- Thoracic Surgery Unit - Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale, Naples, Italy

Background: Invasiveness is considered one of the cornerstones of every field of surgery, and video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) approaches are now routinely used worldwide to perform pulmonary resections. Recently, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) has become the preferred technique in many centers; it is routinely performed using three or four ports with at least one service incision, contrasting with the real concept of invasiveness, especially when compared to uniportal VATS (U-VATS). Hereby, we present our early experience with uniportal RATS (U-RATS) pulmonary resections for early-stage lung cancer. Technical details of surgical steps are accurately described and commented on.

Results: Twenty-four consecutive patients with lung cancer underwent U-RATS anatomical pulmonary resections at our institute. All procedures were completed with the uniportal approach. The mean operative time was 210 min (range 120–350); in the last 10 cases, the operative time was significantly reduced (180 min) compared to the first 10 cases (232 min) (p < 0.02), showing a very fast learning curve. The postoperative pain score was comparable to that for U-VATS and was constantly low.

Conclusions: U-RATS is a safe and feasible technique, combining the advantages of U-VATS with the well-known advantages of robotic surgery.

Introduction

Invasiveness is considered one of the cornerstones of every field of surgery due to less morbidity and faster postoperative recovery compare to open surgery. Video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) approaches are now routinely used worldwide to perform pulmonary resections and are not only limited to standard procedures or early-stage lung cancer but also in the case of advanced stages requiring complex reconstructions (1–4). In particular, since 2004, uniportal VATS (U-VATS) has progressively gained relevance in the thoracic surgery units, including our center, due to its invasiveness compared to multiportal approaches, without differences in feasibility and oncological outcomes (5, 6). Recently, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) is increasingly becoming the preferred technique in many centers worldwide. The main advantages are the 3D vision in the operative field, the intuitive management, and the easy maneuverability, allowing safer and more accurate surgical acts due to the wristed arms and the use of bipolar energy and grasping in both hands (7, 8). However, RATS is routinely performed using three or four ports with at least one service incision (9) in contrast to the real concept of less invasiveness. The possibility of blending the uniportal approach with robotic technology would be an enormous improvement in terms of feasibility, safety, oncological outcomes, and enhanced postoperative recovery. An update of the literature during the revision process of our paper showed a very recent description of the technique (10, 11) and a previous case report (12). Thus, considering our personal experience with U-VATS and standard robotic techniques, we recently started our U-RATS program. Herein, we present our early series of U-RATS pulmonary resections for early-stage lung cancer, focusing on feasibility, safety, surgical technique, and early postoperative outcomes.

Patients and methods

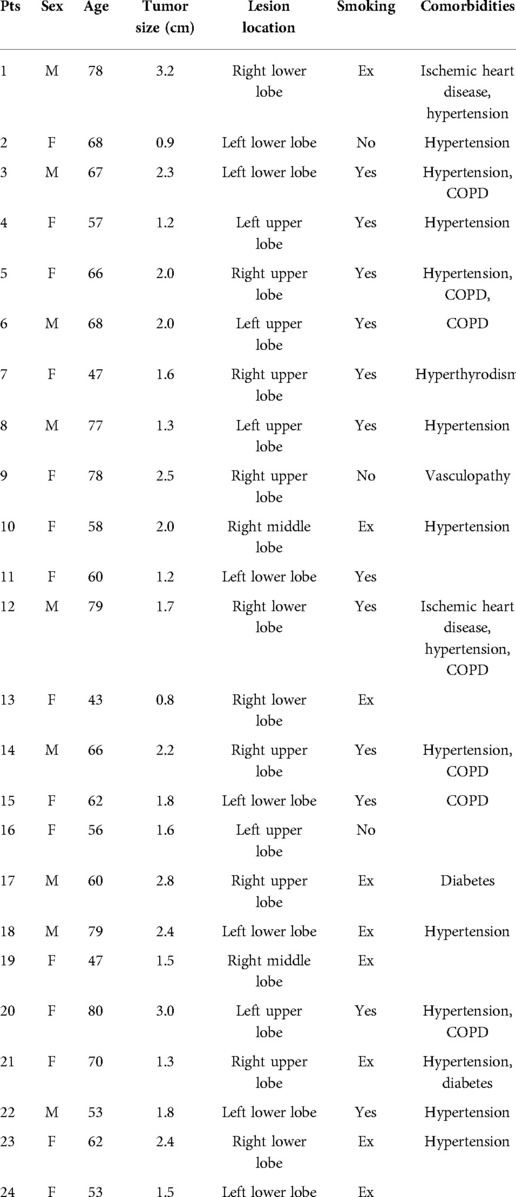

Based on our experience with U-VATS and four-port robotic surgery, in January 2022 at the IRCCS “G. Pascale Foundation” National Cancer Institute of Naples, we started the U-RATS program. Twenty-four consecutive patients (9 males and 15 females, mean age 64 ± 11 years) with lung cancer underwent anatomical pulmonary resections. All patients signed a standard informed consent form as this approach does not have an experimental purpose. Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. Standard preoperative workup was performed including routine blood examinations, pulmonary function tests, arterial blood gas analysis, cardiological assessment, total body computed tomography (CT), and total body positron emission tomography (PET). In most patients, whenever possible, a preoperative diagnosis of lung cancer was achieved by CT fine needle biopsy or fiberoptic bronchoscopy; in other cases, the diagnosis was intraoperatively confirmed after wedge resection. Our standard pain control for minimally invasive surgery includes intraoperative nerve blocking of 3–4 intercostal spaces with 100 mg of local anesthesia (Ropivacain) performed at the beginning of surgery, followed by intravenous postoperative Ketorolac 90 mg/24 h for 2 days, plus 1 g of paracetamol if needed in selected cases. No opioids are routinely used. All surgical procedures have been performed at the console by the same surgeon. In this report, we focus on surgical technical steps, feasibility, and early postoperative outcomes, including pain evaluation using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NRS), complications, and functional recovery, evaluated during the outpatient visit through specific questions about life activities.

Surgical technique

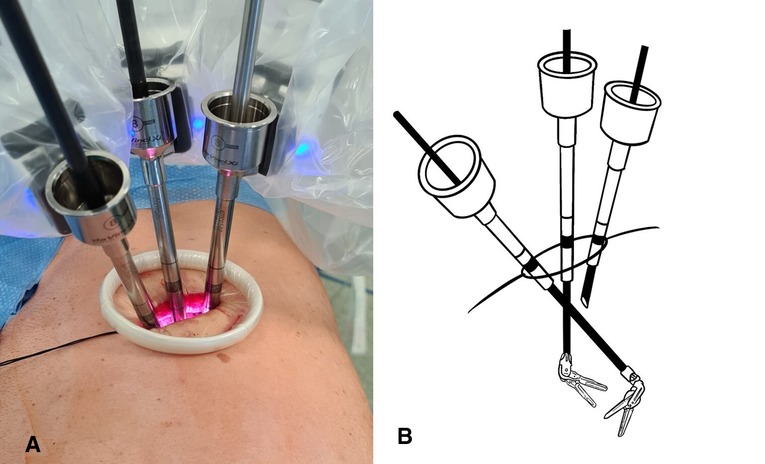

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia with single-lung ventilation using the da Vinci Xi robotic surgical system. The patient is placed in lateral decubitus like a posterolateral incision and flexed to expose the intercostal space better. A 4-cm skin incision is made at the V or VI intercostal space in the middle axillary line. The correct location of the incision is of paramount importance, and it can vary based on the target of surgery and the chest shape. The incision must be as close as possible to the vascular structures that must be resected. This allows the robotic arms to be perpendicular to the target, limiting their conflict and optimizing the available space (Figure 1A). A soft wall protector is used to avoid excessive trauma to the chest wall.

Figure 1. (A) U-RATS: incision in the middle axillary line with trocars perpendicular to the target. (B) U-VATS: incision by the anterior approach with trocars tangential to the target.

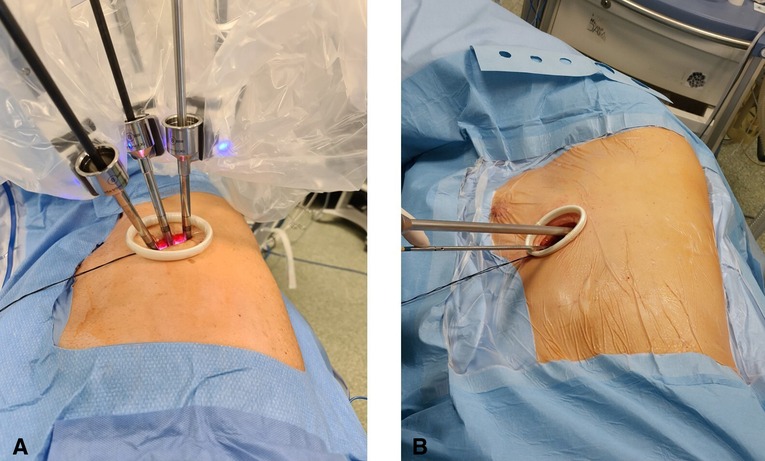

Three robotic arms are always used, and the trocars are directly anchored to the arms without any pressure valve. A 30-degree 10-mm camera is placed on the posterior edge of the incision as in U-VATS surgery, and the other two arms are placed in the remaining space anteriorly. The operative robotic arms work by crossing each other inside the chest; thus, the right robotic arm will be the left surgeon's hand and the left robotic arm will be the right surgeon's hand, as shown in Figure 2. With this setting, to avoid the mirroring effect, it is necessary to apply a reverse mode to the console touchpad, allowing the right hand to control the left robotic arm and vice versa. Gauze peanuts are freely inserted in the chest to be used to mobilize the lung, reducing parenchymal trauma and optimizing movements. A robotic Maryland bipolar forceps dissector is controlled by the right surgeon's hand, and a monopolar fenestrated forceps is controlled by the left surgeon's hand. As usual, the assistant surgeon stands anterior to the patient handling the suction catheter in the space between the three trocars. A suction catheter is not used only to suck fluids but mainly for retraction and exposure of structures. Vascular structures and pulmonary parenchyma are sutured with Sureform 45 Robotic Staplers or with Hem-o-lok robotic clips. Lobectomy or segmentectomy is performed respecting the standard anterior approach (13) to the hilar structures and the fissureless technique (14), whenever possible. At the end of the surgery, a single chest drain toward the apex is placed by the assistant surgeon.

Results

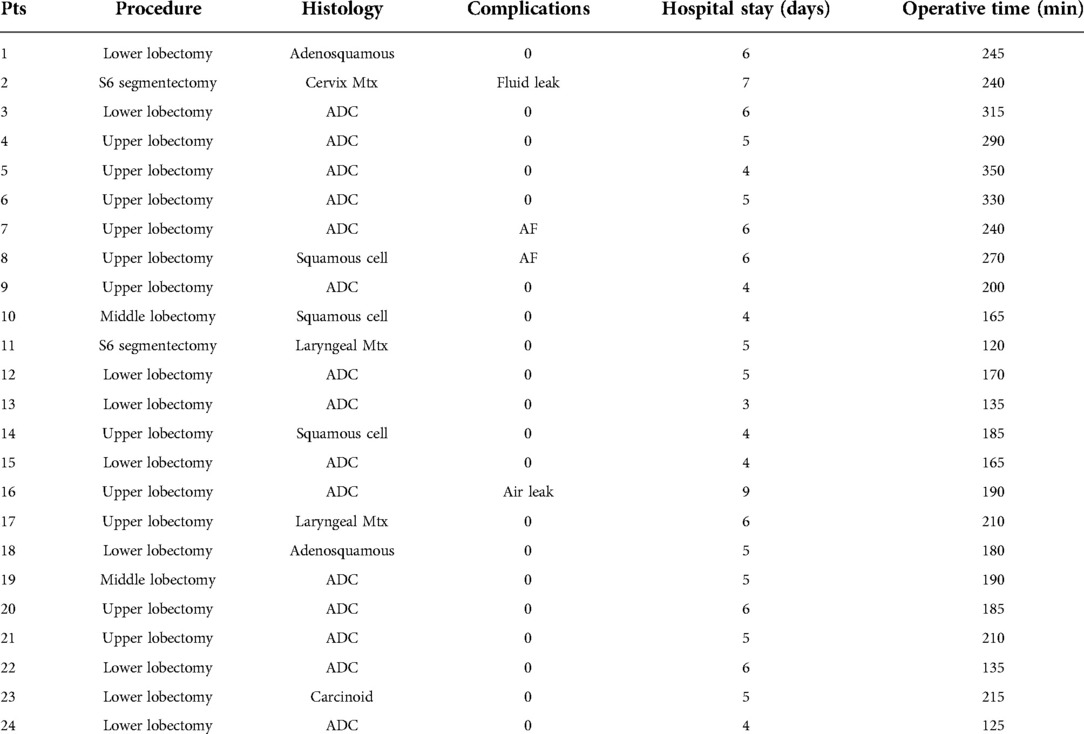

No intraoperative or perioperative mortality was observed. All procedures were completed with the uniportal approach. We performed 22 lobectomies and 2 segmentectomies; systematic hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection was accomplished in all patients but 3—the patients with secondary lesions (laryngeal and cervical cancer metastasis). Mean operative time at console including docking was 210 ± 63 min (range 120–350) (Table 2); in the last 10 cases, the operative time was significantly reduced (180 ± 30 min) compared to the first 14 cases (232 ± 72 min) (p = 0.02). No patient required blood transfusion, and the mean blood loss was 110 ± 35 ml. No patient required adjunctive administration of drugs to control postoperative pain and no opioid drugs were administered. Furthermore, the mean score of NRS measured on the first postoperative day was 2.6 (±0.6), on the third day was 1.6 (±0.7), and at discharge was 1.3 (±0.4), showing a constant decrease. In four patients (16.7%) minor complications occurred: one prolonged fluid leak (>350 cc/day) was solved spontaneously on day 6, one prolonged air leak was solved spontaneously on day 8, and two atrial fibrillation was treated with pharmacological cardioversion. The mean length of hospital stay was 5.2 ± 1 days (range 3–9). All patients performed an outpatient visit after 30 days from discharge, and in all cases, the functional recovery ranged from satisfactory to good; only two patients were referred to mild local paresthesia.

Discussion

Typical weaknesses of lung cancer patients have led the surgical community to look for less invasive techniques. Nowadays, U-VATS is the less invasive approach available in thoracic surgery and can be applied to the majority of thoracic surgery procedures, including bronchovascular resection and reconstruction (3, 4). Nevertheless, RATS experience is increasing in many Thoracic Surgery Centers due to well-known advantages such as the 3D vision, lack of physiological tremors, stability of the camera, and a shorter learning curve compared to VATS. However, the RATS technique is always described with three or four incisions plus a utility incision of 4 cm. This is certainly more invasive than the uniportal incision used in U-VATS (15), and uniportal RATS is exclusively a newborn technique that is growing nowadays (10–12).

According to our experience with U-VATS and borrowing from the experience described in the literature (10–12), we started a Uniportal RATS program at the IRCCS “Pascale Foundation” National Cancer Institute of Naples.

The great maneuverability and adaptability of the da Vinci Xi robotic system allow many tailored configurations that are of paramount importance using the system through uniportal access. Docking the system in U-RATS is certainly faster than in standard RATS because of the single incision, but it should be performed very carefully to avoid potential fighting between the robotic arms. This can be obtained by keeping a distance of 10 cm between the robotic elbows and a working angle with the chest wall greater than the ones in U-VATS. As the operative arms must cross each other inside the chest (Figure 2), to avoid damage to the ribs, it is mandatory to work as perpendicular to the target as possible. For this reason, differently from U-VATS, in which the instruments enter the chest wall anteriorly with a 45° angle, the surgical incision of U-RATS should be more posterior to allow the arms to work with a mean 70° angle with the chest wall (Figures 1A,B). Due to the intracavity crossing of the instruments, at the touchpad console, the control setting should be modified, changing the arm control, allowing the right master to control the left robotic arm and vice versa. Large movements of masters during surgery should be limited to avoid arms conflict.

Respecting these rules, vessel isolation is easy and always possible without any vessel tension or damage. However, the most time-consuming step of the procedure, in our experience, is represented by vascular stapling due to the dimensional mismatch between robotic staplers and thoracic anatomy. Most of all left upper lobe artery branches or minor right upper lobe branches can be safely managed with the robotic Hem-o-lock clips applier, being smaller and easier to be introduced in the chest. Although using the 45 Sureform Robotic stapler is feasible, it is not easy to approach the vessels and avoid external conflicts between arms and, of course, avoid tension to the vessels. In this scenario, the best equilibrium can be found by balancing the correct stapler angle with a countertraction of the underlining lung parenchyma. The use of the 30 Endowrist curved tip stapler could certainly be helpful but unfortunately it was unavailable in our institute during the study period.

In our opinion, the learning curve of this technique in U-VATS experienced surgeons is quite fast, and we found a significant shortening of the surgical time in the last 10 cases (p = 0.02), thus confirming the well-known rapid learning curve of robotic surgery. We did not record any intraoperative complication that needed conversion, but in this case, the switch from U-RATS to U-VATS or thoracotomy is certainly quicker than in standard RATS because removing three arms from a single incision is very fast, without jeopardizing the safety of the patient.

The advantages of RATS have been extensively described in the literature (16–18) and were not the focus of our paper. Still, our experience with both techniques, U-VATS and RATS, showed better postoperative pain control in U-VATS than in RATS patients. Starting from this statement and according to the frailty of our patient population, we decided to evaluate the feasibility and the efficacy of the U-RATS technique, combining the advantages of U-VATS with the well-known advantages of RATS.

The evaluation of the NRS scale was satisfactory in our series and comparable to U-VATS patients in the early postoperative time and 1 month later, confirming that the number of chest incisions is directly related to the postoperative pain, supporting the early recovery.

This technique needs to be tested on a bigger patient population, but in our early experience, we can conclude that U-RATS is certainly safe, feasible, and comparable to U-VATS in terms of postoperative pain results. It remains a time-consuming technique, but the learning curve for skilled U-VATS surgeons is quite fast; furthermore, new suturing devices could simplify the surgical steps through standardization and worldwide spreading of U-RATS.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EM contributed to the conception and design of the study and wrote the main part of the manuscript. NM contributed to the conception and design of the study and drew the figures. GL and AR organized the database. CM performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors deeply thank Prof. Marco Anile of the University of Rome “Sapienza” for his friendly contribution and professional tips.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gonzalez-Rivas D, Soultanis KM, Garcia A, Yang K, Qing Y, Yie L, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lung sparing tracheo-bronchial and carinal sleeve resections. J Thorac Dis. (2020) 12(10):6198–209. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.04.05

2. Paradela de la Morena M, De La Torre Bravos M, Fernandez Prado R, Minasyan A, Garcia-Perez A, Fernandez-Vago L, et al. Standardized surgical technique for uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2020) 58(Suppl. 1):i23–33. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa110

3. Mercadante E, Alessandrini G, Forcella D, Melis E, Gallina F, Facciolo F. Uniportal thoracoscopic left main bronchus resection with new lobar carina reconstruction. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. (2020) 2020. doi: 10.1510/mmcts.2020.039

4. Gonzalez-Rivas D, Garcia A, Chen C, Yang Y, Jiang L, Sekhniaidze D, et al. Technical aspects of uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic double sleeve bronchovascular resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2020) 58(Suppl_1):i14–22. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa037

5. Gao Y, Abulimiti A, He D, Ran A, Luo D. Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Open Med (Wars). (2021) 16(1):1228–39. doi: 10.1515/med-2021-0333

6. Li T, Xia L, Wang J, Xu S, Sun X, Xu M, et al. Uniportal versus three-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Thorac Cancer. (2021) 12(8):1147–53. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13882

7. Demos DS, Tisol WB. Robotic thoracic lymph node dissection for lung cancer. Video-Assist Thoracic Surg. (2020) 5:17. doi: 10.21037/vats.2020.01.03

8. Ricciardi S, Davini F, Zirafa CC, Melfi F. From “open” to robotic assisted thoracic surgery: why RATS and not VATS? J Vis Surg. (2018) 4:107. doi: 10.21037/jovs.2018.05.07

9. Oh DS, Tisol WB, Cesnik L, Crosby A, Cerfolio RJ. Port strategies for robot-assisted lobectomy by high-volume thoracic surgeons: a nationwide survey. Innovations (Phila). (2019) 14(6):545–52. doi: 10.1177/1556984519883643

10. Gonzalez-Rivas D, Bosinceanu M, Motas N, Manolache V. Uniportal robotic-assisted thoracic surgery for lung resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2022):ezac410. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezac410. [Epub ahead of print].35951763

11. Gonzalez-Rivas D, Manolache V, Bosinceanu ML, Gallego-Poveda J, Garcia-Perez A, de la Torre M, et al. Uniportal pure robotic-assisted thoracic surgery—technical aspects, tips and tricks. Ann Transl Med. (2022). doi: 10.21037/atm-22-1866. [Epub ahead of print].

12. Yang Y, Song L, Huang J, Cheng X, Luo Q. A uniportal right upper lobectomy by three-arm robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery using the da Vinci (Xi) Surgical System in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2021) 10(3):1571–5. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-21-207

13. Hansen HJ, Petersen RH, Christensen M. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy using a standardized anterior approach. Surg Endosc. (2011) 25(4):1263–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1355-9

14. Igai H, Kamiyoshihara M, Yoshikawa R, Osawa F, Kawatani N, Ibe T, et al. The efficacy of thoracoscopic fissureless lobectomy in patients with dense fissures. J Thorac Dis. (2016) 8(12):3691–6. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.58

15. Park BJ, Flores RM, Rusch VW. Robotic assistance for video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy: technique and initial results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2006) 131(1):54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.031

16. Kent MS, Hartwig MG, Vallières E, Abbas AE, Cerfolio RJ, Dylewski MR, et al. Pulmonary open, robotic and thoracoscopic lobectomy (PORTaL) study: an analysis of 5,721 cases. Ann Surg. (2021). doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005115. [Epub ahead of print].

17. Veronesi G, Novellis P, Voulaz E, Alloisio M. Robot-assisted surgery for lung cancer: state of the art and perspectives. Lung Cancer. (2016) 101:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.09.004

18. Yang HX, Woo KM, Sima CS, Bains MS, Adusumilli PS, Huang J, et al. Long-term survival based on the surgical approach to lobectomy for clinical stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer: comparison of robotic, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and thoracotomy lobectomy. Ann Surg. (2017) 265(2):431–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001708

Keywords: robotic thoracic surgery, rats, uniportal RATS, thoracoscopic surgery, VATS, uniportal VATS, robotic thoracic surgery (RATS)

Citation: Mercadante E, Martucci N, De Luca G, La Rocca A and La Manna C (2022) Early experience with uniportal robotic thoracic surgery lobectomy. Front. Surg. 9:1005860. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1005860

Received: 28 July 2022; Accepted: 2 September 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Calvin Sze Hang Ng, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

H.Volkan Kara, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, TurkeyAnshuman Darbari, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

© 2022 Mercadante, Martucci, De Luca, La Rocca and La Manna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Edoardo Mercadante bWVyY2FkYW50ZS5lZG9hcmRvQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Thoracic Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Surgery

†ORCID Edoardo Mercadante orcid.org/0000-0003-2101-1254

Edoardo Mercadante

Edoardo Mercadante Nicola Martucci

Nicola Martucci