95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sociol. , 15 June 2018

Sec. Gender, Sex and Sexualities

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2018.00016

There is a gap in the literature regarding police officers' attitudes about vice, specifically prostitution. Scholars should study this topic because police are interacting with drug dealers and drug users, prostitutes, and Johns, and gamblers and bookies regularly. Additionally, how police perceive prostitution is likely to influence how they enforce laws prohibiting it. This paper presents survey items measuring police officers' attitudes about prostitution related offenses and examines the relationships between officers' attitudes toward prostitution and their personal as well as professional characteristics. Responding officers displayed fairly serious and punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses. Respondents believed that prostitution was a serious problem in their city and that it leads to more serious crimes. Demographic characteristics of officers such as age, gender, political ideology, and education had more influence on prostitution attitudes than police characteristics such as experience with the vice/narcotics unit. Policy implications derived from the findings are discussed.

The criminal law expresses societal values and provides boundaries of acceptable behavior (Walker, 2008). Acts such as murder, rape, robbery, assault, and theft of or damage to property are perceived to negatively affect society and are worthy of prohibition and sanctions. Evidence suggests that crimes producing physical harm are perceived as the most serious crimes and deserving of the most serious sanctions (Cullen et al., 1982; Wolfgang et al., 1985). Property crimes, on the other hand, are perceived as less serious and therefore are sanctioned less severely (Evans and Scott, 1984; Wolfgang et al., 1985; Douglas and Ogloff, 1997). Property and violent crimes are met with sanctions because they involve both an offender and a victim. In these cases, someone is being subjected to unwanted and harmful force (i.e., violence) or fraud (i.e., theft) at the hands of an offender.

Some behaviors, on the other-hand, do not impart any harmful force or fraud on an unwilling person, yet they are defined in criminal statutes as illegal. The laws prohibiting these behaviors exist because they reflect the public's moral sentiment (Patrick, 1965). Drug use, prostitution, and gambling are also commonly referred to as “vice crimes” because they represent behavior that the public views as contrary to what is moral and virtuous. These “victimless” or “vice” crimes are not universally condemned. The terms vice, victimless, and public order crimes are often used interchangeably, however it could be argued that these offenses are not truly victimless crimes as an indirect victim may often be identified. Solving such debate is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, the justification for prohibiting these behaviors lies within morality and legislating morality can be problematic at times because morality varies across the population. Packer (1968) questioned whose morality is to be legislated, and how are these laws to be enforced?

The police are tasked with enforcing the law including vice crime laws. They deal with these types of offenders on a regular basis. However, research on police perceptions of vice crime, and prostitution offenses in particular, is quite sparse, particularly when it comes to assessing nuances in and correlates of police officers' attitudes of the vice behaviors themselves, as opposed to enforcement tactics or policies directed toward controlling drug, prostitution, and gambling crimes (see Petrocelli et al., 2014). One study has directly investigated police officers' perceptions toward general vice crimes and perceived appropriate sanctions for violating these offenses (Wilson et al., 1985). This study took the first steps to investigate police perceptions of vice crime and the correlates therein. Additionally, the current study used a novel approach to examine how serious of a crime officers view prostitution as well as how punitive they are toward it. However, many questions are still left unanswered and there remains opportunity for future research in this area considering the fact that our behaviors are influenced by our perceptions. It therefore follows that how the police view prostitution offenses will have an impact on how they enforce the law.

The lack of research involving police populations is unfortunate because the police can offer valuable insight into this topic and may have some influence on policy. After all, they are the ones arresting drug users and dealers, prostitutes and Johns, and gamblers, and bookies. What is more, there are no studies known to the author that measure police officers' attitudes about vice crimes, or prostitution in particular, while controlling for various demographics, religious beliefs, and political ideologies. Research has shown that attitudes about various vice behaviors are related to religion and politics among the general population (see Stylainou, 2003; Kalant, 2010). It is important to control for these factors in order to obtain an accurate picture of police officers' attitudes and perceptions toward unsavory behaviors. It is important to note that such ideological objections to prostitution are extra-legal objections.

Additionally, it is important to examine police officers' attitudes toward vice crime because the police have wide discretion available to them in how they enforce the law. Research shows that police officers' perceptions toward suspects, crime, crime control policies, and the law influence how they exercise discretion (Worden, 1989; Gaines and Kappeler, 2005). It is likely the case, therefore, that perceptions about vice have an effect on officer discretion when in contact with a vice offender. Moreover, it could be the case that certain police officers treat such offenders more punitively based on extra-legal factors such as the officer's moral compass. Differential treatment of offenders at the hands of agents of the criminal justice system for non-relevant reasons is likely to damage the system's credibility (Tyler, 1990). Consequences of illegitimate differential treatment may be disastrous to the end goals of the criminal justice system.

The purpose of this research is to extend the work done by Wilson et al. (1985) regarding police officers' attitudes toward prostitution (attitudes toward other vice crimes like drug use and gambling are beyond the scope of this paper, although a worthwhile avenue of inquiry) First, a survey designed to measure police officers' attitudes toward prostitution was crafted. Second, data derived from the survey were analyzed and the results presented. Lastly, policy implications derived from the findings of this study are discussed. The subsequent pages will first review relevant literature concerning the topic at hand followed by a description of the methods implemented in this study and a discussion of the findings and conclusions.

Historically, states have banned certain sex-related activities, notably prostitution, adultery, homosexuality, and sodomy. Up until the mid-1980s, 13 states outlawed unmarried couples living together per “fornication” laws (Walker, 2008). It was not until 2003 that the Supreme Court decided laws against sodomy were unconstitutional [Lawrence vs. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)]. In contemporary times, prostitution is the only moral-based sex offense still enforced in America, with minor exceptions like “bunny ranches” in rural Nevada counties.

Notably, religion is an important factor when forming attitudes about prostitution. People who are more religious, or belong to more traditional religious groups, tend to view prostitution less favorably (Stylainou, 2002). Differences among gender also exist. Cotton et al.(2002 p. 1793) found that 26% of men thought “there is nothing wrong with prostitution” as compared to just 10% of women. Men were also less likely to believe that prostitutes were victims of pimps. The study also showed that rape myths were correlated with prostitution myths. Just as people use rape myths to justify rape, prostitution myths are used to justify violence against prostitutes.

Research has shown that prostitutes are routinely subjected to poverty, violence, harassment, discrimination, and hazardous environments (Farley and Barkan, 1998; Farley and Kelly, 2000; Weitzer, 2005, 2007). This helps explain unfavorable attitudes toward prostitution by co-existing with it; however, some critics argue that these undesirable correlates are due to the nature of the sex market being illegal and not necessary because of the behavior.

Not all prostitutes work on street corners in rough neighborhoods. The stereotypical “street” prostitute recalls connotations of drug addicts and runaways, pimps and violence, leading to negative perceptions about prostitution. However, most prostitutes are regular people supplying their income as nurses or students with the sex trade. “Call-girl” or escort prostitution is more business oriented and can cost customers toward $500 per hour (Goldsmith, 1993). Street prostitutes resort to survival sex via prostitution to support their drug habits and pay for living expenses (Weitzer, 2005, 2007). It is common for street prostitutes to report that they wish they could leave the industry (Farley and Barkan, 1998). On the other hand, call-girls who work out of brothels, strip clubs, or massage parlors often report high levels of job satisfaction because of the autonomy, pay, feeling of empowerment, and relatively safe working environment with low risk of arrest (Lucas, 2005; Weitzer, 2005, 2007). Law enforcement activities are almost exclusively focused on street prostitution. Street prostitutes only make up 10–20% of all money-for-sex workers, but almost all prostitutes and Johns arrested in the U.S. are from the street (Cooper, 1989; Alexander, 1998; Weitzer, 2005, 2007).

There has been a recent push by law enforcement to target the supply side of prostitution by arresting those who seek out prostitutes. Female officers play the part of decoy prostitutes to arrest Johns who attempt to purchase sex (Dodge et al., 2005; Baker, 2007). Baker (2004) detailed how undercover female officers posing as prostitutes understand the harsh nature of being a prostitute. Although some officers felt that playing a prostitute was interesting, fun, and rewarding, many others felt otherwise. Some officers were subjected to harassment and dangerous situations where they were alone and vulnerable. Additionally, many felt that the undercover work and prostitution in general was degrading.

Another intervention designed to address the supply side of prostitution is the advent of “John schools.” These programs are diversionary programs designed to change Johns' attitudes toward prostitution by educating them of the risks and negative effects of prostitution. These programs have gained wide popularity throughout the U.S. and Canada and seem to have measurable success. Research shows that Johns who have been through the program were less likely to believe prostitution myths (Kennedy et al., 2004).

Of particular interest to this research are the attitudes of police officers about vice. They are the ones enforcing such laws and it makes sense that researchers should investigate their perceptions of vice offenses. However, only one study was found that directly measured police officers' attitudes toward vice crime in the American context (Wilson et al., 1985).

Wilson et al. (1985) surveyed a small suburban police department in a metropolitan area. The survey measured general attitudes toward vice crimes via a nine-item Likert scale and general punitiveness toward vice crimes via a 25-item intervention scale. The findings related to prostitution are discussed here.

Wilson et al. (1985) found that, in general, respondents did not feel that vice was a serious problem in their city and did not require immediate attention from the police, although an overwhelming majority of officers agreed that vice leads to more serious crime. The researchers found no support for devoting more resources to control vice. Police officers also did not care to “legislate morality.” Instead, a “non-interventionist” position was held among the sample, with officers believing that the department should not intensify its efforts to enforce public order laws.

The study also showed that variation in punitiveness exists between the types of victimless crimes. Almost 20% of the sample felt that “call-girl” prostitution should not be enforced. Compared to “street” prostitution, only about 6% of the sample supported non-enforcement. A possible reason for this finding is that officers viewed “street” prostitution as being more visible to the public and being more related to other street crimes and drug use as compared to “call-girl” prostitution. However, buying a prostitute scored lower than being a prostitute. Almost 32% of officers supported non-enforcement of “Johns.” On the other hand, promoting prostitution, or “pimping,” was viewed as deserving harsher treatment than prostitution. Nearly three-quarters of officers said that pimps (who perhaps are the crux of the criminogenic drive underlying prostitution) deserve imprisonment.

Finally, multivariate analysis showed that age was the only significant predictor of attitudes toward vice and appropriate interventions. In general, younger officers were less punitive. This may be because younger officers were more liberal, perhaps coming from a more progressive generation. It also may be that the longer a person is an officer, the more punitive his or her attitudes became because of the perceived negative consequences associated with vice.

A few recent studies worth noting contribute to our understanding of how agents of the criminal justice system view prostitution. Franklin and Menaker (2014) found that probation officers have similar views about prostitution compared to the general public and that prostitutes are at least partially responsible for their victimization for choosing the life. Interactions with police officers are often the initial contact prostitutes have with the legal system. Halter (2010) surveyed police officers and found that they view prostitutes as choosing to work in the underground sex market and are perceived as offenders rather than victims. Viewing prostitutes punitively as offenders may lead to the denial of services and support that ameliorate the latent sources of prostitution. What is more, the relationship between police and prostitutes varies widely across location. Some departments aggressively enforce all forms of prostitution, where other departments have a de facto decriminalized approach to call-girl prostitution. As such, in places where prostitution is aggressively policed, the relationship between police and prostitutes can be tenuous. Some departments, however, have a mutually beneficial relationship with prostitutes. In such cases, the police may turn a blind eye to a prostitute's activities in exchange for information that may lead to the arrest of people suspected of more serious crimes such as pimps, gang members, and drug traffickers (see generally; Weitzer, 2010).

The purpose of this paper is to extend and refine the initial study by Wilson et al. (1985) but focuses specifically on police officers' attitudes about prostitution related offenses. The following paragraphs outline the research methods used in this study.

(Q1) What factors influence officers' perceptions of prostitution offense seriousness? (Q2) What factors influence their punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses? (Q3) Is there a relationship between their perceptions of prostitution offense seriousness and their punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses? (Q4) What factors moderate that relationship? (Q5) How has being a police officer changed officers' views of prostitution?

A survey instrument that measures police officers' attitudes toward vice and factors regarding demographics and experience with law enforcement was used to collect data from participants. This survey used the Wilson et al. (1985) instrument as a springboard. The current survey borrowed some of the Wilson et al. (1985) instrument items verbatim and generally followed a similar structure. Some items on the current survey altered the language from the prior survey by replacing the word “vice” with “prostitution.” Several survey items included in the current survey where derived from prostitution acceptance and rape myth scales as well (see Sawyer et al., 1998; Cotton et al., 2002). Additionally, the current survey also added several novel items to obtain more nuanced information for factor analysis. The survey in its entirety along with a more complete discussion on the merging of the original source surveys and novel survey items created by the author can be found in Jorgensen (2014). Only the survey items regarding prostitution, demographics, and experience in law enforcement are presented in this paper. The survey items will be discussed below in the descriptive statistics section.

The sampling frame came from a large metropolitan police department located in the South that serves a city 1.2 million citizens. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey. All appropriate ethical guidelines and procedures for social science survey research were observed for this project. The Office of Research Compliance at the University of Texas at Dallas reviewed and approved the research parameters. After reading the study's statement of purpose, informed consent was obtained from voluntary participants via the following language: To agree to participate in this study click on the “Continue” button below. Given the constraints of the research by the department, a probability sampling method was not possible. As such, the data come from a non-probability convenience sample. Invitations to participate in this survey research were sent via official city email from a Deputy Chief to all of the 3,516 sworn officers in the department. The language in the email and the link to the SurveyMonkey website were provided by the author. To maximize responses, the total design method for survey research was implemented (see Dillman, 2007). Of the roughly 3,500 sworn officers invited to take the survey, 314 of them responded, for an initial estimated response rate of just under 10%. It was not possible to calculate an exact response rate because the number of officers who opened and read the invitation was not known. The proper denominator to use for calculating a response rate in this situation would be the number of officers who actually opened and read the email inviting them to participate in the survey and this number was not available. The invitation to participate in this survey was a mass email to officers from a Deputy Chief. It could be the case that many, if not most, officers simply ignored the mass email like university professors ignore mass emails from the university president or provost. What is more, it is not uncommon for studies using police officer samples to have low response rates (see Klockars et al., 2001). A few aspects of the sample police department are also worth noting. There was no indication that prostitution was uncharacteristically rampant within the city the sample department serves compared with other large metropolitan cities in the United States, although vice (prostitution typically being included in the term) is a common typology of offense to which police departments devote significant resources to address. Most police departments of a substantial size, including the sample department in the present study, have vice/narcotics units. Additionally, the sample department from this study differs from the sample police department in Wilson et al. (1985) by being from a larger city and having a more diverse police force. During the year of when the data were collected the city in which the sample department serves had a violent crime rate of 375 violent crimes per 100 K residents and a property crime rate of 470 property crimes per 100 K residents. Both of these rates were much higher than national averages. Lastly, the sample police department has a strong and mutually beneficial relationship with the local universities and often allows research to be conducted there.

Missing data were addressed via listwise deletion which is an appropriate technique commonly used in data analysis and is the default option for the statistical package used in this research. Nearly 50 respondents who started the survey ended their participation within the first eight questions of survey. It is not recommended to impute missing data for observations from respondents who ended their participation in the survey shortly after it began (Acock, 2005). Respondents who finished the survey rarely did not answer every question. These missing data points were also dealt with via listwise deletion and only accounted for a handful of cases. The final sample sizes in multivariate models ranged from 206 to 235 which is large enough for a meaningful analysis.

As noted above, the data came from a non-probabilistic convenience sample. The sample of responders was different than the population of officers in several regards. Whites were overrepresented while blacks and Hispanics were underrepresented. Additionally, there was disparate representation based on rank. The lowest ranking officers were underrepresented while lieutenants, sergeants, and senior corporals were overrepresented in the sample. Officers holding a bachelor's degree or higher were also overrepresented in the data. To make respondents more akin to the population of police officers and to limit bias as much as possible, the sample data were weighted via the inverse probability weight (Lee and Forthofer, 2006).

Latent factor variables were constructed to measure novel constructs that were not directly measureable (Carmines and Zeller, 1979). Factor scores were calculated for the latent factors variables. The novel latent constructs included attitudes toward prostitution seriousness and punitiveness toward prostitution offenses. Table 2 below shows the survey items used to create the prostitution seriousness factor and Table 3 below shows the items used to create the prostitution punitiveness factor. The correlation coefficient for these two factor variables was 0.58. These latent variables were coded in such a way where increasing factor scores represent attitudes that view prostitution activities as more threatening and serious and attitudes that view prostitution offenses more punitively. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin statistics indicated that the measures were acceptable (0.78 and 0.60, respectively). Survey items with weak factor loadings <0.3 were dropped from the latent factors. The correlation coefficient, KMO statistics, and factor loadings >0.3 for these latent variables indicate a valid and reliable measurement strategy (Carmines and Zeller, 1979).

Aspects about the respondent's demographics and their career as a law enforcement officer were captured and used as covariates and controls. Measures include tenure as a police officer, rank, vice/narcotics assignment, tenure in vice/narcotics, job dissatisfaction, age, ethnicity, gender, marriage, children, education, religion, religious commitment, and political ideology.

Descriptive statistics and OLS regression models were employed to analyze the data. To answer the first and second research questions, an OLS model of prostitution seriousness attitudes, followed by an OLS model of prostitution offense punitiveness was regressed on the covariates listed above. Next, an OLS model regressed prostitution offense punitiveness (the dependent variable) on prostitution seriousness attitudes (the independent variable) while holding other covariates constant. Interaction effects were then investigated. Multiplicative interaction terms were created to test which significant factors, if any, moderated the relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and prostitution offense punitiveness. The last research question was assessed via summary statistics. The proper diagnostic protocols were implemented to assess the assumptions for OLS regression. Outlying data points were truncated to the third standard deviation. Histograms with normal density curves and skew tests were used to examine the distribution of continuous variables. Two-way scatterplots were estimated to assess homoscedasticity. Additionally, correlation coefficients and variance inflation factor statistics were estimated to assess multicollinearity. Interaction terms were mean-centered.

Descriptive and summary statistics regarding respondent demographics and experience as a law enforcement officer are presented in Table 1 below. Demographic measures included age, ethnicity, gender, marriage, children, education, political ideology, religion, and religious commitment.

Descriptive statistics for the individual survey items are discussed below. Table 2 displays the results of these items. About 15% of the sample agreed that there is nothing wrong with prostitution. More than half of the officers believed that pimps caused most of the problems with prostitution and that prostitutes got off to a bad start in life. Eighty percent of the sample agreed that prostitutes are drug addicts. An overwhelming majority of officers agreed that prostitution is a serious problem in their city, prostitution leads to more serious crime, and prostitution will always exists regardless of law enforcement activities. Officers tended to view prostitution offenses fairly seriously and that law enforcement responses to such offenses are not effective.

Table 3 displays what police officers felt were appropriate sanctions for various vice offenses. More than two-thirds of officers believed that street prostitution deserves incarceration. Officers were a little less punitive toward call-girl prostitution. Nine percent of the sample believed that street prostitution should not be treated as a crime. Sixteen percent believed that call-girl prostitution should not be treated as a crime. Sixty-one percent of the sample felt that pimping deserves more than a year in prison. Less than half of the officers believed that buying a street prostitute deserves incarceration, while 11% believed that it should not be treated as a crime. Sixteen percent of the sample believed that buying a call-girl prostitute should not be treated as a crime. Police officers in this sample tended to have fairly punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses.

Table 4 below presents the results of the OLS model of prostitution seriousness attitudes. Interestingly, having ever been in the vice/narcotics unit was associated with a decrease in prostitution seriousness attitudes (B = −0.20), while an increase in the number of years served in the vice/narcotics unit was associated with an increase in prostitution seriousness attitudes (B = 0.22). Job dissatisfaction was negatively related to prostitution seriousness attitudes as was gender and age (B = −0.26, B = −0.17, B = −0.18, respectively). Being less religious was associated with a decrease in prostitution seriousness attitudes (B = −0.18). The model explained 18% of the variance in prostitution seriousness attitudes. Additionally, regression assumptions were met.

Table 5 below displays the results of an OLS regression model of prostitution punitiveness attitudes. Job dissatisfaction, education, liberal, and male were all significant (p < 0.05). Being less satisfied with the job in law enforcement was associated with a decrease in prostitution punitiveness attitudes (B = −0.20). Those who achieved higher education were also less punitive toward prostitution offenses (B = −0.21). Additionally, those who more liberal had less punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses (B = −0.21). Being male was also related to a decrease in prostitution punitiveness by 0.21 standard deviation as compared to female officers. Diagnostics indicated that regression assumptions were met, and the model explained 17% of the variance in prostitution punitiveness attitudes.

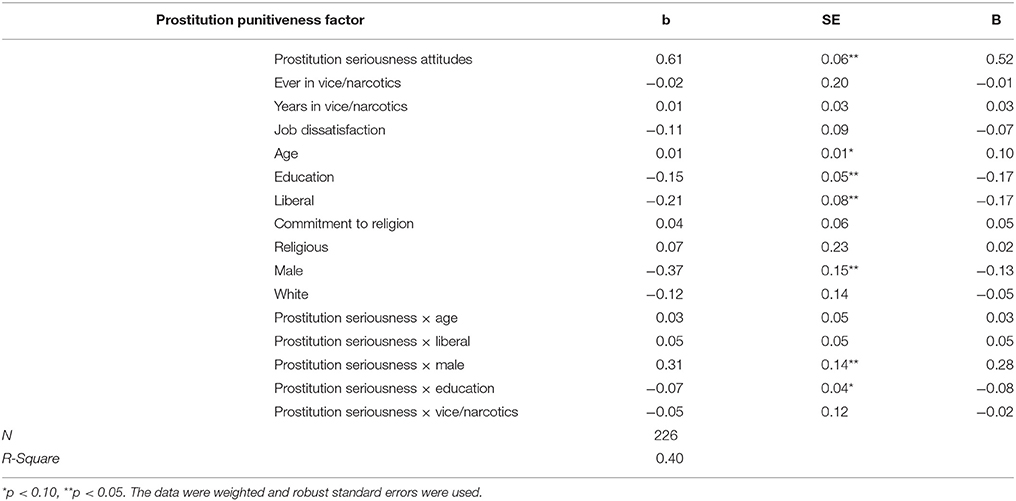

Table 6 below summarizes the output of OLS regression models estimating the relationship between the prostitution seriousness factor and the prostitution punitiveness factor. The relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and prostitution punitiveness attitudes was strong as expected (B = 0.52, p < 0.01). Being more educated, being more liberal, and being male was associated with decreased punitiveness toward prostitution while age was positively related to such attitudes.

Table 6. OLS regression estimating the relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and prostitution punitiveness attitudes.

Two of the interaction terms were significant in this model. The effect of prostitution seriousness attitudes on prostitution punitiveness attitudes was stronger for males than females. Additionally, education moderated the relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and prostitution punitiveness attitudes where the effect was stronger for those less educated.

Generally speaking, officers examined in this study had fairly serious attitudes regarding prostitution. Officers felt that prostitution leads to more serious crime, that prostitution is problematic in their city, and that the police should be doing more to control prostitution.

Respondents were also quite punitive toward vice related offenses. Generally, officers favored putting prostitution offenders behind bars. Most police officers reported a change in their attitudes toward prostitution offenses as a result of becoming a police officer. Some officers became more punitive (36%), some became more lenient (22%), while many reported no change (42%).

A few of the covariates investigated in multivariate models were routinely associated with prostitution attitudes. However, several covariates were routinely insignificant or rarely significant predictors even though they were expected to be. Being religious (as opposed to being non-religious) was never a significant predictor in the analysis. This is a curious finding because much of the literature on attitudes toward vice among the general public has found that religiosity is strongly associated with negative perceptions toward vice activities, including prostitution (Stylainou, 2002, 2003, 2004). The reason for the non-significant findings in these models may be due to the lack of religious variation within the sample. The overwhelming majority of the sample was religious. Although being religious did not have an impact on prostitution attitudes, commitment to religion commonly did have a significant effect. There was a moderately strong relationship between becoming less committed to religion and viewing prostitution offenses less seriously and punitively. Similarly, being more liberal was commonly and moderately associated with less serious and punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses. These findings make intuitive sense. Liberals do not have the reputation of being a values voting constituency as compared to conservatives. Along similar lines, higher education attainment was also a moderately powerful predictor of prostitution attitudes and punitiveness. These variables having similar effects on prostitution attitudes and punitveness are understandable because people who are more educated also tend to be more liberal (Kanazawa, 2010).

The effects of age, gender, and ethnicity on prostitution attitudes were examined in this study. Male officers generally had less serious and punitive views toward prostitution compared to female officers. These findings are understandable because men are more likely to believe in prostitution myths and buy prostitutes (Cotton et al., 2002). Additionally, the police subculture is typified by machismo (Crank, 2004). Masculinity is valued among policing circles and may reinforce gender stereotypes of male sexual dominance and female sexual receptivity. It could be the case that male officers view females using sex as an innocuous and age old means of quid pro quo. Older officers viewed prostitution offenses less seriously, yet had more punitive attitudes toward such offenses. This is a curious finding. It may be that the old guard simply have more punitive attitudes regarding crime across the board. Ethnicity, however, played no role in predicting attitudes toward prostitution.

Satisfaction with the job as a police officer was a moderately strong predictor of prostitution attitudes. Being less satisfied as a cop was associated with less serious and less punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses. This may be due to the cynicism officers sometimes develop during their career (see Regoli and Poole, 1979). It may be the case that officers feel that enforcing prostitution offenses are not that important and that resources would be better spent trying to control more serious crime. In short, officers may feel that they are fighting the wrong fight causing them to become more cynical and less satisfied with their job in law enforcement.

It is theoretically reasonable that serving in the vice/narcotics unit should have an influence on officers' attitudes toward prostitution. The data from this research suggested that this may not always be the case. Items measuring vice/narcotics experience were only significant predicting prostitution seriousness attitudes. They played a much smaller role than demographic factors. What is more, the effects of vice/narcotics experiences were not consistent. Having ever been in the vice/narcotics unit was associated with decreased views of prostitution seriousness. On the other hand, longer tenure in the vice/narcotics unit was associated with increased views of prostitution seriousness. This is a curious finding that is hard to explain. It may be that simply having ever been in the vice/narcotics unit make officers realize that these types of offenses are not a serious threat to society (as compared to more serious crimes) and so they leave the vice/narcotics unit after a short period of time. The average tenure in the vice/narcotics unit in this sample was a little over 1 year. On the other hand, it could also be the case that officers who feel they have a moral obligation to fight moral based crimes self-select into longer periods of time in the vice/narcotics unit. In this case, officers who came into the vice/narcotics already had serious and punitive attitudes toward vice and they were on a mission to fight these types of crimes. However, it could also be the case that those who have been in the unit longer periods of time have more serious attitudes toward prostitution because they have more experience dealing with these types of offenders and have had more opportunity to see first-hand the harms caused by such offenses.

The relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and punitiveness attitudes was moderated by gender and education. This relationship was stronger for males and for the less educated. Generally speaking, moderators played a small role in this analysis. This suggests that the relationships between prostitution seriousness and prostitution punitiveness attitudes were robust and consistent across varying scores of other indicators included in multivariate models.

This study expanded upon the study by Wilson et al. (1985). One of the limitations of the Wilson et al. study was the homogenous sample. Nearly all of the officers in their study were white males. As such, their study could not investigate gender and ethnicity differences, a fact the authors lamented. The present study was able to decompose such effects by sampling a much larger and socially diverse police department from one of the largest cities in America. Both samples viewed street prostitution fairly similarly. However, the officers from this study were more punitive toward call-girl prostitution compared to officers from the Wilson et al. study. Additionally, officers from this sample were more punitive toward “pimping” than those from the Wilson et al. study. More than half of the officers from this study felt that incarceration was an appropriate sanction for buying a prostitute, whereas only 29% of officers from the Wilson et al. study thought so. Time, geographic location, and city context could help explain why the officers from this study had more serious and punitive attitudes toward prostitution compared to the officers from the Wilson et al. sample.

This study added to our understanding of how police officers view vice. However, as with all studies, this study had a several notable limitations. First, the survey instrument used in this study is imperfect. As noted earlier, several revisions could be made to the survey that could reduce measurement error. Similarly, the survey may be incomplete. The instrument surely did not capture data on every possible variable related to the outcome variables of interest in this analysis. In short, the analytical models in this research may suffer from omitted variable bias.

The sample also presents a limitation in this study. Due to uncontrollable constraints put on this research project, it was not possible to derive a probability sample. In the end, the sample used here was a convenience sample. Such a sample makes generalizing the findings not possible. Instead, the findings only relate to the limited respondents examined. It therefore cannot be said that the findings from this study are representative of the police department from which the sample of officers come from as a whole. Additionally, the data from this sample were cross-sectional.

The most significant limitation in this study was the unknown but probably low response rate. Also, many respondents dropped out of the survey shortly after beginning it. Due to listwise deletion procedures in multivariate models, the total number of respondents was even fewer. However, researchers must do the best they can with what they have. Important information can still be gleaned in cases of low response rates.

For unknown reasons, the research investigating police officers' attitudes toward vice crime, including prostitution, is underdeveloped. Criminologists have not devoted much time to unpacking this topical area, even though this phenomenon could have important ramifications. Some studies have looked into police officers' perceptions about law enforcement responses to drug crimes (Petrocelli et al., 2014); however, only one study was found that attempted to study the nuance of police officers' attitudes about vice-related behaviors specifically (Wilson et al., 1985).

Several conclusions can be made from this analysis. Officers from this sample had fairly serious and punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses. The relationship between prostitution seriousness attitudes and prostitution punitiveness attitudes was strong, and the strength of that relationship changed across gender and education levels. Characteristics of individual officers, such and education attainment, religiosity, gender, and political ideology, were more important factors associated with prostitution attitudes than several law enforcement indicators such as experience with the vice/narcotics unit. However, cops less satisfied with their careers viewed prostitution less seriously and less punitively. Finally, it was more common for officers to develop more punitive attitudes toward prostitution offenses as a result of becoming a police officer than it was to develop more lenient attitudes.

It is important to continue this avenue of research. How the police view prostitution offenses may influence policy decisions. Legislators can turn to the police for advice regarding criminal legislation. Officers may feel that prostitution is a serious criminal problem that warrants harsher legislation. However, the opposite may also be true. Officers may view these crimes as not very serious (compared to other crimes), and that the police should focus on controlling more serious forms of street crime instead of squandering precious policing resources.

Additionally, the police have wide discretion in how they enforce the law, and how that discretion is used is influenced by police officers' attitudes and perceptions (Worden, 1989). Examining how the police view prostitution can help researchers understand how police use discretion regarding such offenders. Wide discretion may be problematic in terms of fair and equal treatment of citizens. For example, one person may be arrested for soliciting a prostitute while another person is not arrested for the same offense simply because of the police officer's preconceived attitudes toward prostitution based on extra-legal factors such as the officer's politics. Whether or not someone is arrested for a vice crime, like solicitation, may be contingent on several factors including the political ideology, education level, gender, or religious commitment of the police officer. This may be viewed as unfair and unequal treatment. Fairness and equality are hallmarks of democracy and procedural justice, the basis of police legitimacy (Tyler, 1990). As such, people should be treated fairly and equally when dealing with the police. Therefore, the police should be cognizant of their own attitudes and perceptions toward prostitution. They should also be aware that these attitudes and perceptions influence how they behave on the job. Officers should be trained to remain objective when dealing with such offenders so that their own subjective views do not cause unfair and unequal treatment of citizens. Police managers should communicate to their officers that such extra-legal factors should not influence their discretion.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Internal Review Board and the Office of Research Compliance at the University of Texas at Dallas with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Office of Research Compliance at the University of Texas at Dallas.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. J. Marr. Fam. 67, 1012–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Alexander, P. (1998). “Prostitution: a difficult issue for feminists,” in Sex Work: Writings by Women in the Sex Industry, 2nd Edn., eds F. Delacoste and P. Alexander (San Fransisco, CA: Cleis Press), 184–230.

Baker, L. M. (2004). The Information needs of female police officers involved in undercover prostitution work. Inform. Res. 10:209.

Baker, L. M. (2007). Undercover as sex workers. Women Crim. Justice 16, 25–41. doi: 10.1300/J012v16n04_02

Carmines, E. G., and Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and Validity Assessment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cotton, A., Farley, M., and Baron, R. (2002). Attitudes toward prostitution and acceptance of rape myths. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 1790–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00259.x

Cullen, F. T., Link, B. G., and Polanzi, C. W. (1982). The seriousness of crime revisited: have attitudes toward white collar crime changed? Criminology 20, 83–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1982.tb00449.x

Dodge, M., Starr-Gimeno, D., and Williams, T. (2005). Puttin' on the sting: women police officers' perspectives on reverse prostitution assignments. Int. J. Police Sci. Manage. 7, 71–85.

Douglas, K. S., and Ogloff, J. R. P. (1997). Public opinion of statutory maximum sentences in the canadian criminal code: comparison of offenses against property and offenses against people. Can. J. Crim. 39, 433–458.

Evans, S. S., and Scott, J. E. (1984). The seriousness of crime cross-culturally: the impact of religiosity. Criminology 22, 39–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1984.tb00287.x

Farley, M., and Barkan, H. (1998). Prostitution, violence, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Women Health 27, 37–49. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n03_03

Farley, M., and Kelly, V. (2000). Prostitution: a critical review of the medical and social sciences literature. Women Crim. Justice 11, 29–64. doi: 10.1300/J012v11n04_04

Franklin, C., and Menaker, T. (2014). The impact of observer characteristics on blame assessments of prostituted female youth. Fem. Criminol. 10, 140–164. doi: 10.1177/1557085114535234

Gaines, L., and Kappeler, V. (2005). Policing in America, 5th Edn. Cincinnati, OH: Anderson Publishing.

Halter, S. (2010). Factors that influence police conceptualizations of girls involved in prostitution in six US cities: child sexual exploitation victims or delinquents? Child Maltreat. 15, 152–160. doi: 10.1177/1077559509355315

Jorgensen, C. (2014). Badges, Bongs, Bookies, and brothels: Police officers' Attitudes Toward Prostitution. Doctoral dissertation, ProQuest.

Kalant, H. (2010). Drug classification: science, politics, both or neither? Addiction 105, 1146–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02830.x

Kanazawa, S. (2010). Why liberals and atheists are more intelligent. Soc. Psychol. Q. 73, 33–57. doi: 10.1177/0190272510361602

Kennedy, M. A., Klein, C., Gorzalka, B. B., and Yuille, J. C. (2004). Attitude change following a diversion program for men who solicit sex. J. Offender Rehabil. 40, 41–60. doi: 10.1300/J076v40n01_03

Klockars, C. B., Haberfield, M., R., Ivkovich, S. K., and Uydess, A. (2001). “A minimum requirement for police corruption,” in Crime and Justice at the Millennium: Essays by and in Honor of Marvin E. Wolfgang,” eds R. A. Silverman, T. P. Thornberry, B. Cohen, and B. Krisberg (Norwell, MA: Kluwer), 185–207.

Lee, E. S., and Forthofer, R. N. (2006). Analyzing Complex Survey Data, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lucas, A. (2005). The work of sex work: elite prostitutes' vocational orientations and experiences. Dev. Behav. 26, 513–546. doi: 10.1080/01639620500218252

Petrocelli, M., Oberweis, T., Smith, M. R., and Petrocelli, J. (2014). Assessing police attitudes toward drugs and drug enforcement. Am. J. Crim. Justice 39, 22–40. doi: 10.1007/s12103-013-9200-z

Regoli, R. M., and Poole, E. D. (1979). Measurement of police cynicism: a factor scaling approach. J. Crim. Justice 7, 37–51. doi: 10.1016/0047-2352(79)90016-3

Sawyer, S., B., Rosser, R. S., and Schroeder, A. (1998). A brief psychoeducational program for men who patronize prostitutes. J. Offender Rehabil. 26, 111–125. doi: 10.1300/J076v26n03_06

Stylainou, S. (2002). Control attitudes toward drug use as a function of paternalistic and moralistic principles. J. Drug Issues 32, 119–152. doi: 10.1177/002204260203200106

Stylianou, S. (2003). Measuring crime seriousness perceptions: what have we learned and what else do we want to know? J. Crim. Justice 31, 37–56. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2352(02)00198-8

Stylianou, S. (2004). The role of religiosity in the opposition to drug use. Int. J. Offender Ther. Compar. Criminol. 48, 429–448. doi: 10.1177/0306624X03261253

Weitzer, R. (2005). New directions in research on prostitution. Crime Law Soc. Change 43, 211–235. doi: 10.1007/s10611-005-1735-6

Weitzer, R. (2007). Prostitution: facts and fictions. Contexts 6, 28–33. doi: 10.1525/ctx.2007.6.4.28

Wilson, G. P., Cullen, F. T., Latessa, E. J., and Wills, J. S. (1985). State intervention and victimless crimes: a study of police attitudes. J. Police Sci. Administr. 13, 22–29.

Wolfgang, M. E., Figlio, R. M., Tracy, P. E., and Singer, S. I. (1985). The National Survey of Crime Severity. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Justice.

Keywords: police, officer, attitudes, perceptions, prostitution

Citation: Jorgensen C (2018) Badges and Brothels: Police Officers' Attitudes Toward Prostitution. Front. Sociol. 3:16. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00016

Received: 27 September 2017; Accepted: 30 May 2018;

Published: 15 June 2018.

Edited by:

Alfonso Osorio, Universidad de Navarra, SpainReviewed by:

Georgios Papanicolaou, Teesside University, United KingdomCopyright © 2018 Jorgensen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cody Jorgensen, Y29keWpvcmdlbnNlbkBib2lzZXN0YXRlLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.