- 1Henan International Joint Laboratory of Nutrition Regulation and Ecological Raising of Domestic Animal, College of Animal Science and Technology, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China

- 2Department of Economic Management and Animal Husbandry, Ruzhou Vocational and Technical College, Pingdingshan, China

Mastitis is one of the most common diseases in dairy farms. During the perinatal period, the bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs) of High-yielding dairy cows accelerate metabolism and produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It is one of the primary causes of mastitis and will lead to the breakdown of redox balance, which will induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Baicalin is a flavonoid substance extracted from the root of natural plant Scutellaria baicalensis, which has anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-viral and other biological functions. In this research, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used to construct a mastitis oxidative stress model, and relevant mechanisms were analyzed by immunofluorescence techniques, qRT-PCR and Western Blot to explore how baicalin affects BMECs' oxidative stress and inflammation caused by H2O2, as well as to provide new perspectives on the combined application of baicalin in the prevention and treatment of mastitis. The results demonstrated that baicalin treatment could reduce the accumulation of H2O2-induced intracellular ROS and decrease the expression of inflammatory cytokines Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and the apoptosis rate. The inhibitory effect of baicalin on H2O2-induced intracellular ROS accumulation and the expression of inflammatory cytokines and apoptotic factors in BMECs was blocked by pretreatment with the Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) inhibitor retinoic acid (RA) prior to H2O2 and/or baicalin treatment. In summary, baicalin could served as a natural antioxidant agent to regulate cell apoptosis through its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects to combat BMECs damage caused by H2O2.

Introduction

Mastitis is one of the main diseases in dairy cows, which not only affects their health but also reduces milk production and quality. Especially during the perinatal period and peak lactation period, the extensive synthesis of breast milk raises the energy requirements of breast tissue. When the synthesis rate of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is greater than the removal rate of antioxidants, this will cause excessive accumulation of ROS in the body, destroying cell membrane structure and resulting in oxidative stress (1, 2). The excessive accumulation of ROS could also destroy the dynamic balance of the antioxidant defense system, induce cell apoptosis, and increase the incidence of mastitis (3). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is an inorganic oxide. Numerous studies have demonstrated that H2O2 could induce the overproduction of ROS and initiate oxidative stress through a feedback system involving intricate physiological processes, such as apoptosis and autophagy, and H2O2-treated BMECs could more accurately simulate the actual state of oxidative damage and mastitis in dairy cows, with stable properties (4–6). Therefore, the H2O2 was used in the current study to construct an oxidative stress model, providing a basis for investigating the potential mechanism and effective intervention measures of cell apoptosis.

The bovine mammary gland epithelial cells (BMECs) are the primary cellular components of the cow mammary gland, not only synthesizing and secreting milk but also playing an important role in the innate immunity of the gland (7). Metabolic activity is enhanced during lactation, and BMECs are highly susceptible to oxidative stress in breast tissue (8). Therefore, it is becoming increasingly important to take measures to reduce oxidative stress damage to BMECs in dairy cows. The nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a major transcriptional protein regulating oxidative damage. When cells are under oxidative stress, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1, transported to the nucleus to bind to ARE, activating the expression of downstream antioxidant genes, such as quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) (9, 10). An essential inflammatory signaling pathway, activation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), could increase the synthesis of pro-inflammatory proteins such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-β). It has been reported that Nrf2 activation reduces the incidence of inflammatory reactions by inhibiting the expression of IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) phosphorylation and the NF-κB pathway. However, this effect is eliminated when Nrf2 and HO-1 are inhibited, indicating that Nrf2 signaling plays an indispensable role in NF-κB-mediated inflammation (11, 12). In addition, excessive ROS can cause irreversible cell damage, such as degradation of cell structure and components, as well as DNA damage, leading to cell apoptosis. In addition, excessive ROS could cause irreversible cellular damage, such as degradation of cell structure and components and DNA damage, which leads to apoptosis (13). Therefore, alleviation of oxidative stress is crucial to inhibit inflammation and apoptosis in BMECs, and Nrf2 might be a potential therapeutic target for the reduction of oxidative stress.

Baicalin is one of the flavonoids extracted from the dried root of the herb Scutellaria baicalensis, exhibiting antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-tumor properties. Numerous studies have demonstrated that baicalin could reduce malondialdehyde (MDA) content and increase the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) through the Nrf2 pathway, thereby exerting antioxidant effects (14, 15). By suppressing NF-κB and its downstream inflammatory cytokines, as well as the caspase3 signaling pathways, baicalin could reduce oxidative stress by scavenging ROS and controlling inflammation and apoptosis (16, 17). However, there is still a lack of in-depth systematic studies on whether the effects of baicalin on inflammation and apoptosis are mediated by oxidative stress and whether the above changes also occur in BMECs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effect and mechanism of baicalin on H2O2-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis of BMECs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The BMECs were obtained from the Physiological and Biochemical Laboratory of Henan Agricultural University and retained the characteristics and functions of the primary cells. Add 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, New York, USA) at 37°C and culture using 5% CO2 and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B sterile solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China). After 48 h of initial culture, the cells were cleaned with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; BI, Israel) and the culture medium was removed. Then, the cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (Gibco, New York, USA) for 3 min and stop digestion by adding DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS. Centrifuge the cells for 4 min, then reculture in the medium and incubate at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The cells were used for follow-up experiments when the cell coverage reached 80%.

Sample treatment

Baicalin (C21H18O11, purity > 98%, Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, purity 3%, Merck & Co Inc, New Jersey, USA), and retinoic acid [RA, specific inhibitor of Nrf2 (Proteintech, Chicago, IL), Med Chem Express, New Jersey, USA] were stored at room temperature. Baicalin was fully dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Solarbio, Beijing, China) to the final concentration of 500 μM and stored at 4°C protected from light. Four experimental groups were set up in order to investigate whether reducing oxidative stress could decrease the inflammatory response, including control group (CON, untreated), H2O2 treatment group (H2O2), baicalin treatment group (baicalin) and baicalin with H2O2 group (baicalin +H2O2), baicalin and H2O2 group cells were finally treated with 10 and 200 μM for 18 and 6 h, and baicalin with H2O2 group cells were pretreated with 10 μM dose for 18 h. Then, the cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h. The baicalin solution was diluted with cell culture medium to 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM for 12, 24, and 48 h to explore the alleviating effect of baicalin concentration on H2O2-induced oxidative stress, respectively. The same volume of DMSO was added to the CON group, ensuring that the concentration of DMSO in all treatment solutions prepared was < 0.1% (v/v). The H2O2 was diluted with cell culture medium to concentrations of 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1,000 μM, and treat the cells for 4, 6, and 8 h, respectively. According to the results, treating cells with 10 μM baicalin for 24 h and inducing cells with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h were used as the optimal treatment conditions.

Cell viability assay

The appropriate H2O2 concentration and exposure time were screened for treating cells with Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Beijing Sun Biotechnology Co., LTD). The BMECs (2 × 105 cells/mL) were inoculated into 96-well plates, and the culture medium was discarded when the cells proliferated to the density of 70–80%. Then, 100 μL of different concentrations of baicalin and/or H2O2 solution was added to the wells and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for an appropriate time. A serum-free cell culture medium was used to wash the cells twice. Then, 100 μL 10% CCK-8 solution was added to each well. After incubation in the incubator for 2 h, the absorbance values at 450 nm were measured using an enzyme marker (BioTek Instruments, Inc, USA). Cell viability was calculated as follows: (OD of treatment group-OD of the blank group)/(OD of control group-OD of the blank group) × 100%.

ROS determination

The intracellular ROS were detected by fluorescent probe DCFH-DA staining using Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Ki (ROS Assay Kit, Shanghai Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). The cells were washed with PBS and then coincubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA in a cell incubator for 20 min. The cells were fully washed with PBS to remove DCFH-DA that had not entered the cells. Finally, the cells were resuspended in PBS and immediately visualized and imaged using fluorescence microscopy (AmScope, California, USA). After the same procedure, the fluorescence intensity at 488 nm excitation wavelength and 525 nm emission wavelength was measured using a Multifunctional Enzyme Labeler (SpectraMax i3x, Silicon Valley, USA).

Oxidative damage indicators measurement

Collecting the cells and lysing with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing 1% phosphatase inhibitor mixture (CWBIO, Beijing, China) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Epizyme, Shanghai, China). The supernatant was removed after centrifugation, and the protein concentrations of samples were determined using a BCA kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Then, the MDA content, SOD activity, and T-AOC level in the protein sample were measured according to the instructions of the Lipid MDA Assay Kit (S0131M), Total Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit (S0101S), and Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay Kit (WST-8) (Beyotime Biotechnology Co. Shanghai, China).

Quantitative real-time PCR assay

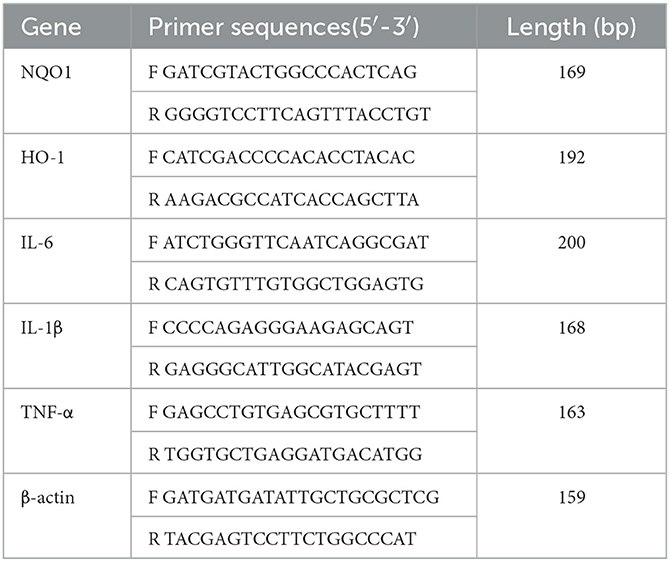

Total RNA was extracted from BMECs by TRIzol reagent (Quan-Style Gold, Beijing, China), and the quality of RNA was detected. Then, 1 μg of total RNA samples was reverse-transcribed to cDNA according to the operation instructions (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), and the relative expression of mRNA was detected using a 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The reactions were as follows: predenaturation (95°C for 30 s); cyclic reaction 40 times (95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s); melting curve (95°C for 5 s, 65°C for 5 s). Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were set up for each treatment group to determine the mean crossover point value and standard deviation (SD). The fluorescence quantification results were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method, and the results were normalized using β-actin as an internal reference gene. The primers were designed by NCBI and synthesized by Shangya Biologicals. The sequences of the synthesized primers are shown in Table 1.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from BMECs using RIPA lysis buffers containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and their concentrations were determined. The protein samples were mixed with 5 × SDS–PAGE Protein Sample Loading Buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) proportionally and then heated together in a water bath at 98°C for 5 min to denature the proteins. Separation and concentration gels were prepared according to the molecular weight requirement of the target protein, and the denatured protein samples and marker were added to the lane in turn. Subsequent to electrophoresis, the protein bands were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes according to the wet transfer method. The PVDF membranes were blocked in a shaker with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h before incubation with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day, PVDF membranes were first washed 3 times with Tris Buffered Saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 15 min each. Then, they were incubated for 1 h at room temperature using the corresponding matching fluorescent-coupled secondary antibody and washed again with TBST. The protein bands were visualized by Odyssey Infrared Imaging (LI-COR Biosciences, USA) using the Omni-ECL™ Femto Light Chemiluminescence Kit (Epizyme, Shanghai, China). The target proteins expression levels were normalized using β-actin bands as an internal control, and the protein bands were quantitatively analyzed by ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Data were collated and plotted by GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA). One-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test were used for multiple comparisons. The results are expressed as the means ± standard error (SEM) with three replicates for each treatment, and P < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

Results

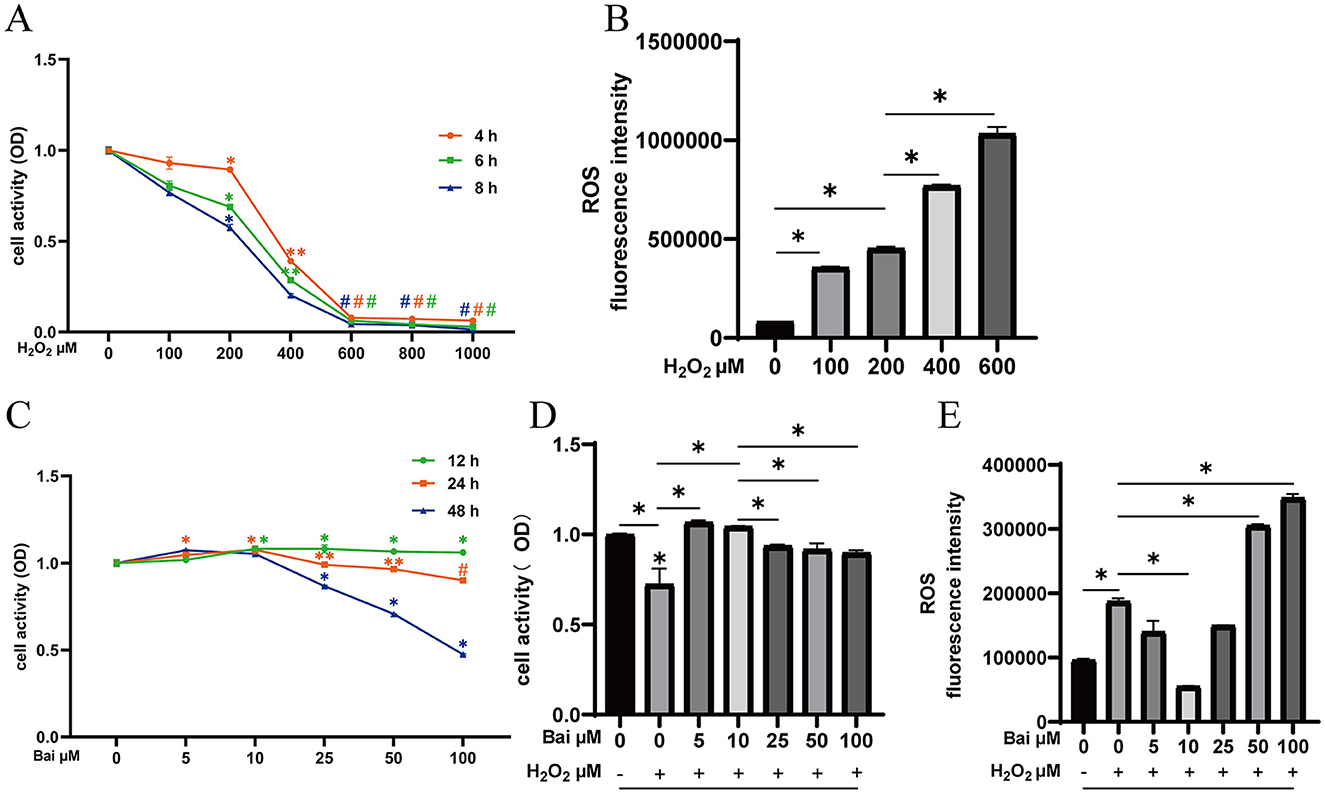

Protective effect of baicalin against H2O2-induced cell damage

Results of the protective effect of baicalin on H2O2-induced cell damage are shown in Figure 1. The cell viability of BMECs decreased to 68.9% after 6 h of stimulation with 200 μM H2O2, which the results satisfying the experimental requirements for establishing an oxidative damage model (Figure 1A). The treatment of 200 μM H2O2 significantly increased cells' ROS levels compared to the CON (P < 0.05) (Figure 1B). Different concentrations of baicalin were used to stimulate the cells for 12, 24 and 48 h, with varying effects (P < 0.05) (Figure 1C). Under the above conditions, the concentration of baicalin at 10 μM and the treatment time of 24 h could effectively inhibit H2O2-induced ROS level increase (P < 0.05) (Figures 1D, E).

Figure 1. Exploration of the optimal concentration and time of H2O2 and baicalin. (A) Effect of different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1,000 μM) on the cell viability of BMECs upon stimulation for 4, 6, and 8 h. *P < 0.05 compared with the CON, **P < 0.05 compared with the 200 μM H2O2 group, #P < 0.05 compared with the 400 μM H2O2 group. (B) Effect of different concentrations of H2O2 on ROS levels in BMECs upon stimulation for 6 h. *P < 0.05. (C) Effect of different concentrations of baicalin (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 μM) on the cell viability of BMECs upon stimulation for 12, 24 and 48 h. *P < 0.05 compared with the CON, **P < 0.05 compared with the 10 μM baicalin group, #P < 0.05 compared with the 50 μM baicalin group. (D) BMECs were treated with baicalin at different concentrations, and 200 μM H2O2 was added 6 h before the end of treatment to determine the cell viability at 24 h. *P < 0.05. (E) Effect of different concentrations of baicalin on H2O2-induced ROS levels in BMECs. *P < 0.05. The data from the CON were used to normalize the data of each treatment group. Each treatment was repeated three times, and the results are expressed as the means ± SEM.

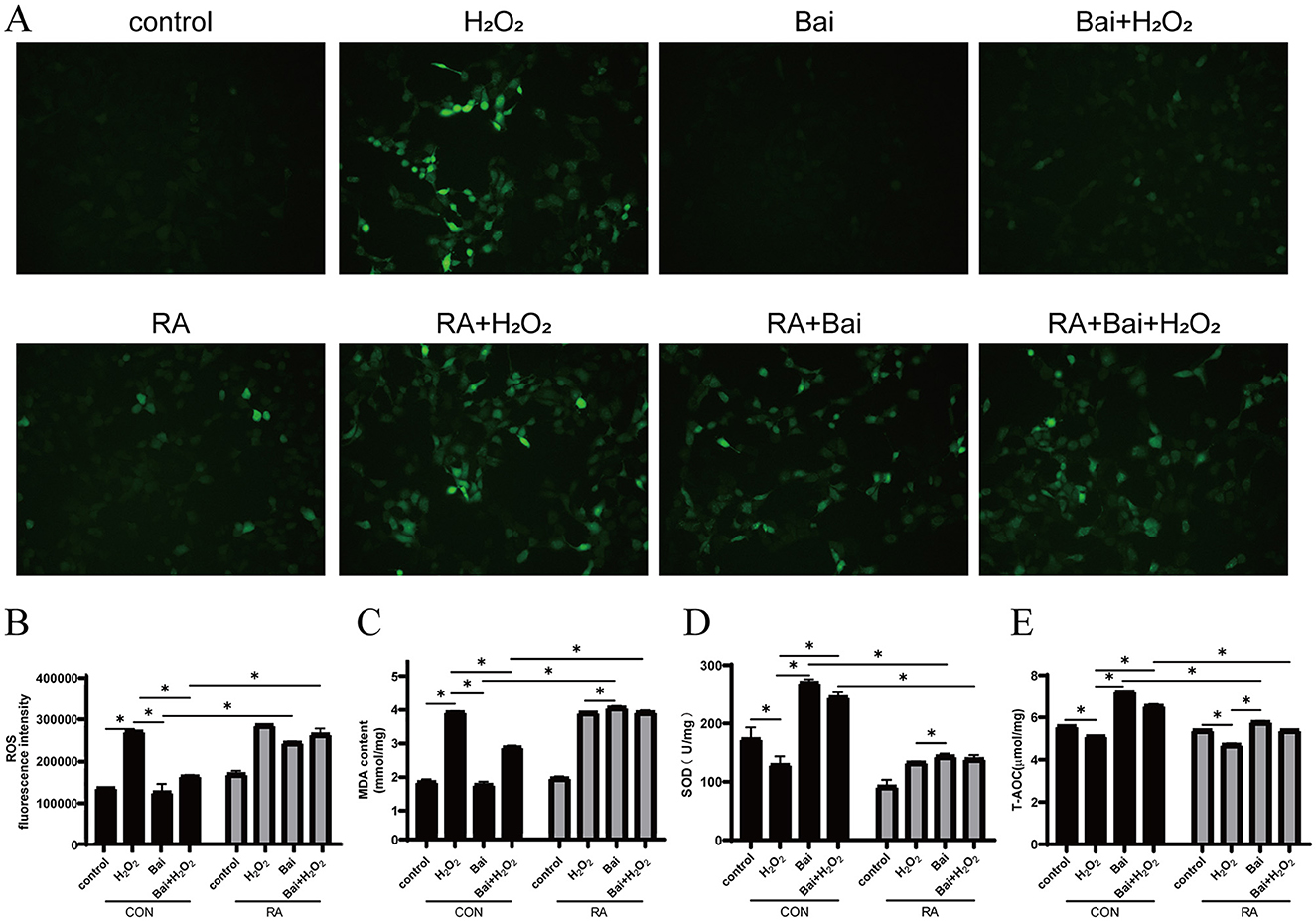

Baicalin alleviates H2O2-induced oxidative stress

Next, it explored whether the antioxidant effect of baicalin was related to Nrf2 by adding the Nrf2 inhibitor RA. As shown in Figure 2, compared with the CON group, the H2O2 treatment increased ROS levels (P < 0.05) (Figures 2A, B) and MDA content in cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 2C), decreased SOD activity (P < 0.05) (Figure 2D) and T-AOC levels (P < 0.05) (Figure 2E). Furthermore, after the addition of Nrf2-specific inhibitor RA, baicalin was unable to effectively inhibit the increase of ROS and MDA levels (P < 0.05) (Figures 2A–C), and the levels of SOD and T-AOC were significantly decreased comparison to the CON group (P < 0.05) (Figures 2D, E).

Figure 2. Effect of baicalin on H2O2-induced changes in ROS, MDA, SOD and T-AOC in BMECs. BMECs were treated with 5 μM RA for 1 h, and baicalin (10 μM) was then added for 18 h before cotreatment with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h. (A) The ROS fluorescence intensity was imaged using a fluorescence microscope (scale bar is 200 μm). (B) Changes in ROS levels in BMECs. (C) Changes in MDA content in BMECs. (D) Changes in SOD activity in BMECs. (E) Changes in T-AOC levels in BMECs. *P < 0.05. RA, Nrf2 inhibitor.

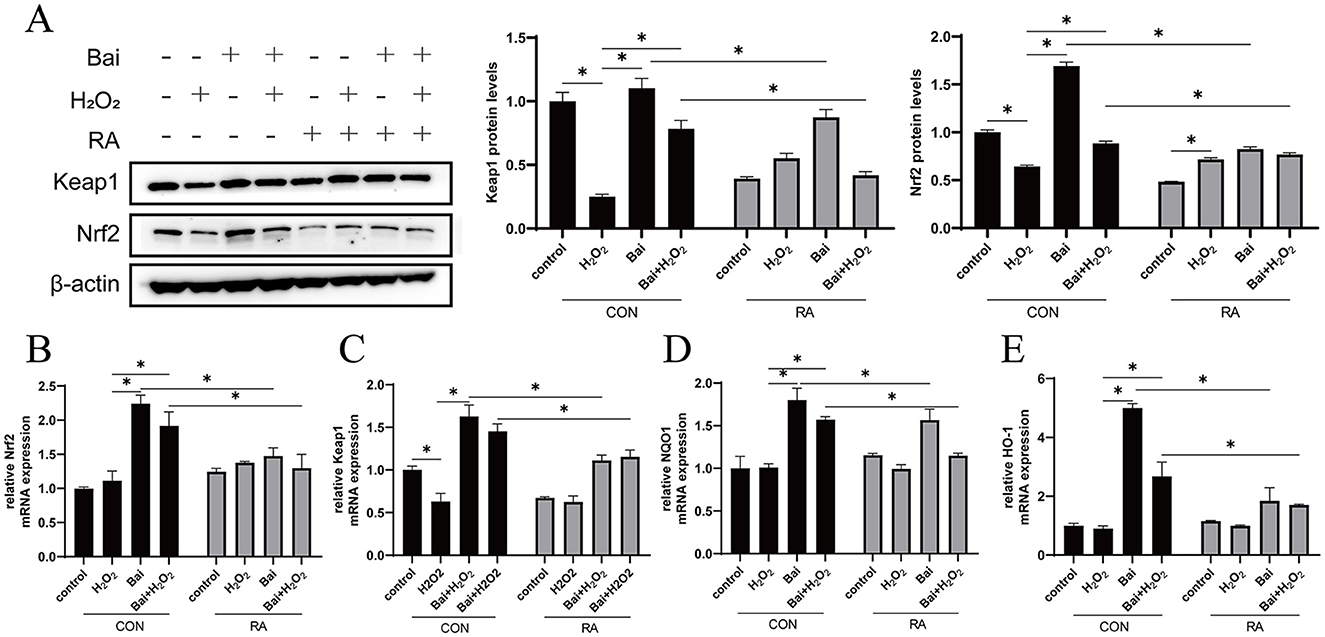

Baicalin activates Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway

The H2O2 treatment significantly reduced Nrf2 and Keap1 protein expression levels (P < 0.05) compared to the CON group (Figure 3A). Then, the above results were further verified by qRT-PCR, and the expression of Nrf2 and Keap1 mRNA was consistent with the Western blotting results (P < 0.05) (Figures 3B, C). In addition, baicalin treatment also increased the mRNA abundance of the downstream antioxidant genes NQO1 and HO-1, while the addition of RA inhibited the activation of NQO1 and HO-1 by baicalin (P < 0.05) (Figures 3D, E).

Figure 3. Activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway by baicalin. BMECs were treated with 5 μM RA for 1 h, and baicalin (10 μM) was then added for 18 h before cotreatment with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h. (A) Western blot analysis of Keap1 and Nrf2 protein levels in BMECs. Immunoreactive bands are shown on the left, and quantitative results are shown on the right. (B) Nrf2 mRNA levels in BMECs. (C) Keap1 mRNA levels in BMECs. (D) HO-1 mRNA levels in BMECs. (E) NQO1 mRNA levels in BMECs. *P < 0.05.

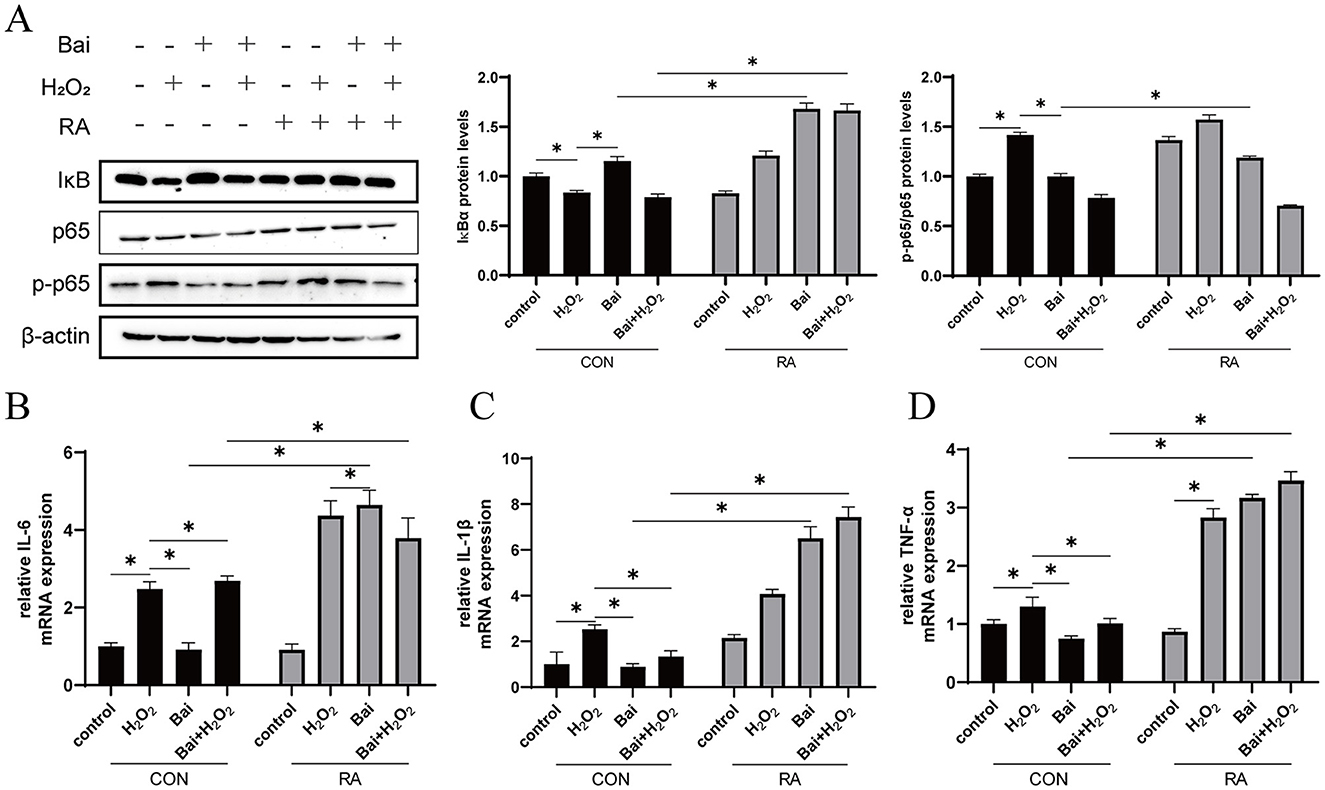

Baicalin inhibits the H2O2-induced NF-κB signaling pathway

The effects of baicalin on BMECs inflammation and the regulatory effects of Nrf2 on inflammation are shown in Figure 4. Compared with the CON group, H2O2 treatment decreased the IκBα protein expression level and increased the p-p65/p65 ratio (P < 0.05) (Figure 4A), while baicalin had the opposite effect. This effect of baicalin was reversed after the addition of RA. Interleukin IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor TNF-α are the main cellular inflammatory factors and play an important role in BMECs inflammatory response. H2O2 treatment significantly increased the mRNA content of the downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (P < 0.05) (Figures 4B–D). However, with or without cotreatment with H2O2, baicalin inhibited the mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, and the addition of RA effectively blocked the inhibitory effect of baicalin.

Figure 4. Baicalin inhibits the H2O2-induced NF-κB signaling pathway. BMECs were treated with 5 μM RA for 1 h, and baicalin (10 μM) was then added for 18 h before cotreatment with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h. (A) Western blot analysis of IκBα, p65 and p-p65 protein levels in BMECs. Immunoreactive bands are shown on the left, and quantitative results are shown on the right. (B) IL-6 mRNA levels in BMECs. (C) IL-1β mRNA levels in BMECs. (D) TNF-α mRNA levels in BMECs. *P < 0.05.

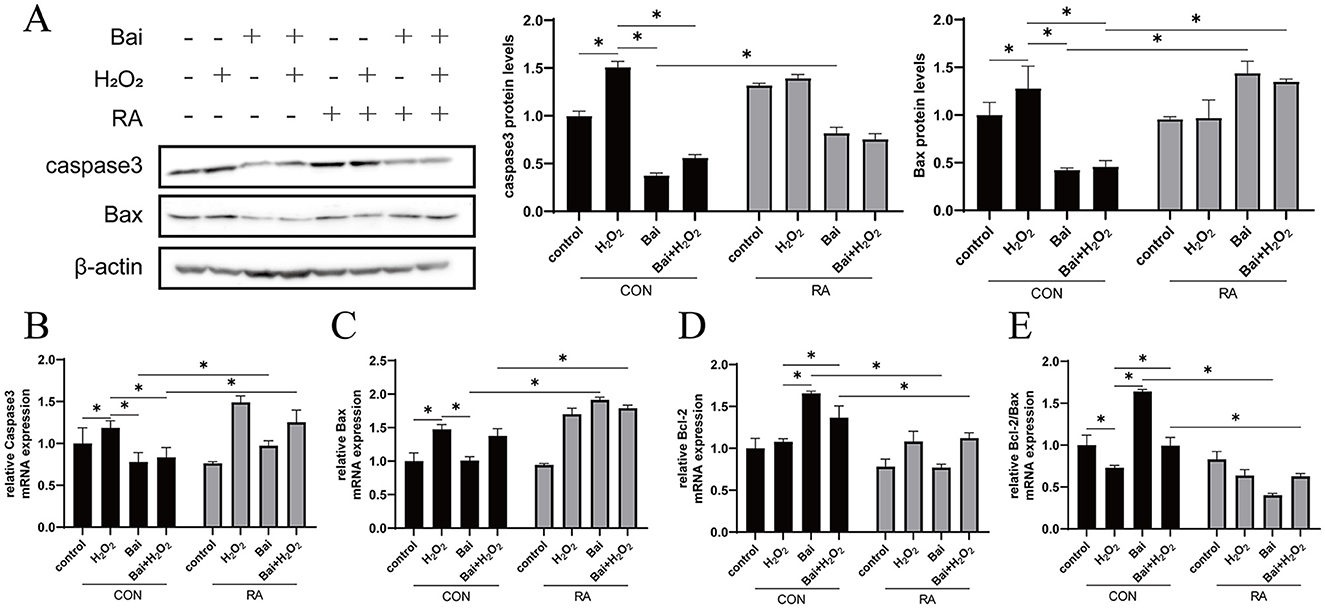

Baicalin inhibits the H2O2-induced caspase-3/Bcl-2 signaling pathway

The H2O2 treatment increased caspase-3 and Bax protein expression levels (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A), while baicalin treatment had an opposite effect on H2O2 with or without cotreatment with H2O2. This effect of baicalin was inhibited by the addition of RA. In addition, the above results were further validated using qRT–PCR, which showed that H2O2 treatment increased caspase-3 and Bax mRNA abundance and decreased the Bcl-2/Bax ratio (P < 0.05) (Figures 5B–E). However, baicalin treatment decreased caspase-3 and Bax mRNA abundance and increased Bcl-2 and Bcl-2/Bax ratios (P < 0.05), and the addition of RA effectively inhibited the effect of baicalin.

Figure 5. Baicalin inhibits the H2O2-induced caspase3/Bcl-2 signaling pathway. BMECs were treated with 5 μM RA for 1 h, and baicalin (10 μM) was then added for 18 h before cotreatment with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h. (A) Western blot analysis of caspase3 and Bax protein levels in BMECs. Immunoreactive bands are shown on the left, and quantitative results are shown on the right. (B) Caspase3 mRNA levels in BMECs. (C) Bax mRNA levels in BMECs. (D) Bcl-2 mRNA levels in BMECs. (E) Ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax mRNA levels in BMECs. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

The BMECs play a crucial role in the antioxidant process as the first line of defense against the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms and are an ideal model for establishing oxidative stress in vitro. In the current study, BMECs induced by H2O2 were used to construct an oxidative stress model. The results revealed that the induction of BMECs with 200 μM H2O2 for 6 h drastically decreased cell viability as well as increased ROS levels. In contrast, treating BMECs with 10 M baicalin for 24 h reversed the damage caused by H2O2 to BMECs. The biological effect of baicalin in enhancing cell growth might be the cause of these outcomes. Perruchot et al. demonstrated that baicalin treatment of BMECs could inhibit the synthesis of ROS and free radicals, providing a protective function in the body's antioxidant defense system (18). It illustrated that low-concentration baicalin (1–10 μg/mL) pre-treatment protected BMECs from H2O2-induced oxidative stress damage by regulating cell proliferation and the antioxidant response.

All organisms could produce ROS during cellular metabolism (19, 20). Numerous biological processes, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death, are linked to ROS. However, the breakdown of antioxidant defense systems leads to a decrease in antioxidant capacity and an overabundance of ROS, which triggers oxidative damage (20, 21). Relevant studies have shown that flavonoids, the primary active ingredient in baicalin, could effectively prevent peroxide and inhibit the occurrence of free radical chain reactions (14, 15). In this study, baicalin was found to reduce the accumulation of ROS in H2O2-induced BMECs. These results suggest that baicalin plays an antioxidant role in reducing H2O2-induced ROS accumulation. The MDA content and SOD activity in cells could reflect the degree of free radical damage (21, 22). The current research results have found that H2O2 increased the MDA content in BMECs, while baicalin treatment significantly reduced the MDA content in cells, increased SOD activity and T-AOC levels. The results are consistent with a recent study by Wang et al. (22) and Zhou et al. (23), which showed that baicalin supplementation significantly reduced the levels of ROS and MDA. It is indicated that baicalin could enhance the antioxidant defense system and protect cells from oxidative stress and apoptosis. After Nrf2 is activated, it could regulate the gene expression of antioxidant-related enzymes and proteins (24). Therefore, the antioxidant effect of baicalin might be related to the Nrf2 signaling pathway. To further verify this, we added the Nrf2 inhibitor RA and found that RA effectively blocked the antioxidant effect of baicalin. Therefore, current research confirmed that baicalin has the potential to prevent oxidative stress and might mediate the action of Nrf2.

The Nrf2 pathway is a key regulator in the cellular anti-oxidative stress and defense system (25), and its expression could be activating and negatively regulated through the N-terminal structural domain by Kelch, like ECH-related protein 1 (26). Therefore, to verify the effect of baicalin on Nrf2, the expression of Nrf2 and its related proteins was examined in this study. The results showed that Nrf2 was activated by Keap1 degradation, which resulted in the subsequent translocation in the presence or absence of H2O2. Baicalin treatment significantly increased the expression levels of Nrf2, Keap1, NQO1 and HO-1 proteins, and the addition of RA inhibited the promotion of Nrf2 and Keap1 protein expression by baicalin. Ma et al. also discovered that baicalin could play an antioxidant role by activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway and increasing the expression of HO-1, which is consistent with the conclusion of this study (27). Previous studies have shown that baicalin could prevent Keap1 from binding to Nrf2 through a modified Keap1 protein complex, resulting in reduced ubiquitination and thereby encouraging the expression of Nrf2 (28). These results demonstrated that baicalin could maintain the dynamic homeostasis of the body by activating the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway, thus protecting BMECs from H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

It has been reported that baicalin could effectively inhibit allergic inflammation exudation, reduce capillary permeability, and inhibit intestinal inflammation (29). In this study, H2O2 treatment increased the mRNA levels of downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1 β, and TNF-α, and this effect was reversed by baicalin supplementation. Shen reported that baicalin pretreatment could reduce the levels of IL-6, IL-1 β, and TNF-α in a mouse lung inflammation model, thus improving pathological changes in the lungs and reducing the body's inflammatory reaction (30). Consequently, the mechanism of anti-inflammatory baicalin might involve the inhibition of inflammation-related proteins and the blocking of NF-κB pathway activation (31). During the resting state, the NF-κB/Rel transcription factor binds to the upstream inhibitory κB kinase (IκB) to form a complex and is present in the cytoplasm in an inactive form. When cells are triggered, IκB kinase β (IKKβ) is phosphorylated, leading to the hydrolysis of IκBα by proteases and the release of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors into the nucleus as NF-κB p65, which in turn regulates the expression of downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines. ROS could directly activate IκB and induce nuclear translocation of the inflammatory mediator NF-κB, thereby regulating the expression of inflammation- and oxidative stress-related genes (32, 33). Interestingly, many of the downstream products encoded by NF-κB are in turn activators of ROS, thus producing feedback effects exacerbating oxidative stress and ultimately creating a vicious cycle (34, 35). Therefore, we investigated the effect of baicalin on NF-κB related genes. The results indicated that baicalin could reduce the expression of NF-κB. Zhang et al. (36) and Li et al. (37) showed that baicalin protects cells from inflammatory damage by down-regulating the expression of the transcription factor NF-κB. Jiang reported that baicalin pretreatment could reduce the levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α in the cell supernatant, thereby significantly reducing the activity of NF-κB and reducing the inflammatory reaction of the body (38). It is consistent with the results of this study. Meanwhile, it has been discovered that activation of Nrf2 could inhibit the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway, reduce DNA oxidative damage, and thus alleviate inflammation and apoptosis (2). To further verify whether Nrf2 regulates the inflammatory response, we added the Nrf2 inhibitor RA and found that it blocked the inhibitory effect of baicalin on inflammatory cytokines, such as NF-κB. This result confirmed that Nrf2 mediates the regulatory effect of baicalin on inflammation.

Furthermore, apoptosis is also mediated by oxidative stress (39). We found that the modulation of oxidative stress by baicalin might inhibit apoptosis. Caspases are usually present as non-activated zymogens in most animal cells, and caspase zymogen activation is a central process in the onset of apoptosis, where caspase-3 is mainly involved in the execution of apoptosis. The apoptosis-related genes Bcl-2 and Bax belong to the Bcl-2 family. Bax could promote apoptosis, while Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein that could inhibit the activation of caspase to prevent apoptosis (40). It has been shown that activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway could effectively alleviate mitochondrial damage and inhibit apoptosis (2, 41). Therefore, we explored the effect of Nrf2 signaling pathway inhibition on apoptosis. Baicalin significantly inhibited the H2O2-induced expression of caspase-3 and Bax and upregulated the expression of Bcl-2, while the inhibitor RA reversed these effects. Previous studies have shown that when apoptotic signals stimulate cells, the pro-apoptotic protein Bax oligomerizes and induces an increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability. It subsequently promotes the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, activates downstream caspase-3, and initiates the caspase cascade, resulting in the specific cleavage of downstream substrates, thereby triggering apoptosis. It is reported that baicalin supplementation could increase cell viability, elevate mitochondrial membrane potential, upgrade Bcl-2 levels and decrease caspase-3 and Bax levels, and our study also confirms this finding (42). This result suggests that baicalin might regulate the caspase/Bcl-2 signaling pathway through Nrf2 mediation, thereby inhibiting apoptosis.

Conclusions

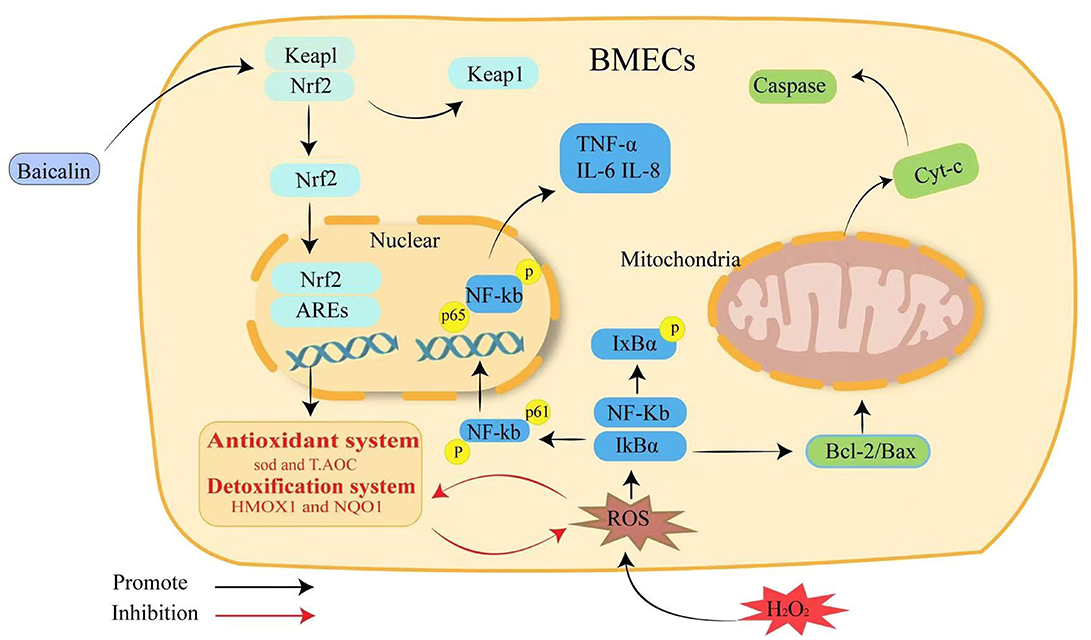

In conclusion, BMECs are stimulated by H2O2, inducing oxidative damage and inflammation, disrupting cellular homeostasis, and leading to cell apoptosis. Baicalin could increase the expression of downstream antioxidant genes NQO1 and HO-1, as well as antioxidant system SOD and T-AOC, by activating Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway, thus alleviating H2O2-induced oxidative damage in BMECs. The NF-kB inflammatory pathway and the caspase/Bcl-2 apoptotic signaling pathway are further inhibited, thereby reducing ROS production via Nrf2-mediated mechanisms (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Schematic summary of the effect and mechanism of baicalin on H2O2-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in BMECs. Baicalin resists H2O2-induced oxidative damage in BMECs by activating the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway and reducing ROS production, which in turn inhibits NF-κB inflammation and the caspase3/Bcl-2 apoptotic pathway to maintain intracellular redox homeostasis.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

XK: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZG: Investigation, Writing – original draft. XY: Investigation, Writing – original draft. HL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. TG: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Science and Technology R&D Joint Fund of Henan Province in China (232103810010), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province in China (232300420005), and China Agriculture Research System (CARS-36).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2024.1504887/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Huang W-Y, Wu H, Li D-J, Song J-F, Xiao Y-D, Liu C-Q, et al. Protective effects of blueberry anthocyanins against H2O2-induced oxidative injuries in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Agric Food Chem. (2018) 66:1638–48. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b06135

2. Sun X, Jia H, Xu Q, Zhao C, Xu C. Lycopene alleviates H2O2-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells via the NFE2L2 signaling pathway. Food Funct. (2019) 10:6276–85. doi: 10.1039/C9FO01922G

3. Meng M, Huo R, Wang Y, Ma N, Shi X, Shen X, et al. Lentinan inhibits oxidative stress and alleviates LPS-induced inflammation and apoptosis of BMECs by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. (2022) 222 (Pt B):2375–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.024

4. Piras F, Sogos V, Pollastro F, Appendino G, Rosa A. Arzanol, a natural phloroglucinol α-pyrone, protects HaCaT keratinocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative stress, counteracting cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, and mitochondrial depolarization. J Appl Toxicol. (2024) 44:720–32. doi: 10.1002/jat.4570

5. Guo Y, Balasubramanian B, Zhao Z-H, Liu W-C. Marine algal polysaccharides alleviate aflatoxin B1-induced bursa of Fabricius injury by regulating redox and apoptotic signaling pathway in broilers. Poult Sci. (2021) 100:844–57. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.10.050

6. Guo W, Liu J, Sun J, Gong Q, Ma H, Kan X, et al. Butyrate alleviates oxidative stress by regulating NRF2 nuclear accumulation and H3K9/14 acetylation via GPR109A in bovine mammary epithelial cells and mammary glands. Free Radic Biol Med. (2020) 152:728–42. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.016

7. Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. (2007) 12:211–21. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9054-4

8. Kan X, Liu J, Chen Y, Guo W, Xu D, Cheng J, et al. Myricetin protects against H2 O2 -induced oxidative damage and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. (2021) 236:2684–95. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30035

9. Jiao W, Wang Y, Kong L, Ou-Yang T, Meng Q, Fu Q, et al. CART peptide activates the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway and protects hippocampal neurons in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2018) 501:1016–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.101

10. Tian X-Z, Li J-X, Luo Q-Y, Wang X, Xiao M-M, Zhou D, et al. Effect of supplementation with selenium-yeast on muscle antioxidant activity, meat quality, fatty acids and amino acids in goats. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:813672. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.813672

11. Yan N, Xu Z, Qu C, Zhang J. Dimethyl fumarate improves cognitive deficits in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion rats by alleviating inflammation, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis via NRF2/ARE/NF-κB signal pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 98:107844. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107844

12. Minelli A, Grottelli S, Mierla A, Pinnen F, Cacciatore I, Bellezza I. Cyclo(His-Pro) exerts anti-inflammatory effects by modulating NF-κB and Nrf2 signalling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2012) 44:525–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.12.006

13. Hwang H, Hur SD, Lee J, Han Y, Hong S, Motoyama H. Plutonium fallout reconstructed from an Antarctic Plateau snowpack using inductively coupled plasma sector field mass spectrometry. Sci Total Environ. (2019) 669:105. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.105

14. Hong C, Cao J, Wu C-F, Kadioglu O, Schüffler A, Kauhl U, et al. The Chinese herbal formula Free and Easy Wanderer ameliorates oxidative stress through KEAP1-NRF2/HO-1 pathway. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:11551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10443-6

15. Guo Z, Mo Z. Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway in angiogenesis and vascular diseases. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. (2020) 14:869–83. doi: 10.1002/term.3053

16. Gao W, Xu B, Zhang Y, Liu S, Duan Z, Chen Y, et al. Baicalin attenuates oxidative stress in a tissue-engineered liver model of NAFLD by scavenging reactive oxygen species. Nutrients. (2022) 14:541. doi: 10.3390/nu14030541

17. Duan X-Y, Sun Y, Zhao Z-F, Shi Y-Q, Ma X-Y, Tao L, et al. Baicalin attenuates LPS-induced alveolar type II epithelial cell A549 injury by attenuation of the FSTL1 signaling pathway via increasing miR-200b-3p expression. Innate Immun. (2021) 27:294–312. doi: 10.1177/17534259211013887

18. Perruchot M-H, Gondret F, Robert F, Dupuis E, Quesnel H, Dessauge F. Effect of the flavonoid baicalin on the proliferative capacity of bovine mammary cells and their ability to regulate oxidative stress. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e6565. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6565

19. Schieber M, Chandel NS. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. (2014) 24:R453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034

20. De Almeida AJ PO, De Oliveira JC PL, Da Silva Pontes LV, et al. ROS: basic concepts, sources, cellular signaling, and its implications in aging pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2022) 2022:1225578. doi: 10.1155/2022/1225578

21. Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: a review. Eur J Med Chem. (2015) 97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040

22. Wang B, Zhu X, Kim Y, Li J, Huang S, Saleem S, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition activates transcription factor Nrf2 and protects against cerebral ischemic damage. Free Radic Biol Med. (2012) 52:928–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.006

23. Zhou B-r, Yin H-b, Xu Y, Wu D, Zhang Z-h, Yin Z-q, et al. Baicalin protects human skin fibroblasts from ultraviolet A radiation-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis. Free Radic Res. (2012) 46:1458–71. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.726355

24. Cardozo LFMF, Pedruzzi LM, Stenvinkel P, Stockler-Pinto MB, Daleprane JB Jr, Leite ML, et al. Nutritional strategies to modulate inflammation and oxidative stress pathways via activation of the master antioxidant switch Nrf2. Biochimie. (2013) 95:1525–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.04.012

25. Wang X, Yu J-Y, Sun Y, Wang H, Shan H, Wang S. Baicalin protects LPS-induced blood-brain barrier damage and activates Nrf2-mediated antioxidant stress pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 96:107725. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107725

26. Wang L, Zhang X, Xiong X, Zhu H, Chen R, Zhang S, et al. Nrf2 regulates oxidative stress and its role in cerebral ischemic stroke. Antioxidants. (2022) 11:2377. doi: 10.3390/antiox11122377

27. Ma L, Wu F, Shao Q, Chen G, Xu L, Lu F. Baicalin alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy via Nrf2 and MAPK signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2021) 15:3207–21. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S319260

28. Li R, Liu Y, Shan Y-G, Gao L, Wang F, Qiu C-G. Bailcalin protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy through Keap1/Nrf2/AMPK-mediated antioxidative and lipid-lowering effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2019) 2019:3206542. doi: 10.1155/2019/3206542

29. Wen Y, Wang Y, Zhao C, Zhao B, Wang J. The pharmacological efficacy of baicalin in inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:9317. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119317

30. Shen B, Zhang H, Zhu Z, Ling Z, Zeng F, Wang Y, et al. Baicalin relieves LPS-induced lung inflammation via the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Molecules. (2023) 28:1873. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041873

31. Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transd Target Therapy. (2017) 2:17023. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23

32. Schreck R, Meier B, Männel DN, Dröge W, Baeuerle PA. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J Exp Med. (1992) 175:1181–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181

33. Brown DA, Aon MA, Frasier CR, Sloan RC, Maloney AH, Anderson EJ, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2010) 48:673–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.011

34. Morgan MJ, Liu Z. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. (2011) 21:103–15. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178

35. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin Immunol. (2014) 26:253–66. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.05.004

36. Zhang H, Li X, Wang J, Cheng Q, Shang Y, Wang G. Baicalin relieves Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-induced lung injury through regulating microRNA-221 to inhibit the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. (2021) 24:571. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12210

37. Li J, Zhang Q-Y, Lu Q-Y, Liu Q-Z, Guo L, Li M, et al. Baicalin relieves complement alternative pathway activation-induced lung inflammation through inhibition of NF-?B pathway. BMC Complement Med Ther. (2024) 24:334. doi: 10.1186/s12906-024-04622-y

38. Jiang J, Kao T-C, Hu S, Li Y, Feng W, Guo X, et al. Protective role of baicalin in the dynamic progression of lung injury to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. (2023) 114:154777. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154777

39. Chambers JW, Lograsso PV. Mitochondrial c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling initiates physiological changes resulting in amplification of reactive oxygen species generation. J Biol Chem. (2011) 286:16052–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223602

40. Perlman H, Zhang X, Chen MW, Walsh K, Buttyan R. An elevated bax/bcl-2 ratio corresponds with the onset of prostate epithelial cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. (1999) 6:48–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400453

41. Yang X, Zhang X, Zhang J, Ji Q, Huang W, Zhang X, et al. Spermatogenesis disorder caused by T-2 toxin is associated with germ cell apoptosis mediated by oxidative stress. Environ Pollut. (2019) 251: 372–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.023

Keywords: baicalin, bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis

Citation: Kong X, Wang M, Guo Z, Yang X, Lian H, Gao T, Zhang L and Fu T (2024) Evaluation the protective role of baicalin against H2O2-driven oxidation, inflammation and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1504887. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1504887

Received: 01 October 2024; Accepted: 25 November 2024;

Published: 12 December 2024.

Edited by:

Valiollah Palangi, Ege University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Irfan Baboo, Cholistan University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, PakistanAshkan Fekri, University of Tehran, Iran

Copyright © 2024 Kong, Wang, Guo, Yang, Lian, Gao, Zhang and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liyang Zhang, emhhbmdsaXlhbmdAaGVuYXUuZWR1LmNu; Tong Fu, ZnV0b25nMjAwNEAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xiaohui Kong

Xiaohui Kong Mingyan Wang

Mingyan Wang Zhiheng Guo

Zhiheng Guo Xingda Yang

Xingda Yang Hongxia Lian1

Hongxia Lian1 Tengyun Gao

Tengyun Gao Liyang Zhang

Liyang Zhang Tong Fu

Tong Fu