95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Surg. , 09 June 2021

Sec. Visceral Surgery

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.664454

This article is part of the Research Topic Bioengineering Solutions in Surgery: Advances, applications and solutions for clinical translation View all 18 articles

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic variceal ligation + endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EVL+EIS) to control acute variceal bleeding (AVB).

Methods: Online databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Biology Medicine (CBM) disc, VIP, and Wanfang, were searched to identify the studies comparing the differences between EVB+EIS and EVB, EIS from the inception of the databases up to December 30, 2020. STATA 13.0 was used for the meta-analysis.

Results: A total of eight studies involving 595 patients (317 patients in the EVL group and 278 patients in the EVL+EIS group) were included. The results of the meta-analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences in the efficacy of acute bleeding control (P = 0.981), overall rebleeding (P = 0.415), variceal eradication (P = 0.960), and overall mortality (P = 0.314), but a significant difference was noted in the overall complications (P = 0.01).

Conclusion: EVL is superior to the combination of EVL and EIS in safety, while no statistically significant differences were detected in efficacy. Further studies should be designed with a large sample size, multiple centers, and randomized controlled trials to assess both clinical interventions.

Esophagogastric variceal bleeding (EVB) is the most dangerous complication of decompensated cirrhosis (1). Most of the patients with liver cirrhosis have symptoms of esophagogastric varices, with an increase in the incidence by 7% per year (2). EVB is the main influencing factor for the increased mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis (3). The mortality of the first bleeding was about 20–30% if an active intervention was not carried out (4). Within 2 years after the first bleeding, the rebleeding rate and mortality increased significantly, which threatened the safety of patients (5). However, the secondary prevention of EVB in liver cirrhosis mainly includes endoscopic treatment, non-selective beta-blocker drugs (NSBBs), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and surgical treatment (6); all these methods have limited curative effects. Although the evidence is not convincing, guidelines recommend the use of ligation and vasoactive drugs as first-line therapy for acute variceal bleeding (AVB) (7).

In the development of endoscopic therapy technology, sclerosing agent injection, tissue glue injection, vein ligation, and several other technical methods have emerged gradually to control acute bleeding and prevent rebleeding (8). Previous studies and meta-analyses have shown that vasoactive drugs and sclerotherapy are better than sclerotherapy alone (9). However, the clinical outcomes were not evaluated with respect to endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) combined with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS). Thus, we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy and safety of EVL+EIS to control AVB.

(1) Patients: Liver cirrhosis patients with AVB >18 years old. Among them, nationality and race. are not limited.

(2) Interventions: Clinical interventions are EVB combined with EIS, EVB, or EIS.

(3) Outcomes: Bleeding control rate, risk of overall rebleeding, rebleeding rate, overall mortality, and complications.

(4) Study design: Types of included studies are retrospective, prospective, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

(1) Patients with hepatocellular cell carcinoma or other malignancies.

(2) Publications based on animal experiments.

(3) Duplication, abstract, conference papers, and articles without detailed data were also excluded.

The online databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Biology Medicine disc (CBM), VIP, and Wanfang, were searched, and the studies that compared the differences between EVB combined with EIS and EVB, EIS were identified from the inception of the databases up to December 30, 2020. Free terms and subject terms were combined, and the language was restricted to English and Chinese. The key search words were “endoscopic variceal ligation,” “endoscopic injection sclerotherapy,” “EVL,” “EIS,” “cirrhosis,” “esophageal variceal bleeding.”

Two researchers extracted the data from the studies independently. The information included the following: (1) General characteristics of the included studies: authors, country, study design, sample size, mean age, the main cause of cirrhosis, and Child–Pugh score; (2) Outcomes: efficacy of bleeding control, overall rebleeding rate, overall mortality, variceal eradication, and complications.

The methodological quality and bias assessment were completed by two reviewers. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool, which rates seven items as high, low, or unclear for risk of bias (10). These items include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias.

STATA 13.0 was used for the meta-analysis. χ2-test and I2-test are used to determine the heterogeneity among the studies. If I2 <50%, P > 0.1, there is no heterogeneity in the data analysis, and a fixed-effects model was used; if not, the random-effects model assessed the different causes of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was carried out when the subgroup analysis was not satisfactory, and it was employed to evaluate the robustness of the main results.

A total of 368 records were searched in online databases. After assessing the titles and abstracts, 211 studies were identified as eligible citations. Full-text reading retrieved eight studies (11–18) involving 595 patients (317 patients in the EVL group and 278 patients in the EVL+EIS group) (Figure 1).

Among the eight included studies, three were from the USA, and five were designed as RCTs. The main courses of cirrhosis were hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and alcohol. The characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 1.

None of the included studies were assessed to have a low risk of bias in all the seven items of the Cochrane Collaboration tool (Figure 2). The majority of the studies were high risk for random sequence generation and for other sources of bias (Figure 3). Studies scored high risk for other sources of bias with respect to concerns, such as baseline differences and industry funding. Most of the studies had an unclear risk of bias for selective outcome reporting, and a few had registered protocols.

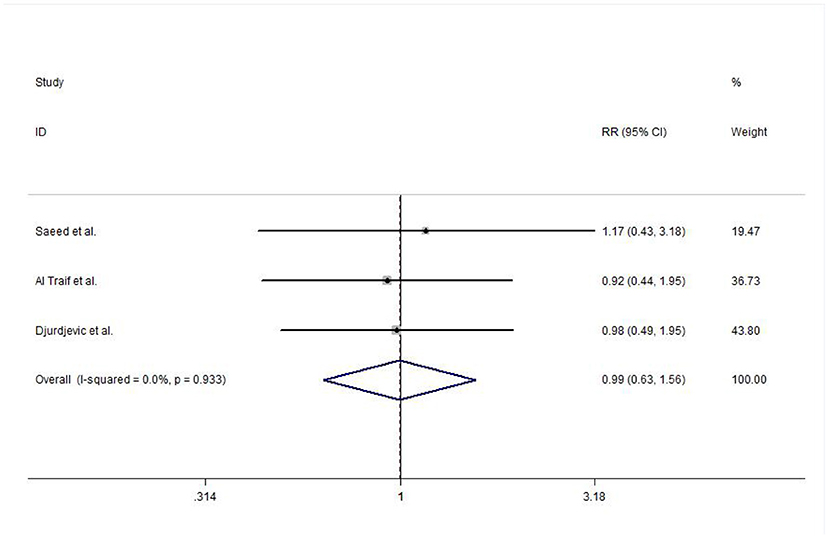

In this meta-analysis, three studies reported the efficacy of acute bleeding control. No heterogeneity was detected between studies (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.933), and the meta-analysis was conducted using a fixed-effects model. The results did not show any significant difference between EVL and EVL+EIS interventions (risk ratio (RR) = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.63–1.56, P = 0.981; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing EVL and EVL+EIS with respect to the efficacy of acute bleeding control. EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation.

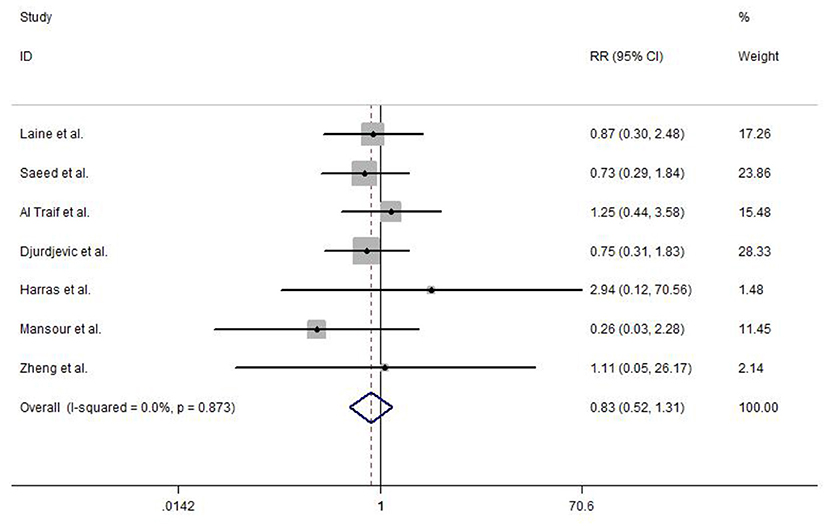

An overall rebleeding was reported in seven included studies, and no heterogeneity was observed between studies (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.873). The meta-analysis was conducted using a fixed-effects model. No statistically significant difference was detected in EVL and EVL+EIS (RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.52–1.31, P = 0.415; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing EVL and EVL+EIS in overall rebleeding. EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation.

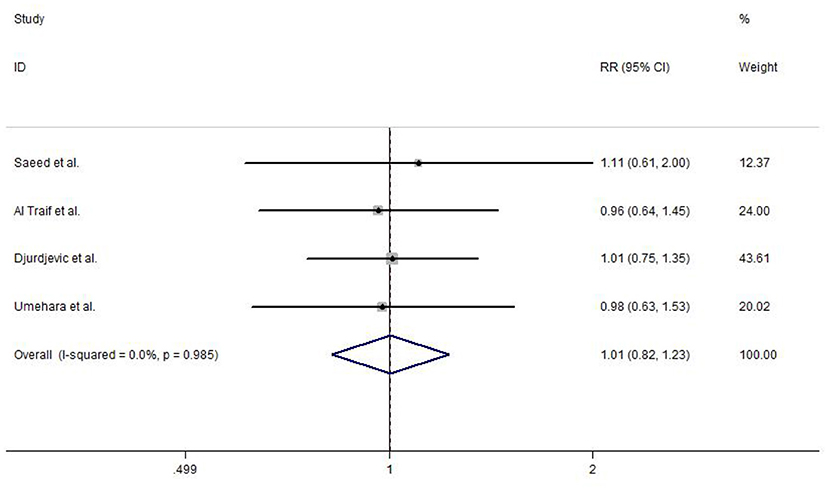

Among the included studies, four reported variceal eradication. The meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model (study heterogeneity: I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.985) did not detect any statistically significant difference in EVL and EVL+EIS (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.82–1.23, P = 0.960; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing EVL and EVL+EIS in variceal eradication. EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation.

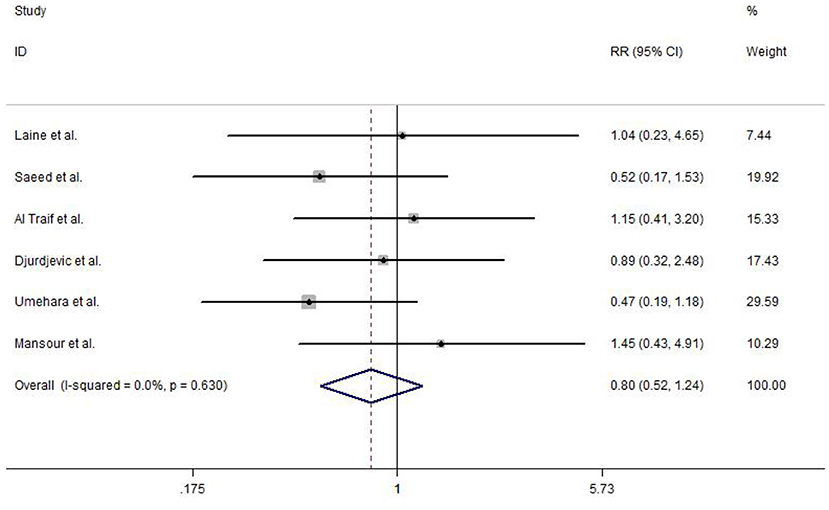

The overall mortality was reported in six included studies. No heterogeneity test was observed between studies (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.630), and hence, a fixed-effects model was used to analyze the data. Strikingly, no statistically significant difference was detected in EVL and EVL+EIS (RR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.52–1.24, P = 0.314; Figure 7).

Figure 7. Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing EVL and EVL+EIS in overall mortality. EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation.

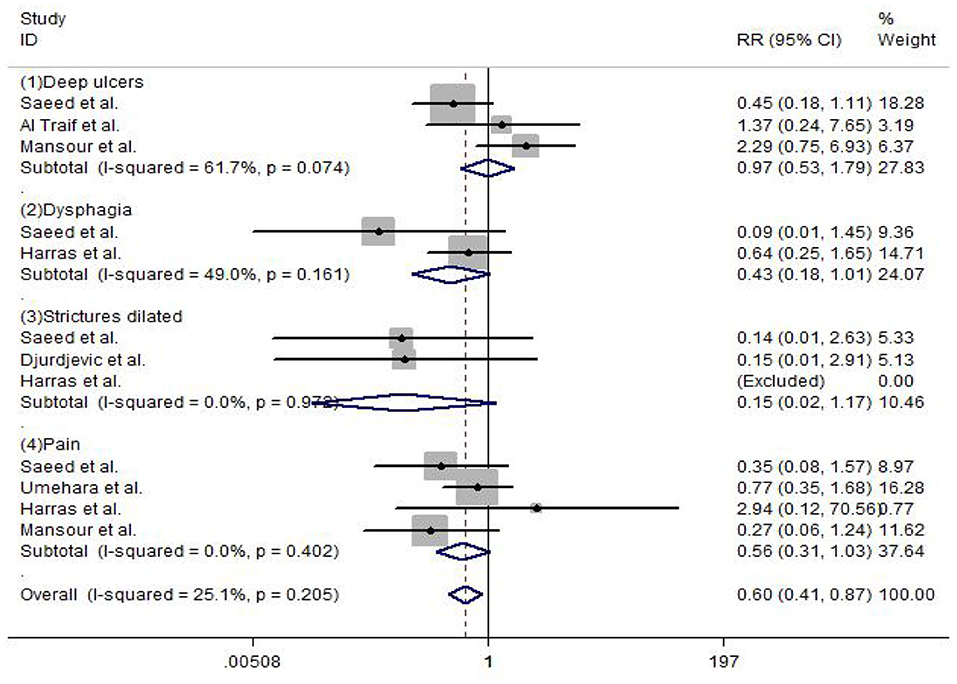

Complications were reported in the included studies. The results of the meta-analysis show that deep ulcers (RR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.53–1.79, P = 0.247), dysphagia (RR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.18–1.01, P = 0.106), strictures dilated (RR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.02–1.17, P = 0.353), and pain (RR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.31–1.03, P = 0.124) did not show any significant difference between EVL and EVL+EIS, but the overall complication rate (RR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.41–0.87, P = 0.01) had a statistically significant difference between EVL and EVL+EIS interventions (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing EVL and EVL+EIS in complications. EIS, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation.

EVB patients have a high risk of rebleeding and death after bleeding control (19). If the EVB patients do not receive secondary preventive treatment for 1–2 years, the rebleeding rate is elevated to about 60%, and the mortality rate is 33% (20). At present, EVL and EIS are indispensable in the endoscopic treatment of the secondary prevention of EVB. The basic goal of the treatment is to eradicate or reduce the degree of esophageal varices in order to reduce the recurrence rate and mortality (21). Patients with a history of EVB should be treated routinely by endoscopy, and patients with acute EVB should continue to receive corresponding endoscopic treatment after the termination of bleeding (22).

In EVL technology, the negative pressure at the front end of the endoscope is inhaled into the esophageal varices that are then ligated with a rubber ring in the transparent cap (7). The physical ligation blocks the blood supply of the varices, resulting in thrombosis, tissue necrosis, and ulcers, finally leaving healing scars for the treatment and elimination of varices (23). EIS refers to the injection of a sclerosing agent into the tissue of varicose vein or adjacent to varicose vein, which shows ischemia and necrosis in the tissue of varicose vein, and then produces fibrosis, to eliminate varicose veins (24). With the continuous development of endoscopic technology and the evolution of sclerosing agents, the clinical application of EVL and EVs is also evolving (25).

The present meta-analysis did not detect any statistically significant difference in the efficacy of acute bleeding control (RR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.63–1.56, P = 0.981), overall rebleeding (RR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.52–1.31, P = 0.415), variceal eradication (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.82–1.23, P = 0.960), and overall mortality (RR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.52–1.24, P = 0.314), but a significant difference was observed in the overall complications (RR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.41–0.87, P = 0.01). The main complications of EVL include chest pain or discomfort, dysphagia or pain, and erosion or ulcer at the ligation site, infection, or bacteremia (26). Rubber bands falling off and sliding can also form ulcers and after rebleeding (27). Compared to EVL alone, the effect of EIS combined with EVL varies in different studies. In patients with active bleeding, EVL uses ligation device, which limits the intraoperative field of vision, raising the technical requirements of endoscopic operators (28).

Due to various conditions, the present meta-analysis has some limitations. Firstly, the included studies were from different countries. Secondly, the frequency of follow-up and the total duration of follow-up were also incompatible. Thirdly, some disparities in medical technology and medical facilities were observed in the included literature. Therefore, EVL and EVs may show similar results in the treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding.

In conclusion, EVL is superior to the combination of EVL and EIS in safety, while no significant differences were noted in efficacy. Nonetheless, further studies should be designed based on a large sample size, multiple centers, RCTs to substantiate these two clinical interventions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

JS and HZ contributed to the conceptualization, project administration, and writing and review. JS and MR contributed to the data curation. YX and YY contributed to the data analysis. JS, HZ, and LL contributed to the methodology. HZ and MR contributed resources. YX and LL contributed the software. HZ contributed to the supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Wu LF, Xiang XX, Bai DS, Jin SJ, Zhang C, Zhou BH, et al. Novel noninvasive liver fibrotic markers to predict postoperative re-bleeding after laparoscopic splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection: a 1-year prospective study. Surg Endosc. (2020). doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08111-4

2. Moon AM, Green PK, Rockey DC, Berry K, Ioannou GN. Hepatitis C eradication with direct-acting anti-virals reduces the risk of variceal bleeding. Alimentary Pharmacol Therap. (2020) 51:364–73. doi: 10.1111/apt.15586

3. Tantai XX, Liu N, Yang LB, Wei ZC, Xiao CL, Song YH, et al. Prognostic value of risk scoring systems for cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. (2019) 25:6668–80. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i45.6668

4. Lin L, Cui B, Deng Y, Jiang X, Liu W, Sun C. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitor in cirrhotics with variceal bleeding: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Digestion. (2020) 102:117–27. doi: 10.1159/000505059

5. Rogalski P, Rogalska-Plonska M, Wroblewski E, Kostecka-Roslen I, Dabrowska M. Laboratory evidence for hypercoagulability in cirrhotic patients with history of variceal bleeding. Thromb Res. (2019) 178:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.03.021

6. Sohn H, Park S, Kang Y, Koh H, Han SJ, Kim S. Predicting variceal bleeding in patients with biliary atresia. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2019) 54:1385–90. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1683225

7. Onofrio FQ, Pereira-Lima JC, Valença FM, Azeredo-da-Silva ALF, Tetelbom Stein A. Efficacy of endoscopic treatments for acute esophageal variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. (2019) 7:E1503–14. doi: 10.1055/a-0901-7146

8. Yoo JJ, Kim SG, Kim YS, Lee B, Jeong SW, Jang JY, et al. Propranolol plus endoscopic ligation for variceal bleeding in patients with significant ascites: propensity score matching analysis. Medicine. (2020) 99:e18913. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018913

9. Xu HB, An ZT, Xuan J, Wen W. Evidence-based endoscopic treatment of esophagogastric variceal bleeding. World Chin J Digestol. (2017) 25:1558. doi: 10.11569/wcjd.v25.i17.1558

10. Higgins JPT, Green S (editors.). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration (2011). Available online at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (accessed November 2, 2017).

11. Laine L, Stein C, Sharma V. Randomized comparison of ligation versus ligation plus sclerotherapy in patients with bleeding esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. (1996) 110:529–33. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566601

12. Saeed ZA, Stiegmann GV, Ramirez FC, Reveille RM, Goff JS, Hepps KS. Endoscopic variceal ligation is superior to combined ligation and sclerotherapy for esophageal varices: a multicenter prospective randomized trial. Hepatology. (1997) 25:71–4 doi: 10.1002/hep.510250113

13. Traif IA, Fachartz FS, Jumah AA, Johan MA, Omair AA, Bakr FA, et al. Randomized trial of ligation versus combined ligation and sclerotherapy for bleeding esophageal varices. Gastrointestinal Endosc. (1999) 50:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70335-4

14. Djurdjevic D, Janosevic S, Dapcevic B, Vukcevic V, Djordjevic D, Svorcan P, et al. Combined ligation and sclerotherapy versus ligation alone for eradication of bleeding esophageal varices: a randomized and prospective trial. Endoscopy. (1999) 31:286–90. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-22

15. Umehara M, Onda M, Tajiri T, Toba M, Yoshida H, Yamashita K. Sclerotherapy plus ligation versus ligation for the treatment of esophageal varices: a prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endoscopy. (1999) 50:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70336-6

16. Harras F, Shetael S, Shehata M, El Saadany S, Selim M, Mansour L. Endoscopic band ligation plus argon plasma coagulation versus scleroligation for eradication of esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2010) 25:1058–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06265.x

17. Mansour L, El-Kalla F, El-Bassat H, Abd-Elsalam S, El-Bedewy M, Kobtan A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of scleroligation versus band ligation alone for eradication of gastroesophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. (2017) 86:307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.026

18. Zheng J, Zhang Y, Li P, Zhang S, Li Y, Li L, et al. The endoscopic ultrasound probe findings in prediction of esophageal variceal recurrence after endoscopic variceal eradication therapies in cirrhotic patients: a cohort prospective study]. BMC Gastroenterol. (2019) 19:32. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0943-y

19. Miao Z, Lu J, Yan J, Lu L, Ye B, Gu M. Comparison of therapies for primary prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology. (2019) 69:1657–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.30220

20. Koya Y, Shibata M, Watanabe T, Kumei S, Miyagawa K, Oe S, et al. Influence of gastroesophageal flap valve on esophageal variceal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Endosc. (2021) 33:100–9. doi: 10.1111/den.13685

21. Bledar K, Iris M, Akshija I, Koçollari A, Prifti S, Burazeri G. Predictors of esophageal varices and first variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis patient. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:4806–14. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4806

22. Carolina Mangas-Sanjuan, Belén Martínez-Moreno, Bozhychko M. Over-the-scope clip for acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Dig Endosc. (2019) 31:712–6. doi: 10.1111/den.13493

23. Suh JI. Are there seasonal variations in the incidence and mortality of esophageal variceal bleeding?. Clin Endosc. (2020) 53:107–9. doi: 10.5946/ce.2020.042

24. Lu Z, Sun X, Zhang W, Jin B, Han J, Wang Y. Second urgent endoscopy within 48-hour benefits cirrhosis patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Medicine. (2020) 99:e19485. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019485

25. Laine L. Primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding: an endoscopic approach. J Hepatol. (2010) 52:944–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.035

26. Salman AA, Shaaban ED, Atallah M, Yousef M, Ahmed RA, Ashoush O, et al. Long-term outcome after endoscopic ligation of acute esophageal variceal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Acta Gerontol. (2020) 83:373–80.

27. Dy SM, Cromwell DM, Thuluvath PJ, Bass EB. Hospital experience and outcomes for esophageal variceal bleeding. Int J Qual Health Care. (2003) 15:139–46. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg016

Keywords: esophagogastric variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal ligation, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, cirrhosis, meta- analysis

Citation: Su J, Zhang H, Ren M, Xing Y, Yin Y and Liu L (2021) Efficacy and Safety of Ligation Combined With Sclerotherapy for Patients With Acute Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in Cirrhosis: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Surg. 8:664454. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.664454

Received: 05 February 2021; Accepted: 22 March 2021;

Published: 09 June 2021.

Edited by:

Claudia Di Bella, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Xu Wei, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Su, Zhang, Ren, Xing, Yin and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huilin Zhang, cHJvZmhsemhhbmdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.