94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Water, 23 September 2022

Sec. Water and Human Systems

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2022.983789

This article is part of the Research TopicWorld Water Day 2022: Importance of WASH, Equal Access Opportunities, and WASH Resilience - A Social-Inclusion PerspectiveView all 12 articles

Introduction: Women and girls with disabilities may be excluded from efforts to achieve menstrual health during emergencies. The review objectives were to (1) identify and map the scope of available evidence on the inclusion of disability in menstrual health during emergencies and (2) understand its focus in comparison to menstrual health for people without disabilities in emergencies.

Methods: Eligible papers covered all regions and emergencies. Peer-reviewed papers were identified by conducting searches, in February 2020 and August 2021, across six online databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health, ReliefWeb, and Cinahal Plus); gray literature was identified through OpenGrey, Gray Literature Report, Google Scholar, and Million Short. Eligible papers included data on menstrual health for women and girls with and without disabilities in emergencies.

Results: Fifty-one papers were included; most focused on Southern Asia and man-made hazards. Nineteen papers contained primary research, whilst 32 did not. Four of the former were published in peer-reviewed journals; 34 papers were high quality. Only 26 papers mentioned menstrual health and disability in humanitarian settings, but the discussion was fleeting and incredibly light. Social support, behavioral expectations, knowledge, housing, shelter, water and sanitation infrastructure, disposal facilities, menstrual material availability, and affordability were investigated. Women and girls with disabilities rarely participated in menstrual health efforts, experienced reduced social support, and were less able to access water, sanitation and hygiene facilities, including disposal facilities. Cash transfers and hygiene kit distribution points were often inaccessible for people with disabilities; few outreach schemes existed. Hygiene kits provided were not always appropriate for people with disabilities. Caregivers (all genders) require but lack guidance about how to support an individual with disabilities to manage menstruation.

Conclusion: Minimal evidence exists on menstrual health and disabilities in emergencies; what does exist rarely directly involves women and girls with disabilities or their caregivers. Deliberate action must be taken to generate data about their menstrual health requirements during humanitarian crises and develop subsequent evidence-based solutions. All efforts must be made in meaningful participation with women and girls with disabilities and their caregivers to ensure interventions are appropriate.

Systematic review registration: Identifier: CRD42021250937.

At the end of 2020, 82.4 million of the global population (1 in 95 people) were forcibly displaced due to conflict, violence, and natural disasters (The UN Refugee Agency, 2021). An estimated 10.3 million of those were people with disabilities, which means a “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2008; World Health Organization World Bank, 2011).

A recent population-based survey of Syrian refugees living in Istanbul found that 25% of the population have a disability, and 60% of households included at least one person with disabilities (Polack et al., 2021). These data indicate that more people with disabilities may be affected by emergencies than previously estimated.

Humanitarian crises, such as conflict, can also generate trauma and injuries, which can result in disabilities (World Health Organization World Bank, 2011). People with disabilities face inequalities in accessing healthcare services, education, and employment because of informational, attitudinal, accessibility, and financial barriers faced (Mitra et al., 2013; Mactaggart et al., 2018; Kuper and Heydt, 2019). These inequalities can be exacerbated during crises (United Nations General Assembly, 2016). For instance, morbidity rates of people with disabilities are up to four times higher than those without disabilities (United Nations Economic Social Commission for Asia the Pacific, 2015), and 60% of COVID-19 deaths in the UK were amongst people with disabilities, even though they make up 17% of the population (Glover and Public Health England, 2020; Kuper et al., 2020). Humanitarian and basic human rights principles require assistance to be provided without discrimination (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2008; CBM International HelpAge International, 2018; Sphere, 2018; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021). Yet efforts to ensure the inclusion of people with disabilities in humanitarian efforts are limited (Robinson et al., 2020). A recent review of international guidance on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) responses during the COVID-19 found that one-third did not include any references to the rights of people with disabilities, and the majority of references were made in one guidance document (Scherer et al., 2021a).

People with disabilities in humanitarian crises may experience multiple forms of discrimination including, gender, impairment, and age (Crenshaw, 1991; McCall, 2005). For instance, women with disabilities are at heightened risk of sexual violence during emergencies (UN Committee on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, 2016; Barrett and Marshall, 2017). Women and girls with disabilities also have gender-specific needs, such as menstrual health. Globally, an estimated 190 million people with disabilities rely on informal and professional caregivers for assistance (World Health Organization, 2021), so many women and girls with disabilities in humanitarian crises may be dependent on others to support their menstrual health.

Menstrual health is defined as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in relation to the menstrual cycle” (Hennegan et al., 2021). Menstrual health includes having clean and affordable menstrual material, facilities to change and dispose of the material hygienically and privately, access to soap and water to wash the body and menstrual material used. It also means understanding what menstruation is, how to manage it hygienically, having access to diagnosis and treatment for menstrual-related disorders, and a positive environment free from menstrual-related stigma and discrimination. Women and girls in low-and middle-income countries face numerous challenges managing menstruation hygienically and with dignity (Hennegan et al., 2019). Evidence shows that inadequate menstrual health impinges education attainment (Sommer, 2010; Phillips-Howard et al., 2016; Miiro et al., 2018), gender equality (Winkler and Roaf, 2015; Caruso et al., 2017), health and wellbeing (Crichton et al., 2013; Mason et al., 2013).

In humanitarian crises, menstrual health challenges can be heightened. For instance, women and girls may flee their home without menstrual materials (e.g., disposable or reusable pads, cloth, underwear), they may live in settlements without safe and private water points, latrines or bathing shelters where they can wash their bodies, and change, wash or dispose of menstrual materials (Phillips-Howard et al., 2016; Schmitt et al., 2021). In crises, women and girls from diverse socio-cultural and economic backgrounds may live together in host communities, camps or informal settlements. Women and girls might believe that they should live separately from men and boys whilst menstruating, and dispose of used menstrual materials, or dry reusables in private where men and boys cannot see them (Sommer, 2012; De Lange et al., 2014; Phillips-Howard et al., 2016). The humanitarian emergency may disrupt these practices, causing psychological stress, so humanitarian responses must take these preferences into account when designing menstrual health interventions. They must also cover a range of sectors, including water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), sexual and reproductive health and rights, women and child protection, education and shelter because facilitators for menstrual health are included in these areas (Phillips-Howard et al., 2016). Furthermore, the response phase (e.g., search and rescue, emergency relief, early recovery, medium to long-term recovery and community development) (Crutchfield, 2013) as well as the type of emergency, determine the required menstrual health response (Sommer et al., 2016; Sphere, 2018).

Little evidence exists in the literature about the challenges that women and girls with disabilities face in humanitarian crises and no prior evidence syntheses exist on the topic. However, data from non-emergency settings in Vanuatu show that harmful menstrual beliefs affect all women and girls who menstruate, but when disability and menstrual-related discrimination overlap, they further entrench existing inequalities (Scherer et al., 2021b). For instance, inaccessible water and bathing facilities, and socio-cultural expectations that women and girls must manage menstruation independently, resulted in heightened pain, discomfort, and a lack of safety during menstruation, especially for people with mobility limitations and people who are reliant on caregivers. A systematic review on menstrual health and disability noted that people with mobility limitations found menstrual materials uncomfortable and difficult to use; information on menstruation is withheld from people with intellectual impairments who are at risk of sterilization, partly because caregivers wish to cease menstruation (Wilbur et al., 2019a). Caregivers were given no support or guidance to carry out menstrual care tasks hygienically and with dignity (Wilbur et al., 2019a).

This systematized review had two interrelated objectives: to (1) identify and map the scope of available evidence on the inclusion of disability in menstrual health during emergencies and (2) understand its focus in comparison to efforts to improve menstrual health for people without disabilities in emergencies.

Grant and Booth (2009) define a systematized review as including some, but not all elements of the systematic review process. Due to the paucity of literature in the field, we were unable to apply a standardized reference scale to assess the quality of included papers, which is recommended when conducting a systematic review (Higgins et al., 2019). Instead, we drew on 20 years' experience in the field and knowledge of existing similar literature to construct a simple rating scale which aims to assess the quality of the papers included (see Section Quality assessment).

Throughout the article, we refer to “women and girls” to increase readability, but the authors recognize that menstrual health is relevant for everyone who menstruates, regardless of gender identity.

A review protocol is registered online with PROSPERO; registration number: PROSPERO CRD42021250937.

The search strategy was designed to identify peer-reviewed and gray literature which explored menstrual health for people with and without disabilities in emergency settings. The review covered all countries and languages and did not set a date limit, to ensure the widest range of papers could be identified.

Searches were conducted in February 2020 and repeated in August 2021 to ensure any guidance produced during COVID-19 was identified. Six online databases were used: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Global Health through Ovid SP, ReliefWeb, and Cinahal Plus. A comprehensive search of gray literature was conducted using OpenGrey, Gray Literature Report, Google Scholar, and Million Short. Additional papers were identified by reviewing references of included papers and contacting humanitarian relief organizations that deliver WASH interventions, including menstrual health interventions. When papers were not available online, authors were contacted and asked for the full text.

Search terms were created to capture three main concepts: disability, menstruation, and humanitarian crises. Disability included specific impairments and broad assessments (e.g., self-reported activity or functional limitations). Humanitarian crises included: Geophysical, Meteorological, Hydrological, Climatic events, Biological, Man-made hazards, and Complex emergencies resulting from a combination of hazards. Supplementary Table S1 includes the search string for PubMed.

Eligible papers were in the gray literature or published in a peer-reviewed journal, included primary research, academic papers including theses, dissertations, and research reports, ongoing research, conference papers, organizational strategies, reports, guidance, blogs, and government reports. No exclusion criteria were set for the publication date, world region or language.

Eligible participants were women and girls with and without disabilities who menstruate, and caregivers who support individuals with disabilities with their menstruation. WASH interventions that aimed to improve menstrual health in humanitarian settings qualified. Comparisons were made between menstrual health efforts that did and did not consider disability.

Relevant outcomes included the ability to access supportive facilities to manage menstruation, use and preference of menstrual materials, menstrual-related challenges experienced and coping strategies applied during humanitarian crises.

Two authors conducted the database searches. All records retrieved were exported to EndNote version X9, and duplicates were removed. Three authors independently screened titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria, noting the rationale for inclusion/exclusion decisions for all records retrieved. Full-text papers were sourced for independent screening by two authors. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved, with a third reviewer's opinion being sought where necessary.

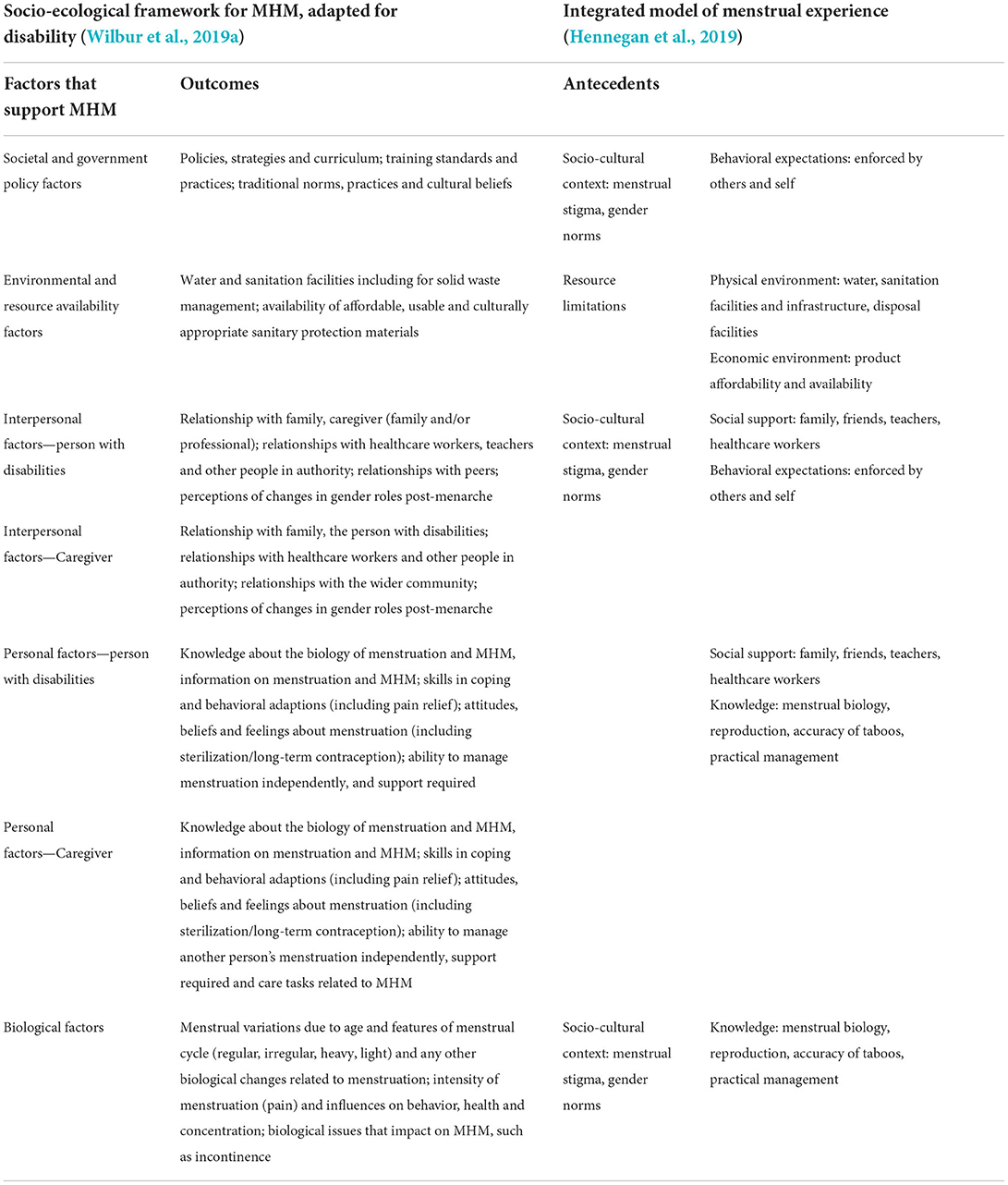

Data were extracted from identified papers using pre-designed tables based on the socio-ecological framework for menstrual hygiene management (MHM), adapted for disability to allow comparison across papers (Wilbur et al., 2019b). Table 1 presents the framework and incorporates the integrated model of menstrual experience, published by Hennegan et al. (2019). In this article, findings are presented against the latter, firstly for women and girls without disabilities and then with disabilities to enable comparison.

Table 1. Socio-ecological framework for menstrual hygiene management, adapted for disability compared to the integrated model of menstrual experience.

Data were extracted into Microsoft Excel against the factors that support MHM (Table 1) and the following: (1) paper details: author/s, year, title, (2) study location: World Bank region—low, middle or high-income country, country name, rural and/or urban, (3) humanitarian crisis type: geophysical, hydrological, climatic events, biological, man-made hazards, complex emergencies, (4) methods: study design, (5) participants: source of participants (household, camp, hospital, organization), disability type (e.g., sensory, mobility, cognition, communication), means of assessing disability (self-reported, clinical, government or organization list), caregiver type (family member, professional), sample size, (6) definition of menstrual health or measurement criteria, (7) quality assessment.

A narrative synthesis of extracted data is presented in this article. As study designs varied considerably, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

The quality of the papers was assessed using two different sets of criteria. The guideline, strategy or policy papers were assessed against six criteria: explanation of context with clear aims and objectives; aims and objectives supported by the data; inclusion of the perspectives of participants (people with disabilities, organizations of persons with disabilities); consultation with organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) or experts during the development of the document; stakeholder involvement; and use of humanitarian standards as a framework. Papers scoring 4–6 were counted as high quality, papers scoring 2–3 were judged as medium quality, and papers scoring 0 or 1 were low quality.

For the other types of paper (primary research, published protocols, literature review/systematic review, journalistic articles or conference presentation), the following six criteria were used: details of sampling strategy provided; details on methods provided; humanitarian actors included; people receiving humanitarian assistance included; people with disabilities or caregivers included; results demonstrably backed by data, either by using case studies or summaries of responses. Once more, papers scoring 4–6 were rated as high quality, papers scoring 2–3 as medium quality, and papers scoring 0 or 1 as low quality. Supplementary Table S2 presents a summary of the quality of included papers.

The review flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

A total of 51 papers were selected for data extraction using the criteria described in Methods (study selection and data extraction). Table 2 shows the publication characteristics of the 51 papers.

Table 2 describes the 51 papers included in the review. Eight of the 51 papers (16%) were published in peer-reviewed journals or had been peer-reviewed prior to publication. These included four papers containing primary research, three literature reviews or systematic reviews, and one meeting report (classified with the literature and systematic reviews).

Due to the predominance of gray literature as a source in our review, papers reporting the results of primary research did not necessarily contain descriptions of the methodologies used, or any quantification of findings. The primary research ranged from interviews with displaced people (Human Rights Watch, 2017) to training projects for actors in humanitarian settings (Phillips-Howard et al., 2016), to purposively sampled key informant interviews synthesized with results from focus groups and literature reviews (Brown et al., 2012).

In the 51 papers, menstrual health and disabilities were discussed with varying degrees of detail. Twenty-six (51%) discussed menstrual health and disability in humanitarian settings; however, some of these discussions were very brief, acknowledging the issues but not providing any depth of discussion. Seventeen of these 26 papers (65%) papers discussed issues of disability in humanitarian settings, and issues of menstrual health in humanitarian settings, but not the overlap between these the two. The remaining 25 papers (49%) discussed either menstrual health or disability, with the other mentioned in passing (Brown et al., 2012; Reed and Coates, 2012; Sthapit, 2015; Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Sommer et al., 2016, 2018; Fisher et al., 2017; Human Rights Watch, 2017; D'Mello-Guyett et al., 2018).

For the eight peer-reviewed studies, four (Reed and Coates, 2012; Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Sommer et al., 2016, 2018) contained primary research. The other four (Sthapit, 2015; Fisher et al., 2017; D'Mello-Guyett et al., 2018) were literature reviews, systematic reviews or meeting reports.

Of the 51 papers, 34 (67%) were assessed as high quality and 14 (27%) as medium quality. Across the “type of paper”, the literature reviews and systematic reviews scored high on quality. Comparatively, the primary research scores less on quality, with 15 (79%) high quality and four (27%) medium quality. Of the eight peer-reviewed papers, two (25%) scored high quality and six (75%) medium quality. Table 3 provides a summary of quality assessment by type of paper. Supplementary Table S3 presents a summary of the results of individual papers.

In general, people with disabilities were rarely consulted in the preparation of reviews about menstrual health. Of the 35 papers that were not guidelines, strategies or policy papers (see Table 2), seven consulted people with disabilities or caregivers (UNICEF, 2016; Humanitarian Response, 2020). Nine of the 16 papers that were guidelines, strategies, or policy documents explicitly described consulting people with disabilities, caregivers or OPDs. Overall, 16 (31%) of papers potentially consulted people with disabilities on menstrual health issues.

House (2013) noted that people with disabilities are less likely to participate in community decision-making. Therefore, their views on sanitation (and, by extension, menstrual health) are less likely to be heard. This exclusion is particularly crucial as people with disabilities can face barriers to accessing WASH interventions, including those relating to the environment, infrastructure, policy or institution, attitudes, and physiological attributes (House, 2013).

Stigma from peers (House et al., 2012; Mena, 2015) and societal constraints on freedom of movement affected women's and girls' ability to seek support (House et al., 2012; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018). Support networks included family, teachers, and health organizations (House et al., 2012; House, 2013; Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Abu Hamad et al., 2017; Amoakoh, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019).

Behavioral expectations resulted in restrictions on women's and girls' daily activities during menstruation, including being unable to cook, stay in the family home, or use the family sanitation facilities (Harvey et al., 2004; House et al., 2012; Bastable and Russell, 2013; House, 2013; Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2018; Madigan, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019; Toma, 2019). Some restrictions could lead to girls missing school during menstruation (House, 2013; UN Women, 2017).

Many girls and women reported having poor knowledge of the biology of menstruation at the menarche (Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Abu Hamad et al., 2017; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019; Toma, 2019) and consequent demand for access to more comprehensive information about menstrual health (House, 2013; Jay and Lee-Koo, 2018). This information could be transmitted through schools, community channels, including female religious leaders, and better information for mothers (often menstrual health influencers) (House et al., 2012; House, 2013; Ndlovu and Bhala, 2016; Sommer et al., 2017; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019).

Accurate information on the menstrual cycle and how to manage it hygienically and with dignity is a critical component of menstrual health, the lack of which can have consequences for women's health, including infections such as vulvovaginal candidiasis (House et al., 2012; Phillips-Howard et al., 2016). In emergency settings, women and girls may be receiving menstrual materials that they are not familiar with and, therefore, will require instruction on their use, including changing, washing and drying or disposing of materials (Sommer et al., 2017). Other authors recommend that the correct use of materials should be demonstrated (UN Women, 2017; Amoakoh, 2019).

The need for training in the use of menstrual materials may also apply to humanitarian personnel. Two authors identified a need for training for humanitarian staff (both male and female) to allow them to address menstrual health confidently and appropriately (Rohwerder, 2014; Sommer et al., 2016). Examples of inappropriate provision include a male logistician in Haiti who procured g-string underwear for use with pads (Rohwerder, 2016) while other logistics personnel distributed menstrual pads one at a time (Rohwerder, 2014). In one setting, some women were provided with underwear with a skull and crossbones pattern (Rohwerder, 2014).

People with disabilities may face additional stigma around menstrual health with people not expecting girls with disabilities to menstruate, reducing the information and social support available to them (House et al., 2012). In general, it was noted that girls with disabilities had reduced social support (Sommer et al., 2017) and smaller networks (Rohwerder, 2017). Girls with disabilities are less likely to attend school (van der Gaag, 2013; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2017; World Health Organization, 2017; Toma, 2019), with consequences for their social support networks. This exclusion could be exacerbated in an emergency as regular networks are disrupted (Rohwerder, 2017).

House et al. recommends that caregivers should be female and chosen by the woman or girl for physical assistance with menstrual health. Programs should be followed consistently by all caregivers involved, and the woman or girl's respect, privacy, and dignity should be prioritized (House et al., 2012). Furthermore, women and girls with disabilities may be isolated in their homes (Pearce, 2015) or have even less access to their communities and social support (Sommer et al., 2016). Outside the home, people with disabilities may need additional support from carers to prevent behaviors such as changing in inappropriate places (Sommer et al., 2017) or removing used menstrual materials in public (House et al., 2012).

Where necessary, educational materials on menstrual health should be provided in alternative formats (such as audio or pictures) (Sommer et al., 2017; Humanitarian Response, 2020). People with disabilities may not attend school and, therefore, may be unable to access lessons on menstrual biology (Sommer et al., 2017). Direct outreach to people with disabilities may therefore be necessary (Sommer et al., 2017), and feedback must be sought to ensure that people understand the material (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019).

Caregivers for people with disabilities may also need education on the biology of menstruation and assurances that menstruation is normal (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017). One case study reports a Burundian man caring for his sister who had a disability and sought assistance from humanitarian workers to help his sister manage her menstruation. He was given disposable pads and shown how to support his sister with their use (Sommer et al., 2017). This example points to a more general need for caregivers to be shown how to help menstrual health in people with disabilities (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017).

Many of the papers included in this review (n = 24, 47%) commented on sanitation facilities and infrastructure for menstrual health in emergencies, perhaps because menstrual health has historically been seen as a WASH sector issue (Sommer et al., 2016).

Housing and shelter in emergency settings pose challenges for menstrual health. Overcrowded or cramped living conditions may not offer enough privacy for girls and women to manage their menstrual health (Sommer et al., 2016; Abu Hamad et al., 2017; Rohwerder, 2017; Madigan, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019). This lack of privacy for washing and drying menstrual cloths can lead to incomplete drying of materials and consequent perineal rashes and urinary tract infections (van der Gaag, 2013). Communal shelters, in particular, need private areas for women and girls to attend to their menstrual health without having to leave their homes at night (Sommer et al., 2016).

Surveys of women and girls in humanitarian settings identified difficulties with managing menstruation in latrines. Problems identified included: a lack of soap (Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); lack of doors and door locks (Bastable and Russell, 2013; van der Gaag, 2013; UN Women, 2017; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); lack of privacy (Bastable and Russell, 2013; Madigan, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); lack of space for washing and drying hands and menstrual materials (UN Women, 2017; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Madigan, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); poor lighting at night (Bastable and Russell, 2013; van der Gaag, 2013; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Madigan, 2019); poor siting of latrines (Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019; Humanitarian Response, 2020); unsegregated latrines (van der Gaag, 2013; UN Women, 2017; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Madigan, 2019), and dirty, smelly or overcrowded latrines (Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019).

There was overlap in the literature about the infrastructure necessary to make facilities suitable for menstrual health management. The following features were specified: sex-segregated latrines (Harvey et al., 2004; van der Gaag, 2013; Sommer et al., 2016; Sphere, 2018); lights (Sommer et al., 2016, 2017; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Sphere, 2018); door locks (Harvey et al., 2004; House et al., 2012; van der Gaag, 2013; Sommer et al., 2017; Joint Agency Research Report, 2018; Sphere, 2018); separate private bathing spaces (Joint Agency Research Report, 2018), including screening around shower facilities (Bastable and Russell, 2013); private cubicles for washing menstrual cloths, as part of washrooms or laundry facilities (House et al., 2012; Bastable and Russell, 2013; Sommer et al., 2017; Amoakoh, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); hand washing facilities (Harvey et al., 2004; Sommer et al., 2016); discreet drainage for laundry and bathing spaces (Sommer et al., 2017; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); drying facilities (House et al., 2012; Bastable and Russell, 2013; Mena, 2015; Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); disposal facilities (House et al., 2012; Mena, 2015; Sommer et al., 2016; Sphere, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019). Other adaptations could include a hook or shelf inside toilet cubicles and mirrors inside the latrines (Sommer et al., 2016). Consultation with women and girls on materials, siting, design and management of facilities was identified as a priority (Harvey et al., 2004; Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018; Humanitarian Response, 2020).

Overcrowded living space can have an even more significant impact on women and girls with disabilities, who may need more space to allow for the assistance of a caregiver (Rohwerder, 2017). There were few direct reports of the menstrual health needs of people with disabilities related to accessing latrines to change, wash and dry menstrual materials. One person with disabilities commented that a ramp to the latrine and a wheelchair provided by humanitarian assistance enabled her to use the toilet (van der Gaag, 2013).

A need for accessible toilet facilities was highlighted in the literature (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2016, 2017, 2018; Sphere, 2018; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019; Humanitarian Response, 2020). Suggested modifications to improve accessibility for people with disabilities include security lighting (Harvey et al., 2004); extra rails (Harvey et al., 2004; House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017), access ramps (Harvey et al., 2004; House et al., 2012; House, 2013; Sommer et al., 2017; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019), larger cubicles (Harvey et al., 2004; House et al., 2012); wider doors (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019); door handles of appropriate height and size (Harvey et al., 2004; House, 2013; Sommer et al., 2017; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019); taps of appropriate height (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019); slip-resistant surfaces (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017); chairs placed inside the toilet (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017); latrines sited close to the homes of people with disabilities (Harvey et al., 2004), and support for washing hands (Harvey et al., 2004).

One report (Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2017), noted that WASH facilities are often not built to be accessible for people with disabilities, and guidance documents lack information about accessibility (House, 2013). Some reports acknowledged the need to consult with people with disabilities and their caregivers to design appropriate solutions (Sommer et al., 2017; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2018; Sphere, 2018; Amoakoh, 2019).

Pre-existing barriers to WASH facilities have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (CBM Water for Women Fund, 2020; Wilbur, 2020, in press; Scherer et al., 2021b), and the pandemic has increased the importance of making WASH facilities accessible for people with disabilities (Emirie et al., 2020). Specific to menstrual health for people with disabilities, standards for disability inclusion require that women and girls have spaces for washing, including space for a caregiver, and space to wash and dry stained clothing and materials and dispose of materials (Rohwerder, 2017).

Water may be scarce in an emergency setting. Host communities in Bangladesh reported a water shortage following an influx of refugees on the border (Joint Agency Research Report, 2018). In a refugee camp in the Philippines, a single water source might be shared by 100 families (van der Gaag, 2013). These resource limitations have clear implications for menstrual health, which requires water for washing and drying materials, hands and bodies (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017). Consulting women and girls on the siting of water points were recommended, partly to address security concerns (Sommer et al., 2017; Madigan, 2019).

People with disabilities may have difficulties accessing water points, using pumps or carrying water (House, 2013). As noted above, toilet and bathing facilities may need to be adapted so that people with disabilities can access water within the facilities to support their menstrual health.

Disposal mechanisms for used menstrual materials were often not considered in setting up WASH facilities in emergencies (Sommer et al., 2016). The disposal preference for used menstrual materials is affected by cultural beliefs and practices, such as burning or burying menstrual waste (House et al., 2012; Rohwerder, 2017; Humanitarian Learning Centre, 2018). Women might prefer to dispose of their pads in the latrine or toilet, which has implications for blocking and desludging latrines (House et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2016). In one case, the bins for disposable materials were not covered, so women put used materials behind pipes in the shower cubicles where they could not easily be seen (Mena, 2015).

The Sphere handbook notes the need for appropriate disposal systems (Sphere, 2018), which must be convenient, private and hygienic (van der Gaag, 2013; Sommer et al., 2017). These systems need to be designed in consultation with women and girls (Mena, 2015; Amoakoh, 2019) to consider local preferences.

Convenient and accessible disposal facilities are essential for people with disabilities who may need access to adapted spaces or help from a caregiver to manage their menstrual health (House et al., 2012). Consultation with people with disabilities and caregivers on suitable disposal mechanisms is required (Amoakoh, 2019; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019).

Product affordability did not feature heavily in the literature searched, other than noting that the relative affordability of different menstrual materials might influence people's preferences (House et al., 2012). However, the affordability of menstrual materials against other needs was flagged as an important issue in using cash transfers or voucher schemes in emergency settings (Ferron, 2017). Women interviewed about cash transfers for non-food items often preferred vouchers for specific items because they could be sure they could access the items they needed (Ferron, 2017). Some women preferred to be given hygiene kits because they felt respected and did not have to buy menstrual materials with limited money (Rohwerder, 2014).

Ferron (2017) recommended carrying out market assessments before implementing cash transfers to make sure that the items are available and markets are functioning. There may also be issues of market distortion. In one setting, women did not buy menstrual materials they could afford, preferring instead to use the free materials they were given (Ferron, 2017).

If cash transfers or vouchers are used to obtain menstrual products, there are access implications for people with disabilities, which include the process of registering for schemes, the accessibility of the technology used (such as mobile phone credit), the accessibility of distribution points, and the accessibility of shops and markets participating in the scheme, including transport options (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019).

The provision of menstrual materials may be seen as a low priority in an emergency setting (van der Gaag, 2013), and local preferences may not be considered (Sommer et al., 2016). One expert noted: “The need for culturally-appropriate sanitary materials is a constant refrain in all humanitarian responses and an area that we continually fail/fall short on” (Rohwerder, 2014).

Hygiene kits in emergency settings sometimes do not contain enough menstrual materials (Rohwerder, 2014). Research by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) found that in 2004, 10 of 53 refugee camps distributed adequate menstrual materials (UNHCR, 2006). In one survey in Bangladesh, 25% of women said they did not have sufficient supplies to meet their menstrual health needs (Joint Agency Research Report, 2018), while another found that 24% of women and girls had not received menstrual materials within the last 3 months (Humanitarian Response, 2020). In Mozambique, women also identified a lack of supply of materials (Madigan, 2019).

If reusable materials are being given, women need enough so that supplies can be washed and dried whilst another is in use (House et al., 2012; Rohwerder, 2014). Tampons and menstrual cups depend on water supply and soap for hand hygiene (House et al., 2012). Other considerations include product availability, comfort, changing frequency, security, color, need for underwear, and how much of a product is required (House et al., 2012). In another example, menstrual cloths of an unfamiliar color and thickness were supplied to women and girls in Pakistan and Kenya. They were not used, used for other purposes, or thrown away (van der Gaag, 2013). In one setting in Bangladesh, women were given new saris so they could use the old ones for menstrual cloths, but the old saris were not used as humanitarian agencies intended (Ferron, 2017). In Mozambique, there was insufficient cloth to make reusable pads (Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019). In one setting, women received reusable pads but no soap and wrong-sized underwear (Phillips-Howard et al., 2016). Some organizations provide menstrual pads without underwear, making them harder to use or with inappropriate underwear (Rohwerder, 2014, 2016).

Materials included in hygiene kits were: cotton material (Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); disposable pads (Sommer et al., 2017; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); reusable cloth pads (Sphere, 2018); extra soap (Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); container with a lid for soaking or storing pads (Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); plastic basin for washing (Rohwerder, 2014); rope and pegs for drying reusable materials (Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018); analgesia (Rohwerder, 2014); torch (Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019), and underwear (Sommer et al., 2017; Sphere, 2018).

Some authors noted that the contents of a hygiene kit might need to be adapted for use by people with disabilities (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019; CBM Water for Women Fund, 2020); or that hygiene kits could be standardized to include the needs of people with disabilities (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019). These adaptations might consist of additional supplies (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2019; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019) and extra items such as protective bedding for people unable to mobilize (Sommer et al., 2017; Shaphren and Cuadra, 2019); supplementary items such as menstrual calendars could also be helpful (House et al., 2012). People with disabilities and caregivers should be consulted about their needs (Sommer et al., 2017; Amoakoh, 2019) and have opportunities to decide which products suit them (House et al., 2012).

One author noted that the distribution system of hygiene kits might not be reaching people with disabilities (Madigan, 2019). In one case, a woman was sharing her menstrual materials with her daughter, who had learning difficulties and did not attend school and had not been issued with menstrual materials (Sommer et al., 2018). Distribution centers could be adapted to be accessible (Sommer et al., 2017), or house visits might be more appropriate for people who are unable to leave the home (Madigan, 2019).

This study had two objectives: to (1) identify and map the scope of available evidence on the inclusion of disability in menstrual health during emergencies and (2) understand its focus in comparison to efforts to improve menstrual health for people without disabilities in emergencies. We found significant gaps in attention to menstrual health for all women and girls in emergency settings. However, the lack of information relevant to women and girls with disabilities was particularly stark. Most data related to increasing access to WASH services for women and girls with disabilities, with significant gaps highlighted against other aspects of menstrual health, such as providing information in accessible formats.

Much has been written on the social support, behavioral expectations and knowledge related to menstruation and how harmful social beliefs can negatively impact women and girls' ability to thrive (Hennegan et al., 2019; Wilbur et al., 2019a). Our study highlights that those menstrual socio-cultural beliefs are also followed in emergencies. Critical support networks can be interrupted in humanitarian settings; impacts of disruptions may be greater for people with disabilities because they face discrimination in daily life and, therefore, may have smaller social support networks. These changes and loss of routine can be particularly traumatic for people on the autistic spectrum, which has been documented in the COVID-19 pandemic, along with a call for more autistic-specific advice and information (Ameis et al., 2020; Oomen et al., 2021).

Behaviors before and during menstruation carried out by people with intellectual impairments can include withdrawal, self-harm, increased hyperactivity, anger, and shame, as well as removing a menstrual material in public (Kyrkou, 2005; Chou and Lu, 2012; Thapa and Sivakami, 2017; Wilbur et al., 2021a,b). These behaviors may be amplified during emergencies when people are more likely to be frightened and feel vulnerable. Repetition of information through various mediums and establishing new norms and routines have successfully supported the menstrual health of women and girls in Nepal (Wilbur et al., 2019b). Such gains could be lost during emergencies unless clear and repetitive information on menstrual health is provided to the individual and caregiver where relevant.

Our study shows conflicting data between the recommendation that caregivers should be women and identified by people with disabilities and the need to ensure that everyone who provides care, regardless of gender, should be supported. As social networks may be disrupted, men may help women and girls with disabilities manage menstruation for the first time. Therefore, it is important not to enforce or assume traditional gender roles, which may exclude male caregivers who need support and guidance. Instead, the wishes and choices of the person with a disability should be encouraged as much as possible through supported decision-making.

Existing evidence highlights that people with disabilities may be more negatively affected by poor housing conditions than people without disabilities during emergencies (Sheppard and Polack, 2018). Impacts include an increased dependency on self-care, being housebound and socially isolated, which may worsen existing health conditions and social exclusion. Our findings reflect these concerns but also demonstrate that all women and girls face challenges accessing water, using safe and private latrines and bathing shelters to change, wash the body and menstrual materials, or end-use disposal mechanisms. However, women and girls with disabilities face additional barriers. Technical guidance on how to make WASH infrastructure accessible for people with disabilities exists (Jones and Reed, 2005; Jones and Wilbur, 2014; Government of India, 2015), including WASH in emergencies (UNICEF, 2017; Coultas et al., 2020). These resources include suggestions about how to make “reasonable accommodations”, which are ad-hoc temporary arrangements to accommodate one or more people with disabilities—such as placing a temporary and movable wooden ramp to the entrance of a latrine (Coultas et al., 2020) or a movable toilet seat over a traditional pit latrine (Jones and Wilbur, 2014). These designs could facilitate greater access to latrines for people with disabilities and their caregivers. Yet more technical guidance about how to make menstrual material disposal mechanisms fully accessible is required.

Most of our study findings related to people with disabilities centered on accessible WASH facilities. Though this sector is vital for menstrual health, a narrow focus would risk not addressing the issue in its entirety, and people with more “invisible” impairments (such as cognitive and communication) may be unintentionally excluded from menstrual health efforts. “Inclusive WASH” is widely understood as accessible infrastructure (Coe and Wapling, 2015; Wilbur et al., 2021b), but inclusive WASH is not an output; it is “a process which addresses the barriers to accessing and using WASH services faced by people who are vulnerable to exclusion, including people with disabilities” (Wilbur et al., 2021a). Ensuring accessible information and WASH infrastructure, challenging negative stereotypes, integrating disability into policy commitments and monitoring progress, and ensuring the participation of people with disabilities and caregivers in all these activities are all part of inclusive WASH.

Inadequate effective and meaningful participation of people with disabilities in WASH programs, from design to evaluation, has been widely documented in development settings (Groce et al., 2011; UN Water, 2015; Scherer et al., 2021b; Wilbur et al., 2021b). Evidence also exists from humanitarian settings, including two papers which explore the extent to which the rights of persons with disabilities are included in international guidance on WASH responses to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 (Scherer et al., 2021a) and interventions (Wilbur, in press). Both found that participation was referenced significantly less than ensuring access to WASH infrastructure in guidance documents (Scherer et al., 2021a) and interventions (Wilbur, in press). These patterns are apparent in our study. Participation can boost self-confidence, which could, in turn, reduce stigma and self-stigma (Corrigan et al., 2009). Supporting the autonomy and agency of people with disabilities can also challenge broader misconceptions about disability, including that they cannot contribute to the community's development. In a study in Zambia, enabling the meaningful participation of people with disabilities in the design of communal water points resulted in changes in infrastructure design, making it easier for all people to use. This visibility positively impacted community members' attitudes toward people with disabilities (Danquah, 2015). The participation of women and girls with and without disabilities and caregivers in humanitarian contexts would raise awareness about their specific requirements and support the development of relevant and culturally acceptable solutions.

Our study shows that significantly more attention must be given to ensuring all women and girls in emergencies can access affordable, effective and culturally appropriate menstrual materials, information about how to use these and effective distribution mechanisms. Encouragingly, menstrual underwear and a wash and dry bag to reduce menstrual waste and disposal challenges in humanitarian contexts are currently being developed and pilot tested (Elrha, n. d.-b). Furthermore, the feasibility of integrating menstrual health education and menstrual hygiene kits that contain the menstrual cup or reusable menstrual materials is being explored in refugee settlements in Uganda (Elrha, n. d.-a). Such innovations and studies should also be piloted with and include women and girls with different impairments and their caregivers to understand their appropriateness for these populations. Consideration must be given to the specific needs of women and girls with disabilities, including based on their impairment (Charlifue et al., 1992; Patage et al., 2015), ability to leave home, understand information and instructions; ability to afford and access transport, shops or distribution site, as well as access to social protection schemes, including cash transfers (Sheppard and Polack, 2018).

Our study has highlighted the need to ensure distribution centers are fully accessible for people with disabilities. However, potential challenges in navigating the environment for people without the assistive devices they need (e.g., wheelchair, hearing aid, walking cane) must be recognized. For instance, only 5–15% of people who require assistive devices have them in low-and middle-income countries (World Health Organization World Bank, 2011); this gap could be worse in emergencies where existing disability services may be disrupted or if assistive devices are lost or damaged. Visiting the homes of women and girls with disabilities is essential to ensuring menstrual materials are distributed to everyone who requires them. This adaptation is recognized in the United Nations Human Rights Council's first resolution on MHM, which includes the call to deliver menstrual health information and education to caregivers and “out-of-school settings” in “peace time”, as well as emergency preparedness and responses (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021).

Significantly more data about menstrual health and disability in emergencies must be generated, and their findings should feed into training for implementers. In 2017, A Toolkit for Integrating Menstrual Hygiene Management into Humanitarian Response was published (Sommer et al., 2017), pilot-tested and evaluated in Tanzanian refugee camps (Sommer et al., 2018). The toolkit contains modules on training and menstrual hygiene management for vulnerable populations, which includes women and girls with disabilities. This toolkit is positive, but integrating disability explicitly in its training modules is required to raise awareness and increase staff capacities to communicate menstrual health-related information confidently and in accessible formats. This mainstreaming is important because people with disabilities report that they are 50% more likely to find healthcare staff skills inadequate, four times more likely to receive ill-treatment in the healthcare system and less able to understand the information provided (World Health Organization World Bank, 2011). These statistics might be worse in humanitarian settings, where activities need to be carried out quickly and healthcare resources are in more limited supply, such as during the “emergency relief” phase (Crutchfield, 2013).

Menstrual health in emergencies requires multisectoral responses. This includes disability-related services, WASH, women and child protection, sexual and reproductive health, shelter, and education. Core to all efforts must be the involvement of people with disabilities, including Organizations of Persons with Disabilities, in all phases from inception to evaluation. Only this meaningful engagement will ensure that women and girls with disabilities are at the front and center of their own menstrual health development initiatives.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first review (systematized or otherwise) that explores the menstrual health experiences of women and girls with and without disabilities in humanitarian emergencies. It also includes a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed and gray literature.

However, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. Of the included papers that identified a region, the majority focused on Southern Asia, followed by Eastern Africa, but none were from the Pacific region. More than half of the papers did not specify the types of crises, but of those that did, man-made received the most attention and hydrological and climatic, the least. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to all contexts. Though non-English papers were not excluded, English search terms were used, so some papers in languages other than English might have been missed. Finally, no study specified the impairments experienced by women and girls with disabilities, so a comparison of menstrual experiences across impairment groups could not be completed. In addition, the quality assessment criteria used in this review could not be validated against similar criteria in the literature due to the dearth of papers published in the field.

This study demonstrates gaps in attention to menstrual health for women and girls in humanitarian crises and underscores that disability and menstrual discrimination overlap to increase inequalities during emergencies. Few interventions were identified addressing the requirements of women and girls with disabilities and their caregivers. More evidence about the requirements of these populations in humanitarian crises must be generated, and subsequent solutions developed. Women and girls with disabilities and their caregivers must meaningfully participate throughout the whole process to ensure menstrual health efforts are appropriate.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JW: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. FC: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. ES: data curation, investigation, and writing—review and editing. LB: writing—review and editing. CM: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by Elrha Humanitarian Innovation Fund, Grant Number: 45437. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author CM was employed by World Vision. Author JW reported grants from World Vision.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2022.983789/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table S1. Type of paper reviewed.

Supplementary Table S2. Summary of quality for included papers.

Supplementary Table S3. Summary of results from individual papers.

Abu Hamad, B., Gercama, I., Jones, N., and Abu Hamra, E. (2017). No one told me about that: exploring adolescent access to health services and information in Gaza. Gender Adolesc. Global Evid. Available online at: https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/GAGE-Health-Briefing-Gaza.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

Ameis, S. H., Lai, M.-C., Mulsant, B. H., and Szatmari, P. (2020). Coping, fostering resilience, and driving care innovation for autistic people and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Molecular Autism. 11, 61. doi: 10.1186/s13229-020-00365-y

Amoakoh, S. D. (2019). Human Rights in Humanitarian Policy: Dissecting the Catalysts And barriers to Employing a Human Rights-Based Approach in Drafting Menstrual Health Into the Sphere 2018 Handbook. Columbia University.

Barrett, H., and Marshall, J. (2017). Understanding Sexual and Gender Based Violence Against Refugees With a Communication Disability and Challenges to Accessing Appropriate Support: A Literature Review. Available online at: https://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/sgbv-literature-review-2.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

Bastable, A., and Russell, L. (2013). Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion. Humanitarian Innovation Fund. Available online at: https://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/HIF-WASH-Gap-Analysis.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

Brown, J., Jeandron, A., and Cumming, O. (2012). Water, sanitation and hygiene in emergencies: summary review and recommendations for further research. Waterlines. 31:11–29. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2012.004

Caruso, B. A., Clasen, T. F., Hadley, C., Yount, K. M., Haardörfer, R., Rout, M., et al. (2017). Understanding and defining sanitation insecurity: women's gendered experiences of urination, defecation and menstruation in rural Odisha, India. BMJ Global Health. 2, e000414. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000414

CBM International and HelpAge International (2018). Humanitarian Inclusion Standards for Older People and People With Disabilities. London: CBM International, HelpAge International.

CBM and Water for Women Fund (2020). Disability Inclusion and COVID-19: Guidance for WASH Delivery. Melbourne: CBM, Water for Women Fund.

Charlifue, S. W., Gerhart, K. A., Menter, R. R., Whiteneck, G. G., and Scott Manley, M. (1992). Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 30, 192–199. doi: 10.1038/sc.1992.54

Chou, Y. C., and Lu, Z. Y. (2012). Caring for a daughter with intellectual disabilities in managing menstruation: a mother's perspective. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 37, 1–10. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2011.651615

Coe, S., and Wapling, L. (2015). Review of Equity and Inclusion. Phase 2 Report: Country Programme Reviews and Visits - Mali, Nepal and Bangladesh. London, England: WaterAid.

Corrigan, P. W., Larson, J. E., and Rüsch, N. (2009). Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry 8, 75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x

Coultas, M., Iyer, R., and Myers, J. (2020). Handwashing Compendium for Low Resource Settings: A Living Document Brighton, UK: The Sanitation Learning Hub Institute of Development Studies (Brighton).

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Crichton, J., Okal, J., Kabiru, C. W., and Zulu, E. M. (2013). Emotional and psychosocial aspects of menstrual poverty in resource-poor settings: a qualitative study of the experiences of adolescent girls in an informal settlement in Nairobi. Health Care Women Int. 34, 891–916. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.740112

Crutchfield, M. (2013). Phases of Disaster Recovery: Emergency Response for the Long Term. London, UK: ReliefWeb. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/phases-disaster-recovery-emergency-response-long-term (accessed March 01, 2021).

Danquah, L. (2015). Undoing Inequity: Inclusive Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programmes That Deliver for All in Zambia. London, UK: WaterAid.

de Albuquerque, C. (2014). Realising the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: A Handbook by the UN Special Rapporteur Catarina de Albuquerque. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-water-and-sanitation/handbook-realizing-human-rights-water-and-sanitation (accessed March 01, 2021).

De Lange, R., Lenglet, A., Fesselet, J. F., Gartley, M., Altyev, A., Fisher, J., et al. (2014). Keeping it simple: a gender-specific sanitation tool for emergencies. Waterlines 33, 45–54. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2014.006

D'Mello-Guyett, L., Yates, T., Bastable, A., and Dahab, M. (2018). Setting Priorities for Humanitarian Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Research: A Meeting report DFID. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/setting-priorities-for-humanitarian-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-research-a-meeting-report (accessed March 01, 2021).

Elrha (n. d.-a). Feasibility of Reusable Menstrual Products in Humanitarian Programming. Available online at: https://www.elrha.org/project/feasibility-of-resuable-menstrua-products-in-humanitarian-programming/ (accessed March 01, 2021).

Elrha (n.d.-b). Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Waste Solutions: Innovative Underwear Laundry Bags. London UK: Elrha. Available online at: https://www.elrha.org/project/menstrual-hygiene-management-mhm-waste-solutions-innovative-underwear-and-laundry-bags/ (accessed March 01, 2021).

Emirie, G., Iyasu, A., Gezahegne, K., Jones, N., Presler-Marshall, E., Tilahun, K., et al. (2020). Experiences of vulnerable urban youth under Covid-19: the case of youth with disabilities. Gender Adolesc Global Evid. Available online at: https://odi.org/en/publications/experiences-of-vulnerable-urban-youth-under-covid-19-the-case-of-youth-with-disabilities/ (accessed March 01, 2021).

Ferron, S. (2017). Enabling Access to Non-food Items in an Emergency Response: A Review of Oxfam Programmes. London: Oxfam. Available online at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620325/er- enabling-access-non-food-items-emergency-response-100817-en.pdf? sequence=1 (accessed March 01, 2021).

Fisher, J., Cavill, S., and Reed, B. (2017). Mainstreaming gender in the WASH sector: dilution or distillation? Gender Dev. 25, 185–204. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331541

Giardina, D., Sorlini, S., and Rondi, L. (2016). Sanitation response in emergencies: lessons learnt from practitioners in post-earthquake Haiti. Environ. Eng. Manage. J. 15, 2029–2039. doi: 10.30638/eemj.2016.219

Glover, C., and Public Health England (2020). Deaths of People Identified as Having Learning Disabilities With COVID-19 in England in the Spring of 2020. GOV.UK: Public Health England.

Government of India (2015). “Handbook on accessible household sanitation for persons with disabilities (PWD),” in Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation SBMG.

Grant, M., and Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inform. Libraries J. 26, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Groce, N., Bailey, N., Lang, R., Trani, J. F., and Kett, M. (2011). Water and sanitation issues for persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review and discussion of implications for global health and international development. J. Water Health. 9, 617–627. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.198

Harvey, P., Bastable, A., Ferron, S., Forster, T., Hoque, E., Morries, L., et al. (2004). Excreta Disposal in Emergencies: A Field Manual. IFRC, Oxfam, G. B., UNHCR, UNICEF.

Hennegan, J., Shannon, A., Rubli, J., Schwab, K., and Melendez-Torres, G. (2019). Women's and girls' experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. 16, e1002803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803

Hennegan, J., Winkler, I., Bobel, C., Keiser, J., Hampton, J., Larsson, G., et al. (2021). Menstrual health: a definition for policy, practice, and research. Sexual Reprod. Health Matters 29, 1911618. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2021.1911618

Higgins, J., Thomas Ja, H. A. M. C., Li, T., Page, M., and Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edn. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

House, S. (2013). Situation analysis of the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) sector in relation to the fulfilment of the rights of children and women in Afghanistan, 2013. UNICEF. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/situation-analysis-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-wash-sector-relation-fulfilment (accessed March 01, 2021).

House, S., Mahon, T., and Cavill, S. (2012). Menstrual hygiene matters: a resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. WaterAid. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/menstrual-hygiene-matters (accessed March 01, 2021).

Human Rights Watch (2017). Greece: Refugees With Disabilities Overlooked, Underserved. Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/01/18/greece-refugees-disabilities-overlooked-underserved (accessed March 01, 2021).

Humanitarian Learning Centre (2017). Operational Practice Paper 1: Disability Inclusive Humanitarian Response. Brighton: Humanitarian Learning Centre. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/13404/HLC%20OPP_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed March 01, 2021).

Humanitarian Learning Centre (2018). Operational Practice Paper 3: Menstrual Hygiene Management in Humantarian Emergencies. Brighton: Humanitarian Learning Centre. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13778 (accessed March 01, 2021).

Humanitarian Response (2020). Joint Response Plan: Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis. Strategic Executive Group. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/2020-joint-response-plan-rohingya-humanitarian-crisis-january-december-2020 (accessed March 01, 2021).

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2015). Humanitarian crisis in Nepal: Gender Alert May 2015. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Available online at: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/News%20and%20events/Stories/2015/IASC%20Gender%20Reference%20Group%20%20Nepal%20Gender%20Alert%20May%2018%202015%20Finalised.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2019). Inclusion of Persons With Disabilities in Humanitarian Action: Guidelines. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Available online at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-guidelines-on-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities-in-humanitarian-action-2019 (accessed March 01, 2021).

Inter-Cluster Gender Working Group (2016). Nepal Gender Profile. OCHA/UN Women. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/nepal-gender-profile-march-2016-inter-cluster-gender-working-group (accessed March 01, 2021).

International Medical Corps (2014). Rapid Gender and Protection Assessment Report: Kobane Refugee Population. Suruc, Turkey: International Medical Corps, Care.

Jay, H., and Lee-Koo, K. (2018). Raising Their Voices: Adolescent Girls in South Sudan's Protracted Crisis. Melbourne, VIC: Monash University.

Joint Agency Research Report (2018). Rohingya Refugee Response Gender Analysis: Recognizing and Responding to Gender Inequalities. Action Against Hunger, Save the Children. Oxfam: Joint Agency Research Report.

Jones, H., and Reed, B. (2005). Water and sanitation for Disabled People and Other Vulnerable Groups - Designing services to Improve Accessibility. Loughborough University. London: WEDC.

Kuper, H., Banks, L. M., Bright, T., Davey, C., and Shakespeare, T. (2020). Disability-inclusive COVID-19 response: what it is, why it is important and what we can learn from the United Kingdom's response. Wellcome Open Res. 5, 79. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15833.1

Kuper, H., and Heydt, P. (2019). The Missing Billion: Access to Health Services for 1 Billion People With Disabilities. London: LSHTM.

Kyrkou, M. (2005). Health issues and quality of life in women with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 49, 770–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00749.x

Mactaggart, I., Banks, L. M., Kuper, H., Murthy, G. V. S., Sagar, J., Oye, J., et al. (2018). Livelihood opportunities amongst adults with and without disabilities in Cameroon and India: a case control study. PLoS ONE 13, e0194105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194105

Madigan, S. (2019). “Rapid gender and protection analysis: Cyclone Kenneth response, Cabo Delgado Province, Mozambique,” in COSACA Humanitarian Consortium.

Mason, L., Nyothach, E., Alexander, K., Odhiambo, F. O., Eleveld, A., Vulule, J., et al. (2013). ‘We keep it secret so no one should know' – a qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 8, e79132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079132

Mena, R. (2015). Meeting Gender and Menstrual Hygiene Needs in MSF-OCA Health Structures. Loughborough: Loughborough University.

Miiro, G., Rutakumwa, R., Nakiyingi-Miiro, J., Nakuya, K., Musoke, S., Namakula, J., et al. (2018). Menstrual health and school absenteeism among adolescent girls in Uganda (MENISCUS): a feasibility study. BMC Womens Health 18, 4. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0502-z

Mitchell, K. (2009). Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings: A Companion to the Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings. New York: Save the Children USA, UNFPA.

Mitra, S., Posarac, A., and Vick, B. (2013). Disability and poverty in developing countries: a multidimensional study. World Dev. 41, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.024

Ndlovu, E., and Bhala, E. (2016). Menstrual hygiene - a salient hazard in rural schools: a case of Masvingo district of Zimbabwe. JAMBA 8, 204. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v8i2.204

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2008). Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities. Available online at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx#2 (accessed March 01, 2021).

Oomen, D., Nijhof, A. D., and Wiersema, J. R. (2021). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with autism: a survey study across three countries. Mol. Autism 12, 21. doi: 10.1186/s13229-021-00424-y

Patage, D. P., Sharankumar, H., Bheemayya, B., Ayesha, N., and Kiran, S. (2015). Reproductive and sexual health needs among differently abled individuals in the rural field practice area of a medical college in Karnataka, India. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 4, 964–968. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2015.05022015198

Pearce, E. (2015). Building Capacity for Disability Inclusion in Gender-Based Violence Programming in Humanitarian Settings: A Toolkit for GBV Practitioners. New York: Women's Refugee Commission.

Phillips-Howard, P. A., Caruso, B., Torondel, B., Zulaika, G., Sahin, M., and Sommer, M. (2016). Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low- and middle-income countries: research priorities. Global Health Action 9, 33032. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.33032

Polack, S., Scherer, N., Yonso, H., Volkan, S., Pivato, I., Shaikhani, A., et al. (2021). Disability among Syrian refugees living in Sultanbeyli, Istanbul: results from a population-based survey. PLoS ONE 16, e0259249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259249

Reed, B., and Coates, S. (2012). Diversity training for engineers: making “gender” relevant. Municipal Engineer. 165, 127–135. doi: 10.1680/muen.11.00020

Robinson, A., Marella, M., and Logam, L. (2020). Gap Analysis: The Inclusion of People With Disability and Older People in Humanitarian Response (Literature Review). London, UK.

Rohwerder, B. (2014). Non-Food Items (NFIs) and the Needs of Women and Girls in Emergencies. Birmingham: GSDRC.

Rohwerder, B. (2017). Women and Girls With Disabilities in Conflict and Crises. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Sanchez, E., and Rodriguez, L. (2019). Period Poverty: Everything You Need to Know. Global Citizen. Available online at: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/period-poverty-everything-you-need-to-know/ (accessed March 01, 2021).

Scherer, N., Mactaggart, I., Huggett, C., Pheng, P., Rahman, M.-u, Biran, A., et al. (2021b). The inclusion of rights of people with disabilities and women and girls in water, sanitation, and hygiene policy documents and programs of Bangladesh and Cambodia: content analysis using EquiFrame. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 5087. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105087

Scherer, N., Mactaggart, I., Huggett, C., Pheng, P., Rahman, M.-u., and Wilbur, J. (2021a). Are the rights of people with disabilities included in international guidance on WASH during the COVID-19 pandemic? Content analysis using EquiFrame. BMJ Open 11, e046112. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046112

Schmitt, M. L., Wood, O. R., Clatworthy, D., Rashid, S. F., and Sommer, M. (2021). Innovative strategies for providing menstruation-supportive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities: learning from refugee camps in Cox's bazar, Bangladesh. Conflict Health. 15, 10. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00346-9

Shah, S. A. (2012). After the Deluge: Gender and Early Recovery Housing in Sindh, Pakistan. Geneva: UNHCR.

Shaphren, A., and Cuadra, A. (2019). Children still cry, water everywhere! A rapid assessment of child protection, gender based violence, and menstrual hygiene management needs of children, young girls and women affected by Cyclone Idai and Buzi District, Sofala Province. Plan-International. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/children-still-cry-water-everywhere-rapid-assessment-child-protection-gender-based (accessed March 01, 2021).

Sheppard, P., and Polack, S. (2018). Missing Millions: How Older People With Disabilities Are Excluded From Humanitarian Response. London, UK: HelpAge International.

Sommer, M. (2010). Where the education system and women's bodies collide: the social and health impact of girls' experiences of menstruation and schooling in Tanzania. J. Adolesc. 33, 521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.008

Sommer, M. (2012). Menstrual hygiene management in humanitarian emergencies: gaps and recommendations. Waterlines 31, 83–104. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2012.008

Sommer, M., Schmitt, M. L., and Clatworthy, D. (2017). A Toolkit for Integrating Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Into Humanitarian Response. New York: Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health and International Rescue Committee.

Sommer, M., Schmitt, M. L., Clatworthy, D., Bramucci, G., Wheeler, E., and Ratnayake, R. (2016). What is the scope for addressing menstrual hygiene management in complex humanitarian emergencies? A global review. Waterlines 35, 245–264. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.2016.024

Sommer, M., Schmitt, M. L., Ogello, T., Mathenge, P., Mark, M., Clatworthy, D., et al. (2018). Pilot testing and evaluation of a toolkit for menstrual hygiene management in emergencies in three refugee camps in Northwest Tanzania. J. Int. Humanitarian Act. 3, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s41018-018-0034-7

Sphere (2018). The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response. Sphere. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/50b491b09.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

Sthapit, C. (2015). Gendered impacts of the earthquake and responses in Nepal. Feminist Stud. 41, 682–688. doi: 10.1353/fem.2015.0028

Thapa, P., and Sivakami, M. (2017). Lost in transition: menstrual experiences of intellectually disabled school-going adolescents in Delhi, India. Waterlines 36, 317–338. doi: 10.3362/1756-3488.17-00012

Toma, I. (2019). Education-Focused Gender Analysis Case Studies: Pibor and Juba, South Sudan. Oxfam International. Available online at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/620722 (accessed March 01, 2021).

UN Committee on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities (2016). General Comment No.3, Article 6: Women and Girls With Disabilities. Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57c977344.html (accessed 1 March 2021).

UN Water (2015). Eliminating Discrimination and Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation. Available online at: http://www.unwater.org/app/uploads/2015/05/Discrimination-policy.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

UN Women (2017). Menstrual Hygiene Management in Humanitarian Situations: The Example of Cameroon. UN Women. Available online at: https://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WSSCC_MHMHumanitarien-Cameroon_EN-2017.pdf (accessed March 01, 2021).

UNHCR (2006). UNHCR Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls. Provisional Release for Consultation Purposes. UNHCR. Available online at: https://cms.emergency.unhcr.org/documents/11982/57181/UNHCR+Handbook+for+the+Protection+of+Women+and+Girls.pdf/ed5b4707-337f-4275-86e7-3af5f81186ea (accessed March 01, 2021).

UNICEF (2017). Guidance - Including Children With Disabilities in Humanitarian Action: WASH. New York, NY: UNICEF.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (2015). Overview of Natural Disasters and their Impacts in Asia and the Pacific 1970-2014. Geneva: United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly (2016). One Humanity: Shared Responsibility - Report of the Secretary-General for the World Humanitarian Summit (A/70/709). Geneva: United Nations.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2021). Menstrual Hygiene Management, Human Rights and Gender Equality. Available online at: https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/47/L.2 (accessed March 01, 2021).

van der Gaag, N. (2013). Because I am a girl: the state of the world's girls 2013. In double jeopardy: adolescent girls and disasters. Plan-International. Available online at: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/double-jeopardy-adolescent-girls-and-disasters-because-i-am-girl-state-worlds-girls-2013/ (accessed March 01, 2021).

Wilbur, J. (2020). Summary Report on Considering Disability and Ageing in COVID-19 Hygiene Promotion Programmes The HygieneHub. Available online at: https://resources.hygienehub.info/en/articles/4097594-summary-report-on-considering-disability-and-ageing-in-covid-19-hygiene-promotion-programmes (accessed March 20, 2021).