94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Water, 01 February 2023

Sec. Water and Human Systems

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2023.1054182

This article is part of the Research TopicWorld Water Day 2022: Importance of WASH, Equal Access Opportunities, and WASH Resilience - A Social-Inclusion PerspectiveView all 12 articles

Access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are human rights and play a fundamental role in protecting health, which has been particularly evident during the SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) pandemic. People experiencing homelessness face frequent violations of their human rights to water and sanitation, negatively affecting their health and dignity and ability to protect themselves from COVID-19. This research aimed to identify barriers to safe water, sanitation and hygiene access for people experiencing homelessness in Mexico City during the COVID-19 pandemic. A survey of 101 respondents experiencing homelessness was conducted using mobile data collection tools in collaboration with El Caracol A.C., an NGO that contributes to the visibility and social inclusion of homeless people in Mexico. We report findings according to the following themes: general economic impacts of COVID-19; experiences with reduced access to WASH services due to COVID-19, challenges in accessing hand washing to follow COVID-19 public health advice; and coping mechanisms used to deal with reductions in access to WASH. We discuss the broader implications of the findings in terms of realization of the human rights to water and sanitation (HRtWS), and how people experiencing homelessness are left behind by the existing approaches to ensure universal access to water and sanitation under SDG 6.

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services are essential for a dignified and healthy life. This became even more evident with the SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) pandemic (Howard et al., 2020), as around 2.4 billion people continue to lack access to handwashing with soap and water (Brauer et al., 2020). In 2010, the human right to water and sanitation was recognized (United Nations General Assembly, 2010), and in 2015 sanitation was recognized as a standalone human right that “entitles everyone, without discrimination, to have physical and affordable access to sanitation, in all spheres of life, that is safe, hygienic, secure, socially and culturally acceptable and that provides privacy and ensures dignity” (United Nations General Assembly, 2016). Despite adoption of the human rights to water and sanitation, people experiencing homelessness (PEH) are frequently denied access to safe water and sanitation services, and face related discrimination, violence, and criminalization. Provision of water and sanitation services for PEH is often viewed as a form of charity rather than realization of human rights, which can reinforce inequalities and lead to the provision of low-quality services (Neves-silva et al., 2018).

Although homelessness is assumed to be linked to poor access to WASH, the experiences of PEH and their specific barriers to accessing water and sanitation have been under-researched (Ballard et al., 2022). Existing studies have examined WASH and homelessness in the contexts of rural Kentucky, United States (Ballard et al., 2022) and in urban settings in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Uddin et al., 2016), Belo Horizonte, Brazil (Neves-silva et al., 2018), and Delhi and Bangalore, India (Walters, 2014). There is limited evidence collected in a systematic way on a global level that addresses WASH and homelessness, as information on access to WASH services outside the household, schools, or health care facilities is sparse. Progress on PEH's access to safe water and sanitation is not effectively tracked as part of SDG 6, despite the focus on ensuring universal access and leaving no one behind. In Mexico, there is a lack of official data on some components of the human right to sanitation such as access to safely managed sanitation, especially for vulnerable populations (García-Searcy et al., 2022). Without policy targets or adequate collection of data, it is challenging to motivate decision-makers to act (Hugh and Fox, 2020). Further adding to these challenges is the fact that homelessness can be defined in different ways making it challenging to collect accurate and reliable data, let alone assign people to a category since people move in and out of homelessness and have heterogenous circumstances (Fowler et al., 2019). In Mexico, historical exclusion and invisibility of PEH have been exacerbated by the lack of information available and collected on this group and the criminalization of its members due to their life circumstances (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH)/El Caracol, 2019).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, residents in Mexico were instructed to maintain personal hygiene, stay at home and keep a safe physical distance to prevent the spread of COVID-19; a challenging task for those experiencing homelessness (Ruiz Coronel, 2021). A review of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in several low- and middle-income countries including Mexico indicated that PEH were among the most vulnerable groups impacted by COVID-19 lockdowns (Chackalackal et al., 2021). This is because COVID-19 public health recommendations put a large focus on hand hygiene, which requires ongoing access to safe water and soap. Closures of public spaces, businesses, and self-isolation in the context of COVID-19 further restricted opportunities for PEH to access safely managed water and sanitation services, creating new health challenges (Brauer et al., 2020).

The aim of this paper is to present findings on the barriers faced by PEH in Mexico City when attempting to access water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to contribute to a broader discussion about the operationalization of the human rights framework for the fulfillment of the human rights to water and sanitation for PEH.

People experiencing homelessness and precarious housing may have a range of different forms of insecure housing, ranging from living in temporary structures, temporarily with friends, housing without legal tenancy, to a complete absence of shelter, such as living in the streets (Amore et al., 2011). Piat et al. (2015) highlight the complexity of pathways into homelessness, including the interplay between structural factors such as lack of affordable housing, unsafe communities, and discrimination, and individual risk factors such as mental illness, childhood trauma and substance use. The failure to communicate the complex causes of homelessness has created a limited and biased narrative, that portrays PEH as lazy and dirty, and an individual issue disconnected from the broader societal context (Devereux, 2015). This has contributed to further discrimination toward PEH and on many occasions the criminalization of homeless individuals. For example, many cities in the US criminalize life sustaining behaviors of PEH such as public sleeping and laying or sitting down in certain areas of the city (Robinson, 2019). In Hungary in 2010 an anti-homeless campaign banned people from begging and picking up left over food from bins (Faragó et al., 2021). These anti-homeless laws have reinforced the negative perceptions of PEH among the public and authorities and lead to support for punitive policies (Turner et al., 2018).

In the case of Mexico City, there are an estimated 6,754 members of the street population, of which 4,354 live in public spaces while 2,400 live in one of the Social Assistance and Integration Centers (CAIS) (IASIS, 2017). However, due to stigmatization of this group, there is a significant undercounting (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH)/El Caracol, 2019). According to the “Censo de Poblaciones Callejeras 2017,” 87% were men and 13% were women, with women more likely to avoid rough sleeping because they are more prone to face sexual harassment, abuse, and violence (Bretherton and Nicholas, 2018). The lack of understanding of the complexity of homelessness and the paucity of information surrounding this group has affected the way in which PEH are addressed and represented in public policies and government programs in Mexico (Moreno et al., 2017). In the last few decades, government initiatives have promoted and operated paternalistic and isolated programs that focus on serving the immediate needs of PEH instead of creating policies that address the root cause of the problem, such as secure access to essential services like housing and healthcare (Guerra and Arjona, 2019). Such is the case with the most recent government programme “Comprehensive Care for Members of the Street Populations (PAIPIPC)” which aims is to provide immediate assistance to PEH through provision of blankets, clothing and food (CDHCM, 2021). On the other hand, Guerra and Arjona (2019) highlight that government programmes framed under a crime prevention scope reinforce prejudices related to the use of public space by PEH as a means to displace this group from their conventional locations. For instance, in Mexico City the “Ley de Cultura Civica” punishes those who use public space for sleeping at night or who undertake survival activities such as cleaning windshields with up to 36 h in jail and possible additional fines (CDHCM, 2021). When it comes to WASH services for PEH, the government does not guarantee access to drinking fountains, toilets, and showers although these services are essential for a life with dignity as established and protected under the Mexican Constitution (Guerra and Arjona, 2019).

Historically, access to public services such as water, sanitation and public health care among PEH has been constrained by their lower standing within social, economic, and cultural power structures (Quesada et al., 2011). In Mexico City homelessness frequently intersects with one or more characteristics like immigration status, health status, indigenous status, ethnicity, skin color, sex, age, disability, sexual preference, or gender identity to exacerbate exclusions (Guerra and Arjona, 2019). As a result, PEH have been subjected to various forms of discrimination, violence, and racism, which have constrained their choices and opportunities. For example, many PEH face numerous obstacles when trying to access medical care due to their physical appearance (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH)/El Caracol, 2019).

Due to these structural vulnerabilities, a deeper understanding of the complexity of homelessness and the intrinsic power relations in access to WASH services is needed by WASH researchers and practitioners. This will improve understanding of how realizing rights to safe WASH can best contribute to efforts to address drivers of homelessness and associated negative health and wellbeing outcomes across the spectrum of living situations. Addressing the WASH needs of this group is especially important as research shows that individuals who do not follow community hygiene norms, such as those related to sanitation and handwashing, are consistently stigmatized which exacerbates social and economic marginalization (Brewis et al., 2019).

On a global policy level, provision and monitoring of water and sanitation services are usually addressed at the household level, dismissing other spaces, such as public areas. For instance, the Joint Monitoring Programme that tracks WASH progress reports zero level of open defecation in urban areas in Mexico (WHO and UNICEF, 2022). However, overlooking certain underserved groups due to challenges with data collection from people living outside of typical households may lead to human rights violations that disproportionately affect PEH (Heller, 2019). A barrier to addressing WASH needs for PEH is the focus on technical solutions alone, such as the provision of drinking water and sanitation infrastructure as means to tackling inequalities. This practice fails to acknowledge the distinct reasons and constraints that drive people to undertake certain water and sanitation practices and discards cultural differences arising from gender, age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors (Peal et al., 2010; Coswosk et al., 2019). Additionally, access to WASH services is determined by the socio-cultural characteristics and power dynamics of a given location (Nunbogu and Elliott, 2021). Together these factors mediate people's ability to benefit from water services (Gimelli et al., 2018). For example, placement of hand-washing facilities in public places recommended by the WHO, such as in front of commercial buildings, may not be acceptable or accessible to PEH due to the power and social dynamics that control that space (Ballard and Caruso, 2021; Nunbogu and Elliott, 2021).

A handful of existing studies highlight some of the structural drivers and particular vulnerabilities of PEH in the context of WASH. Neves-Silva et al. (2019) found that in Belo Horizonte Brazil, not being able to access WASH increased discrimination and exclusion of PEH. For instance, a lack of facilities to wash menstrual materials meant that washing had to be done in public showers which contributed to a lack of privacy and dignity while also impacting health and personal security. In a study in Central Appalachian Kentucky, United States, researchers identified factors at multiple levels that created barriers to WASH access and use, such stigma, particularly among those who were drug users, as well as place-based characteristics such as long distance to businesses and facilities with WASH services related to lack of transport (Ballard et al., 2022). This study found that these factors not only limited people's ability to perform safe WASH practices but generated a feedback loop where unmeet WASH needs further exacerbated negative health outcomes, and further limited safe WASH access. Uddin et al. (2016) examined the experiences of PEH in accessing WASH in Dhaka, Bangladesh. They identified risks related to poor water quality provided by the Dhaka Water Supply Authority's open supply taps, and risks related to accessing those sources, particularly at night, that varied with gender and age. The authors argue that PEH's lack of access to water is due to their marginal position in society, and the associated unequal distribution of power and opportunities. Uddin and colleagues propose a rights-based approach to address the structural causes of discrimination and marginalization, rather than only addressing the symptoms underlying limited access to critical resources such as WASH.

Human rights-based approaches have been applied in a number of other WASH contexts to highlight challenges faced by vulnerable and marginalized groups in the realization of their rights to water and sanitation. For example, these efforts have sought to “make rights real” at a local level, establish the criteria against which the normative criteria of this right can be monitored, and draw attention to populations in vulnerable situations (Winkler et al., 2014; Giné-Garriga et al., 2017; Carrard et al., 2020). This framing is particularly relevant in the context of homelessness due to the interdependence and indivisibility of the HRtWS with other rights such as the rights to health and adequate housing (Uddin et al., 2016; Neves-Silva et al., 2019). The rest of the manuscript contributes to this growing understanding of barriers faced by PEH in realizing their human rights to safe WASH services.

This study was conducted in 3 municipalities, Cuauhtémoc, Venustiano Carranza, and Gustavo A. Madero, in Mexico City, Mexico, from February through April 2021. According to the latest street population census, these municipalities have the highest density of PEH (IASIS, 2017). Additionally, these are the areas in which El Caracol A.C. has been conducting activities for the past 10 years. El Caracol is a civil society organization that contributes to the visibility and social inclusion of homeless people in Mexico City through research, health campaigns and advocacy. El Caracol staff have a longstanding relationship with the PEH that live and work in the study area.

On March 24th, 2020, SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) was recognized as a serious priority disease by the Mexican government. The “Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia” (Healthy Distance Campaign) was then introduced to help mitigate the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The Healthy Distance campaign consisted of the interruption of any face-to face activity that involved a high concentration, transit, or movement of people, and included closures of private and public venues as well as the avoidance of public and crowded places and the compliance of the basic hygiene measure such as frequent hand washing (Ruiz Coronel, 2021). This meant that public spaces and private businesses had to remain closed or operate within limited hours and people had to stay at home until further notice. These unexpected and strict guidelines had a major impact on PEH, as most were left without a safe space to quarantine or access soap, face masks, and water, making it nearly impossible to follow such guidelines. As a response, El Caracol established a health and protection campaign for PEH. This campaign consisted of weekly support to PEH with basic water and sanitation supplies, education on preventive measures, procurement of safe spaces, and mental and physical health checks.

Prior to conducting research, ethical approval was obtained from the Stockholm Environment Institute Ethics Committee [2021-01-29-02]. Fact sheets describing the planned research were provided to potential participants describing the aims of the study and outlining the rights of respondents. These were handed out and read to potential participants before the start of each survey. Informed consent was obtained from participants through either a signature or a fingerprint in cases where the participant did not know how to write.

Data collection activities were guided by El Caracol's health and safety protocol to prevent the spread of COVID-19 to the target population and staff. The protocol consisted of staff limiting their activities to one visit per day to a group of PEH with a maximum stay of 45 min. One person was assigned to conduct the surveys. The surveys were conducted outside, and both the surveyor and the interviewee were required to wear a mask at all times. The interview was programmed to last between 15 and 20 min, and the surveyor could not lengthen the interaction.

The collection of data took place in 3 municipalities of Mexico City: Cuauhtémoc, Venustiano Carranza, and Gustavo A. Madero. The research participants comprised adult men and women, who at the time of the study were either living on the streets or in private or public shelter with no permanent form of housing. Using convenience sampling, 101 respondents were surveyed, leading to a total of 97 responses (67 = men and 29 = women and 1 with a person that did not wish to reveal their sex) after data cleaning to remove incomplete surveys. Recruitment of participants for the study was carried out by El Caracol during their daily street work activities and the safety and health campaign, however participation was not required in any way to benefit from these activities.

Additionally, 2 workers from El Caracol were selected for one-on-one key informant interviews that addressed questions related to the survey, including their perceptions of adversities that PEH faced when accessing water and sanitation services at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic; their perceptions of how PEH dealt with these adversities; their observations of violence and discrimination toward PEH from the local authorities and public; their views surrounding their health campaign that aimed to assist PEH during the pandemic as well as their perspectives surrounding the government's (in)action to protect and assist vulnerable groups at the height of the pandemic. The interviews were carried out online by the first author and lasted between 45 and 60 min.

The individual survey was designed in English and translated into Spanish. The survey questionnaire comprised both closed- and open- ended questions divided into seven sections. The first two sections collected information on descriptive characteristics of the target population, such as sex, marital status, education level, occupation, working status, income before and during the COVID-19, health insurance, and sleeping conditions. The third section covered access and use of water, sanitation, and hygiene services before and during the pandemic.

Before implementing the survey, the questionnaire was tested among the enumerators and other workers from El Caracol allowing them to build confidence and clarify any cultural or language misinterpretations. Survey responses were collected with mobile data collection using cellphones and the survey platform Kobo Toolbox.

The dataset was downloaded from Kobo Toolbox in an XSL format. The first author used Microsoft Excel for data management, organization, and initial analysis. After data cleaning to remove incomplete responses, 97 respondents were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis were generated using SAS University Edition software package. Interview transcripts were analyzed using deductive thematic analysis based on the main survey themes.

Of the 97 participants, 87 (90%) had some type of formal education, with 22 (25%) having graduated from or attended high school and 33 (38%) stating that they had attended or completed junior high school.

Regarding employment, 63 (65%) of the 97 participants said that they were employed in some capacity both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; all jobs reported were informal with some of the most common jobs reported being windshield cleaners (n = 24; 38%), street sellers (n = 15; 23%), and waste collectors (n = 15; 16%) (Table 1).

When asked about their sleeping conditions, most of the respondents (n = 70; 72%) said that they had slept in the street during the last month, while a small number of respondents indicated that they had slept at a rental space 9 (9%), family's house 5 (5%), friend's house 3 (3%) or government hostel 3 (3%).

Overall, the most frequently mentioned impact reported by respondents was through reduced work opportunities (n = 37; 45%) and reduction of income (n = 31; 37%), highlighting negative socio-economic impacts for many (respondents selected as many responses as applicable). Of the 63 participants that worked before and during the pandemic, the vast majority (87%) noted that their income had been negatively affected (Figure 1). Respondents felt these changes were mainly a result of the lack of job opportunities, closure of private businesses, and the low number of people on the streets.

Further, the housing situation of respondents was negatively impacted by COVID-19. Of the 83 respondents that noted COVID-19 had negatively impacted some aspects of their life, 13 participants (16%) mentioned they had started to live in the streets, 9 participants (11%) stated they had been evicted from their place of residence and 8 participants (10%) noted that they had gone back to living in the streets during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of gendered impacts, one El Caracol interviewee reported women faced disproportionately more difficulties than men during the COVID-19 pandemic:

“Women had to go out and look for food and water while still taking care of the children. Many times, they were left to educate, entertain, and feed their families without any resources.”

Additionally, some women respondents reported a rise in domestic violence as a consequence of COVID-19 (n = 3; 4%).

Survey participants reported that their main drinking water source was purchased bottled water (n = 36; 37%) and water points in private businesses (n = 25; 26%), the latter not always being available. In terms of affordability, 32 (33%) participants reported spending no money on drinking water daily while others reported spending between 1 and 15 Mexican pesos (n = 33; 34%) and 16–30 Mexican pesos (n = 21; 22%) daily on drinking water. According to the interviewees, those who are parents must also look after the water and sanitation expenses of children, and in many cases those of elder family and friends.

Of the total respondents, 35 (36%) reported using a different drinking water source before the COVID-19 pandemic. Of these, 12 (34%) noted that the water from the new source was of worse quality, further away (n = 7; 20%), or more expensive (n = 4; 11%) (Table 2). Respondents stated that some of the coping mechanisms adopted to deal with these changes were drinking less water than needed (n = 15; 43%), drinking other liquids such as soda, juice, or milk (n = 8; 22%) and storing drinking water in barrels (n = 8; 23%).

Table 2. Reported changes in water sources with the pandemic (36 respondents and total number of responses = 42).

When asked about hand washing and hygiene, 48 (49%) respondents noted that their hand washing facility was the same as their drinking water source. Of these respondents, 15 (31%) respondents stated using bottled water as their main drinking water as well as hand washing source. Of the 49 (51%) respondents who used a different source for washing their hands, 18 (37%) noted that water was not always available at this source. When asked about soap availability at the hand washing facility or surrounding area, 55 (57%) respondents reported having to bring soap to the hand washing facility.

In terms of hand-washing advice respondents received on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19, most of the respondents (n = 60; 62%) had either heard protection measures on the TV (n = 31; 50%) or radio (n = 24; 39%) or had been told by family members (n = 11;18%) or civil society organizations (n = 9; 15%) that regular hand washing with soap and water was one of the best ways to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 (n = 33; 52%). All these respondents reported trying to follow this advice, despite not always having access to a reliable handwashing facility with water and soap.

Three types of sanitation facilities were found to be most commonly used among survey respondents: a toilet in a current living space (25%), a toilet in a public parking lot (23%), and a toilet in a private business or restaurant (16%). Open defection was a common practice among survey respondents with 19 respondents (20%) stating that they practiced open defecation daily. Of the respondents that reported practicing open defecation, 9 participants (9%) mentioned that they previously used a toilet either in the place that they used to live or in a private business before the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of cost for using a sanitation facility, respondents reported spending between 1 and 5 Mexican pesos (n = 24; 25%), 6–10 Mexican pesos (n = 15; 15%), and 11–15 Mexican pesos (n = 11; 11%) per day for use of the sanitation facility, while 36 (36%) of the respondents reported not spending any money on using a sanitation facility. When asked about accessibility of sanitation facilities respondents stated that they could always (58%), almost always (12%), sometimes (12%), and almost never enter the facilities (1%). Reasons for not always being able to access the sanitation facilities included lack of money (n = 9; 36%), physical appearance of the person (n = 6; 24%) and the facility being closed (n = 3; 12%).

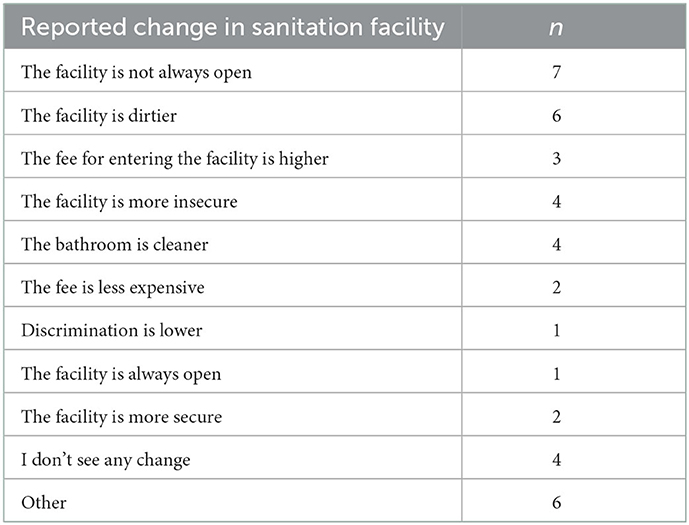

Less than half of the survey respondents (n = 33; 34%) reported using a different sanitation facility prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of these, respondents (n = 23; 70%) reported that the conditions of the new sanitation facility were worse than the ones from the previous facility, stating that the new facilities are not always open (n = 7; 30%), they were dirtier (n = 6; 26%), more insecure (n = 4; 17%) and more expensive (n = 3; 13%) (Table 3). Some of the coping mechanisms used by the respondents to deal with these changes were drinking or eating less to avoid having to use the sanitation facilities so often (n = 7; 21%), holding urine/feces for longer than wanted (n = 2; 6%), and practicing open defecation (n = 1; 3%). Of the 29 women surveyed, 5 participants (17%) stated that they did not have access to a private space in which to manage their menstrual health needs or wash themselves. Of these respondents, 2 practiced open defecation, 1 used the toilet in the metro station, 1 reported using the toilet in a private business and 1 used the toilet in the shelter.

Table 3. Reported changes in sanitation facility with the pandemic (33 respondents, total number of responses = 40).

One key informant interviewee noted that they had received complaints from other civil society organizations, at the height of the pandemic, about the increase of human feces around the area in which they work:

“The priest from the church was angry about the fact that every morning he would find several human feces in the surroundings of the church. He came to tell me this as a complaint, but there is nothing I can do about it.”

Previous experience of physical and verbal violence while using the toilet, practicing open defecation, or fetching water was reported by 29 (30%) of the respondents, with 16 (55%) reporting that they had suffered some type of violence while practicing open defecation. The most common forms of aggression noted among the participants were verbal violence (n = 14; 48%), intimidation (n = 8; 28%), and physical violence (n = 6; 20%). Although the survey did not ask respondents to specify whether the timing of these experiences was before or after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one key informant interviewee reported a perceived increase in discrimination and violence against the homeless population during the COVID-19 pandemic stating:

“The police became more aggressive towards people experiencing homelessness, it almost felt like the virus was a justification for such attitudes.”

This study investigated barriers to accessing safe WASH among people experiencing homelessness in Mexico City during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is no doubt that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, PEH faced a number of challenges characterized by structural vulnerability, such as poor access to public health services, malnutrition, a lack of awareness of psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, early chronic morbidity, and shorter life spans (Ruiz Coronel, 2020). Furthermore, many respondents reported poor WASH services prior to the pandemic.

Our findings indicate that COVID-19 lock-downs exacerbated the challenges faced by PEH in accessing WASH services and securing their human rights to water and sanitation. For instance, we found an increase in open defecation, which was likely a result of the closure of public spaces and businesses as well as evictions. A lack of financial resources was one reason PEH were not always able to access a sanitation facility. Similarly, a study carried out in Bangladesh found that PEH reported using sanitation facilities less often than needed, and hence practiced more open defecation, due to the costly entry fee of the facilities (Uddin et al., 2016). This study also highlights that due to a lack of action taken by authorities, both at the local and national scale, PEH participants in this study are in general left to rely on private businesses to informally meet human rights to water and sanitation in Mexico City. Similarly, a study by Rodriguez et al. (2022) showed that closure of public spaces and restricted access to regular services such as toilets and shower rooms, hampered PEH's ability to meet their most basic needs. Other research on open defecation shows that while open defecation is often considered a public health risk, it also has safety and dignity implications and can cause long-term negative effects on the psychosocial wellbeing of individuals engaged in these practices (Saleem et al., 2019). Girls and women are particularly at risk of verbal, physical and sexual abuse when practicing open defecation or managing menstruation in public spaces (Cherian and Sahu, 2016). Viewed in this way, open defecation is not just a violation of the human right to sanitation, but also gender discrimination and an infringement on human dignity (Saleem et al., 2019).

In the case of hand washing, which has been a central pillar of COVID-19 prevention, many of the respondents in the study reported not having reliable access to a handwashing station with water and soap. This finding conflicts with public health recommendations to wash hands with soap and water as frequently as possible to prevent disease transmission. In the study of Brauer et al. (2020) undertaken in the US, some of the barriers to handwashing among PEH during the COVID-19 pandemic were a surge in prices of hygiene supplies such as soap and sanitizer, and the lack of financial means for PEH to obtain such resources. In our study we found that PEH would need to bring their own soap to the handwashing facility in order to wash their hands, which could prevent many from adhering to health and safety measures. Many reported using bottled water as their main drinking and handwashing source, which, compounded by the fact that many PEH had lost their job or normal earnings during the pandemic, created an additional economic burden on top of existing economic constraints.

Bottled water consumption is a widespread practice in Mexico, owing to a variety of factors, including lack of institutional and regulatory frameworks and poor water infrastructure that discourage people from drinking water straight from the tap (Pacheco-Vega, 2019). The findings of our study support this assertion and demonstrate that, even during non-COVID times, this practice places a significant financial burden on PEH, with the cost of purchasing bottled water daily potentially accounting for up to 15% of respondents' monthly income. In the US, a study conducted in a homeless shelter showed that people preferred drinking bottled water even if the price was significantly higher than tap water (DeMyers et al., 2017). In addition to this, some respondents in our study mentioned drinking sugar sweetened beverages (SSB) such as juice, milk, or soda instead of water as coping mechanism to deal with the difficulties in accessing their usual drinking water source. Similarly, in the US, a study on youth in a rural southwestern context showed that the preference for SSB increased for those who lacked access to safe drinking water (Hess et al., 2019). Further research is needed to fully assess the economic and health impact of purchasing water bottled and SSBs on PEH and other groups in vulnerable situations.

The coping strategies employed by respondents further underscore how authorities neglected consideration of PEH in Mexico when developing COVID-19 preventative measures, which were found to create new daily challenges for the participants in this research. Some studies on PEH found an increase in loneliness and substance abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic (Tucker et al., 2020; Bertram et al., 2021). However, there is limited evidence on how the lack of access to essential services such as toilets and water points during the COVID-19 pandemic affected PEH's physical and mental health. As Perri et al. (2020) suggest, added stress as a result of the limited access to essential resources and services could lead to a decline in the mental and physical health of PEH and increase their risk of alcohol and drug use, emphasizing an important area for further consideration. In addition, limited access to WASH facilities can pose challenges for women and all those who menstruate to take care of their menstrual needs in a private and dignified matter (Teizazu et al., 2021). In our study, some women reported not having access to a private space in which to take care of their menstrual needs. Likewise, a study in New York City, US, found that during the COVID-19 pandemic women had to pass as someone who was not homeless to gain access to a toilet inside a restaurant for managing menstruation (Sommer et al., 2020).

Ensuring universal access for all people, as outlined in SDG 6.1 and 6.2, means it is imperative to take actions to ensure marginalized groups benefit from safe WASH. In this way the human rights framework can provide a powerful tool to highlight these needs and enable more inclusive delivery of WASH services (Carrard et al., 2020). The findings in this study show that many people experiencing homelessness in Mexico City do not have their HRtWS fulfilled, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this unjust situation. This also has implications for realizing other human rights, such as the right to health and housing. Further, the inability to easily access water and sanitation services limits the already constrained autonomy and freedom of people experiencing homelessness, and their ability to improve their living conditions (Neves-Silva et al., 2020).

A common challenge to applying a human rights perspective in the water and sanitation sector is the lack of operationalization of human rights by local governments and service providers, which is the case in Mexico City. People experiencing homelessness are often left out of public policies or state funded programmes, and this omission is often purposeful in both the planning and the implementation of programmes, which prolongs inequalities in a cycle of increasing marginalization (Busch-Geertsema et al., 2010; Ruiz Coronel, 2020). In Brazil, Neves-silva et al. (2018), found that providing access to WASH services was seen as a form of charity and not as realization of human rights, which has prevented the government from taking action to fulfill the HRtWS. In addition, the criminalization of people experiencing homelessness has on many occasions justified the lack of action from the government to provide public services such as water and sanitation (Guerra and Arjona, 2019). There are further policy barriers, such as the coexistence of the HRtWS with other laws and policies that may not favor these human rights and thus impede their fulfillment (Brown et al., 2016). Furthermore, the realization of the human right to water has been affected by the push for commodification and privatization of water, whereas pricing and affordability are elements that are deemed inseparable from the recognition of the right as means to compensate for water scarcity (Cullet, 2019). As Pacheco-Vega (2019) argues the production of bottled water represents a process of commercialization and commodification of the human right to water in Mexico.

In light of these challenges there is a need for greater accountability for WASH duty bearers when the HRtWS is not realized (Dickin et al., 2022; Hepworth et al., 2022) as well as supporting empowerment of marginalized groups to claim their rights. To address some of these challenges on a local level Carrard et al. (2020) describe a “make rights real” approach to make the human rights to water and sanitation relevant and helpful for local government. This approach seeks to achieve transformational change in local government officials in terms of greater awareness, intrinsic motivation, and operationalization of the human rights principles and standards, and has been used in 12 countries so far. Furthermore, this study highlights a need for WASH practitioners to work with actors in other sectors such as those working to ensure adequate housing. Improved understanding of how WASH insecurity varies across the full spectrum of housing exclusion and homelessness, beyond times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, requires further attention to better target interventions.

While the HRtWS is a good starting point for addressing inequalities among PEH, it does not fully encompass all the ways that people use water (Mehta, 2014; Jepson et al., 2017; Neves-Silva et al., 2019). There is often a focus on drinking water, while adequate water for personal hygiene such as for showers and laundry is neglected as part of one's human right. In addition, there is a need to better understand the different ways that people use water beyond material and domestic uses, such as water for cultural purposes and income generation. Researchers have suggested that the capabilities framing extends the HRtWS to include these other ways that people use water (Wutich et al., 2017), and could provide a valuable framework for future research to further elucidate WASH inequalities among PEH.

First, the convenience sampling approach might have missed certain groups such as indigenous populations who experience homelessness, women who look after children and other family members, and men and women living in high-risk municipalities of Mexico City such as Iztapalapa and Coyoacan. Second, due to time constraints with COVID-19, the sample size for the study was small, and the research team was unable to collect more in-depth lived experiences through other methods such as one-on-one interviews, participatory photography, or go along interviews to describe WASH facilities. In the future the use of participatory photography could provide a better understanding of use of water beyond material and domestic uses and help identify and meaningfully address inequalities in WASH service provision (MacArthur et al., 2022).

We identified barriers to use of safe WASH services among people experiencing homelessness in Mexico City, and how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges. Many respondents used informal water and sanitation facilities, such as private businesses, rather than having their human rights met by rights duty bearers such as local authorities. Respondents who experienced reduced access to WASH services due to COVID-19 used a range of coping mechanisms, such as using water of poorer quality or practicing open defecation. Barriers to accessing handwashing facilities was a particular challenge due to COVID-19 public health messaging. This study contributes to a growing body of research examining WASH barriers in the context of people experiencing homelessness. We highlight the importance of greater evidence collection to understand the needs of this vulnerable group to ensure they are not overlooked by policy-makers in Mexico City and in other urban areas. Finally, we describe the potential applications and limitations of the human rights framework in this context, including a need to better operationalize the WASH needs of PEH and important links to other human rights, such as health and housing, for WASH practitioners to consider.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Stockholm Environment Institute Ethics Committee [2021-01-29-02]. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency through a Sustainable Sanitation Initiative Subgrant on COVID-19 impacts at the Stockholm Environment Institute.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the support and dedication of El Caracol A.C. as well as all the people that live and survive in the streets. May this work be a step toward a dignified life for all.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Amore, K., Baker, M., and Howden-Chapman, P. (2011). The ETHOS definition and classification of homelessness: An analysis. Euro. J. Homelessness. 5, 19–37. Available online at: https://www.feantsa.org/download/article-1-33278065727831823087.pdf

Ballard, A. M., and Caruso, B. A. (2021). Public handwashing for basic hygiene in people experiencing homelessness. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e763. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00283-7

Ballard, A. M., Cooper, H. L. F., Young, A. M., and Caruso, B. A. (2022). You feel how you look: exploring the impacts of unmet water, sanitation, and hygiene needs among rural people experiencing homelessness and their intersection with drug use. PLOS Water 1, e0000019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pwat.0000019

Bertram, F., Heinrich, F., Fröb, D., Wulff, B., Ondruschka, B., Püschel, K., et al. (2021). Loneliness among homeless individuals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 3035. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063035

Brauer, M., Zhao, J. T., Bennitt, F. B., and Stanaway, J. D. (2020). Global access to handwashing: implications for COVID-19 control in low-income countries. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 057005. doi: 10.1289/EHP7200

Bretherton, J., and Nicholas, P. (2018). Women and Rough Sleeping: A Critical Review of Current Research and Methodology. Centre for Housing Policy, University of York, York, United Kingdom. p. 38. Available online at: https://www.mungos.org/app/uploads/2018/10/Women-and-Rough-Sleeping-Report-2018.pdf

Brewis, A., Wutich, A., du Bray, M. V., Maupin, J., Schuster, R. C., and Gervais, M. M. (2019). Community hygiene norm violators are consistently stigmatized: Evidence from four global sites and implications for sanitation interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 220, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.020

Brown, C., Neves-Silva, P., and Heller, L. (2016). The human right to water and sanitation: a new perspective for public policies. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 21, 661–670. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015213.20142015

Busch-Geertsema, V., Edgar, W., O'Sullivan, E., and Pleace, N. (2010). Homelessness and Homeless Policies in Europe: Lessons from Research. European Commission. Available online at: http://noticiaspsh.org/IMG/pdf/4099_Homeless_Policies_Europe_Lessons_Research_EN.pdf

Carrard, N., Neumeyer, H., Pati, B. K., Siddique, S., Choden, T., Abraham, T., et al. (2020). Designing human rights for duty bearers: making the human rights to water and sanitation part of everyday practice at the local government level. Water 12, 378. doi: 10.3390/w12020378

CDHCM (2021). Informe especial. Situación de los derechos humanos de las poblaciones callejeras. Comision Nacional de los Derechos Humanos de la Ciudad de Mexico. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/ComisionderechoshumanosCiudadMexico.docx

Chackalackal, D. J., Al-Aghbari, A. A., Jang, S. Y., Ramirez, T. R., Vincent, J., Joshi, A., et al. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries, who carries the burden? Review of mass media and publications from six countries. Pathog. Glob. Health 115, 178–187. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2021.1878446

Cherian, V., and Sahu, M. (2016). Open defecation: A menace to health and dignity. Indian J. Public Health Develop. 7, 85–87. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2016.00195.9

Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDH)/El Caracol. (2019). Diagnóstico sobre las condiciones de vida, el ejercicio de los derechos humanos y las políticas públicas disponibles para mujeres que constituyen la población callejera. México: CNDH.

Coswosk, É. D., Neves-Silva, P., Modena, C. M., and Heller, L. (2019). Having a toilet is not enough: the limitations in fulfilling the human rights to water and sanitation in a municipal school in Bahia, Brazil. BMC Public Health 19, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6469-y

Cullet, P. (2019). The Human Right to Water: A Testing Ground for Neoliberal Policies in: Human Rights in India. 1st ed. Routledge. pp. 253–271.

DeMyers, C., Warpinski, C., and Wutich, A. (2017). Urban water insecurity: a case study of homelessness in Phoenix, Arizona. Environ. Justice 10, 72–80. doi: 10.1089/env.2016.0043

Devereux, E. (2015). Thinking outside the charity box: Media coverage of homelessness. Euro. J. Homelessness. 9, 261–273. Available online at: https://www.feantsaresearch.org/download/devereuxejh2-2015article11259989678303316558.pdf

Dickin, S., Syed, A., Qowamuna, N., Njoroge, G., Liera, C., Al'Afghani, M. M., et al. (2022). Assessing mutual accountability to strengthen national WASH systems and achieve the SDG targets for water and sanitation. H2Open J. 5, 166–179. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2022.032

Faragó, L., Ferenczy, D., Kende, A., Kreko, P., and Gurály, Z. (2021). Criminalization as a justification for violence against the homeless in Hungary. J. Soc. Psychol. 162, 216–230. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2021.1874257

Fowler, P. J., Hovmand, P. S., Marcal, K. E., and Das, S. (2019). Solving homelessness from a complex systems perspective: insights for prevention responses. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40, 465–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013553

García-Searcy, V., Villada-Canela, M., Arredondo-García, M. C., Anglés-Hernández, M., Pelayo-Torres, M. C., and Daesslé, L. W. (2022). Sanitation in Mexico: an overview of its realization as a human right. Sustainability 14, 2707. doi: 10.3390/su14052707

Gimelli, F. M., Bos, J. J., and Rogers, B. C. (2018). Fostering equity and wellbeing through water: A reinterpretation of the goal of securing access. World Develop. 104, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.10.033

Giné-Garriga, R., Flores-Baquero, Ó., Jiménez-Fdez de Palencia, A., and Pérez-Foguet, A. (2017). Monitoring sanitation and hygiene in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: a review through the lens of human rights. Sci. Total Environ. 580, 1108–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.066

Guerra, M., and Arjona, J. C. (2019). Personas en situación de calle: excluidas de los excluidos. En Personas en situación de calle. Serie de inclusión, derechos humanos y construcción de ciudadanía. México: Instituto Electoral de la Ciudad de México. p. 41–64.

Heller, L. (2019). Human Rights to Water and Sanitation in Spheres of Life Beyond the Household With An Emphasis on Public Spaces: (Forty-Second Session). Human Rights Council. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3823889

Hepworth, N. D., Brewer, T., Brown, B. D., Atela, M., Katomero, J., Kones, J., et al. (2022). Accountability and advocacy interventions in the water sector: a global evidence review. H2Open J. 5, 307–322. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2022.062

Hess, J. M., Lilo, E. A., Cruz, T. H., and Davis, S. M. (2019). Perceptions of water and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption habits among teens, parents and teachers in the rural Southwestern United States. Public Health Nutr. 22, 1376–1387. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019000272

Howard, G., Bartram, J., Brocklehurst, C., Colford, J. M., Costa, F., Cunliffe, D., et al. (2020). COVID-19: urgent actions, critical reflections and future relevance of “WaSH”: lessons for the current and future pandemics. J. Water Health 18, 613–630. doi: 10.2166/wh.2020.162

Hugh, S., and Fox, M. S. (2020). “Homelessness and open city data: addressing a global challenge, in Open Cities | Open Data: Collaborative Cities in the Information Era, eds S. Hawken, H. Han, and C. Pettit, C (Springer: Singapore), 29–55.

IASIS. (2017). Resultados preliminares del Censo de Poblaciones Callejeras 2017, iasis en colaboración con organizaciones civiles, expertos y academia. Available online at: http://189.240.34.179/Transparencia_sedeso/wp-content/uploads/2017/Preeliminares.pdf

Jepson, W., Budds, J., Eichelberger, L., Harris, L., Norman, E., O'Reilly, K., et al. (2017). Advancing human capabilities for water security: a relational approach. Water Secur. 1, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.wasec.2017.07.001

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Koh, S., and Willetts, J. (2022). Fostering the transformative potential of participatory photography: insights from water and sanitation assessments. PLOS Water 1, e0000036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pwat.0000036

Mehta, L. (2014). Water and human development. World Dev. 59, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.12.018

Moreno, A., Soriano, A., and Martinez, M. (2017). Condiciones de Vida Material e Inmaterial. Mujeres integrantes de las poblaciones callejeras en la Ciudad de México. Available online at: https://revistainclusiones.org/pdf51/8%20VOL%205%20NUM%204%202018UNAMCOLOQUIOCTUBREDICIEMBRERV%20INClu.pdf (accessed March 7, 2022).

Neves-Silva, P., Lopes, J. A. O., and Heller, L. (2020). The right to water: impact on the quality of life of rural workers in a settlement of the landless workers movement, Brazil. PLoS ONE 15, e0236281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236281

Neves-silva, P., Martins, G. I., and Heller, L. (2018). “We only have access as a favor, don't we?” The perception of homeless population on the human rights to water and sanitation. A gente tem acesso de favores, né?. A percepção de pessoas em situação de rua sobre os direitos humanos à água e ao esgotamento sanitário. Cadernos de saude publica. 34, e00024017. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00024017

Neves-Silva, P., Martins, G. I., and Heller, L. (2019). Human rights' interdependence and indivisibility: a glance over the human rights to water and sanitation. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 19, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12914-019-0197-3

Nunbogu, A. M., and Elliott, S. J. (2021). Towards an integrated theoretical framework for understanding water insecurity and gender-based violence in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). Health Place 71, 102651. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102651

Pacheco-Vega, R. (2019). “Human right to water and bottled water consumption: governing at the intersection of water justice, rights, and ethics,” in Water Politics. Governance, Rights and Justice, eds Farhana Sultana and Alex Loftus (London, Routledge), 113-128.

Peal, A., Evans, B., and Voorden, C. (2010). Hygiene and Sanitation Software: An Overview of Approaches. Geneva: Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council.

Perri, M., Dosani, N., and Hwang, S. W. (2020). COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: challenges and mitigation strategies. CMAJ 192, E716–E719. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200834

Piat, M., Polvere, L., Kirst, M., Voronka, J., Zabkiewicz, D., Plante, M.-C., et al. (2015). Pathways into homelessness: understanding how both individual and structural factors contribute to and sustain homelessness in Canada. Urban Stud. 52, 2366–2382. doi: 10.1177/0042098014548138

Quesada, J., Hart, L. K., and Bourgois, P. (2011). Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med. Anthropol. 30, 339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725

Robinson, T. (2019). No right to rest: police enforcement patterns and quality of life consequences of the criminalization of homelessness. Urban Affairs Rev. 55, 41–73. doi: 10.1177/1078087417690833

Rodriguez, N. M., Martinez, R. G., Ziolkowski, R., Tolliver, C., Young, H., and Ruiz, Y. (2022). “COVID knocked me straight into the dirt”: perspectives from people experiencing homelessness on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 22, 1327. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13748-y

Ruiz Coronel, A. (2020). En la calle no hay cuarentena. Lecciones de la pandemia que visibilizó a las personas en situación de calle. Available online at: https://www.comecso.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Covid-11-Ruiz.pdf (accessed October 25, 2022).

Saleem, M., Burdett, T., and Heaslip, V. (2019). Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 19, 158. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6423-z

Sommer, M., Gruer, C., Smith, R. C., Maroko, A., and Kim, H. (2020). Menstruation and homelessness: challenges faced living in shelters and on the street in New York City. Health Place 66, 102431. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102431

Teizazu, H., Sommer, M., Gruer, C., Giffen, D., Davis, L., Frumin, R., et al. (2021). “Do we not bleed?” sanitation, menstrual management, and homelessness in the time of COVID. Columbia J. Gend. Law 41, 208–217. doi: 10.52214/cjgl.v41i1.8838

Tucker, J. S., D'Amico, E. J., Pedersen, E. R., Garvey, R., Rodriguez, A., and Klein, D. J. (2020). Behavioral health and service usage during the COVID-19 pandemic among emerging adults currently or recently experiencing homelessness. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.013

Turner, M., Funge, S., and Gabbard, W. (2018). Victimization of the homeless: public perceptions, public policies, and implications for social work practice. J. Soc. Work Global Commun. 3, 1–12. doi: 10.5590/JSWGC.2018.03.1.01

Uddin, S. M. N., Walters, V., Gaillard, J. C., Hridi, S. M., and McSherry, A. (2016). Water, sanitation and hygiene for homeless people. J. Water Health 14, 47–51. doi: 10.2166/wh.2015.248

United Nations General Assembly. (2010). Human Right to Water and Sanitation. UN Document A/RES/64/292. Geneva: UNGA.

United Nations General Assembly. (2016). The Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly. UN Document A/RES/70/169. UNGA.

Walters, V. (2014). Urban homelessness and the right to water and sanitation: experiences from India's cities. Water Policy 16, 755–772. doi: 10.2166/wp.2014.164

WHO UNICEF (2022). Sanitation Data Mexico Household Level. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Available online at: https://washdata.org/data/household#!/ (accessed September 14, 2022).

Winkler, I. T., Satterthwaite, M. L., and De Albuquerque, C. (2014). Treasuring what we measure and measuring what we treasure: post-2015 monitoring for the promotion of equality in the water, sanitation, and hygiene sector. Wis. Int'l L. J. 32, 547.

Wutich, A., Budds, J., Eichelberger, L., Geere, J., Harris, L., Horney, J., et al. (2017). Advancing methods for research on household water insecurity: studying entitlements and capabilities, socio-cultural dynamics, and political processes, institutions and governance. Water Secur. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.wasec.2017.09.001

Keywords: human rights to water and sanitation, WASH, COVID-19, homelessness, Mexico City, human rights-based approach, water, sanitation

Citation: Liera C, Dickin S, Rishworth A, Bisung E, Moreno A and Elliott SJ (2023) Human rights, COVID-19, and barriers to safe water and sanitation among people experiencing homelessness in Mexico City. Front. Water 5:1054182. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2023.1054182

Received: 26 September 2022; Accepted: 09 January 2023;

Published: 01 February 2023.

Edited by:

Jane Wilbur, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Aviram Sharma, Nalanda University, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Liera, Dickin, Rishworth, Bisung, Moreno and Elliott. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carla Liera,  Y2FybGEubGllcmFAc2VpLm9yZw==

Y2FybGEubGllcmFAc2VpLm9yZw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.