94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Vet. Sci. , 31 January 2025

Sec. Veterinary Infectious Diseases

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2025.1512387

This article is part of the Research Topic Biosecurity of Infectious Diseases in Veterinary Medicine View all 8 articles

YingWu Qiu1,2†

YingWu Qiu1,2† QunHui Li2†

QunHui Li2† WenKai Zhao2

WenKai Zhao2 Hao Chang1,2

Hao Chang1,2 JunHua Wang3

JunHua Wang3 Qi Gao1,4

Qi Gao1,4 Qingfeng Zhou2

Qingfeng Zhou2 GuiHong Zhang1,4

GuiHong Zhang1,4 Lang Gong1,4*

Lang Gong1,4* LianXiang Wang2*

LianXiang Wang2*UV exposure is a common method of disinfection and sterilization. In the present study, the parallel beam test was performed to collect fluids containing infectious viruses using a parallel beam apparatus after UV254 irradiation (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, or 20 mJ/cm2). The air sterilization test was performed by irradiating the air in the ducts with UV254 light (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 6 mJ/cm2) to collect airborne particles containing viruses through the air sterilization equipment. Furthermore, viral inactivation was assessed based on cytopathic effect (CPE) detection and immunofluorescent assays (IFA). Both the CPE and immunofluorescence signal intensity decreased as the UV254 dose increased. The UV254 doses required to inactivate ASFV (107.75 copies/mL), PRRSV (106.29 copies/mL), and PEDV (107.71 copies/mL) in the water were 3, 1, and 1 mJ/cm2, respectively. The UV254 dose required to inactivate ASFV (104.06 copies/mL), PRRSV (103.06 copies/mL), and PEDV (104.68 copies/mL) in the air was 1 mJ/cm2. This study provides data required for biosecurity prevention and control in swine farms.

China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of pork, producing approximately 53% of the global pork supply (1). Furthermore, pork is the main source of high-quality protein for Chinese residents, with the consumption accounting for 62% of total meat consumption (2). Infectious diseases represent a major constraint to pig production (3). Since the first outbreak of African swine fever (ASF) in China in August 2018, ASF, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), and porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) have emerged as the three most serious viral diseases in Chinese pig farms (4). These diseases are highly transmissible and pathogenic, with rapid mutation of the virulent strains, resulting in abortions in sows, growth delay in fattening pigs, and mass mortality among piglets (5, 6). When these diseases occur on pig farms, it is difficult to achieve decontamination because of the labor and resources required to control the spread of the disease in the herd. Notably, ASF virus (ASFV), PRRS virus (PRRSV), and PED virus (PEDV) can be transmitted through the air, further complicating disease prevention and control efforts in the entire Chinese pig farming industry (7–10).

UV disinfection is one of the most commonly used methods for preventing air-mediated microbial disease transmission because of its low cost, simple installation, ease of maintenance, and significant effectiveness (11, 12). UV light can inactivate pathogenic microorganisms through several mechanisms, such as the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in nucleic acids, which ultimately inhibit transcription and replication (13). In addition, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) results in the oxidation of macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates inside the cells and leads to cell membrane and cell wall damage (14). Table 1 provides a summary of recent studies on the effectiveness of UV in inactivating various viruses. From these references, we can identify that in addition to the UV dose, important factors affecting UV disinfection include the wavelength of the UV light used, the type of virus, the environmental conditions, and the medium through which UV light is transmitted.

Previous studies have shown that UV disinfection is an effective method to inactivate a wide range of pathogenic microorganisms, including various phages and viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 (15–22). This study aimed to evaluate the inactivating effect of UV254 light, a UV-C wavelength, on common airborne porcine viruses, providing critical data for the prevention and control of animal diseases.

ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV were obtained from the National Regional Laboratory for African Swine Fever (Guangzhou) of South China Agricultural University (Guangzhou, China). Porcine primary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of 4-week-old healthy piglets. Marc-145 and Vero cells were obtained via direct passage. Then, 1% porcine erythrocyte suspension was prepared using EDTA-treated fresh porcine blood. Viral stock solutions were diluted to 1 × 106 and 1 × 103 TCID50 using autoclaved ddH2O for parallel beam UV254 experiments. A nebulizer aerosolized 15 mL of virus stock solution for each air sampler operation, with a collection duration of 15 min per sampling. Three replications of each experiment were performed. All viral manipulations in cells were conducted at the BSL-3 laboratory of the College of Veterinary Medicine, South China Agricultural University.

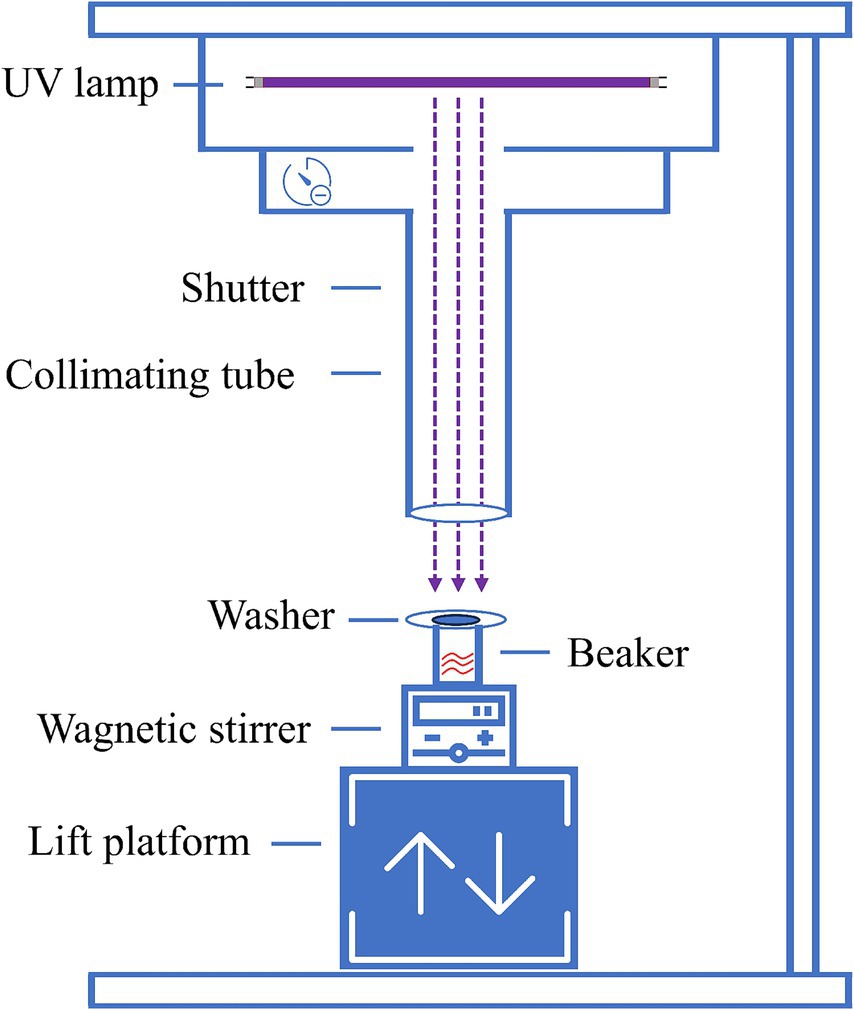

As shown in Figure 1, compared with traditional UV radiometers, the parallel beam apparatus optimizes beam collimation and uniformity, enabling more precise control and measurement of UV254 irradiance, thereby enhancing the reliability of experimental results (23). Parallel beam UV254 experiments were performed by fixing the UV254 illumination of the light source and using different TCID50 values for viruses and varying durations of UV254 irradiation. As presented in Supplementary Table S1, the duration of irradiation using the 36-W UV254 lamp (wavelength = 254 nm) were set to 0, 3.5, 6.9, 20.8, 34.6, 48.4, 69.2, or 138.4 s, and the UV254 dose was set to 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, or 20 mJ/cm2. After irradiating ASFV (TCID50 = 1 × 106/CT = 16.45, TCID50 = 1 × 103/CT = 29.64), PRRSV (TCID50 = 1 × 106/CT = 14.36, TCID50 = 1 × 103/CT = 25.36), and PEDV (TCID50 = 1 × 106/CT = 16.60, TCID50 = 1 × 103/CT = 27.47), viral inactivation was detected by assessing cytopathic effects (CPEs) and performing IFAs to determine the UV254 dose required for killing effects. Three replications of each experiment were performed.

Figure 1. Parallel beam UV meter. The parallel beam apparatus, designed for precise UV254 experiments, comprises UV254 lamp, shutter, collimator tube, washer, beaker, magnetic stirrer, and lifter (23).

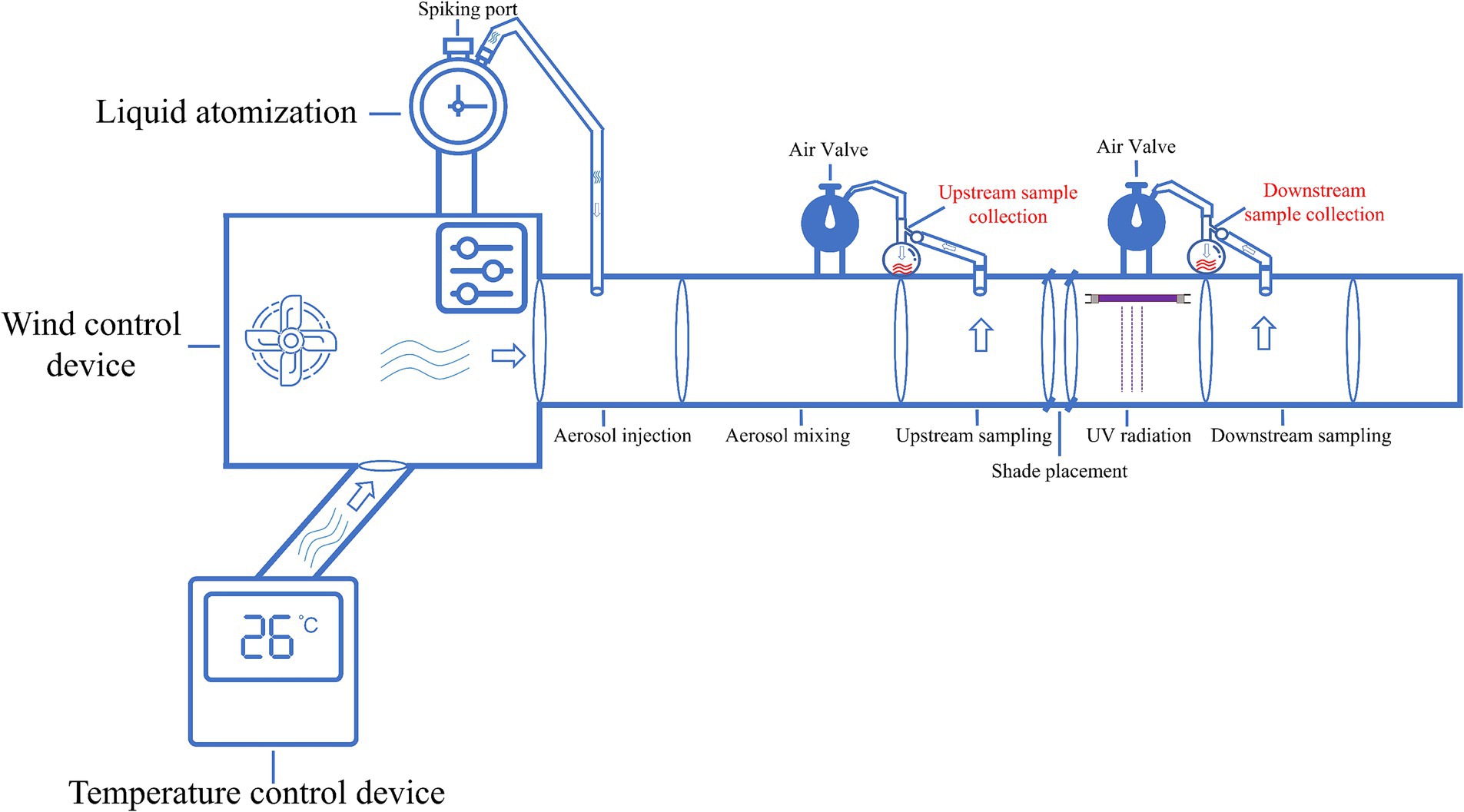

As shown in Figure 2, the air disinfection experiment was performed by adjusting the UV254 illumination intensity and wind speed over a fixed UV254 irradiation time. The CT values of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV stock solutions were 13.5, 12.36, and 11.01, respectively. As illustrated in Supplementary Table S2, the temperature was set to 26°C. Meanwhile, the power of the UV254 light (wavelength = 254 nm) was set to 0, 50, or 150 W; the airflow rates in the air sampler and wind tunnel were set to 1 m/s and 2 m/s, respectively, based on the required UV dose. As shown in Figure 3, the corresponding UV254 dose was set to 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 6 mJ/cm2 based on the simulation. First, the air sampler was used to collect airborne particles containing viruses upstream of the sampling section 30 s after nebulization. Subsequently, similar particles were collected downstream. Each collection lasted 15 min to ensure sufficient capture of airborne particles containing viruses. Note that the air sampler must be replaced after each collection, and the downstream sampler should not be connected while the upstream sampler is in operation. The air collected before and after UV254 irradiation was dissolved into the culture medium, and viral inactivation was determined by assessing CPEs and performing IFAs. The end of the ventilation duct was equipped with an exhaust gas treatment unit to inhibit the release of viruses into the environment. Three replications of each experiment were performed.

Figure 2. Equipment for air sterilization in a duct. The air disinfection equipment contained a temperature regulation device, wind speed controller, nebulizer (with liquid gasification function), air sampler (with gas liquefaction function), UV254 device, and ventilation duct to simulate UV254 disinfection of the air (50).

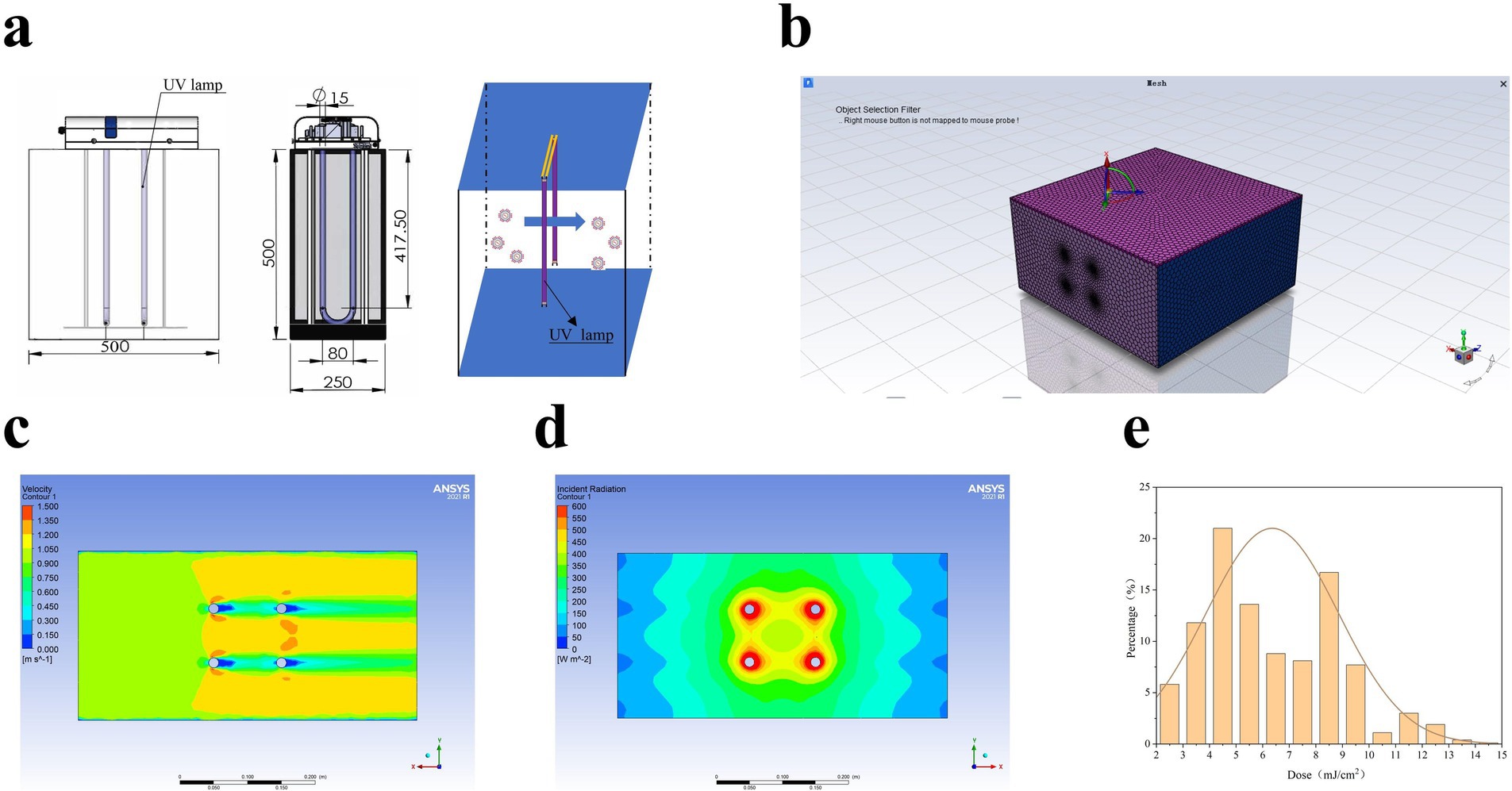

Figure 3. Duct calculation method. (A) UV254 sterilization equipment. The equipment included a closed pipeline disinfection chamber with a cross-section of 500 × 250 mm2 and a total length of 500 mm. Two built-in power sources (75 W each), and Kewei brand U-shaped low-pressure, high-intensity UV light (100 mm apart) with a UVC efficiency of 32% placed perpendicular to the wind direction. (B) Grid schematic. The structured grid shown in the figure was used to divide the sterilized area for simulation. A total of 288,738 grid cells were applied in the study. (C) Velocity field distribution. With an inlet wind speed of 1 m/s, the internal velocity field exhibited an axisymmetric distribution. Due to the bypassing effect of the lamps, the minimum velocity appeared in the downstream region of the light. However, the velocity variation across the flow field was minimal, resulting in a relatively uniform particle residence time in the range of 0.4–0.6 s. (D) Radiation intensity distribution. The distribution of internal radiation intensity indicated that the highest intensity occurred near the lamps, gradually decreasing along the radial direction from the light surface. (E) UV254 dose distribution. The radiation dose of particles flowing through the UV254 disinfection equipment is shown in figure. Based on the DPM model, 1,000 particles were injected simultaneously, and statistical analysis calculated the effective dose of the model as 6.086 mJ/cm2.

After treatment, nucleic acids were extracted from ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV using RaPure Viral RNA/DNA Kit (Guangzhou, China) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and qPCR was performed using the reaction system and procedure described previously (24–26). Three assays were performed for each sample. Regarding the results, negative samples had no CT values, positive samples had CT values of ≤34.0 with typical amplification curves, and suspicious samples had CT values of >34.0 with typical amplification curves. If two samples were considered suspicious, the result of the third sample was used.

The impact of UV254 light on pathogenic microorganisms is determined by the UV254 dose they receive. The UV254 is defined as (27):

The UV254 radiation dose received by a pathogenic microorganism in the reactor is determined by its path and exposure time. The relationship between microbial inactivation efficiency and UV254 dose is defined as (29):

ASFV samples treated with different UV254 doses were used to infect PAMs. Similarly, treated PRRSV samples were used to infect Marc-145 cells, and treated PEDV samples were used to infect Vero cells. Virus infectivity was determined by assessing CPEs and performing IFAs. In brief, PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells were inoculated into 96-well plates, and viral suspensions (ASFV diluted in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, PRRSV diluted in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium [DMEM] containing 2% FBS, and PEDV diluted in DMEM containing 7 μg/mL trypsin) were added to the plates at a 10-fold gradient (1 × 10−1 to 1 × 10−10), with columns 1 and 12 serving as controls. Viral infectivity was confirmed via the IFA using antibodies specific for ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV, and the TCID50 was determined using the Reed and Muench method.

PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells were infected with ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV, respectively, following UV irradiation, and viral infectivity was confirmed by assessing CPEs and performing IFAs. In brief, PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells were inoculated into 96-well plates, and viral suspensions were added to the plates at a 10-fold gradient (1 × 10−1 to 1 × 10−10), with columns 1 and 12 serving as controls. Three replications of each experiment were performed. Viral fluids were collected at 6-h intervals to construct in vitro growth curves using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, United States).

The UV254 dose responses based on UVC at 254 nm were evaluated using a pseudo first-order inactivation kinetics model in the log10 scale as follows (30):

where log10 I represents the reduction in infectivity on the log10 scale; N0 and N represent the infectivity of virus samples before and after UV254 exposure, respectively; D represents the UV fluence in mJ/cm2; and k represents the pseudo first-order inactivation rate constant in cm2/mJ computed using a log10-scale kinetic model. The log10 scale inactivation rate constant was used, which facilitated the calculation of log inactivation using the rate constant.

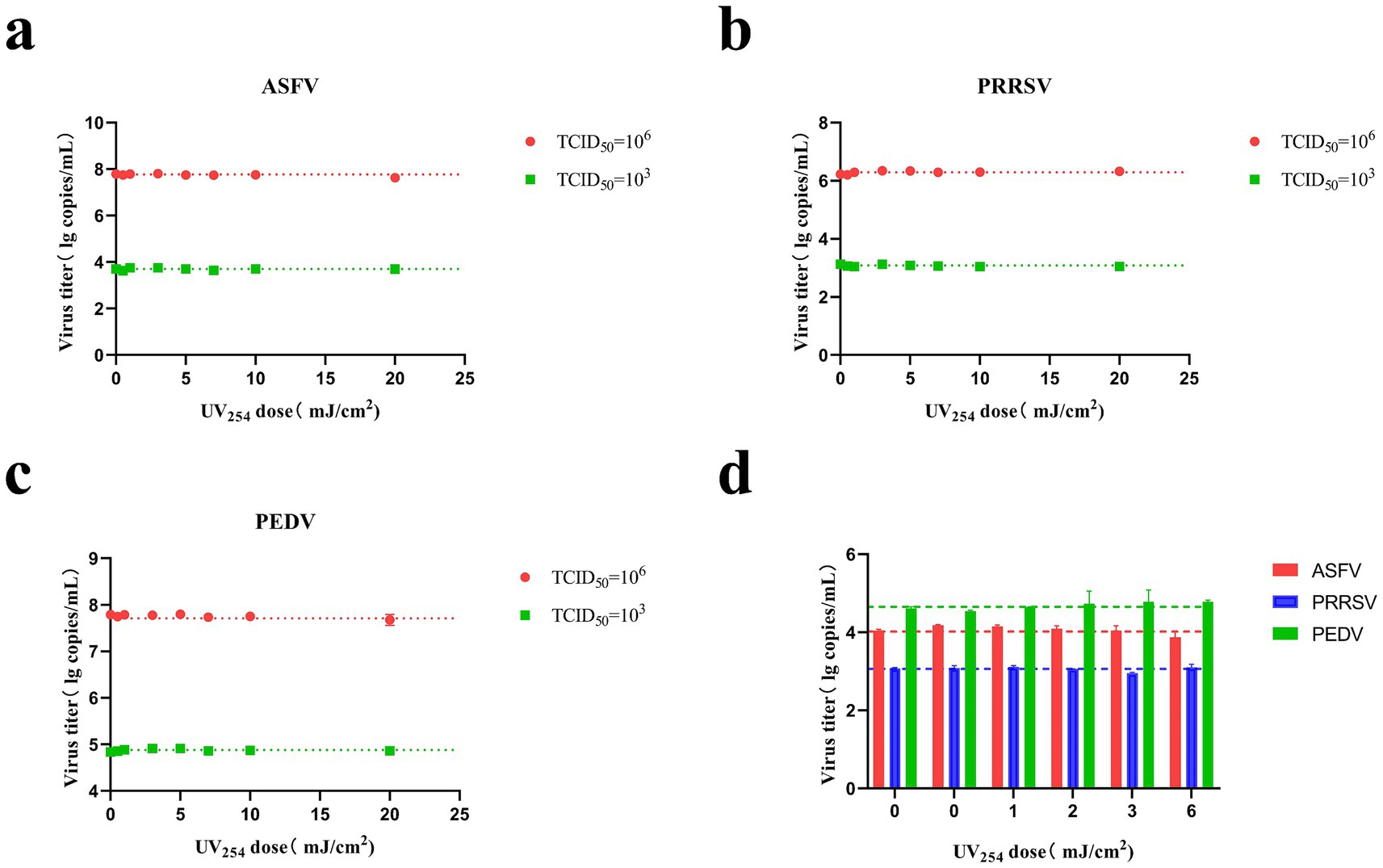

The ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV solutions were irradiated with different UV254 doses (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 20 mJ/cm2), as presented in Figures 4A–C. The copy numbers of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV did not differ significantly among the treatment groups. Further, ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV were nebulized and then irradiated with different UV254 doses (0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 mJ/cm2). As shown in Figure 4D, the copy numbers of the viruses were not altered by nebulization. This suggests that low-dose UV254 irradiation does not lead to significant nucleic acid degradation in ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV.

Figure 4. Changes in the CT values of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV after irradiation with different UV doses. (A) Irradiation of ASFV solution (TCID50 = 1 × 103 and 1 × 106) using a parallel beam UV device. (B) Irradiation of PRRSV solution (TCID50 = 1 × 103 and 1 × 106) using a parallel beam UV device. (C) Irradiation of PEDV solution (TCID50 = 1 × 103 and 1 × 106) using a parallel beam UV device. (D) Irradiation of aerosolized ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV in air disinfection ducts.

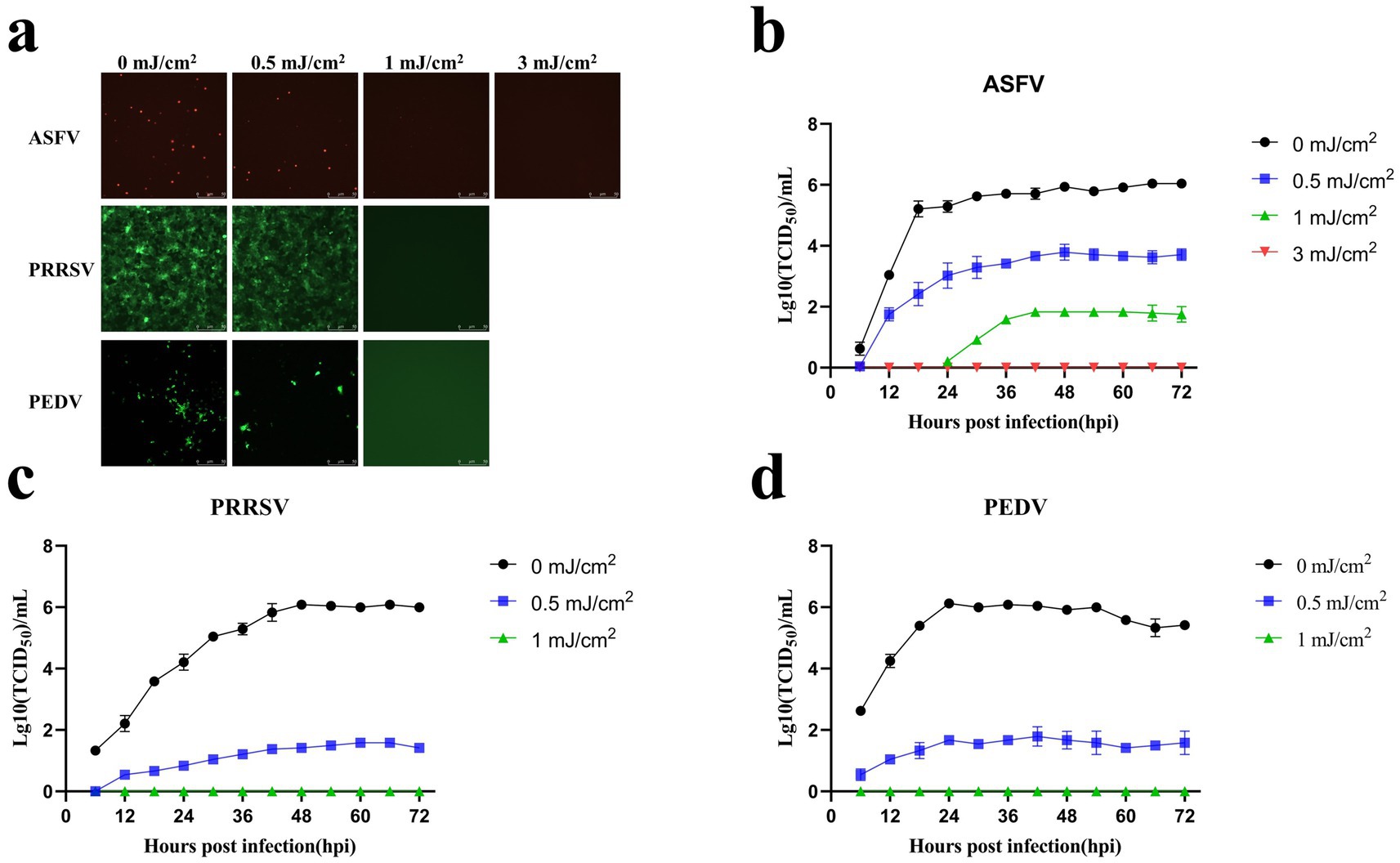

ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV (TCID50 = 1 × 106) were irradiated at different UV254 doses (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 20 mJ/cm2) and used to infect PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells, respectively. As presented in Figure 5A, the fluorescence intensity of ASFV treated with UV254 doses of 0.5 and 1 mJ/cm2 was significantly lower than that of untreated ASFV, and no fluorescence was observed for ASFV treated with an external UV254 dose of 3 mJ/cm2. The fluorescence intensity of PRRSV treated with a UV254 dose of 0.5 mJ/cm2 was significantly lower than that of untreated PRRSV, and no fluorescence was observed for PRRSV treated with an external UV254 dose of 1 mJ/cm2. The fluorescence intensity of PEDV treated with a UV254 dose of 0.5 mJ/cm2 was significantly lower than that of untreated PEDV, and no fluorescence was observed for PEDV treated with an external UV254 dose of 1 mJ/cm2. As shown in Figures 5B–D, the infectivity of the viruses decreased significantly with increasing UV254 doses, and ASFV was more resistant to UV254 irradiation than PRRSV and PEDV. These results indicated that low-dose UV254 irradiation can reduce the infectivity of viruses in cells.

Figure 5. Low-dose UV254 irradiation reduces the abundance of infectious virus in the samples. (A) Changes in the fluorescence signals of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV after treatment with different UV doses. (B) Growth curves of ASFV after treatment with different UV254 doses. (C) Growth curves of PRRSV after treatment with different UV254 doses. (D) Growth curves of PEDV after treatment with different UV254 doses.

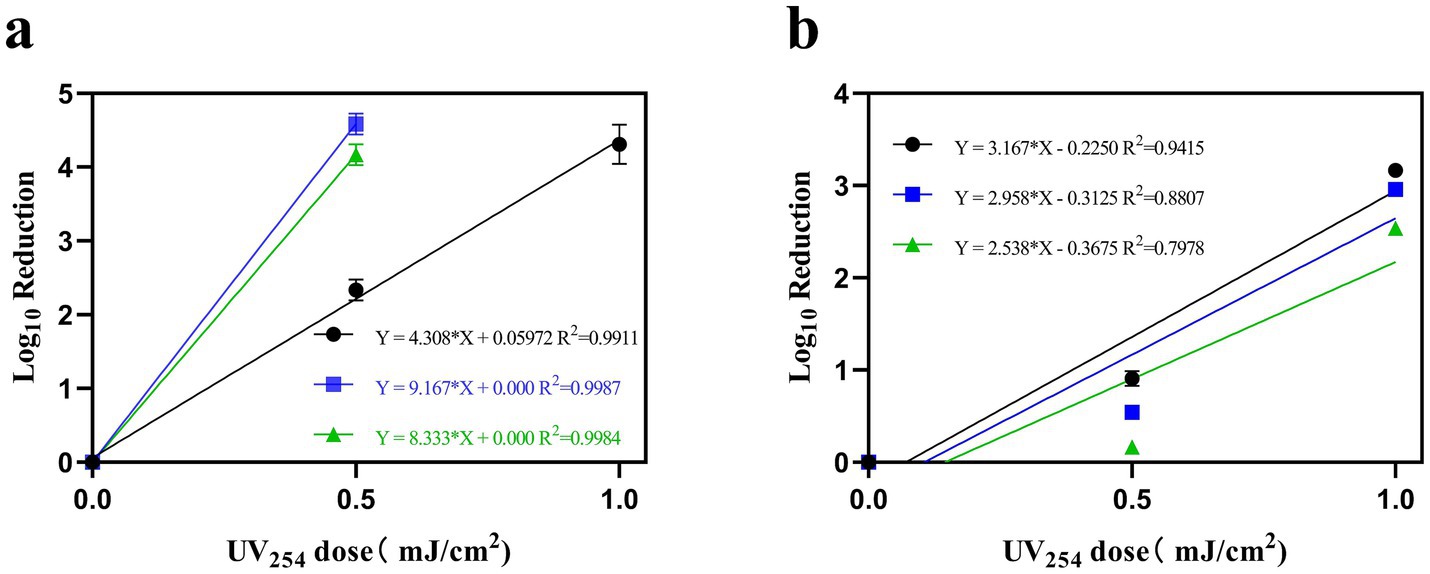

Water and air containing ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV were irradiated with different doses of UV254 and were subsequently used to infect PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells, respectively. Figure 6A, linear regression analysis revealed a rate constant of 4.308 cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 3.943–4.674) for ASFV, which corresponds to a 90% inactivation dose (D90) of 0.23 mJ/cm2. In addition, the rate constant for PRRSV was 9.167 cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 8.704–9.629), which corresponds to a D90 of 0.11 mJ/cm2. Further, the rate constant for PEDV was 8.333 cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 7.871–8.796), corresponding to a D90 of 0.12 mJ/cm2. Figure 6B, linear regression analysis revealed a rate constant of 3.167 cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 2.461–3.872) for ASFV, which corresponds to a 90% inactivation dose (D90) of 0.32 mJ/cm2. In addition, the rate constant for PRRSV was 2.958cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 1.985–3.932), which corresponds to a D90 of 0.338 mJ/cm2. Further, the rate constant for PEDV was 2.538 cm2/mJ (95% confidence interval = 1.396–3.681), corresponding to a D90 of 0.394 mJ/cm2.

Figure 6. The relationship between the inactivation of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV in water (A) and air (B) with UV254 dose, measured by TCID50 relative to untreated virus controls. (Black indicates ASFV; blue indicates PRRSV; and green indicates PEDV).

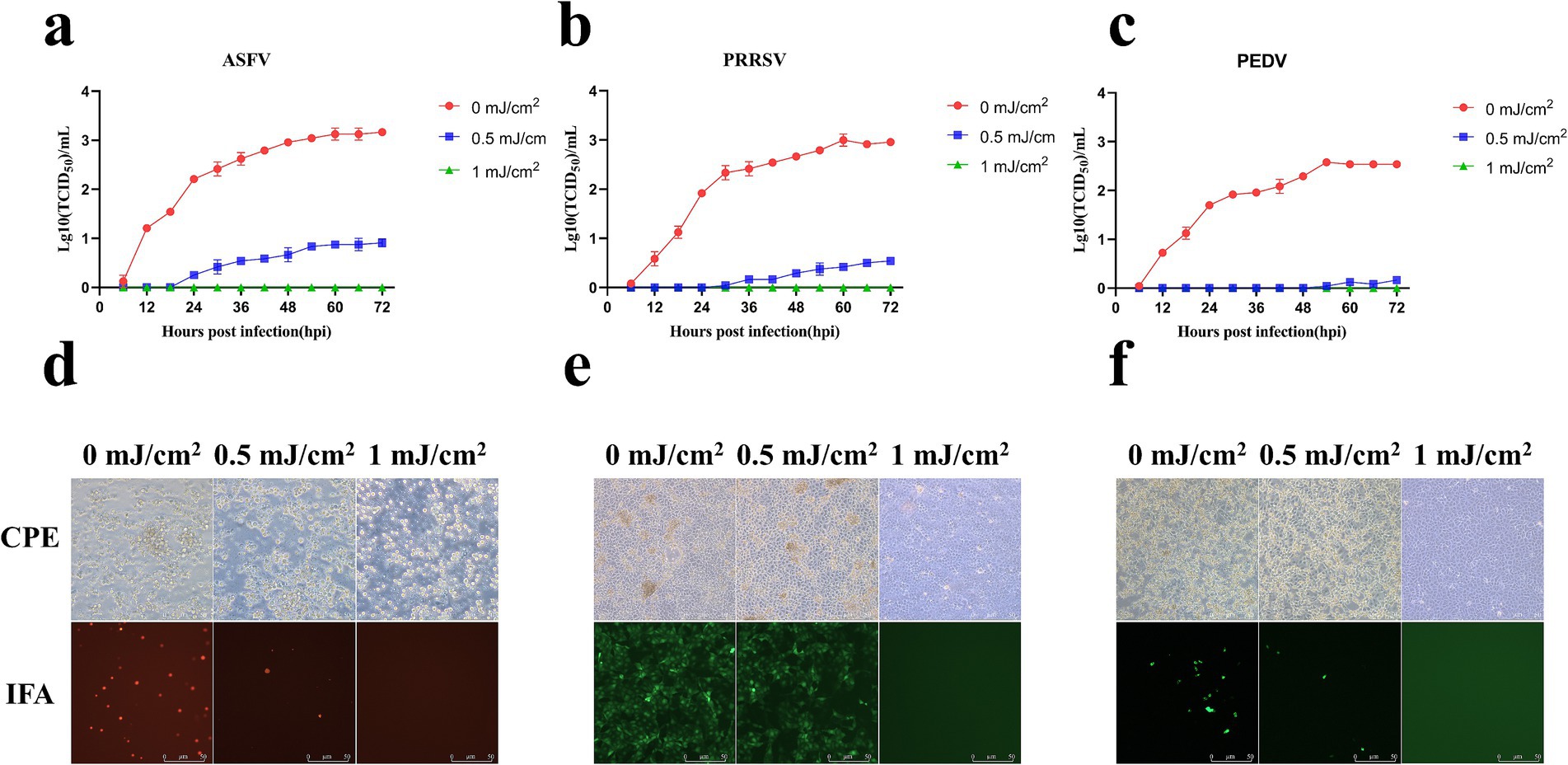

ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV were collected through an air sampler after irradiation with different UV254 doses (0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 mJ/cm2) and used to infect PAMs, Marc-145 cells, and Vero cells, respectively. As presented in Figure 7, ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV irradiated with a UV254 dose of 1 mJ/cm2 lost the ability to infect cells, whereas untreated viruses caused obvious lesions in the cells within 48 h after inoculation. The IFA and growth curves indicated that the untreated viruses showed normal replication in the cells.

Figure 7. Replication of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV after UV254 treatment at a dose of 1 mJ/cm2. (A–C) Growth curves of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV. (D–F) CPEs and IFA data for ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV.

The ASF outbreak in China in August 2018 led to major changes in pig farming patterns in China, including the introduction of biosecurity prevention and control (31, 32). Previous studies have revealed that the positivity rates of various swine diseases decreased significantly with the establishment of biosecurity prevention and control systems in Chinese pig farms (33). Disinfection is an important part of the biosafety system (34). Currently, chemical disinfection is commonly used in pig farms because of its ease of use and obvious inactivate effects against pathogenic microorganisms (35, 36). However, this disinfection method is associated with various problems, such as the presence of residual chemicals, secondary pollution, and formation of toxic disinfection by-products (DBPs). In addition, the types and usage of disinfectants applied on different objects are diverse, and some disinfectants are prone to cause damage to feed, food, and electronics. Therefore, chemical disinfection methods cannot be used in all scenarios in pig farms (37–42).

UV254 treatment is a physical disinfection method, and the use of the UVC band for UV254 irradiation leads to photochemical damage and ROS generation in pathogenic microorganisms, which affects the replication and transcription of genetic material and cause cell membrane and cell wall damage, ultimately leading to the death of microorganisms (13, 14, 27, 38, 43). Compared with chemical disinfection, UV254 disinfection is characterized by short disinfection time, high efficiency, broad germicidal spectrum, simple structure, small footprint, easy maintenance, and the absence of DBP production, resulting in its widespread use in multiple applications, such as air disinfection, water purification and wastewater treatment, food preservation, and medical applications (11, 12, 44, 45). The effectiveness of UV-mediated inactivation depends on the type of pathogenic microorganism and operating conditions, such as UV wavelength, UV intensity, and duration of irradiation. Moreover, environmental conditions can also affect the efficacy of UV-based inactivation (11, 46).

ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV are the three most serious viral diseases that can be transmitted through the air to pig farms in China. Similar to SARS-CoV-2 in humans, these viruses can cause widespread and rapid damage in infected pigs if their spread is not controlled, as observed during the ASF outbreak in China in 2018 (31, 47–49). It is well known that UV254 treatment has a strong killing effect. Currently, although UV254 disinfection is widely used in pig farms, research on its killing effects on these three viruses is less extensive than that on SARS-CoV-2. Water and air are two important media for viral transmission. In the early stage of experimental designing, we reviewed a large number of studies on the killing effects of UV254 disinfection. We revealed that UV254 treatment has a stronger effect on viruses in the air than in viruses in the water. A UV254 dose of <1 mJ/cm2 can inactivate 99.9% of SARS-CoV-2 virions, and the killing effect of UV254 is stronger in pure water than in culture medium. Compared with other wavelengths, UV254 irradiation at a wavelength of 254 nm has a stronger killing effect (31, 47–49).

We investigated the UV254 dose required to inactivate ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV in pure water using a UV254 parallel beam meter and then assessed its effects on viruses in the air using air sterilization equipment. We used primers and probes specific to ASFV-B646L, PRRSV-ORF6, and PEDV-M genes to detect the viral nucleic acid abundance of ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV, respectively, before and after irradiation with different UV254 doses (parallel beam UV254 system: 0–20 mJ/cm2; air sterilization duct: 0–6 mJ/cm2). Further, we assessed viral infectivity by measuring CPEs and performing IFAs. The results revealed that low-dose UV254 irradiation did not significantly degrade viral nucleic acids or suppress viral infectivity. In addition, ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV treated with UV254 doses of 3, 1, and 1 mJ/cm2, respectively, these viral fluids were found to be infectivity-incompetent. To more intuitively demonstrate the relationship of the UV254 dose with ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV inactivation, the inactivation rate was quantified as the ratio of TCID50 before and after UV irradiation. ASFV was more resistant to UV254 irradiation than PRRSV and PEDV, probably because ASFV consists of a four-layered protein shell and an internal genome, which is apparently more complex in structure than the internal genomes of PRRSV and PEDV. The air sterilization experiment revealed good cell growth, no cell lesions, and no fluorescence in the 1 mJ/cm2 treatment group, suggesting that this dose is sufficient to inactivate ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV. The stronger killing effects of UV254 in the air than in the water are likely attributable to the fact that UV254 can directly contact viruses in the air, whereas water refracts UV254 light. This experiment was performed under ideal conditions where in UV254 irradiation was applied directly to the viruses, resulting in killing effects at low doses. In real-word situations, the environment is intricate, and the number and size of dust particles in water and air can affect the efficiency of UV254 disinfection. Therefore, it may be necessary to increase the UV dose in practical applications. In summary, we believe that UV254 disinfection can be used in air filtration devices and other joint applications to detoxify air.

This study revealed that low-dose (0–20 mJ/cm2) UV254 irradiation significantly reduces viral infectivity without causing nucleic acid degradation. Using parallel beam UV254 apparatus, the UV254 doses required to inactivate ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV were preliminarily determined to be 3, 1, and 1 mJ/cm2, respectively. The air disinfection experiment illustrated that a UV254 dose of 1 mJ/cm2 was sufficient to eradicate ASFV, PRRSV, and PEDV. These findings may provide a reference for the design and application of UV254 equipment in pig farms and lay a foundation for further research and development regarding viral disinfection.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YQ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Software. QL: Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HC: Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. QG: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Formal analysis, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. GZ: Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. LW: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1800100), the Start-Up Research Project of Maoming Laboratory (2021TDQD002), and the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-35), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20230860).

The authors thank Qi Gao, HeYou Yi, and Yu Wu for providing qPCR primers and probes.

JW was employed by Foshan Comwin Light & Electricity Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1512387/full#supplementary-material

1. Tong, B, Zhang, L, Hou, Y, Oenema, O, Long, W, Velthof, G, et al. Lower pork consumption and technological change in feed production can reduce the pork supply chain environmental footprint in China. Nat Food. (2023) 4:74–83. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00640-6

2. Gaudreault, NN, Madden, DW, Wilson, WC, Trujillo, JD, and Richt, JA. African swine fever virus: an emerging DNA arbovirus. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:215. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00215

3. VanderWaal, K, and Deen, J. Global trends in infectious diseases of swine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:11495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806068115

4. Yang, H, and Zhou, L. Epidemic situation of swine diseases in 2022 and trends and prevention strategies for 2023. Swine Ind Sci. (2023) 40:58–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5358.2023.02.018

5. Blome, S, Franzke, K, and Beer, M. African swine fever—a review of current knowledge. Virus Res. (2020) 287:198099. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198099

6. Guinat, C, Gogin, A, Blome, S, Keil, G, Pollin, R, Pfeiffer, DU, et al. Transmission routes of African swine fever virus to domestic pigs: current knowledge and future research directions. Vet Rec. (2016) 178:262–7. doi: 10.1136/vr.103593

7. Olesen, AS, Lohse, L, Boklund, A, Halasa, T, Gallardo, C, Pejsak, Z, et al. Transmission of African swine fever virus from infected pigs by direct contact and aerosol routes. Vet Microbiol. (2017) 211:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.10.004

8. Arruda, AG, Tousignant, S, Sanhueza, J, Vilalta, C, Poljak, Z, Torremorell, M, et al. Aerosol detection and transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): what is the evidence, and what are the knowledge gaps? Viruses. (2019) 11:712. doi: 10.3390/v11080712

9. Alonso, C, Goede, DP, Morrison, RB, Davies, PR, Rovira, A, Marthaler, DG, et al. Evidence of infectivity of airborne porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and detection of airborne viral RNA at long distances from infected herds. Vet Res. (2014) 45:73. doi: 10.1186/s13567-014-0073-z

10. Li, X, Hu, Z, Fan, M, Tian, X, Wu, W, Gao, W, et al. Evidence of aerosol transmission of African swine fever virus between two piggeries under field conditions: a case study. Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:1201503. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1201503

11. Li, X, Cai, M, Wang, L, Niu, F, Yang, D, and Zhang, G. Evaluation survey of microbial disinfection methods in UV-LED water treatment systems. Sci Total Environ. (2019) 659:1415–27. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.344

12. Bono, N, Ponti, F, Punta, C, and Candiani, G. Effect of UV irradiation and TiO2-photocatalysis on airborne bacteria and viruses: an overview. Materials. (2021) 14:1075. doi: 10.3390/ma14051075

13. Song, K, Taghipour, F, and Mohseni, M. Microorganisms inactivation by wavelength combinations of ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (UV-LEDs). Sci Total Environ. (2019) 665:1103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.041

14. Martin-Somer, M, Pablos, C, Adan, C, van Grieken, R, and Marugan, J. A review on LED technology in water photodisinfection. Sci Total Environ. (2023) 885:163963. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163963

15. Misstear, DB, and Gill, LW. The inactivation of phages MS2, ΦX174 and PR772 using UV and solar photocatalysis. J Photochem Photobiol B. (2012) 107:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.10.012

16. Hull, NM, and Linden, KG. Synergy of MS2 disinfection by sequential exposure to tailored UV wavelengths. Water Res. (2018) 143:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.017

17. Darnell, ME, Subbarao, K, Feinstone, SM, and Taylor, DR. Inactivation of the coronavirus that induces severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV. J Virol Methods. (2004) 121:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.006

18. Heffron, J, Bork, M, Mayer, BK, and Skwor, T. A comparison of porphyrin photosensitizers in photodynamic inactivation of RNA and DNA bacteriophages. Viruses. (2021) 13:530. doi: 10.3390/v13030530

19. Spunde, K, Rudevica, Z, Korotkaja, K, Skudra, A, Gudermanis, R, Zajakina, A, et al. Bacteria and RNA virus inactivation with a high-irradiance UV-A source. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2024) 23:1841–56. doi: 10.1007/s43630-024-00634-2

20. Freitas, BLS, Fava, NMDN, Melo-Neto, MGD, Dalkiranis, GG, Tonetti, AL, Byrne, JA, et al. Efficacy of UVC-LED radiation in bacterial, viral, and protozoan inactivation: an assessment of the influence of exposure doses and water quality. Water Res. (2024) 266:122322. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.122322

21. Jing, Z, Wang, W, Nong, Y, Peng, L, Yang, Z, Ye, B, et al. Suppression of photoreactivation of E. coli by excimer far-UV light (222 nm) via damage to multiple targets. Water Res. (2024) 255:121533. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121533

22. Yu, M, Gao, R, Lv, X, Sui, M, and Li, T. Inactivation of phage phiX174 by UV254 and free chlorine: structure impairment and function loss. J Environ Manage. (2023) 340:117962. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117962

23. Qiang, Z, Li, W, Li, M, Bolton, JR, and Qu, J. Inspection of feasible calibration conditions for UV radiometer detectors with the KI/KIO3 actinometer. Photochem Photobiol. (2015) 91:68–73. doi: 10.1111/php.12356

24. Gao, Q, Feng, Y, Yang, Y, Luo, Y, Gong, T, Wang, H, et al. Establishment of a dual real-time PCR assay for the identification of African swine fever virus genotypes I and II in China. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:882824. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.882824

25. Yi, H, Yu, Z, Wang, Q, Sun, Y, Peng, J, Cai, Y, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins suppress type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication in vitro and enhance the immune effect of the live vaccine JXA1-R in piglets. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:886058. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.886058

26. Wu, Y, Li, W, Zhou, Q, Li, Q, Xu, Z, Shen, H, et al. Characterization and pathogenicity of Vero cell-attenuated porcine epidemic diarrhea virus CT strain. Virol J. (2019) 16:121. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1232-7

27. Han, X. Design and process parameter optimization of ultraviolet disinfection devices. Changchun: Jilin Agricultural University (2006).

28. Freeman, S, Kibler, K, Lipsky, Z, Jin, S, German, GK, and Ye, K. Systematic evaluating and modeling of SARS-CoV-2 UVC disinfection. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:5869. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-09930-2

29. Welch, D, Buonanno, M, Buchan, AG, Yang, L, Atkinson, KD, Shuryak, I, et al. Inactivation rates for airborne human coronavirus by low doses of 222 nm far-UVC radiation. Viruses. (2022) 14:684. doi: 10.3390/v14040684

30. Ma, B, Gundy, PM, Gerba, CP, Sobsey, MD, and Linden, KG. UV inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 across the UVC spectrum: KrCl* excimer, mercury-vapor, and light-emitting-diode (LED) sources. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2021) 87:e0153221. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01532-21

31. Gao, L, Sun, X, Yang, H, Xu, Q, Li, J, Kang, J, et al. Epidemic situation and control measures of African swine fever outbreaks in China 2018–2020. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2021) 68:2676–86. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13968

32. Chen, H, Liu, X, and Li, C. Epidemiological characteristics and prevention and control of major swine diseases in China. Swine Ind Today. (2022) 2:8–15.

33. Wang, Y, Song, D, Zhao, M, Yan, R, and Ban, F. Exploring new strategies for swine disease prevention and control based on the detection of swine diseases before and after the outbreak of African swine fever. Mod Anim Husb. (2022) 6:41–5.

34. Liu, Y, Zhang, X, Qi, W, Yang, Y, Liu, Z, An, T, et al. Prevention and control strategies of African swine fever and progress on pig farm repopulation in China. Viruses. (2021) 13:2552. doi: 10.3390/v13122552

35. Beato, MS, D’Errico, F, Iscaro, C, Petrini, S, Giammarioli, M, and Feliziani, F. Disinfectants against African swine fever: an updated review. Viruses. (2022) 14:1384. doi: 10.3390/v14071384

36. Ni, Z, Chen, L, Yun, T, Xie, R, Ye, W, Hua, J, et al. Inactivation performance of pseudorabies virus as African swine fever virus surrogate by four commercialized disinfectants. Vaccines. (2023) 11:579. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11030579

37. Sun, X, Chen, M, Wei, D, and Du, Y. Research progress of disinfection and disinfection by-products in China. J Environ Sci. (2019) 81:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.02.003

38. Zhao, C, Fan, S, Du, X, Deng, Q, and Liu, C. Research progress on ultraviolet disinfection technology in pig farms. China Anim Health Insp. (2021) 38:88–94. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005

39. Leclercq, L, and Nardello-Rataj, V. How to improve the chemical disinfection of contaminated surfaces by viruses, bacteria and fungus? Eur J Pharm Sci. (2020) 155:105559. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105559

40. Farre, MJ, Day, S, Neale, PA, Stalter, D, Tang, JY, and Escher, BI. Bioanalytical and chemical assessment of the disinfection by-product formation potential: role of organic matter. Water Res. (2013) 47:5409–21. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.017

41. Deleo, PC, Huynh, C, Pattanayek, M, Schmid, KC, and Pechacek, N. Assessment of ecological hazards and environmental fate of disinfectant quaternary ammonium compounds. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2020) 206:111116. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111116

42. Qin, J, Xia, PF, Yuan, XZ, and Wang, SG. Chlorine disinfection elevates the toxicity of polystyrene microplastics to human cells by inducing mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. J Hazard Mater. (2022) 425:127842. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127842

43. Besaratinia, A, Yoon, JI, Schroeder, C, Bradforth, SE, Cockburn, M, and Pfeifer, GP. Wavelength dependence of ultraviolet radiation-induced DNA damage as determined by laser irradiation suggests that cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are the principal DNA lesions produced by terrestrial sunlight. FASEB J. (2011) 25:3079–91. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187336

44. Kebbi, Y, Muhammad, AI, Sant'Ana, AS, Do, PL, Liu, D, and Ding, T. Recent advances on the application of UV-LED technology for microbial inactivation: progress and mechanism. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. (2020) 19:3501–27. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12645

45. Song, K, Mohseni, M, and Taghipour, F. Application of ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (UV-LEDs) for water disinfection: a review. Water Res. (2016) 94:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.003

46. Laghari, AA, Liu, L, Kalhoro, DH, Chen, H, and Wang, C. Mechanism for reducing the horizontal transfer risk of the airborne antibiotic-resistant genes of Escherichia coli species through microwave or UV irradiation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:4332. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074332

47. Synowiec, A, Szczepanski, A, Barreto-Duran, E, Lie, LK, and Pyrc, K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): a systemic infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2021) 34:e00133. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00133-20

48. Du, T, Nan, Y, Xiao, S, Zhao, Q, and Zhou, EM. Antiviral strategies against PRRSV infection. Trends Microbiol. (2017) 25:968–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.06.001

49. Zhang, H, Zou, C, Peng, O, Ashraf, U, Xu, Q, Gong, L, et al. Global dynamics of porcine enteric coronavirus PEDV epidemiology, evolution, and transmission. Mol Biol Evol. (2023) 40:msad052. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msad052

50. Wang, Y ed. Research on dynamic ultraviolet irradiation air disinfection technology in air ducts. Tianjin: Tianjin University (2012).

51. Beck, SE, Rodriguez, RA, Linden, KG, Hargy, TM, Larason, TC, and Wright, HB. Wavelength dependent UV inactivation and DNA damage of adenovirus as measured by cell culture infectivity and long range quantitative PCR. Environ Sci Technol. (2014) 48:591–8. doi: 10.1021/es403850b

52. Welch, D, Buonanno, M, Grilj, V, Shuryak, I, Crickmore, C, Bigelow, AW, et al. Far-UVC light: a new tool to control the spread of airborne-mediated microbial diseases. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:2752. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21058-w

53. Ruetalo, N, Berger, S, Niessner, J, and Schindler, M. Inactivation of aerosolized SARS-CoV-2 by 254 nm UV-C irradiation. Indoor Air. (2022) 32:e13115. doi: 10.1111/ina.13115

54. Buonanno, M, Welch, D, Shuryak, I, and Brenner, DJ. Far-UVC light (222 nm) efficiently and safely inactivates airborne human coronaviruses. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10285. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67211-2

55. Heilingloh, CS, Aufderhorst, UW, Schipper, L, Dittmer, U, Witzke, O, Yang, D, et al. Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 to UV irradiation. Am J Infect Control. (2020) 48:1273–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.031

56. Gidari, A, Sabbatini, S, Bastianelli, S, Pierucci, S, Busti, C, Bartolini, D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 survival on surfaces and the effect of UV-C light. Viruses. (2021) 13:408. doi: 10.3390/v13030408

57. Biasin, M, Bianco, A, Pareschi, G, Cavalleri, A, Cavatorta, C, Fenizia, C, et al. UV-C irradiation is highly effective in inactivating SARS-CoV-2 replication. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:6260. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85425-w

58. Lo, CW, Matsuura, R, Iimura, K, Wada, S, Shinjo, A, Benno, Y, et al. UVC disinfects SARS-CoV-2 by induction of viral genome damage without apparent effects on viral morphology and proteins. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:13804. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93231-7

59. Garg, H, Ringe, RP, Das, S, Parkash, S, Thakur, B, Delipan, R, et al. UVC-based air disinfection systems for rapid inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 present in the air. Pathogens. (2023) 12:419. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12030419

60. Schuit, MA, Larason, TC, Krause, ML, Green, BM, Holland, BP, Wood, SP, et al. SARS-CoV-2 inactivation by ultraviolet radiation and visible light is dependent on wavelength and sample matrix. J Photochem Photobiol B. (2022) 233:112503. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2022.112503

61. Kitagawa, H, Nomura, T, Nazmul, T, Kawano, R, Omori, K, Shigemoto, N, et al. Effect of intermittent irradiation and fluence-response of 222 nm ultraviolet light on SARS-CoV-2 contamination. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. (2021) 33:102184. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102184

62. Maquart, M, and Marlet, J. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 inactivation by mercury and led UV-C lamps on different surfaces. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2022) 21:2243–7. doi: 10.1007/s43630-022-00292-2

63. Storm, N, Mckay, L, Downs, SN, Johnson, RI, Birru, D, de Samber, M, et al. Rapid and complete inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by ultraviolet-C irradiation. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:22421. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79600-8

Keywords: UV radiation, air disinfection, ASFV, PRRSV, PEDV

Citation: Qiu Y, Li Q, Zhao W, Chang H, Wang J, Gao Q, Zhou Q, Zhang G, Gong L and Wang L (2025) Evaluation of the killing effects of UV254 light on common airborne porcine viruses. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1512387. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1512387

Received: 16 October 2024; Accepted: 09 January 2025;

Published: 31 January 2025.

Edited by:

Joel Fernando Soares Filipe, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Lan Wang, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Qiu, Li, Zhao, Chang, Wang, Gao, Zhou, Zhang, Gong and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: LianXiang Wang, YW5pbXNjaUAxMjYuY29t; Lang Gong, Z29uZ2xhbmdAc2NhdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.