94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Sports Act. Living, 10 August 2023

Sec. The History, Culture and Sociology of Sports

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1232839

The canon of traditional academia has gradually expanded in the last six decades. Since the Black Arts Movement exploded in 1965, African American literature has represented a challenge to the widely accepted Eurocentric narratives taught in American universities. Situated within the Black Power Movement, the artists and intellectuals in the Black Arts Movement aligned their music, literature, drama, and visual arts with the ideologies of Black self-determination, racial pride, economic empowerment, and the creation of political and cultural institutions (1). While the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s produced many artists and writers who focused their work on the political injustices of the time, Gates (2) specifically noted the Black Women's Literary Renaissance of the 1970s (i.e., Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Maya Angelou) as a key factor in broadening the validity of accepted academic narratives.

Since then, the legacy of the Black Arts Movement has made way for intellectuals in other fields to disrupt the center of traditional academia's Eurocentric narratives. In particular, as the revenue of college sports has increased, the field of sport sociology has exponentially grown to include Black perspectives. Sport sociologists have written scholarship through the prism of Black Americans to illustrate phenomena such as racial identity development (3–5), masculinity (6, 7), stereotypes (8–11), activism (12–14), academic reform (15–17), academic performance and achievement (18–21), religion (22, 23), and antideficit frameworks (24, 25). The rigorous study of sport sociology has created a space for academic credibility:

It is a thing of wonder to behold the various ways in which our specialties and the works we explicate and teach have moved, if not exactly from the margins to the center of the profession of literature, at least from defensive postures to a position of generally accepted validity (2, p. 11).

Black narratives are abundant in movements that resist racism and oppression in America. Two fields that intentionally disrupt political and cultural consciousness are sport and HipHop. To demonstrate the validity of this challenge, two scholar-activists discuss the relationship between HipHop and sport as a cultural, theoretical, and global phenomenon.

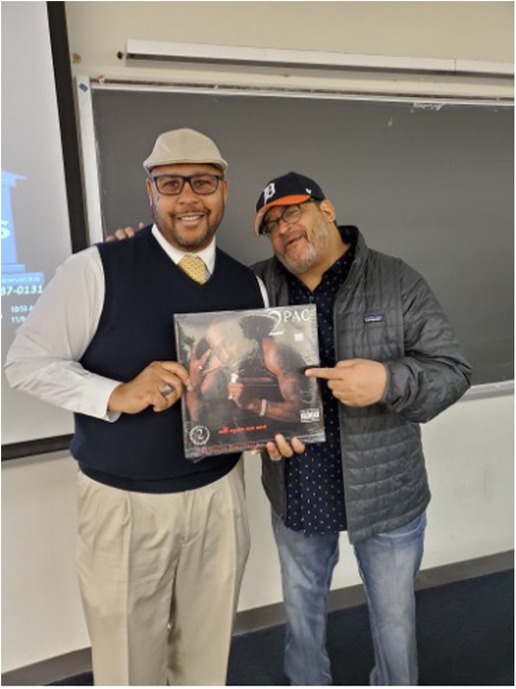

Each of the Black male professors featured in this documented dialog has made major contributions to Black literature and education. Both men continue to be recognized for their distinguished innovation through awards and fellowships (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. C. Keith Harrison and Michael Eric Dyson at Georgetown University near the campus at a breakfast spot before Dyson's class on HipHop in the Fall semester of 2019. The photograph is taken from the first author's collection and courtesy, circa November 2019.

Professor Keith Harrison is the founding director of the Business of Hip Hop Innovation and Creative Industries Certificate at the University of Central Florida (UCF). He has served as Associate Unit Head/Chief Academic Officer of the UCF's DeVos Sport Business Management graduate program in the College of Business and founding director (2006–2014) of The Minor That's Major™ Sport Business Management undergraduate program. He has held faculty positions at Washington State University, the University of Michigan, Arizona State University, and the UCF.

As a former scholar-baller, he played football at Cerritos College and West Texas A&M where he started as a center and graduated after making the honor roll twice. He went on to earn his graduate degree at California State University, Dominguez Hills, and his doctorate in higher education from the University of Southern California. He has published numerous peer-reviewed articles and academic books on sport sociology and HipHop in higher education. He is a senior Editor-in-Chief of the peer-reviewed Journal of Higher Education Athletics & Innovation, the president and co-founder of scholarballer.org, and a researcher for the National Football League's good business diversity and inclusion series. In 2021, he earned the prestigious Harvard University Hutchins Center for African and African American Research Nasir Jones HipHop Fellowship.

Professor Michael Eric Dyson is a professor, pastor, author, and media personality. He has held faculty positions at Princeton, Brown, Georgetown, and Vanderbilt, where he is a Distinguished Professor at the time of this publication. His published works span a wide range of Black culture, such as civil rights, HipHop, racism in America, and politics. With over 25 books under his name, seven have become New York Times bestsellers, including Long time coming: reckoning with race in America, tears we cannot stop: a sermon to White America, and Entertaining race: performing blackness in America. He has won such awards as the Langston Hughes Medal, American Book Award, and two NAACP Image Awards. In addition to his lectures at universities, Dyson preaches at churches around New York and Virginia.

Professor Michael Eric Dyson after his PhD at Princeton took academe, culture, and higher education by storm with his pulse for African American studies among other intellectual pursuits. In essence, he pushed the “status quo” with his passionate knowledge and unprecedented wordsmith abilities. On a personal level, his book “Between God and Gangsta Rap” was life-changing for the first author. In 1996 after his first year as a full-time faculty member at Washington State University, he attended the National Black Graduate Student Conference at Claremont, CA. During Professor Dyson's keynote, he witnessed the synergy and merger of higher education, sports, HipHop, and much more. Dyson's attire was a three-piece suit with Michael Jordan sneakers on, better known as “J's.” The point of all this is that Dr. Dyson made it cool to study HipHop in the academe, joining other pioneers such as Drs. Tricia Rose, Robin D.G. Kelley, and Cheryl L. Keyes. In short, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson made school cool, and this one-on-one interview attempts to capture his sagacity on the topic and HipHop/Sport.

Professor Harrison: Professor Dyson, great to see you!

Professor Dyson: Good to see you too, bro!

Professor Harrison: The first question is: Why is a book read like this on education, HipHop and Sport: The Fifth Element timely and possibly timeless?

Professor Dyson: Well, it is incredibly important, timely right now, because sports and HipHop have gone hand in hand and forging connections between young Black men especially, who are stars in one arena who identify with stars, and another. So, people who are active in the political, in the sports arena, the athletic arena identify with rappers, rappers identify with ballers, ballers want to be rappers, rappers want to be ballers right? Magic Johnson said the same thing on Arsenio Hall. So, you know when you think about this is the fifth element right? That kind of knowledge, that kind of sports, that kind of education, and the convergence of those is extremely important now because we can interpret so much of what’s going on with Black men athletically through the lens of HipHop. The ideas, the identities, the freedom, the hairstyles, the clothing style, the sartorial choices, all of that deeply imbued with a consciousness of HipHop culture and the freedom and liberty and emancipation which those styles and that appropriation give rise.

It’s timeless because constantly we have to think about that interaction, that convergence, and how it will forever impact how we know, think of, and look at young Black men. HipHop culture [is] 40 years old now maybe, but it has a deep and profound impact on expressive and athletic culture within African American society. And it is exploded exponentially beyond the borders and boundaries of Black masculinity itself. It articulates Black masculine style, desire, and ambition, but it also corrals people in from broader society into privileged circle of communication and expression among these Black men and women. And how it allows Black pop culture to be a forum to argue about, or at least engage in discussions over, the importance of Black identity. So, it is extremely timely and timeless.

Professor Harrison: And you’ve answered my second question Professor Dyson. I was going to ask about the intersectionality between HipHop and Sports. You’ve already hit that.

Professor Dyson: Thank you, sir.

Professor Harrison: Welcome. I co-teach a class with Reggie Saunders on the “Business of Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Sport.” You know he works at the Jordan Brand. Why is it important that two academics—my colleague and former Ph.D. student Eddie Comeaux, the first editor, me the second co-editor—and both pulled Reggie in on this project? Why is it important, Professor Dyson, to have someone like Reggie involved in academia? In a book like this.

Professor Dyson: Yeah well, ‘cause Reggie played and knows the game from all sides (e.g., business, culture, sports).

Professor Harrison: Reggie is the Jordan's right-hand man with sneakers.

Professor Dyson: Right exactly, well that is extremely important. Because you know people who are in the world of converse people who are in the world of creative ideas that lead to subsequent development of actual products. You know, are extremely important in helping to bridge the gulf between theory and practice. You know, how is it that ideals and ideas about Blackness, about Black masculine flare, flavor the wide receiver on the gridiron, a bit flagrant. And, you know engaging in what one would see as exaggerated behavior.

How is it that Black masculine style, in basketball with a kind of “moxie” the “chutzpah,” the kind of you know flare, the kind of charisma? Some would see it as arrogance but beautiful expressions and articulations of Black masculine style. How does that get reproduced and commodified—reproduced and commodified in a culture where products are the result of an imagination? And how does that Black imagination work? And how do we bridge the gulf between what we think of as a cultural articulation and subsequent commercial expression of that articulation? [It] is very good for brother Saunders to be there because he works on the cutting edge of trying to figure these products out and working with arguably the greatest, iconic figure within sports in the last half-century.

Professor Harrison: That’s a (w)rap Professor Dyson (pun intended).

In 1996, I attended the National Black Graduate Student Conference in Claremont, CA. Professor Michael Eric Dyson gave the keynote in a suit with his “J's” [Jordan brand shoes] on. In contemporary society, sneakers are the trend and thing to wear on your 'fit regardless of how casual or dressed up one is. This was Dr. Dyson's statement of education, HipHop, and sport over 25 years ago. How educationally dope!!

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

We thank Zana Krakic and Shay Lewis for their assistance with the transcription of this interview.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Black arts movement (1965–1975). Available at: https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/arts#:∼:text=The%20Black%20Arts%20Movement%20started,%2DHeron%2C%20and%20Thelonious%20Monk (Accessed May 26, 2023).

2. Gates H. Introduction: “tell me, sir,…what is ‘black’ literature?”. PMLA. (1990) 105(1):11–22. doi: 10.1632/S0030812900069431

3. Bimper A, Harrison L. Meet me at the crossroads: African American athletic and racial identity. Quest. (2011) 63(3):275–88. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2011.10483681

4. Harrison L, Harrison CK, Moore L. African American racial identity and sport. Sport Educ Soc. (2002) 7(2):121–33. doi: 10.1080/1357332022000018823

5. Nasir N, Hand V. From the court to the classroom: opportunities for engagement, learning, and identity in basketball and classroom mathematics. J Learn Sci. (2008) 17(2):143–79. doi: 10.1080/10508400801986108

6. Martin B, Harris F. Examining productive conceptions of masculinities: lessons learned from academically driven African American male student-athlete. J Men's Stud. (2006) 14(3):359–78. doi: 10.3149/jms.1403.359

7. Singer J. Understanding racism through the eyes of African American male student-athlete. Race Ethn Educ. (2005) 8(4):365–86. doi: 10.1080/13613320500323963

8. Edwards H. The black “dumb jock”: an American sports tragedy. College Board Review. (1984) 131:8–13.

9. Griffin W. Who is whistling vivaldi: how black football players engage with stereotype threats in college. Int J Qual Stud Educ. (2016) 30(4):354–69. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2016.1250174

10. Sailes G. An investigation of campus stereotypes: the myth of black athletic superiority and the dumb jock stereotype. Sociol Sport J. (1993) 10(1):88–97. doi: 10.1123/ssj.10.1.88

11. Stone J, Lynch C, Sjomeling M, Darley J. Stereotype threat effects on black and white athletic performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1999) 77(6):1213–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1213

12. Brooks D, Knox R. I would not trade it for the world: black women student-athletes, activism, and allyship in 2020–2021. J Clin Sport Psychol. (2022) 16(4):406–16. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2021-0063

13. Edwards H. The sources of the black athlete’s superiority. Black Scholar. (1971) 3(3):32–41. doi: 10.1080/00064246.1971.11431195

14. Reese R. The lack of political activism among today’s black student-athlete. J High Educ Athl Innovation. (2017) 2:123–31. doi: 10.15763/issn.2376-5267.2017.1.2.123-131

15. Brooks D, Althouse R. Racism in college athletics: the African-American athlete’s experience. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology (2000).

16. Comeaux E. Rethinking academic reform and encouraging organizational innovation: implications for stakeholder management in college sports. Innov High Educ. (2013) 38(4):281–93. doi: 10.1007/s10755-012-9240-1

17. Curry C. A platform for 21st century reform in college athletics. Black Scholar. (1996) 26(1):26–9. doi: 10.1080/00064246.1996.11430768

18. Adler P, Adler P. From idealism to pragmatic detachment: the academic performance of college athletes. Sociol Educ. (1985) 58(4):241–50. doi: 10.2307/2112226

19. Comeaux E, Harrison CK. A conceptual model of academic success for student-athletes. Educ Res. (2011) 40(5):235–45. doi: 10.3102/0013189X11415260

20. Harper S, Williams C, Blackman H. Black male student-athletes and racial inequities in NCAA division I college sports. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education (2013).

21. Sellers R. Racial differences in the predictors for academic achievement of student-athletes in division I revenue producing sports. Sociol Sport J. (1992) 9(1):48–59. doi: 10.1123/ssj.9.1.48

22. Griffin W, Harrison CK. Giants in the frame: a 1964 photo analysis of how Malcolm X and Dr. Harry Edwards connected race, religion, and sport. Religions. (2023) 14(5):580. doi: 10.3390/rel14050580

23. Putz P. Tracing the historical contours of black muscular Christianity and American sport. Int J Hist Sport. (2022) 39(4):404–24. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2022.2076671

24. Cooper J, Cooper J. Success in the shadows: (counter) narratives of achievement from black scholar athletes at a historically black college/university. J Study Sports Athletes Educ. (2015) 9(3):145–71. doi: 10.1080/19357397.2015.1123000

Keywords: HipHop culture, sport, narrative, Black American, identity, interview (conversation)

Citation: Harrison CK and Griffin W (2023) Sitting on the porch choppin’ it up. HipHop and sports “go hand in hand”: a rap session with Michael Eric Dyson, PhD. Front. Sports Act. Living 5:1232839. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2023.1232839

Received: 1 June 2023; Accepted: 21 July 2023;

Published: 10 August 2023.

Edited by:

Nelly Lagos San Martín, University of the Bío Bío, ChileReviewed by:

Algerian Hart, Missouri State University, United States© 2023 Harrison and Griffin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: C. Keith Harrison Y2FybHRvbi5oYXJyaXNvbkB1Y2YuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.