- Department of Sociology, HeDeRa (Health and Demographic Research), Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Introduction: Previous studies have identified socioeconomic inequalities in the treatment of depression. However, these studies often take a narrow approach, focusing on a single treatment type and lacking a comprehensive theoretical framework. Moreover, income and education are frequently used interchangeably as indicators of disadvantage, without distinguishing their unique impacts. This study argues that relying solely on income to explain treatment inequalities is overly simplistic, suggesting instead that education influences treatment through two distinct pathways. The study’s objectives are twofold: first, to investigate the presence of a social gradient in depression treatment, and second, to examine how this gradient is manifested.

Methods: This study utilizes data from the Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS), covering four successive waves: 2004, 2008, 2013, and 2018. The weighted data represent a sample of the adult Belgian population. Multinomial regression models are used to address the research aims, and models are plotted to detect trends over time using marginal means post-estimation.

Results: Findings indicate that income is not significantly related to depression treatment, while persistent educational inequalities in treatment are observed over time. Individuals with longer educational attainment are more likely to use psychotherapy alone or a combination treatment, whereas individuals with shorter educational attainment are more likely to use pharmaceutical treatment alone.

Discussion: This study demonstrates that education plays a critical role in fostering health-related knowledge and reasoning, making individuals with longer education more likely to engage in rational health behaviors and choose more effective treatments, even when these treatments require more effort and competencies. The findings underscore the importance of considering education as a key determinant of depression treatment inequalities.

Introduction

Depression prevalence and treatment

Depression, characterized by persistent sadness and lack of interest or pleasure, affects individuals worldwide (Marcus et al., 2012). It encompasses emotional, cognitive, and somatic symptoms and significantly impairs functioning. Data from 2018 reveal that nearly 1 in 10 Belgians experienced depressive symptoms, with more than half meeting criteria for severe depression (Gisle et al., 2018). Depression prevalence is subject to disparities influenced primarily by socioeconomic factors (World Health Organization, 2014). In Belgium, individuals in disadvantaged socioeconomic positions report depressive symptoms more frequently than those in more advantaged positions (Gisle et al., 2018), aligning with prior research that indicates a social gradient in depression prevalence (Hirschfeld and Cross, 1982; Kessler and Bromet, 2013; Lorant et al., 2003; Lund et al., 2010; Perry, 1996).

The primary treatments for depression include psychotherapy and pharmaceutical interventions (Karyotaki et al., 2014). These approaches stem from distinct theoretical perspectives on the origins of depression, with the biomedical perspective historically dominating mental health care. However, recognition of psychotherapy’s importance in treating depression has grown (Cuijpers et al., 2020; Kamenov et al., 2017; Spijker et al., 2013). In 2014, the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre conducted a meta-analysis of international scientific literature on the effectiveness of psychotherapy, concluding that psychotherapy alone or combined with antidepressants is preferable depending on depression severity (Karyotaki et al., 2014; Karyotaki et al., 2016). For severe depression, combination treatment is recommended (Cuijpers et al., 2020; Davey and Chanen, 2016; Driessen et al., 2020; van Bronswijk et al., 2019).

Inequalities in depression treatment

Research indicates that socioeconomic position is linked not only to depression prevalence but also to disparities in depression treatment. However, existing studies primarily focus on pharmaceutical interventions. For instance, uninsured individuals in the United States, often from lower-income groups, are less likely to receive antidepressant treatments (Olfson and Marcus, 2009). Conversely, studies from Denmark show that lower-income individuals have a higher prevalence of antidepressant treatment (Andersen et al., 2009; Hansen et al., 2004). Similarly, Finnish research indicates that individuals with shorter educational backgrounds are more likely to access older antidepressants with more side effects, while those with longer education are more likely to receive newer antidepressant medications (Halonen et al., 2018).

Disparities in psychotherapy treatment are less explored. Research indicates that individuals with shorter educational attainment have a reduced probability of receiving outpatient psychotherapy in Germany (Albani et al., 2010). Similar associations between shorter education and decreased access to psychotherapy have been observed in studies from France and Finland (Briffault et al., 2008; Suoyrjö et al., 2007).

However, these studies lack a comparative analysis of the associations between socioeconomic position and various types of depression treatment. Addressing disparities in one form of treatment necessitates considering inequalities in others. Furthermore, these studies are often descriptive and lack strong theoretical foundations. Socioeconomic indicators, such as income and education, are frequently used without adequately distinguishing their roles in generating and sustaining social inequality. Therefore, the objective of this study is to examine the existence of a social gradient in the choice of depression treatment and to analyze the ways in which this gradient becomes evident.

Theoretical approaches

Inequalities in depression treatment from an income-related perspective often focus on individuals’ financial resources (Mojtabai, 2009; Veugelers and Yip, 2003). Limited financial means may hinder access to costly mental health services, leading to restricted treatment options (Loef et al., 2021; Veugelers and Yip, 2003). Although treatment costs may play a role, attributing treatment inequalities solely to income is overly simplistic.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of treatment inequalities, the role of education must also be considered. Over recent decades, education has emerged as a key socioeconomic indicator in health research for several reasons (Shavers, 2007; Winkleby et al., 1992). Unlike income, education is typically established during early adulthood and maintains a high level of stability. It is usually acquired earlier in the life course and partially contributes to an individual’s income level. Furthermore, the causal relationship between education and health is less susceptible to reverse causality compared to the link between income and health. Empirical evidence consistently points to education as the most potent and reliable socioeconomic predictor of health outcomes.

Two pathways highlight education’s influence on treatment considerations. One pathway emphasizes education as a mechanism of allocation within the labor market (Mirowsky and Ross, 2005), where longer education is linked to improved employment prospects and conditions. This mechanism has intensified alongside the expansion of education and the increasing credentialization of society (Baker, 2014; Baker, 2011; Schofer and Meyer, 2005). Better job prospects and working conditions, in turn, shape the decision-making process regarding treatment choices.

The second pathway emphasizes education as a socialization mechanism. Here, education itself plays a significant role in shaping treatment choices. Socialization mechanisms are central to the theory of learned effectiveness (Mirowsky and Ross, 2005), which represents the health sociological interpretation of the human capital approach proposed by Becker (1964). According to this perspective, education fosters the development of intangible resources, such as knowledge, social competence, and “lifestyles” (Mirowsky and Ross, 2005), that could potentially influence treatment decisions. Furthermore, a cumulative effect may occur when individuals with longer educational trajectories find themselves in occupations that further enhance their higher levels of effectiveness.

Both pathways assume a causal link between education and health; however, spurious factors can also influence this relationship. The connection between education and health may be driven by shared characteristics that impact both educational attainment and health outcomes (Cutler and Lleras-Muney, 2006; Montez and Friedman, 2015). For example, “social background” is an influential factor, with higher socioeconomic position correlating with educational attainment (Kloosterman et al., 2009; Müller and Karle, 1993; Pfeffer, 2008) as well as better health outcomes (Kestilä et al., 2006). Nonetheless, amidst these confounding influences, a portion of the education-health association is likely causal.

The fundamental cause theory suggests that socialization mechanisms contribute to treatment inequalities (Link and Phelan, 1995, 2010). Individuals with longer education levels are better able to choose effective treatments, irrespective of costs. Additionally, diffusion of innovation theory posits that educated individuals are more likely to adopt new and effective therapies, which may further contribute to inequalities (Rogers, 2003).

However, the consideration extends beyond the mere effectiveness of treatments; the complexity of treatments also holds significance (Link and Phelan, 1995, 2010). Certain treatments require sustained effort and complex actions, and individuals with advanced education tend to be more inclined to undertake treatments that require greater commitment (e.g., long-term psychotherapy) and competencies (psychotherapy is linguistic and demands sustained effort). Moreover, the rise of new therapies initially leads to an increase in inequality, which may later decrease. The more complex the new therapy, the greater its impact on inequality (Clouston and Link, 2021).

Health capital approaches to treatment inequalities align with the hierarchical relationships assumed by the aforementioned theories. However, they introduce two-way interactions within the diffusion process of innovations, such as new therapies. These approaches recognize that resources for adopting innovations are derived from past experiences and habitual actions (Shim, 2010). The concept of “cultural health capital” resembles self-efficacy and health literacy, adding to the complexity narrative. Health-literate individuals, particularly in psychotherapy, facilitate effective communication and tailored treatment, equipping them with resources that provide material benefits in care. Health care providers may perceive these skills as indicators of motivation and competence, potentially leading to more favorable responses. Such skills can initiate sequences of interactions, including improved information sharing and comprehensive responses to enhance communication and care.

In summary, while the fundamental cause theory and diffusion research emphasize resources and agency, structural influences on diffusion are also crucial (Freese and Lutfey, 2011). Recognizing cultural health capital, individuals are not merely strategic agents but are also shaped by habitus. In this view, the use of health-promoting resources, like depression treatments, is not always exclusively purpose-driven. Instead, the accumulation and mobilization of resources result from past experiences and deeply ingrained, habitual ways of thinking and organizing actions (Clouston and Link, 2021).

Belgium’s institutional context

As highlighted by Freese and Lutfey (2011), the role of structural constraints in influencing treatment diffusion is crucial. Therefore, inequalities in depression treatment cannot be fully understood without considering the institutional context. An example is Belgium’s mental health care organization and reimbursement structure, which has traditionally been characterized by a biomedical orientation. Until 2016, psychiatrists were the only recognized specialists in mental health (Kohn et al., 2016). Individuals in Belgium seeking help for mental health concerns were largely unaware of alternative mental health professionals outside of general practitioners (GPs) and psychiatrists. Although clinical psychologists received official recognition in September 2016, legal provisions for psychotherapy reimbursement were lacking, and only limited reimbursement was offered by various health insurance funds, contingent on specific conditions (Ector, 2016). More recent policy changes, enacted in March 2019 and September 2021, allowed the Belgian Health Insurance to begin partially reimbursing consultations with private psychologists (Mistiaen et al., 2019; Van Maldegem, 2021).

In many countries, systems are in place to ensure affordable access to psychotherapy, often through professional associations or cooperatives with a social focus. In Belgium, however, access to affordable psychotherapy has historically been limited. Additional support structures exist, such as increased allowances for lower-income individuals, which provide higher reimbursement rates, and community health centers, which offer accessible mental health care within certain regions (Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte-en Invaliditeitsverzekering, n.d.). Nevertheless, coverage remains partial, and recent reimbursement policies for private psychologists aim to bridge this gap further (Mistiaen et al., 2019; Van Maldegem, 2021). In contrast, considerable funds are allocated for the provision of affordable antidepressants. Data on medication spending indicate that antidepressants constitute a significant portion of mental health expenditures in Belgium (Casteels et al., 2010), reflecting the greater reimbursement coverage by the Belgian Health Insurance for pharmaceutical treatments (Mistiaen et al., 2019).

However, an increasing focus on pro-therapeutic policies has emerged to address the high prescription rates and widespread use of pharmaceutical treatments. Over the past decade, Belgian research has consistently underscored the significant role of GPs in prescribing antidepressants (Boffin et al., 2012; Fraeyman et al., 2012). In response, measures have been implemented to raise GPs’ awareness of their prescribing practices, including updated guidelines for adult depression treatment (Vandekerckhove, 2016), aimed at reducing antidepressant prescriptions (Declercq et al., 2017).

Moreover, GPs may exhibit varied approaches in treating individuals with depression, influenced by patients’ socioeconomic position (Balsa and McGuire, 2003; Hyde et al., 2005; Willems et al., 2005). Qualitative research, for instance, reveals that GPs frequently adapt their clinical management strategies based on patients’ socioeconomic circumstances, aiming to provide care that is cost-effective, practical, and attainable (Bernheim et al., 2008; Hyde et al., 2005). Disparities in GP-patient interactions have also emerged, with patients in more disadvantaged socioeconomic positions being more likely to receive pharmaceutical treatments. This reflects perceptions that these patients possess not only limited financial resources but also diminished social-cognitive capacities for engaging in more “active treatments” (Butterworth et al., 2013; Fraeyman et al., 2012). Previous research has also suggested that differential patient preferences, reinforced by GPs, may contribute to treatment disparities. For instance, one study hypothesized that patients with higher levels of education are more assertive in seeking non-pharmacological treatment options and that GPs are more likely to support these preferences (Hyde et al., 2005).

Hypotheses

Based on the aforementioned theoretical approaches, we propose the existence of a social gradient in depression treatment. Specifically, we hypothesize that individuals with shorter educational attainment are more likely to opt solely for pharmaceutical treatment and less likely to choose psychotherapy or a combination treatment. This trend is expected to be only partially attributable to their lower income level. Conversely, we hypothesize that individuals with longer educational attainment are more inclined to select either psychotherapy alone or a combination treatment, with a lower likelihood of opting for pharmaceutical treatment alone, independent of their income level. Recognizing the evolving nature of this issue, the study incorporates time trends to analyze changes in depression treatment patterns and associated inequalities over time.

Methods

Sample

Data were obtained from the Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS), a repeated cross-sectional survey coordinated by Sciensano. Four successive waves are included: 2004, 2008, 2013, and 2018. Households and their members were selected from the National Register using a multi-stage stratified sampling procedure. Information was collected through face-to-face interviews and a self-administered questionnaire. This study includes 2,298 Belgian respondents over the age of 25 who reported depression complaints in the 12 months prior to data collection. Details on respondent selection criteria and data cleaning procedures are provided in Appendix 1.

Variables

Appendix 2 contains a table presenting univariate statistics for the variables used.

The dependent variable assesses the type of treatment respondents pursued in the context of self-reported depression complaints over the past 12 months. This variable includes four categories: 1 = pharmaceutical treatment (use of antidepressants for depression in the past 12 months), 2 = psychotherapy treatment (use of psychotherapy for depression in the past 12 months), 3 = combination treatment (use of both antidepressants and psychotherapy for depression in the past 12 months), and 4 = no treatment.

The independent variable, education, is assessed based on the highest level of education achieved and classified into three groups according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) of 2011 (UNESCO, 2012): 1 = shorter education (pre-primary or primary education), 2 = intermediate education (lower-and upper-secondary education), and 3 = longer education (post-secondary or tertiary education) [ref. cat.].1

The mediator variable, household income, is presented in quintiles to reflect income distributions within Belgium. This variable includes four categories: 1 = low household income (1st and 2nd quintiles) [ref. cat.], 2 = median household income (3rd and 4th quintiles), 3 = high household income (5th quintile), and 4 = missing data. Missing data are included as a separate category due to 12.3% missing responses.

Several covariates are also included, such as gender, age, nationality, urbanization, region, survey wave, GP contact in the past 12 months, regular GP status, frequency of social contact, and household composition. Gender (0 = female) and nationality (0 = Belgian) are binary variables. Age is grouped into three categories: 1 = 25–44 years [ref. cat.], 2 = 45–64 years, and 3 = 65+ years. Region is categorized as 1 = Flanders [ref. cat.], 2 = Brussels, and 3 = Wallonia. Urbanization levels are divided into 1 = cities/agglomerates [ref. cat.], 2 = urban/suburban, and 3 = rural. Wave is represented as a categorical variable: 1 = 2004 [ref. cat.], 2 = 2008, 3 = 2013, and 4 = 2018. GP contact in the past 12 months (0 = no) and regular GP status (0 = no) are binary variables. Frequency of social contact has three categories: 1 = less than once a week [ref. cat.], 2 = more than once a week, and 3 = missing data. Household composition is classified as 1 = single or single-parent household [ref. cat.], 2 = couple with or without children, and 3 = other household composition.

Statistical procedure

Prevalence rates of depression treatment are reported using weighted proportions and stratified by education, household income, and survey wave. Following bivariate statistical analyses, two multinomial regression models are tested, estimating relative risk ratios (RRRs) and their corresponding p-values. In the first model, education and the covariates are included; in the second model, both education and household income are included along with the covariates. Both multinomial regression models compare each treatment category against the reference category—pharmaceutical treatment, which is the most commonly followed treatment. For each of the two models, treatment categories are also plotted (using marginal means post-estimation) to detect trends over time. Analyses are weighted to adjust for survey sampling and non-participation bias and are conducted using SPSS 28 and STATA 15.

Results

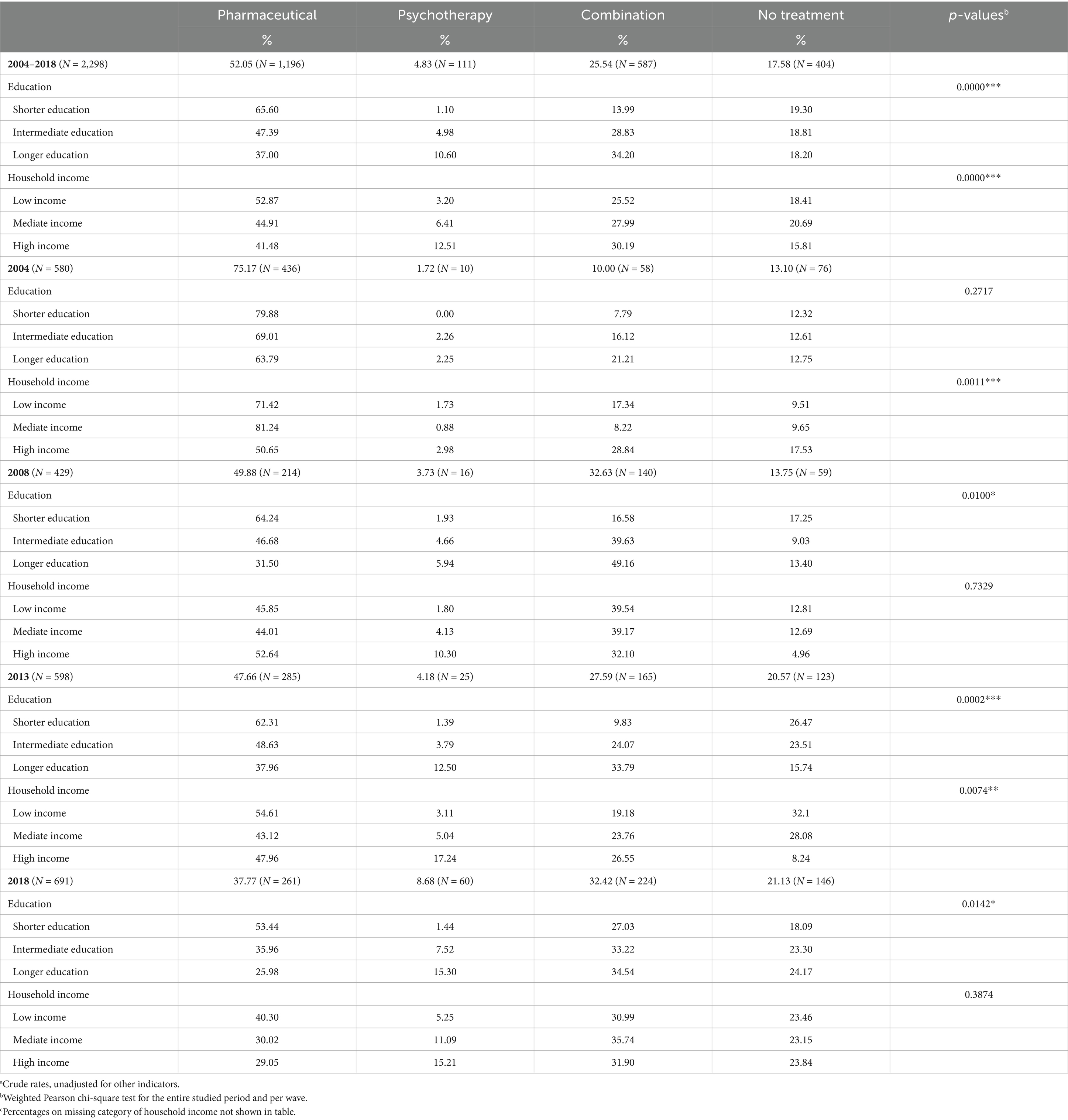

Bivariate results (see Table 1) reveal that, across waves, the predominant treatment choice remains pharmaceutical treatment alone (52.0%), followed by combination treatment (25.5%) and psychotherapy alone (4.8%). Additionally, a notable portion of individuals opts for no treatment (17.6%). Educational disparities in treatment preferences are evident: individuals with shorter educational attainment (65.6%) tend to favor pharmaceutical treatment more than those with intermediate (47.4%) or longer education (37.0%). Conversely, individuals with longer education show a greater preference for psychotherapy (10.6%) and combination treatment (34.2%). Similar but less pronounced patterns are observed across household income groups. Individuals with lower income (52.9%) are more likely to choose pharmaceutical treatment than those with medium (44.9%) or higher income (41.5%). Additionally, those with higher income (12.5%) show a greater inclination toward psychotherapy. However, the impact of income differences on combination treatment is modest.

Table 1. Weighted proportionsa of treatment for self-reported depression in the past 12 months, stratified by wave, education and household incomec.

Over time, the exclusive use of pharmaceutical treatment has consistently declined (2004 = 75.2%; 2018 = 37.8%), while the adoption of combination (2004 = 10.0%; 2018 = 23.3%) and psychotherapy treatments (2004 = 1.7%; 2018 = 8.7%) has increased. However, even in the latest wave, psychotherapy alone remains relatively low. The proportion of individuals not seeking treatment has also grown over time (2004 = 13.1%; 2018 = 21.1%). Educational and income disparities in treatment persist across waves.

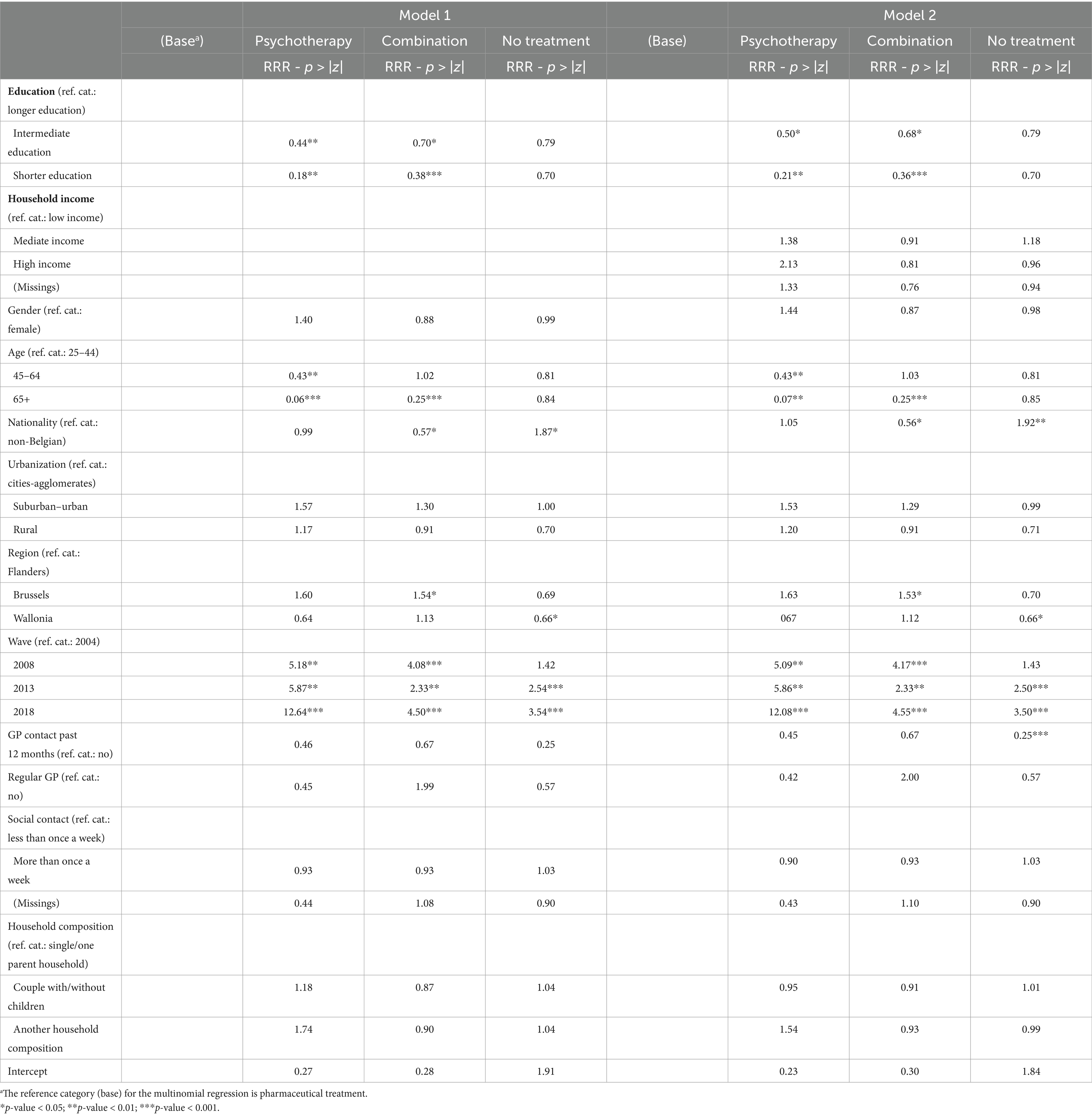

Multinomial regression results from the first model (see Table 2) show a significant association between education and depression treatment choices. Specifically, individuals with shorter (RRR = 0.18, p < 0.01) or intermediate education (RRR = 0.44, p < 0.01) are less likely than those with longer education to choose psychotherapy over pharmaceutical treatment. This pattern is also observed in combination treatment (shorter education = 0.38, p < 0.001; intermediate education = 0.70, p < 0.05). No significant educational differences are evident for individuals who opt not to seek treatment (shorter education = 0.70, p > 0.05; intermediate education = 0.79, p > 0.05).

Table 2. Weighted RRRs and p-values of treatment for self-reported depression in the past 12 months by education, household income, and covariates.

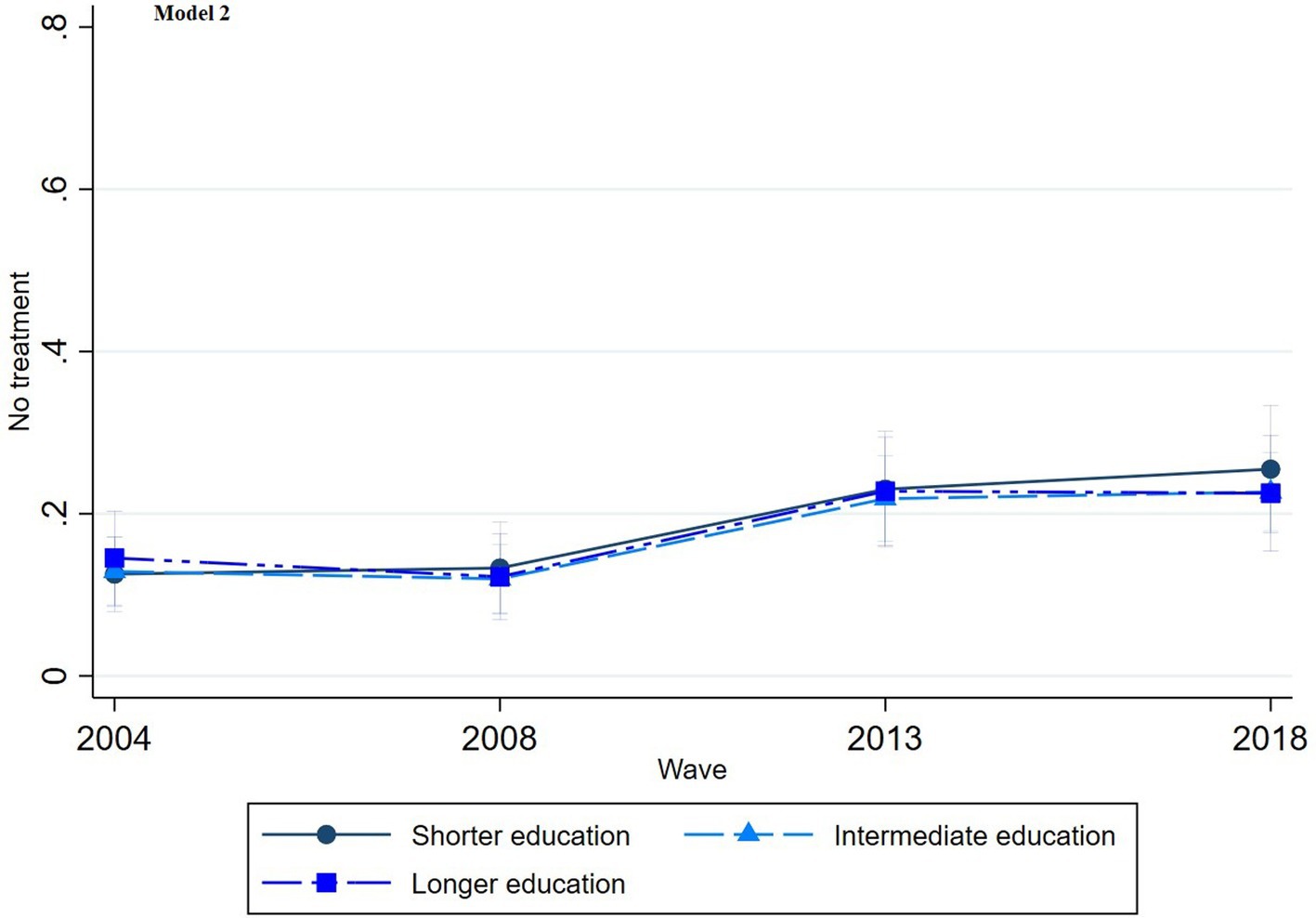

In the second model, which includes both education and household income (see Table 2), education continues to show a significant association with depression treatment. These findings align with those of the first model. However, income does not exhibit a significant association with treatment choice. Additionally, the results indicate that older adults are less likely to favor psychotherapy (ages 45–64: 0.43, p < 0.01; ages 65+: 0.07, p < 0.01) over pharmaceutical treatment. Individuals aged 65 and older are also less inclined to choose combination treatment (0.25, p < 0.001). Non-Belgian respondents show a reduced likelihood of choosing combination treatment (0.56, p < 0.05) and are more likely to opt for no treatment (1.92, p < 0.01) compared to pharmaceutical treatment. Regional differences are also apparent. Individuals from Brussels are more likely to choose combination treatment (1.53, p < 0.05) than those from Flanders, while individuals from Wallonia are less likely to abstain from treatment (0.66, p < 0.05) than their Flemish counterparts. Over time, the likelihood of individuals choosing psychotherapy (2008 = 5.09, p < 0.01; 2013 = 5.86, p < 0.01; 2018 = 12.08, p < 0.001) and combination treatment (2008 = 4.17, p < 0.001; 2013 = 2.33, p < 0.01; 2018 = 4.55, p < 0.001) has increased relative to pharmaceutical treatment. However, in the last two waves, there is also an increased likelihood of individuals not pursuing treatment (2013 = 2.50, p < 0.001; 2018 = 3.50, p < 0.001). Lastly, individuals who had contact with a GP in the past 12 months are less likely to abstain from treatment (0.25, p < 0.001).

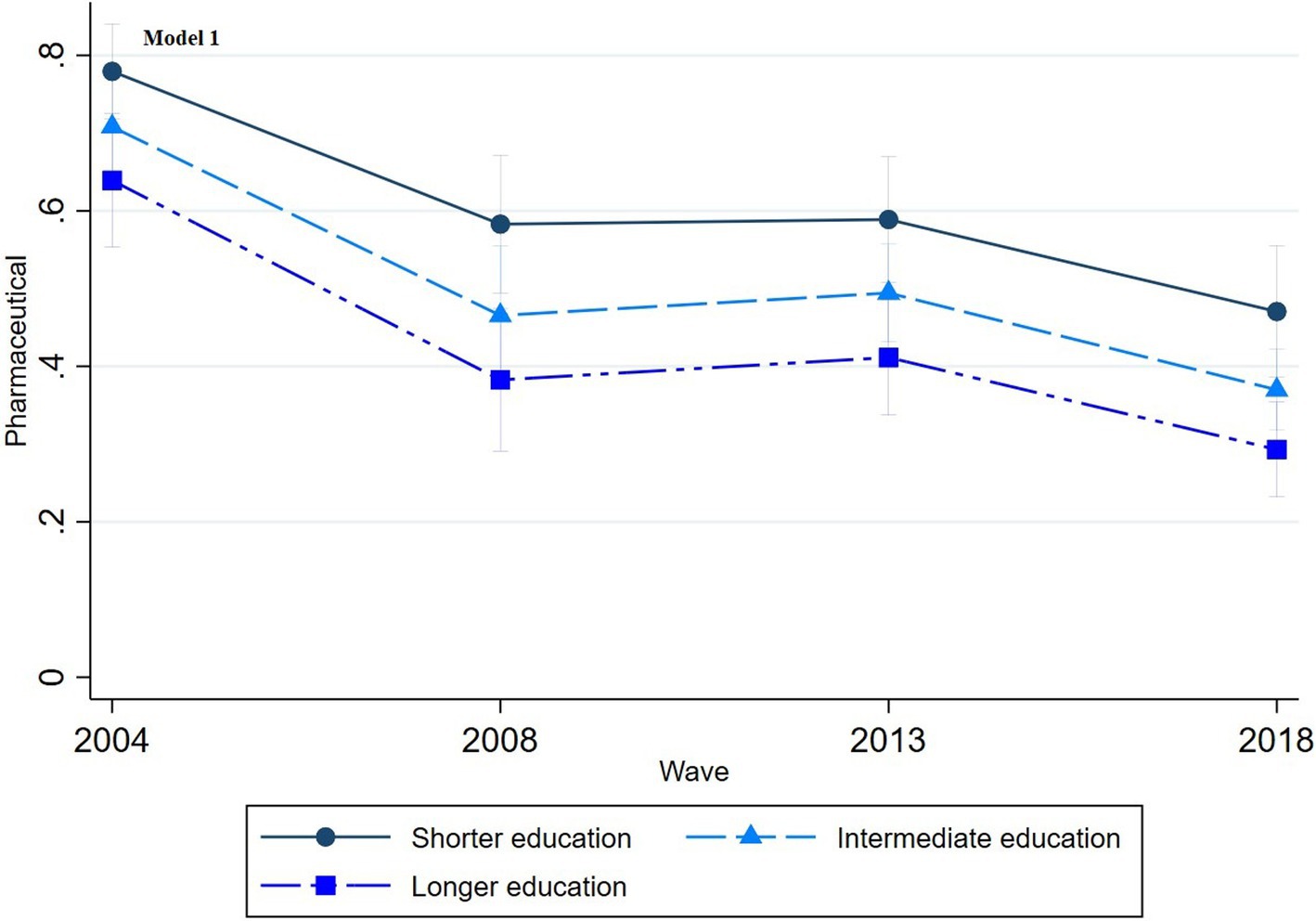

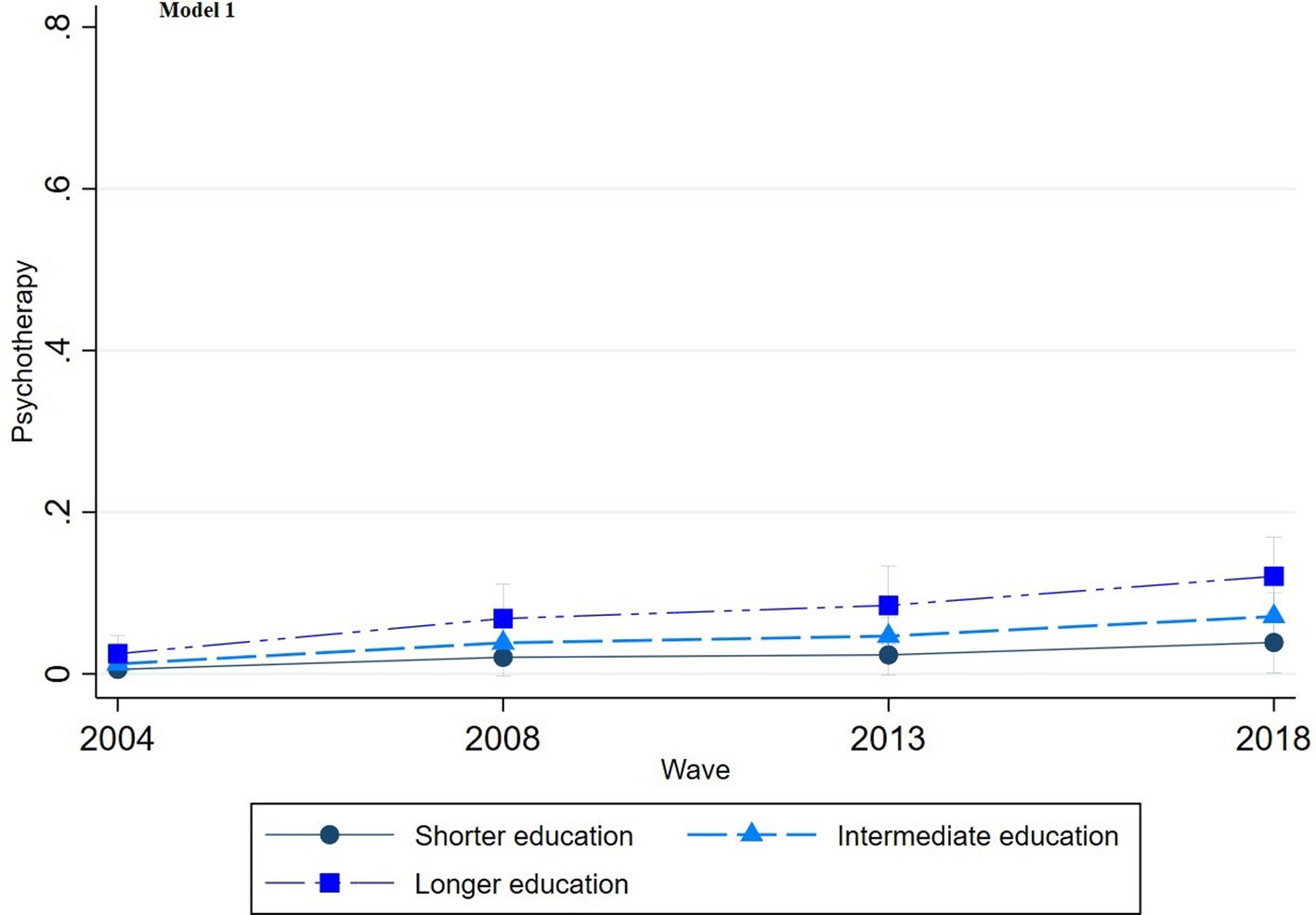

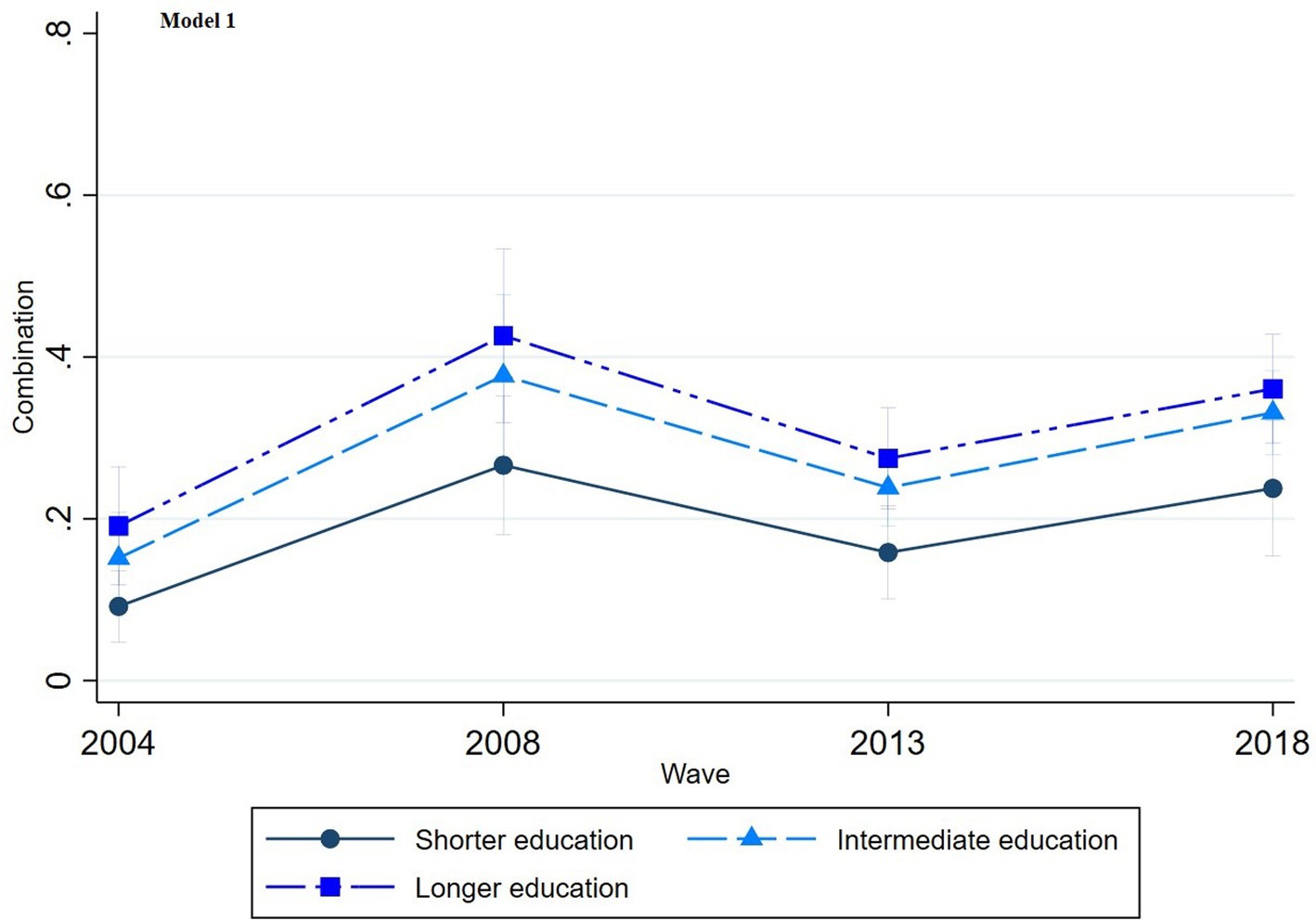

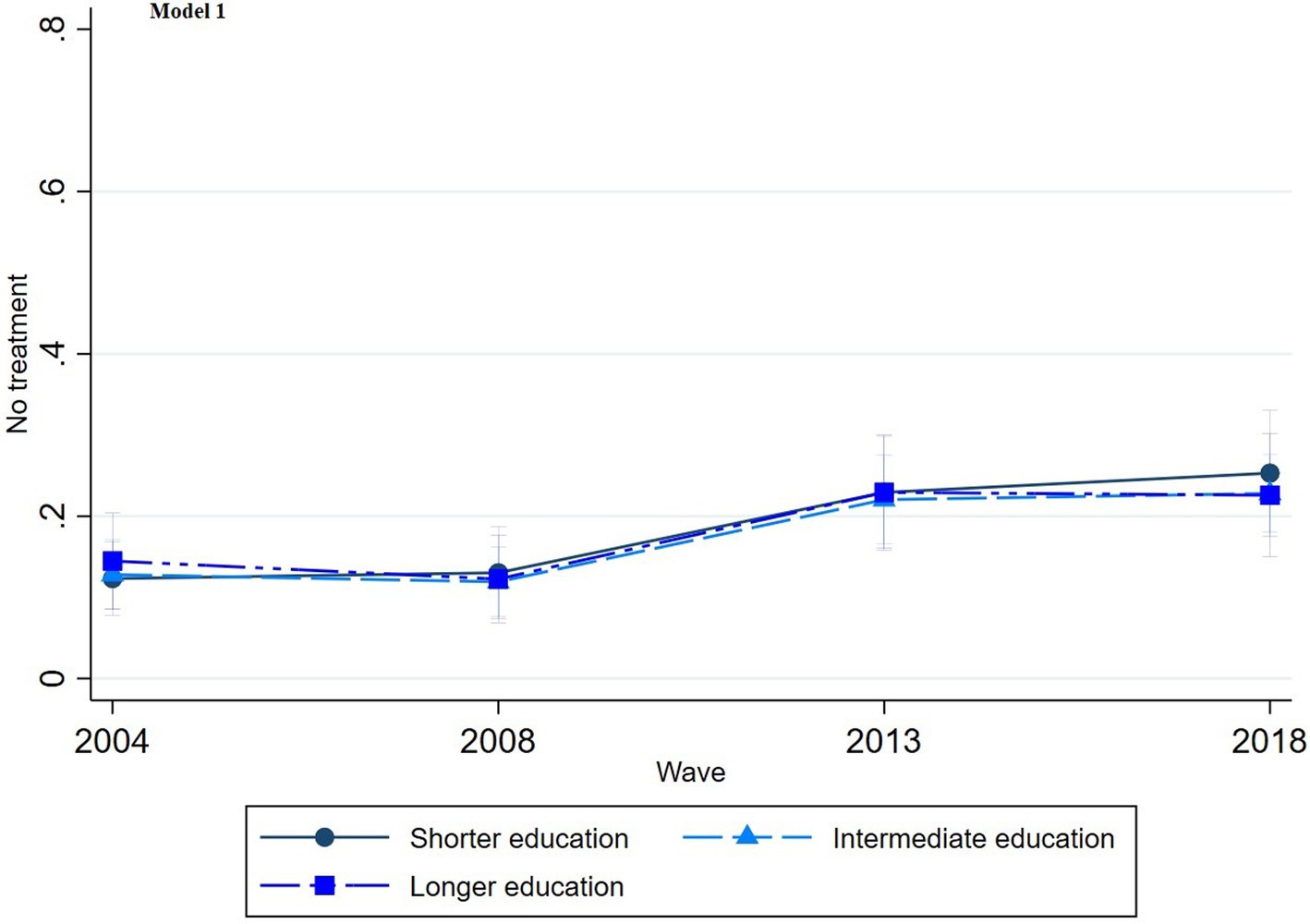

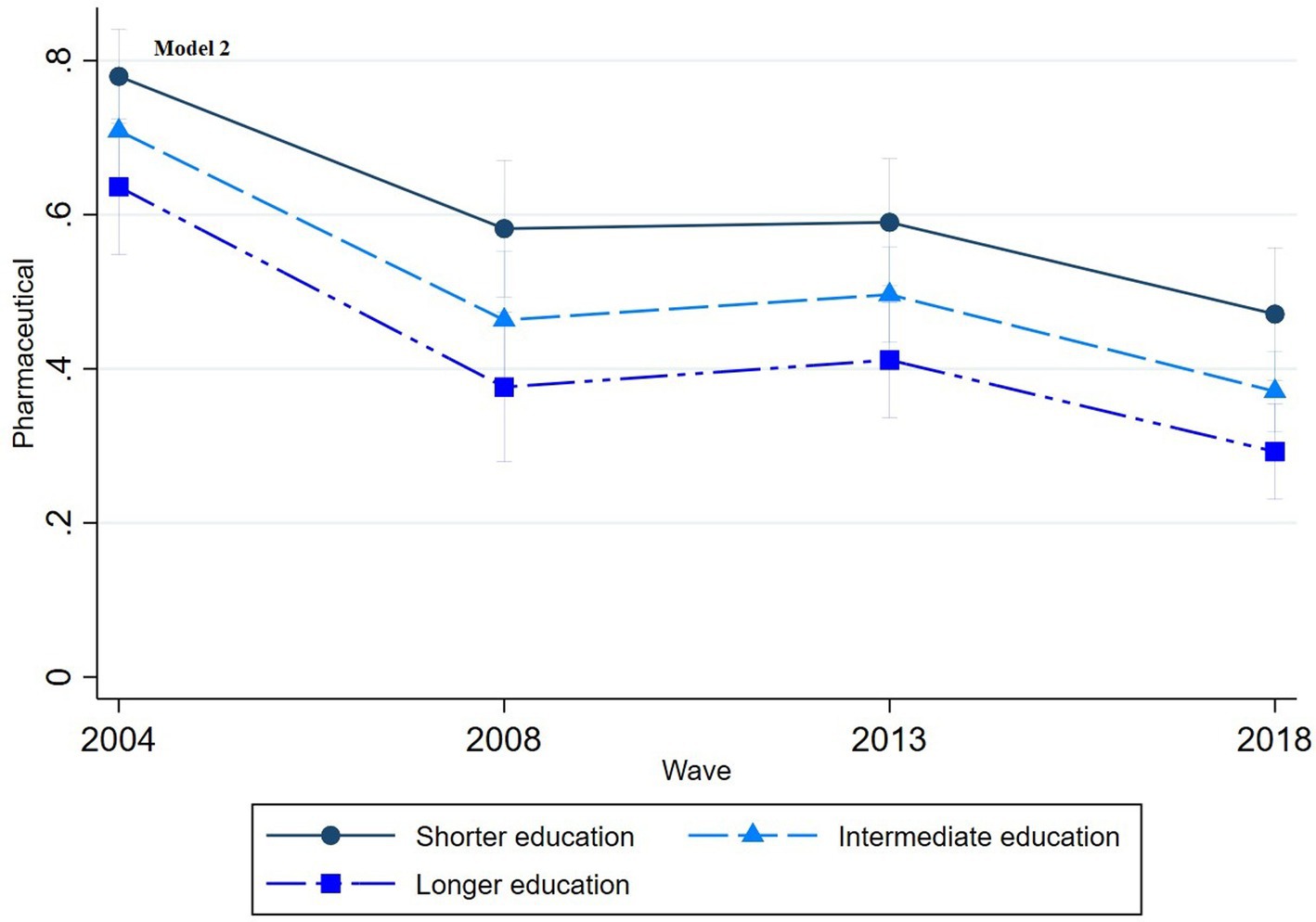

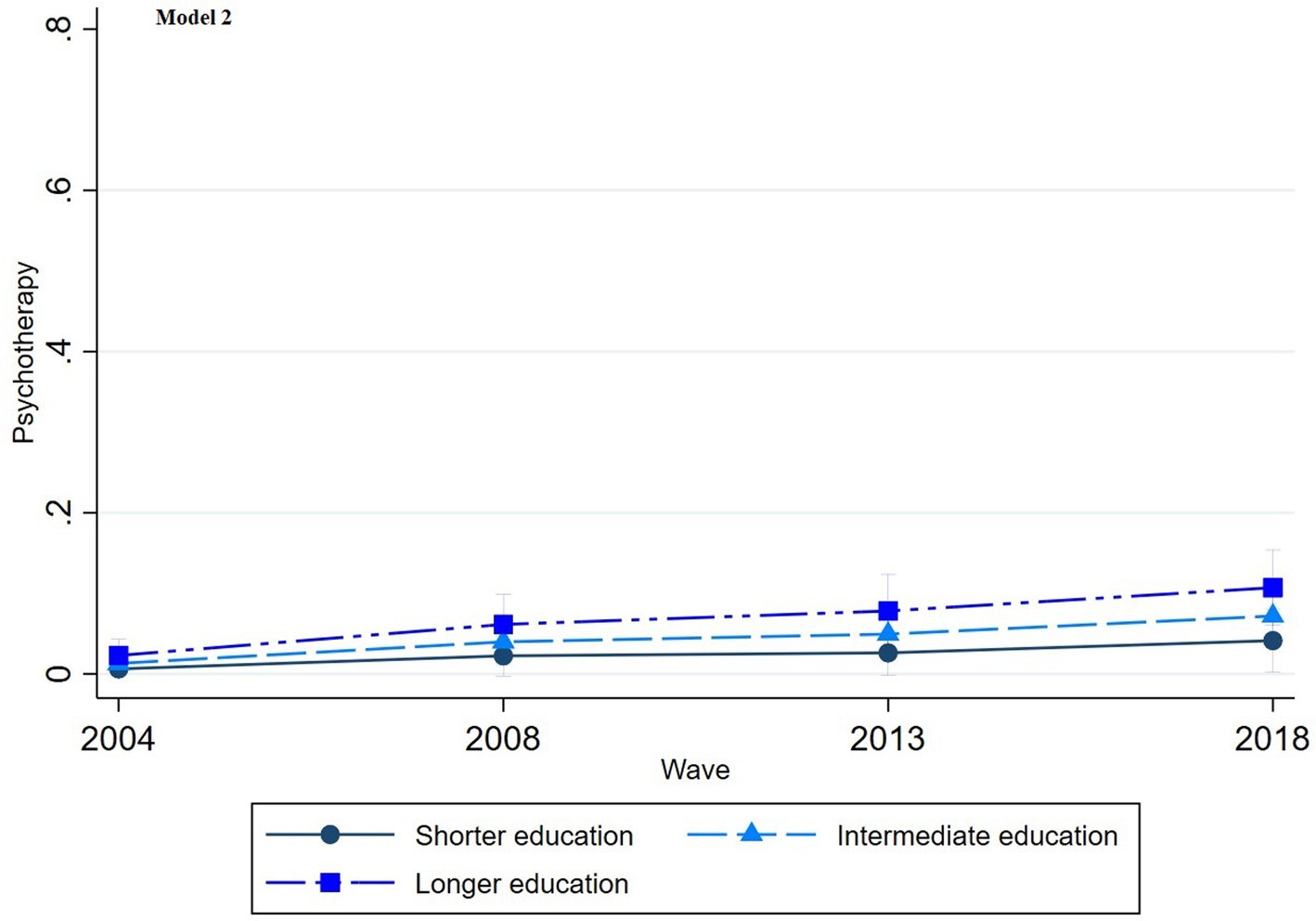

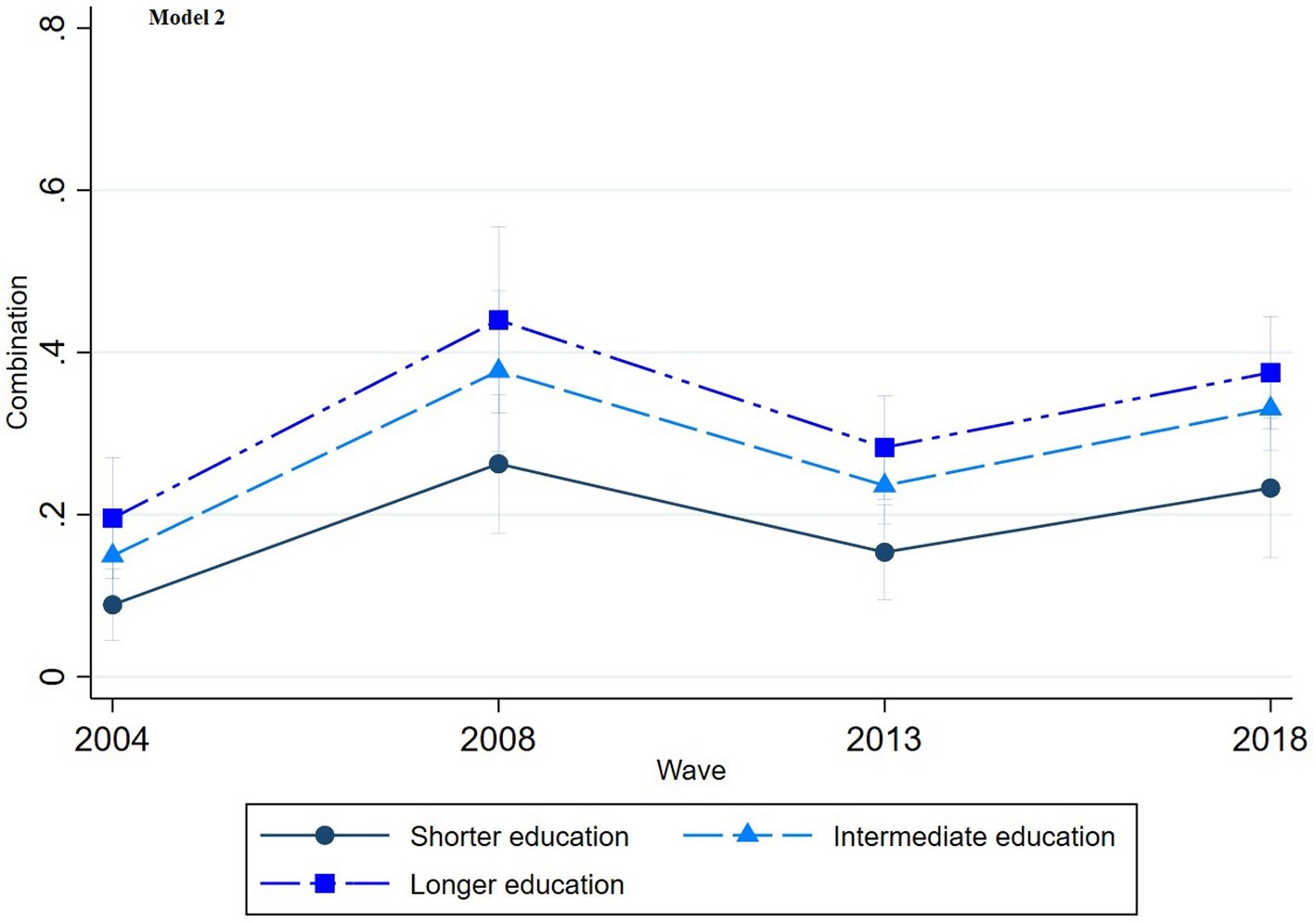

The multinomial regression graphs (see Figures 1–8) provide further insights into temporal trends and model-specific findings. Overall, the graphs show a consistent decline in the use of pharmaceutical treatment, accompanied by an increase in psychotherapy and combination treatment usage. The prevalence of individuals not seeking treatment has also risen over time. The graphs from the first model highlight persistent educational disparities across waves. Meanwhile, the graphs from the second model demonstrate that the educational gradient remains significant even after accounting for household income, suggesting that income does not mitigate the observed educational differences.

Figure 1. Trends in pharmaceutical treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 1 in Table 2.

Figure 2. Trends in psychotherapy treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 1 in Table 2.

Figure 3. Trends in combination treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 1 in Table 2.

Figure 4. Trends in no treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 1 in Table 2.

Figure 5. Trends in pharmaceutical treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 2 in Table 2.

Figure 6. Trends in psychotherapy treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 2 in Table 2.

Figure 7. Trends in combination treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 2 in Table 2.

Figure 8. Trends in no treatment by education across the waves (2004-2018), corresponding to Model 2 in Table 2.

Discussion

Our study reveals several important findings. First, household income does not appear to be related to depression treatment, while education clearly influences depression treatment, with significant and persistent differences observed over time. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that individuals with longer educational attainment are more likely to choose psychotherapy or combination treatment, irrespective of their income. Conversely, individuals with shorter educational attainment are more likely to rely on pharmaceutical treatment alone, even though this approach is considered less optimal and effective (Cuijpers et al., 2020).

Attributing “health benefits” solely to financial resources is therefore insufficient. Supporting both the theory of learned effectiveness (Mirowsky and Ross, 2003) and the concept of cultural health capital (Shim, 2010)—which emphasize the human capital component of education—it can be argued that education fosters health-related knowledge, logic, and competencies. Thus, individuals with longer education are more inclined to engage in effective, rational health behaviors and possess better skills for selecting appropriate treatments (Lawrence, 2017). Additionally, they are more likely to invest in treatments requiring significant effort, skills, and competencies, underscoring education’s importance in shaping health-related decisions and behaviors (Ross and Mirowsky, 2000; Shim, 2010). This aligns with findings from a Canadian study, which also emphasizes the primacy of education among socioeconomic factors that enable effective mental health care use (Steele et al., 2007). Consistent with our findings, this study similarly concluded that income level did not independently relate to mental health care use.

Regarding important temporal trends, the exclusive use of pharmaceutical treatment for depression has decreased, while the adoption of psychotherapy and combination treatments has increased. This shift corresponds with Belgian guidelines (Karyotaki et al., 2014; Superior Health Council, 2019) as well as international recommendations (Jobst et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2016), which increasingly advocate for the inclusion of psychotherapy as part of depression treatment, either alone or in combination with antidepressants. Antidepressant monotherapy alone is no longer regarded as optimal care for depression (Karyotaki et al., 2014). The decline in sole pharmaceutical treatment may also be due to growing awareness of the side effects and withdrawal challenges associated with long-term antidepressant use (Guy et al., 2020). Studies have shown that combined treatment involving psychotherapy has better acceptance rates, resulting in lower dropout rates and a higher likelihood of recovery (Cuijpers et al., 2014; De Jonghe et al., 2001; Ormel et al., 2022). A meta-analysis by Kamenov et al. (2017) also concluded that combined psychotherapy and pharmaceutical treatments perform significantly better than either treatment alone. Both psychotherapy and pharmaceutical treatments are effective for improving functioning; however, when adjusted for publication bias, psychotherapy was found to be more efficacious than pharmacotherapy.

The adoption of “new practices,” such as new depression treatments, initially tends to generate inequalities, with disproportionate use among individuals with longer education (Mackenbach, 2012). This finding aligns with fundamental cause theory (Link and Phelan, 1995; Link and Phelan, 2000) and the broader diffusion of innovations literature (Rogers, 2003). Socialization mechanisms suggest that adopting new practices is not simply about having the financial resources to enable adoption but also the competencies to understand and apply these practices effectively (Lawrence, 2017). This proficiency is shaped by habitual ways of thinking and organizing actions, described as “habitus” (Shim, 2010).

For example, a slight increase in inequality in the use of psychotherapy alone is visible in the graphs. This trend may reflect patient empowerment among individuals with longer education. The traditional model, where GPs make treatment decisions on behalf of patients, is gradually being replaced by one in which patients actively participate in their treatment choices (Camacho, 2014), such as expressing a preference for non-pharmaceutical options. A study of Houle et al. (2013) also found that individuals with a university degree are more inclined to opt for psychotherapy than those with shorter education. With increased awareness of potential side effects and withdrawal challenges, individuals with longer education are better equipped to communicate effectively during psychotherapy and more willing to invest the energy and time required, underscoring attributes more common among those with more formal education.

Some nuances in interpreting the psychotherapy findings are also important. The relatively low number of individuals using psychotherapy alone may be influenced by the significant role of GPs in Belgium’s mental health care system (Boffin et al., 2012; Fraeyman et al., 2012). It is likely that most respondents who reported experiencing depression within the past 12 months consulted a GP, as GPs serve as the primary care contact. Since GPs are the main prescribers of antidepressants, it can be assumed that many patients received antidepressant-based treatment. A study also revealed that, despite abundant mental health resources in Belgium, referral rates to mental health specialists remain low (Kovess-Masfety et al., 2007). A recent qualitative study in Belgium observed that many GPs even permit patients to request repeat antidepressant prescriptions without an appointment, reflecting challenges GPs face in altering routines and instituting regular, proactive reviews of antidepressant prescriptions (Van Leeuwen et al., 2021).

Combination treatment is disproportionately less used among individuals with shorter education, likely influenced by GPs’ treatment approaches. Studies have shown that GPs often tailor treatment decisions based on patients’ socioeconomic position (Bernheim et al., 2008; Hyde et al., 2005). For instance, research has found that GPs perceive individuals with shorter education as lacking the resources to manage more “active” treatments. A Norwegian study supporting this notion observed that patients with shorter education levels receive shorter consultations but undergo more medical tests per visit (Brekke et al., 2018). The quality of these consultations correlates with patients’ communicative or cognitive proficiencies, more often associated with education than income. This finding suggests that GPs may be more likely to endorse a “medical approach” when treating individuals with shorter education levels.

Research implications

Institutional factors such as treatment policies, reimbursement regulations, and the role of GPs can significantly influence disparities in depression treatment. To gain a comprehensive understanding of how these institutional factors contribute to inequalities, future studies should use nuanced measures of institutional variables, such as first-or second-line treatment prescriptions, frequency of GP interactions, and psychotherapy waiting lists in specific regions. Another recommendation is to use dimensional indicators instead of categorical ones to independently measure “need” (mental health status) and “treatment,” as suggested by Coghill and Sonuga-Barke (2012), to allow a more nuanced analysis of treatment disparities. Longitudinal studies that follow individuals over time could also provide valuable insights into how changes in socioeconomic position, such as income, influence shifts in treatment choice, offering a dynamic understanding of treatment disparities.

Considering the growing trend toward non-pharmaceutical mental health approaches, future research in Belgium could examine recent psychotherapy reimbursement regulations, introduced in March 2019 and September 2021, which aim to improve accessibility and affordability (Mistiaen et al., 2019). However, our findings suggest that these regulatory changes may not suffice to eliminate social disparities in the utilization of effective treatments.

Limitations

This study has two important limitations. First, the dependent variable “depression treatment” was measured only for respondents who self-reported experiencing depression within the past 12 months, which significantly reduced the initial sample. This decision was made by Sciensano (BHIS coordinator). Second, self-reported data can be influenced by respondents’ individual perceptions (Jylhä, 2009). While previous studies have supported the validity and reliability of self-reported health information (Halford et al., 2012; Pu et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2021), the stigma surrounding depression may contribute to self-report bias (Chan and Mak, 2017; Hunt et al., 2003).

Conclusion

This study presents two primary conclusions. First, it identifies a distinct social gradient in depression treatment, with education significantly shaping treatment decisions. Individuals with longer education are more likely to choose psychotherapy or combination treatment, while those with shorter education are more inclined toward pharmaceutical treatment alone. This discrepancy persists over time, underscoring education’s persistent influence. Second, the findings emphasize the inadequacy of attributing “health benefits” solely to financial resources; instead, education plays a critical role in guiding rational health behaviors and treatment decisions. The trend toward integrating psychotherapy, often combined with antidepressants, also reflects a shift away from antidepressant monotherapy. The evolving role of patient agency in treatment choices is also highlighted, as patients’ active participation in their treatment decisions grows in importance. These findings underscore the complex interplay between education, patient empowerment, and the evolving landscape of depression treatment.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data will not be deposited since its subject to a contract with Sciensano (The Scientific Institute of public health of the federal Belgian State). Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://www.sciensano.be/nl/node/55737/gezondheidsenquete-aanvraagprocedure-microgegevens.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LC designed the study, performed the data analysis, and had primary responsibility for writing and editing the manuscript. KD and PB critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors provided final approval for the article to be published.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2025.1204794/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Reference category.

References

Albani, C., Blaser, G., Geyer, M., Schmutzer, G., and Brähler, E. (2010). Outpatient psychotherapy in Germany from the patient's point of view [Ambulante Psychotherapie in Deutschland aus Sicht der Patienten]. Psychotherapeut 55, 503–514. doi: 10.1007/s00278-010-0778-z

Andersen, I., Thielen, K., Nygaard, E., and Diderichsen, F. (2009). Social inequality in the prevalence of depressive disorders. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 63, 575–581. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082719

Baker, D. (2011). Forward and backward, horizontal and vertical: transformation of occupational credentialing in the schooled society. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 29, 5–29. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2011.01.001

Baker, D. (2014). The schooled society: the educational transformation of global culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Balsa, A. I., and McGuire, T. G. (2003). Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. J. Health Econ. 22, 89–116. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00098-X

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Bernheim, S. M., Ross, J. S., Krumholz, H. M., and Bradley, E. H. (2008). Influence of patients’ socioeconomic status on clinical management decisions: a qualitative study. Ann. Family Med. 6, 53–59. doi: 10.1370/afm.749

Boffin, N., Bossuyt, N., Declercq, T., Vanthomme, K., and Van Casteren, V. (2012). Incidence, patient characteristics and treatment initiated for GP-diagnosed depression in general practice: results of a 1-year nationwide surveillance study. Fam. Pract. 29, 678–687. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms024

Brekke, K. R., Holmås, T. H., Monstad, K., and Straume, O. R. (2018). Socio-economic status and physicians' treatment decisions. Health Econ. 27, e77–e89. doi: 10.1002/hec.3621

Briffault, X., Sapinho, D., Villamaux, M., and Kovess, V. (2008). Factors associated with use of psychotherapy. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 43, 165–171. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0281-1

Butterworth, P., Olesen, S. C., and Leach, L. S. (2013). Socioeconomic differences in antidepressant use in the PATH through life study: evidence of health inequalities, prescribing bias, or an effective social safety net? J. Affect. Disord. 149, 75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.006

Camacho, N. (2014). “Patient empowerment: Consequences for pharmaceutical marketing and for the patient-physician relationship,” in Innovation and marketing in the pharmaceutical industry: Emerging practices, research, and policies. eds. M. Ding, J. Eliashberg, and S. Stremersch (New York, NY: Springer), 425–455.

Casteels, M., Danckaerts, M., De Lepeleire, J., Demyttenaere, K., Laekeman, G., Luyten, P., et al. (2010). The increasing use of psychotropic drugs [Het toenemend gebruik van psychofarmaca]. Metaforum Visietekst 1, 1–28.

Chan, K. K. S., and Mak, W. W. S. (2017). The content and process of self-stigma in people with mental illness. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 87, 34–43. doi: 10.1037/ort0000127

Clouston, S. A. P., and Link, B. G. (2021). A retrospective on fundamental cause theory: state of the literature, and goals for the future. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 47, 131–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-090320-094912

Coghill, D., and Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2012). Annual research review: categories versus dimensions in the classification and conceptualization of child and adolescent mental disorders–implications of recent empirical study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 53, 469–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02511.x

Cuijpers, P., Noma, H., Karyotaki, E., Vinkers, C. H., Cipriani, A., and Furukawa, T. A. (2020). A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry 19, 92–107. doi: 10.1002/wps.20701

Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S. L., Andersson, G., Beekman, A. T., and Reynolds, C. F. III (2014). Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Focus 12, 347–358. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.12.3.347

Cutler, D. M., and Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence (NBER Working Paper No. 12352). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w12352

Davey, C. G., and Chanen, A. M. (2016). The unfulfilled promise of the antidepressant medications. Med. J. Aust. 204, 348–350. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00194

De Jonghe, F., Kool, S., Van Aalst, G., Dekker, J., and Peen, J. (2001). Combining psychotherapy and antidepressants in the treatment of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 64, 217–229. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00259-7

Declercq, T., Habraken, H., and Van Den Ameele, H. (2017). Depression in adults - review of committee guidelines [Depressie bij volwassenen - Herziening van de commissie richtlijnen]. Domus Medica. Available at: https://www.domusmedica.be/sites/default/files/Richtlijn%20depressie%20bij%20volwassenen_0.pdf (Accessed March 28, 2023).

Driessen, E., Dekker, J. J., Peen, J., Van, H. L., Maina, G., Rosso, G., et al. (2020). The efficacy of adding short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy to antidepressants in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 80:101886. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101886

Ector, S. (2016). Comparison of reimbursement of psychotherapy and psychological counseling by the different health insurance funds [Vergelijking terugbetaling van psychotherapie en psychologische begeleiding door de verschillende mutualiteiten]. Flemish Patient Forum [Vlaams Patiëntenplatform]. Available at: https://vlaamspatientenplatform.be/storage/files/e4b05dd7-b5a0-4edb-b48f-4e491788e689/2022-overzichtstabel-terugbetaling-psychotherapie-en-psychologische-begeleiding.pdf (Accessed March 2, 2023).

Fraeyman, J., Van Hal, G., De Loof, H., Remmen, R., De Meyer, G., and Beutels, P. (2012). Potential impact of policy regulation and generic competition on sales of cholesterol lowering medication, antidepressants and acid blocking agents in Belgium. Acta Clin. Belg. 67, 160–171. doi: 10.2143/ACB.67.3.2062650

Freese, J., and Lutfey, K. (2011). “Fundamental causality: challenges of an animating concept for medical sociology,” in Handbook of the sociology of health, illness, and healing: a blueprint for the 21st century. eds. B. A. Pescosolido, J. K. Martin, J. D. McLeod, and A. Rogers (New York, NY: Springer), 67–81.

Gisle, L., Drieskens, S., Demarest, S., and Van der Heyden, J. (2018). Mental health: Health interview survey 2018 [Geestelijke gezondheid: Gezondheidsenquête 2018]. Sciensano. Available at: https://www.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/1-mental_health_report_2018_nl2.pdf (Accessed March 23, 2023).

Guy, A., Brown, M., Lewis, S., and Horowitz, M. (2020). The ‘patient voice’: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition. Therap. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 10:2045125320967183. doi: 10.1177/2045125320967183

Halford, C., Wallman, T., Welin, L., Rosengren, A., Bardel, A., Johansson, S., et al. (2012). Effects of self-rated health on sick leave, disability pension, hospital admissions and mortality: a population-based longitudinal study of nearly 15,000 observations among Swedish women and men. BMC Public Health 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1103

Halonen, J. I., Koskinen, A., Kouvonen, A., Varje, P., Pirkola, S., and Väänänen, A. (2018). Distinctive use of newer and older antidepressants in major geographical areas: a nationally representative register-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 229, 358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.102

Hansen, D. G., Søndergaard, J., Vach, W., Gram, L. F., Rosholm, J.-U., Mortensen, P., et al. (2004). Socio-economic inequalities in first-time use of antidepressants: a population-based study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60, 51–55. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0723-y

Hirschfeld, R. M., and Cross, C. K. (1982). Epidemiology of affective disorders: psychosocial risk factors. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 35–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290010013003

Houle, J., Villaggi, B., Beaulieu, M. D., Lespérance, F., Rondeau, G., and Lambert, J. (2013). Treatment preferences in patients with first episode depression. J. Affect. Disord. 147, 94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.016

Hunt, M., Auriemma, J., and Cashaw, A. C. (2003). Self-report bias and underreporting of depression on the BDI-II. J. Pers. Assess. 80, 26–30. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_10

Hyde, J., Calnan, M., Prior, L., Lewis, G., Kessler, D., and Sharp, D. (2005). A qualitative study exploring how GPs decide to prescribe antidepressants. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 55, 755–762. doi: 10.3399/bjgp05X53596

Jobst, A., Brakemeier, E., Buchheim, A., Caspar, F., Cuijpers, P., Ebmeier, K., et al. (2016). European psychiatric association guidance on psychotherapy in chronic depression across Europe. Eur. Psychiatry 33, 18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.12.003

Jylhä, M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013

Kamenov, K., Twomey, C., Cabello, M., Prina, A. M., and Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2017). The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 414–425. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002774

Karyotaki, E., Smit, Y., Cuijpers, P., Debauche, M., De Keyser, T., Habraken, H., et al. (2014). The long-term efficacy of psychotherapy, alone or in combination with antidepressants, in the treatment of adult major depression (KCE Reports 230). Brussels, Belgium: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre.

Karyotaki, E., Smit, Y., Henningsen, K. H., Huibers, M., Robays, J., De Beurs, D., et al. (2016). Combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy or monotherapy for major depression? A meta-analysis on the long-term effects. J. Affect. Disord. 194, 144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.036

Kessler, R. C., and Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409

Kestilä, L., Koskinen, S., Martelin, T., Rahkonen, O., Pensola, T., Aro, H., et al. (2006). Determinants of health in early adulthood: what is the role of parental education, childhood adversities and own education? Eur. J. Public Health 16, 305–314. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki164

Kloosterman, R., Ruiter, S., De Graaf, P. M., and Kraaykamp, G. (2009). Parental education, children's performance and the transition to higher secondary education: trends in primary and secondary effects over five Dutch school cohorts (1965–99). Br. J. Sociol. 60, 377–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01235.x

Kohn, L., Obyn, C., Adriaenssens, J., Christiaens, W., Van Cauter, X., and Eyssen, M. (2016). Model for the organization and reimbursement of psychological and orthopedagogical care in Belgium Brussels, Belgium: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre. 265, 1–104.

Kovess-Masfety, V., Alonso, J., Brugha, T. S., Angermeyer, M. C., Haro, J. M., Sevilla-Dedieu, C., et al. (2007). Differences in lifetime use of services for mental health problems in six European countries. Psychiatr. Serv. 58, 213–220. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.2.213

Lawrence, E. M. (2017). Why do college graduates behave more healthfully than those who are less educated? J. Health Soc. Behav. 58, 291–306. doi: 10.1177/0022146517715671

Link, B. G., and Phelan, J. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 35, 80–94. doi: 10.2307/2626958

Link, B. G., and Phelan, J. C. (2000). “Evaluating the fundamental cause explanation for social disparities in health,” in Handbook of medical sociology. (5th ed.). eds. C. E. Bird, P. Conrad, and A. M. Fremont (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall), 33–46.

Link, B. G., and Phelan, J. C. (2010). “Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities,” in Handbook of medical sociology (6th ed.). eds. C. E. Bird, P. Conrad, A. M. Fremont, and S. Timmermans (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press), 17–33.

Loef, B., Meulman, I., Herber, G.-C. M., Kommer, G. J., Koopmanschap, M. A., Kunst, A. E., et al. (2021). Socioeconomic differences in healthcare expenditure and utilization in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06694-9

Lorant, V., Deliège, D., Eaton, W., Robert, A., Philippot, P., and Ansseau, M. (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182

Lund, C., Breen, A., Flisher, A. J., Kakuma, R., Corrigall, J., Joska, J. A., et al. (2010). Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027

Mackenbach, J. P. (2012). The persistence of health inequalities in modern welfare states: the explanation of a paradox. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.031

Marcus, M., Yasamy, M. T., van Ommeren, M., Chisholm, D., and Saxena, S. (2012). “Depression: A global public health concern,” in World Federation for Mental Health, Depression: A global crisis (Occoquan, VA: World Federation for Mental Health), 6–8.

Mirowsky, J., and Ross, C. E. (2003). Social causes of psychological distress. 2nd Edn. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Mirowsky, J., and Ross, C. E. (2005). Education, learned effectiveness and health. Lond. Rev. Educ. 3, 205–220. doi: 10.1080/14748460500372366

Mistiaen, P., Cornelis, J., Detollenaere, J., Devriese, S., Farfan-Portet, M.-I., and Ricour, C. (2019). Organisation of mental health care for adults in Belgium (KCE Report 318, D/2019/10.273/50). Brussels, Belgium: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre.

Mojtabai, R. (2009). Unmet need for treatment of major depression in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 297–305. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297

Montez, J. K., and Friedman, E. M. (2015). Educational attainment and adult health: under what conditions is the association causal? Soc. Sci. Med. 127, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.029

Müller, W., and Karle, W. (1993). Social selection in educational systems in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 9, 1–23. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036652

Olfson, M., and Marcus, S. C. (2009). National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81

Ormel, J., Hollon, S. D., Kessler, R. C., Cuijpers, P., and Monroe, S. M. (2022). More treatment but no less depression: the treatment-prevalence paradox. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 91:102111. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102111

Perry, M. J. (1996). The relationship between social class and mental disorder. J. Prim. Prev. 17, 17–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02262736

Pfeffer, F. T. (2008). Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 24, 543–565. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn026

Pu, C., Bai, Y. M., and Chou, Y. J. (2013). The impact of self-rated health on medical care utilization for older people with depressive symptoms. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 479–486. doi: 10.1002/gps.3849

Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte-en Invaliditeitsverzekering. (n.d.). Primary psychological care in a mental health network [Eerstelijns psychologische zorg in een netwerk voor geestelijke gezondheid]. RIZIV. Available at: https://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/thema-s/verzorging-kosten-en-terugbetaling/wat-het-ziekenfonds-terugbetaalt/geestelijke-gezondheidszorg/eerstelijns-psychologische-zorg-in-een-netwerk-voor-geestelijke-gezondheid

Ross, C. E., and Mirowsky, J. (2000). Does medical insurance contribute to socioeconomic differentials in health? Milbank Q. 78, 291–321. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00171

Santos, B. F., Oliveira, H. N., Miranda, A. E. S., Hermsdorff, H. H. M., Bressan, J., Vieira, J. C. M., et al. (2021). Research quality assessment: reliability and validation of the self-reported diagnosis of depression for participants of the cohort of universities of Minas Gerais (CUME project). J. Affective Disord. Rep. 6:100238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100238

Schofer, E., and Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 70, 898–920. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000602

Shavers, V. L. (2007). Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 99, 1013–1023

Shim, J. K. (2010). Cultural health capital: a theoretical approach to understanding health care interactions and the dynamics of unequal treatment. J. Health Soc. Behav. 51, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/0022146509361185

Spijker, J., van Straten, A., Bockting, C. L., Meeuwissen, J. A., and van Balkom, A. J. (2013). Psychotherapy, antidepressants, and their combination for chronic major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Can. J. Psychiatry 58, 386–392. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800703

Steele, L. S., Dewa, C. S., Lin, E., and Lee, K. L. (2007). Education level, income level and mental health services use in Canada: associations and policy implications. Healthcare Policy 3, 96–106. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2007.19177

Suoyrjö, H., Hinkka, K., Kivimäki, M., Klaukka, T., Pentti, J., and Vahtera, J. (2007). Allocation of rehabilitation measures provided by the social insurance institution in Finland: a register linkage study. J. Rehabil. Med. 39, 198–204. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0035

Superior Health Council (2019). DSM (5): The use and status of diagnosis and classification of mental health problems (report 9360). Brussels: SHC.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2012). International Standard Classification of Education: ISCED 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

van Bronswijk, S., Moopen, N., Beijers, L., Ruhe, H. G., and Peeters, F. (2019). Effectiveness of psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 49, 366–379. doi: 10.1017/S003329171800199X

Van Leeuwen, E., Anthierens, S., van Driel, M. L., Sutter, A., Van den Branden, E., and Christiaens, T. (2021). 'Never change a winning team': GPs' perspectives on discontinuation of long-term antidepressants. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 39, 533–542. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2021.2006487

Van Maldegem, P. (2021). Rate of 11 euros not for every session with psychologist [Tarief van 11 euro niet voor elke sessie bij psycholoog]. De Tijd. Available at: https://www.tijd.be/netto/analyse/gezinsuitgaven/tarief-van-11-euro-niet-voor-elke-sessie-bij-psycholoog/10324523.html (Accessed March 2, 2023).

Vandekerckhove, S. (2016). General practitioners receive first aid for depression treatment [Huisartsen krijgen eerste hulp bij behandeling depressie]. De Morgen. Available at: https://www.demorgen.be/tech-wetenschap/huisartsen-krijgen-eerste-hulp-bij-behandeling-depressie~b40e5f75/ (Accessed March 2, 2023).

Veugelers, P. J., and Yip, A. M. (2003). Socioeconomic disparities in health care use: does universal coverage reduce inequalities in health? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 57, 424–428. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.424

Willems, S., De Maesschalck, S., Deveugele, M., Derese, A., and De Maeseneer, J. (2005). Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor–patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient Educ. Couns. 56, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.011

Winkleby, M. A., Jatulis, D. E., Frank, E., and Fortmann, S. P. (1992). Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Public Health 82, 816–820. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.816

World Health Organization (2014). Social determinants of mental health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Keywords: depression, depression treatment, mental health care use, income inequalities, educational inequalities

Citation: Colman L, Delaruelle K and Bracke P (2025) The role of education as a socialization mechanism in addressing the social gradient in depression treatment in Belgium (2004–2018). Front. Sociol. 10:1204794. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1204794

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Tze Kiat Lai, University of Science Malaysia, MalaysiaMuhammad Suhaimi Mohd Yusof, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia

Annalisa Grandi, University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Colman, Delaruelle and Bracke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa Colman, TGlzYS5Db2xtYW5AVUdlbnQuYmU=

Lisa Colman

Lisa Colman Katrijn Delaruelle

Katrijn Delaruelle Piet Bracke

Piet Bracke