- 1Faculty of Biological Sciences, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom

- 2School of Medicine, Keele University, Keele, United Kingdom

- 3School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Clinical Exercise and Rehabilitation Research Centre, School of Sport and Exercise Science, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

Background: Despite physical activity (PA) providing specific health benefits during pregnancy and the postpartum period, many women report decreased PA during this time. Provision of PA advice has been found to be lacking amongst midwives due to a range of barriers. This study aimed to evaluate United Kingdom's midwives' current role and knowledge regarding the provision of PA advice to pregnant and postpartum women and identify the barriers and potential solutions.

Methods: Ten UK midwives (mean work experience ± SD: 15.5 years ± 10.2) participated in semi-structured interviews between May and July 2023. Data were analysed using a deductive thematic approach following Braun and Clarke's six steps. Demographic data were collected by Microsoft Forms then summarised using Microsoft Excel.

Results: Six themes with 25 subthemes were identified as barriers and solutions in delivering PA advice. The role of midwives in providing PA advice during pregnancy; the role of midwives in providing PA advice postpartum; intrinsic barriers that limit PA advice provision (confidence, safety concerns, knowledge, and midwife's personal body habitus); extrinsic barriers that limit PA advice provision (lack of time, education, PA not a priority in care); solutions to allow midwives to promote PA (including formal PA education, and dissemination of resources); and optimising delivery of PA advice (personalized approach, interprofessional collaboration, and linking to mental health benefits).

Discussion: Midwives consider themselves ideally placed to provide PA advice to pregnant women, with many aware of the benefits PA provides. Despite this, there is a lack of PA advice provision and knowledge of PA guidelines. Postpartum PA advice appeared to be considered outside the remit of midwives, due to limited contact. Further research is needed to determine the current level of PA advice provision for pregnant and postpartum women and explore the role of other healthcare professionals involved in maternity care.

1 Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is well known to improve an individual's physical and mental wellbeing (1, 2). However, PA in both the antenatal and postpartum period provides specific benefits to women. In pregnancy, this includes reduced risk of gestational diabetes (GDM) and excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) (3). PA may also reduce the risk of needing a caesarean section, particularly in obese women (4). Following birth, PA has been found to reduce the risk of postpartum depression, prevalent in 15%–20% of women; and reduce postpartum weight retention, a predictor of obesity in later life (3, 5–8).

Since 2017, the United Kingdom (UK) Chief Medical Officer (CMO) has recommended pregnant women (with no contraindications to PA) aim for at least 150 min of moderate intensity activity every week to reap health benefits such as weight control; prevention of gestational hypertension and GDM; and improved sleep and mood (9). The guidelines also recommend performing muscle strengthening activities twice weekly, as well as safety messages such as “don't bump the bump”. Guidance was updated in 2019 to include postpartum women for the first time, defined as birth to 12 months post-partum (10). Postpartum women are also recommended to aim for at least 150 min of moderate intensity activity every week for benefits including improved mental wellbeing, weight control, and improved sleep. The postpartum guidelines also recommend pelvic floor exercises, though a gradual approach to all activities is advised. For both groups, the message “no evidence of harm” is promoted. The messages in the CMO guidelines for both pregnant and postpartum women are echoed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the World Health Organisation (11, 12). To ease dissemination, the CMO PA guidelines are illustrated in infographic form to be used by health care professionals (HCPs), which detail the benefits of PA and provide the key recommendations (10). Despite the benefits of PA and reassurances regarding safety, many pregnant and postpartum women do not meet the PA recommendations (13–15). Barriers to PA faced by both groups include fatigue and lack of time, confidence, and motivation (7, 16, 17).

Importantly, pregnancy is considered a teachable moment and a point where women have greater motivation to improve health behaviours such as PA and diet (18, 19). Midwives are encouraged to discuss PA at the first antenatal appointment and later on in the pregnancy if appropriate (20). During pregnancy in the UK a woman will receive seven to ten antenatal appointments with a midwife (20). This high level of contact places midwives in an opportune position to promote healthy lifestyle changes. Even brief consultations have been found to positively impact behaviour change (21, 22). Midwives therefore could play a significant role in PA promotion during pregnancy. Despite midwives being ideally placed to deliver PA advice to pregnant women, it appears this is not being provided efficiently and consistently (23). Many women have reported a lack of advice and support, with another more recent qualitative evidence synthesis of UK practice recommendations reporting that women find advice relating to weight management inconsistent and confusing (24). The postpartum period is also considered an opportunity to facilitate health behaviour change (25), but the role of a midwife is less clear, as a midwife will only typically see a woman up to ten days post-partum (26).

Many studies, both before and after the 2019 update of the CMO PA guidelines, have examined the reasons behind the lack of PA advice given to pregnant women in the UK. HCPs reported barriers include time constraints; lack of training, knowledge, confidence, and resources; and a fear of offending patients (27–30). A lack of midwife awareness of the CMO guidelines for both pregnant and postpartum women has also been identified (31). To the authors' knowledge, there has been limited research examining midwife provision of PA advice to postpartum women specifically in the UK, perhaps reflecting the delayed inclusion of postpartum women to UK PA guidelines. However, data collected prior to the 2019 CMO update identified a lack of time, training, and priority given to PA as barriers midwives face when providing postpartum PA advice (32).

It is important to hold dialogue with midwives specifically regarding the barriers they experience when providing PA advice to allow shaping of realistic solutions to support their efforts to promote PA. This study aimed to evaluate UK midwives' current role and knowledge regarding the provision of PA advice to pregnant and postpartum women, in particular the role midwives play in providing PA advice in the postpartum period due to the lack of current research. It also aimed to understand the challenges and barriers midwives face when providing PA advice and then find possible solutions to allow effective promotion of PA for both groups.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

A qualitative research study was conducted examining midwives' knowledge and delivery of PA advice for pregnant and postpartum women. This study forms part of a larger project examining knowledge and promotion of PA guidelines amongst other HCPs (33, 34). Ethical approval was given by the Faculty of Biological Sciences at the University of Leeds (27 July 2020/BIOSCI 19-039).

2.2 Participants

Ten UK based midwives were recruited and interviewed, a similar sample size to other related studies employing the semi-structured interview approach (28). Sample size was driven by data saturation, the point where further interviews provided no new themes (35). The inclusion criteria were midwives who trained and currently practice within the UK, able to communicate in English.

Participants were recruited by purposive volunteer sampling, primarily shared through midwife contacts and channels. The Royal College of Midwives were also contacted. Recruitment took place from April to July 2023. A brief written overview of the project was shared through these channels, alongside a Microsoft Form, where prospective participants registered interest to be contacted. The participation form collected email addresses and forms were screened to check that participants matched the inclusion criteria. After registering interest, eligible participants were emailed a Participant Information Form to keep in their personal records, and a Participant Consent Form to be signed and returned prior to demographic data collection and interview.

2.3 Data collection: participant characteristics

After written consent was obtained, participants were invited to be interviewed and to also complete a demographic data form. Demographic information was collected via Microsoft Forms, then automatically exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The data were then anonymised by assigning participant unique identification numbers (chronologically by interview order). The participants were asked their gender (male, female, other), location of work (by UK region), midwifery work experience (years), current band, previous healthcare roles, and current setting of work (primary care, secondary care, combination, or other). Participants also selected one of three statements to describe their current personal PA levels: “Currently meeting the CMO PA guidelines of 150 min moderate/75 min vigorous weekly PA or combination of both”; “Currently doing some PA: >30 min moderate PA per week, but not meeting CMO PA guidelines of 150 min moderate/75 min vigorous weekly PA or combination of both”; and “Currently doing less than 30 min moderate PA per week”. Participants were not asked about strength training. The demographic data form also allowed participants to input suitable interview time, which reduced email traffic.

2.4 Data collection: midwife provision of PA advice

Data were collected by semi-structured interview between May and July 2023. The semi-structured approach provided a flexible approach to allow collection of rich and detailed data reflecting the midwives' individual experiences (36). The interview guide was adapted from the study by Vishnubala et al. (33) which examined doctors' attitudes towards PA. Interviews were conducted online through Zoom and Microsoft Teams depending on participant preference, to increase accessibility and convenience, and allow automatic transcription.

The interviews began with an outline of the ethical information, including participant rights right to withdraw, and anonymity. The interviews then followed four stages: demographics, PA education, PA resources and interventions, and the impact of COVID-19 on providing PA guidance. Data from the COVID-19 section was not included in analysis as it was not relevant to the research questions. The interview guide can be found in Supplementary Material.

With consent, the interviews were audio-recorded and automatically transcribed verbatim the same day by MM using recording and transcription tools on the chosen platform. The audio recordings and transcripts were anonymised and stored securely on the University of Leeds OneDrive. Prior to analysis, each transcript was checked for accurate transcription by listening to the audio recordings and any errors were corrected.

2.5 Data analysis

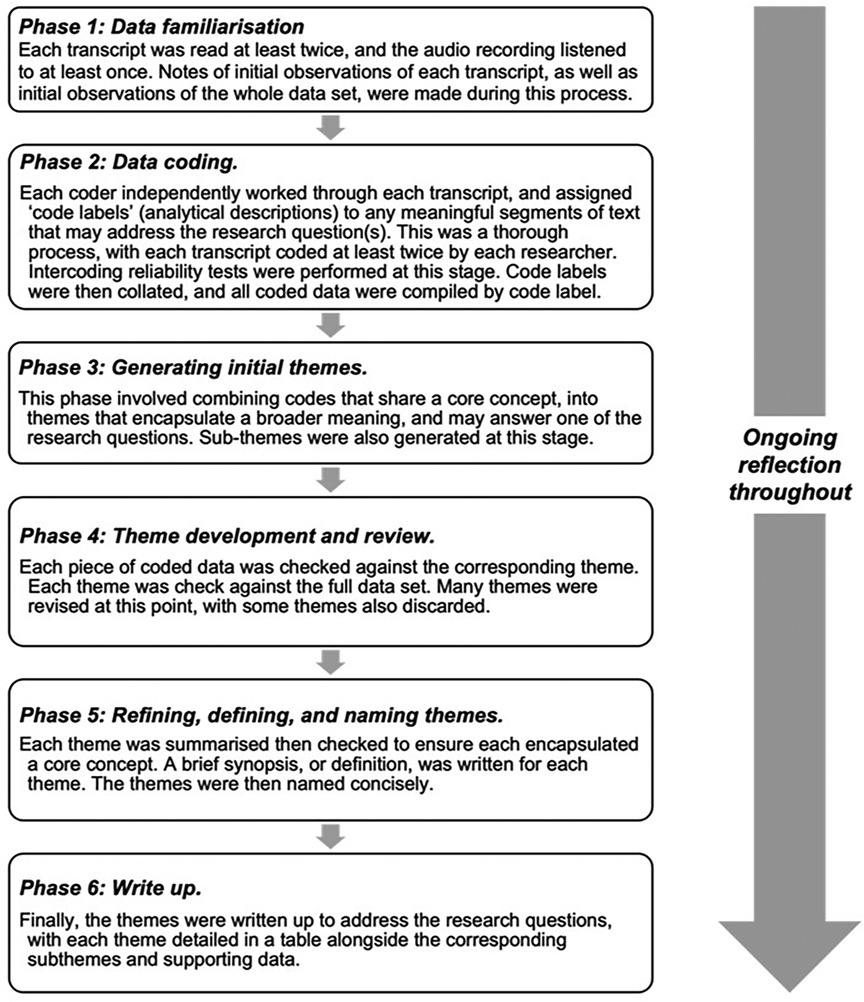

Microsoft Excel was used to summarise demographic data. For the interview data, a six-phase deductive thematic analysis was conducted according to Braun and Clarke (35), with a flexible approach to allow critical reflection as illustrated in Figure 1. To enhance understanding, the coding process was undertaken by two researchers independently, one of whom had previous experience in thematic analysis. After each researcher coded all the transcripts, inter-coding reliability was assessed. This was calculated by dividing the number of agreed codes by the total number of codes, to allow a quick assessment, and revealed a 65% similarity (37). However, on further discussion and review of the codes, this resulted in a consensus of 75%. This is above the 70% threshold that is deemed acceptable (38). While intercoder reliability, and its appropriateness within qualitative data analysis is in question (37), the second coder allowed for richer data interpretation with greater breadth and depth of codes, that may not have been achieved with a single coder (39). A total of 203 codes were identified by the end of the coding process. During the theme generation phase, six themes and 35 subthemes were generated. This fell to six themes and 25 subthemes after themes were developed and reviewed. A reflective diary was kept throughout the process to bring awareness to the effects of the researcher's personal attitudes.

Figure 1. Thematic analysis methodology according to Braun and Clarke’s six steps (35).

3 Results

3.1 Demographic data

Fifteen midwives completed the Initial Participation Form. Of those, nine returned the consent form and were subsequently interviewed. One additional participant was recruited directly by word of mouth, without completing the initial participation form. In total ten midwives were therefore interviewed. Sample size was driven by data saturation, the point where further interviews provided no new themes, which occurred after the ninth interview (35). Interviews varied in length between 29 and 60 min, with a mean time of 41 min.

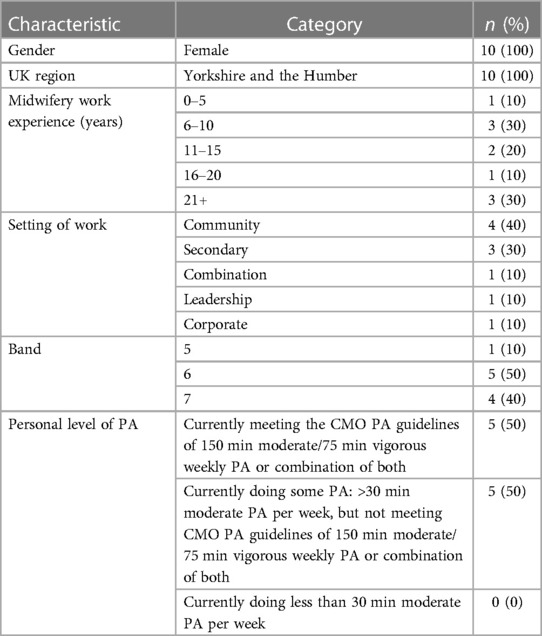

Table 1 summarises participant characteristics. All participants were female midwives working within the Yorkshire and the Humber region. Midwifery work experience ranged from 1 to 35 years (median ± IQR: 14.5 years ± 16.25). Half of all midwives were band 6, and the most common setting of work was community midwifery. In terms of personal levels of PA, there was an equal split between midwives who met the CMO PA guidelines, and midwives who were doing some PA but not meeting guidelines. No midwives were classed as inactive (performing less than 30 min of moderate PA per week).

3.2 Themes and subthemes

Six themes were identified following thematic analysis: the role of midwives in providing PA advice antenatally; the role of midwives in providing postpartum PA advice; intrinsic barriers that limit provision of PA advice; extrinsic barriers that limit provision of PA advice; solutions to allow midwives to promote PA; and optimising delivery of PA advice. Twenty-five subthemes were also identified and listed next to their respective theme. Sub-themes were discussed with CN and confirmed with both CN and KM.

3.2.1 Theme 1: the role of midwives in providing PA advice antenatally

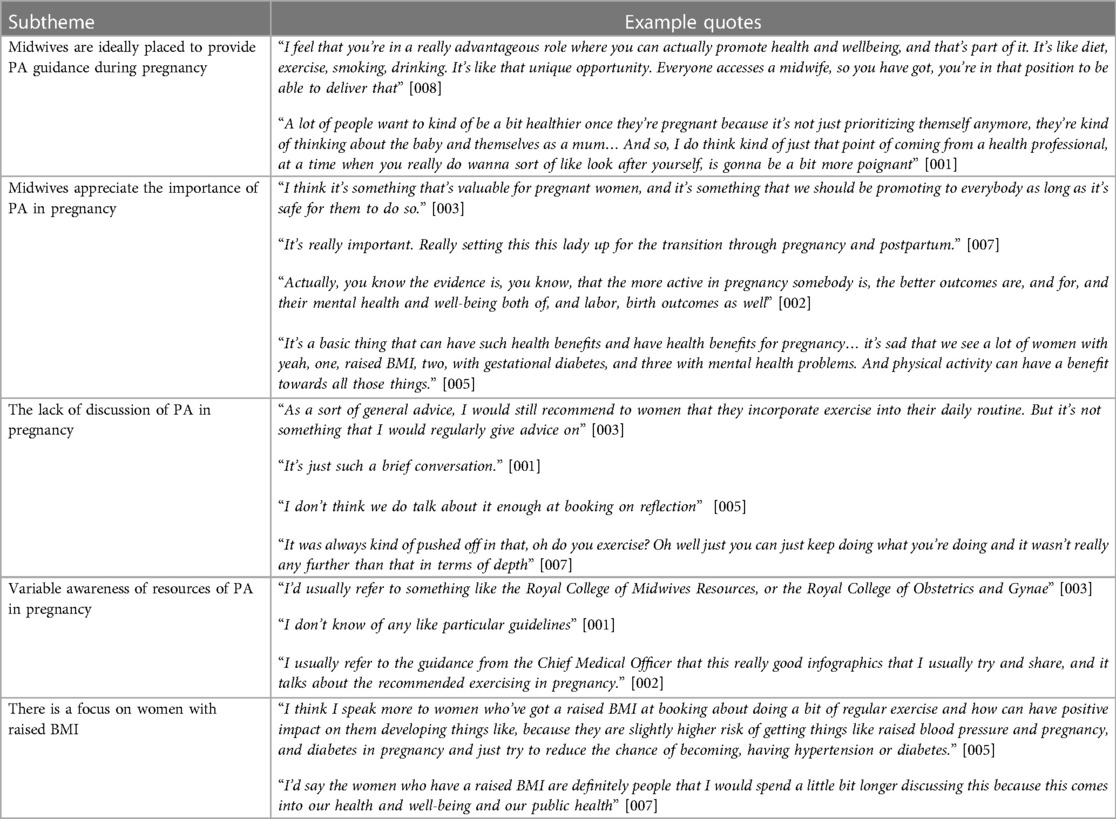

Table 2 summarises the role of midwives in providing PA advice antenatally, including five subthemes. Square brackets following each quote indicate the participant's unique identifying number. Many midwives expressed that pregnancy was an opportune time to share PA advice with an appreciation of its importance and the benefits. However, many midwives noted an under-provision of PA advice during pregnancy, with discussions lacking in regularity, length and depth. There was a variable awareness of resources regarding PA in pregnancy. Few midwives were aware of the CMO PA guideline infographics, and some midwives were not aware of any resources related to PA in pregnancy. There was also a focus on providing PA advice to women with raised BMIs (Body Mass Index).

3.2.2 Theme 2: the role of midwives in providing postpartum PA advice

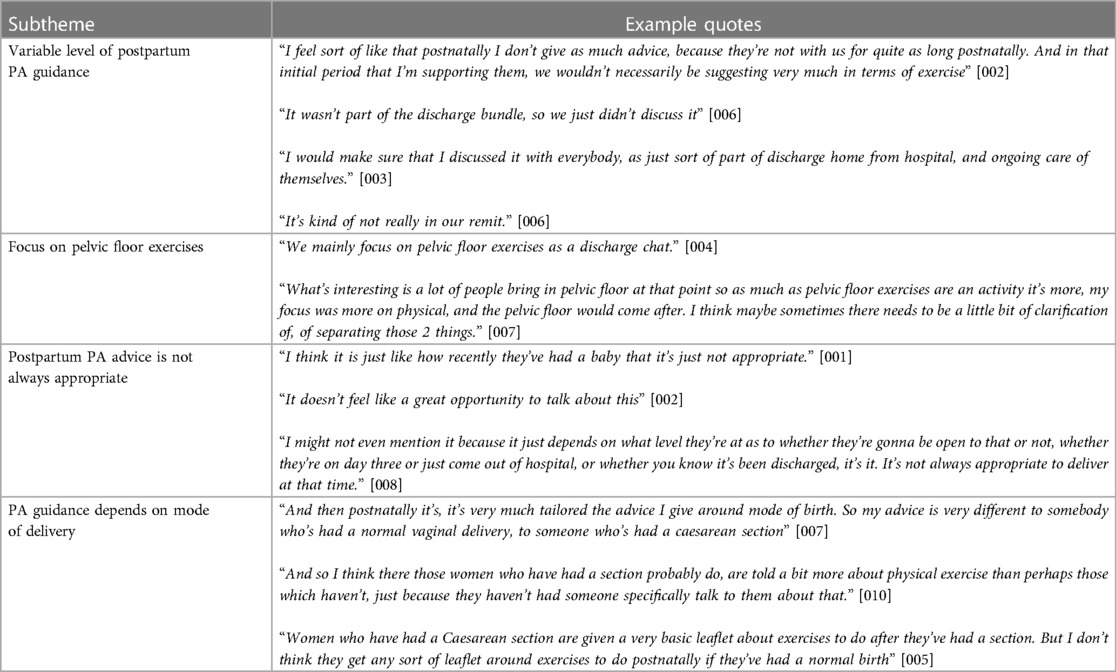

The role of midwives in providing postpartum PA advice was also explored (Table 3), and four subthemes were found. There was a variable level of postpartum PA guidance, and many midwives noted that postpartum PA discussions focused mainly, or occasionally solely, on pelvic floor exercises. Postpartum PA advice was often felt not to be “appropriate”, due to the recentness of birth. PA discussions also highly depended on a woman's mode of delivery. Many reported that post Caesarean section, women receive more information and physiotherapy support, support not provided to women post vaginal delivery.

3.2.3 Theme 3: intrinsic barriers that limit provision of PA advice

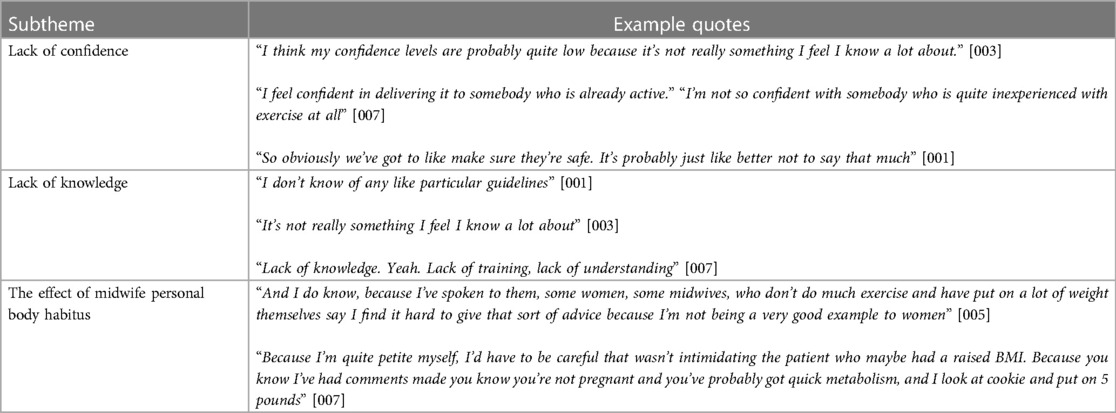

There were three subthemes regarding intrinsic barriers limiting provision of PA advice (Table 4). Confidence levels varied between midwives, but also depended on the current level of PA of the woman. Many midwives also cited safety concerns as limiting their confidence to provide PA advice, particularly encouraging the adoption of new PA. Lack of knowledge and understanding of PA guidelines were common themes throughout, with low awareness of resources such as “Moving Medicine”. A midwife's personal body habitus was also discussed as a potential barrier, with both midwives of higher and lower BMIs finding it impacted provision or reception of PA advice.

3.2.4 Theme 4: extrinsic barriers that limit provision of PA advice

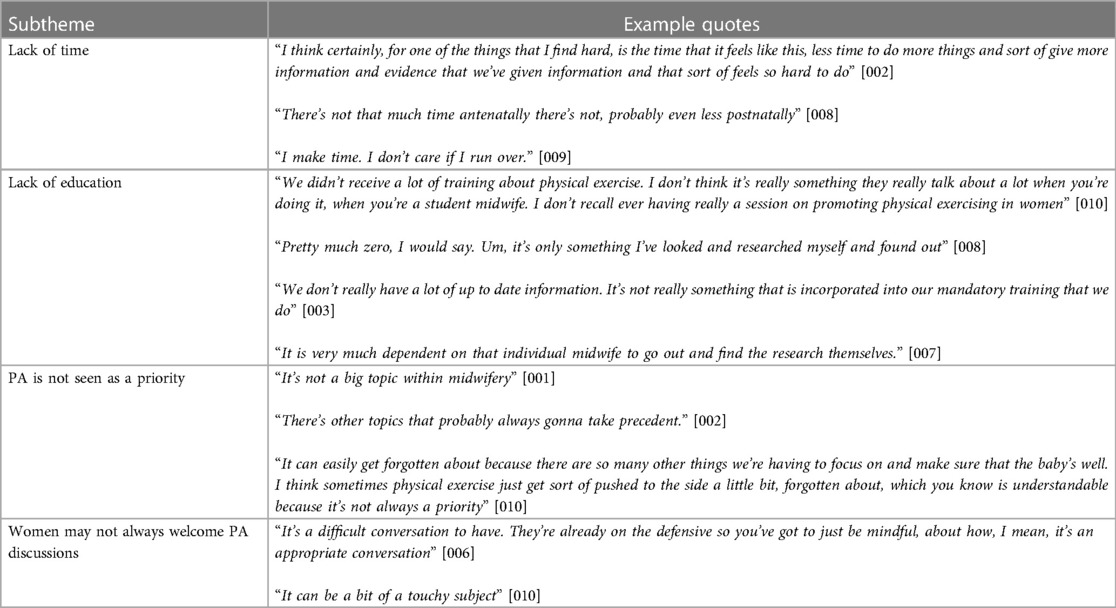

There were four themes regarding the extrinsic barriers limiting PA advice provision (Table 5). Lack of time was reported by all midwives as limiting provision of PA advice. Many midwives highlighted the sheer volume of general pregnancy information to be communicated in appointments. Lack of midwifery education was also a major theme, at both undergraduate and postgraduate level. Most midwives had little to no experience of PA education as a student midwife, with PA covered as a topic within a lecture, if at all. Concerning postgraduate training, no midwives had received PA training within mandatory training or study days. Many midwives instead relied on self-directed learning regarding PA in their own time. PA not being seen as a priority was also commonly noted. A woman's personal attitude to PA was discussed to also act as a barrier, with midwives finding discussing PA can be a difficult or touchy situation, with concerns that women may feel judged or patronized.

3.2.5 Theme 5: solutions to allow midwives to promote PA

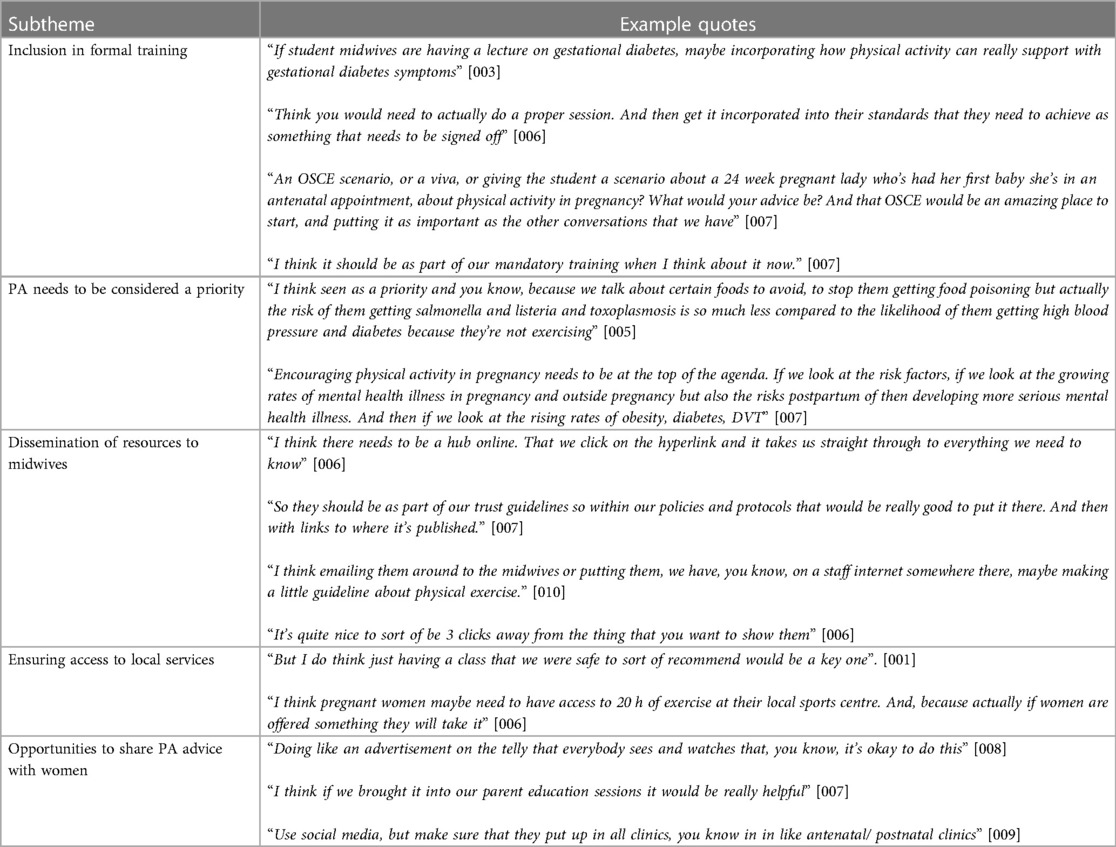

The participants proposed several solutions to enable midwives to promote PA, which emerged as five subthemes (Table 6). Many midwives suggested inclusion of PA in midwife training and assessment, at both undergraduate and postgraduate level, such as incorporating PA into mandatory training. A second subtheme that was identified was the need for PA to be considered with increased priority. Many midwives stressed the need for improved dissemination of resources on PA, including utilising online platforms such as the trust intranet, or QR codes. Ensuring access to local services, (such as pregnancy-specific classes, free or subsidised gym schemes, or hospital-run classes) was also highlighted, with midwives wishing for free and safe services to recommend. Other opportunities for sharing advice with women were also suggested, including parent education sessions, television campaigns, and display of resources in waiting areas. Despite the interviewer asking about solutions regarding provision of PA to both pregnant and postpartum women, most participants discussed solutions mainly in the context of antenatal advice.

3.2.6 Theme 6: optimising delivery of PA advice

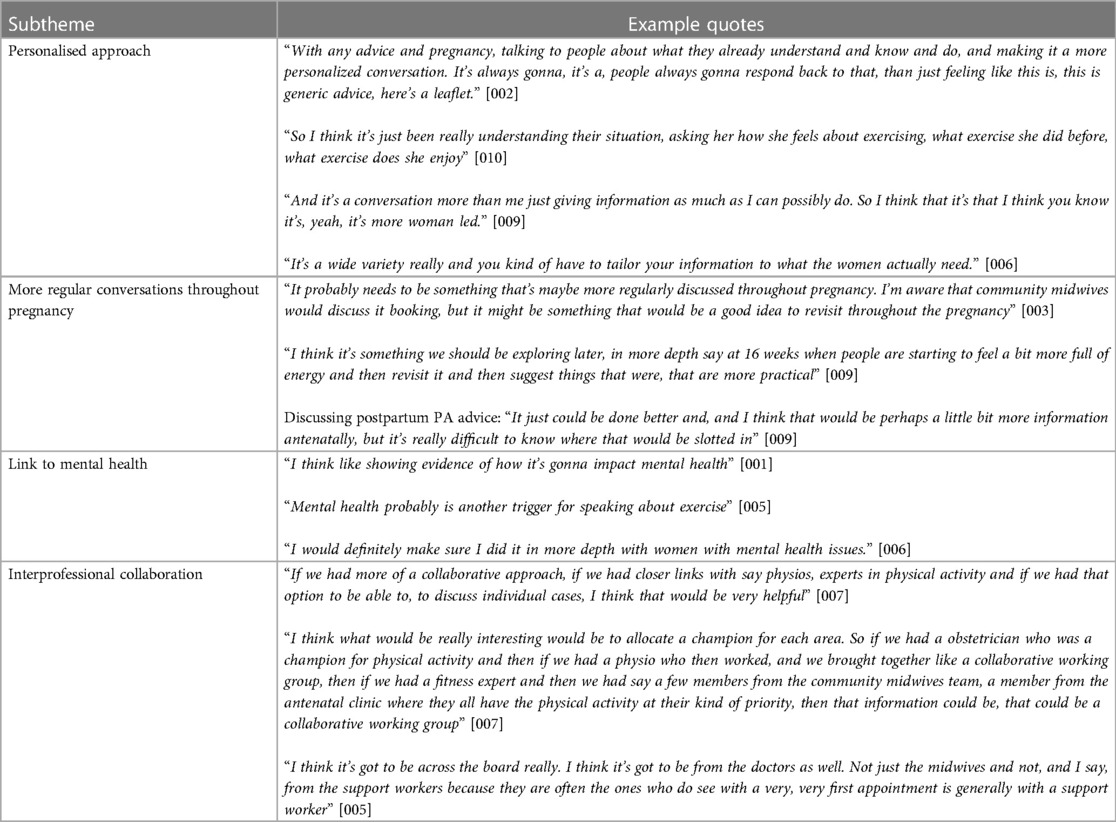

Four subthemes emerged regarding methods by which individual midwives may optimise delivery of PA advice (Table 7). Many midwives discussed how a personalised approach helps PA promotion. Midwives also suggested PA could be discussed further along the pregnancy journey, with one midwife also suggesting postpartum PA advice be incorporated into antenatal care. Many midwives stated that PA advice was often included as part of mental health conversations and promoted through that. The need for inter-professional collaboration was discussed by all midwives. Midwifery support workers, physiotherapists, doctors, and exercise specialists were mentioned as professionals who could help promote PA. Again, similar to theme five, most participants discussed methods mainly in the context of delivering PA advice to pregnant women specifically.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate midwives’ current role and knowledge regarding the provision of PA advice to pregnant and postpartum women. It aimed to understand the challenges and barriers midwives face when providing PA advice and find possible solutions to allow effective promotion of PA for both groups. To this research team's knowledge, this was the first UK study to explore the role of midwives in providing PA advice to both pregnant and postpartum women; and examine the challenges and possible solutions regarding PA promotion for both groups. This study found midwives considered providing PA advice to pregnant women as within their role, but not to postpartum women. A clear lack of PA advice provision was identified, with barriers including a lack of confidence, knowledge, time, and education. A number of solutions were proposed to allow effective promotion of PA, and to optimise delivery.

4.1 Midwives' current role and knowledge

Although NICE guidelines (20) for antenatal care include providing PA advice, the role midwives play in this provision was unclear from the guidelines. Midwives are arguably ideally placed to provide PA advice in pregnancy due to the early contact and universal access to midwives for all pregnant women. Indeed, McParlin et al. (30) had similar findings when examining midwife provision of PA advice to obese women amongst a large sample of midwives (n = 192) practising in the North East of England, with midwives considering PA promotion part of their professional role. Pregnancy was also considered an opportune time for health promotion, when women are motivated to make healthy lifestyle choices thus supporting ideas discussed by Rockliffe et al. (18). It is encouraging that many midwives appreciated the benefits provided by PA during pregnancy, including control over conditions such as gestational diabetes and raised BMI, both of which are supported by strong evidence (3). Despite the potential benefits, PA lacked discussion in pregnancy, corroborating the findings of Brown and Avery (23), who reported that women's experiences of PA advice were lacking.

This study helped to clarify the perceptions of midwives and their role in the postpartum period, previously lacking in research. Postpartum PA advice was felt by many to not be appropriate, or outside a midwife's remit, due to recentness of delivery. Interviews revealed a large variation in the dissemination of postpartum PA advice provision, with some midwives not discussing it at all. The findings of this study echo the results of Haakstad et al. (40) where only 40% of Norwegian midwives (n = 65) were found to provide postpartum PA advice as opposed to 95% at the first pregnancy related visit. The discrepancy between the involvement of UK midwives in pregnancy vs. postpartum PA guidance may reflect the NICE guidelines. NICE guidelines state PA should be discussed antenatally (20), but PA may be discussed postnatally (26). However, NICE specifies pelvic floor exercises as part of the discharge conversation, which accounts for the number of midwives in this study who solely focused on pelvic floor exercises.

There was also limited knowledge of the UK CMO PA guidance, with only two out of the ten midwives aware of the pregnancy guidance, aligning with the findings of the study by Taylor et al. (31), where only 33% HCPs were aware of the CMO guidelines in pregnancy. However, no midwives in this study were aware of the postpartum CMO guidance, compared to the 30% found by Taylor et al. (31). Differences such as a much larger sample size, and involvement of HCPs besides midwives (n = 393, 37% midwives) may account for disparities in findings. However, in this study, the midwives aware of the CMO PA infographics found them useful, identifying a missed avenue by which midwives may improve their practice. The need for dissemination of the 2019 guidelines to key stakeholders was highlighted by Foster in a 2018 presentation, and this study's findings suggest this need still exists (41).

4.2 The barriers faced by midwives

Midwives faced many barriers when providing PA advice. Lack of confidence in providing information on PA was commonly discussed, impacted by factors such as safety concerns. Low confidence was also found as a barrier in the De Vivo and Mills study (28) in their interviews of ten community midwives, where lack of confidence led to PA advice being limited to basic advice. Similarly, our study found midwives provided generic advice, or held back advice due to safety concerns. Additionally, some midwives were less confident with less physically active women, a group that could be seen as a priority. Numerous studies have identified lack of knowledge as a barrier prior to the release of the 2019 CMO guideline update (29, 30), but this study suggests there has been no improvement in knowledge levels, highlighting the poor dissemination of resources. Bright et al. (27) found in their study of Welsh midwives (n = 1,338), that some midwives may feel hypocritical when providing PA advice, due to their own lifestyle, thoughts reflected by midwives in this study, but conversely, they may also be well placed to understand the difficulties of being physically active and have insight and empathy. However, our findings suggest that difficult conversations were not limited to midwives with higher BMIs: one midwife, who described herself as petite, found providing PA advice to women with raised BMIs was not always received well, due to a perceived lack of understanding of the woman's situation.

In terms of extrinsic barriers, lack of time was a predominant theme throughout all interviews, aligning with current research (28, 32). This reflects the wider resourcing based issues such as staffing in the NHS (42). Although midwives have a “high” contact with pregnant women, the list of topics to be covered is extensive (20), as many midwives discussed. However, in this study, two midwives stated they provided PA advice despite time pressures, but at the cost of other topics, or running over appointments. Lack of education regarding PA has been identified as a barrier in multiple studies (28, 29, 32), with this study finding many midwives experienced minimal undergraduate PA training, and almost all midwives reporting no formal postgraduate PA training. However, despite this, many midwives in this study discussed how their personal interest in PA had driven them to seek out information in their own time and this aligns with other research into HCPs and their training on PA (42). However, the failure to include PA in formal training and subsequent need for reliance on self-directed learning may add pressure to midwives who are already under stress, as many in the interviews discussed. Many midwives commented that PA was often not a priority or forgotten compared to other topics, such as the baby's growth and health, that instead took precedent. This contradicts the findings of the Bright et al. (27) study, where only 6.1% of midwives felt there were more important things to do. However, the Bright et al. study was conducted in the first half 2019, it may be that in the four years since data collection by Bright et al. (27) factors such as COVID-19 and increasing mental health problems, have pushed PA to the side in appointments (43).

4.3 Solutions and optimising delivery of PA

This study explored midwives' perceptions of how PA advice provision may be practically improved, a topic with limited coverage besides the De Vivo and Mills (28) study. Both undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums were noted to be lacking in PA content, providing an opportunity for improvement, as many midwives discussed. Both this study and the De Vivo and Mills (28) study found midwives suggested PA be incorporated in mandatory training and the student midwife curriculum. This study also found additional suggestions including methods for assessment, such as OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) scenarios. The idea that midwives should not be expected to complete this training in their own time, was also discussed, to encourage maximum engagement. These suggestions are supported by the findings of Taylor et al. (31), where an education programme significantly increased HCP confidence and frequency of PA conversations with both pregnant and postpartum women. The education programme, titled “This Mum Moves”, aimed to provide HCPs with education regarding the pregnancy and postpartum PA guidelines. Prior to training, Taylor et al. (31) found only 5.6% of midwives were “confident” or “highly” confident providing PA advice to pregnant women, which rose to 71.7% after training (p < 0.001). Similarly, the proportion “confident” or “highly” “confident” providing PA advice to postpartum women rose from 5.6% to 72.8%. Dissemination of resources was another theme that many midwives proposed as an actionable solution. Many midwives suggested utilising electronic platforms to share resources, such as an online hub, integration into trust guidelines, or inclusion in emails. Many reported their trust had recently switched to paperless notes, which some suggested that if electronic resources were utilised effectively, it may buy midwives back some time to have meaningful conversations. Also, some midwives proposed putting PA resources in a central location, so they can be obtained as quickly as possible to help patients efficiently. Additionally, seeing PA as a priority was emphasised by several participants, including one who stated that “encouraging physical activity in pregnancy needs to be at the top of the agenda”.

Methods individual midwives could take to optimise PA delivery were also suggested. Novel methods of optimising delivery of PA advice, aligned to the needs of women emerged, of which had not been seen in previous similar studies. This includes incorporating PA into mental health discussions, which is often discussed due to the high prevalence of mental health problems in both pregnancy and the postpartum period (6). As there is strong evidence for PA reducing risk of postpartum depression (3), including PA in mental health discussions with women is an appropriate time to fit postpartum PA into appointments, without it feeling like an extra topic. NICE guidance states PA should be discussed at the booking appointment, but it is at the individual midwife's discretion whether PA advice is revisited throughout pregnancy (20). However, many midwives suggested incorporating PA into discussion more regularly through pregnancy as a way of optimising delivery, especially due to a woman's fluctuating energy levels and severity of pregnancy side-effects. One midwife also suggested postpartum PA advice be incorporated into antenatal appointments. Although NICE guidelines do recommend midwives discuss the postpartum period during pregnancy regarding topics such as feeding, there is no mention of postpartum PA (20). Like Walker et al. (19) who suggested contraception, usually only discussed following birth, be incorporated antenatally to improve provision, the same could be done for PA. The need for interprofessional collaboration was discussed by many midwives, with midwifery support workers, physiotherapists, doctors, and exercise specialists mentioned as professionals who could help support provision of PA advice. This is particularly important if any pregnancy or postpartum complications arise, referring pregnant and postpartum patients to the care of qualified exercise specialists will remove the midwife's responsibility to provide comprehensive guidance on what the woman can and cannot do in terms of PA. There was a suggestion of establishing a PA clinical champion within each HCP field; similar to a solution proposed in the De Vivo and Mills (28) study, highlighting a practical approach by which interprofessional collaboration may be facilitated. Other approaches included joint clinics and multidisciplinary teams to discuss individual cases. This means midwives will be adequately supported by HCPs and exercise professionals, who may have more knowledge and experience in providing more personalised PA advice.

4.4 Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. The use of semi-structured interviews allowed for rich data collection (36). The study also identified novel findings such as the inclusion of PA advice for mental wellbeing. Furthermore, as it is important to learn from the process of conducting research and evaluations (44), this study details what worked well and how, when undertaking research with midwives, it can help to inform future investigations. A rigorous approach to data analysis was taken by following Braun and Clarke's six steps as a guide (35). Additionally, the use of two coders reduced subjectivity, and discussion of coding allowed for consensus and enhanced understanding (39). Training on data collection and refinement of interview techniques was conducted, in order to help participants share their informative accounts. Despite the small sample size, this study reached saturation, and has a similar number of participants to other related studies (28). However, as all participants were working in the Yorkshire and Humber region, findings may not reflect the whole UK, as practice may differ by trust. Although participants were from the same geographical area, there was a range in setting of work, band, and years of experience.

It is likely that midwives who are willing to be interviewed in their personal time may be more invested in providing PA advice. This volunteer bias means the views and experiences of the midwives in this study may not accurately reflect all midwives. Additionally, this sample of midwives all perform regular PA, with none classed as physically inactive. This may also influence participation and nature of responses. However, even so, these midwives who are more likely to have an interest in PA, still felt lack of knowledge, confidence, and education in PA affected their practice, themes that will likely also ring true for the general midwife population.

4.5 Implications for practice and research

We aim to share the findings of this research widely through various regional and national PA networks such as the Regional Public Health Networks, the Regional Physical Activity Delivery Networks (e.g., Active Leeds, and Active Partners Trust/Making our Move and Move More Derby in the East Midlands), the UK CMO Physical Activity Communication Network, and the Moving Medicine Network. The goal is to ensure that colleagues can benefit from the insights gained during both the research process and the outcomes.

To determine the current level of PA advice provided to pregnant and postpartum women, a service evaluation or clinical audit across multiple NHS trusts may be beneficial. The findings from this study could help shape the questions to be asked. This would encompass all midwives within a trust, not just those who had expressed interest and therefore more likely to provide PA advice. Future research should also include midwives with lower levels of PA themselves and allow exploration of how this may affect the advice they give, and the barriers and facilitators they encounter when doing so. In addition, just as the Taylor et al. (31) study examined the effect of postgraduate training on midwives' confidence and knowledge regarding PA, a similar study could be conducted for student midwives, to provide rationale for the inclusion of PA in UG curriculums. In this study, there was a sense that postpartum PA guidance fell outside a midwife's remit. Therefore, it would be useful to conduct similar studies on health visitors, GPs, and midwifery support workers (HCPs identified by the midwives in this study as potentially involved in providing PA advice) to determine who, if anyone, has the role of providing postpartum PA guidance.

5 Conclusions

This was one of the first studies to address midwifery PA advice provision to both pregnant and postpartum women. Though midwives consider themselves ideally placed to provide PA advice to pregnant women, postpartum PA was felt to be outside the remit of midwives. Many barriers such as lack of time, education, and confidence were expected based on previous studies and were found as subthemes in this study. Multiple solutions were proposed, some of which bear similarity to the suggestion of existing studies, but many solutions are novel and locally actionable. Further research is needed to determine the current level of PA advice provision for pregnant and postpartum women, the determinants inactive midwives encounter when promoting PA, and also explore the role of other HCPs involved in maternity care.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of concerns about participant privacy and confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toYy5ueWtqYWVyQGxlZWRzLmFjLnVr.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Faculty of Biological Sciences Ethics Committee at the University of Leeds (27th July 2020/BIOSCO19-039). The study was conducted in accordance with the local and institutional requirements. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. CN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the participants who gave up their time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2024.1369534/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Warburton DER, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol. (2017) 32:541–56. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437

2. Mahindru A, Patil P, Agrawal V. Role of physical activity on mental health and well-being: a review. Cureus. (2023) 15:e33475. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33475

3. Dipietro L, Evenson KR, Bloodgood B, Sprow K, Troiano RP, Piercy KL, et al. Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum: an umbrella review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2019) 51:1292–302. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941

4. Weng YM, Green J, Yu JJ, Zhang HY, Cui H. The relationship between incidence of cesarean section and physical activity during pregnancy among pregnant women of diverse age groups: dose–response meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2023) 164(2):504–15. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14915

5. Kołomańska-Bogucka D, Mazur-Bialy AI. Physical activity and the occurrence of postnatal depression-a systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas). (2019) 55(9):560. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090560

6. NICE. Depression - Antenatal and Postnatal. (2022). Available online at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression-antenatal-postnatal/ (accessed July 16, 2023).

7. Ferrari N, Joisten C. Impact of physical activity on course and outcome of pregnancy from pre- to postnatal. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2021) 75:1698–709. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-00904-7

8. Makama M, Skouteris H, Moran LJ, Lim S. Reducing postpartum weight retention: a review of the implementation challenges of postpartum lifestyle interventions. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(9):1891. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091891

9. Department Of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers Recommendations 2017: Physical Activity in Pregnancy. (2017). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/831429/Withdrawn_CMO_physical_activity_pregnant_women_infographic.pdf (accessed August 11, 2023).

10. Department Of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf (accessed February 21, 2023).

11. ACOG. Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period: ACOG committee opinion, number 804. Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 135:e178–88. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004266

12. Fiona CB, Salih SA-A, Stuart B, Katja B, Matthew PB, Greet C, et al. World health organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54:1451. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

13. Coll CDVN, Domingues MR, Hallal PC, Da Silva ICM, Bassani DG, Matijasevich A, et al. Changes in leisure-time physical activity among Brazilian pregnant women: comparison between two birth cohort studies (2004–2015). BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:119. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4036-y

14. Daly N, Mitchell C, Farren M, Kennelly MM, Hussey J, Turner MJ. Maternal obesity and physical activity and exercise levels as pregnancy advances: an observational study. Ir J Med Sci. (2016) 185:357–70. doi: 10.1007/s11845-015-1340-3

15. Macrae EHR. “Provide clarity and consistency”: the practicalities of following UK national policies and advice for exercise and sport during pregnancy and early motherhood. Int J Sport Policy Politics. (2020) 12:147–61. doi: 10.1080/19406940.2019.1646302

16. Saligheh M, Mcnamara B, Rooney R. Perceived barriers and enablers of physical activity in postpartum women: a qualitative approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0908-x

17. Shelton SL, Lee S-YS. Women’s self-reported factors that influence their postpartum exercise levels. Nurs Womens Health. (2018) 22:148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2018.02.003

18. Rockliffe L, Peters S, Heazell AEP, Smith DM. Factors influencing health behaviour change during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Health Psychol Rev. (2021) 15:613–32. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2021.1938632

19. Walker RE, Choi TST, Quong S, Hodges R, Truby H, Kumar A. “It’s not easy”—a qualitative study of lifestyle change during pregnancy. Women Birth. (2020) 33:e363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.09.003

20. NICE. Antenatal care. NICE Guideline [NG201]. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng201 (accessed June 24, 2023).

21. Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, Hood K, Christian-Brown A, Adab P, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet. (2016) 388:2492–500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31893-1

22. NICE. Behaviour Change: Individual Approaches. NICE Guideline [PH49]. (2014). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49/ (accessed June 24, 2023).

23. Brown A, Avery A. Healthy weight management during pregnancy: what advice and information is being provided. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2012) 25:378–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01231.x

24. Goddard L, Astbury NM, Mcmanus RJ, Tucker K, Maclellan J. Clinical guidelines for the management of weight during pregnancy: a qualitative evidence synthesis of practice recommendations across NHS trusts in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2023) 23:164. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05343-9

25. Talbot H, Strong E, Peters S, Smith DM. Behaviour change opportunities at mother and baby checks in primary care: a qualitative investigation of the experiences of GPs. Br J Gen Pract. (2018) 68:e252–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X695477

26. NICE. Postnatal Care. NICE Guideline [NG194]. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng194 (accessed June 24, 2023).

27. Bright D, Gray BJ, Kyle RG, Bolton S, Davies AR. Factors influencing initiation of health behaviour conversations with patients: cross-sectional study of nurses, midwives, and healthcare support workers in Wales. J Adv Nurs. (2021) 77:4427–38. doi: 10.1111/jan.14926

28. De Vivo M, Mills H. “They turn to you first for everything”: insights into midwives’ perspectives of providing physical activity advice and guidance to pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:462. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2607-x

29. Hopkinson Y, Hill DM, Fellows L, Fryer S. Midwives understanding of physical activity guidelines during pregnancy. Midwifery. (2018) 59:23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.12.019

30. Mcparlin C, Bell R, Robson SC, Muirhead CR, Araújo-Soares V. What helps or hinders midwives to implement physical activity guidelines for obese pregnant women? A questionnaire survey using the theoretical domains framework. Midwifery. (2017) 49:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.09.015

31. Taylor KA, de Vivo M, Mills H, Hurst P, Draper S, Foad A. Embedding physical activity guidance during pregnancy and in postpartum care: “this mum moves” enhances professional practice of midwives and health visitors. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. (2024) 69(1):101–9. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13547

32. Lucas G, Olander EK, Salmon D. Healthcare professionals’ views on supporting young mothers with eating and moving during and after pregnancy: an interview study using the COM-B framework. Health Soc Care Community. (2020) 28:69–80. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12841

33. Vishnubala D, Iqbal A, Marino K, Whatmough S, Barker R, Salman D, et al. UK Doctors delivering physical activity advice: what are the challenges and possible solutions? A qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(19):12030. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912030

34. Stead A, Vishnubala D, Marino KR, Iqbal A, Pringle A, Nykjaer C. UK Physiotherapists delivering physical activity advice: what are the challenges and possible solutions? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e069372. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069372

36. Clarke V, Braun V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage (2013).

37. O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods. (2020) 19:1609406919899220. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220

38. Fahy P. Addressing some common problems in transcript analysis. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. (2001) 1. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v1i2.321

39. Church S, Dunn M, Prokopy L. Benefits to qualitative data quality with multiple coders: two case studies in multi-coder data analysis. J Rural Soc Sci. (2019) 34(1):2.37559698

40. Haakstad LAH, Mjønerud JMF, Dalhaug EM. Mamma mia! Norwegian Midwives’ practices and views about gestational weight gain, physical activity, and nutrition. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1463. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01463

41. Foster C. (2018). Overview of the 2019 physical activity guidelines and implementation plans. Fuse Physical Activity Workshops, Durham, UK.

42. Kime N, Pringle A, Zwolinsky S, Vishnubala D. How prepared are healthcare professionals for delivering physical activity guidance to those with diabetes? A formative evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:8. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4852-0

43. WHO. COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed August 15, 2023).

Keywords: physical activity, exercise, pregnancy, postpartum, midwives, knowledge, awareness, advice

Citation: Mitra M, Marino K, Vishnubala D, Pringle A and Nykjaer C (2024) UK midwives delivering physical activity advice; what are the challenges and possible solutions?. Front. Sports Act. Living 6:1369534. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1369534

Received: 12 January 2024; Accepted: 15 May 2024;

Published: 3 June 2024.

Edited by:

Hayley Mills, Canterbury Christ Church University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Anna Szumilewicz, Gdansk University of Physical Education and Sport, PolandRita Santos-Rocha, Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, Portugal

© 2024 Mitra, Marino, Vishnubala, Pringle and Nykjaer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Camilla Nykjaer, Yy5ueWtqYWVyQGxlZWRzLmFjLnVr

Marina Mitra

Marina Mitra Katherine Marino2

Katherine Marino2 Andy Pringle

Andy Pringle Camilla Nykjaer

Camilla Nykjaer