- 1College of Food Science and Engineering, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China

- 2Animal Quarantine Laboratory, Jiangsu Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Nanjing, China

- 3Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Laurel, MD, USA

Aptamers are single stranded DNA or RNA ligands, which can be selected by a method called systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX); and they can specifically recognize and bind to their targets. These unique characteristics of aptamers offer great potentials in applications such as pathogen detection and biomolecular screening. Pathogen detection is the critical means in detecting and identifying the problems related to public health and food safety; and only the rapid, sensitive and efficient detection technologies can enable the users to make the accurate assessments on the risks of infections (humans and animals) or contaminations (foods and other commodities) caused by various pathogens. This article reviews the development in the field of the aptamer-based approaches for pathogen detection, including whole-cell SELEX and Genomic SELEX. Nowadays, a variety of aptamer-based biosensors have been developed for pathogen detection. Thus, in this review, we also cover the development in aptamer-based biosensors including optical biosensors for multiple pathogen detection by multiple-labeling or label-free models such as fluorescence detection and surface plasmon resonance, electrochemical biosensors and lateral chromatography test strips, and their applications in pathogen detection and biomolecular screening. While notable progress has been made in the field in the last decade, challenges or drawbacks in their applications such as pathogen detection and biomolecular screening remain to be overcome.

Introduction

Bacteria are microorganisms that are a few micrometers in length and morphologically described as rod, sphere or spiral. They can sense and respond to temperature and pH changes, nutritional starvation or new food sources, toxins, stresses, and quorum sensing signals (Salis et al., 2009). Pathogens are harmful species that cause infections and contagious diseases that result in many serious complications. Common bacterial pathogens and their complications include Escherichia coli and Salmonella (food poisoning), Helicobacter pylori (gastritis and ulcers), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (sexually transmitted disease), N. meningitides (meningitis), Staphylococcus aureus (boils, cellulitis, abscesses, wound infections, toxic shock syndromes, pneumonia, and food poisoning), and Streptococcus spp. (pneumonia, meningitis, ear infections, and pharyngitis). Worldwide, infectious diseases account for nearly 40% of the estimated total 50 million deaths annually (Ivnitski et al., 1999).

Detection and identification of microbial pathogens are crucial for public health and food safety (Law et al., 2015). Areas where detection of microbial pathogens is critical include clinical diagnosis, water and environmental analysis, food safety and biodefense. Currently, microbial culture-based tests and molecular assays (immunological or nucleic acid technologies) are among the most commonly used methodologies in detection and identification of microbial pathogens (Torres-Chavolla and Alocilja, 2009).

Aptamers are single stranded DNA or RNA ligands that can be selected for different targets starting from a huge library of molecules containing randomly created sequences (Tombelli et al., 2005); and these specifically selected nucleic acid sequences can bind to a wide range of non-nucleic acid targets with high affinity and specificity (Jayasena, 1999). Aptamers usually vary in length from 25 to 90 bases, and their typical structural motifs can be classified into stems (Tok and Cho, 2000), internal loops, purine-rich bulges, hairpin structures, hairpins, pseudoknots (Tuerk et al., 1992), kissing complexes (Boiziau et al., 1999), or G-quadruplex structures (Bock et al., 1992). The unique characteristics of aptamers such as their highly specific binding affinity to non-nucleic acid targets offer great potentials in the development of fast and efficient point-of-care assays for pathogen detection (Jayasena, 1999).

The selection process of aptamers is called systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX), which was developed by two independent groups in 1990 (Ellington and Szostak, 1990; Tuerk and Gold, 1990). Such work laid out the foundation for later developments of aptamers and aptamer-based technologies. Since then, SELEX has become a vital tool in selection of aptamers, transforming the great potential of aptamers and their related technologies in pathogen detection and biomolecular screening to a reality.

Selection of Aptamers Against Bacterial Pathogens

Conventional SELEX

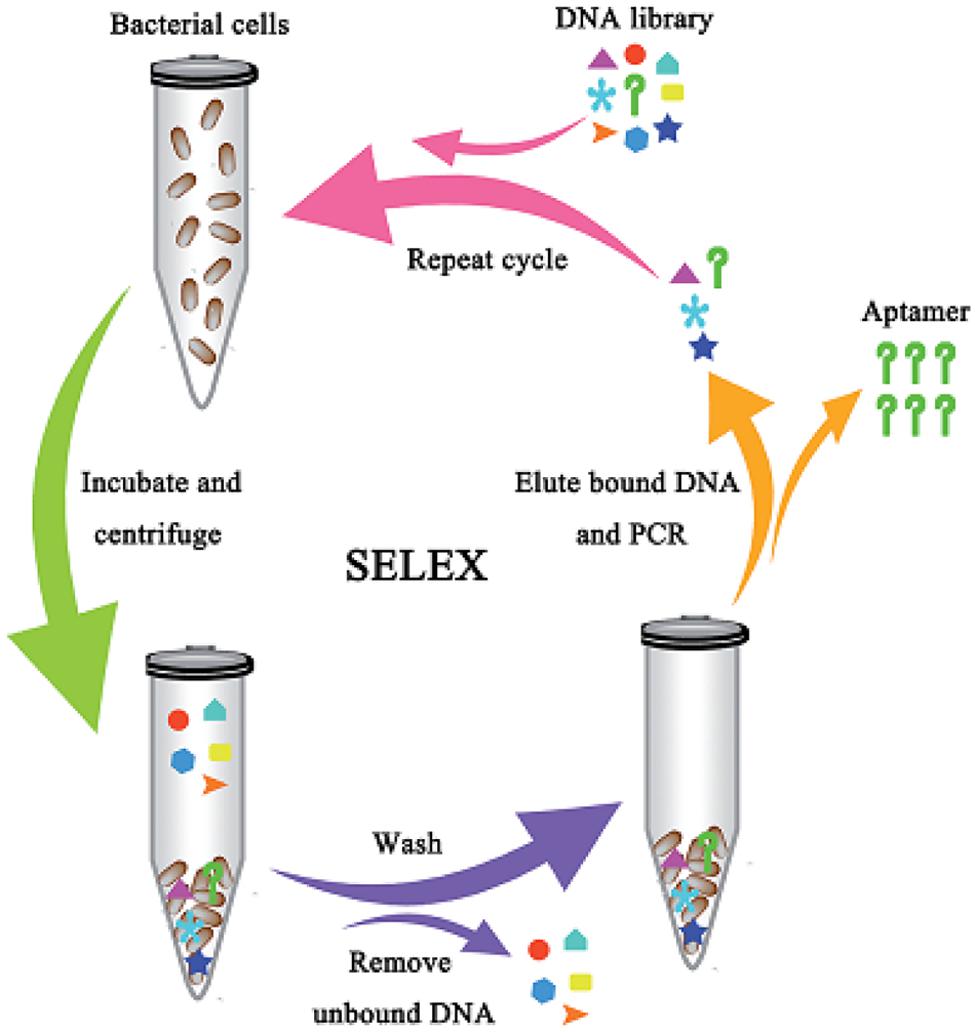

Aptamers is evolved via an iterative process of SELEX (Hamula et al., 2006). The methodology consists screening large random oligonucleotide libraries through iterative cycles of in vitro selection and enzymatic amplification (Ellington and Szostak, 1990; Tuerk and Gold, 1990). Briefly, the selection consists of numerous cycles, and each cycle includes three steps: (i) an in vitro synthesized DNA or RNA library is incubated with the target; (ii) the target-bound and unbound nucleic-acid sequences are separated and the sequences that are not bound to the target are removed; and (iii) the target-bound sequences are used as the template for the subsequent PCR amplification. The selected sequences are used as the inputs in the next round of selection; and such selection cycle will continue until the desired sequence purity is achieved. In general, a random oligonucleotide library contains 40–100 single-stranded nucleotide sequences with a randomized stretch of nucleotide in the center and fixed sequences on each end. As many as 20 rounds of selection are carried out until a pool of aptamer sequences with high target affinity is obtained. These aptamers can then be cloned and sequenced (Hamula et al., 2006). After SELEX technology was established, a variety of aptamer-based methodologies have been developed for pathogen detection and biomolecular screening.

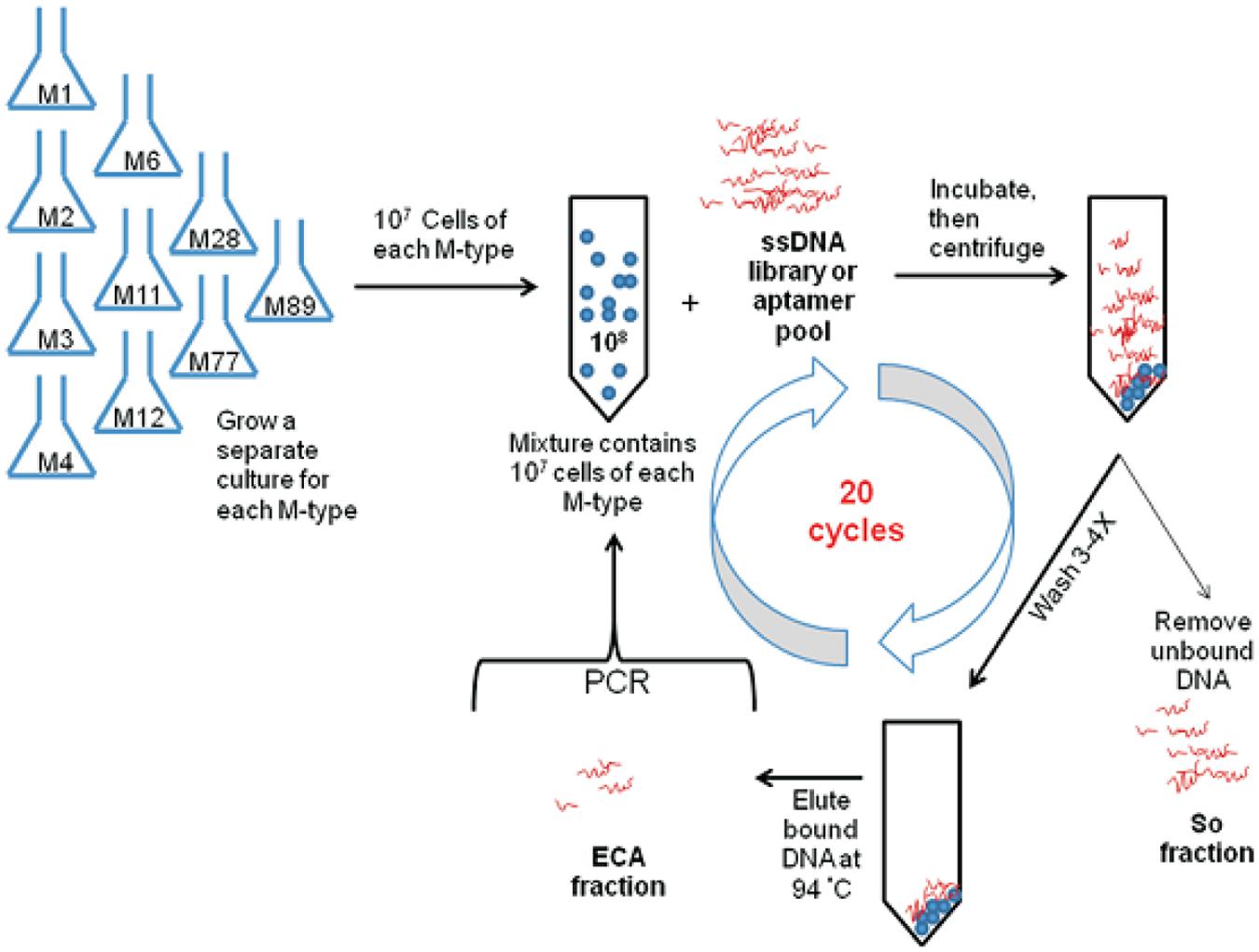

Most of the aptamers selected against pathogenic bacteria have been evolved using the conventional SELEX procedures as demonstrated in Figure 1 (Zhang et al., 2015). Zhang et al. (2015) described the selection of DNA aptamers targeted E. coli. Two high-affinity aptamers to E. coli was obtained with totally eight rounds of SELEX selections. Furthermore, these conventional SELEX procedures have been used in the detection of various pathogens such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Hamula et al., 2011), Salmonella typhimurium (Duan et al., 2012), Listeria monocytogenes (Duan et al., 2013). These aptamers to a single bacterial species can be created within 10 rounds of selection, while those to multiple bacterial species also can be achieved within 20 rounds of selection as shown by the aptamer selection scheme in Figure 2 (Liu G.Q. et al., 2014). As a result, Liu G.Q. et al. (2014) achieved selection of aptamers against various M-types of S. pyogenes by using these SELEX procedures rather than the conventional aptamer selection procedures, which use purified molecules of monoclonal cells as targets. It turned out that the aptamers selected through these procedures demonstrated high affinity and specificity to the targets (Liu G.Q. et al., 2014).

FIGURE 1. Schematic showing the aptamer selection against live bacterial cells using whole-cell SELEX (Zhang et al., 2015).

FIGURE 2. Schematic of bacterial cell SELEX against a mixture of the 10 most prevalent GAS M-types in Canada (Liu G.Q. et al., 2014).

Other Types of Selexs

Whole-Cell SELEX

In addition to the conventional SELEX method, several novel SELEX methods have been developed. For example, a series of studies aimed to shorten the selection rounds in the aptamer manufacturing process. As a result, various methodologies with single round aptamer selection procedure have been developed, e.g., the ASExp (Aptamer Selection Express) method, which uses the magnetic mechanism for separation with microbeads (Fan et al., 2008).

A method called artificially expanded genetic information systems-SELEX (AEGIS-SELEX) was introduced in 2014 (Sefah et al., 2014). As the name suggests, this method uses artificially expanded genetic information systems for aptamer selection. An AEGIS-SELEX is started with a GACTZP DNA library, consisting of randomized sequences, primer sites and two modified nucleotides (ZP); and then a standard protocol for whole-cell SELEX is followed for the selection cycle. After the 12th selection round, the aptamers are sequenced and the aptamers’ affinity is evaluated. As a result, the AEGIS-SELEX method empowered the system with higher binding variations. The sequential aptamers can reach the nanomolar range and are expected to achieve higher sequence diversities nearer to that displayed by proteins (Sefah et al., 2014).

Genomic SELEX

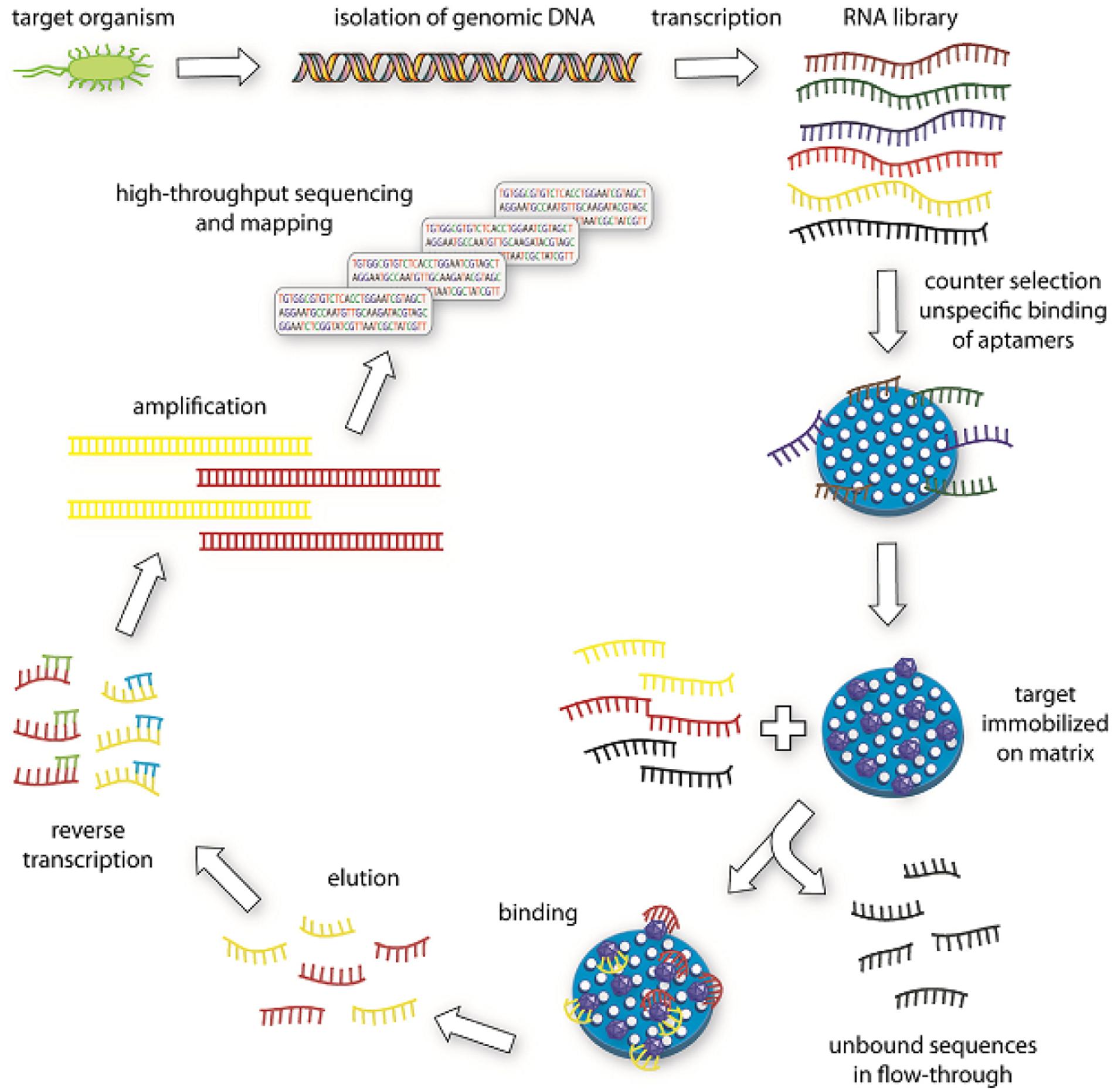

Apart from whole-cell SELEX, SELEX can be generated in the nucleic acid level as well. Lorenz et al. (2006) introduced genomic SELEX. A genomic DNA library is used in genomic SELEX in contrast to a conventional SELEX, in which a chemically synthesized library is used (Lorenz et al., 2006, 2010). A final pool of oligonucleotides obtained from the ninth selection round is characterized by high throughput sequencing (HTS) as shown in Figure 3 (Lorenz et al., 2010). A distinctive advantage of genomic SELEX is the dramatic decrease of the diversity of the initial library. Genomic DNA is isolated from the target organism and the initial library is prepared by adding specific primers to the isolated DNA and followed by Klenow-fragment extension on the new strand. This initial library is transcribed into RNA, and then continued for the selection process. First, a counter selection against immobilization matrix step is performed. The library sequences are incubated with the target and the bound oligonucleotides are subjected to reverse transcription into cDNA and used in the next round of selection. After several more rounds, the enriched sequences are subjected to HTS and mapping analyses as shown in Figure 3 (Lorenz et al., 2010).

FIGURE 3. Illustration of genomic SELEX (Lorenz et al., 2010). Genomic DNA is isolated from the target organism.

Additionally, a method called transcriptomic SELEX, which is similar to genomic SELEX, has been developed (Fujimoto et al., 2012), whereas genomic SELEX opened up a new horizon for the determination of functionally active motifs in genomic DNA. One disadvantage of this method was the non-specific binding in the assay, i.e., primer binding regions in a DNA library could easily anneal with some random fragments in the genomic library. Afterward, Jin-Der and Gray (2004), developed primer-free genomic SELEX to remedy the drawbacks associated with the transcriptomic SELEX.

Applications in Pathogen Detection and Biomolecular Screening

Currently, aptamer-based detection methods can be used in public health and food safety are limited. A primary reason for that might be the complexity of the methods since these methods involve a variety of techniques in the sample preparation and detection processes such as sample’s extraction, purification, enrichment, and separation (Pitcher and Fry, 2000; Stevens and Jaykus, 2004).

Pathogen detection is important for public health and food safety. Three areas of application account for over two thirds of all research in the field of pathogen detection (Lazcka et al., 2007), including the food industry (Patel, 2002; Leonard et al., 2003), water and environment quality control (Emde et al., 1992; Theron et al., 2000), and clinical diagnosis (Atlas, 1999). The remaining efforts go into fundamental studies (Herpers et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2004), method performance studies (Dominguez et al., 1997; Taylor et al., 2005), and development of new applied methods (Ko and Grant, 2003; Yoon et al., 2003).

Aptamers and antibodies are commonly used reagents in various detection assays; the affinity of aptamers to their targets is comparable to, or even higher than most of the monoclonal antibodies to their targets; typical dissociation constants of aptamer-target complexes are found to be in the picomolar to low micromolar ranges (Hamula et al., 2006). Therefore, nucleic-acid aptamers demonstrate numerous advantages as recognition elements in biosensing over the traditional antibodies. Moreover, aptamers are small in size, chemically stable and cost effective. More importantly, aptamers provide remarkable flexibility and convenience in engineering their structures, which have led to the development of novel biosensors that exhibited high sensitivity and specificity (Song et al., 2008). In addition to these above-mentioned advantages, aptamers offer some distinctive characteristics as a biological reagent, i.e., once selected, it can be synthesized with high reproducibility and purity from commercial sources. Furthermore, in contrast to protein-based antibodies or enzymes, aptamers (made of DNA) usually are chemically stable and often undergo significant conformational changes upon target binding (Song et al., 2008; Binnin et al., 2011). Nucleic acid aptamers are widely used in the field of biosensors. Therefore, numerous aptamer-based biosensors are developed to detect bacterial pathogens. Hence, in this review, we also summarize the most commonly used aptamer-based biosensors and bioassay methods for detection of bacterial pathogens.

Optical Biosensors

Optical biosensors are probably the most popular in bioanalysis, due to their selectivity and sensitivity. Optical biosensors have been developed for rapid detection of contaminants (Willardson et al., 1998; Tschmelak et al., 2004), toxins, drugs (Bae et al., 2004), and bacterial pathogens (Baeumner et al., 2003).

Label-Free Detection of Bacteria

Several techniques have been described that allow direct, label-free monitoring of cells at solid-liquid interfaces (Ebato et al., 1994; Morgan et al., 1996; Piehler et al., 1996; Medina et al., 1997; Ghindilis et al., 1998; Fratamico et al., 1998). These techniques are based on direct measurement of a physical phenomenon occurring during the biochemical reactions on a transducer surface (Ivnitski et al., 1999); changes in pH, oxygen consumption, potential difference, current, resistance, ion concentrations, and optical properties can be used as measures of signal parameters in certain detection systems.

Fluorescence Detection

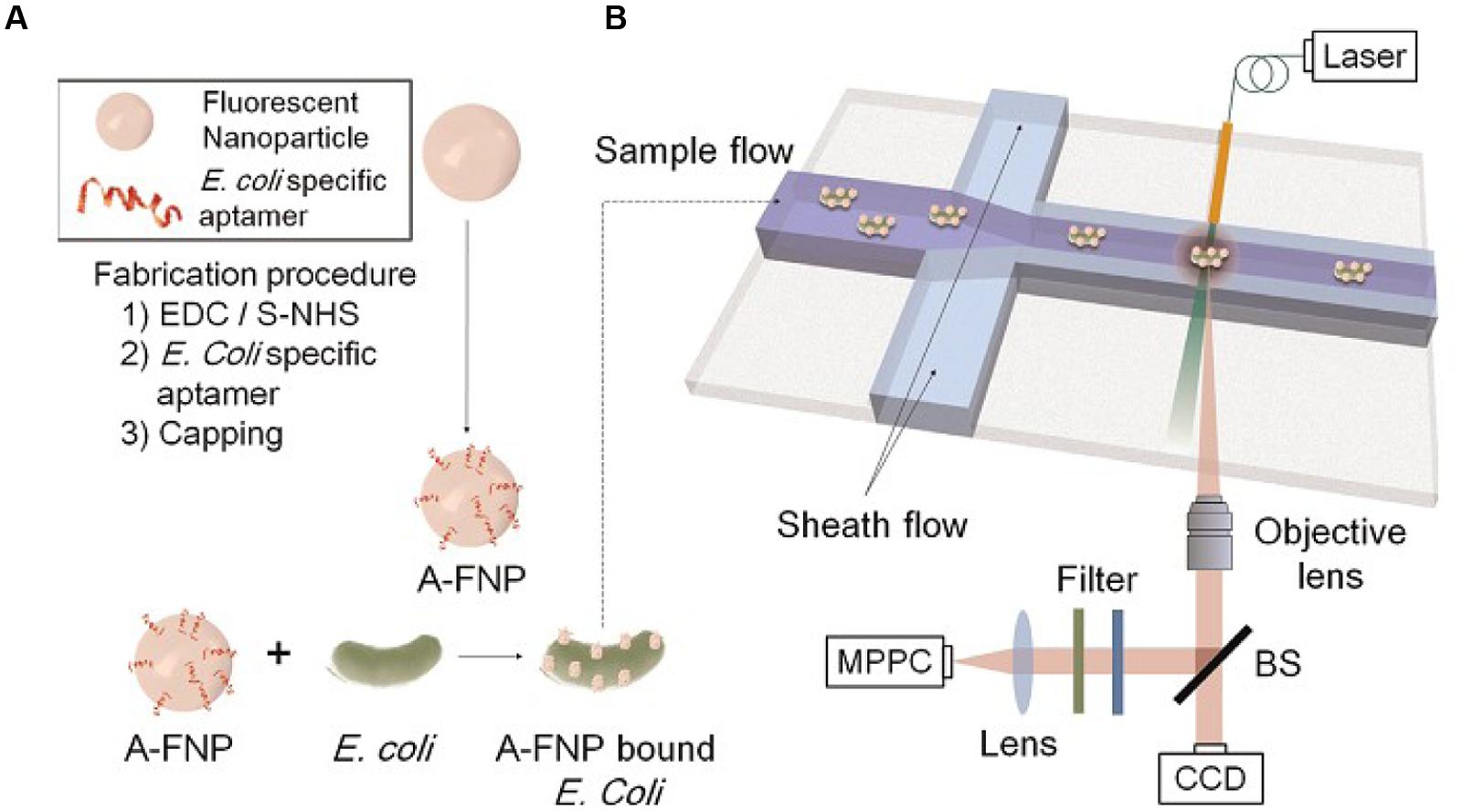

Fluorescence occurs when a valence electron is excited from its ground state to an excited singlet state. The excitation is produced by the absorption of light of sufficient energy. When the electron returns to its original ground state it emits a photon at lower energy (Chung et al., 2014). Nowadays, the fluorescent material is also broadly used (Vigneshvar et al., 2015). Bacteria can be detected by using fluorescent beads as shown in Figure 4 (Chung et al., 2014). Fratamico et al. (1998) developed a real-time, continuous, and non-destructive single cell detection method that uses target specific aptamer-conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles (A-FNPs) and an optofluidic particle-sensor platform to detect bacterial pathogens.

FIGURE 4. Schematics of the present microbe detection system. (A) Preparation of aptamer conjugated fluorescence nanoparticles (A-FNPs). (B) Detection of A-FNP-bound E. coli by the microchannel and optical particle counter.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Detections

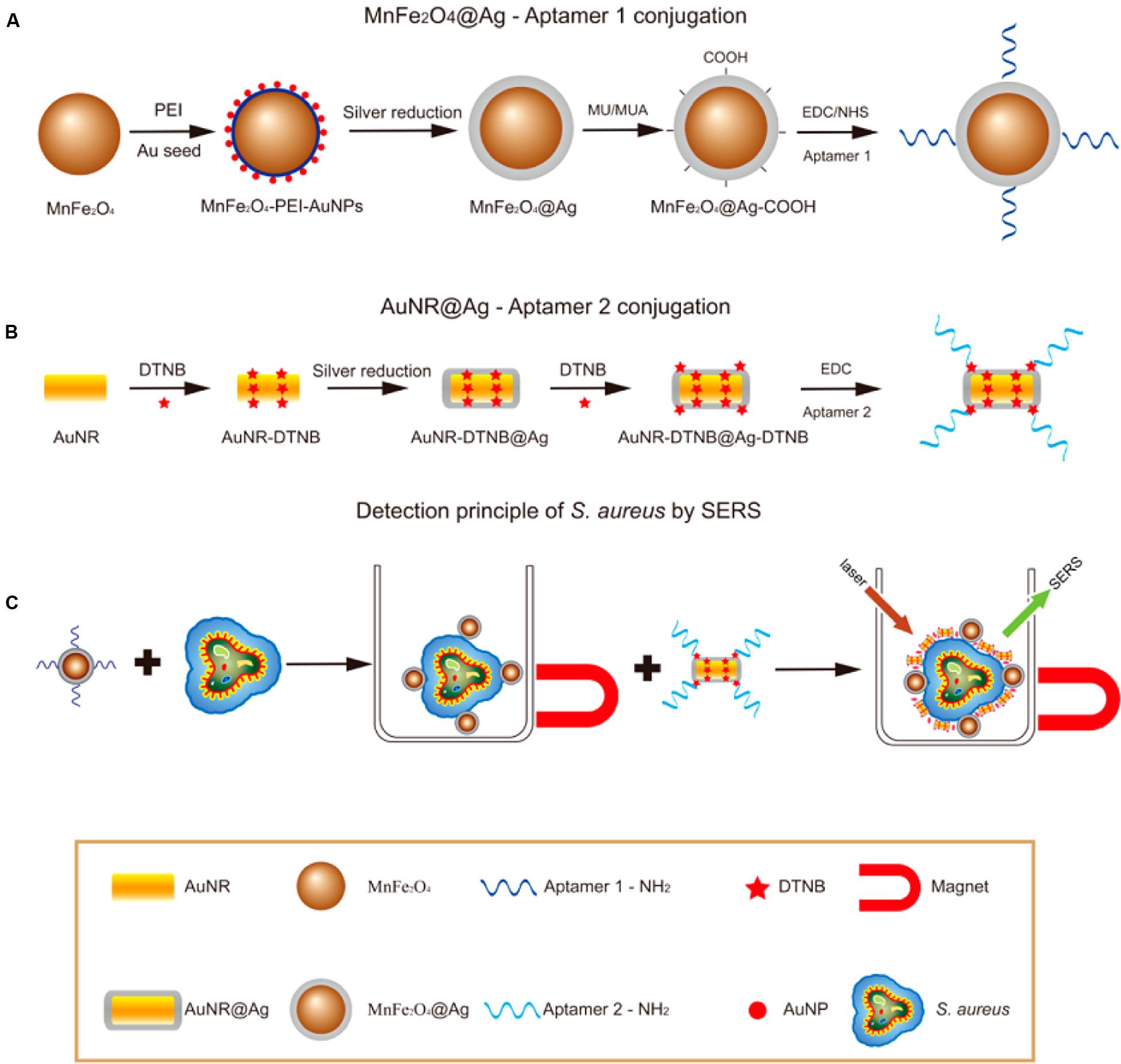

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors (Cooper, 2003) measure changes in refractive index caused by structural alterations in the vicinity of a thin film metal surface. Given its high sensitivity and fingerprinting capability, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) has been applied in various fields (Nie and Emory, 1999; Cao et al., 2002; Li et al., 2010). The detection and identification of pathogenic microorganisms by SERS have recently drowned attention because of the potential application of this technology in single-cell detection (Chang et al., 2013). The flow chart in Figure 5 demonstrates the process of S. aureus detection by using SERS (Wang et al., 2015). A plan f or the conjunction of aptamers to Ag-MNPs is shown in Figure 5A; a novel SERS tag (DioPNPs) was designed as shown in Figure 5B; and the operating principle of the SERS biosensor for bacterial detection that is based on aptamer recognition is shown in Figure 5C.

FIGURE 5. Flowchart of S. aureus detection using SERS (Wang et al., 2015). (A) Synthesis of monodispersed silver-coated magnetic nanoparticles and their conjugation with aptamer 1. (B) Synthesis of core-shell plasmonic nanoparticles (AuNR-DTNB@Ag-DTNB) and their conjugation with aptamer 2. (C) Schematic illustration of the operating principle for S. aureus detection.

Electrochemical Biosensors

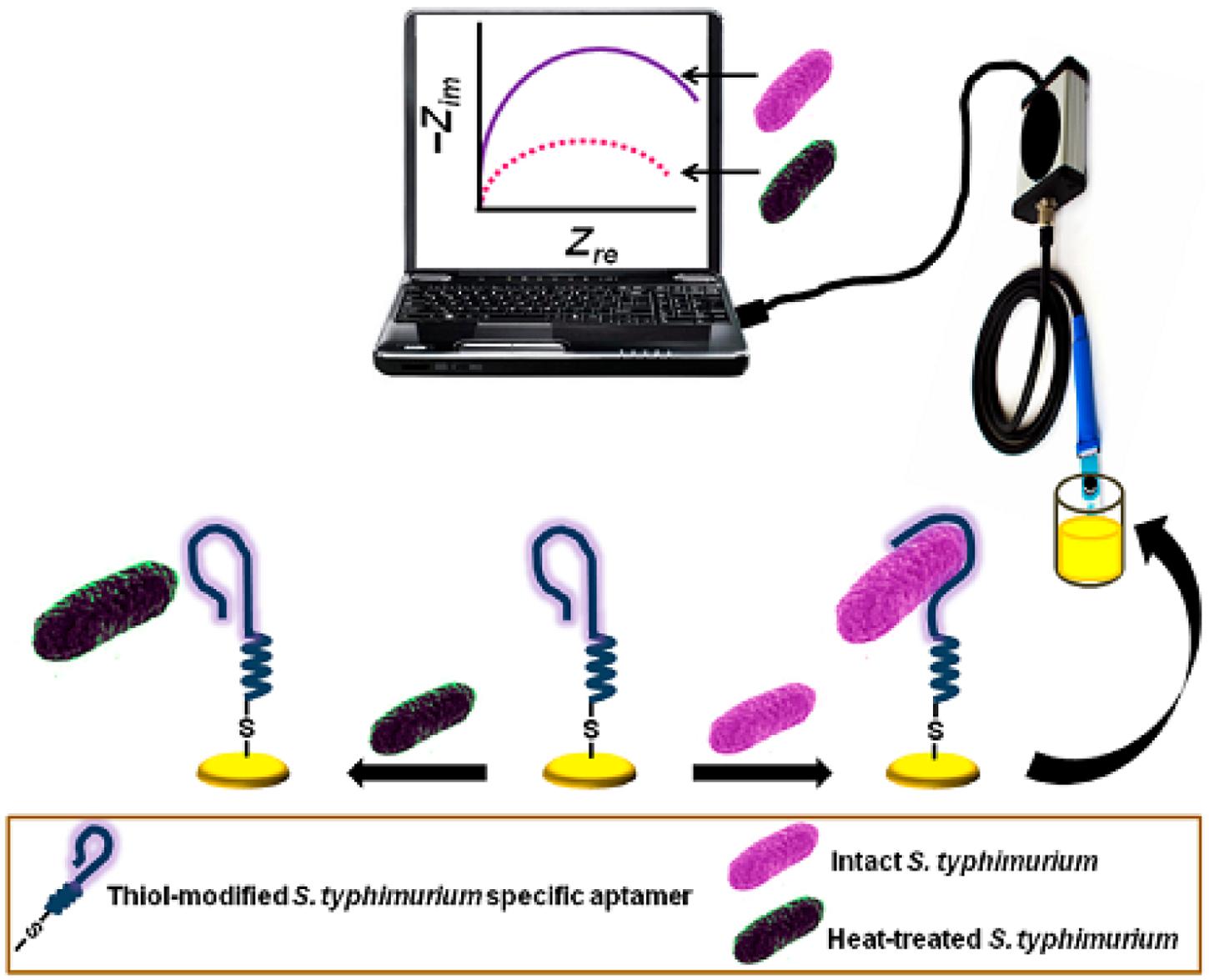

Electrochemical sensors have several advantages over optical-based systems in that they can operate in turbid media, offer comparable instrumental sensitivity, and are more amenable to miniaturization. Modern electroanalytical techniques can reach an extremely low limit of detection (up to 10-9 M), which can be achieved by using small volumes (1–20 mL) of samples (Mahmoud et al., 2012). A typical electrochemical method, which is illustrated in Figure 6 (Jenkins et al., 1988), provides a brand new avenue for the aptamer-based viability detection of various microorganisms, particularly viable but non-cultural (VBNC) bacteria, using a rapid, economic, and label-free electrochemical platform as Jenkins et al. (1988) reported.

FIGURE 6. Schematic diagram of the aptamer-mediated electrochemical detection of live Salmonella Typhimurium bacteria (Jenkins et al., 1988).

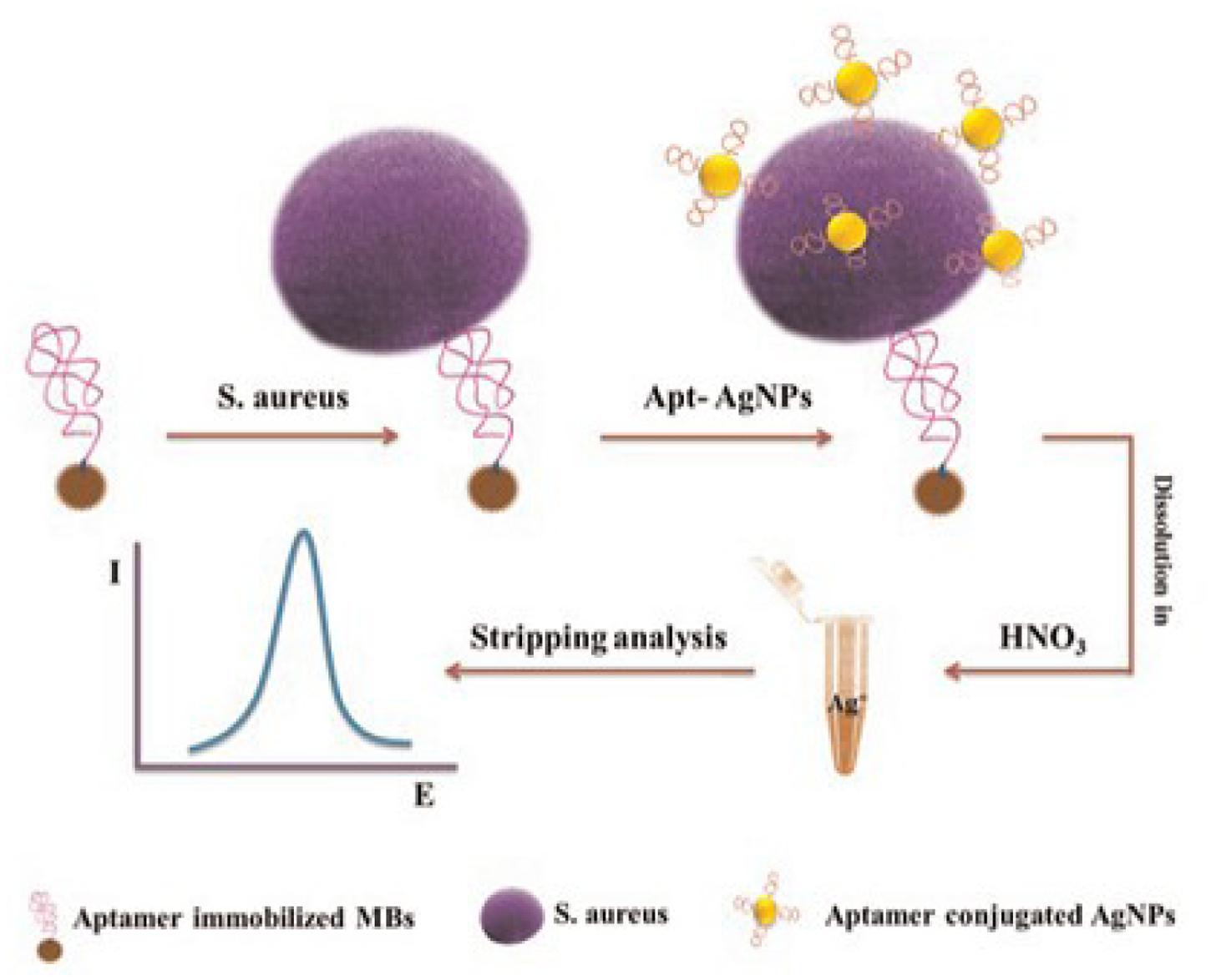

Recently, a newly developed aptamer-based biosensor system has been developed to detect pathogen (Abbaspour et al., 2015). This system uses a sensitive and highly selective dual-aptamer-based sandwich immunosensor in conjunction with electrochemical means for the detection of S. aureus as shown by Figure 7 (Abbaspour et al., 2015). As a result, excellent discriminatory power of the biosensor was achieved by utilizing the two specific aptamer sequences against the target bacteria and the magnetic beads to capture S. aureus in a liquid phase. The electrochemical detection method demonstrated a few advantages in term of simplicity, turn-around time, low cost, and limit of detection compared to the conventional detection methods. The superior sensitivity of this method provides the possibility to use aptamers to detect extremely low number (in single digital) of pathogenic bacteria in foods, which is hardly achievable by the conventional methods. Also, researchers have tried to use biotinylated single-stranded (ss) DNA aptamers with L. monocytogenes binding specificity to capture the bacteria, and subsequently detected the organism in qPCR assay. Biotinylated ssDNA aptamers are promising ligands that can be used for concentrating foodborne pathogens prior to using the conventional molecular approaches for detection (Suh and Jaykus, 2013).

FIGURE 7. Schematic representation of dual-aptamer-based electrochemical sandwich immunosensor for the detection of S. aureus (Abbaspour et al., 2015).

Lateral Chromatography Test Strips

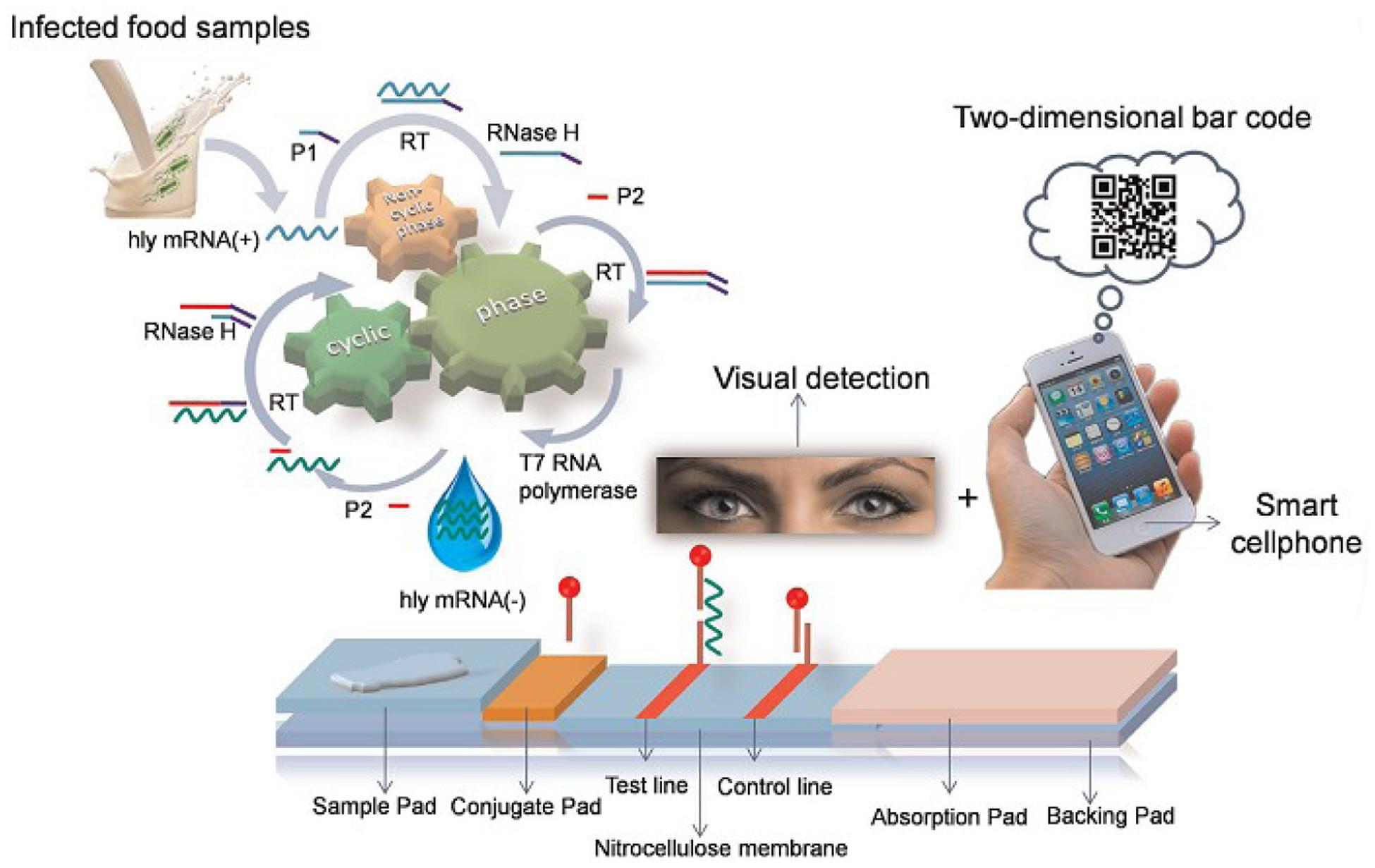

Lateral chromatography test strips, whose mechanism is illustrated in Figure 8, are also widely used. For example, Liu H.X. et al. (2014) demonstrated a simple and sensitive method for visual detection of viable pathogenic bacteria based on an isothermal RNA amplification reaction-based bioactive paper-based platform by using a two-dimensional barcode as the receiving/transmitting media for rapid detection.

FIGURE 8. Schematic illustration of isothermal RNA amplification and the configuration of the bioactive paper-based platform (Chung et al., 2014).

Numerous assays based on the specific binding of an antibody to an antigen, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Zunabovic et al., 2011; Hsu et al., 2014) and immunochromatographic lateral flow test strips (Ge et al., 2012; Nash et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2012; Cho and Irudayaraj, 2013), have been developed. However, rapid immune tests, which are widely used in low resource settings, are not suitable for fast foodborne pathogen detection due to their low sensitivity. Finally, a low-cost platform was constructed for viable pathogen detection with the naked eyes (Liu H.X. et al., 2014). In that system, specifically amplified products were applied to a paper-based platform to perform sandwich hybridization and followed by a visual exam. This method is suitable for point-of-care applications to detect foodborne pathogens (Liu H.X. et al., 2014).

Conclusions and Perspectives

In this review, we summarize the most commonly used SELEX methods in selection of aptamers against bacterial foodborne pathogens and the application of aptamer-based biosensors in biomolecular screening. Although SELEX advanced rather slowly initially, the selection of aptamers against pathogenic bacteria has been stably progressing in the last decade and nowadays, this technology has been evolved into a useful tool in pathogen detection and biomolecular screening. Initially, conventional steps and PCR were used in the SELEX procedures in the early years and then, several novel approaches and new biological materials were adapted in the SELEX procedures. On the other hand, targeting bacterial cells for detection purpose by SELEX also encounters some drawbacks, because bacteria’s highly variable and complex structures may influence the performance of aptamers. Therefore, it is necessary to continue to develop simpler and more efficient SELEX methods (requiring fewer rounds in selection) to generate specific and/or universal aptamers against various bacterial pathogens.

Compared to traditional antibody generation process, SELEX can efficiently generate specific nucleic acid probes against various analytes in a relatively short period of time. More importantly, the extraordinary properties of the selected aptamers, such as easy scale-synthesis, easy modification and long-term stability, make aptamers ideal alternatives to the traditional antibodies. However, improvement in aptamer selection efficiency by SELEX is needed in the future work. Also, other platforms, including magnetic separation techniques, array or microfluidic chips, can be integrated with initial SELEX to further widen the applications of this promising technology. For example, at present, biosensor-based detection technologies can merely meet the basic requirements for testing in the laboratory and clinic. Obviously, it can be expected that simpler, faster, more efficient, and more economic aptamer-based methods will be developed for pathogen detection and biomolecular screening in the future.

Author Contributions

JT, FY, LZ, YY, LY, FX, and BL wrote the manuscript. WC and BL revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the NSFC grant of 21475030, 31301460, the S&T Research Project of Anhui Province 15czz03109, the National 10000 Talents-Youth Top-notch Talent Program, the National and Zhejiang Public Benefit Research Project (201313010, 2014C32051).

References

Abbaspour, A., Norouz-Sarvestani, F., Noori, A., and Soltani, N. (2015). Aptamer-conjugated silver nanoparticles for electrochemical dual-aptamer-based sandwich detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 68, 149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.12.040

Atlas, R. M. (1999). Legionella: from environmental habitats to disease pathology, detection and control. Environ. Microbiol. 1, 283–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00046.x

Bae, Y. M., Oh, B. K., Lee, W. W., and Choi, J. (2004). Detection of insulin-antibody binding on a solid surface using imaging ellipsometry. Biosens. Bioelectron. 20, 895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.032

Baeumner, A. J., Cohen, R. N., Miksic, V., and Min, J. (2003). RNA biosensor for the rapid detection of viable Escherichia coli in drinking water. Biosens. Bioelectron. 18, 405–413. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(02)00162-8

Binnin, J. M., Leung, D. W., and Amarasinghe, G. K. (2011). Aptamers in virology: recent advances and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 3:29. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00029

Bock, L. C., Griffin, L. C., Latham, J. A., Vermaas, E. H., and Toole, J. J. (1992). Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature 355, 564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0

Boiziau, C., Dausse, E., Yurchenko, L., and Toulmé, J. J. (1999). DNA aptamers selected against the HIV-1 trans-activation-responsive RNA element form RNA-DNA kissing complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12730–12737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12730

Cao, Y. W. C., Rongchao, J., and Mirkin, C. A. (2002). Nanoparticles with Raman spectroscopic fingerprints for DNA and RNA detection. Science 297, 1536–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5586.1536

Chang, Y. C., Yang, C. Y., Sun, R. L., Cheng, Y. F., Kao, W. C., and Yang, P. C. (2013). Rapid single cell detection of Staphylococcus aureus by aptamer-conjugated gold nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 3:1863. doi: 10.1038/srep01863

Cho, I. H., and Irudayaraj, J. (2013). Lateral-flow enzyme immunoconcentration for rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 3313–3319. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6742-3

Chung, J. Y., Kang, J. S., Jurng, J. S., Jung, J. H., and Kim, B. C. (2014). Fast and continuous microorganism detection using aptamer-conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles on an optofluidicplatform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 67, 303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.08.039

Cooper, M. A. (2003). Label-free screening of bio-molecular interactions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 377, 834–842. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2111-y

Dominguez, J. A., Matas, L., Manterola, J. M., Blavia, R., Sopena, N., Belda, F. J., et al. (1997). Comparison of radioimmunoassay and enzyme immunoassay kits for detection of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen in both concentrated and nonconcentrated urine samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 1627–1629.

Duan, N., Wu, S., Chen, X., Huang, Y., and Whang, Z. (2012). Selection and identification of a DNA aptamer targeted to Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 4034–4038. doi: 10.1021/jf300395z

Duan, N., Wu, S. J., Chen, X. J., Huang, Y. K., Xia, Y., Ma, X. Y., et al. (2013). Selection and characterization of aptamers against Salmonella Typhimurium using whole-bacterium systemic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX). J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 3229–3234. doi: 10.1021/jf400767d

Ebato, H., Gentry, C. A., Herron, J. N., Müller, W., Okahata, Y., Ringsdorf, H., et al. (1994). Investigation of specific binding of antifluorescyl antibody and Fab to fluorescein lipids in Langmuir-Blodgett deposited films using quartz crystal microbalance methodology. Anal. Chem. 66, 1683–1689. doi: 10.1021/ac00082a014

Ellington, A. D., and Szostak, J. W. (1990). In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0

Emde, K. M. E., Mao, H., and Finch, G. R. (1992). Detection and occurrence of waterborne bacterial and viral pathogens. Water Environ. Res. 64, 641–647.

Fan, M., Mcburnett, S. R., Andrews, C. J., Allman, A. M., Bruno, J. G., and Kiel, J. L. (2008). Aptamer selection express: a novel method for rapid single-step selection and sensing of aptamers. J. Biomol. Tech. 19, 311–331.

Fratamico, P. M., Strobaugh, T. P., Medina, M. B., and Gehring, A. G. (1998). Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Biotechnol Tech. 12, 571–576. doi: 10.1023/A:1008872002336

Fujimoto, Y., Nakamura, Y., and Ohuchi, S. (2012). HEXIM1-binding elements on mRNAs identified through transcriptomic SELEX and computational screening. Biochimie 94, 1900–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.05.003

Gao, L. Y., Guo, S., Mclaughlin, B., Morisaki, H., Engel, J. N., and Brown, E. J. (2004). A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1677–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x

Ge, L., Yan, J. X., Song, X. R., Yan, M., Ge, S. G., and Yu, J. H. (2012). Three-dimensional paper-based electrochemiluminescence immunodevice for multiplexed measurement of biomarkers and point-of-care testing. Biomaterials 33, 1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.065

Ghindilis, A. L., Atanasov, P., Wilkins, M., and Wilkins, E. (1998). Immunosensors: electrochemical sensing and other engineering approaches. Biosens. Bioelectron. 13, 113–131. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(97)00031-6

Hamula, C. L., Chris, L. X., and Xing-Fang, L. (2011). DNA Aptamers binding to multiple prevalent M-types of Streptococcus pyogenes. Anal. Chem. 83, 3640–3647. doi: 10.1021/ac200575e

Hamula, C. L., Guthrie, J. W., Zhang, H., Li, X. F., and Le, X. C. (2006). Selection and analytical applications of aptamers. TrAC Trends Analyt. Chem. 25, 681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2006.05.007

Herpers, B. L., Jongh, B. M. D., van der Zwaluw, K., and Hannen, E. J. V. (2003). Real-time PCR assay targets the 23S-5S spacer for direct detection and differentiation of Legionella spp. and Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 4815–4816. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4815-4816.2003

Hsu, M. Y., Yang, C. Y., Hsu, W. H., Lin, K. H., Wang, C. Y., Shen, Y. C., et al. (2014). Monitoring the VEGF level in aqueous humor of patients with ophthalmologically relevant diseases via ultrahigh sensitive paper-based ELISA. Biomaterials 35, 3729–3735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.030

Ivnitski, D., Atanasov, P. E., and Abdel-Hamid, I. (1999). Biosensors for detection of pathogenic bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 14, 599–624. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(99)00039-1

Jayasena, S. D. (1999). Aptamers: an emerging class of molecules that rival antibodies in diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 45, 1628–1650.

Jenkins, S. H., Heineman, W. R., and Halsall, H. B. (1988). Extending the detection limit of solid-phase electrochemical enzyme immunoassay to the attomole level. Anal. Biochem. 168, 292–299. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90321-1

Jin-Der, W., and Gray, D. M. (2004). Selection of genomic sequences that bind tightly to Ff gene 5 protein: primer-free genomic SELEX. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e182. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh179

Ko, S., and Grant, S. A. (2003). Development of a novel FRET method for detection of Listeria or Salmonella. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 96, 372–378. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(03)00572-0

Law, J. W.-F., Mutalib, N.-S. A., Chan, K.-G., and Lee, L.-H. (2015). Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: principles, applications, advantages and limitations. A review. Front. Microbiol. 5:770. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00770

Lazcka, O., Campo, F. J. D., and Muñoz, F. X. (2007). Pathogen detection: a perspective of traditional methods and biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 22, 1205–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.06.036

Leonard, P., Hearty, S., Brennan, J., Dunne, L., Quinn, J., Chakraborty, T., et al. (2003). Advances in biosensors for detection of pathogens in food and water. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 32, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00232-6

Li, J. F., Huang, Y. F., Ding, Y., Yang, Z. L., Li, S. B., Zhou, X. S., et al. (2010). Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature 464, 392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08907

Liu, G. Q., Lian, Y. Q., Gao, C., Yu, X. F., Zhu, M., Zong, K., et al. (2014). In vitro Selection of DNA aptamers and fluorescence-based recognition for rapid detection Listeria monocytogenes. J. Integr. Agric. 13, 1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60766-8

Liu, H. X., Zhan, F. F., Liu, F., Zhu, M. J., Zhou, X. M., and Xing, D. (2014). Visual and sensitive detection of viable pathogenic bacteria by sensing of RNA markers in gold nanoparticles based paper platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 62, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.06.020

Lorenz, C., Gesell, T., Zimmermann, B., Schoeberl, U., Bilusic, I., Rajkowitsch, L., et al. (2010). Genomic SELEX for Hfq-binding RNAs identifies genomic aptamers predominantly in antisense transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3794–3808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq032

Lorenz, C., Pelchrzim, F. V., and Schroeder, R. (2006). Genomic systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (Genomic SELEX) for the identification of protein-binding RNAs independent of their expression levels. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2204–2212. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.372

Mahmoud, L., Zamay, A. S., Kolovskaya, O. S., Reshetneva, I. T., Zamay, G. S., Kibbee, R. J., et al. (2012). Aptamer-based viability impedimetric sensor for bacteria. Anal. Chem. 84, 8966–8969. doi: 10.1021/ac302902s

Medina, M. B., Houten, L. V., Cooke, P. H., and Tu, S. (1997). Real-time analysis of antibody binding interactions with immobilized E. coli O157:H7 cells using the BIAcore. Biotechnol. Tech. 11, 173–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1018453530459

Morgan, C. L., Newman, D. J., and Price, C. P. (1996). Immunosensors: technology and opportunities in laboratory medicine. Clin. Chem. 42, 193–209.

Nash, M. A., Waitumbi, J. N., Hoffman, A. S., Paul, Y., and Stayton, P. S. (2012). Multiplexed enrichment and detection of malarial biomarkers using a stimuli-responsive iron oxide and gold nanoparticle reagent system. ACS Nano 6, 6776–6785. doi: 10.1021/nn3015008

Nie, S., and Emory, S. R. (1999). Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science 275, 1102–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102

Patel, P. D. (2002). (Bio) sensors for measurement of analytes implicated in food safety: a review. TrAC Trends Analyt. Chem. 21, 96–115. doi: 10.1016/S0165-9936(01)00136-4

Piehler, J., Brecht, A., Geckeler, K. E., and Gauglitz, G. (1996). Surface modification for direct immunoprobes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 11, 579–590. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(96)83293-3

Pitcher, D. G., and Fry, N. K. (2000). Molecular techniques for the detection and identification of new bacterial pathogens. J. Infect. 40, 116–120. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0635

Salis, H., Tamsir, A., and Voigt, C. (2009). Engineering bacterial signals and sensors. Contrib. Microbiol. 16, 1–32.

Sefah, K., Yang, Z. Y., Bradley, K. M., Hoshika, S., Jiméneza, E., Zhang, L. Q., et al. (2014). In vitro selection with artificial expanded genetic information systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 1449–1454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311778111

Song, S., Wang, L., Li, J., Fan, C., and Zhao, J. (2008). Aptamer-based biosensors. Trends Analyt. Chem. 27, 108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2007.12.004

Stevens, K. A., and Jaykus, L. A. (2004). Bacterial separation and concentration from complex sample matrices: a review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 7–24. doi: 10.1080/10408410490266410

Suh, S. H., and Jaykus, L. A. (2013). Nucleic acid aptamers for capture and detection of Listeria spp. J. Biotechnol. 167, 454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.027

Taylor, A. D., Yu, Q., Chen, S., Homola, J., and Jiang, S. (2005). Comparison of E. coli O157: H7 preparation methods used for detection with surface plasmon resonance sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 107, 202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2004.11.097

Theron, J., Cilliers, J., Du, P. M., Brözel, V. S., and Venter, S. N. (2000). Detection of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae from environmental water samples by an enrichment broth cultivation-pit-stop semi-nested PCR procedure. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89, 539–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01140.x

Tok, J., and Cho, J. R. (2000). RNA aptamers that specifically bind to a 16S ribosomal RNA decoding region construct. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2902–2910. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.15.2902

Tombelli, S., Minunni, M., and Mascini, M. (2005). Piezoelectric biosensors: strategies for coupling nucleic acids to piezoelectric devices. Methods 37, 48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.05.005

Torres-Chavolla, E., and Alocilja, E. C. (2009). Aptasensors for detection of microbial and viral pathogens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 24, 3175–3182. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.11.010

Tschmelak, J., Proll, G., and Gauglitz, G. (2004). Sub-nanogram per litre detection of the emerging contaminant progesterone with a fully automated immunosensor based on evanescent field techniques. Anal. Chim. Acta 519, 143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.06.031

Tuerk, C., and Gold, L. (1990). Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121

Tuerk, C., Macdougal, S., and Gold, L. (1992). RNA pseudoknots that inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6988–6992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6988

Vigneshvar, S., Sudhakumari, C. C., Senthilkumaran, B., and Prakash, H. (2015). Recent advances in biosensor technology for potential applications – an overview. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 4:11. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2016.00011

Wang, J., Wu, X., Wang, C., Shao, N., Dong, P., Xiao, R., et al. (2015). Magnetically assisted surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus based on aptamer recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 20919–20929. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b06446

Willardson, B. M., Wilkins, J. F., Rand, T. A., Schupp, J. M., Hill, K. K., Keim, P., et al. (1998). Development and testing of a bacterial biosensor for toluene-based environmental contaminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 1006–1012.

Yan, J. X., Ge, L., Song, X. R., Yan, M., Ge, S. G., and Yu, J. H. (2012). Paper-based electrochemiluminescent 3D immunodevice for lab-on-paper, specific, and sensitive point-of-care testing. Chemistry 18, 4938–4945. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102855

Yoon, C. H., Cho, J. H., Oh, H. I., Kim, M. J., Lee, C. W., Choi, J. W., et al. (2003). Development of a membrane strip immunosensor utilizing ruthenium as an electro-chemiluminescent signal generator. Biosens. Bioelectron. 19, 289–296. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(03)00207-0

Zhang, C. X., Lv, X. F., Han, X., Man, Y., Yasmeen, S., Qing, H., et al. (2015). Whole-cell based aptamer selection for selective capture of microorganisms using microfluidic devices. Anal. Methods 7, 6339–6345. doi: 10.1039/C5AY01016K

Keywords: aptamers, SELEX, ligands, aptamer-based biosensors, bacterial pathogen detection, dissociation constants, biomolecular screening, high affinity

Citation: Teng J, Yuan F, Ye Y, Zheng L, Yao L, Xue F, Chen W and Li B (2016) Aptamer-Based Technologies in Foodborne Pathogen Detection. Front. Microbiol. 7:1426. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01426

Received: 08 July 2016; Accepted: 29 August 2016;

Published: 12 September 2016.

Edited by:

Andrea Gomez-Zavaglia, Center for Research and Development in Food Cryotechnology – The National Scientific and Technical Research Council, ArgentinaReviewed by:

Kiiyukia Matthews Ciira, Mount Kenya University, KenyaLearn-Han Lee, Monash University Malaysia Campus, Malaysia

Copyright © 2016 Teng, Yuan, Ye, Zheng, Yao, Xue, Chen and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Xue, ZmVuZ3h1ZTEyMTlAYWxpeXVuLmNvbQ== Wei Chen, Y2hlbndlaXNobnVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Jun Teng

Jun Teng Fang Yuan

Fang Yuan Yingwang Ye1

Yingwang Ye1 Li Yao

Li Yao Feng Xue

Feng Xue Wei Chen

Wei Chen Baoguang Li

Baoguang Li