- 1Yale School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 2Yale College, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3Yale Institute for Global Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Restrictions to research due to COVID-19 have required global health researchers to factor public health measures into their work and discuss the most ethical means to pursue research under safety concerns and resource constraints. In parallel, global health research opportunities for students have also adapted to safety concerns and resource constraints. Some projects have been canceled or made remote, but inventively, domestic research opportunities have been created as alternatives for students to continue gaining global health learning competencies. Knowing the ethical challenges inherent in short-term student global health research and research in strained health systems, it is intriguing why these safer alternatives were not previously pervasive in global health education. This paper provides perspectives from students training at academic institutions in the US on how COVID-19 disrupted student research and what can be learned from the associated shifts in global health research. Additionally, the authors take this opportunity to advocate for academic institutions from high-income countries to reflect on long-standing global health research conventions that have been perpetuated and bolster training for students conducting global health research. The authors draw on their experiences, existing literature, and qualitative interviews with students who pursued global health research during COVID-19.

Introduction

COVID-19 has threatened public health practice and research. Under pressure from this global public health emergency, several global disparities and structural injustices have been illuminated, notably access to adequate healthcare and essential treatments during this time (Wouters et al., 2021). Disruptions caused by COVID-19 have provided institutions and researchers alike an opportunity to reconsider the ethics of their public health services and research. Specifically, travel and gathering guidelines aimed at preventing viral transmission and reducing strain on health systems with dwindling resources have pushed research institutions and research ethics boards to implement policies that restrict activities, putting research on hold (Lumeng et al., 2020; Nature Medicine, 2020; Leal Filho et al., 2021). As a result, global health researchers have been required to factor public health measures into their work and discuss the most ethical means to pursue research under safety and resource constraints (Yeoh and Shah, 2020). While these concerns and constraints were already prevalent before the pandemic, it is curious why this level of scrutiny had not been applied before the pandemic, especially when many projects are conducted in low-resource environments and involve unequal partnerships that limit communities’ ownership and input (Bukusi et al., 2018; Pratt, 2020, 202).

Student-led global health research has adapted as well. Many student projects have been canceled, and research programs have created local research opportunities as alternatives for students to experientially gain global health learning competencies, such as the ability to adapt to low-resource settings, be socio-culturally aware, and apply social justice principles to practice (Jacobsen et al., 2019). Considering the well-known ethical challenges inherent in short-term experiences in global health and global health research, one may question why these safer alternatives, motivated by COVID-19, were not already the status quo (Tryon et al., 2008; Standish et al., 2014). The emergence of these alternatives is evidence that typical global health competencies do not preclude local opportunities as ways to achieve them.

This paper provides our perspectives, as undergraduate and graduate students from an academic institution in the US, on the impact of COVID-19 on student global health research and lessons learned. We argue that the alternatives to student-led global health research and heightened awareness of ethical conduct in global health research during COVID-19 should be maintained post-pandemic. Moreover, we suggest that academic institutions improve global health research training and commit to guidelines for ethical global health education. We primarily draw on our own experiences and literature on global health research student ethics, which is lacking; thus, we included studies related to professional student global health experiences. We also use excerpts from qualitative interviews conducted with students involved in human-subjects global health research projects during COVID-19 from a separate but related study led by one of the authors. Lastly, we end with a list of recommendations for academic institutions.

Interviews for this reflection received institutional review board (IRB) exemption by the Yale University IRB. Eligible students were enrolled in a US institution, over 18 years of age, and conducted global health human subjects research on domestic or international populations. Participants were required to have IRB approval and operate via a remote platform during the COVID-19 pandemic (post-March 2020) to be considered for inclusion. Thirty-nine students showed interest in participating in a 30 min qualitative interview, and eleven eligible participants were interviewed throughout 2021. Most informants were graduate students (e.g., MPH, MA, MS), but some undergraduate and professional students (e.g., medical, physician associate) participated. Gender was equally distributed. Most participants identified as White, and several identified as African American/Black, Asian, Hispanic/Latino, or Other. Student projects were conducted remotely in Asia, the Pacific Islands, Eastern Africa, the Middle East, South Korea, Russia, and the US. Examples of research topics included refugees’ health during COVID-19, physician perspectives on interventions like Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), and mental health.

Student Global Health Research During COVID-19

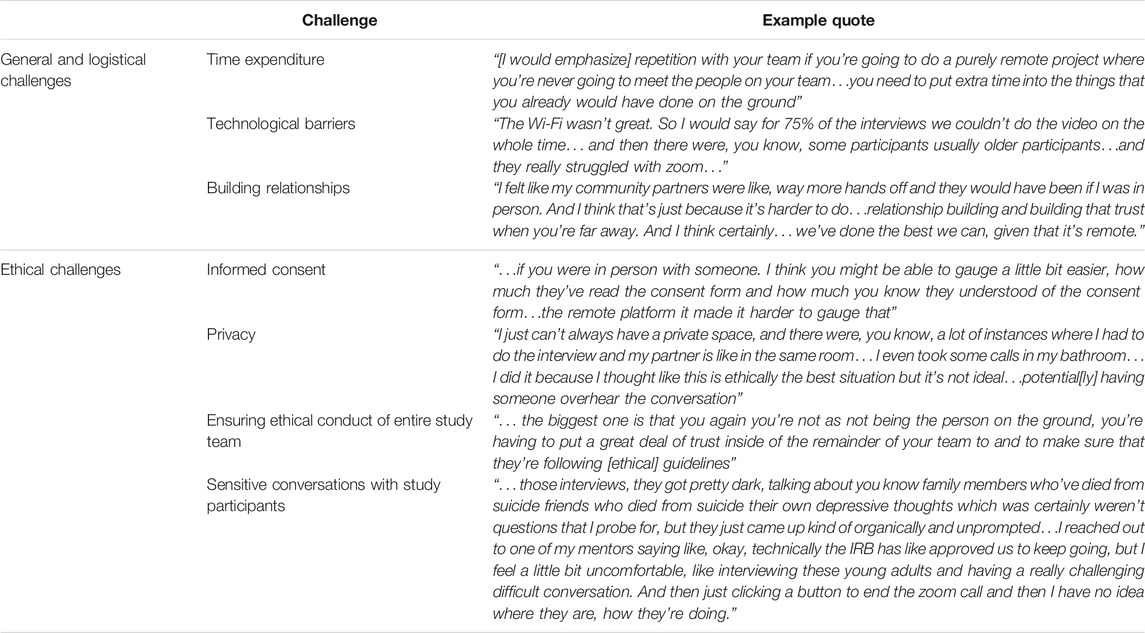

In parallel with research in most fields, the nature of global health research opportunities available to students has also changed dramatically due to COVID-19. Many existing opportunities were canceled or adapted into remote global health research. Our interviews revealed that remote projects during this time were challenging pursuits (Table 1). When asked about the general challenges of remote research, students described how typical research tasks took more time, involved technological barriers, and introduced issues with relationship building. When asked about the ethical challenges of remote research, students described issues regarding informed consent, privacy, ensuring ethical conduct of study team members, and dealing with sensitive conversations with study participants.

Global health research is typically health research on populations from another country (usually low-and-middle-income countries), but our interviews with students showed that COVID-19 has perhaps broadened it to Koplan et al.’s definition of encompassing research that “improves health and achieves health equity for all people worldwide” (Koplan et al., 2009). Interestingly, we found that domestic research on a local population was acknowledged as a student global health research opportunity. One of the authors was awarded a student fellowship to conduct domestic research on refugee and asylum-seeking populations in their local community during COVID-19. Domestic research on local populations had never been permitted in the history of the fellowship, which kept a conservative definition of global health research that required students to travel internationally and conduct work on global populations. The author recounts their experience in the following reflection:

“The COVID-19 pandemic was the catalyst for my grant-awardees’ opening criteria to domestic global health populations. I saw a need in my community, but due to geographic location, a previous application would have been rejected. I am actually very happy to be working domestically. I not only gain knowledge of global health and the skill-set that comes from navigating barriers unique to global health, but I have the opportunity to continue working with this global health population well after my research is done and/or to adjust my research as needed. I do not have as stringent time constraints as I would if I traveled abroad.”

This example demonstrates how existing conventions have been transformed for the benefit of students but also for communities that benefit from such research. Importantly, it highlights the value of local research, echoing the pervasive view that global health includes local health and that global health education should include local and global contexts (Rowthorn, 2016; Wees and Holmer, 2020).

Local opportunities occur in a familiar healthcare system and reduce cultural and language differentials (DeCamp et al., 2018). They also allow students to remain engaged for extended periods, ensuring proper knowledge translation and communication of findings back to the community. This would combat common critiques that global health research experiences for students produce unsustainable outputs and inadequate benefits, among many others (Provenzano et al., 2010; Bauer, 2017).

Global health research can offer irreplaceable experiences that will equip students with comprehensive competencies and contextualize the concepts (e.g., social determinants of health, capacity building) they learn about in the classroom (Jogerst et al., 2015; Kalbarczyk et al., 2020). Students develop adaptability, problem-solving skills, and cultural competency, humility, and sensitivity, preparing them to work effectively in diverse communities. Certainly, these competencies can be gained in domestic research (Jogerst et al., 2015; Jacobsen et al., 2019; Rabin et al., 2021). Moreover, eliminating domestic research opportunities for global health students would be a disservice to local communities that could benefit significantly from research conducted by students who are motivated by a sense of goodwill and an interest in generating evidence that will reduce the health inequities. COVID-19 has shown us that when international host communities face health crises that make research ethically challenging, we should legitimize domestic research opportunities as ways for students in global health to fulfill program requirements and competencies.

Ethics in Global Health Research Training

Whether research is on international or domestic populations, academic institutions must ensure that global health research ethics (GHRE) is properly taught to students pursuing global health research. GHRE encompasses the governance of research practices, ethical principles, and moral integrity in global health research. It is a necessary safeguard for global health research because harm still occurs even when well-intentioned researchers follow the proper ethical review processes and have well-established research partnerships (Yassi et al., 2013; De Visser et al., 2020; Nyirenda et al., 2020).

Typically, student-led global health research projects have focused on students’ needs and learning priorities. However, with GHRE principles integrated into research training, we could bring much-needed attention to host communities’ needs and priorities in research post-COVID-19. These principles include the basic bioethical principles (autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice) and those frequently identified in the global health literature (e.g., Lasker et al.’s six core principles such as “host partner defines the program and needs of host community”) (Lasker et al., 2018). Understanding GHRE is necessary for students who pursue short-term experiences and have little exposure to different cultures and experience working in low-resource settings (Pinto and Upshur, 2009). Preparing students for ethically challenging situations will equip students with the tools and resources necessary to navigate ethical dilemmas without doing further harm.

Even though discussions about GHRE are making their way into academic institutions, applying GHRE in practice has been less effective in preparing students for ethical dilemmas (Standish et al., 2014; Rowthorn et al., 2019; Chiumento et al., 2020; Wright, 2020). Currently, most training workshops for students pursuing global health research projects are brief, covering only logistics and safety, and seldom incorporate training on dealing with ethical issues despite students being eager to learn how to be an ethical researcher:

“I was grateful for the fact that like we had training because… at my previous institution… we didn’t have like pre like placement training, and I remember…I was like very vocal for advocating that we needed something like that because I think there is, you know, potential danger for people, you know, to just be put in those kind of situations.”

“I think that would have been helpful I feel like me having training in the local culture would have been beneficial no matter what… there’s a lot of… implicit social norms that kind of need to be unpacked…because then the folks that I’m speaking to will actually like unpack these concepts that might not [need to] be unpacked [if it were with someone from the community]”

Critics have questioned students’ motivations, calling out their ignorance; however, with proper guidance and training, students stand to gain an ability to critically appraise their research with an ethical lens. When incorporated, GHRE training can prompt students to reflect on their role as a researcher:

“…it really challenged us to be reflective about, what it means to be an ally, what does it mean to partner with communities in a truly ethical and non-tokenizing manner, [in turn] causing us to confront who benefits from the research. If the community isn’t benefiting, then it’s probably not worth doing.”

“[I asked myself], am I benefiting because I get papers, because I get promotions and because I get to travel to a cool place? Or, is the community truly benefiting? [The course allowed more] thinking about [questions such as] if the community isn’t benefiting, then it’s probably not worth doing.”

“I think like having that training, even though it was really intensive just completely transformed how I see myself and prompted me to be a lot more reflective about my positionality and how, even if I don’t mean to, some of my actions could be causing more harm than good.”

Training should teach students to be aware of cultural differences, local laws and standards regarding planned activities, the history of the country, local health needs, and general global health inequities that may exist in research settings (Lasker et al., 2018; Kalbarczyk et al., 2020). It should also foster research integrity from study ideation to dissemination of findings (Bukusi et al., 2018). Lastly, students should receive both conceptual and practical (e.g., case-based) training that motivates ethical reflection and gives students tools to deal with issues (Mulhearn et al., 2017; DeCamp et al., 2018). This is vital because, despite receiving some form of training and having the ability to identify ethical issues, students still report being hesitant to seek help, feeling ill-equipped to address ethical issues, and having trouble communicating with study participants and local project teams (Standish et al., 2021).

Institutional Reforms

From our perspective, as students studying global health at an academic institution in the US, we believe that direct improvements to training students alone will not promote sustainable shifts towards ethical student-led global health research. Structural changes to the academic context, especially in high-income countries like the US, through policy and practice are necessary. There are numerous competent global health education guidelines that academic institutions from high-income countries can draw from. The Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) ’s best-practice guidelines for training experiences in global health can be used to clarify and improve relationships between stakeholders (Crump and Sugarman, 2010). These include specific guidelines for sending institutions, host institutions, trainees, and mentors and emphasize strengthening student and mentor relationships with resources that can facilitate the monitoring and resolution of potential ethical concerns in research settings. Objectives for training students can be informed by Pinto and Upshur (2009)’s four ethical principles of humility, introspection, solidarity, and social justice for students and trainees to apply to global health work. Lastly, the Brocher Declaration, which many academic institutions and research centers have signed, contains guiding principles for global health work that can aptly apply to global health education and research, especially concerning building partnerships and the welfare of local communities involved (Brocher Foundation, 2020). This declaration can be broadly applied to ensure ethical global partnerships, the foundation of many short-term student global health research projects.

Finally, in discussing institutional reform, we would be remiss if we ignored academic institutions’ role in influencing students’ intentions to pursue global health research. Many academic institutions, particularly admissions committees, commonly deem international experiences as “enriching” experiences that support a global health or health-related career (Shah et al., 2019). As students are still learning, growing, and finding footing in global health, these expectations alter their intentions and value judgments when encountering ethical issues in their projects, despite most having a sense of goodwill. Consequently, instead of their goal being to support and uplift a community, it shifts towards impressing an admission committee. When institutions promote international global health research opportunities among their students, it also furthers this frame of mind. We want to bring this rarely discussed issue to light through our unique perspective. To rectify this issue, institutions should discourage such biases in academic programs and communicate these values appropriately to applicants.

COVID-19 as an Opportunity for Improvement

Despite global health research ethics existing as a prominent field of study at many leading academic institutions, it is understandable why global health research ethics may be inadequately applied to practice. The movement towards discovering ethical harms in global health may outpace institutions’ capacity to reform antiquated structures and processes. Decentralized leadership among academic institutions and research centers also makes instigating a concerted effort to dismantle existing barriers to ethical research practices cross-sectionally challenging.

COVID-19 and its associated disruptions have provided an opportunity for inventive forms of virtual research and study. Travel restrictions and heightened COVID-19 risks worldwide have significantly reduced in-person student research experiences in global settings. However, many student research methods have emerged in response to the pandemic, such as virtual interviews, telehealth, and social media research (Hou et al., 2020). These innovative research methods can make research capacity more accessible in global settings during COVID-19 and in the future.

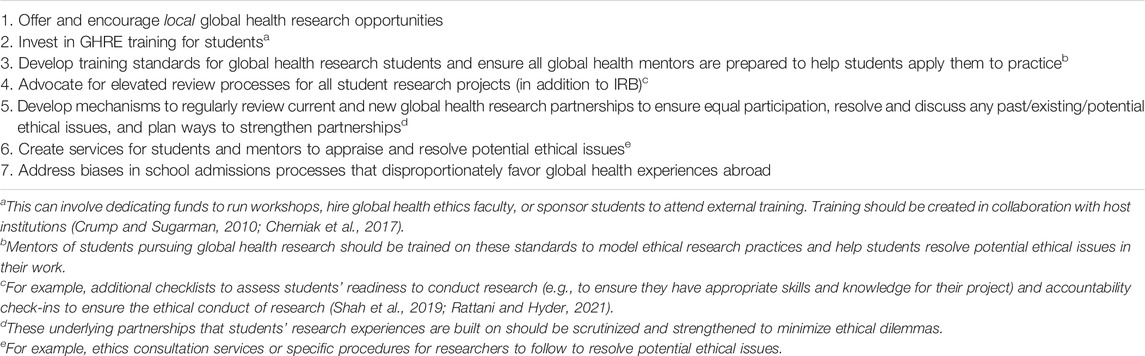

Additionally, the associated attention to ethically permissible research presents an opportunity to reflect and plan for reforms. As such, we offer a set of recommendations that are informed by the student interviews, literature, and guidelines presented in this reflection (Table 2).

Discussion

While the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated global health research, it has also provided space to reflect on issues once taken at face value.

The disruption of COVID-19 on student research is unavoidable and expected since these are short-term and often low-priority endeavors. However, for students with time-limited degrees and breaks from classes, these would have been significant opportunities for growth and essential for a career in global health. By creating domestic opportunities, academic institutions are rightly asking how to continue fostering global health educational competencies to accommodate new barriers (i.e., travel restrictions, safety concerns, and resource constraints). However, since some of these barriers existed before COVID-19, why hadn’t academic institutions encouraged students to conduct domestic research opportunities before? This is the question we started with, which led us to reflect on the systems and conventions of global health that institutions are perpetuating with such practices. It also made us contemplate the type of global health researchers that academic institutions are fostering with such practices.

The necessary reforms to global health research and education outlined in this paper are not issues students can rectify on their own. We believe there are ample opportunities for academic institutions to take charge. The main reforms mentioned, such as creating more domestic research opportunities for students and integrating more GHRE into training, would signal an institution’s commitment to global health that includes local communities. These actionable recommendations acknowledge that all health inequities deserve attention, no matter which part of the world they are from. Such improvements would not only have a ripple effect in fostering the development of ethical global health practitioners but would inevitably contribute to decolonizing global health research and education.

We end this reflection with a fitting quote by Arundhati Roy, which we direct at academic institutions that are pausing, reflecting, and improving during this time:

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one (COVID-19) is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice…and dead ideas…Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it” (Roy, 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Yale University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to drafting and proofreading the manuscript. CC and GG contributed equally to the conceptualization and planning of this manuscript, applying knowledge of literature and reflections from previous related work. JLW contributed fully to recruiting and interviewing study participants.

Conflict of Interest

Author JLW was employed by Yale Institute for Global Health. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Yale Institute for Global Health and the Global Health Ethics Program (GHEP) provided support for this manuscript. We would like to thank the GHEP directors and our mentors, Dr. Kaveh Khoshnood and Dr. Tracy Rabin, for inspiring this paper, helping us revise it, and encouraging us to reflect deeply on our role as students studying global health during COVID-19. We would also like to thank Virginia Rowthorn, JD, for providing feedback on this manuscript. Lastly, we would also like to thank all the students who participated in our interviews and provided insightful and honest recounts of their global health research experiences during the pandemic.

References

Bauer, I. (2017). More Harm Than Good? the Questionable Ethics of Medical Volunteering and International Student Placements. Trop. Dis. Trav. Med Vaccin. 3, 5. doi:10.1186/s40794-017-0048-y

Brocher Foundation (2020). Brocher Declaration. Available at: https://www.ghpartnerships.org/brocher (Accessed August 26, 2021).

Bukusi, E. A., Manabe, Y. C., and Zunt, J. R. (2018). Mentorship and Ethics in Global Health: Fostering Scientific Integrity and Responsible Conduct of Research. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100, 42–47. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0562

Cherniak, W., Latham, E., Astle, B., Anguyo, G., Beaunoir, T., Buenaventura, J. H., et al. (2017). Host Perspectives on Short-Term Experiences in Global Health: a Survey. Lancet Glob. Health 5, S9. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30116-X

Chiumento, A., Rahman, A., and Frith, L. (2020). Writing to Template: Researchers' Negotiation of Procedural Research Ethics. Soc. Sci. Med. 255, 112980. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112980

Crump, J. A., and Sugarman, J. (2010). Ethics and Best Practice Guidelines for Training Experiences in Global Health. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83, 1178–1182. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527

De Visser, A., Hatfield, J., Ellaway, R., Buchner, D., Seni, J., Arubaku, W., et al. (2020). Global Health Electives: Ethical Engagement in Building Global Health Capacity. Med. Teach. 42, 628–635. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1724920

DeCamp, M., Lehmann, L. S., Jaeel, P., and Horwitch, C. (2018). Ethical Obligations Regarding Short-Term Global Health Clinical Experiences: An American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann. Intern. Med. 168, 651–657. doi:10.7326/M17-3361

Hou, L., Mehta, S. D., Christian, E., Joyce, B., Lesi, O., Anorlu, R., et al. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Global Health Research Training and Education. J. Glob. Health 10 (2), 020366. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020366

Jacobsen, K. H., Zeraye, H. A., Bisesi, M. S., Gartin, M., Malouin, R. A., and Waggett, C. E. (2019). Master of Public Health Global Health Concentration Competencies: Preparing Culturally Skilled Practitioners to Serve Internationally, Nationally, and Locally. Am. J. Public Health 109, 1189–1190. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305208

Jogerst, K., Callender, B., Adams, V., Evert, J., Fields, E., Hall, T., et al. (2015). Identifying Interprofessional Global Health Competencies for 21st-Century Health Professionals. Ann. Glob. Health 81, 239–247. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.03.006

Kalbarczyk, A., Harrison, M., Sanguineti, M. C. D., Wachira, J., Guzman, C. A. F., and Hansoti, B. (2020). Practical and Ethical Solutions for Remote Applied Learning Experiences in Global Health. Ann. Glob. Health 86, 103. doi:10.5334/aogh.2999

Koplan, J. P., Bond, T. C., Merson, M. H., Reddy, K. S., Rodriguez, M. H., Sewankambo, N. K., et al. (2009). Towards a Common Definition of Global Health. Lancet 373, 1993–1995. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

Lasker, J. N., Aldrink, M., Balasubramaniam, R., Caldron, P., Compton, B., Evert, J., et al. (2018). Guidelines for Responsible Short-Term Global Health Activities: Developing Common Principles. Glob. Health 14, 18. doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0330-4

Leal Filho, W., Azul, A. M., Wall, T., Vasconcelos, C. R. P., Salvia, A. L., do Paço, A., et al. (2021). COVID-19: the Impact of a Global Crisis on Sustainable Development Research. Sustain. Sci. 16, 85–99. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00866-y

Lumeng, J. C., Chavous, T. M., Lok, A. S., Sen, S., Wigginton, N. S., and Cunningham, R. M. (2020). Opinion: A Risk-Benefit Framework for Human Research during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 27749–27753. doi:10.1073/pnas.2020507117

Mulhearn, T. J., Steele, L. M., Watts, L. L., Medeiros, K. E., Mumford, M. D., and Connelly, S. (2017). Review of Instructional Approaches in Ethics Education. Sci. Eng. Ethics 23, 883–912. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9803-0

Nature Medicine (2020). Safeguard Research in the Time of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 443. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0852-1

Nyirenda, D., Sariola, S., Kingori, P., Squire, B., Bandawe, C., Parker, M., et al. (2020). Structural Coercion in the Context of Community Engagement in Global Health Research Conducted in a Low Resource Setting in Africa. BMC Med. Ethics 21, 90. doi:10.1186/s12910-020-00530-1

Pinto, A. D., and Upshur, R. E. (2009). Global Health Ethics for Students. Dev. World Bioeth. 9, 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x

Pratt, B. (2020). What Constitutes Fair Shared Decision-Making in Global Health Research Collaborations? Bioethics 34, 984–993. doi:10.1111/bioe.12793

Provenzano, A. M., Graber, L. K., Elansary, M., Khoshnood, K., Rastegar, A., and Barry, M. (2010). Short-Term Global Health Research Projects by US Medical Students: Ethical Challenges for Partnerships. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83, 211–214. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0692

Rabin, T. L., Mayanja-Kizza, H., and Barry, M. (2021). Global Health Education in the Time of COVID-19: An Opportunity to Restructure Relationships and Address Supremacy. Acad. Med. 96, 795–797. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003911

Rattani, A., and Hyder, A. A. (2021). Operationalizing the Ethical Review of Global Health Policy and Systems Research: A Proposed Checklist. J. L. Med. Ethics 49, 92–122. doi:10.1017/jme.2021.15

Rowthorn, V., Loh, L., Evert, J., Chung, E., and Lasker, J. (2019). Not Above the Law: A Legal and Ethical Analysis of Short-Term Experiences in Global Health. Ann. Glob. Health 85, 79. doi:10.5334/aogh.2451

Rowthorn, V. (2016). Global/Local: What Does it Mean for Global Health Educators and How Do We Do it? Ann. Glob. Health 81, 593–601. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.12.001

Roy, A. (2020). Arundhati Roy: 'The Pandemic Is a portal' | Free to Read. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca (Accessed June 17, 2021).

Shah, S., Lin, H. C., and Loh, L. C. (2019). A Comprehensive Framework to Optimize Short-Term Experiences in Global Health (STEGH). Glob. Health 15, 27. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0469-7

Standish, K. R., McDaniel, K. G., Mira, M., and Khoshnood, K. (2014). Are We Practicing what We Teach? Ethical Guidelines and Student Global Health Research Experiences. Ann. Glob. Health 80, 178–179. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2014.08.059

Standish, K., McDaniel, K., Ahmed, S., Allen, N. H., Sircar, S., Mira, M., et al. (2021). U.S. Trainees' Experiences of Ethical Challenges during Research in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Mixed Methods Study. Glob. Public Health, 1–17. doi:10.1080/17441692.2021.1933124

Tryon, E., Stoecker, R., Martin, A., Seblonka, K., Hilgendorf, A., and Nellis, M. (2008). The Challenge of Short-Term Service-Learning. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 14, 16–26. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0014.202

Herzig van Wees, S., and Holmer, H. (2020). Global Health beyond Geographical Boundaries: Reflections from Global Health Education. BMJ Glob. Health 5, e002583. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002583

Wouters, O. J., Shadlen, K. C., Salcher-Konrad, M., Pollard, A. J., Larson, H. J., Teerawattananon, Y., et al. (2021). Challenges in Ensuring Global Access to COVID-19 Vaccines: Production, Affordability, Allocation, and Deployment. Lancet 397, 1023–1034. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8

Wright, K. S. (2020). Ethical Research in Global Health Emergencies: Making the Case for a Broader Understanding of 'research Ethics'. Int. Health 12, 515–517. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihaa053

Yassi, A., Breilh, J., Dharamsi, S., Lockhart, K., and Spiegel, J. M. (2013). The Ethics of Ethics Reviews in Global Health Research: Case Studies Applying a New Paradigm. J. Acad. Ethics 11, 83–101. doi:10.1007/s10805-013-9182-y

Keywords: COVID-19, student research, global health, training, student reflection, ethics education and training

Citation: Chu C, Griffin G and Williams JL (2022) Taking Pause: A COVID-19 Student Reflection on Global Health Research Opportunities, Training, and Institutional Reform. Front. Sociol. 7:768821. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2022.768821

Received: 01 September 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022;

Published: 20 January 2022.

Edited by:

Hannah Bradby, Uppsala University, SwedenReviewed by:

Martha Judith Chinouya, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, United KingdomFaith Ikioda, University of Bedfordshire, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Chu, Griffin and Williams. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Casey Chu, Y2FzZXljaHVAYXlhLnlhbGUuZWR1

Casey Chu

Casey Chu Gianna Griffin

Gianna Griffin Joseph L. Williams

Joseph L. Williams