- 1Department of Management and Business, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, United States

- 2School of Information Studies, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, United States

We report findings from an ongoing panel study of 68 U.S.-based online freelancers, focusing here on their experiences both pre- and in-pandemic. We see online freelancing as providing a window into one future of work: collaborative knowledge work that is paid by the project and mediated by a digital labor platform. The study’s purposive sampling provides for both empirical and conceptual insights into the occupational differences and career plans of freelance workers. The timing of the 2020 data collection provides insight into household changes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings make clear these workers are facing diminished work flexibility and increased earning uncertainty. And, data show women are more likely than men to reduce working hours to help absorb the increased share of caregiving and other domestic responsibilities. This raises questions of online freelancing as a viable career path or sustainable source of work.

Introduction

We provide empirical evidence and theorizing regarding how U.S.-based freelancers working on online platforms are responding to the coronavirus-induced crisis. To do this, we combine survey data with interviews of freelance workers who use one online work platform. We pursue this work recognizing that the implications to workers and labor markets, due the global COVID-19 pandemic, are profound (Atkeson, 2020; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020; Stephany et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020). We also see this work as providing a window into one possible future of work, online freelancing, that is both fundamentally precarious and an increasingly common form of contemporary labor (e.g., Erickson et al., 2019; Harmon and Silberman, 2019; Jarrahi et al., 2020).

Online freelancing reflects a form of labor market that relies on mediated and fully digital interactions between these workers and potential employers. Even as O’Farrell and Montagnier, (2019) articulate difficulties with determining the scale of platform-mediated work, estimates suggest there are 56 million online freelancers globally, 40% of whom are U.S. - based (Kässi and Lehdonvirta, 2018; Stephany et al., 2021). And, these online labor markets have grown by almost 50% since 2017 (Kässi and Lehdonvirta, 2018; Stephany et al., 2021). This growth reflects the lure of worker flexibility (finding work when one wants) aligning with desires of organizations for flexible workforces (finding workers as needed) (e.g., Kalleberg, 2003).

The global and virtual nature of online freelancing allows greater competition because of the low barriers to entry (Dunn, 2017). And, in countries like the U.S., online freelancers are independent contractors. This means they lack benefits like health care, retirement, leave, and other workplace protections afforded to full-time workers (International Labour Organization, 2016; McKay Pollack and Fitzpayne, 2019). This lack of labor protections means online labor markets and online freelancers are likely to feel the effects of economic changes such as the current pandemic more acutely than would those who have more labor market or workplace protections.

Further compounding the precariousness of online freelance work are the gendered realities and challenges for work-life balance, which are felt more acutely by women (Hannák et al., 2017; Ciolfi and Lockley, 2018). Women, for example, are responsible for 75% of unpaid care and domestic work around the globe (Moreira da Silva, 2019). As such, women are often engaging in additional work outside the traditional labor economy, what sociologists call a “second shift,” referring to unpaid household responsibilities (Hochschild and Machung, 1989), and a “third shift,” referring to unpaid emotional labor outside the home (Gerstel, 2000). Within the context of online freelancing, scholars have shown the naivete of the notion that these platform-mediated markets are gender-neutral (e.g., Foong, Vincent, Hecht and Gerber, 2018; Pichault and McKeown, 2019).

All of this drives us to pursue the following research questions: 1) What are the experiences and expectations of online freelance workers in the face of rapid market changes and the uncertainty of an ongoing global pandemic and 2) In what ways do the responses to the pandemic’s impact differ by gender?

Why Workers Pursue Online Freelance Work

Online Freelancing: Flexibility and Access to Work Online

Online freelancers are knowledge workers that find their work via online labor platforms. Because it is primarily cognitive work, this type of work can be done independent of location (Erickson and Jarrahi, 2016; Sutherland and Jarrahi, 2017). This market-mediated collaboration distinguishes online freelancing and online labor platforms like Upwork and Freelancer.com from gig-working sites like Uber or Deliveroo, as the latter involve physical on-site service delivery (Kalleberg and Dunn, 2016; Vallas and Schor, 2020). Likewise, online freelancing is distinct from micro-tasking sites like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT) by the complexity of the tasks and the expectation of worker/employer interactions for guidance and sense-making (Wood et al., 2019a; Gray and Suri, 2019; Howcroft and Bergvall-Kåreborn, 2019).

One of the most-often-noted reasons by people pursuing work online is the flexibility it affords (Malone, 2004; Horton, 2010; Johns and Gratton, 2013; Kuek et al., 2015; Sundararajan, 2016; Wheatly, 2017). Early accounts highlighted that online work allowed the flexibility to care for home, school or business responsibilities while earning a salary (Kuek et al., 2015). Recent accounts are more critical of working online, noting flexibility also often means that access to work is uncertain and other options may no longer be available given changes in the labor markets (e.g. Aroles et al., 2019; Wood et al., 2019b; Pichault and McKeown, 2019).

To better understand flexibility in online freelance work, we draw insight from other technology-enabled flexible working arrangements such as telework, telecommuting, nomadic, flextime, and flexplace: all important topics of scholarship since the 1990s (see Baltes et al., 1999; Sutherland and Jarrahi, 2017; Erickson et al., 2019). Building from these areas, scholars have identified potential advantages to flexible scheduling such as reducing work-family conflict (Shockley and Allen, 2007); time and location independence (Erickson and Jarrahi, 2016; Sutherland and Jarrahi, 2017; Erickson et al., 2019); and, allowing paid work to be combined with life circumstances that prevent regular work (Silver and Coldschejder, 1994).

Yet, studies on the value of flexible scheduling show mixed results, calling into question what exactly is meant by flexible scheduling (e.g., Baltes et al., 1999; Shockley and Allen, 2007). Scholars have begun to distinguish worker-controlled flexible scheduling from manager-controlled flexible scheduling (Henly et al., 2006). Many of the potential advantages of flexible scheduling are associated with worker-controlled flexibility. Manager-controlled flexibility is associated with the opposite--because from the worker’s point of view it creates uncertainty and inhibits planning (Hyman et al., 2005; Lambert et al., 2012).

The boundary between worker-controlled and manager-controlled flexibility is ambiguous as the practices of negotiating working times are bound up in workplace power relations (Lambert et al., 2012; Wood, 2016). For instance, Wood (2016) supermarket workers were formally free to declare the hours that they were available to work. In practice, however, they had to accept disruptive shifts or risk no longer being offered work. Likewise, the freelance technical contractors studied by Barley and Kunda (2011) were formally free to set their own working hours, yet, many worked through evenings and holidays because they believed this would decrease their chances of being let go and increase chances of future contracts (see also Fraser and Gold, 2001; Gold and Mustafa, 2013). Similarly, Shevchuk et al. (2019) report that Russian freelancers with high autonomy and flexibility in scheduling still choose to work long and nonstandard hours, to the detriment of their wellbeing. Most recently, Shevchuk et al. (2021) found that the online labor platform’s always-on presence constrains freelancers’ time, such that workers with clients in different time zones take on hours that are more nonstandard.

Thus, while the early literature on flexible scheduling framed flexibility as a matter of freedom from formal constraints, more recent literature highlights structural factors that constrain workers’ ability to manage their time, with the freelancer less able to control their schedule. Lehdonvirta (2018) study of online gig workers found that a worker’s ability to schedule their work was ultimately determined by two factors: the availability of gigs and the worker’s dependence on income from the gigs. If gigs are scarce, and the worker depends on income from gigs, the worker has to remain constantly on call to be ready to sign up for gigs as soon as they become available (Wood et al., 2019b). If gigs are plentiful, and the worker sees the income as extra, they will take jobs of interest and as it suites them (high flexibility).

Gendered Nature of Online Freelance Work

Online freelance work is also gendered work (Czarniawska, 2014; Ciolfi and Lockley, 2018). From at least the 1960s, scholars have been examining the working women’s perspective by looking at the broader context in which they do paid and unpaid work, including the relationship of work in the public and private sphere (Hochschild and Machung, 1989; Gerstel, 2000; Morini, 2007; Balka and Wagner, 2020). Scholars have shown ways in which work and non-work times and effort are interwoven, with boundaries gradually blurring for those with flexible arrangements (Ciolfi and Lockley, 2018; Cousins and Robey, 2015; Erickson, et al., 2019; Humphry, 2014). Analyzing the role of gender in emerging forms of work seems even more relevant given that women have historically assumed a greater share of domestic responsibilities (Barulescu and Bidwell, 2013; Blau and Kahn, 2016; Wiswall and Zafar, 2018).

Scholars are now calling for more research on the working experiences of women and other marginalized and underrepresented groups (such as racial and ethnic minorities) (Bardzell, 2010; Balka and Wagner, 2020). Balka and Wagner (2020) note that while scholarship has produced a rich body of work in many domains, including mobile or nomadic work, “These new forms of work emerge in environments in which gender-based differences in home life are likely to reinforce gender-based differences in the workplace, and historical conceptions of skill associated with (male) gender may gain foothold” (p. 44). Hannák et al. (2017) found that perceived gender and race could have significant negative consequences for individual’s search ranking as existing biases can manifest in online labor markets.

Additionally, Ciolfi and Lockley (2018) highlight that knowledge workers in work from home arrangements face changes and challenges in setting work-life boundaries. Both males and females face challenges managing their workload, prioritizing work versus family, and setting boundaries to take family and personal time. Collins et al. (2020) examined the gender gap among teleworkers in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, given “... It is possible that the increased prevalence of telecommuting may facilitate greater equality in task-sharing and the gendered division of (labor) at home.” (p. 2). Contrastingly, the authors found the pandemic has increased gender inequality in the online labor force. Mothers were more likely to reduce their working hours than fathers, with mothers of children under 13 years old facing the largest reduction in hours, even as fathers’ work hours remained largely stable. Similarly, Kalenkoski and Pabilonia (2020) found that following the first wave of COVID-19, women with younger children felt greater impacts on their working time than did single men.

Methods

The Panel Study

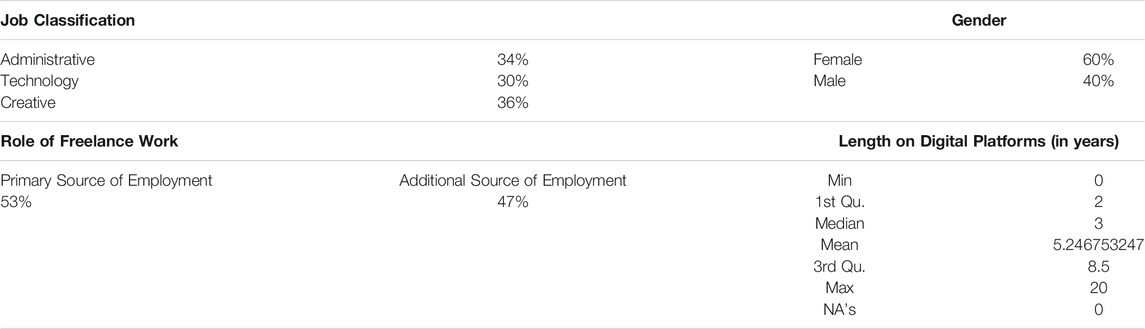

To pursue the study’s research questions, we draw data from an ongoing panel study of 68 U.S.-based freelance workers who seek work via the online labor platform Upwork (see upwork.com), the dominant online job-seeking site and gig-work platform that specializes in knowledge-based work. Of these 68, 38 participants spoke with us before, and 30 spoke with us after mid-March 2020, when we began asking how they were faring in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 1 for summary statistics). The analysis reported on here builds from interview transcripts, field notes, and survey data.

Data Collection

The panel study builds from purposive sampling of workers who pursue freelance work as a primary or secondary source of income, selected from one digital labor platform, Upwork, to minimize platform effects. The sample reflects a range of work types, skill levels, online experience, gender, race, and success online. Workers were selected across three broad categories of occupations–creative, administrative, technology. Years working on platform was used as proxy for online experience. Our gender breakdown is representative of the market, slightly skewed female (The Freelance Creative, 2016). Participants were hired through the platform and paid as they would for any job found on Upwork. Once hired, participants spent 15 min completing a survey that provided us basic demographic information and an overview of working arrangements and experiences. Once the survey was completed, the participant was interviewed via a recorded line by a research staff. The surveys were then transcribed in preparation for analysis.

As is typical in inductive and exploratory work, the interview, survey and secondary data were subject to iterative analyses, and this was used to guide incremental changes to both the survey and interview guide. The initial survey and interview guide were designed to complement one-another, including a set of questions that drove the direction of the secondary data analysis. The study’s longitudinal design and interview schedule provided us time to conduct interim analysis of the data and to reflect on changes in understanding and - importantly - allowed for the inclusion of COVID-19 related data collection.

Data Analysis

Interview and survey data were analyzed independently and then together with the secondary data. Interviews were transcribed and, in conjunction with detailed interview notes, were inductively coded, guided by the stated research questions. We then used a thematic analysis to illuminate patterns and common themes within the interview data. Initially, researchers individually reviewed all interview transcripts and developed reports on common patterns. Themes were shared in a group channel and discussed during weekly meetings, with careful note-taking and additional reading to develop a documented understanding of these themes and the data supporting them. Themes were then organized and interrogated within the context of our stated research questions. These findings are useful to the extent they provide greater insight than do rival explanations.

Findings

Data show online freelancers in our study are experiencing changes in their working arrangements. We focus on two insights relative to the first research questions: diminished work flexibility and increased earning uncertainty. We also report on the differential effects women freelance workers are experiencing, responding to our second research question. Broadly, our work aligns with previous studies showing that online freelance work is precarious, with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating this precariousness.

Diminished Work Flexibility and Increased Earning Uncertainty

Relative to the first research question regarding experiences and expectations of online freelancers grappling with the pandemic, data show there is decreased worker-controlled flexibility, as freelancers are being driven by a desperation to secure work that is rooted in the acknowledged precarity of their situation. This is true for both long-term and new freelancers, and for both full- and part-time freelancers. Freelancers indicated they faced significantly more competition, resulting in both fewer proposals accepted and lower compensation. An experienced female freelancer reflects: “I think more people are trying to find online work because they’re out of their normal jobs [...] I think there’s a lot less work to go around than usual because everyone is scrambling to make money, either while they are at home because they can’t go into their office, or while they’re laid off [...] So this current state definitely makes it more difficult” (FPAC040720201).

Some freelancers reported that the new jobs and tasks being posted also reflect lower rates, leading to a sense that clients are taking advantage of workers during the pandemic: “[...] there is going to be a lot of taking advantage of workers and their need to put food on the table” (FPAC042620201). Additionally, stable long-term clients who provided a dependable source of income are stopping current projects and not requesting new work: “The two (clients) that I lost due to this virus were long-term. One of them I had been working with for approximately a year and the other one was several months, but I don’t know what’s going to go on with them, if they’re even going to come back or anything” (FPAC042520202).

We also found that freelancers who previously relied on freelance work as a secondary source of income have become more reliant on platform-based work due to the ongoing COVID-19-related business closures (Kochhar, 2020). One participant noted: “My main business has basically dropped off. So I’ve had to really up my freelance gig work…. All my streams of income came to a stop which put me more online doing freelance work” (FPAC042620201). Combined, these findings suggest that freelancers on Upwork are witnessing their worker-controlled flexibility diminish in the face of the pandemic (in the U.S.).

Gender Magnifies the Loss of Flexibility and Rise of Uncertainty

Women freelancers in our panel were more likely to report reduced flexibility, increased uncertainty, and substantial changes to their working routines. To this point, one female panelist noted: “The other thing that has affected me is that my kids are home now, so I’m having to homeschool my two children on top of trying to stay productive and earn income for myself, so I’m definitely feeling it” (FPAC04222020).

Data show women were more likely to report having unpredictable earnings from freelance work. And since the pandemic started, the average number of freelancing hours worked decreased for respondents, with women’s reported weekly working hours dropping at nearly double the number of men’s (12.7-h and 6.5-h decrease respectively). Increased home responsibilities left some women with less time to find and secure work. “It feels a little slower than before. I am also a full-time mom, so my kids are staying home all the time now because the schools are closed. I don’t have as much time to look for work as I did.” (FPCC04142020). Our data reflect what others report: gendered differences in responsibility appear to be magnified in households with children because of COVID-19-induced lockdowns and school closures (Collins et al., 2020; Reichelt et al., 2020).

This insight must be situated in the reality that research continually re-establishes women bear a greater share of domestic responsibilities (Hochschild and Machung, 1989; Gerstel, 2000; Barulescu and Bidwell, 2013; Blau and Kahn, 2016; Wiswall and Zafar, 2018). The Institute for Fiscal Studies (2020) reports mothers doing paid work at home are more likely than fathers to be spending their work hours trying to care for children. Mothers are able to do 1 h of uninterrupted work for every 3 h done by fathers. In addition, mothers take on more chores and spend more time with children in homes where there is both a working mother and father (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020). Likewise, mothers are more likely than fathers to have left paid work and experienced a larger reduction in their hours. And, these findings are amplified in single-parent families with female heads of households. Based on our interviews, women are more likely than men to discuss their work and schedule with relation to their home and family lives. For example, women spoke of keywords such as “kid/kids,” “child,” “baby,” “son,” and “daughter” at higher rates than did men.

These findings align with existing research on the gendered nature of work. Foong et al. (2018) also report that women across the entirety of the Upwork platform earn less per hour than the median man on Upwork, even when controlling for key variables such as work experience, highest education level, and job category. And, while it is beyond the scope of our exploratory study, our findings contribute to broader discourse on precarity and the feminization of cognitive labor (per Morini, 2007).

Discussion

Findings focus on the impact of COVID-19-induced changes to the working arrangements of U.S. online freelance workers, providing insight into these new forms of labor and markets. Data illuminate differences between the realities of online freelance work and assumptions about both project-based work and online labor markets. One of the most basic assumptions, the premise of flexibility - a core reason for pursuing online freelance work, is challenged by these data. Findings show that flexibility for pursuing work is constrained by changes in people’s household arrangements. And, the flexibility to select work that aligns with one’s interests and schedules is being challenged by the whipsaw changes in the competition for online work, magnified by the increase in the number of people seeking work online (Stephany et al., 2020).

While inconclusive, given the exploratory nature of this work and the small number of participants, our data show there are decreases in weekly earnings and significantly greater difficulty in securing work since the start of the pandemic. These data also make clear that these earning losses vary by occupation. While occupational differences were not the primary focus of this study, we see the need for future research to explore these differences. For example, participants pursuing work in creative occupations such as marketing, design and writing reported experiencing precarity more often than did those in other occupational classes. Creative workers also reported a greater dependency on the wages from online and gig work while reporting the lowest access to health benefits. These workers also reported greater unpredictability of weekly earnings and experienced the largest drop in working hours when comparing post-COVID-19 data to what had been happening.

In the U.S., freelancers’ circumstances are further exacerbated by the under-regulated nature of both contingent labor and the market-making power of digital labor platforms. For example, freelancers in the U.S. are typically not eligible for unemployment, lack access to employer-provided benefits like healthcare and to labor protections provided full-time employees. Berdahl and Moriya (2021) looked at insurance coverage across all forms of non-standard work and found freelancers as the least insured of all non-standard workers. Given our data is based in a virus-centered pandemic, these data make clear the magnitude of freelancers’ precarity.

Our interviewees also reported significant decreases in the hours worked (across all occupations). We surmise the decrease may be explained by the realities of freelancers having to re-balance their household and non-work lives. This includes accommodating changing work and non-work boundaries and arrangements, with spouses and children who are home from school now competing for time and space in the household. And for our interviewees, the effects of re-configured family arrangements had a greater effect for women freelancers’ ability to do work in at least three ways. First, evidence shows that women are more likely to be pursuing freelance work - in part because of the flexibility this provides them. Second, occupations that are gendered outside of the digital labor platforms, remain gendered on these online platforms. Third, gender is visible in the profiles, experiences, and comments on these platforms (e.g., a client leaving a positive comment such as “She was incredibly responsive” leads with gender).

Conclusion

Combining survey and interview data, the work reported here provides unique empirical and nascent conceptual insights into some of the impacts of COVID-19 on the online labor market and experiences of online freelancers in the U.S. Taken together, findings suggest that the concept of work flexibility, one of the primary reasons for pursuing online freelancing, might be better understood in the context of this pandemic and market shock as work desperation. Motivated by flexibility, freelance workers pursued online work that fit with household and non-work arrangements. Online work is always precarious, as our data and findings from others make clear. But, this precarity seemed a reasonable risk to preserve flexibility, in pre-pandemic times. That is, these online workers adjusted to their risk and found ways to make it work for them. Market shocks change the calculation in ways that seem to overwhelm these plans, leading workers to eschew flexibility as they scramble for work, even in the face of less flexible household arrangements and more demands. Facing increased competition for work online, freelancers will have to bid for more work and accept lower wages, even when this strategy is not in their best interest.

Some scholars assert that online labor markets are effectively eliminating the known gender inequalities found in the traditional labor markets (e.g., Gomez-Herrera, and Müller-Langer, 2019). Our findings suggest the pandemic has disproportionately impacted female online freelancers. This is an unfortunate but repeated finding across the entire labor market spectrum (e.g. Office of Congresswoman Katie Porter, 2020; Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020; Chung and Tanja van der Lippe, 2020). For women doing technologically-mediated work remotely, the strongly gendered societal norms of household responsibilities means that women are bearing the brunt of the pandemic downturn. The implication is that the present economic travail is not only reversing decades of progress in gender equality; it is exacerbating disparities with the distribution of familial responsibilities. Simply, female online freelancers (and female workers in general) are facing a “double disruption” to their working lives and two generations of progress stands to be lost.

Data Availability Statement

Data are part of an ongoing longitudinal study and are not sharable at this time. Requests to assess the data should be directed to bWR1bm5Ac2tpZG1vcmUuZWR1.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Syracuse Univeristy IRB. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This material is supported in part by grants from Syracuse University’s office of the Vice President of Research and SOURCE, and the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. 1665386, 2121624 and 2121638. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, Syracuse University or Skidmore College.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues on the digital work research team - Alaina Caruso, Lily Feldman, Emily Michaels, Lily Moffly, Raghav Raheja, Jean-Phillippe Rancy, and Gabby Vaccaro - for helping with the data collection and analysis.

References

Aroles, J., Mitev, N., and Vaujany, F. X. (2019). Mapping Themes in the Study of New Work Practices. New Technol. Work Employment 34 (3), 285–299. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12146

Atkeson, A. (2020). What Will Be the Economic Impact of COVID-19 in the US? Rough Estimates of Disease Scenarios. Working Paper 26867). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Balka, E., and Wagner, I. (2020). A Historical View of Studies of Women’s Work. Comp. Supported Coop. Work (Cscw) 30, 251-305. doi:10.1007/s10606-020-09387-9

Baltes, B. B., Briggs, T. E., Huff, J. W., Wright, J. A., and Neuman, G. A. (1999). Flexible and Compressed Workweek Schedules: A Meta-Analysis of Their Effects on Work-Related Criteria. J. Appl. Psychol. 84 (4), 496–513. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.4.496

Barbulescu, R., and Bidwell, M. (2013). Do women Choose Different Jobs from Men? Mechanisms of Application Segregation in the Market for Managerial Workers. Organ. Sci. 24 (3), 737–756. doi:10.1287/orsc.1120.0757

Bardzell, S. (2010). Feminist HCI: taking stock and outlining an agenda for design. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1301–1310.

Barley, S. R., and Kunda, G. (2011). Gurus, Hired Guns, and Warm Bodies: Itinerant Experts in a Knowledge Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400841271

Berdahl, T. A., and Moriya, A. S. (2021). Insurance Coverage for Non-standard Workers: Experiences of Temporary Workers, Freelancers, and Part-time Workers in the USA, 2010–2017. J. General Int. Med. 36, 1997–2003. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06700-0

Blau, F., and Kahn, L. (2016). The Gender Wage gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Technical Report 21923. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. 1–77. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21913.pdf.

Ciolfi, L., and Lockley, E. (2018). From Work to Life and Back Again: Examining the Digitally-Mediated Work/life Practices of a Group of Knowledge Workers. Comp. Supported Coop. Work (Cscw) 27 (3-6), 803–839. doi:10.1007/s10606-018-9315-3

Chung, H., and Van der Lippe, T. (2020). Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Soc. Indicators Res. 151 (2), 365–381.

Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., and Scarborough, W. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender Work Organ. 28 (S1), 549–560. doi:10.1111/gwao.12506

Cousins, K., and Robey, D. (2015). Managing work-life boundaries with mobile technologies: An interpretive study of mobile work practices. Infor. Technol. People 28 (1), 34–71. doi:10.1108/ITP-08-2013-0155

Czarniawska, B. (2014). Nomadic Work as Life-story Plot. Comput. Supported Coop. Work 23 (2), 205–221. doi:10.1007/s10606-013-9189-3

Erickson, I., and Jarrahi, M. H. (2016). Infrastructuring and the challenge of Dynamic Seams in mobile Knowledge Work, Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1323–1336.

Erickson, I., Menezes, D., Raheja, R., and Shetty, T. (2019). Flexible Turtles and Elastic Octopi: Exploring Agile Practice in Knowledge Work. Comp. Supported Coop. Work (Cscw) 28 (3-4), 627–653. doi:10.1007/s10606-019-09360-1

Foong, E., Vincent, N., Hecht, B., and Gerber, E. M. (2018). Women (Still) Ask for Less. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2, 1–21. doi:10.1145/3274322

Fraser, J., and Gold, M. (2001). 'Portfolio Workers': Autonomy and Control Amongst Freelance Translators. Wes 15 (4), 679–697. doi:10.1017/s0950017001006791

Gerstel, N. (2000). The Third Shift: Gender and Care Work outside the home. Qual. Sociol. 23 (4), 467–483. doi:10.1023/a:1005530909739

Gold, M., and Mustafa, M. (2013). 'Work Always Wins': Client Colonisation, Time Management and the Anxieties of Connected Freelancers. New Technol. Work Employment 28 (3), 197–211. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12017

Gomez-Herrera, E., and Müller-Langer, F. (2019). Is There a Gender Wage Gap in Online Labor Markets? Evidence from over 250,000 Projects and 2.5 Million Wage Bill Proposals. Evid. Over 250, 19–07.

Gray, M., and Suri, S. (2019). Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hannák, A., Wagner, C., Garcia, D., Mislove, A., Strohmaier, M., and Wilson, C. (2017). Bias in online freelance marketplaces: Evidence from taskrabbit and fiverr. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing, 1914–1933.

Harmon, E., and Silberman, M. S. (2019). Rating Working Conditions on Digital Labor Platforms. Comp. Supported Coop. Work (Cscw) 28 (5), 911–960.

Henly, J. R., Shaefer, H. L., and Waxman, E. (2006). Nonstandard Work Schedules: Employer‐ and Employee‐Driven Flexibility in Retail Jobs. Soc. Serv. Rev. 80 (4), 609–634. doi:10.1086/508478

Hochschild, A., and Machung, A. (1989). The Second Shift:Working Families and the Revolution at Home. London: Penguin Books.

Horton, J. J. (2010). Online Labor Markets. Internet and Network Economics. WINE 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6484. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Howcroft, D., and Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. (2019). A Typology of Crowdwork Platforms. Work, Employment Soc. 33 (1), 21–38. doi:10.1177/0950017018760136

Humphry, J. (2014). Officing: Mediating Time and the Professional Self in the Support of Nomadic Work. Comput. Supported Coop. Work 23 (2), 185–204. doi:10.1007/s10606-013-9197-3

Hyman, J., Scholarios, D., and Baldry, C. (2005). Getting on or Getting by? Work, Employment Soc. 19 (4), 705–725. doi:10.1177/0950017005058055

Institute for Fiscal Studies (2020). Parents, Especially Mothers, Paying Heavy price for Lockdown. Available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14861.

International Labour Organization (2016). Non-standard Employment Around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects. Geneva: ILO Publications. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_534326/lang--en/index.htm.

Jarrahi, M. H., Sutherland, W., Nelson, S., and Sawyer, S. (2020). Platformic Management, Boundary Resources for Gig Work, and Worker Autonomy Comp. Supported Cooperative Work 29, 153–189. doi:10.1007/s10606-019-09368-7

Johns, T., and Gratton, L. (2013). The Third Wave of Virtual Work. Harv. Business Rev. 91 (1), 66–73.

Kalenkoski, C., and Pabilonia, S. W. (2020). Differential Initial Impacts of COVID-19 on the Employment and Hours of the Self-employed. US Department of Labor, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Office of Productivity and Technology.

Kalleberg, A. L., and Dunn, M. (2016). Good Jobs, Bad Jobs in the Gig Economy. Perspect. Work 20, 1–2.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2003). Flexible Firms and Labor Market Segmentation. Work and Occupations 30 (2), 154–175. doi:10.1177/0730888403251683

Kässi, O., and Lehdonvirta, V. (2018). Online Labour index: Measuring the Online Gig Economy for Policy and Research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 137, 241–248. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.056

Kochhar, R. (2020). Unemployment Rate Is Higher than Officially Recorded, More So for Women and Certain Other Groups. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/30/unemployment-rate-is-higher-than-officially-recorded-more-so-for-women-and-certain-other-groups/.

Kuek, S. C., Paradi‐Guilford, C., Fayomi, T., Imaizumi, T., Ipeirotis, P., Pina, P., et al. (2015). The Global Opportunity in Online Outsourcing. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lambert, S. J., Haley-Lock, A., and Henly, J. R. (2012). Schedule Flexibility in Hourly Jobs: Unanticipated Consequences and Promising Directions. Community Work Fam. 15 (3), 293–315. doi:10.1080/13668803.2012.662803

Lehdonvirta, V. (2018). Flexibility in the Gig Economy: Managing Time on Three Online Piecework Platforms. New Technol. Work Employment 33 (1), 13–29. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12102

Malone, T. W. (2004). The Future of Work: How the New Order of Business Will Shape Your Organization, Your Management Style, and Your Life. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

McKayPollack, C. E., and Fitzpayne, A. (2019). Automation and a Changing Economy, the Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. Available online at: https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2019/04/Automation-and-a-Changing-Economy_The-Case-for-Action_April-2019.pdf Last accessed on April 19, 2020).

McKibbin, W. J., and Fernando, R. (2020). The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/20200302_COVID19.pdf.

Moreira da Silva, J. (2019). “Why You Should Care about Unpaid Care Work. ”OECD Development Matters. Available at: https://oecd-development-matters.org/2019/03/18/why-you-should-care-about-unpaid-care-work/.

Morini, C. (2007). The Feminization of Labour in Cognitive Capitalism. Feminist Rev. 87 (1), 40–59. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400367

O'Farrell, R., and Montagnier, P. (2019). Measuring Digital Platform‐mediated Workers. New Technol. Work Employment 35 (1), 130–144. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12155

Office of Congresswoman Katie Porter (2020). The Burden of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women in the Workforce. Available online at: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://porter.house.gov/uploadedfiles/final-_women_in_the_workforce.pdf&sa=D&ust=1608050538651000&usg=AOvVaw3Gq92BlYO9bPp0gA77cp0l Last accessed on December 15, 2020).

Pichault, F., and McKeown, T. (2019). Autonomy at Work in the Gig Economy: Analysing Work Status, Work Content and Working Conditions of Independent Professionals. New Technol. Work Employment 34 (1), 59–72. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12132

Reichelt, M., Makovi, K., and Sargsyan, A. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Inequality in the Labor Market and Gender-Role Attitudes. Eur. Societies 23, S228-S245. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1823010

Shevchuk, A., Strebkov, D., and Davis, S. N. (2019). The Autonomy Paradox: How Night Work Undermines Subjective Well-Being of Internet-Based Freelancers. ILR Rev. 72 (1), 75–100. doi:10.1177/0019793918767114

Shevchuk, A., Strebkov, D., and Tyulyupo, A. (2021). Always on across Time Zones: Invisible Schedules in the Online Gig Economy. New Technol. Work Employment 36 (1), 94–113. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12191

Shockley, K. M., and Allen, T. D. (2007). When Flexibility Helps: Another Look at the Availability of Flexible Work Arrangements and Work-Family Conflict. J. Vocational Behav. 71 (3), 479–493. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.006

Silver, H., and Goldscheider, F. (1994). Flexible Work and Housework: Work and Family Constraints on Women's Domestic Labor. Social Forces 72 (4), 1103–1119. doi:10.2307/2580294

Stephany, F., Dunn, M., Sawyer, S., and Lehdonvirta, V. (2020). Distancing Bonus or Downscaling Loss? the Changing Livelihood of Us Online Workers in Times of COVID‐19. Tijds. voor Econ. en Soc. Geog. 111, 561–573. doi:10.1111/tesg.12455

Stephany, F., Kässi, O., Rani, U., and Lehdonvirta, V. (2021). Online Labour Index 2020: New ways to measure the world’s remote freelancing market. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.09148.

Sundararajan, A. (2016). The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd‐Based Capitalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Sutherland, W., and Jarrahi, M. H. (2017). The Gig Economy and Information Infrastructure, Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1, 1–24. doi:10.1145/3134732

The Freelance Creative (2016). ‘Pretend You’re a White Male’: Freelance Writing’s Gender Problem. Available at: https://contently.net/2016/04/13/voices/frontlines/pretend-youre-a-white-male-freelance-writings-gender-problem/.

Vallas, S., and Schor, J. B. (2020). What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 46, 273–294. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054857

Wenham, C., Smith, J., and Morgan, R. (2020). COVID-19: the Gendered Impacts of the Outbreak. Lancet 395 (10227), 846–848. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30526-2

Wiswall, M., and Zafar, B. (2018). Preference for the Workplace, Investment in Human Capital, and Gender. Q. J. Econ. 133 (1), 457–507. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx035

Wood, A. J. (2016). Flexible Scheduling, Degradation of Job Quality and Barriers to Collective Voice. Hum. Relations 69 (10), 1989–2010. doi:10.1177/0018726716631396

Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., and Hjorth, I. (2019a). Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work, Employment Soc. 33 (1), 56–75. doi:10.1177/0950017018785616

Keywords: online labor market, freelance work, precarity, COVID-19, gender, knowledge work

Citation: Dunn M, Munoz I and Sawyer S (2021) Gender Differences and Lost Flexibility in Online Freelancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Sociol. 6:738024. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.738024

Received: 08 July 2021; Accepted: 16 August 2021;

Published: 31 August 2021.

Edited by:

Jason Heyes, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomReviewed by:

Denis Strebkov, National Research University Higher School of Economics, RussiaAndrea M. Fumagalli, University of Pavia, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Dunn, Munoz and Sawyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Dunn, bWR1bm5Ac2tpZG1vcmUuZWR1

Michael Dunn

Michael Dunn Isabel Munoz2

Isabel Munoz2