95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anim. Sci. , 19 May 2022

Sec. Animal Welfare and Policy

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2022.893772

As the world's largest livestock producer, China has made some progress to improve farm animal welfare in recent years. Recognizing the importance of locally led initiatives, this study aimed to engage the knowledge and perspectives of Chinese leaders in order to identify opportunities to further improve farm animal welfare in China. A team of Chinese field researchers engaged 100 senior stakeholders in the agriculture sector (livestock business leaders, agriculture strategists and intellectuals, government representatives, licensed veterinarians, agriculture lawyers, and national animal welfare advocates). Participants completed a Chinese questionnaire hosted on a national platform. The raw data responses were then translated and subjected to qualitative and quantitative analyses from which themes were built and resulting recommendations were made. The findings of this study urge emphasis on the ties between improved animal welfare with food safety, product quality, and profit, and demonstrate the existence of animal welfare opportunities outside of the immediate introduction of specific animal protection legislation. The resulting applications are anticipated to be of strategic use to stakeholders interested in improving farm animal welfare in China.

“Promoting animal welfare has become not only an important choice for the green development of agriculture and a significant measure to ensure food safety and healthy consumption, but even more so an important embodiment of human caring in modern society”

- Vice Agriculture Minister Yu Kangzhen (Guoqing China, 2019).

China is the largest livestock producing nation in the world (FAOSTAT, 2017) and therefore is the custodian of significant challenges for farm animal welfare. There are many reasons to be optimistic about the progression of animal welfare in China. In fact, a shift is already indicated. Apart from government endorsements, such as that made by Vice Minister Yu, there is evidence of increasing public interest, active livestock industry engagements, and academic research to improve farm animal welfare.

Chinese citizens have expressed increasing regard for the way animals are treated (Lu et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2016; Sinclair and Phillips, 2017; Jun, 2018; Zhang, 2018), and while interest in the welfare of farm animals is currently low, it is growing (Nielsen and Zhao, 2012). This can be, in part, attributed to factors including increased pet ownership, urbanization, media coverage (D'Silva and Turner, 2012; Carpenter and Song, 2016), and concerns for food safety and public disease (Littlefair, 2006). Although there is room for improvement in the current treatment of animals throughout society, the concept of “animal welfare” aligns with some core traditional Chinese values found in Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, which promote compassion toward non-human animals (Cao, 2020; Li, 2021a). The term “animal welfare” (动物福利 [sic]) itself was translated into Chinese in the 1990s (Bao and Li, 2016), and Shi, the Party Secretary of the National Animal Husbandry Bureau, suggests that the term ‘animal welfare' became more familiar as a concept among the public, livestock industry, and the government in the 2000s (Shi, 2020). The term “animal welfare” may be more readily understood in China as a scientific concept (Sinclair and Phillips, 2019), and can be measured using indicators such as behavior, disease and immunosuppression, body damage, growth and reproductive rates, hormonal measurements, responsiveness, preferences, and the development of stereotypies (abnormal repetitive behaviors) (Broom, 1991). A survey of urban Chinese consumers in 2014 found that although two-thirds of participants had not heard the term “animal welfare,” 73% believed that it was tied to food safety (You et al., 2014). Chinese consumers have even expressed some willingness to pay for higher welfare products (Ortega et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2018).

China has made commitments to make farm animal welfare improvements (FAO, 2017), and efforts for positive change are evident within the livestock industry. For example, non-governmental organizations, such as the International Collaboration Committee of Animal Welfare (Beijing) and Compassion in World Farming (London), collaborated with Chinese companies to award layer, broiler, and pig producers who have met their animal welfare standards. To date, more than 100 producers have received these awards (Compassion in World Farming, 2020). Leading agricultural companies, such as Da Bei Nong (Group), have also worked with World Animal Protection to collaboratively set up model pig farms (World Animal Protection, 2017). Some major companies have even proactively created voluntary animal welfare standards, such as Mengniu Dairy Company Ltd (China's second largest dairy company), establishing China's first dairy welfare standards (Xinhuanet, 2020). Similarly, in a separate study, leaders in Chinese livestock industries stated that they personally considered animal welfare important (Sinclair et al., 2017), and, in another, Chinese livestock leaders themselves presented researchers with a multitude of potential benefits in addressing animal welfare (Sinclair et al., 2019).

To build animal welfare capacity in China, a positive approach would focus on potential opportunities. Investigating the wealth of knowledge and expertise available from local experts who are also best positioned to enact meaningful change could advise the most effective path forward.

Building upon existing research, the aim of the current study was to draw on the experience of senior stakeholders in the Chinese agricultural sector to identify potential opportunities for farm animal welfare improvements. The purpose of this study was to provide relevant guidance for domestic industry and policy and to identify and develop effective strategic applications and recommendations for international support and collaboration.

This research was granted ethics approval by the University of Queensland, Australia (2020/HE002934). Data collection was conducted between March and July 2021. Due to COVID-19 and the accompanying travel restrictions, health considerations, and additional strain placed on all industries during the period in which the research was conducted, we used online questionnaires as this involved the least demand, risk, and inconvenience for participants.

This study used purposive convenience sampling through a snowball sampling technique to recruit participants (Christopoulos, 2009; Andrade, 2020). The online questionnaire was made on a Chinese survey platform (Wen Juan Xing 问卷星) for ease of access in China. The questionnaire was publicly available and shared to individuals and groups via a QR code and a HTML link by the research team on WeChat. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire voluntarily and were encouraged to share the links with their acquaintances. There may be potential bias in the sample obtained due to the sampling method. Participants may be more likely to participate if they have stronger personal or professional relationships with members of the research team. This sample may not be representative of all senior stakeholders in China.

Participants in this study consisted of 100 senior stakeholders associated with the animal agriculture sector in China. Participant selection was based on fulfilling one of the following roles within the animal agricultural sector in China:

• Government and policy representatives.

• Agricultural lawyers.

• Livestock business and association leaders.

• Agricultural strategists and intellectuals (including academics).

• Licensed agriculture veterinarians.

• Active animal advocates.

In addition to being actively engaged in the Chinese animal agriculture sector, each senior stakeholder was considered influential by their colleagues; that being, they were considered to be decision makers or those who influence decisions within the landscape, in a position to influence change on the ground (i.e., livestock leaders), or in a position to change strategic direction (policy, strategy, intellectual advice). Stakeholders were approached to be participants in this study by direct contact from the Chinese-speaking data collection team (all co-authors). In some instances, this involved liaison with “gatekeepers,” and recommendations were accepted by participants with regards to other leaders they considered knowledgeable and influential, but only where contacts were volunteered.

Within this research, participants completed online questionnaires to generate quantitative data using 5-point Likert scale questions and qualitative data using open-ended responses. The research items in this study were refined in consultation with academics specializing in the region (all co-authors), and data were collected in Chinese, coordinated by a Chinese team leader (second author), and operated from a virtual Chinese platform. After being directly or indirectly identified, participants were then invited through local research collaborators (all co-authors). Participants were provided the study information and were requested to confidentially participate by providing 15–20 min of their time to offer their expert insight into the status of animal welfare in China. If they agreed to participate, they were provided a link through which they could access the research questions and input their responses anonymously. Quantitative surveys alone cannot fully uncover participants' sentiments (Weary et al., 2015) or provide a “deeper” understanding of social phenomena (Gill et al., 2008). For this reason, a mixed methodology approach was adopted in this study, with primary emphasis on qualitative items. The research items, as they appeared in Chinese, can be found at the end of this manuscript. Responses were back translated by a bilingual co-author to English for analysis by the lead author. The following statement was adapted from the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and presented at the onset of the questionnaire:

“The welfare of animals within this research refers to how well an animal is coping with the conditions in which it lives. An animal has good welfare if its needs are being met and hence it is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, able to express important behavior, and not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear, and distress.”

“动物福利” 在此问卷中定义为动物对其生活环境的适应程度. 如果动物健康、感觉舒适、营养充足、安全、能够自由表达天性并且不受痛苦、恐惧和焦虑的折磨压力威胁,则满足动物福利的要求.” [sic]

The research questions addressed in this manuscript include the following:

(i) Where does “animal welfare” fit amongst the “most important” agricultural considerations for key Chinese stakeholders?

(ii) What would encourage Chinese animal industries to pay attention to animal welfare?

(iii) What do key Chinese stakeholders see as the opportunities to progress animal welfare in China?

(iv) What Support is required to progress animal welfare, according to key Chinese stakeholders?

The specific research items in this manuscript include questions 1–5 and 9–15 (see Supplementary Material I). Further items in the questionnaire will be presented in companion manuscripts.

The raw data were compiled, coded, and cleansed (checked for repeated or incomplete entries and organized). All responses were translated by a fluent bilingual co-author and subjected to back translation in order to confirm accuracy. Any items of which meaning was unclear were discussed. Binary and numerical quantitative data were summarized, and qualitative data were subjected to thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, 2014) by the lead author using software packages Nvivo (QSR International, 2018) and Microsoft Office, where themes and subthemes were coded and described. If responses were unclear or irrelevant, they were omitted. Data within each theme were then subjected to further analysis to create sub-themes according to their perceived intent, organized, and quantified to understand the frequency and, therefore, importance of theme and subtheme according to the participants. In summary, frequently occurring general sentiments were considered “themes,” and frequently occurring sentiments that could be considered to further illustrate a pre-existing theme either explicitly (by respondents) or logically (to the lead author) were considered as “sub-themes.” Figures and models were developed and presented within results to further illustrate relationships between themes and enable the findings to be readily applied to domestic Chinese animal welfare strategy and collaborative international strategy.

One hundred senior stakeholders participated in this study. The production sectors of which the stakeholders were experienced are presented in Table 1. The role and experience in years of each participant are presented in Table 2.

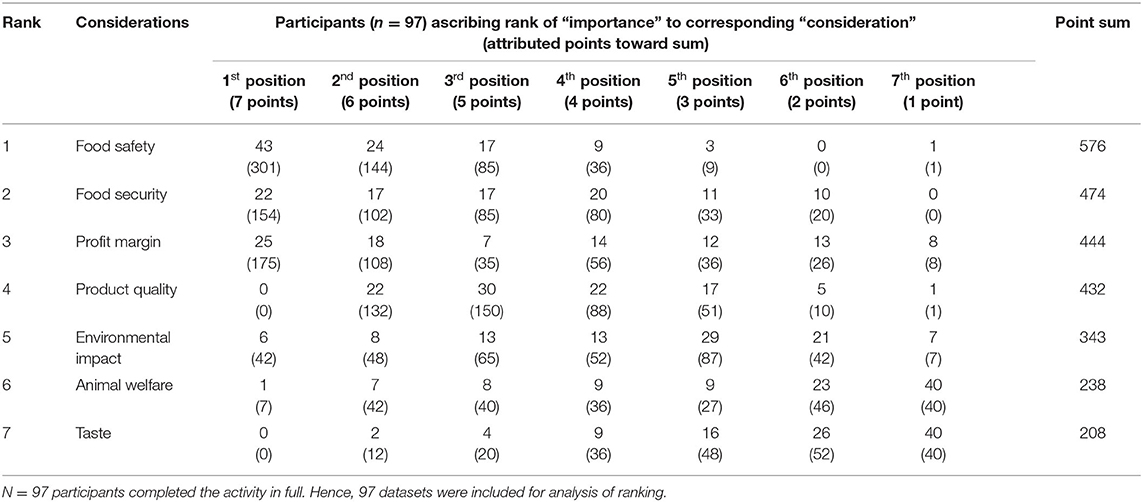

Identifying what might be considered important to a target audience can not only serve to better understand a stakeholder group and how to engage them, but it can further illuminate potential mutual benefits for cooperative progression (Sinclair and Phillips, 2018). Participants were asked to participate in an activity of ranking agricultural considerations in order of importance. These considerations included animal welfare, environmental impact, food safety, food security, taste, product quality, and profit margin (动物福利、环境影响、食品安全、粮食保障、味道、产品质量和利润率) [sic]. “Food safety” was considered the most important, followed by “food security” (Table 3). “Animal welfare” and “taste” were ascribed the least importance of those assessed.

Table 3. Participants' (n = 97) responses when asked to ascribe a rank of “importance” to agricultural considerations.

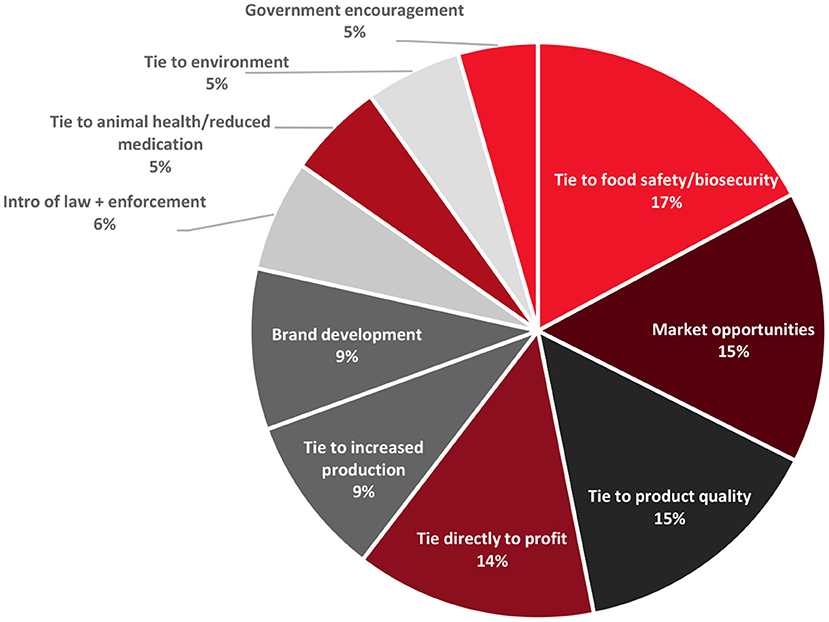

In their responses to the question “what would encourage animal industries to pay attention to animal welfare?”, participants (n = 100) offered 130 responses. Over half (59.2%) of the participants suggested that animal welfare should be tied to other more compelling causes and benefits (Figure 1). Within that, and in order of citation frequency, participants suggested to tie animal welfare to (i) “increased market and brand opportunities” (theme, n = 31), such as offering more demand and willingness to pay for higher welfare products (sub-theme, n = 17) and opportunity for publicity (sub-theme, n = 10); (ii) “food safety and biosecurity” (theme, n = 19); (iii) “increased quality of products” (theme, n = 16); (iv) “profit” (theme, n = 15), (v) “increased production performance” (theme, n = 10); (vi) “animal health and reduced medicinal treatments” (theme, n = 6); and (vii) “environmental pollution and management” (theme, n = 6). Participants also cited societal developments that would encourage attention to animal welfare (theme, n = 22), including (i) “the introduction and strict enforcement of laws” (sub-theme, n = 7), (ii) “Chinese government encouragement” (sub-theme, n = 5), and (iii) “the introduction of standards and policy” (sub-theme, n = 4). As one agricultural veterinarian shared, “Farm animal welfare will gain attention when it can be proven to bring benefits to the farm” (agricultural veterinarian working across dairy, cattle, pig, and sheep industries with under 5 years industry exposure).

Figure 1. Pie chart comparatively displaying the 10 most frequently identified elements to attract attention to animal welfare within agriculture.

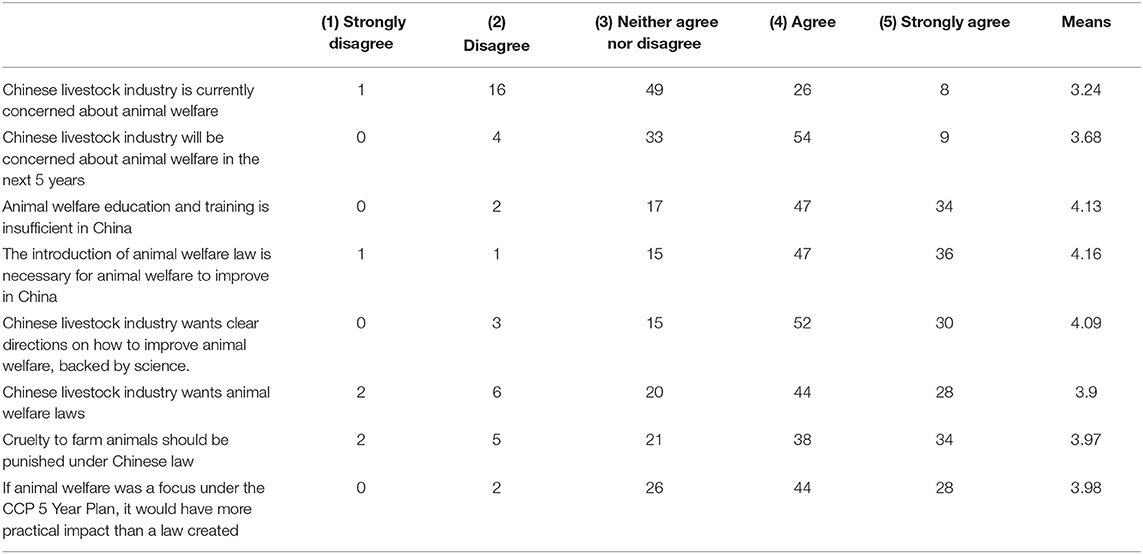

When attributing a level of agreement or disagreement to statements made about animal welfare in general, including the role of law, standards, and the “Five-Year Plan,” participants remained neutral in most part, with only slight agreement in some instances (Table 4). Participants were mostly neutral that the Chinese livestock industry is currently concerned about animal welfare and mostly agreed that the same industry would be concerned in the next 5 years. Participants most commonly agreed that animal welfare education and training is insufficient in China, that the introduction of animal welfare law is necessary, and that the Chinese livestock industry wants clear directions on how to improve animal welfare that are supported by science (Table 4). Participants also tended to lean toward agreement that cruelty to farm animals should be punished under Chinese law and that, if animal welfare was a focus of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) “Five-Year Plan,” it would have more practical impact than a law created.

Table 4. Participants' (n = 100) responses to the item “please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements” on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) by distribution and means.

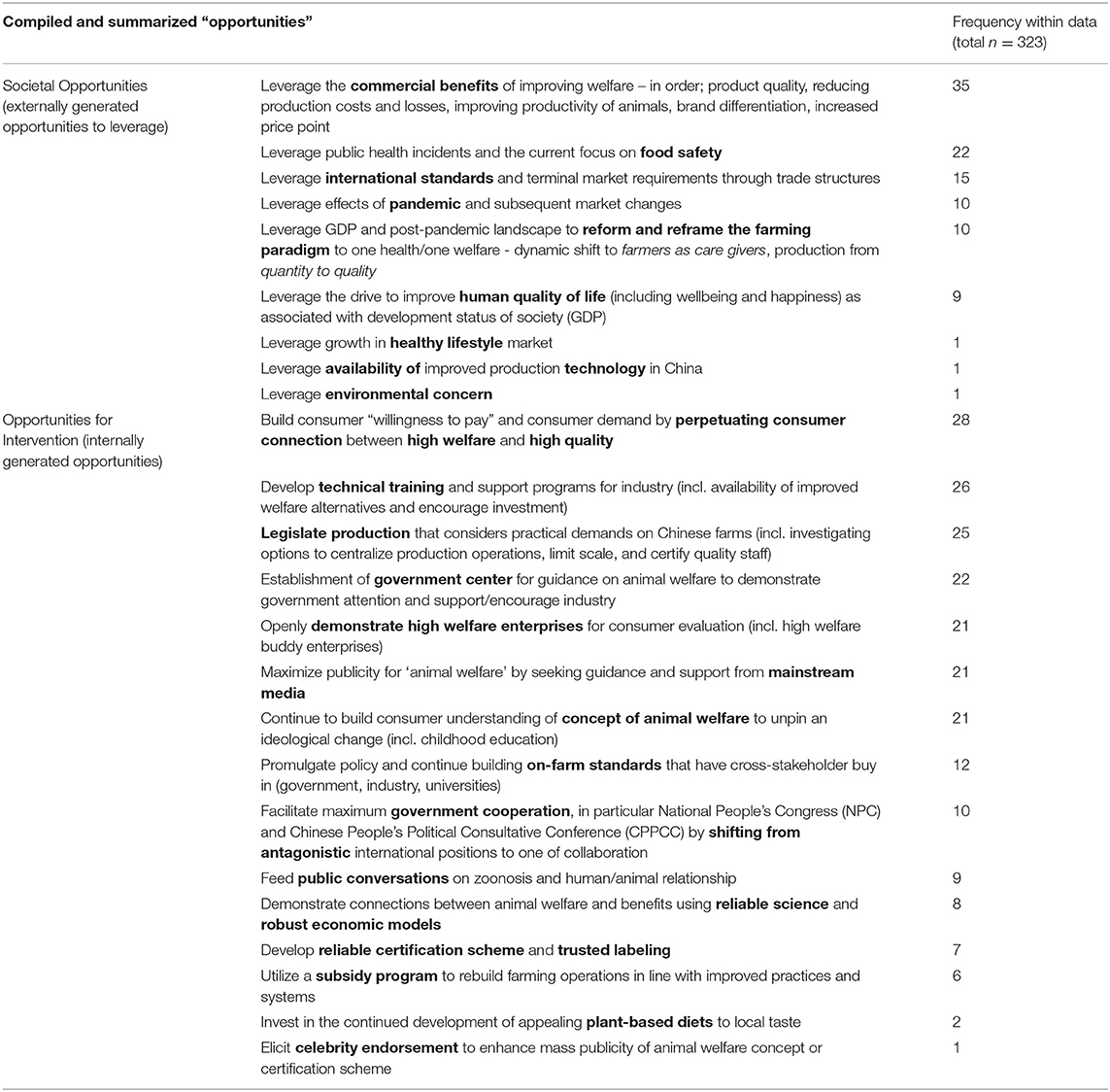

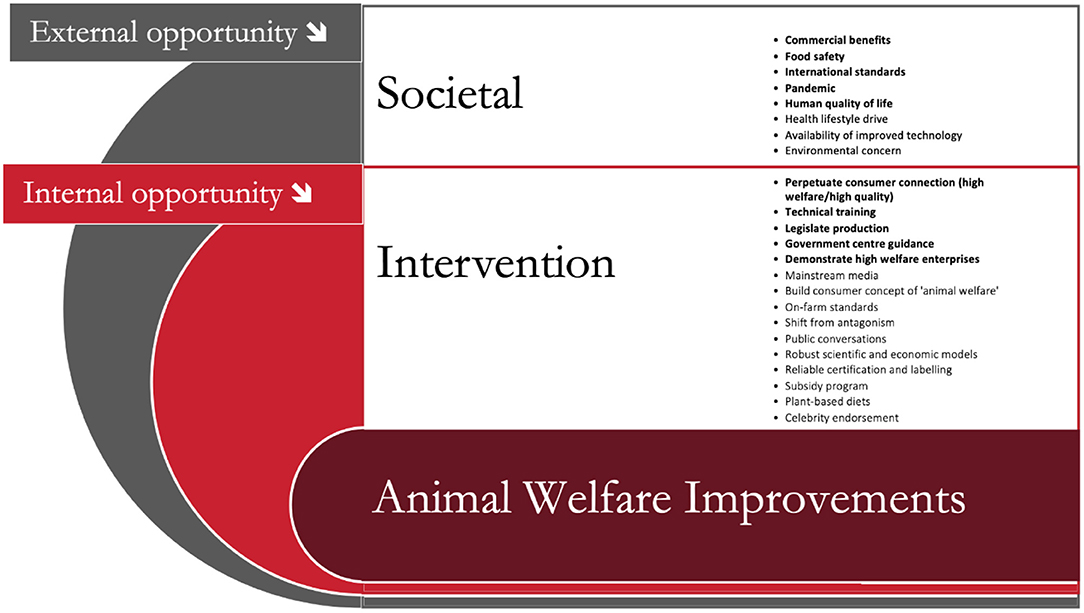

In response to the question “what do you see as the major opportunities for improving farm animal welfare in China?” (‘您认为在中国提升农场动物福利的契机或突破点是什么?') [sic], participants presented a total of 323 opportunities. The themes that were developed from these data are presented in Table 5. Within their responses, participants appeared to interpret the question in different ways. We classified the responses into two broad categories (themes): “societal opportunities” (external), and “opportunities for intervention” (internal). “Societal opportunities” consist of opportunities (sub-themes) based on existent realities and conditions outside of the immediate control (external locus of control) that could be leveraged. For example, one participant response includes the quote “Zoonosis stimulates the society to pay attention to the relationship between human and animals, which creates a favorable platform for public conversations on improving farm animal welfare (‘人畜共患疾病带来的全社会对人与动物关系的关注,为提升农场动物福利带来了有利的社会舆论环境')” [sic]. On the other hand, “opportunities for intervention” consist of internally-generated interventions or initiatives (sub-themes) that could maximize animal welfare progress under the current societal context (internal locus of control). For example, one participant's response includes the quote “large enterprises take the lead, and small and medium-sized enterprises with special characteristics actively participate in the recognition and purchase of welfare products […] and establish a sound and reliable reputation evaluation system (大企业带头,特色中小企业积极参与福利产品的认可与采购. 并建立完善可靠的评估信誉体)” [sic]. Another stated “at present, Chinese consumers' understanding and attention to farm animals and their welfare issues are not high, so it is difficult to resonate. Therefore, long-term effective communication and education should be prioritized (目前中国消费者对农场动物及其福利议题了解和关注度整体不高,难以产生共鸣. 因为长期有效的传播、教育应该基于充分的重视)” [sic].

Table 5. Summary of “opportunities” (n = 323) based on participants' responses and the frequency with which each opportunity appeared in the data.

Born in human cognitive and behavioral psychology, ‘locus of control' refers to the degree in which an individual perceives outcomes as being contingent on their own actions (Rotter, 1966) or is controllable and able to be influenced. An internal locus of control orientation is a belief that our actions are contingent on what we do, as opposed to external control orientation, in that the events and conditions are outside our personal control (Zimbardo and Ruch, 1975). Here, this refers specifically to the perceivable control that stakeholders have should they be interested in improving animal welfare. Figure 2 presents this visually and further demonstrates the relationship between the societal opportunities to leverage (external conditions leveraged) and opportunities for interventions (internally driven initiatives based on the societal conditions).

Figure 2. Graphic representation of the relationship between themes of societal context (external opportunity) and interventions (internal opportunities) to improve animal welfare in China based on the findings presented in Table 5 above. The five most frequently supported internal and external ‘opportunities' within the raw data are indicated in bold.

Of those directly involved in the management of a livestock business (n = 33), 97% (n = 32) stated that they would make respective changes to their operations if animal welfare could be demonstrated to improve profit. When asked what evidence they considered to be most convincing, the responses could be categorized as either demonstrating viable return on investment or experiencing tangible results first-hand. Demonstrating viable return on investment (theme) included the following sub-themes: (i) presentation of reliable scientific evidence (i.e., how animal welfare improves health, and lowers mortality), (ii) model enterprises demonstrating, leading, and driving changes, (iii) presentation of solid economic data (i.e., proof of return on investment), or (iv) product price in market increases (and is without fluctuation). For example, one participant response includes the quote (I'd require) “proof from scientific evidence, such as how animal welfare improves health, lowers mortality, improves pay, and my standards, etc. 有科学论证的事例,比如说动物福利提高健康,降低死亡率,提高薪水和水平等等” [sic]. Another stated (I'd) “(demonstrate that it is possible to be) gaining power of setting the price for our own products, without complying to fluctuations with the market price, which would guarantee profit 自己有产品的定价权,不随市场价格产品波动,利润有保障” [sic]. Experiencing tangible results first-hand (theme) included the following sub-themes: (i) increased product quality, (ii) increased productivity of animals, or (iii) increase in profits directly. For example, one participant response includes the quote “after animal welfare improvement, we'd like to see growth performance and profit margin increase, or remain unchanged 提高动物福利后,生长性能和利润率得到增加,或维持不变.” [sic].

Food safety is a powerful and recurring theme in this study, deemed the most effective way to attract attention to animal welfare in China (Figure 1) and a significant opportunity to drive animal welfare improvements (Table 5). One participant stated that “consumers are becoming more aware of their health, which stimulates enterprises to improve food safety measures, which in turn also encourages animal welfare reforms in animal agriculture. 消费者健康意识提升,促进企业食品安全改进,又鞭策了养殖业的动物福利改革” [sic].

Eighty-three percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the introduction of animal legislation is necessary for animal welfare to improve in China, with 72% agreeing or strongly agreeing that the livestock industry also wants animal welfare legislation and that cruelty to farm animals should be punished under that legislation (Table 4). What this does not share, however, is what role participants expect legislation to play and what context they perceive when they say that legislation is needed; specifically, what they hoped will be gained by introduction of animal legislation. Although undeniably powerful once introduced, these findings also do not consider the difficulty in introducing law or the ability to implement, monitor, and effectively enforce a new law. Considering introducing new focused legislation as a viable path to wholescale animal welfare improvement would also entail national investment into large scale implementation, monitoring, and enforcement structures, reducing the likelihood of ready uptake. “Legislating production” (n = 25) was a significant “opportunity for intervention” amongst the opportunities to improve animal welfare (n = 323) shared by participants (n = 100). However, other opportunities were cited more frequently, such as commercial benefits.

Following on from this, 82% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the Chinese livestock industry wants clear, scientifically supported directions on how to improve animal welfare (Table 4). Of those directly involved in the management of a livestock business (n = 33), 54.5% stated that they were familiar with the 2018 “Farm Animal Welfare Requirements” drafted by the China Association for Standardization (n = 18). The same participants also stated they had made changes in their organization to improve animal welfare. When asked about the nature of the changes they made, responses were varied. The only change that was reported by more than one participant was to “make improvement to the documentation requirements” (n = 4; pig, layer hen, dairy cattle, and sheep producers). Others included “improve farm environment, provide bedding, reduce stocking density, group housing, remove tail docking practices” (pig producer), “elimination of gestation crates/sow stalls, stopped docking tails, kept sows in groups, and provided bedding” (pig producer), “lower stocking density” (broiler producer), “increase free-range area on pig farm, improve comfort of bedding for dairy cows” (pig producer), and move to “non-caged, multi-tier barn system” (egg producer). One participant stated that “combined with the current European and American animal welfare programs, as well as China's relevant requirements, we established key points for the company to pay attention to and implement internally and with our partners 结合目前欧美的动物福利方案,以及中国相关的要求,建立公司内部与合作伙伴需要关注并执行的要点” [sic] (dairy cattle, beef cattle, pig, sheep, and layer hen and broiler producer).

Of those directly involved in the management of a livestock business (n = 33), 48.5% had international trade partners with animal welfare requirements (n = 16). When asked how these requirements were enforced and monitored, approximately a third of these participants (n = 5) stated “no effective measures.” When asked how these changes were enforced and monitored, however, the responses were diverse. They included “active participation in discussions and formulation of relevant policies,” “quality assurance,” “third party supervision,” “standard operating procedures,” “periodic inspection report,” “self-managed standards and records to ensure compliance,” “set reward and punishment measures,” and “slow implementation.”

This study found that, of those involved directly in the management of a livestock business (n = 33), 79% stated they had noticed a difference in consumer behavior as a result of COVID-19 and African Swine Fever (n = 26). A total of 34 responses were received when participants were asked to share the ways in which they believed that consumer behavior had changed (Table 6), and most of which pertained to perceptions of a changed consumer psychology (n = 26), predominantly increased discernment around food safety (41%), and evolving societal awareness and expectation (26%). The COVID-19 pandemic also featured in responses from participants as an external opportunity for the progression of animal welfare (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 6. Themes derived from participants responses (n = 34) to the item “in what way has consumer behavior changed in response to COVID-19?” by frequency with which the identified theme was reflected in the data, and the percentage of overall responses in the data.

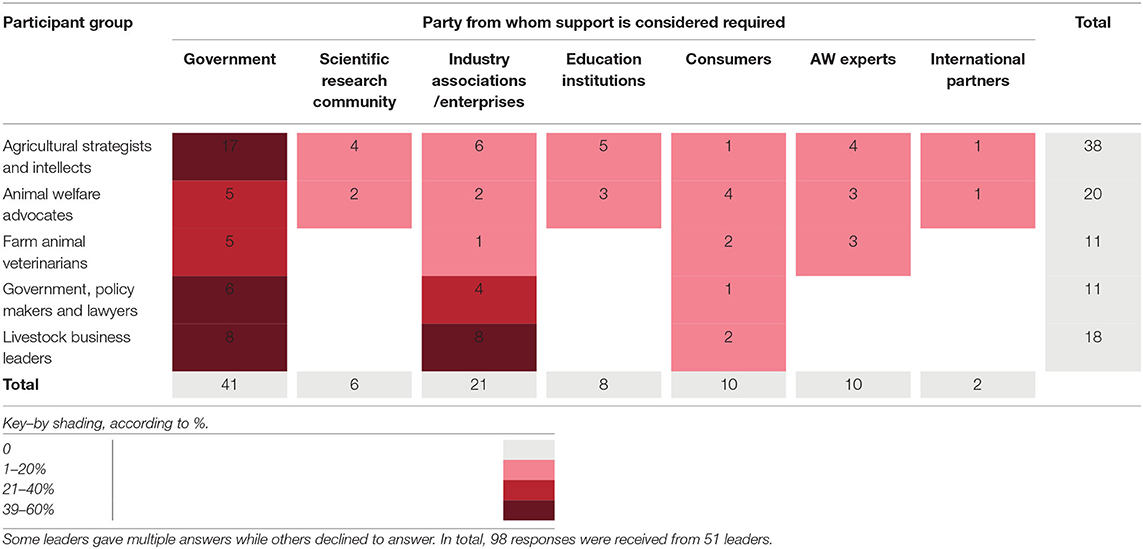

When asked if they believed the livestock industry in China needed more support to improve animal welfare, 88% of participants agreed. When asked who the support was needed from, ‘the government' was the most frequent response. Interestingly, participants were likely to identify the agricultural sector that they come from as responsible parties (Table 7). For instance, participants from the government commonly identified government as the party from whom support is needed. Similarly, business leaders identified their own group (the livestock industry). This may represent a reduced tendency to “shift accountability,” a potential to accept accountability to some degree, and a willingness to engage in support for improved animal welfare where the support is understood and deemed possible. It could also be a product of being self-focused and offering a path forward that is in context of what they know, all of which presents opportunities or, importantly, that the nature of “leader” as identified in this study has a tendency for responsibility.

Table 7. Participant response to ‘who' is needed to provide support to the agricultural sector in order to improve animal welfare in China by participant group.

When asked about the nature of support that is needed, some participants shared the need for training, stating that “training needs to be supported by animal welfare institutions and authoritative educational institutions.” Another stated “(we need) training within the industry and development of scientific researchers” and a third stated “(we need) technical guidance; enterprises can cooperate with universities, or the government can provide it. We need scientific research community to provide research findings; we need government support for animal welfare policies; We need schools and media to publicize and educate animal welfare.”

On demonstration and modeling, a participant stated “create demonstration sites, utilizing the success of one/several farms to lead changes across the sector.” Another stated “Demonstration from high welfare enterprises; Support for high welfare enterprises; Official recognition of welfare production practices.”

Highlighting the importance of strategic support, one stated that “we (also) need technological support of farm animal welfare production and strategies to promote animal welfare food products.”

A participant from government stated that support needed comprises of “government guidance, enterprise leadership and public participation.”

The findings of this study suggest there are a plethora of existing opportunities to progress animal welfare in China that are known to the experts likely to lead developments. Considering attracting attention to animal welfare (Attracting attention to animal welfare in China), the findings echo previous research in the region that presents that attempting to draw attention to animal welfare for the sake of the animals is unlikely to yield meaningful engagement with key decision-making stakeholders (Sinclair et al., 2019). Drawing attention to “more compelling benefits,” such as demonstrable impact to profit, on the other hand, holds the potential to attract vastly more attention.

The frequency with which participants make statements that emphasize profit or profit-related factors throughout this study, suggests its paramount importance to leaders within China's livestock industry. Furthermore, such profit-related statements were presented by participants from all roles, not limited to those that directly profit from animal agriculture. Given that livestock enterprises are commercial endeavors and that domestic profits also benefit government and civilian interests by raising national GDP, this result is considered expected and indeed echoed by previous findings in the region in which profit is a significant driver of change (Sinclair et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021) as it is elsewhere in the world (Dawkins, 2017; Ventin, 2020). Demonstrating any profit potential effectively is integral (see animal welfare intersection 1 below for ways in which animal welfare could be tied to profit). In addition to reducing production costs and mitigating losses, increasing the market and consumer demand is a key way to deliver increased profits in higher welfare models. The findings of this research suggest that this could be based on facilitating a consumer shift (complementary with growing societal affluence) from product quantity to quality in such a way that improved animal welfare delivers higher quality products (see animal welfare intersection 2 below for ways in which animal welfare could be tied to product quality).

Food safety is already a well-communicated and legislated priority amongst Chinese leadership, with serious repercussions to industry if they fall short of requirements. Through investing heavily in resources and skills, the Chinese government has prioritized advancing the domestic food system to provide national food security (Zhou, 2010) and to continue building the nation into the only trillion-dollar economy with a positive GDP growth rate [International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2020; The World Bank, 2021]. China experienced severe food safety scandals in the mid 2000s, such as the 2008 incident where toxic chemical melamine was added to milk, which led to expedited and comprehensive reform of the national food safety regime (Pei et al., 2011). Food safety has firmly remained on the national agenda since, setting a shift from focusing on the quantity of food production (an issue largely addressed in China) to the quality of food. Leveraging the ways in which food safety and biosecurity can be tied to animal welfare represents a major opportunity for immediate application. High animal welfare products have the potential, in China, to state a level of product safety (See animal welfare intersection 1 below for ways in which animal welfare can be tied to food safety) (Yang, 2020). This is the case not just in regard to framing and communication to build support for animal welfare but also in practical application. Existing laws can be leveraged and expanded, and certification frameworks and infrastructure could be extended (Li, 2021b). One example includes the current certification process required for animals entering slaughterhouses, accrediting that they are disease-free (General Administration of Quality Supervision, 2002; Ministry of Agriculture China, 2005). In addition to other trade transparency practices, such as confirming live animals have not been injected with water to falsely increase weight at sale, these established practices could be extended to incorporate reliable and trustworthy checkpoints for key welfare indicators.

Tied to both product quality and food safety is COVID-19. The still active pandemic of COVID-19 has caused great loss to China and international peers. Impacts to agriculture, including threatened production chains and agricultural employment, have been far reaching in China (Huang, 2020) and internationally (Siche, 2020). As is the case with Ebola, HIV, Avian Influenza, and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, meaning that it is likely to have originated back to a critical human-animal interface–the preparation and consumption of animals by humans (Magouras et al., 2020; United Nations Environment Programme, 2020). Consumer behavior demonstrated a drop of wild animal consumption from 27% during the SARS outbreak in 2003 to 17.8% during COVID-19 Hubei province, China (Liu et al., 2020). This shift has now been backed by a national ban on terrestrial wildlife consumption (Koh et al., 2021). On a larger scale, with repercussions beyond wildlife consumption and China, it has been reported that the food supply chain disruptions, media coverage of food safety issues, and restaurant closures associated with COVID-19 have all influenced consumer dietary behavior, resulting in reduced consumption of animal products (Attwood and Hajat, 2020) and an increase in plant-based diets (Loh et al., 2021). The findings in this study, coupled with these statistically reported trends, represent substantial opportunity to further underpin a consumer behavior shift from quantity to quality produce in animal industries, with improved animal welfare positioned and marketed alongside food safety as integral elements of quality.

Despite a proposed animal welfare law by Chinese scholars (Lu et al., 2013), at the time of writing, there is no focused animal welfare law and there is a lack of animal protection legislation in Mainland China (Li, 2021a). Although another study in the region also presented quantitative survey findings that suggested that legislation was a powerful motivator to improve animal welfare (Sinclair et al., 2017), a follow-up qualitative focus group study uncovered a more complex relationship with law (Sinclair et al., 2019). The focus group study found that the potential for profit was a stronger motivator than law to drive or inhibit animal welfare improvement in China. The findings of this study support that. Caution is also advised in using the presence of animal welfare legislation as the sole barometer for animal welfare progress across borders. For interested parties outside of China, it is important to be aware of one's own cultural lens. Sociopolitical and geographical contexts vastly shape constructs around law, the motivations to create it, how and what is influencing the introduction of laws, and its impact in different countries, different issues, and different solutions.

Once commercial benefit is understood and accepted, the creation of and training around prescriptive science-based standards would offer a clear usable path for industries to improve animal welfare. This process is underway. Commencing in 2014, official authorities of the China Association for Standardization have been meeting and publishing prescriptive documents on farm animal welfare requirements for select farmed species, including pigs, cattle, sheep, and laying hens (Yang, 2020; China Association for Standardisation, 2021).

With a majority of participants agreeing that the inclusion of animal welfare in the “Five-Year Plan” would be even more compelling than the introduction of new legislation, it is clear that this is an important policy in China. With a series of social and economic development focussing on the nation as a collective, the “Five-Year Plan” approach was introduced in 1953 by the Chinese Communist Party and remains a steadfast institution not dissimilar to a company strategic plan, with engagement and buy-in at all levels of Chinese society toward these collective tangible goals. As a powerful platform that successfully underpins the direction of attention, resources, and delivers large scale outcomes in China, with inclusion of animal welfare in future plans being reformative on a large scale. Moving an agenda into the Five-Year Plan, however, could prove to be more difficult than introducing laws. Therefore, while potentially resembling the most powerful opportunity for large scale reform, this opportunity requires further research as to the viability and appropriateness of advocating such an outcome. In the meantime, the current plan, the fourteenth, which commenced in 2021, includes focussed goals that could be tied to animal welfare in many ways. Specifically, this could include the current goals of “agricultural modernization,” “improvement of animal disease control,” “to address sustainability and adapt to climate change through improving agricultural practices,” and an “increase in smart farming” (e.g., use of technology, big data, block chain and AI) (Chinese Communist Party, 2021).

High quality education and training around the application of animal welfare for agriculture professionals is a critically important element to the larger picture. Government guidance is frequently sought, and the establishment of a government-based center to advise on standards and current international best practice is also indicated and likely to be powerful. Integral to the success of these initiatives is the foremost education of the educators, university staff and government representatives, in order to build the contingent of Chinese experts with whom industry can reliably consult. While hosting highest levels of education, these agricultural leaders may not yet have an appreciation or understanding around animal welfare. Once benefits are accepted and standards and training are available, the establishment of demonstration farms and pilot models could provide cornerstones to industry reform. In response to famine, Deng Xiaoping adopted a scientific, evidence-based pragmatic approach to improving agricultural output (Butt and Sajid, 2018). The national government encouraged pilot farms and regions to test improved practices, and when successful, encouraged implementation across regions (Butt and Sajid, 2018). Another example of this is the decollectivisation of agriculture from People's Communes to Household Responsibility System, where farmers became personally incentivised to produce more (Lin, 1988; Bai and Kung, 2014). With a shift from “more” to “better” and quantity to quality, this approach to model farms could again be utilized to test and demonstrate improved animal welfare practice while more widely building evidence and trust in the practices. During one on-farm ethnographic study in the China's dairy industry, workers, managers, and an executive shared with the researcher that they were highly receptive to evidence that improving animal welfare would increase profits and were willing to trial changes on a smaller scale in their own farms (Chen et al., 2021). Separate to state-owned units, private enterprises in China have been noted to be more eager to innovate to adapt and improve profit and may also be in a unique position to demonstrate these practices to industry peers and discerning consumers.

The findings in regards to how animal welfare requirements from trade partners are being enforced and monitored are diverse, indicating a lack of consistency across trade partners. This is possibly due to a variation in what is required across individual commercial partners. Therefore, the development of a consistent, clear, and prescriptive best practice approach to the implementation of improved welfare practices for trade partners in China could prove useful and meaningful.

Scientifically supported ways in which animal welfare is tied to profit:

• Increased yield and productivity of animals with high welfare (in some cases).

• Improved reproductive success.

• Reduced losses (mortality, reduced ability to thrive, costs of treating injury and illness, costs of mitigating brand scandal, or costs of losing markets that require higher standards).

• Increased access to export markets.

• Improved brand association with product quality.

(McInerney, 1993; Bennett, 1995; Bennett and Blaney, 2003; De Passillé and Rushen, 2005; Bennett et al., 2012; Green et al., 2012; Harley et al., 2012; Vetter et al., 2014; Grandin, 2015; Pinillos et al., 2016).

Scientifically supported ways in which animal welfare is tied to product quality:

• Improved attention to food safety and biosecurity.

• Reduced damage to carcass.

• Reduction in dark, firm, dry meat (DFD) resulting from pre-slaughter stress (beef).

• Reduction in pale, soft, and exudative meat (PSE) resulting from pre-slaughter stress (pork).

(De Passillé and Rushen, 2005; Adzitey and Nurul, 2011; Mateus et al., 2012; Schwartzkopf-Genswein et al., 2012; Shields and Greger, 2013; Faucitano, 2018; Grandin, 2020).

Scientifically supported the ways in which animal welfare is tied to food safety:

• Increased risks associated with unnatural concentrations of animals in close contact such as intensive farming operations.

• Increased risks of processing animals who are physiologically functioning below the optimum capacity due to stress or illness and therefore with impaired autoimmune system.

• Increased incidence of infectious disease on farms and increased shedding of human pathogens by farm animals with low welfare.

• Increased risk of antibiotic resistance from irresponsible usage (i.e., used as group prophylaxis).

[European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)., 2004; De Passillé and Rushen, 2005; Rostagno, 2009; Quammen, 2012; Diana et al., 2020; Schoenmakers, 2020; United Nations Environment Programme, 2020].

To avoid continuing with practices and initiatives that cause damage or, at best, do not maximally harness potential for success, new knowledge should be applied. The findings in this study can be applied to improve strategy aimed at supporting the progression of animal welfare in China.

In the absence of relevant farm animal welfare legislation in China and in addition to when/if legislation of this nature is introduced, below is a summary of recommendations to support the progression of animal welfare in China.

• Support consumer demand for product quality and willingness to pay (where household income allows), facilitating a shift away from focusing solely on quantity.

• Demonstrate the ways in which improved animal welfare can deliver commercial benefits, reduce costs, and increase profit (see intersection 1).

• Demonstrate the ways in which improving animal welfare can improve product quality (see intersection 2).

• Clearly communicate the ways in which food safety and quality intersects with animal welfare (see intersection 3).

• Build the capacity of Chinese animal welfare experts (educators, government representatives).

• Develop technical training programs for the industry.

• Demonstrate improved practices on industry model farms.

• Continue to build on prescriptive and scientifically supported industry standards.

• Build on existing quality assurance certification processes and leverage existing legislation and policy to creatively expand focus to animal welfare.

• Continued research of the complex landscape, including:

• International and intergovernmental agencies (e.g., OIE, WHO, UN, FAO) to positively encourage the Chinese government to lead animal agriculture to a higher level of welfare production.

• Exercise caution in using the presence of animal welfare legislation as the sole barometer for animal welfare progress across borders.

Now could be considered an important time for international collaboration with respect for mutual success and development. Animal welfare could be one of the platforms that demonstrates such an approach to the benefit of all countries and stakeholders. In the current study, we learnt from the knowledge and experience of 100 senior stakeholders in the agriculture sector in China to develop themes and build recommendations. The findings of this study reiterate that demonstrating mutual business benefits are needed, particularly in the absence of relevant legislation, to drive large-scale engagement with animal welfare. We presented many existing opportunities to support systemic animal welfare progression in China. Importantly, the findings suggest that animal welfare should be tied to improved food safety, food quality, and commercial benefits to improve farm animal welfare.

In a time in which it is all too easy to feel fatigued and hopeless, our findings urge optimism by presenting paths in which to view the current landscape as full of opportunity and hope. China is a powerful nation with unique capabilities and a long history of resilience and growth. Should the opportunities be harnessed, animal welfare could become one of the areas in which China leads the world. In addition, any growth could be underpinned by Chinese determination and global support.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MS conceptualized the study, sourced funding, recruited the research team, developed the research tool, analyzed the data, developed the models, and wrote the paper. As a research assistant to MS, HL significantly contributed to the development of the research tool, fulfilled the role of data collection team leader, organized, cleaned, and translated raw data, contributed to interpreting results, researched Chinese literature for inclusion, and contributed to writing the paper. Research team members MC, XL, JMi, and SC contributed to the development of the tool, collected data, contributed to interpreting results, and edited the paper. JMa contributed to writing the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or US Government determination or policy. The mention of any trade name, proprietary product, or specific equipment does not constitute a guarantee or warranty by USDA-ARS and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products that may also be suitable. The USDA-ARS is an equal opportunity and affirmative action employer. Lastly, all agency services are available without discrimination.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Harvard Law School Brooks McCormick Jnr Animal Law & Policy Program (ALPP) for hosting the lead author (MS) and this research project. The authors also thank Open Philanthropy (Amanda Hungerford and Lewis Bollard) for facilitating the funding provisions to support the project. The lead author also wishes to thank the team of ALPP Fellows (Fall 2021) and Harvard Law School staff, namely, Prof. Kristen Stilt, Christopher Green, Garet Lahvis, Larry Carbone, Martha Smith-Blackmore, Danielle Diamond, Jeff Skopek, Carolina Maciel, Carney Anne Nasser, Nirva Patel, M. H. Tse, and Jian Yi, who all contributed in valuable workshop discussions in the development of this manuscript, alongside Ceallaigh Reddy and Sarah Pickering, who also offered important guidance during this project.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2022.893772/full#supplementary-material

Adzitey, F., and Nurul, H. (2011). Pale soft exudative (PSE) and dark firm dry (DFD) meats: causes and measures to reduce these incidences-a mini review. Int. Food Res. J. 18, 11–20.

Andrade, C. (2020). The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 43, 86–88. doi: 10.1177/0253717620977000

Attwood, S., and Hajat, C. (2020). How will the COVID-19 pandemic shape the future of meat consumption? Public Health Nutr. 23, 3116–3120. doi: 10.1017/S136898002000316X

Bai, Y., and Kung, J. K. S. (2014). The shaping of an institutional choice: weather shocks, the Great Leap Famine, and agricultural decollectivization in China. Explor. Econ. Hist. 54, 1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.eeh.2014.06.001

Bao, J., and Li, Y. (2016). “China Perspective: Emerging Interest in Animal Behaviour and Welfare Science,” in Animals and Us, eds. J. Brown, Y. Seddon, and M. Appleby (Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers), 241–252.

Bennett, R. (1995). The value of farm animal welfare. J. Agric. Econ. 46, 46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-9552.1995.tb00751.x

Bennett, R., Kehlbacher, A., and Balcombe, K. (2012). A method for the economic valuation of animal welfare benefits using a single welfare score. Anim. Welfare 21, 125–130. doi: 10.7120/096272812X13345905674006

Bennett, R. M., and Blaney, R. J. (2003). Estimating the benefits of farm animal welfare legislation using the contingent valuation method. Agric. Econ. 29, 85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2003.tb00149.x

Broom, D. (1991). Animal welfare: concepts and measurement. J. Anim. Sci. 69, 4167–4175. doi: 10.2527/1991.69104167x

Butt, K. M., and Sajid, S. (2018). Chinese economy under Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. J. Polit. Stud. 25, 169–178.

Cao, D. (2020). Is the concept of animal welfare incompatible with Chinese culture? Soc. Anim. 1, 1–13. doi: 10.1163/15685306-12341610

Carpenter, A. F., and Song, W. (2016). Changing attitudes about the weak: social and legal conditions for animal protection in China. Crit. Asian Stud. 48, 380–399. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2016.1196891

Chen, M., Von Keyserlingk, M. A. G., Magliocco, S., and Weary, D. M. (2021). Employee management and animal care: a comparative ethnography of two large-scale dairy farms in China. Animals 11, 1260. doi: 10.3390/ani11051260

China Association for Standardisation. (2021). Standards of China Association T/CAS for Standardisation [Online]. International Cooperation Committee for Animal Welfare (ICCAW). Available online at: https://www.iccaw.org.cn/uploads/soft/180612/1-1P61216210.pdf (accessed, April 14 2022).

Chinese Communist Party. (2021). The Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China and the Outline of the Long-Term Goals for 2035. Beijing: Xinhua News Agency

Christopoulos, D. (2009). “Peer Esteem Snowballing: A methodology for expert surveys,” in Paper Presented at the Eurostat Conference for New Techniques and Technologies for Statistics. Conference on February 18, 2009 (Brussels, Belgium).

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2014). “Thematic analysis,” in Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, ed T. Teo (New York, USA; Springer), 1947–1952.

Compassion in World Farming. (2020). Egg Track Report. London, UK: Compassion in World Farming.Available online at: https://www.ciwf.com/media/7442448/2020-eggtrack-report-english.pdf (accessed, April 14 2022).

Dawkins, M. S. (2017). Animal welfare and efficient farming: is conflict inevitable? Anim. Prod. Sci. 57, 201–208. doi: 10.1071/AN15383

De Passillé, A. M., and Rushen, J. (2005). Food safety and environmental issues in animal welfare. Rev. Sci. Tech. 24, 757–766. doi: 10.20506/rst.24.2.1599

Deng, Q. F., Mao, H. X., Feng, Z. M., Gao, F. X., and Yin, Y. L. (2016). 我国农场动物福利的研究现况与展望 (Status quo and prospect of farm animal welfare in China) Acta Ecologiae Animalis Domastici, 37, 610.

Diana, A., Lorenzi, V., Penasa, M., Magni, E., Alborali, G., Bertocchi, L., et al. (2020). Effect of welfare standards and biosecurity practices on antimicrobial use in beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 10, 20939. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77838-w

D'Silva, J., and Turner, J. (2012). Animals, Ethics and Trade: The Challenge of Animal Sentience. London, UK: Routledge

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). (2004). Scientific report of the scientific panel for animal health and welfare on a request from the commission related to welfare of animals during transport. EFSA J. 44, 1–36. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2004.44

FAO. (2017). Strong Commitment Towards Higher Animal Welfare in China. FAO.Available online at: http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/home/en/news_archive/Strong_commitment_towards_higher_aw_China.html (accessed December 1, 2018).

FAOSTAT. (2017). Data: China. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online at://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed, April 14, 2022)

Faucitano, L. (2018). Preslaughter handling practices and their effects on animal welfare and pork quality. J. Anim. Sci. 96, 728–738. doi: 10.1093/jas/skx064

General Administration of Quality Supervision. (2002). “Code for product quality inspection for cattle and sheep in slaughtering 中华人民共和国国家质量监督检验检疫总局近期批准发布的部分国家标准介绍[J].监督和选择,” in: General Administration of Quality Supervision, Beijing, China.

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., and Chadwick, P. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 204, 291–295. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Grandin, T. (2015). “The Effect of Economic Factors on the Welfare of Livestock and Poultry,” in Improving Animal Welfare: A Practical Approach, ed T. Grandin. (Wallingford, UK: CABI), 278–290.

Grandin, T. (2020). “The importance of good pre-slaughter handling to improve meat quality in cattle, pigs, sheep and poultry,” in The Slaughter of Farmed Animals: Practical Ways of Enhancing Animal Welfare, eds T. Grandin, and M. Cockram. (Wallingford, UK: CABI), 229–244.

Green, L., Kaier, J., Wassink, G., King, E., and Grogono, T. (2012). Impact of rapid treatment of sheep lame with footroot on welfare and economics and farmer attitudes to lameness in sheep. Anim. Welfare 21, 65–71. doi: 10.7120/096272812X13345905673728

Guoqing China. (2019). 第一届世界农场动物福利大会_中国国情_中国网. Guoqing China.Available online at: http://guoqing.china.com.cn/2019-09/12/content_75199120.htm (accessed, April 14 2022).

Harley, S., More, S., Boyle, L., O' Connell, N., and Hanlon, A. (2012). Good animal welfare makes economic sense: potential of pig abattoir meat inspection as a welfare surveillance tool. Irish Vet. J. 65, 11. doi: 10.1186/2046-0481-65-11

Huang, J. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture and rural poverty in China. J. Integr. Agric. 19, 2849–2853. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63469-4

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). World Economic Outlook Database. International Monetary Fund (IMF).Available online at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021 (ccessed, April 14, 2022)

Koh, L. P., Li, Y., and Lee, J. S. H. (2021). The value of China's ban on wildlife trade and consumption. Nat. Sustain. 4, 2–4 doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00677-0

Lai, J., Wang, H. H., Ortega, D. L., and Widmar, N. J. O. (2018). Factoring Chinese consumers' risk perceptions into their willingness to pay for pork safety, environmental stewardship, and animal welfare. Food Control 85, 423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.09.032

Li, P. J. (2021b). Animal Welfare in China: Culture, Politics and Crisis. Australia, Sydney University Press.

Lin, J. Y. (1988). The household responsibility system in China's agricultural reform: a theoretical and empirical study. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 36, 199–224. doi: 10.1086/edcc.36.s3.1566543

Littlefair, P. (2006). Why China is Waking Up to Animal Welfare. Animals, Ethics and Trade: The Challenge of Animal Sentience. London, UK: Earthscan.

Liu, S., Ma, Z. F., Zhang, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Attitudes towards wildlife consumption inside and outside Hubei Province, China, in Relation to the SARS and COVID-19 Outbreaks. Human Ecol. 48, 749–756. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00199-5

Loh, H. H., Seah, Y. K., and Looi, I. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and diet change. Prog. Microbes Molec. Biol. 4, a0000203. doi: 10.36877/pmmb.a0000203

Lu, J., Bayne, K., and Wang, J. (2013). Current status of animal welfare and animal rights in China. Altern. Lab. Anim. 41, 351–357 doi: 10.1177/026119291304100505

Magouras, I., Brookes, V. J., Ferran, J., Angela, M., Pfeiffer, D. U., and Dürr, S. (2020). Emerging zoonotic diseases: should we rethink the animal–human interface? Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 582743. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.582743

Mateus, J. R., Da Costa, P., Huertas, S. M., Gallo, C., and Dalla Costa, O. A. (2012). Strategies to promote farm animal welfare in Latin America and their effects on carcass and meat quality traits. Meat Sci. 92, 221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.03.005

McInerney, J. P. (1993). “Animal Welfare: An Economic Perspective,” in Valuing Farm Animal Welfare - Occasional Paper No 3, ed R.M. Bennett (Reading, UK: University of Reading Dept of Agricultural Economics and Management), 9–26.

Ministry of Agriculture China. (2005). Animal Health Inspection Code for Swine Slaughter NY/T 909-2004 生猪屠宰检疫规范. In: Agriculture, C. M. O (Beijing).

Nielsen, B. L., and Zhao, R. (2012). Farm animal welfare across borders: a vision for the future. Anim. Front. 2, 46–50. doi: 10.2527/af.2012-0048

Ortega, D., Wang, H., Wu, L., and Hong, S. (2015). Retail channel and consumer demand for food quality in China. China Econ. Rev. 36, 359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2015.04.005

Pei, X., Tandon, A., Alldrick, A., Giorgi, L., Wei, H., and Yang, R. (2011). The China melamine milk scandal and its implications for food safety regulation. Food Policy 36, 412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2011.03.008

Pinillos, R. G., Appleby, M. C., Manteca, X., Scott-Park, F., Smith, C., and Velarde, A. (2016). One welfare–a platform for improving human and animal welfare. Vet. Rec. 179, 412–413. doi: 10.1136/vr.i5470

Quammen, D. (2012). Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. New York, USA, WW Norton & Company.

Rostagno, M. (2009). Can stress in farm animals increase food safety risk? Foodborne Pathog Dis. 6, 767–776. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0315

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 80, 1–28. doi: 10.1037/h0092976

Schoenmakers, K. (2020). How China is getting its farmers to kick their antibiotics habit. Nature 586, S60–S62 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02889-y

Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K. S., Faucitano, L., Dadgar, S., Shand, P., González, L. A., and Crowe, T. G. (2012). Road transport of cattle, swine and poultry in North America and its impact on animal welfare, carcass and meat quality: a review. Meat Sci. 92, 227–243. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.010

Shi, J. Z. (2020). 我国动物福利发展回顾与展望 [Developments in Chinese Animal Welfare] [Conference session] in 2nd Annual Welfare Science (China) Quality and Welfare Egg China Summit. Shanghai, China.

Shields, S., and Greger, M. (2013). Animal welfare and food safety aspects of confining broiler chickens to cages. Animals 3, 386–400. doi: 10.3390/ani3020386

Siche, R. (2020). What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture. Sci. Agropecu. 11, 3–6. doi: 10.17268/sci.agropecu.2020.01.00

Sinclair, M., Fryer, C., and Phillips, C. J. C. (2019). The benefits of improving animal welfare from the perspective of livestock stakeholders across Asia. Animals 9, 123. doi: 10.3390/ani9040123

Sinclair, M., and Phillips, C. J. C. (2017). The cross-cultural importance of animal protection and other world social issues. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 30, 439–455. doi: 10.1007/s10806-017-9676-5

Sinclair, M., and Phillips, C. J. C. (2018). Key tenets of operational success in international animal welfare initiatives. Animals 8, 92. doi: 10.3390/ani8060092

Sinclair, M., and Phillips, C. J. C. (2019). International livestock leaders' perceptions of the importance of, and solutions for, animal welfare issues. Animals 9, 319. doi: 10.3390/ani9060319

Sinclair, M., Zito, S., Idrus, Z., Yan, W., Nhiem, D., Lampang, P., et al. (2017). Attitudes of stakeholders to animal welfare during slaughter and transport in SE and E Asia. Anim. Welfare 26, 417–425. doi: 10.7120/09627286.26.4.417

The World Bank. (2021). GDP growth (annual %) - China, World. The World Bank. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2020&locations=CN-1W&start=1977 (accessed, April 14 2022)

United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). Preventing the Next Pandemic: Zoonotic Diseases and How to Break the Chain of Transmission. Nairobi, Kenya.

Ventin, M. (2020). Valuing Farm Animal Welfare in a Market Economy: A Philosophical Study of Market Failure. Durham University. Available online at: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13661/ (accessed, April 14 2022)

Vetter, S., Vasa, L., and Ózsvári, L. (2014). Economic aspects of animal welfare. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 11, 119–134 doi: 10.12700/APH.11.07.2014.07.8

Weary, D. M., Ventura, B. A., and Von Keyserlingk, M. A. G. (2015). Societal views and animal welfare science: Understanding why the modified cage may fail and other stories. Animal 10, 309–317. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115001160

World Animal Protection. (2017). ). 大北农集团加入提高动物福利行列. Da Bei Nong Company Joins the Ranks of Improving Animal Welfare. Available online at: https://www.worldanimalprotection.org.cn/news/dabei-agricultural-group-joined-to-improve-the-ranks-of-animal-welfare (accessed, April 14, 2022).

Xinhuanet. (2020). 蒙牛编撰《牧场奶牛福利推广实施体系》为产业链送福音-新华网 [Mengniu drafts<Farm Dairy Welfare Implementary Strategy> Bringing Good News for Supply Chain]. Available online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/food/2020-04/20/c_1125881053.htm (accessed, April 14, 2022)

Yang, X. (2020). Potential consequences of COVID-19 for sustainable meat consumption: the role of food safety concerns and responsibility attributions. Br. Food J. 123, 455–474. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-04-2020-0332

You, X., Li, Y., Zhang, M., Yan, H., and Zhao, R. (2014). A survey of Chinese citizens' perceptions on farm animal welfare. PLoS ONE 9, e109177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109177

Zhang, Z. L. (2018). 试论我国农场动物福利立法的紧要性 (Urgency to Implement Farm Animal Welfare Legislation in China). Acta Ecologiae Animalis Domastici. 39, 86–89.

Zhou, Z. (2010). Achieving food security in China: past three decades and beyond. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2, 251–275. doi: 10.1108/17561371011078417

Keywords: animal welfare, China, opportunities, animal protection, livestock, progression, legislation, food safety

Citation: Sinclair M, Lee HP, Chen M, Li X, Mi J, Chen S and Marchant JN (2022) Opportunities for the Progression of Farm Animal Welfare in China. Front. Anim. Sci. 3:893772. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2022.893772

Received: 10 March 2022; Accepted: 15 April 2022;

Published: 19 May 2022.

Edited by:

Janice Swanson, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sarah Halina Ison, World Animal Protection, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Sinclair, Lee, Chen, Li, Mi, Chen and Marchant. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle Sinclair, bS5zaW5jbGFpcjZAdXEuZWR1LmF1; bXNpbmNsYWlyQGxhdy5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.