- 1School of Agriculture, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Ruminant Molecular Cell Breeding, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Yinchuan, China

Bovine mastitis is an inflammatory response of mammary glands caused by pathogenic microorganisms such as Escherichia coli (E. coli). As a key virulence factor of E. coli, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) triggers innate immune responses via activation of the toll-like-receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway. However, the molecular regulatory network of LPS-induced bovine mastitis has yet to be fully mapped. In this study, bovine mammary epithelial cell lines MAC-T were exposed to LPS for 0, 6 and 12 h to assess the expression profiles of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) using RNA-seq. Differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) were filtered out of the raw data for subsequent analyses. A total of 2,257 lncRNAs, including 210 annotated and 2047 novel lncRNAs were detected in all samples. A large proportion of lncRNAs were present in a high abundance, and 112 DElncRNAs were screened out at different time points. Compared with 0 h, there were 22 up- and 25 down-regulated lncRNAs in the 6 h of post-infection (hpi) group, and 27 up- and 22 down-regulated lncRNAs in the 12 hpi group. Compared with the 6 hpi group, 32 lncRNAs were up-regulated and 25 lncRNAs were down-regulated in the 12 hpi group. These DElncRNAs are involved in the regulation of a variety of immune-related processes including inflammatory responses bMECs exposed to LPS. Furthermore, lncRNA TCONS_00039271 and TCONS_00139850 were respectively significance down- and up-regulated, and their target genes involve in regulating inflammation-related signaling pathways (i.e.,Notch, NF-κB, MAPK, PI3K-Akt and mTOR signaling pathway), thereby regulating the occurrence and development of E. coli mastitis. This study provides a resource for lncRNA research on the molecular regulation of bovine mastitis

Introduction

Mastitis is one of the most common diseases in dairy cows worldwide, causing damage to mammary tissue, reduces milk production, decreases the quality of dairy products, and increases mortality and culling rates (1, 2). Although mastitis is a common disease, it is both expensive and difficult to treat, resulting in huge losses in the dairy industry (3–5). Mammary gland inflammation is primarily a response to an infectious process (2, 6, 7), with Escherichia coli (E. coli) being a prominent etiologic agent (7, 8). When E. coli infects host cells, lipopolysaccharide (LPS, a pathogen-associated molecular pattern) (3, 9) is recognized by toll-like-receptor 4 (TLR4) which triggers immune responses, thus acting as an early signal of pathogenic microbial infection (8, 10). This leads to activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and induction of the expression of several pro-inflammatory genes, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (11).

With the advances and popularization in omics technologies in recent decades, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and its functions have been mined. lncRNAs, a novel class of transcripts over 200 nucleotides (nt) in length, are located in the nucleus or cytoplasm and cannot encode proteins (12–14). However, it has been suggested that some lncRNAs can form small peptides which affect biological functions (13, 15), participate in inflammatory responses, and regulate the occurrence and development of a variety of diseases (11, 16, 17). At present, an increasing number of studies have shown that lncRNAs also exert significant regulatory effects in the process of bovine mastitis (16, 18, 19). However, few studies on the regulatory mechanisms in dairy cows have been reported in the literature, and this is a critical shortcoming.

This study aimed to detect the expression profile of lncRNAs and elucidate differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) associated with LPS-induced inflammation in bovine mammary epithelial cells (bMECs) in vitro. It is hoped that this study can establish a potential molecular regulatory mechanism of dairy cow mastitis to serve as a reference for dairy cattle genetic breeding and to promote the improvement of dairy cow breeding.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and in vitro Mastitis Model

The previously frozen bovine mammary epithelial cell lines MAC-T (20) in liquid nitrogen were thawed and cultured in three 6-well plates supplemented with Dubecco's modified Eagle medium/ F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). When bMEC monolayers reached 80% confluence, one 6-well plate cells (0 h) were collected as the control group, and the remaining two 6-well plates were treated with 50 ng/μL LPS to stimulate an inflammatory response (21). The respective 6-well plates were collected at 6 and 12 hpi as the experimental groups.

RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from bMECs induced with LPS at 0, 6, and 12 h using TRizol reagent (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of RNA was evaluated by Agarose Gel Electrophoresis, NanoDrop (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and Agilent 2,100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to ensure the use of qualified samples for sequencing. Subsequently, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was depleted from total RNA using the Epicentre Ribo-zero™ (rRNA) Removal Kit (Epicentre, Madsion, WI, USA). Preparation of the RNA sequencing library construction was prepared as previously reported (22), that is, RNA library for RNA-seq was prepared as rRNA depletion and stranded method. Then the library concentration was preliminarily tested using Qubit 2.0, and was adjusted to 1.0 ng/μL. Afterwards, the Agilent 2,100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA)was used to measure insert sizes of the acquired library. To ensure library quality, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to accurately determine the library effective concentration (>3 nM). After qualification of the library, the Illumina PE150 platform was used for sequencing according to the library effective concentration and the pooling of data output requirements.

Quality Control and Mapping of Sequencing Data

The raw data (raw reads) containing a small number of reads with sequencing adapters or with low sequencing quality was obtained by RNA-seq. For the reliability of the data analysis, it was necessary to filter the raw data using the following parameters: (1) reads with adapter were removed; (2) unidentifiable base information reads with a ratio of > 0.002 were removed; (3) the paired reads were removed when the number of low-mass bases in single-end read was more than 50% of the read length ratio. The obtained clean reads were mapped to the internal reference genome (Bos taurus Ensembl 97) by using Hisat2 (23).

lncRNA Identification

In this study, all the transcripts were merged using Cuffmerge software. LncRNAs were identified according to their structural and functional characteristics. The criteria used to identify the lncRNAs were as follows: (1) transcripts with exon numbers ≥ 2 and lengths > 200 bp were selected; (2) transcript fragments per kilobase per million reads (FPKM) > 0.5 were selected; (3) transcripts that overlap with the database annotation exon regions were identified using the Cuffcompare software (v2.2.1); (4) candidate data sets of novel lncRNAs were obtained through potential coding identification. Then, the final identification and naming were performed to obtain the novel lncRNAs of this analysis according to their loci relative to the coding genes (24).

Quantification of lncRNA Expression Levels and Differential Expression Analysis

Quantification of lncRNAs was performed using the StringTie software (v1.3.3). The expression level of each transcript was calculated according to the frequency of clean reads. The data were subsequently normalized to the FPKM (25), using the following formula:

Differential expression analyses between two groups were conducted using the Cuffdiff software (v2.1.1). The DElncRNAs were identified using || > 1 and P < 0.05 as standard.

Validation of RNA-Seq by qRT-PCR

To verify the sequencing results, 10 DElncRNAs were randomly selected to detect their relative expression levels by qRT-PCR. Total RNA extracted by using the Trizol reagent was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The qRT-PCR was performed using 2 × M5 HiPer SYBR Premix Es Taq (with Til RNaseH) kit (Mei5 Biotechnology, Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 qRT-PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) to analyze the relative expression level of DElncRNAs. The qRT-PCR reaction consisted of the following components: 10.0 μL 2 × M5 HiPer SYBR Premix Es Taq (with Til RNaseH), 0.4 μL Forward Primer, 0.4 μL Reverse Prime, 1.5 μL cDNA template and 7.7 μL RNase-Free ddH2O. The qRT-PCR amplification conditions were as follows: at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s followed by annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s. The qRT-PCR primers for DElncRNAs were designed with Primer Premier 5 (PREMIER Biosoft international, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The primer sequences are presented in Supplementary Table 1. For each sample, 3 biological replicates were amplified. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and ribosomal protein S18 (RPS18) genes were used as internal references (26), and the relative expression of DElncRNAs was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

The qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data were compared with each other. When the expression trends of qRT-PCR and RNA-seq were consistent, the DElncRNA identification was considered to be reliable.

Target Gene Prediction and Functional Analysis of DElncRNAs

To explore the potential function of DElncRNAs, target genes of the DElncRNAs were predicted as being either cis-acting and trans-acting. For cis-acting target (co-location) prediction, genes that co-localized to within 100 kb up-or down-stream of a lncRNA were considered to be a cis-acting target (27). For trans-acting target (co-expression) prediction, the Pearson's correlation coefficients between the coding genes and lncRNAs were calculated and analyzed for the identification of trans-acting regulatory elements. This analysis required the sample size was > 5, and a Pearson's correlation coefficient > 0.95 for a gene to be considered a target of the lncRNA (28). Then, Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis of target genes of DElncRNAs was implemented by the cluster Profiler R package (R-3.2.4), in which gene length bias was corrected (29).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. Significant differences were analyzed using Student's t-test, and P < 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference and P < 0.01 was extremely significant. The experimental data were presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

RNA-Seq of lncRNAs

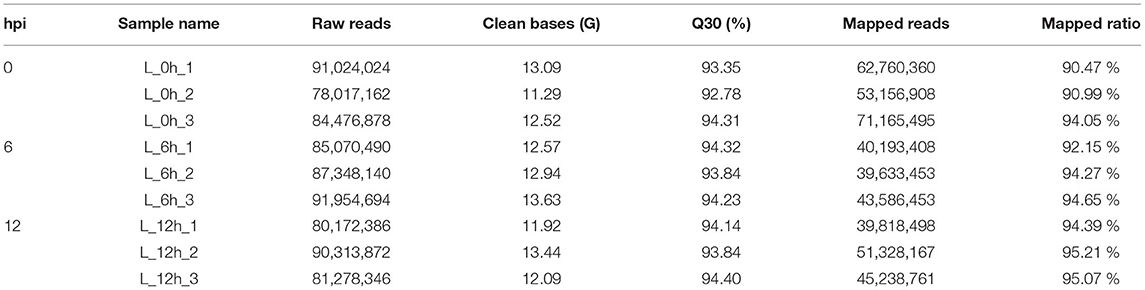

Nine lncRNA libraries were sequenced using the Illumina PE150 to acquire raw data for quality control, and to extract high-quality clean reads (Table 1). In addition, the Hisat2 software (v2.0.5) was used to compare the clean reads to the reference genome for statistical analysis. For each sample, the clean bases (G) should be ≥ 11.29 G and the Q30 (%) should be ≥ 92.78% to ensure the reliability of results obtained from subsequent analyses. Additional details are provided in Table 1.

Identification and Classification of lncRNAs

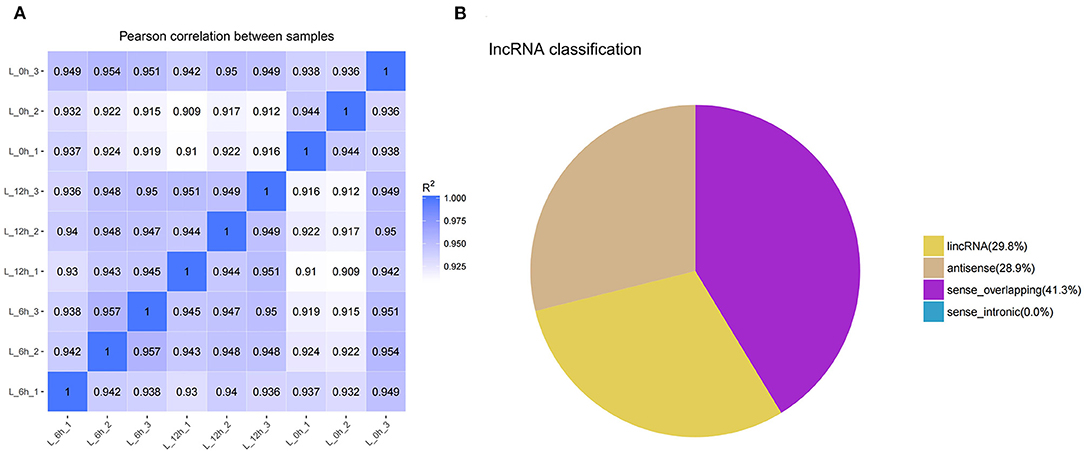

In this study, the correlation of expression levels between samples was determined to ensure the confidence and rationality of the experiment (Figure 1A). Through analysis of the sequencing data, a total of 2,257 lncRNAs were identified, including 210 annotated and 2,047 novel. Novel lncRNAs were classified as intergenic lncRNA (lincRNA, 29.8%), antisense lncRNA (antisense, 28.9%), and sense overlapping (41.3%) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Identification and classification of lncRNA detected in bMECs. (A) Pearson's correlation coefficients between samples. (B) The types of novel lncRNAs. L_0h is presented that MAC-T were exposed to LPS for 0 h (0 h); L_6h is presented as 6 hpi; L_12h is presented as 12 hpi. (similarly hereinafter).

Profile of lncRNA Expression in LPS Treated bMECs

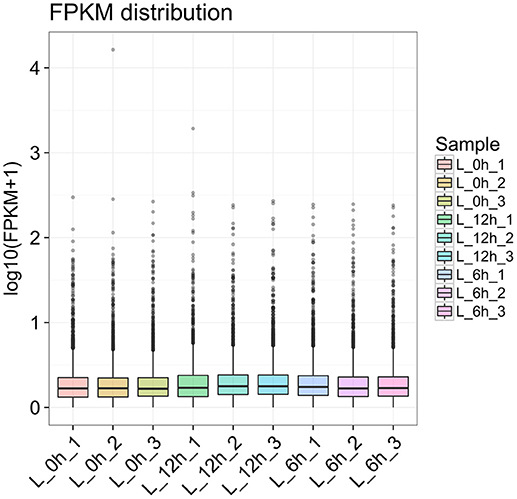

To further detect the expression of lncRNA in LPS treated bMECs, cells were incubated for 0, 6, and 12 h following treatment for high-throughput sequencing. In each sample, box-plot diagrams were constructed based on FPKM to observe the expression symmetry and distribution of all lncRNAs. The results showed that the distribution of each box-plot was flat (Figure 2), which indicated that the expression distribution of lncRNA in each sample was correct. At the same time, it can be seen that the distribution of lncRNA expression levels in samples between groups were similar, but small differences were observed.

Differential Expression Analysis of lncRNA

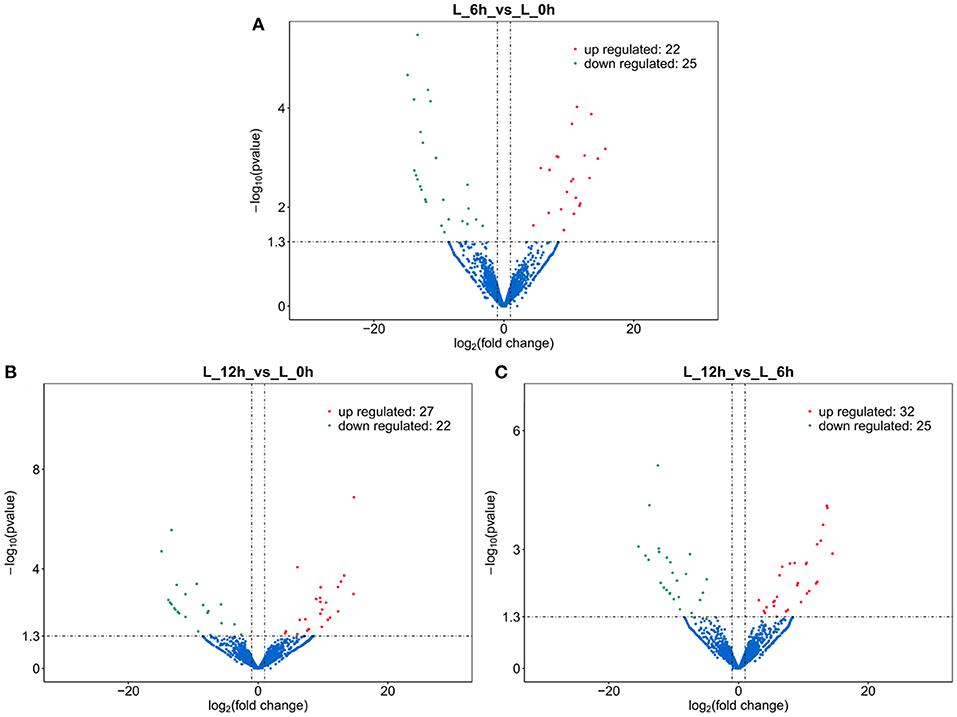

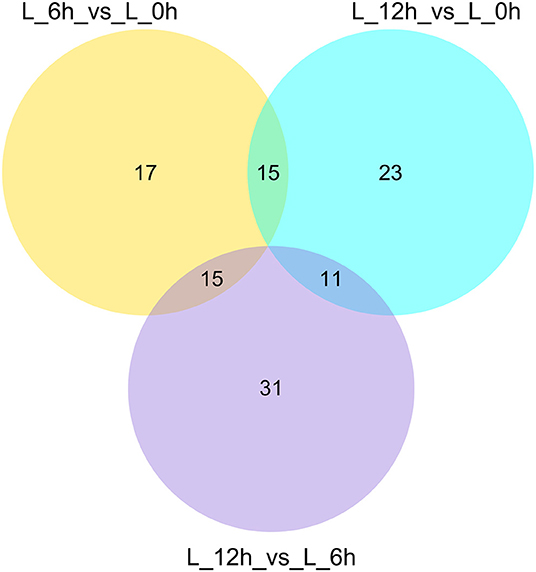

A total of 112 DElncRNAs were observed between the 3 experimental groups. Relative to the 0 h group, there were 22 up- and 25 down-regulated DElncRNAs in the 6 hpi group (Supplementary Table 2; Figure 3A), and 27 up- and 22 down-regulated DElncRNAs in the 12 hpi group (Supplementary Table 3; Figure 3B). Compared with the 6 hpi group, 32 up- and 25 down-regulated DElncRNAs were observed in the 12 hpi group (Supplementary Table 4; Figure 3C). Moreover, among the 3 groups, a total of 17, 23 and 31 specific DElncRNAs were observed in 6 vs. 0 hpi, 12 vs. 0 hpi, and 12 vs. 6 hpi groups by Venn diagram analyses, respectively (Figure 4). It is worth noting that lncRNA TCONS_00039271 was highly expressed and significantly down-regulated ( = −1.9) at 12 hpi relative to 0 h. Meanwhile, lncRNA TCONS_00139850 was not detected in the 0 h and 6 hpi group and was significantly up-regulated ( = 15.94) in the 0 h and 12 hpi group. The results indicated that these DElncRNA may play an important role in the regulation of the inflammatory response following LPS treatment of bMECs.

Validation of RNA-Seq Results by qRT-PCR

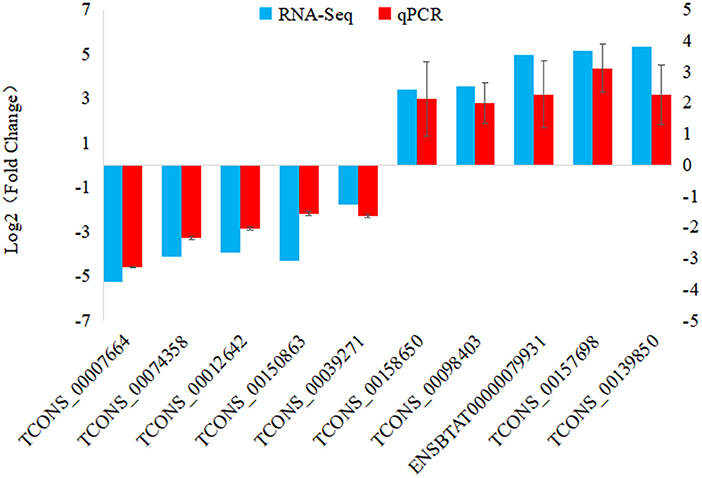

To verify the accuracy and reliability of the RNA-seq data, a total of 10 DElncRNAs were randomly selected for expression level analysis by qRT-PCR. Comparing the qRT-PCR results with the RNA-seq results, as shown in Figure 5, the data obtained by the two methods yielded similar patterns, indicating that the screened DElncRNAs based on RNA-seq were reliable.

Figure 5. qRT-PCR validation of DElncRNAs. 10 DElncRNAs were used for qRT-PCR validation, with TCONS_00074358 from 6 hpi VS. 0 h comparison; TCONS_00012642, TCONS_00150863, TCONS_00039271, ENSBTAT00000079931, TCONS_00157698 and TCONS_00139850 from 12 hpi VS. 0 h comparison; TCONS_00007664, TCONS_00158650 and TCONS_00098403 from 12 hpi VS. 6 hpi comparison.

Target Gene Prediction and Functional Analysis of DElncRNAs

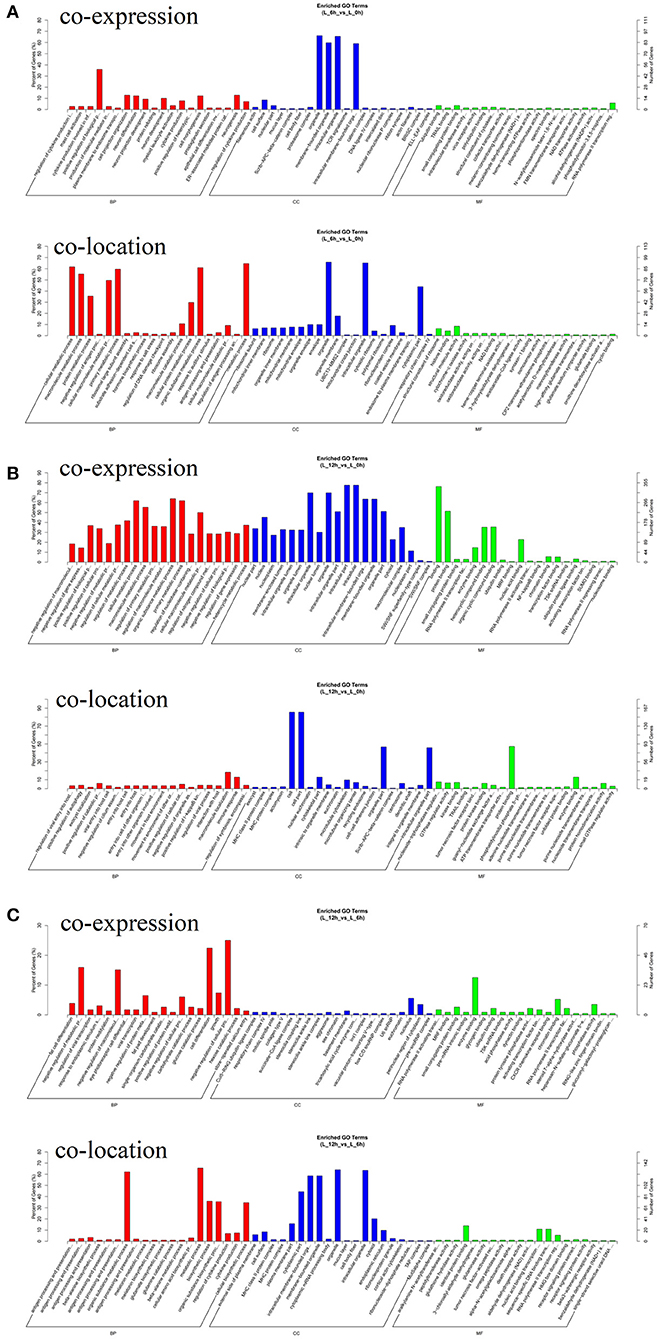

To further investigate the physiological and molecular functions of DElncRNAs on inflammatory reactions in bMECs, or more generally, the pathogenesis of bovine mastitis, possible target genes of DElncRNAs were predicted via co-location and co-expression methods (27, 28). The prediction results of target genes showed that 112 DElncRNAs may have 1,042 target genes. The results of GO enrichment showed that these target genes were involved in the regulation of various biological processes such as inflammatory response, immune response, stress response and regulation of cytokine production (Figure 6). Hence, it can be speculated that these DElncRNAs may participate in the inflammatory response by regulating their target genes during LPS-induced inflammatory response of bMECs.

Figure 6. GO enrichment analysis of target genes for DElncRNA. (A) Functional enrichment analysis of DElncRNAs at 6 hpi compared to 0 h. (B) Functional enrichment analysis of DElncRNAs at 12 hpi compared to 0 h. (C) Functional enrichment analysis of DElncRNAs at 12 hpi compared to 6 hpi.

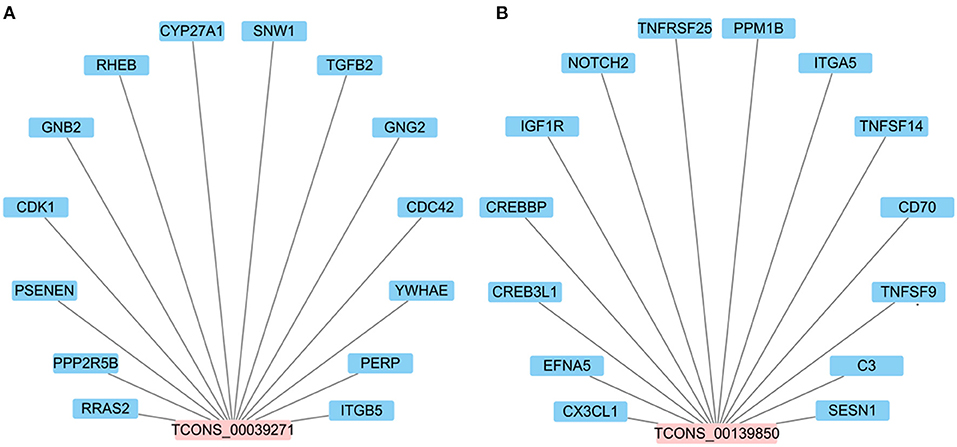

It is worth noting that TCONS_00039271 and TCONS_00139850 were stably down- and up-regulated, respectively. Constructing the network between lncRNAs and target genes indicated that each DElncRNA possibly targets approximately14 genes (such as NOTCH2, TNFSF14, CDC42, GNG2, RHEB and ITGA5) (Figure 7; Supplementary Table 5). Previous studies have shown that these target genes involved in inflammatory pathways including the Notch (30), NF-κB (31). MAPK (32), chemokine (33), mTOR (34) and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways (34, 35). In addition, Li et al. (30) and Zhao et al. (36) respectively reported that lncRNA DLEU2 and lncRNA LINC01410 can elevate the expression of NOTCH2 to stimulate Notch signaling pathway, thereby boosting cell proliferation and hindering cell apoptosis. Taken together, the data suggest that lncRNA TCONS_00139850 and TCONS_00039271 might play a role in regulating the inflammatory response of bMECs via their target genes (Figure 7; Supplementary Table 5). As such, these lncRNAs and their target genes will be the focus of future research on the molecular mechanism of mammary inflammation-related lncRNAs.

Figure 7. The interaction network between candidate DElncRNAs. (A) The potential target genes of lncRNA TCONS_00039271. (B) The potential target genes of lncRNA TCONS_00139850.

Discussion

Cow mastitis is an inflammatory disease of mammary tissue. Often, it is caused by the invasion and proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms, physical damage, chemical stimulation and the cow's immune response (1, 2, 37). However, among these causes, E. coli is the most common culprit (38, 39). When E. coli successfully penetrate the mammary gland through the physical barrier of the teat end, it causes an inflammatory response in the mammary gland (38, 40). This colonization leads to rapid changes in the expression levels of immune-related genes, resulting in the inflammatory process (41, 42). In addition, it has been reported that lncRNAs play an important role in pathogen-induced acute and chronic inflammation by regulating the expression of specific genes (43). Therefore, it is extremely necessary to study the DElncRNAs in bovine inflammatory or disease states.

In the past decade, based on the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technology, an increasing number of studies have reported that lncRNAs are widely present in eukaryotes, especially mammals, and that lncRNAs play an important role in the pathogenesis of many diseases such as cancer and immunodeficiency (44–46). In recent years, a large number of animal and human DElncRNAs have been screened for their possible regulatory functions (47, 48). However, as far as bovine mastitis is concerned, few studies have examined the role of DElncRNAs in bovine mastitis using RNA-seq (16, 18). For example, Wang et al. (16) found 53 DElncRNAs in E. coli and S. aureus-treated MAC-T cells after 24 h. Wang et al. (18) also identified 21 DElncRNAs from S. aureus-treated bMECs after just 2 h. Based on previous reports (7, 14, 16, 42), the expression of lncRNAs in the inflammatory response of bMECs are not always consistent. The reason may be that the process of cow mastitis is a complex process and the changes in expression of many genes, including lncRNA, may be related to the duration of infection. Therefore, RNA-seq was used here to detect the differential expression of lncRNA in bMECs induced by LPS to clarify the role of lncRNA in the process of bovine mastitis. A total of 2,257 lncRNAs and 112 DElncRNAs were observed in bMECs exposed to LPS at 0, 6 and 12 h. By comparing the results of this experiment with the existing literature (16), differences in the type and expression levels of lncRNAs at different times of induction were observed. Thus, it is likely that lncRNAs are involved in the regulation of inflammation and potentially the process of bovine mammary gland inflammation.

To elucidate the potential functions of DElncRNAs, target gene prediction and GO functional enrichment analysis of DElncRNAs revealed that 112 DElncRNAs in LPS-induced bMECs might regulate the expression of 1,042 target genes belonging to several significant signaling pathways. Some such pathways include NF-κB, AMPK, PI3K-Akt, mTOR and MAPK, which participate in the regulation of cytokine production, inflammatory responses and immune responses (31, 32, 34, 35, 49, 50). At the same time, previous studies have shown that the above signaling pathways are closely related to the occurrence, development, and regulation of mastitis (7, 51–53). Additionally, LPS can activate TLR4 and initiate the innate immune and inflammatory response through the activation of NF-κB and MAPK in mammary epithelial cells (54, 55), which induce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (56). Liu et al. (57) showed that lncRNA RP11-490M8.1 could reduce LPS-induced pyroptosis via TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Furthermore, Zhao et al. (58) found that lncRNA UCA1 could accelerate cell viability, block apoptosis and function as competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) to target TLR4 by sponging miR-499b-5p, thereby alleviating the LPS-challenged cell damage. Based on above results, it was speculated that these DElncRNAs are likely involved in regulating the process of bovine mastitis via their immune-related target genes (7, 59–62).

Based on the data presented here in combination with the literature discussed above, it is clear that further examination of the lncRNA expression profile in mastitis models is needed to clarify molecular mechanisms in regulating the inflammatory process. Unfortunately, there are few reports investigating the role of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of bovine mastitis. So far, only four lncRNAs, including XIST (7), LRRC75A-AS1 (14), TUB (16) and H19 (42), have been studied. It was reported that lncRNA XIST can significantly inhibit E. coli or S. aureus-induced inflammatory responses in bMECs through the NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (7). It was observed here that changes in expression of lncRNA TCONS_00039271 and TCONS_00139850 at 0 vs. 12 hpi group were opposite. In order to explore their potential functions, target genes predicted via co-location and co-expression showed that lncRNA TCONS_00039271 might regulate TGFB2 and CDC42 (Supplementary Table 5). In mammals, TGFB1 and TGFB2 have highly homologous, which can activate the same downstream signaling pathways (63). Increasing studies have showed that TGF? can moderate immune and inflammatory responses in mammary gland development (63, 64). It has been reported that TGFB2 is involved in regulating apoptosis and inflammatory responses in bMECs (65). Meanwhile, Yang et al. (66) showed that highly expressed lncRNA H19 in inflammatory MAC-T cells and bovine mammary tissue can mediate TGFB2-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurance and extracellular matrix (ECM) protein excessive synthesis through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to aggravate inflammation. Moreover, the CDC42 gene also plays an important role in the inflammatory response (67, 68). In addition, for lncRNA TCONS_00139850, a total of 14 potential target genes involved in immunity, such as CX3CL1 and NOTCH2 were identified (Supplementary Table 5). Previous studies have reported that CX3CL1 (69) and NOTCH2 (70) can participate in inflammatory responses as master regulators. Based on the results of the above analysis, it was concluded that lncRNA TCONS_00039271 and TCONS_00139850 might be involved in the inflammatory response of LPS-initiated mastitis.

In brief, high-throughput sequencing, in concert with previous studies (16), has shown that DElncRNAs might play a crucial role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses via regulating their target genes to involve in inflammation-related signaling pathways. Therefore, in-depth exploration and comprehensive studies of the molecular structure and regulatory processes of DElncRNAs will help to further reveal the differences in the development of bovine mastitis.

Conclusion

Abundant lncRNAs were expressed in LPS-induced bMECs. A total of 112 DElncRNAs were identified following different lengths of exposure to LPS. These DElncRNAs might be involved in the regulation of immune and inflammation responses in vivo via several significant signaling pathways including NF-κB, AMPK, PI3K-Akt, mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. In addition, lncRNA TCONS_00039271 and TCONS_00139850 were stably down- and up-regulated, respectively, and they might act as key regulators of cow mastitis caused by E. coli. This study lays a foundation for further research on the molecular regulation of bovine mastitis, and provides a reference for genetic traits desirable to breeding efforts in the control of mastitis in dairy cows.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: GEO DATABASE (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE181658).

Author Contributions

J-PW, X-PW, and Z-ML designed the experiments. J-PW and Q-CH completed the experiments. J-PW, X-PW, Z-ML, and JY analyzed the data. J-PW drafted the paper. J-PW, X-PW, Z-ML, YM, and D-WW revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 32060749 and 32172709), Project of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Key Research and Development Program (Special Talent Introduction) (Grant No. 2019BEB04002), Scientific Research Project of Ningxia Higher Education Institutions (Grant No. NGY2020007), and Research Initiation Project of Talent Introduction of Ningxia University (Grant No. 030900002151).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their sincere appreciation to MogoEdit professional English editing company (Mogo Internet Technology Co., LTD, Shaanxi, China) for English language editing.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.758488/full#supplementary-material

References

1. LuoReng ZM, Yang J, Wang XP, Wei DW, Zan LS. Expression profiling of microRNA from peripheral blood of dairy cows in response to Staphylococcus aureus-infected mastitis. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:691196. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.691196

2. Ashraf A, Imran M. Causes, types, etiological agents, prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, effects on human health and future aspects of bovine mastitis. Anim Health Res Rev. (2020) 21:36–49. doi: 10.1017/S1466252319000094

3. Xu T, Deng RZ, Li XZ, Zhang Y, Gao MQ. RNA-seq analysis of different inflammatory reactions induced by lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. (2019) 130:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.03.015

4. Firth LC, Laubichler C, Schleicher C, Fuchs K, Kasbohrer A, Egger-Danner C, et al. Relationship between the probability of veterinary-diagnosed bovine mastitis occurring and farm management risk factors on small dairy farms in Austria. J Dairy Sci. (2019) 102:4452–63. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15657

5. Cai MC, Fan WQ, Li XY, Sun HC, Dai LL, Lei DF, et al. The regulation of Staphylococcus aureus-induced inflammatory responses in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8: 683886. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.683886

6. Keane OM. Symposium review: intramammary infections-major pathogens and strain-associated complexity. J Dairy Sci. (2019) 102:4713–26. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15326

7. Ma MR, Pei YF, Wang XX, Feng JX, Zhang Y, Gao MQ. LncRNA XIST mediates bovine mammary epithelial cell inflammatory response via NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Cell Prolif. (2019) 52:e12525. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12525

8. Fu YH, Zhou ES, Liu ZC, Li FY, Liang DJ, Liu B, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli elicit different innate immune responses from bovine mammary epithelial cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2013) 155:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2013.08.003

9. Tsugami Y, Wakasa H, Kawahara M, Nishimura T, Kobayashi K. Lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid influence milk production ability via different early responses in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. (2021) 400:112472. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112472

10. Park BS, Lee JO. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp Mol Med. (2013) 45:e66. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.97

11. Nakayama Y, Fujiu K, Yuki R, Oishi Y, Morioka MS, Isagawa T, et al. A long noncoding RNA regulates inflammation resolution by mouse macrophages through fatty acid oxidation activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:14365–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005924117

12. Jiang R, Li H, Huang YZ, Lan XY, Lei CZ, Chen H. Transcriptome profiling of lncRNA related to fat tissues of Qinchuan cattle. Gene. (2020) 742:144587. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144587

13. Choi SW, Kim HW, Nam JW. The small peptide world in long noncoding RNAs. Brief Bioinform. (2019) 20:1853–64. doi: 10.1093/bib/bby055

14. Wang XX, Wang H, Zhang RQ, Li D, Gao MQ. LRRC75A antisense lncRNA1 knockout attenuates inflammatory responses of bovine mammary epithelial cells. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:251–63. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.38214

15. Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, Winders BR, Troupes CD, Wu FF, et al. A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle. Science. (2016) 351:271–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4076

16. Wang H, Wang XX, Li XR, Wang QW, Qing SZ, Zhang Y, et al. A novel long non-coding RNA regulates the immune response in MAC-T cells and contributes to bovine mastitis. FEBS J. (2019) 286:1780–95. doi: 10.1111/febs.14783

17. Zheng J, Zeng PY, Zhang HT, Zhou YY, Liao J, Zhu WP, et al. Long noncoding RNA ZFAS1 silencing alleviates rheumatoid arthritis via blocking miR-296-5p-mediated down-regulation of MMP-15. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 90:107061. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107061

18. Wang XZ, Su F, Yu XH, Geng N, Li LP, Wang R, et al. RNA-Seq whole transcriptome analysis of bovine mammary epithelial cells in response to intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:642. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00642

19. Ozdemir S, Altun S. Genome-wide analysis of mRNAs and lncRNAs in Mycoplasma bovis infected and non-infected bovine mammary gland tissues. Mol Cell Probes. (2020) 50:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2020.101512

20. Huynh HT, Robitaille G, Turner JD. Establishment of bovine mammary epithelial cells (MAC-T): an in vitro model for bovine lactation. Exp Cell Res. (1991) 197:91–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90422-Q

21. Wang XP, Luoreng ZM, Zan LS, Li F, Li N. Bovine miR-146a regulates inflammatory cytokines of bovine mammary epithelial cells via targeting the TRAF6 gene. J Dairy Sci. (2017) 100:7648–58. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-12630

22. Parkhomchuk D, Borodina T, Amstislavskiy V, Banaru M, Hallen L, Krobitsch S, et al. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. (2009) 37:e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp596

23. Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL, HISAT. A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. (2015) 12:357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317

24. Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for the ENCODE project. Genome Res. (2012) 22:1760–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111

25. Zhou ZX, Chen XM, Zhang YQ, Peng L, Xue XY, Li GX. Comprehensive analysis of long noncoding RNA and mRNA in five colorectal cancer tissues and five normal tissues. Biosci Rep. (2020) 40:BSR20191139. doi: 10.1042/BSR20191139

26. Bougarn S, Cunha P, Gilbert FB, Meurens F, Rainard P. Technical note: validation of candidate reference genes for normalization of quantitative PCR in bovine mammary epithelial cells responding to inflammatory stimuli. J Dairy Sci. (2011) 94:2425–30. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3859

27. Bao ZY, Yang Z, Huang Z, Zhou YR, Cui QH. Dong D. LncRNADisease 20: an updated database of long non-coding RNA-associated diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:D1034–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky905

28. Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. (2018) 172:393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011

29. Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. (2010) 11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14

30. Li GC, Zhang Z, Chen ZS, Liu B, Wu HL. LncRNA DLEU2 is activated by STAT1 and induces gastric cancer development via targeting miR-23b-3p/NOTCH2 axis and notch signaling pathway. Life Sci. (2021) 277:119419. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119419

31. Dignazio L, Batie M, Rocha S. TNFSF14/LIGHT, a non-canonical NF-κB stimulus, induces the HIF pathway. Cells. (2018) 7:102. doi: 10.3390/cells7080102

32. Zhang X, Bandyopadhyay S, Araujo LP, Tong K, Flores J, Laubitz D, et al. Elevating EGFR-MAPK program by a nonconventional cdc42 enhances intestinal epithelial survival and regeneration. JCI Insight. (2020) 5:e135923. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.135923

33. Gan SJ, Pan YQ, Mao JQ. MiR-30a-GNG2 and miR-15b-ACSS2 interaction pairs may be potentially crucial for development of abdominal aortic aneurysm by influencing inflammation. DNA Cell Biol. (2019) 38:1540–56. doi: 10.1089/dna.2019.4994

34. Aoki M, Fujishita T. Oncogenic roles of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. (2017) 407:153–89. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_6

35. Xu F, Zhou FC. Inhibition of microRNA-92a ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction by targeting ITGA5 through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. (2020) 78:106060. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106060

36. Zhao XL, Shen FZ, Yang B. LncRNA LINC01410 induced by MYC accelerates glioma progression via sponging miR-506-3p and modulating NOTCH2 expression to motivate Notch signaling pathway. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s10571-021-01042-1. [Epub ahead of print].

37. Chen L, Liu XL, Li ZX, Wang HL, Liu Y, He H, et al. Expression differences of miRNAs and genes on NF-κB pathway between the healthy and the mastitis Chinese Holstein cows. Gene. (2014) 545:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.071

38. Yang GY, Yue Y, Li D, Duan C, Qiu XQ, Zou YJ, et al. Antibacterial and immunomodulatory effects of pheromonicin-NM on Escherichia coli-challenged bovine mammary epithelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. (2020) 84:106569. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106569

39. Zhang J, Jiang Y, Xia X, Wu J, Almeida R, Eda S, et al. An on-site, highly specific immunosensor for Escherichia coli detection in field milk samples from mastitis-affected dairy cattle. Biosens Bioelectron. (2020) 165:112366. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112366

40. Sordillo LM. Mammary gland immunobiology and resistance to mastitis. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. (2018) 34:507–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2018.07.005

41. Chen Z, Zhang Y, Zhou JP, Lu L, Wang XL, Liang YS, et al. Tea tree oil prevents mastitis-associated inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated bovine mammary epithelial cells. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:496. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00496

42. Li XZ, Wang H, Zhang YF, Zhang JJ, Qi SP, Zhang Y, et al. Overexpression of lncRNA H19 changes basic characteristics and affects immune response of bovine mammary epithelial cells. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e6715. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6715

43. Carpenter S, Fitzgerald KA. Transcription of inflammatory genes: long noncoding RNA and beyond. J Interferon Cytokine Res. (2015) 35:79–88. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0120

44. Yousefi H, Maheronnaghsh M, Molaei F, Mashouri L, Aref AR, Momeny M, et al. Long noncoding RNAs and exosomal lncRNAs: classification, and mechanisms in breast cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Oncogene. (2020) 39:953–74. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1040-y

45. Lin YH. Crosstalk of lncRNA and cellular metabolism and their regulatory mechanism in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:2947. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082947

46. Atianand MK, Caffrey DR, Fitzgerald KA. Immunobiology of long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Immunol. (2017) 35:177–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055459

47. Kornienko AE, Guenzl PM, Barlow DP, Pauler FM. Gene regulation by the act of long non-coding RNA transcription. BMC Biol. (2013) 11:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-59

48. Liu XF, Ding XB, Li X, Jin CF, Yue YW, Li GP, et al. An atlas and analysis of bovine skeletal muscle long noncoding RNAs. Anim Genet. (2017) 48:278–86. doi: 10.1111/age.12539

49. Yu X, Feng BM, He P, Shan LB. From chaos to harmony: responses and signaling upon microbial pattern rrecognition. Annu Rev Phytopathol. (2017) 55:109–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035649

50. Van Nostrand JL, Hellberg K, Luo EC, Van Nostrand EL, Dayn A, Yu JT, et al. AMPK regulation of raptor and TSC2 mediate metformin effects on transcriptional control of anabolism and inflammation. Genes Dev. (2020) 34:1330–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.339895.120

51. Arbab AAI, Lu XB, Abdalla IM, Idris AA, Chen Z, Li MX, et al. Metformin inhibits lipoteichoic acid-induced oxidative stress and inflammation through AMPK/NRF2/NF-KappaB signaling pathway in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:661380. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.661380

52. Han S, Li XL, Liu J, Zou ZW, Luo L, Wu R, et al. Bta-miR-223 targeting CBLB contributes to resistance to Staphylococcus aureus mastitis through the PI3K/AKT/NF-kappaB pathway. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:529. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00529

53. Zhang YH, Xu YQ, Chen BW, Zhao B, Gao XJ. Selenium deficiency promotes oxidative stress-induced mastitis via activating the NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways in dairy cow. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02882-0

54. Yang YX, Ran X, Wang HF, Chen YS, Hou S, Yang ZQ, et al. Evodiamine relieve LPS-induced mastitis by inhibiting AKT/NF-kappaB p65 and MAPK signaling pathways. Inflammation. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01533-9

55. Tang J, Xu LQ, Zeng YW, Gong F. Effect of gut microbiota on LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-kB signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 91:107272. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107272

56. Kan XC, Hu GQ, Huang BX, Guo WJ, Huang YP, Chen YS, et al. Pedunculoside protects against LPS-induced mastitis in mice by inhibiting inflammation and maintaining the integrity of blood-milk barrier. Aging. (2021) 13:19460–74. doi: 10.18632/aging.203357

57. Liu XH, Wu LM, Wang JL, Dong XH, Zhang SC, Li XH, et al. Long non-coding RNA RP11-490M81 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced pyroptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells via the TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Immunobiology. (2021) 226:152133. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2021.152133

58. Zhao YJ, Chen YE, Zhang HJ, Gu X. LncRNA UCA1 remits LPS-engendered inflammatory damage through deactivation of miR-499b-5p/TLR4 axis. IUBMB Life. (2021)7: 463–73. doi: 10.1002/iub.2443

59. Khan MZ, Khan A, Xiao JX, Ma YL, Ma JY, Gao J, et al. Role of the JAK-STAT pathway in bovine mastitis and milk production. Animals. (2020) 10:2107. doi: 10.3390/ani10112107

60. Guo WJ, Liu JX, Li W, Ma H, Gong Q, Kan XC, et al. Niacin alleviates dairy cow mastitis by regulating the GPR109A/AMPK/NRF2 signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:3321. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093321

61. Li B, Xi PP, Wang ZL, Han XG, Xu YY, Zhang YS, et al. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway participates in Streptococcus uberis-induced inflammation in mammary epithelial cells in concert with the classical TLRs/NF-κB pathway. Vet Microbiol. (2018) 227:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.10.031

62. Wang JJ, Guo CM, Wei ZK, He XX, Kou JH, Zhou ES, et al. Morin suppresses inflammatory cytokine expression by downregulation of nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated primary bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Dairy Sci. (2016) 99:3016–22. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10330

63. Andreotti CS, Pereyra EAL, Baravalle C, Rwnna MS, Ortega HH, Calvinho LF, et al. Staphylococcus aureus chronic intramammary infection modifies protein expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) subfamily components during active involution. Res Vet Sci. (2014) 96:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.11.002

64. Chockalingam A, Paape MJ, Bannerman DD. Increased milk levels of transforming growth factor-alpha, beta1, and beta2 during Escherichia coli-induced mastitis. J Dairy Sci. (2005) 88:1986–93. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72874-5

65. Chen Z, Liang Y, Lu QY, Nazar M, Mao YJ, Aboragah A, et al. Cadmium promotes apoptosis and inflammation via the circ08409/miR-133a/TGFB2 axis in bovine mammary epithelial cells and mouse mammary gland. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2021) 222:112477. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112477

66. Yang W, Li XZ, Qi SP, Li XR, Zhou K, Qing SZ, et al. lncRNA H19 is involved in TGF-beta1-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition in bovine epithelial cells through PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. PeerJ. (2017) 5:e3950. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3950

67. Bekhouche B, Tourville A, Ravichandran Y, Tacine R, Abrami L, Dussiot M, et al. A toxic palmitoylation of Cdc42 enhances NF-κB signaling and drives a severe autoinflammatory syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 146: 1201–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.03.020

68. Gernez Y, Jesus AAD, Alsaleem H, Macaubas C, Roy A, Lovell D, et al. Severe autoinflammation in 4 patients with C-terminal variants in cell division control protein 42 homolog (CDC42) successfully treated with IL-1β inhibition. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2019) 144: 1122–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.017

69. Liu WM, Jiang LB, Bian C, Liang Y, Xing R, Yishakea M, et al. Role of CX3CL1 in diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. (2016) 64:371–83. doi: 10.1007/s00005-016-0395-9

Keywords: dairy cow, lncRNA, bovine mammary epithelial cells, mastitis, RNA-seq

Citation: Wang J-P, Hu Q-C, Yang J, Luoreng Z-M, Wang X-P, Ma Y and Wei D-W (2021) Differential Expression Profiles of lncRNA Following LPS-Induced Inflammation in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. Front. Vet. Sci. 8:758488. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.758488

Received: 14 August 2021; Accepted: 04 October 2021;

Published: 29 October 2021.

Edited by:

Aline Silva Mello Cesar, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Julio Villena, CONICET Centro de Referencia para Lactobacilos (CERELA), ArgentinaQingyou Liu, Guangxi University, China

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Hu, Yang, Luoreng, Wang, Ma and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhuo-Ma Luoreng, bHVvcmVuemh1b21hQG54dS5lZHUuY24=; Xing-Ping Wang, d3hwQG54dS5lZHUuY24=

Jin-Peng Wang

Jin-Peng Wang Qi-Chao Hu

Qi-Chao Hu Jian Yang

Jian Yang Zhuo-Ma Luoreng

Zhuo-Ma Luoreng Xing-Ping Wang

Xing-Ping Wang Yun Ma

Yun Ma Da-Wei Wei

Da-Wei Wei