94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Vet. Sci. , 19 February 2025

Sec. Parasitology

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2025.1514525

This article is part of the Research Topic Parasites in One Health Interface View all 18 articles

Shuo Liu1†

Shuo Liu1† Miao Zhang1†

Miao Zhang1† Nian-Yu Xue2,3

Nian-Yu Xue2,3 Hai-Tao Wang1

Hai-Tao Wang1 Zhong-Yuan Li4

Zhong-Yuan Li4 Ya Qin5

Ya Qin5 Xue-Min Li1

Xue-Min Li1 Qing-Yu Hou1

Qing-Yu Hou1 Jing Jiang2*

Jing Jiang2* Xing Yang6

Xing Yang6 Hong-Bo Ni1

Hong-Bo Ni1 Jian-Xin Wen1*

Jian-Xin Wen1*Giardia intestinalis is a widespread protozoan parasite associated with significant health risks in humans and animals. However, there is a lack of epidemiological data regarding this parasite in fur-animals. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence and assemblage distribution of G. intestinalis in fur-animals in northern China. A total of 871 fecal samples were detected by nested PCR. The results showed an overall infection rate of 1.15%, with the highest rate in Hebei province (2.28%), while no positive cases were observed in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces. Although no significant differences were found in species group, raccoon dogs (1.72%) were more susceptible to infection than mink (1.40%) and foxes (0.57%). Additionally, the highest infection rate was observed in farms with fewer than 2,000 animals (1.41%), followed by farms with ≥5,000 (0.93%) and those with 2,000–5,000 animals (0.75%). The infection rate was higher in juvenile animals (1.35%) compared to adults (1.08%), and in non-diarrheal animals (1.16%) compared to diarrheal animals (1.08%). Notably, this study is the first to report assemblage A in mink, this finding highlight the potential role of mink as a reservoir for zoonotic transmission. Assemblage D was detected in foxes and raccoon dogs, further suggesting that these animals may serve as potential zoonotic reservoirs. These findings not only complements the epidemiological data of G. intestinalis in fur-animals but also emphasize the importance of monitoring the fur industry to mitigate public health risks.

Giardia intestinalis (Syn. G. duodenalis or G. lamblia) is a flagellated protozoan parasite that widely infects the intestines of humans and various animals (1). It spreads through direct and indirect contact (via food and water) (2). Globally, G. intestinalis is one of the leading pathogens responsible for parasitic-related diarrhea, with infection rates strongly correlated with regional sanitation conditions. The prevalence in developed countries is significantly lower than in developing countries (3). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that approximately 280 million people are infected with this parasite annually, resulting in acute diarrhea (4). Additionally, individuals infected with G. intestinalis may face long-term health risks, including irritable bowel syndrome, childhood malnutrition, and arthritis (5–7). Furthermore, the rise of cross-border animal trade complicates public health control efforts, blurring the lines of parasite transmission and increasing the urgency for effective global surveillance and management strategies.

Molecular biology techniques have been widely applied in the study of G. intestinalis. Common methods include small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) analysis and multilocus genotyping (gdh, tpi, and bg genes) (8). Through molecular analysis, G. intestinalis has been divided into eight assemblages (A–H) (9). Among these, assemblages A and B exhibit strong cross-host transmission capabilities, infecting diverse hosts, including humans, and are typical zoonotic pathogens (10–12). In contrast, assemblages C–H show distinct host specificity. Studies have shown that assemblages C and D primarily infect canines (10, 13), assemblage E mainly infects ungulates such as cattle and sheep (14, 15), assemblages F and H have been detected in marine animals (16, 17), assemblage G was specifically found in rodents (15, 18).

Interestingly, despite assemblages C and D typically being considered exclusive to canines, research has shown some exceptions. Assemblage D was detected in a German traveller, and a study in Egypt identified assemblage C as a zoonotic pathogen (19, 20). These findings suggest that the host range of G. intestinalis may be broader than previously known. Therefore, expanding our understanding of its host adaptability is crucial for effective disease control and prevention strategies.

The fur animal farming industry in northern China is large-scale and is one of the pillars of the local economy. However, with the development of large-scale farming, disease prevention and control face significant challenges. Research has shown that fur animals can be infected with various parasites, including Pentatrichomonas hominis, Sarcocystis spp., and Trichinella spiralis (21–23), indicating that fur animals may be potential hosts for zoonotic pathogens. However, reports on the infection of fur animals (mink, foxes, and raccoon dogs) with G. intestinalis are scarce globally. This study employs tpi, gdh, and bg gene analysis to test samples from mink, foxes, and raccoon dogs, aiming to investigate the infection rates of G. intestinalis and the diversity and distribution of assemblage in these animals as well as to assess the implications for public health and disease prevention in the farming industry.

From October 2023 to May 2024, 871 fresh fecal samples were randomly collected from farmed fur animals in main fur farming provinces of China (Shandong, Hebei, Jilin, Liaoning, and Heilongjiang). The samples included mink (n = 286), foxes (n = 352), and raccoon dogs (n = 233) (Figure 1). All animals are self-breed and kept in cages, foxes and raccoon dogs are breed in individual cages, while minks are breed in group cages with three to five animals. No direct contact with animals, fresh feces were collected immediately from beneath the cages using disposable PE gloves when the animal excreted feces. Detailed records of sample’s source animal, sample ID, sampling position, date, animal age, health status, species, and farm size. To maintain sample integrity, samples were stored in 12 mL collection tubes, transported to the laboratory on dry ice, and preserved at −80°C.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, genomic DNA was extracted from each sample using the E.Z.N.A.® Stool DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA, United States) and stored at −20°C until PCR analysis. First, the β-giardin (bg) gene was amplified using nested PCR to confirm the presence of G. intestinalis in the samples. Subsequently, the positive samples were subjected to amplification of the glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) and triosephosphate isomerase (tpi) genes (24–26). The first round was performed with a 25 μL reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL of premix enzyme (dNTPs, DNA polymerase, buffer and Mg2+), 8.5 μL of ddH2O, 1 μL of forward primer, 1 μL of reverse primer, and 2 μL of template DNA. In the second round, 2 μL of the first-round product was mixed with 25 μL of premix enzyme, 21 μL of ddH2O, 1 μL of forward primer, and 1 μL of reverse primer, in a total volume of 50 μL. Then, 5 μL of the product was tested using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Positive PCR products were sequenced by Anhui General Biosystems Co., Ltd. (Anhui China) using Sanger sequencing.

The sequences of the bg and gdh genes were obtained from Anhui General Corporation. BLAST1 was used to align these sequences with the corresponding bg, and gdh reference sequences in GenBank. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbour-joining (NJ) method in MEGA11 software2 to study the relationships between different isolates and to illustrate the genetic diversity of G. intestinalis (27). The reliability of the phylogenetic analysis was evaluated through 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Chi-square analysis in SAS (v9.0) software was used to evaluate the impact of sampling region (x1), species (x2), farming scale (x3), health status (x4), and age (x5) on the infection rate of G. intestinalis (y). In the multivariable regression analysis, each variable was individually included in the binary logistic model. The best model was selected using the Fisher scoring method. In the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) software, chi-square tests were performed to explore the differences in the prevalence of G. intestinalis across various study factors while calculating the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

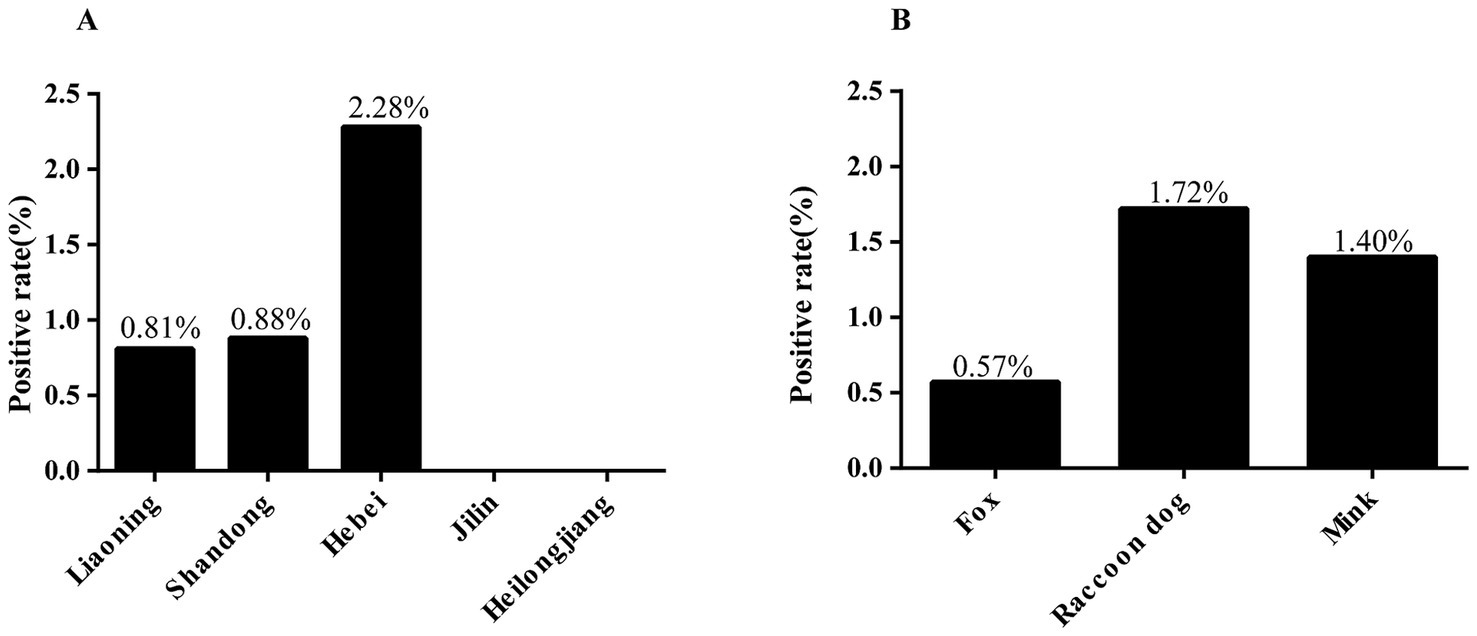

In the present study, 10 (1.15%) positive cases of G. intestinalis were detected through nested PCR from 871 fecal samples. The differences in infection rates among provinces were not statistically significant (χ2 = 5.88, df = 4, p = 0.2082). Hebei province had the highest infection rate (2.28%, 7/307, OR = 2.86 95% CI 0.59–13.88), followed by Shandong province (0.88%, 1/113, OR = 1.09 95% CI 0.10–12.19) and Liaoning province (0.81%, 2/247), while no positive cases were observed in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces (Table 1 and Figure 2A). Similarly, the differences in infection rates between species were not statistically significant (χ2 = 2, df = 2, p = 0.3680). Raccoon dogs had the highest infection rate (1.72%, 4/233, OR = 3.06 95% CI 0.56–16.83), followed by mink (1.40%, 4/286, OR = 2.48 95% CI 0.45–13.65) and foxes (0.57%, 2/352) (Table 1 and Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Infection rate of G. intestinalis in fur-animals under various factors. (A) Infection rate of G. intestinalis in fur-animals in different provinces. (B) Infection rate of G. intestinalis in different species.

There was no statistically significant difference in the farm size group (χ2 = 0.49, df = 2, p = 0.7837), with the lowest infection rate was observed in farms with 2,000 to 5,000 animals (0.75%, 2/266), the highest infection rate was found in farms with fewer than 2,000 animals (1.41%, 7/498, OR = 1.88 95% CI 0.39–9.12), and the infection rate of farms with more than 5,000 was 0.94% (1/107, OR = 1.25 95% CI 0.11–13.88). Additionally, the infection rate in adult animals (1.08%, 7/649) was slightly lower than in juvenile animals (1.35%, 3/222, OR = 1.26 95% CI 0.32–4.90), the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.21, df = 1, p = 0.6481). The infection rate in non-diarrheal animals (1.16%, 9/778 OR = 1.08 95% CI 0.14–8.60) was slightly higher than in diarrheal animals (1.08%, 1/93), and the statistical difference was not significant (χ2 = 0.07, df = 1, p = 0.7947) (Table 1).

The present study evaluated the influencing factors affecting the infection rate of G. intestinalis using logistic forward stepwise regression analysis. The final best model included sampling region and health status. The model equation is y = −7.2133x1 + 0.8197x2 + 3.8666.

The results show that the sampling area negatively affects the infection rate of G. intestinalis (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.09–1.81). Hebei had the highest infection rate (OR = 2.86, 95% CI 0.59–13.88), followed by Shandong (OR = 1.09, 95% CI 0.10–12.19) and Liaoning (0.81%, 2/247). No infections were observed in Jilin (OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.03–14.07) and Heilongjiang (OR = 0.37, 95% CI 0.02–7.84). Health status positively influences infection (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.36–1.82), and the infection rate in diarrheal animals (1.08%, 1/93) was lower than in non-diarrheal animals (OR = 1.08, 95% CI 0.14–8.60) (Table 1).

The present study conducted nested PCR detection on 871 fecal samples, identifying 10 positive samples for the bg gene and obtaining six assembled sequences. Among these, three samples from mink belonged to assemblage A. Additionally, one sample from foxes and two from raccoon dogs were classified as assemblage D (Table 2).

We further tested the bg gene-positive samples to amplify the gdh gene, successfully obtaining six gdh sequences. Analysis of the gdh gene sequences showed that three mink samples belonged to assemblage A as well as two fox samples and one raccoon dog sample belonged to assemblage D. Meanwhile, we detected the tpi gene, but failed to obtain any sequences (Table 2).

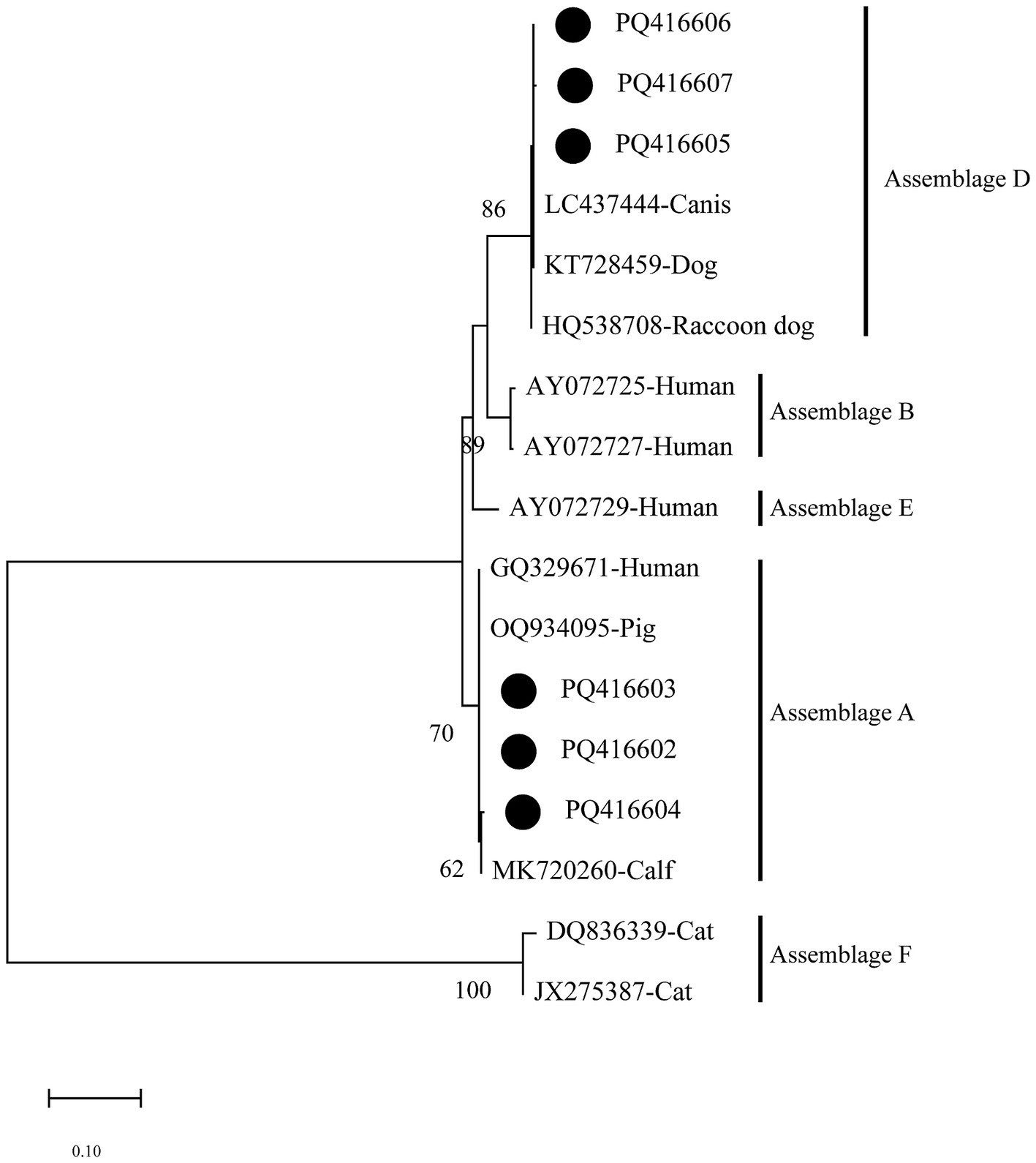

Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the bg gene, the results indicated that sequences PQ416602–PQ416604 primarily cluster in the branch of assemblage A. PQ416604 is grouped with MK720260 (Calf) in the same branch, forming a sister group with PQ416602, PQ416603, and GQ329671 (Human). Meanwhile, sequences PQ416605–PQ416607 cluster with LC437444 (Canis) in the branch of assemblage D, demonstrating a high degree of phylogenetic relationship (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Evolutionary relationships among Giardia intestinalis inferred by neighbour-joining analysis using the Kimura 2-parameter model of bg gene sequences. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates, with only those greater than 50% shown. The sequences obtained in the present study are represented by black dots.

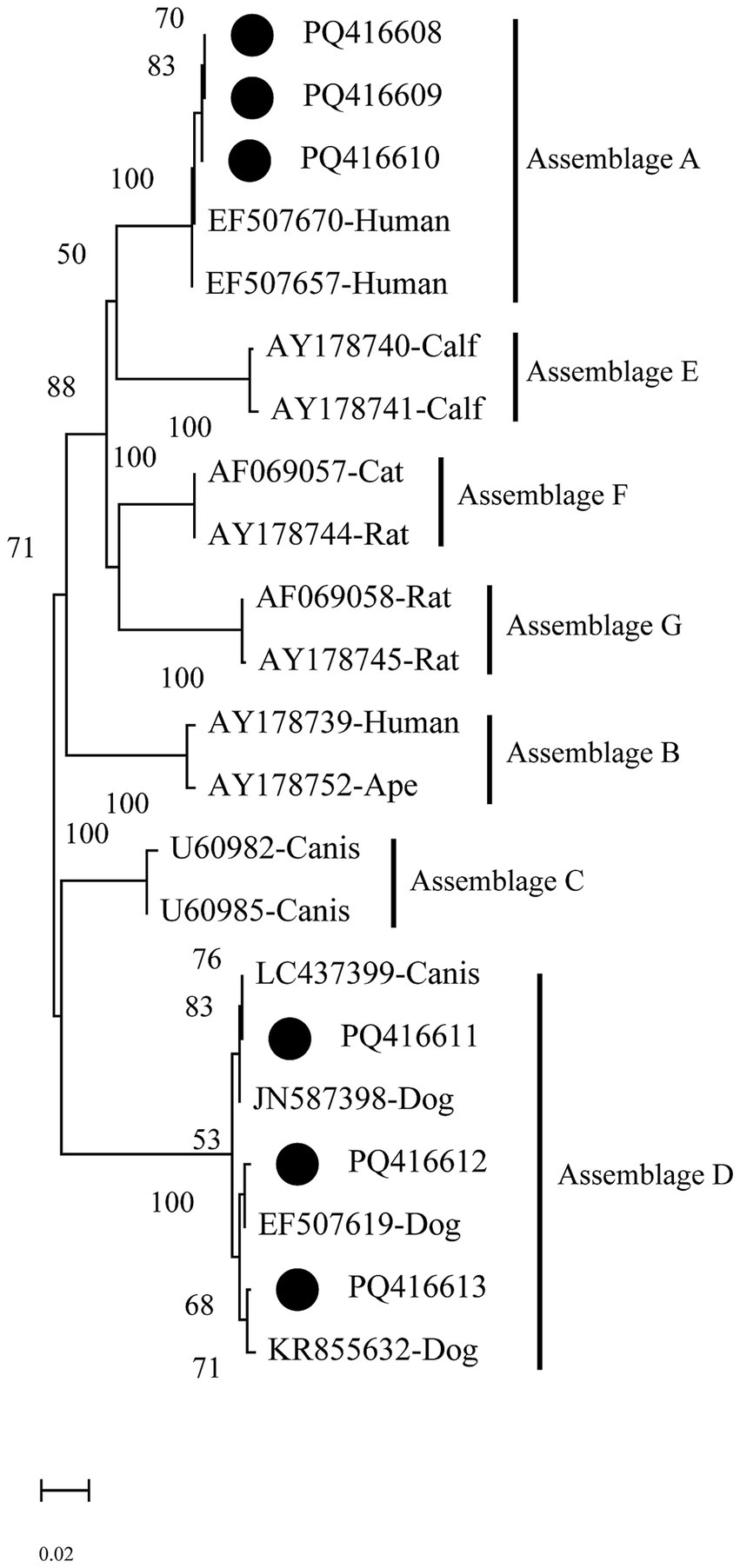

The phylogenetic analysis of the gdh gene shows that PQ416608–PQ416610 cluster in the branch of assemblage A and group together with EF507670 (Human) and EF507657 (Human), exhibiting a 100% bootstrap support value, indicating a high degree of phylogenetic relationship with human-derived Giardia. On the other hand, sequences PQ416611–PQ416613 mainly cluster in the branch of assemblage D, where they group with LC437399 (Canis), EF507619 (Dog), and KR855632 (Dog), indicating a close genetic similarity with the Giardia assemblages of canine hosts (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Evolutionary relationships among Giardia intestinalis inferred by neighbour-joining analysis using the Kimura 2-parameter model of gdh gene sequences. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates, with only those greater than 50% shown. The sequences obtained in the present study are represented by black dots.

Foodborne zoonotic diseases are a significant global public health issue, especially in regions with frequent agricultural and livestock activities. These diseases not only threaten animal health but also pose potential risks to human health, particularly when the sources of transmission are complex (28). G. intestinalis, a typical foodborne zoonotic pathogen, has been confirmed to transmit between humans and various animals, and it poses a severe threat to immunocompromised individuals (29). Therefore, studying the epidemiological characteristics of this parasite is of utmost importance. In this study, we tested farmed fur-animals in northern China, and the overall prevalence of G. intestinalis in fur-animals was 1.15% (10/871), which was lower than other animal populations in China, such as cattle in Shanxi province (28.3%, 243/858), dogs in Liaoning province (13.2%, 27/205), black bears in Heilongjiang province (8.3%, 3/36), and donkeys in Jilin, Lioning, and Shandong provinces (15.5%, 28/181) (13, 30–33). The difference may be related to species differences, sample size and living habits. Interestingly, in this study, animals showed different susceptibilities to the disease, raccoon dogs had the highest infection rate (1.72%, 4/233), followed by mink (1.40%, 4/286) and foxes (0.57%, 2/352). although, no significant differences were found among them, which may be related to the small sample size. Future studies could increase the sample size and further investigate the infection mechanisms of G. intestinalis to difference species.

In the present study, the sampling region negatively affected the infection rates of G. intestinalis. The highest infection rate was observed in Hebei province (2.28%, 7/307), followed by Shandong province (0.88%, 1/113) and Liaoning province (0.81%, 2/247). Notably, no positive cases were detected in Jilin (0/73) and Heilongjiang (0/131) provinces, suggesting a lower risk of infection in these regions. However, a report showed that the infection rate of G. intestinalis in diarrhea patients in Heilongjiang was 5.81%, which indicated that the epidemic prevention and control situation was still not optimistic (31). Future studies should aim to expand both the sample size and the range of animal testing. Furthermore, the present study also found that the health status of animals was an important influencing factor affecting the infection rate of G. intestinalis. The infection rate in non-diarrheal animals was 1.16% (9/778) higher than the 1.08% (1/93) observed in diarrheal animals. This contrasts with findings in cattle in Shanxi province and children in Zhejiang province (30, 34). This difference may be related to the stages of G. intestinalis infection and the pathogenic mechanisms that cause diarrhea. Additionally, the host’s age, immune status, and co-infections with other pathogens may also influence the clinical manifestations and transmission patterns of G. intestinalis infection.

In this study, no significant differences in infection rates were observed between farms with different farming sizes. Notably, the infection rate of farms with less than 2,000 animals (1.41%, 7/498) was higher than that of farms with 2,000–5,000 animals (0.75%, 2/266) and ≥5,000 animals (0.93%, 1/107). These small-scale farms are usually family-run, and the technical level of feeding management, disease prevention and control is relatively low. Additionally, some farms have the phenomenon of raising dogs together, which may be a factor leading to the high infection rate.

Researchers have classified G. intestinalis into eight genotype assemblages (A–H), based on common genetic markers such as the SSU rRNA gene, and the gdh, bg, and tpi loci (9). In the present study, G. intestinalis in fur-animals were identified primarily as assemblages A (n = 3) and D (n = 3) through the analysis of bg and gdh genes. Among them, assemblage A was the dominant assemblage in mink, consistent with studies on ferrets in Europe and Japan, confirming that assemblage A was common in mustelids (35–37). Assemblage A is distributed globally across mammals and poultry and is recognised as an important pathogen responsible for human infections (3, 9, 33, 38). The discovery of assemblage A in mink in this study indicates that mink may be a potential host for human infections. Notably, pathological reports indicate that both person-to-person and person-to-animal transmission can occur through direct contact (49). Therefore, it is recommended to further investigate the infection rates among farmers and industry workers to prevent the spread to other animal populations or human communities.

Assemblages C and D were the most common genotypes in canids globally (9). They were widely reported in dogs (13, 39, 40). In China, these assemblages have also been detected in dogs from Xinjiang and raccoon dogs from Jilin (41). In the present study, assemblage D was found in foxes and raccoon dogs, consistent with studies on foxes in Australia and raccoon dogs in Poland (42, 43). However, assemblage C was not detected in this study, which may be related to sample size, sampling time, and geographic regional differences. Notably, although assemblage D was considered host-specific to canids, existing research shows that it can infect other species, including humans (9). For instance, assemblage D has been detected in German travellers, Australian kangaroos, British cattle, and American chinchillas (19, 37, 43, 44). These findings suggest that assemblage D may cross-infection between wildlife and livestock, posing a potential zoonotic risk.

In this study, the amplification success rates for the bg and gdh genes were relatively high, whereas the tpi gene sequences were not successfully obtained. This suggests that the amplification success rates for bg, gdh, and tpi genes may be associated with different assemblage types, which is consistent with previous studies. For example, Chen et al. (31) successfully obtained 20 bg, 19 gdh, and 9 tpi sequences from 22 positive samples of black bears, while Xiao et al. (45) obtained 70 bg, 32 gdh, and 7 tpi sequences from 90 positive samples of goats. These results indicate that more accurate and sensitive molecular diagnostic techniques are urgently needed to achieve a more precise genetic characterization of G. intestinalis.

G. intestinalis exists as cysts in vegetables, meat and other foods (29). The food source of fur-animals in mainly poultry meat, which may be one of their infection routes. Additionally, G. intestinalis is also wildly present in the environment, particularly in surface water sources (46). In 2013, a waterborne outbreak of G. intestinalis infection was reported in South Korea, highlighting its potential for waterborne transmission (47). In addition to known hosts, there are many unknown hosts that could serve as potential sources of human infection. These potential transmission routes pose a threat to public health security. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen the quarantine of foods such as vegetables and meat, while expanding the sampling scope to include more species for detection. At the same time, treatment of the disease is also crucial. Although metronidazole is the drug of choice for treating giardiasis, its issues with resistance and potential side effects such as abdominal pain and nausea limit its use. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new treatment formulations, such as phytochemicals, to address this challenge (48).

The present study investigated the prevalence of G. intestinalis in fur-animals in northern China, first reporting the occurrence of assemblage A in mink, indicating that mink may be a potential zoonotic source of G. intestinalis, while also contributing to the epidemiological data on this parasite. Additionally, the detection of assemblage D in foxes and raccoon dogs suggests a similar zoonotic risk. Therefore, attention should be given to the prevalence of G. intestinalis among fur industry workers and their surrounding environments to effectively control and prevent potential transmission risks. However, this study has some limitations. For instance, the tpi gene sequence was not successfully obtained, and the effect of seasonality on prevalence was not investigated. Therefore, future studies should aim to expand the sample size and incorporate seasonal sampling to better understand the infection dynamics of G. intestinalis in fur-animals.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PQ416602-PQ416613.

The animal studies were approved by Research Ethics Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Qingdao Agricultural University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

SL: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. MZ: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. N-YX: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. H-TW: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Z-YL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YQ: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. X-ML: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Q-YH: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JJ: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XY: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. H-BN: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. J-XW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Visualization.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Special Economic Animal Industry System Project of the Modern Agricultural Industry System in Shandong Province (SDAIT-21-13).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Huang, DB, and White, AC. An updated review on Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. (2006) 35:291–314. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.006

2. Drake, J, Sweet, S, Baxendale, K, Hegarty, E, Horr, S, Friis, H, et al. Detection of Giardia and helminths in Western Europe at local K9 (canine) sites (DOGWALKS Study). Parasit Vectors. (2022) 15:311. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05440-2

3. Feng, Y, and Xiao, L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2011) 24:110–40. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-10

4. Einarsson, E, Ma’ayeh, S, and Svärd, SG. An update on Giardia and giardiasis. Curr Opin Microbiol. (2016) 34:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.07.019

5. Cook, DM, Swanson, RC, Eggett, DL, and Booth, GM. A retrospective analysis of the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites among school children in the Palajunoj Valley of Guatemala. J Health Popul Nutr. (2009) 27:31–40. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i1.3321

6. Krol, A. Giardia lamblia as a rare cause of reactive arthritis. Ugeskr Laeger. (2013) 175:V05130347

7. Allain, T, and Buret, AG. Pathogenesis and post-infectious complications in giardiasis. Adv Parasitol. (2020) 107:173–99. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2019.12.001

8. Qi, M, Dong, H, Wang, R, Li, J, Zhao, J, Zhang, L, et al. Infection rate and genetic diversity of Giardia duodenalis in pet and stray dogs in Henan province, China. Parasitol Int. (2016) 65:159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.11.008

9. Heyworth, MF. Giardia duodenalis genetic assemblages and hosts. Parasite. (2016) 23:13. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2016013

10. Berrilli, F, D’Alfonso, R, Giangaspero, A, Marangi, M, Brandonisio, O, Kaboré, Y, et al. Giardia duodenalis genotypes and Cryptosporidium species in humans and domestic animals in Côte d’Ivoire: occurrence and evidence for environmental contamination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. (2012) 106:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.12.005

11. Covacin, C, Aucoin, DP, Elliot, A, and Thompson, RC. Genotypic characterisation of Giardia from domestic dogs in the USA. Vet Parasitol. (2011) 177:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.11.029

12. Traversa, D, Otranto, D, Milillo, P, Latrofa, MS, Giangaspero, A, Cesare, AD, et al. Giardia duodenalis sub-assemblage of animal and human origin in horses. Infect Genet Evol. (2012) 12:1642–6. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.06.014

13. Li, W, Liu, C, Yu, Y, Li, J, Gong, P, Song, M, et al. Molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis isolates from police and farm dogs in China. Exp Parasitol. (2013) 135:223–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.07.009

14. Khan, SM, Debnath, C, Pramanik, AK, Xiao, L, Nozaki, T, and Ganguly, S. Molecular evidence for zoonotic transmission of Giardia duodenalis among dairy farm workers in West Bengal, India. Vet Parasitol. (2011) 178:342–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.029

15. Lebbad, M, Mattsson, JG, Christensson, B, Ljungström, B, Backhans, A, Andersson, JO, et al. From mouse to moose: multilocus genotyping of Giardia isolates from various animal species. Vet Parasitol. (2010) 168:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.11.003

16. Lasek-Nesselquist, E, Welch, DM, and Sogin, ML. The identification of a new Giardia duodenalis assemblage in marine vertebrates and a preliminary analysis of G. Duodenalis population biology in marine systems. Int J Parasitol. (2010) 40:1063–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.02.015

17. Reboredo-Fernández, A, Ares-Mazás, E, Martínez-Cedeira, JA, Romero-Suances, R, Cacciò, SM, and Gómez-Couso, H. Giardia and Cryptosporidium in cetaceans on the European Atlantic coast. Parasitol Res. (2015) 114:693–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4235-8

18. Zhao, Z, Wang, R, Zhao, W, Qi, M, Zhao, J, Zhang, L, et al. Genotyping and subtyping of Giardia and Cryptosporidium isolates from commensal rodents in China. Parasitology. (2015) 142:800–6. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014001929

19. Broglia, A, Weitzel, T, Harms, G, Cacció, SM, and Nöckler, K. Molecular typing of Giardia duodenalis isolates from German travellers. Parasitol Res. (2013) 112:3449–56. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3524-y

20. Soliman, RH, Fuentes, I, and Rubio, JM. Identification of a novel assemblage B subgenotype and a zoonotic assemblage C in human isolates of Giardia intestinalis in Egypt. Parasitol Int. (2011) 60:507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.09.006

21. Song, P, Guo, Y, Zuo, S, Li, L, Liu, F, Zhang, T, et al. Prevalence of Pentatrichomonas hominis in foxes and raccoon dogs and changes in the gut microbiota of infected female foxes in the Hebei and Henan provinces in China. Parasitol Res. (2023) 123:74. doi: 10.1007/s00436-023-08099-5

22. Máca, O, Gudiškis, N, Butkauskas, D, González-Solís, D, and Prakas, P. Red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) as potential spreaders of Sarcocystis species. Front Vet Sci. (2024) 11:1392618. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1392618

23. Zhang, NZ, Li, WH, Yu, HJ, Liu, YJ, Qin, HT, Jia, WZ, et al. Novel study on the prevalence of Trichinella spiralis in farmed American minks (Neovison vison) associated with exposure to wild rats (Rattus norvegicus) in China. Zoonoses Public Health. (2022) 69:938–43. doi: 10.1111/zph.12991

24. Lalle, M, Pozio, E, Capelli, G, Bruschi, F, Crotti, D, and Cacciò, SM. Genetic heterogeneity at the beta-giardin locus among human and animal isolates of Giardia duodenalis and identification of potentially zoonotic subgenotypes. Int J Parasitol. (2005) 35:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.022

25. Cacciò, SM, Beck, R, Lalle, M, Marinculic, A, and Pozio, E. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages a and B. Int J Parasitol. (2008) 38:1523–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.04.008

26. Sulaiman, IM, Fayer, R, Bern, C, Gilman, RH, Trout, JM, Schantz, PM, et al. Triosephosphate isomerase gene characterization and potential zoonotic transmission of Giardia duodenalis. Emerg Infect Dis. (2003) 9:1444–52. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030084

27. Tamura, K, and Stecher, G. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. (2021) 38:3022–7. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

28. Murrell, KD. Zoonotic foodborne parasites and their surveillance. Rev Sci Tech. (2013) 32:559–69. doi: 10.20506/rst.32.2.2239

29. Ryan, U, Hijjawi, N, Feng, Y, and Xiao, L. Giardia: an under-reported foodborne parasite. Int J Parasitol. (2019) 49:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.07.003

30. Zhao, L, Wang, Y, Wang, M, Zhang, S, Wang, L, Zhang, Z, et al. First report of Giardia duodenalis in dairy cattle and beef cattle in Shanxi, China. Mol Biol Rep. (2024) 51:403. doi: 10.1007/s11033-024-09342-7

31. Chen, J, Zhou, L, Cao, W, Xu, J, Yu, K, Zhang, T, et al. Prevalence and assemblage identified of Giardia duodenalis in zoo and farmed Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus) from the Heilongjiang and Fujian provinces of China. Parasite. (2024) 31:50. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2024048

32. Zhang, XX, Zhang, FK, Li, FC, Hou, JL, Zheng, WB, Du, SZ, et al. The presence of Giardia intestinalis in donkeys, Equus asinus, in China. Parasit Vectors. (2017) 10:3. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1936-0

33. Wu, Y, Yao, L, Chen, H, Zhang, W, Jiang, Y, Yang, F, et al. Giardia duodenalis in patients with diarrhea and various animals in northeastern China: prevalence and multilocus genetic characterization. Parasit Vectors. (2022) 15:165. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05269-9

34. Zhao, W, Li, Z, Sun, Y, Li, Y, Xue, X, Zhang, T, et al. Occurrence and multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in diarrheic and asymptomatic children from south of Zhejiang province in China. Acta Trop. (2024) 258:107341. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2024.107341

35. Guo, Y, Li, N, Feng, Y, and Xiao, L. Zoonotic parasites in farmed exotic animals in China: implications to public health. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. (2021) 14:241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2021.02.016

36. Abe, N, Tanoue, T, Noguchi, E, Ohta, G, and Sakai, H. Molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis isolates from domestic ferrets. Parasitol Res. (2010) 106:733–6. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1703-7

37. Pantchev, N, Broglia, A, Paoletti, B, Globokar Vrhovec, M, Bertram, A, Nöckler, K, et al. Occurrence and molecular typing of Giardia isolates in pet rabbits, chinchillas, guinea pigs and ferrets collected in Europe during 2006–2012. Vet Rec. (2014) 175:18. doi: 10.1136/vr.102236

38. Appelbee, AJ, Thompson, RC, and Olson, ME. Giardia and Cryptosporidium in mammalian wildlife—current status and future needs. Trends Parasitol. (2005) 21:370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.06.004

39. Yun, CS, Moon, BY, Lee, K, Hwang, SH, Ku, BK, and Hwang, MH. Prevalence and genotype analysis of Cryptosporidium and Giardia duodenalis from shelter dogs in South Korea. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. (2024) 55:101103. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2024.101103

40. Kabir, MHB, and Kato, K. Examining the molecular epidemiology of Giardia and Eimeria species in Japan: a comprehensive review. J Vet Med Sci. (2024) 86:563–74. doi: 10.1292/jvms.23-0525

41. Cao, Y, Fang, C, Deng, J, Yu, F, Ma, D, Chuai, L, et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in pet dogs in Xinjiang, China. Parasitol Res. (2022) 121:1429–35. doi: 10.1007/s00436-022-07468-w

42. Solarczyk, P, Majewska, AC, Jędrzejewski, S, Górecki, MT, Nowicki, S, and Przysiecki, P. First record of Giardia assemblage D infection in farmed raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides). Ann Agric Environ Med. (2016) 23:696–8. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1226869

43. Ng, J, Yang, R, Whiffin, V, Cox, P, and Ryan, U. Identification of zoonotic Cryptosporidium and Giardia genotypes infecting animals in Sydney’s water catchments. Exp Parasitol. (2011) 128:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.02.013

44. Minetti, C, Taweenan, W, Hogg, R, Featherstone, C, Randle, N, Latham, SM, et al. Occurrence and diversity of Giardia duodenalis assemblages in livestock in the UK. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2014) 61:e60–7. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12075

45. Xiao, HD, Su, N, Zhang, ZD, Dai, LL, Luo, JL, Zhu, XQ, et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Giardia duodenalis and Blastocystis spp. in black goats in Shanxi province, North China: from a public health perspective. Animals. (2024) 14:1808. doi: 10.3390/ani14121808

46. Xiao, G, Qiu, Z, Qi, J, Chen, JA, Liu, F, Liu, W, et al. Occurrence and potential health risk of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in the three gorges reservoir, China. Water Res. (2013) 47:2431–45. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.02.019

47. Cheun, HI, Kim, CH, Cho, SH, Ma, DW, Goo, BL, Na, MS, et al. The first outbreak of giardiasis with drinking water in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. (2013) 4:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2013.03.003

48. Alawfi, BS. A review on the use of phytochemicals for the control of zoonotic giardiasis. Pak Vet J. (2024) 44:592–8. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2024.251

Keywords: prevalence, Giardia intestinalis, assemblage, mink, raccoon dog

Citation: Liu S, Zhang M, Xue N-Y, Wang H-T, Li Z-Y, Qin Y, Li X-M, Hou Q-Y, Jiang J, Yang X, Ni H-B and Wen J-X (2025) Prevalence and assemblage distribution of Giardia intestinalis in farmed mink, foxes, and raccoon dogs in northern China. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1514525. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1514525

Received: 21 October 2024; Accepted: 03 February 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

Mughees Aizaz Alvi, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, PakistanReviewed by:

Zi-Guo Yuan, South China Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Liu, Zhang, Xue, Wang, Li, Qin, Li, Hou, Jiang, Yang, Ni and Wen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Jiang, amlhbmdqaW5neGlhb3lhb0AxNjMuY29t; Jian-Xin Wen, d2VuamlhbnhpbkAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.