94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Vet. Sci. , 31 March 2023

Sec. Veterinary Infectious Diseases

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1158196

Serim Hong1

Serim Hong1 Hye Jeong Kang2

Hye Jeong Kang2 Hye-Young Lee2

Hye-Young Lee2 Hye-Ri Jung1

Hye-Ri Jung1 Jin-San Moon2

Jin-San Moon2 Soon-Seek Yoon2

Soon-Seek Yoon2 Ha-Young Kim2*

Ha-Young Kim2* Young Ju Lee1*

Young Ju Lee1*The introduction of bacteria into slaughterhouses can lead to microbial contamination in carcasses during slaughter, and the initial level of bacteria in carcasses is important because it directly affects spoilage and the shelf life. This study was conducted to investigate the microbiological quality, and the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in 200 carcasses from 20 pig slaughterhouses across Korea. Distribution of microbial counts were significantly higher for aerobic bacteria at 3.01–4.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (42.0%) and 2.01–3.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (28.5%), whereas most of Escherichia coli showed the counts under 1.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (87.0%) (P < 0.05). The most common pathogen isolated from 200 carcasses was Staphylococcus aureus (11.5%), followed by Yersinia enterocolitica (7.0%). In total, 17 S. aureus isolates from four slaughterhouses were divided into six pulsotypes and seven spa types, and showed the same or different types depending on the slaughterhouses. Interestingly, isolates from two slaughterhouses carried only LukED associated with the promotion of bacterial virulence, whereas, isolates from two other slaughterhouses carried one or more toxin genes associated with enterotoxins including sen. In total, 14 Y. enterocolitica isolates from six slaughterhouses were divided into nine pulsotypes, 13 isolates belonging to biotype 1A or 2 carried only ystB, whereas one isolate belonging to bio-serotype 4/O:3 carried both ail and ystA. This is the first study to investigate microbial quality and the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in carcasses from slaughterhouses nationally, and the findings support the need for ongoing slaughterhouse monitoring to improve the microbiological safety of pig carcasses.

Foodborne illness is an important public health problem that causes an estimated 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths annually worldwide (1). In particular, food-producing animals are the major reservoirs of many foodborne pathogens such as Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter spp. Yersinia spp., and Listeria monocytogenes (2–4), and contamination of carcasses with foodborne pathogens can occur at several stages within the food production chain (5).

The slaughter stage has been a major focus of food safety interventions. Namely, the introduction of bacteria into slaughterhouses can lead to microbial contamination at several processing steps during slaughter. The initial opening of the carcass and the removal of highly contaminated organs, such as the intestines, pluck set and tonsils (6), increase the risk of microbial spread to carcass surfaces. Moreover, insufficient disinfection of cutting knifes or machinery can lead to cross-contamination between carcasses (7).

Recently, Bae et al. (8) reported the first study tracking foodborne pathogens in pigs and related pork products at all points along the pork supply chain, including farms, slaughterhouses, meat processing plants, and retail stores, in Korea. In particular, Y. enterocolitica and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli were the major pathogens isolated from carcasses in slaughterhouses. Moreover, Im et al. (9) reported that S. aureus, Salmonella spp., and C. perfringens were isolated from edible pig intestines in 11 pig slaughterhouses in Korea. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, evaluation of the hygiene status in pig slaughterhouses mainly targets Salmonella and other major pathogens (10). In Korea, foodborne pathogens surveillance at the slaughter stage has been conducted nationwide since 2010 to ensure food safety and reduce risks to human health. This study aimed to report on microbiological quality and distribution of foodborne pathogens in pig slaughterhouses nationwide and identify the genetic relationships and characteristics of major foodborne pathogens.

In total, 200 carcasses were collected from 20 pig slaughterhouses across Korea between 2020 and 2021. In addition, pigs are produced mostly from three-way hybrids: Landrace, Yorkshire, and Duroc, and slaughtered at a live weight of ~110 kg. According to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) protocol (11), a sterile sponge (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA) hydrated with 10 ml of buffered peptone water (BPW; Difco, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to swab a 300 cm2 surface area composite that included one belly site (100 cm2), one ham site (100 cm2), and one jowls site (100 cm2) from each carcass cooled at 4°C for 24 h after slaughter. Ten carcasses were collected from each slaughterhouse, and all swab samples were transferred to the laboratory under 4°C conditions.

Swab samples were inoculated in 30 ml of BPW and homogenized for 1 min using a stomacher (Stomacher 80 Biomaster, Seward, UK). To determine the aerobic bacteria and E. coli counts, aliquots containing serially diluted (10-fold) swab samples were performed using the TEMPO® reader system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Étoile, France), and Petrifilm plates (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The isolation of foodborne pathogens was performed according to the standard microbiological protocol notified by the MFDS (11). Briefly, to isolate Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, Campylobacter spp., S. aureus, C. perfringens, and Y. enterocolitica, 1 ml of BPW was inoculated into each 9 ml of mEC with novobiocin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), Bolton broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) with laked horse blood (Oxoid), Tryptic soy broth (BD Biosciences) with 10% NaCl, Cooked meat medium (BD Biosciences), and Peptone sorbitol bile broth (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C for E. coli, S. aureus, and C. perfringens; 48 h at 42°C for Campylobacter spp.; and 48 h at 30°C for Y. enterocolitica. For Salmonella spp., 10 mL of BPW was primarily incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and then 0.1 ml of pre-enriched BPW culture was inoculated in 10 ml of Rappaport–Vassiliadis broth (Oxoid) and incubated for 24 h at 42°C. For L. monocytogenes, 1 mL of BPW was also primarily inoculated in 9 ml of Listeria enrichment broth (BD Biosciences) and incubated for 24 h at 30°C, and then 0.1 ml of broth was secondarily enriched in 10 ml of Fraser broth (BD Biosciences) for 48 h at 37°C. All enriched media were streaked on Tellurite–Cefixime–Sorbitol MacConkey agar (Oxoid) for Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, Baird–Parker agar (Oxoid) supplemented with egg yolk tellurite emulsion (Oxoid) for S. aureus, Tryptose–Sulfite–Cycloserine agar supplemented with egg yolk emulsion (Oxoid) for C. perfringens, Cefsulodin–Irgasan–Novobiocin agar (BD Biosciences) for Y. enterocolitica, Xylose lysine tergitol−4 agar (BD Biosciences) for Salmonella spp., and Oxford agar (Oxoid) for L. monocytogenes followed by incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Modified campy blood–free agar (Oxoid) streaked for Campylobacter spp. was incubated for 48 h at 42°C. All suspect colonies were performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers (Table 1) (12–16, 19, 20), and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (bioMérieux). If the same species isolates from the same origin showed the same antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, then only one isolate was randomly selected.

Salmonella spp. was serotyped using commercial Salmonella O, H-phase 1 and H-phase 2 antisera (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) according to the Kauffmann–White scheme (17). L. monocytogenes was carried out using commercial antisera (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) against the serovars 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4c, 4d/4e, and 4b/4e following the manufacturer's instructions. Y. enterocolitica was serotyped using commercial antisera polyvalent group O:1–2, O:3, O:5, O:8, and O:9 (Denka Seiken) following the manufacturer's instructions.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 17 and 14 antimicrobial agents for S. aureus and Y. enterocolitica, respectively, were determined by the broth microdilution method using the commercially available Sensititre® panels EUST (TREK Diagnostic Systems, West Sussex, UK) and CMV3AGNF (TREK Diagnostic Systems), respectively, following the manufacturer's instructions. MICs were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines M100 (18), and Y. enterocolitica followed breakpoints in Enterobacteriaceae. S. aureus ATCC 25923 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were used as quality-control strains for S. aureus and Y. enterocolitica, respectively.

PCR amplification was performed to detect toxin genes in S. aureus and virulence genes in Y. enterocolitica as described by Van Duijkeren et al. (21) and Platt-Samoraj et al. (22), respectively. The toxin genes included those encoding enterotoxins (sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seg, seh, sei, sej, sek, sel, sem, sen, seo, sep, seq, and ser), leukotoxin family (lukED), exfoliative toxins (eta and etb), toxic shock syndrome toxin (tsst-1), and panton–valentine leukocidin (pvl), and the virulence genes included attachment invasion locus (ail), Yersinia stable toxin A (ystA), and ystB.

Staphylococcus aureus protein A (spa) typing was performed using as described by Shopsin et al. (23) using Ridom StaphType (Ridom GmbH, Wurzburg, Germany; www.spaserver.ridom.de). The biotyping of Y. enterocolitica was performed using lipase, esculin, indole, xylose, trehalose, pyrazinamidase, and Voges–Proskauer biochemical tests according to methods described by Weagant et al. (24).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PulseNet protocol (25), DNA was digested by SmaI (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) for S. aureus and by AscI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for Y. enterocolitica. Electrophoresis was performed using the CHEF-DRIII pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and PFGE banding profiles were analyzed using Bionumerics software version 8.0 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Relatedness was calculated using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages algorithm based on the Dice similarity index, and a similarity coefficient of 90% was fixed to assemble PFGE clusters.

Pearson's chi-square test with Bonferroni correction were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

The distribution of aerobic bacteria and E. coli counts in pig carcasses is presented in Table 2. Distribution of microbial counts were significantly higher for aerobic bacteria at 3.01–4.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (42.0%) and 2.01–3.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (28.5%), whereas most of E. coli showed the counts under 1.00 log10 CFU/cm2 (87.0%) (P < 0.05).

The prevalence of foodborne pathogens in slaughterhouses and pig carcasses is presented in Table 3. The most common pathogen isolated from 200 carcasses was S. aureus (11.5%), followed by Y. enterocolitica (7.0%), C. perfringens (4.0%), and C. coli (4.0%), and the most prevalent pathogens in 20 slaughterhouses were S. aureus (40.0%), Y. enterocolitica (30.0%), and C. perfringens (25.0%) (P < 0.05). In particular, Y. enterocolitica was divided into three serotypes, and Y. enterocolitica O:5 showed the highest prevalence in slaughterhouses (25.0%) and carcasses (5.0%). Moreover, two C. coli and one S. Agona isolates were obtained from two (10.0%) and one (5.0%) slaughterhouses, respectively, and three L. monocytogenes isolates obtained from three slaughterhouses were divided into three serotypes: 1/2a, 1/2b, and 1/2c.

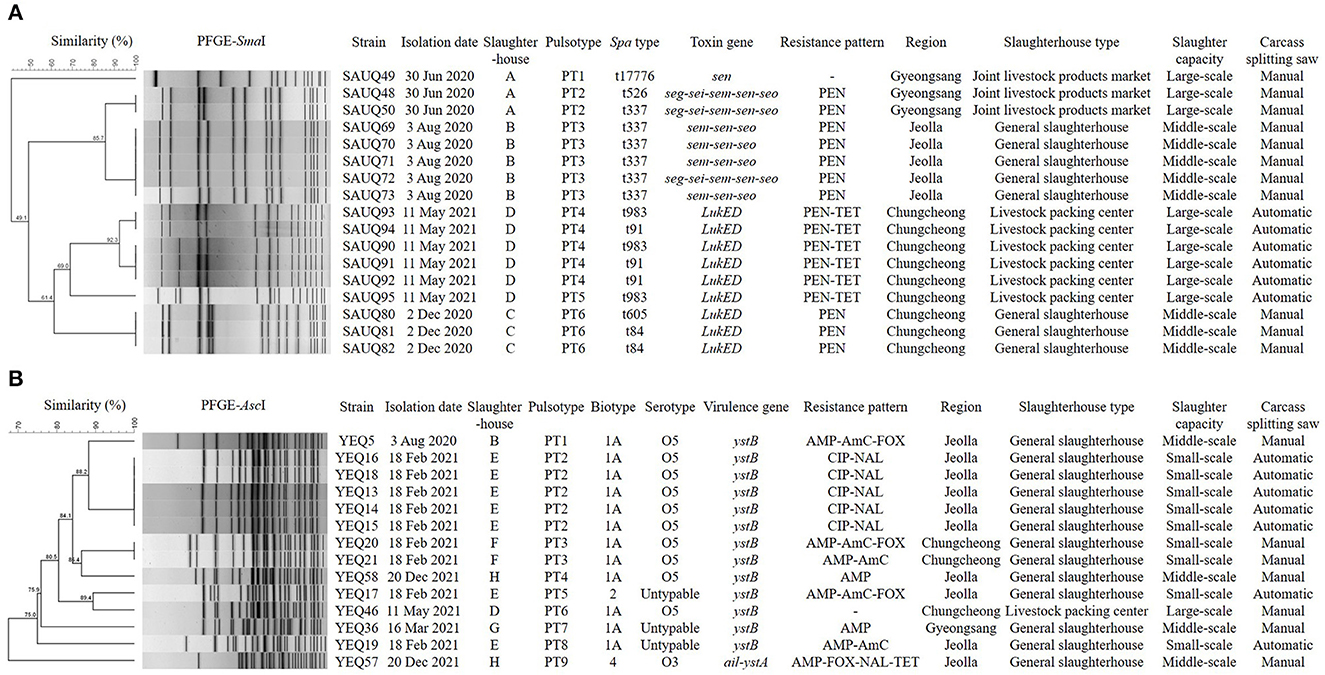

Characteristics of phylogenetic, antibiotic resistance, and biotypic profiles of two major pathogens, S. aureus and Y. enterocolitica are presented in Figure 1. In total, 17 S. aureus isolates from four slaughterhouses were divided into six pulsotypes and seven spa types, and showed the same or different types depending on the slaughterhouses. Specifically, five isolates from slaughterhouse B showed the same pulsotype and spa type, but those from slaughterhouse D could be divided into two pulsotypes and two spa types. Furthermore, isolates from slaughterhouses A and C divided into two and one pulsotypes, and three and two spa types, respectively. Interestingly, isolates from slaughterhouses C and D only carried LukED associated with the promotion of bacterial virulence, whereas those from slaughterhouses A and B carried one or more toxin genes associated with enterotoxins, including sen. In total, 14 Y. enterocolitica isolates from six slaughterhouses were divided into nine pulsotypes, but isolates showed three biotypes and two serotypes, excluding three O:untypable isolates. Moreover, 13 isolates belonging to biotype 1A or 2 carried only ystB encoding an enterotoxin, and one isolate belonging to bio-serotype 4/O:3 carried both ail and ystA, which encode an attachment invasion locus and enterotoxin, respectively.

Figure 1. Dendrogram showing genetic relationships among the strains characterized by PFGE profiles (A) Staphylococcus aureus, (B) Yersinia enterocolitica. Showing similarities of < 90% in PFGE were considered to be unrelated. The types of slaughterhouses are divided into Livestock packing center (slaughterhouse for slaughter, processing, and sale), Joint livestock products market (slaughterhouse for slaughter and sale), and General slaughterhouse (slaughterhouse for slaughter). Slaughter capacities (pigs/day) are divided into small-scale (≤ 900), middle-scale (901–1,500), and large-scale (≥ 1,501). PEN, Penicillin; TET, Tetracycline; AMP, Ampicillin; AmC, Amoxicillin/ Clavulanic acid; FOX, Cefoxitin; CIP, Ciprofloxacin; NAL, Nalidixic acid.

Microbial contamination of meat is unavoidable because microorganisms are present on animals and in their environments. Thus, the initial level of bacteria in carcasses is important because as it directly affects spoilage and the shelf life (5). According to the Livestock Products Sanitary Control Act and Modernization of Swine Slaughter Inspection (10, 26), the hygienic quality of pig carcass is considered satisfactory when aerobic bacteria and E. coli counts are < 5.00 log10 CFU/cm2 and < 4.00 log10 CFU/cm2, respectively. In this study, although 163 (81.5%) among 200 carcasses met this criterion for aerobic bacterial counts, 37 (18.5%) carcasses showed aerobic bacterial counts exceeding 5.00 log10 CFU/cm2. Lebret and Candek-Potokar (27) reported that microbial growth in pork carcasses depends on the environmental conditions during the aging process, and microbes ultimately affect pork spoilage and quality deterioration. Therefore, it is important to control microbial growth during storage by enhancing hygiene. In contrast, all carcasses had E. coli counts of < 4.00 log10 CFU/cm2, with 87.0% of carcasses showing counts of ≤ 1.00 log10 CFU/cm2. Van Ba et al. (28) previously reported that the average counts of aerobic bacteria and E. coli in pig carcasses in Korea were satisfactory, and Lindblad et al. (29) and Bohaychuk et al. (30) also reported that pig carcasses from Sweden and Canada met the criteria for aerobic bacteria and E. coli counts, respectively. In developed countries, risk factors in slaughterhouses are strictly managed because a high initial microbial load, poor hygiene practices, or high temperatures (>15°C) in the slaughtering lines can affect the distribution of microorganisms (31), and the quality of carcasses can be improved through food safety/HACCP implementation, non-conformities control, site hygiene, and pest control (32).

Several studies have reported that the most common foodborne pathogens associated with pigs are Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and Y. enterocolitica (33–35). In this study, the prevalence of seven major foodborne pathogens was investigated, and five pathogens were isolated from carcasses with S. aureus being the most prevalent (40.0% of slaughterhouses and 11.5% of carcasses). The MFDS (36) reported 21 cases of staphylococcal food poisoning involving 378 patients in Korea from 2018 to 2022. S. aureus is one of the most common causes of food poisoning, and is commonly found on the skin and in the mucous membranes of human beings and animals, and is particularly dangerous at slaughterhouses because of its potential for transmission from animals to slaughter operators and vice-versa (37). In Germany, Greece, and South Africa, the prevalence of S. aureus in pig carcasses were reported to be 6.0%, 15.5%, and 32.5%, respectively (38–40). The high prevalence of S. aureus in pig carcasses may be related to a lack of skinning of pigs during slaughter; therefore, it is important to minimize skin contamination during slaughter.

In this study, the second most frequently isolated pathogen was Y. enterocolitica (30.0% of slaughterhouses and 7.0% of carcasses). In the United States, Y. enterocolitica is estimated to cause ~117,000 cases of illnesses, 640 hospitalizations, and 35 deaths each year (41). In Europe, human yersiniosis is the third most common foodborne zoonotic disease after campylobacteriosis and salmonellosis (42). Pigs are considered the primary reservoirs of human yersiniosis globally because pigs are the only animal species from which pathogenic strains have frequently been isolated so far (43). Moreover, pigs infected with Y. enterocolitica shed the organism in feces on farms for prolonged periods, and Y. enterocolitica has been frequently isolated from the tonsils of pigs at slaughter (44). Therefore, pig carcasses can be contaminated based on their infected tissues and intestinal contents in slaughterhouses (45).

C. perfringens is one of the bacterial hazards identified in the Guides to Good Hygiene Practices, and of application of HACCP principles in the slaughtering because C. perfringens frequently colonizers of the intestinal tracts of various food animals (46). In this study, the prevalence of C. perfringens was only 4.0% in carcasses, but it was detected in as high as 25.0% of slaughterhouses. Therefore, for hygienic carcass production, it is necessary to fast animals on the farm before slaughter and reduce the contents of the gastrointestinal during slaughter (47).

Campylobacter jejuni was not found in this study, but C. coli was identified in 4.0% of carcasses. Several researchers have reported that the predominant species of Campylobacter in pigs is C. coli, whereas that in poultry and cattle is C. jejuni (48, 49). Campylobacter spp. do not usually cause clinical signs in animals, but reducing the abundance of Campylobacter in carcasses at slaughter can be an important step in the farm-to-table continuum through which Campylobacter enters the food chain.

Mechesso et al. (50) reported that the prevalence of S. agona was 10.8% in domestic pig carcasses from 2016 to 2018 in Korea, but in this study, this serovar was only isolated from one carcass. S. Agona is an important cause of food poisoning, and infection in humans usually occurs via the consumption of contaminated meat and eggs (51). Recently, Trinetta et al. (52) reported that the prevalence of S. Agona was 24.5% at 11 feed mills in eight states representative of the main pig production areas within the United States. Although the risk of feed-borne salmonellosis is difficult to quantify, this report indicated that Salmonella can be transmitted via contaminated feed through the food chain to pig farms, slaughterhouses, and ultimately to humans. Therefore, risk assessment studies for Salmonella-contaminated feed should be continuously performed to identify potential hazards.

In this study, the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of S. aureus and Y. enterocolitica, the main pathogens isolated from pig carcasses, were investigated. The prevalence of S. aureus and Y. enterocolitica had no relationship with the season, region, slaughterhouse type, slaughter capacity, and type of carcass splitting even though carcasses were collected from slaughterhouses across Korea (data not shown). Moreover, some isolates from the same slaughterhouse clustered in the same pulsotype, but 17 S. aureus isolates were ultimately divided into six pulsotypes. For identifying the epidemiological relevance of food poisoning bacteria, PFGE is generally preferred over other typing methods such as multilocus sequence typing or spa typing because standardization of the PFGE protocol has established a nomenclature for local pulsotypes in many countries (53), and because it is a highly discriminatory and valuable technique for the typing of classification within species (54).

The S. aureus isolates were divided into seven spa types, showing more diverse spa types than pulsotypes within the same slaughterhouse. Shopsin et al. (23) reported that spa typing provides clonal groupings that PFGE techniques cannot identify individually; thus, analyzing spa types together provides high differentiation in describing PFGE subtyping. In particular, among the spa types, t34 and t337 have been reported to be predominant in pigs worldwide (55), and t337 was also frequently confirmed in this study, consistent with previous reports (56).

In this study, 14 Y. enterocolitica isolates were divided into nine pulsotypes, whereas only three biotypes (1A, 2, and 5) and two serotypes (O3 and O5) were identified, excluding the untypable serotype. In general, Y. enterocolitica is divided into the non-pathogenic biotype 1A, weakly pathogenic biotypes 2–5, and highly pathogenic biotype 1B (57). Fortunately, biotype 1B was not identified in this study. Y. enterocolitica O:5, which was the most common serogroup in this study, has been reported to be the most prevalent serogroup worldwide, and it is mainly associated with non-pathogenicity type (16, 44). However, Y. enterocolitica bio-serotype 4/O:3, which was isolated from only one carcass in this study, is known to be pathogenic to humans (58).

In this study, all S. aureus isolates carried staphylococcal enterotoxin genes that induce food poisoning or leukotoxin genes that promote virulence (59). These two genes are located on mobile elements in bacterial genomes such as plasmids or pathogenic islands; thus they can easily be transferred horizontally between strains (60, 61).

In Y. enterocolitica, pathogenicity is associated with the presence of plasmids and chromosomal virulence genes, but the most commonly encoded virulence determinants are ail and the enterotoxin-encoding gene yst, which are chromosomal virulence markers (62). In particular, Y. enterocolitica biotype 1A, which is regarded as a non-pathogenic environmental strain, lacks the pYV plasmid (plasmid of Yersinia virulence) and most chromosomal virulence markers (63). In this study, all 12 Y. enterocolitica biotype 1A isolates harbored only ystB, which is recovered from wild animals and the environments, as previously described (64). However the ail, which usually accompanies ystA in pathogenic Y. enterocolitica, was identified in one Y. enterocolitica bio-serotype 4/O:3 isolate.

In this study, all S. aureus except one isolate showed the resistance to penicillin, and isolates from slaughterhouse D showed the resistance to both penicillin and tetracycline. Moreover, Y. enterocolitica showed the resistance to various antimicrobial subclasses, although there were similarities in antimicrobial resistant classes by slaughterhouse. The difference in the resistance of isolates by slaughterhouse is presumed to be attributable to differences in the antimicrobial classes mainly used in farms by region, because pigs are mainly slaughtered at slaughterhouses located in the region in which they are raised.

This is the first study to investigate microbial quality and the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in carcasses from slaughterhouses nationally, and the findings support the need for ongoing slaughterhouse monitoring to improve the microbiological safety of pig carcasses.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study was not required in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SH, J-SM, S-SY, H-YK, and YL conceived and designed all the experiments. SH, HK, H-YL, H-RJ, and H-YK participated in collecting the data and performing the tests. SH, H-YK, and YL analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural affairs, and Republic of Korea (grant number B-1543081-2022-23-02).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Disease: Foodborne Diseases Burden Epidemiology Reference Group 2007–2015. Geneva, Switzerland (2015). doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43978-4_3884

2. Abebe E, Gugsa G, Ahmed M. Review on major food-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. J Trop Med. (2020) 2020:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2020/4674235

3. Imre K, Herman V, Morar A. Scientific achievements in the study of the occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of major foodborne pathogenic bacteria in foods and food processing environments in romania: review of the last decade. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/5134764

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Food Safety. (2022). Availableonline at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed May 19, 2022).

5. Das AK, Nanda PK, Das A, Biswas S. Hazards and safety issues of meat and meat products. In: Food Safety and Human Health. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2019). p. 145–168 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816333-7.00006-0

6. Biasino W, De Zutter L, Mattheus W, Bertrand S, Uyttendaele M, Van Damme I. Correlation between slaughter practices and the distribution of Salmonella and hygiene indicator bacteria on pig carcasses during slaughter. Food Microbiol. (2018) 70:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.10.003

7. Swart AN, Evers EG, Simons RLL, Swanenburg M. Modeling of salmonella contamination in the pig slaughterhouse. Risk Anal. (2016) 36:498–515. doi: 10.1111/risa.12514

8. Bae D, Macoy DM, Ahmad W, Peseth S, Kim B, Chon J, et al. Distribution and characterization of antimicrobial resistant pathogens in a pig farm, slaughterhouse, meat processing plant, and in retail stores. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:2252. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10112252

9. Im MC, Seo KW, Bae DH, Lee YJ. Bacterial quality and prevalence of foodborne pathogens in edible offal from slaughterhouses in Korea. J Food Prot. (2016) 79:163–8. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-251

10. Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). Modernization of Swine Slaughter Inspection; Final Rule. (2019). Available online at: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/federal-register/rules/modernization-swine-slaughter-inspection (accessed January 18, 2023).

11. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Processing Standards and Ingredient Specifications for Livestock Products. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (2023).

12. Jung B, Lim H, Jung S. Development of differential media and multiplex PCR assays for the rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Korean J Vet Res. (2003) 43:231–237.

13. Arnold T, Scholz HC, Marg H, Rösler U, Hensel A. Impact of invA-PCR and culture detection methods on occurrence and survival of salmonella in the flesh, internal organs and lymphoid tissues of experimentally infected pigs. J Vet Med B. (2004) 51:459–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00808.x

14. Franck SM, Bosworth BT, Moon HW. Multiplex PCR for enterotoxigenic, attaching and effacing, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from calves. J Clin Microbiol. (1998) 36:1795–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.6.1795-1797.1998

15. Mason WJ, Blevins JS, Beenken K, Wibowo N, Ojha N, Smeltzer MS. Multiplex PCR protocol for the diagnosis of staphylococcal infection. J Clin Microbiol. (2001) 39:3332–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3332-3338.2001

16. Wannet WJ, Reessink M, Brunings HA, Maas HM. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by a rapid and sensitive duplex PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. (2001) 39:4483–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4483-4486.2001

17. Grimont P, Weill F-X. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella Servovars: WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference Research on Salmonella. Paris, France (2007). p. 1–166. Available online at: https://www.pasteur.fr/sites/default/files/veng_0.pdf (accessed May 20, 2023).

18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). M100, 30th ed. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA: CLSI (2020).

19. On SLW, Jordan PJ. Evaluation of 11 PCR assays for species-level identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Clin Microbiol. (2003) 41:330–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.330-336.2003

20. Yoo HS, Lee SU, Park KY, Park YH. Molecular typing and epidemiological survey of prevalence of Clostridium perfringens types by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. (1997) 35:228–32. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.228-232.1997

21. Van Duijkeren E, Ikawaty R, Broekhuizen-Stins MJ, Jansen MD, Spalburg EC, de Neeling AJ, et al. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains between different kinds of pig farms. Vet Microbiol. (2008) 126:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.07.021

22. Platt-Samoraj A, Ugorski M, Szweda W, Szczerba-Turek A, Wojciech K, Procajło Z. Analysis of the presence of ail, ystA and ystB genes in Yersinia enterocolitica Strains isolated from aborting sows and aborted fetuses. J Vet Med Ser B. (2006) 53:341–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2006.00969.x

23. Shopsin B, Gomez M, Montgomery SO, Smith DH, Waddington M, Dodge DE, et al. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. (1999) 37:3556–63. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.11.3556-3563.1999

24. Weagant S. D., Feng P., Stanfield JT. BAM Chapter 8, Yersinia enterocolitica. Bacteriological Analytical Manual. (2017). Availale online at: https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-8-yersinia-enterocolitica (accessed December 20, 2022).

25. Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). (2016). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/pfge.html (accessed January 18, 2023).

26. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Livestock Products Sanitary Control Act. Cheongju: MFDS (2023).

27. Lebret B, Candek-Potokar M. Review: pork quality attributes from farm to fork. Part I Carcass and fresh meat. Animal. (2022) 16:100402. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2021.100402

28. Van Ba H, Seo H-W, Seong P-N, Kang S-M, Cho S-H, Kim Y-S, et al. The fates of microbial populations on pig carcasses during slaughtering process, on retail cuts after slaughter, and intervention efficiency of lactic acid spraying. Int J Food Microbiol. (2019) 294:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.01.015

29. Lindblad M, Lindmark H, Lambertz ST, Lindqvist R. Microbiological baseline study of swine carcasses at swedish slaughterhouses. J Food Prot. (2007) 70:1790–7. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.8.1790

30. Bohaychuk VM, Gensler GE, Barrios PR. Microbiological baseline study of beef and pork carcasses from provincially inspected abattoirs in Alberta, Canada. Can Vet J. (2011) 52:1095–100.

31. Manios SG, Grivokostopoulos NC, Bikouli VC, Doultsos DA, Zilelidou EA, Gialitaki MA, et al. 3-year hygiene and safety monitoring of a meat processing plant which uses raw materials of global origin. Int J Food Microbiol. (2015) 209:60–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.12.028

32. Jakubowska-Gawlik K, Kolanowski W, Murali AP, Trafialek J. A comparison of food safety conformity between cattle and pig slaughterhouses. Food Control. (2022) 140:109143. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109143

33. Drummond N, Murphy BP, Ringwood T, Prentice MB, Buckley JF, Fanning S. Yersinia enterocolitica: a brief review of the issues relating to the zoonotic pathogen, public health challenges, and the pork production chain. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2012) 9:179–89. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0938

34. Bennett SD, Walsh KA, Gould LH. Foodborne disease outbreaks caused by Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus—United States, 1998–2008. Clin Infect Dis. (2013) 57:425–33. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit244

35. Heredia N, García S. Animals as sources of food-borne pathogens: a review. Anim Nutr. (2018) 4:250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2018.04.006

36. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Food Poisoning Statistics. (2023). Available online at: https://www.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/portal/healthyfoodlife/foodPoisoningStat.do?menu_no=4425&menu_grp=MENU_NEW02 (accessed January 20, 2023).

37. Peton V, Le Loir Y. Staphylococcus aureus in veterinary medicine. Infect Genet Evol. (2014) 21:602–15. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.011

38. Beneke B, Klees S, Stührenberg B, Fetsch A, Kraushaar B, Tenhagen B-A. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a fresh meat pork production chain. J Food Prot. (2011) 74:126–9. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-250

39. Komodromos D, Kotzamanidis C, Giantzi V, Angelidis AS, Zdragas A, Sergelidis D. Prevalence and biofilm-formation ability of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from livestock, carcasses, the environment, and workers of three abattoirs in Greece. J Hell Vet Med Soc. (2022) 73:4097–104. doi: 10.12681/jhvms.26469

40. Tanih NF, Sekwadi E, Ndip RN, Bessong PO. Detection of pathogenic Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus from cattle and pigs slaughtered in abattoirs in Vhembe District, South Africa. Sci World J. (2015) 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/195972

41. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Yersinia enterocolitica (Yersiniosis) (2016). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/yersinia/index.html (accessed January 18, 2023).

42. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The European Union One Health 2019 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. (2021) 19:6406. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6406

43. Bari ML, Hossain MA, Isshiki K, Ukuku D. Behavior of Yersinia enterocolitica in foods. J Pathog. (2011) 2011:1–13. doi: 10.4061/2011/420732

44. Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Stolle A, Stephan R. Prevalence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in pigs slaughtered at a Swiss abattoir. Int J Food Microbiol. (2007) 119:207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.050

45. Liang J, Wang X, Xiao Y, Cui Z, Xia S, Hao Q, et al. Prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica in pigs slaughtered in chinese abattoirs. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2012) 78:2949–56. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07893-11

46. Songer JG, Uzal FA. Clostridial enteric infections in pigs. J Vet Diagnostic Investig. (2005) 17:528–36. doi: 10.1177/104063870501700602

47. Driessen B, Freson L, Buyse J. Fasting finisher pigs before slaughter influences pork safety, pork quality and animal welfare. Animals. (2020) 10:2206. doi: 10.3390/ani10122206

48. Whyte P, McGill K, Cowley D, Madden R, Moran L, Scates P, et al. Occurrence of Campylobacter in retail foods in Ireland. Int J Food Microbiol. (2004) 95:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.10.018

49. Wieczorek K, Osek J. Characteristics and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter isolated from pig and cattle carcasses in Poland. Pol J Vet Sci. (2013) 16:501–8. doi: 10.2478/pjvs-2013-0070

50. Mechesso AF, Moon DC, Kim S-J, Song H-J, Kang HY, Na SH, et al. Nationwide surveillance on serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance profiles of non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars isolated from food-producing animals in South Korea. Int J Food Microbiol. (2020) 335:108893. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108893

51. Foley SL, Lynne AM, Nayak R. Salmonella challenges: prevalence in swine and poultry and potential pathogenicity of such isolates1,2. J Anim Sci. (2008) 86:E149–62. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0464

52. Trinetta V, Magossi G, Allard MW, Tallent SM, Brown EW, Lomonaco S. Characterization of Salmonella enterica isolates from selected us swine feed mills by whole-genome sequencing. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2020) 17:126–36. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2019.2701

53. Neoh H, Tan X-E, Sapri HF, Tan TL. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE): a review of the “gold standard” for bacteria typing and current alternatives. Infect Genet Evol. (2019) 74:103935. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103935

54. Cookson BD, Robinson DA, Monk AB, Murchan S, Deplano A, de Ryck R, et al. Evaluation of molecular typing methods in characterizing a european collection of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains: the HARMONY collection. J Clin Microbiol. (2007) 45:1830–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02402-06

55. Sun J, Yang M, Sreevatsan S, Davies PR. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in growing pigs in the USA. PLoS one. (2015) 10:e0143670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143670

56. Kang HY, Moon DC, Mechesso AF, Choi J-H, Kim S-J, Song H-J, et al. Emergence of CFR-mediated linezolid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from pig carcasses. Antibiotics. (2020) 9:769. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9110769

57. Bancerz-Kisiel A, Pieczywek M, Łada P, Szweda W. The most important virulence markers of Yersinia enterocolitica and their role during infection. Genes (Basel). (2018) 9:235. doi: 10.3390/genes9050235

58. Laukkanen R, Martínez PO, Siekkinen K-M, Ranta J, Maijala R, Korkeala H. Contamination of carcasses with human pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica 4/O:3 originates from pigs infected on farms. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2009) 6:681–8. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0265

59. Vasquez MT, Lubkin A, Reyes-Robles T, Day CJ, Lacey KA, Jennings MP, et al. Identification of a domain critical for Staphylococcus aureus LukED receptor targeting and lysis of erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. (2020) 295:17241–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015757

60. Varshney AK, Mediavilla JR, Robiou N, Guh A, Wang X, Gialanella P, et al. Diverse enterotoxin gene profiles among clonal complexes of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the Bronx, New York. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2009) 75:6839–49. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00272-09

61. Moon BY, Park JY, Hwang SY, Robinson DA, Thomas JC, Fitzgerald JR, et al. Phage-mediated horizontal transfer of a Staphylococcus aureus virulence-associated genomic island. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:9784. doi: 10.1038/srep09784

62. Fois F, Piras F, Torpdahl M, Mazza R, Ladu D, Consolati SG, et al. Prevalence, bioserotyping and antibiotic resistance of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica detected in pigs at slaughter in Sardinia. Int J Food Microbiol. (2018) 283:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.010

63. Bonardi S, Bassi L, Brindani F, D'Incau M, Barco L, Carra E, et al. Prevalence, characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella enterica and Yersinia enterocolitica in pigs at slaughter in Italy. Int J Food Microbiol. (2013) 163:248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.02.012

Keywords: foodborne pathogen, pig, carcass, slaughterhouse, microbial quality

Citation: Hong S, Kang HJ, Lee H-Y, Jung H-R, Moon J-S, Yoon S-S, Kim H-Y and Lee YJ (2023) Prevalence and characteristics of foodborne pathogens from slaughtered pig carcasses in Korea. Front. Vet. Sci. 10:1158196. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1158196

Received: 03 February 2023; Accepted: 14 March 2023;

Published: 31 March 2023.

Edited by:

Om P. Dhungyel, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Piera Anna Martino, University of Milan, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Hong, Kang, Lee, Jung, Moon, Yoon, Kim and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ha-Young Kim, a2ltaHlAa29yZWEua3I=; Young Ju Lee, eW91bmdqdUBrbnUuYWMua3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.