- Department of Statistics and Applied Probability, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, United States

We consider a general class of mean field control problems described by stochastic delayed differential equations of McKean–Vlasov type. Two numerical algorithms are provided based on deep learning techniques, one is to directly parameterize the optimal control using neural networks, the other is based on numerically solving the McKean–Vlasov forward anticipated backward stochastic differential equation (MV-FABSDE) system. In addition, we establish the necessary and sufficient stochastic maximum principle of this class of mean field control problems with delay based on the differential calculus on function of measures, and the existence and uniqueness results are proved for the associated MV-FABSDE system under suitable conditions.

Mathematical Subject Classification (2000): 93E20, 60G99, 68-04

1. Introduction

Stochastic games were introduced to study the optimal behaviors of agents interacting with each other. They are used to study the topic of systemic risk in the context of finance. For example, in Carmona et al. [1], the authors proposed a linear quadratic inter-bank borrowing and lending model, and solved explicitly for the Nash equilibrium with a finite number of players. Later, this model was extended in Carmona et al. [2] by considering delay in the control in the state dynamic to account for the debt repayment. The authors analyzed the problem via a probabilistic approach which relies on stochastic maximum principle, as well as via an analytic approach which is built on top of an infinite dimensional dynamic programming principle.

Both mean field control and mean field games are used to characterize the asymptotic behavior of a stochastic game as the number of players grows to infinity under the assumption that all the agents behave similarly, but with different notion of equilibrium. The mean field games consist of solving a standard control problem, where the flow of measures is fixed, and solving a fixed point problem such that this flow of measures matches the distribution of the dynamic of a representative agent. Whereas, the mean field control problem is a non-standard control problem in the sense that the law of state is present in the McKean–Vlasov dynamic, and optimization is performed while imposing the constraint of distribution of the state. More details can be found in Carmona and Delarue [3] and Bensoussan et al. [4].

In this paper, we considered a general class of mean field control problem with delay effect in the McKean–Vlasov dynamic. We derived the adjoint process associated with the McKean–Vlasov stochastic delayed differential equation, which is an anticipated backward stochastic differential equation of McKean–Vlasov type due to the fact that the conditional expectation of the future of adjoint process as well as the distribution of the state dynamic are involved. This type of anticipated backward stochastic differential equations (BSDE) was introduced in Peng and Yang [5], and for the general theory of BSDE, we refer Zhang [6]. The necessary and sufficient part of stochastic maximum principle for control problem with delay in state and control can be found in Chen and Wu [7]. Here, we also establish a necessary and sufficient stochastic maximum principle based on differential calculus on functions of measures as we consider the delay in the distribution. In the meantime, we also prove the existence and uniqueness of the system of McKean–Vlasov forward anticipated backward stochastic differential equations (MV-FABSDE) under some suitable conditions using the method of continuation, which can be found in Zhang [6], Peng and Wu [8], Bensoussan et al. [9], and Carmona et al. [2]. For a comprehensive study of FBSDE theory, we refer to Ma and Yong [10].

When there was no delay effect in the dynamic, Ma et al. [11] proved the relation between the solution to the FBSDE and quasi-linear partial differential equation (PDE) via “Four Step Scheme.” E et al. [12] and Raissi [13] explored the use of deep learning for solving these PDEs in high dimensions. However, the class of fully coupled MV-FABSDE considered in our paper has no explicit solution. Here, we present one algorithm to tackle the above problem by means of deep learning techniques. Due to the non-Markovian nature of the state dynamic, we apply the long short-term memory (LSTM) network, which is able to capture the arbitrary long-term dependencies in the data sequence. It also partially solves the vanishing gradient problem in vanilla recurrent neural networks (RNNs), as was shown in Hochreiter and Schmidhuber [14]. The idea of our algorithm is to approximate the solution to the adjoint process and the conditional expectation of the adjoint process. The optimal control is readily obtained after the MV-FABSDE being solved. We may also emphasize that the way that we present here for numerically computing conditional expectation may have a wide range of applications, and it is simple to implement. We also present another algorithm solving the mean field control problem by directly parameterizing the optimal control. Similar idea can be found in the policy gradient method in the regime of reinforcement learning [15] as well as in Han and E [16]. Numerically, the two algorithms that we propose in this paper yield the same results. Besides, our approaches are benchmarked to the case with no delay for which we have explicit solutions.

The paper is organized as follows. We start with an N-player game with delay, and let number of players goes to infinity to introduce a mean field control problem in section 2. Next, in section 3, we mathematically formulate the feedforward neural networks and LSTM networks, and we propose two algorithms to numerically solve the mean field control problem with delay using deep learning techniques. This is illustrated on a simple linear-quadratic toy model, however with delay in the control. One algorithm is based on directly parameterizing the control, and the other depends on numerically solving the MV-FABSDE system. In addition, we also provide an example of solving a linear quadratic mean field control problem with no delay both analytically, and numerically. The adjoint process associated with the delayed dynamic is derived, as well as the stochastic maximum principle is proved in section 4. Finally, the uniqueness and existence solution for this class of MV-FABSDE are proved under suitable assumptions via continuation method in section 5.

2. Formulation of the Problem

We consider an N-player game with delay in both state and control. The dynamic for player i ∈ {1, …, N} is given by a stochastic delayed differential equation (SDDE),

for T > 0, τ > 0 given constants, where , and where are N independent Brownian motions defined on the space , being the natural filtration of Brownian motions.

are progressively measurable functions with values in ℝ. We denote A a closed convex subset of ℝ, the set of actions that player i can take, and denote 𝔸 the set of admissible control processes. For each i ∈ {1, …, N}, A-valued measurable processes satisfy an integrability condition such that .

Given an initial condition , each player would like to minimize his objective functional:

for some Borel measurable functions fi:[0, T] × ℝN × ℝN × A → ℝ, and gi:ℝN → ℝ.

In order to study the mean-field limit of (Xt)t∈[0,T], we assume that the system (2.1) satisfy a symmetric property, that is to say, for each player i, the other players are indistinguishable. Therefore, drift bi and volatility σi in (2.1) take the form of

and the running cost fi and terminal cost gi are of the form

where we use the notation for the empirical distribution of X = (X1, ⋯ , XN) at time t, which is defined as

Next, we let the number of players N go to +∞ before we perform the optimization. According to symmetry property and the theory of propagation of chaos, the joint distribution of the N dimensional process converges to a product distribution, and the distribution of each single marginal process converges to the distribution of (Xt)0≤t≤T of the following McKean–Vlasov stochastic delayed differential equation (MV-SDDE). For more detail on the argument without delay, we refer to Carmona and Delarue [3] and Carmona et al. [17].

We then optimize after taking the limit. The objective for each player of (2.2) now becomes

where we denote the law of Xt.

3. Solving Mean-Field Control Problems Using Deep Learning Techniques

Due to the non-Markovian structure, the above mean-field optimal control problem (2.3 and 2.4) is difficult to solve either analytically or numerically. Here we propose two algorithms together with four approaches to tackle the above problem based on deep learning techniques. We would like to use two types of neural networks, one is called the feedforward neural network, and the other one is called Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network.

For a feedforward neural network, we first define the set of layers , for x ∈ ℝd, as

d is called input dimension, h is known as the number of hidden neurons, A ∈ ℝh×d is the weight matrix, b ∈ ℝh is the bias vector, and ρ is called the activation function. The following activation functions will be used in this paper, for some x ∈ ℝ,

Then feedforward neural network is defined as a composition of layers, so that the set of feedforward neural networks with l hidden layers we use in this paper is defined as

The LSTM network is one of RNN architectures, which are powerful for capturing long-range dependence of the data. It is proposed in Hochreiter and Schmidhuber [14], and it is designed to solve the shrinking gradient effects which basic RNN often suffers from. The LSTM network is a chain of cells. Each LSTM cell is composed of a cell state, which contains information, and three gates, which regulate the flow of information. Mathematically, the rule inside tth cell follows,

where the operator ⊙ denotes the Hadamard product. represents forget gate, input gate and output gate, respectively, h refers the number of hidden neurons. is the input vector with d features. is known as the output vector with initial value a0 = 0, and is known as the cell state with initial value c0 = 0. are the weight matrices connecting input and hidden layers, are the weight matrix connecting hidden and output layers, and b ∈ ℝh represents bias vector. The weight matrices and bias vectors are shared through all time steps, and are going to be learned during training process by back-propagation through time (BPTT), which can be implemented in Tensorflow platform. Here we define the set of LSTM network up to time t as

where Γf·, Γi·, Γo· are defined in (3.3).

In particular, we specify the model in a linear-quadratic form, which is inspired by Carmona et al. [2] and Fouque and Zhang [18]. The objective function is defined as

subject to

where σ, cf, ct > 0 are given constants, and denotes the mean of X at time t, and . In the following subsections, we solve the above problem numerically using two algorithms together with four approaches. The first two approaches are to directly approximate the control by either a LSTM network or a feedforward neural network, and minimize the objective (3.5) using stochastic gradient descent algorithm. The third and fourth approaches are to introduce the adjoint process associated with (3.6), and approximate the adjoint process and the conditional expectation of adjoint process using neural networks.

3.1. Approximating the Optimal Control Using Neural Networks

We first set Δt = T/N = τ/D for some positive integer N. The time discretization becomes

for ti − ti−1 = Δt, i ∈ {−D + 1, ⋯ , 0, ⋯ , N − 1, N}. The discretized SDDE (3.6) according to Euler-Maruyama scheme now reads

where (ΔWti)0≤i≤N−1 are independent, normal distributed sequence of random variables with mean 0 and variance 1.

First, from the definition of open loop control, and due to non-Markovian feature of (3.6), the open-loop optimal control is a function of the path of the Brownian motions up to time t, i.e., α(t, (Ws)0≤s≤t). We are able to describe this dependency by a LSTM network by parametrizing the control as a function of current time and the discretized increments of Brownian motion path, i.e.,

for some . We remark that the last dense layer is used to match the desired output dimension.

The second approach is again directly approximate the control but with a feedforward neural network. Due to the special structure of our model, where the mean of dynamic in (3.6) is constant, the mean field control problem coincides with the mean field game problem. In Fouque and Zhang [18], authors solved the associated mean field game problem using infinite dimensional PDE approach, and found that the optimal control is a function of current state and the past of control. Therefore, the feedforward neural network with l layers, which we use to approximate the optimal control, is defined as

From Monte Carlo algorithm, and trapezoidal rule, the objective function (3.5) now becomes

where M denotes the number of realizations and denotes the sample mean. After plugging in the neural network either given by (3.8) or (3.9), the optimization problem becomes to find the best set of parameters either (Φ1, Ψ1) or Ψ2 such that the objective J(Φ1, Ψ1) or J(Ψ2) is minimized with respect to those parameters.

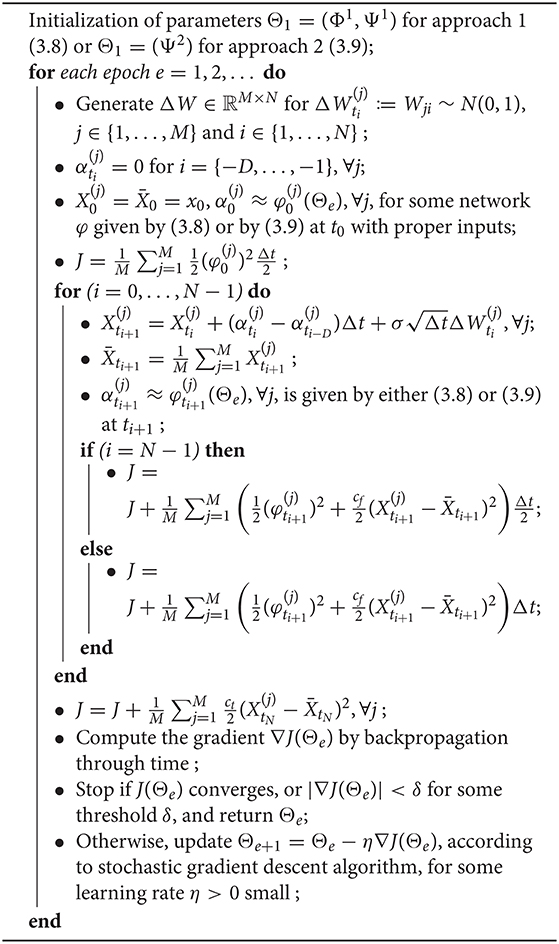

The algorithm works as follows:

Algorithm 1: Algorithms for solving mean field control problem with delay by directly approximating the optimal control using neural networks

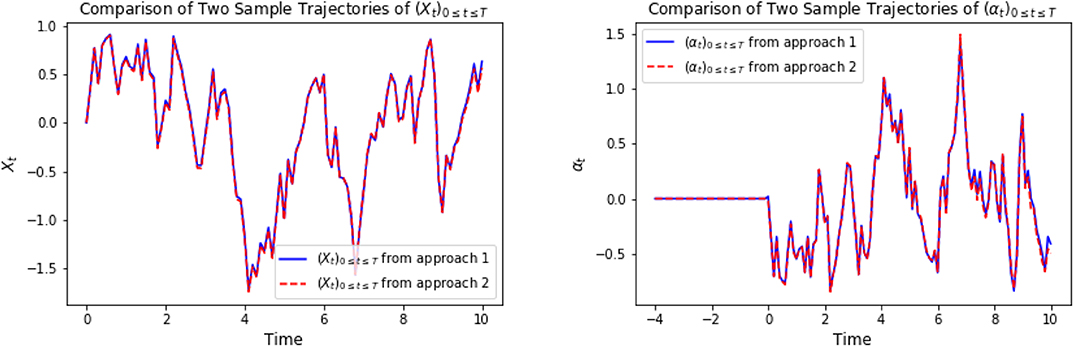

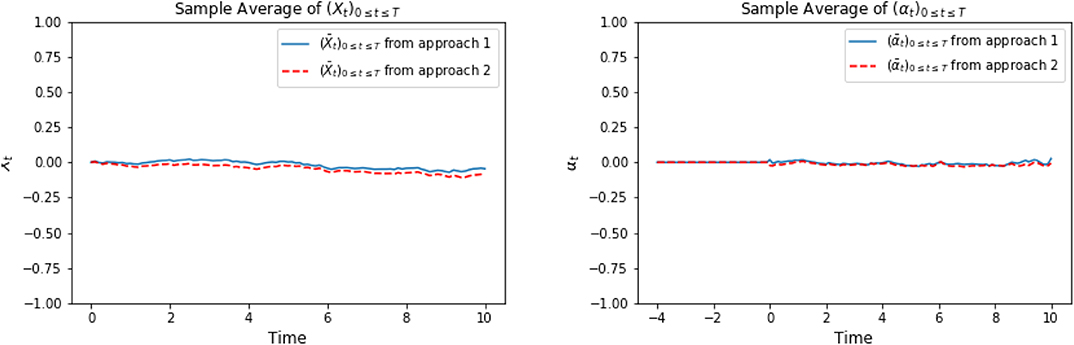

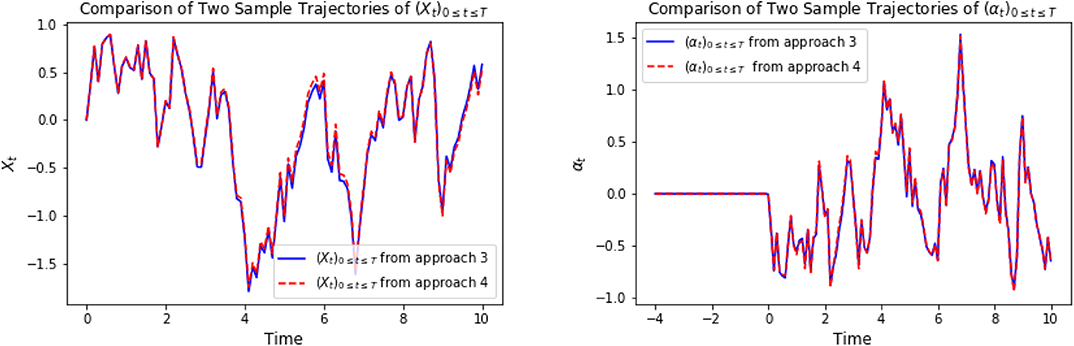

In the following graphics, we choose x0 = 0, cf = ct = 1, σ = 1, T = 10, τ = 4, Δt = 0.1, M = 4,000. For approach 1, the neural network φ ∈ ℕℕ, which is defined in (3.2), is composed of 3 hidden layers with d1 = 42, h1 = 64, h2 = 128, h3 = 64, d2 = 1. For approach 2, the LSTM network φ ∈ 𝕃𝕊𝕋𝕄, which is defined in (3.4), consists of 128 hidden neurons. For a specific representative path, the underlying Brownian motion paths are approximately the same for different approaches. Figure 1 compares one representative optimal trajectory of the state dynamic and the control, and they coincide. Figure 2 plots the sample average of optimal trajectory of the state dynamic and the control, which are trajectories of approximately 0, and this is the same as the theoretical mean.

Figure 1. On the left, we compare one representative optimal trajectory of (Xti)t0≤ti≤tN. The plot on the right show the comparison of one representative optimal trajectory of (αti)t0≤ti≤tN between approach 1 and approach 2.

Figure 2. On the left, we compare the sample mean of optimal trajectories of (Xti)t0≤ti≤tN. The plot on the right show the comparison of sample mean of trajectories of optimal control (αti)t0≤ti≤tN between approach 1 and approach 2.

3.2. Approximating the Adjoint Process Using Neural Networks

The third and fourth approaches are based on numerically solving the MV-FABSDE system using LSTM network and feedforward neural networks. From section 4, we derive the adjoint process, and prove the sufficient and necessary parts of stochastic maximum principle. From (4.7), we are able to write the backward stochastic differential equation associated to (3.6) as,

with terminal condition YT = ct(XT − mT), and Ys = 0 for s ∈ (T, T + τ]. The optimal control can be obtained in terms of the adjoint process Yt from the maximum principle, and it is given by

From the Euler-Maruyama scheme, the discretized version of (3.6) and (3.11) now reads, for i = {0, …, N − 1},

where we use the sample average to approximate the expectation of Xt. In order to solve the above MV-FABSDE system, we need to approximate .

The third approach consists of approximating using three LSTM networks as functions of current time and the discretized path of Brownian motions, respectively, i.e.,

for some . Again, the last dense layers are used to match the desired output dimension.

Since approach 3 consists of three neural networks with large number of parameters, which is hard to train in general, we would like to make the following simplification in approach 4 for approximating via combination of one LSTM network and three feedforward neural networks. Specifically,

In words, the algorithm works as follows. We first initialize the parameters (ΘY, ΘEY, ΘZ) = ((ΦY, ΨY), (ΦEY, ΨEY), (ΦZ, ΨZ)) either in (3.14) or (ΘY, ΘEY, ΘZ) = ((Φ, ΨY), ΨEY), ΨZ) in (3.15). At time 0, X0 = x0, for some network (φY, φEY, φZ) given by either (3.14) or (3.15), and α0 = −Yt0+E[YtD|]. Next, we update Xti+1 and Yti+1 according to (3.12), and the solution to the backward equation at ti+1 is denoted by Ỹti+1. In the meantime, Yti+1 is also approximated by a neural network. In such case, we refer to Ỹ· as the label, and Y· given by the neural network as the prediction. We would like to minimize the mean square error between these two. At time T, YtN is also supposed to match , from the terminal condition of (3.11). In addition, the conditional expectation given by a neural network should be the best predictor of Ỹti+D, which implies that we would like to find the set of parameters ΘEY such that is minimized for all ti ∈ {t0, …, tN−D}. Therefore, for M samples, we would like to minimize two objective functions L1 and L2 defined as

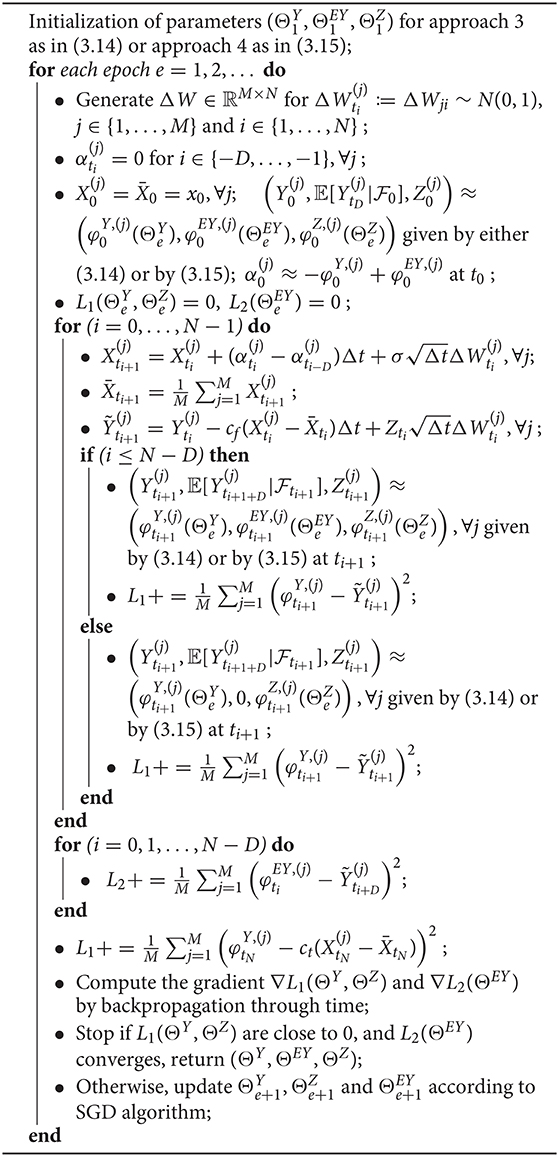

The algorithm works as follows:

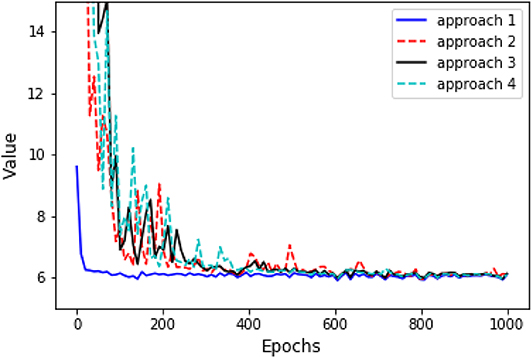

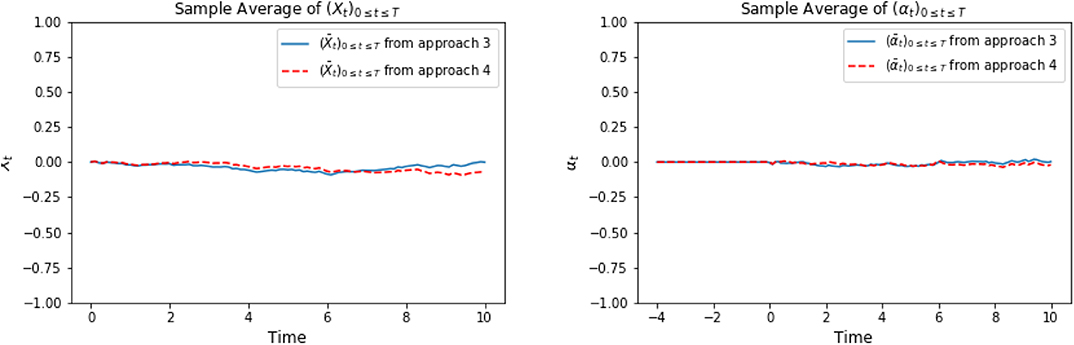

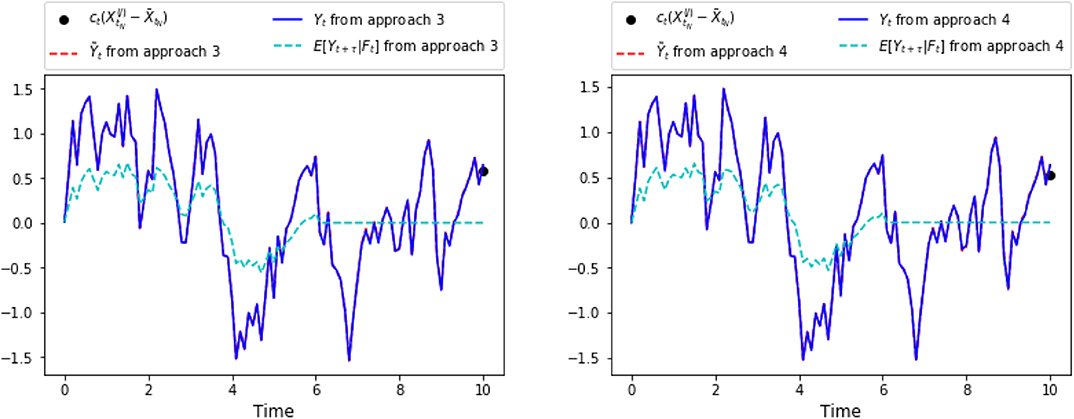

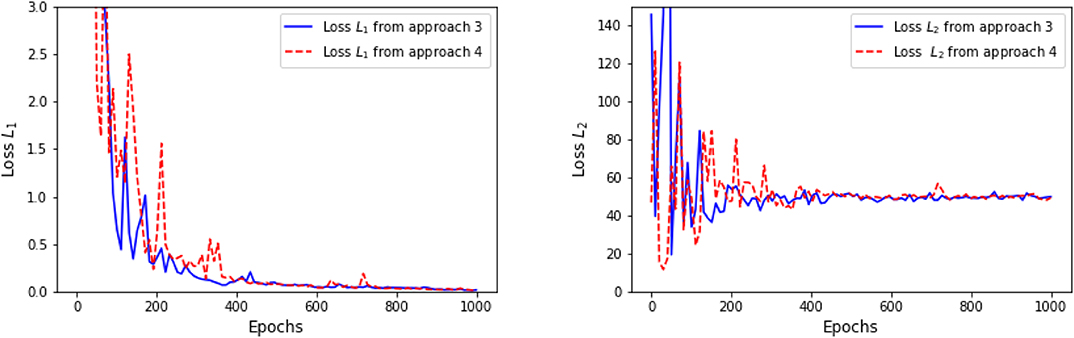

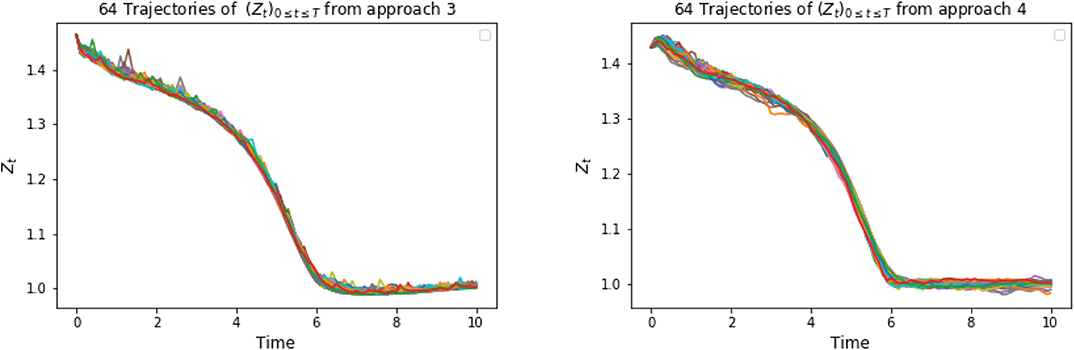

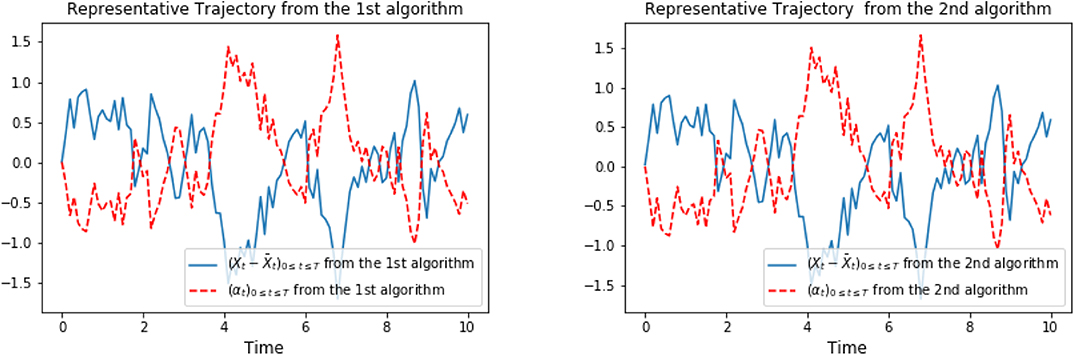

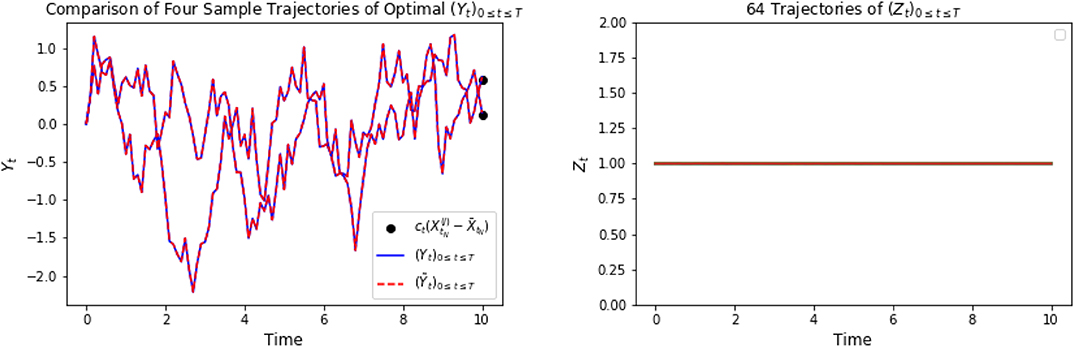

Again, in the following graphics, we choose x0 = 0, cf = ct = 1, σ = 1, T = 10, τ = 4, Δt = 0.1, M = 4, 000. In approach 3, each of the three LSTM networks approximating and Zti consists of 128 hidden neurons, respectively. In approach 4, the LSTM consists of 128 hidden neurons, and each of the feedforward neural networks has parameters d1 = 128, h1 = 64, h2 = 128, h3 = 64, d2 = 1. For a specific representative path, the underlying Brownian motion paths are the same for different approaches. Figure 3 compares one representative optimal trajectory of the state dynamic and the control via two approaches, and they coincide. Figure 4 plots the sample average of optimal trajectory of the dynamic and the control, which are trajectories of 0, which is the same as the theoretical mean. Comparing to Figures 1, 2, as well as based on numerous experiments, we find that given a path of Brownian motion, the two algorithms would yield similar optimal trajectory of state dynamic and similar path for the optimal control. From Figure 6, the loss L1 as defined in (3.16) becomes approximately 0.02 in 1,000 epochs for both approach 3 and approach 4. This can also be observed from Figure 5, since the red dash line and the blue solid line coincide for both left and right graphs. In addition, from the righthand side of Figure 6, we observe the loss L2 as defined in (3.16) converges to 50 after 400 epochs. This is due to the fact that the conditional expectation can be understood as an orthogonal projection. Figure 7 plots 64 sample paths of the process (Zti)t0≤ti≤tN, which seems to be a deterministic function since σ is constant in this example. Finally, Figure 8 shows the convergence of the value function as number of epochs increases. Both algorithms arrive approximately at the same optimal value which is around 6 after 400 epochs. This confirms that the out control problem has a unique solution. In section 5, we show that the MV-FASBDE system is uniquely solvable. It is also observable that the first algorithm converges faster than the second one, since it directly paramerizes the control using one neural network, instead of solving the MV-FABSDE system, which uses three neural networks.

Figure 3. On the left, we compare one representative optimal trajectory of (Xti)t0≤ti≤tN. The plot on the right shows the comparison of one representative optimal trajectory of (αti)t0≤ti≤tN between approach 3 and approach 4.

Figure 4. On the left, we compare the sample mean of optimal trajectories of (Xti)t0≤ti≤tN. The plot on the right shows the comparison of sample mean of trajectories of optimal control (αti)t0≤ti≤tN between approach 3 and approach 4.

Figure 5. Plots of representative trajectories of [], from approach 3 (one the left) and from approach 4 (on the right).

Figure 6. Convergence of loss L1 (on the left) and convergence of loss L2 (on the right) as defined in (3.16) from approach 3 and approach 4.

Figure 7. 64 trajectories of (Zti)t0≤ti≤tN based on approach 3 (on the left) and approach 4 (on the right).

3.3. Numerically Solving the Optimal Control Problem With No Delay

Since the algorithms we proposed embrace the case with no delay, we illustrate the comparison between numerical results and the analytical results. By letting τ > T we obtain αt−τ = 0 in (3.6), and we aim at solving the following linear-quadratic mean-field control problem by minimizing

subject to

Again, from section 4, we find the optimal control

where (Yt, Zt) is the solution of the following adjoint process,

Next, we make the ansatz

for some deterministic function ϕt, satisfying the terminal condition ϕT = ct. Differentiating the ansatz, the backward equation should satisfy

where denotes the time derivative of ϕt. Comparing with (3.19), and identifying the drift and volatility term, ϕt must satisfy the scalar Riccati equation,

and the process Zt should satisfy

which is deterministic. If we choose x0 = 0, cf = ct = 1, T = 10, ϕt = 1 solves the Riccati equation (3.22), so that Zt = 1, ∀t ∈ [0, T], and from (3.20), the optimal control satisfies

Numerically, we apply the two deep learning algorithms proposed in the previous section. The first algorithm directly approximates the control. According to the open loop formulation, we set

for some h ∈ ℤ+. We remark that the last dense layer is used to match the desired output dimension. The second algorithm numerically solves the forward backward system as in (3.18) and (3.19). From the ansatz (3.20) and the Markovian feature, we approximate (Yt, Zt)0≤t≤T using two feedforward neural networks, i.e.,

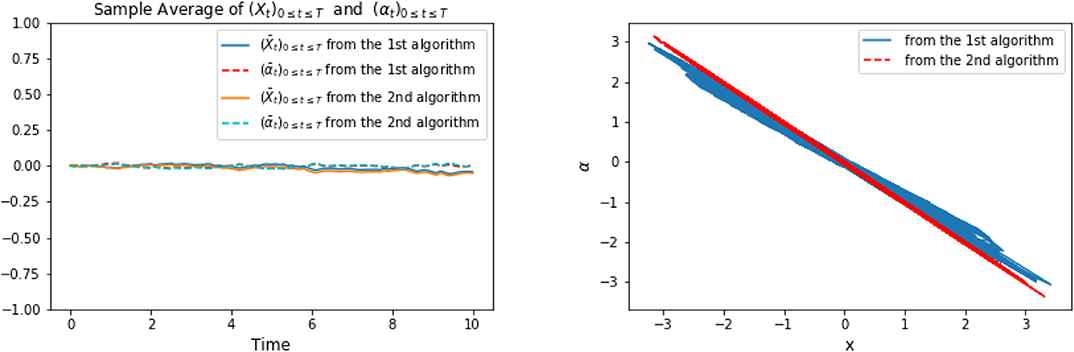

Figure 9 shows the representative optimal trajectory of and (αti)t0≤ti≤tN from both algorithms, which are exactly the same. The symmetry feature can be seen from the computation (3.24). On the left of Figure 10 confirms the mean of the processes and (αti)t0≤ti≤tN are 0 from both algorithms. The right picture of Figure 10 plots the data points of x against α, and we can observe that the optimal control α is linear in x as a result of (3.24), and the slope tends to be - 1, since ϕ = 1 solves the scalar Riccati equation (3.22). Finally, Figure 11 plots representative optimal trajectories of the solution to the adjoint equations (Yt, Zt). On the left, we observe that the adjoint process (Yt)0≤t≤T matches the terminal condition, and on the right, (Zt)0≤t≤T appears to be a deterministic process of value 1, and this matches the result we compute previously.

Figure 9. Representative optimal trajectory of and (αti)t0≤ti≤tN from algorithm 1 (on the left) and from algorithm 2 (on the right).

Figure 10. The picture on the left plots the sample averages of (Xti)t0≤ti≤tN and (αti)t0≤ti≤tN for both algorithm 1 and 2; The plot on the right shows the points of x against α for both algorithms.

Figure 11. The plot on the left shows representative trajectories of [(Yti)t0≤ti≤tN, (Ỹti)t0≤ti≤tN]. The picture on the right plots 64 trajectories of (Zti)t0≤ti≤tN.

4. Stochastic Maximum Principle for Optimality

In this section, we derive the adjoint equation associated to our mean field stochastic control problem (2.3) and (2.4). The necessary and sufficient parts of stochastic maximum principle have been proved for optimality. We assume

(H4.1) b, σ are differentiable with respect to (Xt, μt, Xt−τ, μt−τ, αt, αt−τ); f is differentiable with respect to (Xt, μt, Xt−τ, μt−τ, α); g is differentiable with respect to (XT, μT). Their derivatives are bounded.

In order to simplify our notations, let θt = (Xt, μt, αt). For 0 < ϵ < 1, we denote αϵ the admissible control defined by

for any (α)0≤t≤T and (β)0≤t≤T ∈ 𝔸. is the corresponding controlled process. We define

to be the variation process, which should follow the following dynamic for t ∈ (0, T],

with initial condition ∇Xt = Δαt = 0, t ∈ [−τ, 0). is a copy of (Xt, ∇Xt) defined on , where we apply differential calculus on functions of measure, see Carmona and Delarue [3] for detail. ∂xb, ∂xτb, ∂μb, ∂μτb, ∂αb, ∂ατb are derivatives of b with respect to (Xt, Xt−τ, μt, μt−τ, αt, αt−τ), respectively, and we use the same notation for ∂·σ.

In the meantime, the Gateaux derivative of functional α → J(α) is given by

In order to determine the adjoint backward equation of (Yt, Zt)0≤t≤T associated to (2.3), we assume it is of the following form:

Next, we apply integration by part to ∇Xt and Yt. It yields

We integrate from 0 to T, and take expectation to get

Using the fact that Yt = Zt = 0 for t ∈ (T, T + τ], we are able to make a change of time, and by Fubini's theorem, so that (4.4) becomes

Now we define the Hamiltonian H for as

Using the terminal condition of YT, and plugging (4.5) into (4.2), and setting the integrand containing ∇Xt to zero, we are able to obtain the adjoint equation is of the following form

Theorem 4.1. Let (αt)0≤t≤T ∈ A be optimal, (Xt)0≤t≤T be the associated controlled state, and (Yt, Zt)0≤t≤T be the associated adjoint processes defined in (4.7). For any β ∈ A, and t ∈ [0, T],

Proof. Given any (βt)0≤t≤T ∈ 𝔸, we perturbate αt by ϵ(βt−αt) and we define for 0 ≤ ϵ ≤ 1. Using the adjoint process (4.7), and apply integration by parts formula to (∇XtYt). Then plug the result into (4.2), and the Hamiltonian H is defined in (4.6). Also, since α is optimal, we have

Now, let be an arbitrary progressively measurable set, and denote C′ the complement of C. We choose βt to be for any given β ∈ A. Then,

which implies,

□

Remark 4.2. When we further assume that H is convex in (αt, αt−τ), then for any β, βτ ∈ A in Theorem 4.1, we have

as a direct consequence of (4.8).

Theorem 4.3. Let (αt)0≤t≤T ∈ 𝔸 be an admissible control. Let (Xt)0≤t≤T be the controlled state, and (Yt, Zt)0≤t≤T be the corresponding adjoint processes. We further assume that for each t, given Yt and Zt, the function (x, μ, xτ, μτ, α, ατ) → H(t, x, μ, xτ, μτ, α, ατ, Yt, Zt), and the function (x, μ) → g(x, μ) are convex. If

for all t, then (αt)0≤t≤T is an optimal control.

Proof. Let be a admissible control, and let be the corresponding controlled state. From the definition of the objective function as in (2.4), we first use convexity of g, and the terminal condition of the adjoint process Yt in (4.7), then use the fact that H is convex, and because of (4.12), we have the following

□

5. Existence and Uniqueness Result

Given the necessary and sufficient conditions proven in section 4, we use the optimal control defined by

to establish the solvability result of the McKean–Vlasov FABSDE (2.3) and (4.7) for t ∈ [0, T]:

with initial condition and terminal condition In addition to assumption (H 4.1), we further assume

(H5.1) The drift and volatility functions b and σ are linear in x, μ, xτ, μτ, α, ατ. For all , we assume that

for some measurable deterministic functions with values in ℝ bounded by R, and we have used the notation m = ∫xdμ(x) and mτ = ∫xdμτ(x) for the mean of measures μ and μτ, respectively.

(H5.2) The derivatives of f and g with respect to (x, xτ, μ, μτ, α) and (x, μ) are Lipschitz continuous with Lipschitz constant L.

(H5.3) The function f is strongly L-convex, which means that for any t ∈ [0, T], any , any α, α′ ∈ A, any , any random variables X and X′ having μ and μ′ as distribution, and any random variables Xτ and having μτ and as distribution, then

The function g is also assumed to be L-convex in (x, μ).

Theorem 5.1. Under assumptions (H5.1-H5.3), the McKean–Vlasov FABSDE (5.2) is uniquely solvable.

The proof is based on continuation methods. Let λ ∈ [0, 1], consider the following class of McKean–Vlasov FABSDEs, denoted by MV-FABSDE(λ), for t ∈ [0, T]:

where we denote θt = (Xt, μt, αt), with optimality condition

and with initial condition X0 = x0; Xt = αt = 0 for t ∈ [−τ, 0) and terminal condition

and Yt = 0 for t ∈ (T, T + τ], where are some square-integrable progressively measurable processes with values in ℝ, and is a square integrable -measurable random variable with value in ℝ.

Observe that when λ = 0, system (5.5) becomes decoupled standard SDE and BSDE, which has an unique solution. When setting for 0 ≤ t ≤ T, and , we are able to recover the system of (5.2).

Lemma 5.2. Given λ0 ∈ [0, 1), for any square-integrable progressively measurable processes , and , such that system FABSDE(λ0) admits a unique solution, then there exists δ0 ∈ (0, 1), which is independent on λ0, such that the system MV-FABSDE(λ) admits a unique solution for any λ ∈ [λ0, λ0 + δ0].

Proof. Assuming that are given as an input, for any λ ∈ [λ0, λ0 + δ0], where δ0 > 0 to be determined, denoting δ: = λ − λ0 ≤ δ0, we take

According to the assumption, let (X, Y, Z) be the solutions of MV-FABSDE(λ0) corresponding to inputs , i.e., for t ∈ [0, T]

with initial condition, X0 = x0, Xs = αs = 0 for s ∈ [−τ, 0), and terminal condition

and Yt = Zt = 0 for t ∈ (T, T+τ], where we have used simplified notations,

We would like to show that the map is a contraction. Consider (ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ, Δα) = (X−X′, Y−Y′, Z−Z′, α−α′), where . In addition, for the following computation, we have used simplified notation:

Applying integration by parts to ΔXtYt, we have

After integrating from 0 to T, and taking expectation on both sides, we obtain

In the meantime, from the terminal condition of YT given in (5.8), and since g is convex, we also have

Following the proof of sufficient part of maximum principle and using (5.12), and (5.13), we find

Reverse the role of α and α′, we also have

Summing (5.14) and (5.15), using the fact that b and σ have the linear form, using change of time and Lipschitz assumption, it yields

Next, we apply Ito's formula to ,

Then integrate from 0 to T, and take expectation,

From Gronwall's inequality, we can obtain

Similarly, applying Ito's formula to , and taking expectation, we have

Choose ϵ = 96 max{R2, L}, and from assumption (H5.1 - H5.2) and Gronwall's inequality, we obtain a bound for ; and then substitute the it back to the same inequality, we are able to obtain the bound for . By combining these two bounds, we deduce that

Finally, combining (5.19) and (5.21), and (5.16), we deduce

Let , it is clear that the mapping Φ is a contraction for all δ ∈ (0, δ0). It follows that there is a unique fixed point which is the solution of MV-FABSDE(λ) for λ = λ0 + δ, δ ∈ (0, δ0).□

Proof of Theorem 5.1: For λ = 0, FABSDE(0) has a unique solution. Using Lemma 5.2, there exists a δ0 > 0 such that FBSDE(δ) has a unique solution for δ ∈ [0, δ0], assuming (n − 1)δ0 < 1 ≤ nδ0. Following by a induction argument, we repeat Lemma 5.2 for n times, which gives us the existence of the unique solution of FABSDE(1).□

6. Conclusion

Overall, we presented a comprehensive study of a general class of mean-field control problems with delay effect. The state dynamics is described by a McKean–Vlasov stochastic delayed differential equation. We derive the adjoint process associated to the dynamics, which is in the form of an anticipated backward stochastic differential equation of McKean–Vlasov type. We also prove a version of stochastic maximum principle, which gives necessary and sufficient conditions for the optimal control. Furthermore, we prove the existence and uniqueness of this class of forward anticipated backward stochastic differential equations under suitable conditions.

However, due to the lack of explicit solutions, numerical methods are needed. The non-linear nature of the problem due to the McKean–Vlasov aspect combined with non-Markovianity due to delay rule out classical numerical methods. Our study show that deep learning methods can deal with these obstacles. we proposed two algorithms based on machine learning to numerically solve the control problem. One is to directly approximate the control using a neural network, while the loss is given by the objective function in the control problem. The other algorithm is based on the system of forward and backward stochastic differential equations. We approximate the adjoint processes (Y·, Z·) and the conditional expectation of the adjoint process using neural networks. In this case, there are two loss functions that we need to minimize as shown in (3.16). The first loss is associated with the adjoint process Y·, and the other one is related to . After minimizing the losses, the optimal control can be readily obtained from the adjoint processes. In addition, Figure 8 illustrates that the optimal value to the control problem, that is computed from different methods, converges. Moreover, our method also works when the control problem has no delay. As a sanity check, we provide an example of control problem without delay effect, and we show that the solution obtained from the algorithm matches the explicit solution.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work supported by NSF grant DMS-1814091.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Carmona R, Fouque JP, Sun LH. Mean field games and systemic risk. Commun Math Sci. (2015) 13:911–33. doi: 10.4310/CMS.2015.v13.n4.a4

2. Carmona R, Fouque JP, Mousavi SM, Sun LH. Systemic risk and stochastic games with delay. J Optim Appl. (2018) 179:366–99. doi: 10.1007/s10957-018-1267-8

3. Carmona R, Delarue F. Probabilistic Theory of Mean Field Games with Applications I & II. Springer International Publishing (2018).

4. Bensoussan A, Frehse J, Yam SCP. Mean Field Games and Mean Field Type Control Theory. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag (2013).

5. Peng S, Yang Z. Anticipated backward stochastic differential equations. Ann Probab. (2009) 37:877–902. doi: 10.1214/08-AOP423

7. Chen L, Wu Z. Maximum principle for the stochastic optimal control problem with delay and application. Automatica. (2010) 46:1074–80. doi: 10.1016/j.automatica.2010.03.005

8. Peng S, Wu Z. Fully coupled forward-backward stochastic differential equations and applications to optimal control. SIAM J Control Optim. (1999) 37:825–43. doi: 10.1137/S0363012996313549

9. Bensoussan A, Yam SCP, Zhang Z. Well-posedness of mean-field type forward-backward stochastic differential equations. Stochastic Process Appl. (2015) 125:3327–54. doi: 10.1016/j.spa.2015.04.006

10. Ma J, Yong J. Forward-Backward Stochastic Differential Equations and their Applications. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag (2007).

11. Ma J, Protter P, Yong J. Solving forward-backward stochastic differential equations explicitly–a four step scheme. Probab Theory Relat Fields. (1994) 98:339–59.

12. Weinan E, Han J, Jentzen A. Deep learning-based numerical methods for high-dimensional parabolic partial differential equations and backward stochastic differential equations. Commun Math Stat. (2017) 5:349–80. doi: 10.1007/s40304-017-0117-6

13. Raissi M. Forward-backward stochastic neural networks: deep learning of high-dimensional partial differential equations. (2018). arxiv[Preprint].arxiv:1804.07010.

15. Sutton RS, McAllester DA, Singh SP, Mansour Y. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS). (1999). p. 1057–63. Available online at: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/1713-policy-gradient-methods-for-reinforcement-learning-with-function-approximation

16. Han J, Weinan E. Deep Learning Approximation for Stochastic Control Problems, Deep Reinforcement Learning Workshop. Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) (2016).

17. Carmona R, Delarue F, Lachapelle A. Control of McKean-Vlasov dynamics versus mean field games. Math Fin Econ. (2013) 7:131–66. doi: 10.1007/s11579-012-0089-y

Keywords: deep learning, mean field control, delay, McKean-Vlasov, stochastic maximum principal

Citation: Fouque J-P and Zhang Z (2020) Deep Learning Methods for Mean Field Control Problems With Delay. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 6:11. doi: 10.3389/fams.2020.00011

Received: 02 November 2019; Accepted: 07 April 2020;

Published: 12 May 2020.

Edited by:

Sou Cheng Choi, Illinois Institute of Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Tomas Tichy, VSB-Technical University of Ostrava, CzechiaSamy Wu Fung, University of California, Los Angeles, United States

Copyright © 2020 Fouque and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jean-Pierre Fouque, Zm91cXVlQHBzdGF0LnVjc2IuZWR1

Jean-Pierre Fouque

Jean-Pierre Fouque Zhaoyu Zhang

Zhaoyu Zhang