94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anim. Sci., 18 April 2022

Sec. Animal Welfare and Policy

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2022.835317

Replacement heifers are key to the future milking herd and farm economic efficiency but are not always prioritised on dairy farms. Dairy enterprises are comprised of components which compete for limited resources; scarce information about calf performance and the associated losses and (potential) gains on farms can mean calves are prioritised less in management and investment decisions. The research reported in this paper explored the personal and contextual factors that influence calf management decisions on dairy farms. Forty in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with dairy farmers (26 interviews) and farm advisors (14 interviews) who were recruited using purposive and “snowball” sampling. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and thematically analysed. Six major themes were constructed from the interview data relating to: the perceived importance of youngstock management, the role and influence of calf rearers, calf performance monitoring, farmer engagement with information and advice, the quality of communication and advice, and veterinary involvement in calf rearing. Results indicated that although the wider dairy industry has promoted the importance of youngstock, calves often have not been fully integrated into the whole dairy farm system, nor culturally accepted as an integral part of the productive herd. Calves tended to be marginalised on farms, largely due to limited resources, lack of data monitoring, and their unrecognised potential, as well as social norms and scarcity of support structures impacting upon farm investment and management decisions. Many calf rearers were disappointed by the repetition and impractical nature of information in print media. Most farmers did not routinely consult their veterinarian about their calves, rather following a reactive treatment model even when a preventive herd health strategy was applied to the adult herd. Advisory structures often require a driven individual with calf-centric interest to prevent calves from being overlooked. Furthermore, advisory efforts often failed to motivate farmers to act on advice. These findings indicate the need for greater focus on how to achieve rearing targets by provision of technical and support structures to foster action toward improved calf wellbeing, and for the status of calves to be raised in line with their vital importance for the future dairy herd.

The rearing of replacement heifers is of great importance to the economic efficiency of dairy enterprises; the annual cost of rearing replacement heifers is estimated to account for ~20% of total production costs, and is the second-highest variable cost on dairy units after feed for the milking herd (Boulton et al., 2017). Boulton et al. (2017) calculated the average cost to rear a replacement heifer to first calving to be £1819 ($2506), ranging from £1073 to £3070 ($1479–$4230) depending on farm factors including average age at first calving, calving pattern, rearing system, and other management decisions. In addition to the financial implications of calf rearing, heifers represent the continuation and genetic merit of the future milking herd (De Vries, 2017). In the UK, the replacement rate has been increasing since the 1990s (Evans et al., 2006), with figures indicating an increase from 23 to 28% between 2007 and 2020, respectively (AHDB, 2020a), reflecting increased demand for replacement heifers to replace cull cows and/or increase herd size. The value of dairy bull calves poses some problems, as low market values have meant they have been considered almost as a waste by-product of the dairy industry, although the industry has committed to eliminating the practise of euthanizing healthy calves by 2023 by changing breeding practises to modify the supply chain (AHDB, 2020b).

Calfhood performance influences the future productivity of heifers; growth rates of 0.75 kg/day (Cooke and Wathes, 2014; Van De Stroet et al., 2016) and good health are associated with improved longevity and lifetime milk production (Waltner-Toews et al., 1986; Wathes et al., 2008; Bach, 2011). This is in part due to achieving an earlier age at first calving (AFC) (Cooke et al., 2013; Cooke and Wathes, 2014). Heifers that calve for the first time at 23–24 months are less expensive to rear and provide an earlier return on investment than later calving animals (Boulton et al., 2017). Recent industry efforts have aimed to highlight the importance of calves achieving a target AFC of 24 months, for example as shown by the Calf to Calving initiative promoted by the British industry levy board (AHDB Dairy, 2021). This included the publication of reports and relevant articles in the farming press, and support from several charitable organisations, feed companies, nutritionists, veterinarians, and agricultural advisors representing the wide range of agricultural knowledge providers within the UK who provide information resources which include webinars, farm events, and discussion groups. Despite these efforts, average AFC in the UK has remained at 27 months since 2015 (Hanks and Kossaibati, 2020). There is also evidence of high rates of morbidity and mortality in dairy calves (Johnson et al., 2017; Baxter-Smith and Simpson, 2020) which are often underestimated by producers (Vasseur et al., 2012).

Dairy enterprises are comprised of many components which compete for limited resources, especially time and labour (Kristensen and Enevoldsen, 2008). The costs associated with rearing replacement heifers are largely hidden and return on investment is delayed until heifers enter the milking herd (Boulton et al., 2017). Whereas data on the milking herd is generally routinely gathered, there is comparatively little information about calf performance available on farms (Bach and Ahedo, 2008). Limited information at the farm level about youngstock performance and associated losses and (potential) gains means that the perceived importance of calves and heifers largely depends on the assumptions and value judgements made by the farmer (Moran, 2009). Indeed, dairy farmers tend to underestimate the cost of rearing replacement heifers, which can mean calves are prioritised less in management and investment decisions (Mohd Nor et al., 2015).

Lack of data relating to calf performance also contributes to ambivalence about assessing and managing calves and questioning routine practises (Sumner et al., 2018). A UK-based questionnaire showed that ~50% of veterinarians, compared to 15% of farmers, reported that calf mortality was a recurring topic during herd health visits (Hall and Wapenaar, 2012). Farmers might not seek advice regarding their calf rearing practises, nor perceive a need to do so. Calf management is not typically discussed by farmers, unless a specific calf-related problem is identified, in part because calf rearing is perceived as straightforward (Sumner et al., 2018). Indeed, findings from an online survey of Austrian farmers revealed only one third of respondents considered the veterinarian to play an important role regarding calf management (Pothmann et al., 2014).

Even when advice is sought and received, recommendations are not necessarily implemented on farms (Kristensen and Jakobsen, 2011). Further, it has been suggested that veterinarians fail to identify farmers' goals and priorities (Kristensen and Enevoldsen, 2008; Derks et al., 2013), assuming that they focus primarily on production, whereas farmers have been shown to value animal welfare and herd health planning more for reasons of subjective wellbeing such as pride and job satisfaction (Kristensen and Enevoldsen, 2008). As reviewed by Kristensen and Jakobsen (2011), farmers' motivations might relate to their identity (Burton, 2004), perception of risk, and perceived need and ability to improve a situation (Vaarst and Sørensen, 2009). Farmers are also influenced by their social networks (Heffernan et al., 2008; Azbel-Jackson et al., 2018).

Replacement heifers play a vital role in farm economic efficiency (Boulton et al., 2017) but are not always perceived as doing so. Calves might be considered in terms of their instrumental usefulness (serving a financial and/or functional role) and intrinsic value framed within personal and societal values and beliefs (Hill, 1993). Decisions regarding their rearing are likely to be complex and nuanced, influenced by a variety of personal and contextual factors (Hansen and Greve, 2014). For instance, the anticipated benefit in having access to calf data has been linked to personal values, the perceived intrinsic value of calves, and the instrumental value of calves as a productive member of the future milking herd (Sumner et al., 2018).

The objectives of the research presented in this paper were to explore the ways in which the perceived value of youngstock and their performance impact on the ways in which calves are managed on-farm. The research also considered the role of advisory services and the wider dairy industry in the framing of calves as an integral part of the dairy herd. The findings presented here are part of a wider research study which used in-depth, semi structured interviews and thematic analysis to seek a holistic understanding of calf management on English dairy farms. Results relating to colostrum management (Palczynski et al., 2020a), calf feeding (Palczynski et al., 2020b), and disease management (Palczynski et al., 2021) have been presented elsewhere. This paper presents findings related to the perceived value of dairy youngstock, collection of calf performance data, and the availability of calf-oriented information and advice.

This research used a critical realist perspective, meaning that subjective experiences and beliefs have real-world consequences and should be considered alongside objective facts to understand phenomena (Maxwell, 2012). The COREQ criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007) were consulted and followed. The interviews were conducted by the first author, a female doctoral student with an interest in human attitudes and behaviour relating to animal husbandry and with initially a basic knowledge of the dairy industry. Participants were invited to confer their expert knowledge and opinions to the curious researcher through the interview discussions.

Participants were recruited using purposive and “snowball” sampling (Cohen et al., 2007), starting with existing university and industry networks and contacts with veterinary practises, individuals attending dairy trade events and conferences, and persons suggested by interviewees. The first author did not know any of the participants prior to arranging and conducting the interviews. Participation was entirely voluntary and based on the individuals' willingness to talk to a postgraduate researcher about calf and youngstock management in the dairy sector. A range of dairy production systems and herd sizes were represented, and participants worked in one of three geographical areas in England: the Southwest and Midlands (high densities of dairy farms) and Northeast (less dairy focus).

In total, 40 face-to-face interviews (26 with farmers, 14 with advisors) were conducted between May 2016 and June 2017; average interview length was 56 min, with a range of 26–90 min. Three interview formats were used, based on the preference of the participant: individual interviews in a seated setting (n = 23); joint interviews (n = 9), where two to three participants (n = 20) were interviewed together; or walking interviews during a tour of the farm and calf facilities (n = 8) (Table 1). Interviewees included 37 dairy farmers [farm managers (n = 17), farm workers (n = 9), calf rearers (n = 8), and herd managers (n = 3)], and 14 advisors (veterinarians (n = 10), a veterinary government advisor (n = 1), feed (n = 2), and veterinary pharmaceutical company (n = 1) representatives) (Table 1). This variation satisfied the need for rich, detailed data from a range of contexts, in line with quality criteria for qualitative research (Turner, 2010).

Questions in the interviews were based on a topic guide (one guide was designed for farmers, another for advisors) and were deliberately broad, looking to obtain a general overview of participants' experiences related to calf rearing on dairy farms and to allow them to lead the discussion to focus on areas of most interest or importance as perceived by the participant. Additional probing questions were sometimes asked to gain further insight into the participant's initial response. The farmer topic guide included questions about experiences relating to the management of calves from birth through subsequent stages of service and first calving, as well as the availability of advice and treatment of calves on other farms and in the wider dairy industry. The advisor topic guide focused on the services offered to clients, their involvement in and perception of youngstock rearing on their clients' farms, and the most important/problematic aspects of calf rearing on farms and in the wider dairy industry. Interviews were audio-recorded and assigned a representative code: a letter referring to the type of participant (farmer, F; veterinarian, V; feed consultant, N; pharmaceutical company representative, DR; veterinary government advisor, GA) and numbered in chronological order for each grouping (F1, F2, F3, etc.).

Data collection and analysis were conducted in an iterative approach until it was judged that no new themes were emerging, indicating thematic saturation (Miles et al., 2014). Analysis was grounded in the data, and no preconceived framework was used to group extracts into themes.

Audio recordings of the interviews were manually transcribed using f4transkript software (Version 6.2.5 Edu, audiotranskription.de, Marburg, Germany) which provides an integrated interface for typing transcripts whilst controlling audio playback. The interview transcripts were then thematically coded in NVivo for Windows (Version 11.4.1.1064 Pro, QSR International Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia) to group common extracts into themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). First, content coding was used to group extracts according to topic (Miles et al., 2014), i.e., management practises, processes, and personal values. This helped to inform ongoing interviews and indicate focal topics for further analysis. Once data collection was completed, coding was repeated for in-depth exploration of extracts relating to each focal topic. Focal topics were chosen based on the frequency and breadth of relevant responses which indicated good data richness. Salient points raised by one participant were considered as important as those expressed by multiple interviewees when establishing themes. Analysis was conducted across groups, but it was noted whether viewpoints were common or outliers in the sample, expressed by only farmers or advisors, or both groups, and any conflicting perspectives were explicitly noted.

Extracts were chosen to represent the perceptions of participants which informed the construction of themes and explanations by the first author. Quotes from participants are presented within quotation marks; ellipses indicate omission of text; and square brackets indicate clarifications from the authors. The extracts most relevant to perceived importance/value of calves tended to be in response to requests and questions like “tell me about your farm,” “talk me through your calf management,” “do you like working with calves?... Why is that?” and “how do you think calves are treated on other farms?.” Quotes about information and advice in relation to rearing calves generally stemmed from questions to farmers asking “where would you get information about calf rearing?” and about the role of their veterinarians with regards to calves. Advisor responses were often replying to questions about the client-advisor relationship, their involvement in calf rearing on their dairy clients' farms, and whether advice was implemented. Comments about calf performance and how it was monitored were usually in response to questions directly asking about calf records, including health and growth data.

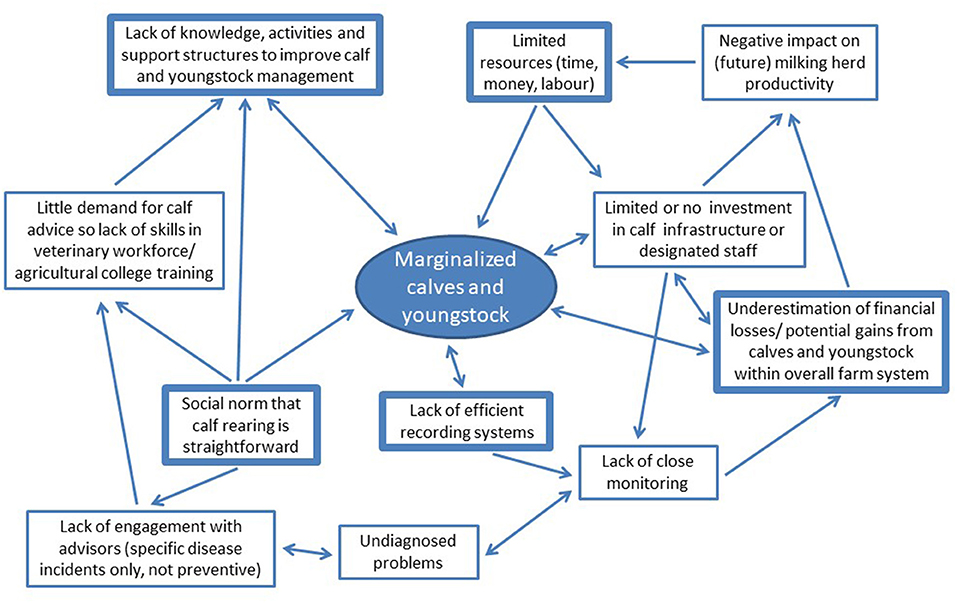

Analysis of these extracts resulted in six overall themes: perceived importance of youngstock management on dairy farms, the role of calf rearers, monitoring calf and heifer performance, farmer engagement with information and advice about rearing calves, quality of communication and advice about calf rearing, and veterinary involvement in calf rearing. To further help visualise the themes, a schematic (Figure 1) demonstrating the complexity and interconnectedness of factors and how they relate to the status of youngstock on farms and in the wider industry is presented as part of the discussion.

Figure 1. Schematic demonstrating the effect of marginalisation of replacement heifer calves. Limited resources, unrecognised potential of calves, lack of data monitoring, social norms, and scarcity of support structures are key areas for improvement.

All participants gave their informed consent for interviews to be conducted, audio recorded, transcribed, securely stored, and for anonymized interview excerpts to be published. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved under project number 75-201511 by the Harper Adams University Research Ethics Committee on 13 January 2016.

Participating farmers valued their youngstock for a variety of reasons. Firstly, there were several use values attributed to calves. It was well-recognised among farmer participants that heifer calves are “the future of your herd, so they are really important” (F2, calf rearer). Youngstock management was also seen, particularly by advisors, to affect the overall efficiency of the farm:

“I just started to find it was the key for everything... If you get your youngstock right, you get them calving at the right age... you need less building space, so that brings in all the building design. You've got less nitrogen to manage, so that brings in the slurry and soils management. It just comes back as such a key thing” (DR1, pharmaceutical company veterinary advisor).

Rearing sufficient replacement heifers also reduced the need to buy-in adult animals, which could protect the herd's disease status:

“I don't like buying cows in. I don't like it at all. I don't like that lack of biosecurity” (F19, farm manager).

Replacement heifer calves were especially valued where large numbers were required to increase herd size or recoup cow losses from the milking herd, particularly as a result of bovine Tuberculosis (bTB):

“We have lost a lot of animals to bTB... [it's] an additional burden to try and cater for the losses, and some years, 150 is barely sufficient replacements” (F26, farm manager of 500-head dairy herd).

However, it was commonly acknowledged that calf rearing had historically not been a key focus in the dairy industry and that calves were still marginalised on many farms. Generally, it was perceived that “calves get to be second citizens quite often... most people are focusing on their dairy cows” (V7, farm veterinarian). Some advisors believed that most farms could stand to further improve processes and management related to milk production, so it was considered unsurprising that calves were overshadowed:

“The best attention's gonna be given to getting the milk out of the cows because the milk's the bit you sell - and they [farmers] can't even do that very well” (V8, farm veterinarian).

Even on high-profile, award-winning dairy farms, advisors witnessed that the youngstock facilities were often under-invested in:

“A lot of these really top units, they're going for the Gold Cup [award for excellence and efficiency in the British dairy industry] and they're winning herds everywhere, and you go and look round the calf units and it's as if you're going back in time into the '60s” (V11, youngstock veterinarian).

The ability to finance improvements to youngstock management and facilities might be limited when balanced against the expense of managing and maintaining the milking herd and parlour, particularly during a downturn in milk prices, when farmers may struggle to invest in infrastructure and staff:

“I think the hunger for capital for the dairy herd is so colossal and so immediate, it soaks up all the good all the time. Profitability has been so low, and under so much pressure for quite an extended period of time, that there is never anything spare to apply to the youngstock and they are the poor relations on a good many farms, I suspect” (F26, farm manager).

“If milk price was 35 pence a litre, I'd have someone else working with me, and then I would have a lot more time to spend making sure that my calf rearing protocols were as I wanted, in sheds that I wanted, because I'd be able to afford them... the biggest limiting factor to animal welfare, I believe, is purely down to the constant pressure on price” (F19, farm manager).

Added to this, the financial significance of youngstock rearing may not be recognized by farmers, in part due to a lack of calf performance monitoring:

“[We] record everything that we're doing. I didn't really know exactly what it cost us to rear a heifer [before monitoring their performance]. Now I do... The worst guys are spending £3000 [$4146.75] per heifer on heifer rearing and probably calving them at three years old, and not making money until they're in about their third, fourth, or fifth lactation and they don't realize... They moan and say they're not making any money out of milk” (F10, farm manager).

This was likely due to the comparative invisibility of rearing costs and delayed return on investment for youngstock compared to the productivity of the milking herd:

“When you're worried month on month how much money you're gonna bring in... you want to make sure that there's milk in the tank that's gonna pay your wage and pay your bills for the month” (F1, calf rearer).

“It's never as urgent, I don't think. So the [somatic] cell count goes too high, and the milk company start paying you less, you want that fixed tomorrow. If your calves aren't growing as fast as they could, you can wait before you fix that. I guess that's always going to be a bit of a barrier” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health).

Whereas replacement heifer calves are inherently valuable to the future of dairy farms, the value of dairy-bred bull calves was considered highly market-dependent. Bull calves received less attention compared to heifer calves on some farms, but where there was good return on investment for healthy bull calves, their standard of care was likely to increase:

“They're babies, they all need the same care and attention. I am able to sell my bull calves at £100 a piece at the moment, which I think is pretty good for Friesian bulls, and that's only because they're reared well and they're fit and healthy” (F6, calf rearer).

“Doing a guaranteed buy-back regime for the dairy-cross calves and for the male dairy calves... if they're 50 kilograms by two weeks. By heck, suddenly there were all these farmers feeding ad lib milk replacer to their calves to get them up to the right weight” (GA1, government veterinary advisor).

However, many farmers struggled to find an outlet for their unwanted dairy bull calves due to their low market value, particularly those farmers under restriction for bTB or running Jersey or Jersey-cross herds:

“We have moved entirely to sexed semen. That's also to improve upon the dreadful problems of disposing of black and white bull calves, which are virtually valueless in a TB-afflicted herd, there's so few outlets for them” (F26, farm manager).

Farmer participants viewed the practice of euthanizing male dairy calves as a necessary business decision on some farms, but interviewees preferred to avoid the practice:

“[The Jersey farm down the road], they tried every single avenue they could think of. They tried giving calves away, they tried rearing them themselves, they tried bull calves, they tried castrated calves... nothing would make a profit off Jerseys, and so they carried on shooting them” (F22, herd manager).

“We don't receive a lot of money for our bull calves, and it's more labour, feed, time we invest in them, but I'd rather just spend a little bit more and get them slaughtered than shoot them... I just wouldn't want to shoot a newborn calf, really... you give them as good a life as you can for a few weeks and then they go, I think that's a better way of doing things, than shooting them” (F24, herd manager).

There was a lot of pride involved in calf rearing amongst the participants. Calf rearers enjoyed working with calves, and were satisfied knowing they were contributing to the future of the dairy herd:

“I like them [the calves] to look good, and I like them to be healthy. That's kind of what drives me. And I love them when they're looking perfect, so the minute they don't look perfect, I'm like ‘why?”' (F18, calf rearer).

“I love it [working with calves] because look at what I've helped produce [dairy cows]!” (F15, calf rearer).

For optimal calf management, most participants believed there was great benefit to “having a designated person, somebody responsible” (F2, calf rearer) for calves, so they were invested and had time to do a good job:

“If it's your sole job and you've got a passion for it, then you're gonna do it well” (F4, farmer's son and trainee veterinarian).

“If you've got plenty of staff, then no one's overstretched for time. They haven't gotta do this, this, this and this - they've just gotta do the calves... It's calm, it's simple, it's just your job” (F19, farm manager).

There were mixed opinions about the need for previous experience of calf rearing:

“The girl I've got [rearing calves]... she'd come from completely outside farming. No preconceived ideas. Which is good” (F20, farm manager).

“If you get a good person, that's key, who is committed to the job. Whether they've done calves before or not, I don't think that matters as much because you can train them. It's that willingness to learn and want to try new things, and that attention to detail” (V11, youngstock veterinarian).

“The more experience the better... It's alright someone having passion, but if they don't know what they're doing, if no one is there to tell them, teach them how to do it, then they're a sitting duck” (F4, farm worker).

Several participants agreed with the belief that “girls [females] are much better at calf rearing than fellas [males] are” (F26 male farm manager), due to greater maternal, nurturing instincts. Others (especially young females) claimed gender was irrelevant to the competence of calf rearers:

“I don't feel it makes any difference … I really don't think it's better for women or men to do [the calf rearing]. I just think it's probably just like in history, how the male's taken over the family farm … the farming wife sort of joined the family and that [calf rearing] was their role to start with.” (F1, female calf rearer).

It was agreed that there were common qualities a person needed to be a good calf rearer, regardless of gender. These included keen observational skills and attention to detail to allow them to prioritize good hygiene and notice early signs of illness and other potential problems for quick intervention. Patience and perseverance were also considered necessary, particularly when training calves to drink from milk feeders. A passionate person who cared about calves and their importance to the dairy enterprise, who had adequate time allowed for calf rearing was considered a recipe for success.

Unfortunately, it was not always possible to employ someone to only rear calves. There was insufficient work to warrant a full-time position focused on calves on some farms and often there was limited budget available to cover staff costs. This meant that calf feeding was just another job to get done, which might exacerbate the marginalisation of calves on farms.

“To find someone that will just come down for an hour or two hours every day, it's really quite hard” (F16, calf rearer).

“Here, there's only three of us, so the general farm worker, he does all the scraping [of manure] and odd jobs, and he feeds the calves. So when you add that to a long day, and you feed them twice a day, you can miss things” (F24, herd manager).

For farms where several people were responsible for calves, calf rearing protocols were considered necessary, but it was noted that “they're not worth the paper they're written on unless they're followed” (F21, farm manager). Successful calf rearing with multiple responsible persons was considered to be “completely dependent on communication” (F9, farm manager) between different staff members. Notes and records could help, so long as everyone wrote legibly and checked the information. This teamwork was dependent upon individual values to ensure everyone played their part and shared information.

Disbudding calves was a practise which clearly demonstrated a range in personal values regarding calves and calf management. Most participants empathised that the head wound resulting from disbudding would hurt in the time following the initial procedure, so provided analgesia in addition to local anaesthetic:

“If it saves them two or three days of pain, it's probably an investment in their growth rate... and it's just the right thing to do” (F21, farm manager).

However, following a change in staff responsibilities (thereby changing personal values), one farm had reverted to following minimum legal standards (as per The Protection of Animals (Anaesthetics) Act 1954, as amended), disbudding using local anaesthetic without pain relief:

“I used to use Metacam® [Meloxicam-based Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug (NSAID, Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health UK Ltd.] for post-pain relief, but I don't do the dehorning anymore, so they just use Adrenacaine [Adrenaline and Procaine Hydrochloride-based local anaesthetic, Norbrook Laboratories Ltd.]... it must make them feel poorly having these wounds on their head. That's why I used to use the long-acting one, but the general advice is just [local anaesthetic] so...” (F22, herd manager).

Another farmer sedated his calves for disbudding to reduce the stress experienced by the calves and the handlers. He believed eliminating the need to restrain calves conferred better welfare and would be perceived more positively by the public:

“How do you justify that to the general public? With two strong men holding down a calf and... I know you're supposed to use local anaesthetic, and we always did because it's cheap. I know plenty of farmers that don't. They say” that'll take too long because you've gotta catch them, inject them, leave them ten minutes and then come back and catch them again“... The only way to justify to the public, method of doing it, in my opinion is to sedate them. And [provide] pain relief as well” (F16, farm manager).

Several farmers opted to use their veterinary practice's technician service to save time and labour and ensure disbudding was “done properly” (F21, farm manager). Breeding polled cattle is another option to improve welfare by avoiding the need for disbudding but was only mentioned by two farmer interviewees (F20, farm manager; F22, herd manager).

Participants believed that the importance of calf management was becoming increasingly recognised by dairy farmers and the wider industry. Although some farmers indicated that they “don't often come across calf ones [events]” (F22, herd manager) in regions less focused on dairy, more generally it was thought that calves and calf rearing facilities were more likely to be featured at on-farm events than they were previously, which could both reflect and contribute to increased interest in calf rearing:

“When I used to go out on farm walks, you didn't often get to see the calves, and I used to wonder why. But now I think people are getting much better at it [calf rearing] and realising that if you treat them right to start with, then they can save you a fortune” (F6, calf rearer).

This might in part be due to industry efforts to highlight the financial significance of calf rearing and meeting recommended rearing targets. All participants were aware of the recommendation to achieve an AFC of 24 months, though when asked, most were not meeting that target. Several farmers opined that information and advice lacked focus on practical ways to achieve rearing targets and justify investments:

“I don't know if we've had enough focus on what we can do to improve calf rearing. It's more just we're hearing the implications of it, which is the start of the process because until farmers realise that there are financial implications of poor calf rearing then you don't try to improve” (F9, farm manager).

Failure to achieve an average AFC of 24 months was partially related to calf growth rates, since participants stressed the importance of heifers being large and mature enough to be served and enter the milking herd:

“If you have a heifer that's [calved at] three years old, they're not usually any good. Two and a half seem to be alright [AFC 30 months], two [AFC 24 months], I think they're probably not [developed enough] - because we're on a forage-based system, they need to be a certain amount of size” (F15, farm manager of an all-year-round calving herd).

Delayed first calvings could also be attributed to service period management of youngstock, particularly where heifers were housed away from the main farm, or at pasture:

“You want to make the most of the grazing season, but then on the other hand you want them in to serve them... The first ones [born] do tend to get a little bit over [15 months at serving]” (F10, farm manager).

“It's just having the organization to actually get them to somewhere where they can be with a bull, or be served” (F3, calf rearer and farm worker).

Failure to account for the heifer rearing period was not limited to farmers; many veterinary services also focus only on the first months of life:

“What some of the other vets are offering, it basically stops at weaning because then [the heifers are] out this time of year whereas that's when a lot of the truly unrecognized problems go on... [Farmers] won't do any grazing management for youngstock... then they go” Oh, these aren't big enough to bull now"“ (V11, youngstock veterinarian).

Although farmer participants indicated the most common calf ailments on their farms, they did not report disease incidences or mortality rates, suggesting a lack of formal records and review of calf data. On some farms, basic information relating to calf health (colostrum feeding and incidences of diarrhoea and pneumonia) was recorded, usually written on whiteboards or in a book, to communicate between staff members about day-to-day calf management. However, transferring treatment practises to long-term records could be problematic:

“It's alright having a book, but with the best will in the world, you're doing another job across there, then you're doing something else, think “Ah, I haven't written it [calf treatment] in the book” and you've forgotten it, unless you write it on your hand or a scrap of paper or something. Even if you've got a diary you've gotta transfer it” (F8, farm manager of dairy bull calf rearing unit).

Despite farm assurance regulations which require the reporting of calf illness and treatment data, veterinarians believed many farmers used guesswork rather than records to report on calf health, particularly since herd health assessments were more focused on the milking herd:

“Herd health plans, my experience of them wouldn't be great... They don't focus mainly on calves... They ask you to fill in the number of cases of scour and pneumonia… well, most people are making numbers up and don't really know” (V3, youngstock veterinarian).

Some farmers were enthusiastic about digital technologies—cloud-based systems for easy single-entry recording of calf treatment data which could fulfil both management and paperwork requirements:

“I want a system where I've got auto-ID on the calves... So, my phone: zap - she's had [treatment]. Done. Up to a database... cloud-based... that the vet can get hold of” (F20, farm manager).

“You can put absolutely everything on [the app],'it's on everyb'dy's phone... you can print reports” (F8, farmer's wife on dairy bull calf rearing unit).

However, some advisors might overlook digital solutions as a way to make record-keeping easier for farmers:

“Technology does make things easier. You tend to think “Oh, keep it simple, keep it just on a paper-based thing”, but actually we all carry our phone around in our pocket all the time” (V5, youngstock veterinarian).

The perceived importance of calf growth performance monitoring varied amongst farmers. Some farmers weighed/measured calves at regular intervals from birth, others at key milestones like birth, weaning, and/or turnout and a few collected group averages by running calves in a trailer over a local weighbridge. Most farmer participants were not recording calf growth data. Although many of them intended to start by reviewing staff responsibilities or investing in (automated) handling systems for weighing calves, in several cases a lack of motivation, or ability, to collect calf weights was apparent:

“Too much hassle. Calves are forgotten about as it is on 90% of dairy farms I've come across. So, let alone an extra job [growth rate monitoring] that doesn't really give you much out of it when you can judge by eye” (F22, herd manager).

“I would like to [monitor growth rates]... It's a time aspect really, because I have to milk as well, so that's already seven hours milking and then the calves can take up to four hours a day” (F3, calf rearer and farm worker).

Several participants would judge performance retrospectively based on meeting or missing targets, for example:

“Growth rate doesn't really matter. It's getting that heifer to first calve down to 24 months” (F5, farm manager).

This suggests that, for some, a problem would need to be perceived before weighing calves was considered beneficial enough to warrant the extra time and effort involved in collecting the data:

“If they're not growing to the size of what you want them to be when you're going to serve them, and they're not calving down at an appropriate age... that's when you'd have to start getting into the nitty-gritty [growth monitoring]” (F4, farm worker).

This is somewhat paradoxical since data monitoring could help to identify problems and allow timely interventions to be made; this was considered valuable information by those who were monitoring calf growth rates:

“It does help to know that you are doing the right thing and you can pick out any that aren't growing and then you can do something about it if you need to” (F6, calf rearer).

The reluctance to monitor calf growth performance appeared primarily due to the time and labour required for manual weighing of calves. Although advisors often proposed girth measurements as an accessible method for monitoring calf growth due to their low up-front cost, farmers tended to perceive them negatively. The tapes were thought to be ineffective for very small or large calves, difficult to use, and inaccurate:

“The weigh-band actually starts at 40 kilos, which for some [calves] is too [large], which suggests that they're probably 35 to 40 [kilograms]... it's a bit hit and miss” (F11, farm administrator).

“Weigh bands... you have to bend round them... you stop at a certain size because you physically can't get around her very well” (F12, herd manager).

“It's time consuming and I don't think the data would be certain enough... The weigh tapes... give you a good idea... but they're a little bit subjective and time consuming” (F9, farm manager).

Several participants agreed with the principle of needing to develop ways to make “the monitoring of youngstock easier on a far more modest farm” (V6, youngstock veterinarian), more in-line with the passive data collection available for dairy cattle through milk recording. Farmers were enthusiastic about automated systems for weighing calves. However, there could be some issues when combining different technologies from different manufacturers:

“Unfortunately, those collars [for the automated milk feeders] interfere with this weigh [scale from] a different manufacturer. So, we thought it would auto-weigh everything, but the signals are interfering with each other so this isn't auto-weighing, which is a big disappointment” (F11, farm administrator).

Collecting calf data and benchmarking could be effective motivational tools for responsible staff to assess their work performance:

“[A calf rearer on a farm with zero mortality was] set up with a bonus system as to how many calves he got through the system at the end of the calving season. He was just so massively driven. He was putting the effort into monitoring and measuring everything because then he could show to his boss” “look what a good job I've done, I deserve my bonus this year” (DR1, pharmaceutical company veterinary advisor).

“You're sat in a group with everyone else who is hitting [growth targets of] 0.8 [kg/day] and you don't want to be the person not hitting it” (F1, calf rearer).

However, one farmer noted the difficulty in identifying marginal gains and best practices from calf performance data:

“We measure it, we monitor it... it would be lovely to see all these patterns that you guys [researchers] talk about - “if you do this you'll get extra milk here” and so on... You probably have to be doing things a whole lot worse. If we were terrible and we did some things, then we would see the benefit of it, but because we do most things pretty well, it's very difficult to detect the effect of one thing, so it's a little bit frustrating” (F11, farm administrator).

Advisor participants appreciated that it could be difficult to record data, particularly related to calf growth, but considered poor records to limit their ability to provide effective, objective advice about youngstock:

“You can nearly double how long it takes to do a job by recording what you're doing, and labour on a farm [costs money] so you have to make a really significant impact to justify that expense. From a veterinary point of view, it is very hard to do anything without data” (V4, farm veterinarian).

Whereas participating advisors often indicated that some data were better than no data relating to calf health and growth performance, several farmer interviewees appeared to believe that data collection was only worth doing well, since even sub-optimal records would require time and effort to collect and would offer limited, or potentially misleading, information:

“Compromises will have to be made... a farmer just doing weaning weights, he might not do birth weights, but at least it gives him something... taking a picture of a group [of calves] every time I visit and look back over a few months” (V11, youngstock veterinarian).

“You need a proper set-up [to weigh calves]. You need it to be easy, otherwise no one's going to do it regularly, and there's no point in doing it irregularly” (F22, herd manager).

One option to take the onus of calf data monitoring away from farm staff was to include it as part of a youngstock veterinary technician service. Assuming farmers were motivated to invest in calf monitoring, the service could provide regular weighing of calves to monitor growth rates and analyze treatment data provided by farm staff:

“We as the vets collect the data [growth data and calf illness tallies recorded by farm staff], keep recorded data, and then present it back at regular periods. That's how I think it works best... If you leave it for them to gather the data, they won't gather it well enough, or regularly enough and you won't get it back to interpret it” (V3, youngstock veterinarian).

However, subscription to a youngstock service did not guarantee that farmers would supply the information required by the veterinary practice for analysis:

“Most of the guys that have signed up to our youngstock service, they are paying for this service and for us to analyze the data, are not recording that data. And it's immensely frustrating for us, because even the people that I think have actually really engaged... still half of them are not recording” (V5, youngstock veterinarian).

One farmer believed there was a need for a centralised database to record treatment data to improve transparency in the sector:

“As an industry, we're not honest enough... There should be a national database and we could have all the veterinary records for these animals on [it]. Wouldn't that be brilliant? So, when you buy an animal, you get a history... The whole industry would benefit” (F20, farm manager).

Most participant farmers were quite open to seeking advice. Some enjoyed independent learning, often reading articles in journals and farming magazines. Others claimed they did not have much time to read information, so tended to prefer short summary text and discussion of ideas with other farmers and advisors (including nutritionists, suppliers, veterinarians). The motivations for seeking information varied. Some were keen to gain new knowledge so they could rear calves to the best of their abilities, others would do little research unless seeking to address a perceived problem.

It was commonly assumed that younger, progressive farmers were most driven to learn and implement best practise compared to farmers of an older generation. Reluctance to seek or follow advice regarding calves was perceived to reflect individuals' aversion to change and the general marginalisation of calves on dairy farms:

“Any sane person would hope to improve what they're doing, wouldn't they? It's just the older generation that might not want to - set in their ways” (F22, herd manager).

“[A lot of farmers]... they've not been brought up in a mindset to think about youngstock” (V2, youngstock veterinarian).

Farmer interviewees tended to appreciate engaging with other farmers and advisors—particularly those with hands-on experience of rearing calves—to obtain fresh perspectives from beyond their farm. Discussion groups and farm walks were particularly popular as an opportunity to observe and talk about alternative calf rearing systems:

“All of us need some exposure off the farm. Either you physically remove yourself from the farm... or you bring the exposure to you. They [the youngstock veterinarian and nutritionist] bring it to us because they see it practiced on many other farms” (F26, farm manager).

“Discussion groups are quite good, and farm walks. It's always good to look round other people's [farms to see] how they're doing it. A lot of farmers are quite honest... they'll tell you what problems they've had to start with and how they've addressed that, which is quite reassuring and good to learn from” (F4, farm manager).

However, one farmer believed that some individuals were unwilling to share their knowledge with their peers for fear of losing their competitive advantage:

“Farmers need to be more transparent... they don't wanna tell their neighbours because they wanna make sure they're doing a bit better than their neighbours... But actually, if we all shared all this information, and it was really clear, and we could all calve our [heifers] at 24 months, we'd all be doing better” (F19, farm manager).

The lack of time and labour on farms could mean that farmers “perceive that they don't have time to come to courses, talks” (V7, farm veterinarian). However, “a lot of farmers go to meetings regardless of if they've work to do or not because they like that sort of thing” (F4, farm manager). The time commitment of attending events or groups was influenced by how far farmers had to travel to attend them. In areas less densely populated with dairy farms, local activities were less common. It was also important that advice efforts were high quality and engaging for farmers, since if they were perceived badly, farmers were hesitant to participate in future:

“My experience of [agricultural knowledge provider] hasn't been very good so I don't interact with them much... I guess once you get put off, you don't necessarily go straight back to it” (F9, farm manager).

There appeared to be a somewhat positive bias in peer-to-peer exchange since farmers preferred to share aspects that they were proud of and learn from “the best” (F10, farm manager). However, this could mean that some farmers would feel their calf facilities were not comparable, and would not be inspired to make changes:

“When you go on farm [for a calf event], you go to a youngstock unit, you don't go to a farm that's just got a few calves that are stuck in a shed... I think it's almost beyond their ability to see how they could possibly do that, so then they don't... The people that see the calves a chore, it's difficult to get them to engage, and if they do come and engage, and you actually put them off because you've shown them something beyond their reach, that doesn't help” (V7, farm veterinarian).

Furthermore, farmers who experienced problems could be too embarrassed to discuss them with their close contacts and advisors:

“There are lots of farmers, they know that they do it wrong and they don't do it to the best of their ability and you have got the odd one which is like “Oh no, you can't come and see it” because they know that it's not gonna be up to your standards” (N2, feed company representative).

“They wouldn't tell their friends [about their disasters] because that's too [much] on their doorstep, but they come to our discussion group... we can just laugh... it lightens the mood and people really appreciate being able to talk about it, get it off their chest... We all respect each other. It may not be the best advice, but it's an outlet” (F5, farm manager).

One advisor questioned whether former farmers teaching at agricultural colleges might perpetuate the persistence of traditional calf rearing practises whilst neglecting more recent evidence-based recommendations:

“It's usually former farmers delivering practical elements of calf rearing... within an agricultural college environment... you're trying to teach practical calf rearing, and you say, “let's bring a scientist in and tell you about this”, and the person running the calf rearing unit goes “I know what I'm doing, why do you wanna bring some expert in?” (GA1, government veterinary advisor).

Several advisor participants believed that the persisting problems with calves and calf rearing were related to inadequate communication:

“I don't think there is that much need for more research in how to get it [calf management] right... We know what works, and we have lots of different options in what works. How do we get that more widely adopted and help people find the information?” (DR1, pharmaceutical company veterinary advisor).

“We get the message across... to the same percentage of people every time. You almost need an outreach-type programme to be able to get that information to farmers that don't go to [trade shows], that don't go to benchmarking groups, that don't have the vet [routinely]. It's very difficult to get information to those guys” (V2, youngstock veterinarian).

However, efforts to communicate the basic principles of calf management to more farmers tended to result in the repetition of information in various sources (trade magazines and online) which could be frustrating for farmers who were motivated to do their own research about calf rearing:

“They are quite similar every time, they're the same sort of articles. You don't get much new information” (F1, calf rearer).

Advisor interviewees were often concerned by the potential confusion caused by inconsistent messages from different sources and advisors:

“Agricultural consultants... When their specialist area is, say, banking and finance, and because they are there as that farm's consultant, they make some glib comment about animal health that can be very undermining of the vet who is the specialist on animal health on that farm” (DR1, pharmaceutical company veterinary advisor).

Conversely, farmer participants did not appear to consider mixed messages to be a problem. They preferred “impartial advice” (F2, calf rearer) without commercial influence, but felt able to factor in commercial biases in their assessment of information:

“Occasionally the [events] that are put on [are sponsored] by the drug companies... they're good, they can be quite informative, but there's always a little lean to use their product or whatever, but then as long as you know that it's okay” (F26, calf rearer).

Participating farmers trusted their advisors, particularly their farm veterinarian, to validate information. This appeared to be largely due to their perception that their veterinarians were aware of the latest research and industry developments and could contextualise information for a specific farm:

“One doesn't believe farming press stuff too much unless it's backed by a vet telling you about that report, or somebody emphasizing it” (F4, farm manager).

“If there's something cheaper that'll do just as good a job, you want to be using that, don't you? That's where you rely on the vet to keep you informed of the latest trends and practices” (F8, farm manager of dairy bull calf rearing unit).

“The vet knows your farm, your system, your people, what you're good at. Having something generalized [a written information resource] would be good, but it just wouldn't fit everybody” (F24, herd manager).

Indeed, most veterinarian interviewees felt it was their responsibility as farm advisors to ensure their knowledge was current, and offer tailored advice for individual farms:

“The good, forward-thinking farmers will be as up to date, if not more, than me. So, if you want to work with them, if you want any sort of credibility, you need to be at least as up-to-date as they are” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health).

“The role of vets and other consultants, other members of industry, is to try and help farmers to make the best decisions for their individual farm” (V5, youngstock veterinarian).

“You've gotta do it as a team. There's no point in saying “I think you should do this” if it's just not practical or feasible on that farm” (V2, youngstock veterinarian).

However, some veterinarians might lack current knowledge about calf rearing. They might be disinterested in youngstock, or struggle to find the time to focus their research and training on calf rearing as opposed to other topics:

“There are some really good vets out there which are really keen on the youngstock side of things and really help their farmers. There are still some vets out there that don't really understand the whole area of calf rearing... they don't always know enough about the preventative methods” (N2, feed company representative).

“It's difficult for mixed practice vets... if you've only got limited hours to do your CPD [continuing professional development] and space in your brain to do reading” (DR1, pharmaceutical company veterinary advisor).

Another participant raised concerns about a lack of awareness of calf-specific legislation among some practicing veterinarians:

“Private vets... don't actually know some of the laws... Top-of-the-range veterinary advisors communicating inaccurate stuff, as well as illegal stuff” (GA1, government veterinary advisor).

According to advisor interviewees, the way in which farm clients engaged with the veterinarian varied, despite their veterinarian being a trusted advisor:

“[Some] clients... see us as part of the team... get us involved in on-farm meetings with nutritionists and other farm consultants whereas other clients would never think of doing that. That's maybe partly down to them not wanting to, but maybe partly down to us not allowing them to recognize that we can have that role” (V5, youngstock veterinarian).

Most farmer participants did not consult the veterinarian about their calf management practices. Several calf rearers believed that they were able to rear calves effectively and deal with basic problems themselves, only consulting the veterinarian in the case of novel symptoms or chronic problems:

“If I see something weird with a calf that I've never seen before then I would usually ask the vet, but I've found just asking the vet for advice on rearing calves then they'll just say the same things that I know anyway so I've never really bothered asking much about that. It's only if I feel it is a more veterinary kind of thing” (F3, calf rearer and farm worker).

Lack of information about calf illness might also contribute to a lack of veterinary involvement in calf rearing on dairy farms:

“If you're not recording any disease incidences, you're not picking up on them and you can't effectively try and make change... If [dad] doesn't perceive there to be a problem then why would he want to call the vet out unnecessarily and pay for the vet's time?” (F4, farmer's son and trainee veterinarian).

Veterinarian participants perceived many farmers to be entrenched in the attitude that the only need for veterinary involvement in calf rearing was in response to problems, rather than developing preventive strategies and investing in calf performance:

“Can the vet help with calf rearing? Not until they're ill. Not as much preventative advice given as I would like to” (V7, farm veterinarian).

“Nothing wrong with the calves, so it doesn't need a vet! Well, there's nothing wrong with a cow producing 8,000 litres, other than you want it to produce 10,000, and you [farmers] involve us in that” (V6, youngstock veterinarian).

The variation in the way in which farm clients consulted the veterinarian about calf rearing was reflected in the services and payment plans offered by veterinary practices. Most farmer participants indicated that routine herd health visits were focused on the milking herd:

“The vet comes [for the weekly routine fertility visit to the adult cattle]... if she's not coming, we don't get her to check [a problem with the calves], but if she is then “oh, these calves are a bit dank [unwell], come and have a look”” (F19, farm manager).

This suggests that farmers avoided consulting their veterinarian about calves when it incurred additional fees. Although some clinics offered a separate youngstock service, farmers had to pay to subscribe to it. Other veterinary practices included calves as part of their preventive herd health approach. Farmers appeared to be most receptive to an inclusive package, where the focus on calves was driven by an enthusiastic veterinarian:

“We're reasonably proactive in our youngstock management so if they didn't ask us [about their calves], we'd ask them... It's all part of a routine dairy herd health visit” (V8, farm veterinarian).

“We have a very proactive vet... We [have a] routine farm visit every fortnight, so that will incorporate looking at calf health. So yeah, so we definitely use him as a learning source” (F9, farm manager).

However, because different members of staff are often responsible for different areas of the farm, including youngstock as part of routine herd health visits could be challenging:

“The person that you're discussing things with may not be aware of the problems, or their perception of the importance is slightly altered to the person who looks after the calves” (V6, youngstock veterinarian).

It was well-accepted that “advice is better value if you act on it” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health), however, implementation of advice on farms could be challenging when working within farm limitations in terms of time, labour and finance:

“It's not rocket science what they're proposing. Keep them clean and warm and dry and feed them properly and they'll grow. But how do you do that when there just isn't the time and there isn't the money?” (V8, farm veterinarian).

“Calves would be one of many issues on the farm and the advice I give might involve cost, either financial costs or labour costs, and that cost is in competition with other costs because [farmers] can't do everything” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health).

It could also be that calf care and uptake of advice was affected by the farmer's personal and mental wellbeing:

“Sometimes it's hard to take advice, especially if you've been doing something for a long time in a way and someone says “oh, that's wrong”. One, it depends how it's presented, but also their mindset. If things are down... and the world just seems to be all against you, then someone telling you “You ought to be doing this instead” isn't gonna encourage people to change. It's gonna just... feel like it's a criticism” (F5, farm manager).

“Sometimes all they want is a friend, they want someone to call in every two or three weeks when they're passing and say hello and have a cup of tea... Part of the time you're an animal doctor, part of the time you're a psychoanalyst” (V8, farm veterinarian).

The quality of the relationship between veterinarians and their clients was believed to be a critical component in motivating uptake of advice:

“Individual advice is so important because you need to understand what motivates your clients and I think as a profession, vets tend to assume it's money, and often it isn't... You need to understand what a farmer's hoping for to be able to advise” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health).

“If a different vet came... I've built up a relationship with this vet, and so he'd have to prove himself, or she, before I would really take his advice over my current one” (F22, herd manager).

However, the quality of advice might depend on the advisor's perception of the client's level of engagement and interest in calves, as well as their ability and willingness to invest in alterations:

“We always tailor our advice to each farm... which might be wrong because that means maybe some people don't always get gold standard advice. Or maybe I tell them that this is gold standard, this is probably what you can do” (V7, farm veterinarian).

Veterinarians might also struggle to remain motivated to advise clients who repeatedly fail to implement recommendations, which could affect a veterinarian's willingness to engage with clients they perceived as uncooperative:

“The vets feel they have such a relationship with their clients... or they've created enough of a stereotype that they start speaking for them... and saying” Oh, they'll never be up for this, we won't bother” (V6, youngstock veterinarian).

“I think sometimes it can be more effort, this may be the wrong attitude, but I think almost more effort than it's worth. Trying really hard somewhere... and then never getting anywhere. Whereas if you invested that time in people that were willing to change, you could have a lot more impact and it's much more rewarding for everybody” (V1, veterinary specialist in cattle health).

The interview findings presented in this paper reflect the complexity of factors affecting calf care on dairy farms, as presented in Figure 1. Interviewees in the current study attributed both use and non-use values to calves which relate to farm performance and personal drivers, respectively (McInerney, 2004). Key use values identified by participants were that replacement heifer calves will become the future milking herd, and rearing costs contribute to overall farm financial efficiency (Boulton et al., 2017). In addition, having sufficient replacements can protect the disease status of farms by limiting the need to purchase cattle (Sayers et al., 2013) and permit judicious selection of cull cows. Although not mentioned specifically by participants, genetic improvement is another important aspect of replacement heifers entering the future milking herd (De Vries, 2017).

Similar to findings from Canadian research which indicated that economic and logistical aspects of marketing bull dairy calves affect their standard of care (Renaud et al., 2017), market value of bull calves was a key consideration for several farmers in this study. This issue is recognised in the industry—the Dairy Cattle Welfare Strategy for Great Britain aims to eliminate the practise of euthanasia of healthy calves by 2023 through adaptations to the market supply chain (AHDB, 2020b). Dairy producers in the UK are striving to reduce the number of lower value dairy bull calves coming onto the market by the strategic use of sexed semen to breed dairy herd replacements (Burnell, 2019). This strategy is particularly pertinent in relation to Jersey and small stature cross-bred dairy cows (Berry et al., 2018), especially in low input dairy block calving systems. The strategy also encourages more sustainable breeding strategies to produce economically viable calves which are more suitable for the beef supply chain, since markets for smaller cattle breeds, like the Jerseys mentioned by participants in this research, are currently lacking in the UK (AHDB, 2020b). These use values were complemented by non-use values, as well as intrinsic and extrinsic motivators: personal ethics and priorities, motivations like job satisfaction and pride, and concern about the public's perception of calf management practises. Ethical obligations, pride and personal responsibility of care have been highlighted as key motivators to maintain good animal welfare in previous research (Leach et al., 2010; Croyle et al., 2019).

Due to the nature of recruitment of participants for this research, interviewees were likely to have an interest in calf rearing and place high value on dairy calves. However, even some of these individuals struggled to invest in their calf management, largely due to competing demands for finite resources (time, labour, and finance) which limited the options available to farm managers to make desired changes (Sutherland et al., 2012). Participants also conveyed concerns about the persistence of historic attitudes which resulted in calves being undervalued on many farms. In sociology, marginalised groups are defined as those who have been pushed to the “margin of society economically, politically, culturally and socially” (Sociology Guide, 2022)—a definition which, based on evaluating the responses from interviewees in the present study, could be repurposed and applied to calves and youngstock on many dairy farms and within the wider dairy industry. As presented in Figure 1, marginalisation of calves on farms often meant that limited investment was made in calf infrastructure, staff, and monitoring of calf performance. On average, replacement heifers that calve at 23–24 months repay the cost of rearing during their second lactation, though farms that exceed the recommended AFC can take up to six lactations to reach the breakeven point; there is a high risk that those heifers exit the herd before making a profit for the farm (Boulton et al., 2017). Due to a lack of long-term data monitoring, financial losses, and potential gains from replacement heifer calves within the overall farm system are likely under-appreciated, ultimately negatively impacting future milking herd productivity and exacerbating the farm's financial situation (Figure 1). In addition, a lack of objective data frustrated advisors and hindered effective preventive veterinary medicine approaches and proactive calf management.

Burton et al. (2021) identified three components for producing good farming practise: (i) innate characteristics, (ii) skills learnt through practise, and (iii) knowledge gained through practise or training—these individual qualities are moderated by the tools and facilities available. In the case of calves, participants in the current study indicated that calf rearers required specific attributes, among them good attention to detail, which requires sufficient time to perform their duties—but calf feeding was often one of several responsibilities assigned to a general farm worker.

Dairy farmers who identified a need for reduced antimicrobial use in calves often included improved staffing—in terms of both quality of labour and the time available to them—as a corrective action (Morgans et al., 2021). Key limitations include the often-under-invested calf infrastructure and limitations in the training, advice and technologies available, as depicted in Figure 1. The habitus that calf rearing is straightforward (Sumner et al., 2018) might contribute to the perception that calf-oriented events and services are unnecessary. This lack of demand affects the prevalence of relevant skills in the veterinary workforce and agricultural college training, ultimately resulting in a dearth of knowledge and support structures to improve calf management, which feeds back into the cultural marginalisation of dairy calves. Participants were hopeful that attitudes were shifting in the industry to focus more on the importance of calf management. Indeed, the financial implications of calf rearing (Boulton et al., 2017) have been publicised by the British industry levy board (AHDB Dairy, 2021) and calf care and youngstock survival has been identified as a key priority for the dairy industry (AHDB, 2020b). However, it is difficult to shift traditional norms (despite evidence supporting the need for change), depending on the strength of attachment to old ideas and practises, availability of the required technology and skills, and the extent to which the change is considered an improvement (Burton et al., 2021).

The perceived value of calves appears to be reflected in the amount of performance monitoring and advice sought regarding youngstock. Where farmer interviewees appreciated the impact of health and growth rate on calves' future performance in the milking herd, they were more likely to be monitoring calf health and growth data. Designated calf rearers were most likely to have the time and inclination to monitor calf performance and valued the ability to objectively assess calf management practises and determine the need to invest time and money for improvements (Sherwin et al., 2016) proactively rather than retroactively observing a problem when rearing targets were not met. Some farmer participants valued the option of having a veterinary technician perform certain husbandry practises (e.g., disbudding) and data monitoring (e.g., weighing calves to record growth rates) and there is now a formal qualification for this role in the UK (Institute for Apprenticeships Technical Education, 2021). There appeared to be less focus on reviewing long-term data to assess the effects of calfhood experiences on future performance (Bach and Ahedo, 2008; Johnson et al., 2017; Baxter-Smith and Simpson, 2020). This meant that on some farms the consequences of poor calf performance are hidden and overshadowed by the immediate and clearly visible penalties resulting from reduced milk supply and/or quality.

Often, participant farmers used information about calf feeding, disease incidents and treatments mainly to aid communication and cohesion between staff carrying out calf protocols; i.e., record keeping that directly influenced their animal care practises rather than perceived as satisfying external regulatory demands (Escobar, 2015; Escobar and Demeritt, 2016). The ease with which calf data could be collected, recorded and monitored was a key concern, and this is an area which could be aided by well-designed and integrated precision livestock technology applications (Rose et al., 2018). Since the time of the interviews conducted in this study, the offering of digital technologies has expanded; for example Breedr (2021) offers a free app to track growth rates and treatments in cattle (including calves) and Smartbell (2021) are currently trialling a sensor-based calf health monitoring and management system to allow 24/7 monitoring of calves to provide actionable insights to farmers. However, the availability of technologies does not guarantee their uptake, and user-centred design is an important consideration for developers to help ensure decision support systems are fit-for-purpose and (perceived as) cost-effective (Rose et al., 2018).

Aside from data monitoring, contact from individuals external to the farm can also help to challenge the farmer's normative frame of reference, or “barn blindness” (Jansen et al., 2009; Croyle et al., 2019). Leaving the farm to attend peer-to-peer learning opportunities like discussion groups and farm walks were popular avenues to gain insight from beyond the farmgate, though the frequency of events was largely dependent on dairy density in the locale, and calves might not feature as a focal topic. The COVID-19 pandemic has propelled the use of webinars and “blended” events which are available both in-person and digitally online, with providers indicating that they wish to continue using so geographical location of events may pose less of a barrier now than in the past (Kindred et al., 2021). Advisors—particularly those with hands-on experience as calf rearers, or a keen interest in calves—were valued as another source of information. However, most of the farmers interviewed did not routinely discuss calf management with their veterinarian, partly to avoid incurring additional costs if not part of a routine herd health visit, and partly because it was not perceived by the farmers as part of the veterinarian's role. Some farmers did not consider expert advice to be necessary, reflecting social norms that calf rearing is straightforward (Figure 1) and requires little deliberation and discussion; similar attitudes were reported from Canadian farmers (Sumner et al., 2018). Veterinary involvement regarding calves generally followed a reactive treatment model in response to disease issues, even when a preventive herd health strategy was applied to the adult herd.

Participating farmers' attitudes toward seeking and implementing advice appeared to sit on a spectrum between proactive individuals who wanted to keep up-to-date with research to do their job to the best of their ability and individuals who lacked the time and/or interest in learning so took a more reactive approach, focusing their efforts on addressing perceived problems. This is consistent with the “types” of farmers previously described by Jansen et al. (2010). Similar to previous research, veterinarians also grouped farmers according to their perceived engagement with the veterinarian and uptake of advice (Richens et al., 2016; Bard et al., 2019). Veterinarians in this study admitted that these perceptions affected the quality of advice given to clients, echoing previous findings that farmers who showed poor levels of engagement and willingness to change had almost been given up on as lost causes (Richens et al., 2016; Redfern et al., 2021). Veterinarians also reported that they would tailor advice to be more attainable for the client, but their assumptions about what is or is not attainable may well be incorrect as veterinarians have been shown to misidentify the expectations and preferences of farmers in provision of herd health management programs (Kristensen and Enevoldsen, 2008; Hall and Wapenaar, 2012). Furthermore, the quality of advice likely depends upon the advisor's interest and motivation to remain up-to-date with the latest research and recommendations regarding calves. In this study, a government advisor indicated that some veterinarians are not aware of basic legislative requirements pertaining to calves, which suggests that not every veterinarian is suited to offering preventive calf health advice, or that more calf-specific training is required. In a previous study, veterinarians who believed that they did not have sufficient knowledge and expertise were less confident to be proactive on farms (Bellet et al., 2015).

Farmers might assume that a trusted advisor, particularly their veterinarian, would identify and inform them of animal care issues on their farm and that if they say nothing, that there is no need for improvement (Croyle et al., 2019). Several veterinary practises in this study did not include calves as part of a comprehensive herd health package. Some practises offered a standalone calf service involving data recording, benchmarking and discussion group with other registered clients, but farmers had to be motivated enough to subscribe and pay for this additional service. This means that an individual—farmer or advisor—must have calf-centric interests; without a driven individual, calves will likely continue to be overlooked, perpetuating the culture of marginalisation of dairy calves.

Several farmer interviewees felt that advice efforts have focused only on highlighting the importance of calf rearing and meeting rearing targets (Palczynski et al., 2020b), with limited information on how to achieve those targets. Furthermore, farmers were keen to gain practical insights that would work within their specific farm context. This desire for practical, tailored, actionable recommendations appeared to reflect the need for farmers to do their best with the resources they have available (in terms of time, infrastructure, finances and mental resilience), which were limited by a variety of external pressures. These limited resources meant that both farmer and advisor interviewees in this study expressed feelings of frustration and perceived lack of control with regards to making positive changes to youngstock management at farm level. This despondency was less evident where designated calf rearers were granted the time and facilities to fulfil a role they were passionate and knowledgeable about. Whilst Figure 1 explores the factors contributing to the marginalisation of calves, it is possible that where calves are prioritised, business performance, job satisfaction and personal wellbeing are improved, resulting in better engagement with information and advice and implementation of recommendations. However, addressing the apparent dichotomy between individuals who recognise the importance of youngstock and prioritise them accordingly, and those who do not will be challenging, considering the numerous interlinking factors at play.