94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Sports Act. Living, 27 October 2020

Sec. Movement Science

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.596229

Introduction: While practitioners and organizations advise against early specialization, the lack of a consistent and clear definition of early specialization reduces the impact of recommendations and policies in youth sport. An important first step in understanding the consequences of early specialization is establishing what early specialization is.

Objectives: This PRISMA-guided systematic review aimed to determine the types, characteristics, and general content of early specialization papers within the literature, and examine how early specialization has been defined and measured in order to advance knowledge toward a clear and consistent definition of early specialization.

Data sources: Four different electronic databases were searched (SPORTDiscus, Web of Science, Sports Medicine and Education Index, and Scopus). Both non data-driven and data-driven studies were included to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the literature.

Eligibility Criteria: In order to be included in the review, the paper must: (a) Focus on specialization and explicitly use the term “specialization” (b) Focus on sport and athletes (c) Be papers from a peer-reviewed (d) Be in English. And finally, (e) be available in full text.

Results: One thousand three hundred and seventy one articles were screened resulting in 129 articles included in the review after applying inclusion/exclusion criteria. Results indicated a clear discrepancy between key components of early specialization and the approaches used to classify early specializers.

Conclusion: Future research should work toward developing a valid and reliable approach to classifying early specializers and establishing a consistent definition across studies.

In 2016, the Canadian Lifestyle and Fitness Research Institute reported 77% of youth aged 5–19 participated in organized physical activity or sport. According to the Aspen Institute's Project Play (The Aspen Institute Project Play, 2019), 38% of children aged 6–12 participated in sport on a regular basis in 2018, based on United States government population statistics (Federal Interagency Forum on Child Family Statistics, 2020), equating to ~9 million American children participating in sport regularly. Similarly, Australia reported 72.3% of children under the age of 15 participated in some type of sport related activity in 2019 (May, 2019), while in England 86.4% of children ages 5–15 were reported to participate in sport in 2018 (Lange, 2019). Due to the large number of youths participating in sport globally, researchers have attempted to better understand common sport pathways, and the benefits or consequences of sport participation.

One element of youth sport that has received more attention in recent years is early specialization, originally posited as athletes focusing on one sport that is practiced, trained and competed in year-round (Hill, 1993). Models of athlete development (e.g., Developmental Model of Sport Participation) (Côté and Fraser-Thomas, 2016) suggest early specialization excludes an important period of development where youth should be participating in a range of sports with the purpose of fun and enjoyment, in favor of dedication and skill acquisition in one sport. However, expertise-centered models of skill development (e.g., Deliberate Practice Framework) (Ericsson et al., 1993) suggest that individuals who begin focused practice early have an advantage over those who start later. Despite the prominence of the notion of deliberate practice in discussions of coaching and athlete development, a growing body of literature suggests early specialization is not a prerequisite of becoming an elite athlete (Soberlak and Cote, 2003; Buckley et al., 2017; Huxley et al., 2017; Black et al., 2019). Further, particular indicators of early specialization have been linked to a host of negative consequences. Researchers have found those who specialize early are at greater risk of injury, experience increased exhaustion, and are more likely to dropout than athletes who do not (Fraser-Thomas et al., 2008; Strachan et al., 2009; Bell et al., 2018c).

Over the past 20 years, at least seven major national and international sport and athletic associations, societies, federations, and organizations have released position statements advising against the practice of early specialization amongst youth athletes (e.g., American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, International Society of Sport Psychology, National Association for Sports and Physical Education). Such strong consensus suggests there is clear and unambiguous evidence that early specialization is harmful and should be avoided in any context; however, further investigation indicates the evidence against early specialization may not be as robust as these position statements make it seem.

To begin, there are very few studies explicitly studying the consequences of early specialization; instead the literature is comprised heavily of review papers, commentaries, and editorials that reiterate previous findings. For example, a 2018 meta-analysis on specialization and overuse musculoskeletal injuries was comprised of only four studies (Bell et al., 2018c), suggesting an overall lack of research. More importantly, there is no standard definition of early specialization. Several researchers have emphasized the lack of a clear and consistent definition and have suggested that this inconsistency makes it unclear what exactly constitutes early specialization (Ferguson and Stern, 2014; Buckley et al., 2017). Some have defined early specialization as “year round intensive training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports” (Jayanthi et al., 2015) while others proposed “the time when the athlete defined one sport as being more important than other sports” (Moseid et al., 2019). Further complicating conceptualizations, some have suggested it is the type of participation (i.e., deliberate practice) that is a key marker of early specialization (Hendry and Hodges, 2018) while others designate early start age and early involvement in competitive sport as key parameters of early specialization (Baker et al., 2009). Without a consistent definition of early specialization, it is difficult to conclude early specialization is as harmful to youth as many organizations are claiming. More importantly perhaps—the lack of a clear definition of this phenomenon makes improving developmental training environments difficult given it is not clear what element of specialization (e.g., intensity, early start age, over-emphasis on winning) may be driving any negative consequences that do exist.

A recent systematic review of early specialization (DiSanti and Erickson, 2019) found that only 13 of 40 studies operationally defined “specialization.” Among the few studies that provided an operational definition of specialization, the criteria used to distinguish early specializers varied considerably. Given these inconsistent criteria, athletes could be classified into different groups depending on the definitions used, raising concerning questions of reliability and validity of conclusions regarding early specialization. An important next step in determining the relationships between early specialization and developmental and performance outcomes, as well as identifying the mechanisms behind these effects, is to clearly define early specialization.

Practice and research in sport psychology is strongly influenced by policy decisions, and therefore, unlike previous reviews which have examined only data-driven studies (Fabricant et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2018c; Walters et al., 2018), this review will also include non-data driven articles. This will provide a more thorough understanding of the current state of literature (not just the state of the research) and overall understanding of the conceptions of “early specialization” in sport psychology and related fields of study. We believe this variation to the formula of systematic reviews makes this a novel approach to understanding a concept in its entirety.

It is important to note this review did not focus on scientific or measurement-related issues concerning definitions of early specialization (e.g., the implications of a yes/no dichotomy of specialization vs. a continuous measure). The necessary evidence for an empirically substantiated definition of early specialization has yet to be established and while these issues are clearly important in the study of early specialization, they were outside the scope of this review.

The aim of this review was not to come to a conclusion about the potential consequences or benefits of early specialization, as has been done in the past; the goal of this review was to gain a thorough understanding of the entire breadth of literature on the subject. As such, the objectives of this systematic review were: (a) to determine the types, characteristics, and general content of early specialization papers within the literature, and (b) to examine how early specialization has been defined and measured in the sport literature across all fields of study (e.g., biomechanics, psychology, talent development) and populations, in order to advance knowledge toward a clear and consistent definition of early specialization.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009) was used as a guide for the exploration of literature. There is no protocol registered for this review.

In order to be included in the review, a priori criteria were established; specifically, the paper must: (a) Focus on specialization and explicitly use the term “specialization”; this meant that specialization had to be one of the key elements of the paper and not a footnote or added section. (b) Focus on sport and athletes; this ensured the focus was on sport specialization and not any other type of specialization (e.g., as it relates to medical expertise). (c) Be papers from a peer-reviewed journal rather than exclusively empirical studies; any review, commentary, editorial etc. was eligible for inclusion, in order to capture any and all definitions of early specialization and a more comprehensive picture of the current state of the literature1. (d) Be in English. And finally, (e) be available in full text.

Beginning in June 2019, in consultation with a professional research librarian a rigorous search strategy was created. To identify relevant literature, thoroughly thought out search strings and key words were used within four electronic databases (i.e., SPORTDiscus, Web of Science, Sports Medicine and Education Index, and Scopus). Key words included “specialize” and “sport” as well as synonyms such as “year-round training” or “single-sport.” For the keyword “early” synonyms included “youth,” “child,” and “adolescent.” Various combinations of these key words were used for each of the four databases. In order to ensure studies captured all components, the connector “AND” was used, and to capture all variations, truncation was used. An example of a search string used in the Scopus database is (specialize* AND early AND sport*). In order to get a thorough understanding of the research into early specialization, papers could be published any time before June 2019, with a final search date of August 2019.

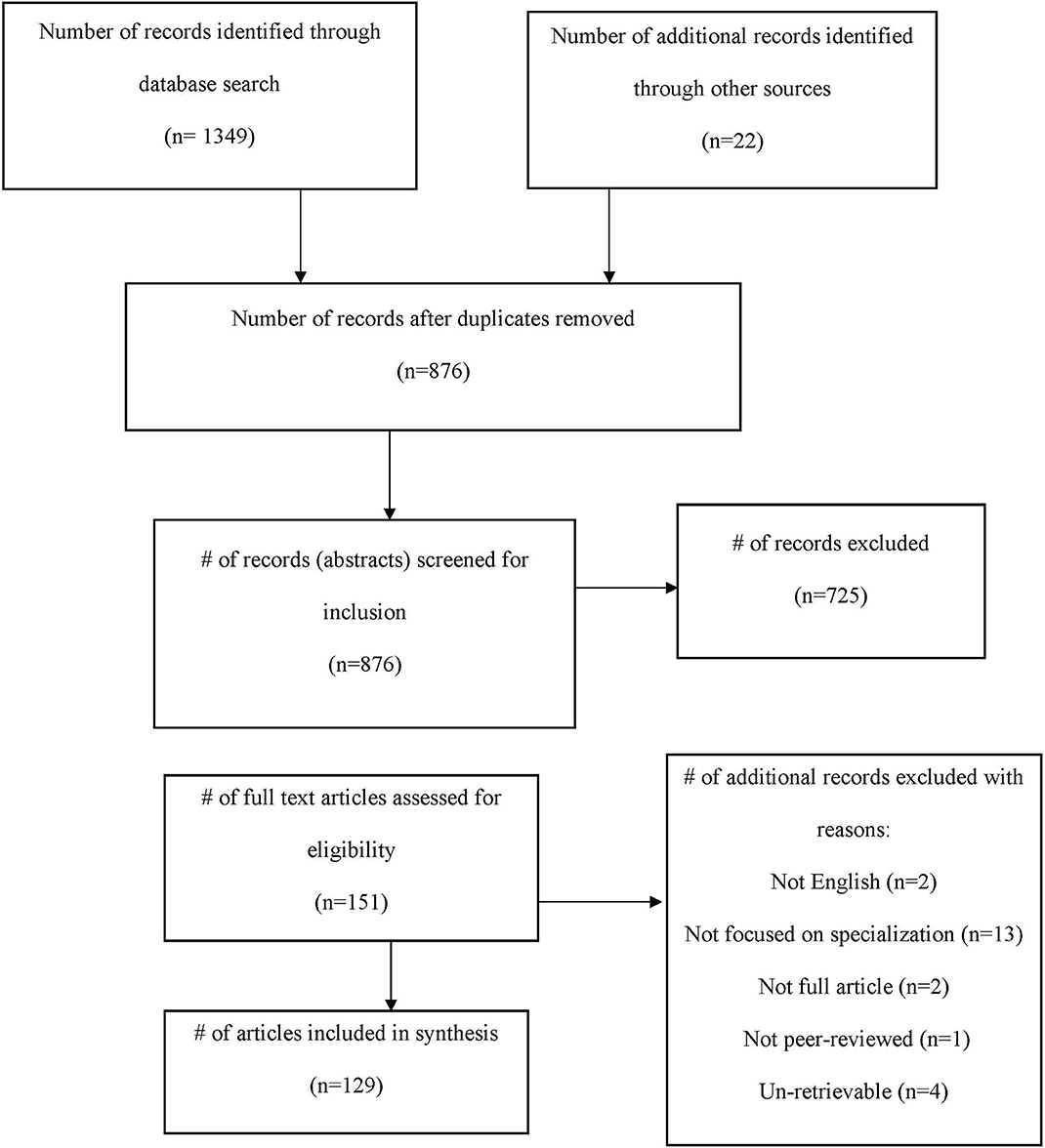

The initial search resulted in 1,349 articles. An additional 22 were identified from reference lists of seminal papers, creating a total of 1,371. After duplicates were removed, 876 articles were screened. Information from all articles including title, year of publication, authors and abstract was compiled in an excel document for organization purposes. At this stage, the titles and abstracts for all articles were screened based on the above criteria, in order to determine inclusion or exclusion. If the first author was unsure, another author was consulted, and discussion continued until a decision was reached. This screening resulted in the exclusion of 725 articles, with 151 articles for full text review. Of the 151 articles read in-full, two were found to not be in English, 13 were deemed to have not focused on sport specialization, two were conference proceedings, one was not peer-reviewed and four were un-retrievable for a total of 22 studies being excluded in this step, resulting in a final total of 129 studies included in the systematic review. For a complete flow chart, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart outlining flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review.

The remaining 129 articles were then put into a new spreadsheet for data extraction. The definition used for early specialization and purpose of each study were transferred to this new file to allow for further analysis. To cover the objectives of the review, for empirical studies, additional information regarding methods used, sample size, country of study, age and sex of sample as well as sport studied were extracted from each paper.

Given that the objectives of this review were to determine the types, characteristics, and general content of early specialization papers within the literature, and to examine how early specialization has been defined and measured in the sport literature (i.e., not to summarize outcomes) a bias assessment was not performed. Additionally, because this was not a meta-analysis, no additional statistical analyses (e.g., meta-regression) were performed on the collected papers.

To achieve the first objective of the review, studies were first categorized based on article type (i.e., non-data-driven editorials/commentaries/reviews, systematic reviews/meta analyses, and data driven studies), to gain a better understanding of the overall composition of the literature. Of the 129 papers included in the study, 43.4% (n = 56) were non-data driven papers (i.e., editorials, reviews and commentaries) and 3.8% (n = 5) were systematic reviews. The data-driven studies (n = 68; 52.7%) were further divided into those that explicitly included specialization in the purpose (i.e., specialization specific; n = 48; 37.2%) and those that did not include specialization in the purpose but met all criteria to be included in the review (i.e., specialization general; n = 20; 15.5%).

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of non-data driven papers which included 36 reviews, eight commentaries, seven editorials, and five position/consensus statements. Among this category, the areas of focus were injury, talent development and policy (for full breakdown see Table 1). The five position statements were from five different organizations, which were all either against or relatively neutral toward early specialization, indicating a negatively skewed perception of early specialization.

Table 2 presents the data from the systematic reviews. The number of studies included in each review ranged from 3 to 40. Injury was the main focus of these reviews (n = 3) while the remaining two were multidisciplinary in nature.

The characteristics of the data-driven studies are provided in Table 3. Within the 48 studies in the specialization specific category (i.e., explicitly included specialization in the purpose), there were a variety of outcomes studied. Injury studies (n = 14) were the most prominent and were often epidemiological examinations of rates or risk of injury in early specializers. Specialization characteristics such as age of specialization or prevalence were also heavily studied (n = 10). Talent development studies (n = 9) focused on the training activities of elite athletes, often comparing them to their less successful peers. Psychological outcomes (e.g., burnout, mental toughness) and physical outcomes (e.g., landing error, anterior y balance performance), were less heavily studied (i.e., n = 5 and n = 4, respectively). The least studied areas in relation to early specialization were later physical activity (n = 3), and skill transfer to other sports (n = 1). There were also single studies that considered how specialization affected (a) ability to learn basketball skills in non-basketball players (Santos et al., 2017), and (b) health related quality of life (Patel and Jayanthi, 2018). The average sample size of studies in this category was 499.7 with a range from 1 to 3090. The studies were comprised of retrospective (n = 16), cross-sectional (n = 15), case control (n = 8), descriptive epidemiological (n = 4), longitudinal (n = 1), prospective (n = 1), case study (n = 1), case report (n = 1), and a single cohort studies. Studies came from a total of 11 different countries and there was a large variety of individual and team sports examined.

Finally, specialization general studies (i.e., did not explicitly include specialization in the purpose) were largely comprised of talent development studies (n = 16). These studies generally focused on the developmental activities of athletes who became elite or differences between elite and non-elite athletes, which meant that while early specialization was a focus in the article, the actual purpose of the paper was not necessarily to advance understanding of early specialization. The average sample size was 314 with a range from 12 to 1,558. Studies were retrospective (n = 17) or cross-sectional (n = 3) with one having a combined longitudinal/retrospective design. Participants were generally either males only or mixed samples of males and females, with only one study examining females only. Lastly, data was collected in nine different countries.

As the second objective of the review was to examine how early specialization has been defined and measured, this section focuses on the conceptual and operational definition of early specialization as well as the approaches used to determine early specializers, across all types of papers. In their 2019 scoping review, DiSanti and Erickson (2019) established that year-round intense training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports was the most commonly used definition in empirical studies. In line with this review of empirical studies, the four key components of this definition were used as a starting point for our analysis (i.e., year-round, intense training, single sport, and exclusion of other sports). Deliberate practice was also added as a definition component, as the previously mentioned Developmental Model of Sport Participation (Côté and Fraser-Thomas, 2016) suggests deliberate practice is also a key indicator of early specialization. Finally, as this review focuses on early specialization definitions were also coded depending on whether they included any information regarding an age threshold.

Definitions were extracted from all 129 articles and coded for each of the six individual components (i.e., year-round, intense training, single sport, exclusion of other sports, deliberate practice, and age threshold) of early specialization, which are presented in Table 4. Just over 20% (i.e., 20.9%, n = 27) of the articles included the initial four-component definition of early specialization. The most frequent individual component of early specialization was single sport participation (i.e., 73.6%, n = 95), while the least frequent individual component was high amounts/volume of deliberate practice at 9.3% (n = 12). Additionally, 44.2% (n = 57) included year-round training, 41.9% (n = 54) used exclusion of other sports and 31.8% (n = 41) considered intense training to be a key facet of early specialization. A particularly interesting finding was the lack of distinction between early specialization vs. sport specialization; only 30.2% (n = 39) of the papers included some mention of early or young age as part of the definition for early specialization. Finally, 17.1% (n = 22) of the 129 papers discussed and focused on early specialization yet had no explicit definition of early specialization.

While definitions lay the foundation for understanding components of early specialization, it follows that studies in turn must classify athletes according to these definitions. Further analysis was conducted on the measures used in the 48 data-driven specialization specific studies in order to better understand how researchers classified athletes as early specializers. A key step to measuring early specialization is determining what is meant by early, yet only 25 studies (52.1%) included a measure of age in their screening tool. Of those, 56% (n = 14) used “before the age of 12” as the cut-off for early specialization. To determine specialization status in the empirical studies, 18 different approaches or strategies were employed. It should be noted that while different indicators of early specialization were used, some of the constructs overlap. Fifteen (31.3%) of the 48 studies used the “Sport Specialization Scale” by Jayanthi et al. (2015), 11 (22.9%) used a single item question (e.g., “Did you specialize before high school, yes or no?”) while 10 (20.8%) collected a full developmental history of the athlete (e.g., hours in each sport, practice history, and number of sports at different ages). For a complete list of the different approaches used, see Table 5.

Early specialization is currently a “hot button” topic in athlete development research in particular and sport science more generally. Our review suggests much of the discussion in this area is driven by non-data driven, commentaries, editorials, and reviews, which undermines the extent to which recommendations about early specialization can be seen as evidence-based. Only 37% of the literature in this review included data-driven studies that were explicitly designed to advance our understanding of early specialization specifically, with 43% of the papers comprised of editorials, commentaries, or reviews. Common rhetoric around this issue assumes early specialization leads to injury, yet only 14 studies have actually examined this relationship with certain indicators of early specialization and of those only five measured early specialization. Similarly, despite broad recommendations that early specialization increases risk of burnout from sport, only three studies explicitly examined this relationship. Given the findings contained in this review, we believe there is insufficient evidence to provide the foundation for the strong and “conclusive” position statements around this topic. Importantly, there is also insufficient evidence to conclude there are no risks to early specialization. Despite messages to the contrary, the benefits and risks of early specialization remains an open topic for sport researchers.

The work summarized in this review raises important concerns about the state of the evidence against early specialization and how future research could be improved to resolve outstanding issues. The first issue relates to the conflating of “early specialization” and “sport specialization.” Most researchers would agree that the considerable training required to become an elite athlete necessitates eventual specialization at some point (Baker et al., 2003). Researchers however advised against the practice of early specialization, suggesting this leads to negative outcomes such as increased injury rates (Hall et al., 2015) without associated benefits (Baker, 2003). In the current review, only half of the studies identified measured an aspect of “early.” This distinction between “early specialization” and “specialization” is important. “Specialization” in a single sport may be associated with injury or other negative outcomes due to the link between specialization and overtraining (Ferguson and Stern, 2014) not the age at which it is occurring. Further, in order to properly study the effects of early specialization, it is important to clearly operationalize “early.” Of the few studies in this review that measured early only about half used the same criteria (i.e., before age 12).

Another issue relates to the validity of the scales or tools used to determine specialization. The most commonly used scale is Jayanthi et al.'s (2015) Sport Specialization Scale, which uses three criteria [1. single sport training, 2. exclusion of other sports, and 3. year-round training (>8 months)] to rank athletes as low (having only one of the criteria), moderate (two of three) or high on specialization (all three). Over 30% of the data- driven specialization specific studies in this review used this scale, despite concerns about the validity of this scale (Smith et al., 2017). With this scale, for example, a recreational athlete who participates once a week for 2 h in basketball, but quit soccer at age seven, would be regarded as more specialized than a competitive basketball player who participates for 6 h a week but only ever participated in basketball, despite the fact that most practitioners would be more concerned about the latter. Furthermore, 20% of studies in this review used only a single item to measure specialization, raising further concerns about whether a single item is nuanced enough to adequately capture this multi-faceted concept. As noted in the results, 18 different approaches have been used to determine specialization status often inconsistently categorizing athletes. For instance, one study compared a self-classification method (i.e., are you a single sport or multi-sport athlete) to the 3-point “Sport Specialization Scale,” resulting in only 38% agreement on the athletes' categorization and differing results on the relationships between specialization status and injury history (Bell et al., 2016).

There were also inconsistencies between the definitions of early specialization and the markers researchers used to measure it. Over half of the studies mentioned “intense” training in their definition of early specialization yet only three studies included any measure of intensity. These were unique case reports that collected a thorough background on one athlete. This misalignment between definition and method further highlights concerns with validity that mar this area of research.

These issues highlight the precarious foundation of the early specialization evidence base. Ferguson and Stern (2014) noted “All position statements are slightly different, but there is not one single position statement that supports early specialization” (p. 380)—but it is unclear why researchers have been so quick to conclude against early specialization given the lack of a consistent definition or method of classifying athletes. Also concerning is that researchers are recommending multi-sport participation in lieu of early specialization (Coté et al., 2009) without understanding the harmful mechanism behind early specialization.

Around 73% of the papers in this review agreed that single-sport participation was a key component of early specialization, yet this component of specialization alone was not found to be associated with injury history (Bell et al., 2016). The harmful mechanisms behind early specialization are undoubtedly more complex than just single-sport participation and advocating for multi-sport participation without fully understanding what aspect of early specialization is harmful may be short-sighted.

There are several important next steps for research in this area. First and most important, there needs to be a clear and consistent definition of early specialization that can be utilized across disciplines, organizations and researchers. The field will be unable to understand the potential consequences or benefits of early specialization without first establishing a clear understanding of the components and the requirements of this concept. Although it may be difficult to come to a consensus on a definition for early specialization, a Delphi-type approach (i.e., using experts' answers to questionnaires) could be a useful way to reach convergence. Experts could reflect on which previously used facets of early specialization are essential, which are less important, and which are missing. This could help the field establish a definition of early specialization that most agree with. Second, a valid and reliable scale that captures and categorizes early specializers is needed. Any future scales should include some measure of age in order to distinguish “early specialization” from “sport specialization.” Additionally, researchers may consider adding measures of intensity to the classification of early specializers to separate those who participate more recreationally from those at risk of overtraining. As noted by a previous systematic review (DiSanti and Erickson, 2019), 92.5% of studies used a dichotomy (i.e., specializer or not) to classify athletes. This likely over-simplifies a highly nuanced topic and future research should consider establishing a continuum of early specialization. Finally, there is a need for more research overall on this topic. Suggestions and statements need to be evidence-based and in order for that to happen there needs to be more evidence.

While this review provides the first comprehensive look at all papers related to early specialization in sport, it is not without limitations. First the inclusion of non-data driven studies, while important for understanding the composition of the literature, made it impossible to synthesize all papers in the review uniformly. Additionally, the range of approaches used to classify athletes also made it impractical to perform a meta-analysis. Second, the inclusion criteria that studies “explicitly use the term ‘specialization”’ might have eliminated studies that focused on the same area but used other words to describe this pattern of participation. Finally, while the search strategy was created in consultation with a profession research librarian, the search string used could have limited the number of studies found through each of the four search engines (e.g., using the connector “AND” could have excluded studies that did not include all the required search terms but were still relevant to the review).

This review has shown that there are troubling inconsistencies in the definitions of early specialization and the approaches used to classify athletes. Although this review does not directly establish a clear and consistent definition of early specialization, it is an essential first step. While practitioners and organizations advise against early specialization, this review raises significant questions around the validity and reliability of the evidence underpinning these claims. Once a consistent definition of early specialization is established and researchers have created a valid and reliable measure to capture it, the work to determine negative consequences and benefits of early specialization can begin. Until then research and any recommendations around early specialization should be viewed with caution. To understand the mechanisms behind early specialization and why it is potentially harmful or beneficial, the field must first establish what early specialization is and how best to measure it.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

AM collected the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript and designed the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^Book chapters were not included in the review as they do not undergo a rigorous peer-review process and they are not indexed the way journals are, therefore they would not show up in our four databases.

American Academy of Pediatrics (2000). Intensive training and sports specialization in young athletes. Pediatrics 106, 54–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.154

Anderson, D. I., and Mayo, A. M. (2015). A skill acquisition perspective on early specialization in sport. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 230–247. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0026

Arede, J., Esteves, P., Ferreira, A. P., Sampaio, J., and Leite, N. (2019). Jump higher, run faster: effects of diversified sport participation on talent identification and selection in youth basketball. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2220–2227. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2019.1626114

Baker, J. (2003). Early specialization in youth sport: a requirement for adult expertise? High Ability Stud. 14, 85–94. doi: 10.1080/13598130304091

Baker, J., Côté, J., and Abernethy, B. (2003). Learning from the experts: practice activities of expert decision makers in sport. Res. Q Exerc. Sport. 74, 342–347. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2003.10609101

Baker, J., Côté, J., and Deakin, J. (2005). Expertise in ultra-endurance triathletes early sport involvement, training structure, and the theory of deliberate practice. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 17, 64–78 doi: 10.1080/10413200590907577

Baker, J., Cobley, S., and Fraser-Thomas, J. (2009). What do we know about early sport specialization? Not much!. High Ability Stud. 20, 77–89. doi: 10.1080/13598130902860507

Baker, J., and Robertson-Wilson, J. (2003). On the risks of early specialization in sport. Phys. Health Educ. J. 69, 4–8.

Beese, M. E., Joy, E., Switzler, C. L., and Hicks-Little, C. A. (2015). Landing error scoring system differences between single-sport and multi-sport female high school-aged athletes. J. Athl. Train. 50, 806–811. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.7.01

Bell, D. R. (2018). Youth sport injuries and sport specialization. Athl. Train Sports Health Care 10, 239–240. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20180828-01

Bell, D. R., Lang, P. J., McLeod, T. C., McCaffrey, K. A., Zaslow, T. L., and McKay, S. D. (2018a). Sport specialization is associated with injury history in youth soccer athletes. Athl. Train Sports Health Care 10, 241–246. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20180813-01

Bell, D. R., Post, E. G., Biese, K., Bay, C., and McLeod, T. V. (2018c). Sport specialization and risk of overuse injuries: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics.142:e20180657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0657

Bell, D. R., Post, E. G., Trigsted, S. M., Hetzel, S., McGuine, T. A., and Brooks, M. A. (2016). Prevalence of sport specialization in high school athletics: a 1-yearobservational study. Am. J. Sports Med. 44, 1469–1474. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629943

Bell, D. R., Post, E. G., Trigsted, S. M., Schaefer, D. A., McGuine, T. A., Watson, A. M., et al. (2018b). Sport specialization characteristics between rural and suburban high school athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 6:2325967117751386. doi: 10.1177/2325967117751386

Black, S., Black, K., Dhawan, A., Onks, C., Seidenberg, P., and Silvis, M. (2019). Pediatric sports specialization in elite ice hockey players. Sports Health 11, 64–68. doi: 10.1177/1941738118800446

Blagrove, R. C., Bruinvels, G., and Read, P. (2017). Early sport specialization and intensive training in adolescent female athletes: risks and recommendations. Strength Cond. J. 39, 14–23. doi: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000315

Bodey, K. J., Judge, L. W., and Hoover, J. V. (2013). Specialization in youth sport: what coaches should tell parents. Strategies 26, 3–7. doi: 10.1080/08924562.2012.749160

Branta, C. F. (2010). Sport specialization: developmental and learning issues. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 19–28. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598521

Brenner, J. S. (2016). Sports specialization and intensive training in young athletes. Pediatrics 138:e20162148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2148

Bridge, M. W., and Toms, M. R. (2013). The specialising or sampling debate: a retrospective analysis of adolescent sports participation in the UK. J. Sports Sci. 31, 87–96. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.721560

Brooks, M. A., Post, E. G., Trigsted, S. M., Schaefer, D. A., Wichman, D. M., Watson, A. M., et al. (2018). Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of youth club athletes toward sport specialization and sport participation. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 6:2325967118769836. doi: 10.1177/2325967118769836

Brylinsky, J. (2010). Practice makes perfect and other curricular myths in the sport specialization debate. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 22–25. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598522

Buckley, P. S., Bishop, M., Kane, P., Ciccotti, M. C., Selverian, S., Exume, D., et al. (2017). Early single-sport specialization: a survey of 3090 high school, collegiate, and professional athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5:2325967117703944. doi: 10.1177/2325967117703944

Buhrow, C., Digmann, J., and Waldron, J. J. (2017). The relationship between sports specialization and mental toughness. Int. J. Exerc Sci. 10, 44–52.

Côté, J., and Fraser-Thomas, J. (2016). “Youth involvement and positive development in sport,” in Sport Psychology: A Canadian Perspective, 3rd Edn, ed P. R. E. Crocker (Toronto, ON: Pearson Prentice Hall), 256–287.

Côté, J., and Hancock, D. J. (2016). Evidence-based policies for youth sport programmes. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 8, 51–65. doi: 10.1080/19406940.2014.919338

Côté, J., Lidor, R., and Hackfort, D. (2009). ISSP position stand: to sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 9, 7–17. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671889

Callender, S. S. (2010). The early specialization of youth in sports. Athl. Train Sports Health Care 2, 255–257. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20101029-03

Capranica, L., and Millard-Stafford, M. L. (2011). Youth sport specialization: how to manage competition and training? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 6, 572–579. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.4.572

Carson, R. L., Landers, R. Q., and Blankenship, B. T. (2010). Concluding comments and recommendations. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 38–39. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598526

Coakley, J. (2010). The “logic” of specialization: using children for adult purposes. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 16–25. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598520

Coté, J., Horton, S., MacDonald, D., and Wilkes, S. (2009). The benefits of sampling sports during childhood. Phys. Health Educ. J. 74, 6–11.

Coutinho, P., Mesquita, I., Fonseca, A. M., and Côte, J. (2015). Expertise development in volleyball: the role of early sport activities and players' age and height. Kinesiol. Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Kinesiol. 47, 215–225.

Cupples, B., O'Connor, D., and Cobley, S. (2018). Distinct trajectories of athlete development: a retrospective analysis of professional rugby league players. J. Sports Sci. 36, 2558–2566. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1469227

DePhillipo, N. N., Cinque, M. E., Kennedy, N. I., Chahla, J., Moatshe, G., and LaPrade, R. F. (2018). Patellofemoral chondral defect in a preadolescent skier: a case report in early sport specialization. Int. J. sports Phys. Ther. 13:131. doi: 10.26603/ijspt20180131

DiCesare, C. A., Montalvo, A., Barber Foss, K. D., Thomas, S. M., Ford, K. R., Hewett, T. E., et al. (2019). Lower extremity biomechanics are altered across maturation in sport-specialized female adolescent athletes. Front. Pediatr. 7:268. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00268

DiFiori, J. P., Benjamin, H. J., Brenner, J. S., Gregory, A., Jayanthi, N., Landry, G. L., et al. (2014). Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American medical society for sports medicine. Br. J. Sports Med. 48, 287–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299

DiFiori, J. P., Brenner, J. S., Comstock, D., Côté, J., Güllich, A., Hainline, B., et al. (2017). Debunking early single sport specialisation and reshaping the youth sport experience: an NBA perspective. Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 142–143. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097170

DiSanti, J. S., and Erickson, K. (2019). Youth sport specialization: a multidisciplinary scoping systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2094–2105. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2019.1621476

DiStefano, L. J., Beltz, E. M., Root, H. J., Martinez, J. C., Houghton, A., Taranto, N., et al. (2018). Sport sampling is associated with improved landing technique in youth athletes. Sports Health 10, 160–168. doi: 10.1177/1941738117736056

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., and Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100:363. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

Fabricant, P. D., Lakomkin, N., Sugimoto, D., Tepolt, F. A., Stracciolini, A., and Kocher, M. S. (2016). Youth sports specialization and musculoskeletal injury: a systematic review of the literature. Phys. Sports Med. 44, 257–262. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2016.1177476

Federal Interagency Forum on Child Family Statistics (2020). Pop1 Child Population: Number Of Children (in Millions) Ages 0–17 in the United States By Age, 1950–2018 and Projected 2019–2050. Available online at: https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/pop1.asp (accessed March 5, 2020).

Feeley, B. T., Agel, J., and LaPrade, R. F. (2016). When is it too early for single sport specialization? Am. J. Sports Med. 44, 234–241. doi: 10.1177/0363546515576899

Ferguson, B., and Stern, P. J. (2014). A case of early sports specialization in an adolescent athlete. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 58, 377–383.

Ford, P. R., Carling, C., Garces, M., Marques, M., Miguel, C., Farrant, A., et al. (2012). The developmental activities of elite soccer players aged under-16 years from Brazil, England, France, Ghana, Mexico, Portugal and Sweden. J. Sports Sci. 30, 1653–1663. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.701762

Fransen, J., Pion, J., Vandendriessche, J., Vandorpe, B., Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., et al. (2012). Differences in physical fitness and gross motor coordination in boys aged 6–12 years specializing in one versus sampling more than one sport. J. Sports Sci. 30, 379–386. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.642808

Fraser-Thomas, J., Cote, J., and Deakin, J. (2008). Examining adolescent sport dropout and prolonged engagement from a developmental perspective. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 20, 318–333. doi: 10.1080/10413200802163549

Gallant, F., O'Loughlin, J. L., Brunet, J., Sabiston, C. M., and Bélanger, M. (2017). Childhood sports participation and adolescent sport profile. Pediatrics 140:e20171449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1449

Geisler, P. R. (2019). The complex nature of sports specialization: it can and should be personal. Athl. Train Sports Health Care 11, 3–6. doi: 10.3928/19425864-20181031-02

Ginsburg, R. D., Smith, S. R., Danforth, N., Ceranoglu, T. A., Durant, S. A., Kamin, H., et al. (2014). Patterns of specialization in professional baseball players. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 8, 261–275. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2014-0032

Gonçalves, C. E., Rama, L. M., and Figueiredo, A. B. (2012). Talent identification and specialization in sport: an overview of some unanswered questions. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 7, 390–393. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.7.4.390

Goodway, J. D., and Robinson, L. E. (2015). Developmental trajectories in early sport specialization: a case for early sampling from a physical growth and motor development perspective. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 267–278. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0028

Gould, D. (2010). Early sport specialization: a psychological perspective. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 33–37. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598525

Griffin, J. (2008). Sport psychology: myths in sport education and physical education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 79, 11–13. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2008.10598223

Güllich, A. (2014). Many roads lead to Rome–developmental paths to olympic gold in men's field hockey. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 14, 763–771. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2014.905983

Güllich, A. (2017). International medallists' and non-medallists' developmental sport activities–a matched-pairs analysis. J. Sports Sci. 35, 2281–2288. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1265662

Güllich, A., and Emrich, E. (2013). Investment patterns in the careers of elite athletes in East and West Germany. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 10, 191–214. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2013.11687919

Güllich, A., and Emrich, E. (2014). Considering long-term sustainability in the development of world class success. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 14, 383–397. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2012.706320

Hall, R., Barber Foss, K., Hewett, T. E., and Myer, G. D. (2015). Sports specialization is associated with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J. Sport Rehabil. 24, 31–35. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2013-0101

Hastie, P. A. (2015). Early sport specialization from a pedagogical perspective. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 292–303. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0029

Haugaasen, M., and Jordet, G. (2012). Developing football expertise: a football-specific research review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 5, 177–201. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2012.677951

Hendry, D. T., and Hodges, N. J. (2018). Early majority engagement pathway best defines transitions from youth to adult elite men's soccer in the UK: a three time-point retrospective and prospective study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 36, 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.009

Hill, G. M. (1993). Youth sport participation of professional baseball players. Soc. Sport J. 10, 107–114. doi: 10.1123/ssj.10.1.107

Horn, T. S. (2015). Social psychological and developmental perspectives on early sport specialization. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 248–266. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0025

Huxley, D. J., O'Connor, D., and Larkin, P. (2017). The pathway to the top: key factors and influences in the development of Australian olympic and world championship track and field athletes. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 12, 264–275. doi: 10.1177/1747954117694738

Jayanthi, N., Pinkham, C., Dugas, L., Patrick, B., and Labella, C. (2013). Sports specialization in young athletes: evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health 5, 251–257. doi: 10.1177/1941738112464626

Jayanthi, N. A., and Dugas, L. R. (2017). The risks of sports specialization in the adolescent female athlete. Strength Cond. J. 39, 20–26. doi: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000293

Jayanthi, N. A., Holt, D. B. Jr, LaBella, C. R., and Dugas, L. R. (2018). Socioeconomic factors for sports specialization and injury in youth athletes. Sports Health 10, 303–310. doi: 10.1177/1941738118778510

Jayanthi, N. A., LaBella, C. R., Fischer, D., Pasulka, J., and Dugas, L. R. (2015). Sports specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am. J. Sports Med. 43, 794–801. doi: 10.1177/0363546514567298

Kaleth, A. S., and Mikesky, A. E. (2010). Impact of early sport specialization: a physiological perspective. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 29–37. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598524

Landers, R. Q., Carson, R. L., and Blankenship, B. T. (2010). The promise and pitfalls of sport specialization in youth sport. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 14–39. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598519

Lange, D. (2019). Children's Sport Participation in England 2008-2018. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/421116/childrens-sports-involvment-england-uk/ (accessed March 5, 2020).

LaPrade, R. F., Agel, J., Baker, J., Brenner, J. S., Cordasco, F. A., Côté, J., et al. (2016). AOSSM early sports specialization consensus statement. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 4:2325967116644241. doi: 10.1177/2325967116644241

Larson, H. K., Young, B. W., McHugh, T. L., and Rodgers, W. M. (2019). Markers of early specialization and their relationships with burnout and dropout in swimming. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 41, 46–54. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2018-0305

Leite, N., Baker, J., and Sampaio, J. (2009). Paths to expertise in Portuguese National Team athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 8, 560–566.

Leite, N., Santos, S., Sampaio, J., and Gómez, M. (2013). The path to expertise in Portuguese and USA basketball players. Kinesiol. Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Kinesiol. 45, 194–202.

Leite, N. M., and Sampaio, J. E. (2012). Long-term athletic development across different age groups and gender from portuguese basketball players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 7, 285–300. doi: 10.1260/1747-9541.7.2.285

Livingston, J., Schmidt, C., and Lehman, S. (2016). Competitive club soccer: parents' assessments of children's early and later sport specialization. J. Sport Behav. 39, 301–316.

Malina, R. M. (2010). Early sport specialization: roots, effectiveness, risks. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 9, 364–371. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181fe3166

Martin, E. M., Ewing, M. E., and Oregon, E. (2017). Sport experiences of division I collegiate athletes and their perceptions of the importance of specialization. High Ability Stud. 28, 149–165. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2017.1292894

Mattson, J. M., and Richards, J. (2010). Early specialization in youth sport: a biomechanical perspective. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 81, 26–28. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2010.10598523

Matzkin, E., and Garvey, K. (2019). Youth sports specialization: does practice make perfect? NASN Sch. Nurse. 34, 100–103. doi: 10.1177/1942602X18814619

May, C. (2019). Sport Participation in Australia. Clearinghouse for Sport. Available online at: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/knowledge_base/sport_participation/community_participation/sport_participation_in_australia (accessed March 5, 2020).

McDonald, C., Deitch, J., and Bush, C. (2019). Early sports specialization in elite wrestlers. Sports Health 11, 397–401. doi: 10.1177/1941738119835180

McFadden, T., Bean, C., Fortier, M., and Post, C. (2016). Investigating the influence of youth hockey specialization on psychological needs (dis) satisfaction, mental health, and mental illness. Cogent. Psychol. 3:1157975. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2016.1157975

McGuine, T. A., Post, E. G., Hetzel, S. J., Brooks, M. A., Trigsted, S., and Bell, D. R. (2017). A prospective study on the effect of sport specialization on lower extremity injury rates in high school athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 45, 2706–2712. doi: 10.1177/0363546517710213

McLeod, T. V., Israel, M., Christino, M. A., Chung, J. S., McKay, S. D., Lang, P. J., et al. (2019). Sport participation and specialization characteristics among pediatric soccer athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 7:2325967119832399. doi: 10.1177/2325967119832399

Mendes, F. G., Nascimento, J. V., Souza, E. R., Collet, C., Milistetd, M., Côté, J., et al. (2018). Retrospective analysis of accumulated structured practice: a Bayesian multilevel analysis of elite Brazilian volleyball players. High Abil. Stud. 29, 255–269. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2018.1507901

Miller, M. M., Trapp, J. L., Post, E. G., Trigsted, S. M., McGuine, T. A., Brooks, M. A., et al. (2017). The effects of specialization and sex on anterior Y-balance performance in high school athletes. Sports Health 9, 375–382. doi: 10.1177/1941738117703400

Moesch, K., Elbe, A. M., Hauge, M. L., and Wikman, J. M. (2011). Late specialization: the key to success in centimeters, grams, or seconds (cgs) sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 21, e282–e290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01280.x

Moesch, K., Hauge, M. L., Wikman, J. M., and Elbe, A. M. (2013). Making it to the top in team sports: start later, intensify, and be determined!. J. Talent Dev. Excell. 5, 85–100.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic revs and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moseid, C. H., Myklebust, G., Fagerland, M. W., and Bahr, R. (2019). The association between early specialization and performance level with injury and illness risk in youth elite athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 29, 460–468. doi: 10.1111/sms.13338

Mostafavifar, A. M., Best, T. M., and Myer, G. D. (2013). Early sport specialisation, does it lead to long-term problems? Br. J. Sports Med. 47, 1060–1061. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092005

Myer, G. D., Jayanthi, N., DiFiori, J. P., et al. (2016). Sports specialization, part II: alternative solutions to early sport specialization in youth athletes. Sports Health 8, 5–73. doi: 10.1177/1941738115614811

Myer, G. D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J. P., Faigenbaum, A. D., Kiefer, A. W., Logerstedt, D., et al. (2015). Sport specialization, part I: does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health 7, 437–442. doi: 10.1177/1941738115598747

Noble, T. J., and Chapman, R. F. (2018). Marathon specialization in elites: a head start for Africans. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 13, 102–106. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0069

Normand, J. M., Wolfe, A., and Peak, K. (2017). A Review of early sport specialization in relation to the development of a young athlete. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sports Sci. 5, 37–42. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijkss.v.5n.2p.37

Padaki, A. S., Ahmad, C. S., Hodgins, J. L., Kovacevic, D., Lynch, T. S., and Popkin, C. A. (2017a). Quantifying parental influence on youth athlete specialization. A survey of athletes' parents. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5:2325967117729147. doi: 10.1177/2325967117729147

Padaki, A. S., Popkin, C. S., Hodgins, C. L., Kovacevic, D., Lynch, T. S., and Ahmad, C. S. (2017b). Factorsthat drive youth specialization. Sports Health 9, 532–536. doi: 10.1177/1941738117734149

Pantuosco-Hensch, L. (2006). Specialization or diversification in youth sport? Strategies 19, 21–27. doi: 10.1080/08924562.2006.10591211

Pantuosco-Hensch, L. (2010). Perceptions of collegiate student-athletes about their youth sport specialization or diversification process. J. Coach Educ. 3, 83–116. doi: 10.1123/jce.3.3.83

Pasulka, J., Jayanthi, N., McCann, A., Dugas, L. R., and LaBella, C. (2017). Specialization patterns across various youth sports and relationship to injury risk. Phys. Sports Med. 45, 344–352. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2017.1313077

Patel, T., and Jayanthi, N. (2018). Health-related quality of life of specialized versus multi-sport young athletes: a qualitative evaluation. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 12, 448–466. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2017-0031

Post, E. G., Bell, D. R., Trigsted, S. M., Pfaller, A. Y., Hetzel, S. J., Brooks, M. A., et al. (2017a). Association of competition volume, club sports, and sport specialization with sex and lower extremity injury history in high school athletes. Sports Health 9, 518–523. doi: 10.1177/1941738117714160

Post, E. G., Thein-Nissenbaum, J. M., Stiffler, M. R., Brooks, M. A., Bell, D. R., Sanfilippo, J. L., et al. (2017b). High school sport specialization patterns of current division I athletes. Sports Health 9, 148–153. doi: 10.1177/1941738116675455

Post, E. G., Trigsted, S. M., Riekena, J. W., Hetzel, S., McGuine, T. A., Brooks, M. A., et al. (2017c). The association of sport specialization and training volume with injury history in youth athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 45, 1405–1412. doi: 10.1177/0363546517690848

Read, P. J., Oliver, J. L., De Ste Croix, M. B., Myer, G. D., and Lloyd, R. S. (2016). The scientific foundations and associated injury risks of early soccer specialisation. J. Sports Sci. 34, 2295–2302. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1173221

Reider, B. (2017). Too much? Too soon? Am. J. Sports Med. 45, 1249–1251. doi: 10.1177/0363546517705349

Rugg, C., Kadoor, A., Feeley, B. T., and Pandya, N. K. (2018). The effects of playing multiple high school sports on National Basketball Association players' propensity for injury and athletic performance. Am. J. Sports Med. 46, 402–408. doi: 10.1177/0363546517738736

Russell, W., and Molina, S. (2018). A comparison of female youth sport specializers and non-specializers on sport motivation and athletic burnout. J Sport Behav. 41, 330–350.

Russell, W. D. (2014). The relationship between youth sport specialization, reasons for participation, and youth sport participation motivations: a retrospective study. J. Sport Behav. 37, 286−305.

Russell, W. D., and Limle, A. N. (2013). The relationship between youth sport specialization and involvement in sport and physical activity in young adulthood. J. Sport Behav. 36, 82–98.

Santos, S., Mateus, N., Gonçalves, B., Silva, A., Sampaio, J., and Leite, N. (2015). The influence of previous sport experiences in transfer of behaviour patterns among team sports. Revis. Psicol. Deporte 24, 89–92.

Santos, S., Mateus, N., Sampaio, J., and Leite, N. (2017). Do previous sports experiences influence the effect of an enrichment programme in basketball skills? J. Sports Sci. 35, 1759–1767. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1236206

Sieghartsleitner, R., Zuber, C., Zibung, M., and Conzelmann, A. (2018). “The early specialised bird catches the worm!”–a specialised sampling model in the development of football talents. Front. Psychol. 9:188. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00188

Sluder, J. B., Fuller, T. T., Griffin, S. G., and McCray, Z. M. (2017). Early vs. Late specialization in sport. GAHPERD J. 49, 9–15.

Smith, A. D., Alleyne, J. M., Pitsiladis, Y., Schneider, C., Kenihan, M., Constantinou, D., et al. (2017). Early sports specialization: an international perspective. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 16, 439–442. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000425

Smith, M. M. (2015). Early sport specialization: a historical perspective. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 220–229. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0024

Smucny, M., Parikh, S. N., and Pandya, N. K. (2015). Consequences of single sport specialization in the pediatric and adolescent athlete. Orthop. Clin. 46, 249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.11.004

Soberlak, P., and Cote, J. (2003). The developmental activities of elite ice hockey players. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 15, 41–49. doi: 10.1080/10413200305401

Stewart, C., and Shroyer, J. (2015). Sport specialization: a coach's role in being honest with parents. Strategies 28, 10–17. doi: 10.1080/08924562.2015.1066282

Storm, L. K., Kristoffer, H., and Krogh, C. M. (2012). Specialization pathways among elite Danish athletes: a look at the developmental model of sport participation from a cultural perspective. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 43, 199–222. doi: 10.7352/IJSP.2012.43.199

Strachan, L., Côté, J., and Deakin, J. (2009). “Specializers” versus “samplers” in youth sport: comparing experiences and outcomes. Sport Psychol. 23, 77–92. doi: 10.1123/tsp.23.1.77

Sugimoto, D., Jackson, S. S., Howell, D. R., Meehan, W. P. III., and Stracciolini, A. (2019). Association between training volume and lower extremity overuse injuries in young female athletes: implications for early sports specialization. Phys. Sports Med. 47, 199–204. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2018.1546107

Sugimoto, D., Stracciolini, A., Dawkins, C. I., Meehan, W. P. III., and Micheli, L. J. (2017). Implications for training in youth: is specialization benefiting kids?. Strength Cond. J. 39, 77–81. doi: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000289

Swindell, H. W., Marcille, M. L., Trofa, D. P., Paulino, F. E., Desai, N. N., Lynch, T. S., et al. (2019). An analysis of sports specialization in NCAA division I collegiate athletics. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 7:2325967118821179. doi: 10.1177/2325967118821179

The Aspen Institute Project Play (2019). State of Play: Trends and Developments in Youth Sport. Available online at: https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2019/10/2019_SOP_National_Final.pdf (accessed March 5, 2020).

Torres, C. R. (2015). Better early than late? A philosophical exploration of early sport specialization. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 304–316. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0020

Waldron, S., DeFreese, J. D., Register-Mihalik, J., Pietrosimone, B., and Barczak, N. (2019). The costs and benefits of early sport specialization: a critical review of literature. Quest 72, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2019.1580205

Wall, M., and Côté, J. (2007). Developmental activities that lead to dropout and investment in sport. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 12, 77–87. doi: 10.1080/17408980601060358

Walters, B. K., Read, C. R., and Estes, A. R. (2018). The effects of resistance training, overtraining, and early specialization on youth athlete injury and development. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 58, 1339–1348. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07409-6

Weiss, M. R. (2015). “Bo Knows” revisited: debating the early sport specialization question. Kinesiol. Rev. 4, 217–219. doi: 10.1123/kr.2015-0030

Wiersma, L. D. (2000). Risks and benefits of youth sport specialization: perspectives and recommendations. Pediatric Exerc. Sci. 12, 13–22. doi: 10.1123/pes.12.1.13

Wilhelm, A., Choi, C., and Deitch, J. (2017). Early sport specialization: effectiveness and risk of injury in professional baseball players. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5:2325967117728922. doi: 10.1177/2325967117728922

Williams, C. A. (2018). Elite youth sports—the year that was 2017. Pediatric Exerc. Sci. 30, 25–27. doi: 10.1123/pes.2018-0001

Keywords: early specialization, definition, sampler, review, specializer

Citation: Mosher A, Fraser-Thomas J and Baker J (2020) What Defines Early Specialization: A Systematic Review of Literature. Front. Sports Act. Living 2:596229. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2020.596229

Received: 18 August 2020; Accepted: 30 September 2020;

Published: 27 October 2020.

Edited by:

Duarte Araújo, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Arne Güllich, University of Kaiserslautern, GermanyCopyright © 2020 Mosher, Fraser-Thomas and Baker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandra Mosher, bW9zaGVyYUB5b3JrdS5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.