- 1Bristol Veterinary School, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2OKO Ltd., Banstead, United Kingdom

- 3University College Dublin (UCD) School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Many schemes exist which provide assurance on farm animal welfare. However, different standards and protocols mean the level of welfare assured by schemes can be very diverse, potentially hindering food businesses operating globally from sourcing equivalent higher welfare products. This research investigated the rationale for establishing a recognised network of higher welfare schemes from which authentic higher welfare products can be purchased. Nine assurance schemes and seven food businesses were interviewed. Results confirmed the challenge food businesses face in international trade of products from animals reared to a definable welfare status, due to the lack of recognised equivalence of different assurance schemes. Results provided evidence for international interest in an alliance of higher welfare schemes to provide standardisation of higher welfare, as a solution to this challenge. As a result, a working model of such an alliance was refined and the alliance was launched as “Global Animal Welfare Assurance” (GAWA).

Introduction

Certification or assurance schemes are schemes which certify, or provide assurance on, the conditions of farm production, including the level of welfare to which animals are reared (Hubbard, 2012). The assurance of welfare is mainly based on the provision of certain resources (known as input measures) that keep animals safe, comfortable healthy and allow them to meet their behavioural needs: for example, providing hens with a suitable substrate(s) for dustbathing, a behaviour that hens are strongly motivated to perform (Olsson and Keeling, 2005), and therefore suitable litter being a resource that hens want (e.g., Skånberg et al., 2021). According to Dawkins' definition of welfare (“are animals healthy and do they have what they want?”), provision of these inputs improves animal welfare (Dawkins, 2008). Assurance schemes have also started to incorporate animal-based measurements (known as output or outcome measures) i.e., measurements of animal health and behaviour as a way of directly assessing their welfare (Main et al., 2014).

Certification/assurance schemes are often developed and run by private bodies such as industry, farmer or animal welfare organisations (Lundmark et al., 2018). Some consider the origin of such schemes to lie, at least in the UK, with retailers, as a result of pressure from the Food Safety Act introduced in 1990; others argue that it was consumers who were the driving force, due to concerns about food quality standards, including animal welfare; others still claim that livestock producers, mainly the Scottish pig industry, were the original instigators of assurance schemes (reported in Hubbard, 2012). Whatever the origin, by the late 1990s the number of different schemes in the UK had increased greatly, and by 2012 over 20 voluntary schemes existed to assure consumers on standards of food safety, quality, animal welfare and environmental protection (Hubbard, 2012). Not only do numerous assurance schemes exist nationally in the UK, but also all over the world; internationally the number of different schemes is vast.

Assurance schemes provide standards for farming conditions that have the potential to improve welfare. Through their auditing process of every farm member, assurance schemes ensure at the very least that minimum legislative standards and codes of recommendation are met. As although legislative standards are mandatory, policing of this legislation only occurs on a subset of farms, for example if there have been any complaints about the welfare of the livestock Animal Plant Health Agency (2016). This leads to the potential for cases of non-compliance with legislation. Compliance with legislation is a particular issue in some areas of legislation in the UK and the EU, for example the provision of sufficient and suitable enrichment in pigs, and adhering to the ban on routine tail docking (Nalon and De Briyne, 2019). KilBride et al. (2011) demonstrated that members of assured or organic schemes are more likely to comply with animal welfare legislation than those that are not certified members. Likewise, Clark et al. (2016) identified that farmers in private assurance schemes showed better compliance with animal welfare regulations than non-members. Mullan et al. (2016) demonstrated that private assurance schemes introducing welfare outcome assessment into their standards led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of feather loss (compared to before animal outcomes such as feather cover were monitored). Extrapolating their results predicted an extra 1.8 million fully feathered cage-free birds in the UK thanks to these assurance schemes, alongside wider industry initiatives to improve feather cover. Furthermore, an introduction of assessor training in the schemes to encourage farmer behaviour-change was associated with over half the farmers reporting they had made on-farm changes to improve bird welfare (Mullan et al., 2016).

Whilst it is therefore positive that many assurance schemes exist, as they help to increase the proportion of farmed animals with improved welfare, the number of different schemes can lead to confusion. Because schemes operate to different welfare standards, as well as different inspection, certification and accreditation systems (Main et al., 2014), the level of welfare assured by these different schemes can often be very different. The UK's Farm Animal Welfare Council (2009) states that many consumers are motivated about animal welfare but are confused with information that is provided and are therefore uncertain when making their choice between products.

It is not only consumers that can become confused by the different assurance schemes available, but also businesses (i.e., any organisation sourcing food and providing it to the public), especially when operating on an international level. As explained by Main et al. (2014), “there is no internationally agreed mechanism for recognising the equivalence of animal welfare schemes. The lack of standardisation is a complication in international trade as the lack of clarity may impede demand for products from animals reared according to specified levels of welfare… Whilst an international framework continues to be absent it is difficult for the food industry to trade products with a definable welfare status when different countries use different private certification schemes. In contrast the agreed international frameworks available for the organic sector have facilitated significant international trade in organic products.”

As a solution, Main et al. (2014) suggested that “voluntary agreements between interested scheme owners in different countries could form a basis for defining the mutual recognition of ‘higher’ welfare schemes. Similar approaches have been used in other sectors. For example, a voluntary agreement between organic certifying bodies has led to a Global Organic Textile Standard which enables mutual recognition of schemes in different countries.”

This idea led to several welfare assurance schemes, as well as academics, coming together in 2017 to form such a voluntary working group. Originally called the “Global Federation of Higher Animal Welfare Assurance,” the founding members of this group were RSPCA Assured (UK) along with its parent charity, the RSPCA; the Soil Association (UK); Beter Leven (NL); SPCA Blue Tick (NZ); Global Animal Partnership (USA) and until late 2019, Animal Welfare Approved (USA). These welfare assurance schemes are considered as higher welfare schemes in that their standards go above and beyond legal requirements for animal welfare in their respective countries, as well as including welfare outcome measures in addition to input measures, something that is considered best practise in welfare assurance (Main et al., 2014).

The aim of the working group was to define the recognition of authentically higher welfare schemes not by using their own standards as the benchmark, but by developing an evidence-based framework of higher welfare. These frameworks, for each of the major farmed species, were created by scientific advisors in the form of academics from the University of Bristol (UK) and the Royal Agricultural University (UK).

The frameworks for higher welfare standards cover the reduction of negative experiences through promoting health, avoiding mutilations, measuring welfare outcomes, and welfare at slaughter, as well as increasing positive experiences through increasing opportunities for comfort, confidence, interest and pleasure. Requirements within each of these categories that were above EU/UK legislation and had an evidence base of improving animal welfare were taken as the defining level of higher welfare standards. The frameworks can be viewed online: www.gawassurance.org/higher-welfare-frameworks.

The idea behind these higher welfare frameworks was that if other assurance schemes could meet the requirements set out by the frameworks, then they could become a member of this network. By establishing a recognised network of higher welfare schemes from which authentic higher welfare products can be purchased, the vision is to create a global source of such products which could increase demand by improving identification, availability and supply. In this way the working group hopes to achieve its ultimate mission of increasing the proportion of animals around the world farmed to higher welfare standards.

This working group received funding from the UK's Farm Animal Welfare Forum (FAWF) to support initial development. FAWF is a not for profit group of organisations concerned with improving farm animal welfare: the University of Bristol's Animal Welfare and Behaviour Group, the British Veterinary Association, Compassion in World Farming, the Food Animal Initiative, the Royal Agricultural University, RSPCA, the Soil Association, and World Animal Protection. As part of this development, the group wished to engage with other assurance schemes and food businesses to gain an understanding of how beneficial they would find the existence of such an alliance, what the potential advantages and disadvantages could be, and of two potential operating models of the alliance, which they would find most useful. In addition, although the lack of standardisation of welfare assurance schemes is considered a complication for businesses trading livestock products internationally, there are no published studies to confirm this.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to examine whether international trade in animal products produced to a defined level of animal welfare is a challenge for food businesses, and to investigate the potential of an alliance of higher welfare schemes meeting a science-led definition of higher welfare as a mechanism for overcoming this challenge. The study also aimed to assess whether welfare assurance schemes worldwide saw any benefits of, and their interest in, becoming a member of such an alliance, as well as their ability to become a member based on time and resources available. Finally, the study aimed to refine the business model proposed by this alliance, and determine a suitable name, based on feedback from these stakeholders.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of Bristol's Health and Life Sciences Faculty Research Ethics Committee. Participants were given an information sheet informing them about the study and asked to voluntarily consent to their responses being included in a research publication.

Recruitment

Recruitment and interviewing of participants were conducted between August–September 2019.

A member of the research team (ER) contacted potential participants by email and/or phone using details supplied to ER by the alliance's founding members, with the contacts' consent. Potential participants included both farm assurance schemes and food companies, i.e., organisations which could potentially use the services provided by the alliance. Potential participants were given background information about the alliance and the reasons for conducting the research. They were also informed about the time commitment of the interview and confidentiality of the conversation, in that individuals and organisations would not be identified as having taken part in the research, and that data would be shared on an anonymised, aggregated basis only. Based on this information, the potential participants could decide whether to participate.

Interview

The research team (ER and SM) consulted a representative (JR) from a specialist agency OKO (www.oko.agency) with expertise in market research, to design the interview questionnaire (designed by JR). A full copy of the questionnaire is available as Supplementary Material.

Interviews were conducted by the same member of the research team (ER) either by phone or internet conferencing and lasted around 45 min for food businesses and 1 h for assurance schemes. Interviewee responses were collected using an interview capture form designed by OKO (JR).

A thematic analysis was carried out by a member of the team from the specialist consultancy OKO (JR). This is a method of analysing qualitative data by identifying and interpreting patterns of meaning (themes). These key themes are presented, along with some descriptive background information on the schemes and food companies that participated Descriptive quantitative data (average scores and number of participants in each score category) were also produced for questions where participants were asked to score their interest in the alliance and how useful they find the concept of the alliance.

Interview Structure

Descriptive Data

Questions were asked to gain an understanding about the operating location(s) of each organisation, and for assurance schemes, the size and income of the organisation, and therefore their capacity in terms of time and resources to become members of the alliance.

Welfare Standards

Assurance schemes were asked the standards they apply in their scheme and how they develop them. For food businesses, questions were asked on the welfare standards applied in their supply chain.

Key Challenges

Assurance schemes were asked the key challenges they face e.g., in attracting new members to choose them over other assurance schemes, in order to assess potential membership benefits to these schemes.

Response to Concept

The concept of the alliance was proposed to all interviewees as follows:

“A federation of animal welfare schemes with a common set of global standards. Schemes can become a member and implement these global standards and/or benchmark themselves against these standards. Member companies will be able to understand clearly how the standards of the schemes they belong to benchmark on a global basis.”

Based on this proposal, the interviewee was asked to give their feedback on the potential benefits and barriers to being part of such an alliance, as an open-ended question. They also were asked to score a list of potential benefits, on a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is very important and 1 is not important. The order of the list was randomised for each interview to control for response (order-effects) bias. For assurance schemes, this list was:

• Having access to scientific expertise in animal welfare.

• Having access to the latest global trends in animal welfare.

• Ensuring that your standards are based on the latest scientific research in animal welfare and behaviour.

• Being able to benchmark your scheme against other schemes internationally.

• Being able to identify ways in which you can improve standards on your own scheme.

• Being able to share ideas/best practise on how to operate and grow a scheme.

• Being able to demonstrate where your scheme's standards fit with a global standard.

• Being able to develop/improve standards for species your scheme doesn't currently focus on or cover.

• Providing you with a clear path and goals for improving standards on your scheme to achieve the highest welfare standards.

• Giving your scheme greater credibility.

• Attracting new farmer members to your scheme.

• Associating your scheme with the highest standards in animal welfare.

• Helping your scheme compete more effectively against other schemes.

For food businesses, this list was:

• Being able to select schemes from an approved global list of federation members.

• Being sure that the schemes you are a member of/ might wish to join apply common animal welfare standards.

• Ensuring that schemes you are a member of/might wish to join apply the highest possible animal welfare standards.

• Knowing that the schemes you are a member of/might wish to join have global recognition and credibility.

• Being able to clearly demonstrate how the animal welfare standards you apply fit within a global standard.

• Knowing that your company is applying the same/similar standards in each country it operates in.

• Knowing that the schemes you are a member of/might wish to join have standards for all species.

The participants' interest in becoming a member of the alliance was gauged with the following question:

For schemes: Overall how interested would you be in becoming a member? (In principle, put aside the issue of cost for the moment) (rate on a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is very interested and 1 is not interested).

For food companies: What could be the benefits to your company of the existence of a global animal welfare federation like this?

Response to Model Options

Two potential models on which the alliance's higher welfare frameworks and membership criteria could be structured were presented, as follows:

OPTION A: The federation would operate a single set of higher animal welfare standards for each species. Only schemes which reach these higher standards are able to join the federation. The federation acts as a membership organisation for schemes globally which operate higher animal welfare standards.

OPTION B: The federation would operate tiered membership (for example Gold, Silver, Bronze). schemes can join the relevant tier for each species. The federation acts as a membership organisation for schemes globally, encouraging them to improve their standards and climb up the tiers (e.g., from Bronze to Silver to Gold).

The order of these options was alternated for each interview to control for response (order-effects) bias. Interviewees were asked to give their feedback on the potential benefits and barriers to being part of such an alliance, and their interest in becoming a member, for each of the business models.

Cost of Membership

Schemes were asked about their anticipation of the monetary cost for joining such an alliance.

Name of Alliance

Finally, all participants were asked an open question on their opinion of the name “Global Federation of Higher Animal Welfare Assurance,” and which words in the name they felt were important within this name to convey the purpose of the alliance.

Results and Discussion

Schemes

Descriptive Data

Of the nine schemes participating in the research, two were operating in the UK, one in Australia, one in New Zealand, one in Germany, one in Austria and one in Switzerland; one scheme operated in Austria and Germany, and one in Germany, Austria and Luxemburg. Three schemes were run by an NGO, one by a not for profit farmer organisation, and 5 were private sector organisations. Schemes employed between 8 and 61, although one scheme employed 330 individuals (median 27.5, missing data for one scheme). The annual income ranged from ~20,000 to 14,000,000 Euro (converted from local currency), although the scheme with 330 employees had an annual turnover of 221,000,000 Euro (median 2,500,000 Euro). The types of members of these schemes ranged from producers/farmers (either directly or indirectly via processors/retailers), processors, retailers (which were then licenced to use the scheme's accreditation label) and food services. Membership size ranged greatly, from 5 to 48,000 members (median 1,250 – missing data from one scheme). Three schemes were organic, one scheme had a sustainability focus, and one scheme included an emphasis on environmental protection, food safety and traceability; four schemes had animal welfare as their only focus.

Thus, most schemes were relatively small organisations with limited resources that would likely need strong arguments to justify a return on investment (ROI) if paying a membership fee to join a higher welfare alliance.

Welfare Standards

The species covered by the nine schemes' standards was very mixed, from single species to all major farmed species. For the schemes within Europe, animal welfare regulations (e.g., EU regulations) provide a baseline for the standards. In Australia and New Zealand, in-country regulations and commercial standards were seen to be lower than EU regulations. These schemes had a sense of being disconnected from the rest of the world in terms of the level standards; the scheme in Australia felt their standards may not be able to meet a globally unifying standard of welfare based on European standards because these are higher than the reality in Australia. The New Zealand scheme felt that their standards were higher than those of Europe, due to the unique climatic factors and land availability of New Zealand enabling them to give animals increased opportunities for good welfare beyond what is practically achievable in Europe.

The schemes' standards were produced via collaboration e.g., with producers, processors, retailers, universities, vets and vet groups, and industry groups. There was reference in some cases to looking at standards in other countries and informal discussions with other schemes. All schemes' standards have developed and continue to develop over time, via ongoing updates through research and practical experience. There was some evidence of international benchmarking of standards (three examples of benchmarking against other schemes internationally, and one example of a joint scientific inter-country project).

The overarching theme emerging from this part of the interview was that welfare standard development approaches are collaborative and improved over time, with some benchmarking against other schemes in Europe.

Key Challenges

Ensuring inclusivity and ways to bring the whole farming marketplace along with them, rather than allowing farmers to “drop out,” developing standards that ensure good welfare whilst being practically applicable within the realities of the commercial environment, providing a return on investment (ROI) argument for farmers, processors and retailers, and challenging consumer expectations of cheap food, were key challenges identified by the participants. Thus, it emerged that most schemes were attempting to strike a balance between stretching standards towards higher welfare and encouraging participation of the marketplace. Other key challenges identified were how to consistently apply standards when audits are conducted independently, ensuring the skills and competences of inspectors and inspection regimes, and weather and environmental issues (e.g., severe drought episodes in Australia).

In terms of attracting members to join their scheme, the key challenges identified by participants were: providing clarity to potential members as to whether an ROI exists; concerns from potential members that the standards are too high and therefore difficult to achieve; the costs of joining and operating to the standards being too high; the costs and effort of being audited; and, in the UK, political uncertainty. The key reasons that members choose to join identified by the participants were: trust in and credibility of the scheme; consumer demand and marketplace pressure for higher welfare; corporate social responsibility; the potential ability to charge a premium; and retailer requirements, or farmers “forced” to join by a processor.

The main conclusion drawn from this part of the interview was that schemes need to make a ROI justification argument to potential members, and credibility is key in supporting this.

Finally, in terms of competition as a key challenge for schemes, there appeared to be a mixed picture: some perceive a complete lack of any competition; some perceive competition coming from schemes with parallel purposes e.g., organic schemes; some see some competition provided by a range of niche, often species-specific schemes; one participant identified competition from retailers setting up their own schemes. Thus, it seemed that although the participating schemes may be competing with other schemes, they tend not to see themselves in a competitive marketplace – this may be because there is common cause (i.e., improving animal welfare).

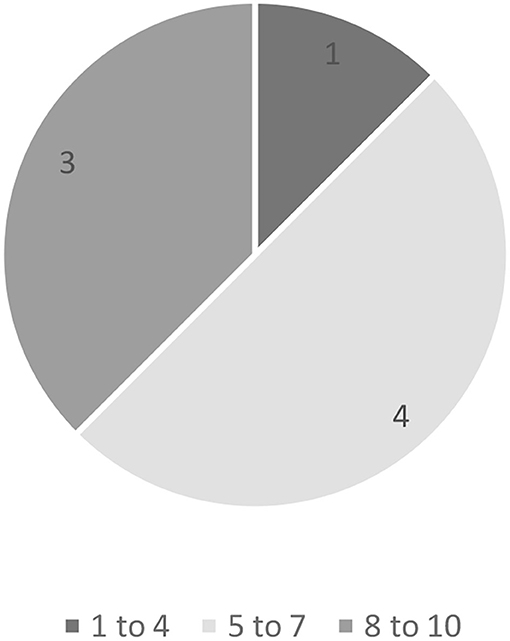

Response to Concept

Schemes scored (out of 10) how interested they were in joining the alliance; Figure 1 shows the number of schemes in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10). One scheme felt unable to answer this question based on the information provided. The average score given was 6.1. This suggests an overall positive level of interest in being part of the alliance.

Figure 1. Number of schemes in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10, where 10 is the maximum score) illustrating how interested they were in joining the alliance.

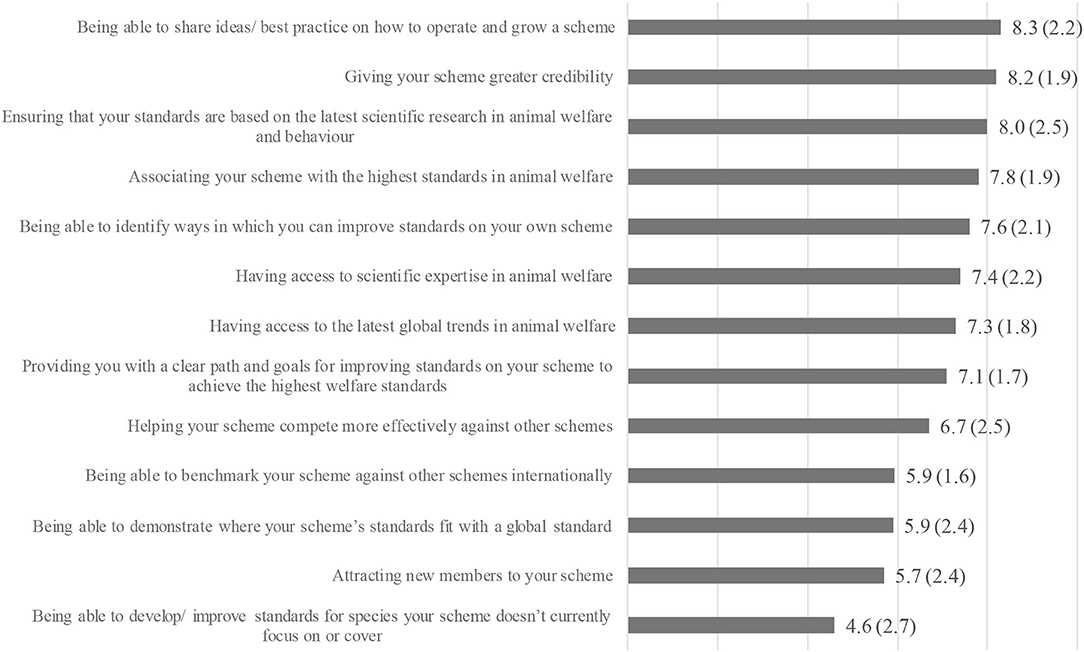

The participants rated the importance of potential benefits of being a member of the alliance. The mean score given for each of the listed potential benefits are illustrated in Figure 2 along with the standard deviation of the scores. This shows that the key benefits seen by schemes in such an alliance are sharing ideas and best practise, accessing relevant scientific research, and building credibility. This willingness of farm assurance schemes to collaborate, and the motivations behind this willingness, provide an interesting insight.

Figure 2. Schemes' mean ratings (out of 10) and standard deviation (in parentheses) of the importance of potential benefits of being a member of the alliance.

The conclusions drawn from this segment of the interview were that the response to the idea of a global federation is overall positive, although the conversations suggested this was often driven by a desire not to be “left out of the loop.” Schemes see the most benefit to the alliance in sharing best practise and expertise. Although schemes saw globally-unifying principles for standards in animal welfare are potentially useful, there was some concern about local applicability, due to country differences in factors such as climate, land availability, farming approaches, consumer attitudes etc.

Response to Model Options

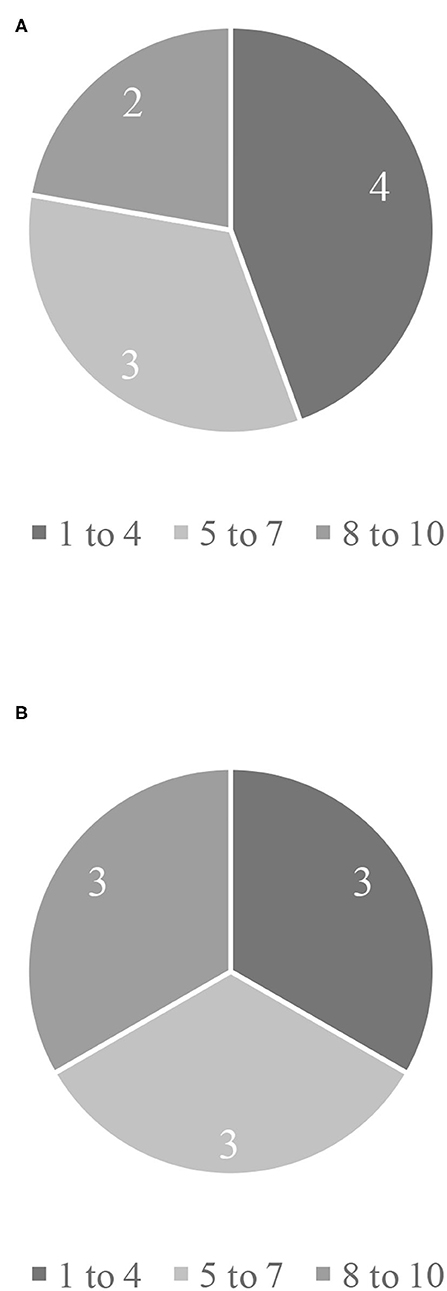

Option A (the single set of higher welfare standards model) was the preferred model for four of the schemes, and option B (the tiers of increasing welfare model) was preferred by five schemes.

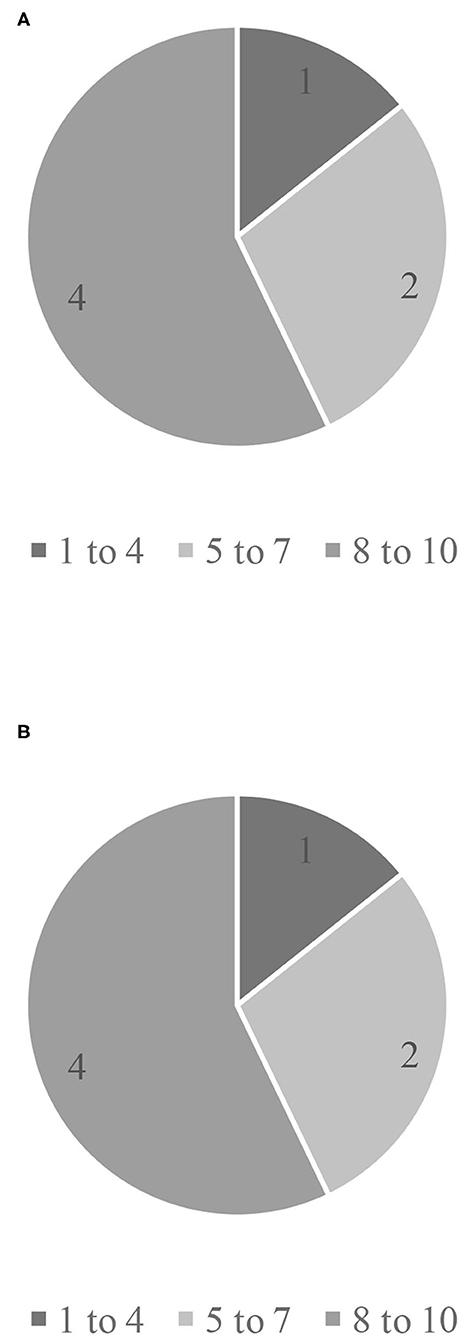

Figure 3 shows the number of schemes in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10) based on the score they gave (out of ten) for their interest in joining the alliance if it were based on either model. The average scores were 5.4 for option A and 5.7 for option B. This suggests that there was no strong preference between schemes for either option.

Figure 3. Number of schemes in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10, where 10 is the maximum score) illustrating how interested they were in joining the alliance if it were based on either model: (A) Option A: single set of higher welfare standards or (B) Option B: tiers of welfare standards.

The participants saw the following benefits to option A (a single set of higher welfare standards):

• Clear and simple

• Can act as aspirational target for schemes

• Can act to make the biggest difference to animal welfare in terms of the level of their welfare

They had the following concerns about option A:

• Potentially exclusive, as either the standard may be too high for individual countries or schemes, or the standards may be lower than those being used currently

• One set of standards may be limited as an incentive for schemes to improve standards

They saw the following benefits to option B (tiers of welfare standards):

• More open and inclusive

• The focus of this model appears to be on continuous improvement

• Can act to make the biggest difference to animal welfare in terms of affecting a larger volume of the market, and so more animals

They had the following concerns about option B:

• Tiering is confusing, difficult to develop and not a simple message to communicate

• It may be difficult or inapplicable to climb tiers in certain countries, or no incentive to do so

Overall, it seemed that schemes were looking for a balance between inclusivity and simplicity. The schemes felt that a single standard is likely to be most workable, and that tiers could be more inclusive, but also more complex.

Cost of Membership

The objective of a membership fee for the alliance is to cover the administrative costs e.g., processing applications, providing feedback on applications, responding to queries, facilitating meetings within the alliance and with external parties, etc. Most participants were unable to suggest a cost for membership. When asked how interested, on a scale of one to ten, they would be in joining the alliance if the annual fee was 10,000 USD (an arbitrary figure chosen to get a sense of willingness to pay for membership of the alliance), the average score was 3.5, based on six responses; three participants felt unable to answer this question, but generally described this cost as prohibitive. Most were concerned about how they would justify this cost, and if this cost would be passed on to members. Some participants also considered the additional internal non-monetary costs of being a member in terms of time commitment, which could potentially be prohibitive to low-resource organisations.

Food Businesses

Descriptive Data

Of the seven food businesses interviewed, three were retailers, two were processors and one a consumer goods company. One was a public procurement organisation, and therefore not a commercial enterprise, but still a potential end-user of the alliance's services in that the organisation seeks to source higher welfare animal products. All organisations were based in Europe: two in the Netherlands, one in the UK, and one in Austria. One operated in the Netherlands and Belgium, one in the Netherlands and Germany, and one in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France and Poland.

Welfare Standards

The organisations either applied their own standards or adhered to the animal welfare standards of a scheme recognised in that country; they expected suppliers to adhere to this standard set, and could demand this. Retailers assessed schemes based on benchmarking of standards against their requirements. They reported benchmarking within their own supply chains, but only limited benchmarking against schemes they don't belong to. Supply chains were found to consist of a mixture of closed chains, designed to ensure quality and consistency, and open market purchasing. Processors and retailers were often working to meet consumer demands for local meat. Participants were found to have some access to animal welfare expertise directly, for example via universities, vets, government and NGOs. Consumer-facing processors and retailers reported taking into account market sentiment on animal welfare. There was some membership identified of global organisations on sustainability, environment, organics and medicines, but no membership of global animal welfare initiatives. There was one mention of GlobalGAP (n.d.) as a global standard for food safety and sustainability, which also includes voluntary global animal welfare standards.

A key conclusion drawn from this part of the interview was that food businesses get advice from a wide range of sources, and assimilate this into an animal welfare strategy that balances science with consumer sentiment.

A further theme drawn from the discussion on welfare standards was that animal welfare is important to these organisations, but there are some significant challenges in driving this agenda. These could be categorised into:

Cost

1. Organisations must prove the value of increased animal welfare whilst maintaining cost competitiveness.

2. They must also ensure that consumers recognise and pay for higher welfare.

Complexity

3. Supply chains are complex, especially when dealing with international supply chains.

4. Organisations are forced to work with multiple assurance schemes, for example for different species, countries, purposes (e.g., animal welfare, sustainability, quality control) as well as their own standards.

5. Animal welfare is not the only issue organisations need to take into account, and therefore must take a holistic view of animal welfare alongside sustainability, environmental and food safety/quality issues.

Consistency

6. Organisations find it hard to make comparisons between countries in animal welfare standards, due to differences in geography, culture, farming practises, etc.

7. Even when the same scheme is used in different countries, outcomes from the scheme's standards may not be the same, due to differences in auditing and the factors outlined in the point above.

Change

• Organisations encounter resistance to change amongst producers; for example, producers feel that if they agree to change their practises, they are effectively admitting they have been treating animals badly up until that point.

• The decisions on whether to work with welfare assurance schemes are rationally based, often focused on the extent to which membership will create leverage with consumers. Key reasons for joining a scheme included: trust and credibility of a scheme; consumer awareness of that scheme; the scheme having similar standards to their own; the ability to collaborate on the standards development within that scheme; and the scheme being the only in-country option for welfare assurance. Key objections to joining a scheme were how the schemes standards fit with their own standards, and proving an ROI, as discussed above.

Points 3, 4, 6, and 7 in particular highlight the challenge food businesses face in sourcing products produced to a defined level of animal welfare.

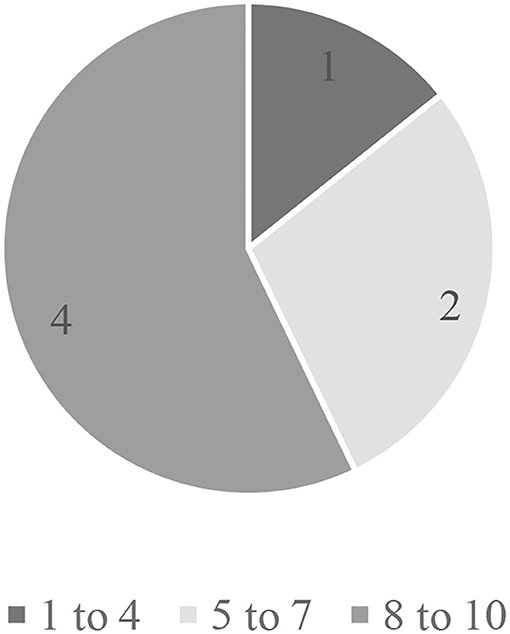

Response to Concept

Food businesses scored (out of 10) how useful it would be for their company to be able to select from animal welfare schemes which are members of such an alliance; Figure 4 shows the number of schemes in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10). The average score was 7.0, suggesting very positive interest in the existence of the alliance.

Figure 4. Number of food companies in three score categories (1–4, 5–7, and 8–10, where 10 is the maximum score) illustrating how useful it would be for their company to be able to select from animal welfare schemes which are members of an alliance of higher welfare schemes.

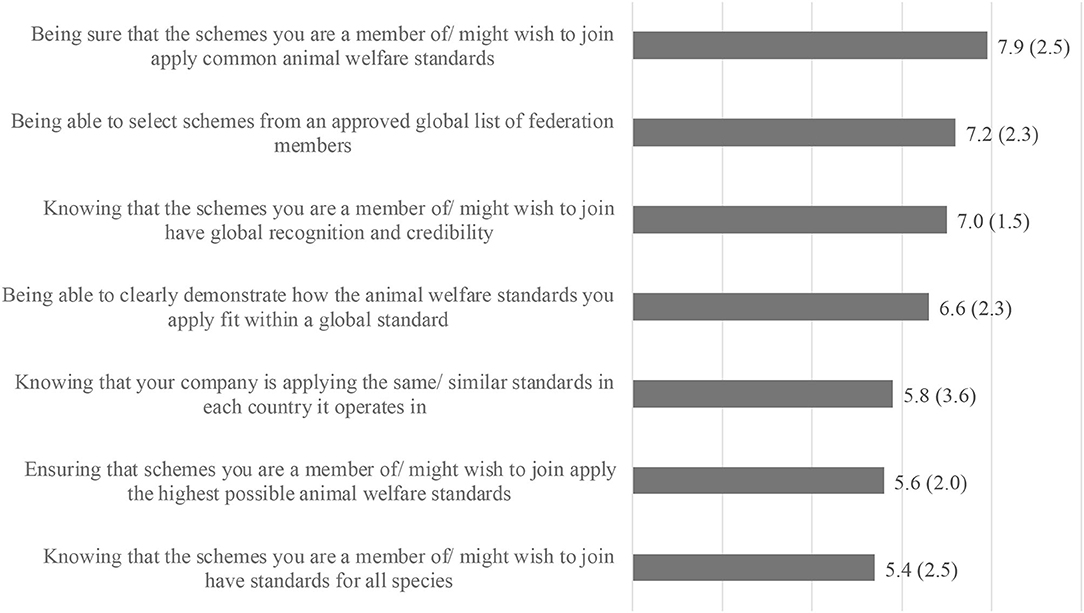

The participants rated the importance of potential benefits of selecting assurance schemes that are a member of the alliance. Figure 5 illustrates the mean scores and standard deviation of the scores. The key benefit for food businesses appears to be the ability to demonstrate consistency in animal welfare on a global basis; although somewhat counterintuitively, they rated ensuring application of the same or similar standards in each country they operate in as less important, although it may be that participants felt that standardisation across all countries was unrealistic rather than unimportant

Figure 5. Food businesses' mean ratings (out of 10) and standard deviation (in parentheses) of the importance of potential benefits of selecting assurance schemes that are a member of the alliance.

Thus, the response to the idea of a global federation was mainly positive, and food companies saw a benefit of the alliance in providing global consistency in higher welfare, but there was some doubt about how it will work “on the ground” according to local realities. Participants also saw a need for integration of the alliance within the wider sustainability agenda.

Response to Model Options

Option A (the single set of higher welfare standards model) was the preferred model for four of the seven food companies, and option B (the tiers of increasing welfare model) was preferred by three out of seven. Figure 6 shows the score (out of ten) for interest in joining the alliance if it were based on either model. The average scores were 6.6 for option A and 6.9 for option B. As with the schemes, this suggests that there was no strong preference for either option over the other.

Figure 6. Food businesses' score (out of ten) for interest the alliance if it were based on either model: (A) Option A: single set of higher welfare standards or (B) Option B: tiers of welfare standards.

The participants saw the following benefits to option A (a single set of higher welfare standards):

• Clear and simple, easy to understand model

• The model makes it clear which are the higher welfare schemes

They had the following concerns about option A:

• The potential for schemes they are members of to be excluded or left behind

• How application of the standards will be assessed and controlled

• Emerging markets are likely to be excluded

They saw the following benefits to option B (tiers of welfare standards):

• More open and inclusive

• Ability to benchmark easily, to see where standards fit by country

• Allows continuous improvement

They had the following concerns about option B:

• Tiering is confusing and not a simple message to communicate

Therefore, like the scheme participants, food companies were also split on which was the best operating model (a single standard of higher welfare vs. tiers of welfare). There was some concern around a single standard in terms of setting too high a benchmark, but agreement that simplicity is key. Thus overall, it seemed that like schemes, food companies are looking for a balance between inclusivity and simplicity.

Name of Alliance

Most participants felt that “Global Federation of Higher Animal Welfare Assurance” was too long, and having a simple name and/or acronym would carry more weight. The words that participants selected as important in conveying the purpose of the alliance were “global,” “animal welfare,” and “assurance.”

Key Conclusions

Based on the conversations with both schemes and food companies, the following overall themes and key conclusions emerged.

It appeared that there was global interest in the existence of an alliance of higher welfare assurance schemes providing a globally-unifying definition of “higher welfare” based on scientific evidence. There was also desire for such an alliance, whilst setting the bar for higher welfare internationally, to foster inclusivity and continuous improvement, in order to embrace a larger proportion of the market and so affect the welfare of a greater volume of animals. Participants felt that a framework for higher welfare should focus on broad concepts, rather than prescriptive details, to allow for variability by country and marketplace. Finally, there was recognition that the alliance should foster flexibility in order to have the potential to join forces with global sustainability organisations, and for the welfare standards to be integrated into wider standards on sustainability.

Representatives from food companies confirmed the challenges in global sourcing of animal products to a required standard of animal welfare, and agreed in principle with the idea of globally-harmonised standards for higher welfare as a potential solution to this challenge; however, both groups of participants had concerns about how global standards would work in practise. Both groups agreed that simplicity is key: the role and aims of the alliance must be easy to understand, and a single “bar” defining what constitutes “higher welfare” that could be worked towards may be more effective in practise than tiers of different levels of welfare, which are likely to be more complicated both to develop, audit organisations against, and explain to potential members and end users of the alliance. The concept that was favoured in the tiers approach was the idea of inclusivity and continuous improvement; therefore, the single standards approach should still incorporate a philosophy of inclusivity that enables schemes, farmers, industry, etc. to improve towards a common standard of higher welfare. Representatives from schemes valued a collaborative, inclusive approach in order to help each other develop, and one that takes into account huge variations internationally (e.g., in terms geography, weather, farming approaches, markets, consumers).

Both schemes and food companies were keen to ensure that the definition of higher welfare would be based on scientific research to add credibility; one participant from the food companies group in particular voiced the need for science-based standards rather than standards led by consumer perception of what higher welfare should be. Participants also wanted further information on how the alliance plans to ensure that these standards are being applied on the ground.

Finally, in terms of cost of involvement for schemes, it appears that 10,000 USD is too high and potentially prohibitive as a membership fee, and the level of involvement is an additional hidden cost that needs considering.

Outcome of the Research

Limitations of this study include the small sample size of food businesses and farm assurance schemes, and that the countries represented in the samples are relatively high-income with societies that could be considered to value animal welfare more than other countries. Nonetheless, valid and valuable insights have been gained from the participants which have led to the following conclusions and outcomes.

This research has confirmed the challenge food companies face in international trade of products from animals reared to a definable welfare status, due to the lack of recognised equivalence of different welfare assurance schemes. It has also provided evidence for international interest in an alliance of higher welfare schemes to provide standardisation and determine the authenticity of higher welfare claims, as a solution to this challenge.

Based on these results, the alliance was renamed “Global Animal Welfare Assurance” to keep the message of the group simple, and these were the words identified by stakeholders as important in conveying the purpose of the alliance. In order to achieve a balance between inclusivity and simplicity, two priorities emerging from the interviews, a modified version of “option A” in the interview (the single set of higher welfare standards) was chosen as the working model of the alliance. This model is illustrated in Figure 7. The model has a single set of higher welfare standards, i.e., a single line or “bar” of what defines higher welfare for all the major farmed species, to enable the alliance to communicate a simple message of which assurance schemes are authentically higher welfare (i.e., those that reach this bar). However, this model effectively incorporates a three-tiered approach. Below the red bar denotes what is not higher welfare: this being criteria which either meet or are below UK/EU legislation. Any scheme below this line for any of the species it covers cannot be considered as a higher welfare scheme. In between the red bar and the green bar is a tier of “working towards higher welfare.” If schemes meet the requirement for this tier, whilst they can't become full members of the alliance, they can become affiliated with the alliance (e.g., as “aspirers”) through which they can advertise their commitment to becoming authentically higher welfare (e.g., by adding a message about aspiring membership to GAWA on their website). Not only does this model allow for inclusivity of a greater proportion of assurance schemes, but it also cultivates continuous improvement. To further incorporate a culture of continuous improvement, above the green bar interventions will be outlined that improve animal welfare further and further, which members are encouraged to work towards.

Figure 7. Schematic of the working model of the frameworks for Global Animal Welfare Assurance (GAWA).

The use of scientifically evidenced broad concepts in the higher welfare frameworks, in terms of management and resource provision, will allow for some variability in local applicability according to country conditions, a concern raised by both schemes and food businesses, whilst still ensuring that higher welfare is achieved. In addition, the monitoring and improvement of welfare outcome measures, which are not dependant on local conditions, play a key part in the frameworks. For example, in the GAWA framework for dairy cattle welfare standards, the higher welfare requirements for reducing negative experiences are: standards must provide whole of life welfare assurance; there is farm action to reduce medicine use; no tail docking is carried out; there is no routine dehorning, no disbudding/dehorning or castration is carried out without anaesthesia and long-term post procedure pain relief; welfare outcomes are monitored and there is farm action to improve welfare outcomes to reach a threshold, and maximum transport time is 8 h.

Furthermore, a system of derogations will also be determined, to further allow for variability in local conditions and account for countries where it is not currently possible to meet a higher welfare condition. For example, a higher welfare requirement in the GAWA framework for broilers (meat chickens) is that only slower growing breeds are permitted. Slower growing breeds are not however commercially available in New Zealand and therefore are currently not included in SPCA Blue Tick's standards. The derogation process will require proof that the scheme is actively working towards being able to achieve this condition (e.g., in SPCA Blue Tick's case, lobbying for the availability of slower growing breeds). The higher welfare bar, whilst being science-led, also incorporates what is practically achievable by the founding member schemes, so as not to set the bar so high that no scheme would be able to reach it.

Finally, in response to the concern over differences in auditing of requirements between schemes, GAWA will include requirements for auditing processes as part of the frameworks, to ensure that these standards are being correctly applied in reality. The role of providing training for auditors was also added to GAWA's remit.

The cost of membership is yet to be confirmed but rather than a flat fee, will be adjusted according to each scheme's income and resources, based on participant feedback.

As schemes saw the most benefit to the alliance in sharing best practise and relevant scientific research, the alliance will be marketed as a knowledge sharing platform, and the collaborative nature of the alliance will be emphasised, giving members access to expertise in order to further develop their own standards. Furthermore, as participants saw a need for integration of the alliance within the wider sustainability agenda, an additional service of providing animal welfare expertise to organisations working on other sustainability issues, was added to the alliance's remit. This research is, to the author's knowledge, the first to provide evidence for a shortcoming of the existence of multiple welfare assurance schemes on an international scale; a concern previously raised by others (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 2009; Main et al., 2014) but until now remaining unevidenced. It confirms that while animal welfare is important to this sample of food businesses, these companies are frustrated in their efforts to trade products from animals reared to a definable welfare status on an international scale, due to the lack of recognised equivalence of different assurance schemes. The survey has identified challenges faced by food businesses in driving the animal welfare agenda, which can be categorised under “cost,” “complexity,” “consistency,” and “change.”

This research has also provided evidence for a potential solution to this challenge in the form of an internationally-standardised framework, and therefore definition, of higher welfare and mutual recognition of higher welfare schemes in different countries through membership within a global alliance. The research has helped to refine the working model and aims of such an alliance of higher welfare schemes, in order to establish a recognised network of such schemes and so an easily-identifiable global source of authentically higher welfare products. In this way, the alliance has moved closer towards its mission of increasing the supply of and demand for higher welfare products, and so the proportion of animals farmed to higher welfare standards around the world.

At the time of writing, GAWA has been launched as a Community Interest Company (CIC) registered to the UK and is accepting new members. More information can be found at: www.gawassurance.org.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because dataset contains identifiable data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Elizabeth Rowe, bGl6emllY2xhcmVyb3dlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Bristol's Health and Life Sciences Faculty Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SM and ER conceptualised the research. JR designed the interview process and analysed the results of the interviews. ER carried out the interviews and wrote the manuscript. SM and JR edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

ER and JR's time were funded by the Dutch animal welfare assurance scheme Beter Leven.

Conflict of Interest

JR was employed by the company OKO Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this market research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2021.665706/full#supplementary-material

References

Animal Plant Health Agency (2016). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/animal-welfare-on-farms-inspection (accessed October 28, 2021).

Clark, C. C. A., Crump, R., KilBride, A. L., and Green, L. E. (2016). Farm membership of voluntary welfare schemes results in better compliance with animal welfare legislation in Great Britain. Anim. Welfare 25, 461–469. doi: 10.7120/09627286.25.4.461

Dawkins, M. S. (2008). The science of animal suffering. Ethology 114, 937–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01557.x

Farm Animal Welfare Council (2009). Farm Animal Welfare in Great Britain: Past, Present and Future. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/319292/Farm_Animal_Welfare_in_Great_Britain_-_Past__Present_and_Future.pdf (accessed October 28, 2021).

GlobalGAP. (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.globalgap.org/uk_en/ (accessed October 28, 2021).

Hubbard, C. (2012). Do farm assurance schemes make a difference to animal welfare? Vet. Rec. 170, 150–151. doi: 10.1136/vr.e847

KilBride, A. L., Mason, S. A., Honeyman, P. C., Pritchard, D. G., Hepple, S., and Green, L. E. (2011). Associations between membership of farm assurance and organic certification schemes and compliance with animal welfare legislation. Vet. Rec. 170, 152–158. doi: 10.1136/vr.100345

Lundmark, F., Berg, C., and Röcklinsberg, H. (2018). Private animal welfare standards—Opportunities and risks. Animals 8:4. doi: 10.3390/ani8010004

Main, D. C. J., Mullan, S., Atkinson, C., Cooper, M., Wrathall, J. H. M., and Blokhuis, H. J. (2014). Best practice framework for animal welfare certification schemes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 37, 127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.03.009

Mullan, S., Szmaragd, C., Cooper, M. D., Wrathall, J. H. M., Jamieson, J., Bond, A., et al. (2016). Animal welfare initiatives improve feather cover of cage-free laying hens in the UK. Anim. Welfare 25, 243–253. doi: 10.7120/09627286.25.2.243

Nalon, E., and De Briyne, N. (2019). Efforts to ban the routine tail docking of pigs and to give pigs enrichment materials via EU law: where do we stand a quarter of a century on? Animals 9:132. doi: 10.3390/ani9040132

Olsson, I. A. S., and Keeling, L. J. (2005). Why in earth? Dustbathing behaviour in jungle and domestic fowl reviewed from a Tinbergian and animal welfare perspective. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 93, 259–282. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2004.11.018

Keywords: higher welfare products, animal welfare, welfare assurance, welfare certification, global food system

Citation: Rowe E, Rix J and Mullan S (2021) Rationale for Defining Recognition of “Higher Animal Welfare” Farm Assurance Schemes in a Global Food System: The GAWA Alliance. Front. Anim. Sci. 2:665706. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2021.665706

Received: 08 February 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021;

Published: 11 November 2021.

Edited by:

Harry J. Blokhuis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenReviewed by:

Anette Wichman, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenDavid Arney, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Estonia

Copyright © 2021 Rowe, Rix and Mullan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth Rowe, bGl6emllY2xhcmVyb3dlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Elizabeth Rowe

Elizabeth Rowe Jeremy Rix2

Jeremy Rix2 Siobhan Mullan

Siobhan Mullan