94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Anim. Sci., 02 May 2024

Sec. Animal Welfare and Policy

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2024.1371006

This brief report characterizes and maps changes in six key aspects of pig animal welfare (AW) legislation in 13 countries in the European Union (EU) during the period 1991-2020, focusing primarily on aspects of AW likely to impact the economic performance and international competitiveness of the pig production sector. National AW legislation in the selected EU member states that exceed the EU minimum levels within the six selected key areas are also mapped. Analysis of changes in AW over time, using legislative texts, academic literature, and an expert survey, revealed that AW-legislation at the national level has generally become more stringent, in line with EU directives, and that a number of member states have introduced additional AW legislation that exceed EU minimum levels. This review helps to uncover historical changes in and can form the basis for further research investigating effects of changes in AW legislation.

Animal welfare (AW) concerns have been high on the agenda in the European Union (EU) for decades (e.g. Veissier et al., 2008; Sandøe and Christensen, 2024) and a series of directives to protect farm animals have been adopted. These directives intend to help to ensure a minimum level of AW across the EU, but the national AW-legislation often varies between member states. Many cross-country comparisons of AW have been made at specific points in time, but there is a lack of studies on how national AW legislation have evolved during recent decades. Understanding the dynamics of national AW-legislation is crucial to identify whether these are converging or diverging over time. AW-legislation relates to a minimum level, while the housing and management practices executed are influenced by a broad range of factors including presence of private and industry standards and policies, culture and tradition within a country or region and level of compliance with legislation (Keeling et al., 2012). Consequently, these factors also influence the welfare level of the animals, consumer and citizen trust, economic performance of farms and the sector’s international competitiveness. As legislation is the common foundation for AW levels, a comprehensive mapping of the development of AW- legislation over time is an essential base for further studies on e.g. associations between AW-legislation and economic performance of farms, international trade and AW on farm. The mapping of AW-legislation evolution is also valuable for discussions on future changes in policies and legislation at EU, national and industry level.

This study aims to characterize and map major changes in EU and national pig AW-legislation in a sample of European countries (all EU-member states during at least part of the study period) and across the considered countries during the period 1991-2020. This study is limited to mapping the evolution of AW-legislation and the timing of when these entered into force and does not include the corresponding detailed mapping of compliance of these legislations. There are concerns that stricter legislation can reduce the pig sectors sector’s international competitiveness, leading to farm closures (Harvey et al., 2013) and increase pork imports from “low AW havens” (Grethe, 2007). Given the importance of these issues, in this study we focus primarily on areas of AW that are likely to influence the economic performance and international competitiveness of the pig production sector. Thus, this study covers a broad range of key aspects of pig AW-legislation, but focuses on, and is limited to, aspects likely to substantially impact the economic performance of farms and the international competitiveness of the pig production sector.

Pig AW-legislations are a particularly interesting case in terms of their evolution over time, since conventional pig production is conducted under increasingly intense production forms across Europe. Moreover, there have been changes in pig AW-legislation in the EU over time, differences in AW-legislation between EU member states exist (e.g. Mul et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2014), and some of these differences are associated with high production costs (Grethe, 2017). This study makes a novel contribution to the existing literature by identifying differences in pig AW-legislation across different EU countries and describing the evolution of these differences over time. Earlier studies have focused on cross-country differences in pig AW-legislation at a specific point in time (often one year) (e.g., Mul et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2014) or changes in pig AW-legislation in a specific country (Lundmark Hedman et al., 2021). A few wider reviews have been published in the past, but they do not cover as many countries or as many key aspects of pig AW-legislation or provide the same level of detail related evolution over time as in the present study. For example, a recent “fitness check” on AW-legislation in the EU (European Commission, 2022) lists members states in which national AW legislative requirements exceed those in EU legislation for several key AW aspects, but does not provide details on the year in which different items of national legislation came into force.

Three critical points must be considered when studying AW legislation. First, an adequate definition of AW-legislation is needed. Second, AW-legislation must be categorized in a way that allows cross-country comparisons, as differences in e.g., the structure and aim of AW-legislation in different countries can pose challenges when comparing AW legislations across countries. Finally, the scope of the analysis must be specified. Below, we discuss each of these points in turn.

Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs was passed in 1991, making it a natural starting point for the present analysis. The 30-year span since then (1991-2020) was considered necessary to identify changes in farm AW legislations over time. The focus in the analysis was on government legislation related to pig production on-farm; legislation related to off-farm activities and private governance of AW were excluded. Moreover, legislation governing how compliance with AW-legislation are controlled were not included.

The number of EU countries included in the analysis was limited to 13, comprising Sweden and Finland (member states known for stringent AW legislation) and the 11 top pork-exporting countries in the EU (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain), and the United Kingdom, which was an EU member state with significant pig production for most of the study period.

Mapping and assessment were conducted for a number of key aspects of AW in pig production, selected based on the main focus of EU legislation and aspects of AW likely to substantially impact the economic performance of farms and the international competitiveness of the pig production sector (Harvey et al., 2013). These aspects were, in no particular order: (i) Sow housing during gestation; (ii) sow housing during lactation; (iii) housing of growing-finishing pigs; (iv) weaning age; (v) tail docking; and (vi) manipulable material.

These six key aspects are critical in an AW perspective (e.g., Veissier et al., 2008; Lundmark Hedman, 2020), and are also of potential relevance for the economic performance of farms and the international competitiveness of the pig production sector within a country. Immediate costs for the farm business related to changes in legislation arise from all six aspects. For example, changes to legislation regarding housing [aspects (i)-(iv)] may require new barns to be built; higher weaning age (v) leads to a longer nursing period leading to lower numbers of produced piglets per sow per year; and prohibiting tail docking (v) requires more space per pig, environmental enrichment, and more management, with associated costs, as does providing manipulable material (vi) and new drainage systems when straw is used. However, changes in AW-legislation may have more long-term positive effects on the economic performance of farms and the international competitiveness of the pig production sector, such as reduced use of antibiotics and maintained demand and consumer trust in production.

We collected historical information on AW-legislation for each EU country and also at overall EU level for each of the six key aspects. We derived some information directly from legislation documents at EU and national level. We also used pre-existing compilations of AW data, e.g., that by Mul et al. (2010). In some cases, we consulted experts at the Swedish Centre for Animal Welfare (SCAW) and the Centre of Excellence in Animal Welfare Science at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. We also reviewed the academic literature describing the progress of AW-legislation in different countries. In addition, we collected secondary data describing the level of compliance, where the main sources of data were the audit reports by the European Commission Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (European Commission. various years), and official communications from the EU to member states deemed to be non-compliant.

As a complement to published information on AW legislation, we performed a survey of AW experts. A questionnaire was sent to experts from government, academia, and AW organizations in each of the 13 selected EU member countries. The responses served as a quality control tool in situations where sufficient secondary data from reviewing the literature were lacking. As a second step, experts answering the survey who indicated that they were willing to answer some follow-up questions were contacted by email about these questions.

The questionnaire asked the following two questions with respect to each of the six key pig AW aspects:

1. Are there currently any major additions in your national pig AW-legislation above the EU legislation? By ‘major additions’ we mean statutory requirements that may have impacts on AW and/or production costs.

2. Is there currently any major systematic non-compliance with EU pig AW-legislation in your country or has there been any such non-compliance during the past three decades?

We obtained 10 survey responses and received three email responses to follow-up questions. In the results section, information gathered through the survey is referred to as ‘survey data’, i.e., it is based on expert comments.

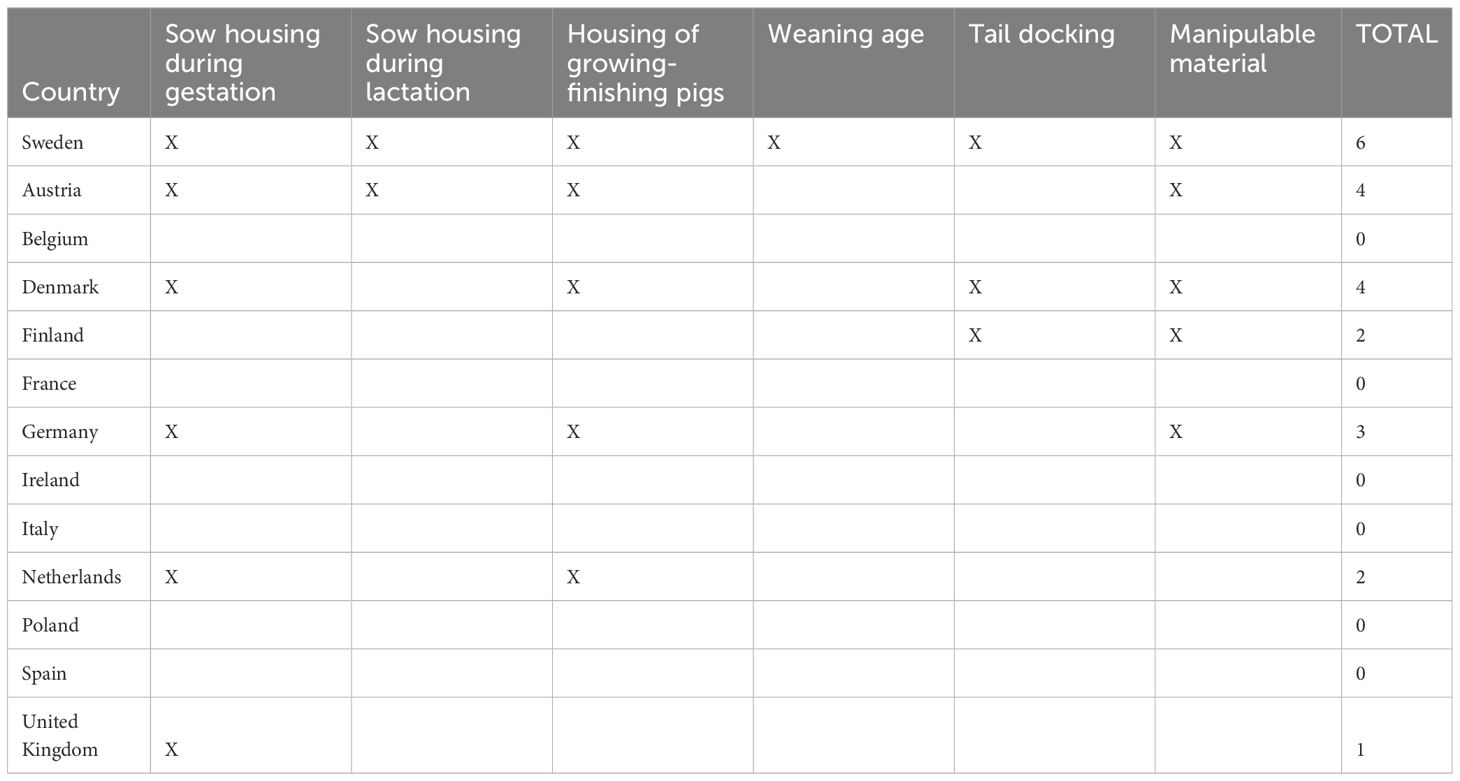

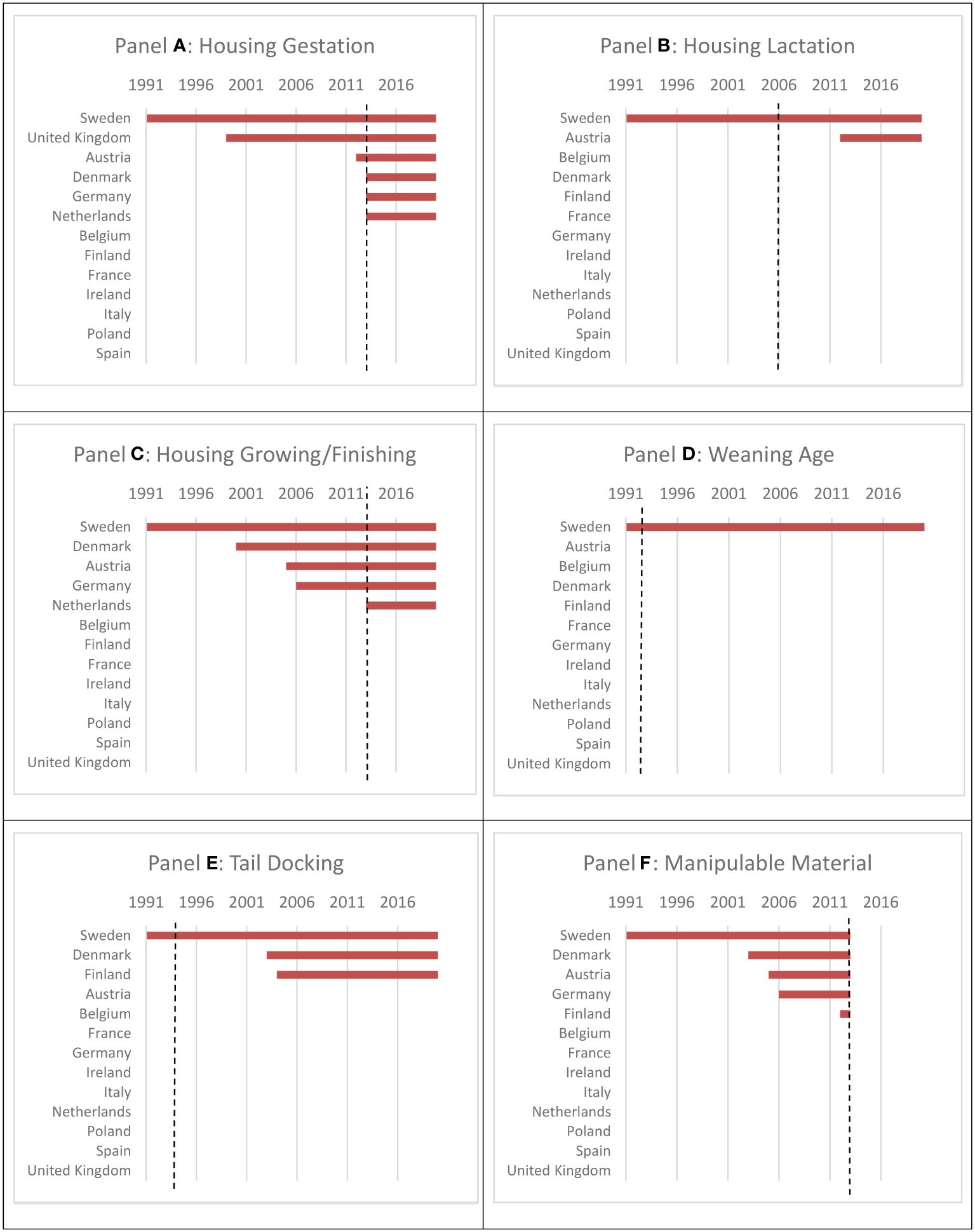

The main findings regarding on-farm pig AW are described below. For each of the six key aspects, we describe the history of the EU legislation and then summarize any differences in the level of stringency and timing of implementation in each of the 13 member countries. Countries with legislation imposing additional requirements for each key AW aspect (above EU legislation) during the period 1991-2020 are listed in Table 1, while the timing and duration of these national additions for each key aspect are illustrated in Figure 1. The year in which EU legislation on each key aspect came into force for all holdings is also indicated in Figure 1.

Table 1 European Union member countries with legislation containing additional requirements relating to six key aspects of pig welfare above the EU level during at least parts of the period 1991-2020.

Figure 1 Timing and duration of national additions by 13 different European Union member counties to EU legislation, by key aspect (panel A–F) and year of EU legislation coming into force (dashed line).

All 13 member states included in the analysis implemented, above the previous Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991), at least the minimum standards as stipulated by Council Directive 2008/120/EC (Council of Europe, 2008) in their national legislation by the 1 January 2013 deadline (Mul et al., 2010). Six member states (Belgium, France, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Spain) implemented the EU directives with no additional requirements with respect to any of the key aspects considered in the present analysis. The other seven member states (Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and United Kingdom) introduced stricter or additional AW provisions compared with the EU minimum for at least one of the six key aspects.

The first EU legislation with binding requirements on group sow housing was Council Directive 2001/88/EC (Council of Europe, 2001a), stipulating that sows and gilts (female pigs before their first litter) must be kept in groups during part of their pregnancy on all pig holdings keeping 10 sows or more. This legislation was passed in 2001 and applied to all new or rebuilt buildings from 2003, while it came into force for all holdings on 1 January 2013. Council Directive 2008/120/EC (Council of Europe, 2008) replaced Council Directive 2001/88/EC (Council of Europe, 2001a) and added further minimum standards for pig production, also came into force on 1 January 2013. In particular, 2008/120/EC (Council of Europe, 2008) stipulates that pregnant sows must be kept in group housing from four weeks after service until one week before expected farrowing. The total unobstructed floor area available per animal when gilts and/or sows are kept in groups must be at least 1.64 m2 and 2.25 m2, respectively. At least 0.95 m2 of the available area per gilt and at least 1.3 m2 per sow must be of continuous solid floor, of which a maximum of 15% is reserved for drainage openings.

In Denmark, Austria, and Germany, national legislation relating to sow housing during gestation contains additions to the EU minimum. Denmark requires slightly larger pen size, a stricter requirement that came into force at the same time as the EU minimum in 2013 (LBK nr 255 af 08/03/2013). Austria has required slightly more space than the EU minimum since 2012 (survey data) and confinement in sow stalls during gestation has been limited to 10 days since 2018 (survey data). Germany requires slightly more space than the 2013 EU minimum, an addition phased in from 2013 (BEK 22.8.2006 I2043).

Sweden, UK and the Netherlands have implemented national legislation on sow housing during gestation with more far-reaching additions to the EU level. Sweden has required group housing at all times, including during the dry and service period but not the last week of pregnancy, since 1988 (fDjurskyddslag [Swedish Animal Welfare Act] SFS 1988:534, SFS 1988:539). The UK prohibited use of sow stalls throughout the sow’s pregnancy in 1999 (Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC), 2009; SI 2007/2078; SI 2007/3070). Legislation passed in 2004 in the Netherlands and entering into force in 2013 required the same area for gilts and sows (2.25 m2), and group housing from four days after service until one week before farrowing (Stb. 2005, 146).

Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) does not specify a minimum pen size for farrowing sows, but stipulates that sows must be able to lie down, rest, and stand up without difficulty, and have a clean, adequately drained, and comfortable lying area. In Council Directive 2001/93/EC (Council of Europe, 2001b) it was specified that in the week before expected farrowing time, sows and gilts must be given suitable nesting material in sufficient quantity, unless this is not technically feasible with the slurry collection system used in the establishment. Tethering of sows and gilts was prohibited by the EU in 2006 (Council of Europe, 2001a).

Sweden is the only country with a fully phased-in requirement for loose farrowing systems, which has been established in national legislation since 1988 (SFS 1988:539). In 2004, Austria began requiring loose farrowing systems after building renovation (Pig Progress, 2013).

Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) specifies the minimum unobstructed floor area that must be available to each weaner or rearing pig kept in groups, excluding gilts after service and sows. The minimum floor area depends on the size of the pigs, and varies from 0.15 m2 for pigs weighing less than 10 kg to 1.00 m2 for pigs weighing more than 110 kg. All new buildings constructed after 1994 were required to meet this standard, while all buildings were required to meet it by 1998. In exceptional circumstances, extensions could be granted until 2005. The maximum permitted width of slatted floors for group-housed pigs is specified in Council Directive 2008/120/EC.

Several member states require a greater floor area per animal compared with the EU minimum requirements, and some member states also require a partly solid floor, which is not required by the EU legislation. Legislation in Sweden (since before 1991) and the Netherlands (since 2013) imposes the most generous floor area requirements (LSFS 1982:21; DFS 2006:4; Stb. 2005, 146). Since 2006, Germany has required slightly greater floor space for pigs larger than 20 kg live weight than specified in EU legislation (survey data). Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany (since 2000) also require a partially solid floor (survey data). In accordance, Denmark (since 2000) also require a partially solid floor, and misting systems allowing the pigs to regulate their body temperature (survey data). Austrian legislation that came into force in 2005 require a slightly larger space allowance than the EU minimum for pigs in the 85-110 kg live weight size category (survey data).

Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) specified a minimum weaning age of 28 days, unless the welfare of the sow or piglets is adversely affected, on all holdings by 1 January 1994. Council Directive 2001/93/EC (Council of Europe, 2001b) states that “piglets may be weaned up to seven days earlier (21 days) if they are moved into specialised housings which are emptied and thoroughly cleaned and disinfected before the introduction of a new group and which are separated from housings where sows are kept, in order to minimise the transmission of diseases to the piglets”.

Sweden is the only country with stricter weaning age requirements (before 1991 to 2017), with a weaning age of minimum 28 days (i.e., not average batch age of 28 days, but 28 days of age for the youngest piglet in the batch) (LSFS 1989:20). In 2017, the minimum weaning age in Sweden was reduced to 21 days for some piglets (10% per production batch) provided that certain requirements are met (SJVFS 2017:25).

Restrictions on tail docking were first introduced at EU level in 1991 through Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) entering into force in 1994, with only slight modifications in Council Directives 2001/93/EC (Council of Europe, 2001b) and Council Directive 2008/120/EC. Tail docking must not be carried out routinely, but only where there is evidence of injuries to other pigs’ tails and after other measures to prevent tail biting has been taken. Due to the continued widespread use of routine tail docking in several member states (European Commission. various years) the legally binding Commission Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a) “on the application of Council Directive 2008/120/EC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs as regards measures to reduce the need for tail-docking” and accompanying document Staff Working Document “on best practices with a view to the prevention of routine tail-docking and the provision of enrichment materials to pigs” (European Commission, 2016c) were adopted in 2016. These actions were taken to improve compliance with Council Directive 2008/120/EC. In association with Commission Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a), the Commission initiated a three-year EU action plan with a focus on information and consultation on implementation of best practices in 2017. Moreover, the commission requested all Member States to set up national action plans to reach compliance with Council Directive 2008/120/EC, in line with Commission Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a) by latest December 2018.

Sweden and Finland have forbidden tail docking, except for medical purposes. This happened in Sweden before 1991 (SFS 1988:534, SFS 1988:539). Finland’s more stringent legislation on tail docking was passed in November 2003 (survey data) and came into force in January 2004. Denmark only allows tail docking between the second and fourth day after birth, and only half the tail, in legislation that came into force in 2003 (survey data). Even though the requirements in Council Directive 2008/120/EC did not change, the National action plans to reach compliance with Council Directive 2008/120/EC, in line with Commission Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a) have involved strengthened requirements related to routine tail docking in many EU member states from 2018 and onwards.

Council Directive 91/630/EEC (Council of Europe, 1991) stipulates that all pigs must be able to obtain straw or other suitable material or objects, taking into account the environment and stocking density. The directive also stipulates that sows must be provided with a clean, adequately drained, comfortable lying area, and must if necessary be given suitable nesting material. Council Directive 2001/93/EC (Council of Europe, 2001b) specifies that in the week before the expected farrowing time, sows and gilts must be given suitable nesting material in sufficient quantities unless this is not technically feasible with the slurry collection system in the establishment. The 2001 directive also specifies that all pigs must have permanent access to a sufficient quantity of material to enable proper investigation and manipulation activities. This legislation came into force on 1 January 2013, giving member states and pig producers 12 years to implement and comply with the requirements.

Several EU member states have similar requirements to the EU minimum level that came into force on 1 January 2013, but imposed these many years before the EU deadline. Sweden has had legislation ensuring provision of manipulable material since before 1991, with some minor additions in the legislation in 2006 (LSFS 1982:21; DFS 2006:4; Lundmark Hedman et al., 2021). Denmark has required permanent access to a sufficient amount of straw or other manipulative material to meet the need of pigs for rooting material since 2003 (BEK nr 323 af 06/05/2003; European Commission. various years; survey data). Austria has required sows to be provided with harmless and sufficient material for nesting since 2005 (Lundmark Hedman, 2020; survey data). Germany has required manipulable material since 2006 (survey data). Finland has had requirements for sow nesting material since 2012 (Lundmark Hedman, 2020; survey data). Even though the requirements in Council Directive 2008/120/EC did not change, the National action plans described in section 4.5.2, aiming to improve compliance with the same Directive, are also applicable for manipulating material and have involved strengthened requirements in many EU member states from 2018 and onwards.

The audits performed by the European Commission Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety are mainly qualitative in nature and do not give a systematic or concise picture of member state compliance with EU AW directives. Member states are not audited every year, and auditors only visited a small number of farms. The recent “fitness check” of EU AW-legislation (European Commission, 2022) states that “Data available at EU level is not extensive and reliable enough to convey meaningful information about levels of compliance with the legislation on animal welfare”.

Tail docking is the key AW aspect with by far the lowest degree of compliance within EU member states (Nalon and De Briyne, 2019). This is clearly illustrated by the actions taken by the EU Commission from 2016 and onwards including legally binding Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a) on the application of Council Directive 2008/120/EC and the related requests of all Member States to set up national action plans by latest December 2018. According to audit reports between 2016 and 2018, only Sweden and Finland have sufficiently low rates of tail docking and comply with the EU legislation (European Commission. various years). Moreover, most of the investigated EU-member states are still non-compliant with respect to providing manipulable material, except for Sweden (Edman, 2014), Finland, and Poland (survey data).

Based on the deficient compliance data available, most of the 13 member states analyzed comply with the EU legislation with respect to sow housing and housing of growing-finishing pigs [aspects (i)-(iii)). Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Poland, and Portugal were asked by the EU to improve compliance with respect to sow housing during gestation in 2013 (European Commission, 2013). Moreover, most countries are in compliance with the EU’s 21-day weaning age rule, except for Ireland and the United Kingdom, according to the results of our survey.

In the analysis of six key aspects of pig AW in this study, we detected several notable patterns that are relevant for comparison of AW across the selected 13 EU member states 1991-2020. There was a clear pattern of an increased number of national AW-legislations exceeding EU minimum levels over time. In 1991, only one country (Sweden) had national additions on pig AW that exceeded the EU minimum. By 2020, seven countries had national legislation that exceeded EU minimum levels. These differences between countries may partly be explained by differences in size of the pig production and differences in emphasis towards legislation or towards private and industry standards (Keeling et al., 2012). The differences are also likely to be related to country differences in the opinion on, and relative perception of, AW by citizens (European Commission, 2007; European Commission, 2016b, 2023) and stakeholders (Keeling et al., 2012). Although there was more divergence in national pig AW-legislation in later years of the study period, it is important to note that the average level of pig AW imposed by legislation in EU member states has increased. This increase is due to a combination of higher minimum standard over time resulting from EU directives affecting pig AW and from the national additions to these by several member states. Moreover, EU and national AW legislation have also become more detailed over time, potentially initiated by EU Commission efforts to improve compliance to AW legislation during the last decade.

Another important consideration is that the national additions are in many cases unique to individual countries. This can be seen especially in national legislation concerning housing of growing/finishing pigs, where there are many different combinations of additional floor space and solid floors in different EU member countries. The national additions also vary in terms of stringency, with some additions being arguably more significant than others.

Regarding compliance with EU directives on the six key aspects of pig AW studied here, the deficient compliance data available indicate compliance with most requirements among the countries studied. Important exceptions were the requirements regarding tail docking and provision of manipulable material, where efforts to increase the compliance has been taken by the EU commission through e.g. Commission Recommendation 2016/336 (European Commission, 2016a) and the request for National action plans on the issue. Moreover, many countries had to be asked specifically by the EU to improve compliance with respect to sow housing during gestation. These efforts on improving compliance to the EU AW-legislation among member states suggests an expected improvement in compliance and documentation of the compliance, from 2018 and onwards. However, the lack of data on compliance and the non-systematic collection of such information during the period of focus in the present study make it difficult to gauge compliance with pig AW legislation. At the same time, determining the level of compliance with stricter AW-legislation is a precondition to understanding how stricter legislation actually benefits animals and impacts farms.

There are multiple country specific factors affecting pig AW as well as the relationships between AW and economic performance of the farms and competitiveness of the pig production sector. For example the level of compliance to legislation, size of pig production, presence of private and industry standards, consumer and citizen opinion and trust. However, sufficient information for comprehensive mapping on all these factors are not currently available while the legislation is the long-term foundation for the level of AW in pig production. The mapping performed in the present study shows that pig AW-legislation is dynamic both at EU and country level. Pig AW-legislation will continue to evolve and comprehensive evaluations of previous changes in legislation is needed as a basis for both future research and for discussions among decision makers at both politic and industry level.

Overall, differences in AW-legislation in the 13 EU member states with respect to the six key aspects of pig AW studied persisted to 2020. Recent and planned national legislation that has not yet come into force by 2020 and thus not included in this study, means that cross-country differences may become even greater in the future.

This study aimed to map and compare the evolution of AW-legislation and the timing of when these entered into force across a sample of EU member countries. By doing so, this paper creates a much-needed empirical basis for future studies investigating effects of changes to legislation. To capture relevant effects it is of importance to study several aspects of the legislation simultaneous and to cover a sufficient period of time, which the present study adds to previous mappings of pig AW legislation.

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request, without undue reservation.

AWa: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AWi: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. HH: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Financial support was received for research, authorship and publication from the Swedish research council FORMAS, grant number 2019-02067.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

BEK 22.8.2006 I2043 Tierschutz-Nutztierhaltungsverordnung (TierSchNutztV) (Animal Welfare Livestock Husbandry Ordinance). Available online at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschnutztv/BJNR275800001.html (Accessed 19 December 2022).

BEK nr 323 af 06/05/2003 Bekendtgørelse om beskyttelse af svin [Decree on the projection of pigs]. Available online at: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2003/323 (Accessed 19 December 2022).

Council of Europe (1991). Council Directive 91/630/EEC of 19 November 1991 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Official Journal L 340 , 11/12/1991 P. 0033 - 0038 340.

Council of Europe (2001a). Council Directive 2001/88/EC of 23 October 2001 amending Directive 91/630/EEC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Official Journal L 316 , 01/12/2001 P. 0001 - 0004 316.

Council of Europe (2001b). Council Directive 2001/93/EC of 9 November 2001 amending Directive 91/630/EEC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Official Journal L 316 , 01/12/2001 P. 0036 - 0038 316.

Council of Europe (2008). Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Official Journal L 47, 18/2/2009 P. 0005 - 0013 47.

DFS 2006:4 Föreskrifter om ändring i Djurskyddsmyndighetens DFS 2006:4 föreskrifter och allmänna råd (DFS 2004:17) om djurhållning inom lantbruket m.m. [Regulations on changes in DFS 2006:4 of the Swedish Animal Protection Agency regulations and general advice (DFS 2004:17) about animal husbandry in agriculture, etc.]. Available online at: https://djur.jordbruksverket.se/download/18.26424bf71212ecc74b08000902/1370041598351/DFS_2006-04.pdf.

Edman F. (2014) Do the member states of the European Union comply with the legal requirements for pigs regarding manipulable material and tail docking? First cycle, G2E (Skara: SLU, Department of Animal Environment and Health). Available online at: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se/7178/ (Accessed 25 October 2022).

European Commission (2007). “Attitudes of EU citizens towards animal welfare,” in Special Eurobarometer 270 Wave 66.1. European Union. Available at: http://www.vuzv.sk/DB-Welfare/vseob/sp_barometer_aw_en.pdf.

European Commission (2013) Animal welfare: commission increases pressure on member states to enforce group housing of sows. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_13_135 (Accessed 25 October 2022).

European Commission (2016a). Commission Recommendation 2016/336 of 8 March 2016 on the application of Council Directive 2008/120/EC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs as regards measures to reduce the need for tail-docking. Official Journal L 62, 9/3/2016 P. 0020 - 0022.

European Commission (2016b). “Attitudes of europeans towards animal welfare,” in Special Eurobarometer, 442 Wave EB 84.4. European Union. doi: 10.2875/884639

European Commission (2016c) Commission Staff Working Document on best practices with a view to the prevention of routine tail-docking and the provision of enrichment materials to pigs. Available online at: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/aw-pract-farm-pigs-staff-working-document_en.pdf.

European Commission (2022) Commission Staff Working Document Fitness Check of the EU Animal Welfare Legislation. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52022SC0328 (Accessed 19 December 2022). SWD/2022/0328 final.

European Commission (2023). “Attitudes of europeans towards animal welfare,” in Special Eurobarometer, 442 Wave EB 99.1. European Union. doi: 10.2875/872312

European Commission. various years Directorate Health and Food Audits and Analysis. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/audits-analysis/audit_reports/index.cfm (Accessed 25 October 2022). Audit Reports.

European Commission. Various years Directorate Health and Food Audits and Analysis. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/audits-analysis/audit_reports/index.cfm

Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) (2009). Farm Animal Welfare in Great Britain: Past, Present and Future. London, UK: Farm Animal Welfare Council.

Grethe H. (2007). High animal welfare standards in the EU and international trade–How to prevent potential ‘low animal welfare havens’? Food Policy 32, 315–333. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.06.001

Grethe H. (2017). The economics of farm animal welfare. Annu. Rev. Resource Economics 9, 75–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-resource-100516-053419

Harvey D., Hubbard C., Majewski E., Malak-Rawlikowska A., Hamulczuk M., Gebska M. (2013). “Impacts of improved animal welfare standards on competitiveness of EU animal production,” in System Dynamics and Innovation in Food Networks 2013. Eds. Rickert U., Schiefer G. (Univ. Bonn-ILB Press, Bonn, Germany), 251–274.

Keeling L., Immink V., Hubbard C., Garrod G., Edwards S., Ingenbleek P. (2012). Designing animal welfare policies and monitoring progress. Anim. Welfare. 21, 95–105. doi: 10.7120/096272812X13345905673845

LBK nr 255 af 08/03/2013 Bekendtgørelse af lov om indendørs hold af drægtige søer og gylte [Promulgation of the Act on indoor keeping of pregnant sows and gilts]. Available online at: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2013/255 (Accessed 19 December 2022).

LSFS 1982:21 Landbruksstyrelsens kungörelse om djurhållning m.m. [The Swedish Board of Agriculture’s proclamation on animal husbandry, etc.]. Available online at: http://djur.jordbruksverket.se/download/18.26424bf71212ecc74b080002327/1370040585156/LSFS%201982_021.pdf (Accessed 19 December 2022).

LSFS 1989:20. (1989). Lantbruksstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om djurhållning inom lantbruket, L100. Stockholm, Sweden.

Lundmark Hedman F. (2020). En analys av regleringen av djurskyddsområdet från 1988 och fram till idag: förändringar och konsekvenser för djurens välfärd [An analysis of animal welfare regulation from 1988 to the present: changes and implications for animal welfare] (Uppsala, Swede: Swedish Center for Animal Welfare (SCAW) report).

Lundmark Hedman F., Berg C., Stéen M. (2021). Thirty years of changes and the current state of swedish animal welfare legislation. Animals 11, 2901. doi: 10.3390/ani11102901

Mul M. F., Vermeij I., Hindle V. A., Spoolder H. A. M. (2010). EU-Welfare legislation on pigs (No. 273). Lelystad, The Netherlands: Wageningen UR Livestock Research.

Nalon E., De Briyne N. (2019). Efforts to ban the routine tail docking of pigs and to give pigs enrichment materials via EU law: where do we stand a quarter of a century on? Animals 9, 132. doi: 10.3390/ani9040132

Pig Progress (2013). Available online at: https://www.pigprogress.net/Sows/Articles/2013/5/Group-housing-requirements-lead-to-market-turbulence-1257152W/ (Accessed 25 October 2022).

Sandøe S., Christensen T. (2024). “How much do people care about pig welfare, and how much will they pay for it?,” in Advances in Pig Welfare (Second Edition). Eds. Camerlink I., Baxter E. (Woodhead Publishing, Kidlington, United Kingdom), 497–515.

SFS 1988:534 Djurskyddslag [Swedish Animal Welfare Act]. Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/djurskyddslag-1988534_sfs-1988-534.

SFS 1988:539 Djurskyddsförordningen [Swedish Animal Welfare Ordinance]. Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/djurskyddsforordning-1988539_sfs-1988-539.

SI 2007/2078 The Welfare of Farmed Animals (England) Regulations 2007. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/2078/contents/made.

SI 2007/3070 The Welfare of Farmed Animals (England) Regulations 2007. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2007/3070/contents/made.

SJVFS 2017:25 Statens jordbruksverks föreskrifter och allmänna råd om grishållning inom lantbruket m.m. [The Swedish Board of Agriculture’s regulations and general advice about pig keeping in agriculture, etc.]. Available online at: http://djur.jordbruksverket.se/download/18.6a8d504015f70e4094bab223/1509953346145/2017-025.pdf.

Stb. 2005, 146 [Official Gazette of the Kingdom of the Netherlands]. Besluit van 3 maart 2005, houdende wijziging van het Varkensbesluit en het Ingrepenbesluit (implementatie richtlijnen nr. 2001/88/EG en nr. 2001/93/EG) [Decree of 3 March 2005, amending the Pigs Decree and the Interventions Decree (implementation directives no. 2001/88/EC and no. 2001/93/EC)]. Available online at: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2005-146.html#extrainformatie.

Stevenson P., Battaglia D., Bullon C., Carita A. (2014). Review of animal welfare legislation in the beef, pork, and poultry industries (Rome, Italy: FAO Investment Centre. Directions in Investment (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i4002e/i4002e.pdf. eng no. 10.

Keywords: animal welfare, compliance, legislation, pig, pork

Citation: Wallenbeck A, Wichman A, Höglind L, Agenäs S, Hansson H and Ferguson S (2024) Brief research report: the evolution of animal welfare legislation for pigs in 13 EU member states, 1991-2020. Front. Anim. Sci. 5:1371006. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2024.1371006

Received: 15 January 2024; Accepted: 15 April 2024;

Published: 02 May 2024.

Edited by:

Giovanna Martelli, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Annalisa Scollo, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2024 Wallenbeck, Wichman, Höglind, Agenäs, Hansson and Ferguson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna Wallenbeck, YW5uYS53YWxsZW5iZWNrQHNsdS5zZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.