95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sociol. , 28 July 2022

Sec. Gender, Sex and Sexualities

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.966878

This article is part of the Research Topic Social Media and Political Participation: Unpacking the Role of Social Media in Contemporary Politics View all 10 articles

Social media has become a viable platform for political participation in issues related to gender, especially among the youth. Evidence suggests that gender and sexual identities, digital access, and skills foster political participation in social media. This study sought to determine the predictive relationship of gender, digital profile, and social media competence with social media political participation in gender issues (SMPP-GI) among young Filipino netizens through the lenses of social identity theory and resource model of political participation. A total of 1,090 college netizens aged 18–30 years old participated in this cross-sectional study. An online survey was used to collect data. The respondents reported low to moderate levels of SMPP-GI. Females and non-cisheterosexual respondents report higher scores in certain types of SMPP-GI. Respondents using more social media sites have higher levels of latent and counter engagement SMPP-GI. Among the four domains of social media competence, content generation significantly predicted all types of SMPP-GI, while content interpretation and anticipatory reflection were significantly linked with at least one type of engagement.

Like other aspects and events of life in the contemporary world, social movements toward social justice have also found their way into cyberspace. With around five billion people using the internet worldwide (Statista Research Department, 2021a), the pervasiveness of social media has shaped citizens' political participation regarding contemporary social issues (Murthy, 2018). We suspect that social media political participation (SMPP) would have increased during the time of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, when lockdowns, and social distancing restrictions have shifted most social interactions online, causing an increased user growth rate in social media across the globe in 2020 (Statista Research Department, 2021a). A wealth of research has indicated the positive influence of social media use on political participation (Dimitrova and Bystrom, 2013; Kim and Khang, 2014; Boulianne, 2015; Lee and Xenos, 2020), especially among the youth (Ida and Saud, 2020). In terms of focus and context of SMPP, studies have examined generalized forms of online political participation (Shehzad et al., 2021), and specific issues such as election (Dimitrova and Bystrom, 2013; Yang and DeHart, 2016), racism (Ince et al., 2017) and gender inequality (Quan-Haase et al., 2021).

Our present study specifically focuses on social media participation in gender issues (SMPP-GI) in the Philippines. Based on the 2020–2021 summary report on the state of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to gender equality, the country appears to be in a good position among its Southeast Asian (ASEAN) counterparts. The Philippines is among the countries with a lower proportion of women involved in domestic violence, child marriage, and gender disparities in public positions (U. N. Women, 2021). However, the current regime has been characterized by misogynistic posturing, chauvinist populism, and sexist remarks by President Rodrigo Duterte, which could potentially undermine developmental efforts to achieve a more gender-equal nation (Go, 2019; Parmanand, 2020). The Philippines dropped from the 5th spot in 2013 to 16th in 2020 against other countries in the Global Gender Gap Index (Mercurio, 2019). This may be attributed to the lack of prioritization of women, children, and gender policies during the Duterte regime (Abad, 2020).

Social media has become a viable platform for Filipinos in terms of political participation in gender issues. The Philippines has been dubbed the “Social Media Capital of the World,” where an average internet user spends almost 4 h per day on social media during the pandemic year 2020 (Ichimura, 2020). Around 30 percent of these users are within the youth bracket (Statista Research Department, 2021b). Feminist movements have emerged on social media such as #BabaeAko (I am a Woman), which was a push back against President Duterte's comment against a woman occupying the Chief Justice position (Haynes, 2018), and #HijaAko (I am a Daughter), which was a counter-movement against the prevalent victim-blaming of women who were raped and sexually harassed (Foundation for Media Alternatives, 2020). Likewise, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, plus (LGBTQ+) movements have found an alternative space online, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of in-person June Pride Marches in 2020 and 2021, LGBTQ+ groups have implemented social media-mediated campaigns, events, lectures, and performances for gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights (Adel, 2021).

Evidence has underscored the power of social media political participation in promoting offline political participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Strömbäck et al., 2018) and stimulating positive social change toward gender equality (Seibicke, 2017). Given the current status of gender and development in the Philippines, we assert the relevance of examining the factors influencing SMPP-GI among Filipino youth, who are currently underrepresented in this area of study. We appealed to the perspectives of social identity theory and resource model in identifying possible factors that influence SMPP-GI. This present study aims to test the predictive relationship of gender, digital profile, and social media competence, with social media political participation in gender issues among young Filipino netizens.

Van Deth (2014) characterizes political participation as any of the following voluntary, non-professional activities: activities within the locus of politics, government, or state; activities that target politics, social problems, or communities; or non-political activities that have political motivations. A meta-analysis of earlier social-media-related studies (Boulianne, 2015) considered campaigning, protesting, civic engagement, and the combinations of any of the three as political participation. Other scholars argued that more passive behaviors such as slacktivism should be considered SMPP (Piat, 2019; Madison and Klang, 2020). In recent years, political participation on social media had been attributed to “wokeness,” which refers to awareness of and expressions against social injustices (Allen, 2020). Being woke (or “mulat” in Filipino) has been linked to positive (e.g., sociopolitical awareness; Caldera, 2018) and negative attributes (e.g., conflict-inducing and being un-Christian; Strachan, 2021). For this present study, we intend to cover more diverse forms of behaviors to signify SMPP, unlike many of the previous studies that examined only particular behaviors related to SMPP (Boulianne, 2015). Hence, we appeal to the social media political participation framework developed by Waeterloos et al. (2021), who forwarded a more encompassing understanding of SMPP, including passive and active forms of political engagement. Waeterloos et al. (2021) suggested four types of SMPP. First is latent engagement, which refers to the consumption of information on social or political issues, as demonstrated in previous studies (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Yamamoto and Nah, 2018). The second is counter engagement, which includes performing uncivil behaviors, such as misusing private information (George and Leidner, 2019) and negative commenting (Khan et al., 2019), for social and political causes. The third is follower engagement, which involves participation and promotion of the content and activities of other social media users, also coined as metavoicing (Albu and Etter, 2018; George and Leidner, 2019). Fourth is expressive engagement, which refers to the social media actions and posts that were instigated by users themselves—constructs commonly explored by recent research on gender-related SMPP (Ciszek, 2017; Quan-Haase et al., 2021). Taking these dimensions together, this framework for SMPP would be able to cater to both positive and negative aspects of wokeness.

Social identity theory posits that an aspect of an individual's self-concept is constituted by one's membership in groups, and such identity motivates political behavior (Kalin and Sambanis, 2018). Social media provides affordances for political participation and activism such as page following, group membership, and hashtags that allow people to signify their social identity (Zappavigna, 2015; George and Leidner, 2019). Individuals desire to improve their group's standing in society by maintaining the group's highly valued attributes and/or fighting to rectify the group's negative image (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). The dominance of patriarchy and cisheterosexism in society breeds conditions that marginalize women and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and other non-cisheterosexual (LGBTQ+) identifying persons (Cravens, 2020; Fitzgerald and Grossman, 2020). These conditions can stimulate political participation among members of these oppressed gender categories, which in turn, enhance the group's collective identity, and strengthen the members' sense of personal identity (Vestergren et al., 2017; Cravens, 2020; Foster et al., 2021). Since our present study examines SMPP specific to gender issues, we chose gender as our first explanatory variable of interest. The current body of research on the gendered differences in online political participation points more to males (Vochocová et al., 2016; Quaranta and Dotti Sani, 2018; Ahmed and Madrid-Morales, 2021) than females (Yang and DeHart, 2016). However, the context of the political participation measured in these studies was not specific to gender-issues. Studies that did examine SMPP related to gender issues did not, however, attempt to quantitatively differentiate females from males, and/or cisheterosexual identities from LGBTQ+ counterparts (Jones and Brewster, 2017; Foster et al., 2021; Quan-Haase et al., 2021; Thompson and Turnbull-Dugarte, 2021). Our first research objective attempts to test how SMPP-GI is influenced by gender, which covers sex assigned at birth, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Hence, we hypothesize:

H1: Females and respondents who identify as LGBTQ+ will demonstrate higher SMPP-GI.

The resource model of political participation states that the extent of political participation is shaped by one's available resources, which may include time, money, and other assets (Brady et al., 1995). In the era of new media, access to social media has become an invaluable resource for various forms of political participation. Access to tangible digital tools is a prerequisite to maximizing the affordances of social media to facilitate political participation. We coined these prerequisites to SMPP as digital profile, which includes having active accounts on one or more social media sites (Effing et al., 2011; Abdu et al., 2017; Albu and Etter, 2018), ownership of one or more gadgets (Schradie, 2011; Kim et al., 2016; Lin and Chiang, 2017), and internet connection (Wang et al., 2018; Shehzad et al., 2021). For the second research objective of the study, we will determine how the respondents' digital profile influences their SMPP-GI. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H2: Respondents who are active on more social media sites, own more gadgets, and have access to better internet quality will demonstrate higher SMPP-GI.

The resource model also suggests that aside from tangible tools, skills are also resources that contribute to political participation (Brady et al., 1995). In the online realm, Internet skills have been indicated as facilitators of youth political participation (Wang et al., 2018). Various measures of social media ability have been linked to better political participation, such as social media self-efficacy (Omotayo and Folorunso, 2020; Hoffmann and Lutz, 2021), prosumption, and information literacy (Yamamoto and Nah, 2018; Tugtekin and Koc, 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) and creative expressions (Yu and Oh, 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). For this present study, we operationalized SMPP-related skills and abilities as social media competence (Zhu et al., 2020), which includes four domains, such as technical usability, content interpretation, content generation, and anticipatory reflection. These attributes are aspects of being what is colloquially known as “social media savvy” (Miller, 2018). For our third research objective, we will test the predictive relationship between social media competence and SMPP-GI. Hence, hypothesize:

H3: Respondents with higher social media competence will demonstrate higher SMPP-GI.

This study utilized a cross-sectional design. The target participants are Filipino netizens who are aged 18–30 years old, which is the bracket considered as “youth” by the National Youth Commission (2021). We were interested in college-based Filipino youth as the sample for this study because despite being a large sector of the population, they face cultural barriers to offline political participation in the country; hence, the viability of social media as their main platform for political engagement (International IDEA., 2020). A total of 1,090 conveniently sampled respondents qualified for the study. Majority of the respondents are 21 years old (μ = 20.108 ± 1.802), from North and Central Luzon (n = 550, 50.459%), and enrolled in STEM degree programs (n = 382, 35.046%).

The protocol of the study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and has been granted administrative clearance for the ethical conduct of research by the host department of the University of the researchers. Our data was collected through a Google Forms survey. Upon approval, we created a Facebook Page where we posted the survey link, together with a poster that indicated a message of invitation and inclusion criteria. For greater reach, we boosted the post and targeted the accounts geolocated in the Philippines and with the age range of interest. The survey collected responses during the first 3 weeks of August 2021. Informed consent was secured digitally. The first page of the online survey presented the details of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the rights of the respondents. Privacy and confidentiality were observed in handling the data. The access to the digital data was restricted to us, the researchers.

For this study, the predictor variables of interest are gender, digital profile, and social media competence, while the outcome variable is social media political participation in gender issues.

Two sub-variables were used to describe the gender of the respondents. First, they were asked about their sex assigned at birth (male = 1, female = 0). Second, they were asked about their sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). For sexual orientation, they were asked whether they identify as heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, queer, and others. For gender identity, they were asked whether they identify as cisgender or transgender. A “prefer not to disclose” option was provided for both sexual orientation and gender identity. For purposes of categorizing SOGI for inferential analysis, those who identify as both cisgender and heterosexual were grouped as “cisheterosexual”; those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, queer, and/or other non-cisheterosexual identities were grouped as “LGBTQ+”; and those who indicated “prefer not to disclose” in either of sexual orientation or gender identity were grouped as “non-disclosed SOGI.”

Three sub-variables were measured to characterize the digital profile of the respondents. Through a checklist, they were asked about the different social media sites they used (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.), and the different gadgets they owned (e.g., smartphones, laptops, tablets, etc.). An option for “others” was provided for each. The ticks for both indicators were added; the sum of checked items, plus those which were included in “others,” were the values for each. The third sub-variable is internet quality, wherein they were asked to rate from 1 (very bad) to 7 (very good).

Developed by Zhu et al. (2020), SMCS-CS is a 28-item scale that measures social media competence through four domains: technical usability, content interpretation, content generation, and anticipatory reflection. It is measured through a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). This scale has been found to have an acceptable factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.97). A sample item is “I can develop original, visual and textual social media content.”

Developed by Waeterloos et al. (2021), SMPP is a 21-item scale that measures four types of political engagement: latent, counter, follower, and expressive engagement, each with acceptable Cronbach alpha values (0.80–0.91). The respondent answers through a six-point scale (1 = never; 5 = very often), with the time reference of within the last 6 months. The sociopolitical issue can be specified on the items of this scale. To examine the specific context of the outcome variable of the study present study, “political issues” were replaced with “gender issues,” thus our coining of SMPP-GI. This scale has an acceptable factor structure, item convergent validity, and overall internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.88). A sample item is “I commented on something concerning gender issues in a way it was publicly visible.”

The dataset was rid of unqualified entries and coded accordingly before formal analysis. Mean and standard deviation was used to describe continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression analysis (enter method) was used to determine the significant predictors of the four types of SMPP-GI. Bootstrapping (n = 5,000) was used to address possible non-normality (Pek et al., 2018). The significance level was set at 0.05 level. JASP version 0.14.1 was used for the statistical analyses.

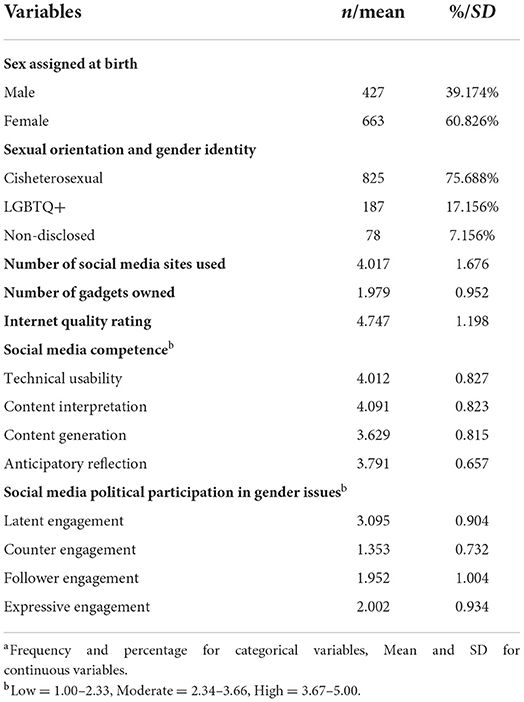

Table 1 shows the descriptive results of the key variables in the study. Majority of the respondents (N = 1,090) are female (n = 663, 60.826%) and cisheterosexual (n = 825, 75.688%). There are 187 (17.156%) respondents who identify as LGBTQ+, while 78 (7.156%) did not disclose their sexual and/or gender identities. In terms of digital profile, the respondents used an average of four different social media sites (μ = 4.017 ± 1.676), two gadgets (μ = 1.979 ± 0.952), and reported having moderate level quality of internet (μ = 4.747 ± 1.198 out of 7).

Table 1. Gender, digital profile, social media competence, and political participation in gender issues (N = 1,090)a.

The respondents of the study reported high social media competence in terms of technical usability (μ = 4.012 ± 0.827), content interpretation (μ = 4.091 ± 0.832), and anticipatory reflection (μ = 3.791 ± 0.657). On the other hand, the respondents demonstrated moderate competence in terms of content generation (μ = 3.629 ± 0.815).

In terms of SMPP-GI, the respondents reported low levels of counter (μ = 1.353 ± 0.732), follower (μ = 1.952 ± 1.004), and expressive (μ = 2.002 ± 0.934) engagement in gender issues. Meanwhile, the respondents exhibited moderate levels of latent engagement (3.095 ± 0.904).

Table 2 shows the results of the multiple linear regression tests to determine the significant gender, digital, and social media competence predictors of social media participation in gender issues. Four bootstrapped models (n = 5,000) were tested, one for each type of SMPP-GI. Model 1 significantly predicted latent engagement (F = 27.263, p < 0.001) and explained 20.3% of its variance. Specifically, variables that significantly predicted latent engagement were sex (B = −0.278, p < 0.001), LGBTQ+ identity (B = 0.628, p < 0.001), non-disclosed SOGI identity (B = 0.417, p < 0.001), number of social media sites used (B = 0.059, p < 0.001), and content generation (B = 0.223, p < 0.001). Female respondents, with LGBTQ+ or non-disclosed SOGI identity, who use more social media sites and have higher scores in content generation demonstrate higher levels of latent engagement SMPP-GI.

Counter engagement was significantly predicted by Model 2 (F = 8.134, p < 0.001) and explained 7% of its variance. Determinants that yielded significant estimates include non-disclosed SOGI identity (B = 0.182, p = 0.027), number of social media sites (B = −0.029, p = 0.041), content interpretation (B = −0.143, p = 0.006), content generation (B = 0.237, p < 0.001) and anticipatory reflection (B = −0.150, p = 0.005). Higher counter engagement levels were observed among respondents with non-disclosed SOGI identity, lesser social media sites, content interpretation and anticipatory reflection, and higher content generation.

Model 3 significantly predicted follower engagement (F = 15.861, p < 0.001) and explained 12.8% of its variance. Significant predictors include sex (B = −0.187, p < 0.002), LGBTQ+ identity (B = 0.565, p < 0.001), non-disclosed SOGI identity (B = 0.327, p = 0.004), and content generation (B = 0.402, p < 0.001). Females with LGBTQ+ and/or non-disclosed SOGI identities with higher scores in content generation demonstrated significantly higher follower engagement.

Finally, Model 4 significantly predicted expressive engagement (F = 14.710, p < 0.001) and explained 12% of its variance. Specific variables that yielded significant estimates include LGBTQ+ identity (B = 0.489, p < 0.001), non-disclosed SOGI identity (B = 0.324, p = 0.002), content generation (B = 0.398, p < 0.001), and anticipatory reflection (B = −0.161, p = 0.016). Expressive engagement was observed to be higher among respondents with LGBTQ+ and non-disclosed SOGI identities who have higher levels of content generation, and lower levels of anticipatory reflection.

Our present study sought to determine the predictive relationship between gender, digital profile, and social media competence, and SMPP-GI among young Filipino netizens. Our investigation contributes to online political participation scholarship by testing the potential of social identity and resource perspectives in understanding and predicting SMPP. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study conducted in ASEAN that quantitatively examined gender-related political participation among youth in the context of social media, and competencies related to its use. Our findings suggest that college netizens have low to moderate levels of SMPP-GI. Similarly, Bawan et al. (2017) had previously noted low online political and governance participation in a sample of Filipino professional students.

Our findings suggest that females demonstrate higher latent and follower engagement SMPP-GI, which confirms previous research that women politically engage in gender issues to enact their gender identity ( Chante'Tanksley,2019; Foster et al., 2021). Meanwhile, LGBTQ+ individuals report higher latent, follower, and expressive engagement SMPP-GI. The present results show that social identity truly fosters political engagement, and supports earlier literature that demonstrates immersive involvement in various social media movements among females and/or LGBTQI+, who are detrimentally affected by patriarchal and cisheterosexist structures that maintain gender inequality (Shevtsova, 2017; Stornaiuolo and Thomas, 2017; Liao, 2019; Hou, 2020). These partially confirm the social identity hypothesis on SMPP-GI.

Interestingly, those who chose not to disclose their sexual and/or gender identities demonstrated higher levels in all types of SMPP-GI, which contrasts with previous evidence demonstrating the active engagement of “out” individuals in gender-related activism (Swank and Fahs, 2013). This finding highlights the nuances of how social identity is enacted in political participation, which may not necessarily involve publicizing one's identity. Concealment of one's potentially marginalized SOGI may be a strategy to protect oneself from further stigmatization and othering (Goffman, 2009) when one engages in political activities online. Non-disclosure can influence the reporting of socially polarizing behaviors, as noted in previous research (e.g., Warner et al., 2020).

Our resource model hypothesis specific to digital profile was partially confirmed, as only one of the indicators yielded significance. Number of social media sites used predicted certain types of SMPP-GI. Specifically, college netizens who use more social media sites report higher levels of latent engagement. This finding emphasizes how the increasingly multi-platform nature of activism can enhance visibility and information consumption of social issues, confirming previous evidence among civil society organizations (Albu and Etter, 2018).

On the other hand, our current findings suggest that college netizens who use lesser social media sites are more likely to practice counter engagement in the name of gender issues. Since the nature and audience of each social media site differ (Albu and Etter, 2018), being in only one site can increase the likelihood of forming an “echo chamber” type social network, which has been noted to exhibit destructive behaviors, such as rumor spreading (Choi et al., 2020).

Our hypothesis on social media competence as a resource that facilitates SMPP-GI is partially confirmed as well, with some SMCS-CS domains demonstrating a significant relationship with certain types of political participation. Among the four domains of social media competence, content generation emerged to be a significant positive predictor of all types of SMPP-GI. Previous research has indicated the positive correlation of functional and critical prosumption to democratic tendencies in social media (Tugtekin and Koc, 2020). Many studies on social media political participation on various issues have highlighted the importance of content creation to engage more people in the cause (Yamamoto and Nah, 2018; Yu and Oh, 2018; Zhu et al., 2019; Tugtekin and Koc, 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020).

Our findings suggest that anticipatory reflection negatively predicted counter engagement SMPP-GI. Related to this, Zhu et al. (2021) suggests that individuals with lower anticipatory reflection have lesser information society responsibility, which could be linked to counter engagement behaviors. Moreover, it is interesting to note that in our present study, college netizens with high anticipatory reflection are less likely to perform expressive engagement SMPP-GI. We suspect that these students who have increased anticipatory reflection, despite their passion for gender issues, could foresee the possible social consequences of being publicly vocal regarding these issues, such as backlash and loss of friendships, especially from those who have differing opinions about gender-related rights. This fear can make them reluctant to openly participating, as indicated in previous studies (Gustafsson, 2012; Chan, 2018).

Lastly, college netizens who report lower levels of content interpretation have higher counter engagement SMPP-GI. Content interpretation has been linked to information literacy (Zhu et al., 2021). Related to this, Tugtekin and Koc (2020) have suggested that individuals with decreased critical consumption of social media have lower democratic tendencies, which we suspect may result in acts of counter engagement.

Compared to earlier online political participation studies done among students in the Philippines (e.g., Bawan et al., 2017), our study has a larger sample size and a wider reach. However, it must be cautiously noted that ours is a convenient sample, and Visayas and Mindanao Island groups (South of the Philippines) are not adequately represented. Moreover, the cross-sectional design of the study may decrease the generalizability of the results. Some of the models we tested had quite modest explanatory power (7–20%). It must be noted that political participation is fluid and influenced by the gender issues that are existing during the time of data collection. Future studies can replicate the study on a randomized, representative sample, and include other possible explanatory variables based on other perspectives of political participation. Despite these limitations, our study remains to be the first of its kind in the country and can help stimulate further investigation on SMPP regarding gender and other social issues.

Our study highlights the current state of social media political participation in the context of gender issues among the Filipino youth, which we have noted to be low to moderate. Youths who are members of gender-disadvantaged categories, such as females and LGBTQ+, demonstrate higher engagement in certain types of SMPP-GI. Truly, the personal is political, and those who are affected by gender-based concerns are more likely to be involved in movements related to them. We also highlight the nuanced nature of social identity in the context of political participation, wherein privatizing and concealing one's gender and/or sexual identity (arguably to protect oneself from stigmatization) can potentially promote higher political engagement in gender issues, as seen in the case of our respondents with non-disclosed SOGI. Hence, designing and implementing programs to elicit effective political participation for gender-related causes among the youth must consider all members across the gender and sexuality spectrum, and include initiatives to protect those who choose not to disclose their identities while they meaningfully engage in these online movements. Future studies can further explore these potential intertwined roles of gender identity and performativity in SMPP-GI.

This present study also identified specific digital affordances (number of active social media sites) and social media competencies that can serve as resources to facilitate SMPP-GI. Content generation emerged to be an important competence that bolsters all types of political engagement. We recommend the development of initiatives that build the capability of the youth in creating engaging content for different social media sites. Future studies can explore the influence of specific content generated on SMPP-GI. Also, campaigns to improve information literacy toward better anticipatory reflection and content interpretation may be implemented to translate counter engagement to less abrasive forms of political engagement. We hope the findings inform stakeholders in social media to promote a more critical, informative, inclusive, and healthier woke culture that advocates gender equality.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study protocol was granted administrative clearance for ethical conduct of research by the Department of Sociology and Behavioral Sciences of DLSU (2021-08-09). The respondents provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. National and local policies on data privacy were observed during data collection and storage.

JD and BA: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, formal analysis, and writing—original draft. JC: conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing—final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Open access publication will be paid through the publication grant of De La Salle University—Science Foundation.

We would like to thank the college netizens who participated in this survey research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abad, M. (2020). LIST: Women, Children, Gender Policies Left Behind During Duterte's Term. Rappler. Available online at: https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/list-women-children-gender-policies-left-behind-during-duterte-term

Abdu, S. D., Mohamad, B., and Muda, S. (2017). “Youth online political participation: The role of Facebook use, interactivity, quality information and political interest,” in SHS Web of Conferences, Vol. 33 (Bali), 1–10. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20173300080

Adel, R. (2021). SulongVaklash: Rundown of Pride Month Events. Interaksyon. Available online at: https://interaksyon.philstar.com/trends-spotlights/2021/06/04/193001/sulongvaklash-rundown-of-pride-month-events/

Ahmed, S., and Madrid-Morales, D. (2021). Is it still a man's world? Social media news use and gender inequality in online political engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24, 381–399. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1851387

Albu, O. B., and Etter, M. A. (2018). “How social media mashups enable and constrain online activism of civil society organizations,” in Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change, ed J. Servaes (Singapore: Springer), 891–909. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8_80-1

Allen, A. (2020). On Being Woke and Knowing Injustice: Scale Development and Psychological and Political Implications. (Publication no. 2607) [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Connecticut] Available online at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/2607

Bawan, O. M., Marcos, M. I. P., and Gabriel, A. G. (2017). E-participation of selected professional students in the governance of Cabanatuan City in the Philippines. Open J. Soc. Sci. 5, 126–139. doi: 10.4236/jss.2017.512010

Boulianne, S. (2015). Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of current research. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 524–538. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

Brady, H. E., Verba, S., and Schlozman, K. L. (1995). Beyond SES: a resource model of political participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89, 271–294. doi: 10.2307/2082425

Caldera, A. (2018). Woke pedagogy: a framework for teaching and learning. Divers. Soc. Justice Educ. Lead. 2, 1–11. Available online at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/dsjel/vol2/iss3/1

Chan, M. (2018). Reluctance to talk about politics in face-to-face and Facebook settings: examining the impact of fear of isolation, willingness to self-censor, and peer network characteristics. Mass Commun. Soc. 21, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2017.1358819

Chante'Tanksley, T. (2019). Race, Education and# BlackLivesMatter: How Social Media Activism Shapes the Educational Experiences of Black College-Age Women (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles. Available online at: https://escholarship.org/content/qt5br7z2n6/qt5br7z2n6_noSplash_2c6c77e0dd246383a3ea1b095455d21f.pdf?t=pt4yfp

Choi, D., Chun, S., Oh, H., and Han, J. (2020). Rumor propagation is amplified by echo chambers in social media. Sci. Rep. 10:310. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57272-3

Ciszek, E. (2017). Public relations, activism and identity: a cultural-economic examination of contemporary LGBT activism. Public Relat. Rev. 43, 809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.01.005

Cravens, R. G. (2020). The tipping point: examining the effects of heterosexist and racist stigma on political participation. Soc. Polit. 28, 1185–1212. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxaa009

Dimitrova, D. V., and Bystrom, D. (2013). The effects of social media on political participation and candidate image evaluations in the 2012 Iowa caucuses. Am. Behav. Sci. 57, 1568–1583. doi: 10.1177/0002764213489011

Effing, R., Van Hillegersberg, J., and Huibers, T. (2011). “Social media and political participation: are Facebook, Twitter and YouTube democratizing our political systems?” in International Conference on Electronic Participation (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 25–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23333-3_3

Fitzgerald, K. J., and Grossman, K. L. (2020). Sociology of Sexualities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Foster, M. D., Tassone, A., and Matheson, K. (2021). Tweeting about sexism motivates further activism: a social identity perspective. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 741–764. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12431

Foundation for Media Alternatives (2020). FMA: HijaAko and What the Current Data Map on Online Gender-Based Violence in the Philippines is Telling Us. Association for Progressive Communications. Available online at: https://www.apc.org/en/news/fma-hijaako-and-what-current-data-map-online-gender-based-violence-philippines-telling-us

George, J. J., and Leidner, D. E. (2019). From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Inf. Organ. 29:100249. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Jung, N., and Valenzuela, S. (2012). Social media use for news and individuals' social capital, civic engagement and political participation. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 17, 319–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x

Go, M. G. (2019). Sexism is president's power tool: duterte is using violent language and threats against journalists, Rappler's news editor explains. Index Censorship 48, 33–35. doi: 10.1177/0306422019895720

Gustafsson, N. (2012). The subtle nature of Facebook politics: Swedish social network site users and political participation. N. Media Soc. 14, 1111–1127. doi: 10.1177/1461444812439551

Haynes, S. (2018). Women in the Philippines Have Had Enough of President Duterte's 'Macho' Leadership. Time. Available online at: https://time.com/5345552/duterte-philippines-sexism-sona-women/

Hoffmann, C. P., and Lutz, C. (2021). Digital divides in political participation: the mediating role of social media self-efficacy and privacy concerns. Policy Internet 13, 6–29. doi: 10.1002/poi3.225

Hou, L. (2020). Rewriting “the personal is political”: young women's digital activism and new feminist politics in China. Inter Asia Cult. Stud. 21, 337–355. doi: 10.1080/14649373.2020.1796352

Ichimura, A. (2020). Filipinos Lead the World in Social Media 'Addiction': Social Media Addiction? Or Just Slow Internet? Esquire. Available online at: https://www.esquiremag.ph/money/industry/filipinos-social-media-addiction.

Ida, R., and Saud, M. (2020). An empirical analysis of social media usage, political learning and participation among youth: a comparative study of Indonesia and Pakistan. Qual. Quant. 54, 1285–1297. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-00985-9

Ince, J., Rojas, F., and Davis, C. A. (2017). The social media response to Black Lives Matter: how Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethnic Racial Stud. 40, 1814–1830. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1334931

International IDEA. (2020). Democracy Talks in Manila – the Role of Youth Voices in Philippine. Democracy Talks in Manila – The Role of Youth Voices in Philippine Democracy | International IDEA.Available online at: https://www.idea.int/news-media/events/democracy-talks-manila-%E2%80%93-role-youth-voices-philippine-democracy

Jones, K. N., and Brewster, M. E. (2017). From awareness to action: Examining predictors of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activism for heterosexual people. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 87, 680–689. doi: 10.1037/ort0000219

Kalin, M., and Sambanis, N. (2018). How to think about social identity. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 239–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042016-024408

Khan, M. Y., Javeed, A., Khan, M. J., Din, S. U., Khurshid, A., and Noor, U. (2019). Political participation through social media: Comparison of pakistani and malaysian youth. IEEE Access. 7, 35532–35543. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2904553

Kim, Y., Chen, H. T., and Wang, Y. (2016). Living in the smartphone age: examining the conditional indirect effects of mobile phone use on political participation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 60, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2016.1203318

Kim, Y., and Khang, H. (2014). Revisiting civic voluntarism predictors of college students' political participation in the context of social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 36, 114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.044

Lee, S., and Xenos, M. (2020). Incidental news exposure via social media and political participation: evidence of reciprocal effects. New Media Soc. 24, 178–201. doi: 10.1177/1461444820962121

Liao, S. (2019). “# IAmGay# what about you?”: storytelling, discursive politics, and the affective dimension of social media activism against censorship in China. Int. J. Commun. 13, 2314–2333. Available online at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10376/2658

Lin, T. T., and Chiang, Y. H. (2017). Dual screening: examining social predictors and impact on online and offline political participation among Taiwanese Internet users. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 61, 240–263. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2017.1309419

Madison, N., and Klang, M. (2020). The case for digital activism: refuting the fallacies of slacktivism. J. Digit. Soc. Res. 2, 28–47. doi: 10.33621/jdsr.v2i2.25

Mercurio, R. (2019,. December 17). Gender Equality: Philippines Out of Top 10. Philstar.com. Available online at: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/12/18/1977944/gender-equality-philippines-out-top-10

Miller, L. A. (2018). Social media savvy: risk versus benefit. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 32, 206–208. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000346

Murthy, D. (2018). Introduction to social media, activism, and organizations. Social Media+ Society 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1177/2056305117750716

National Youth Commission (2021). NYC Vision, Mission, and Core Values. National Youth Commission. Available online at: https://nyc.gov.ph/vision-mission/.

Omotayo, F., and Folorunso, M. B. (2020). Use of social media for political participation by youths. JeDEM 12, 133–158. doi: 10.29379/jedem.v12i1.585

Parmanand, S. (2020). Duterte as the macho messiah: chauvinist populism and the feminisation of human rights in the Philippines. Rev. Womens Stud. 29, 1–30. Available online at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/11fzdrqzQ3kx4Rzjg1u4ppdumVSDoUspC

Pek, J., Wong, O., and Wong, A. (2018). How to address non-normality: a taxonomy of approaches, reviewed, and illustrated. Front. Psychol. 9:2104. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02104

Piat, C. (2019). Slacktivism: not simply a means to an end, but a legitimate form of civic participation. Can. J. Fam. Youth 11, 162–179. doi: 10.29173/cjfy29411

Quan-Haase, A., Mendes, K., Ho, D., Lake, O., Nau, C., and Pieber, D. (2021). Mapping# MeToo: a synthesis review of digital feminist research across social media platforms. New Media Soc. 23, 1700–1720. doi: 10.1177/1461444820984457

Quaranta, M., and Dotti Sani, G. M. (2018). Left behind? Gender gaps in political engagement over the life course in twenty-seven European countries. Soc. Polit. Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 25, 254–286. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxy005

Schradie, J. (2011). The digital production gap: the digital divide and Web 2.0 collide. Poetics 39, 145–168. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2011.02.003

Seibicke, H. (2017). “Campaigning for gender equality through social media: the european women's lobby,” in Social Media and European Politics, eds M. Barisione and A. Michailidou (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 123–142.

Shehzad, M., Ali, A., and Shah, S. M. B. (2021). Relationship among social media uses, internet mediation and political participation in Pakistan. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 9, 43–53. doi: 10.18510/hssr.2021.925

Shevtsova, M. (2017). Learning the Lessons from the Euromaidan: the ups and downs of LGBT activism in the Ukrainian public sphere. Kyiv-Mohyla Law Polit. J. 3, 157–180. doi: 10.18523/kmlpj120123.2017-3.157-180

Statista Research Department (2021a). Topic: Social Media Use During Coronavirus (COVID-19) Worldwide. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-covid-19-worldwide/.

Statista Research Department (2021b). Share of Advertising Audience of Social Media in the Philippines as of January 2021, by Age and Gender. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1139168/philippines-social-media-advertising-audience-age-and-gender/

Stornaiuolo, A., and Thomas, E. E. (2017). Disrupting educational inequalities through youth digital activism. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 337–357. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16687973

Strachan, O. (2021). Christianity and Wokeness: How the Social Justice Movement Is Hijacking the Gospel-and the Way to Stop It. Simon and Schuster.

Strömbäck, J., Falasca, K., and Kruikemeier, S. (2018). The mix of media use matters: investigating the effects of individual news repertoires on offline and online political participation. Polit. Commun. 35, 413–432. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1385549

Swank, E., and Fahs, B. (2013). An intersectional analysis of gender and race for sexual minorities who engage in gay and lesbian rights activism. Sex Roles 68, 660–674. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0168-9

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of inter- group conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Inter-Group Relations, eds W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Thompson, J., and Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. (2021). Sexuality and the City: The Geography of LGBT Political Participation in the United States. (Preprint). doi: 10.31219/osf.io/zv3hp

Tugtekin, E. B., and Koc, M. (2020). Understanding the relationship between new media literacy, communication skills, and democratic tendency: model development and testing. N. Media Soc. 22, 1922–1941. doi: 10.1177/1461444819887705

U. N. Women (2021). ASEAN Gender Outlook. Achieving the SDGs for All and Leaving No Woman or Girl Behind. Available online at: https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/ASEAN/ASEAN%20Gender%20Outlook_final.pdf

Van Deth, J. W. (2014). A conceptual map of political participation. Acta Polit. 49, 349–367. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.6

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., and Chiriac, E. H. (2017). The biographical consequences of protest and activism: a systematic review and a new typology. Soc. Mov. Stud. 16, 203–221. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2016.1252665

Vochocová, L., Štětka, V., and Mazák, J. (2016). Good girls don't comment on politics? Gendered character of online political participation in the Czech Republic. Inf. Commun. Soc. 19, 1321–1339. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1088881

Waeterloos, C., Walrave, M., and Ponnet, K. (2021). Designing and validating the social media political participation scale: an instrument to measure political participation on social media. Technol. Soc. 64:101493. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101493

Wang, H., Cai, T., Mou, Y., and Shi, F. (2018). Traditional resources, internet resources, and youth online political participation: the resource theory revisited in the Chinese context. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 50, 115–136. doi: 10.1080/21620555.2017.1341813

Warner, M., Kitkowska, A., Gibbs, J., Maestre, J. F., and Blandford, A. (2020). “Evaluating prefer not to say around sensitive disclosures,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Honolulu, HI), 1–13. doi: 10.1145/3313831.3376150

Yamamoto, M., and Nah, S. (2018). Mobile information seeking and political participation: a differential gains approach with offline and online discussion attributes. N. Media Soc. 20, 2070–2090. doi: 10.1177/1461444817712722

Yamamoto, M., Nah, S., and Bae, S. Y. (2020). Social media prosumption and online political participation: an examination of online communication processes. N. Media Soc. 22, 1885–1902. doi: 10.1177/1461444819886295

Yang, H. C., and DeHart, J. L. (2016). Social media use and online political participation among college students during the US election 2012. Social Media+ Soc. 2:2056305115623802. doi: 10.1177/2056305115623802

Yu, R. P., and Oh, Y. W. (2018). Social media and expressive citizenship: understanding the relationships between social and entertainment expression on Facebook and political participation. Telematics Inform. 35, 2299–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.09.010

Zappavigna, M. (2015). Searchable talk: The linguistic functions of hashtags. Soc. Semiotics 25, 274–291. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2014.996948

Zhu, A. Y. F., Chan, A. L. S., and Chou, K. L. (2019). Creative social media use and political participation in young people: the moderation and mediation role of online political expression. J. Adolesc. 77, 108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.10.010

Zhu, S., Hao Yang, H., Xu, S., and MacLeod, J. (2020). Understanding social media competence in higher education: development and validation of an instrument. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 57, 1935–1955. doi: 10.1177/0735633118820631

Keywords: gender, political participation, social media, social media competence, youth activism

Citation: Dayrit JCS, Albao BT and Cleofas JV (2022) Savvy and woke: Gender, digital profile, social media competence, and political participation in gender issues among young Filipino netizens. Front. Sociol. 7:966878. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2022.966878

Received: 11 June 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 28 July 2022.

Edited by:

Marta Evelia Aparicio-Garci̧a, Complutense University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Meiko Makita, University of Wolverhampton, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Dayrit, Albao and Cleofas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jerome Visperas Cleofas, amVyb21lLmNsZW9mYXNAZGxzdS5lZHUucGg=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.