94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Aging Neurosci., 04 February 2021

Sec. Neurocognitive Aging and Behavior

Volume 13 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.625551

Purpose: Loss of grip strength and cognitive impairment are prevalent in the elderly, and they may share the pathogenesis in common. Several original studies have investigated the association between them, but the results remained controversial. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to quantitatively determine the relationship between baseline grip strength and the risk of cognitive impairment and provide evidence for clinical work.

Methods: We performed a systematic review using PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Web of Science up to March 23, 2020, and focused on the association between baseline grip strength and onset of cognitive impairment. Next, we conducted a meta-analysis using a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) as effect measures. Heterogeneity between the studies was examined using I2 and p-value. Sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses were also performed, and publication bias was assessed by Begg's and Egger's tests.

Results: Fifteen studies were included in this systematic review. After sensitivity analyses, poorer grip strength was associated with more risk of cognitive decline and dementia (HR = 1.99, 95%CI: 1.71–2.32; HR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.32–1.79, respectively). Furthermore, subgroup analysis indicated that people with poorer strength had more risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and non-AD dementia (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.09–1.81; HR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.10–1.91, respectively).

Conclusions: Lower grip strength is associated with more risk of onset of cognitive decline and dementia despite of subtype of dementia. We should be alert for the individuals with poor grip strength and identify cognitive dysfunction early.

Physical performance gradually declines with aging, and loss of grip strength is also a well-recognized manifestation of age-related motor decline and of geriatric syndromes such as sarcopenia and frailty (Buchman et al., 2007). Measure of grip strength is noninvasive and widely available (Ferlay et al., 2019), therefore grip strength measurement is often applied to reflect upper muscle strength in clinical setting. Being sensitive to age-related changes and changes in biological function, grip strength is not only an indicator of muscle strength but also of biological vitality (MacDonald et al., 2004). Furthermore, cognitive decline and dementia are common outcomes of aging that significantly affect the quality of life of the elderly people. Cognitive decline is frequently regarded as a prodrome to dementia, but exists on a continuum with normal aging (Heward et al., 2018). Individuals with cognitive decline are nevertheless at high risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia.

It is reported that sarcopenia leads to physical inactivity, and physical decline has been consistently associated with future cognitive decline (Cabett Cipolli et al., 2019). Inflammatory and hormonal pathway and brain atrophy might be the explanation for the association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment (Iannuzzi-Sucich et al., 2002; Schaap et al., 2006). Besides, frailty is common in the elderly. Frailty was defined as a clinical syndrome in which three or more of the following criteria were present: unintentional weight loss (10 lbs in past year), self-reported exhaustion, weakness (low grip strength), slow walking speed, and low physical activity (Fried et al., 2001). Frailty and AD may share underlying pathogeneses, and the rates of change of frailty and cognition over time are strongly associated with the same brain pathologies, such as the presence of macroinfarcts, Alzheimer's disease pathology, and nigral neuronal loss (Buchman et al., 2014). Besides, sarcopenia, frailty and cognitive impairment are all correlated to aging, oxidative stress and inflammation and so on. A recent meta-analysis (Peng et al., 2019) indicated that sarcopenia was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment independent of study population, the definition of sarcopenia and cognitive impairment, but only cross-sectional studies were included in this analysis, and the association between three components of sarcopenia and cognitive function was not identified. Another systematic review (Zammit et al., 2019) showed that cognitive function and grip strength (as the measure of frailty) declined with aging, but with little to no evidence for longitudinal associations between rates of change of both.

Older individuals with low handgrip strength often show symptoms that can interfere with cognitive and physical performance, such as declines in mobility and balance and impairment in executive function and memory (Firth et al., 2018). Grip strength, as an important component of sarcopenia and frailty, was also reported to be associated with cognitive aging (Zammit et al., 2019), its relation to cognitive impairment is of great interest, therefore, we focused on the longitudinal relationship between baseline grip strength and the risk of cognitive impairment. It's of great benefit that regarding grip strength as an observational indicator, and discerning cognitive impairment at the early stages. Several studies have reported that poorer grip strength was associated with cognitive decline and onset of dementia (Heward et al., 2018; Jeong and Kim, 2018; Jeong et al., 2018), while some studies found no relationship between grip strength and cognitive dysfunction (Sibbett et al., 2018; Doi et al., 2019). This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the relationship between grip strength and onset of cognitive impairment including cognitive decline and dementia, in order to identify dementia earlier especially in persons who have lower grip strength and promote more appropriate planning for prevention and treatment for dementia.

Comprehensive literature searches in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and Web of Science from their inception to March 23, 2020, were performed using a combination of Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms with related free text terms (“grip strength” OR “hand strength” OR “muscle strength”) AND (“cognitive impairment” OR “cognitive dysfunction” OR “cognitive decline” OR “cognitive disorder” OR “dementia”). Specific search strategies for each database can be found in Supplementary Material 1. Only those studies that met the following inclusion criteria were selected: (1) it was an original longitudinal cohort study that aimed at the association between grip strength and cognitive impairment; (2) included validated and recognized tests that assessed cognition and grip strength; (3) original research articles developed with humans and in English; (4) grip strength as the exposure; (5) cognitive impairment as the outcome of observation; (6) HR and 95% CI were available. Review articles, case reports, animal studies, abstracts and chapters or books were not included. The studies searched in different databases were combined, and duplicate references were removed. If there was a duplication or overlap of the study group, then the study with the longest follow-up or had better quality was selected for the analysis. After removing duplicate papers, two authors (MC and SZ) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the identified searches and followed by a full-text review of potentially eligible articles. Furthermore, disagreements in study selection were judged and resolved by consensus among the involved authors. The current systematic review and meta-analysis followed the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Stroup et al., 2000).

The first author's name, year of publication, study design, population of study, sample size, follow-up period, follow-up rate, assessment of muscle strength, evaluation of cognitive function, outcome, statistical model, the adjusted variables included in the regression model and HRs ad 95%CI were extracted from each reference.

Since all of the included studies are observational cohort study design, the adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for quality assessment with 8-items for cohort studies was applied (Stang, 2010). A score of six or above was considered as high quality. If the two authors were unable to reach a consensus on the quality of studies, the corresponding author was consulted.

Pooled mean effect size was calculated using meta-analysis software Stata 15 SE. First, determine whether there is heterogeneity among the original studies. Study heterogeneity was measured using the Cochran's Q and I-squared statistics, assuming that a p < 0.10 for the former and a value ≥ 50% for the latter indicated a significant and substantial heterogeneity. Second, due to the heterogeneity, the random-effect model was used to calculate pooled effect size of HRs and 95%CI. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the robustness of results, in which pooled estimates were calculated after removing one study in each turn. Besides, subgroup analyses by type of cognitive impairment, cognition assessment, age, gender, population source were also performed to exclude effect of heterogeneity. Finally, publication bias was assessed using Begg's and Egger's tests.

A total of 4,778 articles were retrieved from Pubmed (981), Embase (2,185), Cochrane (300), and Web of Science (1,312). Among all the articles, 1,406 duplicates, 1,170 reviews and comments, books, animal studies and case reports were removed. After reading abstracts, 2,061 articles were excluded. Finally, after full-text reading, 15 articles (Buchman et al., 2007; Boyle et al., 2009; Sattler et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2013; Camargo et al., 2016; Moon et al., 2016; Veronese et al., 2016; Hooghiemstra et al., 2017; Heward et al., 2018; Jeong and Kim, 2018; Jeong et al., 2018; Sibbett et al., 2018; Doi et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Hatabe et al., 2020) were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Characteristics of all the studies included are listed in Table 1. The 15 included studies had 27,588 individuals, with the age of most studies more than 55 years. The sample size ranged from 263 to 6,435. Six studies were conducted in Asia, four studies were conducted in Europe, four were conducted in North America and one in Africa. The subjects of the studies were from the community-dwelling setting (13 studies), religious communities (one study), and memory clinic (one study). Ten articles regarded dementia (including AD, Vascular Dementia, non-AD dementia) as outcome variable and five were cognitive decline based on the decline of cognitive assessment scales. As for the diagnosis of dementia, two studies were based on medical record, four studies based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV), and National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for AD. Besides, for cognitive assessment, cognitive scales were used in the most of the studies, such as mini-mental state examination (MMSE). As to the cognitive status at baseline, participants were with subjective or objective cognitive impairment but no dementia (one study), without dementia (eight studies) and the residuals were without cognitive dysfunction. Most of studies conducted multivariable adjusted analyses with important confounders, including age, gender, education, and comorbidities. All studies were longitudinal cohort study design.

According to NOS scale, all of the included studies were of high quality (six studies for nine stars, five studies for eight stars and four studies for seven stars). Details were presented in Supplementary Table 1.

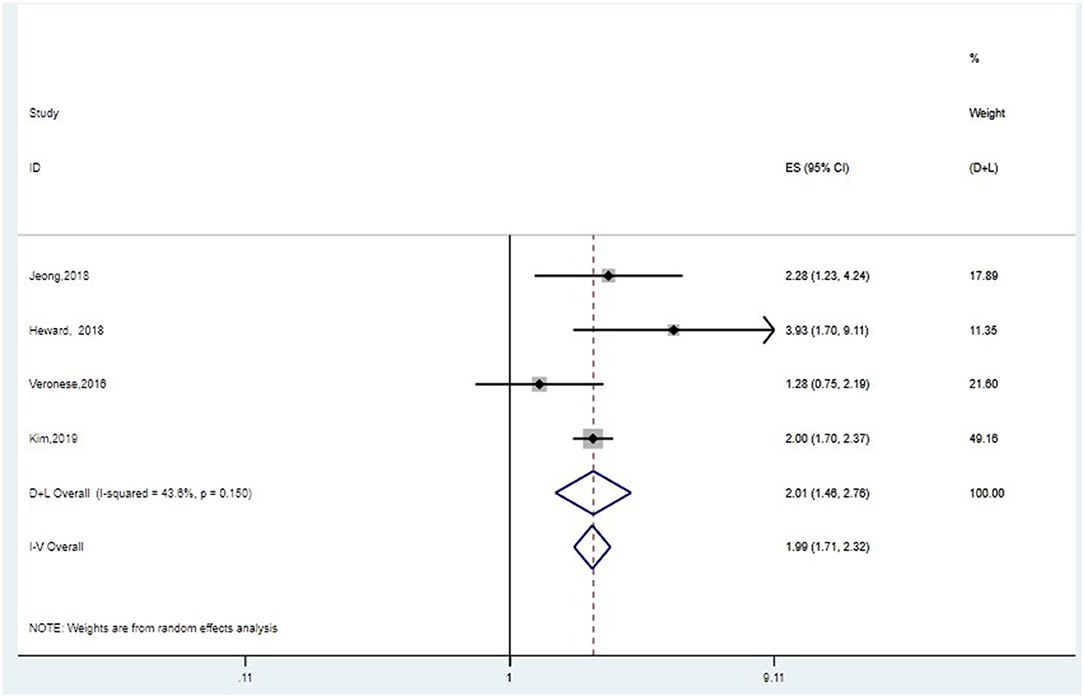

Five studies assessed the association between grip strength and cognitive decline. Poorer grip strength was associated with higher risk of cognitive decline (HR = 1.80, 95%CI: 1.35–2.40, I2 = 72.3%, P = 0.006) (Supplementary Figure 1A). Sensitivity analysis indicated that effects of Jeong and Kim (2018) might be the source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 1B). On one hand, the population of this study was relatively young, so the onset of cognitive decline might not be very obvious. On the other hand, cox proportional hazard models were used in this study, which were different from other included studies. After removing this study, the pooled effect size of HRs was 1.99, 95%CI: 1.71–2.32 (I2 = 43.6%, P = 0.150) with fixed-effect model (Figure 2). Begg's and Egger's tests produced P-values of 0.308 and 0.826, respectively, suggesting the absence of publication bias (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of the association between grip strength and cognitive decline after removing one study. The pooled HRs of four studies on the association between grip strength and cognitive decline was 1.99, 95%CI: 1.71–2.32 (I2 = 43.6%, P = 0.150) with fixed-effect model.

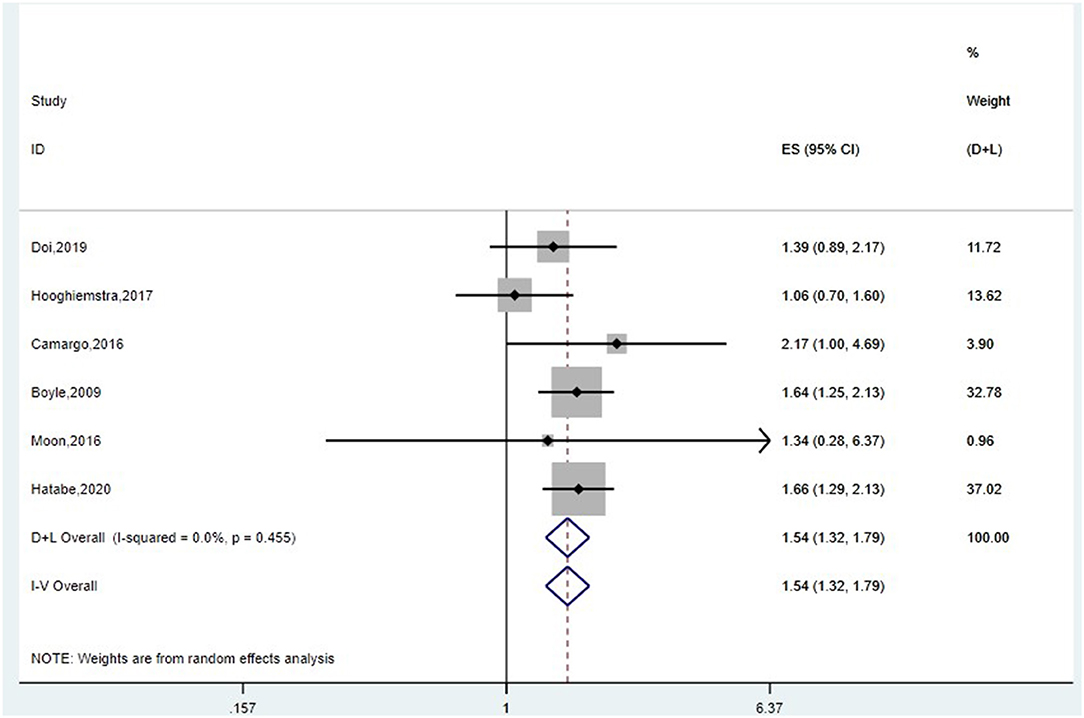

First, we conducted meta-analysis for 10 studies, of which outcome was dementia. If the studies included several outcomes, we selected the HRs of dementia, not AD or VaD. Furthermore, we chose the HRs of the entire samples instead of HRs of stratification by age or gender. The pooled HR of random-effect model was 1.03 (95%CI: 0.99–1.07, I2 = 78.1%, P = 0.000) (Supplementary Figure 2A). After sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figures 2B–F), four articles (Buchman et al., 2007; Sattler et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2013; Sibbett et al., 2018) were removed, and the final pooled HR of fixed-effect model was 1.54 (95%CI: 1.32–1.79, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.455) (Figure 3). People with poorer grip strength had more risk for suffering dementia. Begg's and Egger's tests produced P-values of 1.0 and 0.744, respectively, suggesting the absence of publication bias (Supplementary Figure 2G).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of the association between grip strength and dementia after removing four studies. The pooled HR of six studies on the association between grip strength and dementia was 1.54 (95%CI: 1.32–1.79, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.455).

Next, if the studies include several outcomes, then we extracted the HRs of each subtype of dementia, that is dementia, AD or non-AD dementia. The pooled HR of random-effect model was 1.08 (95%CI: 1.03–1.13, I2 = 78.2%, P = 0.000) (Supplementary Figure 3).

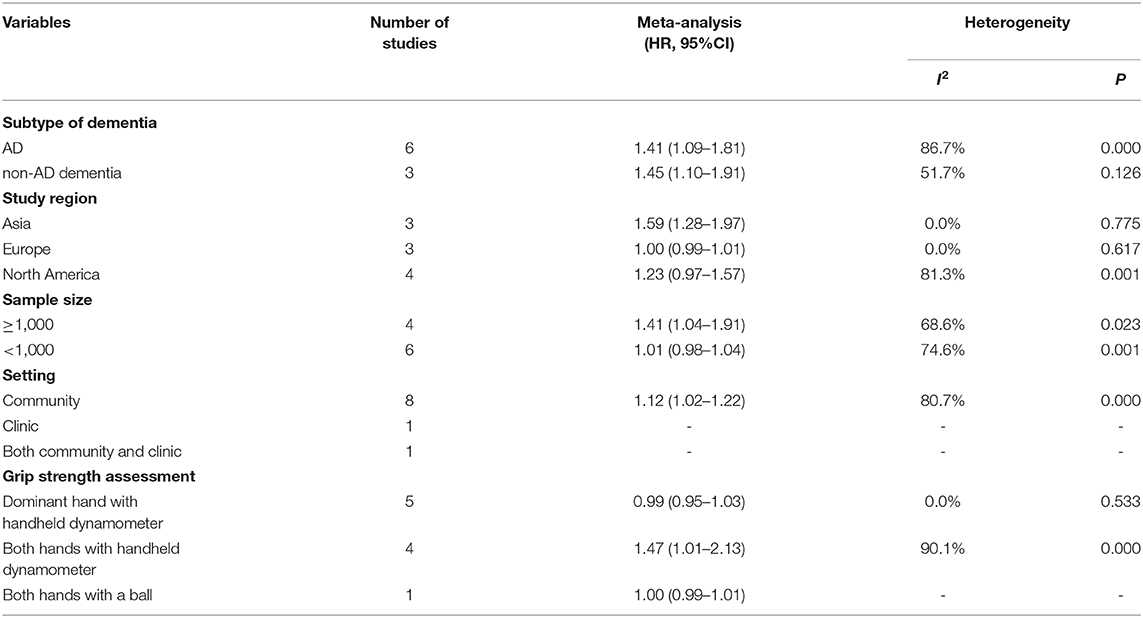

Based on the above results, we performed subgroup analysis by subtype of dementia, study region, sample size, setting and grip strength assessment (Table 2). People with poorer strength had more risk of AD and non-AD dementia (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.09–1.81; HR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.10–1.91, respectively). Studies from Asia had positive results (HR = 1.59, 95%CI: 1.28–1.97), but results from European and North American studies were negative. Studies of sample size ≥1,000 came to a conclusion that declined grip strength was associated with high prevalence of dementia (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.04–1.91). Grip strength assessment might also influence the outcome. After subgroup analysis, heterogeneity among studies still remained, while we conducted Begg's and Egger's tests of each subgroup, suggesting that our results had almost no publication bias (Supplementary Figures 4A–J). However, we still need expand the literature numbers to make further analysis.

Table 2. Subgroup analyses based on subtype of dementia, study region, sample size, setting and grip strength assessment.

This meta-analysis focused on the longitudinal association between grip strength and risk of cognitive impairment including two aspects, cognitive decline and dementia. Poorer grip strength was associated with higher risk of cognitive decline (HR = 1.99, 95%CI: 1.71–2.32, I2 = 43.6%, P = 0.150) and with onset of dementia (HR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.32–1.79, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.455). Furthermore, subgroup analysis indicated that people with poorer strength had more risk of AD and non-AD dementia (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.09–1.81; HR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.10–1.91, respectively). This meta-analysis quantitatively accumulated evidence from longitudinal studies suggesting that grip strength was inversely associated with the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in the middle-aged and elderly populations. In other words, grip strength may be an early indirect non-cognitive marker of subsequent cognitive decline or onset of dementia. Higher grip strength may reflect the integrity of neuromuscular system and higher resistance to oxidative stress and inflammation may extend to preservation of cognitive function (Weaver et al., 2002). Therefore, we could take measurement of grip strength as the initial screening, and for people who are identified as having poor grip strength, we should remain alert to the possibility of their cognitive problems.

This is the first study to quantitatively determine the association between grip strength and risk of cognitive impairment. Meta-analyses suggested a positive relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment (Cabett Cipolli et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2019), but which component of sarcopenia played a dominant role was not elucidated. However, lower muscle mass was thought not to be associated with high risk of cognitive dysfunction. A cross-sectional study also showed that lower-extremity functioning, rather than skeletal muscle mass, is closely related to multiple cognitive domains (Ishii et al., 2019). In the Epidemiologie de l'Osteoporose cohort, decreased muscle mass alone was not associated with cognitive dysfunction after seven years of follow-up (van Kan et al., 2013). In another community-based prospective cohort study, low muscle mass did not increase the risk of dementia in older adults during the 5 years of follow-up (Moon et al., 2016). Furthermore, a meta-analysis (Quan et al., 2017) suggested slow or decreased walking pace is significantly associated with elevated risk of cognitive decline and dementia in elderly populations. Based on these findings, lower grip strength and gait speed may be underlying factors for explaining the relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment. Besides, except for the studies included in this meta-analysis, there are also other studies which are consistent with our outcome. Chou et al. reported that a low handgrip strength could predict 10-years cognitive decline among community-dwelling older people (Chou et al., 2019). Handgrip strength predicted accelerated 1-year decline in cognitive function, assessed by Clock Drawing Test Performance, in a sample of older non-demented adults (Viscogliosi et al., 2017). Weaker grip strength in older women was associated with cognitive decline over a 4-years period (Auyeung et al., 2011). Importantly, more studies should be included in meta-analysis in the future.

In current study, as for cognitive decline, an article (Jeong and Kim, 2018) was removed after sensitivity analysis, due to the relatively younger population, and cox proportional hazard models used in this study, which were different from other included studies. In this way, the fixed-effect model was conducted and suggested poorer strength was significantly associated with cognitive decline. Furthermore, in the aspect of onset of dementia, first we regarded entire HRs of dementia as the outcome, after sensitivity analysis, four articles were removed. Sattler et al. (2011) assessed grip strength with the aid of the “Martin-Vigorimeter”, and participants pressed a ball alternating between two hands, which was different from other assessment with hydraulic hand dynamometer. Population of Buchman et al. (2007) was from older Catholic clergy members, whose physical fitness and cognitive function might be different from the community-dwelling. Sibbett et al. (2018) indicated that due to the retrospective dementia cases from records, the date of onset of dementia might not be accurate. Besides, the missed cases might also affect the outcome. Finally, diagnosis of dementia of Gray et al. (2013) was based on Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI), while others were based on diagnostic criteria of dementia and AD. Therefore, these four articles might be the source of heterogeneity. And the final pooled HR was 1.54, 95%CI: 1.32–1.79, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.455. Next, since some of the studies included several outcomes of dementia, we extracted HRs of each outcome respectively and conducted meta-analysis. The pooled HR of random-effect model was 1.08 (95%CI: 1.03–1.13, I2 = 78.2%, P = 0.000). Based on the results, we performed subgroup analysis to find out the source of heterogeneity. People with poorer strength had more risk of AD and non-AD dementia (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.09–1.81; HR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.10–1.91, respectively), which was consistent with previous entire outcome. Studies from Asia and sample size ≥1,000 had positive results (HR = 1.59, 95%CI: 1.28–1.97; HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.04–1.91, respectively) and grip strength assessment might also influence the outcome (both hands with handheld dynamometer, HR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.01–2.13). Subgroup analysis could not eliminate the heterogeneity, while we conducted Begg's and Egger's tests of each subgroup, suggesting that our results had almost no publication bias. We still need expand our literature numbers to reduce the heterogeneity.

As to the mechanisms of this finding, several potential aspects may account for the relationship between grip strength and cognitive impairment. First, oxidative stress and inflammation are well-known to be directly related to cognitive decline (Glade, 2010), and the onset of cognitive dysfunction (Pedersen and Febbraio, 2012). Accumulating evidences have shown that skeletal muscle has a secretory role of cytokines and other peptides, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-15, et al., which are involved in inflammatory processes (Pedersen and Febbraio, 2012) and loss of muscle strength (Aleman et al., 2011). Decline in muscle mass and strength may also reduce expression of BDNF, insulin-like growth factor-1, both of which are considered to play a role in learning and neural plasticity (Pedersen and Febbraio, 2012), so lower grip strength may cause cognitive impairment. Furthermore, weak handgrip strength may be an early sign of cognitive impairment, as handgrip strength could be reflected by change of nervous system activity or white matter integrity (Jeong et al., 2018). Previous findings suggest that brain structure may be associated with grip strength and cognitive changes (Sachdev et al., 2005, 2009). Besides, vitamin D (Vit D) may play a role between muscle and cognitive function. Vit D deficiency is strongly linked to muscle weakness and loss, suggesting that hypovitaminosis D in the elderly may be an important factor in the development of sarcopenia (Berchtold et al., 2000; Lappe and Binkley, 2015; Verde et al., 2019). It is found that the Vit D receptor is also expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and that CNS is able to synthetize calcitriol per se due to the expression of the 25-hydroxylase and 1α-hydroxylase, which has raised the hypothesis that Vit D may have a role in brain health and in cognitive performance (D'amelio and Quacquarelli, 2020).

There are some limitations in our study. First, evidence gathering from observational longitudinal studies cannot account for the cause and effect between grip strength and cognitive dysfunction. This meta-analysis aimed at the association between baseline grip strength and onset of cognitive impairment compared with cognitive performance of baseline. It seems that lower grip strength may cause cognitive decline and dementia, but it's still not enough to determine causality. Some suggested that cognitive function might precede muscle weakness (Jeong et al., 2018), others indicated that strength capacity and cognitive function might parallel each other (McGrath et al., 2020). However, based on the negative association between grip strength and the risk of cognitive impairment, it's significative for clinical work that taking grip strength as a tool to identify cognitive dysfunction early. Second, heterogeneity among studies could not be absolutely eliminated after subgroup analysis, while we performed sensitivity analysis and bias test, all of which suggested our results were reliable. However, we should still focus on the articles in this field to expand our literature sources.

In conclusion, poorer grip strength is associated with more onset of cognitive decline and dementia even subtype of dementia. Early prevention of cognitive impairment may focus on the better recognition and improvement of grip strength. More prospective studies need to be conducted to clarify the cause and effect between grip strength and cognitive impairment.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

XG and GW contributed conception and design of the study. SZ and YL searched the literature and singled out included studies. MC performed meta-analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (CN) (20170623005TC) and Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (2017C019).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Thanks are due to all authors for contributions for this paper, and we appreciate the reviewers' valuable comments. We also appreciate the funding, Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (CN) (20170623005TC) and Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (2017C019).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2021.625551/full#supplementary-material

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AD, Alzheimer's disease; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CASI, Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition); HR, hazard ratio; IL-6, interleukin-6; MeSH, Medical Subject Heading; MOOSE, meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology; NINCDS-ADRDA, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; Vit D, vitamin D.

Aleman, H., Esparza, J., Ramirez, F. A., Astiazaran, H., and Payette, H. (2011). Longitudinal evidence on the association between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein with the loss of total appendicular skeletal muscle in free-living older men and women. Age Ageing 40, 469–475. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr040

Auyeung, T. W., Lee, J. S., Kwok, T., and Woo, J. (2011). Physical frailty predicts future cognitive decline - a four-year prospective study in 2737 cognitively normal older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 690–694. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0110-9

Berchtold, M. W., Brinkmeier, H., and Muntener, M. (2000). Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol. Rev. 80, 1215–1265. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1215

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E., and Bennett, D. A. (2009). Association of muscle with the risk of Alzheimer disease and the rate of cognitive decline in community-dwelling older persons. Arch. Neurol. 66, 1339–1344. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.240

Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Boyle, P. A., Bienias, J. L., and Bennett, D. A. (2007). Grip strength and the risk of incident Alzheimer's disease. Neuroepidemiology 29, 66–73. doi: 10.1159/000109498

Buchman, A. S., Yu, L., Wilson, R. S., Boyle, P. A., Schneider, J. A., and Bennett, D. A. (2014). Brain pathology contributes to simultaneous change in physical frailty and cognition in old age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69, 1536–1544. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu117

Cabett Cipolli, G., Sanches Yassuda, M., and Aprahamian, I. (2019). Sarcopenia is associated with cognitive impairment in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 23, 525−531. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1188-8

Camargo, E. C., Weinstein, G., Beiser, A. S., Tan, Z. S., DeCarli, C., Kelly-Hayes, M., et al. (2016). Association of physical function with clinical and subclinical brain disease: the framingham offspring study. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 53, 1597–1608. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160229

Chou, M. Y., Nishita, Y., Nakagawa, T., Tange, C., Tomida, M., Shimokata, H., et al. (2019). Role of gait speed and grip strength in predicting 10-years cognitive decline among community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 19:186. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1199-7

D'amelio, P., and Quacquarelli, L. (2020). Hypovitaminosis d and aging: Is there a role in muscle and brain health? Nutrients 12:30628. doi: 10.3390/nu12030628

Doi, T., Tsutsumimoto, K., Nakakubo, S., Kim, M. J., Kurita, S., Hotta, R., et al. (2019). Physical performance predictors for incident dementia among japanese community-dwelling older adults. Phys. Therapy 99, 1132–1140. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz077

Ferlay, J., Colombet, M., Soerjomataram, I., Mathers, C., Parkin, D. M., Pineros, M., et al. (2019). Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 144, 1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937

Firth, J., Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J. A., Large, M., Rosenbaum, S., et al. (2018). Grip strength is associated with cognitive performance in schizophrenia and the general population: a UK biobank study of 476,559 participants. Schizophrenia Bullet. 44, 728–736. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby034

Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B., Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., et al. (2001). Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

Glade, M. J. (2010). Oxidative stress and cognitive longevity. Nutrition 26, 595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.09.014

Gray, S. L., Anderson, M. L., Hubbard, R. A., LaCroix, A., Crane, P. K., McCormick, W., et al. (2013). Frailty and incident dementia. J. Gerontol. A 68, 1083–1090. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt013

Hatabe, Y., Shibata, M., Ohara, T., Oishi, E., Yoshida, D., Honda, T., et al. (2020). Decline in handgrip strength from midlife to late-life is associated with dementia in a Japanese community: the hisayama study. J. Epidemiol. 30, 15–23. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20180137

Heward, J., Stone, L., Paddick, S. M., Mkenda, S., Gray, W. K., Dotchin, C. L., et al. (2018). A longitudinal study of cognitive decline in rural Tanzania: rates and potentially modifiable risk factors. Int. Psychogeriatr. 30, 1333–1343. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217002861

Hooghiemstra, A. M., Ramakers, I., Sistermans, N., Pijnenburg, Y. A. L., Aalten, P., Hamel, R. E. G., et al. (2017). Gait speed and grip strength reflect cognitive impairment and are modestly related to incident cognitive decline in memory clinic patients with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the 4C study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 846–854. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx003

Iannuzzi-Sucich, M., Prestwood, K. M., and Kenny, A. M. (2002). Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in healthy, older men and women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 57, M772–M777. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.12.M772

Ishii, H., Makizako, H., Doi, T., Tsutsumimoto, K., and Shimada, H. (2019). Associations of skeletal muscle mass, lower-extremity functioning, and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older people in Japan. J. Nutr. Health Aging 23, 35–41. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1110-9

Jeong, S., and Kim, J. (2018). Prospective association of handgrip strength with risk of new-onset cognitive dysfunction in Korean adults: a 6-years national cohort study. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 244, 83–91. doi: 10.1620/tjem.244.83

Jeong, S. M., Choi, S., Kim, K., Kim, S. M., Kim, S., and Park, S. M. (2018). Association among handgrip strength, body mass index and decline in cognitive function among the elderly women. BMC Geriatr. 18:225. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0918-9

Kim, G. R., Sun, J., Han, M., Nam, C. M., and Park, S. (2019). Evaluation of the directional relationship between handgrip strength and cognitive function: the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 48, 426–432. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz013

Lappe, J. M., and Binkley, N. (2015). Vitamin D and sarcopenia/falls. J. Clin. Densitom 18, 478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.04.015

MacDonald, S. W., Dixon, R. A., Cohen, A. L., and Hazlitt, J. E. (2004). Biological age and 12-years cognitive change in older adults: findings from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Gerontology 50, 64–81. doi: 10.1159/000075557

McGrath, R., Vincent, B. M., Hackney, K. J., Robinson-Lane, S. G., Downer, B., and Clark, B. C. (2020). The longitudinal associations of handgrip strength and cognitive function in aging Americans. J. Am. Med. Direct. Assoc. 21, 634–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.032

Moon, J. H., Moon, J. H., Kim, K. M., Choi, S. H., Lim, S., Park, K. S., et al. (2016). Sarcopenia as a predictor of future cognitive impairment in older adults. J Nutrit. Health Aging 20, 496–502. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0613-x

Pedersen, B. K., and Febbraio, M. A. (2012). Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 8, 457–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.49

Peng, T. C., Chen, W. L., Wu, L. W., Chang, Y. W., and Kao, T. W. (2019). Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 39, 2695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.12.014

Quan, M. H., Xun, P. C., Chen, C., Wen, J., Wang, Y. Y., Wang, R., et al. (2017). Walking pace and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in elderly populations: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Gerontol. Ser. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 266–270. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw121

Sachdev, P. S., Parslow, R., Wen, W., Anstey, K. J., and Easteal, S. (2009). Sex differences in the causes and consequences of white matter hyperintensities. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 946–956. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.023

Sachdev, P. S., Wen, W., Christensen, H., and Jorm, A. F. (2005). White matter hyperintensities are related to physical disability and poor motor function. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76, 362–367. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.042945

Sattler, C., Erickson, K. I., Toro, P., and Schroder, J. (2011). Physical fitness as a protective factor for cognitive impairment in a prospective population-based study in Germany. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 26, 709–718. doi: 10.3233/jad-2011-110548

Schaap, L. A., Pluijm, S. M., Deeg, D. J., and Visser, M. (2006). Inflammatory markers and loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength. Am. J. Med. 119, 526 e9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.049

Sibbett, R. A., Russ, T. C., Allerhand, M., Deary, I. J., and Starr, J. M. (2018). Physical fitness and dementia risk in the very old: a study of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921. BMC Psychiatry 18:285. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1851-3

Stang, A. (2010). Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

Stroup, D. F., Berlin, J. A., Morton, S. C., Olkin, I., Williamson, G. D., Rennie, D., et al. (2000). Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama 283, 2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

van Kan, G. A., Cesari, M., Gillette-Guyonnet, S., Dupuy, C., Vellas, B., and Rolland, Y. (2013). Association of a 7-year percent change in fat mass and muscle mass with subsequent cognitive dysfunction: the EPIDOS-Toulouse cohort. J. Cachexia, Sarcopenia Muscle 4, 225–229. doi: 10.1007/s13539-013-0112-z

Verde, Z., Giaquinta, A., Sainz, C. M., Ondina, M. D., and Araque, A. F. (2019). Bone mineral metabolism status, quality of life, and muscle strength in older people. Nutrients 11:12748. doi: 10.3390/nu11112748

Veronese, N., Stubbs, B., Trevisan, C., Bolzetta, F., De Rui, M., Solmi, M., et al. (2016). What physical performance measures predict incident cognitive decline among intact older adults? A 4.4year follow up study. Exp. Gerontol. 81, 110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.05.008

Viscogliosi, G., Di Bernardo, M. G., Ettorre, E., and Chiriac, I. M. (2017). Handgrip strength predicts longitudinal changes in clock drawing test performance. An observational study in a sample of older non-demented adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 21, 593–596. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0816-9

Weaver, J. D., Huang, M. H., Albert, M., Harris, T., Rowe, J. W., and Seeman, T. E. (2002). Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology 59, 371–378. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.3.371

Keywords: grip strength, cognitive impairment, risk, meta-analysis, longitudinal studies

Citation: Cui M, Zhang S, Liu Y, Gang X and Wang G (2021) Grip Strength and the Risk of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13:625551. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.625551

Received: 03 November 2020; Accepted: 04 January 2021;

Published: 04 February 2021.

Edited by:

Roberto Monastero, University of Palermo, ItalyReviewed by:

Cristina Moglia, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Cui, Zhang, Liu, Gang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guixia Wang, Z3dhbmcxNjhAamx1LmVkdS5jbg==; Xiaokun Gang, Z2FuZ3hrQGpsdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.