- Human Development and Family Science, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

Approximately half of all pregnancies are unintended. Many (58%) are carried to term, but a substantial proportion of unintended pregnancies are terminated. In this paper, we draw from qualitative interviews with 33 women who experienced an unintended pregnancy in an effort to examine the meanings women attributed to their pregnancies and to explore how narratives differ for women who chose to continue their pregnancies vs. those who opted for termination. Findings from grounded-theory analysis highlight the importance of cognitive appraisal, ability to navigate resources, availability of support, individual values and beliefs, and situational context in women's decisions to terminate or continue with an unintended pregnancy.

Introduction

Approximately half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, with a disproportionate number occurring among younger, unmarried, minority, less-educated, and lower-income women (Finer and Zolna, 2014). Unintended pregnancy includes both unwanted and mistimed pregnancies (Finer and Henshaw, 2006; Finer and Zolna, 2011); a mistimed pregnancy is not wanted at the current time but is desired at some future point, whereas an unwanted pregnancy is not wanted in the present or at any time in the future. Nearly 40% of unintended pregnancies end in induced abortion/termination (Finer and Zolna, 2014), but there are wide disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and income among those who opt for pregnancy termination (Jones and Kavanaugh, 2011).

While there has been considerable interest in attitudes toward abortion (e.g., Hans and Kimberly, 2014) and the outcomes of abortion, including women's psychological well-being (e.g., Charles et al., 2008) or socioeconomic status (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2007), there has been less investigation into the attitudinal and contextual factors that influence women's decision-making processes regarding abortion (Adamczyk, 2008). Yet, the decision about whether or not to terminate a pregnancy can be one of the most personal—and socially contested—decisions women make throughout their lives (Foster et al., 2012). Understanding the considerations in women's decisions to terminate vs. to continue their unintended pregnancies can provide guidance as to what women might need to ease the decision-making process (Kimport et al., 2011). Further, the few extant studies that investigated decision-making about abortion focused only on women who terminated their pregnancies (e.g., Kimport et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2012), suggesting the need for research that includes women who decided to terminate their pregnancies as well as those who decided to continue with unintended pregnancies.

Applying a symbolic interaction perspective (Blumer, 1969), our paper has two primary aims. First, we seek to understand how women construct their narratives, or make meaning of their unintended pregnancies. Further, we seek to understand how women make decisions about whether to terminate or continue an unintended pregnancy. Unintended pregnancy, a multidimensional construct, calls for research that goes beyond the numbers to explore thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and contextual influences of women with lived experience (Charon, 2004). Blumer (1969) argued that the meanings that individuals ascribe to their experiences (e.g., unintended pregnancy) are modified and interpreted through interactions with others and result in actions based upon these meanings. As such, this inquiry examines narrative interviews and utilizes women's own words and lived experiences to represent their stories. Narrative stories provide descriptive details of potential processes relevant in the decision making process that goes along with an unintended pregnancy, and they also speak to the unique stressors present for women who have experienced unintended pregnancy and the risk and protective mechanisms that led them to different decisions about terminating vs. continuing a pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Sixty-eight women living in an urban city in the South Central United States participated in a mixed-methods study on childbearing decisions. Women were recruited through flyers posted on a college campus and through social media and websites such as Craigslist. Oklahoma State University's Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was received before the study commenced. The sample for the current study includes the 33 women who experienced an unintended pregnancy. Of these women, 13 terminated their pregnancies, 20 continued their pregnancies, and among the latter group, three placed their infants for adoption. All but six women were mothers at the time of the interview. The sample was somewhat diverse, with 68% of the women reporting non-Hispanic white, 2% Hispanic, 12% American Indian, and 17% Black racial/ethnic identity. On average, women in the sample reported some college education and were 32 years of age at the time of the interview. The length of time since the unintended pregnancy varied between less than a year to nearly a decade, with the majority occurring between 2 and 5 years before the interview.

Data Collection

The study was carried out on a university campus in a private office within the second author's research laboratory. Participants were provided written and verbal information about the study, including their rights as a participant, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of the study. Once participants reviewed and signed consent forms, they participated in an audio-recorded semi-structured interview with one of two graduate research assistants. When there is more than one interviewer on a qualitative research team (QRT), it is important that they received the same standard training so that interviewing strategies are consistent, lending to more credible findings (Bergman and Coxon, 2005). Further, due to the sensitive nature of the research topic, the issue of participant risk and safety is of critical importance. The interviewers were students in the university's marriage and family therapy program, which includes specialized training in ethics and skills in observation, questioning, and responding techniques. Inclusion criteria were being over 18 years of age and able to speak and understand English. An interview guide was developed regarding experiences and decisions regarding pregnancy and childbearing. During the interviews, follow-up questions such as, “What do you mean?” or “Can you tell me more about that?” were asked for clarification. Interviewer reflexivity was also practiced during the interviews; for example, interviewers demonstrated reciprocity, a reflexive interview tool, by responding with empathy to participant responses that suggested difficult experiences (McNair et al., 2008). Following interviews, participants were asked to fill out a brief survey on their demographic characteristics and previously established measures on childbearing attitudes and behaviors from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) and National Survey of Fertility Barriers (NSFB). Participants were provided copies of the consent forms as well as a debriefing sheet that included local resources for mental and physical health in case the content of the interviews was distressing. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

We applied a grounded-theory methodology (Strauss and Corbin, 1998), which seeks to understand participants' thoughts, feelings, and experiences in order to comprehend their encounters with the world and explain a particular phenomenon (Glaser, 1998). Through use of the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), code was analyzed, and sections of data compared in pursuit of elucidating similarities and differences between narratives. As concepts and categories emerged from the data, they were continuously, simultaneously, and methodically compared to all other data in order to draw out themes. Due to the nature of the grounded theory methodology, instead of beginning with a hypothesis, data were first collected through narrative interviews. After data were collected, key points were extracted from the text and coded into concepts and then multiple categories, which were then used to generate theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Data analysis began with open coding (aka substantive coding), during which time data were examined line by line for content and meaning as concepts and categories began to become apparent. After open coding, axial coding was conducted, through which data were reintegrated in order to make meaningful connections between categories (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Selective coding was then utilized after a core variable was identified; this core variable was then used to guide further coding. Coding was conducted until no other themes emerged and data were seemingly saturated (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). A core variable was sought and identified to explain processes existing within the majority of narratives. Through the use of themes and quotes, a storyline was created to uncover an overarching theme that embodied the meanings women create surrounding either termination or continuation of an unintended pregnancy.

In presentation of the data, thick description was derived from women's narratives to portray an understanding of their experiences surrounding their unintended pregnancy. The presentation of data is one of the most unique and important aspects of qualitative research, and as such, extreme mindfulness was exercised to ensure interpretive validity. Ambert et al. (1995) stressed that, “the richness of quotes, the clarity of the examples and the depth of the illustrations in a qualitative study should seek to highlight the most salient features of the data” (p. 884). Therefore, direct quotations are integrated in an effort to drive home points, add depth to the analysis, and give personal meaning to the results (Creswell, 2009).

It is crucial to be aware of personal biases that can influence research design and analyses and to consider how both data gathering and interpretation of findings is qualified by this knowledge (Alvesson and Skoldberg, 2000). In an attempt to combat researcher partiality and preference, therefore, reflexivity and journaling were employed while reading personal narratives. As a way to safeguard interpretive validity, low inference descriptors were used and personal meaning and integrity of language was maintained. Further, in an attempt to ensure trustworthiness, established processes were followed to maintain credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Strauss and Corbin, 1998).

Credibility was sought using triangulation (Denzin, 1978), including data triangulation, methodological triangulation, investigator triangulation, and theory triangulation. Data triangulation and methodological triangulation were accomplished through the use of both the in-person qualitative interviews and the survey data to examine demographic and childbearing information. Investigator triangulation was achieved through use of two interviewers that collected data independently of the first author, who conducted the analysis. Theory triangulation was accomplished through use of grounded theory in combination with symbolic interactionism to explore thematic coding and meaning making.

Transferability was sought through use of a purposive sample of diverse women regarding childbearing experiences and behaviors. Whenever possible, women's demographic characteristics disclosed in survey responses were reported along with quotes from the women's narratives. This thick description serves to demonstrate other contexts, circumstances, and situations in which study findings may be applicable. Confirmability was sought through reflexivity and journaling of the researcher. An audit trail can be provided upon request that includes narrative packets with notes and highlighting of each step of the analysis.

Results

The analysis resulted in differential findings among two groups: those who terminated their unintended pregnancies and those who continued their unintended pregnancies. Both groups of women experienced unintended pregnancies, but their cognitive appraisals of the event and the way they made meaning of their experiences differed, as did contextual factors and personality/attitudinal characteristics for some women. Women in both groups described their unintended pregnancies as “mistimed,” rather than “unwanted,” but the way in which women who sought pregnancy termination made meaning of their experiences of unplanned pregnancy was different than those who continued their pregnancy.

Deciding to Terminate

Core Theme: Meeting Life Goals Before Baby

The women who opted for pregnancy termination felt unable to continue their pregnancies because they were lacking in one or more characteristics that they viewed as necessary to achieve before having a child. These included wanting to achieve significant life goals such as completing education and/or having an established career, suitable home, financial stability, and/or a committed and supportive partner. For many women in this group, being pregnant before achieving these life goals did not fit with the mental picture they had painted of how their lives should progress, and, as such, they sought an abortion to “get back on track” with their life plans. For example, one woman stated,

I plan on being married when I have children. I'd like to be finished with school—And I'd like to, um, already be in a job where I have opportunities for advancement and can grow with the company so I can feel comfortable financially. And, I haven't bought a home or anything like that. I just live in an apartment right now, so I'd like to have purchased a home (24-year-old Black, dating female).

Frequent concerns within this theme, beyond the desire for achieving goals such as education and career before baby, included contextual factors such as current unhealthy partnerships and financial instability that also influenced women's decisions to terminate. These contextual factors are reflected in two subthemes, “unhealthy partner relationships” and “fear of not being able to provide for the child.” For these women, postponing motherhood was not merely about waiting until certain life goals were met, but the decision to terminate was made to avoid bringing a child into an unhealthy or unstable situation.

Subtheme: Unhealthy Partner Relationship

Within the subtheme of “unhealthy partner relationship,” women described various situations in which their choice of partner or the status of their relationship with the father of their unborn fetus was inadequate or unsuitable for co-parenting. Reasons for inadequacy of partner or undesirability of relationship included, but were not limited to: date rape, intimate partner violence, alcoholism, criminal activity, having different life goals, lack of motivation of the father, relationship turbulence, and/or dissolution of the relationship/marriage. Approximately half of the narratives in this subtheme described men who were abusive, controlling, or who had substance abuse issues. For example, a woman who described her husband as a “very controlling alcoholic” with “raging behavior” stated, “I wanted kids, but not under that environment” (39-year-old Hispanic, married female). A 41-year-old White, married female with a “controlling, alcoholic husband” shared how her husband's actions swayed her toward termination of her pregnancy after his alcoholism resulted in a family car accident.

Women within this subtheme shared narratives including characteristics of partners and relationships that appeared considerably more dysfunctional than women who mentioned partners within the group who continued their pregnancies. Thus, adverse relationship dynamics, personality, and situational characteristics of the father appear to be important considerations in women's decisions to terminate an unintended pregnancy.

Subtheme: Fear of Not Being Able to Provide for the Child

Narratives reflecting this subtheme among women who terminated their pregnancies focus on worries that they would be unable financially and/or emotionally provide for a child. As one woman explained,

I really thought about it long and hard and it was a really hard decision to make. But, I had seen so many kids who are disadvantaged and you see so many families struggling because they can't afford these kids. So, at that time, I thought I don't want to have a kid that is unwanted. I don't want to have a kid we can't afford. I don't want to be struggling and stressed out. I thought that would affect that child if everybody around it is stressed out. You look around and see all these unwanted kids. I thought—no, no. So, that is why I had the abortion. I thought, I am just not going to have that child (37-year-old White, married female).

Therefore, the core theme in the decision process among women who opted to terminate their unintended pregnancies is that these women did not feel ready and/or able to provide care for a(nother) child; they reported feeling that they first needed to accomplish one or more major life goals such as a completed education, an established career, a suitable home, financial stability, and/or a committed and supportive partner. Some women not only lacked what they considered a necessary situation for childrearing, but they also reported barriers that they felt would prevent them from having a healthy or stable family situation in which to raise a child. Several women in this group disclosed having been raped and felt they could not, for their own health and well-being, continue their pregnancies. There were also women who noted being in a relationship with an abusive partner or an addict, which they explained made the environment unsuitable for childrearing. Further concerns were expressed in this group regarding the ability to provide for a child financially or care for a child's needs physically and/or emotionally.

Deciding to Continue the Pregnancy

The majority of women who decided to continue their unintended pregnancies disclosed having a strong maternal identity and confidence about their abilities to succeed in life despite an unexpected pregnancy. Around half of the women who decided to give birth following an unintended pregnancy did so within the context of a stable relationship or marriage, which was in stark contrast to most women who opted for termination. Similar to the termination group, the majority of women who continued their pregnancies expressed wishing they had more ideal circumstances before having a baby, but these women expressed greater confidence in their abilities to overcome challenges and/or that they had access to more resources such as partner support.

Core Theme: Overcoming Obstacles as a Mother

The overarching theme in the narratives of women who decided to continue their pregnancies was that although their life circumstances may not be ideal, they would be able to overcome the challenges that they knew would come with the child's birth. One such woman described her feelings about an unintended pregnancy as, “scared and worried-but never once thought about an abortion. I just buckled down, got myself together to take care of it” (24-year-old Black, married female). Maternal identity and importance of motherhood were strong themes in these narratives as well. For example, one woman described her children as “filling voids” and motherhood as a paramount experience in her life. She stated, “It's the only thing that has given my life purpose, um, and there are days that it is the only thing that gets me out of bed” (40-year-old White, divorced female). Another shared, “Definitely was a pleasant surprise. I believe every child is meant to be, so I didn't have any qualms about having her” (28-year-old White, never-married female).

For women in this group, although their pregnancies were unintended, they described them as favorable, yet mistimed. These women described narratives of overcoming obstacles as mothers and making the best of, often times, tough situations. The majority of the women within this theme also reported a love for children, experience with children, and/or a strong maternal instinct or desire to mother.

Subtheme: Unintended Within a Stable Relationship

Around half of the women who continued their unintended pregnancies did so within the context of a stable relationship or marriage. One such woman shared, “My son is 6; he was not planned, but we had been married for a year, so it was fine” (28-year-old White, married female). When asked about life circumstances, she shared, “I would have finished school first. I definitely say that. And, it is not that I would trade him for the world. But, if I could have everything I have now and just have done it differently, I would have. I would have waited until I was finished with school and we were married longer, cause it was really hard.”

Within the narratives, getting pregnant was sometimes seen as a catalyst for entering into marriage if the partner relationship was favorable. One woman, for example, explained,

Well, we hadn't been dating that long, and I have been through enough bad relationships, unhealthy relationships that I knew right away that with him I could marry him and be happy…I found out about her and I told him, and we, we decided we are going to have this baby…we talked about it and we figured it out that, you know, we're really happy and we know we can make each other happy, so we just went to [church name] and we got married. I was four months pregnant (21-year-old American Indian, married female).

Subtheme: Adoption

Of the 20 women who decided to continue their unintended pregnancies, three women opted to place their infants for adoption. These women had similar contextual factors as the women who opted to terminate their pregnancies and noted feeling that though they were unable to care for a child at the time, they did not consider abortion. These women also described unfit partners and/or fear of being able to provide for the child. In contrast to the women who opted for pregnancy termination, women who selected adoption disclosed strong emotional connections with their baby and/or described strong maternal identities. Each one spoke of wanting to “keep the baby,” but that selecting adoption was in the child's best interest, despite the emotional difficulties it caused them. For example, one woman stated,

You know, I lived at home, I had never… I had just started college, I had never lived on my own. There were so many things that I knew if I had a kid those things later in life that I thought I'd always accomplish, wouldn't get done. I knew I couldn't provide for the child. I thought, I don't want my mom raising my kid. So just, I guess, being completely focused on what was best for all the parties involved helped make that decision (33-year-old White, married female).

When asked about when they made the decision to give the baby up for adoption, answers differed. One woman stated she knew from the “very beginning” that this baby was not hers to keep and she set her mind to that fact early on. She shared,

When I was pregnant and dealing with all the stuff, you know, going to doctor's appointments and the baby moving, and the heartbeat, and stuff, I constantly had that mindset that this baby wasn't mine, this was their baby, and I'm carrying this baby for them, so I think mentally I really prepared myself to known that that's the best decision for both of us (33-year-old White, married female).

In contrast, the other two women who placed children for adoption shared not knowing until around half-way into the pregnancy that adoption was the best choice for them, and even then, they both mentioned having conflicting feelings and changing their minds back and forth. When asked if she knew from the beginning that she was going to choose adoption stated, one woman stated, “No, I made the decision probably about halfway through. You know, you struggle within yourself as to what to do because there are many options out there, but for me and my religion, that (adoption) was the best choice” (35-year-old White, married female).

When asked if she was always certain about the plan for adoption, another woman stated, “I did flip flop a lot, but I knew that for her safety this was the most important thing for her, for her safety and all this” (24-year-old White, dating female).

Women shared feeling a sense of loss and sadness regarding the adoption process. One woman when asked about her feelings right after the adoption disclosed immense sadness, stating she felt, “lots and lots of pain and sadness. You know in your heart it's the right decision, but it's still hard. Or I should say, your brain… your brain knows it's the right decision, but your heart is telling you totally different” (35-year-old White, married female).

Another mother shared equal feelings of sadness and felt she needed to put safeguards in place to stop herself from changing her mind, as she felt strongly she would if it were easy to do so. As such, she selected an out of state adoption to ensure a secure barrier to stop her from trying to get her daughter back. She confessed, “I wanted as far as possible away from me ever changing my mind. Like for me, I'm the kind of person who did want a family and it would be too easy for me to change my mind if she was closer” (24-year-old White, dating female).

Therefore, there were several similarities within personal narratives regarding self-disclosed personality characteristics and situational context within the group of women who opted to continue their unintended pregnancies. As a group, these women described strong maternal identities, a desire for children at some point in time, experience with and/or a value for children, the ability to overcome obstacles as a mother, and/or a strong will to succeed in life and meet goals despite an unexpected pregnancy. Around half of the women in this group continued their unintended pregnancies in the context of a stable relationship or marriage, which was in contrast to the majority of women who opted for termination of their unintended pregnancies. Women who continued their pregnancies described making their situations work to the best of their abilities, despite being aware that it might have been easier if the pregnancy had been planned at a later time. Thus in both groups, women expressed similar desires for life circumstances and wishing their pregnancies had occurred after achieving stated life goals, but differences emerged in their appraisals of how or whether they would overcome obstacles and what supports and resources would be available to them. None of the women who continued their pregnancies expressed regret regarding their decisions, and each woman in this group expressed positive attitudes toward motherhood.

Grounded Theory Generation

Social-Cognitive Model of Birth Decision Making

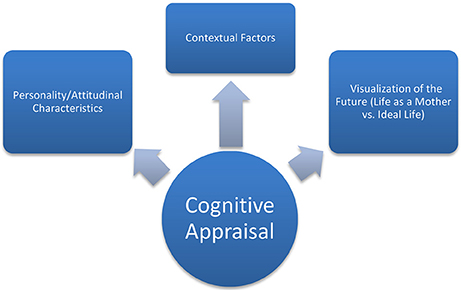

We explored narratives within the emergent data to the point of saturation of possible categories in an effort to uncover a theory within the women's stories of unintended pregnancy and the decision making process leading to termination of a pregnancy vs. motherhood. The theory generated describes the path leading to women's decisions about their pregnancies. When confronted with an unintended pregnancy, women make decisions of how to proceed with their lives and whether to continue with their pregnancies or seek pregnancy termination based on cognitive appraisal of one or more of the following: situational context, including access to resources, availability of support, financial situation, the partner they are pregnant by, housing, education, etc.; personality/attitudinal characteristics, including tendency toward pessimism vs. optimism, life goals, values, beliefs, etc.; as well as visualization of the future; including ability to visualize a maternal identity and/or ability to navigate life with a child vs. one's imagined “ideal life.” Figure 1 presents a visual depiction of the theoretical model revealed through grounded theory analysis.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of how women make decisions in regard to whether to terminate or continue an unintended pregnancy.

Discussion

The aim of this inquiry was to explore the personal narratives of women who had experienced at least one unintended pregnancy and were faced with often tough decisions of whether to continue or terminate their unintended pregnancies, and among those opting to continue their pregnancies, with the additional decision of whether or not to place the infants for adoption. Through use of personal narratives, women elaborated on situational dynamics and provided context as to their ultimate decisions.

Although all women in the sample experienced unintended pregnancies, the way they perceived and cognitively appraised the event differed based on contextual, situational, and personal characteristics. In this study, all participants—regardless of pregnancy termination decision—reported wanting at some point to become mothers, thus indicating their unintended pregnancies were “mistimed.” This was the overarching theme of the paper and was reflected in every participant's narrative. Women who opted for pregnancy termination felt unable to continue their pregnancy due to particular circumstances they believed were necessary before they could have a baby, such as wanting to complete their education or having an established career, suitable home, financial stability, and/or a committed and supportive partner. A subset of women noted additional barriers to bringing a child into the world that they felt would prevent them from having a stable or healthy situation in which to raise the child, including partners who were abusive, had substance abuse issues, engaged in criminal activity, or a pregnancy that had resulted from rape. Many of the women who opted for termination felt they made the decision in the best interest of the future child, as well as themselves, by terminating a pregnancy that in their current context would have potentially caused hardship on that child or on other children already present within the family. Women in the termination group also described scenarios of less support and/or resources than women who opted to continue their unintended pregnancies.

Some women in this study who opted to terminate expressed feelings of guilt, trouble coping with the event, feelings of secrecy or of not being able to share about the experience, and then feeling either a sense of relief about the decision to terminate or wondering what life would be like if they had chosen differently. Similarly, a narrative study by Gray (2015) found that women who opted for termination expressed feelings of guilt, mental side effects, feelings of secrecy, unsupportive friends/family, and feeling like a “bad person,” and wondering what life would have been like if the pregnancy had not been terminated. Although women reported they had trouble dealing with their decision, they did not report feelings of regret about termination but rather some difficulty coping afterwards (Gray, 2015). This sentiment was shared in two termination narratives in the present study and suggests future research and practice should consider regret and difficulty coping as independent constructs. Throughout termination narratives, women often went to great lengths to describe their reasoning, which included personal and contextual factors, in an attempt to justify or take ownership of the decision process and resulting pregnancy termination. This “decisional autonomy” is associated with more favorable post-abortion outcomes for women (Lie et al., 2008; Kimport et al., 2011).

The majority of women who opted to continue their unintended pregnancies described having a strong maternal identity, desire for children, felt ability to overcome obstacles as a mother, and a strong belief that success in life goals would occur regardless of pregnancy. In stark contrast to women in the termination group, approximately half of the women who continued their pregnancies reported being in a stable relationship or marriage. Much like those in the termination group, these women shared wishing they had more ideal circumstances for childbearing, but described making the situation work to the best of their ability while still acknowledging that a planned pregnancy at a later date would have been preferred. While both groups acknowledged challenges when faced with unintended pregnancies, there was a notable difference in women's appraisal of how they would handle the situation and what support and resources would be available to them. Overwhelmingly, women who opted to continue their pregnancies more positively appraised their situation and were confident in their abilities to obtain the resources and support necessary despite potential challenges and lack of ideal circumstances. Three mothers who continued their pregnancies felt their life circumstances were unsuitable for rearing a child and decided to place their infants for adoption, despite all three expressing that they wished they had been able to raise the children.

While there was a mixture of feelings present within women who opted to terminate, all women who continued their pregnancies expressed no regret regarding their decision and typically noted favorable characteristics about motherhood. They described financial hardships and difficulties finishing school, yet also spoke of the joys of motherhood. Many highlighted their self-efficacy as mothers and a high value of motherhood.

The findings from this study therefore suggest the importance of cognitive appraisal, ability to navigate resources, availability of support, individual values and beliefs, personality characteristics, attitudinal characteristics, and situational context in women's decisions to terminate or continue with an unintended pregnancy.

There are limitations to the current study; due to the purposive sample of women recruited near a major university, findings cannot be extrapolated to the general population. In addition, the topic may have been of particular interest to women based on their reproductive experiences. Women may have self-selected themselves into the study if they experienced particularly strong reactions, positive or negative, in the experience of their unintended pregnancies. Additionally, women were asked to reflect back on retrospective pregnancy intentions and decision-making. Their attitudes or feelings may have changed over time, or their current life circumstances may affect their perceptions of decision-making and outcomes of the decision. Further, there was a range in the length of time since the unintended pregnancy, with some occurring more recently than others, which may impact women's narratives. However, this was the case for both groups (those who continued their unintended pregnancies and those who terminated them).

Despite the limitations, the findings reveal important insights into women's decision-making processes and considerations following unintended pregnancy. Through exploration of personal narratives of women who had encountered an unintended pregnancy, we have new insights into the ways that cognitive appraisal of contextual factors, personality/attitudinal considerations, and visions of the future intersect to impact decision making about termination of an unintended pregnancy or continuing the pregnancy and mothering vs. placing for adoption. Because unintended pregnancies are associated with increased risk of psychological stress, postpartum depression, lower educational attainment, and financial hardship (Cheng et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2011; Abbasi et al., 2013), understanding factors in the decision-making process including barriers and resources is important for maternal and child health and well-being outcomes. Further, there may be policy implications as well, which could help address economic barriers reported by some participants who opted to terminate because of concerns about not being able to provide for a child.

The difficulties noted in the lived experiences of women's narratives within the current study should be useful for practitioners who counsel women on pregnancy options and decision-making and following the decision to continue or terminate pregnancies. These narratives are not only useful in offering knowledge and insight into the cognitive appraisal of contextual factors, personality/attitudinal characteristics, and visualization of an ideal future vs. life as a mother, but they also highlight processes that may reduce stress and result in more positive mental health outcomes during the process and thereafter. Understanding that various contextual and individual characteristics influence the decision making process suggests that practitioners should actively seek women's preferences in order to provide appropriate counseling regarding unintended pregnancies or contraception more broadly. Following termination, practitioners who can assist women with cognitive reappraisal of decision making to address feelings regarding the termination can help create a sense of decisional control and autonomy.

Regardless of women's decisions following unintended pregnancies, our narrative findings highlight that the decision making process following unintended pregnancy can be difficult. Aligned with the symbolic interaction perspective, our results indicate that the availability of support from professionals, family members, and/or friends that aids women in their decision making process and following birth or pregnancy termination is critical.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board. The protocol was approved by the Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

TS performed the qualitative analysis of data, developed the grounded theory, and wrote much of the manuscript including the results and discussion sections. KS collected the data, wrote the materials and methods section, and contributed to the introduction and literature review sections.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM109097; Jennifer Hays-Grudo, PI) and the College of Human Sciences at Oklahoma State University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2016 Annual Conference of the National Council on Family Relations in Minneapolis, MN.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abbasi, S., Chuang, C. H., Dagher, R., Zhu, J., and Kjerulff, K. (2013). Unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression among first-time mothers. J. Womens Health 22, 412–416. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3926

Adamczyk, A. (2008). The effects of religious contextual norms, structural constraints, and personal religiosity on abortion decisions. Soc. Sci. Res. 37, 657–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.09.003

Alvesson, M., and Skoldberg, K. (2000). Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Ambert, A., Adler, P. A., Adler, P., and Detzner, D. F. (1995). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. J. Marriage Fam. 57, 879–893. doi: 10.2307/353409

Bergman, M. M., and Coxon, A. P. M. (2005). The quality in qualitative methods. Qual. Soc. Res. 6:34. doi: 10.17169/fqs-6.2.457

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic Interactionism; Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Charles, V. E., Polis, C. B., Sridhara, S. K., and Blum, R. W. (2008). Abortion and long-term mental health outcomes: a systematic review of the evidence. Contraception 78, 436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.005

Charon, J. M. (2004). Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cheng, D., Schwarz, E. B., Douglas, E., and Horon, I. (2009). Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception 79, 194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Methods Approaches, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., and Horwood, L. J. (2007). Abortion among young women and subsequent life outcomes. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 39, 6–12. doi: 10.1363/3900607

Finer, L. B., and Henshaw, S. K. (2006). Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 38, 90–96. doi: 10.1363/3809006

Finer, L. B., and Zolna, M. R. (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 84, 478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013

Finer, L. B., and Zolna, M. R. (2014). Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in theUnited States, 2001-2008. Am. J. Public Health 104, S43–S48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416

Foster, D. G., Gould, H., Taylor, J., and Weitz, T. A. (2012). Attitudes and decision making among women seeking abortions at one US clinic. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 44, 117–124. doi: 10.1363/4411712

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Gray, J. B. (2015). “It has been a long journey from first knowing”: narratives of unplanned pregnancy. J. Health Commun. 20, 736–742. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018579

Hans, J. D., and Kimberly, C. (2014). Abortion attitudes in context: a multidimensional vignette approach. Soc. Sci. Res. 48, 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.06.001

Jones, R. K., and Kavanaugh, M. L. (2011). Changes in abortion rates between 2000 and 2008 and lifetime incidence of abortion. Obstet. Gynecol. 117, 1358–1366. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c405e

Kimport, K., Foster, K., and Weitz, T. A. (2011). Social sources of women's emotional difficulty after abortion: Lessons from women's abortion narratives. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 43, 103–109. doi: 10.1363/4310311

Lie, M. L., Robson, S. C., and May, C. R. (2008). Experiences of abortion: a narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 8:150. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-150

McNair, R., Taft, A., and Hegarty, K. (2008). Using reflexivity to enhance in-depth interviewing skills for the clinician researcher. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-73

Shah, P. S., Balkhair, T., Ohlsson, A., Beyere, J., Scott, F., and Frick, C. (2011). Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Mater. Child Health J. 15, 205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0546-2

Keywords: unintended, pregnancy, decision-making, grounded theory, qualitative, motherhood, abortion

Citation: Spierling T and Shreffler KM (2018) Tough Decisions: Exploring Women's Decisions Following Unintended Pregnancies. Front. Sociol. 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00011

Received: 09 February 2018; Accepted: 04 May 2018;

Published: 30 May 2018.

Edited by:

Kath Woodward, The Open University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sophie Rose Woodward, University of Manchester, United KingdomDawn Sarah Jones, Glyndwr University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2018 Spierling and Shreffler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karina M. Shreffler, a2FyaW5hLnNocmVmZmxlckBva3N0YXRlLmVkdQ==

Tiffany Spierling

Tiffany Spierling Karina M. Shreffler

Karina M. Shreffler