95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anesthesiol. , 19 February 2025

Sec. Critical Care Anesthesiology

Volume 4 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanes.2025.1460909

Introduction: Nurses and physicians can influence the patient's will in various ways during intensive care treatment, whereby certain strategies fall into the realm of formal and informal coercion. Understanding and addressing these dynamics is crucial for humanized intensive care which promotes patient autonomy, minimizes coercion and fosters positive support strategies. We aimed to investigate which possibilities and forms of (un)intentional influencing and overriding of the patient's will between “formal” (physical restraint, sedation) and “informal” (psychological measures such as deception and threats) coercion are used in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Method: In this qualitative study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 nurses and physicians working in different German ICUs between September 2022 and February 2023. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling technique to support the heterogeneity of the sample. Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis.

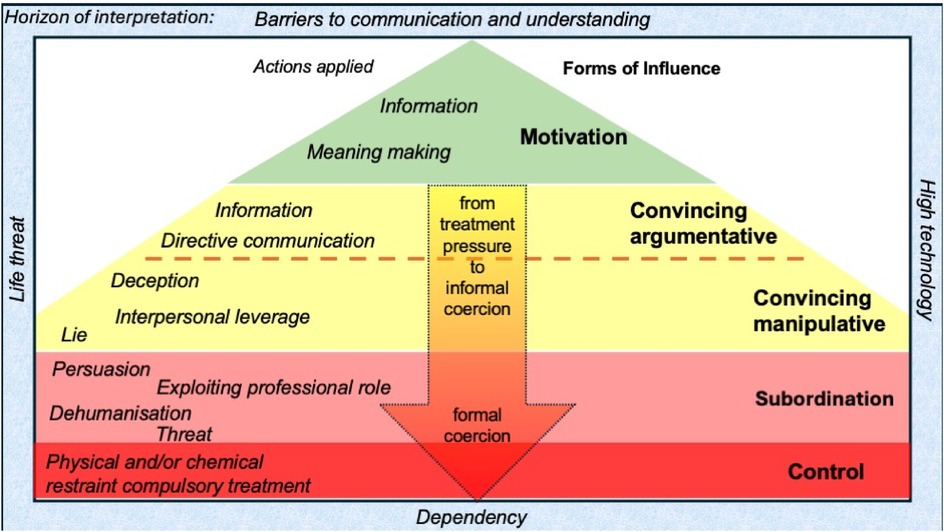

Results: Five different forms of influence aiming at motivation, convincement (argumentative or manipulative), subordination and control were identified, along with different communicative practices (e.g., information, deception, lie, persuasion, threat) and other strategies (e.g., physical restraint) to reach the corresponding goal. The different forms are used simultaneously or alternately, i.e., they cannot be categorized in terms of an escalation hierarchy. The boundaries between support, informal and formal coercion are blurred, sometimes subtly.

Discussion: In the ICU nurses and physicians influence the patient's will using many strategies; some despite moral and legal concerns. Further research is needed to determine the frequency of informal coercion in larger samples and different intercultural contexts.

Patient autonomy and well-being, the cornerstones of modern medicine, are often compromised in the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the severity of illness, a lack of decision-making capacity, and dependence on life-sustaining technologies (1, 2). However, this does not mean that the patients have no will (3). Instead, it is precisely in this situation that the wishes, demands, needs and interests of the patient are important as an expression of their will. Patients impressively describe their ambivalent experience of dependency and their relationship with intensive care staff (4). They report feelings of being unheard and disregarded (5–7), resulting in anxiety, frustration, stress and helplessness, as well as a loss of self-determination and dignity and feelings of guilt (8–11).

The possibilities and forms of influencing and overcoming the patient's will, such as “formal” and “informal” coercion, have been studied mainly in psychiatry.

Overriding the patients' will with formal coercion [e.g., physical and chemical restraint, compulsory treatment (12, 13)] is regulated by law and accompanied by an intensive debate (14–16) and recommendations from professional societies (17). The prevalence of physical restraint in the ICU is high (18) and patients confirm that they have experienced formal coercion (19, 20). Consequences of physical restraint range from increased delirium and anxiety to post-intensive care syndrome and many more (20, 21). For the healthcare professionals the conflict between beneficence and respect for autonomy causes moral distress, resulting in poorer patient care, burnout and an intention to leave the profession (21, 22).

The use of communicative strategies to influence patients' decision-making and improve their adherence to recommended treatment – which is referred to as informal coercion, treatment pressure or psychological pressure (23, 24) – has rarely been studied in the ICU context. However, a few studies reveal that patients in the ICU also experience their will being influenced and/or overcome (19). There are differing opinions and approaches regarding when these influencing strategies become informal coercion (24–26). Szmukler and colleagues describe a hierarchy of treatment pressure in psychiatry, with the levels of persuasion, interpersonal influence, incentivisation, threats and coercive treatment (27). Rugkasa et al. (28) as well Pelto-Piri and colleagues (29) confirm and add strategies, such as “cheating” and “referring to rules and routines”. Potthoff and colleagues (30) developed a conceptual model of psychological pressure based that influence is exerted not only with the aim of obtaining consent for the recommended treatment but also to ensure compliance with social rules.

Influence on the patient's will in a close therapeutic relationship between patient and team member can be exerted purposefully or unintentionally. The extent to which influencing the patient's will is perceived as coercion by the patient depends on aspects such as transparency, fairness, dignity, trust and the quality of the therapeutic alliance itself (13, 31).

In order to address the knowledge gap for the ICU setting and particularly the view of those who potentially exert informal coercion, our qualitative study focused on nurses and physicians' perception of influencing the patient's will.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board at University Medicine Greifswald, Germany (No.: BB 049/22). The report of this study is in concordance with the “COREQ” statement for qualitative research (32).

A qualitative approach was chosen to gain a better understanding of the influences on patients will as be perceived by physicians and nurses in the ICU. Three questions guided our research focus:

- How do nurses and physicians in the ICU understand influencing the patient's will?

- What forms of influence do they differentiate?

- In which contexts/situations are the different forms used?

Both researchers are female, have longstanding experience in intensive care and were also practicing at the time the interviews were conducted. AHS is a nurse and nursing scientist and holds a doctoral degree in medical ethics. SJ is an anaesthesiologist with a master's degree in medical ethics. Both authors have considerable experience with qualitative social research. The research interest resulted from their own experiences on the ICU.

Nurses and physicians in German ICUs were informed about the study and invited to participate through a poster at the wards. Those interested in the study used the contact details provided on the poster to obtain detailed study information. Potential participants were informed about the aims, content and methods of data collection and analysis as well as the voluntary nature of participation. Written informed consent was given by each participant. No incentives were offered. None of the potential participants declined to participate after receiving written information. Participants were able to withdraw until the data were anonymized during transcription.

Interviews were conducted via videoconferencing. Only the voice has been audio-recorded with an external device. The semi-structured interview guide covered a broad range of career experiences (Supplementary File 1). The interview guide (Supplementary File 1) included three parts and a fourth optional part. The fourth part was used if the aspects addressed there were not already covered by the interviewees in the previous parts:

1. Forms of influence (individual understanding)

2. Experiences with influencing the patient's will (recollection of typical situations)

3. Alternatives to influencing and/or overriding the patient's will

4. Relationship between professionals and patient

All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized.

Transcripts were exported into MAXQDA software to facilitate analysis. All transcripts were coded line by line by AHS and SJ to ensure quality and transparency using thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (33). The authors coded their respective interview transcripts independently. After each interview, the researchers met to share and compare their coding, discussed the different entries and refined the structure of the coding system. A joint coding system was created. If discrepancies on code application occurred, the coders discussed the matter until consensus was obtained. After coding all transcripts, we reviewed the coded content, identified themes, and synthesized data across themes.

Interviews with 14 nurses and 16 physicians were conducted between September 2022 and February 2023. Qualitative saturation was recognized after two-thirds of the respective group had been interviewed, however, the study continued in order to ensure maximum variation (Table 1).

The interview data are rich and go far beyond the scope of a single publication. The focus in this manuscript is, thus, on reporting the results that the thematic analysis revealed concerning (1) the situational context, respectively, the situations in which the will is influenced, controlled and/or intentionally overcome, and (2) the forms of influence and corresponding communicative strategies used. Table 2 lists the quotes that support the findings (see also Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summarizes the results and illustrates the transitions between the various forms of influence.

All interviewees described that influencing (purposefully or not) the patient's will is commonplace and often taken for granted. At the same time, interviewees considered intensive care to be a “complete package” in which the patient – once they have agreed to ICU admission – has to accept certain procedures that must be carried out due to standards on the ward (e.g., monitoring, central venous line, regular restraint of ventilated patients' hands). These measures themselves result in reduced mobility and increased dependency. According to the interviewees, most of the patients accepted this situation and complied with this seemingly unavoidable fact:

“They assume, okay, I have to go along with everything here. I have no will at all, I don’t have any, so they give up their basic rights at the entrance.” (Jan, nurse)

Participants even stated, that “you influence him [the patient's will] more often than you don't influence him” (Jakob, physician). Indeed, the spectrum of influence ranges from everyday communication situations and “little decisions” (e.g., personal hygiene) up to influencing decisions on treatment goals:

“It feels like we make decisions for the patient 24 h a day. So, it starts with food and ends somewhere at the end of life.” (Olivia, nurse)

Moreover, not only the current will but also – in the case of incapacity to consent – the predetermined will (advance directive) is disregarded and overridden.

It was described that the patient was influenced on a spectrum from motivation to restraining measures (sedation, physical restraint), particularly in the case of prophylactic measures, such as mobilization and breathing training. In some cases, at the same time; in other situations, as successive escalation strategies if patients did not comply.

Examinations and treatments, particularly those related to nutrition (feeding tube replacement), “Patients don’t want artificial nutrition or a feeding tube” (Florian, nurse), central venous catheter placement and the establishment of invasive measures, have been raised as common situations.

Furthermore, the patient's will is also overridden not only in day-to-day situations but, above all, in connection with living wills displayed in advance directives or concerning treatment decisions at the end-of-life made:

“So it's definitely the case that we have situations in which the patient's will was ignored… Even if a DNR [do not resuscitate] and DNI [do not intubate] decision is manifestly present, young colleagues have performed resuscitation at night and put the patient in exactly the situation that they have deliberately rejected.” (Emil, physician)

The patient's will is influenced during decision-making processes, “you urge the patient to make a decision” (Sebastian physician), concerning therapeutic goal setting using different strategies ranging from a judged transfer of information for treatment recommendations to the threat of reaching “informed consent” (also see result category 2).

The participants outlined a variety of possible forms of influence (motivation, conviction, subordination, control), which are each achieved with targeted verbal and nonverbal communicative practices. It also becomes apparent that the general understanding of the term “influence” varies from very broad to very specific and from negatively occupied to neutral.

Although compulsory treatment and restrictions of freedom were not the focus of the study, it was, nevertheless, raised by the participants as a relevant topic in the context of exerting influence on the will. When aiming to deliberately override and/or break the patient's will, formal coercion (physical restraint, sedation) is applied. “[…] the carelessness with which handcuffs are used.” (Emily, nurse).

According to the interviewees, these means are used due to the high workload and poor staffing levels, but sometimes also by default and without reflection.

Numerous psychological and communicative practices, such as persuasion, exercising authority, dehumanization and threat are used in order to achieve a patient's integration into the daily ward structures and adherence to the therapeutic interventions.

“Trying to persuade the patient, well, I’ve definitely experienced that much more often than they tried to convince the patient to undergo a surgery.” (Alice, physician)

The interviewees' descriptions showed that the different position in the room alone has a considerable influence on the patient's will: “bend over the bed and look down from above” Martha, nurse

This imbalance of power and knowledge is also used purposefully to present oneself as an authority, which is a common strategy to ensure the acceptance of what is deemed necessary. To this end, the nurses and physicians exploit their knowledge advantage and their professional role and status over patients. The communication style is very directive; instructions are given without room for negotiation.

“An imbalance of knowledge and power is naturally played out, […] And the patient has to comply because they simply believe it, even if it is not true in terms of content.” (Finn, physician)

However, not only the way in which information is communicated, but also which information is deliberately not given (e.g., therapy alternatives) was described as a strategy. Nurses often serve as facilitators and translators of facts that are not understood in the physician-patient communication. Thus, they also influence the patient's will through the content and manner in which they provide information: “the patients then usually ask the nurses afterwards what was said about me, that is what I mean by influencing the patients.” (Mia, nurse)

Moreover, interviewees described that patients are demeaned “use the first name by mistake” (Martha nurse) and/or belittled, which also influences their volition and, thus, their decisions. Disrespect is expressed through a wide variety of behaviours, such as a lack of empathy, taking/not giving privacy and failure to control symptoms, such as pain or anxiety.

Regardless of their decision-making, the patient's will is also purposefully overridden. Strategies range from ignoring the expressed will by not taking it seriously “the patient says something but you don't listen at all.” (Emily, nurse) or simply continuing to carry out the intended action, to depriving the patient of the opportunity to express their will (e.g., taking away the bell).

Most interviewees generally described that they perceived threats, including gestures, intimidating volume and/or intonation. For the majority of interviewees, threats are defined by the fact that they contain “if you don't do x – then y will happen” formulations. For them, threat is also characterized by “scaring someone” (Alice, physician). Threat is also defined by direct action for some interviewees, and is, thus, partly differentiated from a warning: “So, if you don't do this now, I’ll hurt you.” (Sebastian, physican). When using threat, the negative consequences are explicitly verbalized (e.g., necessity of restraint).

According to the interviewees, convincing can be based on either rational arguments or manipulative strategies. Here, the boundary between influencing through the provision of information and exerting informal coercion is blurred. Manipulation, in the sense of deliberately influencing the patients will without their knowledge and against their will in the ICU is perceived in many different situations and associated with negative moral connotations “not benefiting the patient” (Ben, physician).

Accordingly, different forms of convincing through manipulation related to information transfer were described: deception, interpersonal leverage through family members and lying. However, some interviewees avoided or rejected the term “manipulation” and use instead the wording “bending the path the way they would like it to be” (Emil, physician).

A pre-filtered explanation and disclosure of information is described as a common strategy: “Some things are sometimes simply not said” (Olivia, nurse) or lying: “[…] by withholding information, you can also do it by providing false information” (Sebastian, physician).

Furthermore, targeted influence on family members and loved ones, who, in turn are supposed to influence the patient “through the back door” (Emil physician) is also described.

According to the interviewees, the aim of motivation is to influence the patient's decisions in the “right direction”, while maintaining freedom of choice. Here, they not only provide information but also offer certain perspectives or incentives “wouldn't it be nice to have lunch” (Emily, nurse) to encourage them to participate in the intended measure. To motivate can also mean to:

“Encourage, empower, express confidence, make small successes that the patient does not see visible” (Aaron, physician),as well as to remind the patients of the goal towards which they are working “because there's someone at home waiting” (Ava, nurse)

The interviewees often expressed moral concerns: “It's always difficult to find the line between what is motivation and what is manipulation.” (Henry, nurse).

To the best of our knowledge, this interview study is the first to describe data on influencing the patient's will from the perspective of ICU nurses and physicians. The possibilities and forms of influencing and overcoming the patient's will are manifold and go far beyond the formal coercion that is widely discussed, which was, nonetheless, also frequently described in our interviews. The results can partly be integrated into existing attempts to structure forms of (treatment) pressure and informal coercion as described within mental healthcare and from the patient's perspective (24, 29–31). As our interviews show impressively, the whole range of forms can also be found in the ICU. Applying the concept of informal coercion to the ICU can be fruitful, because situations similar to those in the psychiatric setting occur: There is evidence of up to 80% for delirium as an intensive care psychiatric emergency (34, 35). Similar to psychiatry, the situation of dependency is the underlying context. Not all the influencing strategies described can always be defined as “informal coercion”. If, however, psychological pressure is applied, conditions are imposed or influence is exerted by the team in the situation of dependency, this can lead to informal coercion (25). Both psychiatric and intensive care patients describe dependency and coercion, and the perception of formal and informal coercion (19, 36–38). There are, however, additional forms of exercising power specific to the ICU context to overcome the patient's will, such as ignorance, disrespect and, as a result, dehumanization, that have been described by our interviewees. The fact that patients desire more respectful treatment and better communication to maintain their dignity has already been described in the literature (39, 40). Intensive efforts to humanize the ICU environment and patients' treatment experiences show that professionals are already at least aware of this issue. Nevertheless, there is still a discrepancy between the professionals own ambitions in theory and everyday life in practice (41, 42). Moreover, it is interesting that despite or precisely in view of this knowledge, dehumanizing strategies are specifically used to influence patients’ decision-making and/or to overcome their will. We note with caution that - as in psychiatry - the situation of dependency can be exploited in a targeted manner. We know from the context of psychiatry that influence is perceived as informal coercion by the patient. This approach is also clearly illustrated by Hempeler and colleagues (24), who point out that Szmukler's conceptualization – according to which only a threat corresponds to informal coercion – does not do justice to the weight of power (imbalance) in practice. One challenge is certainly that professionals not only in psychiatry (23, 43) but also in the ICU might not always recognize informal coercion or might also lack knowledge on this topic.

Four additional points revealed in our data are particularly interesting:

Firstly, all of the forms of influence described are used in the ICU alongside each other and, in some cases, alternately and/or together, so that they do not only occur hierarchically as escalation levels, as displayed in Szmukler's work (27), but in daily ICU reality independently of each other. Pelto-Piri and colleagues (29) drew a conclusion in their study in the context of psychiatry, stating that (1) it is not always the mildest measure with the least coercive character that is used as a starting point in the classical hierarchy and (2) that different forms may also be combined with each other and switched back and forth between them in different ways. The transition is particularly fluid with certain nursing measures, such as breathing training, where all levels of escalation were reported, from motivation, persuasion and threat up to physical restraint and sedation.

Secondly, the severity of the form of influence does not necessarily relate to the necessity of the action that is to be achieved and the possible consequences of omitting it. Threats for example, are also used in an attempt to achieve adherence with body care as planned in the daily shift routine. It is beyond doubt that it is an enormous challenge to give patients' individuality sufficient space within the rigid hospital routines and precarious personnel and economic framework conditions. For this reason in particular, healthcare professionals should constantly remind themselves that they have to prioritize certain actions in situations of strong asymmetry (44).

Thirdly, in order to achieve cooperation, “artificial consequences” are created, i.e., those consequences that either do not logically arise as a result of the omission of the action or, at least, do not directly follow from omitting it. Here, the question arises as to whether the use of (informal) coercion in these cases is actually intended to promote the patient's well-being or which, resp. whose interests are decisive.

The fourth point concerns the surprisingly similar description of the situation and the overall similarity between the patients' and professionals’ perspectives, as it appears in comparison between our results and those of previously published studies with patients. Patients in the ICU wish for respectful treatment with involvement in decision-making and professionals aim for it, too. Improving the conditions and motivation for realisation on both sides should therefore be a key objective of future interventions.

It was shown that not only major treatment decisions but, above all, daily measures, particularly prophylaxis and mobilization, involve challenging situations and negotiation processes. In order to better understand the therapeutic pressure, e.g., during (early) mobilisation, follow-up studies should also include the perspective of other professions in the ICU.

This publication is limited to a presentation of the descriptive data. Some strategies have already been rated by the interviewees themselves as helpful and ethically appropriate; others, however, were deemed ethically inappropriate and not effective but are used. Further ethical analysis is needed here following, for example (45, 46).

Another limitation is that the study was conducted in German ICUs. Further studies in an international context are necessary to evaluate the statements regarding the use of informal coercion.

Most of the professionals in our interview study in German ICUs stated that they use not only coercion, such as restraining measures, but also particularly informal coercion and influencing the patient's will through measures such as ignoring the patient and/or their will, dehumanization, threats, manipulation and persuasion within their therapeutic activities in the ICU. Convincing, argumentative and manipulative, and motivating the patient were reported as supportive influences. The forms of influence described were used consciously or unconsciously, in parallel and, in some cases, alternately and/or together.

Many interviewees became aware of the extent to which the patient's will is influenced on the ICU during the interview. Regarding everyday intensive care, this means that regular reflection on how to deal with the patient in the treatment situation is necessary.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board at University Medicine Greifswald, Germany (BB 049/22). All participants gave written informed consent for the study participation. Written informed consent obtained for each interview included consent for publication of anonymized data, including direct quotations from interview transcripts.

A-HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was funded thanks to a research award of the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (DIVI). Funding was used for transcription and open access fees. The authors are responsible for the content of this publication. The DIVI had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, reporting of the results or the preparation of this manuscript. Support for the publication fee was provided by University of Greifswald's publication fund.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanes.2025.1460909/full#supplementary-material

2. Varelius J. The value of autonomy in medical ethics. Med Health Care Philos. (2006) 9(3):377–88. doi: 10.1007/s11019-006-9000-z

3. Henry LM, Rushton C, Beach MC, Faden R. Respect and dignity: a conceptual model for patients in the intensive care unit. Narrat Inq Bioeth. (2015) 5(1a):5a–14a. doi: 10.1353/nib.2015.0007

4. Lykkegaard K, Delmar C. Between violation and competent care–lived experiences of dependency on care in the ICU. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. (2015) 10:26603. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v10.26603

5. Karlsson V, Bergbom I, Forsberg A. The lived experiences of adult intensive care patients who were conscious during mechanical ventilation: a phenomenological-hermeneutic study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2012) 28(1):6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.11.002

6. Corrêa M, Castanhel FD, Grosseman S. Patients’ perception of medical communication and their needs during the stay in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. (2021) 33(3):401–11. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20210050

7. Joebges S, Mouton-Dorey C, Ricou B, Biller-Andorno N. Coercion in intensive care, an insufficiently explored issue—a scoping review of qualitative narratives of patient’s experiences. J Intensive Care Soc. (2023) 24(1):96–103. doi: 10.1177/17511437221091051

8. Guttormson JL, Bremer KL, Jones RM. Not being able to talk was horrid": a descriptive, correlational study of communication during mechanical ventilation. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2015) 31(3):179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2014.10.007

9. Karlsen MW, Ølnes MA, Heyn LG. Communication with patients in intensive care units: a scoping review. Nurs Crit Care. (2019) 24(3):115–31. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12377

10. Basile MJ, Rubin E, Wilson ME, Polo J, Jacome SN, Brown SM, et al. Humanizing the ICU patient: a qualitative exploration of behaviors experienced by patients, caregivers, and ICU staff. Crit Care Explor. (2021) 3(6):e0463. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000463

11. Dziadzko V, Dziadzko MA, Johnson MM, Gajic O, Karnatovskaia LV. Acute psychological trauma in the critically ill: patient and family perspectives. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2017) 47:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.009

12. Negroni AA. On the concept of restraint in psychiatry. Eur J Psychiatry. (2017) 31(3):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpsy.2017.05.001

13. Hotzy F, Jaeger M. Clinical relevance of informal coercion in psychiatric treatment-a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2016) 7:197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00197

14. Burry L, Rose L, Ricou B. Physical restraint: time to let go. Intensive Care Med. (2018) 44(8):1296–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5000-0

15. Delgado SA. Physical restraints: protecting patients or devices? Am J Crit Care. (2020) 29(2):103. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2020742

16. Perez D, Peters K, Wilkes L, Murphy G. Physical restraints in intensive care-an integrative review. Aust Crit Care. (2019) 32(2):165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2017.12.089

17. Intensive Care Society. Guidance For: The Use of Physical Restraints in UK Adult Intensive Care Units (2021). Available online at: https://ics.ac.uk/resource/physical-restraints-guidance.html (Accessed May 05, 2024).

18. Azizpour M, Moosazadeh M, Esmaeili R. Use of physical restraints in intensive care unit: a systematic review study. Acta Medica Mediterranea. (2017) 33(1):129–36.

19. Jöbges S, Mouton Dorey C, Porz R, Ricou B, Biller-Andorno N. What does coercion in intensive care mean for patients and their relatives? A thematic qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. (2022) 23(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00748-1

20. Franks ZM, Alcock JA, Lam T, Haines KJ, Arora N, Ramanan M. Physical restraints and post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2021) 18(4):689–97. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-738OC

21. Smithard D, Randhawa R. Physical restraint in the critical care unit: a narrative review. New Bioeth. (2022) 28(1):68–82. doi: 10.1080/20502877.2021.2019979

22. Freeman S, Hallett C, McHugh G. Physical restraint: experiences, attitudes and opinions of adult intensive care unit nurses. Nurs Crit Care. (2016) 21(2):78–87. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12197

23. Elmer T, Rabenschlag F, Schori D, Zuaboni G, Kozel B, Jaeger S, et al. Informal coercion as a neglected form of communication in psychiatric settings in Germany and Switzerland. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 262:400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.014

24. Hempeler C, Braun E, Potthoff S, Gather J, Scholten M. When treatment pressures become coercive: a context-sensitive model of informal coercion in mental healthcare. Am J Bioeth. (2023) 24(12):74–86. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2023.2232754

25. Valenti E, Giacco D. Persuasion or coercion? An empirical ethics analysis about the use of influence strategies in mental health community care. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):1273. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08555-5

26. Klingemann J, Świtaj P, Lasalvia A, Priebe S. Behind the screen of voluntary psychiatric hospital admissions: a qualitative exploration of treatment pressures and informal coercion in experiences of patients in Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2022) 68(2):457–64. doi: 10.1177/00207640211003942

27. Szmukler G, Appelbaum PS. Treatment pressures, leverage, coercion, and compulsion in mental health care. J Mental Health. (2008) 17(3):233–44. doi: 10.1080/09638230802052203

28. Rugkåsa J, Canvin K, Sinclair J, Sulman A, Burns T. Trust, deals and authority: community mental health professionals’ experiences of influencing reluctant patients. Community Ment Health J. (2014) 50(8):886–95. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9720-0

29. Pelto-Piri V, Kjellin L, Hylén U, Valenti E, Priebe S. Different forms of informal coercion in psychiatry: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes. (2019) 12(1):787. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4823-x

30. Potthoff S, Gather J, Hempeler C, Gieselmann A, Scholten M. Voluntary in quotation marks": a conceptual model of psychological pressure in mental healthcare based on a grounded theory analysis of interviews with service users. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03810-9

31. Silva B, Bachelard M, Amoussou JR, Martinez D, Bonalumi C, Bonsack C, et al. Feeling coerced during voluntary and involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation: a review and meta-aggregation of qualitative studies. Heliyon. (2023) 9(2):e13420. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13420

32. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

34. Palacios-Ceña D, Cachón-Pérez JM, Martínez-Piedrola R, Gueita-Rodriguez J, Perez-de-Heredia M, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. How do doctors and nurses manage delirium in intensive care units? A qualitative study using focus groups. BMJ Open. (2016) 6(1):e009678. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009678

35. Baron R, Binder A, Biniek R, Braune S, Buerkle H, Dall P, et al. Evidence and consensus based guideline for the management of delirium, analgesia, and sedation in intensive care medicine. Revision 2015 (DAS-guideline 2015) - short version. Ger Med Sci. (2015) 13:Doc19. doi: 10.3205/000223

36. Ling S, Cleverley K, Perivolaris A. Understanding mental health service user experiences of restraint through debriefing: a qualitative analysis. Can J Psychiatry. (2015) 60(9):386–92. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000903

37. Lindberg C, Sivberg B, Willman A, Fagerström C. A trajectory towards partnership in care–patient experiences of autonomy in intensive care: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2015) 31(5):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2015.04.003

38. Norvoll R, Pedersen R. Exploring the views of people with mental health problems’ on the concept of coercion: towards a broader socio-ethical perspective. Soc Sci Med. (2016) 156:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.033

39. Sun X, Zhang G, Yu Z, Li K, Fan L. The meaning of respect and dignity for intensive care unit patients: a meta-synthesis of qualitative researches. Nurs Ethics. (2024) 31(4):652–69. doi: 10.1177/09697330231222598

40. Sanson G, Lobefalo A, Fascì A. Love can't be taken to the hospital. If it were possible, it would be better": patients’ experiences of being cared for in an intensive care unit. Qual Health Res. (2021) 31(4):736–53. doi: 10.1177/1049732320982276

41. Ames N, Shuford R, Yang L, Moriyama B, Frey M, Wilson F, et al. Music listening among postoperative patients in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial with mixed-methods analysis. Integr Med Insights. (2017) 12:1178633717716455. doi: 10.1177/1178633717716455

42. Nydahl P, Ely EW, Heras-La Calle G. Humanizing delirium care. Intensive Care Med. (2024) 50(3):469–71. doi: 10.1007/s00134-024-07329-3

43. Jaeger M, Ketteler D, Rabenschlag F, Theodoridou A. Informal coercion in acute inpatient setting–knowledge and attitudes held by mental health professionals. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 220(3):1007–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.014

44. Delmar C. The excesses of care: a matter of understanding the asymmetry of power. Nurs Philos. (2012) 13(4):236–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2012.00537.x

45. Barilan YM, Weintraub M. Persuasion as respect for persons: an alternative view of autonomy and of the limits of discourse. J Med Philos. (2001) 26(1):13–33. doi: 10.1076/jmep.26.1.13.3033

Keywords: intensive care unit, healthcare professionals, patient will, influence, manipulation, coercion, autonomy, qualitative study

Citation: Seidlein A-H and Jöbges S (2025) Influencing the critically ill patient? A qualitative study with teams in German intensive care. Front. Anesthesiol. 4:1460909. doi: 10.3389/fanes.2025.1460909

Received: 7 July 2024; Accepted: 28 January 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

André Van Zundert, The University of Queensland, AustraliaReviewed by:

Theodoros Aslanidis, Agios Pavlos General Hospital, GreeceCopyright: © 2025 Seidlein ana Jöbges. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna-Henrikje Seidlein, YW5uYS1oZW5yaWtqZS5zZWlkbGVpbkBtZWQudW5pLWdyZWlmc3dhbGQuZGU=

†ORCID:

Anna-Henrikje Seidlein

orcid.org/0000-0002-7690-567X

Susanne Jöbges

orcid.org/0000-0002-9509-8631

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.