95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anim. Sci. , 24 April 2023

Sec. Animal Welfare and Policy

Volume 4 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2023.1163062

This article is part of the Research Topic Securing Animal Welfare in Times of Crisis and Animals' End of Life Outside Conventional Slaughter View all 6 articles

Ellen Deelen1*

Ellen Deelen1* Franck L. B. Meijboom1

Franck L. B. Meijboom1 Tijs J. Tobias2

Tijs J. Tobias2 Ferry Koster3

Ferry Koster3 Jan Willem Hesselink4

Jan Willem Hesselink4 T. Bas Rodenburg1

T. Bas Rodenburg1Farm animal veterinarians are frequently involved in animals’ end-of-life (EoL) situations. Existing literature found that the decision-making process to end an animal’s life can be experienced as complex and stressful by veterinarians. The complexity of the process may find its origin in the multiple medical and non-medical aspects that veterinarians consider coming to their decision. Although research provides insight into what considerations are at stake, the literature does not provide information on how these aspects affect the decision-making process. This study explores how different considerations affect the decision-making process of farm animal veterinarians in EoL situations. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nineteen farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands. During the interviews, case scenarios in the form of vignettes were used to identify and explore the considerations that play a role for these veterinarians in EoL decision-making. Based on the analysis of the interview data, we discovered that farm animal veterinarians consider EoL situations using one of three identified frames: function, prospect, and duty. These frames illustrate one’s perspective on the interplay of medical and non-medical aspects. Whereas veterinarians for whom the function frame is dominant focus on the human-centred function that an animal fulfils, veterinarians for whom the prospect frame is dominant focus on an animal’s prospects based on the animal’s living conditions and the influence of the owner. Veterinarians for whom the duty frame is dominant focus on the owner’s legal position towards the animal, illustrating a clear distinction between the veterinarian’s professional duties towards the animal and the duty of care of the animal owner. As such, the key contributions of this study are the discovery of the importance of the interplay between considerations in EoL decision-making and the frame-specific approach of veterinarians. The identified frames may relate to the coping strategies of veterinarians dealing with the complexity of EoL situations.

During an animal’s life, unforeseen events can lead to decisions regarding the ending of an animal’s life. These end-of-life (EoL) situations may lead to questions regarding euthanasia of an animal. Whereas the decision whether to euthanize an animal is quite common when we consider animals kept for companionship or educational purposes, for animals kept on farms discussing this decision is less conventional as their lives are normally considered to end at the slaughterhouse. In all these EoL situations, farm animal veterinarians are frequently involved. They fulfil various roles in these situations, including the role of advisor of the animal owner in the decision-making process, as performer when executing euthanasia, and as surveillant when monitoring animal owners or caretakers handling EoL situations (Deelen et al., 2022). In all these roles, veterinarians use their knowledge and experience in animal health and welfare to make a veterinary assessment of the medical state and prognosis of the animal patient. As a logical consequence, the health and welfare interests of the animal are an essential aspect of EoL situations. However, literature shows that the decision to end an animal’s life is not merely based on the health or medical situation of the animal. Non-medical interests of different stakeholders such as the animal owner, the individual veterinarian, and the immediate professional environment strongly influence the decision-making process in veterinary practice (Martin and Taunton, 2006; Shaw and Lagoni, 2007; Batchelor and Mckeegan, 2012; Hartnack et al., 2016; Kondrup et al., 2016).

The complexity of multiple interests at stake and potential uncertainty about how to prioritize competing responsibilities can lead to ethical problems for veterinarians (Morgan Carol, 2007). Several studies have documented that veterinarians face various ethical problems in EoL situations. Examples are euthanasia requests for healthy animals, suboptimal treatment due to financial constraints of the animal owner and prolonged treatment of animals with severely compromised health (Morgan Carol, 2007; Hartnack et al., 2016; Kipperman et al., 2018). In these examples, veterinarians face potential conflicts of duties when the desires of the animal owner are in conflict with the interests of the animal. Having responsibilities towards both the animal and the owner can be morally challenging for the veterinarian to deal with these duty conflicts, as the best outcome in these situations may not be obvious to the veterinarian. These complex situations can be stressful and may lead to moral stress among veterinarians (Rollin, 2011; Moses et al., 2018; Dürnberger, 2020). Especially the decision-making process is considered to contribute to stress, as a qualitative study among veterinarians showed that navigating the process towards euthanasia is experienced as a greater challenge than the act itself (Matte et al., 2019).

Gaining insight into how different considerations play a role in the EoL decision-making process of farm animal veterinarians is important 1) to better understand the complexity of these decisions and 2) to provide knowledge on what may help veterinarians dealing with this complexity to potentially reduce moral stress in EoL decision-making. In recent years, research predominantly generated knowledge about which considerations are relevant to veterinarians in the decision-making process (Yeates and Main, 2011; Batchelor and Mckeegan, 2012; Hartnack et al., 2016; Kipperman et al., 2018; Springer et al., 2019). However, information on how these considerations affect the decision-making process is lacking. Most of these studies focused on veterinarians in the field of small animal practice. Information regarding veterinarians in farm animal practice is limited. In short, there is a lack of insight into how various considerations play a role in EoL decision-making. In addition, specifically for farm animal veterinarians, there is very little knowledge of EoL decision-making in general. As a result, this study’s first objective is to better understand how different considerations affect the decision-making process of farm animal veterinarians in EoL situations. A common qualitative method to study participants’ attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and norms regarding sensitive topics is the use of vignettes (Hughes and Huby, 2002; Hughes and Huby, 2004; Harrits and Møller, 2021). Vignettes are described as fictional cases. They consist of text, images or other stimuli which are presented to collect the participant’s responses to the presented information (Hughes and Huby, 2002). The study’s second objective is to evaluate the usefulness of concepts from existing literature as groundwork for our qualitative study. ‘Veterinary opinions on refusing euthanasia: justifications and philosophical frameworks’ by Yeates and Main will be used for this purpose.

This study is part of a larger qualitative study regarding the experiences of veterinarians with EoL situations. Results regarding veterinarians’ roles and responsibilities in EoL situations have already been published (Deelen et al., 2022). The current paper focuses on the considerations that play a role in the decision-making process of veterinarians in EoL situations.

Between June and October 2021, the first author conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with nineteen Dutch farm animal veterinarians. As a veterinary graduate, the interviewer has experience as a veterinary student with the practices explored in the current research project. During the interviews, vignettes were used to identify and explore the considerations that play a role for these veterinarians in EoL decision-making. Ten to fourteen days in advance of the interview two written vignettes were emailed to each participant. Participants were asked to consider to what extent they would agree with euthanasia of the animal in each of the vignettes. In the guiding email, participants were informed that they could discuss their considerations regarding the vignettes during the interview. By sending the vignettes in advance, participants had time to prepare for the interview. Consequently, participants were enabled to share all the considerations in their decision-making process rather than their preliminary thoughts on relevant considerations when the vignettes would have been presented during the interview. Participants were not restricted from discussing the provided material with peers or other persons as this could help them to formulate their thoughts and provide a more holistic answer during the interview.

Each vignette describes an example of an EoL situation by using scenarios (see “2.2 Vignettes” for the used vignettes). The first scenario includes information regarding various case characteristics, such as the current health status of the animal patient, the medical treatment if applicable, the owner’s financial situation and the relation between the owner and the animal. After the first scenario, two or three additional scenarios of the EoL situation are presented including variations in its characteristics. The design of the vignettes was based on available literature on EoL case scenarios and considerations in EoL decision-making by veterinarians (Martin and Taunton, 2006; Morgan Carol, 2007; Yeates and Main, 2011; Batchelor and Mckeegan, 2012; Hartnack et al., 2016; Kondrup et al., 2016; Kipperman et al., 2018; Matte et al., 2019; Springer et al., 2019). Moreover, the design of the vignettes was adapted to the Dutch context in which most farm animal veterinarians work in a species-specific practice. Due to this differentiated way of working, farm animal veterinarians visit livestock kept in various contexts such as on farms, in petting zoos, or at private homes. Each of the vignettes was reviewed upfront on formulation and accuracy by two farm animal veterinarians.

During the interview, participants were asked to orally elaborate on how different considerations affect the level of agreement with euthanasia of the animal in the different scenarios of each vignette.

We made use of two vignettes during the interviews, a vignette about a beef calf with a fracture and a vignette concerning a lame pig affected by claw lesions. Below both vignettes are presented. In each vignette, the case characteristics that differ between the scenarios are shown in bold.

Vignette ‘beef calf with a fracture’

a. One of your beef cattle farmers calls you about a calf. The four-week-old calf is trampled by its mother. Consequently, the calf has a closed fracture of the tibia shaft. The fracture has an optimistic prognosis when treated with a plaster cast. The cast needs to be replaced once every 2-3 weeks in a timeframe of 6 up to 8 weeks. The farmer asks you to euthanize the calf, as treatment is more expensive than the monetary value of the calf.

b. As case a, but now it concerns an open fracture of the tibia shaft.

c. As case a, however now the farmer indicates that he lacks the financial means and the time to provide the required care for the calf.

d. As case a, but now it concerns an open fracture of the tibia shaft and the farmer indicates that he lacks the financial means and the time to provide the required care for the calf.

Vignette ‘a lame pig’

a. You visit a pig at the local petting zoo. The pig is lame and suffers from chronic claw lesions. So far the pig is treated for two weeks, however, no improvement is noticed. The pig is seen as ‘the icon’ of the zoo and attracts a lot of visitors. The petting zoo owner, employees and visitors are very attached to the pig and therefore euthanasia is not an option from their perspective. They ask you to save the animal no matter what.

b. As case a, but now the pig is treated for four weeks and no improvement is noticed.

c. As case a, but now the zoo owner asks you to save the animal to ensure that the number of visitors won’t decline.

The inclusion criterion we used for the recruitment of interview participants was: individuals working as farm animal veterinarians in a general practice clinic in the Netherlands with a caseload consisting predominantly of the healthcare of ruminants and small ruminants, pigs, poultry, or a combination of these animal species. These sectors were chosen as most farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands work in these sectors. To discover a diversity of responses and potential patterns in the interview data, we selected participants to create a diverse participant pool that 1) varies in years of working experience, 2) is geographically spread throughout the Netherlands, and 3) has an approximate 50/50 ratio between male and female veterinarians. The selection of participants was done using purposive sampling via the snowball method (Polkinghorne, 2005) resulting in a mixed group of veterinarians. Eligible participants were recruited for voluntary face-to-face interviews. After the initial contact, participants received an information letter (Supplementary material 1) about the study’s objective, study design and data collection, and also received an informed consent form (Supplementary material 2). The number of interviews depended on the point of saturation, i.e. when no new information was detected in the interviews.

Interviews were structured based on an interview guide with open-ended questions. The open-ended questions gave the interview a conversational character creating the opportunity for participants to share their thoughts and experiences, without the restriction of predetermined response options. As we steered participants in discussing their considerations by using the vignettes, in-depth follow-up questions were asked. These follow-up questions were used to 1) diminish the steering effect of the vignettes, 2) get a better understanding of the background of the participant’s answers, and 3) reduce the risk of socially desirable answers. The interview guide (Supplementary material 3) was developed and tested on two veterinarians fitting the selection criteria before the interviews. Based on the feedback from these test interviews, the interview guide was established as no major revisions were needed. All interviews took place at a location chosen by the participant. Before the start of the interview, the interviewer informed the participant about the structure of the interview and addressed any potential questions. Subsequently, approval for an audio recording of the interview was requested. With the oral and written consent of the participant, the interview started following the interview guide.

Audio files were transcribed using Amberscript™ (Version August 2021, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). All transcripts were reviewed by the first author to ensure quality and accuracy. Any information in the transcripts which related to a specific person or veterinary practice was replaced by nonidentifiable descriptors (e.g. ‘colleague’ or ‘veterinary practice’).

The interview transcripts were coded using NVivo™ qualitative analysis software (Version Release 1.5.1). The analysis was conducted using an inductive approach. To start our data analysis, the authors created codes and a codebook based on literature (Yeates and Main, 2011). As research on how considerations affect the decision-making process is lacking, the codebook was primarily based on literature concerning which considerations affect this process. From the available literature, the article by Yeates and Main is one of the only ones to document their data on relevant considerations in a structured and transparent manner allowing replication in the form of a codebook. Therefore, the work of Yeates and Main (2011) was a suitable starting point for our codebook. Five interviews were coded by two of the authors with help of the first version of the codebook during the first coding round. Based on the first coding round, the codes and codebook were revised and refined by three of the authors. Using the second version of the codebook, the two authors coded the same interviews once more and a subsequent discussion regarding the coding followed among three of the authors. The results of the discussion rounds were reviewed among all authors. No major revisions of the codebook were needed. After this iterative reflective process, the finalized coding template (Supplementary material 4) was applied to the full data set to characterize patterns and diversity of responses in the interview data.

This research project was reviewed and approved by the Science-Geosciences Ethics Review Board (SG ERB) of Utrecht University on May 28th 2021 (reference: subject ERB Review DGK S-21552).

In the following sections, results are presented using quotes. All quotes are translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability. We present direct quotes from veterinarians in italics. In some of the quotes, additional words are inserted to clarify the meaning of the quotations. These additional words are placed between square brackets. Filler words are replaced by a set of three periods in the quotation. Abbreviations for participants’ references are used for all quotes, based on the species to which the veterinarian is devoted, Pi for pigs, Po for poultry, and Ru for ruminants. A sequential number is added to identify the individual participant but still retain anonymity (e.g. Pi1 = the first pig veterinarian interviewed).

Nineteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten male and nine female farm animal veterinarians. Of these participants, seven veterinarians worked with ruminants and small ruminants, eight veterinarians worked with pigs, and four veterinarians worked with poultry. Five veterinarians also worked with companion animals or horses. Six of the participants had less than five years of experience, four participants had five to ten years of experience, four others had ten to fifteen years of experience and five of the participants had more than fifteen years of working experience.

The interviews took between 45 and 120 minutes.

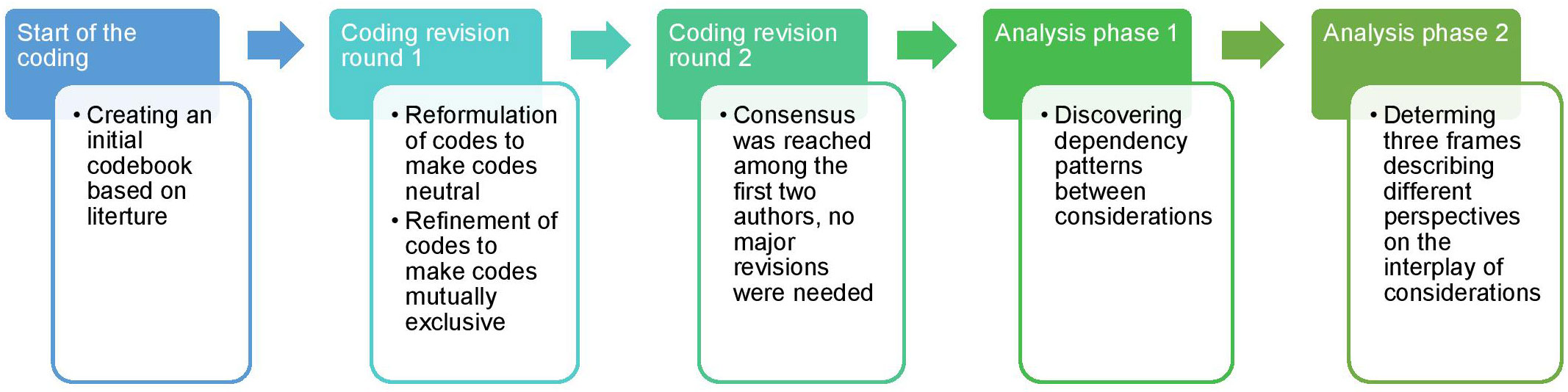

To evaluate the usefulness of concepts from existing literature as groundwork for our qualitative study, the analysis steps are presented in detail as part of the results. Figure 1 is a visual representation of these steps.

Figure 1 A visual representation of the steps of the data analysis. The coding was started by creating an initial codebook based on literature. Subsequently, two rounds of vision followed to finalize the codebook. Thereafter, the coding results were analyzed in two phases, leading to the determination of three frames.

To start the data analysis, the authors created codes and a codebook based on the article ‘Veterinary opinions on refusing euthanasia: justifications and philosophical frameworks’ by Yeates and Main (2011). We used this article as it provides insight into the considerations of veterinary surgeons regarding euthanasia decisions using a qualitative research method. The resulting codebook consisted of 10 high-level codes with a total of 26 lower-level codes. With this first version of the codebook, we coded five interviews during the first coding round.

Based on this first coding round we found that the codes based on Yeates and Main (2011) were not neutral nor mutually exclusive. The codes were, therefore, revised in round 1. To explain how the codes were revised, we will use the code ‘convenience’ as an example. First, we reformulated the codes to make them neutral. ‘Convenience’ was therefore reformulated as ‘motivation’. Neutral codes help to code both the presence and the absence of a specific topic in the transcripts. Second, the codes were refined to ensure that all codes were mutually exclusive. The data revealed that there were two forms of motivation mentioned by participants, namely the motivation to care and the financial motivation. The code ‘motivation’ primarily covered both aspects of care and finance. Therefore, the code ‘motivation’ was not distinctive enough to code our data. We subsequently created the codes ‘care motivation’ and ‘financial motivation’. Revision round 1 led to a second version of the codebook consisting of 8 high-level codes with a total of 30 lower-level codes.

The second version of the codebook was used to recode the same interview transcripts once more. In revision round 2, the authors discussed any discrepancies until a consensus was reached. No major revisions were needed. Subsequently, all transcripts were coded using the second version of the codebook. The result of the second round of coding was a list of independent considerations described by the participants. The result of this coding round was discussed among the authors. During the first analysis phase, dependency patterns between the considerations emerged. We found that participants did not express their considerations as stand-alone arguments, but rather would argue in the form of ‘if consideration A then B’.

One of the participants reflects on this dependency between considerations as follows: “It is kind of remarkable to think that, whether you agree with euthanasia, seems like an emotional consideration. However, that is not what it should be of course. You should actually say ‘this animal should be euthanized and this animal should not be euthanized.’ Though in different circumstances you make different decisions or you can have a different feel regarding the situation. With one animal you say “well, I think this animal should be euthanized as quickly as possible because I estimate that this animal will not receive appropriate care’ and with another animal, you think ‘the animal is in the same medical situation, though I accept that we keep this animal alive because I know it will receive better care’. That really makes a difference.” (Ru5)

As a result, we started a second analysis phase where we focused on the relations between considerations. The interpretation of the results of the second round will be presented in the section below.

During the interviews, participants were asked to elaborate on how different considerations play a role in their level of agreement with euthanasia in the different scenarios of the vignettes. In each of the vignettes, we introduced case characteristics including the current medical status of the animal patient, medical treatment, the financial situation of the animal owner and the relationship between the animal owner and the animal.

While discussing the vignettes, participants discussed the considerations we included in the vignettes by describing the interplay between considerations rather than considerations as independent factors.

“My considerations were the prognosis of the animal and the amount of care needed to keep the prognosis optimistic. If we look at a fracture, then a closed fracture has a much better prognosis than an open fracture. So then it is estimating the motivation of the animal owner, as he or she plays a role in the prognosis as well. That should be in balance in the end. If I think that this animal owner is not capable to provide sufficient care, then euthanasia is something I consider earlier than when I think the animal owner is motivated to do whatever it takes. So that is it I think, the balance between these things. And the financial considerations are always there. For us [as a veterinary practice] as well. In the end, I need to decide how much time and energy I can invest, considering whether I can send an invoice for my services to the animal owner. Is the animal owner willing to pay and it is a responsible choice for the animal, whose financial value is much lower?”(Ru5)

In this quote, the participant describes the relationship between the owner’s care motivation, the owner’s financial motivation, and the prognosis. As the veterinarian narrates, the interplay of these considerations affects the level of agreement with euthanasia.

Besides the fact that participants discussed the interplay of considerations, participants also add information to the vignettes. As an example: “A calf or also a chicken are animals for utility. So there must be of course some … it should be in proportion, of course, I don’t think you should treat such an animal all the way, that is just not realistic.” (Po4)

In this example, the veterinarian introduces information regarding the function the animal fulfils. This function appeared to be a relevant consideration from the veterinarian in discussing the vignette, as the consideration is actively introduced by the participant. During the conversation, the consideration introduced by the participant is discussed repeatedly, as can be seen in the following quote:

“At the moment he says: ‘but I don’t have the financials means’, then I thought: I don’t fully agree with that. Or at least. you won’t perform extreme surgery or something like that on such an animal, I do understand that. Though, if it is something relatively simple, then I think the financial aspect. I would oppose or if necessary I would try to find another solution for the financial constraint. You could perhaps provide some support on behalf of the practice.” (Po4)

The participant describes that the function an animal fulfils influences the participant’s perspective on, in this scenario, the level of agreement with euthanasia based on the financial situation of the animal owner. The function directs how the participant shapes the interplay of considerations.

During our analysis, we found in total three different ‘frames’ among participants. A frame is functioning as a guiding framework in which one consideration is dominant in how a participant shapes the interplay of considerations. One individual participant can recognize him- or herself in more than one of the frames, however, one of the frames prevails according to our analysis. The discovered frames will be discussed below.

Veterinarians describe that the human-centred function that an animal fulfils gives direction on how they shape the interplay of considerations in an EoL situation. In the vignettes used in this study, the calf’s function was to produce animal products whereas the pig was kept for educational purposes.

In case an animal’s function is seen as the production of animal products, participants describe that this function affects how they shape the interplay of the prognosis and finances. On the one hand, participants describe that they would give resistance if an owner wants to euthanize an animal with an optimistic prognosis based on financial reasons. They would try to motivate the animal owner to choose treatment if that treatment comes with ‘reasonable’ costs and is likely to lead to the recovery of the animal. This implies that veterinarians for whom the function frame is dominant ask for a minimum standard regarding the provided care by the animal owner. On the other hand, veterinarians express to be understanding when an owner prefers to euthanize an animal with a less optimistic prognosis based on financial reasons. Veterinarians describe that these animals are kept primarily to provide a profit for the owner due to which there are understandable limits to the financial willingness of an owner to treat an animal.

“A closed fracture has a much more optimistic prognosis than an open fracture. In case it is a closed fracture I would discuss the option to treat it with the animal owner. With an open fracture, the prognosis is worse. So then it can be the best option to euthanize the animal. The prognosis is then quite doubtful and yes. finances are also relevant I think. If an animal owner needs to spend a lot of effort and time and in the end, the result is not there [a successful treatment of the animal], he lost a lot of money. So yes, I could euthanize the calf with the consent of the owner.” (Ru7)

“Financial means are a valid argument I think. If it only cost money., it remains an animal for production so in the end, it needs to generate money. And if that is not the case, then it is better to say goodbye timely.” (Pi4)

In case an animal’s function is seen as fulfilling an educational purpose, participants describe that this function affects how they shape the interplay of the prognosis, the emotional bond between the owner and the animal and the finances. Regarding finances, participants indicate that there is a difference in whether an animal is kept for profitability goals or not. In the case of an animal kept in a petting zoo, the animal serves a non-profitable purpose and thus finances are in their perspective of less relevance compared to animals kept for profitable goals. The animal’s interests in terms of the current medical situation and prognosis should, from the participants’ perspective, be leading in the decision-making process. Especially when the animal owner wants to prolong the animal’s life based on the emotional bond, participants stress the great importance of protecting the animal’s interests.

“Look, if you are really attached to an animal, and the animal’s prognosis is really bad, then I think if you are really attached to the animal that you should make the choice to say: we stop here and say goodbye. Otherwise, you are apparently not really attached to the animal, as you keep the animal alive for your own interest. Even though that is not desirable for the animal itself.” (Pi5)

“I got the impression that this specific animal was very important to the employees or the visitors. So that is of course very different from a sow farm for example where they keep such an animal as well but where the role of being an icon is not present. A farmer will then look much more at the prognosis and the costs to make a cost-benefit analysis. In the case of a petting zoo, the emotional aspects are more relevant. Though I think that especially in that situation you should be able to explain it from the animal’s perspective, so you should think from the animal’s point of view.” (Po4)

Veterinarians for whom the ‘function frame’ is dominant can thus come to different EoL evaluations of the same animal fulfilling different functions, e.g. an EoL situation of a pig kept on a farm for production goals versus a pig kept as a companion.

Participants reflect on the presumed prospect of the animal when discussing EoL situations, as Po2 narrates: “You should always try of course, if an animal has a future with a life worth living. However, if I doubt that, I will euthanize the animal.”

Veterinarians elaborate on two aspects that, from their perspective, influence an animal’s prospects.

The first aspect they describe is the living conditions of an animal. By living conditions, participants mean for example the housing of an animal and the expected lifespan in these conditions. This first aspect is thus not dependent on the EoL situation but is an aspect that affects an animal’s general prospect. Participants describe that if the living conditions are not very optimistic for the animal itself, they would be more critical to prolonging that animal’s life. On the contrary, when the prospect of an animal is presumed as optimistic for the animal itself these veterinarians would be more inclined to prolong the animal’s life. Ru6 discusses this first aspect based on a personal experience: “That was a calf with a closed fracture. Then the prognosis is quite good [compared to an open fracture]. So the calf is currently one month old. He will be slaughtered at eight months, so he will die anyway cruelly said. But if he needs to be treated for eight weeks, he is three months at the end of his treatment. Then he has six months left and then what.? The prognosis of such a fracture is quite good, however, how good is his prognosis as a beef calf?”

The second aspect described by participants is the influence of the animal owner on the animal’s prospects. They reflect on the owner’s motivation to care and on the financial situation of the owner. Regarding the motivation to care, participants describe that in case the owner lacks the motivation to provide sufficient care, the prospect of the animal is likely to decline under influence of the animal owner. Consequently, veterinarians indicate considering euthanasia earlier than when the owner’s motivation to care is sufficient. As an example: “Another example is that of a sheep kept as a ‘companion animal’. The sheep had a fracture between his elbow and shoulder, so a difficult spot. I thought ‘we will have to see what happens.’. I taught these owners how to change the bandages, so they could change these every week. They were very precise, so they checked the sheep frequently and gave the needed medication as prescribed. So that sheep recovered. And I know that when the sheep gets arthrosis at an older age, he will be treated according to his needs. So in such a situation, I think that this sheep has a good prospect. In case that prospect is not that good, what is an animal than waiting for?”(Ru6)

Regarding the financial situation of an owner, veterinarians discuss on the one hand a lack of financial means to provide sufficient care and on the other hand a lack of motivation to make costs.

If an animal owner lacks the financial means to care for an animal due to for example financial problems, veterinarians indicate considering euthanasia less quickly. They express being motivated to give a reasonable discount if euthanasia would be chosen due to a lack of sufficient financial resources. Their motivation to provide this discount is that the animal’s prospect would be optimistic if the financial situation of the owner was not the limiting factor.

In case an owner has the financial means to provide care but is unmotivated to make costs, veterinarians discuss doubt about the general care motivation of the owner. As this brings the animal at risk to suffer, veterinarians express the urge to protect the animal. If they cannot motivate the animal owner to make financial resources available, euthanasia becomes more likely for these participants, as this at least prevents the potential suffering of the animal.

“When someone is unwilling to pay for the needed care, I doubt more about how that person provides care anyways. I am more willing to give a discount when someone is willing to provide care but lacks the financial means than when the financial means are there but someone is unwilling to spend the money. When an animal owner says ‘I don’t have enough money but if I had it I would have spent it’, I disagree with euthanasia more than when someone has the money but is unwilling to spend ‘because they don’t care that much’. Euthanasia makes then more sense perhaps, as I immediately get a gut feeling that someone lacks the willingness to provide care. … Perhaps I am even more motivated on those farms to say ‘I am here for the animal’, meaning I need to prevent the animal from suffering so then it will be euthanasia. For me, it is easier to choose euthanasia, which is free of pain, than saying: you treat such a calf with a discount, but also with insufficient care and long-term suffering. Then I think you chose something you could have prevented by euthanasia. So even a closed fracture can lead to euthanasia at some farms, whereas on other farms that is not the case.” (Ru2)

Concluding, veterinarians for whom the ‘prospect frame’ is dominant focus on the animal’s prospects based on the animal’s living conditions and the influence of the animal owner. These two aspects can differ strongly between farms. Consequently, it occurs that an animal in the same medical condition would be treated on one farm and euthanized on another farm based on the animal’s prospect.

While discussing the vignettes, participants emphasize the position of the animal owner towards the animal. Legally the animal owner has the decision-making power regarding the animal, as animals are considered the legal property of the owner in Western jurisdiction. Participants describe that, from their perspective, the decision-making power of the owner comes with a duty to provide care to the animal. This results in a clear distinction between the veterinarian’s professional duties towards the animal and the duty of care of the animal owner. Po3 describes this as:

“In the end, I have some kind of duty to care until the duty of care of the owner. They have the final responsibility thus I cannot do more than give advice. When the owner then doesn’t consent to my advice, yes. then it stops there.”

The distinction of responsibilities between the veterinarian and the animal owner leads to limited possibilities for the veterinarian to act in EoL situations. First, veterinarians are dependent on the consent of the owner due to the owner’s legal decision-making position. In case an owner does not consent to provide medical care or to euthanize an animal in an EoL situation, the veterinarian is not allowed to act contrary to the owner’s decision. Second, participants describe being reluctant to take over the owner’s duty to care. Ru5 discusses this in an example: “To what extent are you as a veterinarian responsible to provide care, in case the animal owner is unable to or unwilling to provide sufficient care? We then say that is not our responsibility. We have the responsibility to provide care, however, we are not financially responsible for that care. In the end, the animal owner is responsible to cover the costs of the needed care. In some cases, we provide some discount, though we cannot take over the care, as we neither take over the ownership of the animal.”

Participants describe that these limited possibilities to act now and then lead to situations in which they either euthanize an animal that could be cured when medical care would be provided or in which they leave an animal alive that should have been euthanized from their perspective.

“We can’t solve other people’s problems all day long when they are unmotivated to solve their problems themselves. In the end, they have to take care of the animal. I have a duty to provide care, to help that animal. However, if they don’t help the animal, and consequently the animal suffers from a lot of discomfort, then euthanasia is a realistic option.” (Po3)

This study aimed to understand how considerations affect the decision-making process of farm animal veterinarians in EoL situations using qualitative data. We found that veterinarians shape the interplay of considerations rather than considerations as independent factors in their decision-making process. This finding resembles previous literature showing that the decision-making process in veterinary practice is not merely based on the health situation of the animal, but also on the interests of other stakeholders such as the animal owner (Martin and Taunton, 2006; Shaw and Lagoni, 2007; Batchelor and Mckeegan, 2012; Hartnack et al., 2016; Kondrup et al., 2016). Our results add to this literature by identifying additional considerations relevant for farm animal veterinarians, including the function of an animal, the (general) prospect of an animal, and the owner’s duty of care. Moreover, the current study contributes by describing how veterinarians discuss their considerations as an interplay of various arguments rather than as stand-alone arguments. This interplay of considerations has, to our knowledge, not been described in the current form for veterinarians in farm animal health.

How the interplay of considerations is shaped varies among participants and depends on the frame that is dominant for an individual veterinarian. In total three frames were identified. The fact that three frames were identified among veterinarians is noteworthy, as most participants followed their education at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University. Although the educational program has developed within the past years, a more homogeneous profile might be expected from graduates of the same faculty. A potential explanation for this diversity may be found in the position of farm animal veterinarians within the Netherlands. This position is, among other things, characterized by three aspects: the applicable legal framework, one’s perception of their role as a professional, and their point of view towards animals. Regarding the legal aspect, it is notable that Dutch farm animal veterinarians are not bound to a legal requirement to justify the ending of an animal’s life, whereas ending the life of an animal without justification is illegal in some Western countries. Besides this legal aspect, we found that farm animal veterinarians fulfil multiple roles in EoL situations and the combination of roles differs between individual veterinarians (Deelen et al., 2022). Differences in how one perceives one’s professional role could affect how one shapes the interplay of considerations in EoL decision-making, e.g. a professional who perceives the role of animal advocate may shape the interplay of considerations differently than veterinarians who do not perceive that role. Lastly, individuals may vary in their perception of the value of animals. A first aspect of this value is the valuing of an animal’s life. Within life, a second aspect is the valuing of the animal’s interests. Together these aspects affect one’s perception of the animal’s value. The value one assigns to an animal can affect the EoL decision-making process in the way one prioritizes the animal’s interests towards the interests of other stakeholders.

When we consider the three frames, we found that, although farm animal veterinarians work in animal sectors that are predominantly driven by profitability, their decision-making process in EoL situations is more nuanced. By nuanced, we mean that in all frames it became clear that participants did not base their decision to end an animal’s life merely on financial considerations. Although this nuance may be in line with duties for veterinary professionals (Royal Netherlands Veterinary Association, 2022), the profit-based character of the sectors in which they work may create a plausible risk that the financial and instrumental value of the animal would prevail in EoL decision-making.

When we explore the frames in more detail, we see variation between the three frames when it comes to the described duty of veterinarians to prioritize the interests of the animal patient (Main, 2006; Rollin, 2006). In literature, this duty is often referred to as the role of animal advocate or ‘the Pediatrician Model’ (Rollin, 2006). In the ‘prospect frame’, the animal’s health and welfare are the central concern. In situations where the animal’s interests are at serious risk, veterinarians can be in favor of euthanasia to prevent the animal from (further) suffering. Sometimes this leads to euthanasia out of precaution, when veterinarians had negative experiences with the care provided by an animal owner in the past. In comparison to the role of animal advocate, it is notable that the ‘function frame’ distinguishes the interests of the animal based on the human-centred function an animal fulfils. Whereas the interests of animals kept as companions or for educational purposes are comparably prioritized by the animal advocate and the function frame, the interests of the animal owner emerge more prominently when an animal is kept to produce animal products in the function frame. In both the ‘prospect frame’ and the ‘function frame’, we saw that participants were willing to provide reasonable financial support in case a lack of finances would be the ultimate reason to euthanize an animal. The willingness to provide financial support can be interpreted as the veterinarian who is prioritizing the animal’s interest and who attempts to motivate the animal owner to do the same. The opposite was found in the ‘duty frame’, as veterinarians described being reluctant to take over the (financial) responsibility to care for the animal. This could be interpreted as ‘the Garage Mechanic Model’ described by Rollin (Rollin, 2006). In this model, the veterinarian’s primary obligation is directed to the animal owner resulting in prioritizing the owner’s interests over the interests of the animal. This is in contrast with ‘the Pediatrician Model’ where the veterinarian’s primary obligation with the animal patient’s interest. Although the ‘duty frame’ seems comparable with ‘the Garage Mechanic Model’ at first glance, the participants for whom the ‘duty frame’ is dominant did indicate being willing to prioritize the interests of the animal. We, therefore, consider the reluctance to take over the (financial) responsibility to care for the animal as a potential signal of a coping strategy to deal with complex EoL situations. Even though the participants expressed being willing to prioritize the animal, they emphasized that they had to deal with the fact that the final decision-making power to prioritize the animal’s interests is in the hands of the animal owner. Experiencing this situation can be stressful and can be accompanied by moral stress (Rollin, 2011; Moses et al., 2018). As Matte et al. (2019) described, the decision-making process towards euthanasia is experienced as stressful, in contrast to the act itself. By focusing on which duties belong to whom, veterinarians may better cope with the possible presence of moral stress in complex EoL situations. Veterinarians for whom the ‘prospect frame’ or ‘function frame’ is dominant may have found a different coping strategy to deal with the potential presence of moral stress in EoL decision-making, or potentially suffer more from it. During the interviews, two potential external sources of help were indicated and discussed by the veterinarians that could support veterinarians to deal with EoL-related stress. In general, veterinarians emphasized the benefit of consulting peers to deal with stressful situations in practice. Specifically for EoL situations participants stressed the need for the proper education of future veterinarians on dealing with EoL situations.

This study increased our understanding of how different considerations affect the decision-making process of farm animal veterinarians in EoL situations. Moreover, it increased the usefulness of concepts from existing literature as groundwork for qualitative studies. Based on the analysis of our data, we conclude that although concepts from existing literature were useful as groundwork, adjustments to these concepts were needed to answer our research question on how different considerations affect the decision-making process in EoL situations. Rather than using isolated arguments, farm animal veterinarians base their decision-making on the interplay of considerations in EoL situations. Among veterinarians we see differences in how this interplay of considerations is shaped, depending on the three frames we identified. These frames may relate to the coping strategy of veterinarians. As our results focus on farm animal veterinarians, future research among veterinarians working with companion animals or horses could provide insight into the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, we recommend research into the usefulness of the current frames in supporting (future) veterinarians in EoL decision-making. The frames could, for example, function as training material to help veterinarians evaluate and reflect on their EoL decision-making process. Moreover, the frames could be used for the development of decision-making support tools or could be implemented in existing decision-making support tools (Herfen et al., 2018).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Science-Geosciences Ethics Review Board (SG ERB) of Utrecht University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ED: Conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, writing–original draft. FM and FK: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-review, and editing. TT, JH, and TR: Conceptualization, writing-review, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was funded by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University.

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all farm animal veterinarians who participated in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2023.1163062/full#supplementary-material

Batchelor C., Mckeegan D. (2012). Survey of the frequency and perceived stressfulness of ethical dilemmas encountered in UK veterinary practice. Veterinary Rec. 170, 19. doi: 10.1136/vr.100262

Deelen E., Meijboom F. L., Tobias T. J., Koster F., Hesselink J., Rodenburg T. B. (2022). The views of farm animal veterinarians about their roles and responsibilities associated with on-farm end-of-life situations. Front. Anim. Sci. 3. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2022.949080

Dürnberger C. (2020). Am I actually a veterinarian or an economist? understanding the moral challenges for farm veterinarians in Germany on the basis of a qualitative online survey. Res. Veterinary Sci. 133, 246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.029

Harrits G. S., Møller M.Ø (2021). Qualitative vignette experiments: a mixed methods design. J. Mixed Methods Res. 15, 526–545. doi: 10.1177/1558689820977607

Hartnack S., Springer S., Pittavino M., Grimm H. (2016). Attitudes of Austrian veterinarians towards euthanasia in small animal practice: impacts of age and gender on views on euthanasia. BMC Veterinary Res. 12, 26–20. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0649-0

Herfen K., Kunzmann P., Palm J., Ratsch H. (2018). Entscheidungshilfe zur euthanasie von Klein-und heimtieren. Kleintier Konkret 21, 35–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120777

Hughes R., Huby M. (2002). The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. J. Adv Nurs. 37, 382–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02100.x

Hughes R., Huby M. (2004). The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Soc. Work Soc. Sci. Rev. 11, 36–51. doi: 10.1921/17466105.11.1.36

Kipperman B., Morris P., Rollin B. (2018). Ethical dilemmas encountered by small animal veterinarians: characterisation, responses, consequences and beliefs regarding euthanasia. Veterinary Rec. 182, 548. doi: 10.1136/vr.104619

Kondrup S. V., Anhøj K. P., Rødsgaard-Rosenbeck C., Lund T. B., Nissen M. H., Sandøe P. (2016). Veterinarian’s dilemma: a study of how Danish small animal practitioners handle financially limited clients. Veterinary Rec. 179, 596. doi: 10.1136/vr.103725

Main D. C. (2006). Offering the best to patients: ethical issues associated with the provision of veterinary services. Veterinary Rec. 158, 62–66. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.2.62

Martin F., Taunton A. (2006). Perceived importance and integration of the human-animal bond in private veterinary practice. J. Am. Veterinary Med. Assoc. 228, 522–527. doi: 10.2460/javma.228.4.522

Matte A. R., Khosa D. K., Coe J. B., Meehan M. P. (2019). Impacts of the process and decision-making around companion animal euthanasia on veterinary wellbeing. Veterinary Rec. 185, 480. doi: 10.1136/vr.105540

Morgan Carol A. (2007). Ethical dilemmas in veterinary medicine. the veterinary clinics of north America. Small Anim. Pract. 37, 165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.008

Moses L., Malowney M. J., Wesley Boyd J. (2018). Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: a survey of north American veterinarians. J. Veterinary Internal Med. 32, 2115–2122. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15315

Polkinghorne D. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 137–145. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

Rollin B. E. (2011). Euthanasia, moral stress, and chronic illness in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Clinics: Small Anim. Pract. 41, 651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.03.005

Rollin B. E. (2006). An Introduction to Veterinary Medical Ethics. Theory and Cases. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA .

Royal Netherlands Veterinary Association (2022) Code voor de dierenarts. Available at: https://www.knmvd.nl/code-voor-dierenarts/.

Shaw J. R., Lagoni L. (2007). End-of-life communication in veterinary medicine: delivering bad news and euthanasia decision making. Veterinary Clinics: Small Anim. Pract. 37, 95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.010

Springer S., Sandøe P., Bøker Lund T., Grimm H. (2019). Patients’ interests first, but…”–Austrian veterinarians’ attitudes to moral challenges in modern small animal practice. Animals 9, 241. doi: 10.3390/ani9050241

Keywords: euthanasia, farm animal practice, moral stress, veterinary medical ethics, qualitative research

Citation: Deelen E, Meijboom FLB, Tobias TJ, Koster F, Hesselink JW and Rodenburg TB (2023) Considering life and death: a qualitative vignette study among farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands on considerations in end-of-life decision-making. Front. Anim. Sci. 4:1163062. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2023.1163062

Received: 10 February 2023; Accepted: 06 April 2023;

Published: 24 April 2023.

Edited by:

Lodi Laméris, Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Elein Hernandez, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, MéxicoCopyright © 2023 Deelen, Meijboom, Tobias, Koster, Hesselink and Rodenburg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ellen Deelen, ZS5kZWVsZW5AdXUubmw=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.