- 1Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

- 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

- 3Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture and Health, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Background: Although obesity and physical activity influence psychosocial well-being, these effects may vary based on race, gender, and their intersection. Using 6-year follow-up data of a nationally representative sample of adults over age of 50 in the United States, this study aimed to explore race by gender differences in additive effects of sustained high body mass index (BMI) and physical activity on sustained depressive symptoms (CES-D) and self-rated health (SRH).

Methods: Data came from waves 7, 8, and 10 (2004–2010) of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing national cohort started in 1992. The study enrolled a representative sample of Americans (n = 19,280) over the age of 50. Latent factors were used to calculate sustained high BMI and physical activity (predictors) and sustained poor SRH and high depressive symptoms (outcomes) based on measurements in 2004, 2006, and 2010. Age, education, and income were confounders. Multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the additive effects of BMI and physical activity on depressive symptoms and SRH, where the groups were defined based on race by gender.

Results: Group differences were apparent in the direction and significance of the association between sustained high BMI and depressive symptoms. The association between sustained high BMI and depressive symptoms was positive and significant for White women (B = 0.03, p = 0.007) and non-significant for White men (B = −0.03, p = 0.062), Black men (B = −0.02, p = 0.564) and Black women (B = 0.03, p = 0.110). No group differences were found in the paths from sustained physical activity to depressive symptoms, or from physical activity or BMI to SRH.

Conclusion: Sustained high BMI and high depressive symptoms after age 50 are positively associated only for White women. As the association between sustained health problems such as depression and obesity are not universal across race and gender groups, clinical and public health interventions and programs that simultaneously target multiple health problems may have differential effects across race by gender groups.

Introduction

Increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States has become a significant public health concern (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2014). Although, research has consistently shown that obesity impacts psychological well-being (Wynne et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2016; Global BMIMC, 2016), a growing body of evidence suggests that psychosocial correlates of obesity may depend on race (Kodjebacheva et al., 2015; Murphy et al., 2015; Kelley et al., 2016), gender (Assari and Caldwell, 2015; Kodjebacheva et al., 2015), and their intersection (Assari and Lankarani, 2015a). Whether race by gender groups differ in the link between sustained obesity and psychosocial distress is still unknown.

Research has suggested that culture may alter the link between physical and emotional problems (Miyamoto et al., 2013; Park et al., 2013; Curhan et al., 2014; Kitayama et al., 2015). Compared to East Asians, negative emotions more strongly predict poor physical and mental health in the United States (Curhan et al., 2014). Even after controlling for sociodemographic variables, negative emotions elicit higher rates of inflammatory biomarkers in American adults than in Japanese counterparts (Miyamoto et al., 2013). It has been suggested that culture may moderate the association between expression of anger and biological health risk. For instance, Americans may have a higher biological health risk due to anger traits compared to the Japanese (Park et al., 2013; Kitayama et al., 2015). Similar differences have been found between Blacks and Whites (Johnson, 1989). In a series of studies, Assari has shown that depressive symptoms and negative affect better predict subsequent change in physical health outcomes such as chronic medical conditions and mortality for Whites than Blacks (Assari and Burgard, 2015; Assari et al., 2015b, 2016a,b; Assari and Lankarani, 2016b).

Despite a disproportionately higher level of stress, chronic disease, and low socioeconomic status associated with their minority status (Williams, 1999; Franks et al., 2006; Gold et al., 2006), Blacks seem to have a higher chance of thriving despite all their environmental adversities, as evidenced by better mental health (Teti et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2014). Continuous exposure to adversities may have resulted in a systematic resilience for Blacks that help them maintain psychological well-being, even in the presence of new difficulties. Stress has also shown weaker effects on depression among Black men, compared to White men, which is consistent with such resilience (Assari and Lankarani, 2016a).

Body dissatisfaction and perceived unattractiveness to others is a mechanism behind the comorbidity between high Body Mass Index (BMI) and negative emotions (Jackson et al., 2014; Webb et al., 2014a; Ehlinger and Blashill, 2016). Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory suggests that we are not what we are, or what we think we are, but what we think other people think about us (Bandura, 1986). The Social Ecological Framework also suggests that individuals' behaviors and emotions are shaped by their social interactions and environment (Ley et al., 2015). Although, high BMI influences body image perception and body dissatisfaction (Altintas et al., 2014; Coy et al., 2014; Das and Evans, 2014; Stephen and Perera, 2014; Webb et al., 2014a,b; Laus et al., 2015), there is a wealth of literature suggesting that these associations depend on gender (Altintas et al., 2014; Coy et al., 2014; Laus et al., 2015), race and ethnicity (Mikolajczyk et al., 2012; Richmond et al., 2012; Chithambo and Huey, 2013; Thomas et al., 2013; Fletcher, 2014; Gitau et al., 2014; Pope et al., 2014; Sabik, 2015; Blostein et al., 2016), and age (Altintas et al., 2014; Pope et al., 2014). Self-image and misperception of self also vary by race, gender (Nichols et al., 2009; Lynch and Kane, 2014; Baruth et al., 2015; Gustat et al., 2016), and culture (Capodilupo and Kim, 2014; Argyrides and Kkeli, 2015; Capodilupo, 2015; O'Neal et al., 2015). A wide range of social and cultural factors such as affirmations and expectations of social network, including but not limited to opposite sex (Capodilupo and Kim, 2014; O'Neal et al., 2015) and media (Capodilupo and Kim, 2014; Capodilupo, 2015), which differently shape thin body ideals across groups (Chithambo and Huey, 2013; Capodilupo and Kim, 2014; Argyrides and Kkeli, 2015), also have a role.

In an innovative approach introduced by Kendler and Gardner (2016) and then used by Assari et al. (2016c), latent factors can be used to model sustained health problems over time, and their correlates. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), in this study we investigated the links between sustained BMI, physical activity, depressive symptoms, and self-rated health over time, using multiple measures. In contrast to many studies in the literature that are typically cross-sectional or focused on the effect of baseline risk factor on subsequent trajectories, this statistical approach (Kendler and Gardner, 2016) allows for model associations between sustained health issues over time (please see our Methods section for more details about this approach and latent variables).

Despite the well-established links between multiple health problems such as BMI, SRH, physical activity, and depressive symptoms (Okosun et al., 2001; Stunkard et al., 2003; Jokela et al., 2016; Romo-Perez et al., 2016), little is known about race by gender differences in the links between sustained health problems over time. The current study aimed to test if sustained high depressive symptoms and poor SRH similarly reflect sustained high BMI and physical inactivity in Black men and women and White men and women, using a nationally representative cohort of U.S. adults over age of 50.

Methods

Design and Setting

Data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), from the time period of 2004–2010, were used to study the effect of sustained BMI and physical activity on depressive symptoms and SRH (Assari et al., 2016c). The HRS is a longitudinal cohort study of a representative sample of American adults over the age of 50 that began in 1992. Further detailed information regarding the HRS can be found elsewhere (Heeringa and Connor, 1995).

Ethics Statement

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the HRS protocol for all years of data collection and all participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

Participants and Sampling

HRS participants were born between the years 1931 and 1941, inclusive. The HRS used a national area probability sample of United States households. The time period of 2004–2010 consisted of individuals in the HRS waves 7, 8, and 10. In the current study, we included individuals who considered their race to be White or Caucasian and Black or African American. At baseline (1992), there was a total sample size of 19,280 participants: 6705 White men (34.8%), 8860 White women (46.0%), 1468 Black men (7.6%), and 2247 Black women (11.7%).

Data Collection

Data were collected from participants using standard questionnaires and telephone or face-to-face interviews. Proxy interviews were used in situations in which participants were unable to respond for themselves. In addition to collecting extensive data on demographic, social, economic, and health information, the participants and their spouses were interviewed every two years.

Measures

Body Mass Index

Body mass index was measured using participants' self-reported height (measured in feet and inches) and weight (measured in pounds). Height and weight were converted to meters and kilograms respectively, and BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. The use of self-reported height and weight in the calculation of BMI has been validated (Stewart, 1982; Spencer et al., 2002).

Vigorous Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured by asking participants the following item regarding their participation in exercise: “On average over the last 12 months have you participated in vigorous activity or exercise three times a week or more? By vigorous physical activity, we mean things like sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labor. (He and Baker, 2004; Jenkins et al., 2008)” Responses included 3 or more times a week, 1 or 2 times a week, 1 to 3 times a month, less than once a month, or never. Higher score reflects more sustained vigorous physical activity. A single-item self-reported physical activity measure has shown reliability and validity (Milton et al., 2011).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D). The CES-D scale is a self-report scale used to measure current level of depressive symptomatology (Radloff, 1977). A modified eight-item version of the CES-D scale was used for waves 7, 8, and 10 of the HRS; participants were given a CES-D score, with a higher score indicating more depressive symptomatology.

Self-Rated Health

Self-rated health was reported by asking respondents whether their health was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. SRH was dichotomized into two categories of poor/fair vs. good/very good/excellent (Stenholm et al., 2014). Research has demonstrated that there is a strong association between poor SRH and increased risk of mortality (Idler and Angel, 1990; Idler and Benyamini, 1997).

Latent Factors

Sustained Health Problems

For each health variable (BMI, SRH, physical activity, and depressive symptoms), we created a latent variable indicating vulnerability or a sustained health problem, using three observations in 2004, 2006, and 2010 as measured indicators for a latent variable. To estimate stability of each variable, the loadings were tested across time points. The latent variables were conceptualized as indicators for stably high level of health problem(s) over the follow up period. That is, higher scores of our latent variable were indicative of more sustained health problems over 6 years, which can be potentially seen as long-term vulnerability. For instance, the path from BMI to depressive symptoms reflects the effect of sustained high BMI on sustained high depressive symptoms over a 6-year period.

Statistical Note

Univariate and bivariate analyses were done in SPSS 20.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY). Bivariate associations were tested using Pearson's correlation and paired samples t-test. We used AMOS 18.0 for multivariable analysis (Alessi, 2002; Arbuckle, 2009).

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used for multivariable data analysis (Kline, 2011). In the first step, we fitted model with no constraining of paths across the groups. In the next step, we released constraints and compared the fit with that of the previous model. We also tested models where the error variances for corresponding pretest and posttest measures were correlated. As the fit did not improve in the second model, we reported the model with released constraints. In our models, we performed multi-group SEM analysis where the group was defined based on race by gender. We compared the path coefficients between the groups for statistically significant difference.

Independent variables included physical activity and BMI. The dependent variables of interest were CES-D and SRH. Covariates used in the model were age, education, and income. Latent factors were used for the independent and dependent variables by assessing the data at three cross-sectional time points (2004, 2006, 2010) during the study. Paths were drawn from the covariates to the dependent variables and from the independent variables to the dependent variables.

Fit statistics included were Chi square, the comparative fit index (CFI) [>0.90], the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) [<0.06], and X2 to degrees of freedom ratio (Tabachnick and Fidell, 1996; Hu and Bentler, 1999; Lei and Lomax, 2005). Unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients were reported. We implemented full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to account for missing data. We considered p less than 0.05 as significant.

Results

Univariate Analysis

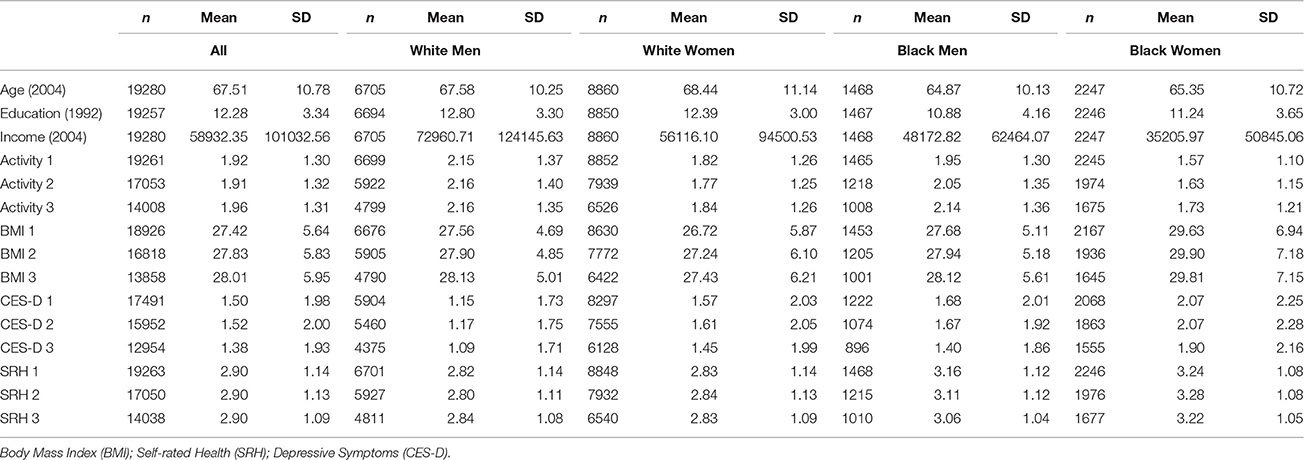

Table 1 lists the descriptive statistics for all of the variables included in the study for the pooled sample as well as based on race and gender. As shown in the table, White men had consistently more sustained physical activity than White women and Black men and women. Additionally, Black women had the highest sustained BMI across race and gender.

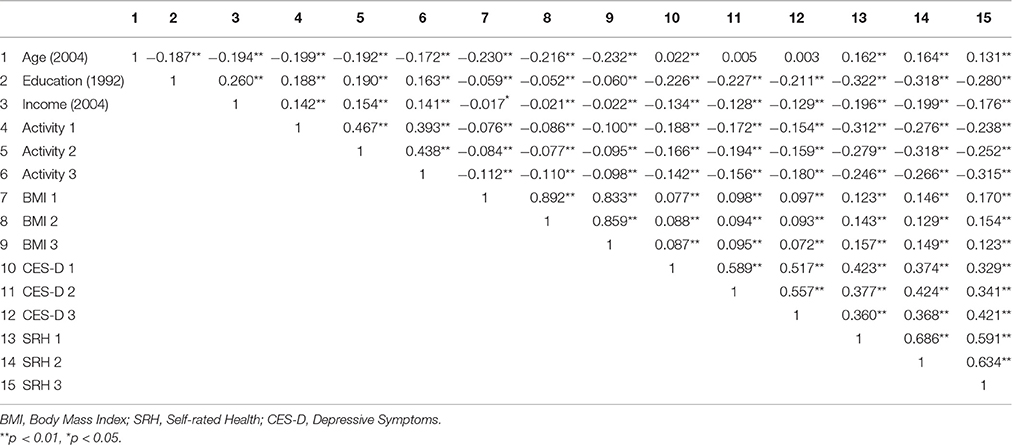

Bivariate Analysis

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the study variables in the pooled sample. BMI and CES-D showed positive but weak correlation at all three time points with p<0.01 and r ranging from 0.072 to 0.098. BMI and SRH were also positively correlated at all time points with p < 0.01 and r ranging from 0.123 to 0.170.

Multivariable Analysis

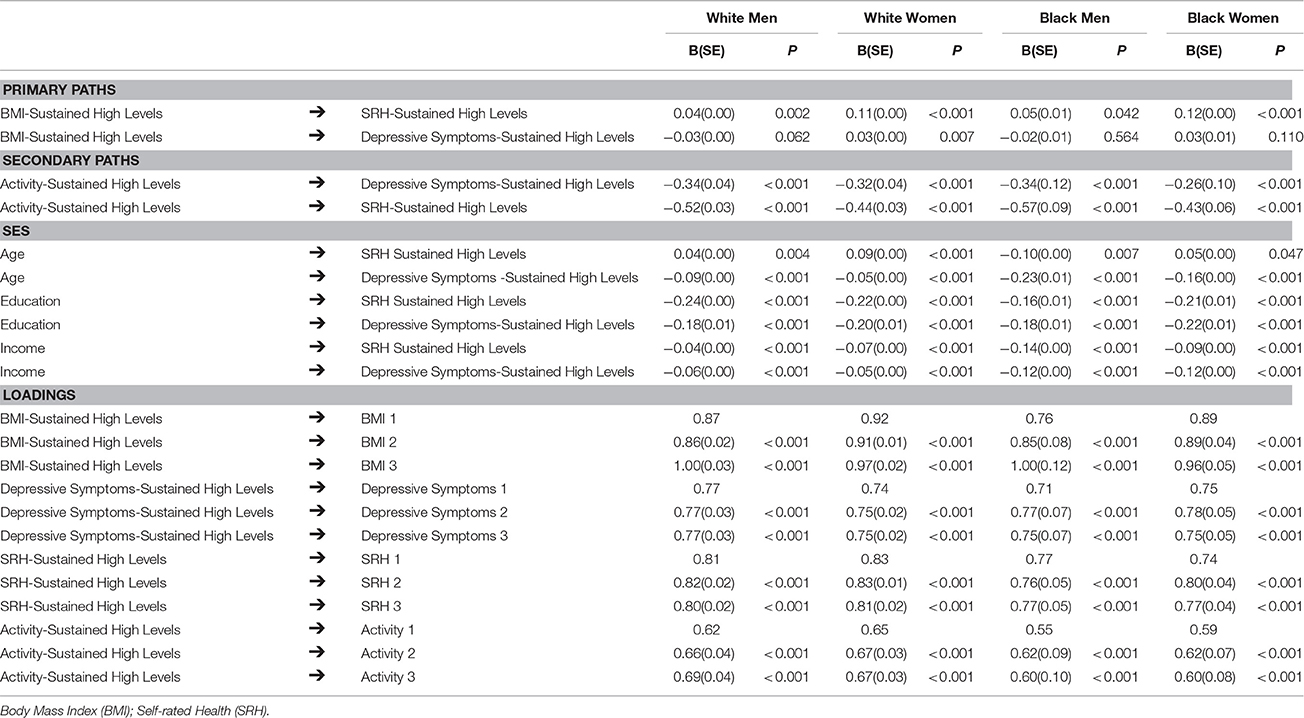

Our SEM showed good fit [p < 0.001, CMIN = 1606.146, DF = 256, CMIN/DF = 6.274, CFI = 0.988, RMSEA = 0.012 (90% CI = 0.011–0.012)]. Loadings for our independent and dependent variables are shown in Table 3. For sustained high BMI, loadings ranged from 0.76 to 1.00. Loadings ranged from 0.71 to 0.78 for sustained high depressive symptoms. The range of loadings for sustained poor SRH was 0.74 to 0.83. Loadings for sustained high physical inactivity ranged from 0.55 to 0.69.

Table 3 also displays the two primary paths of interest in the current study; (1) the association between sustained high level of BMI and high depressive symptoms, and (2) the association between sustained high level of BMI and sustained poor SRH. There were group differences in the association between sustained BMI and CES-D. The association was significant and positive for White women (B = 0.03, p = 0.007), negative and non-significant for White men (B = −0.03, p = 0.062), negative and non-significant among Black men (B = −0.02, p = 0.564) and positive and non-significant among Black women (B = 0.03, p = 0.110). The association between sustained BMI and SRH were universal with no considerable group differences.

Table 3 also displays the secondary paths of interest, which include the association between sustained physical activity and CES-D and the association between sustained physical activity and SRH. These paths were systematic and demonstrated no group differences (all p < 0.0001).

As presented in Table 3, the three covariates included in the SEM were age, education, and income. For Black men, age was protective for SRH (B = −0.10, p = 0.007). For all other groups, age was a risk factor, with B ranging from 0.04 to 0.09. The effect of age on CES-D was systematic (p < 0.0001, B ranging from −0.23 to −0.05) and showed no group differences. Income and education were consistently protective for CES-D and SRH.

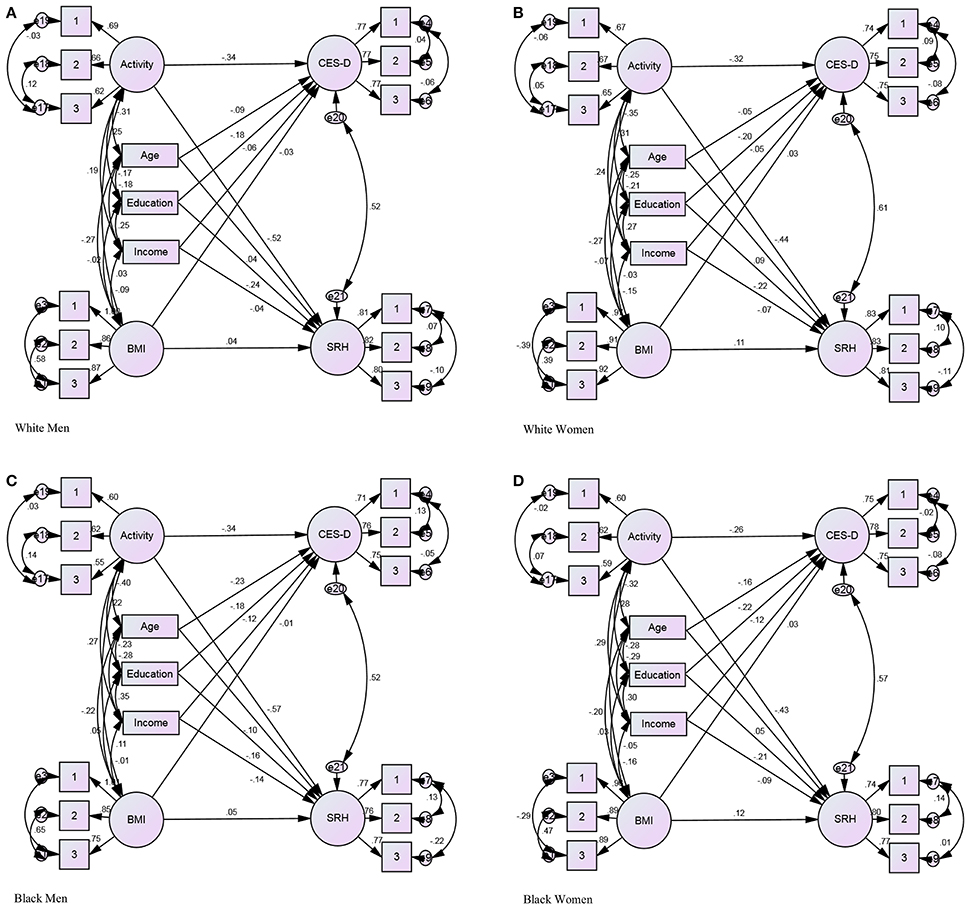

Figures 1A–D illustrate the Structural Equation Model (SEM) for race by gender group. For example, in each of the four figures, the primary paths of interest are exhibited using arrows from sustained BMI to CES-D and sustained high BMI to sustained poor SRH. The secondary paths of interest were from sustained physical inactivity to sustained high depressive symptoms and sustained physical activity to sustained poor SRH. The path from BMI to CES-D was positive and significant for White women, marginal and negative for White men, and nonsignificant for Black women (positive) and Black men (negative).

Figure 1. Structural Equation Model (SEM) based on race by gender. Dependent variables: Activity, and BMI. Independent variables: CES-D, and SRH. Covariates: Age, Education, and Income. P < 0.001, CMIN = 1606.146, DF = 256, CMIN/DF = 6.274, CFI 0.988, RMSEA 012 (011–012). (A) White Men. (B) White Women. (C) Black Men (D) Black Women.

Discussion

The current study used a nationally representative sample of Americans older than 50 to assess whether sustained high levels of depressive symptoms and poor SRH universally reflect sustained high BMI and physical inactivity across race by gender groups. The results suggest that sustained high BMI had a positive and significant association with sustained high level of depressive symptoms in White women but not in White men, Black men, and Black women. The effect of sustained physical activity on sustained high level of depressive symptoms and SRH, as well as the effect of sustained BMI on sustained poor SRH, were, however, universal and similar across race by gender groups.

These findings suggest that demographic factors, environment, or cultural characteristics may influence how sustained obesity and depressive symptoms are associated (Park et al., 2013). Previous cross-sectional (Gavin et al., 2010; Hicken et al., 2013; Assari, 2014a,c; Assari and Caldwell, 2015; Kodjebacheva et al., 2015) and longitudinal (Hawkins et al., 2015) research had shown that the link between obesity and depressive symptoms depends on the intersection of race and gender (Assari, 2014b). The way in which physical activity shapes our perceived health is, however, universal. If an individual is active, he or she will feel healthy and less depressed, irrespective of group membership. Similarly, an individual with high BMI will feel less healthy regardless of group. For sustained obesity and depressive symptoms, comorbidity is not universal.

These findings coincide with the results of other studies on the differential effects of the association between obesity and major depressive disorder by race and gender (Gavin et al., 2010; Hicken et al., 2013; Assari, 2014a,b,c; Assari and Caldwell, 2015; Hawkins et al., 2015; Kodjebacheva et al., 2015). The results of this study in Black men and women are in agreement with a number of studies examining the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis, which supports that higher body mass index and obesity in women is associated with less depression (Jasienska et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011). This hypothesis is also demonstrated among adolescent girls (Revah-Levy et al., 2011) as well as adult and elderly populations in Asian countries (Li et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011). The “Jolly Fat” hypothesis was also reflected among aging Asian men (Li et al., 2004; Han et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2013). One study found that the desire to be of smaller size was not as great for Blacks compared to Whites, and Black women tended to feel that their size was considered satisfactory by their significant others (Kemper et al., 1994). Black women have more positive attitudes toward obesity and less internalized stigmatization (Latner et al., 2005).

Culture may influence cognitive and emotional elements that are essential for the perception of obesity and associated weight management behaviors (Assari and Lankarani, 2015a,b). One study found that urban, obese Black men who felt healthy or had fewer comorbid conditions had a greater misperception of healthy weight (Godino et al., 2010). Another study reported that about half of young African-American men with normal BMI desired to be heavier, while approximately 60% of overweight men were satisfied or wished to be heavier (Gilliard et al., 2007). The absence of strong negative social pressure combined with a positive body image perception among Black women (Kumanyika et al., 1993) and the desire of Black men to be of larger size (Jackson et al., 2010) contribute to a sustained higher BMI in this population. In addition, James Jackson has hypothesized that compared to Whites, Blacks engaged in unhealthy behaviors to cope with stressors of living in chronically stressful environments (Jackson et al., 2010; Mezuk et al., 2013). Over the life course, Black men demonstrate increased rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug use, while Black women respond by overeating (Jackson et al., 2010). However, in the current study, there were no gender by race differences.

Much of the literature concerning the effects of life's adversities on Blacks document the disadvantages and weaknesses but hardly the strengths that have resulted in this population. Examples include forms of “double jeopardy” for Blacks in health and healthcare (Kirby and Kaneda, 2013) and academic learning (Taylor and Walton, 2011), the adverse effects of racism and discrimination (Williams, 1999; Chae et al., 2011; Gibbons et al., 2012), and the cumulative negative effects of multiple disadvantages (Zemore et al., 2011; Pais, 2014; Umberson et al., 2014). However, Teti et al. found that Black men who tackled challenges such as racism, incarceration, and unemployment demonstrated resilience amid these stressors (Teti et al., 2012). It has also been found that Black women exhibited resilience in spite of traumatic experiences (Henderson et al., 2015) and in order to cope with depression (Ward et al., 2014). It is this resilience among Blacks that allows this population to thrive and remain optimistic, thus resulting in better mental health outcomes than their counterparts. However, the resilience that this population demonstrates is not specific to the measures in the current study, but rather a resilience that is displayed across a variety of risk factors and outcomes. It is a systemic resilience as a result of the life course, and it reflects the contextual factors of one's life. James Jackson developed the Law of Small Effects, an explanation that suggests that physical and mental health disparities are effects of accumulated small differences through the life course as Blacks age (Jackson, 2011; Brown et al., 2014). Because the Law of Small Effects indicates that there is no single cause of health disparities but rather an accumulation of a variety of factors (Jackson, 2011; Brown et al., 2014), we propose that interventions will influence Blacks with smaller effects than Whites, thus the Law of Small Effects.

Corey Keyes hypothesizes a “Black advantage” in mental health, possibly due to flourishing in the presence of adversity (Keyes, 2007), to explain Blacks' lower rates of common mental disorders and a greater mental resilience despite adversities, stress, discrimination, and other risk factors (Keyes, 2009). Across all age cohorts, family satisfaction and contact with friends were found to be the most important contributing factors of general life satisfaction for Blacks (Adams and Jackson, 2000). Black-White differences may be due to culture, which shapes resilience (Keyes, 2009; Teti et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2015), body image and perception (Altintas et al., 2014; Coy et al., 2014; Das and Evans, 2014; Stephen and Perera, 2014; Webb et al., 2014b; Laus et al., 2015), and social support (Adams and Jackson, 2000), all influencing mental health. Culture is a powerful influence on health outcomes as described by Kitayama et al. in the cultural moderation hypothesis (Park et al., 2013).

There are public health implications for the results of this study (Leon et al., 2014; Assari et al., 2015a; Krishna et al., 2015). Although, Black men and women with sustained high BMI do not report high depressive symptoms, there should still exist efforts to reduce the sustained high levels of BMI among Black men and women, similar to Whites. In order to reduce burden of obesity, we need multidisciplinary approaches that address the context, culture, and environment of populations that may be allowed higher body mass without stigma. Active involvement, partnership and communication with Black communities is vital to better understand cultural factors that may operate as barriers for obesity prevention in subpopulations.

Clinical and public health interventions that target healthy BMI may have differential effects on comorbid health outcomes for Blacks compared to Whites. Tailoring according to group membership may influence the association between high BMI and mental health needs. Therefore, universal interventions may not be ideal for diverse populations, as Whites and Blacks with high BMI have different patterns of comorbidities. To maximize benefits, interventions and programs may be tailored to race and gender to match that of the target population. One study that implemented a weight loss intervention among Black women reported that those with the greatest fat mass loss improved insulin sensitivity while those with fat mass gain, which was common, had reduced insulin sensitivity following the 6-month program (Leon et al., 2014). These results demonstrate that additional support may be beneficial for Black women in weight loss programs who fail to achieve optimal weight loss goals.

This study is subject to a few limitations. Attrition is a concern in longitudinal cohort studies. Loss to follow-up may have led to missing data that may skew the results. Another limitation is the use of self-reported weight and height for BMI calculation. Although, research finds that this measure is valid, self-reported data is still subject to bias and under/overestimation. Also, the use of the single-item physical activity measure may fail to capture participants' true physical activity levels. Lastly, the unbalanced sample size resulted in different statistical power across groups. The current study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature as it is one of the first studies on sustained health risk over time. A nationally representative sample, large sample size, length of follow up, and the intersectional approach are key strengths in the current study. This study used an innovative statistical approach introduced by Kendler (Kendler and Gardner, 2016). Further research should be done on risk factors and outcomes associated with sustained health issues over time.

In conclusion, how sustained high level of BMI and sustained depressive symptoms are associated varies across race by gender groups. Sustained high depressive symptoms better reflect sustained high BMI level for White women than White men, Black men, or Black women. The association between sustained BMI and depressed affect is not uniform, but specific to the race by gender intersection. Clinical and public health interventions and programs that are tailored to the target populations may be more effective.

Author Contributions

JC: Drafted the manuscript and revised the manuscript; SA: Developed the conceptual model of the study, analyzed the data, and contributed to the drafts. Both authors confirmed the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Assari is supported by the Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund and the Richard Tam Foundation at the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We used public use dataset available at the study website at University of Michigan. The HRS is conducted by the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provided funding for the Health and Retirement Study (U01 AG09740). This work was supported by the MICHR Clinical & Translational research (PI = George Mashour UL1TR000433, TL1TR000435) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

References

Adams, V. H. III, and Jackson, J. S. (2000). The contribution of hope to the quality of life among aging African Americans: 1980-1992. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 50, 279–295. doi: 10.2190/AWB4-7CLU-A2EP-BQLF

Alessi, P. (2002). Professional iOS Database Applications, and Programming, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group.

Altintas, A., Aşci, F. H., Kin-Isler, A., Güven-Karahan, B., Kelecek, S., Özkan, A., et al. (2014). The role of physical activity, body mass index and maturity status in body-related perceptions and self-esteem of adolescents. Ann. Hum. Biol. 41, 395–402. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2013.857721

Argyrides, M., and Kkeli, N. (2015). Predictive factors of disordered eating and body image satisfaction in cyprus. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 48, 431–435. doi: 10.1002/eat.22310

Assari, S. (2014a). Additive effects of anxiety and depression on body mass index among Blacks: role of ethnicity and gender. Int. Cardiovasc. Res. J. 8, 44–51.

Assari, S. (2014b). The link between mental health and obesity: role of individual and contextual factors. Int. J. Prev. Med. 5, 247–249.

Assari, S. (2014c). Association between obesity and depression among American Blacks: role of ethnicity and gender. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 1, 36–44. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0007-5

Assari, S., and Burgard, S. (2015). Black-White differences in the effect of baseline depressive symptoms on deaths due to renal diseases: 25 year follow up of a nationally representative community sample. J. Renal Inj. Prev. 4:127. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.27

Assari, S., Burgard, S., and Zivin, K. (2015b). Long-term reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms and number of chronic medical conditions: longitudinal support for black–white health paradox. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2, 589–597. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0116-9

Assari, S., and Caldwell, C. H. (2015). Gender and ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression among black adolescents. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2, 481–493. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0096-9

Assari, S., Caldwell, C. H., and Zimmerman, M. A. (2015a). Low parental support in late adolescence predicts obesity in young adulthood; Gender differences in a 12-year cohort of African Americans. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 14:47. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0176-8

Assari, S., and Lankarani, M. M. (2015a). Mediating effect of perceived overweight on the association between actual obesity and intention for weight control; role of race, ethnicity, and gender. Int. J. Prev. Med. 6:102. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.167616

Assari, S., and Lankarani, M. M. (2015b). The association between obesity and weight loss intention weaker among Blacks and men than whites and women. J Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2, 414–420. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0115-x

Assari, S., and Lankarani, M. M. (2016a). Association between stressful life events and depression; intersection of race and gender. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 3, 349–356. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0160-5

Assari, S., and Lankarani, M. M. (2016b). chronic Medical conditions and negative affect; racial Variation in reciprocal associations over time. Front. Psychiatry 7:140 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00140

Assari, S., Moazen-Zadeh, E., Lankarani, M. M., and Micol-Foster, V. (2016b). Race, depressive symptoms, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Front. Public Health. 4:40. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00040

Assari, S., Nikahd, A., Malekahmadi, M. R., Lankarani, M. M., and Zamanian, H. (2016c). Race by gender group differences in the protective effects of socioeconomic factors against sustained health problems across five domains. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0291-3. [Epub ahead of print].

Assari, S., Sonnega, A., Pepin, R., and Leggett, A. (2016a). Residual effects of restless sleep over depressive symptoms on chronic medical conditions: race by gender differences. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0202-z. [Epub ahead of print].

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action : A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Baruth, M., Sharpe, P. A., Magwood, G., Wilcox, S., and Schlaff, R. A. (2015). Body size perceptions among overweight and obese African American Women. Ethn. Dis. 25, 391–398. doi: 10.18865/ed.25.4.391

Blostein, F., Assari, S., and Caldwell, C. H. (2016). Gender and ethnic differences in the association between body image dissatisfaction and binge eating disorder among Blacks. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0255-7. [Epub ahead of print].

Brown, C. S., Baker, T. A., Mingo, C. A., Harden, J. T., Whitfield, K., Aiken-Morgan, A. T., et al. (2014). A review of our roots: blacks in gerontology. Gerontologist 54, 108–116. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt103

Capodilupo, C. M. (2015). One size does not fit all: using variables other than the thin ideal to understand Black women's body image. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 21, 268–278. doi: 10.1037/a0037649

Capodilupo, C. M., and Kim, S. (2014). Gender and race matter: the importance of considering intersections in Black women's body image. J. Couns. Psychol. 61, 37–49. doi: 10.1037/a0034597

Chae, D. H., Lincoln, K. D., and Jackson, J. S. (2011). Discrimination, attribution, and racial group identification: implications for psychological distress among Black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001-2003). Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 81, 498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x

Chang, T., Ravi, N., Plegue, M. A., Sonneville, K. R., and Davis, M. M. (2016). Inadequate hydration, BMI, and obesity among US adults: NHANES 2009-2012. Ann. Fam. Med. 14, 320–324. doi: 10.1370/afm.1951

Chithambo, T. P., and Huey, S. J. (2013). Black/white differences in perceived weight and attractiveness among overweight women. J. Obes. 2013:320326. doi: 10.1155/2013/320326

Coy, A. E., Green, J. D., and Price, M. E. (2014). Why is low waist-to-chest ratio attractive in males? The mediating roles of perceived dominance, fitness, and protection ability. Body Image 11, 282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.04.003

Curhan, K. B., Sims, T., Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S., Karasawa, M., Kawakami, N., et al. (2014). Just how bad negative affect is for your health depends on culture. Psychol. Sci. 25, 2277–2280. doi: 10.1177/0956797614543802

Das, B. M., and Evans, E. M. (2014). Understanding weight management perceptions in first-year college students using the health belief model. J. Am. Coll. Health. 62, 488–497. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.923429

Dong, Q., Liu, J. J., Zheng, R. Z., Dong, Y. H., Feng, X. M., Li, J., et al. (2013). Obesity and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a survey in the rural area of Chizhou, Anhui province. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 227–232. doi: 10.1002/gps.3815

Ehlinger, P. P., and Blashill, A. J. (2016). Self-perceived vs. actual physical attractiveness: associations with depression as a function of sexual orientation. J. Affect. Disord. 189, 70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.071

Fletcher, J. M. (2014). The interplay between gender, race and weight status: self perceptions and social consequences. Econ. Hum. Biol. 14, 79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.03.003

Franks, P., Muennig, P., Lubetkin, E., and Jia, H. (2006). The burden of disease associated with being African-American in the United States and the contribution of socio-economic status. Soc. Sci. Med. 62, 2469–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.035

Gavin, A. R., Rue, T., and Takeuchi, D. (2010). Racial/ethnic differences in the association between obesity and major depressive disorder: findings from the comprehensive psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Public Health Rep. 125, 698–708.

Gibbons, F. X., O'Hara, R. E., Stock, M. L., Gerrard, M., Weng, C. Y., and Wills, T. A. (2012). The erosive effects of racism: reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404

Gilliard, T. S., Lackland, D. T., Mountford, W. K., and Egan, B. M. (2007). Concordance between self-reported heights and weights and current and ideal body images in young adult African American men and women. Ethn. Dis. 17, 617–623.

Gitau, T. M., Micklesfield, L. K., Pettifor, J. M., and Norris, S. A. (2014). Eating attitudes, body image satisfaction and self-esteem of South African Black and White male adolescents and their perception of female body silhouettes. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 26, 193–205. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2014.901224

Global BMIMC, (2016). Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 388, 776–786. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1

Godino, J. G., Lepore, S. J., and Rassnick, S. (2010). Relation of misperception of healthy weight to obesity in urban black men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 18, 1318–1322. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.395

Gold, R., Michael, Y. L., Whitlock, E. P., Hubbell, F. A., Mason, E. D., Rodriguez, B. L., et al. (2006). Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and lifetime morbidity burden in the women's health initiative: a cross-sectional analysis. J. Womens. Health (Larchmt). 15, 1161–1173. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1161

Gustat, J., Carton, T. W., Shahien, A. A., and Andersen, L. (2016). Body image satisfaction among Blacks. Health Educ. Behav. doi: 10.1177/1090198116644181. [Epub ahead of print].

Han, C., Jo, S. A., Seo, J. A., Kim, B. G., Kim, N. H., Jo, I., et al. (2009). Adiposity parameters and cognitive function in the elderly: application of “Jolly Fat” hypothesis to cognition. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 49, e133–e138. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.11.005

Hawkins, M. A., Miller, D. K., and Stewart, J. C. (2015). A 9-year, bidirectional prospective analysis of depressive symptoms and adiposity: the African American Health Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 192–199. doi: 10.1002/oby.20893

He, X. Z., and Baker, D. W. (2004). Body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of decline in overall health and physical functioning in late middle age. Am. J. Public Health 94, 1567–1573. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1567

Heeringa, S. G., and Connor, J. H (1995). Technical Description of the Health and Retirement Survey Sample design. Available online at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu

Henderson, D. X., Bond, G. D., Alderson, C. J., and Walker, W. R. (2015). This too shall pass: evidence of coping and fading emotion in African Americans' memories of violent and nonviolent death. Omega (Westport). 71, 291–311. doi: 10.1177/0030222815572601

Hicken, M. T., Lee, H., Mezuk, B., Kershaw, K. N., Rafferty, J., and Jackson, J. S. (2013). Racial and ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression in women. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 22, 445–452. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4111

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Idler, E. L., and Angel, R. J. (1990). Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am. J. Public Health 80, 446–452. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.80.4.446

Idler, E. L., and Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 38, 21–37. doi: 10.2307/2955359

Jackson, J. (2011). Racial and Ethnic Minority Group Dispari- Ties and the Affordances Model. Paper Presented at the Meeting of The Gerontological Society of America, (Boston, MA).

Jackson, J. S., Knight, K. M., and Rafferty, J. A. (2010). Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am. J. Public Health 100, 933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446

Jackson, K. L., Janssen, I., Appelhans, B. M., Kazlauskaite, R., Karavolos, K., Dugan, S. A., et al. (2014). Body image satisfaction and depression in midlife women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 17, 177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0416-9

Jasienska, G., Ziomkiewicz, A., Górkiewicz, M., and Pajak, A. (2005). Body mass, depressive symptoms and menopausal status: an examination of the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis. Womens Health Issues. 15, 145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.02.002

Jenkins, K., Ofstedal, M. B., and Weir, D. (2008 February). Documentation of Health Behaviors and Risk Factors Measured in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD). Available online at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-010.pdf

Johnson, E. H. (1989). The role of the experience and expression of anger and anxiety in elevated blood pressure among black and white adolescents. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 81, 573–584.

Jokela, M., Berg, V., Silventoinen, K., Batty, G. D., Singh-Manoux, A., Kaprio, J., et al. (2016). Body mass index and depressive symptoms: testing for adverse and protective associations in two twin cohort studies. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 19, 306–311. doi: 10.1017/thg.2016.14

Kelley, E. A., Bowie, J. V., Griffith, D. M., Bruce, M., Hill, S., Thorpe, R. J., et al. (2016). Geography, Race/Ethnicity, and Obesity Among Men in the United States. Am. J. Mens. Health 10, 228–236. doi: 10.1177/1557988314565811

Kemper, K. A., Sargent, R. G., Drane, J. W., Valois, R. F., and Hussey, J. R. (1994). Black and white females' perceptions of ideal body size and social norms. Obes. Res. 2, 117–126. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00637.x

Kendler, K. S., and Gardner, C. O. (2016). Depressive vulnerability, stressful life events and episode onset of major depression: a longitudinal model. Psychol. Med. 46, 1865–1874. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000349

Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am. Psychol. 62, 95–108. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Keyes, C. L. (2009). The Black-White paradox in health: flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. J. Pers. 77, 1677–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x

Kim, E., Song, J. H., Hwang, J. Y., Ahn, K., Kim, J., Koh, Y. H., et al. (2010). Obesity and depressive symptoms in elderly Koreans: evidence for the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis from the Ansan Geriatric (AGE) Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 51, 231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.10.014

Kirby, J. B., and Kaneda, T. (2013). ‘Double jeopardy’ measure suggests Blacks and hispanics face more severe disparities than previously indicated. Health Aff. (Millwood). 32, 1766–1772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0434

Kitayama, S., Park, J., Boylan, J. M., Miyamoto, Y., Levine, C. S., Markus, H. R., et al. (2015). Expression of anger and ill health in two cultures: an examination of inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Psychol. Sci. 26, 211–220. doi: 10.1177/0956797614561268

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kodjebacheva, G., Kruger, D. J., Rybarczyk, G., and Cupal, S. (2015). Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the association between depressive symptoms and higher body mass index. J. Public Health (Oxf). 37, 419–426. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu062

Krishna, A., Razak, F., Lebel, A., Smith, G. D., and Subramanian, S. V. (2015). Trends in group inequalities and interindividual inequalities in BMI in the United States, 1993–2012. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 598–605. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100073

Kumanyika, S., Wilson, J. F., and Guilford-Davenport, M. (1993). Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of black women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 93, 416–422. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)92287-8

Latner, J. D., Stunkard, A. J., and Wilson, G. T. (2005). Stigmatized students: age, sex, and ethnicity effects in the stigmatization of obesity. Obes. Res. 13, 1226–1231. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.145

Laus, M. F., Costa, T. M., and Almeida, S. S. (2015). Gender differences in body image and preferences for an ideal silhouette among Brazilian undergraduates. Eat. Behav. 19, 159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.09.003

Lei, M., and Lomax, R. G. (2005). The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 12, 1–27. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1201_1

Leon, B., Miller, B. V. III., Zalos, G., Courville, A. B., Sumner, A. E., Powell-Wiley, T. M., et al. (2014). Weight loss programs may have beneficial or adverse effects on fat mass and insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese black women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 1, 140–147. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0006-6

Ley, C., Barrio, M. R., and Leach, L. (2015).Social-ecological, motivational and volitional factors for initiating and maintaining physical activity in the context of HIV. Open AIDS J. 9, 96–103. doi: 10.2174/1874613601509010096

Li, Z. B., Ho, S. Y., Chan, W. M., Ho, K. S., Li, M. P., Leung, G. M., et al. (2004). Obesity and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 19, 68–74. doi: 10.1002/gps.1040

Lynch, E. B., and Kane, J. (2014). Body size perception among African American women. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 46, 412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.03.002

Mezuk, B., Abdou, C. M., Hudson, D., Kershaw, K. N., Rafferty, J. A., Lee, H., et al. (2013). “White Box” epidemiology and the social neuroscience of health behaviors: the environmental affordances model. Soc. Ment. Health 3, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/2156869313480892

Mikolajczyk, R. T., Iannotti, R. J., Farhat, T., and Thomas, V. (2012). Ethnic differences in perceptions of body satisfaction and body appearance among, U.S. schoolchildren: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 12:425. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-425

Milton, K., Bull, F. C., and Bauman, A. (2011). Reliability and validity testing of a single-item physical activity measure. Br. J. Sports Med. 45, 203–208. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068395

Miyamoto, Y., Boylan, J. M., Coe, C. L., Curhan, K. B., Levine, C. S., Markus, H. R., et al. (2013). Negative emotions predict elevated interleukin-6 in the United States but not in Japan. Brain Behav. Immun. 34, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.173

Murphy, C. C., Martin, C. F., and Sandler, R. S. (2015).Racial differences in obesity measures and risk of colorectal adenomas in a large screening population. Nutr. Cancer 67, 98–104. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.976316

Nichols, S. D., Dookeran, S. S., Ragbir, K. K., and Dalrymple, N. (2009). Body image perception and the risk of unhealthy behaviours among university students. West Indian Med. J. 58, 465–471.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), (2014). Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators: Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Available online at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020_LHI_Nut_PhysActiv_0.pdf

Okosun, I. S., Choi, S., Matamoros, T., and Dever, G. E. (2001). Obesity is associated with reduced self-rated general health status: evidence from a representative sample of white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Prev. Med. 32, 429–436. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0840

O'Neal, C. W., Arnold, A. L., Lucier-Greer, M., Wickrama, K. A., and Bryant, C. M. (2015). Economic pressure and health and weight management behaviors in African American couples: a family stress perspective. J. Health Psychol. 20, 625–637. doi: 10.1177/1359105315579797

Pais, J. (2014). Cumulative structural disadvantage and racial health disparities: the pathways of childhood socioeconomic influence. Demography 51, 1729–1753. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0330-9

Park, J., Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Coe, C. L., Miyamoto, Y., Karasawa, M., et al. (2013). Social status and anger expression: the cultural moderation hypothesis. Emotion 13, 1122–1131. doi: 10.1037/a0034273

Pope, M., Corona, R., and Belgrave, F. Z. (2014). Nobody's perfect: a qualitative examination of African American maternal caregivers' and their adolescent girls' perceptions of body image. Body Image 11, 307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.04.005

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Revah-Levy, A., Speranza, M., Barry, C., Hassler, C., Gasquet, I., Moro, M. R., et al. (2011). Association between Body Mass Index and depression: the “fat and jolly” hypothesis for adolescents girls. BMC Public Health. 11:649. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-649

Richmond, T. K., Austin, S. B., Walls, C. E., and Subramanian, S. V. (2012). The association of body mass index and externally perceived attractiveness across race/ethnicity, gender, and time. J. Adolesc. Health 50, 74-9 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.007

Romo-Perez, V., Souto, D., and Mota, J. (2016). Walking, body mass index, and self-rated health in a representative sample of Spanish adults. Cad. Saude Publica 32, 1–10. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00166414

Sabik, N. J. (2015). Ageism and body esteem: associations with psychological well-being among late middle-aged African American and European American women. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 70, 191–201. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt080

Spencer, E. A., Appleby, P. N., Davey, G. K., and Key, T. J. (2002). Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 5, 561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322

Stenholm, S., Pentti, J., Kawachi, I., Westerlund, H., Kivimäki, M., and Vahtera, J. (2014). Self-rated health in the last 12 years of life compared to matched surviving controls: the Health and Retirement Study. PLoS ONE 9:e107879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107879

Stephen, I. D., and Perera, A. T. (2014). Judging the differences between women's attractiveness and health: is there really a difference between judgments made by men and women? Body Image 11, 183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.11.007

Stewart, A. L. (1982). The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J. Chronic Dis. 35, 295–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6

Stunkard, A. J., Faith, M. S., and Allison, K. C. (2003). Depression and obesity. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 330–337. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00608-5

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Taylor, V. J., and Walton, G. M. (2011). Stereotype threat undermines academic learning. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 1055–1067. doi: 10.1177/0146167211406506

Teti, M., Martin, A. E., Ranade, R., Massie, J., Malebranche, D. J., Tschann, J. M., et al. (2012). “I'm a keep rising. I'm a keep going forward, regardless”: exploring Black men's resilience amid sociostructural challenges and stressors. Qual. Health Res. 22, 524–533. doi: 10.1177/1049732311422051

Thomas, S., Ness, R. B., Thurston, R. C., Matthews, K., Chang, C. C., and Hess, R. (2013). Racial differences in perception of healthy body weight in midlife women: results from the Do stage transitions result in detectable effects study. Menopause 20, 269–273. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31826e7574

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Thomas, P. A., Liu, H., and Thomeer, M. B. (2014). Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 55, 20–38. doi: 10.1177/0022146514521426

Ward, E. C., Mengesha, M. M., and Issa, F. (2014). Older African American women's lived experiences with depression and coping behaviours. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 21, 46–59. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12046

Webb, H. J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., and Donovan, C. L. (2014a). The appearance culture between friends and adolescent appearance-based rejection sensitivity. J. Adolesc. 37, 347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.008

Webb, J. B., Butler-Ajibade, P., and Robinson, S. A. (2014b). Considering an affect regulation framework for examining the association between body dissatisfaction and positive body image in Black older adolescent females: does body mass index matter? Body Image 11, 426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.002

Williams, D. R. (1999). Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 896, 173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x

Wynne, C., Comiskey, C., Hollywood, E., Quirke, M. B., O'Sullivan, K., and McGilloway, S. (2014). The relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of life in urban disadvantaged children. Qual. Life Res. 23, 1895–1905. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0634-7

Yu, N. W., Chen, C. Y., Liu, C. Y., Chau, Y. L., and Chang, C. M. (2011). Association of body mass index and depressive symptoms in a Chinese community population: results from the Health Promotion Knowledge, Attitudes, and Performance Survey in Taiwan. Chang Gung Med. J. 34, 620–627.

Keywords: ethnic groups, Blacks, Whites, depressive symptoms, obesity, physical activity, self-rated health, well-being

Citation: Carter JD and Assari S (2017) Sustained Obesity and Depressive Symptoms over 6 Years: Race by Gender Differences in the Health and Retirement Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8:312. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00312

Received: 08 September 2016; Accepted: 06 December 2016;

Published: 04 January 2017.

Edited by:

P. Hemachandra Reddy, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, USAReviewed by:

Ramesh Kandimalla, Texas Tech University, USAGaurav Kumar Gulati, University of Washington, USA

Copyright © 2017 Carter and Assari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shervin Assari, YXNzYXJpQHVtaWNoLmVkdQ==

Julia D. Carter

Julia D. Carter Shervin Assari

Shervin Assari