- 1Marine Aquaculture, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), Bremerhaven, Germany

- 2Applied Marine Biology, University of Applied Sciences Bremerhaven, Bremerhaven, Germany

- 3Blue Technology Group, Cawthron Institute, Nelson, New Zealand

- 4Aquaculture Services, Innovasea, Bedford, NS, Canada

Editorial on the Research Topic

Differentiating and defining “exposed” and “offshore” aquaculture and implications for aquaculture operation, management, costs, and policy

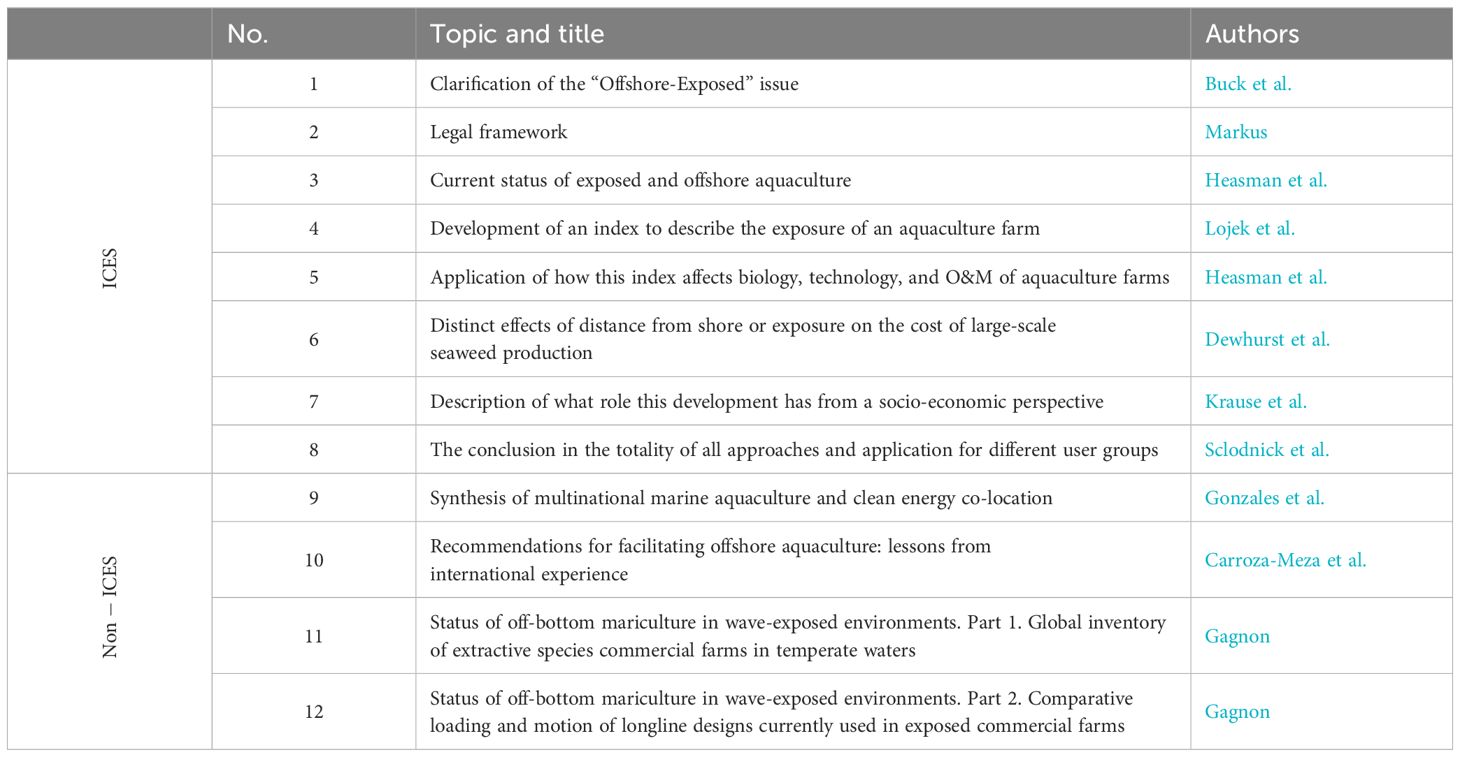

The following work is the result of contributions from 44 experts from 10 countries, led by the Working Group for Open Ocean Aquaculture (WGOOA) under the umbrella of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), Copenhagen, Denmark. This Research Topic covers the following topics in this sequence:

(1) Introduction to the conceptual problem and definition of the term “offshore”; (2) account of the “offshore” definition in national and international laws including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Rozwadowski, 2004) and the Oslo and Paris Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) (OSPAR Convention, 1992); (3) presentation of current aquaculture operations that are offshore and/or exposed; (4) development of indices as assessment tools to describe the exposure of an aquaculture farm; (5) application of these indices in aquaculture with a view to site, species, and technology selection, operation, and maintenance (O&M); (6) considerations regarding the costs of expanding aquaculture from protected to more exposed sites; (7) influence of these definitions under socio-economic aspects; and (8) a conclusion with an outlook of necessary research areas to enable expansion of aquaculture activities into “offshore” and “exposed” water bodies.

Four additional publications from non-ICES member scientists are included here as these scientific contributions fit thematically into this Research Topic and expand on important topics. Gonzales et al. explore the opportunities for co-location of aquaculture and clean energy operations. Carroza-Meza et al. make recommendations on the management and regulation of offshore aquaculture to encourage industry growth. Gagnon and Gagnon review the status of off-bottom mariculture of extractive species in exposed environments.

1 Description of the Research Topic and introduction to the compilation of publications

Farmers, engineers, scientists of various disciplines, as well as insurers, lawyers, NGO workers, and others involved in marine aquaculture often use the term “offshore” when the farm is located in a region where the height of waves and the velocity of currents become a challenge for the technology used, the cultured organism, and O&M. However, what exactly does “offshore” mean as opposed to “open ocean” and how do these terms differ from “exposed”? Other site descriptions such as “nearshore” or “inshore” are also used, as well as “coastal” or “Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)” aquaculture and “farming the deep blue”. All of these terms have only a vague description and do not seem to be clearly defined or perhaps even well understood.

In general understanding, the term “offshore” refers to activities or objects that are located far from the coastline, i.e., something typically located in the open ocean or under harsh oceanic conditions. However, how does the specific meaning of “offshore” differentiate itself from the term “open ocean”, which is generally understood as a body of water that can, but not necessarily has to be, very far from the coastline and likely requires a certain depth of water and is subject to strong currents and high waves. It becomes even more complicated if this type of site description were also understood to include the construction of aquaculture facilities or structures in the open sea, which are located beyond the continental shelf. This is exactly where the term “EEZ aquaculture” has been used. For if the site is only far enough from the coast and is already outside the territorial sea, i.e., in a zone that is 3 or up to 12 nautical miles from the coast, depending on the country, one could speak of the EEZ. So, these three terms alone vary greatly in the context in which they are used and could be explained collectively as “farming the deep blue”. However, this term of “farming the deep blue” has also been established for the required increase in production that could be operated in the open sea, i.e., not necessarily far away and not at all needing to be exposed to the inclement environmental conditions, which we considered in the explanation of the “open ocean aquaculture term”. Further, because aquaculture facilities that are close to the coast, traditionally described as “nearshore”, can be subjected to strong currents and high waves as well, it can be confused with the above as an “open ocean parameter”, and then further confused as it can also be characterized as “exposed”. Therefore, “exposed” conditions can exist just in front of the mainland or an island, within inlets, and thus, be anything but “offshore” or in the “open ocean”. Whether this type of aquaculture can then also be described as “inshore” is unclear, because “inshore” is supposedly a part of “nearshore”, but closer to the coast than the term “nearshore” actually means. So “nearshore aquaculture” could also be understood as coastal aquaculture, because the terms “inshore” and “nearshore” would be synonyms in this instance.

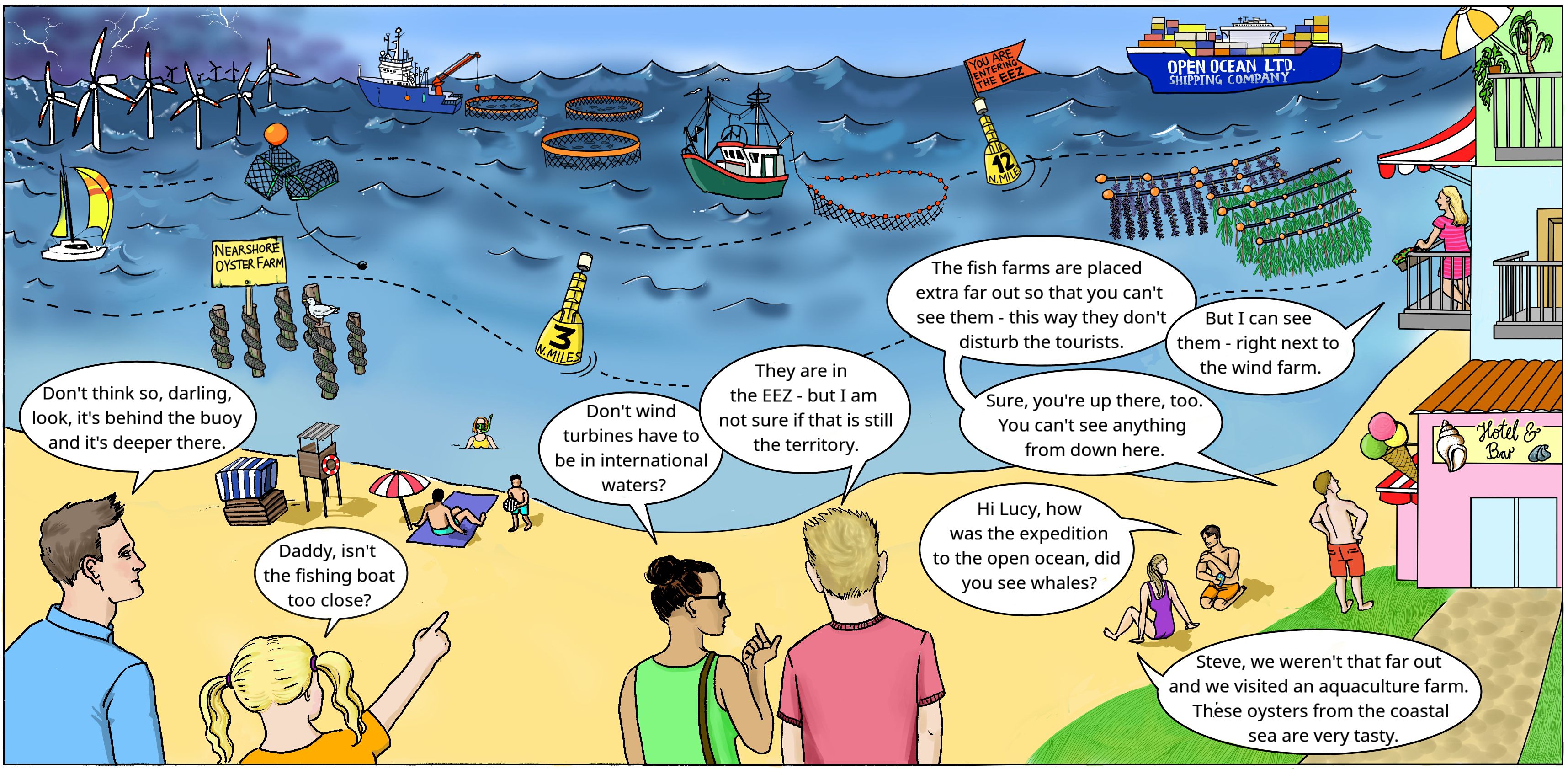

This jumble of terms, further complicated by perspective (Figure 1), all have no clear definition and are therefore used arbitrarily and must be distinguishable from each other. In particular, the terms “offshore aquaculture” and “exposed aquaculture” need a clear definition as current developments and ongoing search for locations to increase aquaculture production will have to turn to distant and environmentally challenging areas to avoid competition for space with other stakeholders close to the coast.

Figure 1. Aquaculture far away: “I understand it even when I don’t see it.” There are many different terms for describing the location of an aquaculture facility, and the distinctions between them are confusing. [Image: Buck/Holzé (AWI)].

The following publications will investigate and discuss the terms “offshore” and “exposed” with the associated changes in the aquaculture sector and society (see also Table 1). While Buck et al. identify the difficulties in understanding and applying different terms in characterizing a location of an aquaculture farm, Markus addresses the term “offshore” and its use and meaning in the context of the Law of the Sea. Heasman et al. provide an updated review on exposed and offshore aquaculture worldwide. The exposure index presented in Lojek et al. lay out a methodology for classifying sites based on different wave and current parameters (significant wave height, extreme current speed, etc.). Sites can then be characterized using an exposure index. Industry participants will have a much better understanding of what that site is like, how it differs to other sites they are familiar with, and what challenges they encounter. Heasman et al. describe the challenges of operating a farm that is spatially far from shore, applying two of the indicative indices to known aquaculture sites. Dewhurst et al. use the example of macroalgae aquaculture to determine additional costs when aquaculture is carried out in exposed or distant marine areas. Krause et al. analyze the challenges of offshore aquaculture to society, while Sclodnick et al. provide a concluding evaluation followed by an outlook.

Author contributions

BB: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This compilation was supported by the OLAMUR (Offshore Low-trophic Aquaculture in Multi-Use Scenario Realisation) project (OLAMUR, 2023) with 25 partners from eight nations dealing with the issues of technical implementation for LTA-species in the wind farms, as well as site selection, species performance, environmental monitoring and much more. The OLAMUR project is funded by the European Union under grant number 101094065. In addition, participants from New Zealand and abroad were supported through MBIE CAWX2102, Nga Punga o te Moana program, New Zealand.

Acknowledgments

Eight publications within this Research Topic were prepared within the scope of the Working Group on Open Ocean Aquaculture (WGOOA) of the intergovernmental science organization, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), Copenhagen, Denmark. Likewise, this compilation was supported by the OLAMUR (Offshore Low-trophic Aquaculture in Multi-Use Scenario Realisation) project (OLAMUR, 2023), which is funded by the European Union under grant number 101094065. In addition, participants from New Zealand and abroad were supported through MBIE CAWX2102, Nga Punga o te Moana program, New Zealand.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

OLAMUR (2023). Offshore Low-trophic Aquaculture in Multi-Use Scenario Realisation (Brussels: Funded by the European Union under grant number 101094065). doi: 10.3030/101094065

OSPAR Convention (1992). Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (Paris: Convention Text by the OSPAR Commission), 33 p.

Keywords: offshore aquaculture, exposed aquaculture, definition, seaweed aquaculture, bivalve aquaculture, fish aquaculture

Citation: Buck BH, Heasman K and Sclodnick T (2025) Editorial: Differentiating and defining “exposed” and “offshore” aquaculture and implications for aquaculture operation, management, costs, and policy. Front. Aquac. 4:1544379. doi: 10.3389/faquc.2025.1544379

Received: 12 December 2024; Accepted: 10 January 2025;

Published: 05 February 2025.

Edited by:

David Little, University of Stirling, United KingdomReviewed by:

Trevor Cowan Telfer, University of Stirling, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Buck, Heasman and Sclodnick. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bela H. Buck, YmVsYS5oLmJ1Y2tAYXdpLmRl

Bela H. Buck

Bela H. Buck Kevin Heasman

Kevin Heasman Tyler Sclodnick

Tyler Sclodnick