95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Vet. Sci. , 08 October 2021

Sec. Veterinary Humanities and Social Sciences

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.687967

This article is part of the Research Topic Competencies in Veterinary Education View all 9 articles

Martin Cake1*

Martin Cake1* Melinda Bell1

Melinda Bell1 Kate Cobb2†

Kate Cobb2† Adele Feakes3†

Adele Feakes3† Wendy Hamood3†

Wendy Hamood3† Kirsty Hughes4†

Kirsty Hughes4† Eva King5†

Eva King5† Caroline F. Mansfield6†

Caroline F. Mansfield6† Michelle McArthur3†

Michelle McArthur3† Susan Matthew7†

Susan Matthew7† Liz Mossop8†

Liz Mossop8† Susan Rhind4†

Susan Rhind4† Daniel Schull5†

Daniel Schull5† Sanaa Zaki9†

Sanaa Zaki9†This paper presents a mini-review of employability as a guiding outcome in veterinary education—its conceptualisation, utility, core elements and dimensions, and pedagogical approaches—through a summary of the findings of a major international project with the same aims (the VetSet2Go project). Guided by a conception of the successful veterinary professional as one capable of navigating and sustainably balancing the (sometimes competing) needs and expectations of multiple stakeholders, the project integrated multiple sources of evidence to derive an employability framework representing the dimensions and capabilities most important to veterinary professional success. This framework provides a useful complement to those based in narrower views of competency and professionalism. One notable difference is its added emphasis on broad success outcomes of satisfaction and sustainability as well as task-oriented efficacy, thus inserting “the self” as a major stakeholder and bringing attention to resilience and sustainable well-being. The framework contains 18 key capabilities consistently identified as important to employability in the veterinary context, aligned to five broad, overlapping domains: veterinary capabilities (task-oriented work performance), effective relationships (approaches to others), professional commitment (approaches to work and the broader professional “mission”), psychological resources (approaches to self), plus a central process of reflective self-awareness and identity formation. A summary of evidence supporting these is presented, as well as recommendations for situating, developing, and accessing these as learning outcomes within veterinary curricula. Though developed within the specific context of veterinarian transition-to-practise, this framework would be readily adaptable to other professions, particularly in other health disciplines.

In this paper, we provide a mini-review of the construct of employability—briefly, the ability to gain and sustain meaningful employment across the career lifespan (1, 2)—and its application in the veterinary context, particularly as a guiding outcome in veterinary education. This represents an executive summary of the findings of the VetSet2Go project, a multinational collaborative research project described in greater depth and detail elsewhere in project reports (3, 4) and related research studies (5–12). The project aim was to explore what employability means in the veterinary context, to define the capabilities most important in this context, and to create assessment tools and resources to build these capabilities (3), appropriate for use within veterinary curricula.

A critical element of outcomes-based curricula is that they are designed with the end in mind, guided by specified learning outcomes (13). While in the health professions the core of this process lies in clearly articulating competencies—observable abilities of a professional integrating knowledge, skills, and attitudes (14, 15)—this itself requires clarity around why and for whom these competencies are required, i.e., the overarching outcomes, rationale, and key stakeholders guiding curriculum design. Where elaborated for published veterinary competency frameworks, these drivers have tended to focus primarily on graduate preparedness to ensure patient safety and meeting societal expectations. For example, the stated intention of the Competency-Based Veterinary Education (CBVE) framework is to “prepare graduates for professional careers by confirming their ability to meet the needs of animals and the expectations of society” [(16), p. 1], while also incorporating stakeholder expectations of workplace performance, including preparing graduates for the “complex roles of today's healthcare professionals” [(17), p. 580]. Similarly, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons' Day One Competences document (18) describes “the knowledge, skills and attributes required of veterinary students upon graduation to ensure that they are prepared for their first role in the profession and safe to practise independently” [(18) p. 3]. These frameworks are thus primarily focused on quality assurance to protect patients and clients, and only secondarily on other benefits of preparedness such as employer or graduate satisfaction.

Several competency frameworks have outlined a broader set of outcomes and rationales. Bok et al. (19) used a Delphi procedure to develop an integrative framework that intentionally reduced the prominence of technical expertise, listing this as only one domain alongside communication, collaboration, entrepreneurship, scholarship, public health and welfare responsibilities, and personal development. The drivers cited for this broader curriculum framework were: societal changes placing increasing importance on “generic” or professional competencies, closing the transitional gap due to inadequate or mismatched preparation for work, and to “future-proof” learning beyond graduation (19). Similarly, the 2011 NAVMEC report (20) outlined a framework weighted towards professional (non-technical) competencies, in response to evolving societal needs and challenges including technology, financial sustainability, and lifestyle balance. The report framed veterinary education as increasing value, not only in the general sense of developing skills valuable to society and to employers, but also which for graduates personally “increases their value in the veterinary medical market” [(20) p. 31]. These broader frameworks thus address the needs of multiple stakeholders including the graduate themselves, such as smooth transition to work, broad career opportunities, well-being, and sustained financial and professional success.

Arguably, this broader set of outcomes aligns more fully with the construct of employability than with competency, particularly when the latter is more narrowly defined around observable abilities (14). Bell et al. (6) outlined the case for embracing employability as an overarching goal of veterinary education, as a complement to the essential aims of competency and professionalism. As an educational “lens,” employability brings particular focus on transition to work, career success and satisfaction, long-term sustainability, well-being and resilience, and human potential. This focus aligns with multiple contemporary challenges for veterinary education and for the profession, including: evolving views of both the nature of employment and the “work-readiness” role of higher education, driving the so-called “employability agenda” (21); concerns about the future sustainability of the veterinary workforce and the profession, as highlighted in various industry reports in the US and UK (20, 22–25); and the need to support well-being in the face of elevated mental health risks (26–29).

While multiple definitions of employability exist, none have emerged as dominant (30). Most definitions reference the capacity to gain and sustain employment (2, 31–33), through possession of a set of assets seen as desirable to potential employers (2, 34, 35). Broader and more holistic definitions are focused less on employment outcomes and employer-led “key skills” and more towards contextual person- and process-centred perspectives (36, 37). The VetSet2Go project adapted the widely-cited definitions of Knight and Yorke (38) and Dacre Pool and Sewell (34) to derive a working definition of employability in the veterinary context as: a set of adaptive personal and professional capabilities that enable a veterinarian to gain and sustain employment, contribute meaningfully to the profession and develop a professional pathway that achieves satisfaction and success (6). It is particularly this framing around personal outcomes of satisfaction (34) and meaningfulness (31, 39, 40) in work, and the longer-term trajectory of adaptive, sustainable development that distinguishes employability from “day-one” competency and professionalism. Recognising the reciprocity of these employer- and employee-led perspectives, as well as the complexity of the multiple roles and stakeholder needs a veterinary professional must fulfil (41), an alternative definition developed from the project was: “an individual's capacity to sustainably satisfy the optimal balance of all stakeholder demands and expectations in a work context, including their own” (12).

Recent reviews unpacking the conceptual complexity of employability have been published by Williams et al. (30) and Small (21). Widely used conceptual models of employability include Knight and Yorke's (35) USEM model and Dacre Pool and Sewell's CareerEDGE model (34). Some authors subdivide employability assets into various forms of capital, describing properties of an individual that elicit employment demand or provide added functionality to an employer (30, 42, 43). These include human capital (knowledge, skills and training), social capital (connexions and networks), cultural capital (experiences enhancing cultural fit), and psychological capital (psychological strengths) (30). Major psychological factors include adaptability or flexibility (32, 44) and willingness or work ethic (33). Some recognise emotional intelligence (34) or interpersonal skills (21, 31) as a distinct element of employability capital spanning across learned skills and psychological traits. These psychological factors, respectively, align loosely to the major personality dimensions of openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness as defined in the Five-Factor Model of personality (45), which have all been positively associated with work performance (46).

These various forms of capital are translated into employability outcomes by a further process dimension of career development, representing the process of navigating oneself into future roles (30). This includes a number of elements including signalling (ability to articulate and present assets) and self-management (self-awareness of goals and values). The core developmental processes in employability include reflective self-awareness, which in turn builds self-beliefs (self-efficacy, self-esteem, self-confidence) (34, 35, 47). Rust and Froud (47) argued for critical self-awareness or personal literacy as a universal meta-attribute or “master key” vital to both employability and academic learning. These central processes are notably similar to those in professional identity formation; from this perspective employability is mainly an identity project (37, 48–50).

A major aim of the VetSet2Go project was to develop an employability framework for veterinary education, defining the capabilities most important to employability in this context. The framework was informed by evidence from multiple stakeholder perspectives including a best-evidence systematic review (51); interviews and focus groups of employers (5, 10), recent graduates (5), and clients (9); large international surveys of clients (9) and other stakeholders (veterinary employers, employees, colleagues, academics, industry bodies) (11); and an aligned subproject exploring veterinary career motivations, resilience, and well-being (7, 8, 52). These various strands of stakeholder evidence were integrated through a consensus process involving the project team and an expert Delphi procedure (3).

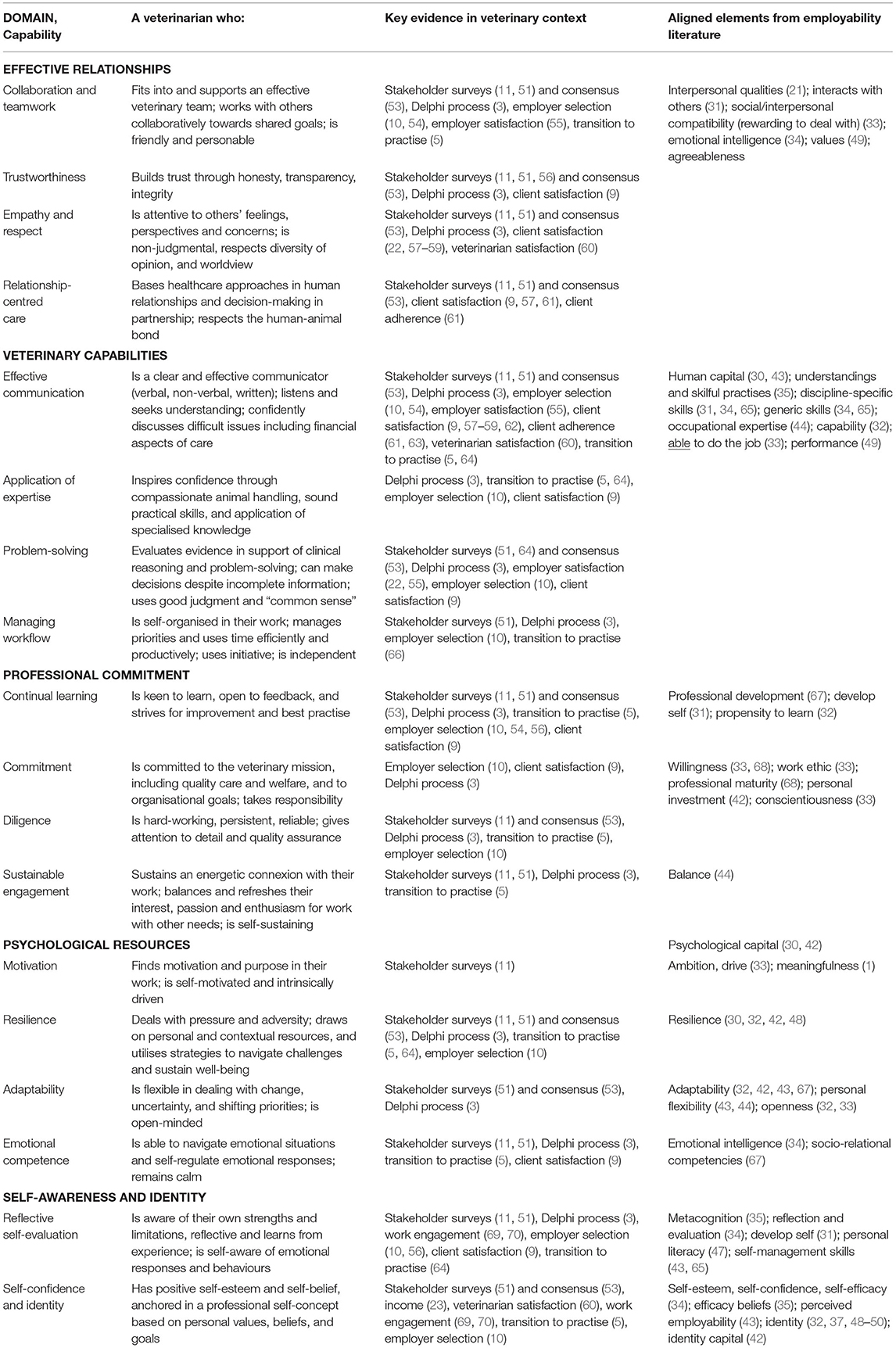

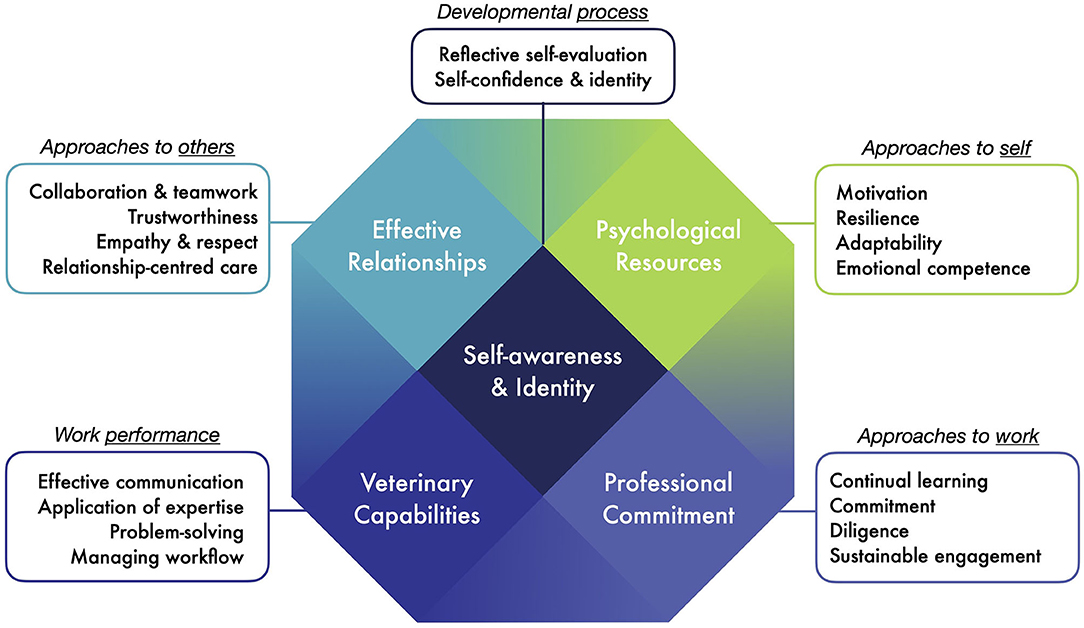

The derived framework contains 18 key capabilities consistently identified as important to employability in the veterinary context (Table 1). The term capability (71) is used to distinguish these from competencies or “skills,” and to signal their enabling, potential, and contextual nature. These are aligned to broad, overlapping domains, or dimensions: veterinary capabilities (task-oriented work performance), effective relationships (approaches to others), professional commitment (approaches to work and the broader professional “mission”), psychological resources (approaches to self). These are activated by a central process of reflective self-awareness and identity formation. These domains overlap somewhat to form an “employability crystal” model (Figure 1). For example, communication is both a “hard” discipline-specific clinical skill and a “soft” relational skill. The alignment of these domains to elements from the broader employability literature such as human and psychological capital (30), willingness (33), metacognition, and efficacy beliefs (34, 35) are indicated in Table 1. The conceptual basis for the five dimensions of the crystal is outlined by Cake et al. (12). These dimensions reflect a balance between recognising employability as established partly from a work (task-oriented) context, and partly from a human (psychological/interpersonal) context; partly from shorter-term efficacy and partly from longer-term sustainability (71); partly from possession of a set of “assets” or capital, and partly from a process of growth and identity formation (37, 49, 50). As in Harden and others' three circle model of medical education outcomes (13), employability is conceived as based partly in work performance, partly in approaches to performance (broadly grouped as approaches to work, to others, and to self), and partly in overarching “meta-competencies” (72) including reflective self-awareness.

Table 1. The 18 capabilities and five domains identified as consistently important to employability in the veterinary context, with exemplar descriptions, key published evidence from the veterinary literature, and aligned elements from the broader employability literature.

Figure 1. The “crystal” model of veterinary employability, with five overlapping domains and 18 aligned capabilities.

A number of important caveats apply to this employability framework. While it includes elements of competency and professionalism, it is intended to complement and not replace more comprehensive frameworks for these essential outcomes (16, 18, 19). It is primarily oriented to graduate-level clinical veterinary practise, so omits some competencies known to be important in mid- to late-career including business skills (5, 73) or in other veterinary work contexts (e.g., research skills). It also omits some process elements known to be important for employability more broadly though not prominent in the veterinary context, including career management (“navigating the world of work”) (31, 65), signal management (e.g., job applications, interviews) (42, 43), and social capital (e.g., networking) (30, 43).

Embracing employability as a core guiding outcome offers both opportunities and challenges for veterinary education. Structural barriers in veterinary curricula may potentially limit student and faculty engagement with employability. The strongly vocational and heavily accredited nature of healthcare degree programs, combined with high graduate employment rates, may encourage the false assumption that employability development occurs automatically. Over-full and content-heavy curricula may leave employability easily crowded out by more traditional disciplinary outcomes (74). Faculty may resist giving up curriculum space to content they view as “soft,” or may lack the capacity to confidently teach it (48). Another potential pitfall is mismatch with the hidden curriculum, if staff role models do not “walk the talk.”

Overcoming these barriers requires a clearly articulated and locally relevant definition, rationale, and conceptual framework for employability, as well as professional development for faculty to enable collective ownership and a shared approach (36). As in the VetSet2Go project, it is recommended to adopt a broad, holistic definition of employability (i.e., beyond just employer-led “key skills”), and a guiding rationale that stretches beyond initial employment and “work-readiness” to include success, satisfaction, meaning, sustainability, and balance. Since employability pedagogy requires “slow” learning approaches best integrated across multiple reflection cycles, whole-of-course, embedded, and vertically integrated strategies are more likely to succeed than stand-alone or “bolt-on” approaches (36). Employability should be revisited at multiple points across the program, to gain the benefits of both early awareness, and experiential learning in authentic clinical contexts, which may alter student confidence (75). Employability learning may be delivered in a variety of modes including workshops and group discussions, team-based tasks, reflective writing and portfolios, role plays and simulations, mentoring programs, “story-telling” in guest seminars, clinical rotations, work-integrated learning placements, and extracurricular programs.

The need to articulate guiding learning outcomes for employability without reducing their complexity is recognised as a major challenge for employability pedagogy (48). Similarly, the need to tolerate the complex, overlapping, and “fuzzy” outcomes typical of employability may challenge competency-based systems. Only the minority of employability capabilities are “competencies” in the narrow sense of observable abilities; the majority are psychological or attitudinal factors (e.g., self-beliefs, habits, attitudes, values, metacognition) thus may defy precise rubrics or measurement.

Despite this complexity and ambiguity, it remains important to make employability learning outcomes explicit in curricula, ideally within program-level learning outcomes. While employability outcomes overlap considerably with those based in competency and professionalism, these overlapping constructs are better treated as distinct “lenses” to explore all the dimensions of a successful veterinary professional rather than wedging employability into existing competency or professionalism frameworks (6). While accountability- or altruistic service-based framings of professionalism may seem counter to some aspects of employability, employability is compatible with professionalism framed as professional identity formation in the sense of “becoming” a professional (76); these share a similar core process and pedagogy (41, 77).

Employability pedagogy should be centred on self-awareness, reflective self-evaluation, and identity formation. These processes form a “master key” to simultaneous development of employability, competency, and professionalism. While awareness of limitations is emphasised in the latter frameworks, in employability self-awareness equally builds awareness of strengths to be harnessed or “activated,” as well as vulnerabilities to target for further development. Self-awareness also builds the ability to articulate or present assets to potential employers (e.g., in a curriculum vitae, portfolio, or interview).

The idea of “finding fit” is highlighted in the employability literature (30, 48), aligning with Viner's (78) premise that long-term success in the veterinary profession requires congruence between professional objectives and personal values. In contrast to normative frameworks such as competency, viewing employability as finding fit highlights the uniqueness of students' capability sets, personality traits, and core values and beliefs. This personalised and contextual view of employability removes normative thresholds (38), such that no-one need be judged “unemployable” but rather yet to find best fit with a professional niche and culture that mutually values them and that they also value (71).

Assessment of employability is recognised as challenging, partly because of the predominance of summative, criterion-driven approaches to assessment (38). Some of the more ability- or behaviour-based aspects of employability may be suited to summative assessment, such as direct observation or longitudinal evaluations in authentic workplace contexts, though these may be limited by low reliability (79). Other aspects of employability based more in attitudes, values, or metacognition may be better targeted formatively through guided reflection, experiential learning, mentoring, and rich feedback. Suitable assessment methods include reflective journals, portfolios, self-assessment rubrics, direct observation in a workplace, and supervisor and peer feedback (38, 79). For these more personal aspects, there may be no threshold expectation of capability, but rather only the expectation that each student has developed an appropriate level of self-awareness.

The VetSet2Go project concluded that the most feasible and fruitful approach to assessment for employability in veterinary education is likely to be multiple cycles of guided self-reflection complemented by rich, multisource feedback. A free online self-assessment tool for veterinary employability and associated resources were developed for the project1. An example of the implementation of this tool and its face validity was provided by Stalin (75). Since the ability to self-assess has inherent limitations, rich multisource feedback plays an important role in calibrating and triangulating self-evaluation, given that others' perceptions necessarily form a key part of employability as a process of social validation. Use of multiple “low-stakes” assessments from different perspectives (i.e., multisource feedback) has been shown in other contexts such as professionalism to overcome the error and bias in subjective assessments (80). The extensive requirement for clinical experience in veterinary degree programs, extended by mandatory extramural placements (i.e., work-integrated learning, WIL) in some countries, creates valuable opportunities for authentic employability learning if paired with an efficient method for gathering rich feedback from supervisors and observers. In this sense employability offers a solid shared framework for engagement of external partners and mentors in veterinary education. Ideally, employability outcomes should be addressed in programmatic outcome evaluation and graduate feedback.

This mini-review highlights the role and utility of employability as a broad and holistic guiding outcome in veterinary education, as a complement to the narrower paradigms of competency and professionalism. Major differences between employability and the latter outcomes include employability's broader focus inclusive of diverse career paths (via “transferable” skills) and multiple definitions of success. Another difference is its balance across the needs of multiple stakeholders, most notably the learner/graduate themselves, thus inserting “the self” as a major stakeholder and bringing attention to resilience and sustainable well-being. The additional focus on personal outcomes of success, satisfaction, meaningfulness, and sustainability in future employment (31, 34, 35, 71) balances existing frameworks that focus primarily on quality assurance and task-oriented efficacy (“work-readiness”) at the point of graduation. Another distinction is employability's greater emphasis on awareness of strengths as well as limitations, and on exploring and finding “fit.”

The breadth and complexity (multidimensionality) of employability offers both benefits and challenges in veterinary education. Employability's focus on implicit attitudes and “approaches” more so than readily measured abilities may require extra attention to formative, subjective assessment methods such as self-reflection and multisource feedback. Another challenge lies in defining explicit outcomes for employability development without reducing these to a list of “key skills.” The five domain conceptual model developed for the VetSet2Go project provides one possible solution, in particular its central focus on the process element of reflective self-awareness and identity formation. This may be more compatible with professionalism development based more in professional identity formation than in virtue- or behaviour-based models (76, 81).

The recommendations of the VetSet2Go project (3, 6) were to frame employability in veterinary education as focused on success and satisfaction in meaningful employment, more than just “getting a job,” and on sustainability as well as efficacy. Employability depends more on attitudes and “approaches” more than key skills, and on a central self-awareness and growth process as well as possessed “assets” (50). It requires personalising of professional learning and “finding fit,” and balancing the perspectives of multiple stakeholders including employers, clients, colleagues, and particularly (centrally) the employee/graduate themselves. Focusing on these aspects through employability, as a complement to the existing frameworks of competency and professionalism, offers multiple potential benefits in veterinary education including smoother transition-to-practise; sustainable career satisfaction; well-being, resilience, and life balance; broadening and diversification of career opportunities; and overall graduate success.

MC and MB drafted the manuscript. All authors, as members of the VetSet2Go project team, contributed important intellectual content within the research, perspectives, critical analysis and conceptual framework presented, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The VetSet2Go project was supported by the Australian Government, Office for Learning and Teaching, Grant Number ID15-4930.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Laura King, Project Manager of the VetSet2Go project and all those who contributed to the project [detailed in reference (3)] for their important contributions to the project's success.

1. Bennett D. Embedding Employ ABILITY Thinking Across Higher Education. Final Report 2018. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education and Training (2018).

2. Hillage J, Pollard E. Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis. London: Department of Education and Employment (1998).

3. Cake MA, Bell M, Cobb K, Feakes A, Hamood W, Hughes K, et al. Interpreting Employability in the Veterinary Context: A Guide and Framework for Veterinary Educators. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, Department of Education and Training (2018). Available online at: https://ltr.edu.au/resources/ID15-4930_Cake_VetSet2GoWhitePaper_2018.pdf (accessed June 01, 2020).

4. Cake MA, King L, Bell M, Cobb K, Feakes A, Hamood W, et al. VetSet2Go: A Collaborative Outcomes and Assessment Framework Building Employability, Resilience and Veterinary Graduate Success. Final Report 2018. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, Department of Education and Training (2019). Available online at: https://ltr.edu.au/resources/ID15-4930_Cake_FinalReport_2019.pdf (accessed November 04, 2019).

5. Bell M, Cake M, Mansfield C. Success in career transitions in veterinary practice: perspectives of employers and their employees. Vet Rec. (2019) 185:232. doi: 10.1136/vr.105133

6. Bell M, Cake M, Mansfield CF. Beyond competence: why we should talk about employability in veterinary education. J Vet Med Educ. (2018) 45:27–37. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0616-103r1

7. Cake MA, Mansfield CF, McArthur ML, Zaki S, Matthew SM. An exploration of the career motivations stated by early career veterinarians in Australia. J Vet Med Educ. (2018) 46:545–54. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0717-093r

8. Cake MA, McArthur MM, Matthew SM, Mansfield CF. Finding the balance: uncovering resilience in the veterinary literature. J Vet Med Educ. (2017) 44:95–105. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0116-025R

9. Hughes K, Rhind S, Mossop L, Cobb K, Morley E, Kerrin M, et al. ‘Care about my animal, know your stuff and take me seriously': United Kingdom and Australian clients' views on the capabilities most important in their veterinarians. Vet Rec. (2018) 183:534. doi: 10.1136/vr.104987

10. Schull D, King E, Hamood W, Feakes A. ‘Context' matters: factors considered by employers when selecting new graduate veterinarians. High Educ Res Dev. (2021) 40:386–99. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1740181

11. Bell MA, Cake M, Mansfield CF. International multi-stakeholder consensus for the capabilities most important to employability in the veterinary profession. Vet Rec. (2021) 188:e20. doi: 10.1002/vetr.20

12. Cake M, Bell M, Mossop L, Mansfield CF. Employability as sustainable balance of stakeholder expectations – towards a model for the health professions. High Educ Res Dev. (2021). doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1891025. [Epub ahead of print].

13. Harden RM, Crosby JR, Davis MH AMEE. Guide No. 14: outcome-based education: part 1 - an introduction to outcome-based education. Med Teach. (1999) 21:7–14. doi: 10.1080/01421599979969

14. Frank JR, Snell LS, Ten Cate O, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. (2010) 32:638–45. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

15. Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. (2013) 88:1088–94. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b

16. AAVMC Working Group on Competency-Based Veterinary Education, Molgaard LK, Hodgson JL, Bok HGJ, Chaney KP, Ilkiw JE, et al. Competency-Based Veterinary Education: Part 1 - CBVE Framework. Washington, DC: Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC) (2018).

17. Matthew SM, Bok HGJ, Chaney KP, Read EK, Hodgson JL, Rush BR, et al. Collaborative development of a shared framework for competency-based veterinary education. J Vet Med Educ. (2019) 47:580–93. doi: 10.3138/jvme.2019-0082

18. The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. Day One Competences. London: Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (2020). Available online at: https://www.rcvs.org.uk/document-library/day-one-competences/ (accessed June 12, 2020).

19. Bok HGJ, Jaarsma AD, Teunissen PW, van der Vleuten CPM, van Beukelen P. Development and validation of a competency framework for veterinarians. J Vet Med Educ. (2011) 38:262–9. doi: 10.3138/jvme.38.3.262

20. North American Veterinary Medical Education Consortium (NAVMEC). Roadmap for Veterinary Medical Education in the 21st Century—Responsive, Collaborative, Flexible. Washington, DC: North American Veterinary Medical Education Consortium (2011).

21. Small L, Shacklock K, Marchant T. Employability: a contemporary review for higher education stakeholders. J Vocat Educ Train. (2017) 70:148–66. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2017.1394355

22. Brown JP, Silverman JD. The current and future market for veterinarians and veterinary medical services in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1999) 215:161–83.

23. Cron WL, Slocum JV Jr., Goodnight DB, Volk JO. Executive summary of the Brakke management and behavior study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2000) 217:332–8. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.332

24. Veterinary Futures Project Board. Taking charge of our future: A vision for the veterinary profession for 2030. London: Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS), British Veterinary Association (BVA) (2015). Available online at: http://vetfutures.org.uk/download/reports/Vet%20Futures%20report.pdf (accessed November 26, 2015).

25. Willis NG, Monroe FA, Potworowski JA, Halbert G, Evans BR, Smith JE, et al. Envisioning the future of veterinary medical education: the Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges Foresight Project, final report. J Vet Med Educ. (2007) 34:1–41. doi: 10.3138/jvme.34.1.1

26. Mellanby RJ, Herrtage ME. Survey of mistakes made by recent veterinary graduates. Vet Rec. (2004) 155:761–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.155.24.761

27. Bartram DJ, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DSA. cross-sectional study of mental health and well-being and their associations in the UK veterinary profession. Soc Psychiatric Epidemiol. (2009) 44:1075–85. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0030-8

28. Gardner DH, Hini D. Work-related stress in the veterinary profession in New Zealand. New Zeal Vet J. (2006) 54:119–24. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2006.36623

29. Hatch PH, Winefield HR, Christie BA, Lievaart JJ. Workplace stress, mental health, and burnout of veterinarians in Australia. Aust Vet J. (2011) 89:460–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00833.x

30. Williams S, Dodd LJ, Steele C, Randall RA. systematic review of current understandings of employability. J Educ Work. (2016) 29:877–901. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2015.1102210

31. Bennett D, Richardson S, MacKinnon P. Enacting Strategies for Graduate Employability: How Universities Can Best Support Students to Develop Generic Skills. Final Report 2016 (Part A). Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training (2016).

32. Fugate M, Kinicki AJ, Ashforth BE. Employability: a psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J Vocat Behav. (2004) 65:14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

33. Hogan R, Chamorro-Premuzic T, Kaiser RB. Employability and career success: bridging the gap between theory and reality. Indust Organ Psychol. (2013) 6:3–16. doi: 10.1111/iops.12001

34. Dacre Pool L, Sewell P. The key to employability: developing a practical model of graduate employability. Educ Train. (2007) 49:277–89. doi: 10.1108/00400910710754435

35. Knight P, Yorke M. Employability through the curriculum. Tert Educ Manag. (2002) 8:261–76. doi: 10.1080/13583883.2002.9967084

36. Cole D, Tibby M. Defining and Developing Your Approach to Employability. A Framework for Higher Education Institutions. York: The Higher Education Academy. (2013).

37. Jackson D. Re-conceptualising graduate employability: the importance of pre-professional identity. High Educ Res Dev. (2016) 35:925–39. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1139551

38. Knight P, Yorke M. Assessment, Learning and Employability. Maidenhead, UK: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. (2003).

39. Oliver B. Redefining graduate employability and work-integrated learning: proposals for effective higher education in disrupted economies. J Teach Learn Grad Employab. (2015) 6:56–65. doi: 10.21153/jtlge2015vol6no1art573

40. Bennett D, Richardson S, Mahat M, Coates H, MacKinnon P, Schmidt L. Navigating uncertainty and complexity: higher education and the dilemma of employability. In: Thomas T, Levin E, Dawson P, Fraser K, Hadgraft R, editors. Research and Development in Higher Education: Learning for Life and Work in a Complex World. 6–9 July, 2015. Melbourne, SA; Milperra, NSW: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia, Inc. (2015).

41. Armitage-Chan E, Maddison J, May SA. What is the veterinary professional identity? Preliminary findings from web-based continuing professional development in veterinary professionalism. Vet Rec. (2016) 178:318. doi: 10.1136/vr.103471

42. Tomlinson M. Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Educ Train. (2017) 59:338–52. doi: 10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090

43. Clarke M. Rethinking graduate employability: the role of capital, individual attributes and context. Stud High Educ. (2018) 43:1923–37. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

44. Van der Heijde CM, Van der Heijden BA. competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Hum Resource Manage. (2006) 45:449–76. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20119

45. McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the Five-Factor Model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1987) 52:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

46. Rothmann S, Coetzer EP. The big five personality dimensions and job performance. South Afr J Indust Psychol. (2003) 29:68–74. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v29i1.88

47. Rust C, Froud L. ‘Personal literacy': the vital, yet often overlooked, graduate attribute. J Teach Learn Grad Employab. (2011) 2:28–40. doi: 10.21153/jtlge2011vol2no1art551

48. Artess J, Hooley T, Mellors-Bourne R. Employability: A Review of the Literature 2012 to 2016. York: Higher Education Academy. (2017).

49. Hinchliffe GW, Jolly A. Graduate identity and employability. Brit Educ Res J. (2011) 37:563–84. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.482200

50. Holmes L. Competing perspectives on graduate employability: possession, position or process? Stud High Educ. (2013) 38:538–54. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.587140

51. Cake MA, Bell MA, Williams JC, Brown FJ, Dozier M, Rhind SM, et al. Which professional (nontechnical) competencies are most important to the success of graduate veterinarians? A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. Med Teach. (2016) 38:550–63. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173662

52. Matthew SM, Carbonneau KJ, Mansfield CF, Zaki S, Cake MA, McArthur ML. Development and validation of a contextualised measure of resilience in veterinary practice: the Veterinary Resilience Scale-Personal Resources (VRS-PR). Vet Rec. (2020) 186:489. doi: 10.1136/vr.105575

53. Lewis RE, Klausner JS. Nontechnical competencies underlying career success as a veterinarian. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2003) 222:1690–6. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1690

54. Heath TJ, Mills JN. Criteria used by employers to select new graduate employees. Aust Vet J. (2000) 78:312–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb11777.x

55. Danielson JA, Wu TF, Fales-Williams AJ, Kirk RA, Preast VA. Predictors of employer satisfaction: technical and non-technical skills. J Vet Med Educ. (2012) 39:62–70. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0711.072R

56. Schull D, Morton JM, Coleman GT, Mills PC. Final-year student and employer views of essential personal, interpersonal and professional attributes for new veterinary science graduates. Aust Vet J. (2012) 90:100–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00874.x

57. Woodcock A, Barleggs D. Development and psychometric validation of the veterinary service satisfaction questionnaire (VSSQ). J Vet Med Ser A. (2005) 52:26–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2004.00676.x

58. McArthur ML, Fitzgerald JR. Companion animal veterinarians' use of clinical communication skills. Aust Vet J. (2013) 91:374–80. doi: 10.1111/avj.12083

59. Case DB. Survey of expectations among clients of three small animal clinics. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1988) 192:498–502.

60. Shaw JR, Adams CL, Bonnett BN, Larson S, Roter DL. Veterinarian satisfaction with companion animal visits. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2012) 240:832–41. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.7.832

61. Kanji N, Coe JB, Adams CL, Shaw JR. Effect of veterinarian-client-patient interactions on client adherence to dentistry and surgery recommendations in companion-animal practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2012) 240:427–36. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.4.427

62. Greenberg H, Stupine B, Dunn K, Schurr R, Wilson J, Biery DN. Findings from a client satisfaction survey for a university small animal hospital. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1992) 28:182–4.

63. Lue TW, Pantenburg DP, Crawford PM. Impact of the owner-pet and client-veterinarian bond on the care that pets receive. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2008) 232:531–40. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.4.531

64. Rhind SM, Baillie S, Kinnison T, Shaw DJ, Bell CE, Mellanby RJ, et al. The transition into veterinary practice: opinions of recent graduates and final year students. BMC Med Educ. (2011) 11:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-64

65. Bridgstock R. The graduate attributes we've overlooked: enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. High Educ Res Dev. (2009) 28:31–44. doi: 10.1080/07294360802444347

66. Riggs EA, Routly JE, Taylor IR, Dobson H. Support needs of veterinary surgeons in the first few years of practice: a survey of recent and experienced graduates. Vet Rec. (2001) 149:743–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.149.24.743

67. Lo Presti A, Ingusci E, Magrin ME, Manuti A, Scrima F. Employability as a compass for career success: development and initial validation of a new multidimensional measure. Int J Train Dev. (2019) 23:253–75. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12161

68. Chhinzer N, Russo AM. An exploration of employer perceptions of graduate employability. Educ Train. (2018) 60:104–20. doi: 10.1108/ET-06-2016-0111

69. Mastenbroek NJJM, Jaarsma ADC, Demerouti E, Muijtjens AMM, Scherpbier AJJA, van Beukelen P. Burnout and engagement, and its predictors in young veterinary professionals: the influence of gender. Vet Rec. (2014) 174:144. doi: 10.1136/vr.101762

70. Mastenbroek NJJM, Jaarsma ADC, Scherpbier AJJA, van Beukelen P, Demerouti E. The role of personal resources in explaining well-being and performance: a study among young veterinary professionals. Eur J Work Organ Psy. (2014) 23:190–202. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.728040

71. van der Klink JJL, Bultmann U, Burdorf A, Schaufeli WB, Zijlstra FRH, Abma FI, et al. Sustainable employability - definition, conceptualization, and implications: a perspective based on the capability approach. Scand J Work Env Hea. (2016) 42:71–9. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3531

72. Harden RM, Crosby JR, Davis MH, Friedman M AMEE. Guide No. 14: Outcome-based education: part 5 - from competency to meta-competency: a model for the specification of learning outcomes. Med Teach. (1999) 21:546–52. doi: 10.1080/01421599978951

73. Cake MA, Rhind S, Baillie S. The need for business skills in veterinary education: perceptions versus evidence. In: Henry C, editor. Veterinary Business and Enterprise Theoretical Foundations and Practical Cases. London: Saunders Elsevier (2014). p. 9–22.

74. Williamson K. ‘Skills for employability? No need thanks, we're radiographers!' Helping graduate healthcare professionals to stand out from the crowd. Pract Evid Schol Teach Learn High Educ. (2015) 9:33–53.

75. Stalin CE. Exploring the use of a novel self-assessment employability questionnaire to evaluate undergraduate veterinary attainment of professional attributes: an explanatory mixed-methods study. J Vet Med Educ. (2021) 48:267–75. doi: 10.3138/jvme.2019-0027

76. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. (2014) 89:1446–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

77. Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. (2015) 90:701–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731

78. Viner B. Success in Veterinary Practice: Maximising Clinical Outcomes and Personal Well-Being. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell (2010). p. 202.

79. Baillie S, Warman SM, Rhind SM. A Guide to Assessment in Veterinary Medical Education. 2nd ed. Bristol: University of Bristol (2014). Available online at: http://www.bris.ac.uk/vetscience/media/docs/guide-to-assessment.pdf (accessed September 17, 2014).

80. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad Med. (2014) 89:511–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000147

Keywords: employability, veterinarian, veterinary education, competency, professional identity

Citation: Cake M, Bell M, Cobb K, Feakes A, Hamood W, Hughes K, King E, Mansfield CF, McArthur M, Matthew S, Mossop L, Rhind S, Schull D and Zaki S (2021) Employability as a Guiding Outcome in Veterinary Education: Findings of the VetSet2Go Project. Front. Vet. Sci. 8:687967. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.687967

Received: 30 March 2021; Accepted: 10 September 2021;

Published: 08 October 2021.

Edited by:

Sandra C. Buttigieg, University of Malta, MaltaReviewed by:

Kent Hecker, University of Calgary, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Cake, Bell, Cobb, Feakes, Hamood, Hughes, King, Mansfield, McArthur, Matthew, Mossop, Rhind, Schull and Zaki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Cake, bS5jYWtlQG11cmRvY2guZWR1LmF1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.