- 1Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Water for Women Fund Coordination Team, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3School of Strategic and Global Studies, Gender Studies Graduate Program, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

The recent (re-)emergence of gender-transformative approaches in the development sector has focused on transforming the gender norms, dynamics, and structures which perpetuate inequalities. Yet, the application of gender-transformative approaches within water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programing remains nascent as compared with other sectors. Adopting a feminist sensemaking approach drawing on literature and practice, this inquiry sought to document and critically reflect on the conceptualization and innovation of gender-transformative thinking in the Australian Government's Water for Women Fund. Through three sensemaking workshops and associated analysis, participants developed a conceptual framework and set of illustrative case examples to support WASH practitioners to integrate strengthened gender-transformative practice. The multi-layered framework contains varied entry points to support multi-disciplinary WASH teams integrating gender equality, as skills and resources permit. Initiatives can be categorized as insensitive, sensitive, responsive or transformative, and prompted by five common motivators (welfare, efficiency, equity, empowerment, and transformative requality). The framework has at its foundation two diverging tendencies: toward instrumental gender potential and toward transformative gender potential. The article draws on historical and recent WASH literature to illustrate the conceptual framework in relation to: (i) community mobilization, (ii) governance, service provision, and oversight, and (iii) enterprise development. The illustrative examples provide practical guidance for WASH practitioners integrating gendered thinking into programs, projects, and policies. We offer a working definition for gender-transformative WASH and reflect on how the acknowledgment, consideration, and transformation of gender inequalities can lead to simultaneously strengthened WASH outcomes and improved gender equality.

Introduction

Gendered thinking in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector was initially prompted in the 1970's during an overlap of the International Decade for Women and the International Decade for Water and Sanitation (1975 to 1981). Yet four decades on, transformative models of gender equality for WASH policies, programs, and projects are only recently emerging (Sinharoy and Caruso, 2019; MacArthur et al., 2022a). Notably, the sector's historical focus on infrastructure, has been less concerned with social gender issues (Fisher et al., 2017; Sweetman and Medland, 2017). Additionally, WASH has been associated with historically male dominated disciplines such as public health, engineering, and management (Udas and Zwarteveen, 2010; Willetts et al., 2010; Zwarteveen, 2010; Alda-Vidal et al., 2017; World Bank, 2019) and hence the sector has been slow to adopt concepts such as equality and diversity (Cavill et al., 2020; Worsham et al., 2021).

The perspective that gender equality can contribute to a range of development outcomes and be an outcome of development interventions itself is articulated as a gender-transformative approach (Kabeer, 1994). In other terms, gender-transformative initiatives aim to transform relational, collective, and structural gender inequalities alongside and through other development interventions (MacArthur et al., 2020, 2022a). A gender-transformative approach is characterized by: (1) starting from a purposefully transformative agenda (why); (2) engaging with structural systems and not the symptoms of inequality (where); (3) maintaining a focus on strategic gender interests (what); (4) recognizing and valuing diverse identities (who); and (5) adopting transformative methodological approaches (how) (MacArthur et al., 2022a). However, in contrast to development sectors such as health and food systems, gender-transformative thinking is nascent and unclarified in the WASH sector (MacArthur et al., 2022a).

As seen in the “pioneering” emergence of gender-transformative approaches in food systems initiatives (AAS, 2012; McDougall et al., 2021), the uptake of transformative thinking required a concerted effort by practitioners to address the lack of sectoral progress on gender equality. The process involved building coalitions between practitioners, academics, and donors for the “conceptualization and innovation” of gender-transformative approaches (McDougall et al., 2021, p. 3). The gender-transformative food systems coalitions intentionally sought to adapt learnings from reproductive health programming, defining tailored frameworks, language, and areas of focus (McDougall et al., 2021). Like food systems, the WASH sector has seen slow progress in addressing gender inequalities (Sinharoy and Caruso, 2019). As such, a concerted effort to adapt and adopt a gender-transformative approach to WASH was promoted in the Water for Women Fund (2018–2022). Funded by the Australian Government, the Water for Women Fund sought to promote the development of coalitions and innovations in gender-transformative approaches through socially inclusive and sustainable WASH projects and research in 15 countries in Asia and the Pacific. Notably, the Water for Women Fund actively looked beyond a gender-binary and adopted concepts of intersectionality to more holistically address gender and social inequalities (Water for Women, 2019b).

Drawing on existing published experiences and three summative sensemaking workshops with six academics and leaders from the Water for Women Fund, this inquiry had two objectives. Firstly, to document and critically reflect on the conceptualization and innovation of gender-transformative thinking in the Water for Women Fund. Secondly, to identify a conceptual framework and set of illustrative case examples to support future WASH practitioners in adopting a more gender-transformative approach. A third emergent outcome was the critical interrogation of the common frameworks used in other gender-transformative initiatives—gender-integration continuums.

The article begins by introducing several connection points between gender equality and WASH, providing definitions related to gender and development, and clarifying two conceptual models which have been used to classify and describe different forms of gender-integration in development programming. Following this, we describe the inquiry's approach, which comprised of three sensemaking workshops drawing on existing published cases and the experiences of the Australian government's Water for Women Fund. The results section begins with the introduction of a framework of gender-integration suitable for the WASH sector. Next, the study illustrates the framework's application in three types of WASH activities: (1) community mobilization, (2) governance, service provision and oversight, and (3) enterprise development. In the discussion, framed by six characteristics of a gender-transformative approach (MacArthur et al., 2022a), the paper provides key considerations for WASH programs interested in adopting gender-transformative perspectives. Finally, the article reflects on future research needs before offering concluding remarks.

Background

Reasons for integrating gender equality in WASH initiatives

Existing literature has identified several philosophical, cultural, biological, and programmatic reasons to integrate WASH and gender equality. First, WASH is important to the full enjoyment of life for all; including women, girls and those who have been historically marginalized. Global mandates including the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) and the recognition of the human right to water and sanitation highlight the importance of WASH for the full enjoyment of life (Singh et al., 2008; JMP, 2021). Second, WASH activities in the home and community are strongly gendered. In many cultures, women and girls are traditionally responsible for household WASH, yet men are responsible for water management in the public arena (White et al., 1972; Elmendorf and Isely, 1981; van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985). Third, improvements in WASH are often not equitable. Women, girls, and the socially marginalized have been the least likely to benefit from improvements in WASH (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1998; Fisher et al., 2017). Fourth, not everyone has the same WASH-related biological needs. For example, women and girls face unique WASH challenges during pregnancy, lactation, menstruation, and menopause (Hulland et al., 2015; Sahoo et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2017). Sexual and gender minorities also have specific needs, though these are often overlooked (Boyce et al., 2018). Fifth, the integration of gender equality into WASH policies and programs can lead to improved WASH outcomes (Taukobong et al., 2016). The active engagement of women and the socially marginalized, has been shown to lead to improved efficiency, sustainability, and effectiveness of WASH systems (Van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1987; Mommen et al., 2017). This said, some authors have noted that these interventions must be careful to avoid exploitative approaches which do not foster agency (Cornwall, 2001; Cavill and Huggett, 2020). Lastly, and often overlooked in the WASH sector, improvements in WASH can (but are not guaranteed to) foster improved gender equality and social inclusion outcomes (Ivens, 2008; Willetts et al., 2010; Gender and Development Network, 2016)—this perspective is key to gender-transformative modalities of WASH.

Gender equality terms and definitions

A gender-transformative perspective of WASH necessitates a clear foundational articulation of gendered concepts grounded in feminist development (Kabeer, 1994; Cornwall and Rivas, 2015). Firstly, the term gender. This paper defines gender as the socially constructed structures and dynamics which govern a society's perspectives of masculinity and femininity (Butler, 1999). Gender is one category of intersectional historical oppression (Crenshaw, 1989), other categories include: “race, class…sexuality, gender identity, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age” (Collins, 2015, p. 2). An intersectional approach therefore considers how categories of historical oppression intersect. As such, while this paper focuses specifically on gender equality, many scholars and practitioners have considered aspects of social inclusion and gender equality jointly. Secondly, this paper conceptualizes gender equality as the state of “equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys [and individuals of diverse genders]” (Hannan, 2001, p. 1). Notably, we add the clause related to the inclusion of other genders, recognizing a shift in thinking from binary to diverse genders. Drawing from the Beijing Platform for Action (United Nations, 1995), gender equality is distinct, yet closely linked with women's empowerment and gender equity. We define gender equity as “fairness of treatment…” [for individuals of all genders] “…according to their respective needs” (UNESCO, 2000, p. 5) and empowerment as “the processes by which those who have been denied the ability to make choices acquire such an ability” (Kabeer, 1999, p. 437). Therefore, the paper conceptualizes gender equality as a transformed status of society, with empowerment and equity as important precursors.

Foundational conceptual models

Although gender-transformative approaches within international development have seen significant resurgence in recent years (MacArthur et al., 2022a), the concepts and perspectives can be traced to the 1990s in the lead up toward the Beijing Platform for Action (United Nations, 1995). At this time, two main conceptual models emerged to help classify and clarify different types of gendered programming (March et al., 1999). Both conceptual models were premised on the idea that gender-transformative programming is best classified in contrast to other less or non-transformative modalities.

The first model, articulated by Moser (1993), identified a loose evolution of gender-integrated programs focused on welfare, equity, anti-poverty, efficiency and finally empowerment (Moser, 1993). Table 1 introduces the key definitions of the five program types drawing on Moser (1993, p. 56–57) and Coates (1999, p. 6). Moser's model drew on foundational work by feminist development practitioner Buvinić (1986); who described the “misbehavior” of women-focused development policies which she argued had slipped from opportunities to empower women toward purely practical gender outcomes. While such practical gender outcomes are important for overall health and wellbeing, they are not able to address gender inequalities as strategic gender interests (Buvinić, 1986; Moser, 1993). The framework articulates a series of program motivations and was first adopted in the WASH sector in 1999 by WaterAid (Coates, 1999). Moser herself argues that many approaches were used in parallel and that even in the 1990s, welfare-based approaches were common (Moser, 1993).

Table 1. Differing policy approaches to women and development (adapted from Moser, 1993; Coates, 1999).

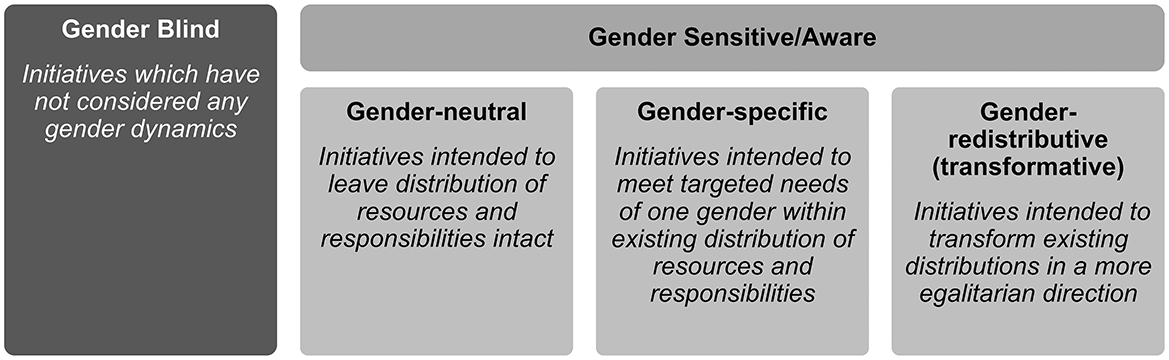

The second model, articulated by Kabeer (1994) and Kabeer and Subramanian (1996), identified four types of development programs: gender-blind, gender-neutral, gender-specific and gender-transformative; the latter three types classified as gender-aware (1996) or gender-sensitive (1994). Figure 1 illustrates the framework and provides key definitions for the four classification types.

Figure 1. Classifications of gender policy, adapted from Kabeer (1994) and Kabeer and Subramanian (1996).

In the 20 years which have followed, the second framework has appeared as a continuum in many forms and in three streams of practice focused on relational health, institutional structures, and sectoral change (MacArthur et al., 2022a). Most notably the continuum has been adapted for relational and reproductive health programming (Gupta, 2001; ICRW and Promundo, 2007; Rottach et al., 2009; WHO, 2011; Pederson et al., 2015), with a few emergent examples in climate programming (Harvey et al., 2019) and WASH (Grant, 2017; Grant et al., 2017; WaterAid, 2017; Water for Women, 2019b). A visual summary of these diverse continuums is provided in Supplementary material. It should be noted that most these examples are found in gray literature and that little has been written to critique and interrogate the conceptualization of the continuum in practice.

Approach

The inquiry utilized a process of feminist sensemaking, building on insights from both literature and practice. The feminist sensemaking approach was selected to solidify and document the lessons and insights of gender-transformative thinking within the Water for Women Fund (2018–2022). Rooted in the constructivist paradigm, feminist sensemaking is a collaborative approach in which targeted discussions are focused on (1) creating sense of a complex topic and (2) constructing “cognitive bridges” through which to communicate and influence policy (Rutledge Shields and Dervin, 1993). Feminist sensemaking can involve structured interviews, focus groups, or workshops, with specific discussion topics and a goal of greater “sense” of the topic. We adopted a workshop format of feminist sensemaking in which the six workshop participants were also the co-authors of this paper and aimed to extend the team's experiences in the Water for Women Fund. The participants included researchers with specialist expertise in the gender-WASH nexus and in the Water for Women Fund (MacArthur, Carrard, Siscawati and Willetts), and Water for Women Fund specialists in gender equality and social inclusion (Mott), and monitoring and evaluation (Raetz). Participants were selected to best maximize the learnings of the fund, while keeping workshop discussions manageable in a short time-period.

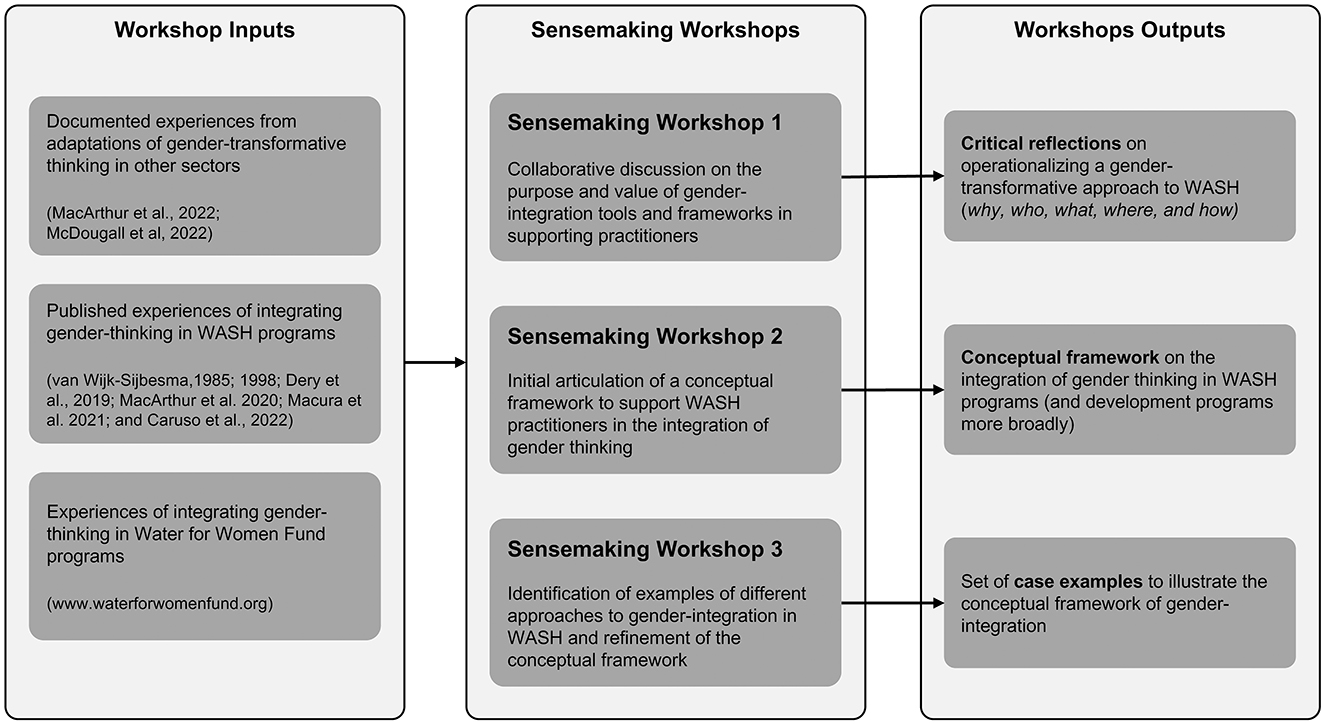

As illustrated in Figure 2, the inquiry built on existing literature and practice in the WASH sector through three sensemaking workshops with an overall goal of identifying and interrogating tools and examples to best support WASH practitioners. The 1.5-hour workshops were conducted using Zoom between July and September 2022. Agendas of the three workshops were emergent, yet each workshop had a specific goal as indicated in Figure 2. The lead author prepared brainstorming topics, collaborative templates, and input materials before each workshop. Email discussions continued between the participants between workshops to help clarify ideas and insights. The workshop inputs included gender-integration experiences from other sectors (see Supplementary material), gender-WASH literature (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985, 1998; Dery et al., 2019; MacArthur et al., 2020; Caruso et al., 2022; Macura et al., 2023), and Water for Women Fund experiences in the “Toward Transformation” strategy (Water for Women, 2019b). Relevant case examples were documented in an online database (stored in Airtable) and referred to throughout the workshops. The workshop outputs included critical reflections, a conceptual framework, and relevant case examples.

The collaborative approach sought to bring each team members' knowledge and experience to bear in pursuit of both scholarly rigor and practical relevance. Each workshop is briefly described below.

The first workshop focused on defining the purpose and value of gender-integration tools and frameworks, critically considering their different forms, applications and limitations based on literature and practice. The discussion relied on examples and frameworks from other sectors (McDougall et al., 2021; MacArthur et al., 2022a) alongside the lessons and insights from the Water for Women Fund. This discussion confirmed our collective perspective that such frameworks offer value in translating concepts into practice, despite limitations associated with their linear presentation and inherently problematic approach to discrete categorization of complex activities. The first workshop produced a set of critical reflections on the common gender-integration frameworks and on the challenges and opportunities of gender-transformative approaches in WASH programming.

The second workshop aimed to codify an appropriate framework for supporting WASH practitioners in integrating a gendered approach. The workshop relied on examples of gender-integrated WASH programming within to identify framework terminology and design. Notably, this workshop included detailed discussions on the motivators that implicitly shape WASH programs and how these motivators are closely aligned with typical gender-integration categories. The second workshop produced a working conceptual framework that was then used and refined in the third workshop.

In the third workshop, the team reviewed a pre-developed database of literature case studies and discussed examples from our own experiences to illustrate and refine the proposed gender-integration framework. We sought geographically diverse examples relevant to three WASH program focus areas based on Water for Women Fund initiatives: community mobilization; governance, service delivery, and oversight; and enterprise development. Where examples were lacking in literature, we developed hypothetical scenarios about the ways in which such programs could align with gender integration categories, based on our experiences in the WASH sector. For example, as no published literature case was found on gender-sensitive WASH enterprise development, we discussed and created a hypothetical example supporting women latrine sales agents. Our focus on diversity was intentionally aimed at redressing the dominance of Kenya, India, and Bangladesh in published WASH-gender literature (MacArthur et al., 2020).

This inquiry and its outcomes must be interpreted through its limitations related to the study team, minimal external validation, and complexity in identifying relevant case studies. Firstly, while the study team came from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, the members were all associated with the Water for Women Fund. Additionally, five of the six members were based at Australian institutions. This positionality reduced opportunities to engage with perspectives more broadly and to draw on diverse insights. To mitigate this, the team actively engaged with documented experiences from partner organizations across the Water for Women Fund which covers some 15 countries in Asia and the Pacific, however future research could bring more diverse voices into the study team. Secondly, although this study validated the framework conceptually and through the practical lens of Water for Women Fund experiences, there was not an opportunity to engage external voices in the validation and critique of the framing. The inquiry's team sees the framework as a starting place and welcomes further reflection, critique, and experiences to support future evolution of gender-transformative initiatives in the WASH sector. Lastly, there are few academically published case studies describing WASH program initiatives and outcomes in relation to gender equality. Therefore, the team was required to rely heavily on historical examples (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985, 1998), gray literature cases known to the team, and recent gender-WASH literature reviews (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985, 1998; Dery et al., 2019; MacArthur et al., 2020; Caruso et al., 2022; Macura et al., 2023). Future work could benefit from a systematic case study review of gender-WASH programming examples from both gray and published literature. Despite these limitations, the goal of this work has been to provide an initial translation of gender-transformative concepts, language, and approaches for a sector slow to address inequalities.

Results

Conceptual framework of gender-integration

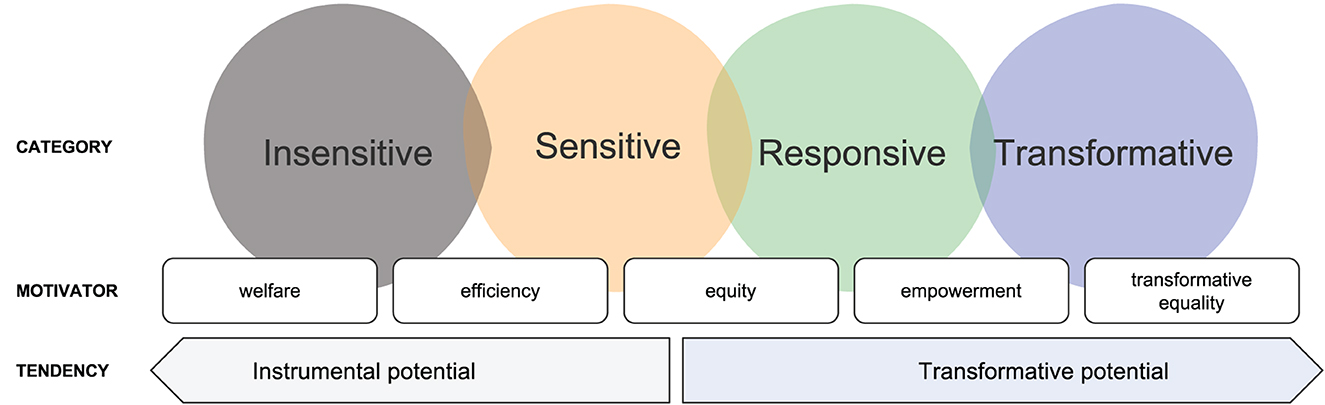

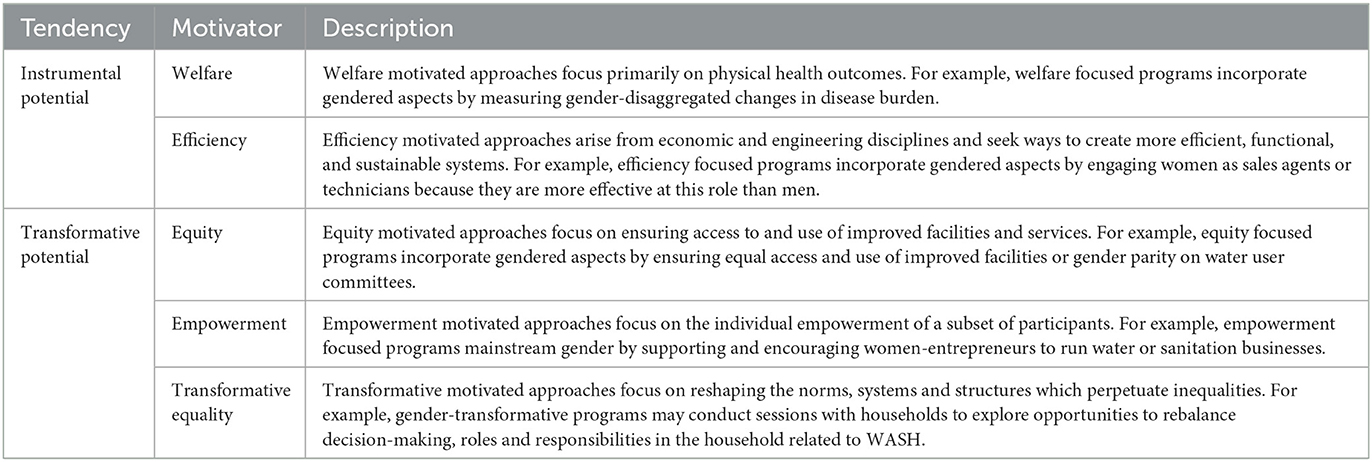

The adaptation of existing gender-integration thinking to the WASH-sector led to the development of a three-layered framework (Figure 3) which includes: four gender-integration categories, five motivators, and tendencies toward instrumental and transformative potential. While the framework was reviewed and interrogated for WASH initiatives, the insights and outputs from the process may have relevance in other sectors. We begin by introducing the framework and its categories, then describing the motivators and tendencies.

The design of the three-layered framework was selected to best support varied entry points for practitioners. Building on previous multi-layered frameworks (Kabeer, 1994; Rottach et al., 2009; Pederson et al., 2015), the sensemaking process clarified the importance of multi-purpose tools that are appropriate for different types of program staff. Where gender specialists are more likely to resonate with the four gender-integration categories due to their alignment with gender theory, program managers and evaluators may more easily make sense of the five motivators (drivers or mechanisms) which distinguish key influences likely to shape program design. The orientation can also help to quickly identify the direction of the program toward either instrumental or transformative objectives.

We acknowledge that a program or policy may not be easily classified into a single category or motivator, since any program or policy may employ more than one strategy, and also because interventions are inherently shaped by implementing staff (including their relative gender-related critical consciousness) and the way in which staff facilitate interventions (Cavill et al., 2020). As such, an intervention that on paper might be classified as one category, might in practice be implemented based on characteristics of another.

Categories of gender-integration in WASH programs

The four categories of gender-integration in WASH programs align with and refine previously developed frameworks of gender-integration for development programming more broadly. They include insensitive, sensitive, responsive, and transformative categories and follow a progression from left-to-right toward higher engagement with gender theory and practice. The categories in the framework were carefully defined and named by reviewing and problematizing existing frameworks and approaches in the first sensemaking workshop. Notably, we drew language from the Canadian International Development Research Centre, which used the terms gender-blind, -sensitive, -responsive, and -transformative (Harvey et al., 2019).

Gender-insensitive approaches do not consider any gender dimensions and are sometimes referred to as gender blind, harmful or unaware by other scholars and practitioners (Kabeer, 1994; Rottach et al., 2009; WHO, 2011; Khanna et al., 2016). We purposefully avoid the common term “blind” to be sensitive to individuals with vision impairment. Additionally, we do not label this approach as “harmful” or “exploitative” as these phrases are less approachable as entry points for program teams. This said, we recognize that gender-insensitive approaches often have harmful effects and instrumental tendencies. A gender-insensitive approach is likely to maintain the status quo and perpetuate, if not exacerbate, existing social inequalities (Mott et al., 2021) and they often “foster damaging stereotypes” (Gupta, 2001, p. 10). In WASH, a gender-insensitive approach is often associated with technology transfer programs such as handpump or latrine installations which do not consider gender dynamics (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985).

Gender-sensitive approaches acknowledge gender dynamics in the development of interventions; however, work within the traditional or existing dynamics and structures of a context. The approach is also referred to as neutral (Kabeer, 1994), aware (Mott et al., 2021), or inclusive (WaterAid, 2017). We adopt a similar framing to Gupta (2001), who defines a gender-sensitive approach with reference to HIV/AIDS interventions as “programming that recognizes and responds to the differential needs and constraints of individuals based on their gender.” (p. 9). Similar in content, but with a different label, Kabeer and Subramanian (1996) describe this type of approach as “gender neutral” which seeks “to target the appropriate development actors in order to realize certain pre-determined goals and objectives, but…leave the existing divisions of resources, responsibilities and capabilities intact.” (p. 10). As such, gender-sensitive approaches often adopt gender-specific modalities, targeting a single gender for program interventions. For example, in WASH this could include conducting gender analysis, but focusing more on meeting women's practical needs rather than addressing their strategic gender interests.

Gender-responsive approaches consider gender dynamics with an intention to empower individuals, but do not aim to remove or address wider structural barriers (Mott et al., 2021). This approach is also known as gender-accommodating or empowering. This concept aligns most closely with Gupta's (2001) final spectrum level “approaches that empower” and WaterAid's “empowering” step toward transformation. This category is often focused on the individual empowerment of a single-gender group of participants. In WASH programs, this includes a focus on meaningful participation, decision-making, and leadership of marginalized groups (Dery et al., 2019).

Lastly, gender-transformative approaches actively seek to transform the gender norms, structures, and dynamics which perpetuate inequalities within households, communities, and institutions (MacArthur et al., 2022a). Kabeer and Subramanian (1996) describe this form of programming as gender-redistributive seeking to “transform the existing gender relations in a more egalitarian direction through the redistribution of resources and responsibilities” (p. 10). Often transformative approaches adopt gender-synchronous strategies—purposefully engaging individuals of different genders both separately and together to address individual, collective, and structural gender interests (Greene and Levack, 2010). Additionally, the transformative approach includes the attention to or even integration of intersecting aspects to accommodate diversities and at the same time addressing plural forms of marginality and marginalization (not only gender-based but also based on class, caste, ethnicity, age, ability, etc.). In WASH, this has included examples such as using water and sanitation monitoring opportunities to transform gender relations (Leahy et al., 2017) or the purposeful engagement of men and boys in menstrual hygiene management (Mahon et al., 2015).

Gender-integration motivators for WASH programs

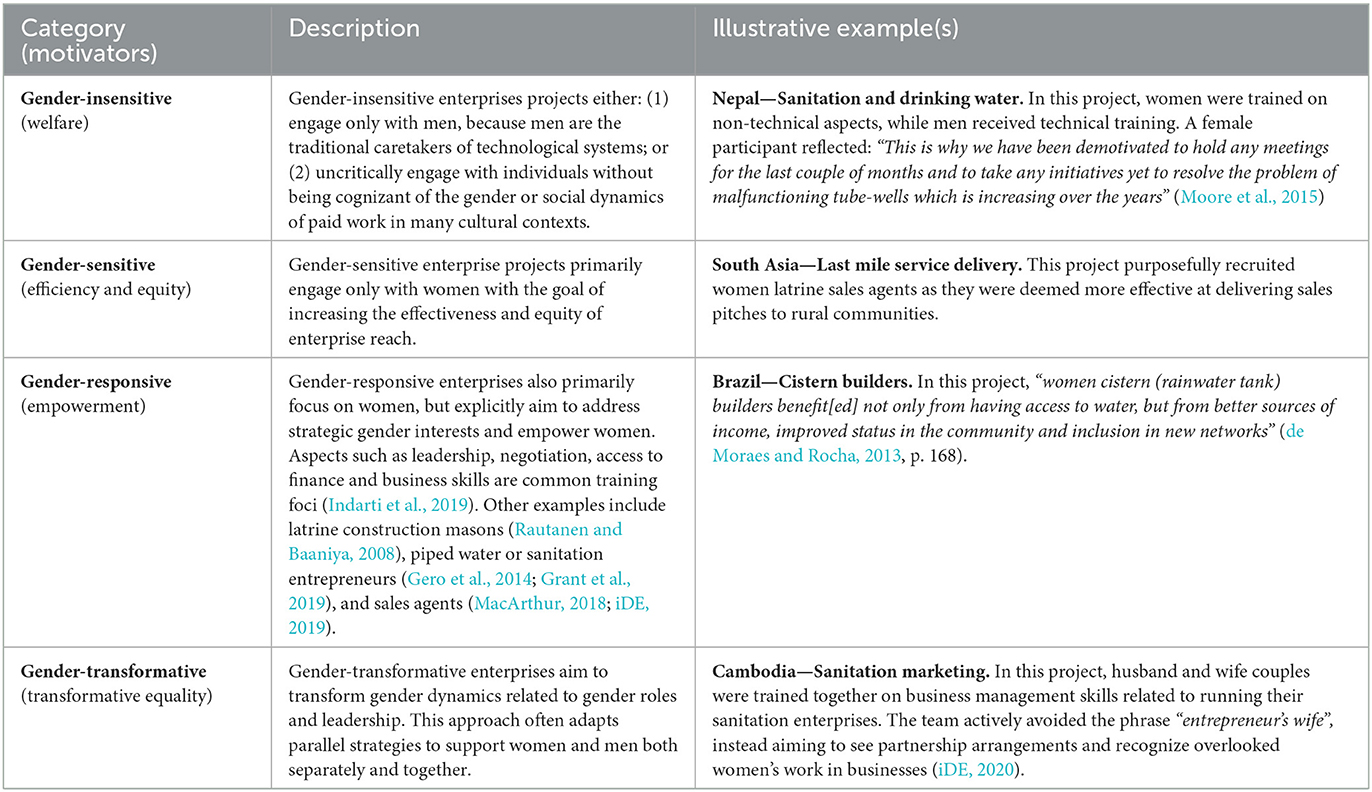

Building on the four categories of gender-integration to address the workshops revealed difficulties in articulating the differences between the categories, leading to the inclusion of the five motivators (Table 2).

Table 2. Program design motivators and potential (adapted from Moser, 1993; Coates, 1999).

The five proposed motivators (welfare, efficiency, equity, empowerment, and transformative equality) broadly align with Moser's (1993) categories of the evolution of gender programming introduced in this article's background section (welfare, equity, anti-poverty, efficiency, and empowerment). However, we have made four changes to Moser's initial conceptualization.

First, we disconnected the spectrum from an evolutionary timeline (from the 1940s to today). Although, Moser conceptualized that programs have loosely evolved from focusing on welfare (1940s) toward empowerment (1990s), later theorists (see for example Kabeer 1994) have argued that modern programs can also adopt welfare (or efficiency or equity) based approaches. However, we maintain that the motivators build on one another—in that a program motivated by efficiency is also inherently providing welfare, and that a program motivated by equality would also embody aspects of welfare, efficiency, equity, and empowerment.

Second, we merged the anti-poverty motivator from Moser's initial conceptualization with the efficiency and equity motivators. Emerging as a “toned-down version of equity” in the 1970s, the anti-poverty approach focused on ensuring that poor women increased their productivity. In practice today, the anti-poverty approach has been very similar to the efficiency “smart economics” discourse (Cornwall and Brock, 2005; Chant, 2012).

Third, we swapped the locations of equity and efficiency in the spectrum to better align with continuum from practical gender needs (left) toward strategic gender interests (right). Both Moser (1993) and Coates (1999) have argued that an equity based approached was aligned with strategic gender interests, while an efficiency approach has more instrumental tendencies.

Fourth, we added a fifth motivator highlighting the (re)-emerging discourse around gender-transformative development (MacArthur et al., 2022a) The addition of transformative equality adopts the feminist perspective that empowerment has lost its initial potency, focusing exclusively on individual women, and placing the burden of change on women (Batliwala, 2007; MacArthur et al., 2021). Hence the final motivator of transformative equality goes beyond individual empowerment to reflect a transformed society more broadly.

The motivators operate as a parallel spectrum and within our sensemaking workshops, motivators were often identified by the types of outcomes that programs monitored or evaluated. Notably, drawing on the case study examples, the team identified that the motivator of “equity” can have both instrumental and transformative tendencies, while the other motivators were more clearly aligned with one or the other tendency.

Potential tendencies in integrating gender in WASH programs

The two tendencies reflect the inclination or propensity of programs integrating gender-considerations (instrumental and transformative). Programs with instrumental tendencies integrate gender considerations primarily to improve other practical outcomes such as WASH coverage, functionality, use, and sustainability—focused more on practical gender needs. As such, programs with instrumental tendencies are more likely to inadvertently “exploit” women or require women's involvement without clarifying if and how women would like to be involved or will benefit from their involvement (Cornwall, 2001). This may also include inadvertently adding to women's triple burden and being unresponsive to backlash they may experience. Alternatively, transformative WASH programs recognize that improvements in practical WASH outcomes can contribute to improvements in strategic gender interests related to agency, societal norms, and structural changes. Gender-transformative WASH programs also recognize the need to focus on power and norms change more broadly to achieve gender and social equality, often with a focus on intersectionality and do-no-harm.

This dichotomy of instrumental and transformative potential aligns with the distinction between practical gender needs and strategic gender interests (Moser, 1993). However, we adopt the word “potential” responding to critiques that many outcomes do not neatly align with either practical or strategic interests and ideally should span both as both are interconnected (Kabeer, 1994; Wieringa, 1994). As such, we highlight the potential of programs rather than their specific alignment with practical or strategic interests. For example, handwashing campaigns often adopt “good mums” strategies which have an instrumental tendency in contrast to a gender-transformative tendency which would see hand hygiene as an “entry point to challenging norms and promoting more equitable sharing of household responsibilities among men and boys” (Cavill and Huggett, 2020, p. 34).

Illustrative gender-integration case examples

In this section we present the selected intervention examples from literature to illustrate the nuanced differences between gender-insensitive and gender-transformative approaches in WASH. The selected examples represent a small subset of potential examples from literature and practice, noting that many potential examples displayed significant similarities despite being from different decades, countries, and perspectives of gender-integration. We purposely draw heavily on examples from the 1980s and 1990s (van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1985, 1998), to avoid negatively identifying current programs or organizations engaged in WASH sector activities. This use of historical examples additionally highlights that these challenges are not new, but have existed for the last 40 years in the sector. Each section presents examples of the four categories of gender-integration alongside an illustrative discussion of potential activities to guide future practitioners. The three case study topics aim to reflect the breadth of practice within the WASH sector including aspects of: community mobilization, governance, and enterprise development.

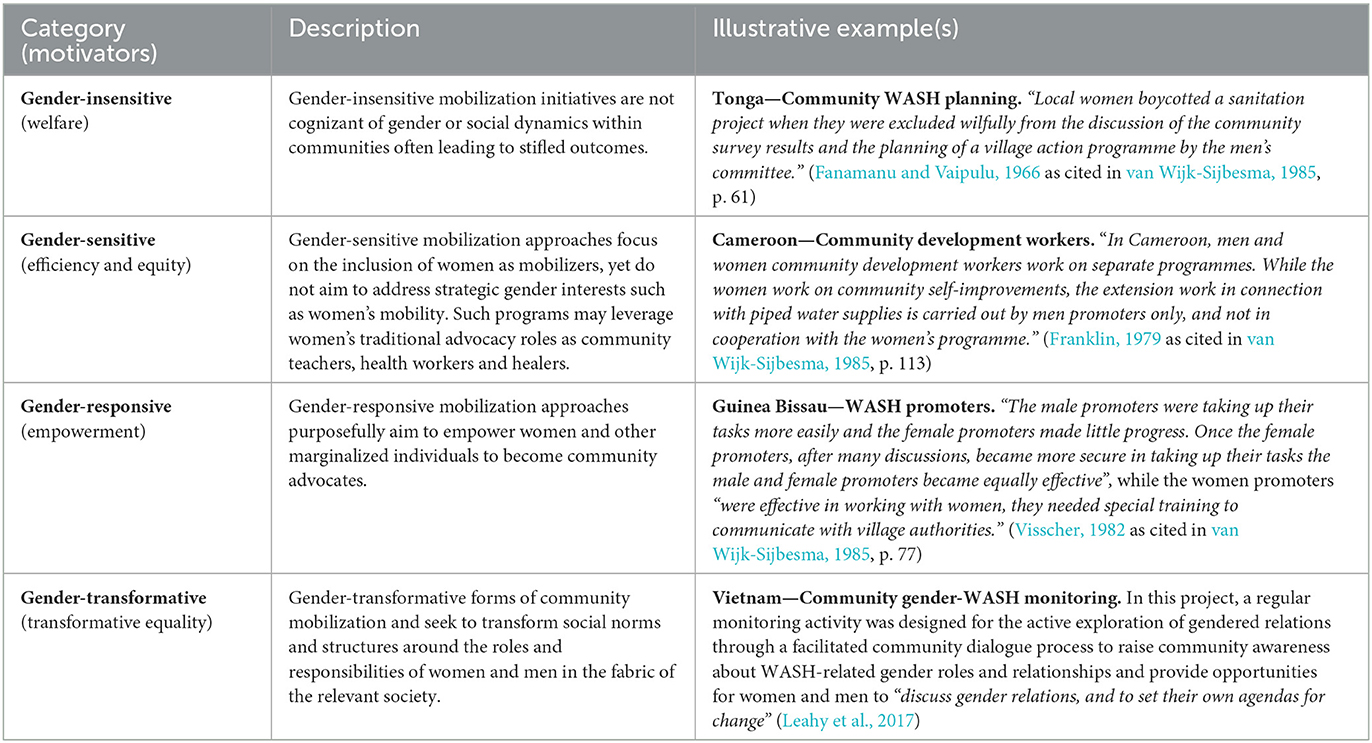

Community mobilization

A common tenet of WASH implementation, community mobilization includes activities such as Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST), as well as activities to set the foundation for community involvement in water system development. Mobilization or promotion activities involve collaborative processes of critical reflection leading to action. Promoters are often community-leaders and volunteers who advocate for improved water, sanitation, and hygiene within their communities. Such activities are closely linked to processes of action research such as Participatory Rapid Appraisal (PRA) and community health initiatives.

Table 3 summarizes how WASH programs focused on community mobilization can align with the four categories of the gender-integration framework. Illustrative examples are drawn from the Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia with a focus on historical case studies.

Gender-transformative community mobilization in WASH contends that diverse community members are best placed to drive, lead, and sustain change in WASH services. Change is catalyzed in community mobilization through facilitation that aims to transform social norms, stimulating and trigging demand for services. Provision of information leads to greater awareness of health risks and benefits from WASH among community members who interpret and act on information based on gendered norms within their social and cultural context. Community-led total sanitation (CLTS) for instance seeks to change behavior by triggering disgust or shame among community members through a facilitated process and sometimes emphasizes the importance of handwashing after critical times (Kar and Chambers, 2008). Community mobilization can reinforce or challenge social norms to trigger and motivate change, which inherently can reinforce or contest existing gender roles. Intersectional attention to gender and social dimensions (such as gender, class, caste, ethnicity, religion and age) in relation to the diversity of the mobilizers and how and with whom the mobilization process is conducted in the community both affect the extent to which a community mobilization activity in WASH is likely to have transformative potential and achieve transformative outcomes.

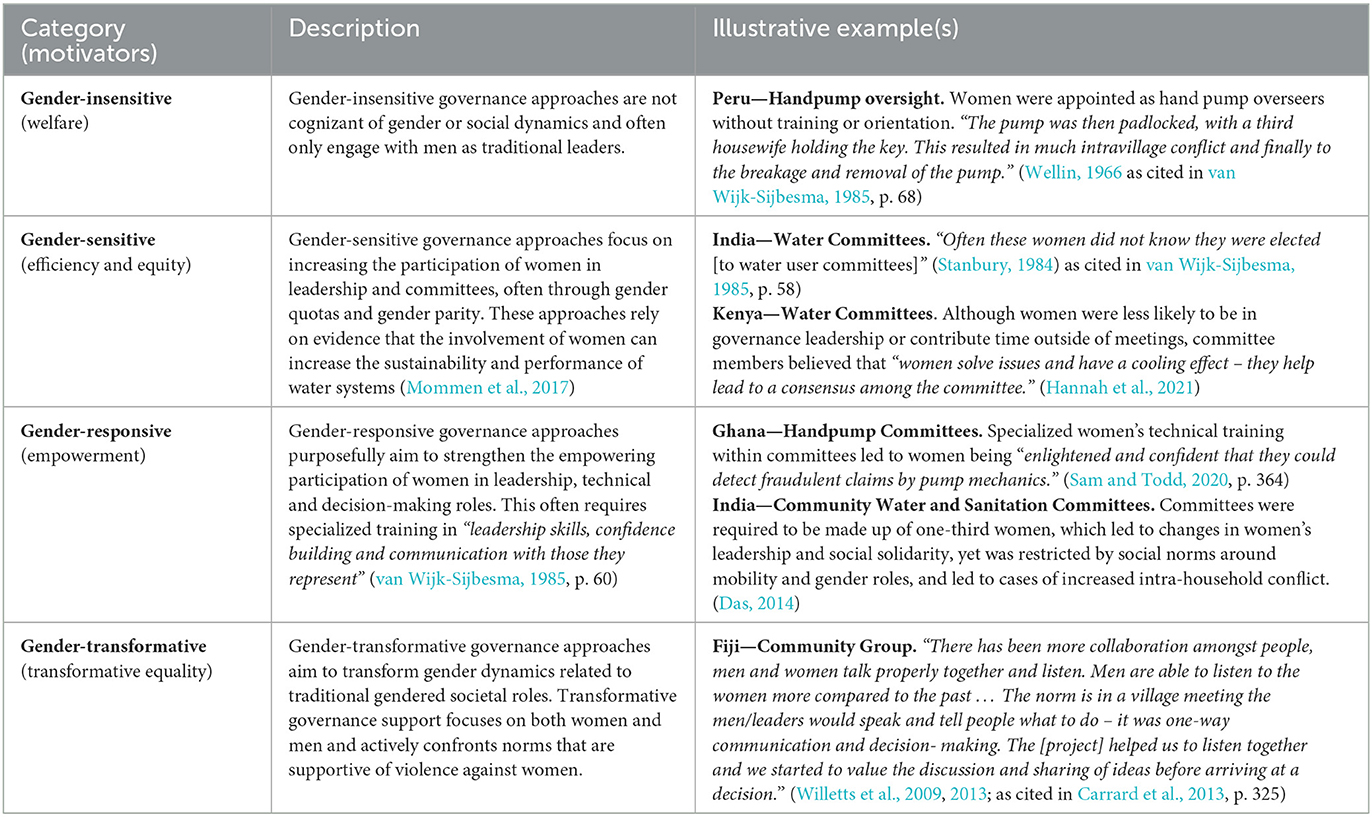

WASH governance, service provision, and oversight

Governance of water and sanitation services includes interventions that provide support for different service provision modalities, including water and sanitation committees, water user associations and direct local government service provision, or may also focus on local government planning, monitoring and oversight as a service authority. Programs supporting these types of initiatives address gender in relation to concepts of leadership, decision-making, participation, and oversight—moving from tokenistic forms of engagement governed by “patriarchal culture, scepticism and negative stereotypical assumptions”, (Mandara et al., 2017, p. 116) toward active and informed participation by diverse community members. As most of the informal management and governance engagement in WASH is unpaid, this can potentially lead to women's “triple burden” (Moser, 1993). More formal governance roles that are paid are more likely to have more positive outcomes for women, but can also lead to backlash and resistance if perceived as threatening to existing traditions and hierarchy, highlighting the importance of do-no-harm within gender-integrated WASH interventions.

Table 4 provides examples of how WASH programs focused on WASH governance, service provision and oversight can align with the four categories of WASH gender-integration. Once again, illustrative examples are drawn from around the globe including South America, sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific. The examples include aspects of community handpump oversight, water and sanitation committees, and community management groups.

Gender-transformative governance, service provision, and oversight holds that increased substantive participation of women and marginalized groups in WASH institutions leads to better, more appropriate services for diverse user groups. Substantive participation goes beyond nominal or passive participation towards sustained and active engagement (Das, 2014). Governance involves working within existing institutional structures to create more civic space for women and marginalized groups to engage in decision making on matters that affect their interests (Fauconnier et al., 2018; Imburgia, 2019; Sehring et al., 2022). Support may be provided to address the informal and formal barriers to participation within civic spaces such as committees, forums, platforms or within organizations (Das, 2014). This also requires supporting more diverse governance and leadership at institutional levels to strengthen the linkages between household, community, and institutions (Grant et al., 2021; Worsham et al., 2021; Gonzalez et al., 2022b). For instance, practical strategies such as making meetings more convenient (time and place) may enable women and diverse groups to participate and have a voice in WASH governance processes (Carrard et al., 2013). Civic engagement in WASH governance by diverse user groups can also be a means for advancing strategic gender interests by addressing underlying causes of disadvantage. Ongoing monitoring by users can then in turn reinforce positive feedback loops by emphasizing the accountability of duty bearers for service delivery. By embedding gender relations and interests within institutional structures a gender-transformative governance program assumes that change and the potential for transformation will be enduring.

WASH-related enterprise development

Enterprise development includes a variety of income generation roles in the private sector for women and men within WASH such as technicians, mechanics, sales agents, and entrepreneurs. Sometimes these types of roles overlap with work in WASH committees. In some cases, paid roles have aimed to leverage traditional gendered roles of women and men—such as men as mechanics and women as community health workers, however more transformative examples have aimed to transform notions of masculine and feminine work, such as men in care work and women in technical roles. Once again, the four types of gender-integration are not mutually exclusive and may be overlapping.

Table 5 provides examples of how programs focused on enterprise development in WASH can align with the four categories of the WASH gender-integration framework. The bulk of potential examples emerge from South America, South Asia and Southeast Asia highlighting the lack of examples of gender-integrated enterprise development in sub-Saharan Africa. The gender-sensitive example is hypothetical and drawn on author's experiences as to not negatively identify any one organization or program. Additionally, these examples are more recent and there is less historical literature to draw on in WASH enterprise development (Gero et al., 2014).

Gender-transformative enterprise development seeks to realize opportunities for women's empowerment by addressing barriers to participation in overall market systems. Women's ability to participate in the economy and public sphere is shaped at multiple levels by domestic, household, community, and institutional norms (Carrard et al., 2013). By addressing these norms systematically women can benefit from participation in WASH enterprises as an entry point for broader change (Grant et al., 2019; Indarti et al., 2019; Soeters et al., 2020). Adopting parallel strategies to engage men and women in WASH enterprise development can support women's participation; for instance, by initiating dialogue on paid and unpaid labor and gender roles (Soeters et al., 2020). Like other strategies the potential for unintended consequences such as backlash must be managed carefully by embedding do-no-harm approaches into enterprise development and working closely and intentionally with women's rightsholder organizations (Water for Women, 2022a). Women's entrepreneurship can also be motivated through financial benefits from business development thus reinforcing the value and transformative potential of WASH enterprises.

Discussion

This paper has documented the results of three sensemaking workshops in the development of a conceptual model and identification of a set of illustrative case studies. The examples of gender-transformative WASH programming noted above and in emerging literature confirm that WASH can provide an entry point for wider gender-transformative change with synergistic benefits to both WASH and societal transformations. Such a gender-transformative approach to WASH provides a framework for leaving no one behind, increasing diversity amongst those overseeing, providing, and benefiting from WASH services whilst concurrently supporting greater gender equality. These examples also offer insight into the complexity of achieving multiple and demanding objectives, particularly in confined program timeframes.

Drawing on the purposed framework and illustrative cases, this article proposes the following working definition: A gender-transformative approach to WASH aims to transform gender norms, structures, and dynamics both within and beyond WASH-related behaviors, activities and services in households, communities, and institutions. As such, gender-transformative WASH pursues gender equality and WASH outcomes simultaneously, in mutually reinforcing ways.

We now discuss key considerations for organizations seeking a gender-transformative approach as critical reflections from the first sensemaking workshop. The considerations align with five framing questions for practitioner teams interested in integrating gender-transformative approaches (MacArthur et al., 2022a): why, who, what, where and how.

Increasingly research and practical experience points to the importance of self-awareness and organizational culture when grappling with questions for gendered norms and power structures (Cavill et al., 2020). That is, an individual and collective sense of, and commitment to “why” a gender-transformative approach is important. Such reflexivity acknowledges that transformation must begin within individuals and adopts a purposeful objective of social and gender-transformations (Heijnen and van Wijk-Sijbesma, 1993; Cavill et al., 2020; MacArthur et al., 2022a). This requires a collective agreement that WASH programming can and should influence gender norms, dynamics, and structures. As such, a foundational step for WASH professionals and organizations is to critically reflect on our own perspectives and practices. Tools such as Water for Women's Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Toward Transformation Self-Assessment Tool (Mott et al., 2021) can support awareness and identify priorities for action in programming and organizational systems. Importantly, transformative programming is difficult to realize without a transformative culture within the organization (Cavill et al., 2020; Water for Women, 2022a). Collaboration with rights holders' organizations can support this kind of transformation, ensuring WASH efforts are informed by lived experience and capacity building on appropriate pathways for change.

Second, a gender-transformative approach requires actively partnering with diverse genders and integrating intersectional perspectives, involving attention to “who” is involved. Additionally, a transformative approach actively aims to engage men and boys rather than solely focusing on women (Cavill et al., 2018; MacArthur et al., 2020). The active engagement of gendered or marginalized groups separately and together, is the practice of gender-synchronization (Greene and Levack, 2010). This synchronizing strategy can also be adapted to addressing plural forms of marginality and marginalization from intersecting forms of oppression (Collins, 2015; Soeters et al., 2019).

Next, the focus of gender-transformative WASH—“what” to address—must span practical and strategic interests rather than assuming that meeting practical needs is a precursor for engaging with strategic interests. One example is that of gender-based violence. A gender-transformative approach recognizes the social acceptance of gender-based violence as a barrier to societal transformation, and pro-actively plays a role in addressing this while ensuring a do no harm approach. While the WASH sector has historically explored themes of gender-based violence from an infrastructure perspective—ensuring safety and privacy in design—there has been a more recent shift to focusing on shifting attitudes and norms that support gender-based violence (Sommer et al., 2015; Pommells et al., 2018). For example, within the Water for Women Fund, some projects have supported the development and socialization of violence referral pathways in collaboration with rights holder groups through their community WASH activities.

Fourth, it is important to recognize that gender-sensitive, responsive, and transformative approaches are all valuable in the movement toward more equal futures for all. The question of “where” an intervention focuses, whether at specific or systemic level needs to be taken into account. Program teams and designers should be realistic and even cautious in considering the ability for small-scale (or short-term) interventions with limited resources to address systemic changes. Systems change requires approaches that scale up, outm and deep (Water for Women, 2022b). As such different interventions will inherently have different objectives and addressing WASH needs varies in terms of required timeframes and scales. Scaling up aims to impact laws and policies, scaling out aims to replicate and disseminate best practice, and scaling deep aims to impact societal and cultural norms (Moore et al., 2015). In some cases, programs with limited resources and support may be better suited to adopt gender-sensitive solutions avoiding potential backlash and harm. As such, all gender-integrated interventions should articulate and implement a robust do-no-harm approach, which acknowledges that resistance and backlash is inevitable when prevailing power structures are challenged, and works to intentionally mitigate these risks (Water for Women, 2019a).

Finally, gender-transformative approaches require more nuanced and additional funding, planning, and assessment modalities which promote reflective and iterative approaches (MacArthur et al., 2022a), and thus significant attention to the “how”. This is required for instance, for the intentional, meaningful, and reciprocal engagement with rightsholder organizations to improve WASH and gender equality outcomes as well as ensuring that intersecting marginalizations such as disability, are integrated into gender-transformative approaches. An increased focus on norms changes and addressing power and privilege furthers the importance of iterative and flexible approaches such as action research. Program structures must encourage practitioners to question the status quo and reveal and interrogate unintended negative effects (Water for Women, 2022b).

As a minimum, all programs, no matter whether they aim to be sensitive, responsive, or transformative, require methods to monitor and reflect on the resultant gender and social outcomes, both intended and unintended. Without this, it is not possible to know whether the envisaged outcomes have been achieved or whether adverse outcomes have also occurred. There is an emerging body of literature and tools to support both quantitative and qualitative measurement of gender outcomes associated with WASH programs (Carrard et al., 2013, 2022; Gonzalez et al., 2022a; MacArthur et al., 2022b,c).

Future research priorities

While this article has aimed to introduce gender-transformative WASH into global scholarship and practice, there is still much to be done to refine, expand and clarify the concept and its use by practitioners.

For example, this article has limited its application of the gender-integration framework to three particular program types. Future research could expand the spectrum's applicability to other integral WASH interventions related to menstrual hygiene management and handwashing, which both offer significant entry points to address gender norms (Cavill et al., 2018; Cavill and Huggett, 2020). These areas were included within our initial database, yet we found a lack of documented evidence. As such, these types of WASH activities are underrepresented in our illustrative examples. Further work could beneficially explore how the spectrum can be applied to support menstrual hygiene programs that go beyond gender specific to also being gender-transformative (Mahon et al., 2015; Cavill et al., 2018), and drive handwashing interventions that achieve critical hygiene outcomes while also addressing social norms (Cavill and Huggett, 2020).

Additionally, the reflected framework could be applied and refined in further contexts and sectors with diverse actors and a range of program types. In particular, future work could explore how the framework could be further developed to (1) assess and drive transformative programming, (2) clarify ways to communicate the underlying concepts, (3) promote critical engagement, and (4) identify opportunities to create meaningful translations and visual formats to promote its uptake.

While the framework and examples were focused on highlighting the experience of the Water for Women Fund's adoption of gender-transformative thinking, the critical reflections from the inquiry have relevance and value in other sectors. For example, our problematization of the term “gender-blind” or the recognition that gender neutral interventions have a useful do-no-harm value could be adopted by other practitioners in food security and reproductive health.

Lastly, future work could explore how practitioners engage with and use the framework to strengthen gender-WASH programming and to support potential gender-transformative initiatives. In particular, the research team is curious to understand how the multi-level framing resonates with practitioners from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds and how the motivators and potentials clarify complex gender-terminology for less familiar audiences.

Conclusions

A gender-transformative approach to WASH aims to transform harmful gender dynamics and norms (interpersonal connections and relationships) and structures (societal rules and systems) within, through and alongside WASH interventions. Gender-transformative WASH aims to synergistically both address gender and social inequalities and improve WASH outcomes.

The paper proposed a multi-level gender-integration framework applied to WASH programming -contexts to support practitioners in the thoughtful application of more transformative policies, programs, and projects. The conceptual model defined a gender spectrum in relation to gender-insensitive, gender-sensitive, gender-responsive and gender-transformative types, with relevant motivators and potentials. Using the framework, the paper synthesized experiences from gender-WASH literature and the Water for Women fund through the lens of gender-transformative approaches in international development. Future practice can benefit from applying this framework in the design, implementation, monitoring, and assessment of WASH with a goal of fostering transformative potential.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JMa, NC, and JW: conceptualization. JMa and NC: methodology and writing—original draft preparation. JMa, NC, JMo, SR, MS, and JW: collaborative sensemaking, data curation, and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the DFAT Water for Women Fund (grant number WRA-034).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the Water for Women fund research and implementation partners within the toward transformation agenda. This paper silently draws on a breadth of experiences from across Asia and the Pacific through fund experiences and interventions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2023.1090002/full#supplementary-material

References

AAS (2012). Building Coalitions, Creating Change: An Agenda for Gender Transformative Research in Development. CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12348/938 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Alda-Vidal, C., Rusca, M., Zwarteveen, M., Schwartz, K., and Pouw, N. (2017). Occupational genders and gendered occupations: the case of water provisioning in Maputo, Mozambique. Gender Place Cult. 24, 974–990. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1339019

Baker, K. K., Padhi, B., Torondel, B., Das, P., Dutta, A., Sahoo, K. C., et al. (2017). From menarche to menopause: a population-based assessment of water, sanitation, and hygiene risk factors for reproductive tract infection symptoms over life stages in rural girls and women in India. PLoS ONE 12, e0188234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188234

Batliwala, S. (2007). Taking the power out of empowerment - An experiential account. Dev. Pract. 17, 557–565. doi: 10.1080/09614520701469559

Boyce, P., Brown, S., Cavill, S., Chaukekar, S., Chisenga, B., Dash, M., et al. (2018). Transgender-inclusive sanitation: insights from South Asia. Waterlines 37, 102–117. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.18-00004

Butler, J. (1999). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 10th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Buvinić, M. (1986). Projects for women in the third world: explaining their misbehavior. World Dev. 14, 653–664. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(86)90130-0

Carrard, N., Crawford, J., Halcrow, G., Rowland, C., and Willetts, J. (2013). A framework for exploring gender equality outcomes from WASH programmes. Waterlines 32, 315–333. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2013.033

Carrard, N., MacArthur, J., Leahy, C., Soeters, S., and Willetts, J. (2022). The water, sanitation and hygiene gender equality measure (WASH-GEM): Conceptual foundations and domains of change. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 91, 102563. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102563

Caruso, B. A., Conrad, A., Patrick, M., Owens, A., Kviten, K., Zarella, O., et al. (2022). Water, sanitation, and women's empowerment: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Water 1, e0000026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pwat.0000026

Cavill, S., Francis, N., Grant, M., Huggett, C., Leahy, C., Leong, L., et al. (2020). A call to action: organizational, professional, and personal change for gender transformative WASH programming. Waterlines 39, 219–237. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.20-00004

Cavill, S., and Huggett, C. (2020). Good mums: A gender equality perspective on the constructions of the mother in handwashing campaigns. wH2O: J. Gender Water. 7, 26–36. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/wh2ojournal/vol7/iss1/4 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Cavill, S., Mott, J., Tyndale-biscoe, P., Bond, M., Huggett, C., and Wamera, E. (2018). Engaging Men and Boys in Sanitation and Hygiene Programmes. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, CLTS Knowledge Hub. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/14002 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Chant, S. (2012). The disappearing of “smart economics”? The World Development Report 2012 on Gender Equality: Some concerns about the preparatory process and the prospects for paradigm change. Glob. Soc. Policy 12, 198–218. doi: 10.1177/1468018112443674

Coates, S. (1999). A Poverty-Reduction Approach to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programmes. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/a-poverty-reduction-approach-to-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-programmes-1999 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Cornwall, A. (2001). Making a Difference? Gender and Participatory Development. Institute of Development Studies. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13853 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at “participation”, “empowerment” and “poverty reduction.” Third World Q. 26, 1043–1060. doi: 10.1080/01436590500235603

Cornwall, A., and Rivas, A. M. (2015). From ‘gender equality and ‘women's empowerment' to global justice: Reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Q. 36, 396–415. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ. Chicago Legal Forum 1989, 139–167.

Das, P. (2014). Women's participation in community-level water governance in urban india: the gap between motivation and ability. World Dev. 64, 206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.025

de Moraes, A. F. J., and Rocha, C. (2013). Gendered waters: the participation of women in the “One Million Cisterns” rainwater harvesting program in the Brazilian Semi-Arid region. J. Clean. Prod. 60, 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.03.015

Dery, F., Bisung, E., Dickin, S., and Dyer, M. (2019). Understanding empowerment in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH): a scoping review. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 10, 5–15. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2019.077

Elmendorf, M., and Isely, R. (1981). The Role of Women as Participants and Beneficiaries in Water Supply and Sanitation Programs. Available online at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNAAL379.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Fanamanu, J., and Vaipulu, T. (1966). Working through the community leaders: an experience in Tonga. J. Health Educ. 9, 130–137.

Fauconnier, I., Jenniskens, A., Perry, P., Fanaian, S., Sen, S., Sinha, V., et al. (2018). Women as Change-Makers in the Governance of Shared Waters. Gland: IUCN.

Fisher, J., Cavill, S., and Reed, B. (2017). Mainstreaming gender in the WASH sector: Dilution or distillation? Gend. Dev. 25, 185–204. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331541

Gender Development Network (2016). Achieving Gender Equality Through WASH. London. Available online at: www.gadnetwork.org (accessed March 11, 2019).

Gero, A., Carrard, N., Murta, J., and Willetts, J. (2014). Private and social enterprise roles in water, sanitation and hygiene for the poor: a systematic review. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 4, 331–345. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2014.003

Gonzalez, D., Abdel Sattar, R., Budhathoki, R., Carrard, N., Chase, R. P., Crawford, J., et al. (2022a). A partnership approach to the design and use of a quantitative measure: co-producing and piloting the WASH gender equality measure in Cambodia and Nepal. Dev. Stud. Res. 9, 142–158. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2022.2073248

Gonzalez, D., Carrard, N., Chhetri, A., Somphongbouthakanh, P., Choden, T., Halcrow, G., et al. (2022b). Qualities of transformative leaders in WASH: a study of gender-transformative leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Water 4, 1050103. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2022.1050103

Grant, M. (2017). Gender Equality and Inclusion in Water Resources Management. Global Water Partnership Action Piece, 24. Available online at: http://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/about-gwp/publications/gender/gender-action-piece.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Grant, M., Hor, K., Bunthoeun, I., Soeters, S., and Willetts, J. (2021). Women Who Have a WASH Job Like Me Are Proud and Honoured: A Summary Brief on How Women Can Participate in and Benefit From Being Part of the Government WASH Workforce in Cambodia. Sydney, NSW. Available online at: waterforwomen.uts.edu.au (accessed March 22, 2023).

Grant, M., Huggett, C., Willets, J., and Wilbur, J. (2017). Gender Equality and Goal 6: The Critical Connection. Canberra, ACT. Available online at: https://waterpartnership.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Gender-Goal6-Critical-Connection.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Grant, M., Soeters, S., Bunthoeun, I. V. V., and Willetts, J. (2019). Rural piped-water enterprises in Cambodia: a pathway to women's empowerment? Water 11, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/w11122541

Greene, M. E., and Levack, A. (2010). Synchronizing Gender Strategies: A Cooperative Model for Improving Reproductive Health and Transforming Gender Relations. Available online at: https://www.igwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/synchronizing-gender-strategies.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Gupta, G. R. (2001). Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: the what, the why, and the how. SIECUS Rep. 29, 6–12.

Hannah, C., Giroux, S., Krell, N., Lopus, S. E., McCann, L. E., Zimmer, A., et al. (2021). Has the vision of a gender quota rule been realized for community-based water management committees in Kenya? World Dev. 137, 105154. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105154

Hannan, C. (2001). Gender Mainstreaming: Strategy for Promoting Gender Equality. Available online at: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/factsheet1.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Harvey, B., Cochrance, L., Czunyi, S., and Huang, Y. S. (2019). Learning, Landscape, and Opportunities for IDRC Climate Programming. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10625/57623 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Heijnen, E., and van Wijk-Sijbesma, C. (1993). Women, Water and Sanitation. Available online at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/202.1-93WO-12256.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Hulland, K. R. S., Chase, R. P., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Biswal, B., Sahoo, K. C., et al. (2015). Sanitation, stress, and life stage: a systematic data collection study among women in Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 10, e0141883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141883

ICRW Promundo (2007). Engaging Men and Boys to Achieve Gender Equality: How Can We Build on what We Have Learned? Available online at: https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Engaging-Men-and-Boys-to-Achieve-Gender-Equality-How-Can-We-Build-on-What-We-Have-Learned.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

iDE (2019). Understanding How Sanitation Sales Agent Gender Affects Key Sanitation Behaviors in Nepal. Available online at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/www.ideglobal.org/files/public/iDE-NP_WASHPaLS_AUG2019.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

iDE (2020). Success Story: An Equitable Business Is a Sustainable Business. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/news/cambodia-an-equitable-business-is-a-sustainable-business.aspx (accessed March 22, 2023).

Imburgia, L. (2019). Irrigation and equality: An integrative gender-analytical approach to water governance with examples from Ethiopia and Argentina. Water Alternat. 12, 571–584. Available online at: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol12/v12issue3/543-a12-2-26/file (accessed March 22, 2023).

Indarti, N., Rostiani, R., Megaw, T., and Willetts, J. (2019). Women's involvement in economic opportunities in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in Indonesia: examining personal experiences and potential for empowerment. Dev. Stud. Res. 6, 76–91. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2019.1604149

Ivens, S. (2008). Does increased water access empower women? Development 51, 63–67. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100458

JMP (2021). Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000-2020: Five Years Into the SDGs. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345081 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment. Dev. Change 30, 435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Kabeer, N., and Subramanian, R. (1996). Institutions, Relations and Outcomes: Framework and Tools for Gender-Aware Planning. Institute of Development Studies. Available online at: http://www.ids.ac.uk/files/Dp357.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Kar, K., and Chambers, R. (2008). Handbook on Community Lead Total Sanitation. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; Plan UK. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/872 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Khanna, R., Murthy, R., and Zaveri, S. (2016). “Gender transformative evaluations: principles and frameworks engendering evaluation,” in A Resource Pack on Gender Transformative Evaluations, eds S. Chigateri, and S. Saha (New Delhi Institute of Social Studies Trust), 16–37. Available online at: http://www.isstindia.org/publications/1465391379_pub_ISST_Resource_Pack_2016.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Leahy, C., Winterford, K., Nghiem, T., Kelleher, J., Leong, L., and Willetts, J. (2017). Transforming gender relations through water, sanitation, and hygiene programming and monitoring in Vietnam. Gend. Dev. 25, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331530

MacArthur, J. (2018). Reaching the Last Mile: Lessons and Learnings in the Sanitation Market In Rural Bangladesh. Available online at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/www.ideglobal.org/files/public/iDE-BAN-Tactic-Report-Last-Mile.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Davila, F., Grant, M., Megaw, T., Willetts, J., et al. (2022a). Gender-transformative approaches in international development: a brief history and five uniting principles. Womens. Stud. Int. Forum 95, 102635. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102635

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Koh, S., and Willetts, J. (2022b). Fostering the transformative potential of participatory photography: Insights from water and sanitation assessments. PLoS Water 1, e0000036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pwat.0000036

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Kozole, T., and Willetts, J. (2022c). Eliciting stories of gender- transformative change: investigating the effectiveness of question prompt formulations in qualitative gender assessments. Evaluation 28, 308–329. doi: 10.1177/13563890221105537

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., and Willetts, J. (2020). WASH and Gender: a critical review of the literature and implications for gender-transformative WASH research. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 10, 818–827. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2020.232

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., and Willetts, J. (2021). Exploring gendered change: concepts and trends in gender equality assessments. Third World Q. 42, 2189–2208. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1911636

Macura, B., Foggitt, E., Liera, C., Soto, A., Orlando, A., Del Duca, L., et al. (2023). Systematic mapping of gender equality and social inclusion in WASH interventions: knowledge clusters and gaps. BMJ Glob. Health 8, e010850. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010850

Mahon, T., Tripathy, A., and Singh, N. (2015). Putting the men into menstruation: the role of men and boys in community menstrual hygiene management. Waterlines 34, 7–14. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2015.002

Mandara, C. G., Niehof, A., and van der Horst, H. (2017). Women and rural water management: token representatives or paving the way to power? Water Alternat. 10, 116–133. Available online at: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue1/345-a10-1-7/file (accessed March 22, 2023).

March, C., Smyth, I., and Mukhopadhyay, M. (1999). A Guide to Gender-Analysis Frameworks. Oxfam. Available online at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/115397 (accessed March 22, 2023).

McDougall, C., Elias, M., and Mulema, A. A. (2021). The Potential and Unknowns of Gender Transformative Approaches. CGIAR: Gender Platform - Evidence Explainer, 1–3. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/114804 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Mommen, B., Humphries-Waa, K., and Gwavuya, S. (2017). Does women's participation in water committees affect management and water system performance in rural Vanuatu? Waterlines 36, 216–232. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.16-00026

Moore, M. L., Riddell, D., and Vocisano, D. (2015). Scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep: Strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. J. Corp. Citizensh. 58, 67–84. Available online at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A428874128/AONE?u=anon~77672f30&sid=googleScholar&xid=f6e0f606 (accessed March 22, 2023).

Moser, C. O. N. (1993). Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice and Training. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Mott, J., Brown, H., Kilsby, D., Eller, E., and Choden, T. (2021). Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Self-Assessment Tool, Water for Women Fund and Sanitation Learning Hub. doi: 10.19088/SLH.2021.016

Pederson, A., Greaves, L., and Poole, N. (2015). Gender-transformative health promotion for women: a framework for action. Health Promot. Int. 30, 140–150. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau083

Pommells, M., Schuster-Wallace, C., Watt, S., and Mulawa, Z. (2018). Gender violence as a water, sanitation, and hygiene risk: uncovering violence against women and girls as it pertains to poor WaSH access. Violence Against Women 24, 1851–1862. doi: 10.1177/1077801218754410

Rautanen, S.-L., and Baaniya, U. (2008). Technical work of women in Nepal's rural water supply and sanitation. Water Int .33, 202–213. doi: 10.1080/02508060802027687

Rottach, E., Schuler, S. R., and Hardee, K. (2009). Gender Perspectives Improve Reproductive Health Outcomes: New Evidence. Available online at: https://www.prb.org/resources/gender-perspectives-improve-reproductive-health-outcomes-new-evidence (accessed March 22, 2023).

Rutledge Shields, V., and Dervin, B. (1993). Sense-making in feminist social science research: a call to enlarge the methodological options of feminist studies. Womens. Stud. Int. Forum 16, 65–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-5395(93)90081-J

Sahoo, K. C., Hulland, K. R. S., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Freeman, M. C., Panigrahi, P., et al. (2015). Sanitation-related psychosocial stress: a grounded theory study of women across the life-course in Odisha, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 139, 80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.031

Sam, J.-M., and Todd, S. K. (2020). Women as hand pump technicians: empowering women and enhancing participation in rural water supply projects. Dev. Pract. 30, 357–368. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2019.1703904

Sehring, J., ter Horst, R., and Zwarteveen, M. (eds)., (2022). Gender Dynamics in Transboundary Water Governance Feminist Perspectives on Water Conflict and Cooperation. London: Routledge.

Singh, N., Åström, K., Hydén, H., and Wickenberg, P. (2008). Gender and water from a human rights perspective: The role of context in translating international norms into local action. Rural Soc. 18, 185–193. doi: 10.5172/rsj.351.18.3.185

Sinharoy, S. S., and Caruso, B. A. (2019). On World Water Day, gender equality and empowerment require attention. Lancet Planet Health 3, e202–e203. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30021-X

Soeters, S., Grant, M., Carrard, N., and Willetts, J. (2019). Intersectionality: Ask the Other Question. Available online at: waterforwomen.uts.edu.au (accessed March 22, 2023).

Soeters, S., Grant, M., Salinger, A., and Willetts, J. (2020). Gender Equality and Women in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Enterprises in Cambodia: Synthesis of Recent Studies. Sydney. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/learning-and-resources/resources/KL/2007-Cambodia-Enterprise-Synthesis.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Sommer, M., Ferron, S., Cavill, S., and House, S. (2015). Violence, gender and WASH: spurring action on a complex, under-documented and sensitive topic. Environ. Urban. 27, 105–116. doi: 10.1177/0956247814564528

Stanbury, P. (1984). Women's Role in Irrigated Agriculture: Report of the 1984 Diagnostic Workshop, Dahod Tank Irrigation Project, Madhya Pradesh, India. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University, Water Management Synthesis Project.

Sweetman, C., and Medland, L. (2017). Introduction: gender and water, sanitation and hygiene. Gend. Dev. 25, 153–166. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1349867

Taukobong, H. F. G., Kincaid, M. M., Levy, J. K., Bloom, S. S., Platt, J. L., Henry, S. K., et al. (2016). Does addressing gender inequalities and empowering women and girls improve health and development programme outcomes? Health Policy Plan. 31, 1492–1514. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw074

Udas, P. B., and Zwarteveen, M. Z. (2010). Can water professionals meet gender goals? A case study of the Department of Irrigation in Nepal. Gend. Dev. 18, 87–97. doi: 10.1080/13552071003600075

UNESCO (2000). Gender Equality and Equity: A Summary Review of UNESCO's Accomplishments Since the Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing 1995). Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000121145 (accessed March 22, 2023).

United Nations (1995). Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Available online at: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA~E.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

van Wijk-Sijbesma, C. (1985). Participation of Women in Water Supply and Sanitation: Roles And realities. Hague: IRC; UNDP. Available online at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/202.1-85PA-2977.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Van Wijk-Sijbesma, C. (1987). Drinking-water and sanitation: women can do much. World Health Forum 8, 28–33.

van Wijk-Sijbesma, C. (1998). Gender in Water Resources Management, Water Supply and Sanitation: Roles and Realities Revisited. Delft: IRC International Water and Sanitation Center. Available online at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/Wijk-1998-GenderTP33-text.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Visscher, J. T. (1982). Rural Water Supply Development: The Buba Tombali Water Project 1978–1981. Guinea-Bissau: IRC.

Water for Women (2019a). Do No Harm for Women's Empowerment in WASH Pilot. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/learning-and-resources/resources/GSI/WfW-DNH-learning-brief-final.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Water for Women (2019b). Towards Transformation: Water for Women Fund Strategy. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/learning-and-resources/resources/GSI/TT-Strategy-summary—Rev-1.pdf (accessed March 22, 2023).

Water for Women (2022a). Partnerships for Transformation: Guidance for WASH and Rights Holder Organisations. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/news/partnerships-for-transformation-guidance-for-wash-and-rights-holder-organisations.aspx (accessed March 22, 2023).

Water for Women (2022b). Shifting Social Norms for Transformative1 WASH: Guidance for WASH Actors. Available online at: https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/news/towards-transformation-shifting-social-norms-for-transformative-wash.aspx(accessed March 22, 2023).

WaterAid (2017). Practical Guidance to Address Gender Equality While Strengthening Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Systems. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/practical-guidance-gender-equality-strengthening-water-sanitation-hygiene-systems (accessed March 22, 2023).

Wellin, E. (1966). Directed cultural change and health programmes in Latin America. Millbank Mem. Fund Q. 44, 111–128. doi: 10.2307/3348982