- 1Department of Joint Surgery, Honghui Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China

- 2Department of Orthopaedic Trauma, Honghui Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China

Purpose: Older patient population with acetabular fractures is increasing rapidly, requiring enhanced recovery. Acute total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a good option for these patients, and it is becoming increasing popular. However, acute THA has different indications in different studies. Therefore, a systematic review is needed to assess and comprehend the indications for acute THA in older patients.

Methods: A systematic literature review was conducted to identify a retrospective series or prospective studies in older patients (>60 years) with acetabular fractures. The search timeline was from database construction till December 2021; PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases were searched. Two trained professional reviewers independently read the full text of documents that met the inclusion criteria and extracted information on the specific methods used and indication information based on the research design.

Results: In total, there were 601 patients with acetabular fractures aged >60 years from 33 studies were obtained. Twenty-eight studies reported that THA was a feasible treatment option for acetabular fractures in geriatric patients with good outcome. The primary indications were dome impaction, irreducible articular comminution, femoral head injury, and pre-existing osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis. The most common patterns were anterior column and posterior hemitransverse, posterior wall, both columns, and T-type.

Conclusion: Acute THA is an effective treatment strategy for older patients with acetabular fractures and should be considered when the abovementioned indications are observed on preoperative images. (PROSPERO: CRD42022329555).

Introduction

Due to the ongoing demographic change, the incidence of acetabular fractures in patients aged >60 years has markedly increased (1, 2). Herath et al. reported that >50% of patients with acetabular fractures were aged ≥60 years, with the oldest reported patient being 80 years old from the German multicenter pelvic registry system (2). Indeed, geriatric patients constitute the most rapidly growing subgroup of acetabular fractures.

For geriatric patients with acetabular fractures, treatment objectives are rapid mobilization of patients on walkers or crutches (3) and rapid recovery to pre-injury level of function (4, 5). Open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) used to be the mainstay of surgical treatment. However, ORIF in older patients is technically and strategically challenging, with high failure rates after ORIF. A retrospective study reported a 30% failure rate (6). Another study on even older patients reported a failure rate of 45% in ORIF cases (7). With the development of surgical equipment, instruments, and technology, treatment for acetabular fracture has considerably changed. Therefore, some authors believe that acute total hip arthroplasty (THA) may be more beneficial than ORIF and should be strongly considered in older patients with acetabular fractures (8, 9).

Acute THA for displaced acetabular fractures was first reported by Westerborn in 1954 (10). Theoretically, by allowing immediate weight bearing and faster rehabilitation, THA could reduce the risks of early and late local complications associated with the ORIF for this injury type (11). However, indications for acute THA are different across studies. Anglen et al. reported dome impaction as an indication of failure for the internal fixation of acetabular fractures in geriatric patients (12). Kreder et al. reported that marginal impaction and residual displacement of >2 mm were associated with the development of arthritis, which was related to poor function and THA requirement (13). Solomon et al. reported that a displaced fracture involving the anterior or both columns, irreducible articular comminution, protrusion of >1 cm, and osteoporosis were indications for immediate THA (14). In addition, the fracture pattern is another factor that needs consideration in THA treatment. Aprato et al. (15) reported that fractures of the posterior column and/or wall with severe cartilage damage can be treated safely with acute THA. In Borg et al. (16), more patients had anterior column and posterior hemitransverse and both column patterns. In Sarantis et al. (17), the surgeons preferred THA for patients with anterior column to other pattern.

For these reasons, a systematic evaluation system needs to be established to evaluate and comprehend the indications for acute THA in older patients with acetabular fractures. In this systematic review, we aimed to summarize the individual indications and fracture patterns from case series of acute THA for acetabular fractures in older patients.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

The ethical approval of the systematic review was waived by the institutional review board of Honghui Hospital, Xi'an Jiaotong University. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Research type, retrospective or prospective series studies; 2) Research participants, older patients (≥60 years) with unilateral or bilateral acetabular fractures who underwent acute THA; 3) Index of interest, factors and indications for acute THA in these patients. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age <60 years, staged THA, or THA after failure of ORIF. This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022329555).

Acute THA defined as early or primary THA, and surgeon used acute THA as the ultimate treatment for older patients with acetabular fracture in three weeks. In addition, the patients should not receive the any other operation before ultimate THA.

Search strategy

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews, we searched for the following terms in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library: (“Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip” OR “hip replacement” OR “hip arthroplasty”) AND (“acetabular fracture” OR “acetabulum fracture” OR “acetabul*”) AND (“old” OR “elderly” OR “elder” OR “geriatric”) The search timeline was from database construction to December 2021. There were no other restrictions on the search process.

Information and data extraction

Two trained professional reviewers independently read the full text of documents that met the inclusion criteria and extracted the following information: study design, number of patients, age, sex, prosthesis, indications for THA, follow-up, and outcomes. The primary outcome was indications for THA, and the secondary item was the fracture type of patients receiving THA. The disagreements during this process were resolved by a third reviewer.

Results

Literature search process and results

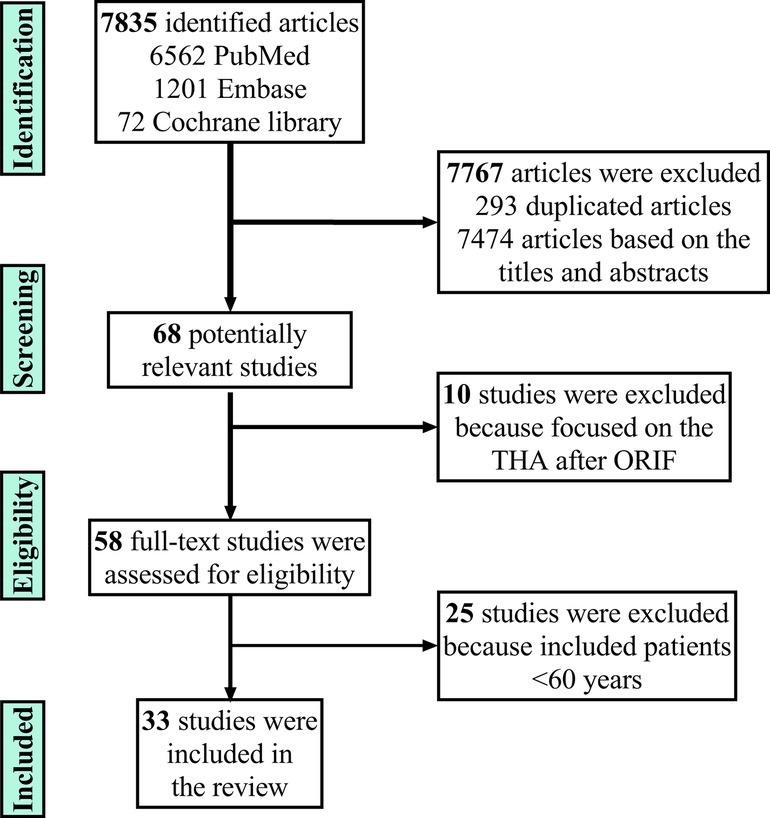

Overall, 6562, 1201, and 72 papers (total: 7835) were obtained from Pubmed, Embase, and Cochrane Library, respectively. After excluding 293 duplicated papers, the reviewer read the title and abstract of each study and excluded 7,474 unrelated papers, leaving 68 studies. Most studies mentioned the revision operation after ORIF, and some studies included patients <60 years. After excluding these studies and studies without indicators of interest or fracture type, 33 studies were finally included (4, 6, 7, 11, 14–42). Figure 1 shows the flow chart of including studies.

General information of the included study

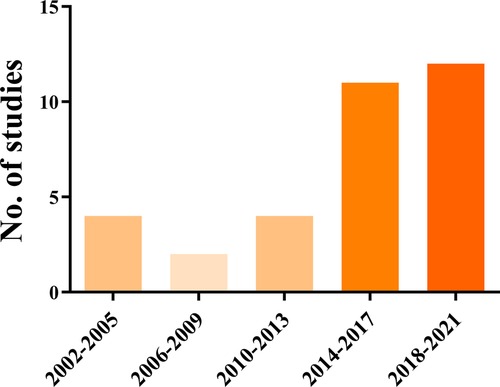

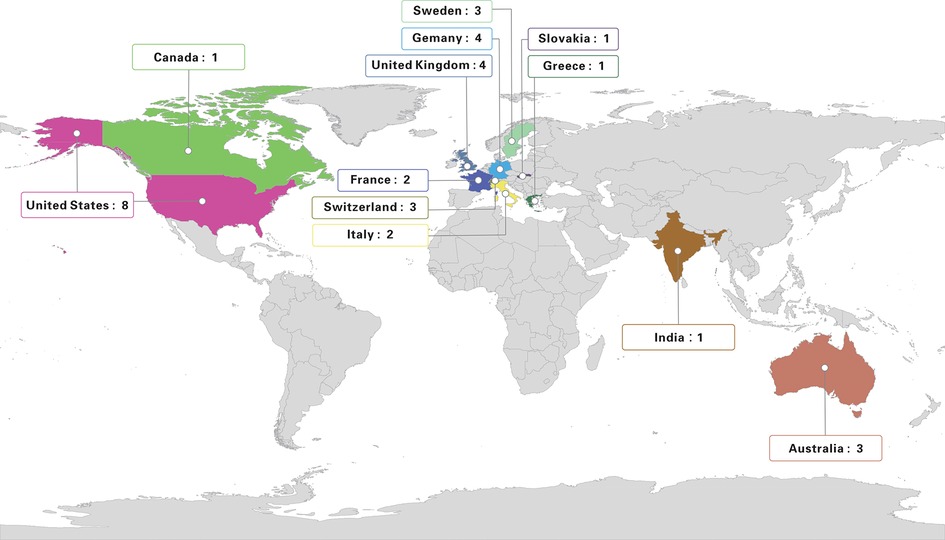

Of the 33 studies, 29 were published in English. These studies were published during 2002–2021. Figure 2 shows the change in number of studies with time. We found that in recent years, studies have focused on THA for older patients with acetabular fractures, especially from 2014 to 2021. In addition, eight studies were from the United States, four in Germany, four in the United Kingdom, three in Sweden, three in Switzerland, three in Australia, two in Italy, two in France, one in India, one in Canada, one in Greece, and one in Slovakia. We marked the included studies on the world map and noticed that majority of the research on THA for older patients were conducted in Europe and America (Figure 3).

Main results

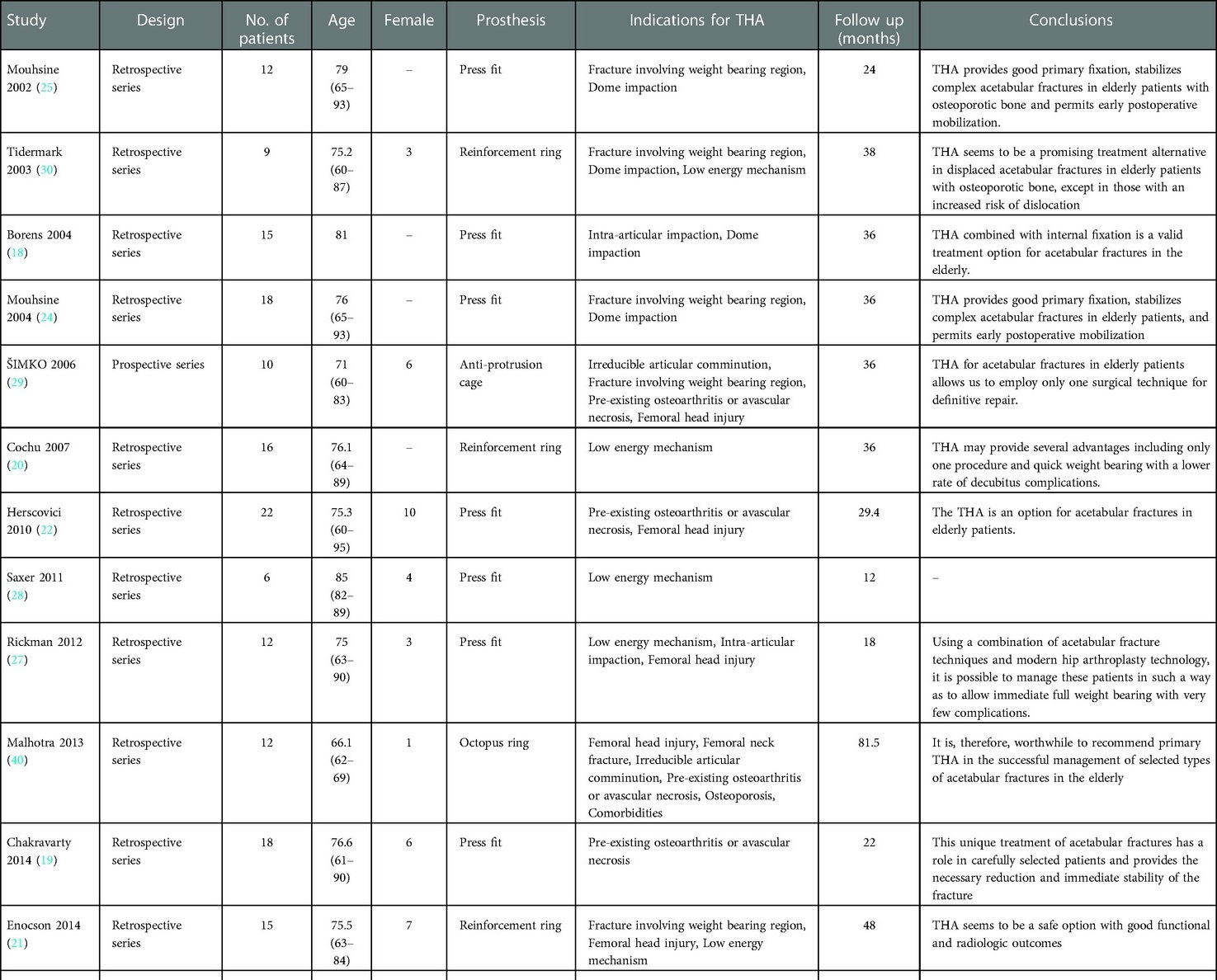

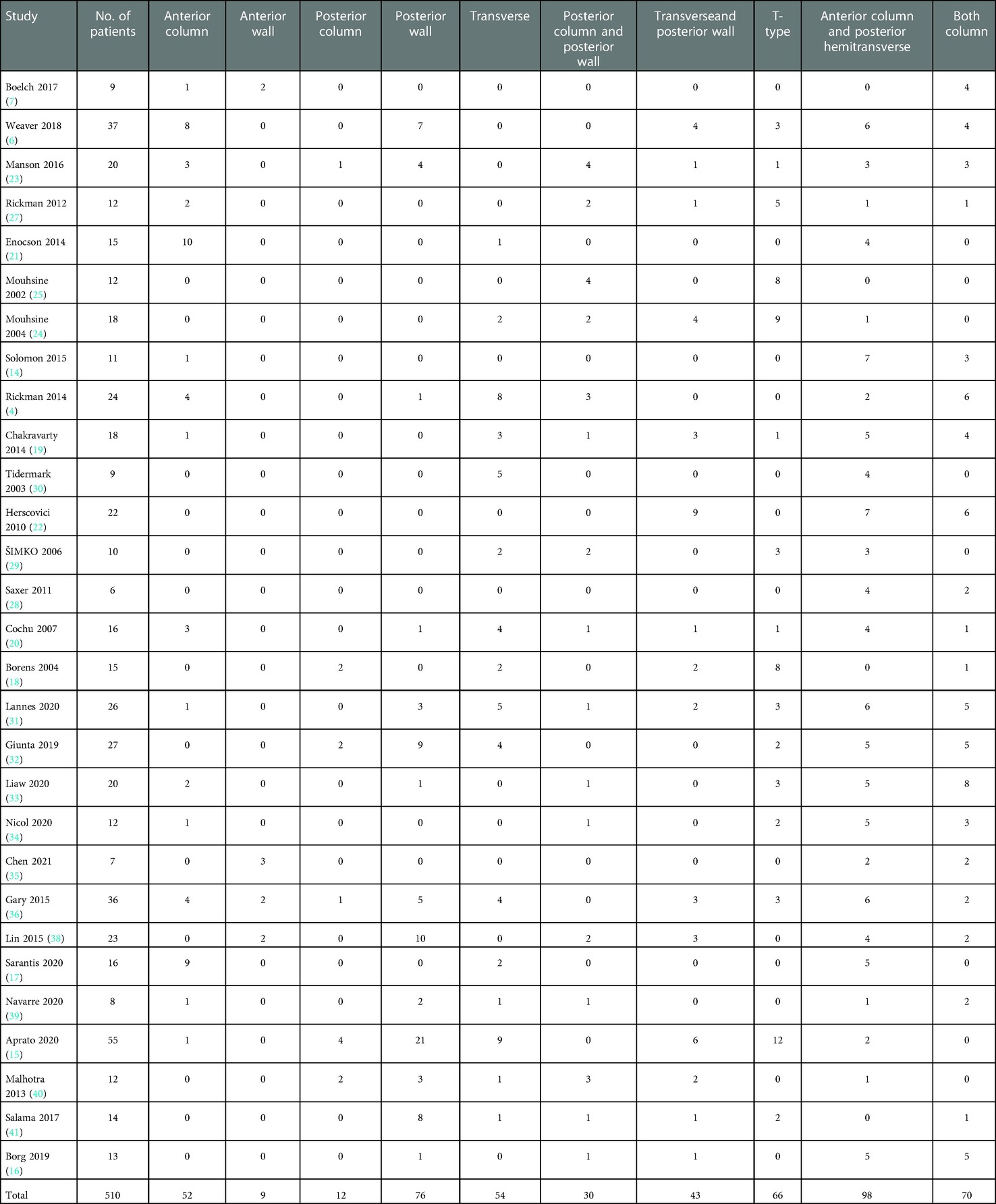

Of the 33 studies, 30 were retrospective and three were prospective. In total, we obtained 601 patients aged ≥60 years with acetabular fractures. In each study, the sample size was 6–55. Women accounted for 47.45% of all patients. The prosthesis type of THA fixation used were different across studies. Thirty-two studies reported follow-up, with the period ranging from 4.5 (7) to 81.5 months (40), of which 28 studies reported that THA or ORIF plus THA was a feasible treatment option for acetabular fractures in older patients. The remaining four did not identify the role of THA in older patients with acetabular fractures. Specific baseline information for the included studies is shown in Table 1.

All the studies described their indications for THA in the patients, and the most reported indications were dome impaction (16★), irreducible articular comminution (13★), femoral head injury (12★), and pre-existing osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis (10★). All factors are summarized in Table 2.

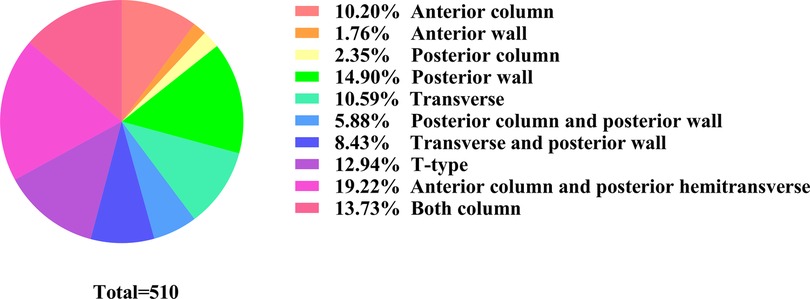

As for fracture type, we have summarized the fracture types in Table 3. Detailed fracture type was reported for 510 patients. With respect to Letournel's classification system, 203 patients showed elementary patterns and 307 showed complex patterns. The most common patterns were anterior column and posterior hemitransverse (19.22%), posterior wall (14.90%), both columns (13.73%), and T-type (12.94%) (Figure 4).

Discussion

In this review, we determined the most commonly reported indications for acetabular fractures, as well as the fracture patterns in older patients.

The incidence of acetabular fractures in older patients has rapidly increased worldwide. Most older patients have poor bone quality, multiple comorbidities, and increased perioperative risk, which may reduce the chance of favorable outcome (3, 43). Thus, surgeons should particularly note the characteristics of acetabular fractures in older patients and encourage early weight bearing. Although ORIF for acetabular fractures has gained wide acceptance in the treatment of young patients, the indications and results of this treatment in the older adult population remain unclear. On the one hand, the failure and conversion to THA rate in older patients is high after ORIF, which was reported as 19% by Archdeacon et al. (44), 25% by Gary et al. (45), 28% by O’Toole et al. (46), and 30.6% by Gary et al. (47); these are significantly higher than the 8.5% reported in the literature on the treatment of acetabular fractures in all age groups (48). On the other hand, the time point of THA was not long after ORIF, which was reported as within 2 years after ORIF in Weaver et al. (6), 19.6 months in Boelch et al. (7), a mean of 18 months in Archdeacon et al. (44), and a mean of 1.4 years after ORIF in Gary et al. (45). Of note, the survival of the native hip joint after ORIF was <2 years in most studies. Two or more operations within a short period for older patients with comorbidities is a serious concern. Therefore, appropriate patient selection is very important for ORIF, and THA should be considered as an initial alternative. Further, it is crucial to carefully select older patients with poor bone quality and multiple comorbidities as candidates for THA.

In this systematic review, all the studies described their indications for THA in the patients, and we give the image sign one star when the image sign was mentioned one time. By this way, the relative importance of image sign was identified. At last, we identified dome impaction, irreducible articular comminution, femoral head injury, and pre-existing osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis as the primary indications for THA in older patients with acetabular fractures. Dome impaction, the so-called “seagull sign,” is usually observed in osteoporotic and older patients. Anglen et al. reported that dome impaction was 100% predictive of ORIF failure in their series (12). However, in a study by Laflamme et al., after adequate reduction in the superomedial dome, the failure rate was 33% (49). Several studies reported osteoporosis as a commonly identified factor among the patients, but bone density was not regularly examined before treatment. Osteoporosis was speculated to cause low-energy fracture; osteoporotic patients with superomedial dome impaction did not benefit from attempted ORIF (12). Irreducible articular comminution was reported by 13 studies and is a subjective factor and varies in different-level surgeons. It was often followed by acetabular comminuted fracture or loss of bone and cartilage. In fact, we believe dome impaction and irreducible articular comminution are critical because they lead to difficult adequate reduction, especially in older patients with osteoporosis. For an identified fracture, dome impaction or articular comminution could be improved with surgical skill (50, 51), and good reduction of the articular surface can be achieved. However, the use of ORIF does not encourage early weight bearing. Femoral head injury and pre-existing hip degeneration were two important objective factors. Femoral head injury was reported in 10 articles, but the detailed injury model was not described and may involve fracture, cartilage contusion, or missing bone fragment. Pre-existing osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis was another important indication for THA. Thus, when any of these four indications are observed in preoperative images or during operation, THA or conversion to THA should be considered in operation.

As for the fracture type, the most patterns were the anterior column and posterior hemitransverse, posterior wall, both columns, and T-type, which contributed to >60% of all fractures. One elementary and three associated patterns were noted. Fractures of the posterior wall were the most common type of acetabular fractures (52), with a wide variety of fracture types (with respect to comminution, size and location of fragments, displacements, presence of marginal impaction, and labral avulsions) (53). Three types of associated patterns were often hard to reduce or fracture comminution. Failure to adequately deal with these types results in suboptimal reduction, inadequate fixation with recurrence of joint instability, and poor long-term results.

According to Rickman et al. (4), patients should be deemed sufficiently fit medically to undergo surgery. Although acute THA is a technically demanding intervention, without significant risks to the patient (11), other studies have not focused on all the factors reported in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of these important factors. Indications for THA were based on a number of factors, and we included patient and fracture factors. Moreover, surgeon skill is another important factor. Different surgeons have different skill levels and experience in treatment of the fracture. Particularly, a difference in operation may be observed between senior and junior surgeons or between trauma and joint specialist surgeons.

This review has two limitations. Firstly, this is a systematic narrative review, not including typical meta-analysis because the included studies were series cases, and there is no controlled ORIF group. Therefore, there is no statistical analysis in forest plot, heterogeneity analysis, risk of bias and funnel chart. Secondly, all factors were obtained based on the frequency in studies; this method of assessment may not be accurate in identifying the most important indications. Surgeons must evaluate older patients with acetabular fractures before selecting the operation strategy. These factors may aid surgeons in selecting the optimal treatment option.

In conclusion, acute THA is an effective treatment strategy for older patients with acetabular fractures. We recommend THA when one of the signs of dome impaction, irreducible articular comminution, femoral head injury, and pre-existing osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis are present, especially in fracture patterns of the anterior column and posterior hemitransverse, posterior wall, both columns, and T-type.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: PX and YZ. Collocted and analyzed the data: B-FZ, LL, KX, HW, BW and H-QW. Wrote the manuscript: B-FZ. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 82072432), the Foundation of Xi'an Municipal Health Commission (Grant Number: 2021ms09), Shaanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology, Innovative Talents Promotion Plan – Youth Science and Technology Star Project (2021KJXX-57).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ferguson TA, Patel R, Bhandari M, Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum in patients aged 60 years and older: an epidemiological and radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. (2010) 92:250–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22488

2. Herath SC, Pott H, Rollmann MFR, Braun BJ, Holstein JH, Hoch A, et al. Geriatric acetabular surgery: letournel's Contraindications then and now-data from the German pelvic registry. J Orthop Trauma. (2019) 33(Suppl 2):S8–S13. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001406

3. Guerado E, Cano JR, Cruz E. Fractures of the acetabulum in elderly patients: an update. Injury. (2012) 43(Suppl 2):S33–41. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(13)70177-3

4. Rickman M, Young J, Trompeter A, Pearce R, Hamilton M. Managing acetabular fractures in the elderly with fixation and primary arthroplasty: aiming for early weightbearing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2014) 472:3375–82. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3467-3

5. Walls A, McAdam A, McMahon SE, Diamond OJ. The management of osteoporotic acetabular fractures: current methods and future developments. Surgeon. (2021) 19:e289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2021.01.002

6. Weaver MJ, Smith RM, Lhowe DW, Vrahas MS. Does total hip arthroplasty reduce the risk of secondary surgery following the treatment of displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly compared to open reduction internal fixation? A pilot study. J Orthop Trauma. (2018) 32(Suppl 1):S40–5. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001088

7. Boelch SP, Jordan MC, Meffert RH, Jansen H. Comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total hip replacement for osteoporotic acetabular fractures: a retrospective clinical study. Int Orthop. (2017) 41:1831–7. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3260-x

8. Jauregui JJ, Weir TB, Chen JF, Johnson AJ, Sardesai NR, Maheshwari AV, et al. Acute total hip arthroplasty for older patients with acetabular fractures: a meta-analysis. J Clin Orthop Trauma. (2020) 11:976–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.01.003

9. Mccormick BP, Serino J, Orman S, Webb AR, Wang DX, Mohamadi A, et al. Treatment modalities and outcomes following acetabular fractures in the elderly: a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. (2022) 32(4):649–59. doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-03002-3

10. Westerborn A. Central dislocation of the femoral head treated with mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. (1954) 36:307–14. doi: 10.2106/00004623-195436020-00009

11. Tissingh EK, Johnson A, Queally JM, Carrothers AD. Fix and replace: an emerging paradigm for treating acetabular fractures in older patients. World J Orthop. (2017) 8:218–20. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.218

12. Anglen JO, Burd TA, Hendricks KJ, Harrison P. The “gull sign": a harbinger of failure for internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. (2003) 17:625–34. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200310000-00005

13. Kreder HJ, Rozen N, Borkhoff CM, Laflamme YG, Mckee MD, Schemitsch EH, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after simple and complex acetabular fractures involving the posterior wall. J Bone Joint Surg Br. (2006) 88:776–82. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17342

14. Solomon LB, Studer P, Abrahams JM, Callary SA, Moran CR, Stamenkov RB, et al. Does cup-cage reconstruction with oversized cups provide initial stability in THA for osteoporotic acetabular fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2015) 473:3811–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4460-1

15. Aprato A, Giachino M, Messina D, Masse A. Fixation plus acute arthroplasty for acetabular fracture in eldery patients. J Orthop. (2020) 21:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.09.012

16. Borg T, Hernefalk B, Hailer NP. Acute total hip arthroplasty combined with internal fixation for displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly: a short-term comparison with internal fixation alone after a minimum of two years. Bone Joint J. (2019) 101-B:478–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2018-1027.R2

17. Sarantis M, Stasi S, Milaras C, Tzefronis D, Lepetsos P, Macheras G. Acute total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of acetabular fractures: a retrospective study with a six-year follow-up. Cureus. (2020) 12:e10139. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10139

18. Borens O, Wettstein M, Garofalo R, Blanc CH, Kombot C, Leyvraz PF, et al. [Treatment of acetabular fractures in the elderly with primary total hip arthroplasty and modified cerclage. Early results]. Unfallchirurg. (2004) 107:1050–6. doi: 10.1007/s00113-004-0827-6

19. Chakravarty R, Toossi N, Katsman A, Cerynik DL, Harding SP, Johanson NA. Percutaneous column fixation and total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of acute acetabular fracture in the elderly. J Arthroplasty. (2014) 29:817–21. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.009

20. Cochu G, Mabit C, Gougam T, Fiorenza F, Baertich C, Charissoux JL, et al. [Total hip arthroplasty for treatment of acute acetabular fracture in elderly patients]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. (2007) 93:818–27. doi: 10.1016/S0035-1040(07)78465-9

21. Enocson A, Blomfeldt R. Acetabular fractures in the elderly treated with a primary burch-schneider reinforcement ring, autologous bone graft, and a total hip arthroplasty: a prospective study with a 4-year follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. (2014) 28:330–7. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000016

22. Herscovici D Jr., Lindvall E, Bolhofner B, Scaduto JM. The combined hip procedure: open reduction internal fixation combined with total hip arthroplasty for the management of acetabular fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Trauma. (2010) 24:291–6. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181b1d22a

23. Manson TT, Reider L, O'toole RV, Scharfstein DO, Tornetta P 3rd, Gary JL, et al. Variation in treatment of displaced geriatric acetabular fractures among 15 level-I trauma centers. J Orthop Trauma. (2016) 30:457–62. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000632

24. Mouhsine E, Garofalo R, Borens O, Blanc CH, Wettstein M, Leyvraz PF. Cable fixation and early total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of acetabular fractures in elderly patients. J Arthroplasty. (2004) 19:344–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.08.020

25. Mouhsine E, Garofalo R, Borens O, Fischer JF, Crevoisier X, Pelet S, et al. Acute total hip arthroplasty for acetabular fractures in the elderly: 11 patients followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop Scand. (2002) 73:615–8. doi: 10.1080/000164702321039552

26. Ortega-Briones A, Smith S, Rickman M. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: midterm outcomes of column stabilisation and primary arthroplasty. Biomed Res Int. (2017) 2017:4651518. doi: 10.1155/2017/4651518

27. Rickman M, Young J, Bircher M, Pearce R, Hamilton M. The management of complex acetabular fractures in the elderly with fracture fixation and primary total hip replacement. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2012) 38:511–6. doi: 10.1007/s00068-012-0231-9

28. Saxer F, Studer P, Jakob M. [Open stabilization and primary hip arthroplasty in geriatric patients with acetabular fractures: combination of minimally invasive techniques]. Unfallchirurg. (2011) 114:1122–7. doi: 10.1007/s00113-011-2064-0

29. Simko P, Braunsteiner T, Vajczikova S. [Early primary total hip arthroplasty for acetabular fractures in elderly patients]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. (2006) 73:275–82.17026887

30. Tidermark J, Blomfeldt R, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tornkvist H. Primary total hip arthroplasty with a burch-schneider antiprotrusion cage and autologous bone grafting for acetabular fractures in elderly patients. J Orthop Trauma. (2003) 17:193–7. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200303000-00007

31. Lannes X, Moerenhout K, Duong HP, Borens O, Steinmetz S. Outcomes of combined hip procedure with dual mobility cup versus osteosynthesis for acetabular fractures in elderly patients: a retrospective observational cohort study of fifty one patients. Int Orthop. (2020) 44:2131–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04757-w

32. Giunta JC, Tronc C, Kerschbaumer G, Milaire M, Ruatti S, Tonetti J, et al. Outcomes of acetabular fractures in the elderly: a five year retrospective study of twenty seven patients with primary total hip replacement. Int Orthop. (2019) 43:2383–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4204-4

33. Liaw F, Govilkar S, Banks D, Kankanalu P, Youssef B, Lim J. Primary total hip replacement using burch-schneider cages for acetabular fractures. Hip Int. (2022) 32(3):401–6. doi: 10.1177/1120700020957642

34. Nicol GM, Sanders EB, Kim PR, Beaule PE, Gofton WT, Grammatopoulos G. Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty after acetabular open reduction and internal fixation in the elderly-acute vs delayed total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. (2021) 36:605–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.08.022

35. Chen MJ, Wadhwa H, Bellino MJ. Sequential ilioinguinal or anterior intrapelvic approach with anterior approach to the hip during combined internal fixation and total hip arthroplasty for acetabular fractures. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. (2021) 31:635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00590-020-02810-3

36. Gary JL, Paryavi E, Gibbons SD, Weaver MJ, Morgan JH, Ryan SP, et al. Effect of surgical treatment on mortality after acetabular fracture in the elderly: a multicenter study of 454 patients. J Orthop Trauma. (2015) 29:202–8. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000223

37. Manson TT, Slobogean GP, Nascone JW, Sciadini MF, Lebrun CT, Boulton CL, et al. Open reduction and internal fixation alone versus open reduction and internal fixation plus total hip arthroplasty for displaced acetabular fractures in patients older than 60 years: a prospective clinical trial. Injury. (2022) 53(2):523–8. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.09.048

38. Lin C, Caron J, Schmidt AH, Torchia M, Templeman D. Functional outcomes after total hip arthroplasty for the acute management of acetabular fractures: 1- to 14-year follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. (2015) 29:151–9. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000164

39. Navarre P, Gabbe BJ, Griffin XL, Russ MK, Bucknill AT, Edwards E, et al. Outcomes following operatively managed acetabular fractures in patients aged 60 years and older. Bone Joint J. (2020) 102-B:1735–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B12.BJJ-2020-0728.R1

40. Malhotra R, Singh DP, Jain V, Kumar V, Singh R. Acute total hip arthroplasty in acetabular fractures in the elderly using the Octopus system: mid term to long term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. (2013) 28:1005–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.12.003

41. Salama W, Mousa S, Khalefa A, Sleem A, Kenawey M, Ravera L, et al. Simultaneous open reduction and internal fixation and total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of osteoporotic acetabular fractures. Int Orthop. (2017) 41:181–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3175-6

42. Becker CA, Linhart C, Bruder J, Zeckey C, Greiner A, Cavalcanti Kussmaul A, et al. Cementless hip revision cup for the primary fixation of osteoporotic acetabular fractures in geriatric patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. (2021) 107:102745. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.102745

43. Dechert TA, Duane TM, Frykberg BP, Aboutanos MB, Malhotra AK, Ivatury RR. Elderly patients with pelvic fracture: interventions and outcomes. Am Surg. (2009) 75:291–5. doi: 10.1177/000313480907500405

44. Archdeacon MT, Kazemi N, Collinge C, Budde B, Schnell S. Treatment of protrusio fractures of the acetabulum in patients 70 years and older. J Orthop Trauma. (2013) 27:256–61. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318269126f

45. Gary JL, Lefaivre KA, Gerold F, Hay MT, Reinert CM, Starr AJ. Survivorship of the native hip joint after percutaneous repair of acetabular fractures in the elderly. Injury. (2011) 42:1144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.035

46. O'Toole RV, Hui E, Chandra A, Nascone JW. How often does open reduction and internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures lead to hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. (2014) 28:148–53. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31829c739a

47. Gary JL, VanHal M, Gibbons SD, Reinert CM, Starr AJ. Functional outcomes in elderly patients with acetabular fractures treated with minimally invasive reduction and percutaneous fixation. J Orthop Trauma. (2012) 26:278–83. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31823836d2

48. Giannoudis PV, Grotz MR, Papakostidis C, Dinopoulos H. Operative treatment of displaced fractures of the acetabulum. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. (2005) 87:2–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B1.15605

49. Laflamme GY, Hebert-Davies J. Direct reduction technique for superomedial dome impaction in geriatric acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. (2014) 28:e39–43. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318298ef0a

50. Zhuang Y, Lei JL, Wei X, Lu DG, Zhang K. Surgical treatment of acetabulum top compression fracture with sea gull sign. Orthop Surg. (2015) 7:146–54. doi: 10.1111/os.12175

51. Collinge CA, Lebus GF. Techniques for reduction of the quadrilateral surface and dome impaction when using the anterior intrapelvic (modified stoppa) approach. J Orthop Trauma. (2015) 29(Suppl 2):S20–24. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000271

52. Abo-Elsoud M, Kassem E. Fragment-specific fixation of posterior wall acetabular fractures. Int Orthop. (2021) 45:3193–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-021-05110-5

Keywords: acute total hip arthroplasty, acetabular fracture, geriatric patients, systematic review, indications

Citation: Zhang B, Zhuang Y, Liu L, Xu K, Wang H, Wang B, Wen H and Xu P (2023) Current indications for acute total hip arthroplasty in older patients with acetabular fracture: Evidence in 601 patients from 2002 to 2021. Front. Surg. 9:1063469. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1063469

Received: 7 October 2022; Accepted: 13 December 2022;

Published: 6 January 2023.

Edited by:

Vincenzo Giordano, Serviço de Ortopedia e Traumatologia Prof. Nova Monteiro, Hospital Municipal Miguel Couto, BrazilReviewed by:

Hongyi Shao, Beijing Jishuitan Hospital, ChinaAhmed Khalifa, South Valley University, Egypt

© 2023 Zhang, Zhuang, Liu, Xu, Wang, Wang, Wen and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Xu c291c291MzY5QDE2My5jb20=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Orthopedic Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Surgery

Bin-Fei Zhang

Bin-Fei Zhang Yan Zhuang2

Yan Zhuang2 Peng Xu

Peng Xu