94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Sociol., 22 September 2023

Sec. Gender, Sex and Sexualities

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2023.1153321

Housework is a key area of research across many academic fields as it represents the intersection of micro- and macro-level gender dynamics. Despite many shifts in both women's and men's economic activities, and men's changing gender beliefs, women remain largely responsible for the management and performance of domestic labor. Given the relationship between paid employment and household work, this research describes patterns of women's and men's housework before, during, and after the Great Recession. Using American Time Use Survey data, I perform latent profile analysis to document the distributions of housework tasks and time for women and men across these three time periods. While women perform the majority of housework across the time frame, women and men converge in their time during the Recession. Further, men's time becomes more varied and more similar to women's Post-Recession. The findings in this research brief highlight the connections between macro-level change and micro-level behavior.

Housework is a key area of research across many academic fields as it represents the intersection of micro- and macro-level gender dynamics (see Scarborough and Risman, 2017, for a discussion of these intersections). Despite many shifts in both women's and men's economic activities, and men's changing gender beliefs, women remain largely responsible for the management and performance of domestic labor (Bianchi et al., 2012). Further, there are patterns to the tasks that women and men perform when engaging in housework (e.g., Arrighi and Maume, 2000; Kolpashnikova and Kan, 2021).

While scholars studying domestic labor have found consistently that time in the labor market has a negative relationship with housework (e.g., Besen-Cassino and Cassino, 2014), the recent Great Recession provided a massive economic shock that upended employment opportunities for women and men who desired to be in the labor market. The Great Recession, as coined by economists, officially began in December 2007 and ended in 2011 (Boushey, 2011). This Recession was the longest and deepest since World War II, a global economic event that touched all segments of the labor market in some way (Goodman and Mance, 2011; Kochhar, 2011). Berik and Kongar (2013) documented the effects of the Great Recession and extended Recession after the jobless recovery on married mother's and fathers' time allocation across paid work, unpaid work (housework, child care, and adult care), personal care, and leisure. They found, among other things, that the Recession did not reduce the gender disparity in the performance of housework (Berik and Kongar, 2013). This is consistent with other findings, where men's time on housework relative to women's was both less variable and more responsive to external forces (Khitarishvili and Kim, 2014), even as women performed less housework and men performed more after the Recession relative to the few years prior to the Recession (Davis and Greenstein, 2020).

This paper expands research on housework performed in the early part of the 21st century in the United States by documenting patterns in housework task allocation among women and men in three distinct time periods: before, during, and after the Great Recession. This exploratory analysis provides insights into how average American women and men may or may not have shifted their household labor time during and after the Recession. The exploratory comparison of patterns across the three time periods allows examination of possible associations of gendered task allocation and external social forces. For example, the patterns of task allocation between and among women and men may have become more similar to one another due to the pressures of the Great Recession, consistent with theories of time availability (see Gough and Killewald, 2011, for a review). Alternatively, the perceived gendered nature of the early Recession (Christensen, 2015) may have led to both women and men engaging in gender deviance neutralization (Greenstein, 2000; but see Gough and Killewald, 2010; Hook, 2017), wherein women perform more housework and men perform less when their economic circumstances may threaten their gendered identities. In this research brief, I provide insights into the basic patterns of women's and men's task allocation across the three time periods but do not specifically test hypotheses due to the exploratory nature of the analysis.

These analyses utilize data gathered for the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), pooling 13 cross-sections (2003–2015) using the ATUS extract builder (Hofferth et al., 2013) that contained a total of 170,842 respondents. The ATUS is a nationally representative sample sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics focusing on how Americans spend their time. Respondents are drawn from participants in the Current Population Survey (CPS), which samples the civilian noninstitutional population. Each state is sampled proportional to its share of the national population. Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, and households with children are oversampled. One adult in each sampled household is selected for interview. Respondents are interviewed by telephone about their time use starting at 4 a.m. the previous day and continuing for 24 hours. For more details about the ATUS sampling and interview procedures, see Bureau of the Census. (2019).

From the 170,842 ATUS respondents across the 13 cross-sections I analyzed reports of housework tasks from respondents who were currently in a marital or nonmarital union. Of the 170,842 respondents, 79,875 were not currently in a marital or nonmarital union (for reference, 6,950 respondents (7.6%) were in a nonmarital union, while 519 (about.6%) were in same-sex couples). The 91,057 respondents who were currently in a union were classified based upon the time period in which they responded to the survey: Pre-Recession (2003-2007), Recession and jobless recovery (2008–2010), and Post-Recession (2011–2015).

In this paper, I examine household labor, operationalized as the total number of minutes per day spent on household tasks. These tasks were part of the time diary, where respondents were asked about the activities performed during the day as well as the duration of time spent on each activity. I organized the ATUS housework categories into eight general task groupings, five of which are considered what has been called “routine housework” by others using these data (Hook, 2017; Ruppanner et al., 2021): Meals, Kitchen Work, Cleaning, Grocery Shopping, Laundry. I also included tasks that are considered by scholars as unpaid household labor but are less routine (Krantz-Kent, 2009): Bills, Driving, and Yardwork.

I performed Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017), an approach that seeks to uncover patterns of behaviors in the data. These patterns are categorized as classes. As an analytic approach, LPA is designed to examine large amounts of continuous data for patterns that represent classes of people in the population. It is appropriate for these data as it reveals distinct groups from among the data when membership markers for groups are unknown. I performed LPA separately for women and men within each of the three time periods. I utilized multiple fit statistics to evaluate the models and determined the class enumeration in each time period for women and men as described in Tables 1, 2 (see the Appendix for the fit statistics). Table 1 presents women's distributions of time within and across the three time periods, while Table 2 presents the same distributions for men. The classes are presented in ascending order by minutes spent on housework. The naming conventions/labels used for the classes are purely descriptive and are of my own creation, used to enable further comparisons among the patterns documented. I provide further explanation of the labels I attributed to the classes in the Results section.

To address the questions regarding changing patterns of housework for women and men, I performed LPA separately by sex. I present the separate analyses here, followed by a description of the comparison of women and men in the Discussion section.

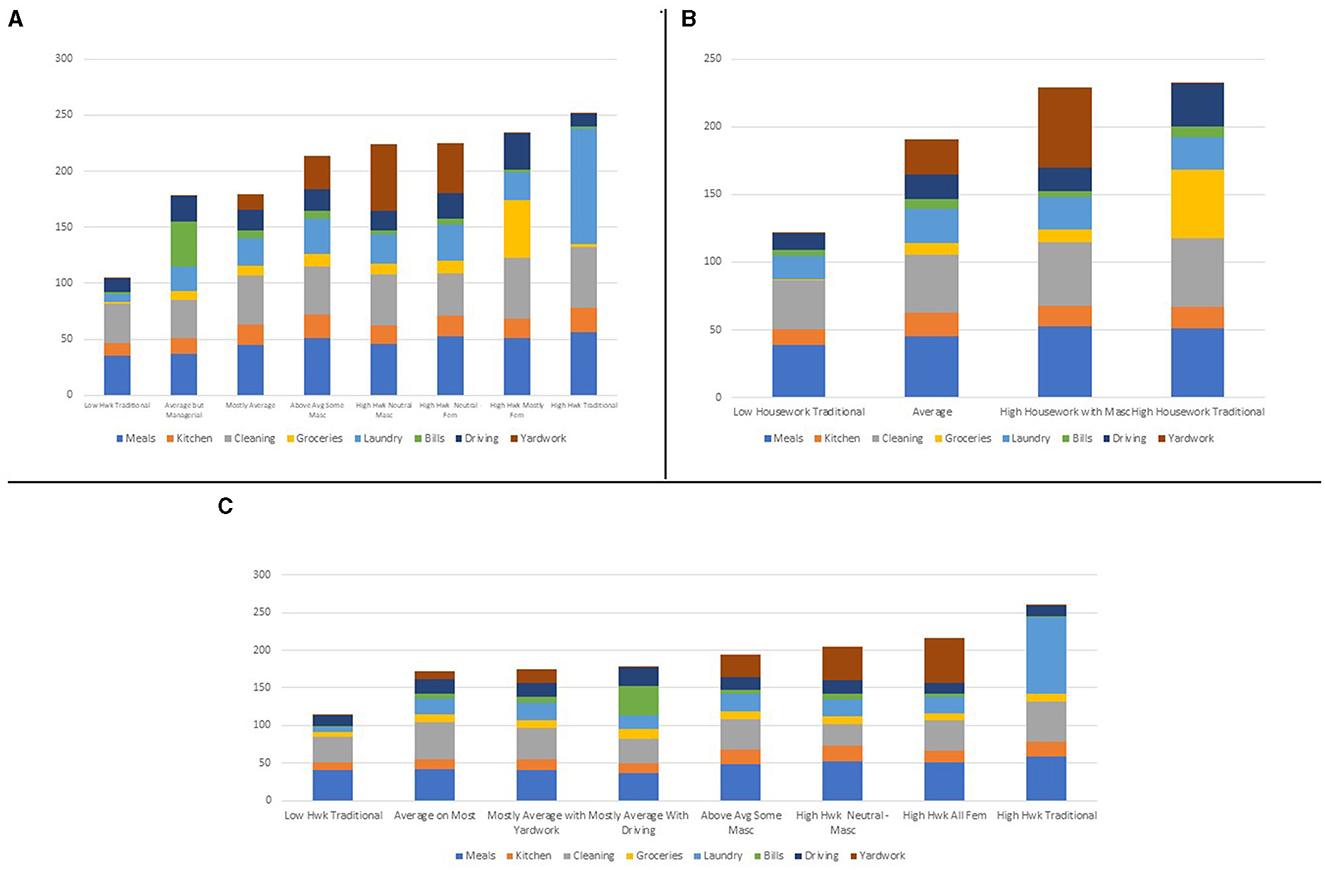

While Table 1 provides an overview of women's housework patterns, Figure 1 depicts women's patterns of housework by task across the three time periods. Women had eight distinct patterns (classes) Pre- and Post-Recession (Panels A and C) while only four patterns (classes) during the Recession (Panel B). As noted in Table 1 and Panel A, the most prevalent pattern of housework was a traditional division, where women performed only routine tasks, albeit spending the least amount of time across all groups. The other seven classes of women during the Pre-Recession period performed substantially more housework than did the most prevalent group (the group I call Low Housework Traditional). The two groups who performed slightly more than the Low Housework Traditional group performed more than one hour more per week of tasks, mostly focused on average amounts of routine work but adding in the managerial tasks or yardwork. All remaining groups during the Pre-Recession period spent approximately four hours or more during the day on housework. These high housework groups varied in the combination of tasks performed, although the High Housework Traditional class spent a lot of time on routine tasks, more time on housework than the Low Housework Traditional class did in total.

Figure 1. Women's housework time by task across three time periods. (A) Women's housework time in minutes: Pre-Recession. (B) Women's housework time in minutes: Recession. (C) Women's housework time in minutes: Post-Recession.

Women on average spent five fewer minutes on housework during the Recession than did women before the Recession. Women's work became less varied during the Recession, perhaps as a response to the external economic changes and constrained opportunities. Not only does Table 1, Figure 1B show that there were only four classes, but the difference between the time spent by those who spent the least (Low Housework Traditional) and most (High Housework Traditional) time on housework was smaller than that same difference Pre-Recession. This is because the Low Housework Traditional women spent about 15 more minutes per day than did their counterparts Pre-Recession and the High Housework Traditional women spent about 20 fewer minutes per day than their Pre-Recession counterparts. Overall, the patterns of the women's task distribution during the Recession reflect two kinds of women: women who focused almost exclusively on the home (Low Housework Traditional) and women who, to differing degrees, engaged with activities outside of the home (the other three classes), as noted by the time spent on grocery shopping, driving, and yardwork that differentiates the Low Housework Traditional class from the other three classes of women during the Recession.

Post-Recession women spent approximately the same amount of time per day on housework as did their counterparts during the recession and six fewer minutes per day than did their Pre-Recession counterparts, as noted in Table 1, Figure 1C. In many ways, however, Post-Recession women were quite similar to Pre-Recession women. The number of distinct patterns of housework tasks increased to Pre-Recession levels, with eight patterns emerging from the data. Interestingly, the Low Housework Traditional class increased in prevalence relative to the Pre-Recession time period and increased in the minutes per day spent on housework. There are only three high housework classes that emerged during the Post-Recession rather than four, with more women clustered around three rather than almost four hours of housework per day. In addition, the High Housework Traditional class performed ~8 min more housework per day and were a larger percentage of the overall group of women, than were their counterparts during the Pre-Recession time period.

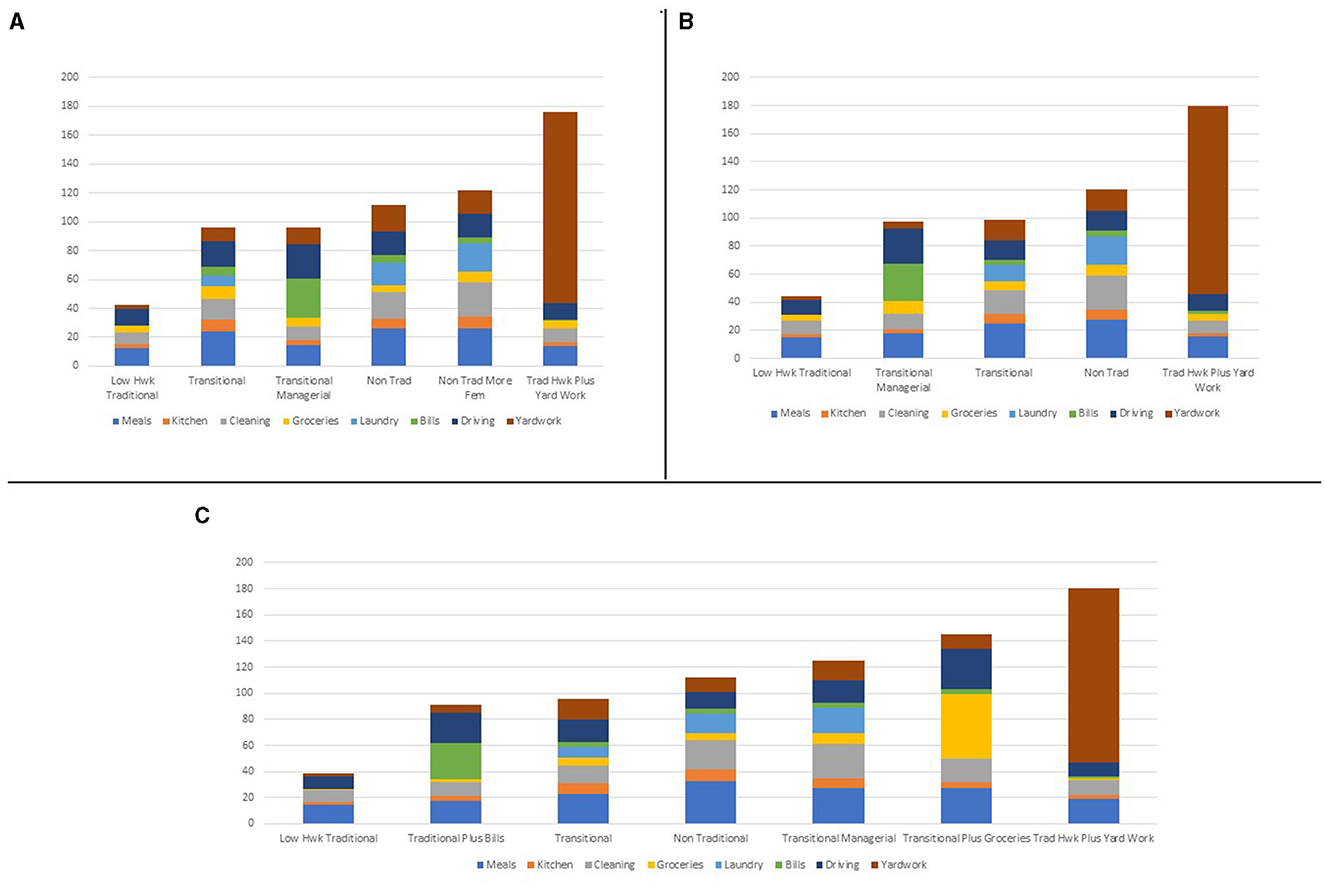

Table 2 provides an overview of men's housework patterns, while Figure 2 depicts men's patterns of housework across the three time periods. Men had six distinct patterns (classes) Pre-Recession (Panel A), five patterns during the Recession (Panel B), and seven patterns after the Recession (Panel C). Traditional and less traditional distributions were seen in all three time periods, with one interesting group with a traditional pattern and high levels of yard work in each time period. However, the most prevalent group across all three time periods were the Low Housework Traditional men. These Low Housework Traditional men were distinctly different from the other men in each time period. Further, within each time period, the men who were not engaged in traditional distribution of time were quite similar to one another overall. As noted above, the Traditional Housework plus Yard Work group is distinct in each time period, with this group only distinguishing themselves from the Low Housework Traditional men by the immense amount of yardwork per day that they performed.

Figure 2. Men's housework time by task across three time periods. (A) Men's housework time in minutes: Pre-Recession. (B) Men's housework time in minutes: Recession. (C) Men's housework time in minutes: Post-Recession.

Also within each time period is a set of classes I call Transitional, named after the transitional group found in Hochschild's (1989) classic monograph on the division of housework. These men perform mostly masculine tasks, but each class adds in some feminine task(s) that distinguishes them from the Low Housework Traditional men. For example, during the Pre-Recession time period, the Transitional men spend more time per day on all of the routine tasks than do their Low Housework Traditional counterparts. During the Recession, Transitional Managerial men performed more “managerial” tasks than did their Low Housework Traditional counterparts, specifically in that they spent more time paying bills and driving. During the Post-Recession time period, the Transitional plus Groceries class performed a substantial amount of time per day on grocery shopping relative to their Low Housework Traditional counterparts.

Unlike women, men performed slightly more housework per day after the Recession than before, although women perform 2.5 times as much housework per day across each time period on average. Post-recession, the Low Housework Traditional men performed less housework per day than did their Pre-Recession counterparts. However, the Low Housework Traditional men performed more minutes per day than did either those in the Pre- (+2 min) or Post-Recession (+6 min) time periods.

Housework is a task performed in all households but is mostly studied as a gendered behavior in multi-person residences. This exploratory analysis examined patterns of housework time among married women, among married men, and between married (though not to each other) women and men in three time periods (before, during, and after the Great Recession).

Using American Time Use Survey data, I examined the extent to which the Great Recession changed patterns in women's and men's housework performance. There was a difference in the distribution of tasks during the Great Recession for both women and men. There were fewer distinct patterns of task distribution for both women and men during the Great Recession than before and after. I suggest that the economic shock placed on households during the Recession may have created more within-sex similarity as women and men structured their home life in response to the constrained opportunities in the public sphere, an explanation consistent with time availability approaches.

Women's time distribution before and after the Recession was more similar than men's time distribution, suggesting that the Great Recession likely had more of a social change effect on men than on women. After the economic shock, women's patterns were quite similar to the Pre-Recession time period. Men's patterns reflected more variability, more feminine tasks, and more distinct groups. However, one point did not change (low housework). Traditional men, men engaging in only traditionally masculine tasks, were the most prevalent and distinctly different from other men across all three time periods. While the Great Recession may have led some men to become less traditional, the path of least resistance remains a traditionally masculine performance of very little housework.

Besen-Cassino (2019) argues that the Great Recession likely affected men's housework participation because their economic insecurity was perceived as a threat to their masculinity. This research found that men's housework became less traditionally gendered, on average, after the Great Recession. Kidane (2019) found that immigrant Hispanic men performed more housework than did other men during and after the Recession, suggesting a specifically racialized interpretation of masculinity that may be threatened by the economic uncertainty that surrounded the Recession. This is an important vein of inquiry that will need to be pursued. Additional lines of inquiry include demographic correlates of the patterns within each time period that extend beyond race/ethnicity. In addition, physical task performance is not the only measure of housework (e.g., the cognitive dimension—see Daminger, 2019, for more details). Other scholars may seek to uncover whether a composite of all components of housework follow the same patterns documented herein that were found before, during, and after the Great Recession.

The contribution of this article is to uncover, through a unique descriptive analysis, how gendered patterns of housework tasks themselves shift in response to the Great Recession. Given the attention being paid to gendered housework performance during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is encouraged that future authors evaluate the extent to which patterns of housework tasks also shifted as a result of remote work and job loss during the pandemic. The intersection of economic disruption and cultural norms that occurred within the United States in the Great Recession suggest that it will take something like a global pandemic to move the needle on prevalent patterns of the performance of housework that disproportionately burden women with routine tasks.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.bls.gov/tus/data.htm.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2023.1153321/full#supplementary-material

Arrighi, B.A., and Maume, D. J. (2000). Workplace subordination and men's avoidance of housework. J. Fam. Issues 21, 464–487. doi: 10.1177/019251300021004003

Berik, G., and Kongar, E. (2013). Time allocation of married mothers and fathers in hard times: The 2007-09 US recession. Fem. Econ. 19, 208–237. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2013.798425

Besen-Cassino, Y. (2019). Gender threat and men in the post-trump world: the effects of a changing economy on men's housework. Men Masc. 22, 44–52. doi: 10.1177/1097184X18805549

Besen-Cassino, Y., and Cassino, D. (2014). Division of house chores and the curious case of cooking: The effects of earning inequality on house chores among dual-earner couples. About Gend. 3, 25–53. doi: 10.15167/2279-5057/ag.2014.3.6.176

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., and Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forc. 91, 55–63. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos120

Boushey, H. (2011). Not working: Unemployment Among Married Couples. Unemployment Continues to Plague Families in Today's Tough Job Market. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Bureau of the Census. (2019). American Time Use Survey. Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/tus/home.htm (accessed September 12, 2023).

Christensen, K. (2015). He-cession? She-cession? The gendered impact of the Great Recession in the United States. Rev. Radical Polit. Econ. 47, 368–388. doi: 10.1177/0486613414542771

Daminger, A. (2019). The cognitive dimension of household labor. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 609–633. doi: 10.1177/0003122419859007

Davis, S. N., and Greenstein, T. N. (2020). Households and work in their economic contexts: State-level variations in gendered housework performance before, during, and after the great recession. J. Occupat. Sci. 27, 390–404. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2020.1741430

Goodman, C. J., and Mance, S. M. (2011). “Employment loss and the 2007–09 recession: an overview,” in Monthly Labor Review. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Gough, M., and Killewald, A. (2010). Gender, Job Loss, and Housework: The Time Availability Hypothesis Revisited. Ann Arbor: Population Studies Center.

Gough, M., and Killewald, A. (2011). Unemployment in families: the case of housework. J. Marriage Fam. 73, 1085–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00867.x

Greenstein, T. N. (2000). Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: a replication and extension. J. Marriage Fam. 62, 322–335.

Hofferth, S. L., Flood, S. M., and Sobek, M. (2013). American time use survey data extract system: Version 2.4 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Maryland Population Research Center, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, and Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota. Available online at: http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS95587 (accessed September 12, 2023).

Hook, J. L. (2017). Women's housework: New tests of time and money. J. Marriage Fam. 79, 179–198. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12351

Khitarishvili, T., and Kim, K. (2014). “The Great Recession and unpaid work time in the United States: Does poverty matter?,” in Levy Economics Institute, Working Paper No. 806. (Annandale-On-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2444768

Kidane, D. (2019). Impact of the great recession on time use: a comparative analysis among demographic groups. Empi. Econ. Rev. 9, 103–119.

Kochhar, R. (2011). In Two Years of Economic Recovery, Women Lost Jobs, Men Found Them. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/07/06/two-years-of-economic-recovery-women-lose-jobs-men-find-them/ (accessed September 12, 2023).

Kolpashnikova, K., and Kan, M. (2021). Gender gap in housework time: how much do individual resources actually matter? Social Sci. J. doi: 10.1080/03623319.2021.1997079

Krantz-Kent, R. (2009). Measuring time spent in unpaid household work: results from the American Time Use Survey. Monthly Labor Rev. 132, 46–59.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User's Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén

Ruppanner, L., Maltby, B., Hewitt, B., and Maume, D. (2021). Parents' sleep across weekdays and weekends: the influence of work, housework, and childcare time. J. Fam. Issues. doi: 10.1177/0192513X211017932

Keywords: Great Recession, housework, domestic labor, household chores, LPA

Citation: Davis SN (2023) Patterns of housework performance in the United States before, during, and after the Great Recession. Front. Sociol. 8:1153321. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1153321

Received: 29 January 2023; Accepted: 17 August 2023;

Published: 22 September 2023.

Edited by:

Marisa Matias, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Cheryl Elman, Duke University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Davis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shannon N. Davis, c2Rhdmlzb0BnbXUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.