95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Astron. Space Sci. , 11 November 2024

Sec. Astrochemistry

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2024.1489982

This article is part of the Research Topic Chemical Diversity of Circumstellar Envelopes Around Evolved Stars View all 5 articles

Introduction: The 21

Method: In this study, we attempt to fit the 21

Results and Discussion: Based on the fitting outcomes we conclude that fulleranes can provide a more plausible explanation for the origin of 21

As a low- or intermediate-mass star progresses into the final stage of the asymptotic giant branch (AGB), its circumstellar envelope is detached from the stellar surface, and the effective temperature rises (e.g., Kwok, 1993; 2024). When the center star is sufficiently hot, the envelope is ionized, initiating the formation of a planetary nebula (PN). During the transition from the AGB to PN phases, there is a brief evolutionary phase (

Despite evolving from an AGB star’s envelope, a PPN’s infrared spectrum exhibits substantial variations with the appearance of a group of Unidentified Infrared Emission (UIE) bands at 3.3, 3.4, 6.2, 6.9, 7.7, 8.6, 11.3, and 12.7

In addition, an UIE feature at 21

Apart from inorganic compounds, complex organic molecules such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and hydrogenated fullerenes (fulleranes), could also emit at around 21

In comparison to other astrochemically relevant species, PAHs and fulleranes have certain advantages to account for the 21

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology and the data used. In Section 3 we discuss the goodness of different materials as the carrier of the 21

The Spitzer Space Telescope observed 11 sources exhibiting the 21

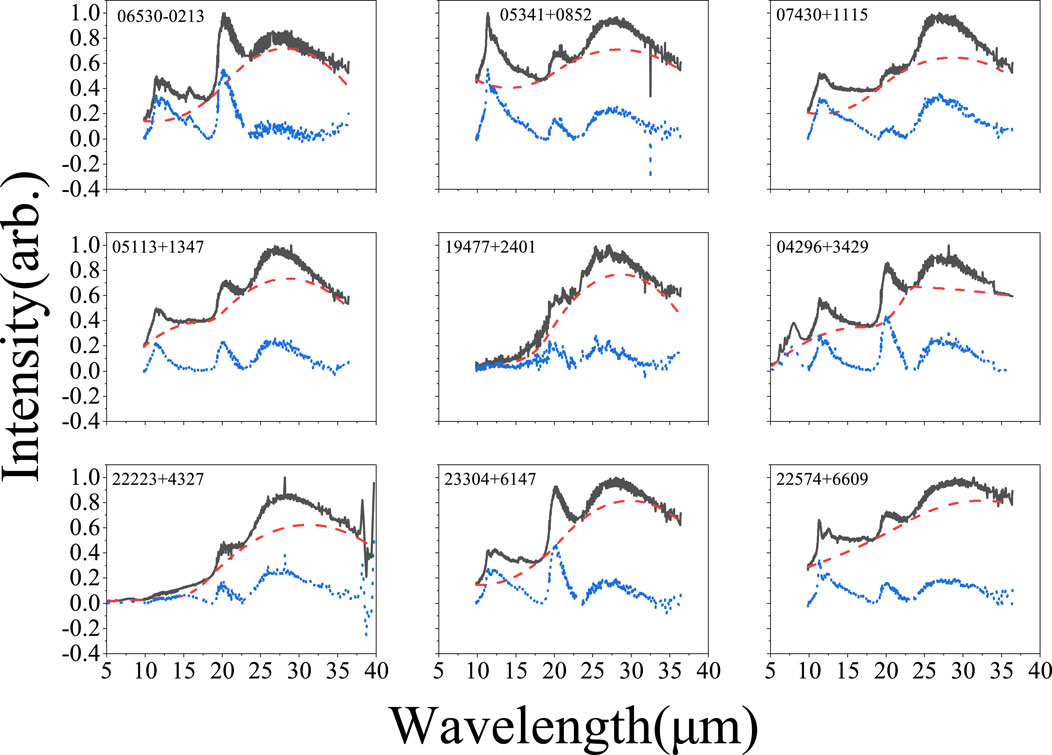

To subtract the continuum underlying the features, we selected the concave points in the spectra as anchors. A spline interpolation was utilized to construct a curve that passes through all selected anchors. Then constructed curve was subtracted from the observed spectrum for the subsequent fitting. The continuum-subtracted spectra are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Normalized Spitzer spectra of the 21

Theoretical Infrared (IR) spectra of PAH molecules calculated at density functional theory (DFT) (Parr, 1985; Mattioda et al., 2020) were obtained from the NASA Ames PAH IR Spectroscopic Database1 (PAHdb Bauschlicher et al., 2010; 2018). Among the 4000 PAH spectra in PAHdb, we chose 288 for the fitting based on the following criteria: 1) the molecules contain C, H, and N atoms only; 2) the molecules include aromatic C-H bonds that are responsible for UIE; (3) the numbers of selected small-, medium-, and large-sized PAHs (with carbon-atom number

Theoretically calculated IR spectra of 55 fulleranes (

The nine continuum-subtracted spectra were fitted by synthesizing separately the theoretical spectra of PAHs and those of fulleranes using the Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm. The steps involved were as follows.

1. Import the observational spectrum and the spectrum data matrix of PAHs/fulleranes.

2. Generate a series of random numerical sequences, each containing the same number of digits as the number of molecules in the spectrum data matrix.

3. Multiplying the spectrum data matrix with the numerical sequence, we get a series of synthesized spectra.

4. Compare the observed spectrum and the synthesized spectra, and pick up that with the minimum error.

5. Repeat the above steps until no synthesized spectrum with lower error can be found.

6. Output the synthesized spectrum and the numerical sequence given by the optimal fitting.

The goodness of the fits is evaluated quantitatively by the reduced chi-square

After the optimal fitting was obtained, we can investigate the types of PAHs and fulleranes that are mostly responsible for the 21

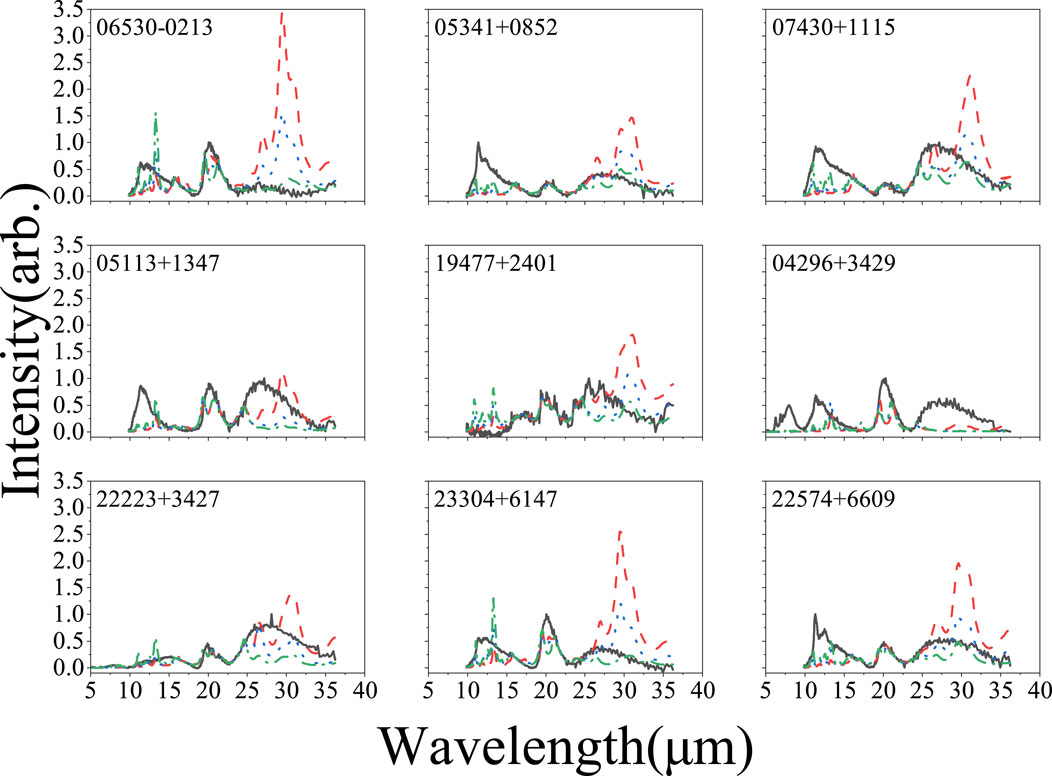

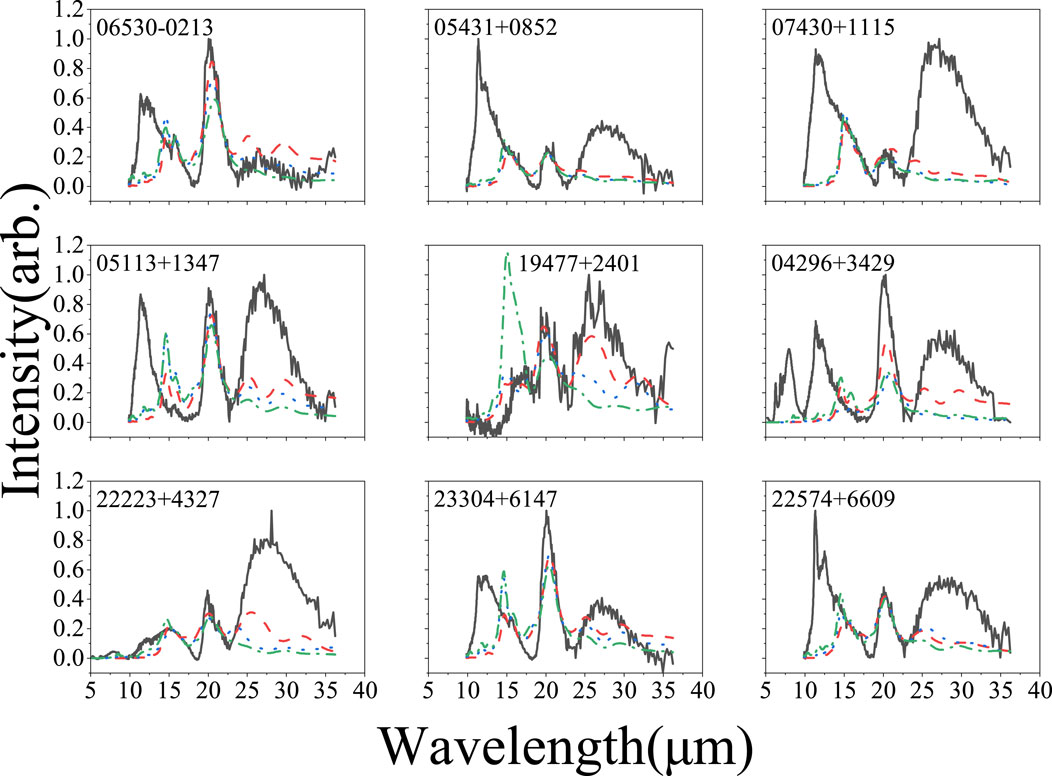

As thermal excitation has been assumed, the synthesized spectra depend on the preset temperatures. If the preset temperature was too high, in the short-wavelength regions, the synthesized spectra would exhibit too intense features to be compatible with the observations, and vice versa. To optimize the temperature adopted, we performed the fitting using a few different temperature values for PAH and fullerane spectra, as shown in Figures 2, 3 respectively. As shown in the figures, when the preset temperature is 150 K, the synthesized spectra show too strong emission bands near 12.7

Figure 2. Fitting the observed spectra (solid curves) using the theoretical spectra of PAHs at 100 K (red dashed curves), 125 K (green dotted curves), and 150 K (blue dashed-dotted curves).

Figure 3. Same as Figure 2 but for fulleranes.

The

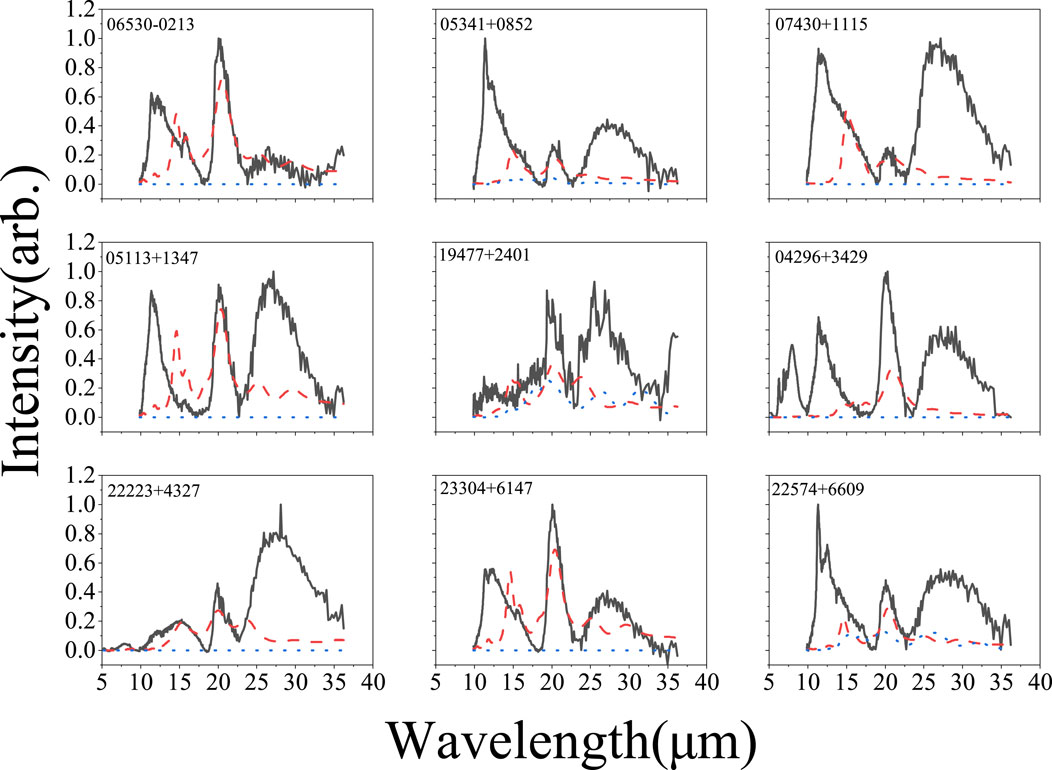

The fulleranes are divided into two groups according to their hydrogenation degree (

Figure 4. Contributions of the fulleranes with different hydrogenation to the fits. The solid curves show the observed spectra. The blue dotted and red dashed curves represent the spectra of

The binding energy of hydrogen atoms linking on fullerene surface is 3.3 eV and 1.9 eV for fulleranes with even and odd hydrogen-atom numbers, respectively (Abbink et al., 2024). The values are lower than that of ordinary H-H bonds (

The C-H streching vibration of moderately hydrogenated fullerenes may provide observable emission features around 3.4

To examine the possibility of PAHs and fulleranes as the carrier of the 21

Nevertheless, we have no means to draw firm conclusions at this moment. We hope that this work could attract research interests in fulleranes in space as collaborative efforts in observations, theories, and experiments are required.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

X-XL: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization. YZ: Investigation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation. SS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The financial supports of this work are from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 12473027, 12473027, and 12333005), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Funding (No. 2024A1515010798), and the science research grants from the China Manned Space Project (NO. CMS-CSST-2021-A09, CMS-CSST-2021-A10, etc.). This article is based upon work from COST Action CA21126 - Carbon molecular nanostructures in space (NanoSpace), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

The NASA Ames PAH IR Spectroscopic Database is gratefully acknowledged.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspas.2024.1489982/full#supplementary-material

1www.astrochemistry.org/pahdb/

Abbink, D., Foing, B., and Ehrenfreund, P. (2024). A model for the hydrogenation and charge states of fullerene C60: implications for diffuse interstellar band research. Astronomy and Astrophysics 684, A165–A175. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347478

Bauschlicher, C. W., Boersma, C., Ricca, A., Mattioda, A. L., Cami, J., Peeters, E., et al. (2010). The NASA Ames polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon infrared spectroscopic database: the computed spectra. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 189 (2), 341–351. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/189/2/341

Bauschlicher, C. W., Ricca, A., Boersma, C., and Allamandola, L. J. (2018). The NASA Ames PAH IR spectroscopic database: computational version 3.00 with updated content and the introduction of multiple scaling factors. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 234 (2), 32–41. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/aaa019

Buss Jr, R. H., Cohen, M., Tielens, A. G. G. M., Werner, M. W., Bregman, J. D., Witteborn, F. C., et al. (1990). Hydrocarbon emission features in the IR spectra of warm supergiants. Astrophysical J. 365, L23–L26. doi:10.1086/185879

Cami, J., Bernard-Salas, J., Peeters, E., and Malek, S. E. (2010). Detection of C 60 and C 70 in a young planetary nebula. Science 329 (5996), 1180–1182. doi:10.1126/science.1192035

Cataldo, F. (2003). Fullerane, the hydrogenated C60Fullerene: properties and astrochemical considerations. Fullerenes, Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 11 (4), 295–316. doi:10.1081/FST-120025852

Cataldo, F., and Iglesias-Groth, S. (2009). On the action of UV photons on hydrogenated fulleranes C60H36and C60D36. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 400 (1), 291–298. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15457.x

Cerrigone, L., Hora, J. L., Umana, G., Trigilio, C., Hart, A., and Fazio, G. (2011). Identification of three new protoplanetary nebulae exhibiting the unidentified feature at 21 m. Astrophysical J. 738 (2), 121–129. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/738/2/121

Díaz-Luis, J. J., García-Hernández, D. A., Manchado, A., and Cataldo, F. (2016). A search for hydrogenated fullerenes in fullerene-containing planetary nebulae. Astronomy Astrophysics 589, 5–11. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527727

Duley, W. W., and Williams, D. A. (1981). The infrared spectrum of interstellar dust: surface functional groups on carbon. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 196 (2), 269–274. doi:10.1093/mnras/196.2.269

Evans, A., van Loon, J. T., Woodward, C. E., Gehrz, R. D., Clayton, G. C., Helton, L. A., et al. (2012). Solid-phase in the peculiar binary XX Oph? Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. Lett. 421 (1), L92–L96. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2012.01213.x

García-Hernández, D. A., Iglesias-Groth, S., Acosta-Pulido, J. A., Manchado, A., García-Lario, P., Stanghellini, L., et al. (2011a). The formation of fullerenes: clues from new c 60, c 70, and (possible) planar c 24 detections in magellanic cloud planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. Lett. 737 (2), L30–L37. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/737/2/L30

García-Hernández, D. A., Manchado, A., García-Lario, P., Stanghellini, L., Villaver, E., Shaw, R. A., et al. (2010). Formation of fullerenes in H-containing planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. Lett. 724 (1), L39–L43. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/724/1/L39

García-Hernández, D. A., Rao, N. K., and Lambert, D. L. (2011b). Are C molecules detectable in circumstellar shells of R Coronae Borealis stars? Astrophysical J. 729 (2), 126–131. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/729/2/126

García-Lario, P., Manchado, A., Ulla, A., and Manteiga, M. (1999). Infrared space observatory observations of IRAS 16594–4656: a new Proto-planetary nebula with a strong 21 micron dust feature. Astrophysical J. 513 (2), 941–946. doi:10.1086/306895

Gehrz, R. D., Roellig, T. L., Werner, M. W., Fazio, G. G., Houck, J. R., Low, F. J., et al. (2007). The NASA Spitzer space telescope. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78 (1), 011302. doi:10.1063/1.2431313

Gielen, C., Cami, J., Bouwman, J., Peeters, E., and Min, M. (2011). Carbonaceous molecules in the oxygen-rich circumstellar environment of binary post-AGB stars: C60fullerenes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Astronomy and Astrophysics 536, A54–A62. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117961

Gładkowski, M., Szczerba, R., Sloan, G. C., Lagadec, E., and Volk, K. (2019). 30-micron sources in galaxies with different metallicities. Astronomy and Astrophysics 626, A92–A126. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833920

Glassgold, A. E., and Huggins, P. J. (1983). Atomic and molecular hydrogen in the circumstellar envelopes of late-type stars. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 203, 517–532. doi:10.1093/mnras/203.2.517

Hrivnak, B. J., Volk, K., and Kwok, S. (2000). 2-45 micron infrared spectroscopy of carbon-rich proto-planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 535 (1), 275–292. doi:10.1086/308823

Hrivnak, B. J., Volk, K., and Kwok, S. (2009). A Spitzer study of 21 and 30m emission in several galactic carbon-rich protoplanetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 694 (2), 1147–1160. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/1147

Iglesias-Groth, S., García-Hernández, D. A., Cataldo, F., and Manchado, A. (2012). Infrared spectroscopy of hydrogenated fullerenes (fulleranes) at extreme temperatures. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 423 (3), 2868–2878. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21097.x

Jensen, F. (2001). Polarization consistent basis sets: principles. J. Chem. Phys. 115 (20), 9113–9125. doi:10.1063/1.1413524

Jensen, F. (2002). Polarization consistent basis sets. II. Estimating the Kohn–Sham basis set limit. J. Chem. Phys. 116 (17), 7372–7379. doi:10.1063/1.1465405

Kabo, G. J., Karpushenkava, L. S., and Paulechka, Y. U. (2010). “Thermodynamic properties of fullerene hydrides C and equilibria,” in Fullerane: the hydrogenated fullerenes. Editors F. Cataldo, and S. Iglesias-Groth, 55–83.

Kwok, S., (1993). Proto-planetary nebulae. In Symp. - int. Astron. Union, symposium-international astronomical union. 155, 263–270. doi:10.1017/s0074180900170998Cambridge University Press

Kwok, S. (2004). The synthesis of organic and inorganic compounds in evolved stars. Nature 430 (7003), 985–991. doi:10.1038/nature02862

Kwok, S. (2024). Planetary nebulae research: past, present, and future. Galaxies 12 (4), 39–57. doi:10.3390/galaxies12040039

Kwok, S., Volk, K., and Bernath, P. (2001). On the origin of infrared plateau features in proto-planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 554 (1), L87–L90. doi:10.1086/320913

Kwok, S., Volk, K. M., and Hrivnak, B. J. (1989). A 21 micron emission feature in four proto-planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 345 (Oct. 1), L51–L54. doi:10.1086/185550

Li, A., Liu, J. M., and Jiang, B. W. (2013). On iron monoxide nanoparticles as a carrier of the mysterious 21 m emission feature in post-asymptotic giant branch stars. Astrophysical J. 777 (2), 111–117. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/777/2/111

Matsuura, M., Bernard-Salas, J., Lloyd Evans, T., Volk, K. M., Hrivnak, B. J., Sloan, G. C., et al. (2014). Spitzer Space Telescope spectra of post-AGB stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud–polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at low metallicities. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 439 (2), 1472–1493. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt2495

Mattioda, A. L., Hudgins, D. M., Boersma, C., Bauschlicher, C. W., Ricca, A., Cami, J., et al. (2020). The NASA Ames PAH IR spectroscopic database: the laboratory spectra. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 251 (2), 22–37. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/abc2c8

Neugebauer, G., Habing, H. J., Van Duinen, R., Aumann, H. H., Baud, B., Beichman, C. A., et al. (1984). The infrared astronomical satellite (IRAS) mission. Astrophysical J. 278 (March 1), L1–L6. doi:10.1086/184209

Otsuka, M., Kemper, F., Hyung, S., Sargent, B. A., Meixner, M., Tajitsu, A., et al. (2013). The detection of C in the well-characterized planetary nebula M1-11. Astrophysical J. 764 (1), 77–96. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/764/1/77

Palotás, J., Martens, J., Berden, G., and Oomens, J. (2020). The infrared spectrum of protonated buckminsterfullerene C60H+. Nat. Astron. 4 (3), 240–245. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0941-6

Papoular, R. (2011). Candidate carriers and synthetic spectra of the 21- and 30m proto-planetary nebular bands. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 415, 494–502. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18724.x

Parr, R. G. (1985). “Density functional theory in Chemistry,” in Density functional methods in physics (Boston, MA: Springer US), 141–158.

Roberts, K. R., Smith, K. T., and Sarre, P. J. (2012). Detection of C60 in embedded young stellar objects, a Herbig Ae/Be star and an unusual post-asymptotic giant branch star: C60 in young stellar and other objects. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 421 (4), 3277–3285. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20552.x

Rosenberg, M. J. F., Berné, O., and Boersma, C. (2014). Random mixtures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon spectra match interstellar infrared emission. Astronomy Astrophysics 566, L4–L10. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423953

Rüchardt, C., Gerst, M., Ebenhoch, J., Campbell, E. E., Tellgmann, R., Schwarz, H., et al. (1993). Transfer hydrogenation and deuteration of buckminsterfullerene C60 by 9,10-dihydroanthracene and 9,9′,10,10′[D4]Dihydroanthracene. Angew. Chemie-International Ed. 32 (4), 584–586. doi:10.1002/anie.199305841

Sadjadi, S. A., and Parker, Q. A. (2021). It remains a cage: ionization tolerance of C60 fullerene in planetary nebulae. FNCN 29, 620–625. doi:10.1080/1536383x.2021.1876677

Sellgren, K., Werner, M. W., Ingalls, J. G., Smith, J. D. T., Carleton, T. M., and Joblin, C. (2010). C 60 IN REFLECTION NEBULAE. Astrophysical J. Lett. 722 (1), L54–L57. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/722/1/L54

Tielens, A. G. G. M. (2008). Interstellar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules. Annu. Rev. Astronomy Astrophysics 46, 289–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.46.060407.145211

Van Winckel, H. (2003). Post-AGB stars. Annu. Rev. Astronomy Astrophysics 41 (1), 391–427. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.41.071601.170018

Volk, K., Hrivnak, B. J., Matsuura, M., Bernard-Salas, J., Szczerba, R., Sloan, G. C., et al. (2011). Discovery and analysis of 21 m feature sources in the magellanic clouds. Astrophysical J. 735 (2), 127–154. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/735/2/127

Volk, K., Sloan, G. C., and Kraemer, K. E. (2020). The 21 m and 30 m emission features in carbon-rich objects. Astrophysics Space Sci. 365, 88–25. doi:10.1007/s10509-020-03798-2

Volk, K. M., and Kwok, S. (1989). Evolution of protoplanetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 342 (July 1), 345–363. doi:10.1086/167597

Webster, A. (1995). The lowest of the strongly infrared-active vibrations of the fulleranes and astronomical emission band at a wavelength of 21m. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 277 (4), 1555–1566. doi:10.1093/mnras/277.4.1555

Zhang, K., Jiang, B. W., and Li, A. (2009). On the carriers of the 21m emission feature in post-asymptotic giant branch stars. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 396, 1247–1256. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14808.x

Zhang, Y. (2020). Are fulleranes responsible for the 21 micron feature? Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 33, 101–106. doi:10.1063/1674-0068/cjcp1911203

Zhang, Y., and Kwok, S. (2011). DETECTION OF C60IN THE PROTOPLANETARY NEBULA IRAS 01005+7910. Astrophysical J. 730 (2), 126–130. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/730/2/126

Zhang, Y., and Kwok, S. (2015). On the viability of the PAH model as an explanation of the unidentified infrared emission features. Astrophysical J. 798 (1), 37–42. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/798/1/37

Zhang, Y., Kwok, S., and Hrivnak, B. J. (2010). A spitzer/infrared spectrograph spectral study of a sample of galactic carbon-rich proto-planetary nebulae. Astrophysical J. 725 (1), 990–1001. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/725/1/990

Zhang, Y., Sadjadi, S., and Hsia, C. H. (2020). Hydrogenated fullerenes (fulleranes) in space. Astrophysics Space Sci. 365 (4), 67–74. doi:10.1007/s10509-020-03779-5

Keywords: infrared, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fullerenes, fulleranes, protoplanetary nebulae, astrochemistry

Citation: Liao X-X, Zhang Y and Sadjadi S (2024) Exploring the possibility of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fulleranes as the carrier of the 21 micron emission feature. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 11:1489982. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2024.1489982

Received: 02 September 2024; Accepted: 25 September 2024;

Published: 11 November 2024.

Edited by:

Ryszard Szczerba, Polish Academy of Sciences, PolandReviewed by:

Franco Cataldo, Actinium Chemical Research Institute, ItalyCopyright © 2024 Liao, Zhang and Sadjadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Zhang, emhhbmd5b25nNUBtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.