95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Oncol. Rev. , 24 May 2024

Sec. Oncology Reviews: Original Research

Volume 18 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/or.2024.1355256

Ofer Rotem1*†

Ofer Rotem1*† Karyn Revital Geiger2,3†

Karyn Revital Geiger2,3† Ekaterina Hanovich1

Ekaterina Hanovich1 Mor Moskovitz1

Mor Moskovitz1 Noga Kurman1

Noga Kurman1 Daniel Reinhorn1,4

Daniel Reinhorn1,4 Idit Peretz1

Idit Peretz1 Rinat Yerushalmi1,4

Rinat Yerushalmi1,4 Salomon M. Stemmer1,4

Salomon M. Stemmer1,4As clinical trials in oncology require substantial efforts, maximizing the insights gained from them by conducting subgroup analyses is often attempted. The goal of these analyses is to identify subgroups of patients who are likely to benefit, as well as the subgroups of patients who are unlikely to benefit from the studied intervention. International guidelines occasionally include or exclude novel medications and technologies for specific subpopulations based on such analyses of pivotal trials without requiring confirmatory trials. This Perspective discusses the importance of providing a complete dataset of clinical information when reporting subgroup analyses and explains why such transparency is key for better clinical interpretation of the results and the appropriate application to clinical care, by providing examples of transparent reporting of clinical studies and examples of incomplete reporting of clinical studies.

Clinical trials require major investment by investigators, sponsors, and participants. Therefore, maximizing the number of insights gained from each trial is often attempted. Specifically, practitioners, researchers, and regulatory agencies alike, seek to identify subgroups of patients who are likely to benefit from the studied intervention, as well as subgroups of patients who are unlikely to benefit from it [1]. Distinguishing between these subgroups is particularly important in the era of personalized medicine. International guidelines occasionally include or exclude novel medications and technologies for specific populations based on subgroup analyses of pivotal trials without confirmatory trials for the subgroup of interest.

A prominent example is the evolution of the studies and indications for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in metastatic non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), which was based on subgroup analyses. Initially, the findings supported treating all metastatic NSCLC patients with EGFR TKIs, then only the light/never smoker population, and eventually the results supported limiting the use of EGFR TKIs only to those with EGFR mutations. Consequently, the guidelines for EGFR TKIs shifted from EGFR TKI’s as third-line therapy for all patients with advanced NSCLC to first-line therapy for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations [2–9].

Conducting confirmatory trials for a specific subpopulation is costly and may take several years, while in the meantime, the subpopulation that could have benefited from the intervention is undertreated. Thus, subgroup analysis is a practical approach in the real world. However, forming guidelines and making clinical decisions based on subgroup analyses alone present several major challenges. One of the more commonly discussed challenges is statistical, since the probability of at least one type 1 error (i.e., a false result that falls within statistical significance) increases with the number of tests run on the same data, and the smaller sample size (per subgroup) makes it harder to reach statistical significance. These statistical issues, which have been discussed in many articles, and for which solutions were offered, [1, 10, 11] are beyond the scope of the current article.

This Perspective focuses on the importance of providing a complete dataset of clinical information when reporting subgroup analyses and explains why such transparency is key for interpreting the results of such analyses, and appropriately applying them to clinical care.

In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pembrolizumab as first-line monotherapy for patients with metastatic NSCLC with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)≥50% with no EGFR or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genomic tumor aberrations based on the data from the KEYNOTE-024 study. The FDA expanded the indication in 2019 to include metastatic NSCLC with PD-L1≥1% and no EGFR or anaplastic ALK genomic tumor aberrations [12]. This expansion was based on data from the KEYNOTE-042 study, which demonstrated the superiority of first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy over standard-of-care chemotherapy (platinum-based doublet) in patients with PD-L1-positive metastatic NSCLC, in the three pre-planned subgroups (PD-L1>50%, PD-L1>20%, and PD-L1>1%) [13]. However, exploratory subgroup analysis failed to show the benefit of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy alone in patients with PD-L1 1%–49%, and thus, some international guidelines and regulatory authorities including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) still recommend pembrolizumab monotherapy only for patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50% [14–16]. As the KEYNOTE-042 report provided a complete dataset of clinical information, it was possible to confirm that baseline characteristics between the two treatment groups were well-balanced, and that the published progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) Kaplan-Meier plots of the placebo groups were consistent with previously published data, thereby supporting the validity of the guideline decisions [13]. Notably, demonstrating that the groups are well balanced with respect to measured baseline characteristics, is necessary but insufficient evidence that the groups are balanced, as unknown/unmeasured confounders may still be unbalanced (as the randomization is broken).

The importance of transparent reporting for subgroup analysis-based guidelines is further illustrated by the PACIFIC trial, which demonstrated superior PFS and OS (two coprimary endpoints) for durvalumab vs. placebo in patients with stage III unresectable NSCLC following definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT) (PFS hazard ratio [HR] 0.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.42–0.65; OS HR, 0.68, 99.73% CI 0.47–0.997) [17, 18]. Based on these results, the FDA approved this drug, and the NCCN guidelines recommended durvalumab for all patients [19, 20]. In contrast, the EMA and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommended the addition of durvalumab only for patients with PD-L1≥1% based on post-hoc subgroup analysis, which demonstrated an OS HR of 1.14 (95% CI, 0.71–1.84) and PFS HR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.48–1.11) in PD-L1-negative patients [21–23]. Importantly, evaluation of PD-L1 levels was not obligatory in this trial. Determining PD-L1 levels in pre-cCRT archival tumor samples was optional and available for 63% of patients. Of these, the expression levels were retrospectively reported according to prespecified and post-hoc tumor cell cutoffs (25% and 1%, respectively). Additionally, primary endpoints were not defined or stratified by PD-L1 levels. However, similar to the reporting on the KEYNOTE-042 trial, the reports on the PACIFIC trial included all patient characteristics and PFS as well as OS Kaplan-Meier plots, thereby facilitating a clinically meaningful interpretation of the data and helping clinicians decide which guidelines to follow [23–26].

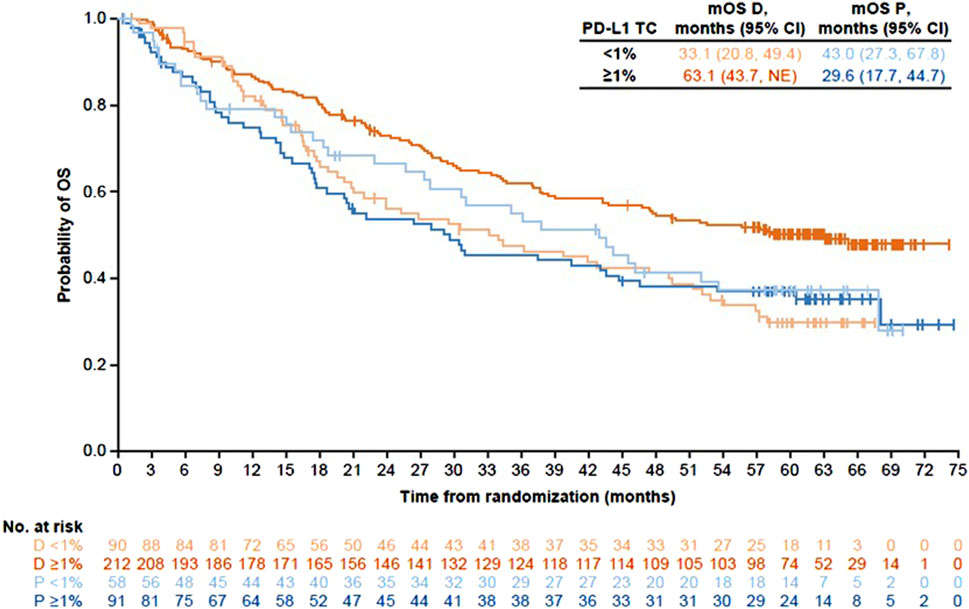

The information provided in the EMA package insert was consistent with the post-hoc subgroup analysis and showed improved clinical outcomes with increased PD-L1 levels in the durvalumab but not the placebo arm [21]. However, further scrutiny of the reported data undermines the validity of the recommendation not to treat PD-L1-negative patients. Specifically, comparing baseline characteristics of PD-L1-negative patients between the two treatment arms revealed an imbalance in favor of the placebo arm. PD-L1-negative patients in the placebo arm were more likely to be younger (<65 years), have nonsquamous histology, or have a stage IIIA disease, all of which are good prognostic factors for stage III unresectable NSCLC. Furthermore, the OS Kaplan-Meier plots of the placebo groups revealed that the PD-L1-negative population overperformed the PD-L1-positive population (and, to a greater extent, the PD-L1>25% population) (Figure 1) [23–26]. Notably, the Kaplan-Meier plots were important for this interpretation, as the information could not be extrapolated from the 4-year HR values alone.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier plots for overall survival comparing treatment with durvalumab to treatment with placebo by PD-L1 expression in the PACIFIC trial. Produced from published data [24].

The primary endpoint of the ExteNET trial was to determine whether neratinib treatment after standard adjuvant trastuzumab-containing therapy improves the 2-year invasive disease-free survival (IDFS) of patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive early breast cancer. Adding neratinib did improve the 2-year IDFS from 91.6% to 93.9%, however, a higher incidence of grade 3/4 adverse events was noted [27]. Subsequently, several international guidelines recommended neratinib for select subgroups of patients. The EMA recommended neratinib for patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors within 1 year of trastuzumab-based therapy [28]. Analysis of this population was not a formal endpoint of this study, however, this EMA guidance is supported by the publication of Chan et al [29] which provided a complete dataset of clinical information on this group of interest. The NCCN guidelines recommended considering neratinib treatment for patients with hormone receptor-positive disease with lymph node involvement who underwent upfront surgery or did not achieve pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy [30]. Analyzing these two subgroups were not defined as endpoints of the study, and the corresponding baseline patient and tumor characteristics were not included in the publications [27, 31]. Hence, it remains unclear whether within these subgroups, the treatment and placebo groups were well balanced, or whether imbalances that may have affected the results were in play.

The APHINITY trial assessed pertuzumab as an adjuvant treatment for HER2-positive early breast cancer. The primary endpoint was 3-year IDFS rate, which was 94.1% in the pertuzumab group and 93.2% in the placebo group (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66–1.00; p = 0.045). Subgroup analysis revealed that pertuzumab was more beneficial for select subgroups [32]. Consequently, the FDA, ESMO, and EMA recommended pertuzumab for high-risk patients, defined as patients with lymph node involvement or patients with hormone receptor-negative disease [33–35]. As in the ExteNET example, baseline patient and tumor characteristics for these subgroups were not reported [32].

The analysis of the APHINITY trial data emphasizes the challenges associated with interpreting statistically significant results from subgroup analyses. The original publication reported that the three subgroups benefiting the most from pertuzumab were postmenopausal patients, patients with node-positive disease, and those whose tumors were <2 cm in size. In a 2-variant analysis involving nodal status and tumor size, tumor size became a nonsignificant variable [32]. Interestingly, although nodal status was included in the guidelines as a decision-making factor for pertuzumab treatment, being postmenopausal was not, despite being a statistically significant predictor of treatment benefit (probably, because it was considered a type 1 error), further elucidating the need for careful examination of all subgroup analysis regardless of whether the findings are consistent with prior knowledge.

A more recent example of guidelines that were updated following an incomplete reporting of subgroup analyses involves treatment recommendations for young early-stage luminal breast cancer patients based on multigene expression assays. In the two phase III trials evaluating the 21-gene Recurrence Score (RS) assay in node-negative and node-positive hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer (TAILORx and RxPONDER, respectively), only younger patients (≤50 years in TAILORx, premenopausal in RxPONDER) benefited from adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy (in TAILORx, the randomized arms included RS 11–25 patients and benefit was observed in the RS 16–25 range; in RxPONDER, the randomized arms included RS 0–25 patients, and the benefit was observed for the entire evaluated range) [36, 37]. Similarly, in an exploratory subgroup analysis of the phase III MINDACT trial evaluating the 70-gene signature in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, the chemotherapy benefit also seemed to be age-dependent with a clinically relevant effect observed only in those ≤50 years [38]. Notably, the published reports on TAILORx, RxPONDER, and MINDACT did not include baseline patient and tumor characteristics for the younger patient population by treatment arm, and the balance between the treatment arms within this subpopulation was not assessed [36–38]. Nonetheless, major treatment guidelines such as those published by ASCO and NCCN did incorporate these findings into their recommendations (the ESMO guidelines included these findings but did not provide specific recommendations) [30, 39, 40].

The examples discussed in the current article illustrate the challenges associated with the interpretation of subgroup analyses. In order to address these challenges, and allow clinically meaningful interpretation that would ultimately improve patient care, we suggest that the standards for reporting results of subgroup analyses, particularly for subgroups of interest, should be the same as those for the main ITT population analysis; i.e., presenting Kaplan-Meier plots instead of just reporting the HR values, and including all patient/disease baseline characteristics for the subgroup of interest.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

OR conceived of the study and interpreted the data. OR and KG wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Following a request from the authors, AstraZeneca funded studio graphic support for the adaptation of the figure. The graphic support was provided by Ashfield MedComms (Macclesfield, United Kingdom), under the direction of the corresponding author. AstraZeneca did not initiate the development of this manuscript, nor was it involved in any way in its development.

Medical editing assistance was provided by Avital Bareket-Samish, Ph.D., and funded by Rabin Medical Center.

OR reports being a speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, and Teva, and being a consultant for Rhenium, NucleaiMD, and Edocate. MM reports reported receiving a research grant from AstraZeneca, being a speaker for AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, Novartis, Abbvie, and Takeda, and being a consultant for MSD and Takeda. DR reports being a speaker for BMS. RY reports receiving research grant from Roche, being a speaker for Roche, Novartis, MSD, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly, and being a consultant for Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Medison, AstraZeneca, Gilead, and Eli Lilly. SS reports receiving a research grant from Can-Fite, AstraZeneca, Bioline RX, BMS, Halozyme, Clovis Oncology, CTG Pharma, Exelexis, Geicam, Halozyme, Incyte, Lilly, Moderna, Teva pharmaceuticals, and Roche, and owning stocks and options in CTG Pharma, DocBoxMD, Tyrnovo, VYPE, Cytora, and CAN-FITE. Author KG was employed by Leumit Health Services.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Cook, DI, Gebski, VJ, and Keech, AC. Subgroup Analysis in Clinical Trials. Med J Aust (2004) 180:289–91. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05928.x

2. Thatcher, N, Chang, A, Parikh, P, Rodrigues Pereira, J, Ciuleanu, T, von Pawel, J, et al. Gefitinib Plus Best Supportive Care in Previously Treated Patients With Refractory Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results From a Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Multicentre Study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer). The Lancet (2005) 366:1527–37. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8

3. Shepherd, FA, Rodrigues Pereira, J, Ciuleanu, T, Tan, EH, Hirsh, V, Thongprasert, S, et al. Erlotinib in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2005) 353:123–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050753

4. Kim, ES, Hirsh, V, Mok, T, Socinski, MA, Gervais, R, Wu, YL, et al. Gefitinib Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (INTEREST): A Randomised Phase III Trial. The Lancet (2008) 372:1809–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4

5. Mok, TS, Wu, YL, Thongprasert, S, Yang, CH, Chu, DT, Saijo, N, et al. Gefitinib or Carboplatin-Paclitaxel in Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med (2009) 361:947–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699

6. Maemondo, M, Inoue, A, Kobayashi, K, Sugawara, S, Oizumi, S, Isobe, H, et al. Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med (2010) 362:2380–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909530

7. Garassino, MC, Martelli, O, Broggini, M, Farina, G, Veronese, S, Rulli, E, et al. Erlotinib Versus Docetaxel as Second-Line Treatment of Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Wild-Type EGFR Tumours (TAILOR): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol (2013) 14:981–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70310-3

8. Kazandjian, D, Blumenthal, GM, Yuan, W, He, K, Keegan, P, and Pazdur, R. FDA Approval of Gefitinib for the Treatment of Patients With Metastatic EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2016) 22:1307–12. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2266

9. Cohen, MH, Williams, GA, Sridhara, R, Chen, G, McGuinn, WD, Morse, D, et al. United States Food and Drug Administration Drug Approval Summary: Gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) Tablets. Clin Cancer Res (2004) 10:1212–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0564

10. Wang, R, Lagakos, SW, Ware, JH, Hunter, DJ, and Drazen, JM. Statistics in Medicine--Reporting of Subgroup Analyses in Clinical Trials. N Engl J Med (2007) 357:2189–94. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr077003

11. Dane, A, Spencer, A, Rosenkranz, G, Lipkovich, I, and Parke, T. Subgroup Analysis and Interpretation for Phase 3 Confirmatory Trials: White Paper of the EFSPI/PSI Working Group on Subgroup Analysis. Pharm Stat (2019) 18:126–39. doi:10.1002/pst.1919

12. FDA Resources for Information. FDA Expands Pembrolizumab Indication for First-Line Treatment of NSCLC (TPS ≥1%) (2019). Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-expands-pembrolizumab-indication-first-line-treatment-nsclc-tps-1 (Accessed September 5, 2023).

13. Mok, TSK, Wu, YL, Kudaba, I, Kowalski, DM, Cho, BC, Turna, HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Previously Untreated, PD-L1-Expressing, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A Randomised, Open-Label, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet (2019) 393:1819–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7

14. NCCN guidelines. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. V5 (2021). Available from: https://www.nccn.org/login?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (Accessed July 10, 2021).

15. Hanna, NH, Robinson, AG, Temin, S, Baker, S, Brahmer, JR, Ellis, PM, et al. Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Driver Alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) Joint Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol (2021) 39:1040–91. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.03570

16. KEYTRUDA. Haarlem, The Netherlands: Merck Sharp and Dohme B.V and Schering-Plough Labo NV. EMA (2020).

17. Antonia, SJ, Villegas, A, Daniel, D, Vicente, D, Murakami, S, Hui, R, et al. Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2017) 377:1919–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709937

18. Antonia, SJ, Villegas, A, Daniel, D, Vicente, D, Murakami, S, Hui, R, et al. Overall Survival With Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med (2018) 379:2342–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1809697

19. NCCN Guidelines. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. V1 (2023). Available from: https://www.nccn.org/login?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2022).

20. IMFINZI. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. Wilmington, DE: Delaware State Chamber of Commerce (2018).

22. ESMO. Update - Early and Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: An Update of the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines Focusing on Diagnosis, Staging and Systemic and Local Therapy (2021). Available from: https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/lung-and-chest-tumours/early-stage-and-locally-advanced-non-metastatic-non-small-cell-lung-cancer/eupdate-early-and-locally-advanced-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-nsclc-treatment-recommendations2 (Accessed November 10, 2022).

23. Paz-Ares, L, Spira, A, Raben, D, Planchard, D, Cho, BC, Ozguroglu, M, et al. Outcomes With Durvalumab by Tumour PD-L1 Expression in Unresectable, Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the PACIFIC Trial. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:798–806. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.287

24. Spigel, DR, Faivre-Finn, C, Gray, JE, Vicente, D, Planchard, D, Paz-Ares, L, et al. Five-Year Survival Outcomes From the PACIFIC Trial: Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:1301–11. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01308

25. Faivre-Finn, C, Vicente, D, Kurata, T, Planchard, D, Paz-Ares, L, Vansteenkiste, JF, et al. Four-Year Survival With Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC-An Update From the PACIFIC Trial. J Thorac Oncol (2021) 16:860–7. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.015

26. Peters, S, Dafni, U, Boyer, M, De Ruysscher, D, Faivre-Finn, C, Felip, E, et al. Position of a Panel of International Lung Cancer Experts on the Approval Decision for Use of Durvalumab in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Ann Oncol (2019) 30:161–5. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy553

27. Chan, A, Delaloge, S, Holmes, FA, Moy, B, Iwata, H, Harvey, VJ, et al. Neratinib After Trastuzumab-Based Adjuvant Therapy in Patients With HER2-Positive Breast Cancer (ExteNET): A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(15):367–77. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00551-3

29. Chan, A, Moy, B, Mansi, J, Ejlertsen, B, Holmes, FA, Chia, S, et al. Final Efficacy Results of Neratinib in HER2-Positive Hormone Receptor-Positive Early-Stage Breast Cancer From the Phase III ExteNET Trial. Clin Breast Cancer (2021) 21:80–91 e7. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2020.09.014

30. NCCN Guidelines. Breast Cancer. V4.2023. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1419 (Accessed September 5, 2023).

31. Martin, M, Holmes, FA, Ejlertsen, B, Delaloge, S, Moy, B, Iwata, H, et al. Neratinib After Trastuzumab-Based Adjuvant Therapy in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer (ExteNET): 5-Year Analysis of a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:1688–700. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30717-9

32. von Minckwitz, G, Procter, M, de Azambuja, E, Zardavas, D, Benyunes, M, Viale, G, et al. Adjuvant Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab in Early HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med (2017) 377:122–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1703643

33. FDA Resources for Information. FDA grants Regular Approval to Pertuzumab for Adjuvant Treatment of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer (2017). Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-regular-approval-pertuzumab-adjuvant-treatment-her2-positive-breast-cancer (Accessed November 10, 2022).

34. Cardoso, F, Kyriakides, S, Ohno, S, Penault-Llorca, F, Poortmans, P, Rubio, IT, et al. Early Breast Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann Oncol (2019) 30:1194–220. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz173

36. Sparano, JA, Gray, RJ, Makower, DF, Pritchard, KI, Albain, KS, Hayes, DF, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med (2018) 379:111–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1804710

37. Kalinsky, K, Barlow, WE, Gralow, JR, Meric-Bernstam, F, Albain, KS, Hayes, DF, et al. 21-Gene Assay to Inform Chemotherapy Benefit in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med (2021) 385:2336–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2108873

38. Piccart, M, van 't Veer, LJ, Poncet, C, Lopes Cardozo, JMN, Delaloge, S, Pierga, JY, et al. 70-Gene Signature as an Aid for Treatment Decisions in Early Breast Cancer: Updated Results of the Phase 3 Randomised MINDACT Trial With an Exploratory Analysis by Age. Lancet Oncol (2021) 22:476–88. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3

39. Andre, F, Ismaila, N, Allison, KH, Barlow, WE, Collyar, DE, Damodaran, S, et al. Biomarkers for Adjuvant Endocrine and Chemotherapy in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol (2022) 40:1816–37. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00069

Keywords: cancer, clinical outcomes, clinical trial, guidelines, reporting, subanalysis, treatment

Citation: Rotem O, Geiger KR, Hanovich E, Moskovitz M, Kurman N, Reinhorn D, Peretz I, Yerushalmi R and Stemmer SM (2024) Seeing the Trees From the Forest: Challenges in Subgroup Analysis-Based Guidelines in Oncology. Oncol. Rev. 18:1355256. doi: 10.3389/or.2024.1355256

Received: 13 December 2023; Accepted: 03 May 2024;

Published: 24 May 2024.

Edited by:

David Chia, University of California, Los Angeles, United StatesReviewed by:

Taroh Satoh, Osaka University, JapanCopyright © 2024 Rotem, Geiger, Hanovich, Moskovitz, Kurman, Reinhorn, Peretz, Yerushalmi and Stemmer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ofer Rotem, b2Zlcjc5MTU1QHlhaG9vLmNvbS5hdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.