95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Energy Policy , 23 May 2024

Sec. Energy and Society

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsuep.2024.1390570

Introduction: The Skidmore Review of UK Government's net zero approach highlights a lack of a national framework which establishes local government role, responsibilities and area-based governance arrangements. Although unified political leadership agreed as part of devolution deals has helped some areas to marshal resources and support, the national delivery landscape for net zero remains patchy. This study develops a toolkit to help local areas improve local arrangements.

Methods: A mixed methods research approach has been used to develop the toolkit. It incorporates a set of governance models, a method for assessing the values of good governance, a governance improvement process and an illustration of how the toolkit can be employed using three cases where the two-tier public administrative structure applies.

Results: Results from the research process suggest that although change is happening it lacks the coherence and scale needed, with non-urban multiple-tier public administrations getting left behind by their metropolitan, single-tier counterparts creating a credibility and performance gap between political rhetoric and local net zero delivery. This observed inertia highlights the need to change governance processes and practices if public administration is going to deliver its part of net zero effectively outside the UK Metropolitan areas.

Discussion: The gap in support for local government to develop net zero governance arrangements is well recognized in both this research and publicly funded research programmes. This study provides UK local authorities with a simple, effective toolkit, that could potentially help them build strong wider societal relationships that will assist them in playing their full part in the UK reaching net zero.

Local government is seen by many as key to delivering the United Kingdom's statutory obligations to climate change in the context of reducing the country's greenhouse gas emissions contribution to net zero by 2050 (Climate Change Committee, 2022; Skidmore, 2022). Local authorities have a diverse range of powers and duties available to them to achieve organizational and area-wide decarbonization using services delivered within defined legal, constitutional and democratic decision-making structures. However, their ability to play their part has been heavily constrained through what Tingey and Webb (2020, p. 2) describe as “neoliberal governance reforms” which have moved authority away from the regions to central government alongside more than two decades of budgetary pressure (Davis, 2021). This will continue to adversely impact the availability of financial and human capital needed well into the late 2020s (Hoddinott et al., 2022). This has led to what Lowndes and Pratchett (2012) describe as “austerity localism” where “local authorities themselves… have to mete out the cuts” (Ferry and Ahrens, 2017, p. 550).

Compared to other parts of England, the larger cities and metropolitan areas have tended to lead the way with more unified approaches to area-wide decarbonization, in part as a consequence of having coordinating administrative structures in the form of a Combined Authority able to function under single political leadership (Greater Manchester Combined Authority, 2024) and robust net zero partnerships like Energy Capital (West Midlands Combined Authority, 2021). Public-private partnerships, like that between Bristol City Council and Vattenfall-Ameresco (Bristol City Council, 2022), have been created as one potential long-term solution to area-wide decarbonization. To date, these arrangements both reflect and have received impetus from local political endorsement of Climate Emergency Declarations (Climate Emergency UK, 2023). Although 82% of UK emissions are considered within the scope of influence of local authorities (HM Government, 2021), central government currently shows no appetite for a unifying statutory mandate for local authorities to deliver net zero in their administrative areas nor any coherent financial provision or resources for this purpose (Billington et al., 2020). Rather, Central Government sees the devolution framework, established by the Localism Act 2011, as a key opportunity for “innovative local proposals to deliver action on climate change and the UK's Net Zero targets” (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Ministry of Housing Communities, 2023, p. 18).

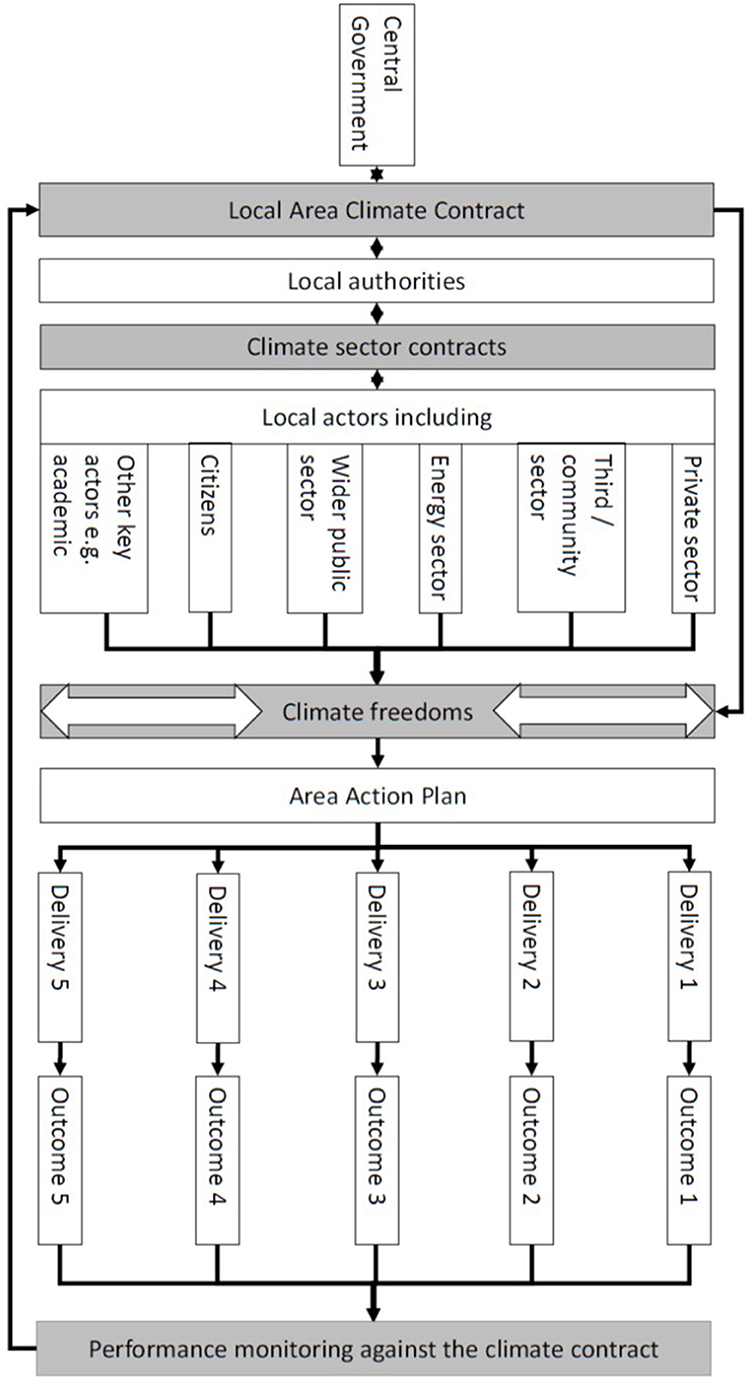

Devolution in England has focused on larger conurbations with net zero governance and delivery a recent addition to their devolution deals as they undergo a refresh (HM Government/West Midlands Combined Authority, 2023). The process of devolution is extending beyond the metropolitan areas into the shire counties through the County Deal where two-tier administration predominates (County Councils Network, 2022). However, beyond the metropolitan areas, local public administration demonstrates varied structures across England where two autonomous tiers of government prevail. Excluding the lowest parish tier, of the 317 local authorities in England there are twenty-one county councils and 164 district or borough councils in the two-tier structure each with different responsibilities, governance and delivery arrangements. Central Government does not endorse a single governance model and expects local areas to produce their own solutions. This governance vacuum has created, as Christie and Russell (2023, p. 78) describe, a landscape of “compensatory and improvisational governance for climate action” across England. Previous research by the authors started to address the gap by proposing a net zero governance framework built around the concept of a “Local Area Climate Contract” functioning within a new governance framework of cooperation based on agreed “Climate Freedoms” (Figure 1). This paper aims to help to address the problem by illustrating model arrangements that local councils could draw upon to improve their net zero governance arrangements. The research presented in this paper provides an illustrative suite of models along with a values-based method and governance development process to help councils more systematically diagnose and improve local net zero governance.

Figure 1. A proposed governance framework incorporating a “Climate Contract” between central government and the local Climate Emergency area (Gudde et al., 2021). Arrows represent flexibility around the climate freedoms that may be agreed based on local context and performance. Gray boxes denote proposed components.

There is both a rich and deep academic research tradition exploring the theory and practice of Governing and Governance. Kooiman (1993) in Adger and Jordan (2009, p. 6) declares that governing and governance should be viewed as very different concepts despite their common interchangeability of use by some in different contexts and applications (Lynn et al., 2000), where governing centers on interactions which “seek to “guide, steer, control, or manage” while governance describes the “patterns that emerge” as different participants engage within a set of defined behaviors, norms and practice.

In the context of political public administration Howlett et al. (2009, p. 385) define governing as “what governments do, that is controlling the allocation of resources between social actors” and governance as “providing a set of rules and operating a set of institutions setting out “who gets what, where, when, and how” in society. The conventional view is that Governance is “the means by which an activity or ensemble of activities is controlled or directed” (Pierre, 2000, p. 24). As political institutions acting under statute, there is a rational argument in favor of local public administration playing a lead role in place-centered governance arrangements (Lynn et al., 2000). It is, however, overly simplistic to confine these two concepts to public administration alone with focus only on the relationships that exist between governmental and non-governmental actors in the most traditional sense (Howlett et al., 2009, p. 385).

Bridge and Perreault (2009) see Governance as both dimensionless yet paradoxically also all about scale where specific arrangements are inherently defined by the locality while bibx1 (2009, p. 11) consider it as “not tied to a particular period of time or geographical place'. However, the concept of a coherent hierarchy of governance arrangements, where overlapping powers, bureaucracies and interests operate together effectively is a rarely discussed in the literature. Rather, as Boudon (Cited in Hamman, 2005) says “when size changes, things change.”

When defining, delineating or evaluating models of governance, although there is extensive theoretical consideration across disciplines including political and social science, organizational development, economics and more recently sustainable development, there is no single categorization or nomenclature in the literature that predominates (Williamson, 1985; Thompson et al., 1991; Lowndes and Pratchett, 2012; Lange et al., 2013). Building on the work of Williamson (1985) and Thompson et al. (1991) who propose Hierarchical, Market and Network forms, Kooiman (2003) develops a hierarchical governance framework in which governmental and non-governmental actors are involved in governing activities. This form contrasts classical notions of “top-down government” moving toward networks of state and non-state actors who are jointly involved in steering or “governing” specific activities (Sibeon, 2000). Lange et al. (2013) conclude that the academic literature describes a shift away from governing by a public administrative elite toward an increasingly shared responsibility of “state, market and civil society” (ibid., p. 404).

Some authors have recognized that attempts to conceptualize models of governance in the wider field of sustainability fall short of addressing their “inherent complexity” due to the “dynamic relations” between political processes, institutional structures and policy content (Hillman et al., 2011; Lange et al., 2013, p. 404). This is made even more challenging where public administrative institutions are forced to respond to highly disruptive external stimuli like climate change and net zero (Rittel and Webber, 1973; Termeer et al., 2015; Alford and Head, 2017) which transcend conventional politico-geographical boundaries leading to calls for a “poly-centric” approach (Ostrom, 2010), consideration in the academic literature to “Multi-level” governance models (Christie and Russell, 2023) and the emergence of a “governance mesh” characterized by the removal of hierarchy through digitalization and decentralization and the breakdown of previously demarcated boundaries to problems and solutions (Mulgan, 2020).

The roots of local net zero governance practice, extend back over three decades with local government an active participant in tackling climate change under various mandatory and voluntary initiatives each requiring some form of structure within which to operate. The Local Agenda 21, borne out of the Rio Earth Summit. led to the formation of new or repurposing of existing “partnerships” and “forums” (Lucas et al., 2003) as mainly flexible affiliations between councils, sectoral institutions and the publics with focus on the sustainable development principles set out emerging from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992 (United Nations, 1992). The Climate Emergency declarations witnessed in the UK are as a response to the Twenty-first Conference of Parties (COP21), the resultant climate activism and UK Government passing into law its net zero target, brought forward a range of public engagement as well as institutional arrangements (UK Climate Assembly, 2020). The emergence of Local Area Energy Plans as a tool for locational energy system change and decarbonization has recently stimulated public administrations to establish relationships and transactional arrangements in the absence of any guiding governance model (Collins and Walker, 2023) with calls for a “strong governance and social process to enable implementation” (Evans, 2020, p. 96). However, these “collaborative processes by themselves are insufficient in maintaining energy democracy principles in the energy transition,” requiring “institutional embedding of participative facilitation and consensus building” (Berthod et al., 2022, p. 551).

Research into net zero governance in the UK has tended to focus on the high-level relational framework between the mandated national and non-mandated local governments in England or establishing a generic model for local areas. UK Research and Innovation identified three high level governance models; centrally led, locally led or a hybrid of the two, concluding that “a hybrid model, where a central guiding framework is complemented by locally coordinated action and support by regional specialist hubs, has the most potential for impact” (Innovate UK, 2022, p. 8). Regen and Scottish and Southern Electricity Network (2020) outlined a governance model with, at its heart, a board comprising of multiple stakeholders drawn from across society with the aim of inspiring, enabling and monitoring net zero activity. The drawback of such research is 3-fold; firstly, their evidence base tends to be derived from the larger conurbations and as a result may not fully reflect the diversity of public administrative contexts observed across England. Secondly, although the recommendations tendered in the research are robust and relevant, they do not provide either the specificity or applicability to enable local areas to implement change. Finally, the current financial state of local authorities means that, even if they have the will to improve their net zero arrangements, many councils do not have the resources to make those changes without simple and cost-effective tools to guide them.

Based on a mixed-methods approach, the paper presents a net zero governance development toolkit, supported by illustrations of how it could be used by local authorities wishing to improve local net zero governance arrangements. We have built on the governance framework presented in Figure 1 which focussed on the overarching relationships between the state and local area stakeholders (Section 2.2). We have used both academic and gray research literature, published records of institutions involved in net zero delivery, and interviews with practitioners from public administration and non-governmental institutions (Section 2.4) to develop three toolkit components: a suite of models abstracted from theory and real-world examples (Section 2.3); a values-based performance evaluation criteria derived from a range of sectors which allows comparison of strengths and weaknesses within and between different governance arrangements (Section 2.5); and a governance development process (Section 2.6). The evaluation process provides a way for local authorities and others to identify how local governance can be improved both by comparison to the models and against arrangements in other localities, providing the basis for a maturity assessment which are commonly used to assess organizational performance in the public sector (Good Governance Institute, 2022). We have limited our exploration of the models and case studies to demonstrate how the processes that have been set out could be used recognizing that further independent, robust validation and testing will be needed to generate authoritative results. We set out potential solutions to address this validation stage in Section 3.

UK local authorities have no formal role in the energy system or decarbonization (Bulkeley and Kern, 2006). However, the local political appetite to play their part is clear with 394 local authorities declaring Climate Emergencies with 322 councils setting net zero targets or carbon neutrality, noting that these are distinctly different in meaning, ahead of the national legally binding 2050 target (mySociety, 2024). To address this lack of national mandate, we proposed in previously published research a governance framework which sets out a suite of relationships between national government and the local area with the local authority as the responsible local party managing the delivery arrangements through two-way agreements or contracts (Gudde et al., 2021). Our framework has some of the characteristics of the current tranche of Trailblazer Devolution deals that are currently being negotiated between central government and some of the fore-runner metropolitan regions and counties and the Freeport and Investment Zone programmes (UK Government, 2023). The framework did not, however, address the structures that could be adopted by local areas or recognition of the journey that local authorities would have to take to develop robust governance arrangements to deliver on their net zero commitments. Our governance framework is, therefore, used in this research as a way of contextualizing models of governance which, when assessed using our criteria-based scoring process, can help to identify the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model and how these can be used to evaluate local area governance.

To inform and derive the models of governance, we undertook an academic and gray literature review and interviews of practitioners operating within both climate and non-climate governance structures across the UK. We restricted our research to the UK context to address any issues of cultural incompatibility. The research was not confined to the energy or net zero disciplines allowing inclusion of examples from the health sector and economic and investment policy disciplines to be included. Key features of the arrangements were categorized and abstracted to develop a set of models for further consideration.

We subsequently focussed on the local authority perspective, drawing on information and insights from a range of sources; published literature, local authority records, the Climate Emergency UK website (Climate Emergency UK, 2023) and associated mySociety Climate Action Plan Explorer (mySociety, 2024). The Climate Emergency UK database is an inventory of climate emergency declarations and supporting material uploaded either by the declaring local authority or by volunteers. Of relevance from the published literature was research commissioned by the East of England Local Government Association which reviewed climate change partnerships across the study area chosen for our wider programme of research (Sustainability West Midlands, 2022).

The value of first-hand accounts of practitioners through semi-structured interviews is recognized by others to give voice to those dealing with the issues on a day-day-day basis (Kuzemko and Britton, 2020). We interviewed nine representatives across the sectors; three were interviewed between September and November 2021 as part of previous research while a further six were interviewed between November 2022 and July 2023. Fifteen local authority staff with direct experience of the governance and decision-making processes of organizations included in the assessment process were interviewed during 2022 and 2023. This approach provided direct insight of the challenges faced.

All interviews followed a semi-structured format with each recorded, transcribed and reviewed by the researchers to correct any mis-transcription prior to uploading into the NVivo™ qualitative analysis software (Release 1.5.2). Key text was coded against a classification developed for this research to thematically group components of each transcript. The output informed the research teams understanding of firstly the internal governance of local authorities applying to net zero delivery, the resources that are being used and the barriers that are being faced. It also helped inform the research on the state of inter-authority working and engagement with stakeholders from other sectors of society in each case study area.

A literature review provided a set of theoretical and empirical standpoints from which governance frameworks could be assessed to determine their strengths and weaknesses. No minimum number of methods was set, with the researchers using a pragmatic judgement on when “enough was enough'. A “saturation” point was reached when the same characteristics of good governance were observed.

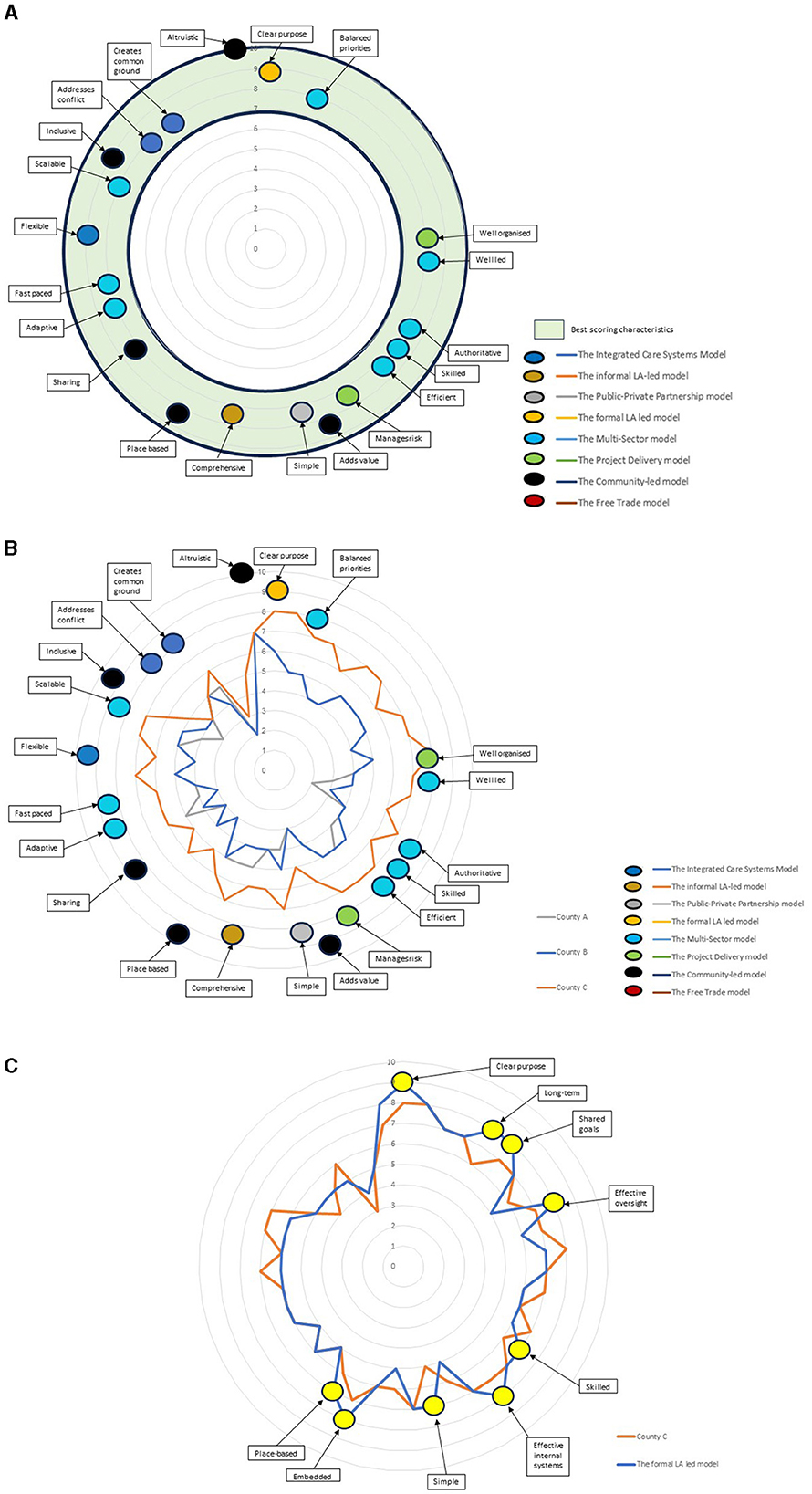

The governance characteristics were converted into challenge statements, taking the form of a question “How well does the model deliver on ….?”. The eight governance models were assessed by the research team with each challenge statement receiving a score using the 0-10 Likert scale, with 0 representing “not at all” and 10 “ideal'. The resulting scores for each model were aggregated and normalized to a percentage to allow different governance arrangements to be compared. The individual Likert scores for each characteristic were plotted as radar graphs to reveal the strongest and weakest for each model being assessed. In addition, where a model scored highest for a specific characteristic was used as the “best demonstrated” when analyzing locality governance arrangements.

The process that was followed generated illustrative results which are presented in Section 4. Limitations of the method are acknowledged given that the research team will have introduced bias; a decision was taken not to weight the characteristics with a proposal that local areas could choose to place their own weightings based on the specific circumstances and context of the area and perspectives of stakeholders. The Lickert scale-based process used to evaluate the models and local governance arrangements is an inherently subjective activity. Recommendations considering how to validate the models and assess their relative strengths and weaknesses are made in Section 6.

To illustrate the evaluation process and use of the models, we selected three local authority-led partnerships whose administrative characteristics and net zero ambitions typified that seen across other multi-tier areas in England (Table 1).

Their net zero ambitions, plans and associated governance arrangements were identified using both desk-based research and practitioner interviews. Within each area, the Climate Emergency declarations or equivalent net zero political commitments and associated action plans of each constituent district or county council were reviewed along with the governance and decision-making arrangements of any partnership that had been established for the purposes of coordinating net zero activity.

In their review and subsequent development of a model to assess transnational energy partnerships, Szulecki et al. (2011) refer to competing hypotheses derived from different schools of institutional research which explain their effectiveness; the first hypothesis posits that the quality and strength of the partners and the power that actors wield are key determinants while the second argues that it is the internal structures that are key, that “partnership design matters” (ibid., p. 716). Taking this further, assessing governance arrangements, whether of a partnership or other institutional constructs covered by this research, according to the values that they demonstrate could be mistaken for an analysis of their effectiveness to deliver the defined outputs that they were set up to achieve (Biermann et al., 2007). Part of the challenge facing analysts and designers of appropriate governance structures is their “complexity and ambiguity of the governance concept and its fundamental properties” with “multiple connotations” dependent in part on the perspective of those undertaking the analysis (Hillman et al., 2011, p. 408). We chose to take a heuristic approach to address this system complexity which reflected the literature in the empirical-analytical field of sustainability governance (Lange et al., 2013).

Our research identified both theoretical and real-world governance arrangements, from which we selected nineteen examples for closer attention. Each example was described and their key features of the arrangements delineated; these included which sector is taking the lead role, the level of formality of the arrangements, the role of local authorities and democratic leadership, the range and scope of other stakeholders in area-wide decision-making and delivery, and the level of decentralization. We then categorized them based on their sectoral derivations and attributes to derive eight illustrative models (Table 2). The research did not specifically consider the track records of each example on which the models were based; rather, we were concerned with the characteristics which they exhibited. Although a limitation, it was a feature of the literature review that no single successful model could be identified or translated from another domain to net zero. It was also noted that many of arrangements had been tried and discarded by others while some that were identified in this research had not run for sufficient time to demonstrate their performance.

Based on our search, ten methodologies were identified from the disciplines of climate change, energy, health, finance, and culture (Table 3).

From these, 43 different characteristics were derived and grouped into seven principles based on their thematic commonality (Figure 2).

The following results and discussion reflect the scoring undertaken by the research team. Certain models performed well against certain Principles; the Multi-Sector and Integrated Care Systems Models each scored high across the principles centered on being Strategic (n = 7, = 7.86) while the Community-led Model scored high across Enabling (n = 7, = 8.14). Comparing specific characteristics, the Integrated Care Systems Model scored highest for Flexibility, Addressing conflict and Creating common ground. The Community-led Model out-scored all other models for being Value-added, Placed-based, Sharing, Inclusive and Altruistic. The Multi-Sector Model out-scored others in the characteristics of Balanced priorities, Authoritative, Skilled, Efficient, Adaptive, Fast-paced and Scalable. The Formal LA-led Model scored highest for Clarity of purpose while the Model ranked highest for Whole system view.

Each model demonstrates characteristics which, although not outscoring the other models, could provide useful insight. For example, the Free Trade model is based on the UK Government's post-Brexit flagships programmes for designating Freeports and Investment Zones. These are aimed at driving economic growth and sectoral innovation through a mix of locally applied policy, regulatory and fiscal interventions and levers (HM Government, 2022). The highest scoring characteristics suggest that parts of this model could be applied in complementary ways by local areas and local authorities in particular; firstly, as a blueprint in an area which prioritizes green economic growth, the model could be used to create new structures and relationships focussed on key outcomes, for example driving job creation within the low carbon sector, reconfiguring the education and training pathways for those looking to enter the sector, or stimulating innovation, a key objective of the Freeport programme on which this model is based. Secondly, the more local interventions and relaxations in the areas of tax and targeting support in areas of investment could be aligned with net zero delivery programmes. Thirdly, a local area which already hosts one of the designated economic zones could explore ways to utilize and extend, where appropriate and achievable, the zone's established governance structure and processes as a way of pivoting toward a local net zero economy.

The scoring process also helps to identify where a model performs poorly against the governance characteristics compared to the other models. The Free Trade Model, for example, under-performed in the characteristics of Trust, Inclusivity, Diversity and Personal (the Enabling principles) compared to the Community-led or Integrated Care Systems Models and scored lowest for Balanced priorities, Comprehensive and Diverse. The Informal LA-led Model underperformed with respect to Simplicity, Being opportunistic, Flexible, Agile and Empowering. The Community-led Model was seen to be weakest in terms of Clarity of purpose, Being Authoritative, Influential, Well-resourced and Skilled.

The assessment, therefore, builds a picture of strongest and weakest characteristics according to the model under consideration which, when taken across all eight models, provides a set of benchmarks and areas for potential improvement when the process is applied to real-world governance (Figure 3A, Table 4).

Figure 3. (A) Filtered radar plot showing the highest scoring characteristics by governance model. (B) Radar plots showing scoring for the three Area Partnerships compared the strongest scoring characteristics from the eight governance models. (C) Radar plots comparing County Area C vs. the Formal LA model with the yellow dots highlighting where the model outperforms.

The scoring process was applied to the three selected County-wide partnerships referred to in Section 3.6 with the strongest results from the eight models overlaid to identify opportunities for the local areas to learn from them (Figure 3B).

The results show that each County Partnership under-performed compared to the strongest characteristics demonstrated by the models. It also reveals the relative strength of County C over the other two areas. The assessment also shows levels of divergence between the local area plots and the strongest model scores. Taking the assessment for County C, local authorities in informal governance arrangements could learn most from the Community-led model with respect to the characteristics of adding value, being place-based, sharing and inclusivity.

With some qualifications, when compared to the Formal Local Authority-led model, informal Local Authority-led partnerships appear to perform less well in the characteristics of Purpose, Operating for the long-term, having Shared goals and demonstrating Effective oversight, being Well-skilled, Simple to understand, Well-embedded and Engaged (Figure 3C).

Many of these characteristics are likely to be more strongly demonstrated in a formal model since the arrangements between the local authorities in an area are established by statute. The rationale for joint working through a formal “shared services” provision established under the Local Government Act 1972 has often been financial, although the parties entering into an agreement may also be seeking to improve service delivery and internal effectiveness (Sandford, 2019). This type of arrangement is more common in England than the Devolved Administrations with 626 shared service arrangements recorded in 2018 (Local Government Association, 2023). Although there is variable evidence that sharing services in public administration delivers improvement (Local Government Association, 2016a), the factors for success can be identified and it can be argued that strong, long-term council-to-council arrangements in a locality are a pre-requisite to achieving effective net zero decision-making and delivery arrangements in a locality. Such success factors identified included a locally tailored approach, engagement with councilors and affected staff by the sharing arrangements, as well as having “…comfort with ambiguity, multiple relationships and flexibility in structure, skills and behaviors,” and developing enduring “partnering” rather than “partnership” (Local Government Association, 2016b, p. 4).

Beyond fostering the council-to-council relationship, a locality could benefit from observing the characteristics of Flexibility, Diversity and Creating common ground shown by the Integrated Care Systems model. This model is a recent incarnation of the arrangements for delivering health care in England introduced through the Health and Care Act 2022. The partnerships created under the ICS model bring together NHS organizations, local authorities and others to take collective responsibility for planning services, improving health and reducing inequalities across geographical areas through an Integrated Care Board and Partnership structure (The Kings Fund, 2022). They replaced a top-down approach to health care provision structured around Strategic Health Authorities where care provision was characterized by a compartmentalized approach. The model brings together strategic multi-stakeholder representation from the health and care organizations, local authorities and others determined locally. This can include representatives from social care, voluntary services, housing and education. However, there is wide flexibility about the Integrated Care Board/Partnerships are composed and operate to meet local needs.

The Community-led model brings values that tend to be less well developed in the three County area approaches in that the ambition is to foster truly Altruistic, Locally-centered and delivered solutions which engage directly with the individual citizen as a key actor with the vision of “putting local power in the hands of local people” (Low Carbon Hub, 2023). Both the ICS and Community-led models reveal strong characteristics that would help connect and anchor the Informal Local Authority-led approach observed in the three County areas to local stakeholders, whether institutional, communal or the individual citizen. This would not only help to legitimize the governance structure but potentially unlock untapped skills and capacity.

Maturity matrices are a common organizational performance assessment tool in the public sector allowing institutions to assess and benchmark their position in respect of a matter of issue to them or to their stakeholders (Good Governance Institute, 2022; NHS Employers, 2023). They can be used either as “a framework for reflective self-assessment, or as part of an independent review of governance” (Good Governance Institute, 2017, p. 1). Of note is the inclusion of benchmarking and positioning as part of organizational transformation and ongoing “value for money” analyses (Infrastructure and Projects Authority, 2020; HM Government, 2021). To date, little emphasis has been placed on councils to assess the fitness of area-wide governance as part of their climate emergency or net zero planning with little published academic research or public policy guidance. A key word search of academic literature identified 442 publications across all disciplines (EBSCO search TI “Maturity matrix” AND TI maturity matri* OR TI maturity grid* run 03 September 2023) with an absence of research literature considering the climate-related disciplines in public authorities.

Informal, local authority-led Climate Change or net zero partnerships with limited cross-sectoral representation is consistently the typical first step to catalyzing nascent support and creating a vehicle for coordinated action (Sustainability West Midlands, 2022; Energy Systems Catapult, 2023). Yet, informal partnerships are likely to face challenges when the participants start to build on initial progress due to them not meeting some of the principles of good governance; significant budgetary pressure in public administrations; the perceived reputational risk arising from devolving responsibility for delivery to others, delaying the creation of more formalized and better resourced structures; the variable approach and dynamics of representation with organizations “handpicked” rather than via open invitation for collaboration. These could lead to some societal sectors being under-represented or missed completely which could ferment a lack of trust in the governance arrangements amongst some stakeholders who may perceive themselves as being excluded.

The Sustainability West Midlands study undertook the first stage of identifying and outlining the types of local authority climate change partnerships are emerging in the East of England. The models and assessment process developed in our research builds on this by providing a way of assessing the maturity of a local area's existing governance. How far these partnerships are on the journey to becoming fully functional, cross-societal forces for net zero delivery at local level is a key consideration to local and wider regional progress. This requires not only a means of assessing whether the identified governance principles are part of the local governance arrangements but also that relationships between participants in the governance arrangement are appropriately formed, positive and long-lasting.

Appropriate governance structures are seen as essential “to create the buy-in and participation necessary to make a net zero energy system a reality” (Regen and Scottish and Southern Electricity Network, 2020, p. 20). Lack of appropriate governance arrangements constitutes “the most serious obstacle for their effective transformation into being smart” Ruhlandt (2018, p. 2). This manifests where the ecosystem of various agencies and stakeholders, including incumbent energy system actors, coupled with challenges around complexity of technology deployment, emissions accounting and responsibility for action, energy behaviors and the need for significant non-state investment at local level have seen some sectors and areas flatline on their decarbonization journey.

Their over-arching public wellbeing mission and core ethos of democratic accountability enshrined in law requires councils to follow good governance principles to always act in the public interest “not just being accountable according to certain formal criteria on reporting occasions,” (Ferry and Ahrens, 2017, p. 549). However, what is seen as good governance in a multi-stakeholder environment may depend on the perspective of the organization, institution or individual stakeholder and to what extent each participant is willing and able to cooperate around a shared purpose, be transparent and share decision making (Franke et al., 2022). The evidence from the literature review and observed practice suggests that local net zero governance structures are emerging although with variable consideration of the principles of good governance.

Much of the observed variability in the local structures that have been created to manage net zero delivery are a complex function of factors specific to the nature of local government and the characteristics of the localities (Kuzemko and Britton, 2020); the democratic process and local party-politics; the powers or duties with which the different tiers of government are vested; institutional processes, practices and conventions which frame local authority activity; the resources and capabilities to deliver; the nature of the local area that each local authority serves; and finally, and of particular note, the scale of public awareness and political activism toward or away from the net zero agenda. The reality of delivering net zero for smaller councils operating in two tier administrative areas is quite different to that of their metropolitan counterparts. They are more likely to lack the capacity, capability and unified political agency seen in the major cities (Beechener et al., 2021) and the resources and ability to create investment opportunities at the scale to be able to lower transaction costs (Webb et al., 2017). They also continue to wrestle with the political and administrative dynamics of two-tier administrative working and politics, described as a conundrum with “a multitude of decisions each of which could be made differently” (Webb, 2019 p. 297).

There is a clear need for coherent and collaborative planning and delivery mechanisms set within appropriate governance frameworks, based around place yet nationally aligned and able to operate dynamically to unlock net zero. This will require working arrangements, both within and between the tiers of public administration and with other societal stakeholders, functioning in ways that are not currently observed. The fact that there are councils striving together to develop area-based governance despite prolonged budgetary pressure, political differences and the absence of a legal framework within which to operate, suggests that other contextual drivers are at play (Kuzemko and Britton, 2020). Amongst these are a shift toward political localism, the ambition of local administrations to tackle climate change, the move toward decentralized energy systems and recognition that this entails a new relationship between councils and incumbent energy system actors.

The UK government shows no desire to define or advocate a unified model of local governance across England. The current Devolution process cannot be the single solution given its limited geographical coverage, focus on larger public administrations and the pace at which it takes to negotiate the deals. Furthermore, in the absence of a mandate, whether through specific net zero legislation or Devolution, multi-tier local public administrative areas will continue to struggle to develop their own approach to governance with some areas not getting beyond what should be viewed as the first structure of an informal local authority partnership limited by its inability to come together with wider society, constrained resources and aversion to disruptive solutions.

In the absence of, or even despite, national solutions being available, local initiatives will need to be fostered by public administrations working in collaborative arrangements with local society. The Dutch experience, for example, demonstrates that local programmes are likely to have more success when they have “a particularly supportive governance arrangement” (Warbroek et al., 2019, p. 10). The governance framework proposed in our 2021 research incorporates some of the key elements of the programmes advocated by central government. Best practice research is dominated by the large, metropolitan areas while the roles and relationships between smaller local authorities beyond these areas varies significantly. Every area is different but the principles and values that make for good governance are the same. Furthermore, as institutions which many consider as pivotal to the UK succeeding in its climate change obligations, local authorities need practical and cost-effective tools that they can apply beyond generic advice offered through competitively funded, time-bound support programmes This research establishes a way for the multiple layers of local government to work better with other stakeholders in their locality. The toolkit outlined in this paper provides councils systematic diagnostic and improvement processes to aid the development of local net zero governance. The assessment criteria and models derive insight from both academic literature and the real world, helping to make the theoretical tangible as well as demonstrating that solutions may exist across models which, because of their multi-sector origins, may help the public sector learn from others whilst accepting that some of the cited examples have yet to demonstrate their value and there may be trade-offs between the characteristics that they exhibit. The limitations of the proposed toolkit are acknowledged and can be addressed through the solutions raised in Section 6. The mixed model approach supported by a defined improvement process may help to engage stakeholders who are more likely to relate to the concepts and practice that they see in their own spheres of operation, giving them confidence that their councils are committed to well-designed and inclusive arrangements that suit the needs and strengths of local conditions.

The gap in support for local government to develop net zero governance arrangements is well recognized in both the research and publicly funded research programmes. The opportunity exists across local geographies where multiple tiers of public administration prevail to develop strong net zero governance collaborations initially progressively, starting with a core of the public authorities where clear roles and responsibilities can be defined and supported politically. The benefits of collaboration have been proven elsewhere where “public sector entities can reduce waste of assets, avoid unnecessary information gathering, and improve service delivery” (International Federation of Accountants Chartered Institute of Public, 2014, p. 17).

The value of the approach set out in this paper is in its flexibility and ease of application by practitioners in a sector lacking resources and developed exemplar models of governance. Such a toolkit, as part of wider programme of support, is considered crucial to improve the capability of local authority staff and politicians to build strong governance and enduring leadership between the tiers of local government and wider society.

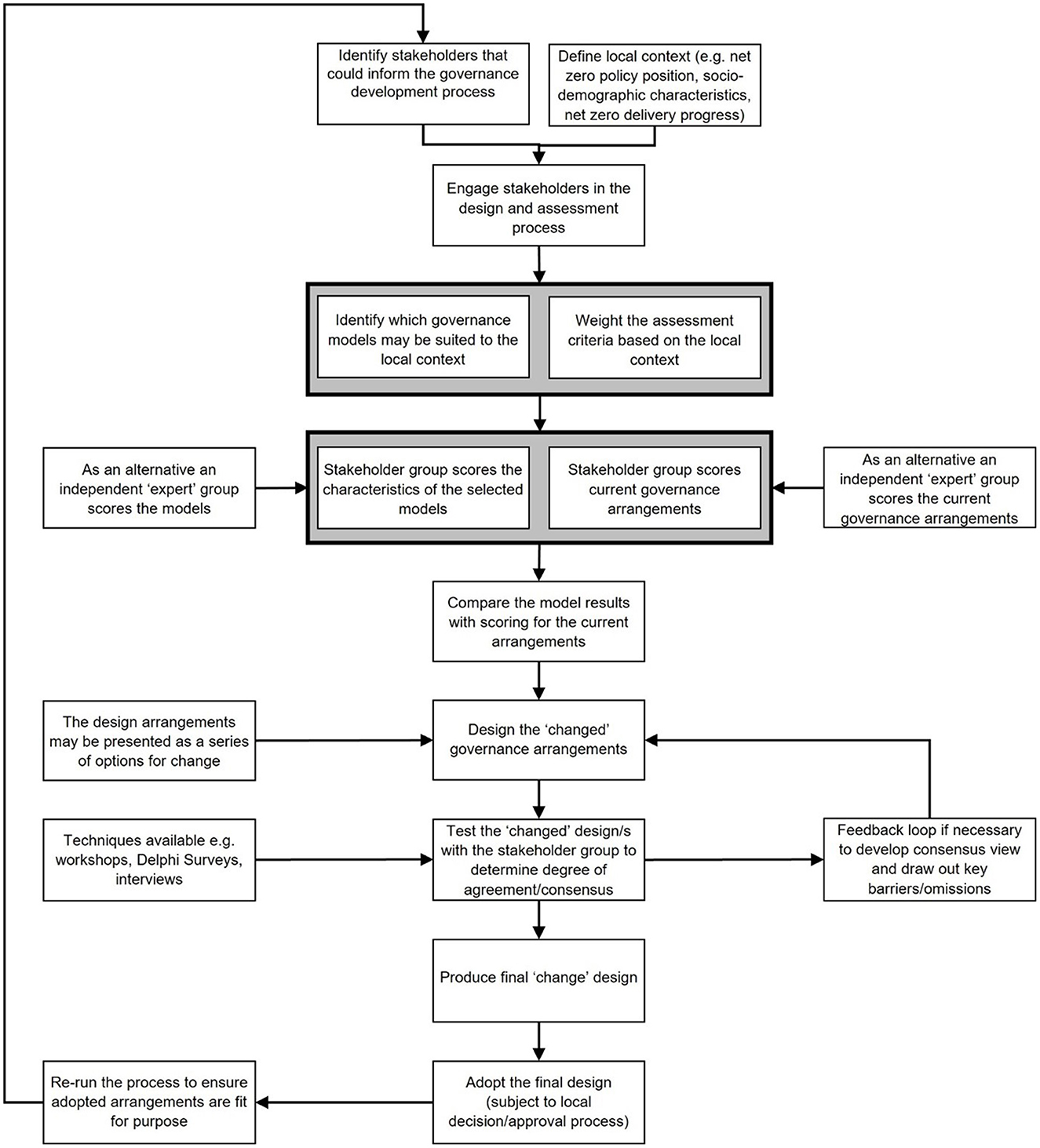

A process for developing locally grounded arrangements using the toolkit is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Process flow for improving local net zero governance. Gray boxes denote grouped activities using the tools developing in this research.

The biases introduced because of the use of a subjectively based scoring process could be addressed by applying two discrete controls. The first proposed control deals with potential bias introduced by participating individuals caused either through their lack of expertise in the subject or the dominance of one individual's opinion over that of another. The Delphi research technique is one way of quickly establishing solutions to complex problems by deriving a stable set of expert opinions using sequential questionnaires (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963) and reflection based on anonymous controlled feedback (Hasson et al., 2000). This approach has been recognized as an effective way of suppressing bias and herd thinking (Gronseth et al., 2012). The Delphi approach can be modified and applied to the scoring of the models prior to using the toolkit in a local context.

The second control aims to address the concern that each characteristic has equal weighting without regard to their relative importance. Each local area will demonstrate their own context, circumstances and stakeholders. Figure 4 incorporates both local definition and stakeholder identification at the commencement stage followed by a weighting assessment undertaken by the stakeholders selected to participate in the governance design process. In this way, the characteristics that are important to the local area can be given more focus in the evaluation and long-term improvement of current arrangements. Future applications of the toolkit, whether in research or real-world governance development, would therefore generate results that better reflect the conditions being evaluated.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

PG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. NB: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. PC: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. NC: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

PG wishes also to declare and acknowledge that he undertook paid consultancy work with the Energy Systems Catapult in support of the IUK Pathfinder project “Leicestershire CAN: Collaborate to Accelerate Net Zero.”

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alford, J., and Head, B. (2017). Wicked and less wicked problems: a typology and a contingency framework. Policy Soc. 36, 397–413. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2017.1361634

Beechener, G., Emre, E., Grantham, R., Griffith, P., Leaman, C., Massey, A., et al. (2021). City Investment Analysis Report. Report for the UK Cities Climate Investment Commission. Available online at: https://1hir952z6ozmkc7ej3xlcfsc-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/UKCCIC_Final_Report.pdf?utm_campaign=ukccic-andutm_source=websiteandutm_medium=download-final-report (accessed January 16, 2022).

Berthod, O., Blanchet, T., Busch, H., Kunze, C., Nolden, C., and Wenderlich, M. (2022). The rise and fall of energy democracy: 5 cases of collaborative governance in energy systems. Environ. Manage. 71, 551–564. doi: 10.1007/s00267-022-01687-8

Biermann, F., Chan, S., Mert, A., and Pattberg, P. (2007). “Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: does the promise hold?” in Partnerships, Governance and Sustainable Development. Reflections on Theory and Practice, eds. P. Glasbergen, F. Biermann, and A. Mol (New York, NY: Cheltenham).

Billington, P., Smith, C. A., and Ball, M. (2020). Rate of Investment in Local Energy Projects. Summary Report July 2020. Available online at: https://www.uk100.org/publications/accelerating-rate-investment-local-energy-projects-summary-report (accessed July 11, 2020).

Bridge, G., and Perreault, T. (2009). “Environmental governance,” A Companion to Environmental Geography, eds. N. Castree, D. Demeritt, D. Diana, R. Bruce (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons).

Bristol City Council (2022). Bristol's City Leap. Available online at: https://www.energyservicebristol.co.uk/cityleap/ (accessed May 5, 2022).

Bulkeley, H., and Kern, K. (2006). Local government and the governing of climate change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stu. 43, 2237–2259. doi: 10.1080/00420980600936491

Charles, A., Leo Ewbank, L., Naylor, C., Walsh, N., and Murray, R. (2021). Developing Place-Based Partnerships. The Foundation of Effective Integrated Care Systems. The King's Fund. Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-04/developing-place-based-partnerships.pdf (accessed March 28, 2023).

Charles, A., Lillie Wenzel, L., Kershaw, M., Chris Ham, C., and Walsh, N. (2018). A Year of Integrated Care Systems. Reviewing the Journey so Far. The King's Fund. Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Year-of-integrated-care-systems-reviewing-journey-so-far-full-report.pdf (accessed September 9, 2018).

Christie, I., and Russell, E. (2023). On Multi-Level Climate Governance in an Urban/Rural County: A Case Study of Survey. London: A Report by the Place-Based Climate Action Network (PCAN), UK.

Climate Change Committee (2022). Progress in Reducing Emissions 2022 Report to Parliament. Available online at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2022-progress-report-to-parliament (accessed June 22, 2022).

Climate Emergency UK (2023). Draft Methodology. Council Climate Scorecards. Available online at: https://councilclimatescorecards.uk/methodology/#section-question-criteria (accessed May 14, 2024).

Collins, A., and Walker, A. (2023). UK Parliament Post POST Note 70. Local Area Energy Planning: Achieving Net Zero Locally. doi: 10.58248/PN703

County Councils Network (2022). Nine Counties to Begin Negotiations on Devolution Deals as Part of Levelling-Up White Paper. Available online at: https://www.countycouncilsnetwork.org.uk/nine-county-devolution-deals-announced-as-part-of-levelling-up-white-paper/ (accessed September 17, 2023).

Dalkey, N., and Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage. Sci. 9, 458–467. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458

Davis, M. (2021). Community Municipal Investments: Accelerating the Potential of Local Net Zero Strategies. England: University of Leeds.

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Ministry of Housing Communities, and Local Government. (2023). Guidance. Local Government Structure and Elections. Information on the Different Types of Council and Their Electoral Arrangements. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/local-government-structure-and-elections#county-councils (accessed April 28, 2023).

Department of Digital Culture, Media, and Sport. (2017). Guidance. Stage 5: Options Appraisal. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/libraries-alternative-delivery-models-toolkit/stage-5-options-appraisal#overview (accessed May 14, 2024).

Energy Systems Catapult (2023). Theme 1. Developing and Delivering Your Strategy: Decarbonisation Strategy Documentation Checklist. Available online at: https://es.catapult.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Theme-1-guide-Developing-and-delivering-your-strategy.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Evans, L. M. (2020). Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget. An Independent Report for the Climate Change Committee. Available online at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget (accessed May 14, 2024).

Ferry, L., and Ahrens, T. (2017). Using management control to understand public sector corporate governance changes: localism, public interest, and enabling control in an English local authority. J. Account. Org. Change 13, 548–567. doi: 10.1108/JAOC-12-2016-0092

Financial Reporting Council (2018). Corporate Governance Code. Available online at: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/88bd8c45-50ea-4841-95b0-d2f4f48069a2/2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-FINAL.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Franke, V. C., Wolterstorff, E., and Wehlan, C. W. (2022). The three conditions: solving complex problems through self-governing agreements. Int. Neg. 11, 264–291. doi: 10.1163/15718069-bja10034

Good Governance Institute (2017). Maturity Matrix Institute for Governing Bodies in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.good-governance.org.uk/assets/uploads/publication-documents/Matrices/GGI-Maturity-Matrix-for-Governing-Bodies-in-Higher-Education-2017.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Good Governance Institute (2022). Third Sector Maturity Matrix. Available online at: https://www.good-governance.org.uk/assets/uploads/publication-documents/Third-sector-Maturity-Matrix-2022.pdf (accessed September 22, 2022).

Greater Manchester Combined Authority (2024). Combined Authority Declares Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/news/combined-authority-declares-climate-emergency/ (accessed April 8, 2024).

Gronseth, G., Getchius, T., and Hagen, E. (2012). e-Consensus: An Efficient Method for Attaining Consensus Using a Modified Delphi Process. Dusseldorf: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House.

Gudde, P., Oakes, J., Cochrane, P., Caldwell, N., and Bury, N. (2021). The role of UK local government in delivering on net zero carbon commitments: You've declared a Climate Emergency, so what's the plan? Energ. Policy 154:112245. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112245

Hamman, P. (2005). From “multilevel governance” to “social transactions” in the European context. Swiss J. Sociol. 31, 523–545.

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., and McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 32, 1008–1015. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

Health Quality Improvement Partnership (2021). Good Governance Handbook. Available online at: https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/FINAL-Good-Governance-Handbook-Jan-21-V9.pdf (accessed January 21, 2021).

Hillman, K., Nilsson, M., Rickne, A., and Magnusson, T. (2011). Fostering sustainable technologies – a framework for analysing the governance of innovation systems. Sci. Pub. Policy 38, 403–415. doi: 10.3152/030234211X12960315267499

HM Government (2021). Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener. Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 14 of the Climate Change Act 2008. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1033990/net-zero-strategy-beis.pdf (accessed January 8, 2022).

HM Government (2022). English Freeports Setup Phase and Delivery. Model Guidance. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1074123/English_Freeports_Guidance_-_Setup_Phase_and_Delivery_Model.pdf (accessed July 24, 2022).

HM Government/West Midlands Combined Authority (2023). Combined Authority Trailblazer Deeper Devolution Deal. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1143001/Greater_Manchester_Combined_Authority_Trailblazer_deeper_devolution_deal.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Hoddinott, S., Fright, M., and Pope, T. (2022). ‘Austerity' in Public Services. Lessons From the 2010s. Institute for Government. Available online at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/austerity-public-services.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Howlett, M., Rayner, J., and Tollefson, C. (2009). From government to governance in forest planning? Lessons from the case of the British Columbia Great Bear Rainforest initiative. Forest Policy Econ. 11, 383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2009.01.003

Infrastructure and Projects Authority (2020). Guidance - Benchmarking Capability Tool. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benchmarking-capability-tool (accessed May 14, 2024).

Innovate UK (2022). Accelerating Net Zero Delivery. Unlocking the Benefits of Climate Action in UK City-Regions. https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IUK-090322-AcceleratingNetZeroDelivery-UnlockingBenefitsClimateActionUKCityRegions.pdf (acccessed March 21, 2022).

Institute for Government (2023). English Devolution. What is the History of English Devolution? How Much of England Has Devolution? Which Powers are Devolved? Available onlline at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/english-devolution/ (accessed September 17, 2023).

International Federation of Accountants and Chartered Institute of Public Finance, and Accounting. (2014). International Framework Good Governance in the Public Sector, New York and London. Available onlline at: http://www.cipfa.org/policy-and-guidance/standards/international-framework-good-governance-in-the-public-sector (accessed May 14, 2024).

Kuzemko, C., and Britton, J. (2020). Policy, politics and materiality across scales: a framework for understanding local government sustainable energy capacity applied in England. Energ. Res. Soc. Sci. 62:101367. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101367

Lange, P., Driessen, P., Sauer, A., Bornemann, B., and Burger, P. (2013). Governing towards sustainability—conceptualizing modes of governance. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 15, 403–425. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2013.769414

Lloyd, T., Beech, J., Wolters, A., and Tallack, C. (2023). Realising the Potential of Community-Based Multidisciplinary Teams. Insights From Evidence. February 2023. London: The Health Foundation Improvement Analytics Unit.

Local Government Association (2016a). Stronger Together - Shared Management in Local Government. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/stronger-together-shared-01e.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Local Government Association (2016b). Investigating and Improving the HR and OD Capability in Shared Councils. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/investigating-and-improvi-80e.pdf

Local Government Association (2023). Shared Services Map. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/efficiency-and-productivity/shared-services/shared-services-map (accessed September 2, 2023).

Low Carbon Hub (2023). Welcome to the Low Carbon Hub. Creating Energy We Can All Feel Good About. Available online at: https://www.lowcarbonhub.org/ (accessed September 17, 2023).

Lowndes, V., and Pratchett, L. (2012). Local governance under the coalition government: austerity, localism and the ‘big society. Local Govern. Stu. 38, 21–40. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2011.642949

Lucas, K., Ross, A., and Fuller, S. (2003). What's in a Name? Local Agenda 21, Community Planning and Neighbourhood Renewal. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Available online at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/local-agenda-21-community-planning-and-neighbourhood-renewal#downloads (accessed May 14, 2024).

Lynn, L. E., Heinrich, C. J., and Hill, C. J. (2000). Studying governance and public management: challenges and prospects. J-PART 10, 233–261. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024269

Mulgan, G. (2020). The Case for Mesh Governance (or How Government Can Escape the Old Organograms). Available online at: https://www.geoffmulgan.com/post/mesh-governance-joining-the-dots (accessed December 12, 2023).

mySociety (2024). CAPE. Informing Local Action on Climate Change. Available online at: https://cape.mysociety.org/councils/ (accessed April 8, 2024).

NHS Employers (2023). The Role of Governance in Advanced Practice. Learn about the Governance Maturity Matrix and How it can Help NHS Organisations Assess and Improve Advanced Practice Standards. Available online at: https://www.nhsemployers.org/articles/role-governance-advanced-practice [Accessed 17 September 2023].

Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (2023). Consultation - Future of Local Energy Institutions and Governance. Available online at: https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications/consultation-future-local-energy-institutions-and-governance?utm_medium=emailandutm_source=dotMailerandutm_campaign=Daily-Alert_01-03-2023andutm_content=Consultation%3a+Future+of+local+energy+institutions+and+governanceanddm_i=1QCB,87YT3,CW1KES,XQDOA,1 (accessed May 14, 2024).

Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environ. Change 20, 550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004

Pierre, J. (2000). Debating Governance: Authority, Steering, and Democracy. Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198295143.001.0001

Regen and Scottish and Southern Electricity Network (2020). Local Leadership to Transform our Energy System. Available online at: https://www.regen.co.uk/publications/local-energy-leadership-to-transform-our-energy-system/ (accessed March 17, 2021).

Rittel, H. W. J., and Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci., 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

Ruhlandt, R. (2018). The governance of smart cities: a systematic literature review. Cities 81, 1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.014

Sandford, M. (2019). Briefing Paper Number 05950. Local Government: Alternative Models of Service Delivery. House of Commons Library. Available online at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN05950/SN05950.pdf (accessed September 9, 2019).

Sibeon, R. (2000). Governance and the policy process in contemporary Europe. Public Manage. 2, 289–309. doi: 10.1080/14719030000000019

Skidmore, C. (2022). Mission Zero: Independent Review of Net Zero. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1128689/mission-zero-independent-review.pdf (accessed May 14, 2024).

Sustainability West Midlands (2022). Regional Baseline Analysis: Climate Change Partnerships. Report Prepared for East of England Regional Climate Change Forum. Available online at: https://www.eelga.gov.uk/app/uploads/2022/11/EELGA-RCCF-Baseline-Final-Report-12.08.2022.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Szulecki, K., Pattberg, P., and Biermann, F. (2011). Explaining variation in the effectiveness of transnational energy partnerships. Governance 24, 713–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01544.x

Termeer, C. J. A. M., Dewulf, A., Breeman, G. E., and Stiller, S. J. (2015). Governance capabilities for dealing wisely with wicked problems. Admin. Soc. 47, 680–710. doi: 10.1177/0095399712469195

The Kings Fund (2022). Integrated Care Systems Explained: Making Sense of Systems, Places and Neighbourhoods. Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained (accessed September 17, 2023).

Thompson, G. J., Frances, R. L., and Mitchell, J., (eds.). (1991). Markets, Hierarchies and Networks: The Co-ordination of Social Life. London: Sage.

Tingey, M., and Webb, J. (2020). Governance institutions and prospects for local energy innovation: laggards and leaders among UK local authorities. Energ. Policy 138:111211. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111211

UK Climate Assembly (2020). The Path to Net Zero. Climate Assembly UK Executive Summary. Available online at: https://www.climateassembly.uk/report/read/index.html (accessed May 14, 2024).

UK Government (2023). Greater Manchester and West Midlands: Trailblazer Devolution Deals. Research Briefing. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greater-manchester-combined-authority-trailblazer-deeper-devolution-deal (accessed November 27, 2023).

United Nations (1992). United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. Agenda 21. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/Agenda21.pdf (accessed June 14, 1992).

Warbroek, B., Hoppe, T., Bressers, H., and Coenen, F. (2019). Testing the social, organizational, and governance factors for success in local low carbon energy initiatives. Energ. Res. Soc. Sci. 58:101269. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101269

Webb, J. (2019). New lamps for old: financialised governance of cities and clean energy. J. Cult. Econ. 12, 286–298. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2019.1613253

Webb, J., Tingey, M., and Hawkey, D. (2017). What We Know about Local Authority Engagement in UK Energy Systems: Ambitions, Activities, Business Structures and Ways Forward. London: Energy Research Centre and Loughborough, Energy Technologies Institute.

West Midlands Combined Authority (2021). The West Midlands Net Zero Pathfinder: Proposals to HM Government to Accelerate the Net Zero Transition and a Green Industrial Revolution. Available online at: https://www.wmca.org.uk/media/4667/net-zero-proposal-v3.pdfhttps://www.wmca.org.uk/media/4667/net-zero-proposal-v3.pdf (accessed April 8, 2024).

Keywords: local authorities, net zero, governance models, evaluation, toolkit approach

Citation: Gudde P, Bury N, Cochrane P and Caldwell N (2024) Developing a toolkit to help smaller local authorities establish strong net zero governance in the UK. Front. Sustain. Energy Policy 3:1390570. doi: 10.3389/fsuep.2024.1390570

Received: 23 February 2024; Accepted: 07 May 2024;

Published: 23 May 2024.

Edited by:

Eric O'Shaughnessy, Berkeley Lab (DOE), United StatesReviewed by:

Suyash Jolly, Nordland Research Institute, NorwayCopyright © 2024 Gudde, Bury, Cochrane and Caldwell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Gudde, cC5ndWRkZUB1b3MuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.