- 1Department of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands

- 2Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, Philipps University Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 3CEDLA Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 4Department of Social Sciences, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Peru

- 5Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador

In several cities and regions in Spain there has been a fight against privatization of water supply in the past decade. Some cities have decided to re-municipalise water supply and debates about implementing the human right to water and sanitation have been held in many parts of Spain, following the success of the Right2Water European Citizens' Initiative. This paper examines how the European “Right2Water” movement influenced struggles for access to and control over water in Spain from a political ecology perspective. It explores how “Right2Water” fuelled the debate on privatization and remunicipalization of water services and what heritage it has left in Spain. We unfold relationships with and between water movements in Spain—like the Red Agua Publica—and relationships with other networks—like the indignados movement and subsequently how water protests converged with austerity protests. In different places these struggles took different shapes. By deploying five case studies (Madrid, Valladolid, Terrassa, Barcelona, and Andalucía), we look at how the human right to water and sanitation framework served as a tool for social and water justice movements. Struggles for water justice in Spain are ongoing and we seek to identify the temporarily outcomes of these struggles, and whether power balances in Spain's water services provision have shifted in the past decade.

1. Introduction

In the past decade the struggle for water and sanitation justice has been linked with alliances deploying informal strategies and campaigns for formal recognition of the human right to water and sanitation (see, e.g., Bakker, 2007; Sultana and Loftus, 2011, 2020; Clark, 2019; Bieler, 2021). The focus of this paper is on the struggle, discourses, and politics in Spain, departing from the European Citizens' Initiative “Right2Water” and examining links and similarities between the European Right2Water movement and Spanish water movement(s).

The European Citizens' Initiative (ECI) “Right2Water” ran and collected 1.9 million signatures across Europe in 2012–2013, uniting cities, villages and civil society organizations against water privatization (Moore, 2018; Van den Berge et al., 2018, 2021; Bieler, 2021). With that result it became the first successful ECI, simultaneously building a Europe-wide movement and putting the water issue high on the European political agenda. “Right2Water” proposed to implement the human right to water and sanitation in European legislation, as a strategic-political tool to fight privatization of public water utilities (Fattori, 2013; Van den Berge et al., 2020; Bieler, 2021).

Implementing such water justice notion is part of an ongoing socio-political struggle. This struggle had been going on in Spain before the start of the ECI and it has continued afterwards. Deploying a political ecology lens, this paper examines how “Right2Water” influenced and impacted ongoing struggles for access to and control over water in Spain; how it fuelled the debate on (de-)privatization of water services and what heritage it has left in Spain. Moreover, it looks at how social movements developed, reinforced or complemented each other in their struggles for social justice and against austerity measures that have marked the second decade of this century. Rise of the “Indignados” (Occupy) movement coincided with the rise of a water movement like the Red Agua Publica (e.g., Hughes, 2011; Babiano-Amelibia, 2015; Hernández-Mora and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2015; Castro, 2018). In the past decade a growing number of cities and regions have decided to re-municipalize water supply. The human right to water and sanitation framework was instrumental in this process, as we will show in a few cases. The Right2Water movement changed water policy discourse in Europe (Van den Berge et al., 2020) and proved to be a support to the Spanish water movement, that continues to fight for a more participatory and democratic water governance and policy. In Section 2 we describe our research framework and methodology. In Section 3 we will look at the history of water policy and privatization in Spain. In Section 4 we will look at the rise of social movements and in Section 5 we will highlight a few cases of water struggles in Spain. In Section 6 we examine the stakes and stakeholders that, for the time being, have won and lost in these struggles, and the overall outcomes of the water policy and politics battles over the past decade. We draw our conclusions in Section 7.

2. Conceptual framework and research methodology

The conceptual base of this research is political ecology, which is a political approach toward the study of natural resources management. Ecological problems are seen as deeply interwoven with and produced by the socio-political and economic context (Bakker, 2003; Robbins, 2004). This paper will analyse historical and political processes of water management in Spain, looking for underlying power relations (Forsyth, 2003; Perreault et al., 2015). Directly connected to this, the notions of environmental justice and contestations/non-contestations are central. In academic and activist debates, environmental (and water) justice is defined in multiple ways—for instance, by integrating and balancing or contrasting the arenas of distributive justice, cultural justice, representational justice and socio-ecological justice, for human and non-human communities and agents (Schlosberg, 2013; Zwarteveen and Boelens, 2014; for an overview, see e.g., Boelens et al., 2018, 2022; Coolsaet, 2020). In this research, we concentrate on three of its conceptual dimensions: recognition, redistribution, and representation (Fraser, 2000; Fraser et al., 2004; Schlosberg, 2004). We focus therefore not just on the distribution of access to water, but also about who participates in political decision-making processes and whose values and interests are recognized by, for example, social norms, languages, and institutions (Fraser, 2000). With regards to public water services this means that citizens must be recognized as political actors and therefore co-decide and co-govern in water services management. All dimensions are distinct but interlinked and overlapping (Schlosberg, 2004).

Hydro-technological modernization processes and legal-institutional policy reforms coalescing in diverse forms of neoliberal water governance provide the background to these last decades' powerful trends toward Europe's water governance model (e.g., Swyngedouw, 2005, 2013; Bakker, 2010; Vos and Boelens, 2018). Understanding neoliberal water governance conceptualization is key. In brief, neoliberal thinkers and policy-makers advocate treating water as an economic good. Water resources' service and/or property, therefore, need to be private, transferable, and priced—commodified. According to neoliberal logic, policy measures such as privatizing water service provision, granting concessions to operate distribution networks, and implementing full-cost recovery in water service pricing would lead to improved water service, and more efficient operation and maintenance. In water governance, the assumption is that such neoliberal incentives lead to efficient water use (Swyngedouw, 2005; Bakker, 2013; Boelens et al., 2018). In practice, however, many studies have shown that privatizing public utilities has often failed to benefit water users. Rather, tariffs hiked, investments in infrastructure lagged behind, quality of service provision did not improve, and the environment was jeopardized (Bakker, 2010; Pigeon et al., 2012; Lobina, 2014; Ioris, 2016; Van den Berge et al., 2018). In recent years, protests have been organized in various parts of Europe by citizens and civil society organizations to stop privatization of drinking water utilities or demand cancelation of these contracts, challenging the neoliberal governance structure and calling for a vision on water as a common (Ostrom, 1990; Bakker, 2007).

Finally, water justice movements address injustices both at the individual, community and supralocal levels (see e.g., Schlosberg, 2013; Shah et al., 2019; Dupuits et al., 2020; Boelens et al., 2022). This is the case for Right2Water as well. Water (in)justices involve both quantities and qualities of water, as well as access to and distribution of water privileges and forms of control over water (e.g., Sultana and Loftus, 2011; Crow et al., 2014; Dupuits, 2019). This entails also that water conflicts include questions about decision making, authority and legitimacy. These are intimately linked to the struggle over discourses, favoring particular water governance notions and policies while obliterating others—in terms of thinking about and acting upon “water” (cf. Forsyth, 2003; Zwarteveen and Boelens, 2014; Roth et al., 2015). As discourses sprout from, substantiate, and actively constitute policy arenas, they become a necessary part of the struggle of social movements: discourse change is not only a trigger for social mobilization and protest but also a precondition for policy change (Feindt and Oels, 2005). Media attention, which is one of this paper's fields of scrutiny, is an indicator for the domination of particular discourses in a specific period of time, and it also reflects how governance processes and social movements are framed, while it indicates resonance or influence in society (Benford and Snow, 2000).

The main research question that we seek to answer is how the European Right2Water movement has related to the Spanish water movement and how the human right to water and sanitation (HRTWS) has been instrumental in their struggles against privatization of water services. Literature and archival research and activist debates in the Spanish institutional and movements' landscape, have been the main sources of information on human rights to water, privatization and re-municipalization of water services in Spain, and how social movements have campaigned for public water provision. Five cases are analyzed as examples of local struggles with diverse settings and histories of privatization and movements. The cases show different types of water governance and ways of activism and provide lessons for future debates over water services provision, governance and remunicipalization. Besides the cases, data collection was done for this study on drinking water service privatization, re-municipalization of water services in Spain and on debates around these issues and the human right to water in Spanish newspapers. We explored these issues and social movements more in depth by applying bibliometric methods and data mining. With text mining software (Lexis Uni® for newspapers) we searched and analyzed the number of times that these issues and movements were mentioned in Spanish national newspapers and how this developed during the past decade between 2010 and 2022. We searched for unique articles on key words “human right to water” (“Derecho Humano al Agua, DHA”), “15-M, “ECI Right2Water” and “Marea Azul” in combination with “water services.” Besides this we searched for “New Water Culture,” “privatization,” and “remunicipalization” also in combination with “water services.” Thirdly we checked mentions of two social organizations that played an important role in water debates: “AEOPAS” and “FNCA” also in combination with water services provision. We visualized trends in media attention in two graphs. Given that we consider newspapers as relevant media that reflect public debates and public issues of interests in Spain, we looked at the number of unique articles that dealt with these issues. With this media analysis we expected to show if, and how, social movements have gained influence and attained to change discourse in the Spanish newspapers with regards to water services management.

3. History of water services provision in Spain

3.1. Water policies, privatization, and rise of the New Water Culture

Water management in the twentieth century in Spain was characterized by a hydraulic paradigm stemming from the Franco regime that aimed to “develop” Spain through water infrastructure imposed upon the population and based on use of water resources to maximize State economic benefit (Camprubí, 2013). In 2001 the Spanish government introduced the National Hydrologic Plan (NHP) and proposed construction of over 100 dams with a similar view on water as an economic good (Lopez-Gunn, 2009). The NHP puts emphasis on technology to regulate rivers (nature) and use of water where it is the most profitable, fitting tightly to the ideology of Franco's regime (Hernández-Mora et al., 2015; Swyngedouw, 2015; Swyngedouw and Boelens, 2018). The plan was adopted after massive protests throughout Spain, and modification by the Spanish parliament in 2005 as Act 10/2001 on the National Hydrological Plan (Ministerio para la transicion ecologica y el reto demografico, 2001, 2005). Since the 1990's, there has been a trend in Spanish municipalities to privatize water services, mainly through public-private partnerships (PPP; Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015; García-Mollá et al., 2020). This term is frequently used by multinational corporations to disguise a privatization through contractual arrangement, often a long-term concession. The Spanish privatization model of (mostly urban but also rural small-village) water services over the last three decades is often described as “mercantilizacion” (Bakker, 2010; Hernández-Mora and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2015). While being a natural monopoly, this marketization of water services tends to favor the interests of powerful groups (corporations) at the expense of the public interest and the commons, as it is characterized by the absence of competition (Gonzalez-Gomez et al., 2014; Heller, 2020).

In the last decade of the twentieth century and beginning of the twenty-first century the EU saw a wave of utility privatization (Hall and Lobina, 2005; Hall et al., 2011). Spain was no exception to this phenomenon. Private companies in the water industry increased their share in provision of water services to the population from 37% in 1996 to 48% in 2006 to 55% in 2015 (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015) by focusing on water supply in urban areas because that can generate most profits in a “market” with many “customers” in a small area. Local governments often saw privatization as an easy way to increase their income at short term because of the concession bonus and by keeping water supply off their balance sheets (Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015; Bel, 2020). This gave rise to an intense debate about the desirability of this privatization of urban water services with a clear oligopolistic dominant position for multinational companies (Gonzalez-Gomez et al., 2014; McDonald and Swyngedouw, 2019). Political decisions were substituted by market instruments that favored corporations because of the structural imbalance between these (powerful) players and (powerless) municipalities (Hernández-Mora and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2015; Heller, 2020).

Simultaneously, since the 1990's, a coalition of academics, social activists, and water managers in Spain and Portugal has been promoting a shift from the hydraulic paradigm and seeing water as an economic good (Martínez-Fernández et al., 2020). This New Water Culture placed the emphasis on ecosystem protection and ecological health as a means to guarantee the availability of sufficient good-quality water to sustainably meet needs. In 2000 the Water Framework Directive (WFD) came into force in the EU (European Commission, 2000). This European law needed to be transposed into Spanish law and water activists saw this as an opportunity to shift the priorities of the traditional economic-minded water management system to a more holistic approach that recognizes ethical, socio-political, and environmental concerns (Castela-Lopes, 2021). The New Water Culture movement was founded in opposition to dam building and the inter-basin transfer of water from the Ebro River. It emphasized participatory and transparent decision-making in water management and provided an alternative policy framework as it positioned water as a common and a human right. The movement coalesced in the New Water Culture Foundation (Fundación Nueva Cultura del Agua) or FNCA (Martínez-Fernández et al., 2020). One of the founders was Pedro Arrojo, former professor at Zaragoza University and now the UN special rapporteur on the human right to water and sanitation, who explained it as follows: “Water services as services of general interest of society go beyond the logic of the market” (…). “For this reason, faced with the privatizing policies of neoliberalism that transform these public services into simple businesses, we must face the challenge of building new models of public and participatory management, based on principles of sustainability, justice, transparency and citizen participation” (Arrojo-Agudo, 2017a, p. 47).

The economic crisis of 2008 generated an increase in situations of social vulnerability and problems related with affordability and accessibility to water in urban contexts (Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020). Privatization processes of water services coincided with austerity measures that European institutions promoted in the countries most affected by the economic crisis (Zacune, 2013; Bieler and Jordan, 2017). European austerity policies aimed to reduce government budget deficits through cuts in public services, which usually include water services, and decrease government spending. These savings on government costs came at the expense of providing vital services to citizens (Castela-Lopes, 2021). The European Commission imposed privatization of water services as one of the conditions of bailouts to crisis-hit countries Greece and Portugal [Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), 2012; Zacune, 2013; Kishimoto and Hoedeman, 2015; Bieler and Jordan, 2017] and also in Spain the pressure of European austerity measures was high (Center for Economic Social Rights, 2012). In 2011 the European Commission made a new attempt to further liberalize the services sectors in Europe by means of a proposal for a “Concession Directive.” This directive aimed to align concessions contracts with economic water operators and single market rules (European Commission, 2011; Tosun and Triebskorn, 2020). The directive promoted to open municipal water services for EU-wide bidding and aimed to create a European water services market which would open the door to privatization (Van den Berge et al., 2020). This was conceived by water activists as a “privatization through the back door” (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2013) and in Spain the directive was therefore called the “Privatization Directive” (Limon, 2013a). The Right2Water movements discontent with Europe's water policy and governance was exactly with this proposed directive and earlier attempts to apply internal market rules to water supply and the management of water resources, because it would mean the commodification of water (Castela-Lopes, 2021; Van den Berge et al., 2021).

3.2. Privatization of water services in Spain

In Spain, the process of privatization was instigated by the search for funding by municipalities in crisis. It happened mostly through concessioning as the perverse mechanism of the “concession fee” allowed for a rapid injection of money into the municipal treasury, but the backside of this coin was a decades-long privatization and loss of control over the service (Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015; Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020). This process was supported by European Commission liberalization policies. Transformation of a public-service ethos to a profit-serving ethos, combined with technocratic and “neutral” solutions to complex societal and political problems and commodification of natural resources (to the extent that everything has a tradeable price), are part of the neoliberal project of completion of the European Single Market (Moore, 2018).

Privatization occurred by two major corporations: Aguas de Barcelona (Agbar, subsidiary of Suez Environment) and Aqualia (part of the FCC: Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas group), both multinational enterprises (Hall and Lobina, 2012; Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015). These two companies account for almost 90% of the total private water supply (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015). This privatization and the oligopolistic character led to an over emphasis on profit margins and resulted in environmental degradation by failing to comply with the environmental terms and conditions in contracts (Kishimoto et al., 2014) as market logics do not value or protect human rights, nor sustainability of ecosystems (Arrojo-Agudo, 2017a; Heller, 2020).

The natural monopoly that is inherent to water supply; the power imbalance between municipalities and multinational private providers and the drive for profit maximization form a hazard to the fulfillment of the human right to water and sanitation in case of privatization (Heller, 2020). In the Spanish model of privatizing urban water management all these risks became visible and reality. Costs were born by the citizen while private companies took benefit from water resource exploitation by setting, on average, higher prices than public companies. The privatization process in Spain was often accompanied by increasing rates, sometimes up to over 60% (García-Rubio et al., 2015). Local authorities lost control over the service and access to water provision was jeopardized for vulnerable people by greater pressure on users with payment problems and 300,000 shut-offs in 2013 (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015).

The relations between the causes and consequences of the crisis and privatization, as well as the emergence of situations of water poverty (meaning that the costs of water supply exceed 3% of the household budget), have led to the rise of a social movement committed to defend the human right to water as well as the model of public and democratic management (Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020).

4. Social movements for public water in Spain

4.1. A movement for public water

A number of Citizen Water Networks (coalitions of environmental groups, citizen organizations, activists, scholars, and other actors) have emerged from the New Water Culture movement with an aim to defend the social and ecosystematical values of water (Hernández-Mora and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2015). The FNCA is seen as one of the most influential movements in water policy in Spain (Castela-Lopes, 2021). In the beginning of this century these citizen networks were mostly active in opposition to dam construction and river management but also raised a voice for, in their view, marginalized groups in water policies. They demanded influence in decision-making, that was dominated by economic interests of the state and powerful groups (Hernández-Mora and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2015). The citizen networks created large-scale awareness raising campaigns that incorporated many different types of calls to action, but also local social mobilizations against dam projects (Font and Subirats, 2010). One of these networks was the “Red Agua Publica” (RAP) formed in 2012 which focused exclusively on urban water privatization, building on the Plataforma Contra la Privatización del Canal Isabel-II (PCPCYII) that saw light in 2010 in Madrid. This case will be discussed in the next section.

The RAP rose from a local opposition to privatization of the water company in Madrid to an extensive network of organizations in Spain. Until today it promotes a vision of water as a common and a public service with (among others) the following objectives: defending the integral water cycle as a public good; supporting struggles against privatization of water services and for remunicipalization of already privatized services; transparent public water management with citizen participation and effective achievement of the human right to water.1 These objectives were completely in line with the objectives of the European Right2Water movement that emerged in the same year.

The recognition of the human right to water with resolution A/65/254 by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 2010 was a victory for global water activists as well as an inspiration for local activists (Barlow, 2015; Van den Berge et al., 2018). The Italian Water Movement and the referendum they organized, inspired the European Public Services Unions (EPSU) to organize a European Citizens' Initiative on water framing it as a struggle for water as a human right and as a public good. By asking civil society organizations and local water and social movements for support to this EU-wide campaign the Right2Water movement was born. It reciprocally gave support and inspiration to other networks calling for citizen participation in water management and fighting privatization of water supply (Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015; Van den Berge et al., 2018). From 2012 onwards, the European Citizens' Initiative (ECI) “Right2Water” united people and social organizations against water privatization and liberalization policies across Europe (Van den Berge et al., 2018; Bieler, 2021). The Italian Water movement and their successful referendum against water privatization also motivated Spanish activists as they maintained a distance from traditional political parties and called for water to be considered a common (Muehlebach, 2018). Spanish water movements also used the phrasing “write water, read democracy,” introduced by the Italian Water Movement to emphasize this link (Carrozza and Fantini, 2016; Arrojo-Agudo, 2017a).

Widespread disappointment with the service that was provided by private companies (Bakker, 2010; Pigeon et al., 2012; Beveridge et al., 2014; Heilmann, 2018; McDonald, 2018) resulted in reversals of the decisions to privatize water services. Such a reversion has happened in municipalities in developed countries (such as Paris, Berlin, and Budapest), as well as in developing countries (Jakarta and Cochabamba). The remunicipalization of water services in Paris in 2010 was an example for other cities and water activists (Kishimoto et al., 2014; Arrojo-Agudo, 2017b). Municipalities wanted to take back control over their resources so they could better provide for the needs of their citizens and remunicipalization turned to a global trend in the second decade of this century (Kishimoto et al., 2014; Arrojo-Agudo, 2017b; Moore, 2018). Whereas, Spain counted only one case of “remunicipalization” in 2006, the number of re-municipalizations of water services had risen to 14 in 2014 (Kishimoto et al., 2014) and 40 in 2022. Compared to the total number of 135 cases of water remunicipalization worldwide it shows that the Spanish water movement has taken a leading global role in water remunicipalization (Kishimoto et al., 2020; Transnational Institute, 2021; Garcia-Arias et al., 2022).

The main reason for remunicipalization in Spain was the same in all cases: need for investments, guaranteeing universal provision, improving quality of services and taking back control over the service (Pigeon et al., 2012; Kishimoto et al., 2014; Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015; Heilmann, 2018). Moreover, water prices in Spain are on average lower when services are managed by governments (García-Rubio et al., 2015; Lopez-Ruiz et al., 2020) and tend to be higher under private management (Bel, 2020). Average tariff in Spain was about 0.89 €/m3 in 2012, but the highest tariff at that time was in Murcia (1.51 €/m3), followed by Barcelona (1.38 €/m3) and Alicante (1.22 €/m3). In all three places water was provided by subsidiaries of Suez (García-Rubio et al., 2015). Another reason for re-municipalization was the demand for more transparency and democratic control in order to fight corruption (Planas, 2017; Bel, 2020), which was seen as a democratic revolution at the local level, that went beyond water and sanitation management (Arrojo-Agudo, 2017a).

4.2. Confluence of austerity protests and water protests

Protests against the austerity agenda spread, adopting an innovative format in the so-called “indignados” and Occupy movements that occupied public spaces throughout member states of the EU (Parks, 2014). In Spain austerity related policies triggered many protests early 2011 where “Democracia Real Ya” (DRY) developed and grew within 3 months into a protest platform with over 200 organizations affiliated to it (Hughes, 2011). DRY called for demonstrations to take place in cities across Spain a week before the country's regional and municipal elections of May 2011, demanding radical changes in Spanish politics and an end to austerity policies. Mass demonstrations were held across the country on 15 May 2011. The largest of these protests was held in Madrid where demonstrators chanted “we're not merchandise in the hands of politicians and bankers” (Bolger, 2016, p. 26). After attempts by the police to remove the protestors, thousands of supporters occupied squares across Spain to express support for the activists in Madrid. From these solidarity camps, 15-M was born. The activists demanded a reform of the political system and an end to corruption (Bolger, 2016). The involvement of many different actors in the 15-M movement made democratic participatory processes critical to maintain engagement. Since actors can have different backgrounds and motives for joining a movement it is essential to check and debate whether all participants are in the struggle together and to move forward (Moore, 2018).

Protests continued over 2012 and a confluence of tides occurred after the 15-M movement opened up to a new social ecology of critical spaces to protect vulnerable groups (Weiner and Lopez, 2019). Different social movements saw their interest threatened by the same neoliberal ideology that increased pressure on workers and citizens, hitting hardest to the poor and caused a wide spread sentiment of people losing control over their lives (Zacune, 2013; Moore, 2018). Trade unions in Spain joined their forces with 15-M social activists, ecological and water activists. Protests against austerity confluenced with the “marea azul” (“blue wave”) protests against privatization of water and in defense of water as a common good (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015). In 2013 the RAP called on all European public water operators to leave EUREAU (the European federation of national associations of water services) after it had denied the success of the ECI Right2Water, showing its concern of the interests of private operators over the public operators. An impressive list of around 100 groups and organizations from Spain signed the appeal (Red Agua Publica, 2014).

The Right2Water European Citizens' Initiative (ECI) was transferred to Spain by the trade unions affiliated to EPSU—FSC.CC.OO and UGT.SP—and the New Water Culture Foundation. Pedro Arrojo was member of the “citizens committee” of the ECI with an extensive network in Spain. According to him “the ECI was at that time the motor of the struggle for the human right to water in Europe” (personal communication, 27 January 2023). At first the campaign did not strike a chord but that changed when the unions and the water movement bonded with the anti-austerity 15-M movement and then reached a successful number of supporting signatures. The cooperation between the movements was complicated as both the austerity measures as well as the ECI were seen as European Union policy. How to combine action against EU policy and at the same time in favor of another EU policy? This psychological barrier had to be overcome. In the end over 65,000 people signed the Initiative (20minutos.es, 2013), whereas 40,000 were necessary to surpass the quorum, despite of practical barriers (people had to provide passport or fiscal number to give a valid signature). The encouragement of the Association of Public Water Supply and Sanitation Operators (Asociación de Operadores Públicos de Abastecimiento y Saneamiento Agua, AEOPAS), the state-wide Public Water Network (Red Agua Pública, RAP), Ecologists in Action, the Federation of Neighborhood Associations and the Platform against the Privatization of Canal de Isabel II played a role in the success for Right2Water. The Spanish case is a national example of a political achievement reached by uniting diversity as the Right2Water movement did in Europe (Van den Berge et al., 2018). The collaboration of trade unions with social movements was very important. This had not occurred before. Also the combination of social and ecological values and objectives showed to be fundamental for a broad support for implementing the human right to water beyond anthropocentrism (Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020). Spanish water movements have been effective in linking the issue of water with other campaigns e.g., around housing or democratic platforms (Moore, 2018; Castela-Lopes, 2021).

These organizations continued their collaboration in “#Initiativa2015” by which they campaigned to implement the human right to water and achieve a “100% public” service provision in Spain (Limon, 2014). This initiative tried to prohibit supply cuts; to ensure a minimum of between 60 and 100 l per person per day in case of justified non-payment, and to eliminate the participation of private companies in water services. It was about developing a new model of public, democratic, and participatory management (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015). This initiative was materialized a year later in the Social Pact for Public Water (“Pacto Social por el Agua Pública,” PSAP) signed by 75 organizations at the start (Moore, 2018; Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020; Lopez-Ruiz et al., 2020). It led in several municipalities to measures to guarantee a vital minimum of water and prohibition of supply cuts (Red Agua Publica, 2016). The Pact addressed water justice issues and demands that went beyond the topics included in the human right to water and sanitation (HRTWS) and provided a level of specification for its effective implementation (Flores Baquero et al., 2018). Several propositions to implement the HRTWS in legislation had been made but these efforts did not result in its implementation (Limon, 2013c). It shows that the process of incorporating the HRTWS into the national water law, is complex and troubled. Until 2020 and despite the strong social movement and sometimes formal political support, this incorporation has not occurred (Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020). Until today no mention is made of the human right to water in Spanish water law, but the PSAP forms a basis for water policy in municipalities and public utilities as shown e.g., in the Cadiz Declaration in which several majors, water utilities and social organizations in Andalucía state their commitment to implement the human right to water and to ensure that water services remain in public hands (Declaración de Cadiz, 2017). The PSAP is also at the basis of the declaration for public water services management by majors from 10 Spanish cities at the meeting for public water in Madrid on 3–4 November 2016 (Red Agua Publica, 2016).

4.3. Media attention

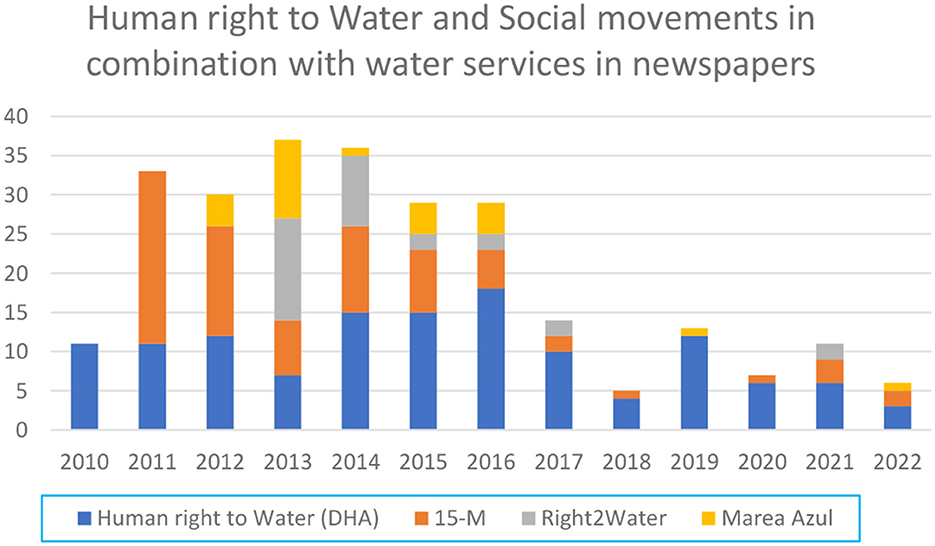

Attention in the media shows how social movements have been able to take the stage in water services debates widely (see Figure 1). The human right to water as recognized by the United Nations General Assembly (2010) was mentioned in the media since 2010 but in 2011 attention to water services provision expanded thanks to the 15-M movement. More attention for the human right to water followed in the wake of the European Right2Water citizens' initiative and the “marea azul” manifestations. The Spanish water movement managed to maintain an important voice in water services debates but media attention decreased.

Figure 1. Number of times that the human right to water and social movements (15-M, Right2Water, and Marea Azul) were mentioned in a newspaper article in combination with “water services” in Spain. Source: own research.

5. Examples of local water struggles in Spain

When the Right2Water campaign was launched in Spain, it could build on an already present network of social movements (Moore, 2018; Van den Berge et al., 2018; Bieler, 2021). These networks appeared indispensable to get people to join the European campaign. This was not easy as anti-European sentiments were also strong because of austerity measures imposed upon Spain by the European Commission that led to increasing unemployment and worsened the economic crisis situation (Center for Economic Social Rights, 2012; Rossi and Gimenez, 2012). Only when European policies were connected to local struggles, the Right2Water campaign started to gain support. In several cities and regions in Spain this local struggle was present in 2012. In this section we explore five cases in which a local social movement was already struggling against privatization or for a more democratic public water supply. Four cases are about cities (Madrid, Valladolid, Terrassa, and Barcelona) and one case is about a region (Andalusia). Madrid shows a fight against privatization; the other three cities show successful cases of remunicipalization (Valladolid and Terrassa) and a failed struggle for remunicipalization (Barcelona). The case of Andalusia highlights how a social movement for public water was built and changed discourse and policy on water management.

5.1. The case of Madrid

The Platform against the privatization of the local water company “Canal de Isabel II” (PCPCYII) was set up in 2010 to oppose the planned privatization of the company in Madrid. It was an urban movement in which social organizations, unions, environmental groups, political parties, and citizens belonging to 15-M participated. The incorporation of the 15-M to the PCPCYII made it possible for the water movement to bond with other social groups—the platforms for the defense of public health and education—that also defended “a right to the city,” imagining the city as a place to live, contrary to, for example, real estate agencies and banks that see the city as a place to exploit (Babiano-Amelibia, 2015). It succeeded in 2012 to organize a popular consultation in which 165,000 people, an overwhelming majority, in Madrid voted against the privatization of the water company and in favor of a 100% public water supply (Plataforma contra la privatizacion del Canal Ysabel-II, 2012; Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2015). This was the first time that a blue wave “Marea Azul” had gone over the city (Pérez, 2012). These blue waves came back in manifestations in 2012 and 2013 for the recognition of the HRTWS in EU law, when the Spanish movements joined the European Right2Water movement. As the struggle unfolded, the movement switched from the earlier emphasis on opposition toward a more prepositive stance, seeking not just to stop privatization but also to make the public utility “100 percent public,” with participatory management involving citizens, making its goals more consistent with the principles of the human right to water. Although formally the government froze the privatization plans in June 2015, because of the heavy defeat experienced in the municipal elections in May that year, the Platform argues that the mechanisms that would allow the privatization to go forward are still in place (Castro, 2018). From the PCPCYII the Red Agua Publica grew that made the Right2Water campaign collaborate with the creation of the Spanish #Iniciativa2015 and the Social Pact for Public Water (PSAP), in close cooperation with AEOPAS and the trade unions.

5.2. The case of Valladolid

In 2015, municipal elections brought in a new government and the opportunity to terminate the private water management contract with Agbar in Valladolid. An important incentive was the lack of investment in the water network under private ownership, although the company had consistently reaped high profits. Another motive was the relative price increase for citizens that had been 78% over 18 years under private concession, whereas the city council foresaw that for the next 15 years a relative increase of 18% would be sufficient to cover all costs of supply if the company would be brought back under public management (Martinez-Fernandez and Redondo-Arranz, 2018). The proposal to re-municipalize the water company was ahead of the elections made by the RAP and strongly supported by AEOPAS and FNCA that had organized local mobilization ahead of the election and made the remunicipalization of water management an important electoral issue (Planas, 2017; Turri, 2022). The new city council organized three rounds of public consultations to ensure participation of citizens, recalling the Right2Water initiative, that in turn increased citizens' support for remunicipalization (Martinez-Fernandez and Redondo-Arranz, 2018). An absolute majority in the City Council approved the remunicipalization of water services in December 2016. This was a milestone in remunicipalizations as it was the first big city in Spain (over 300,000 inhabitants) that brought water service back in public hands. According to the Valladolid City Council direct management would provide the highest profitability with the lowest tariff increase and include all necessary investments (Garcia-Arias et al., 2022). After 2 years in operation, AquaVall, the new public water company had already saved €13.3 million, equivalent to 4% of the city's total budget in 2018 (€337.2 million). So far, the new public company has had a total turnover of €26.4 million. Much of the profits are now used to maintain and improve the city's sanitation and distribution networks (Transnational Institute, 2021). Tariffs have decreased to become among the 10 lowest in Spain (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2019). In a period of 5 years the public company invested 46 million euros in improving its services, against a 20 million euros investment in the 20 years before by the private company (Aquavall, 2022). The company has taken a place in society by putting emphasis on promoting responsible water use, promoting healthy habits, a commitment to respecting the environment and cooperation with cultural and sporting events and various social causes. One of the success factors of the remunicipalization of water services in Valladolid has been the public financing model. Water and sanitation services are entirely financed through tariffs and income remains earmarked for water services. This public financing model, that is comparable to the system in the Netherlands (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat, 2009), has made Aquavall independent from (private or public) banks and led to a sufficiently large cash flow to ensure economic, social, and environmental sustainability (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2019).

5.3. The case of Terrassa

In 2018 after years of debate and social struggle the municipality took back control over the water company when the concession contract with Agbar terminated. The water re-municipalization process has been the result of a long and intense process that has had citizens themselves as the main driving force. Laying a first stone with the signatories of the “Pact for the public management of water in Terrassa,” with the complicity of 8,000 citizen signatures. Principles that must govern the management of the city's public service are new water policy and culture in the city, improvement of efficiency and the effectiveness of the service, the improvement of water quality, the fight against climate change and the forecasting of policies for adaptation and protection of aquatic ecosystems. “We have to display everything that has to do with the human right to water and a fair price, in relation to access to water, thinking of a tariff system that integrates the concept of social justice and human rights” (Aigua es vida, 2018).2

The campaign “Aigua es vida” (water is life), a coalition of community groups, trade unions, solidarity groups, and environmentalists in Catalonia has focused on spreading information, building links with ecological movements, and pushing public debate on the issue. They linked with diverse struggles, looking at the social pact for water, such as in connection with campaigns around housing, austerity or democracy. A Water Observatory was set up as means for citizen participation and to increase transparency and accountability of the new water company toward the inhabitants of Terrassa. The new democratic public model of water management, governed democratically and according to a public ethos, such as in Terrassa, is symbolic and may offer important lessons for other struggles (Moore, 2018).

5.4. The case of Barcelona

In Barcelona, Agbar established a powerful, historically-grown monopoly over the urban water service provision, extending beyond the city's borders by acquisitions of competitors and smaller concessions (Masjuan et al., 2008). In 2010, a local court questioned the regularity of the contract, forcing Agbar and the government body of the Barcelona Metropolitan Area (AMB) to form a PPP model and to establish the mixed-capital entity Aigües de Barcelona Empresa Metropolitana de Gestió del Cicle Integral de l'Aigua S.A (ABEM). As of 2012, ABEM consists of 85% private capital where a majority of 70% is held by Agbar, another 15% belongs to the holding group Criteria (part of the Catalan bank La Caixa) and 15% to the AMB. ABEM and its subsidiaries manage and control up to 93% of the urban water supply in 23 municipalities of the AMB and thus nine out of 10 customers depend on the water supply by the company group (March et al., 2019). Activist groups declared this an abuse of power by the company in collusion with political actors to save the private management involvement and thus their profit revenues under the guise of more public control. In 2016 the Catalan high court declared that ABEM's concession acquisition without a public tender was illegal. This was a victory for the “Aigua es Vida” platform, that argued that only remunicipalization of services into a public and democratic management model could assure necessary investments, measures to improve water quality, protection of water ecosystems and simultaneously create a just and transparent tariff system. A public consultation about a referendum for remunicipalization was organized in 2018 with the help of Barcelona en Comú (BeC), the progressive municipal platform forthcoming from 15-M and other social movements, that has been governing the city since 2015. Activists collected enough signatures, but the referendum was blocked by the opposition of other political parties (Popartan et al., 2020). Subsequently, the MAPiD (Moviment per l'Aigua Pública i Democràtica de Barcelona) was formed to further coordinate protests and alternatives to private management within the AMB. Private actors have often influenced policymaking and public debate about water services through their economic and political power. Tough legal action against any remunicipalization effort also played an important role in Agbar's strategy, but the company had to comply with the Catalan law (Law 24/2015) against shut-off of water supply and accept tariff setting by the AMB.

Through their appeal, in 2019, the Spanish Supreme Court annulled the Catalan high court judgment of 2016. Given this setback for social movements, the only remaining opportunity to re-municipalize water services by legal means would be to dissolve the contract at a high cost through a bailout. Currently, there is no sufficient political will to enforce such procedures and the administrative structure as well as the heterogeneous political composition of the AMB further impede what would necessarily be a “remetropolitization.” However, movements' claims in the context of energy poverty and service problems during the COVID-19 pandemic increased public awareness about water rights as well as about the structural problems caused by the private management model.

5.5. The “Mesa Social del Agua Andaluz”

As a result of cooperation between the RAP-Andaluz, la Marea Azul del Sur, and the Red Andaluz de Nueva Cultura del Agua (RANCA), the social organizations, trade unions, mayors and public water operators agreed upon the above mentioned Declaración de Cadiz, 2017. It has become a point of reference for the Spanish water justice movement (Del Moral-Ituarte, 2017). The social organizations, including also environmental organizations WWF, SEO-Birdlife, Greenpeace, and the agricultural organizations UPA and COAG, have constituted the Andalusian Roundtable on Water (“Mesa Social del Agua de Andalucía:” MSAA), with a strong and active commitment to defend and promote the HRTWS in Andalusia. In a ten-point-plan prepared by the MSAA, an Andalusian Social Pact for Water is proposed that promotes a model of active, fair and diverse citizen participation as the central axis of Integrated Water Cycle policies. It also puts the human right to water and a 100% public management of water services central to achieve socially, ecologically and economically sustainable water management to combat the impacts of the climate crisis and to face the challenges of an environmentally and socially just hydrological transition (Del Moral-Ituarte, 2017). With these proposals the Andalusian coalition goes a step further than implementing the human right to water as it addresses explicitly the needed changes in intensive agriculture and large-scale irrigation. In 2018 the Andalusian government was in a process of revision of the water supply regulation for which a group of social organizations (AEOPAS, FNCA, Ecologistas en Acción, Federación de Consumidores y Usuarios, Fundación Savia, CC.OO, and UGT) proposed the incorporation of the HRTWS into the water regulation with special attention to vulnerable people and with supply of a vital minimum amount of water for free to all citizens. This proposal was not dealt with before the elections that year and was rejected when a new Andalusian government came into power after the elections (Lara-García and Del Moral-Ituarte, 2020). Currently, this struggle lingers on.

6. Who wins, who loses? Water struggles on the ground and in the media

Right2Water landed on fertile ground in Spain as it could engage with the already present anti-privatization sentiments in the country and build on previous social movements focused on water in Spain (Castela-Lopes, 2021). The Andalusian Parliament unanimously supported a motion promoted by the Spanish Association of Public Water and Sanitation Operators (AEOPAS) and by the New Water Culture Foundation (FNCA) for the recognition of the HRTWS and to stop liberalization and commercialization of water services (Limon, 2013b). This can be considered a victory for social movements, even when the Andalusian government did not incorporate the motion in legislation.

Both the Right2Water campaign and the #Initiativa2015/Social Pact for Public Water were successful because they drew together support from many social organizations and labor unions that struggled against the encroachment of privatization impacting everyday life of people. Unlike in Germany, where the European Right2Water movement achieved a lot of media attention thanks to contingency of a well-known comedian promoting the citizens' Initiative on TV (Van den Berge et al., 2018), the water movement in Spain had to conquer the attention of media. They did so successfully in the wake of the 15-M movement as shown in Figure 1. Broad societal pressure appeared to be the strongest force to make governments and water utilities acknowledge water as a common (public) good and a human right (Lopez-Ruiz et al., 2020). Right2Water could capitalize on growing dissatisfaction with water policy, concerns about access to quality water and worry over increasing water privatization. The campaign strengthened the Spanish networks that campaigned against urban water services privatization processes and gave an impulse to remunicipalization processes with regards to water services in several Spanish municipalities. More than 50 municipalities and provincial councils approved in their plenary sessions that water is regarded as a human right and that in their political and territorial geographies it must and will remain outside liberalization and commercialization (Del Moral-Ituarte, 2017). The increasing number of re-municipalizations in Spain was an achievement of the Spanish movements. They also proved to be able to combine national pressure on government with local actions to convince and persuade municipalities and citizens that a “New Water Culture” integrating social and ecological aspects of water management is urgent. As we have scrutinized through various regional and supra-regional cases, the Spanish movement was built on, among others, the three pillars of environmental justice, demanding that its voice was heard and its demands for a socially just water service provision recognized. The demand for public and democratic water services resonated widely in Spain (Planas, 2017; Kishimoto et al., 2020).

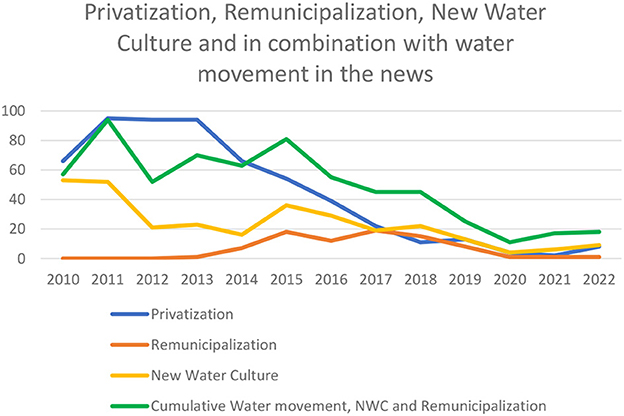

The pressure coming from social movements and from European governing bodies in response to Right2Water were a catalyst for local policy change in Spain. The focus in the debate on water services in the past decade shifted from privatization to re-municipalization. Remunicipalization was an unknown issue until 2013. Claims for a New Water Culture, the human right to water and remunicipalization are all part of the same struggle for water justice, reason why we can witness a cumulative number of mentions in the graph. In 2014 the number of cumulative “pro-water justice” issues and actors surpass the number of “water privatization” in the newspapers (see Figure 2). Moreover, the Spanish movements managed at the same time to turn the tide in local water management as they political-materially achieved a halt to privatization of water and a sharp increase in water remunicipalizations since 2014 (Transnational Institute, 2021).

Figure 2. The number of times that issues “privatization,” “remunicipalization,” or “New Water Culture” were mentioned in Spanish newspaper articles, in relation to “water supply,” and the last two cumulative with water movement organizations in the newspapers over the past 12 years. Source: own research.

The social pact for public water is the continuation of struggles for water that emerged in times of austerity, built on local initiatives and united a diversity of organizations in Spain in a similar way as right2water had done in Europe (Van den Berge et al., 2018). Examples of how the social pact goes beyond the HRTWS and the ECI Right2water demands become manifest in the level of concretization. For instance, as several movement leaders explain, “… when it comes to materializing the human right to water, we will demand the implementation of supply management with criteria of social equity in tariff policies. To do this, it is essential to guarantee a minimum provision... between 60 and 100 l per person per day- and the commitment not to cut off the supply in cases of socially justified non-payment” (Flores Baquero et al., 2018, p. 84). They also make clear how the movement, more than just claiming the HRTWS, also speaks out unequivocally against privatization: “We consider that water and its associated ecosystems are common goods that cannot be appropriated for the benefit of private interests” (Flores Baquero et al., 2018, p. 85). This was also clearly expressed during our meeting with one of the FNCA founding members, Pedro Arrojo who, as was mentioned, is now UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: “There is a direct relationship between the 2 billion marginalized people who lack safe and secure water, and the state of our rivers, polluted, depleted or monopolized by anti-democratic forms of government.” Arrojo c.s. explained to support river governance approaches with a transdisciplinary and transcultural orientation toward “commoning” and “public-commons” co-governance initiatives (see also Riverhood: Boelens et al., 2022). The UN Special Rapporteur: “Achieving better river governance without recognizing the critical role of societal movements in reclaiming environmental justice is impossible” (Arrojo-Agudo, 2023).

Over the past decade the Spanish water justice movement has developed from a single issue (anti-privatization) alliance to a broad movement in favor of a more democratic and holistic water governance in Spain. The call for the democratic management of water services, i.e., that citizens are not just users and owners of the resource but also actively involved in the management, has been successful (Castro, 2018; Bel, 2020; Transnational Institute, 2021). This is a powerful claim, running counter to neoliberalism whilst empowering communities to take back control as well as ownership (Moore, 2018).

7. Conclusions

By the end of the twentieth century struggles for water justice in Spain started with the struggle against the “top down management” of water, stemming from the time that Franco ruled and water was seen as a commodity. Water activists first used the EU Water Framework Directive and later the human right to water as tools to demand for a New Water Culture in which water is considered as a common good. The FNCA organized citizen water networks; local branches to fight for ecologically sustainable and socially just water management at the local (basin) level. Inspiration came from struggles around the world, but most from the Italian water movement and from the ECI “Right2Water.” After the European Commission recognized that water is not a commodity but a public good and water was exempted from the concession directive, the European struggle slowed down, but continued in Spain with renewed energy. Struggles for water justice in Spain coincided with austerity policies in response to the Eurozone crisis and led to a confluence of social movements. An extraordinary broad and strong movement took the struggle further from anti-privatization to pro-democratization of water management and away from the mercantilist view to a holistic eco-social view on the governance of water. The Spanish movement now seems to be the voice that brings this eco-social view to the global water policy arena.

Human rights principles were already brought into the debate on water management in Spain by the FNCA since 2002. It did not resonate until water supply became an intense battle ground of commodification vs. commoning and the negative effects of the “mercantilizacion” of water became more visible when austerity measures hit hard to the poor and “indignados” rose up against it.

The FNCA, RAP, the PSAP, and MSAA are all examples of collective actions to promote a public management of water and working toward water justice. Their struggles are forthcoming from or strengthened by the cooperation of the European Right2Water movement with movements in Spain, with the latter continuing the struggle for water justice in Spain after 2014 in various and sometimes extended compositions led by the RAP. The Spanish water movements achieved recognition of the HRTWS from local and regional governments, awareness around water as a common good and a growing trend of re-municipalizations of water utilities: from 1 case to 14 cases in 8 years between 2006 and 2014 and from 14 to 40 cases in the following 8 years between 2014 and 2022. Remunicipalization is the concretization of water justice struggles in Spain through which the Spanish movement has shown that its powerful and resonating discourse can achieve a shift in local water policy and change the paradigm.

The RAP, FNCA, and AEOPAS played an important role in the water struggles in Madrid, Valladolid, Terrassa and Barcelona. They succeeded in prevention of privatization in Madrid and the re-municipalization in Valladolid and Terrassa, but did not achieve re-municipalization of water services in Barcelona. As we have explained, the cases of Madrid, Valladolid and Terrassa are three examples of how social movements have led to the integration of societal values in water services, each one combining and balancing the 3-fold claim for recognition, redistribution and representation differently. In Barcelona corporate and financial pressure on the municipality was too big to give in to the wish of the population. However, the Catalan law against shut-offs and tariff setting by the AMB can be considered as achievements of the water movement (Tirado Herrero, 2020). The MAPiD continue to mobilize for remunicipalization and plan to create a citizen parliament and a water service observatory to put pressure on private actors and on politicians. Although remunicipalization resonates with many municipalities, the financial and legal barriers to reverse water management from private to public are seen as too high by big cities where (“too big to fail”) corporations control water services. Debates about more democratic water governance are continuing, especially in face of pressures on the water supply through climate change and economic crises. This bottom-up voice is proliferating, as recently was shown in –among multiple others– a side event at the UN Water conference 2023 organized by the Spanish and European water movements (FNCA et al., 2023).

The claim of the human right to water in Spain goes beyond an anthropocentric “HRTWS.” It constitutes today in Spain the banner of a movement that revolves around the concept of water as a common good and aims to build a model of participatory and transparent public water management. The Andalusian roundtable on water (MSAA) goes a step further by including ecological aspects and the agricultural sector in the struggle for water justice. The fact that the HRTWS and the concept of water as a common resonate with so many people seems to coincide with the pursuit of sovereignty of people over their life. Simple as in a slogan “water is life” or “write water, speak democracy” it shows that people act to regain control over water and their lives. The Right2Water movement spotlighted issues arising from water service privatization and liberalization and gave a European platform to local water struggles. Advocacy at the EU-level has helped to build momentum for water mobilization efforts in Spain and reciprocally local mobilization in Spain has helped Right2Water gain success at EU-level despite of different cultural and political motives and backgrounds at the different levels. Notwithstanding social pressure on government and despite the huge efforts by social movements, implementation of the HRTWS in law has not been achieved; neither in the EU, nor in Spain, nor in Andalusia. The main victory of the Spanish water movement may be that it has overcome the differences between organizations and has built an extraordinary broad and strong movement for water democracy that serves as an example for many around the world.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2023.1200440/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AEOPAS, Asociación Española de Operadores Públicos de Abastecimiento y Saneamiento Agua; ABEM, Aigües de Barcelona Empresa Metropolitana; Agbar, Aguas de Barcelona; AMB, Area Metropolitana Barcelona; COAG, Coordinadora de Organizaciones de Agricultores y Ganaderos; DHA, Derecho Humano al Agua; FCC, Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas; FSC-CC.OO, Federacion Servicios a la Ciudadania—Comisiones Obreros; ECI (ICE), European Citizens' Initiative (Iniciativa Europea Ciudadana); EPSU, European Public Services Unions; EUREAU, European Association of Water services providers; FNCA, Fundación Nueva Cultura del Agua; HRTWS, Human Right to Water and Sanitation; MAPiD, Moviment per Aigua Pública i Democrática; MSAA, Mesa Social del Agua Andaluz; NHP, National Hydrologic Plan; PCPCYII, Plataforma Contra la Privatización del Canal Isabel segunda; PSAP, Pacto Social del Agua Pública; PPP, Public-Private-Partnership; RANCA, Red Andaluz de la Nueva Cultura del Agua; RAP, Red Agua Pública; UGT-SP, Union General de Trabajo—Servicios Públicos; UNGA, United Nations General Assembly; UPA, Unión de Pequeños Agricultores y Ganaderos; WWF, World Wildlife Foundation.

Footnotes

1. ^https://redaguapublica.wordpress.com/about/

2. ^https://www.aiguaesvida.org/comunicado-el-futuro-del-agua-publica-en-terrassa-empieza-hoy-con-el-esfuerzo-y-participacion-de-todas/

References

20minutos.es (2013). Organizaciones sociales entregan más de 65.000 firmas en España para pedir que la gestión del agua sea pública. Available online at: https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/1915161/0/ (accessed August 25, 2023).

Aigua es vida. (2018). El futuro del Agua Pública en Terrassa empieza hoy con el esfuerzo y participación de todas. Available online at: https://www.aiguaesvida.org/comunicado-el-futuro-del-agua-publica-en-terrassa-empieza-hoy-con-el-esfuerzo-y-participacion-de-todas/ (accessed August 25, 2023).

Aquavall (2022). Aquavallcumple 5 años como empresa municipal con 46 millones de euros en obras en su historia. Available online at: https://www.retema.es/actualidad/aquavall-cumple-5-anos-como-empresa-municipal-46-millones-euros-obras-su-historia (accessed January 7, 2023).

Arrojo-Agudo, P. (2017a). “El Agua, ? Bien Común o Negocio?,” in Mas claro agua. El plan de saqueo del Canal de Isabel II, ed J. Navas (Madrid: Traficantes de sueños), 38–47.

Arrojo-Agudo, P. (2017b). “La Rebellión de la ciudadanía,” in Mas claro agua. El plan de Saqueo del Canal de Isabel II, ed J. Navas (Madrid, Traficantens de sueños), 48–61.

Babiano-Amelibia, L. (2015). Urban water: commodification and social resistance in Spain. Agua Y Territorio/Water and Landscape 6, 133–141. doi: 10.17561/at.v0i6.2816

Bakker, K. (2003). The political ecology of water privatization. Stud. Polit. Econ. 70, 35–58. doi: 10.1080/07078552.2003.11827129

Bakker, K. (2007). The “commons” vs. the “commodity”: alter-globalization, anti-privatization and the human right to water in the global south. Antipode 39, 430–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00534.x

Bakker, K. (2010). Privatizing Water: Governance Failure and the World's Urban Water Crisis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bakker, K. (2013). Neoliberal vs. postneoliberal water: geographies of privatization and resistance. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 103, 253–260. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2013.756246

Barlow, M. (2015). Our Right to Water: Assessing Progress Five Years After the UN Recognition of the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation. Ottawa, ON: Council of Canadians.

Bel, G. (2020). Public vs. private water delivery, remunicipalization and water tariffs. Utilit. Policy 62, 100982. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2019.100982

Benford, R. D., and Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 26, 611–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

Beveridge, R., Hüesker, F., and Naumann, M. (2014). From post-politics to a politics of possibility? Unravelling the privatization of the Berlin Water Company. Geoforum. 51, 66–74.

Bieler, A. (2021). Fighting for water: Resisting privatization in Europe. London; Bloomsbury: ZED Books.

Bieler, A., and Jordan, J. (2017). ‘Commodification and ‘the commons': the politics of privatising public water in Greece and Portugal during the Eurozone crisis'. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2017, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/1354066117728383

Boelens, R., Escobar, A., Bakker, K., Hommes, L., Swyngedouw, E., Hogenboom, B., et al. (2022). Riverhood: political ecologies of socionature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. J. Peasant Stud. 2022, 1–32. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2022.2120810

Boelens, R., Vos, J., and Perreault, T. (2018). “The multiple challenges and layers of water justice struggles,” in Water Justice, eds R. Boelens, T. Perrault and J. Vos (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–32.

Bolger, B. (2016). The Impact of Social Movements on Political Parties. Examining Whether Anti-austerity Social Movements Have Had an Impact on Social Democratic Political Parties in Ireland and Spain, 2011–2016. Uppsala: University of Uppsala.

Carrozza, C., and Fantini, E. (2016). The Italian water movement and the politics of the commons. Water Alternat. 9, 99–119.

Castela-Lopes, N. (2021). The Impact of Social Mobilizations on Water Policy in the European Union: The Cases of Right2Water Movement, Spain and Portugal. Ottawa, Graduate School of Public and International Affiars (GSPIA), ON: University of Ottawa.

Castro, J. E. (2018). La lucha por la democracia en España: iniciativas desde abajo para defender los servicios de agua esenciales como un bien común. Newcastle: WATERLAT-GOBACIT Network Working Papers, 5.

Center for Economic Social Rights (2012). Spain's Austerity Measures Under the Spotlight. Available online at: https://www.cesr.org/spains-austerity-measures-under-spotlight/ (accessed February 13, 2023).

Clark, C. (2019). Water justice struggles as a process of commoning. Commun. Dev. J. 54, 80–99. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsy052

Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO). (2012). EU Commission Forces Crisis-Hit Countries to Privatize Water. Available online at: http://corporateeurope.org/pressreleases/2012/eu-commission-forces-crisis-hit-countries-privatise-water (accessed August 25, 2023).

Corporate Europe Observatory. (2013). The Battle to Keep Water Out of the Internal Market – A Test Case for Democracy in Europe. Available online at: http://corporateeurope.org/water-justice/2013/03/battle-keep-water-out-internal-market-test-case-democracy-europe (accessed August 25, 2023).

Crow, B., Lu, F., Ocampo-Raeder, C., Boelens, R., Dill, B., and Zwarteveen, M. (2014). Santa Cruz declaration on the global water crisis. Water Int. 39, 246–261. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2014.886936

Declaración de Cadiz (2017). Declaración de Cadiz sobre el derecho humano al agua y la gestión pública del agua, 12 November 2017. Cádiz.

Del Moral-Ituarte, L. (2017). Agua en Andalucía: ? abundancia o escasez? Presiones sistémicas y resistencias locales. Available online at: eltopo.org (accessed October 30, 2017.

Dupuits, E. (2019). Water community networks and the appropriation of neoliberal practices: social technology, depoliticization, and resistance. Ecol. Soc. 24, 20. doi: 10.5751/ES-10857-240220

Dupuits, E., Baud, M., Boelens, R., De Castro, F., and Hogenboom, B. (2020). Scaling up but losing out? Water commons' dilemmas between transnational movements and grassroots struggles in Latin America. Ecol. Econ. 172, 106625. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106625

European Commission (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC of the European parliament and council establishing a framework for the community action in the field of water policy. J. Ref. OJL 327, 1–73.

European Commission (2011). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the council on the Award of Concession Contracts. COM/2011/0897 Final-−2011/0437 (COD). Brussels.

Fattori, T. (2013). The European Citizens' Initiative on Water and ‘Austeritarian' Post-Democracy. Transform 13/2013, 116–122. Available online at: http://www.transform-network.net/journal/issue-132013/news/detail/Journal/the-european-citizens-initiative-on-water-and-austeritarian-post-democracy.html (accessed August 25, 2023).

Feindt, P. H., and Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 7, 161–173. doi: 10.1080/15239080500339638

Flores Baquero, O., Cabello Villarejo, V., Lara García, A., Hernández-Mora, N., and Del Moral Ituarte, L. (2018). “El debate sobre el Derecho Humano al Agua en España: la experiencia del Pacto Social por el Agua Pública,” in La lucha por la democracia en España: iniciativas desde abajo para defender los servicios de agua esenciales como un bien común. WATERLAT-GOBACIT Network Working Papers, ed J. E. Castro (Newcastle: WATERLAT-GOBACIT), 68–88.

FNCA RAP ISF, AEOPAS, EPSU, EWM, RAPA, Red VIDA. (2023). Seminario “Gobernanza democrática de los servicios de agua y saneamiento”. Available online at: https://fnca.eu/78-observatorio-dma/1656-gobernanza-democratica-de-los-servicios-de-agua-y-saneamiento (accessed March 21, 2023).

Font, N., and Subirats, J. (2010). Water management in Spain: the role of policy entrepreneurs in shaping change. Ecol. Soc. 15, 225. doi: 10.5751/ES-03344-150225

Forsyth, T. (2003). Critical Political Ecology: The Politics of Environmental Science. London: Routledge.

Fraser, N., Dahl, H. M., Stoltz, P., and Willig, R. (2004). recognition, redistribution and representation in capitalist global society: an interview with nancy fraser. Acta Sociol. 47, 374–382. doi: 10.1177/0001699304048671

Garcia-Arias, J., March, H., Alonso, N., and Satorras, M. (2022). Public water without (public) financial mediation? Remunicipalizing water in Valladolid, Spain. Water Int. 2022, 4. doi: 10.4324/9781003344292-4

García-Mollá, M., Ortega-Reig, M., Boelens, R., and Sanchis-Ibor, C. (2020). Hybridizing the commons. Privatizing and outsourcing collective irrigation management after technological change in Spain. World Dev. 132, 104983. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104983

Garcia-Rubio, M., Lopez-Ruiz, S., and Gonzalez-Gomez, F. (2019). Human rights in Spain: protection of the right to water in families with affordability problems. Crit. Anal. Legal Reform 13, 103–114. doi: 10.17561/at.13.4381

García-Rubio, M. A., Ruiz-Villaverde, A., and González-Gómez, F. (2015). Urban water tariffs in Spain: what needs to be done? Water 7, 1456–1479. doi: 10.3390/w7041456

Gonzalez-Gomez, F., García-Rubio, M. A., and Gonzalez-Martínez, J. (2014). Beyond the public-private controversy in urban water management in Spain. Utilit. Policy 2014, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2014.07.004

Hall, D., and Lobina, E. (2005). The Relative Efficiency of Public and Private Sector Water. Available online at: http://gala.gre.ac.uk/3628/1/PSIRU_9607_-_2005-10-W-effic.pdf (accessed August 25, 2023).

Hall, D., and Lobina, E. (2012). Water Companies and Trends in Europe 2012. Greenwich: University of Greenwich, Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU).

Heilmann, M. R. A. (2018). Trends of Remunicipalisation of public water management. Revista Int. Consinter de Direito 6, 181–205. doi: 10.19135/revista.consinter.00006.09

Heller, L. (2020). A/75/208: Human Rights and the Privatization of Water and Sanitation Services (Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, Léo Heller). New York, NY: United Nations.

Hernández-Mora, N., Cabello, V., De Stefano, L., and Del Moral-Ituarte, L. (2015). Networked water citizen organisations in Spain: potential for transformation of existing power structures in water management. Water Alternat. 8, 99–124.

Hernández-Mora, N., and Del Moral-Ituarte, L. (2015). Developing markets for water reallocation: revisiting the experience of Spanish water mercantilización. Geoforum 62 143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.011

Hughes, N. (2011). Young people took to the streets and all of a sudden all of the political parties got old: the 15M movement in Spain. Soc. Mov. Stud. 10, 407–413. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2011.614109

Ioris, A. A. (2016). Water scarcity and the exclusionary city: the struggle for water justice in Lima, Peru. Water Int. 41, 125–139. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2016.1124515

Kishimoto, S., and Hoedeman, O. (2015). Leaked EU Memorandum Reveals Renewed Attempt at Imposing Water Privatisation on Greece. TNI. Available online at: https://www.tni.org/en/article/leaked-eu-memorandum-reveals-renewed-attempt-at-imposing-water-privatisation-on-greece (accessed March 8, 2023).

Kishimoto, S., Lobina, E., and Petitjean, O. (2014). Here to Stay: Water Remunicipalisation as a Global Trend. London; Amsterdam: Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), Transnational Institute (TNI), and Multinational Observatory (CEO).

Kishimoto, S., Steinfort, L., and Petitjean, O. (2020). The Future Is Public: Towards Democratic Ownership of Public Services. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Lara-García, Á., and Del Moral-Ituarte, L. (2020). El derecho humano al agua en España en el contexto europeo (2010-2020). Implicaciones para las políticas y los modelos de gestión del ciclo urbano. Relaciones Internacionales 45, 305–326. doi: 10.15366/relacionesinternacionales2020.45.014

Limon, R. (2013a). La presión social saca el agua de la directiva europea de privatizaciones. El País. Available online at: http://sociedad.elpais.com/sociedad/2013/07/01/actualidad/1372702820_342386.html (accessed January 7, 2023).

Limon, R. (2013b). La Iniciativa Ciudadana Europea sobre el derecho al agua entrega las firmas. El País. Available online at: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2013/09/10/andalucia/1378815772_943724.html (accessed January 7, 2023).

Limon, R. (2013c). IU propone medidas legales para frenar las privatizaciones de servicios de agua. EL País. Available online at: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2013/02/08/andalucia/1360322345_802085.html (accesed January 20, 2023).

Limon, R. (2014). Organzaciones ciudadanas y partidos lanzan un pacto por el agua pública. El País. Available online at: http://ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2014/08/23/andalucia/1408786978_205688.html (accessed January 20, 2023).

Lobina, E. (2014). Troubled Waters, Misleading Industry PR and the Case for Public Water. Boston, MA: Corporate Accountability International and PSIRU.

Lopez-Gunn, E. (2009). “Agua para todos”: the new regionalist hydraulic paradigm in Spain. Water Alternat. 2, 370–394.

Lopez-Ruiz, S., Tortajada, C., and Gonzalez-Gomez, F. (2020). Is the human right to water sufficiently protected in Spain? Affordability and governance concerns. Utilit. Policy 63, 101003. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2019.101003