94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

EDITORIAL article

Front. Surg. , 11 October 2022

Sec. Cardiovascular Surgery

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.1030172

This article is part of the Research Topic New Challenges with the Management of Rheumatic Heart Disease View all 8 articles

Editorial on the Research Topic

New challenges with the management of rheumatic heart disease

By Soesanto AM. (2022) Front. Surg. 9: 1030172. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1030172

Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD) is still a significant health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries, with 40.5 million prevalent cases resulting in ≈305,000 deaths annually (1, 2). This editorial has covered the articles from the low-middle income countries related to the problem of RHD through the original research and reviews. Unfortunately, only four of the seven articles submitted to the Research Topic are relevant to RHD, preventing a more in-depth understanding of the subject. The low submission rate could be attributed to the difficulties that low- and middle-income countries face in conducting qualified studies. The majority of large RHD studies are multicenter and led by experts from developed countries with adequate funding. A financial constraint limits the methodology and size of the study in low/middle-income countries, not to mention the budget for publication. A language barrier could also make writing and publishing a scientific manuscript difficult. Collaboration with international organizations and between countries may be a good way to increase the number of RHD studies in endemic countries. Follows are the editorial of the interesting four articles related with RHD.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) infection may cause acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and further lead to a devastating complication, rheumatic heart disease (RHD) (3). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all patients with confirmed RHD receive secondary prophylaxis against repeated attacks of ARF in order to prevent further valvular damage (4). The paper by Sarah Wangilisasi et al. (2020) reported a low proportion of RHD patients on regular secondary prophylaxis. Further, GAS throat colonization is high among this population and is associated with not taking/stopping the prophylaxis regimen. Similar founding also reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis that GAS infection is still a global burden (5). This study also reported that most (96%) of GAS isolates were susceptible to penicillin. Based on their findings, educating patients and physicians to use effective secondary prophylaxis is crucial. Another large trial, the GOAL trial, showed that secondary prophylaxis using penicillin reduced the risk of the progression of latent rheumatic heart disease in children and adolescents (6). Improving delivery of secondary prophylaxis can be achieved by strategies to support culturally and age-appropriate adherence and more patient-centered approaches within culturally competent health systems (7).

Another study from a tertiary cardiac center reported the profile and management of RHD. Oktavia Lilyasari et al. (2020) found that RHD complication is most commonly pulmonary hypertension and atrial fibrillation in young adults and heart failure in children. Reactivation cases were found in 17% of cases. Multiple valve disease was more frequent than single valve disease, which may create a heavier hemodynamic burden on the heart. This study showed that even children and young adults already experienced serious complications of RHD and need cardiac surgery-most commonly valve repair. As the disease progresses, a second or even more re-operation may be needed with more challenging surgical techniques, possibly increasing surgical risk. The patients may have a risk of thromboembolism and need life-long anticoagulation, which further exposes them to the risk of bleeding. A high-risk pregnancy also becomes one of the problems. RHD and its complications will cause long-life morbidity and poor outcome. Since this disease is preventable, again prophylaxis strategy is essential. For severe RHD or patients who have had cardiac surgery, although, in individuals >40 years old, the risk of recurrence is extremely low, some guidelines recommend continuing secondary/tertiary prophylaxis. It may be continued beyond 40 years old or even lifelong, especially for patients who have had cardiac valve surgery (8).

The earlier two articles above implied the importance of finding earlier stages of RHD to prevent any progression which leads to further disease burden and poor outcomes. A perspective by Amiliana M Soesanto et al. (2020) proposed a strategy to screen for latent RHD in Indonesia as an early step to control the disease progression. Applying simplified echo criteria, using handheld echo devices, training extended echo operators, and targeting specific groups of children are important variables for screening strategy. Perhaps this strategy may be applied in other low-middle income countries with similar limitations and problems. Nevertheless, to control RHD, it needs good collaboration among the community, health experts, and the government. A model for strengthening health systems is proposed to address other cardiovascular diseases in limited-resource countries. It may require a combination of the prevention of rheumatic fever and RHD, typically through primary healthcare services in community settings; advanced care, which includes tertiary cardiology and cardiac surgery services; and health policy, including measures that national health systems should take (9).

The progression of valve deterioration in RHD includes inflammation and fibrosis. However, the true pathologic mechanism has not been well understood. In the mini-review, Ade M Ambari et al. (2020) explained some hypotheses about the pathomechanism of valve fibrosis which involves angiotensin II, and the proposed mechanism of how angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor may decrease the progression of valve fibrosis. He stated that TGF-b induction by Angiotensin II could further increase the binding of IL-33 to sST2, resulting in the upregulation of Angiotensin II and may progress to calcification and stiffening of the heart valves. ACEIs directly reduce the binding of IL-33 to sST2 and through the inhibition of TGF-b/MAPK/Smad signaling. Therefore, ACE inhibitors may potentially attenuate cardiac fibrosis in RHD via the IL-33/ST2 axis. Although ACE inhibitor is considered hemodynamically safe and effective in patients with rheumatic MR (10), recent valvular guidelines have not yet recommended the use of ACE inhibitor in the medical management of MS (11, 12). This interesting theory needs to be studied further to prove the protective effect on the progression of valve deterioration in RHD, and the authors have been doing an on-going randomized controlled trial to prove this theory (13). If positive results are consistently found, this may become a breakthrough and change the medical management strategy in rheumatic MS patients.

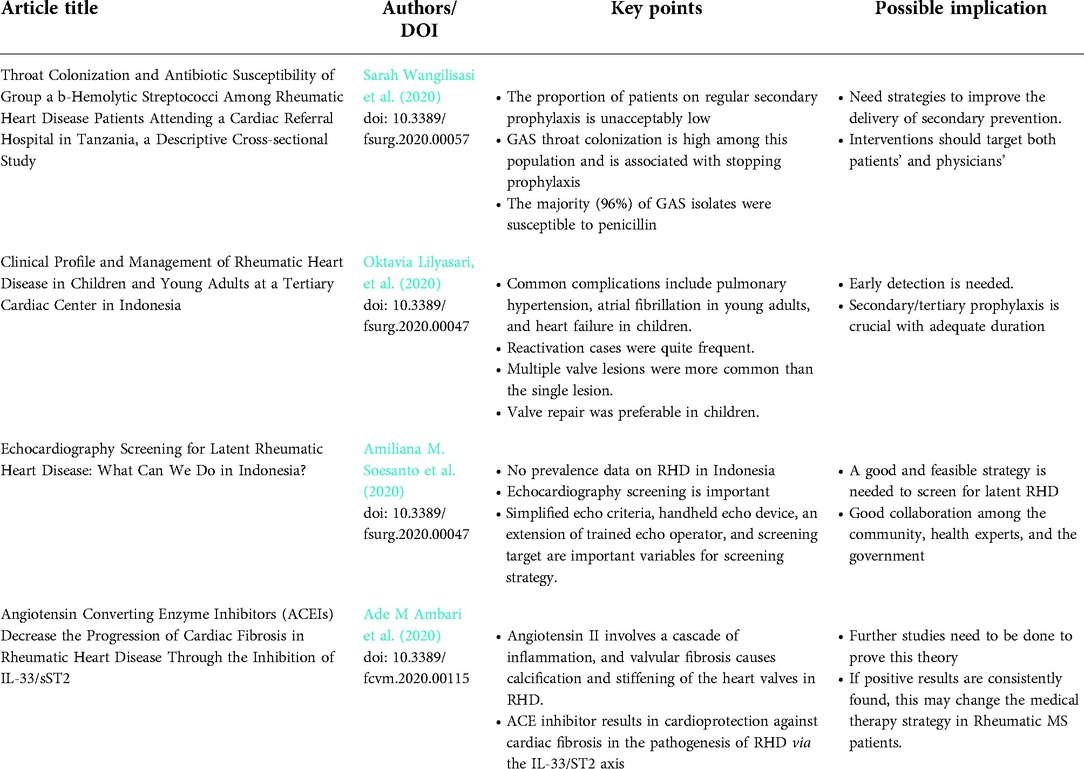

In summary, all four articles shared facts and information about the burden of RHD. It includes the importance of GAS infection, the advanced clinical features of RHD in the young, and the proposed theory causing progressive deterioration of the valves. These articles imply the need for prophylaxis action, starting from a screening program for latent RHD (Table 1). The screening program and prophylaxis action are quite challenging in low-middle income countries. However, a good collaboration among the community, health experts, and the government is important to control RHD better.

Table 1. Summary of the research topic “New Challenges with the Management of Rheumatic Heart Disease.”

AMS is contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Global Burden Disease 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(8)32279-7

2. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, Karthikeyan G, Beaton A, Bukhman G, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990–2015. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

3. Seckeler MD, Hoke TR. The worldwide epidemiology of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 3:67–84. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S12977

4. Bisno A, Butchart EG, Ganguly NK, Ghebrehiwet T, Hung-Chi Lue, Kaplan EL, et al. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Report of a WHO Study Group. Geneva: World Health Organization, Geneva (2004) (Technical Report Series No. 923). ISBN 9241209232; ISSN 0512-3054

5. Miller KM, Carapetis JR, Van Beneden CA, Cadarette D, Daw JV, Moore HC, et al. The global burden of sore throat and group A Streptococcus pharyngitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. (2022) 48:101458. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101458

6. Beaton A, Okello E, Rwebembera J, Grobler A, Engelman D, Alepere J, et al. Secondary antibiotic prophylaxis for latent rheumatic heart disease. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:230–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102074

7. Ralph AP, de Dassel JL, Kirby A, Read C, Mitchell AG, Maguire GP, et al. Improving delivery of secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic heart disease in a high-burden setting: outcome of a stepped-wedge, community, randomized trial. J Am Heart Assoc. (2018) 7:e009308.doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009308

8. Kumar RK, Antunes MJ, Beaton A, Mirabel M, Nkomo VT, Okello E, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of rheumatic heart disease: implications for closing the gap a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2020) 142:e337–57. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000921

9. Watkins DA, Beaton AZ, Carapetis JR, Karthikeyan G, Mayosi BM, Wyber R, et al. Rheumatic heart disease worldwide JACC scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72:1397–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.063

10. Chockalingam A, Venkatesan S, Dorairajan S, Chockalingam V, Subramaniam T, Jaganathan V, et al. Safety and efficacy of enalapril in multivalvular heart disease with significant mitral stenosis—SCOPE-MS. Angiology. (2005) 56:151–8. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600205

11. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

12. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Gentile F, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2021) 143:e72–e227. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Keywords: group a streptococcus, rheumatic heart disease, screening, ACE inhibitor, secondary prophylaxis

Citation: Soesanto AM (2022) Editorial: New challenges with the management of rheumatic heart disease. Front. Surg. 9:1030172. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1030172

Received: 28 August 2022; Accepted: 5 September 2022;

Published: 11 October 2022.

Edited by:

Hendrik Tevaearai Stahel, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland*Correspondence: Amiliana Mardiani Soesanto YW1pbGlhbmExNEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Heart Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Surgery

© 2022 Soesanto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.