due to the absence of DILI risk predictions and the reduced chemical space considered.

3D cell cultures have gained attention over 2D cell cultures (Huh et al., 2011): they grow longer, are more stable and reflect actual liver responses more accurately, therefore having higher predictive power (Messner et al., 2013; Proctor et al., 2017; Vorrink et al., 2018). Combining these with physicochemical and exposure variables, and with data from other in vitro assays, Williams et al. (2020) considered the outcome of an HepG2/C3A spheroid cytotoxicity assay for their DILI prediction model. 3D cultures can not only be employed as purely biological assays; they are also compatible with imaging technologies.8

To our knowledge, neither 2D nor 3D imaging technologies have to date been used in combination with advanced computer vision techniques based on deep learning.

We review the main DILI prediction models proposed to date. For the sake of clarity, we categorize them into three main categories: rules and knowledge-based systems, shallow ML methods, and deep learning methods. Rules and knowledge-based systems rely on explicitly coded decision rules. This is in contrast to ML methods, the decision mechanisms of which are implicitly defined and obtained by means of optimization techniques. Examples of shallow ML methods are naive Bayes classifiers and random forests. Deep learning methods are ML methods based on the so-called “deep” neural networks, which are considered to be those with at least two hidden layers (Delalleau and Bengio, 2011; Maas et al., 2012).

DILI risk can be predicted from in vitro assays and simple decision rules. Garside et al. (2014) and Vorrink et al. (2018) considered that an in vitro assay yielded a positive prediction when its outcome differed significantly from the control value, going on to evaluate the predictive power of this decision rule by means of the usual classification metrics. Similarly, Proctor et al. (2017) built a classifier by selecting a threshold for each assay such that the resulting ROC curves were optimized.

Greene et al. (2010) proposed a predictive model based on structural alerts, that is, a system based on expert knowledge of which chemical substructures are related to hepatotoxicity. Chen et al. (2013a) analyzed the effect of daily dose and lipophilicity on hepatotoxicity. They found the “rule-of-two,” by which drugs with daily doses ≥100 mg and logP

Xu et al. (2008) explored rule-based systems but achieved the best predictive performance by processing their proposed imaging features with a random forests model (Ho, 1995; Breiman, 2001). Subsequent work by Zhu et al. (2014) also used random forests, in this case within a 5-fold cross-validation model selection scheme. Chen et al. (2013b) built predictive models for DILI using decision forests (Tong et al., 2003) with 2,000 repetitions of 10-fold cross-validation for model selection. Decision forests differ from random forests in that each tree uses the whole training set and an explicit selection of features. This work was based on the LTKB dataset, but Hong et al. (2017) extended it to the DILIrank dataset.

Ekins et al. (2010) used a naive Bayes classifier with various types of molecular fingerprints. Similarly, Liu et al. (2011) used naive Bayes classifiers with molecular fingerprints, but in this case an independent classifier was trained for each of 13 hepatotoxic side effects. A final classifier was derived by means of a consensus strategy. Kohonen et al. (2017) introduced an ad hoc probabilistic model for the toxicogenomic space based on the latent Dirichlet allocation model (Blei et al., 2003). Williams et al. (2020) proposed a probabilistic ordered logit model that distinguishes between three increasing levels of DILI risk.

Cruz-Monteagudo et al. (2008) provided an evaluation of DILI prediction models that are based on various ML methods, namely a classifier based on a single attribute (Holte, 1993), linear discriminant analysis, and neural networks. Liew et al. (2011) proposed a DILI prediction model that consists of an ensemble of 617 base classifiers. These base classifiers were numerous instances of k-nearest neighbors classifiers, naive Bayes classifiers, and support vector machines (Cortes and Vapnik, 1995), each of which trained with a different subset of molecular descriptors. The final ensemble model was selected using 5-fold cross-validation.

Despite the rise of deep learning over the last decade, only few approaches to DILI prediction are based on this technology. Lusci et al. (2013) introduced undirected graph recursive neural networks (UG-RNNs) to predict the aqueous solubility of drug-like molecules. UG-RNNs bridge the gap between molecules (described as undirected cyclic graphs) and recursive neural networks (expecting directed acyclic graphs). In hindsight, this method can be regarded as a precursor of the now successful family of convolutional neural networks for graph structures (Duvenaud et al., 2015). Xu et al. (2015) employed UG-RNNs for DILI prediction. They also evaluated feed-forward neural networks of various depths, using PaDEL or Mold2 descriptors as input. UG-RNNs were found to perform best, followed by deep feed-forward neural networks and then by shallow feed-forward neural networks.

He et al. (2019) proposed an ensemble DILI prediction model which included deep neural networks. However, the only information provided about the deep neural network component was that it was implemented within the Deeplearning4j9 framework. Chierici et al. (2020) investigated deep learning architectures for DILI prediction using toxicogenomics data. They compared deep and shallow neural networks and random forests classifiers in terms of performance. The conclusion of this work was ambiguous. The authors claimed that the dataset used, published in the context of the CMap Drug Safety Challenge 2018, was not rich enough to build predictive models for DILI.

Li et al. (2020a) proposed a DILI prediction model consisting of a deep neural network which leveraged transcriptomic profiles of human cell lines. It outperformed other shallow ML methods, namely k-nearest neighbors, support vector machines and random forests. In another study, the same authors proposed an ensemble prediction model where a deep neural network aggregated the DILI risk probabilities predicted by roughly 500 base classifiers (Li et al., 2020b). The base classifiers were numerous instances of logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors, support vector machines and random forests, and each used Mold2 descriptors as input. The ensemble model outperformed the individual base classifiers, and it also outperformed a deep neural network which directly used Mold2 descriptors as input.

DILI is a common cause of liver failure, failed clinical trials, and withdrawal of drugs from the market. This work has reviewed the state of the art of AI approaches to predicting DILI, focusing on the approaches that are based on ML methods. Below, we discuss open challenges and future research directions.

ML approaches to DILI prediction are limited by the availability of DILI annotations. As mentioned in Section 2, the DILIst dataset, which is one of the largest and most comprehensive DILI annotation dataset, comprises only 1,279 drugs (Thakkar et al., 2020). The DILIst dataset is orders of magnitude smaller than benchmarking datasets in drug discovery (Mayr et al., 2018), and even smaller compared to benchmarking datasets in other AI application domains such as computer vision (Deng et al., 2009) and natural language processing (Vaswani et al., 2017), which can contain millions of data points. From an ML perspective this is critical, especially for deep learning methods, the remarkable success of which is presumably due to the access to large amounts of data (Goodfellow et al., 2016, Section 1.2.2). However, this limitation is a consequence of the also limited number of available drugs overall. Indeed, the latest release of DrugBank (version 5.1.8) lists a total of 14,331 drugs, only 2,677 of which are approved small molecule drugs.10

Despite the efforts of the research community to better understand its causes, DILI cannot yet be fully explained. Particularly for the cases considered idiosyncratic, which are very infrequent and lack a clear dose-response relationship (Björnsson and Hoofnagle, 2016), it can be challenging to annotate the DILI risk unambiguously. ML methods, and especially deep learning, excel at uncovering salient patterns from data. However, even if they exist, patterns obscured by noisy annotations can be difficult to reveal. Some of the reviewed studies carried out permutation tests, mostly y-randomization (Rücker et al., 2007), to verify that the proposed models were indeed superior to random ones (Liew et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2014; He et al., 2019). Research in the domain of aleatoric uncertainty estimation (Brando et al., 2019) may provide further help in identifying such effects.

Another consequence of the complexity of DILI is the variety of published risk classification schemes. These are generally ordered from less to more DILI risk, and are divided into two or more severity levels. The existence of different classification schemes is not problematic in itself, because it is possible to employ binary and multi-class prediction models depending on the classification scheme under consideration. Even various classification schemes can be leveraged simultaneously by means of multitask learning (Mayr et al., 2018). However, DILI annotations reported in various datasets are not always reconcilable with each other (Thakkar et al., 2020), which is clearly problematic for model development. An effort towards standardization of classification schemes and annotations will be essential to the development of ML methods for DILI prediction.

The standardization of training and test splits is also necessary. Consider the following example. Li et al. (2020a) and Li et al. (2020b) both used the DILIst dataset (Thakkar et al., 2020) to build predictive models. However, Li et al. (2020a) split the dataset according to the availability of transcriptomic profiles, while Li et al. (2020b) split it according to the initial year when the FDA approved the drugs. The predictive performance results obtained on these different splits cannot be compared. Consider another example. Li et al. (2020b) provided further predictive performance results using other datasets as the independent test set. Among others, they used the dataset published by Greene et al. (2010), but subtracted the drugs that also occurred in their training set in order to obtain a truly independent test set. This operation reduced the dataset originally published by Greene et al. (2010) from 209 DILI positives and 111 DILI negatives to only 52 DILI positives and 28 DILI negatives. The performance results obtained on the reduced version of the dataset cannot be compared to other results obtained on the original dataset.

Taken together, a fair comparison of the numerous DILI prediction models proposed to date requires the standardization of datasets, also in terms of fixed training and test splits. The FDA is leading this endeavor, with a continuous line of studies consolidating DILI classification schemes and extending the list of annotated drugs available (Chen et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2016; Thakkar et al., 2020).

Several of the DILI prediction models reviewed are based exclusively on exploiting the chemical structure of compounds. While the natural availability of structural information makes this approach very flexible, it can also fall short. Some of the adverse reactions considered idiosyncratic may be undetectable from the chemical structure alone, but might be predictable if genomic data is also considered. In this context, the reviewed studies focusing on the exploitation of gene expression data (Huang et al., 2010; Clevert et al., 2012; Kohonen et al., 2017; Chierici et al., 2020) are particularly relevant to increase the understanding of the possible dependence of idiosyncratic DILI on genetic host factors (Stephens and Andrade, 2020). Complementarily, Khadka et al. (2019) investigated the potential of the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework to improve the selection and integration of various high throughput predictors relevant to DILI prediction. The authors focused on DILI risk assessment, but the AOP framework can address other types of chemical safety assessment (Wittwehr et al., 2017).

We also see an opportunity for improvement in the exploitation of in vitro 2D and 3D imaging data, namely by using advanced deep-learning-based computer vision methods. Computer vision has progressed remarkably fast in recent years, also in the domain of biomedical imaging (Esteva et al., 2017). However, the image-based predictive models for DILI proposed thus far generally rely on standard computer vision techniques (Xu et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2014). Puri (2020) used an automated ML engine to train a deep learning classifier for histopathology images, but no details of the model architecture were shared. The number of drugs with 2D, and especially 3D, imaging data available is as yet limited. The acquisition of imaging data will be necessary to enable progress in this area.

Returning to DILI prediction models that are based on the chemical structure of compounds, while we find that deep learning methods have been proposed, they neither show an outstanding improvement in predictive performance (He et al., 2019; Minerali et al., 2020), nor have they been able to replace in vitro or in vivo tests. Generally, the proposed deep learning methods were based on processing pre-calculated molecular descriptors. Only Xu et al. (2015) considered and end-to-end approach, building on the UG-RNN method (Lusci et al., 2013), which was able to directly process the chemical structure of compounds and implicitly derive suitable molecular representations. In this regard, recent advances in graph convolutional neural networks (Gilmer et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019)—which are also end-to-end—should be investigated for DILI prediction.

Overall, we envision that new, more powerful deep learning methods for DILI prediction will be proposed in the near future, both in the domains of imaging and graph convolutional neural networks. Predictive models with high predictive performance may become not only screening tools, but potentially “virtual assays” (Mayr et al., 2018) able to replace in vitro and in vivo tests.

All authors conceived and designed the research project. AV selected the scientific studies reviewed in this article. GK and YS contributed to this selection. AV reviewed the scientific studies and categorized their contributions. AV and GK wrote the article. All the authors critically reviewed the article and approved it.

This work was supported by UCB Biopharma SRL through the D3net project.

YS, JS, and RC work for UCB Biopharma SRL.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Ingrid Abfalter for editorial support. We thank the projects AI-MOTION (LIT-2018-6-YOU-212), AI-SNN (LIT-2018-6-YOU-214), DeepFlood (LIT-2019-8-YOU-213), Medical Cognitive Computing Center (MC3), PRIMAL (FFG-873979), S3AI (FFG-872172), DL for granular flow (FFG-871302), ELISE (H2020-ICT-2019-3 ID: 951847), AIDD (MSCA-ITN-2020 ID: 956832). We thank the Audi. JKU Deep Learning Center, TGW LOGISTICS GROUP GMBH, Silicon Austria Labs (SAL), FILL Gesellschaft mbH, Anyline GmbH, Google, ZF Friedrichshafen AG, Robert Bosch GmbH, Software Competence Center Hagenberg GmbH, TÜV Austria, and the NVIDIA Corporation.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frai.2021.638410/full#supplementary-material.

1Greene et al. (2010) considered a fourth category for animal hepatotoxicity not tested in humans, but we omit it here.

2https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [accessed on January 18, 2021].

3https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/questions-and-answers-fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers [accessed on January 18, 2021].

4https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed [accessed on January 18, 2021].

5https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/index.cfm [accessed on January 18, 2021].

6https://chemaxon.com/products/marvin [accessed on January 18, 2021].

7http://camda2018.bioinf.jku.at/doku.php/contest_dataset\#cmap_drug_safety_challenge [accessed on January 18, 2021].

8https://www.cyprotex.com/toxicology/3d-microtissue-models/3d-imaging-of-microtissues [accessed on January 18, 2021].

9https://deeplearning4j.org [accessed on January 18, 2021].

10https://go.drugbank.com/about [accessed on January 18, 2021].

Ai, H., Chen, W., Zhang, L., Huang, L., Yin, Z., Hu, H., et al. (2018). Predicting drug-induced liver injury using ensemble learning methods and molecular fingerprints. Toxicol. Sci. 165, 100–107. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfy121

Aleo, M. D., Shah, F., Allen, S., Barton, H. A., Costales, C., Lazzaro, S., et al. (2020). Moving beyond binary predictions of human drug-induced liver injury (DILI) toward contrasting relative risk potential. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33, 223–238. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00262

Benet, L. Z., Broccatelli, F., and Oprea, T. I. (2011). BDDCS applied to over 900 drugs. AAPS J. 13, 519–547. doi:10.1208/s12248-011-9290-9

Björnsson, E. S., and Hoofnagle, J. H. (2016). Categorization of drugs implicated in causing liver injury: critical assessment based on published case reports. Hepatology 63, 590–603. doi:10.1002/hep.28323

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., and Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Machine Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022.

Brando, A., Rodríguez-Serrano, J. A., Vitrià, J., and Rubio, A. (2019). “Modeling heterogeneous distributions with an uncountable mixture of Asymmetric laplacians” in Advances in neural information processing systems 32.

Chalasani, N., Bonkovsky, H., Fontana, R., Lee, W., Stolz, A., Talwalkar, J., et al. (2015). Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN prospective study. Gastroenterology 148, 1340–1352.e7. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.006

Chen, M., Vijay, V., Shi, Q., Liu, Z., Fang, H., and Tong, W. (2011). FDA-approved drug labeling for the study of drug-induced liver injury. Drug Discov. Today 16, 697–703. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2011.05.007

Chen, M., Borlak, J., and Tong, W. (2013a). High lipophilicity and high daily dose of oral medications are associated with significant risk for drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 58, 388–396. doi:10.1002/hep.26208

Chen, M., Hong, H., Fang, H., Kelly, R., Zhou, G., Borlak, J., et al. (2013b). Quantitative structure-activity relationship models for predicting drug-induced liver injury based on FDA-approved drug labeling annotation and using a large collection of drugs. Toxicol. Sci. 136, 242–249. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kft189

Chen, M., Bisgin, H., Tong, L., Hong, H., Fang, H., Borlak, J., et al. (2014). Toward predictive models for drug-induced liver injury in humans: Are we there yet?. Biomark. Med. 8, 201–213. doi:10.2217/bmm.13.146

Chen, M., Suzuki, A., Thakkar, S., Yu, K., Hu, C., and Tong, W. (2016). DILIrank: The largest reference drug list ranked by the risk for developing drug-induced liver injury in humans. Drug Discov. Today 21, 648–653. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2016.02.015

Chierici, M., Francescatto, M., Bussola, N., Jurman, G., and Furlanello, C. (2020). Predictability of drug-induced liver injury by machine learning. Biol. Direct 15, 3. doi:10.1186/s13062-020-0259-4

Clevert, D.-A., Heusel, M., Mitterecker, A., Talloen, W., Göhlmann, H. W. H., Wegner, J. K., et al. (2012). Exploiting the Japanese Toxicogenomics Project for predictive modeling of drug toxicity. CAMDA 26–29.

Cortes, C., and Vapnik, V. (1995). Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297. doi:10.1007/bf00994018

Cruz-Monteagudo, M., Cordeiro, M. N., and Borges, F. (2008). Computational chemistry approach for the early detection of drug-induced idiosyncratic liver toxicity. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 533–549. doi:10.1002/jcc.20812

Danan, G., and Teschke, R. (2019). Roussel Uclaf causality assessment method for drug-induced liver injury: present and future. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 853. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.00853

Delalleau, O., and Bengio, Y. (2011). “Shallow vs. deep sum-product networks” in Advances in neural information processing systems, 24, 9.

Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J., Li, K., and Fei-Fei, L. (2009). ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. Proc. CVPR. 8, doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848

Duvenaud, D. K., Maclaurin, D., Iparraguirre, J., Bombarell, R., Hirzel, T., Aspuru-Guzik, A., et al. (2015). “Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints,” in Advances in neural information processing systems 28. Editors C. Cortes, N. D. Lawrence, D. D. Lee, M. Sugiyama, and R. Garnett (Red hook, NY; Curran Associates, Inc.), 2224–(2232.)

Ekins, S., Williams, A. J., and Xu, J. J. (2010). A predictive ligand-based bayesian model for human drug-induced liver injury. Drug Metab. Dispos 38, 2302–2308. doi:10.1124/dmd.110.035113

Esteva, A., Kuprel, B., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J., Swetter, S. M., Blau, H. M., et al. (2017). Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

Feng, C., Chen, H., Yuan, X., Sun, M., Chu, K., Liu, H., et al. (2019). Gene expression data based deep learning model for accurate prediction of drug-induced liver injury in advance. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 3240–3250. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00143

Fontana, R. J., Watkins, P. B., Bonkovsky, H. L., Chalasani, N., Davern, T., Serrano, J., et al. (2009). Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) prospective study: rationale, design and conduct. Drug Saf. 32, 55–68. doi:10.2165/00002018-200932010-00005

Garside, H., Marcoe, K. F., Chesnut-Speelman, J., Foster, A. J., Muthas, D., Gerry Kenna, J., et al. (2014). Evaluation of the use of imaging parameters for the detection of compound-induced hepatotoxicity in 384-well cultures of HepG2 cells and cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol. in Vitro 28, 171–181. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2013.10.015

Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O., and Dahl, G. E. (2017). “Neural message passing for quantum chemistry,” in Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 2017.

Greene, N., Fisk, L., Naven, R. T., Note, R. R., Patel, M. L., and Pelletier, D. J. (2010). Developing structure-activity relationships for the prediction of hepatotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23, 1215–1222. doi:10.1021/tx1000865

He, S., Ye, T., Wang, R., Zhang, C., Zhang, X., Sun, G., et al. (2019). An in silico model for predicting drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1897. doi:10.3390/ijms20081897

Ho, T. K. (1995). “Random decision forests,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Aug 14–16, 1995, 278–282.

Hochreiter, S., and Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735

Holte, R. C. (1993). Very simple classification rules perform well on most commonly used datasets. Machine Learn. 11, 63–90. doi:10.1023/a:1022631118932

Hong, H., Xie, Q., Ge, W., Qian, F., Fang, H., Shi, L., et al. (2008). Mold2, molecular descriptors from 2D structures for chemoinformatics and toxicoinformatics. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48, 1337–1344. doi:10.1021/ci800038f

Hong, H., Thakkar, S., Chen, M., and Tong, W. (2017). Development of decision forest models for prediction of drug-induced liver injury in humans using a large set of FDA-approved drugs. Sci. Rep. 7, 17311. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17701-7

Hoofnagle, J. H., and Björnsson, E. S. (2019). Drug-induced liver injury - Types and phenotypes. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 264–273. doi:10.1056/nejmra1816149

Hoofnagle, J. H., Serrano, J., Knoben, J. E., and Navarro, V. J. (2013). LiverTox: A website on drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 57, 873–874. doi:10.1002/hep.26175

Huang, J., Shi, W., Zhang, J., Chou, J. W., Paules, R. S., Gerrish, K., et al. (2010). Genomic indicators in the blood predict drug-induced liver injury. Pharmacogenomics J. 10, 267–277. doi:10.1038/tpj.2010.33

Huh, D., Hamilton, G. A., and Ingber, D. E. (2011). From 3D cell culture to organs-on-chips. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 745–754. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.005

Kessler, D. A. (1993). Introducing MEDWatch. A new approach to reporting medication and device adverse effects and product problems. JAMA 269, 2765–2768. doi:10.1001/jama.269.21.2765

Khadka, K. K., Chen, M., Liu, Z., Tong, W., and Wang, D. (2020). Integrating adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) and high throughput in vitro assays for better risk evaluations, a study with drug-induced liver injury (DILI). ALTEX 37, 187–196. doi:10.14573/altex.1908151

Klambauer, G., Verbist, B., Vervoort, L., Talloen, W., QSTAR Consortium, , Shkedy, Z., et al. (2015). Using transcriptomics to guide lead optimization in drug discovery projects: lessons learned from the QSTAR project. Drug Discov. Today 20, 505–513. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.12.014

Kohonen, P., Parkkinen, J. A., Willighagen, E. L., Ceder, R., Wennerberg, K., Kaski, S., et al. (2017). A transcriptomics data-driven gene space accurately predicts liver cytopathology and drug-induced liver injury. Nat. Commun. 8, 15932. doi:10.1038/ncomms15932

Kotsampasakou, E., Montanari, F., and Ecker, G. F. (2017). Predicting drug-induced liver injury: The importance of data curation. Toxicology 389, 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2017.06.003

Lamb, J., Crawford, E. D., Peck, D., Modell, J. W., Blat, I. C., Wrobel, M. J., et al. (2006). The connectivity map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 313, 1929–1935. doi:10.1126/science.1132939

Golub, E. M., Hiatt, J. R., and Zarrinpar, A. (2015). Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: An updated review. Arch. Toxicol. 89, 193–199. doi:10.1007/s00204-014-1432-2

Li, X., Yan, X., Gu, Q., Zhou, H., Wu, D., and Xu, J. (2019). DeepChemStable: Chemical stability prediction with an attention-based graph convolution network. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 1044–1049. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00672

Li, T., Tong, W., Roberts, R., Liu, Z., and Thakkar, S. (2020a). Deep learning on high-throughput transcriptomics to predict drug-induced liver injury. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 562677. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.562677

Li, T., Tong, W., Roberts, R., Liu, Z., and Thakkar, S. (2020b). DeepDILI: Deep learning-powered drug-induced liver injury prediction using model-level representation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 34, 550–565. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00374

Li, A. P. (2002). A review of the common properties of drugs with idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity and the “multiple determinant hypothesis” for the manifestation of idiosyncratic drug toxicity. Chem. Biol. Interact 142, 7–23. doi:10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00051-0

Liew, C. Y., Lim, Y. C., and Yap, C. W. (2011). Mixed learning algorithms and features ensemble in hepatotoxicity prediction. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 25, 855–871. doi:10.1007/s10822-011-9468-3

Lindquist, M. (2008). Vigibase, the WHO global ICSR database system: basic facts. Drug Inf. J 42, 409–419. doi:10.1177/009286150804200501

Liu, Z., Shi, Q., Ding, D., Kelly, R., Fang, H., and Tong, W. (2011). Translating clinical findings into knowledge in drug safety evaluation--drug induced liver injury prediction system (DILIps). PLos Comput. Biol. 7, e1002310. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002310

Lusci, A., Pollastri, G., and Baldi, P. (2013). Deep architectures and deep learning in chemoinformatics: The prediction of aqueous solubility for drug-like molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 1563–75. doi:10.1021/ci400187y

Maas, A. L., Le, Q. V., O’Neil, T. M., Vinyals, O., Nguyen, P., and Ng, A. Y. (2012). Recurrent neural networks for noise reduction in robust ASR. Proc. INTERSPEECH. 4, 22–25.

Martin, Y. C., Kofron, J. L., and Traphagen, L. M. (2002). Do structurally similar molecules have similar biological activity?. J. Med. Chem. 45, 4350–4358. doi:10.1021/jm020155c

Mauri, A., Consonni, V., Pavan, M., and Todeschini, R. (2006). DRAGON software: an easy approach to molecular descriptor calculations. Commun. Math. Computer Chem. 56, 237–(248.)

Mayr, A., Klambauer, G., Unterthiner, T., Steijaert, M., Wegner, J. K., Ceulemans, H., et al. (2018). Large-scale comparison of machine learning methods for drug target prediction on ChEMBL. Chem. Sci. 9, 5441–5451. doi:10.1039/c8sc00148k

Messner, S., Agarkova, I., Moritz, W., and Kelm, J. M. (2013). Multi-cell type human liver microtissues for hepatotoxicity testing. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 209–213. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0968-2

Minerali, E., Foil, D. H., Zorn, K. M., Lane, T. R., and Ekins, S. (2020). Comparing machine learning algorithms for predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Mol. Pharmaceutics 17, 2628-2637. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00326

Morgan, H. L. (1965). The generation of a unique machine description for chemical structures-a technique developed at chemical abstracts service. J. Chem. Doc. 5, 107–113. doi:10.1021/c160017a018

Murphy, K. P. (2012). Machine learning: A Probabilistic Perspective. Adaptive computation and machine learning Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

O’Brien, P. J., Irwin, W., Diaz, D., Howard-Cofield, E., Krejsa, C. M., Slaughter, M. R., et al. (2006). High concordance of drug-induced human hepatotoxicity with in vitro cytotoxicity measured in a novel cell-based model using high content screening. Arch. Toxicol. 80, 580–604. doi:10.1007/s00204-006-0091-3

Proctor, W. R., Foster, A. J., Vogt, J., Summers, C., Middleton, B., Pilling, M. A., et al. (2017). Utility of spherical human liver microtissues for prediction of clinical drug-induced liver injury. Arch. Toxicol. 91, 2849–2863. doi:10.1007/s00204-017-2002-1

Pryzybylak, K. R., and Cronin, M. T. (2012). in silico models for drug-induced liver injury--current status. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 8, 201–217. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.648613

Puri, M. (2020). Automated machine learning diagnostic support system as a computational biomarker for detecting drug-induced liver injury patterns in whole slide liver pathology images. Assay Drug Dev. Tech. 18, 1–10. doi:10.1089/adt.2019.919

Quist, C. (2006). Circular fingerprints: Flexible molecular descriptors with applications from physical chemistry to ADME. IDrugs 9, 199–(204.)

Rogers, D., and Hahn, M. (2010). Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 742–754. doi:10.1021/ci100050t

Rücker, C., Rücker, G., and Meringer, M. (2007). Y-randomization and its variants in QSPR/QSAR. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 47, 2345–2357. doi:10.1021/ci700157b

Sakatis, M. Z., Reese, M. J., Harrell, A. W., Taylor, M. A., Baines, I. A., Chen, L., et al. (2012). Preclinical strategy to reduce clinical hepatotoxicity using in vitro bioactivation data for >200 compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 2067–2082. doi:10.1021/tx300075j

Senior, J. R. (2007). Drug hepatotoxicity from a regulatory perspective. Clin. Liver Dis. 11, 507–524. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2007.06.002

Shoemaker, R. H. (2006). The NCI60 human tumor cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 813–823. doi:10.1038/nrc1951

Siramshetty, V. B., Nickel, J., Omieczynski, C., Gohlke, B. O., Drwal, M. N., and Preissner, R. (2016). WITHDRAWN--a resource for withdrawn and discontinued drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1080–D1086. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv1192

Stephens, C., and Andrade, R. J. (2020). Genetic predisposition to drug-induced liver injury. Clin. Liver Dis. 24, 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2019.08.003

Subramanian, A., Narayan, R., Corsello, S. M., Peck, D. D., Natoli, T. E., Lu, X., et al. (2017). A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell 171, 1437–1452. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.049

Suzuki, A., Andrade, R. J., Bjornsson, E., Lucena, M. I., Lee, W. M., Yuen, N. A., et al. (2010). Drugs associated with hepatotoxicity and their reporting frequency of liver adverse events in VigiBase: unified list based on international collaborative work. Drug Saf. 20. doi:10.2165/11535340-000000000-00000

Thakkar, S., Li, T., Liu, Z., Wu, L., Roberts, R., and Tong, W. (2020). Drug-induced liver injury severity and toxicity (DILIst): binary classification of 1279 drugs by human hepatotoxicity. Drug Discov. Today 25, 201–208. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2019.09.022

Tong, W., Hong, H., Fang, H., Xie, Q., and Perkins, R. (2003). Decision forest: Combining the predictions of multiple independent decision tree models. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 43, 525–531. doi:10.1021/ci020058s

Uehara, T., Ono, A., Maruyama, T., Kato, I., Yamada, H., Ohno, Y., et al. (2010). The Japanese toxicogenomics project: Application of toxicogenomics. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54, 218–227. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200900169

Urushidani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., et al. (2017). “Attention is all you need,” in Advances in neural information processing systems 30. Editors I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathanet al. (Red hook, NY; Curran Associates, Inc.), 5998–(6008.)

Vorrink, S. U., Zhou, Y., Ingelman-Sundberg, M., and Lauschke, V. M. (2018). Prediction of drug-induced hepatotoxicity using long-term stable primary hepatic 3D spheroid cultures in chemically defined conditions. Toxicol. Sci. 163, 655–665. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfy058

Wang, K., Zhang, S., Marzolf, B., Troisch, P., Brightman, A., Hu, Z., et al. (2009). Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4402–4407. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813371106

Wang, Y., Xiao, Q., Chen, P., and Wang, B. (2019). In silico prediction of drug-induced liver injury based on ensemble classifier method. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20. doi:10.3390/ijms20174106

Weininger, D. (1988). SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 28, 31–36. doi:10.1021/ci00057a005

Williams, D. P., Lazic, S. E., Foster, A. J., Semenova, E., and Morgan, P. (2020). Predicting drug-induced liver injury with Bayesian machine learning. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33, 239–248. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00264

Wittwehr, C., Aladjov, H., Ankley, G., Byrne, H. J., de Knecht, J., Heinzle, E., et al. (2017). How adverse outcome pathways can aid the development and use of computational prediction models for regulatory toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 155, 326–336. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfw207

Xu, J. J., Henstock, P. V., Dunn, M. C., Smith, A. R., Chabot, J. R., and de Graaf, D. (2008). Cellular imaging predictions of clinical drug-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 105, 97–105. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn109

Xu, Y., Dai, Z., Chen, F., Gao, S., Pei, J., and Lai, L. (2015). Deep learning for drug-induced liver injury. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 55, 2085–2093. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00238

Yap, C. W. (2011). PaDEL-descriptor: An open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1466–1474. doi:10.1002/jcc.21707

Zhang, C., Cheng, F., Li, W., Liu, G., Lee, P. W., and Tang, Y. (2016). in silico prediction of drug induced liver toxicity using substructure pattern recognition method. Mol. Inform. 35, 136–144. doi:10.1002/minf.201500055

Zhu, X., and Kruhlak, N. L. (2014). Construction and analysis of a human hepatotoxicity database suitable for QSAR modeling using post-market safety data. Toxicology 321, 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2014.03.009

Keywords: artificial intelligence, machine learning, neural networks, deep learning, drug-induced liver injury

Citation: Vall A, Sabnis Y, Shi J, Class R, Hochreiter S and Klambauer G (2021) The Promise of AI for DILI Prediction. Front. Artif. Intell. 4:638410. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.638410

Received: 06 December 2020; Accepted: 02 February 2021;

Published: 14 April 2021.

Edited by:

Weida Tong, National Center for Toxicological Research (FDA), United StatesReviewed by:

Zhichao Liu, National Center for Toxicological Research (FDA), United StatesCopyright © 2021 Vall, Sabnis, Shi, Class, Hochreiter and Klambauer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreu Vall, dmFsbEBtbC5qa3UuYXQ=; Günter Klambauer, a2xhbWJhdWVyQG1sLmprdS5hdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.