- 1Research and Development Unit, Hammersmith and Fulham Primary Care Network, London, United Kingdom

- 2Faculty or Medicine, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction

In our roles as general practitioners, we frequently encounter the complex issues of polypharmacy and social isolation, especially among our elderly patients (Svensson et al., 2023). The interconnected nature of these challenges underscores the critical need for a holistic approach in primary care (Siqeca et al., 2022). As our society ages, we are seeing an increase in patients with multiple chronic conditions, which often leads to polypharmacy. Concurrently, social isolation is emerging as a significant concern with profound health consequences (Masnoon et al., 2017). The potential interplay between these two factors is gaining recognition in the medical community, prompting a deeper exploration of their combined impact on health (Davies et al., 2020). By adopting a comprehensive care strategy, we have the opportunity to significantly enhance the health and wellbeing of our patients, addressing not just their medical needs but also the social determinants of health that significantly influence their overall quality of life.

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications, is becoming a staple in the treatment regimens of our aging patients (Delara et al., 2022). Both empirical research and clinical observations highlight the dangers associated with polypharmacy, including adverse drug reactions, falls, potential drug interactions, and a heightened likelihood of hospital admissions (Masnoon et al., 2017; Svensson et al., 2023). In general, polypharmacy could be seen as exacerbating the physical effects of aging. In addressing the issue of polypharmacy, particularly in the context of chronic diseases and multimorbidity, general practitioners navigate increasingly complex health landscapes (Jarling et al., 2022; Siqeca et al., 2022).

Social isolation

The phenomenon of social isolation among the elderly is characterized by a tangible absence of social connections, as opposed to the subjective sensation of loneliness, and is linked with increased risks of morbidity and mortality (D’cruz and Banerjee, 2020). This condition emerges from a complex interplay of physical, psychological, and social factors, which can all negatively alter health behaviours (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). The ramifications of social isolation can deeply impact the psychological realm, often precipitating conditions such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, exacerbating the psychological challenges associated with aging (Barton et al., 2014).

The interplay between polypharmacy and social isolation

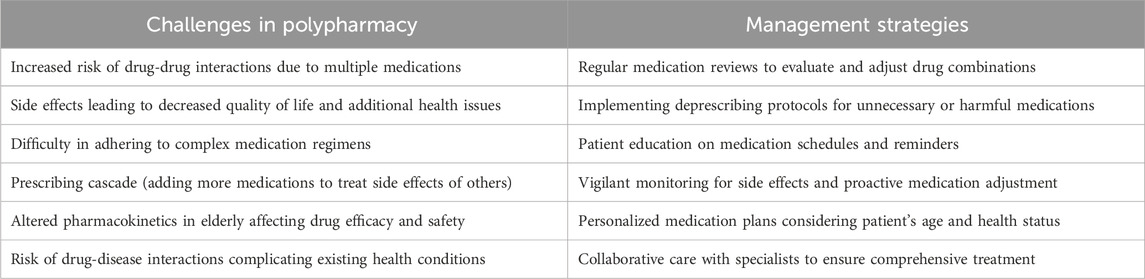

There is increasing interest in the interplay and compounding effects of polypharmacy and social isolation. Moreover, the isolation experienced by many elderly individuals exacerbates the challenges posed by polypharmacy (Table 1). Social isolation not only effects mental and emotional wellbeing but also has tangible impacts on how individuals manage their health. For example, a lack of social support can lead to irregular medication intake, missed appointments, worsened health behaviours, and a general decline in health vigilance. Patients who are socially isolated have been found to exhibit suboptimal medication compliance and overall health management, which further exacerbates their physical health conditions (Siqeca et al., 2022; Svensson et al., 2023). This scenario underscores the importance of incorporating social care into the management plan for elderly patients (de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg, 1999; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Masnoon et al., 2017).

Addressing the complex web of social isolation and its ramifications on mental health reveals a stark reality. The psychological toll of isolation often manifests as depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline among the elderly, complicating their ability to manage physical health issues (Barton et al., 2014). This interplay between mental and physical health can obscure the root causes of symptoms, as signs of mental health struggles might be mistaken for adverse reactions to medications, and vice versa. Such diagnostic challenges underscore the need for a holistic approach that encompasses both medical and social considerations in patient care. This diagnostic landscape also underscores the necessity for a holistic healthcare approach that integrates medical and social considerations to effectively address the intertwined challenges of polypharmacy and social isolation (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Siqeca et al., 2022).

Proposed interventions

The coexistence of polypharmacy and social isolation presents a distinctive set of challenges, with interventions that fail to simultaneously tackle both being much less likely to succeed in our experience, whilst also having more challenge for the clinician in getting “buy in” from the patient. This necessitates a healthcare approach that extends beyond conventional medical treatments to encompass a broader spectrum of patient care (Davies et al., 2020).

In addressing polypharmacy within the elderly demographic, it becomes clear that the traditional focus on medication management alone is insufficient. The complexities of chronic conditions in these patients often result in a labyrinth of prescriptions, each aiming to tackle a specific aspect of their health (D’cruz and Banerjee, 2020; Cooper et al., 2015). However, this fragmented approach overlooks the critical interdependencies within an individual’s health profile. For instance, the clear understanding of how medications interact not just with each other but also with the patient’s lifestyle, diet, and other non-pharmacological factors is often underappreciated (de Jong Gierveld and Havens, 2004; Masnoon et al., 2017). This gap in care necessitates a shift towards a more integrative medication management strategy, one that harmonizes pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions. By doing so, we can enhance the efficacy of medical treatments while minimizing the adverse effects that stem from polypharmacy.

Furthermore, it is imperative that primary care physicians adopt a proactive and meticulous approach towards medication management. This involves conducting thorough medication reviews that go beyond mere prescription oversight to include a deep understanding of each patient’s unique health profile, lifestyle, and social environment (D’cruz and Banerjee, 2020; Gnjidic et al., 2012). Such reviews should aim to optimize therapeutic outcomes by minimizing unnecessary medications and reducing the risk of adverse effects, thereby enhancing patient safety and wellbeing. The goal is to ensure that each medication serves a definitive purpose, aligns with the latest clinical guidelines, and contributes positively to the patient’s overall health strategy.

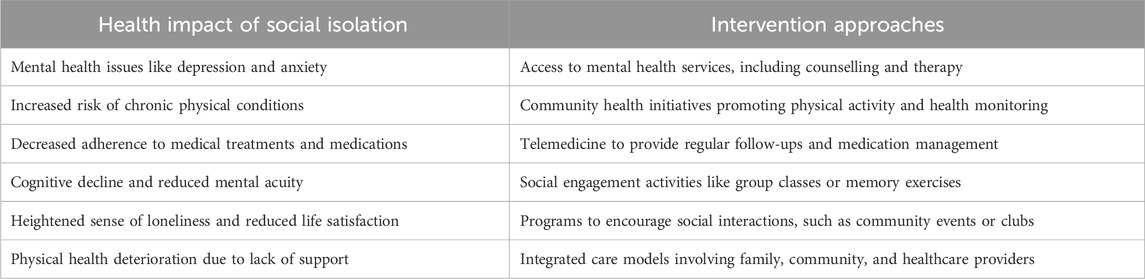

Given how social isolation interacts with polypharmacy, it is also crucial to integrate social care into the medical management plan (Table 2). This requires a concerted effort to identify and understand the social determinants of health that affect elderly patients, such as living conditions, access to community resources, and the strength of their social networks (Siqeca et al., 2022). By fostering strong collaborations with social care providers and community organizations, primary care physicians can facilitate access to supportive services and social activities that promote engagement and connectivity (Davies et al., 2020). These can include community health programs, support groups, and technology-based interventions designed to reduce loneliness. This holistic approach not only addresses the immediate health concerns, such as medication adherence and overall health management, but also contributes to the broader objective of improving the quality of life for elderly individuals, making healthcare more responsive, compassionate, sustainable, and tailored to the unique needs of this vulnerable population (Cooper et al., 2015; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Jarling et al., 2022).

Expanding on this, it becomes evident that the management of polypharmacy must be intertwined with an understanding of the patient’s social backdrop. Embracing a multifaceted strategy in primary care, particularly for the elderly, requires general practitioners to assess not just the clinical aspects but also the socio-environmental factors impacting patient health, including social networks and wellbeing (Fried et al., 2014; Garvey et al., 2015; Wood et al., 2021). Regular, thorough evaluations that encompass physical health assessments, medication management, and psychological support are fundamental. The interrelation between an individual’s social environment and their health status is undeniable, necessitating a broader approach that includes or expands regular social needs assessments within existing frailty or comprehensive geriatric assessments (Robles Bayón and Gude Sampedro, 2014; Delara et al., 2022). By identifying and proactively addressing these social determinants of health, we can better tailor our interventions to meet the holistic needs of our patients, enhancing their overall health and wellbeing. These can feed into collaborative care with pharmacists, mental health professionals, social workers, and community groups, as part of developing a comprehensive care plan. Moreover, leveraging social prescribing and community resources can proactively and significantly enhance the holistic wellbeing of patients.

In the practice of primary care, our role extends beyond the mere management of medications; it involves actively engaging with our patients to foster an environment of health literacy and autonomy (Svensson et al., 2023). This should extend to patient discussions about the problems of polypharmacy, elucidating its potential risks and impacts on daily living, while simultaneously highlighting the value of maintaining robust social connections (Masnoon et al., 2017). Through educational initiatives and personalized conversations, we strive to elevate our patients’ understanding of their health conditions and treatment plans (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). This empowers them to make informed decisions about their health, leading to improved adherence to prescribed therapies and a proactive stance towards nurturing their social wellbeing. Patients themselves are also best placed to make decisions about enhancing their social networks, within their personal, family, and cultural context.

Moreover, the integration of innovative care strategies, such as shared decision-making and patient-centred care planning, marks a pivotal shift towards a more inclusive and participative model of healthcare (Vyas et al., 2021). By involving patients and their caregivers in the decision-making process, especially in the context of managing multiple medications and navigating the complexities of their social environments, we not only respect their autonomy but also enhance their sense of control over their health outcomes (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Delara et al., 2022). This collaborative approach, underpinned by mutual respect and open communication, fosters a therapeutic partnership between patients and healthcare providers (Wimmer et al., 2017). For example, where open dialogue about patient experiences of medication harm or non-adherance is encouraged, healthcare providers can better understand their patients’ perspectives and tailor their approaches to meet individual needs (Garvey et al., 2015). It is within this partnership that we can truly address the multifaceted challenges of polypharmacy and social isolation, ultimately leading to a more holistic and satisfying healthcare experience for our elderly patients (Delara et al., 2022).

Addressing the prescribing cascade, a phenomenon where new medications are introduced to manage side effects from existing treatments, is a critical aspect of managing polypharmacy (Chen et al., 2023). This cycle often exacerbates the medication burden on patients, particularly the elderly, leading to increased risks of adverse drug reactions and further complicating their care. Proactive measures such as de-prescribing, where unnecessary medications are systematically discontinued, can play a pivotal role in alleviating this burden. Implementing such strategies requires a careful balance, ensuring that patients continue to receive essential treatment while minimizing the risks associated with excessive medication use.

Additional focus is needed on fostering strong partnerships with community resources, to amplify our efforts in combating the adverse effects of polypharmacy and social isolation (Garvey et al., 2015). Establishing robust networks with local community centres, support groups, and charities can provide our patients with more accessible, comprehensive care. These alliances play a critical role in enhancing social connectedness and enhance holistic care (D’cruz and Banerjee, 2020; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2021). By integrating these resources into our care plans, we can offer more personalized, effective solutions that address the wide array of challenges our elderly patients face, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes and a higher quality of life. Use of either local community interventions, or alternatively online interventions, further ensures these benefits can reach those with mobility or access needs.

Addressing polypharmacy and social isolation within healthcare systems demands innovative technological and policy-driven solutions, mindful of existing constraints. Strategic use of digital health tools can enhance patient monitoring and medication management, while policies fostering community engagement and interdisciplinary collaboration can mitigate social isolation impacts (Wimmer et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2021). Tailoring these interventions to fit within the operational and budgetary realities of healthcare systems is essential for sustainable implementation and maximized patient benefit. Furthermore, advocating for policies that support holistic care models at both national and international levels can bring about systemic changes beneficial for the elderly.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the dual challenges of polypharmacy and social isolation in primary care necessitate a holistic, multidisciplinary approach. Integrating medical, psychological, and social care, while also considering broader systemic and policy-based interventions, can significantly improve patient outcomes and enhance the quality of life for our elderly population, whilst limiting the detriments associated with advancing age. As general practitioners, we are positioned uniquely to lead this change, drawing upon our diverse experiences and perspectives to deliver comprehensive and empathetic care.

Author contributions

WJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. DH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Barton, S., Karner, C., Salih, F., Baldwin, D. S., and Edwards, S. J. (2014). Clinical effectiveness of interventions for treatment-resistant anxiety in older people: a systematic review. Health Technol. Assess. 18 (50), 1–59. v-vi. doi:10.3310/hta18500

Chen, Z., Liu, Z., Zeng, L., Huang, L., and Zhang, L. (2023). Research on prescribing cascades: a scoping review. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1147921. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1147921

Cooper, J. A., Cadogan, C. A., Patterson, S. M., Kerse, N., Bradley, M. C., Ryan, C., et al. (2015). Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy in older people: a Cochrane systematic review. BMJ Open 5 (12), e009235. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009235

Davies, L. E., Spiers, G., Kingston, A., Todd, A., Adamson, J., and Hanratty, B. (2020). Adverse outcomes of polypharmacy in older people: systematic review of reviews. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21 (2), 181–187. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.022

D’cruz, M., and Banerjee, D. (2020). An invisible human rights crisis': the marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic - an advocacy review. Psychiatry Res. 292, 113369. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113369

de Jong Gierveld, J., and Havens, B. (2004). Cross-national comparisons of social isolation and loneliness: introduction and overview. Can. J. Aging. 2004 Summer 23 (2), 109–113. doi:10.1353/cja.2004.0021

de Jong Gierveld, J., and van Tilburg, T. (1999). Living arrangements of older adults in The Netherlands and Italy: coresidence values and behaviour and their consequences for loneliness. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 14 (1), 1–24. doi:10.1023/a:1006600825693

Delara, M., Murray, L., Jafari, B., Bahji, A., Goodarzi, Z., Kirkham, J., et al. (2022). Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 601. Erratum in: BMC Geriatr. 2022 Sep 12;22(1):742. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x

Fried, T. R., O'Leary, J., Towle, V., Goldstein, M. K., Trentalange, M., and Martin, D. K. (2014). Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62 (12), 2261–2272. doi:10.1111/jgs.13153

Garvey, J., Connolly, D., Boland, F., and Smith, S. M. (2015). OPTIMAL, an occupational therapy led self-management support programme for people with multimorbidity in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 16, 59. doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0267-0

Gnjidic, D., Hilmer, S. N., Blyth, F. M., Naganathan, V., Waite, L., Seibel, M. J., et al. (2012). Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65 (9), 989–995. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018

Jarling, A., Rydström, I., Fransson, E. I., Nyström, M., Dalheim-Englund, A. C., and Ernsth Bravell, M. (2022). Relationships first: Formal and informal home care of older adults in Sweden. Health Soc. Care Community 30 (5), e3207–e3218. doi:10.1111/hsc.13765

Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., et al. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 152, 157–171. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L., and Caughey, G. E. (2017). What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 17 (1), 230. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

Robles Bayón, A., and Gude Sampedro, F. (2014). Inappropriate treatments for patients with cognitive decline. Neurologia 29 (9), 523–532. doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2012.05.004

Siqeca, F., Yip, O., Mendieta, M. J., Schwenkglenks, M., Zeller, A., De Geest, S., et al. (2022). Factors associated with health-related quality of life among home-dwelling older adults aged 75 or older in Switzerland: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 20 (1), 166. doi:10.1186/s12955-022-02080-z

Svensson, M., Ekström, H., Elmståhl, S., and Rosso, A. (2023). Association of polypharmacy with occurrence of loneliness and social isolation among older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 116, 105158. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2023.105158

Vyas, M. V., Watt, J. A., Yu, A. Y. X., Straus, S. E., and Kapral, M. K. (2021). The association between loneliness and medication use in older adults. Age Ageing 50 (2), 587–591. doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa177

Wimmer, B. C., Cross, A. J., Jokanovic, N., Wiese, M. D., George, J., Johnell, K., et al. (2017). Clinical outcomes associated with medication regimen complexity in older people: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65 (4), 747–753. doi:10.1111/jgs.14682

Keywords: polypharmacy, social isolation, frail adults, elderly medicine, frailty

Citation: Jerjes W and Harding D (2024) Confronting polypharmacy and social isolation in elderly care: a general practitioner’s perspective on holistic primary care. Front. Aging 5:1384835. doi: 10.3389/fragi.2024.1384835

Received: 10 February 2024; Accepted: 26 April 2024;

Published: 31 May 2024.

Edited by:

Maria A. Ermolaeva, Leibniz Institute on Aging, Fritz Lipmann Institute (FLI), GermanyReviewed by:

Anne Ambrose, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, United StatesAye Mon Win, Montefiore Medical Center, New York City, United States, in cooperation with reviewer AA

Copyright © 2024 Jerjes and Harding. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Waseem Jerjes, d2FzZWVtLmplcmplc0BuaHMubmV0

Waseem Jerjes

Waseem Jerjes Daniel Harding1,2

Daniel Harding1,2